1. Introduction

The Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) system plays a central role in the immune system. It is crucial in recognizing “self” versus “non-self” antigens, enabling the stimulation and regulation of the immune response directed toward „non-self“ molecules while simultaneously maintaining tolerance to „self“ antigens. Although this function of the HLA system is necessary for the efficient defense of the organism against pathogens, it is undesirable in organ and tissue transplantation.

HLA genes are organized into three regions (class I, II, and III) located on the short arm of chromosome 6. They encode proteins whose primary role is to bind peptide antigens, present them to the immune system for recognition by T lymphocytes [

1]. HLA Class I antigens are responsible for presenting intracellular antigenic peptides to cytotoxic, CD 8+ T lymphocytes. HLA Class II antigens are present on antigen-presenting cells and are involved in presenting extracellular molecules to helper, CD 4+ T lymphocytes.

2. Immunogenetic Testing of the Recipient and Donor Before Kidney Transplantation

Organ transplantation involves the introduction of a large amount of antigens that are, to a greater or lesser extent, foreign to the recipient. In order to achieve the best possible HLA compatibility between recipient and donor and to reduce the incentive for the development of an immune graft rejection reaction, a series of immunogenetic tests are performed prior to the organ transplantation. These tests include identification of HLA alleles/antigens polymorphism (tissue typing), serum screening for the presence of HLA antibodies and determination of their specificity, as well as autologous and allogeneic crossmatch tests.

HLA typing is defined as the identification of HLA class I and II antigens and genes polymorphism through serological and molecular tests. It is performed for both, the recipient and the organ donor, to determine compatibility in the HLA system. Historically, it was done using serological testing that identified HLA antigens expressed on isolated lymphocytes. Due to its limitations, this method has mostly been abandoned, and molecular typing techniques based on PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) are now widely used.

Serum screening is a procedure that tests the presence of anti-HLA antibodies and determines their specificity if they are present in the patient. These antibodies target HLA molecules expressed on the cell surface that are highly polymorphic and can vary greatly between individuals, allowing the development of antibodies with a wide spectrum of specificities.

In the context of kidney transplantation, anti-HLA antibodies can be: pre-existing (or previously formed) antibodies and

de novo antibodies [

2]. Pre-existing antibodies are present in the recipient before transplantation as a result of previous exposure to mismatched HLA antigens through blood transfusion, pregnancy, or a previous transplant. These can increase the risk of hyperacute or acute rejection of the transplanted organ.

De novo antibodies develop after transplantation as a result of exposure to mismatched HLA antigens expressed on the transplanted organ. They contribute to chronic graft rejection.

A comprehensive definition of the anti-HLA antibody profile and its monitoring in the patient's serum allows the identification of antigens that are considered "unacceptable" for transplantation, since their presence on the donor organ can cause antibody-mediated graft rejection [

3]. Therefore, in patients on the waiting list for kidney transplantation, serum is periodically screened for the presence of anti-HLA antibodies. Currently, two screening methods are most commonly used: cell-based tests (CDC method), where results are expressed as a percentage of panel-reactive antibodies (%PRA), and solid-phase techniques (Luminex method), which have enabled the introduction of calculated PRA (CPRA) or virtual PRA (vPRA). vPRA is based on the specificities of HLA that are considered unacceptable for a sensitized transplant recipient and is calculated based on the frequency of antigens among organ donors in the studied population. Thus, vPRA represents the percentage of donors expected to have unacceptable HLA antigens to which the potential kidney recipient is sensitized [

4,

5].

3. Crossmatch Test (XM)

The presence of antibodies to mismatched HLA antigens of the organ donor triggers an immune rejection response in the recipient and is considered one of the most significant obstacles to successful transplantation. Therefore, before kidney transplantation, a final in vitro crossmatch test is performed to verify whether donor-specific antibodies (DSA) are present in the recipient’s serum that may not have been previously detected in screening and that could cause graft rejection.

The first recorded serological crossmatch test was related to blood transfusion and was performed in 1908 [

6]. In organ transplantation, the development of the crossmatch test is closely linked to research and discoveries about the HLA system. The first successful kidney transplant was performed between identical twins in 1954, four years before the discovery of the HLA system. At that time, the "crossmatch" was performed by transplanting a 2.5 x 2.5 cm skin graft between the twins. A control, autologous graft was placed 1 cm above the allogeneic one. After a little more than a month, a biopsy of the transplanted skin was performed. Macroscopic and microscopic differences between autologous and allogeneic grafts were negligible, which was considered to be evidence of tissue compatibility between twins [

7]. The discovery of the first HLA antigens marked the beginning of the era of determining tissue compatibility between organ recipients and donors. The importance of the humoral immune response in transplantation was highlighted by Terasaki and Patel in the late 1960s. They demonstrated that the presence of cytotoxic antibodies in the recipient directed against HLA antigens expressed on donor kidney cells (DSA) could lead to the development of antibody-mediated immune and hyperacute graft rejection [

8]. This discovery led to the development of the CDC crossmatch test and its mandatory use before transplantation to assess the immunological risk of transplanted organ rejection.

In addition to the described allogeneic XM, during the immunogenetic testing of a potential kidney recipient, an autologous XM must also be performed, in which the serum and HLA antigens belong to the same person. Autoantibodies are thought not to be harmful to the graft, but their presence may cause false-positive XM results before transplantation and unnecessary delay of transplantation. Therefore, it is essential to timely investigate the presence and characteristics of autoantibodies in patients and distinguish them from potential alloanti-HLA antibodies, which could have a deleterious effect on graft function and survival.

The testing protocol for allogeneic XM varies from center to center mainly depending on the patient's HLA sensitization. Several methods are used to perform XM.

4. Complement-Dependent Cytotoxicity Method (CDC)

The introduction of the crossmatch (XM) test was marked by the complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) method, developed by Terasaki and colleagues in 1964. This test uses the recipient's serum and donor lymphocytes, which are isolated from the peripheral blood of a living donor and lymph nodes and/or spleen of a deceased donor.

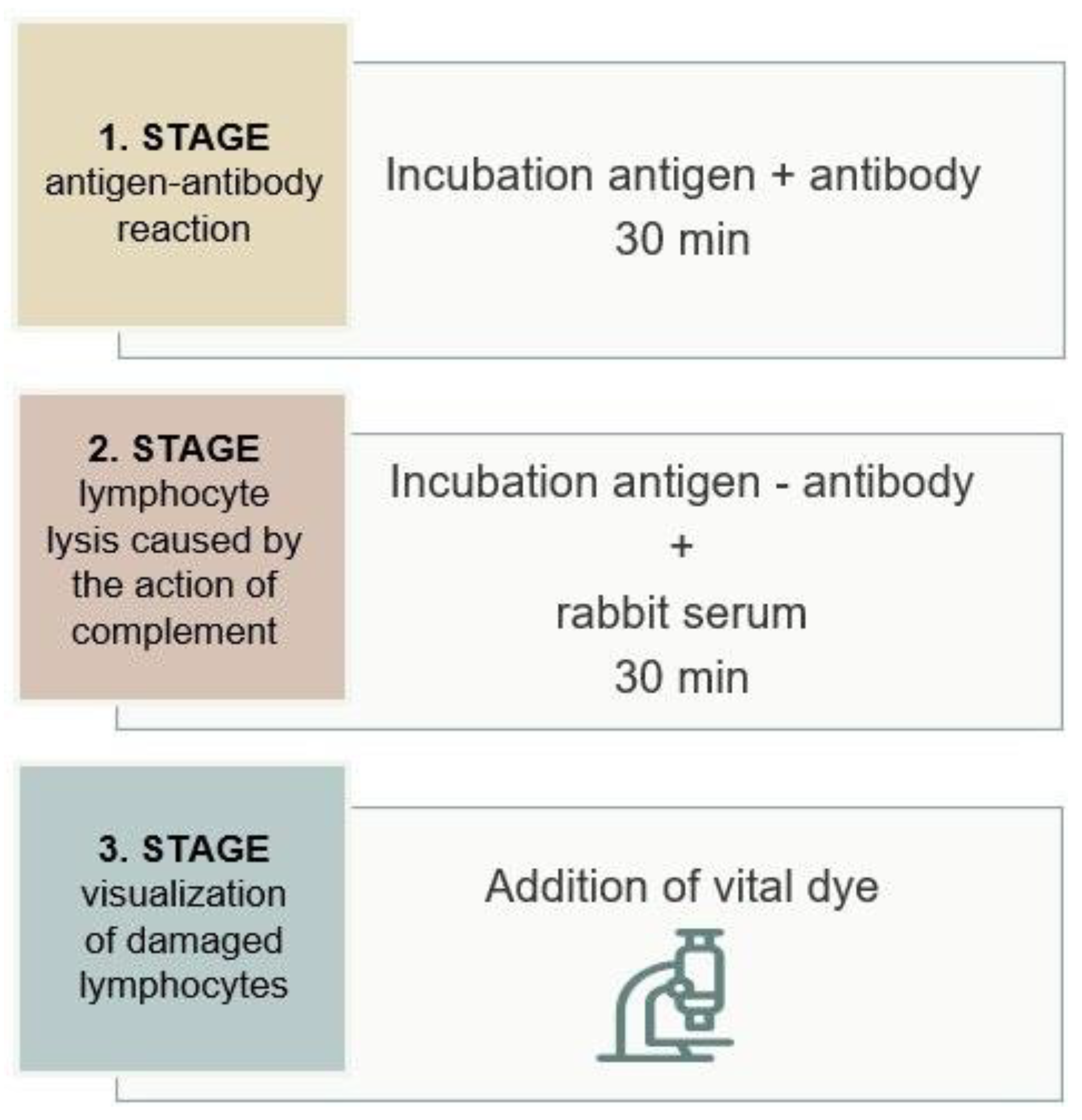

As shown in

Figure 1, the test is based on a three-step reaction. First, lymphocytes (antigens) are incubated with the recipient's serum (antibodies), forming an antigen-antibody complex if the patient's cells contain an antigen specific to the antibody. In the second phase of the reaction, rabbit serum is added as a source of complement. On cells where antigen-antibody complexes are present on the surface, complement is activated, leading to the formation of the Membrane Attack Complex (MAC) that damages the cell membrane. In the third phase of the reaction, vital dyes are added that penetrate the interior of the damaged cells, which, under an inverted microscope, indicate a positive reaction. The intensity of the reaction is scored based on the ratio of viable to dead cells, ranging from 1 (negative) to 8 (100% of damaged cells).

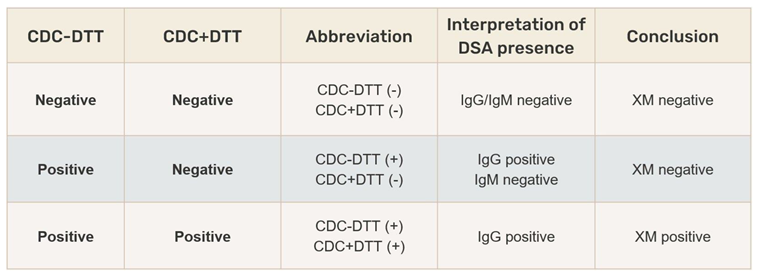

A negative XM result means that the recipient's serum does not contain donor-specific antibodies (DSA), and transplantation is not contraindicated. In the case of a positive XM, DSA are present in the recipient's serum. If IgG anti-HLA antibodies are present, they will cause an immune graft rejection reaction, while IgM anti-HLA antibodies are not considered clinically significant in kidney transplantation. To differentiate the antibody class, the XM test is performed with the addition of dithiothreitol (DTT), which breaks the disulfide bonds of IgM pentamers, creating monomers that are not able to activate complement. The DTT concentration is adjusted to affect only the disulfide bonds in the IgM molecule, leaving IgG antibodies intact. A positive crossmatch result without DTT and negative with DTT indicates the presence of IgM antibodies, which is not a contraindication for transplantation. A positive crossmatch result with and without DTT indicates the presence of IgG antibodies and requires further evaluation (

Table 1).

To improve the CDC XM test, especially due to its low sensitivity, several modifications have been introduced, such as prolonged incubation times, separation of T and B lymphocytes, different incubation temperatures, and the use of anti-human globulin (AHG) alongside the DTT treatment of serum [

9].

Advantages of the CDC XM test: high predictive value in identifying clinically significant anti-HLA antibodies that activate complement.

Disadvantages of the CDC XM test: poor reproducibility, subjective interpretation of results, dependence on the proper viability and number of lymphocytes (depending on the cell source: peripheral blood or tissue), and the inability to detect class II anti-HLA antibodies unless T and B lymphocytes are separated, which is a complex and demanding procedure.

False negative results may occur due to the low sensitivity of the test (unable to detect low-titer anti-HLA antibodies) or weak expression of HLA molecules on cell surfaces, which can be affected by medications such as statins or steroids.

False positive results can be caused by antibody reactions with non-HLA molecules expressed on cells, reactivity of autoantibodies, or immune complexes [

10].

5. Flow Cytometry Method

According to research by Patel and Terasaki, about 15% of transplanted kidneys are rejected early after transplantation despite a negative CDC XM [

8]. As a result, there was a need for more sensitive XM techniques to detect lower levels of DSA, leading to the development of the flow cytometry crossmatch (FXM) test, first performed before transplantation in 1983 [

11].

This is a cell-based test in which a suspension of donor lymphocytes (antigens) and recipient's serum (antibodies) are incubated, allowing eventually present antibodies to bind to the complementary antigen. After washing, a fluorescein-labeled anti-IgG antibody is added, which binds to the antibody in the antigen-antibody complex (DSA). The fluorescence intensity is detected and measured as the cells pass through laser beams, and the data is processed by computer software. A negative FXM result indicates the absence of donor-specific antibodies, while a positive result shows the presence of donor-specific antibodies, regardless of their complement-activating ability. Additionally, using specific monoclonal antibodies allows the differentiation of T and B lymphocyte subpopulations, which is useful for identifying antibodies against class I HLA molecules (expressed on T and B lymphocytes) or class II HLA molecules (expressed only on B lymphocytes) [

9,

12].

Advantages of the FXM test: One of the significant advantages of the flow cytometry method is its higher sensitivity compared to the CDC XM, allowing the detection of low-titer DSA, detection of immunoglobulins of clinical significance regardless of their complement-activating ability, and objective result interpretation.

Disadvantages of the FXM test: False negative or positive results. False negative results can occur due to low HLA molecule expression on donor cells, low DSA levels, high background signal in the negative serum control reaction, or an unfavorable antigen-antibody ratio due to excessive cells or small serum volume.

False positive results may be caused by insufficient washing after incubating the lymphocyte suspension with antibodies, low background signal in the negative control reaction, autoantibodies, or the use of therapeutic antibodies such as anti-thymocyte globulin, rituximab (anti-CD20), alemtuzumab (anti-CD52), basiliximab (anti-CD25), and daclizumab (anti-CD25) [

12,

13].

6. Solid-Phase Method (Luminex)

The introduction of Luminex technology in the early 2000s brought a new dimension to the detection of anti-HLA antibodies and the determination of their specificities. Solid-phase techniques enabled the detection of very low-titer anti-HLA antibodies of both class I and II, for which clinical significance has not yet been precisely defined.

The Luminex XM (LumXM) test uses color-coded microbeads coated with monoclonal antibodies specific to HLA class I and II, onto which HLA molecules from donor organ cells, obtained by cell lysis, bind during incubation. When the recipient's serum is added, eventually present DSA will bind to the donor's HLA antigens, and this reaction is detected by a secondary anti-human IgG antibody labeled with phycoerythrin (PE). Collected data are analyzed with a Luminex analyzer with xPONENT software and the MatchIt Antibody Analysis program. Previous studies on the clinical role of LumXM test have shown that recipients with positive results for anti-HLA class II antibodies do not have an increased risk factor for graft survival, while a positive LumXM result for anti-HLA class I antibodies is predictive of antibody-mediated graft rejection [

14,

15,

16]. In conclusion, LumXM represents a combination of cell-based and solid-phase assays that can only be implemented in pre-transplant risk assesment if used with other XM methods.

Advantages of the LumXM test: Higher sensitivity compared to CDC XM, clearly expressed results for specific HLA antibodies, no need for viable donor lymphocyte cells, and the lysate can be stored for extended periods for valid post-transplant monitoring [

16].

Disadvantages of the LumXM test: Compared to Luminex SAB tests, LumXM test shows lower sensitivity, especially for anti-HLA antibodies targeting HLA-A and HLA-B loci with low MFI values in SAB (Single Antigen Bead) testing. DSA specificities for anti-HLA -Cw, -DQ, and -DP are most often undetectable, as well as IgM anti-HLA antibodies. In addition to false negative results, false positives can occur, especially in recipients who had a positive autologous XM.

LumXM is more cost-effective than SAB tests, and due to the advantages and disadvantages of both tests, they are often combined.

7. Virtual Test

The virtual crossmatch (vXM) is an

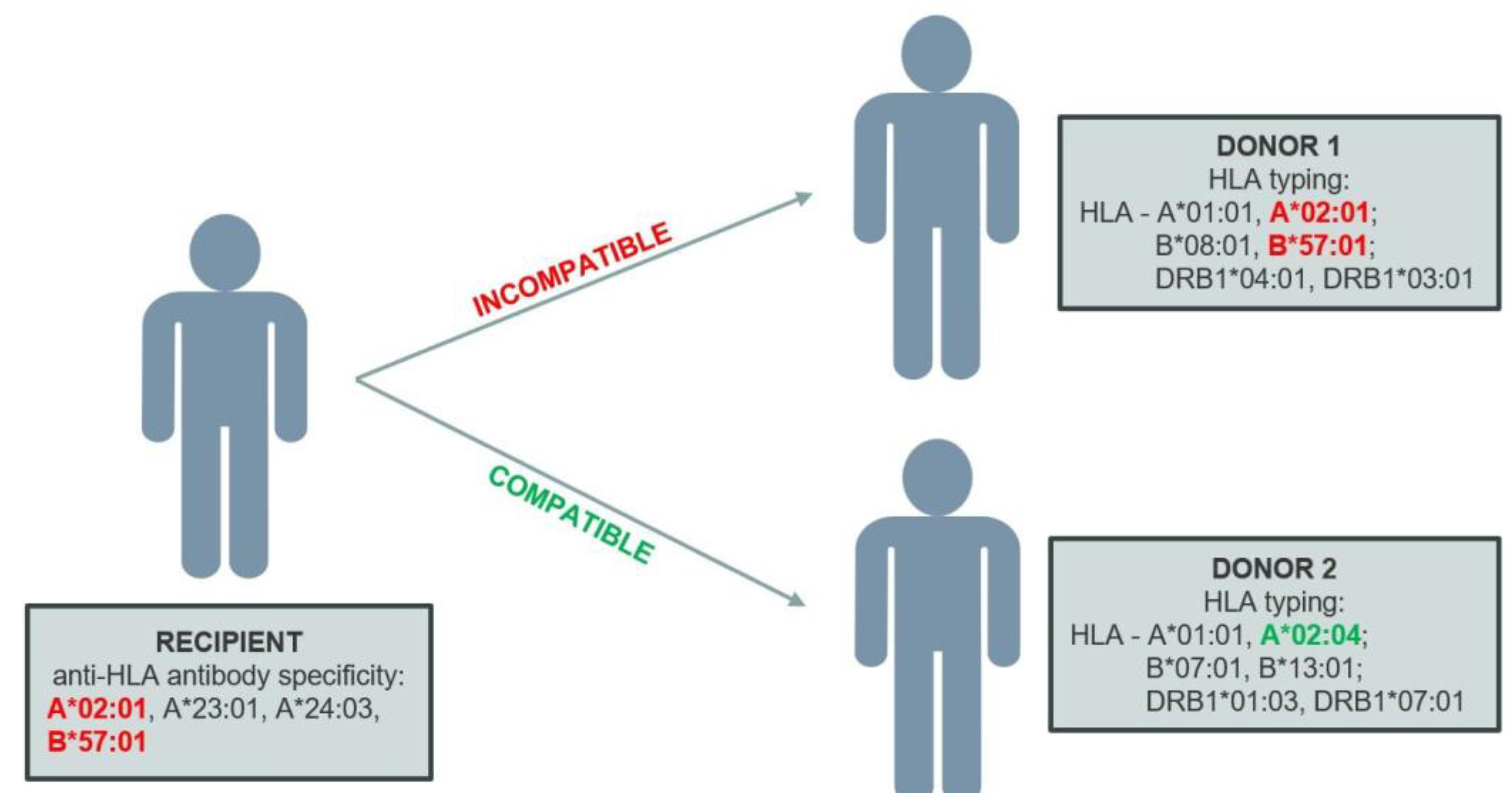

in silico test used to assess the immunological compatibility between the organ recipient and donor based on an analysis of the specificity of antibodies present in the recipient's serum and the HLA typing of the donor organ. This involves comparing the HLA alleles of the donor with unacceptable antigens for the recipient at the allele level. If the donor’s allele (antigen) is found in the recipient’s unacceptable antigen profile, the vXM will be positive (

Figure 2).

The widespread application of vXM was enabled by the development of highly sensitive solid-phase methods used for detecting and determining the specificity of anti-HLA antibodies, as well as the development of molecular HLA typing techniques that allow high-resolution identification of HLA allele polymorphisms.

SAB tests represent the most sensitive method for detecting and determining the specificity of HLA antibodies. On each set of microbeads, purified recombinant HLA glycoproteins (antigens) of only one specificity are conjugated. Since each set of polystyrene microbeads has a unique spectral signature, up to 100 different bead sets can be detected, meaning that the presence of anti-HLA antibodies can be tested for 100 different antigens in a single test. The basic principle of this method is that after incubating the microbeads with the patient’s serum, any present IgG anti-HLA antibodies specifically bind to antigens conjugated to the beads, while unbound antibodies are washed away. Bound anti-HLA antibodies are then labeled with anti-human IgG labeled with a fluorescent dye, phycoerythrin (PE), which is excited by a laser. The Luminex system uses two lasers – a green laser (532 nm) and a red laser (635 nm). The green laser excites the PE dye, emitting a unique signal that identifies bound anti-HLA antibodies. The red laser excites fluorochrome dyes within the beads, allowing the differentiation of different bead sets within a single test. The test result is expressed as the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the beads [

17].

One of the most significant advantages of vXM is the possibility of rapid assessment of immunological compatibility between the organ recipient and the donor. A negative result allows immediate transplantation without waiting for a physical crossmatch test results. This significantly reduces cold ischemia time, which is critical for the success of cadaveric transplants, increases the number of potential recipients, and decreases waiting time for transplantation. This is particularly important in heart and lung transplantation, where additional time required for performing a physical XM increases the likelihood of organ damage [

18,

19]. Studies show that patients transplanted using vXM have similar long-term outcomes compared to those transplanted using prospective physical XM. Additionally, the average number of days on the waiting list for transplantation has significantly decreased since the introduction of vXM [

20].

The results of vXM have shown high concordance with physical XM results in many studies. One significant study was conducted by Taylor and colleagues, who described their 10-year experience with selectively omitting physical XMs in cadaveric transplants in 2010 [

21]. The authors found no difference between patients who had a physical XM before transplantation and those who had a virtual XM regarding graft function, acute rejection, or graft and recipient survival. Croatia is a member of Eurotransplant, an organ exchange organization, in which vXM is currently used to decide on organ allocation, while many laboratories, including the one in Rijeka, still perform physical XM with and without DTT is performed prior to transplantation. In the Tissue Typing Laboratory Rijeka, a comparison was made between CDC and virtual XM test results performed before kidney transplants from 2018 to 2023. Discrepancy was observed in 2% of crossmatch test results, and in all CDC XM was positive and vXM was negative. Further investigations showed that CDC positivity was mainly caused by non-HLA antibodies, and in a smaller number of cases, by complement-binding IgG autoantibodies, present due to autoimmune disease [

22].

Advantages of the test: This test has the highest sensitivity and specificity compared to other methods, with no interference from antibodies against antigens outside the HLA system. It does not require viable cells but relies on complete HLA typing of the donor and the assessment of the recipient’s antibody profile. It can be completed in a few minutes (less than an hour), which allows faster decision-making regarding transplantation and increases the likelihood that organs can be transported over long distances without significantly affecting the outcome of the transplant.

Disadvantages of the test: Since vXM is based on the results of SAB tests, all the characteristics of Luminex SAB testing apply to the interpretation of vXM. Variations in the expression of HLA molecules on actual, native cells are different from the conformational structure and expression level of HLA antigens on microbeads in the SAB test. Therefore, the limitations of vXM are thoroughly outlined to ensure the correct interpretation of results in clinical applications.

False negative results can be caused by:

"Peanut butter" effect: This refers to the ability to detect a small amount of antibody targeted to an antigen on one bead, but when spread across many beads, the signal can fall below the set threshold, analogous to spreading peanut butter on one slice of bread versus distributing it across all slices of a loaf. Recent studies have not confirmed this effect [

23].

Prozone effect: This occurs when serum components interfere with the detection of anti-HLA antibodies, such as high levels of antibodies that may activate complement, leading to C1 deposition on the beads, the presence of IgM antibodies, immune complexes, intravenous immunoglobulin, thymoglobulin, or other factors that can interfere with secondary antibody binding. Complement-mediated interference in SAB tests can be reduced by treating sera with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), heat, or DTT before testing [

24].

Antibodies to rare alleles that are not represented on the microbeads of the SAB test.

Undetected HLA antibodies due to concentrations below the test’s sensitivity threshold, which is determined by the minimum MFI value. In such cases, the clinical significance of the antibody specificity must be considered based on the sensitizing event and previous test results.

Unreported sensitizing events after the last serum screening.

Complement-activating antibodies, which are associated with a higher incidence of acute graft rejection reactions, cannot be distinguished from non-complement-activating antibodies using SAB tests or vXM. For this purpose, adding C1q or C3d components to the SAB test is recommended.

False positive results may be caused by:

Detecting antibodies that are clinically insignificant. Since MFI value is no standardized, the detection of antibodies that are not clinically significant may occur due to test hypersensitivity, leading to misinterpretation. As a result, transplantation may be unnecessarily delayed due to a false positive result, or inappropriate immunosuppressive therapy may be applied after the procedure.

The presence of potentially interfering autoantibodies resulting from autoimmune disease [

25]. One of the procedures performed in this case is the autologous XM test, which can distinguish between auto- and allo-antibodies.

The production process during reagent preparation and the binding of HLA molecules to microbeads, which may lead to conformational changes, denaturation, and the exposure of a new epitope (which does not exist on the native molecule) or cryptic antigens (which are otherwise unavailable to antibodies) with which antibodies will react [

26].

The presence of therapeutic antibodies such as rituximab and anti-thymocyte globulin [

27].

"Natural" HLA antibodies, i.e., HLA antibodies detected in individuals without any known sensitization events, which are currently considered nonspecific. It is believed that they may arise due to cross-reactivity following bacterial or viral infections, such as influenza and hepatitis C, or after vaccination. Environmental factors such as microorganisms, food proteins, and allergens are considered as possible causes. Pro-inflammatory events, such as surgical procedures or trauma, are also associated with an increase in titers and the broadening of the specificity of anti-HLA antibodies [

28,

29,

30,

31].

Non-HLA antibodies. Non-HLA antigens are molecules outside the HLA system expressed on lymphocytes. They arise as a products of nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that result in a change in the codon, inserting a different amino acid into the polypeptide, creating polymorphic peptides recognized as „non-self“ by the immune system. Non-HLA molecule mismatches between the donor and recipient will trigger an immune response and the formation of specific antibodies. Research is underway to investigate the association between the development of graft rejection in kidney and other organ transplants and antibodies targeting non-HLA antigens, such as antibodies against vimentin, endothelin receptors, angiotensin II receptors, and other antigens [

32].

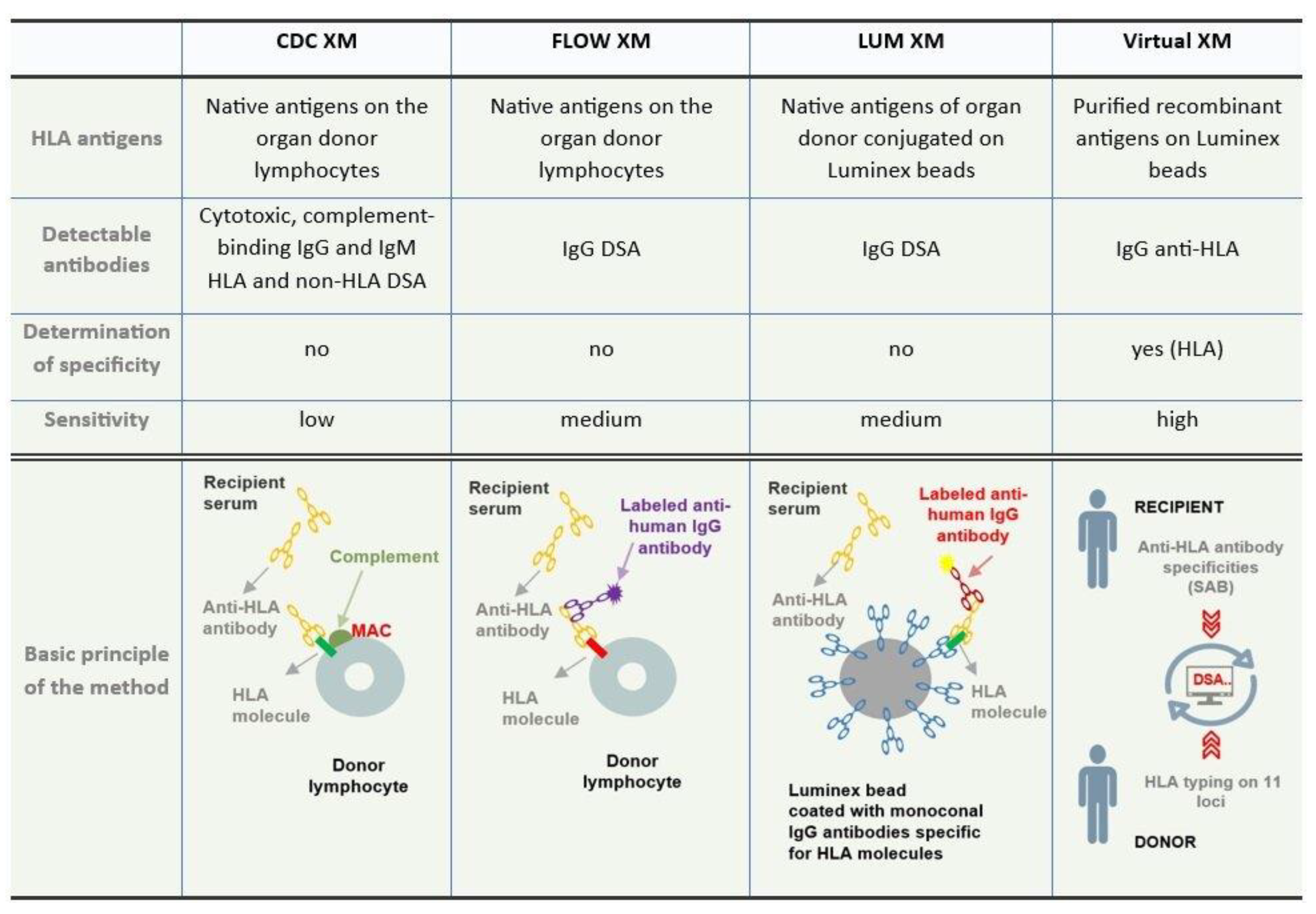

A comparison of the basic characteristics of crossmatch test methods is shown in

Figure 3.

8. Clinical Application of Virtual Crossmatch Testing in Kidney Transplantation

Crossmatch test is part of the immunogenetic assessment of patients to determine immune compatibility between the organ recipient and donor in order to estimate immunological risk for the organ recipient. Before transplantation, this procedure determines the presence of DSA in the patient's serum, which can adversely affect graft function and survival as well as the patient's clinical condition.

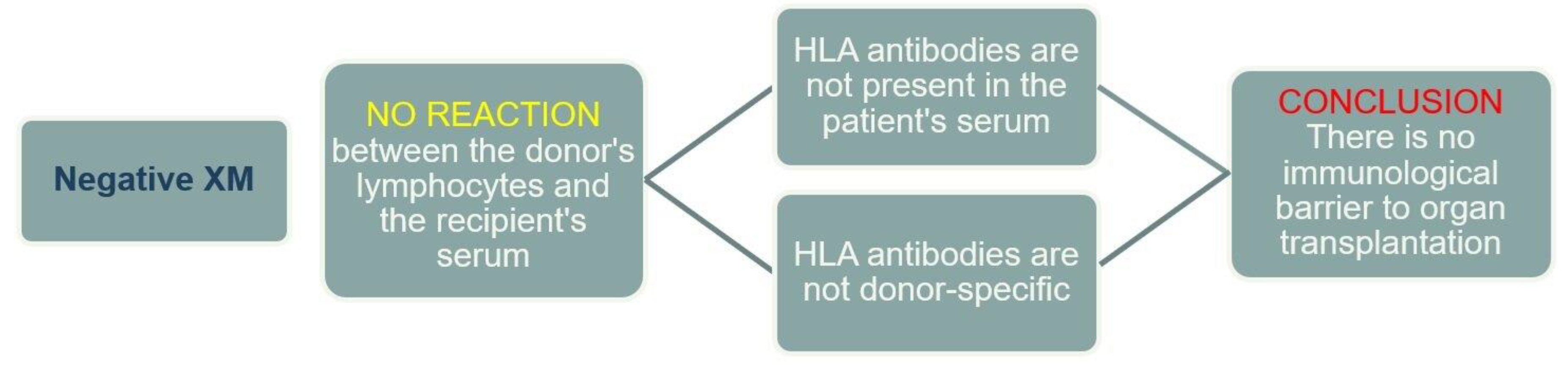

A negative XM result indicates that there are no anti-HLA antibodies in the recipient's serum, or if present, they are not DSA (

Figure 4).

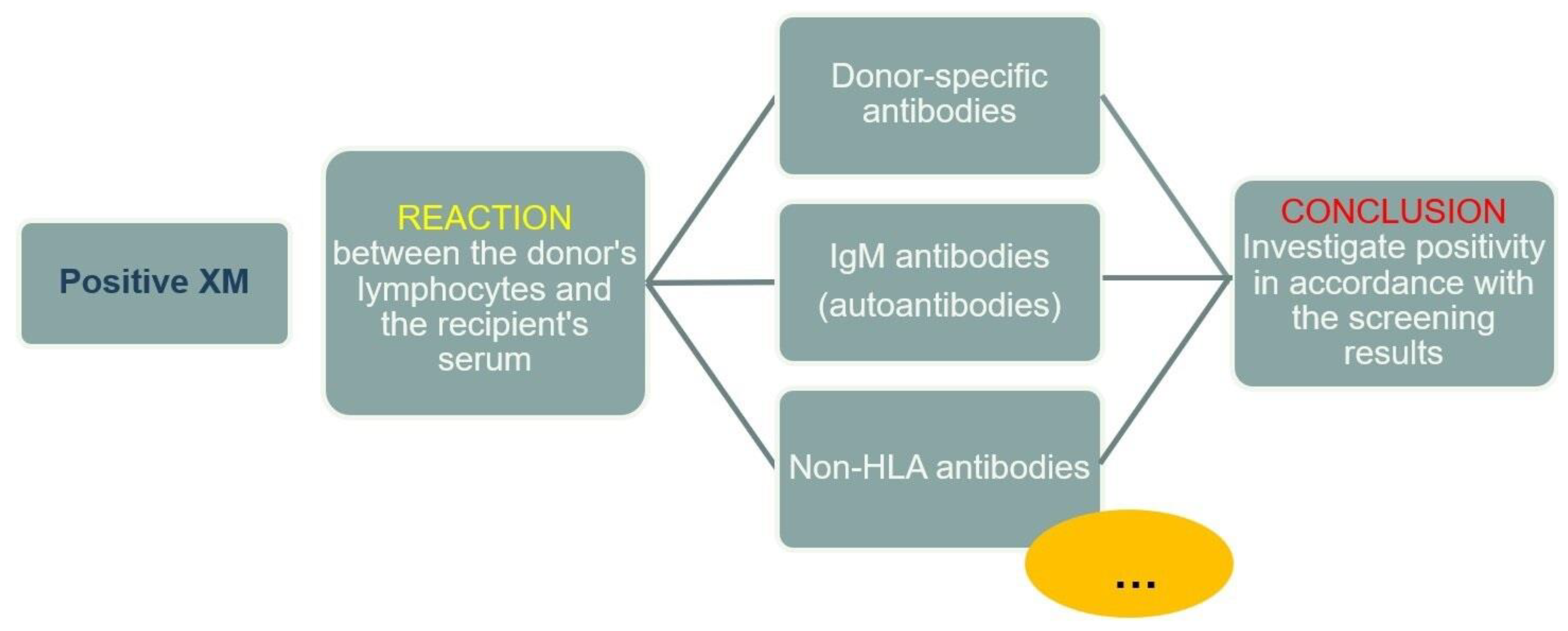

A positive XM result indicates a reaction between the donor's HLA molecules and the recipient's serum (antibodies). In the case of a positive reaction, the cause must always be investigated, keeping in mind that, in addition to HLA molecules, various other antigens may be expressed on the surface of lymphocytes to which antibodies in the recipient's serum can bind, regardless of their specificity (

Figure 5).

As early as 1969, Patel and Terasaki demonstrated that in kidney transplantation, after a positive CDC XM, 80% of grafts were rejected compared to 4% of grafts transplanted with a negative CDC XM [

8]. Due to its high predictive value, the CDC-based XM method was considered the gold standard in kidney transplantation for decades. Initially, every positive result (whether from a "fresh" or "historical" serum sample) was considered a contraindication for transplantation. However, research aided by the development of immunosuppressive drugs demonstrated that a positive XM with "historical" serum samples did not significantly affect transplantation outcomes if the XM with a "fresh" serum sample was negative. To overcome the limitations of the CDC XM test (despite modifications), more sensitive tests such as XM methods based on flow cytometry and solid-phase assays were developed [

11].

Today, molecular methods allow HLA allele sequencing, and solid-phase assays enable the detection of low-titer antibodies and precise determination of specificity, driving the advancement of XM methods to the level of virtual testing. In virtual XM, the specificity of anti-HLA antibodies detected in the recipient is compared to the HLA antigen profile of the potential organ donor.

One of the greatest challenges of vXM is determining clinically significant donor-specific antibodies. The test is based on the results of SAB tests expressed as MFI values. The threshold value is not standardized, it differs from laboratory to laboratory, and due to the characteristics of Luminex technology, there is a fine line between sensitivity and hypersensitivity. Depending on the test manufacturer, antibodies with an MFI lower than 1000 – 2000 are generally considered low immunological risk and clinically insignificant. Antibodies with higher MFI values must be taken into account when interpreting the results, keeping in mind several specificities of the test. First, the fact that MFI is a semi-quantitative value should be considered. The assumption that antibodies with higher MFI values are more clinical significant compared to antibodies with lower MFI is not always correct for several reasons. Not all HLA antigens are equally immunogenic. For instance, HLA-A2, -B35, and -B44 antigens are highly immunogenic, so there is a high likelihood of graft rejection if DSA of these specificities are present, even at lower MFI values. Additionally, antigens from the HLA-C, -DQ, and -DP loci are more represented on the beads in SAB tests than on native cells. Therefore, the threshold MFI value indicating clinically significant antibodies for these loci should be higher than for others. Furthermore, in patients with previous transplants, some centers exclude their donor's mismatched antigens, regardless of their presence in the SAB test, due to a memory immune response.

Understanding the limitations of each test is crucial for accurately interpreting laboratory results. The above XM methods have their own advantages and disadvantages, which must be considered when selecting the most appropriate one for the center's needs. Factors such as technical characteristics, performance difficulty and result interpretation, financial aspects, and the possibility of clinical and pharmacotherapeutic management of the transplant recipient must also be considered. Additionally, one method does not exclude another, and applicability can be defined based on specific patient groups (e.g., non-sensitized, sensitized, and/or highly sensitized patients). The CDC and flow cytometry methods use viable, native cells, and reactions in these tests are the closest to those that actually occur in the body. Furthermore, the experience in interpreting and understanding the test results in clinical application makes these methods, particularly CDC, still the method of choice in many transplant centers. On the other hand, solid-phase tests use recombinant molecules, and reactions will not fully reflect biological mechanisms. However, compared to cellular tests, they have high sensitivity and specificity, enabling the detection of DSA in a low titer, and have become the basis of vXM, which enters into all wider applications. For comparison with other methods, vXM detects anti-HLA antibodies that have an MFI ≤ 1000 – 2000 in the SAB test (depending on the test manufacturer). The flow cytometry-based XM test is positive when MFI ≥ 2500, and the CDC XM is positive for MFI values higher than 8000 –10000 [

33]. These data are useful for correlating results from different methods and interpreting them in a clinical context.

Above all, it is important to highlight that the results of anti-HLA antibody serum screening and XM tests are interdependent, meaning that with an accurate determination of the specificity of anti-HLA antibodies in the patient's serum, it is possible to predict the result of the XM with high certainty. In addition to XM results, analyzing the results of screening is equally important to gain a better understanding of the patient's immune status and assess the risks associated with the potential donor.

A challenge and a special approach are required by sensitized, especially highly sensitized (vPRA ≥ 85% in Eurotransplant) patients whose serum has proven HLA SAB antibodies [

34]. In these groups of patients, it is necessary to have a good knowledge of the specificity and characteristis of the antibodies that will be included in the analysis when performing vXM, keeping in mind the limitations of the SAB test. It is useful to correlate the test results with sensitizing events that may explain the specificity of positive reactions. If information about the sensitizing event is incomplete, there is a possibility of false positive results. In these cases, the physical XM test may be valuable in determining clinically significant DSA.

Transplant medicine, particularly immunogenetics, is one of the fastest-growing fields in medicine and science. New technologies and methods of molecular typing, the discovery of the 3D structure of HLA molecules, and the development of sensitive techniques to test for the presence of anti-HLA antibodies have led to a better understanding of the complex patterns of humoral immunity. The terms epitope, eplet, and triplet have been known for years, and progress in this area has enabled the development of algorithms for tissue matching at the epitope level (HLA epitope matching) using computer programs such as HLAMatchmaker and Predicted Indirectly ReCognizable HLA Epitopes (PIRCHE) [

35]. One of the necessary prerequisites for the wider clinical application of these algorithms is the adoption of a unified stand on the definition of clinically significant epitopes and matching strategy. It is known that the properties of epitopes are influenced not only by their conformational structure but also by the electrostatic charge, the types and properties of the amino acids surrounding the eplet, etc. Reactivity to a specific eplet does not necessarily mean that all alleles carrying that eplet are considered unacceptable. It is also important to differentiate between the immunogenicity and antigenicity of epitopes at this level. Immunogenicity refers to the ability to induce a humoral and/or cell-mediated immune response, while antigenicity refers to the ability of a molecule to specifically bind to antibodies and/or surface receptors on T lymphocytes [

36]. Immunogenic molecules have antigenic properties, but not necessarily the reverse. Assessing the immunogenicity of individual epitopes is crucial in preventing graft rejection [

37].

It is also necessary to emphasize the growing potential of using artificial intelligence (AI) in all areas of everyday life as well as in medicine. AI is currently in the research phase, but there is a prospect for its implementation, with vXM becoming the basis for using AI to determine immunological risk for the recipient before transplantation. In any case, it is expected that the future will open new avenues for further research and discoveries in the field of transplant immunogenetics.

Finally, one of the key elements, regardless of the advancement of science and technology, that forms the foundation of a successful transplantation outcome is good, open, and continuous communication between HLA laboratory staff and transplant clinicians. Every transplant center should assess the risk for each patient individually based on the results of all methods and tests used (screening, XM), sensitizing events, and clinical data relevant to assessing the patient's immune status. Only a personalized approach can ensure appropriate patient care and secure a long-term successful outcome.

Author Contributions

N.K. and T.C.M.: Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the acquisition of data for the work, writing—original draft preparation; Z.T.: writing—review it critically for important intellectual content and editing; F.B.T.: acquisition of data for the work; S.B.: final approval of the version to be published. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Mosaad, Y.M. Clinical Role of Human Leukocyte Antigen in Health and Disease. Scand. J. Immunol. 2015, 82(4), 283-306. [CrossRef]

- Alelign, T.; Ahmed, M.M.; Bobosha, K.; Tadesse, Y.; Howe, R.; Petros, B. Kidney Transplantation: The Challenge of Human Leukocyte Antigen and Its Therapeutic Strategies. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2018, 5986740. [CrossRef]

- Süsal, C.; Roelen, D.L.; Fischer, G.; Campos, E.F.; Gerbase-DeLima, M.; Hönger, G.; Schaub, S.; Lachmann, N.; Martorell, J.; Claas, F. Algorithms for the determination of unacceptable HLA antigen mismatches in kidney transplant recipients. Tissue Antigens. 2013, 82(2), 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Huber, L.; Lachmann, N.; Niemann, M.; Naik, M.; Liefeldt, L.; Glander, P.; Schmidt, D.; Halleck, F.; Waiser, J.; Brakemeier, S.; Neumayer, H.H.; Schönemann, C.; Budde, K. Pretransplant virtual PRA and long-term outcomes of kidney transplant recipients. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28(6), 710-719. [CrossRef]

- Süsal, C.; Morath, C. Virtual PRA replaces traditional PRA: small change but significantly more justice for sensitized patients. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28(6), 708-709. [CrossRef]

- Oberman, H.A. The crossmatch. A brief historical perspective. Transfusion. 1981, 21(6), 645-651. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, H. The first identical twin renal transplant. J. Perioper. Pract. 2015, 25(3), 58-59. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Terasaki, P.I. Significance of the positive crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1969, 280(14), 735-739. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, A.; Ramon, D.S.; Stoll, S.T. Technical aspects of crossmatching in transplantation. Clin. Lab. Med. 2018, 38, 579–593. [CrossRef]

- Badders, J.L.; Jones, J.A.; Jeresano, M.E,; Schillinger, K.P.; Jackson, A.M. Variable HLA expression on deceased donor lymphocytes: Not all crossmatches are created equal. Hum. Immunol. 2015, 76(11), 795-800. [CrossRef]

- Garovoy, M.R.; Rheinschmilt, M.A.; Bigos, M.; Perkins, H.; Colombe, B.; Feduska, N.; Salvatierra, O. Flow cytometry analysis: A high technology crossmatch technique facilitation transplantation. Transplant. Proc 1983, 15, 1939.

- Maguire, O.; Tario, J.D.Jr.; Shanahan, T.C.; Wallace, P.K.; Minderman, H. Flow cytometry and solid organ transplantation: a perfect match. Immunol. Invest. 2014, 43(8), 756-774. [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, N. Improved flow cytometry crossmatching in kidney transplantation. HLA. 2018, 92(6), 375-383. [CrossRef]

- Billen, E.V.; Voorter, C.E.; Christiaans, M.H.; van den Berg-Loonen, E.M. Luminex donor-specific crossmatches. Tissue Antigens. 2008, 71(6), 507-513. [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, N.; Mazouz, H.; Piot, V.; Presne, C.; Westeel, P.F. Correlation between Luminex donor-specific crossmatches and levels of donor-specific antibodies in pretransplantation screening. Tissue Antigens. 2013, 82(1),16-20. [CrossRef]

- Ameur, R.F.; Berkani, L.M.; Belaid, B.; Habchi, K.; Saidani, M.; Djidjik, R. Luminex Crossmatch in kidney transplantation. Scand. J. Immunol. 2023, 98(1), e13279. [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, N.; Todorova, K; Schulze, H; Schönemann, C. Luminex(®) and its applications for solid organ transplantation, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and transfusion. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2013, 40(3), 182-189. [CrossRef]

- Bohmig, G.A.; Fidler, S.; Christiansen, F.T.; Fischer, G.; Ferrari, P. Transnational validation of the Australian algorithm for virtual crossmatch allocation in kidney paired donation. Hum. Immunol. 2013, 74(5), 500–505. [CrossRef]

- Zangwill, S.; Ellis, T.; Stendahl, G.; Zahn, A.; Berger, S.; Tweddell, J. Practical application of the virtual crossmatch. Pediatr. Transplant. 2007, 11(6), 650-654. [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, R.; Czer, L.S.; Reinsmoen, N.L.; Cao, K.; Rafiei, M.; De Robertis, M.A.; Mirocha, J.; Kass, R.M.; Kobashigawa, J.A.; Trento, A. Impact of virtual cross match on waiting times for heart transplantation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 92(6), 2104-2110, discussion 2111. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.J.; Kosmoliaptsis, V.; Sharples, L.D.; Prezzi, D.; Morgan, C.H.; Key, T.; Chaudhry, A.N.; Amin, I.; Clatworthy, M.R.; Butler, A.J.; Watson, C.J.; Bradley, J.A. Ten-year experience of selective omission of the pretransplant crossmatch test in deceased donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2010, 89(2), 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Barin-Turica, F. Virtual crossmatch test in kidney transplantation. Final thesis, Faculty of Medicine, University of Rijeka, Croatia, 2024.

- Claisse, G.; Devriese, M.; Lion, J.; Maillard, N.; Caillat-Zucman, S.; Mooney, N.; Taupin, J.L. Relevance of Anti-HLA Antibody Strength Underestimation in Single Antigen Bead Assay for Shared Eplets. Transplantation. 2022, 106(12), 2456-2461. [CrossRef]

- Schnaidt, M.; Weinstock, C.; Jurisic, M.; Schmid-Horch, B.; Ender, A.; Wernet, D. HLA antibody specification using single-antigen beads--a technical solution for the prozone effect. Transplantation. 2011, 92(5), 510-515. [CrossRef]

- Schlaf, G.; Pollok-Kopp, B.; Schabel, E.; Altermann, W. Artificially Positive Crossmatches Not Leading to the Refusal of Kidney Donations due to the Usage of Adequate Diagnostic Tools. Case. Rep. Transplant. 2013, 2013, 746395. [CrossRef]

- Amico, P.; Hönger, G.; Mayr, M.; Schaub, S. Detection of HLA-antibodies prior to renal transplantation: prospects and limitations of new assays. Swiss. Med. Wkly. 2008, 138(33-34), 472-476. [CrossRef]

- Milongo, D.; Vieu, G.; Blavy, S.; Del Bello, A.; Sallusto, F.; Rostaing, L.; Kamar, N.; Congy-Jolivet, N. Interference of therapeutic antibodies used in desensitization protocols on lymphocytotoxicity crossmatch results. Transpl. Immunol. 2015, 32(3), 151-155. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Buenrostro, L.E.; Terasaki, P.I.; Marino-Vázquez, L.A.; Lee, J.H.; El-Awar, N.; Alberú, J. "Natural" human leukocyte antigen antibodies found in nonalloimmunized healthy males. Transplantation. 2008, 86(8), 1111-1115. [CrossRef]

- Hirata, A.A.; McIntire, F.C.; Terasaki, P.I.; Mittal, K.K. Cross reactions between human transplantation antigens and bacterial lipopolysaccharides. Transplantation. 1973, 15(5), 441-445.

- Katerinis, I.; Hadaya, K.; Duquesnoy, R.; Ferrari-Lacraz, S.; Meier, S.; van Delden, C.; Martin, P.Y.; Siegrist, C.A.; Villard, J. De novo anti-HLA antibody after pandemic H1N1 and seasonal influenza immunization in kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant. 2011, 11(8), 1727-1733. [CrossRef]

- El Aggan, H.A.; Sidkey, F.; El Gezery, D.A.; Ghoneim, E. Circulating anti-HLA antibodies in patients with chronic hepatitis C: relation to disease activity. Egypt. J. Immunol. 2004, 11(2), 71-79.

- Zhang, Q.; Reed, E.F. The importance of non-HLA antibodies in transplantation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2016, 12(8), 484-495. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Y.; Jaramillo, A.; Neumann, J.; Hacke, K.; Palou, E.; Torres, J. Crossmatch assays in transplantation: Physical or virtual?: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023,102(50):e36527. [CrossRef]

- Heidt, S.; Haasnoot, G.W.; van der Linden-van Oevelen, M.J.H.; Claas, F.H.J. Highly Sensitized Patients Are Well Served by Receiving a Compatible Organ Offer Based on Acceptable Mismatches. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 687254. [CrossRef]

- Tambur, A.R. HLA-Epitope Matching or Eplet Risk Stratification: The Devil Is in the Details. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tao, A. Antigenicity, Immunogenicity, Allergenicity. Allergy Bioinformatics. 2015, 8, 175-186. [CrossRef]

- Bezstarosti, S.; Kramer, C.S.M.; Claas, F.H.J.; de Fijter, J.W.; Reinders, M.E.J.; Heidt, S. Implementation of molecular matching in transplantation requires further characterization of both immunogenicity and antigenicity of individual HLA epitopes. Hum. Immunol. 2022, 83(3), 256-263. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).