1. Introduction

Chaos has been extensively studied by a large scientific community as an interesting complex dynamic phenomenon. Firstly, chaos was analyzed as a phenomenon that can occur naturally by variations of system parameters [

1,

2]. For example, a Buck converter can exhibit a chaotic behavior with the variation of the current reference [

3,

4], the inductance [

5] of the converter, the load [

6], the voltage reference [

7] or a control parameter [

8,

9].

Recently, chaos has evolved to a new phase of control (i.e. suppressing of chaos), utilizing chaos or the generation of chaos from an originally non-chaotic system. The goal of purposefully causing chaos (a shift from order to chaos), also known as chaotification or anticontrol of chaos, has garnered a lot of interest lately because of its enormous potential in unconventional applications with opportunities to employ entirely novel and different strategies.

Numerous chaotic and nonlinear events have been seen in optical or physical systems. Reference [

10] examines how the parallelly and orthogonally polarized intensity-modulated optical injection on vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers is affected by the chaotic dynamic behaviors of injection strength, frequency detuning and modulation parameters (modulation depth and modulation frequency). A traditional electro-optic intensity chaotic model is used to propose an electro-optic linked mutual injection chaotic system in [

11].

From the conventional tendency of comprehending and analyzing chaos to using it, the study of chaotic dynamics has changed, such as on financial time series. The authors of [

12] analyze the chaotic characteristics and predictive modeling of the daily price time series of West Texas Intermediate crude oil from 2009 to 2019. Utilizing chaos theory and artificial intelligence techniques, they analyze the time series and assess the impact of noise on price forecasting accuracy.

The anticontrol of chaos has attracted growing interest for applications in secure transmission as image encryption. An image encryption method based on the anti-control method is designed in [

13], and the encryption algorithm with chaotic position scrambling and stream cipher encryption for multi-rounds is established. As demonstrated in [

1], chaos synchronization does not necessarily require broadband couplings, as the damped resonance can be entrained even with frequency-limited coupling. This insight allows to future applications of chaos-based communication using practical antennas, particularly in areas like distributed sensing. Later, in 2023, Erkan, Ogras and Fidan [

14] propose a secure data transmission application using a modulation-based transceiver circuit: an encryption key was generated using a chaotic logistic map and embedded into both the transmitter and receiver circuits. These circuits were configured with identical system parameters to ensure synchronization and secure communication. Then, an encryption-and-compression-based technique for medical images is proposed by [

15]. After a comprehensive cryptanalysis, [

16] identifies that a chaotic image encryption scheme based on a variant of the Hill cipher is vulnerable to both chosen-plaintext and chosen-ciphertext attacks due to inherent structural weaknesses in its design.

The route to chaos is very impressive in biological and medical systems. The authors of [

17] explore a computational dynamic solution as a possible therapy for epileptic seizures control. A neuronal model of epileptiform activity is chaotified and executed before the seizure starts. More recently, bifurcation theory has been employed to analyze the progression of diseases by investigating new fractional-order models of six chaotic diseases [

18]. In order to suppress chaos, back-stepping, adaptive feedback and sliding mode control strategies are used in fractional-order models of Diabetes Mellitus, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Ebola Virus and Dengue models. The anticontrol of chaos with linear state feedback, single state sine feedback and sliding mode anticontrol is designed in fractional-order models of Parkinson’s illness and migraine. To investigate the neuromorphic dynamics of memristive neurons, [

19] proposes a tri-stable locally active memristor model via Chua’s unfolding principle. This study shows that memristive circuits can generate diverse neuromorphic patterns within the right-half plane domain, particularly near the edge of chaos, highlighting their potential for modeling complex neuronal behavior. In contrast, [

20] develops a theoretical model of gene expression dynamics that reveals chaotic behavior emerging from rapid molecular feedback loops coupled with cell growth dynamics and intercellular interactions. This chaotic behavior is proposed as an explanation for the heterogeneous responses of Escherichia coli cells to oxidative stress. Both studies emphasize the critical role of chaos in understanding complex systems, from artificial neurons to biological gene regulation.

In the field of electrical systems, [

21] proposes an anti-oscillation (control of chaos) scheme for a fractional-order brushless DC motor system. This approach aims to eliminate chaotic oscillations in systems with unknown dynamics and immeasurable states, ensuring stable operation by effectively suppressing chaotic behavior. Similarly, [

22] introduces the modified chaos grasshopper algorithm, an advanced optimization approach. This algorithm is applied to improve the performance of techno-economic energy management strategies in microgrids incorporating fuel cells, batteries, and photovoltaic systems. A chaos learning butterfly optimization technique with enhanced extraction of the photovoltaic model parameter is presented in [

23]. Following a numerical evaluation of the second-law characteristics of a solar water heater with a dual-twisted tape turbulator, [

24] uses nonlinear calibration with chaos control to establish a thermal energy prediction model for varying Reynolds number and twist pitch values.

Switch-mode power supplies produce electromagnetic interference (EMI) at their switching frequency and harmonic frequencies. This interference significantly complicates achieving electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), especially when employing pulse-width modulation (PWM) techniques. The modulation of the switching frequency, as presented by [

25] and [

26], is a technique aimed at reducing spectral emissions. In 1999, Deane further proposed the innovative idea of using chaos to improve electromagnetic compatibility by diminishing spectral peaks [

27]. However, the application of the classical chaos anticontrol method to switch-mode power supplies increases the overall magnitude of output voltage ripple, a result corroborated later by [

28]. In contrast, [

29] and [

30] introduced a chaotified nonlinear feedback approach capable of achieving low spectral emissions while maintaining minimal output voltage ripple by employing chaotic attractors of small dimensions. More recently, [

31] proposed a chaos-based pulse-width modulation technique that leverages the logistic map to distribute the harmonics of a Boost converter, effectively reducing electromagnetic interference. Building on these advancements, [

32] introduced a novel radio frequency transmitter that utilizes a chaotic sequence generator to minimize output signal hysteresis and applies a modulation process to reduce spectral emissions. Additionally, [

33] studied a high-frequency isolated quasi Z-source photovoltaic grid-connected micro-inverter employing chaotic frequency modulation technology to suppress inverter spectral emissions effectively.

The anticontrol of chaos feedback necessitates rapid switching actions in converters, which impose thermal stress on power-switching semiconductor devices [

34]. Consequently, it becomes critical to analyze their thermal performance to ensure operational safety and prevent failures of power devices [

35]. To evaluate the efficiency and reliability of power electronic systems, semiconductor devices are often modeled as ideal switches in fast simulations, as seen in [

36]. However, this approach makes it challenging to accurately calculate MOSFET power losses. Establishing an electro-thermal model [

37] is essential to account for the impact of junction temperature on the device parameters.

Numerous electro-thermal models have been presented in scientific literature. For approximating IGBT switching and on-state losses, [

38] employed the lookup table method. Using inputs such as junction temperature and electrical load, a complete and comprehensive electro-thermal model is proposed by [

39]. Similarly, the model by [

40] incorporates the interactions between junction temperature and the transistor’s voltages and currents. In [

41], power losses are averaged across each switching cycle using a high-speed electro-thermal model. Furthermore, [

42] and [

43] developed a realistic converter model, with parameters derived from component datasheets, PCB layout, as well as cable length and diameter.

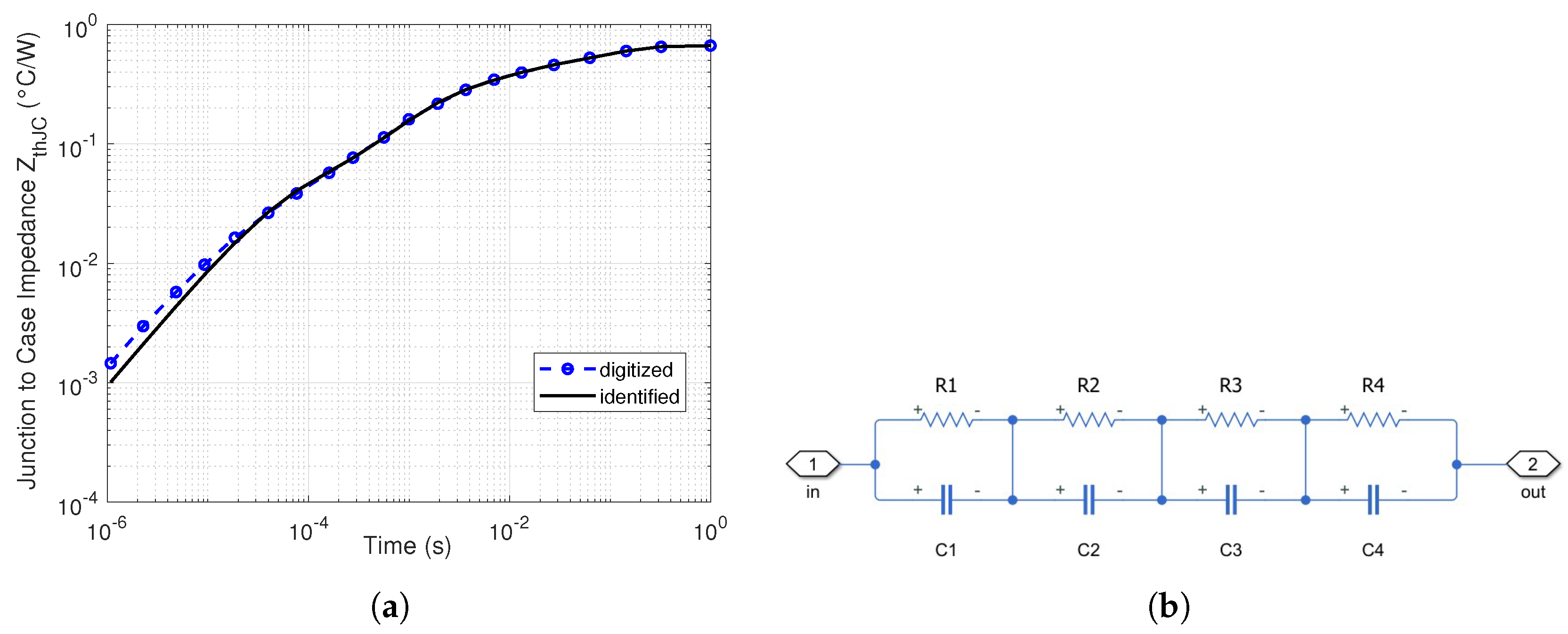

To analyze the Mosfet thermal behavior, the most prevalent heat transfer model uses several

Foster [

44,

45] networks. In [

46], Nayak and Pramanick utilized a third-order Foster circuit to accurately fit the MOSFET impedance curve provided in the datasheet. Additionally, [

47] proposed various electro-thermal Foster circuit variants to simulate the performance of an electric vehicle inverter.

Changes in the power device junction temperature affect their reliability and lifetime, according to [

48]. The Coffin-Manson law is one of the most widely used models for evaluating failure cycles and estimating the lifetime of switching devices. Inverter lifetime [

49] is commonly assessed using the rainflow counting algorithm, which takes as inputs the mean junction temperature and the variation on junction temperature [

50,

51], and [

52]. In [

53], an analysis is presented on the influence of chaos on junction temperature, revealing that a chaotic current behavior reduces the MOSFET’s lifetime by half, compared to periodic current behavior.

After a chaotification of a Buck converter (in order to reduce spectral emission), the purpose of this article is to analyse the influence of an anticontrol of chaos controller on the junction temperature and to compare it with a standard feedback (PID controller). The anticontrol of chaos feedback (a combination of anticontrol of chaos and PID standard controller) is capable of simultaneously achieving low spectral emissions while maintaining minimal ripple of both the output voltage and the inductor current. Mosfet fast and non-linear switchings cause thermal stress. We propose in this study to investigate the correlation between the lifetime of a C2M0080120D Mosfet [

54] and its thermal stress due to the anticontrol of chaos and the switching frequency variation. The reduction of the current ripple enhances the Mosfet junction thermal performances. A step-by-step process establishes the electro-thermal model of the Mosfet integrating power losses (which includes the conduction, switching losses, diode conduction and reverse recovery losses). Finally, the Miner’s model accumulated stress of the Mosfet is quantified evaluating the number of failure cycles by the Coffin–Manson equation and the thermal cycles numbers using the rainflow counting algorithm. Then, the accumulated fatigue shows an insignificant degradation of the Mosfet lifetime with anticontrol of chaos feedback (in comparison to a standard controller) despite the fast switching of the Mosfet. Thus, this leads to the conclusion that using anticontrol of chaos does not degrade the remaining life (i.e. it has an insignificant aging effect) of the Buck converter’s semiconductor.

The main sections of this paper are:

Section 2 describes the behavior of a Buck converter both with a standard and anticontrol of chaos controller. In

Section 3, the Mosfet power loss calculations and thermal model are detailed. Then, in

Section 4, the lifetime model estimating the damage on a Mosfet is presented. The paper concludes in

Section 5.

2. Nonlinear Behavior of a Buck Converter

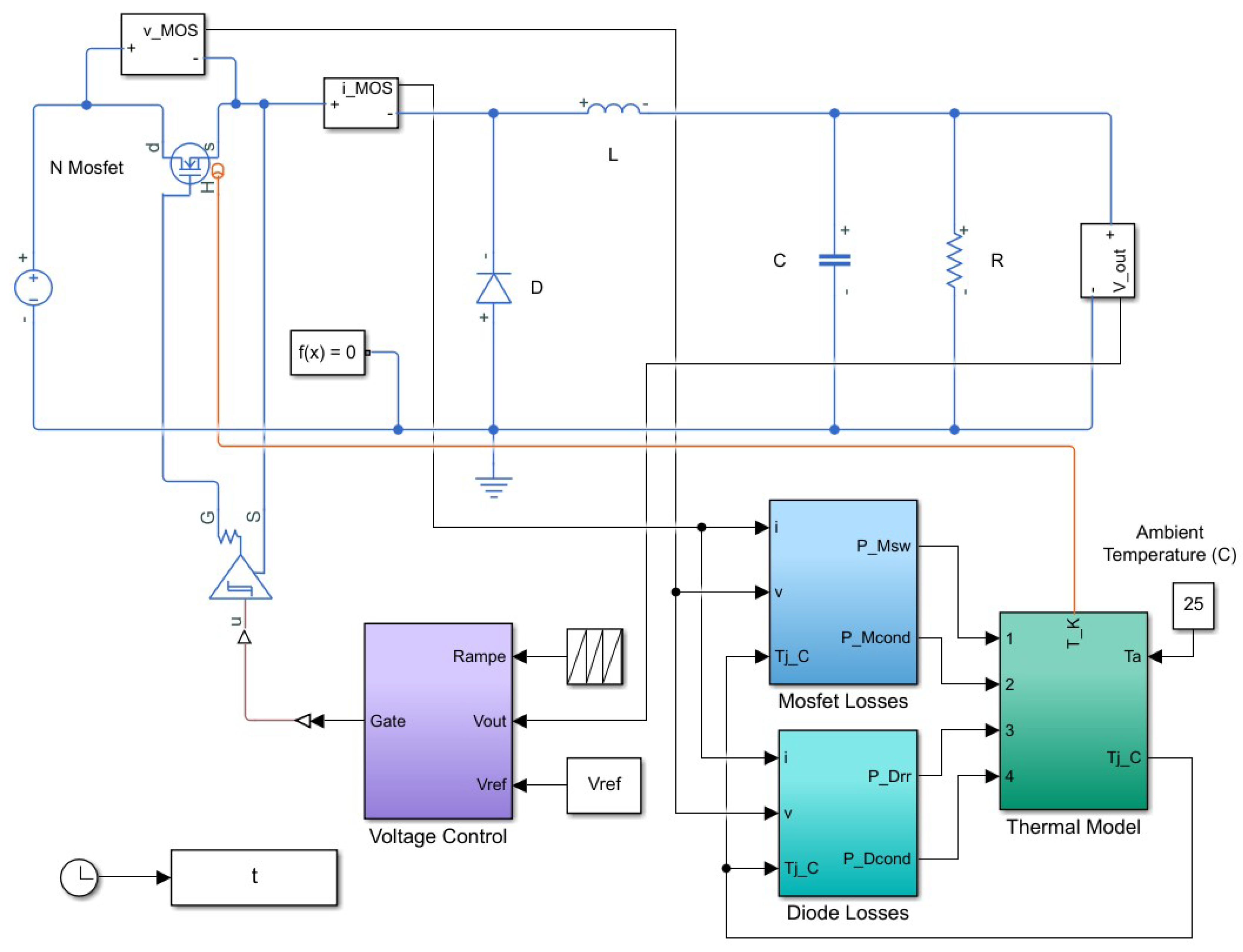

In this paper, our study is focused on a Buck converter, which topology is shown in

Figure 1. The circuit consists of an inductance

L, a diode

D, a Mosfet switch (C2M0080120D), a capacitance

C and a load

R. The output voltage

tracks the reference signal

, ensuring the desired stabilized output voltage.

When the Mosfet is in on-state, the energy is stored in the inductance L and in the capacitance C and no current flows through the diode D. When the Mosfet is in off-state, the diode now conducts, ensuring a path for the inductor current . The Buck converter uses a periodic switching to step down the input voltage . This is achieved by controlling the power Mosfet using a pulse width modulated signal. This signal is generated using the error amplifier (i.e. the deviation between the output voltage and a reference voltage), a Proportional Integral Derivative (PID) controller and the ramp input voltage (characterized by and ) to adjust the duty cycle of the switch.

Despite the continuous advances in control theory, the PID controller still is the most popular control technique employed in feedback control for regulating the output voltage of Buck converters. The standard structure of the controller is as follows:

where

P,

I,

D and

N are the proportional, the integral, the derivative and the filter coefficients. The parameters of the converter are selected to achieve the desired output voltage.

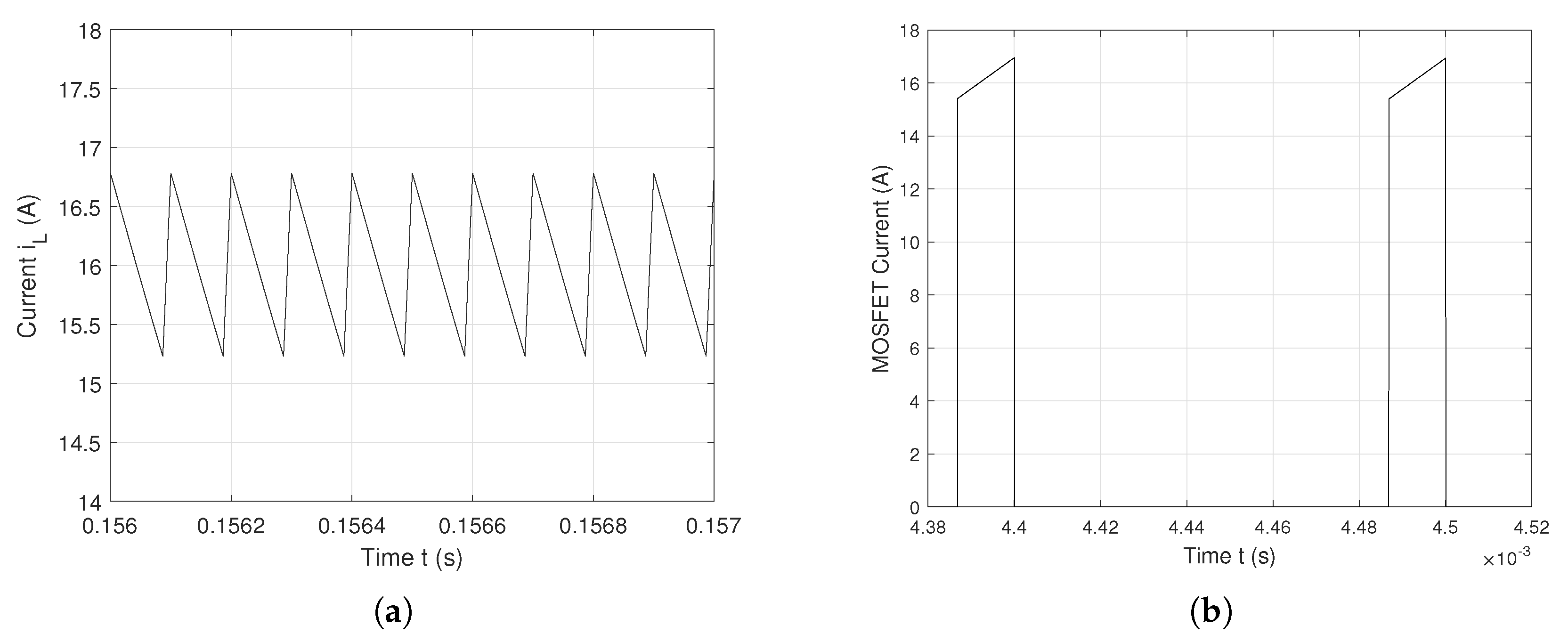

The inductance current

and the Mosfet current of this circuit are generally periodic at the switching frequency

(

f=10 kHz), as shown in

Figure 2. The simulation results show that

and Mosfet current increase from 15.25 A to 16.75 A when the Mosfet is in on-state. Consequently, the Mosfet mean current is 16 A, with a ripple of 1.5 A. If the Mosfet is in off-state,

decreases, meanwhile the Mosfet current is zero.

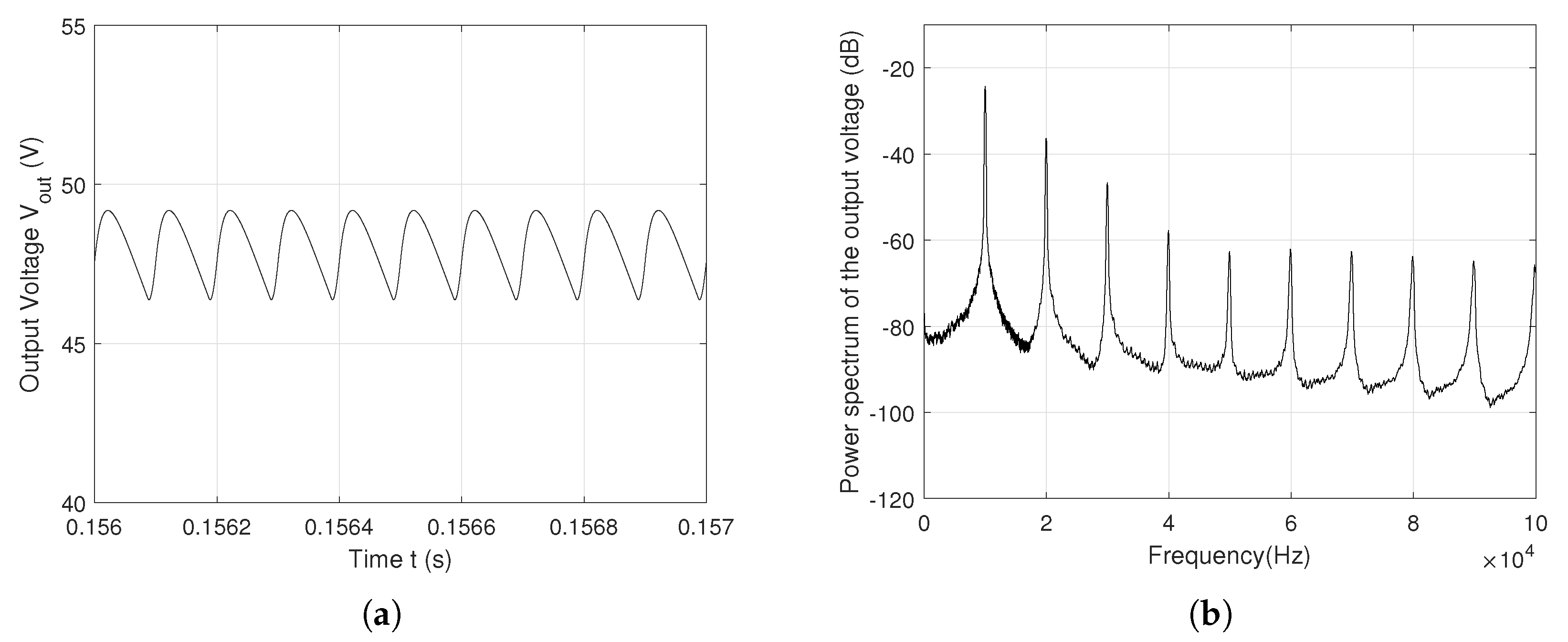

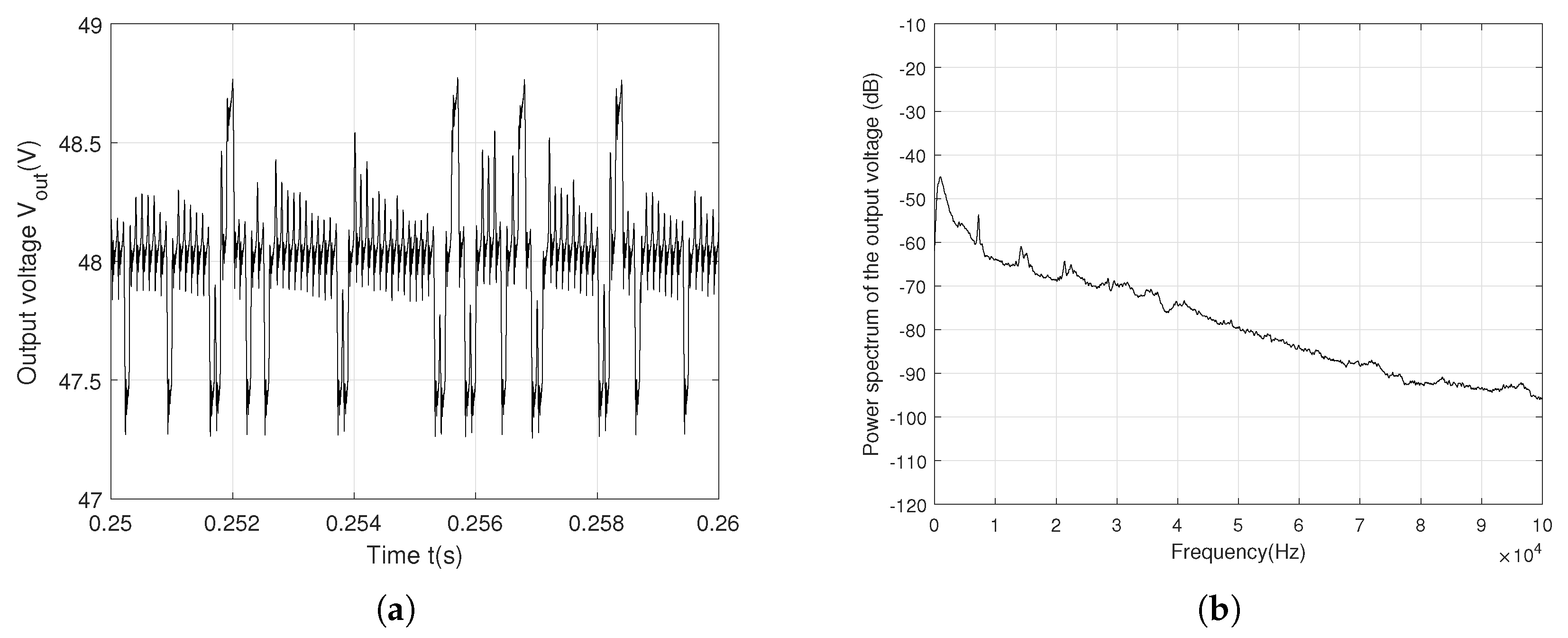

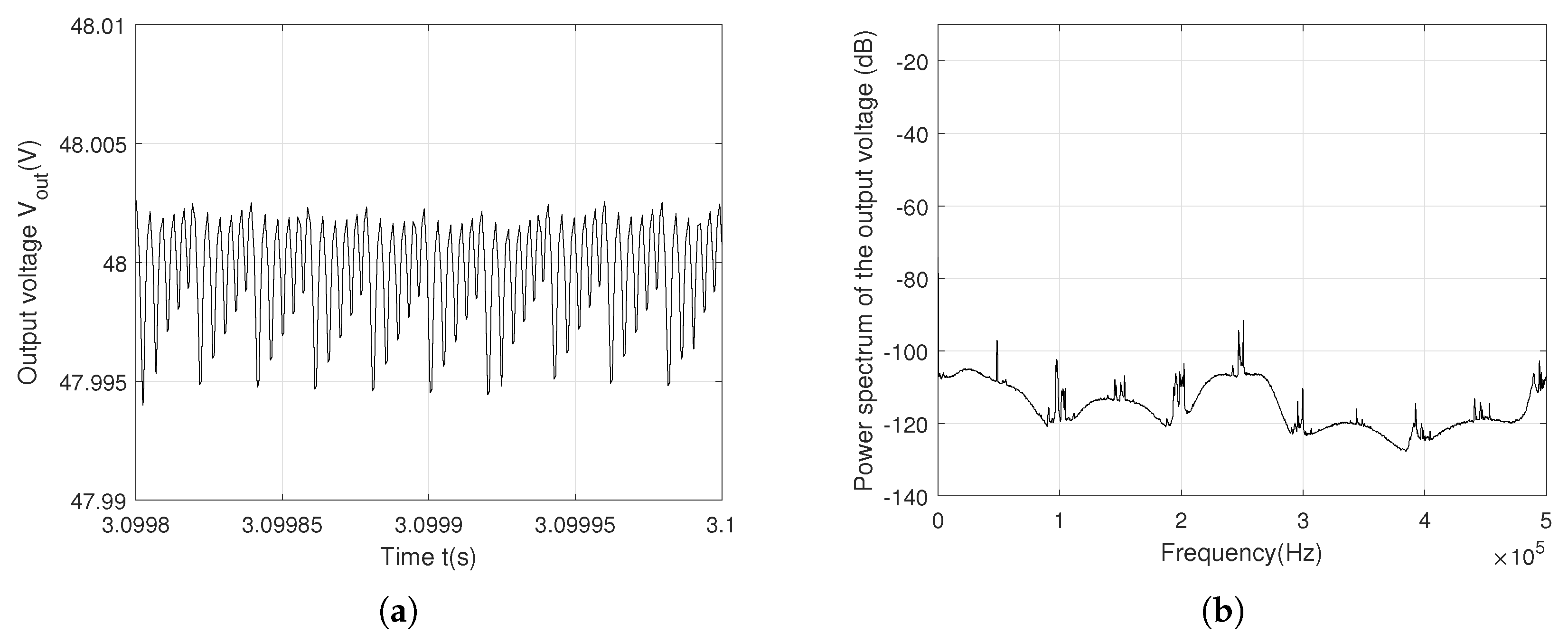

Figure 3(a) shows the periodic output voltage

with a 2.5 V ripple. Its spectrum, shown in

Figure 3(b), corresponds to the converter governed by the control law of Equation (

1). The spectrum consists solely of the fundamental frequency, characterized by a sharp peak at

, with a magnitude of -25 dB, and its harmonics.

Now, let us introduce the controller with the following control law:

This time, the controller (

2) includes, in addition to PID, a nonlinear feedback controller, with a multiplication of the

feedback introducing the chaos voluntarily. The amplitude and frequency of the resulting control signal dictate the number of switching cycles of the MOSFET.

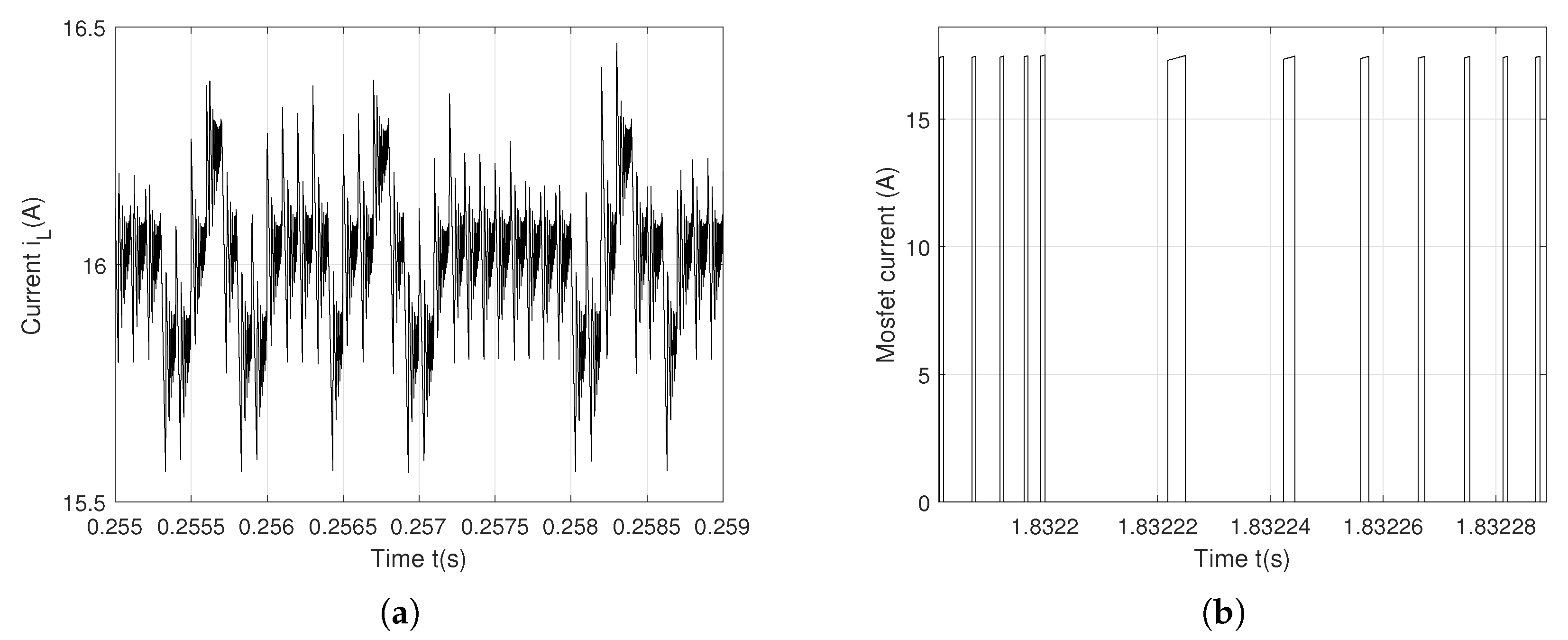

Figure 4 present the simulation results for

and the Mosfet current obtained with the controller (

2).

and Mosfet currents vary irregularily between 15.6 A to 16.4 A. Consequently, the Mosfet mean current is 16 A, with a very small ripple of 0.8 A. The Mosfet switches much more frequently that in the previous case (when the converter operates under the control law of Equation (

1)), but not periodically any more. This allows to maintain a small ripple of

.

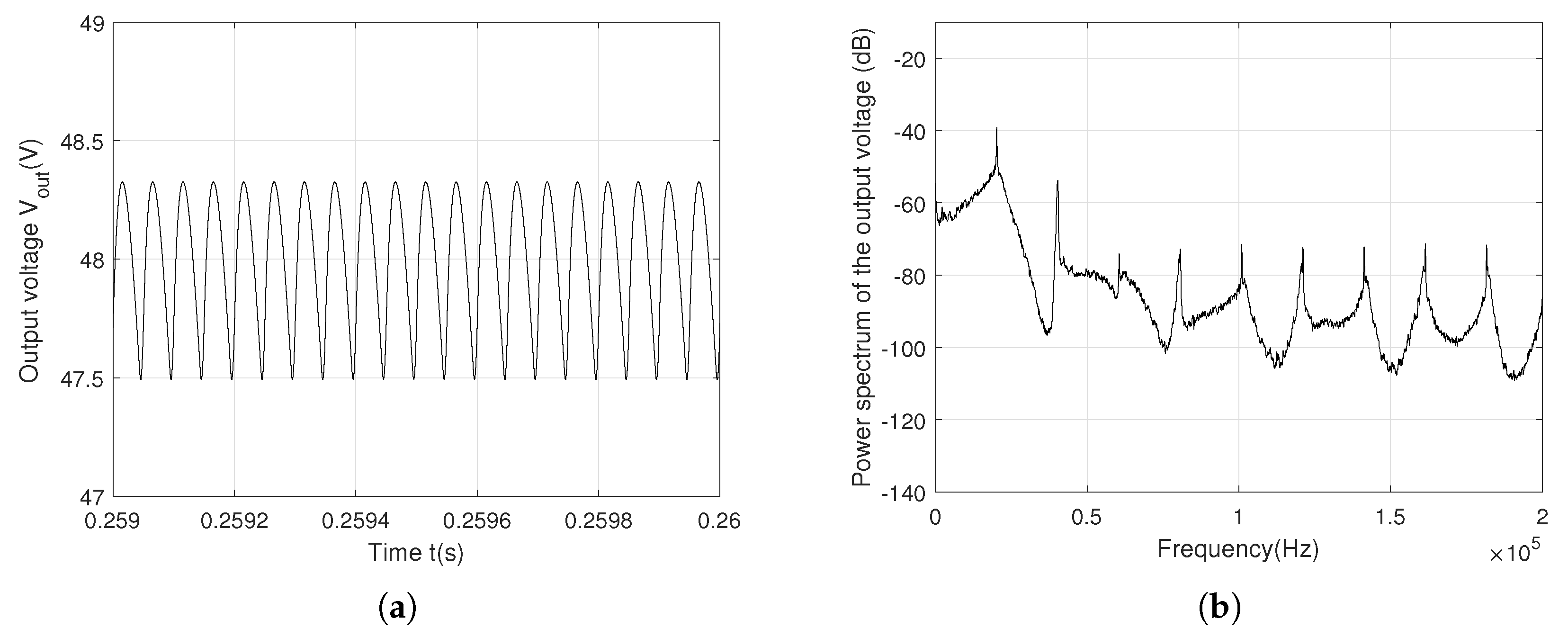

The output voltage

is now chaotic, with a 1.8 V ripple, as shown in

Figure 5(a). Therefore, the influence of the controller (

2) on the ripple is not negligible.

Figure 5(b) represents the power spectrum of

with a peak of -46 dB magnitude at the switching frequency

.

The various frequencies in stem from its highly irregular waveform, caused by the intrinsic nonlinear dynamics. These dynamics are driven by the varying on and off durations of the MOSFET switch within each ramp period T. Generally, the power spectrum represents the frequency components at a height given by the peak amplitude of at different frequencies. The link between the ripple and power spectrum magnitude explains the decrease of the peak magnitude from -25 dB to -49 dB. Therefore, the anticontrol of chaos improves the spectral emissions by further reducing spectral peaks. We observe that the spectrum is no longer composed of a single peak at the switching frequency (or its harmonics). Instead, numerous spectral lines appear, with a continuous power spectrum characteristic of chaos. Naturally, the reduction in the maximum of the power spectrum is achieved by the presence of chaos, increasing the converter’s switching frequency. As a result, exhibits improved frequency-domain (spectral) and time-domain (ripple) performance compared to the first case.

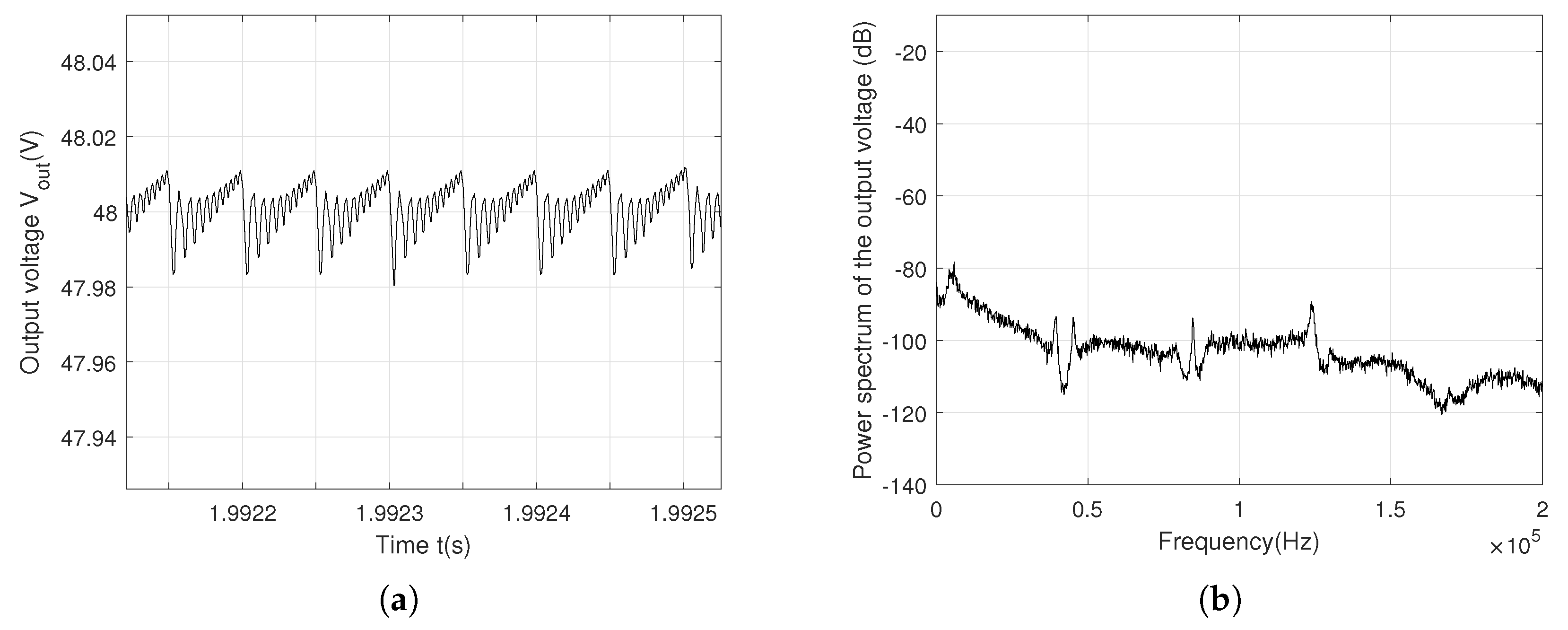

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the periodic and the chaotic output voltage

with

f = 20 kHz. The influence of the control law (

2) and the switching frequency

f reduce more that 96% the ripple of

from 0.8 V to 0.025 V. The chaotification of the feedback decreases the power spectrum of

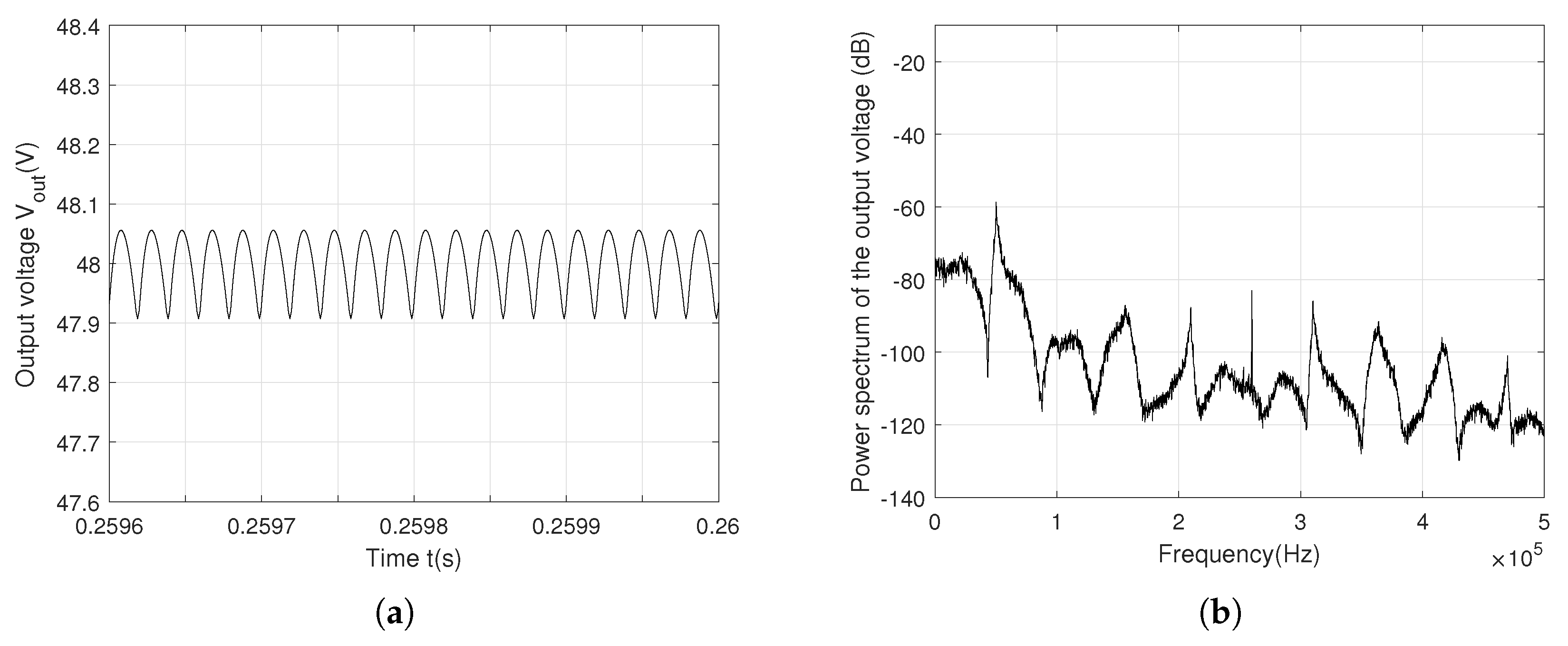

to -79 dB, to be compared to the -40 dB with a periodic behavior. A further increase switching frequency at

f = 50 kHz leads to the same trend:

ripple is 0.15 V with a periodic behavior and 7.5 mV with a chaotic behavior. The maximum of the power spectrum is reduced from -60 dB to -98 dB as shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

Table 1 summarizes

ripple and power spectrum of the output voltage, using the control laws of Equation (

1) and Equation (

2) as feedback. The control law of Equation (

1) leads to a large ripple. Chaotifying the converter with the proposed control law of Equation (

2) as feedback ensures a good ripple and causes a spectacular decrease of the power spectrum amplitude. Finally,

Table 1 shows that the power contained in the peaks harmonics of the output voltage decrease at different frequencies

f = 10 kHz, 20 kHz and 50 kHz.

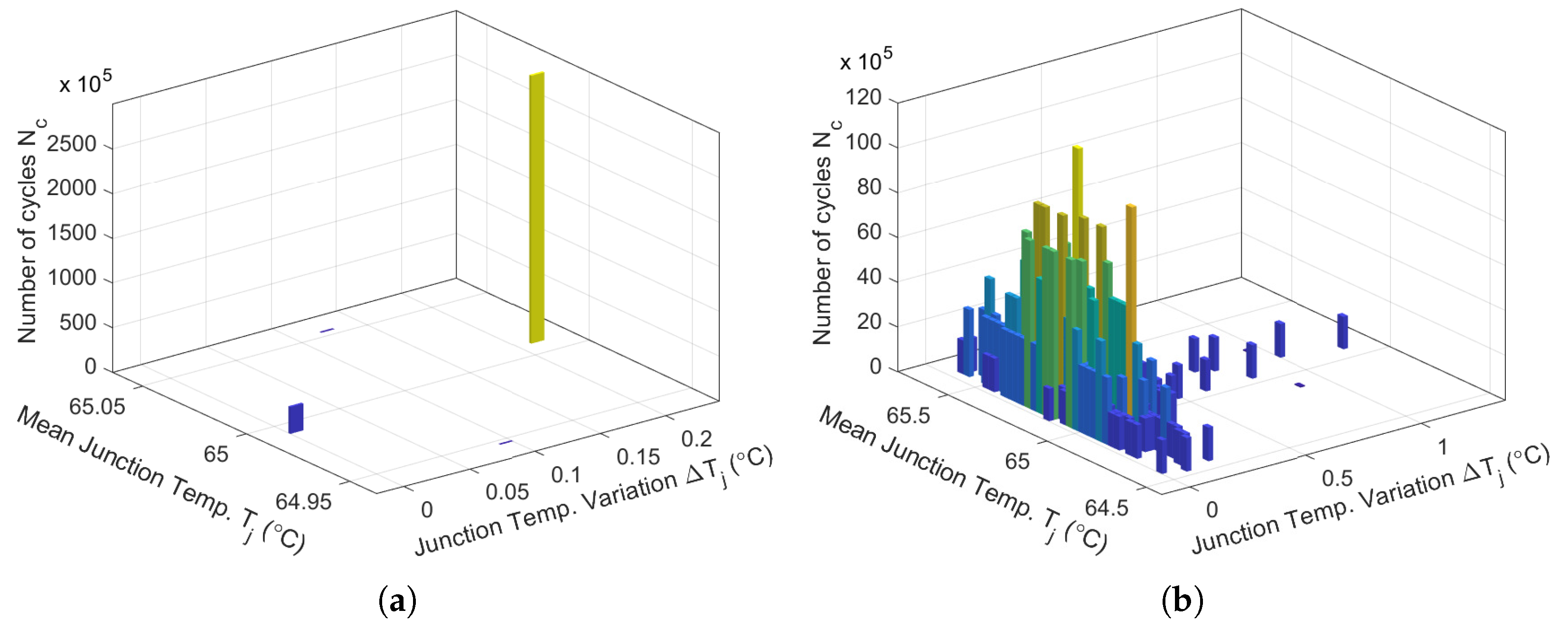

4. Remaining Life Estimation

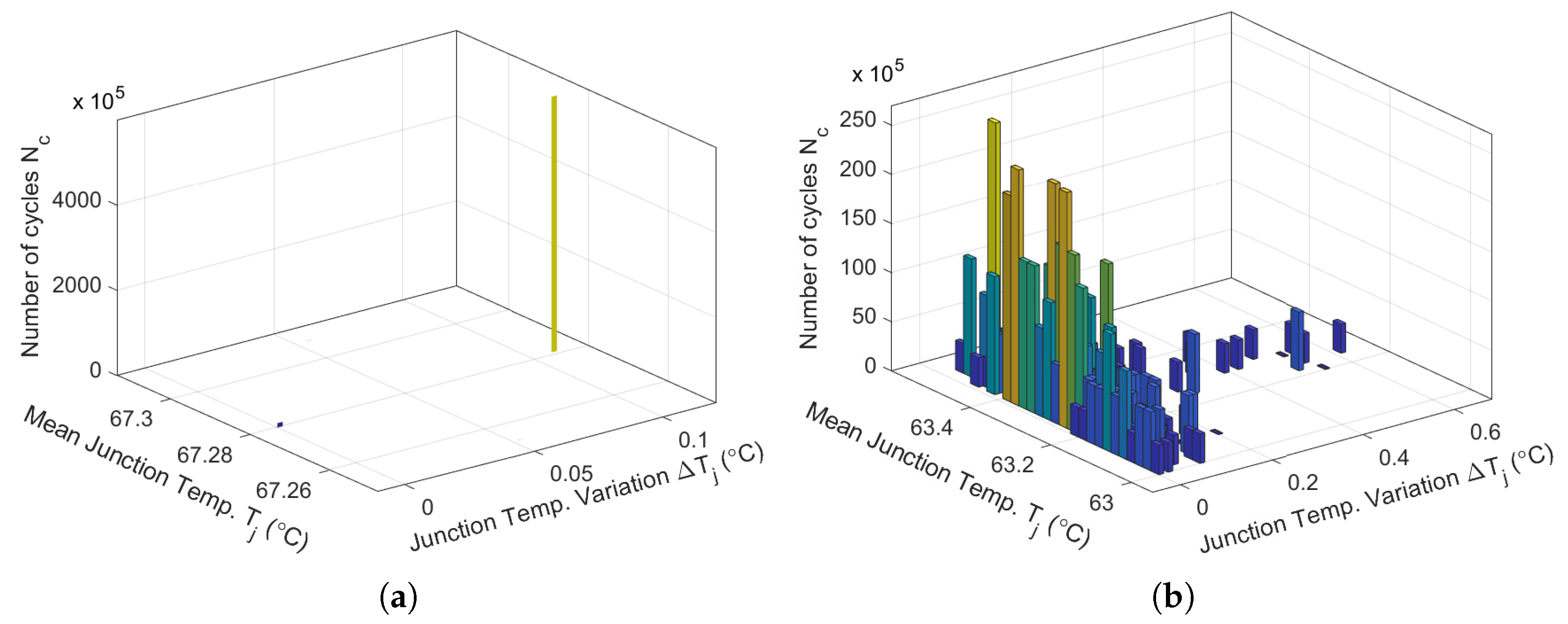

A thermal cycle counting algorithm is applied to the junction temperature in order to predict the power Mosfet remaining life. The most widely used algorithm is rainflow counting: it converts the time series of the junction temperature into a number of cycles, thereby facilitating lifetime prediction. In

Figure 16(a), the rainflow histogram presents one value of

thermal cycles of 3000×

due to the

periodicity. However, if the time series of the junction temperature is irregular or chaotic, the result of the rainflow counting algorithm is a set of organized cycles

with a maximum of 120×

, as in

Figure 16(b).

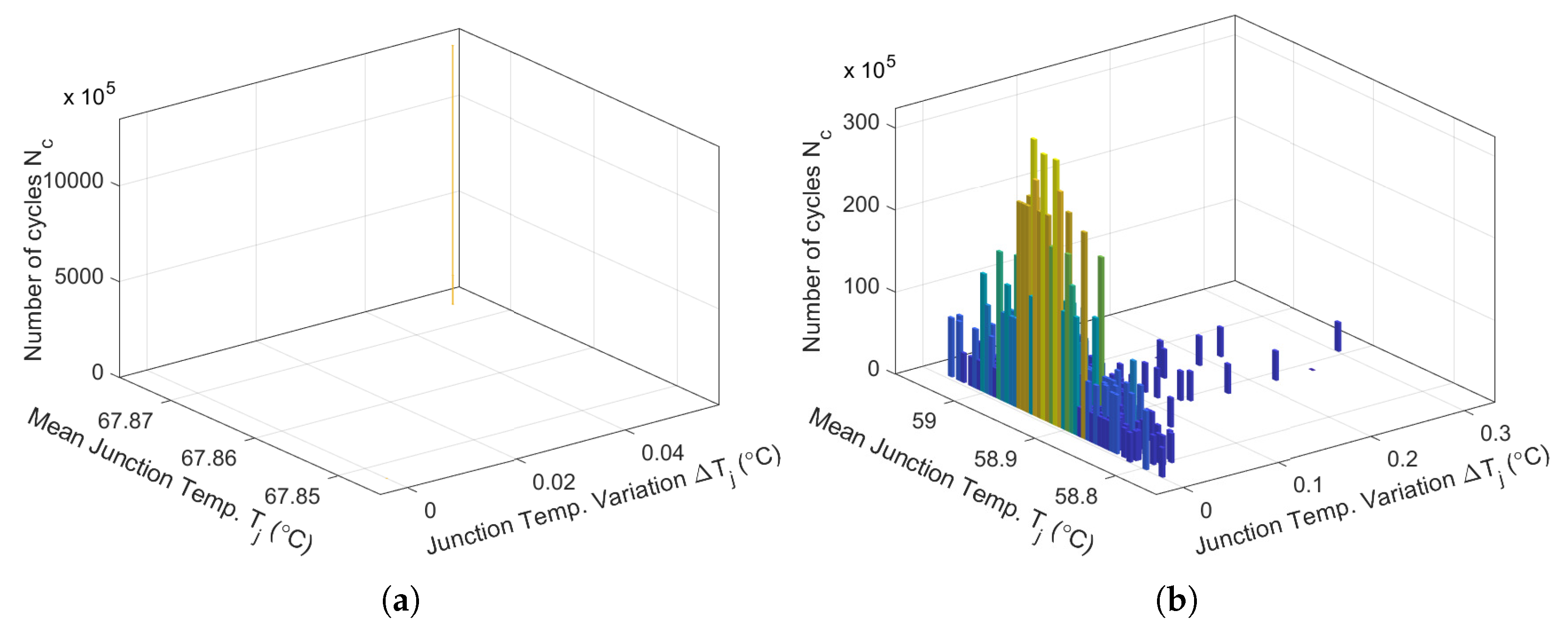

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 present the thermal cycles of the stable and chaotic behaviors of junction temperature

at others frequencies

f = 20 kHz and 50 kHz.

These results are used to derive the Mosfet accumulated fatigue

Q using the Miner’s rule. It is expressed as:

where

represents the number of cycles calculated using the rainflow counting algorithm, and

is the number of cycles to failure. For the estimation of the device failure cycles, the Coffin–Manson equation is employed. It can be written as:

where

is the activation energy,

A and

are experimental coefficients and

k is the Boltzmann constant (8.617×

eV/K). As in [

53], the next numerical values are obtained:

= −4.4887,

= 0.0667 and

A = 2.8823 ×

for a C2M0080120D Mosfet. With these coefficients and according to relation (

9), the number of cycles to failure is: for the stable period-1

T behavior

=3.9064×

cycles calculated for

=

C and a extremely small

= 0.

C; for the chaotic behavior, according to

= 65.

C and

= 1.

C,

is found to be 1.2548×

. The degradations of the C2M0080120D Mosfet device at others frequencies are summed up in

Table 2.

The accumulated fatigue is insignificant for a stable period of the junction temperature , indicating a small impact on the remaining life of Mosfet. However, only minimal damage is observed when the anticontrol of chaos feedback is applied. The repercussions of the chaotic temperature are insignificant for the Mofset thermal stress and reliability performance. The accumulated fatigue results shows the low and high frequency thermal cycles contribute in the same way to the aging of the Buck converter’s semiconductor.

Figure 1.

The Buck converter operates with feedback control, and its parameters values are as follows: = 400 V, L = 3 mH, C = μF, = 8 V, = 3 V, T = μs, P = 0.1, I = 1200, N = 100, = 48 V.

Figure 1.

The Buck converter operates with feedback control, and its parameters values are as follows: = 400 V, L = 3 mH, C = μF, = 8 V, = 3 V, T = μs, P = 0.1, I = 1200, N = 100, = 48 V.

Figure 2.

Plots of (a) and (b) Mosfet current with a stable period-1T operation (f = 10 kHz).

Figure 2.

Plots of (a) and (b) Mosfet current with a stable period-1T operation (f = 10 kHz).

Figure 3.

Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 10 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 3.

Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 10 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 4.

Plots of (a) and (b) Mosfet current with a chaotic behavior (f = 10 kHz).

Figure 4.

Plots of (a) and (b) Mosfet current with a chaotic behavior (f = 10 kHz).

Figure 5.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 10 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 5.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 10 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 6.

(a) Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 20 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 6.

(a) Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 20 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 7.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 20 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 7.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 20 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 8.

(a) Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 50 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 8.

(a) Output voltage with a periodic behavior (f = 50 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 9.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 50 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

Figure 9.

(a) Output voltage with a chaotic behavior (f = 50 kHz); (b) Power spectrum of .

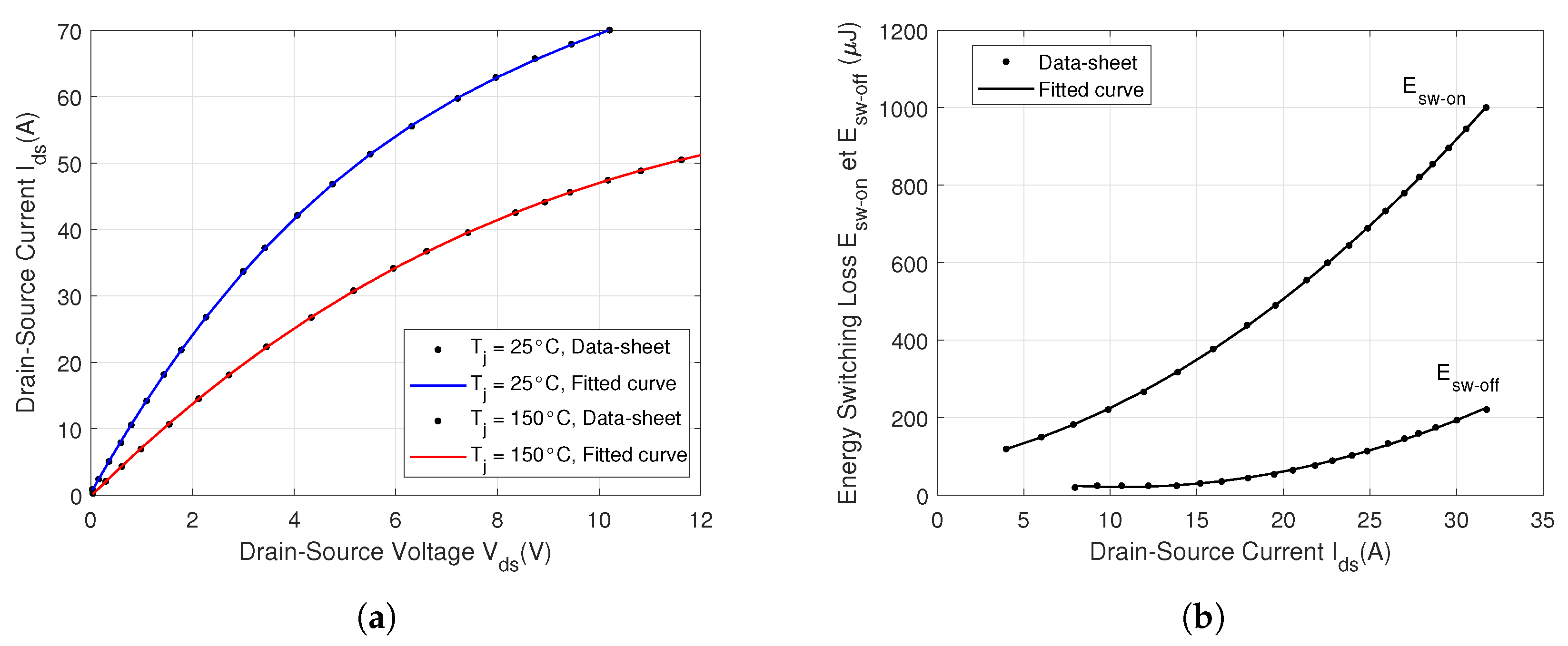

Figure 10.

Fitting curves of the static current–voltage characteristics - at C and C; (b) Mosfet energy power losses in function of the drain-source current , with = 800 V.

Figure 10.

Fitting curves of the static current–voltage characteristics - at C and C; (b) Mosfet energy power losses in function of the drain-source current , with = 800 V.

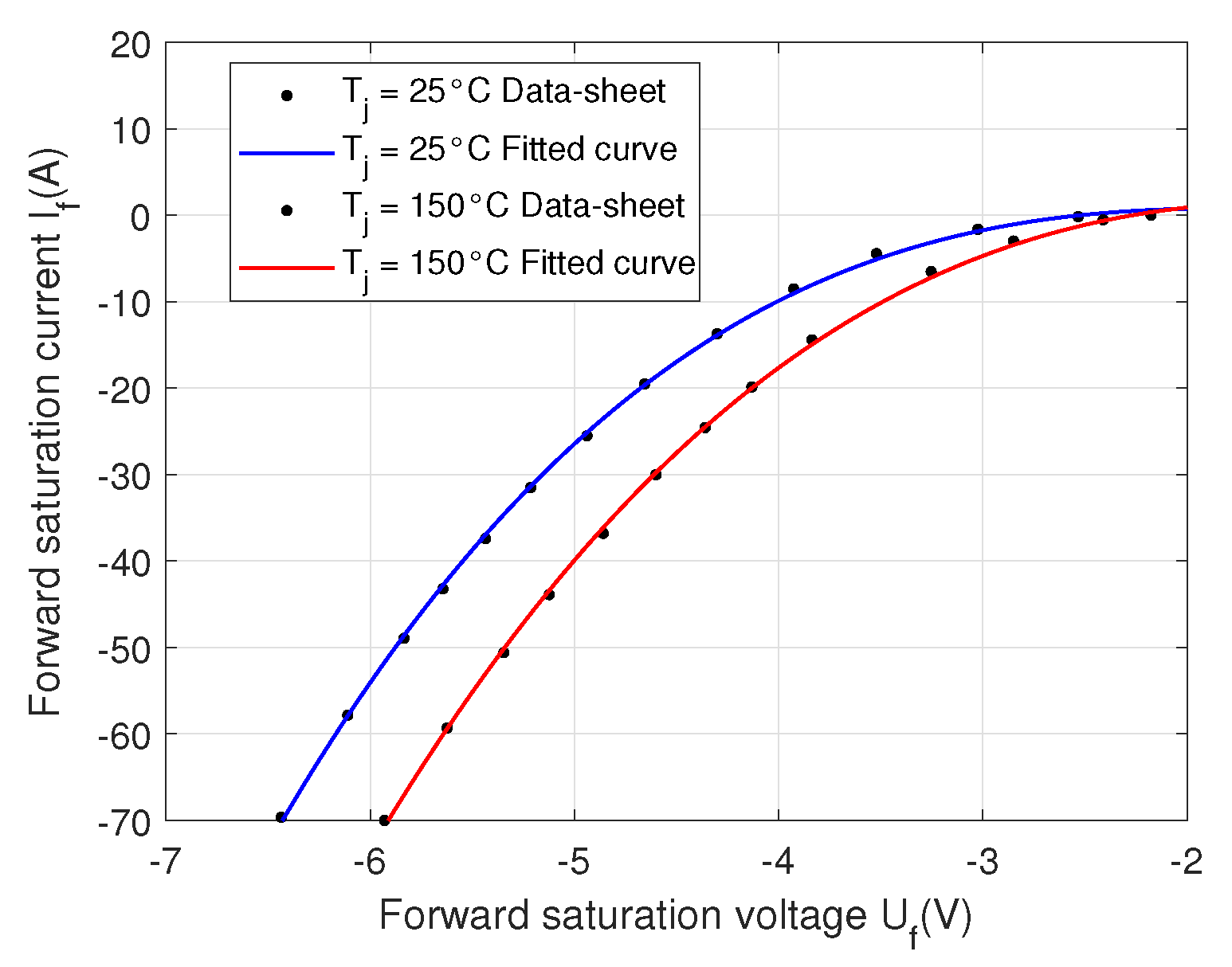

Figure 11.

Diode characteristics at = C and = C.

Figure 11.

Diode characteristics at = C and = C.

Figure 12.

(a) Comparison between the transient thermal impedance curves obtained through simulation and those provided in the datasheet; (b) Simulink model of the Foster network.

Figure 12.

(a) Comparison between the transient thermal impedance curves obtained through simulation and those provided in the datasheet; (b) Simulink model of the Foster network.

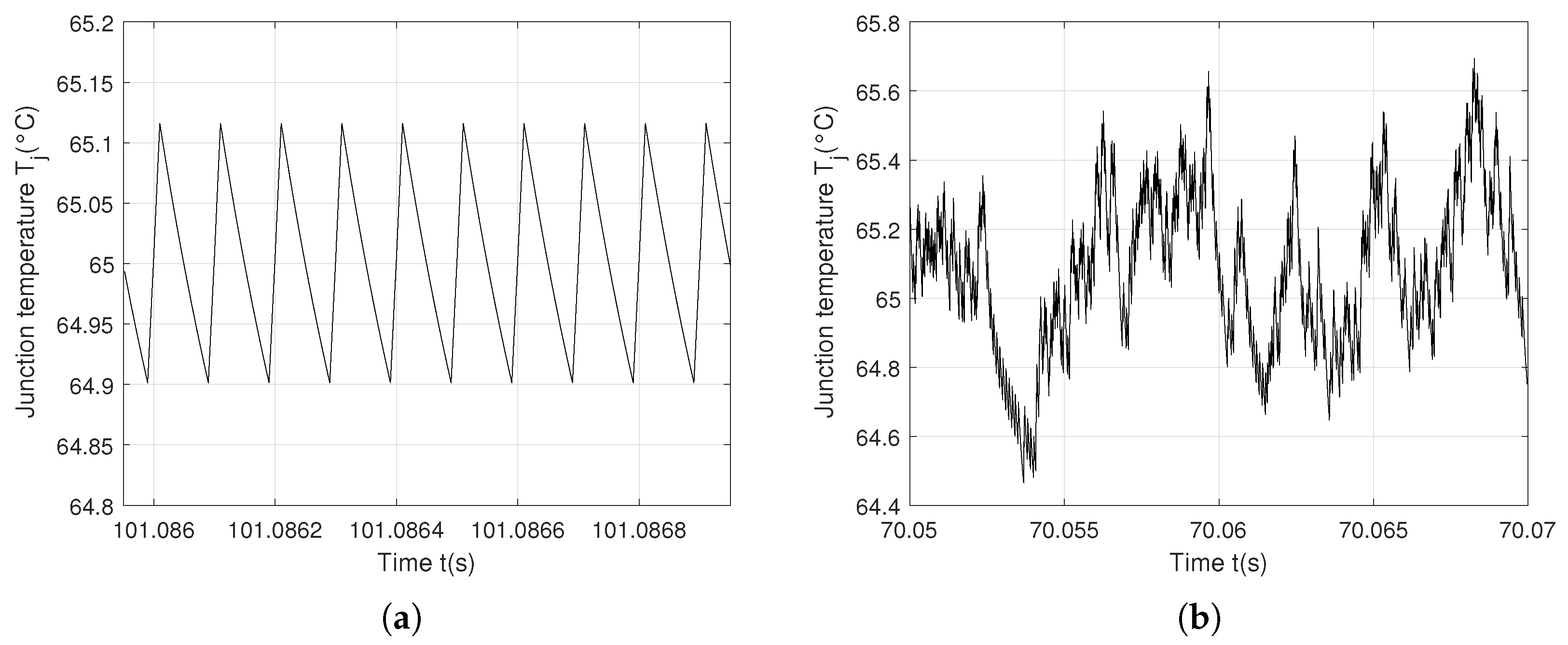

Figure 13.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 10 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

Figure 13.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 10 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

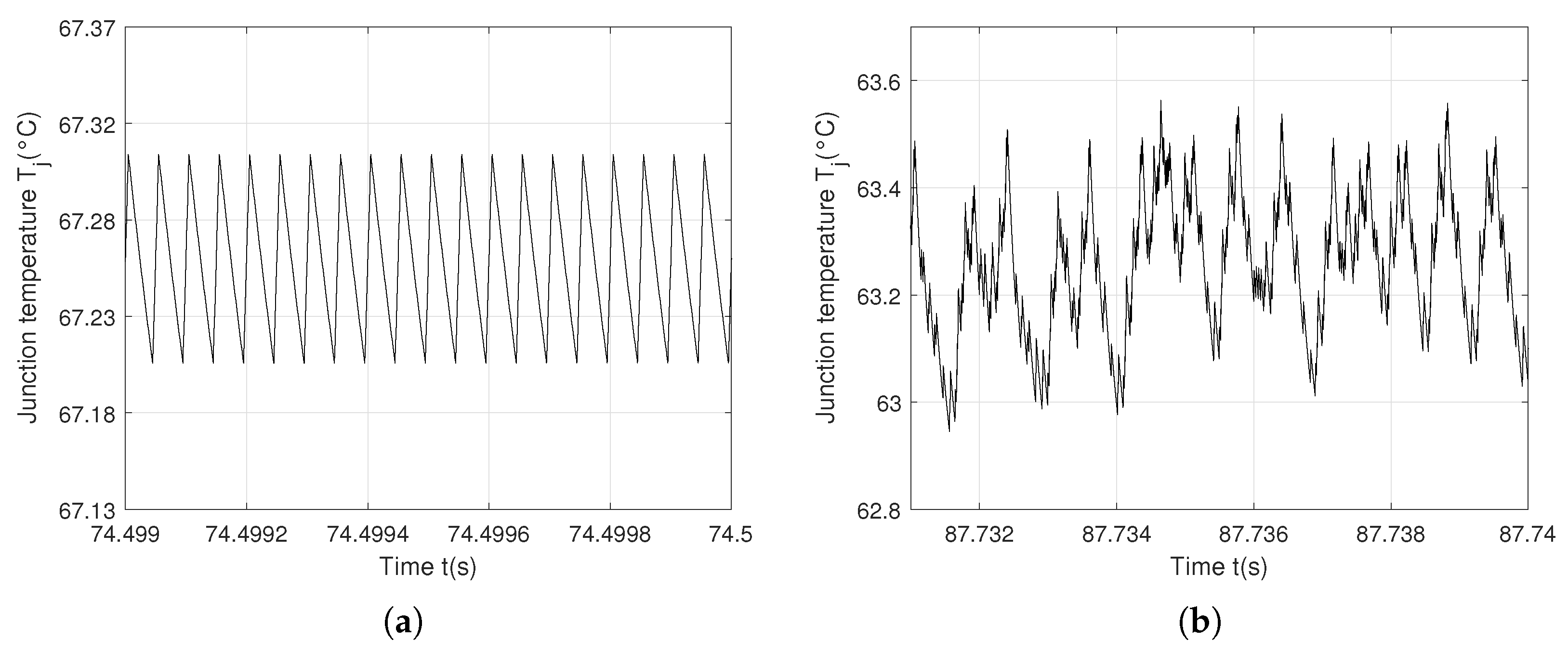

Figure 14.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 20 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

Figure 14.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 20 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

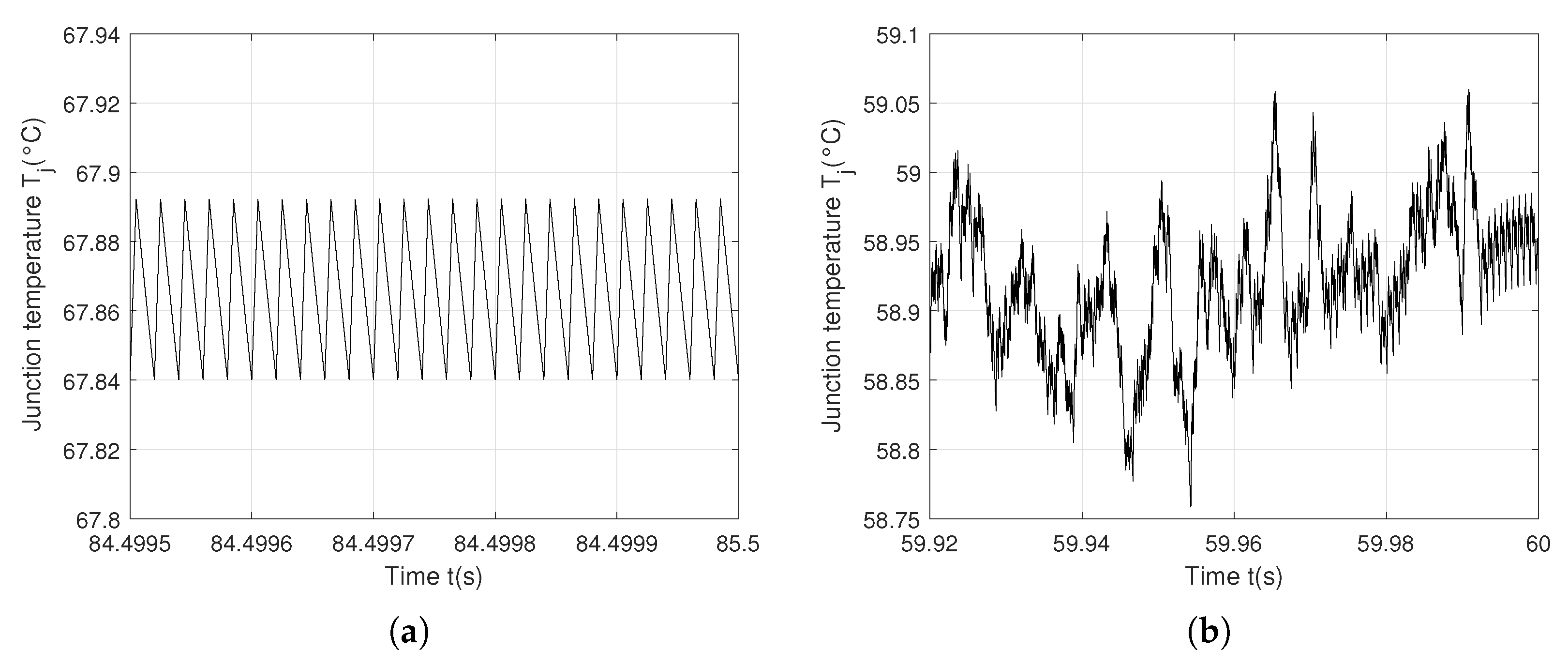

Figure 15.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 50 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

Figure 15.

Junction temperature

with the switching frequency

f = 50 kHz: (

a) Periodic behavior using the controller (

1); (

b) Chaotic behavior using the controller (

2).

Figure 16.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a periodic behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Figure 16.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a periodic behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Figure 17.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a stable period-1T behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Figure 17.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a stable period-1T behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Figure 18.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a periodic behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Figure 18.

(a) Thermal cycles considering and for a periodic behavior; (b) Thermal cycles considering and for a chaotic behavior obtained with the rainflow counting algorithm.

Table 1.

Ripple and maximum of power spectrum results for the study cases.

Table 1.

Ripple and maximum of power spectrum results for the study cases.

| Behavior |

Controller |

Switching frequency |

Ripple |

Maximum of power spectrum |

|

|

10kHz |

2.5 V |

-25 dB |

| Stable 1T-period |

PID |

20kHz |

0.8 V |

-44 dB |

| |

|

50kHz |

0.15 V |

-60 dB |

|

|

10kHz |

1.8 V |

-45 dB |

| Chaotic behavior |

Anticontrol of chaos + PID |

20kHz |

0.025 V |

-79 dB |

| |

|

50kHz |

0.0075 V |

-98 dB |

Table 2.

Accumulated fatigue results for the study cases.

Table 2.

Accumulated fatigue results for the study cases.

| Behavior |

Switching frequency |

Mean of

|

Variation

|

Number of cycles

|

Accumulated fatigue |

|

10kHz |

C |

0.C |

|

7.% |

| Periodic behavior |

20kHz |

67.C |

0.C |

|

4.% |

| |

50kHz |

67.C |

0.C |

|

6.% |

|

10kHz |

65.C |

1.C |

|

4.% |

| Chaotic behavior |

20kHz |

63.C |

0.C |

|

4.% |

| |

50kHz |

58.C |

0.C |

|

2.% |