1. Introduction

The mention of turbulence immediately brings to mind a saying: turbulence is one of the most challenging problems in physics and is known as an "unsolved problem in the classic physics." Historically, some renowned physicists and mathematicians, such as Werner Heisenberg, Richard Feynman, and Andrei Kolmogorov, dedicated their wonderful lives to the problem of turbulence without solving it. It is even said that the famous physicist Horace Lamb hoped to ask God about turbulence after reaching heaven [

1,

2]. From the perspective of quantitative analysis, the daunting scientific problem of turbulence began in 1895 with Reynolds [

3] attempting to study the Navier-Stokes equations for viscous fluids using average statistical methods, namely Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, which has been ongoing for 130 years. Over these 130 years, it can be said that all available mathematical tools and computational resources have been employed to study the Navier-Stokes equations for viscous fluids, yet no fundamental progress or breakthrough has been made [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Since the establishment of the Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, due to the needs of numerous engineering applications, a variety of approximation methods have been employed to close the Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equation set. Various models have been proposed for the Reynolds stresses [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Is it possible to establish a universal closure turbulence model theory that can predict turbulent motion across various scales? Unfortunately, after 130 years of collective effort, such a theory has yet to be established. On the contrary, the numerous models proposed to date have all relied on non-rigorous hypotheses usually based on experimental observations and have their own limitations [

17,

18,

19].

Although direct numerical simulation (DNS) has made gratifying progress [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24], and in recent years, the use of big data and AI to study turbulence has emerged, the essence of turbulent motion has not yet been revealed. Standing at the dawn of the AI era and looking to the future, we want to loudly ask, where is the path to solving turbulence? Is it only possible to unravel the mysteries of turbulence through large-scale numerical simulations when quantum computers are developed? Over the past 130 years of numerical simulations, regardless of the computational strategy, a fundamental fact is that all simulations are based on the Navier-Stokes equations, as it is believed that they encompass all the information of turbulent motion [

2,

8,

15,

17,

18,

25,

26]. Now, we are faced with two lines of thought: one is to continue on the path based on the Navier-Stokes equations, and the other is to return to the origin, to re-examine the equations of fluid motion from the starting point of their establishment, that is, to reflect on whether the Navier-Stokes equations need to be further refined and improved to encompass both turbulent and laminar motion without using the Reynolds statistical averaging methods [

3].

To cast aside the clouds and see the sun, let us take a general look back at the establishment of the equations of fluid motion. Euler played a crucial role in conceptualizing the mathematical description of fluid flow. He described the flow using a three-dimensional pressure and velocity field that varies in space, modeling the flow as a collection of continuous, infinitesimally small fluid elements. By applying the basic principles of conservation of mass and Newton’s second law, Euler arrived at two coupled nonlinear partial differential equations involving the flow fields of pressure and velocity. Although these Euler equations represent a significant intellectual breakthrough in theoretical fluid dynamics, obtaining their general solutions is a difficult task. Euler did not consider the effect of frictional forces on the movement of fluid elements; in other words, he ignored viscosity, and the Euler equations are not suitable for solving real flow problems. It was only a century after Euler that his equations were modified to account for the influence of frictional forces within the flow field. The resulting set of equations is a more complex system of nonlinear partial differential equations now known as the Navier-Stokes equations, initially derived by Navier in 1822 [

27] and later independently by Stokes in 1845 [

28]. That is, the Navier-Stokes Equations (system): the momentum conservation equation:

, and the incompressible mass conservation equation:

, where

is the flow velocity field,

p is the flow pressure,

t is time,

is the constant mass density, and

is the kinematic viscosity,

,

and

is spatial coordinates. To this day, the Navier-Stokes equations remain the gold standard for the mathematical description of fluid flow. Unfortunately, their general analytical solutions have not yet been found [

29,

30,

31].

In 1895, Reynolds studied turbulent motion using statistical averaging methods, decomposing the fluid velocity into the sum of mean velocity

and fluctuating velocity

, that is,

. By time-averaging the Navier-Stokes equations, he obtained the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, which are expressed as

, with the hope of obtaining the average values of important parameters in fluid motion. However, due to the appearance of the fluctuating velocity correlation term

(termed Reynolds stress but is not a stress at all! [

19]) in the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, which are not closed in themselves.

It is not difficult to notice that various turbulence models are all based on the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, with the aim of guessing the relationship between the turbulent viscosity coefficient and the mean velocity field from different perspectives using the Boussinesq hypothesis , where k is the turbulent kinetic energy density. In other words, the Boussinesq hypothesis essentially treats as a kind of stress and, by mimicking the linear constitutive relationship of Newtonian viscous fluids, artificially constructs a possible relationship between and the mean flow velocity. The reason why people propose various models for is that they believe turbulence is caused by , which is actually a misconception.

In fact,

originates from the convective term in the fluid motion acceleration, which is

, and is produced by the Reynolds averaging process. That is,

. Using the mass conservation relationship

, the Reynolds average of the fluid motion acceleration can be rewritten as

. This means that the generation of

has nothing to do with fluid viscosity; it is merely the projection of fluid velocity onto its velocity gradient. In fact, the inviscid Euler equation

(

is omitted for inviscid flow) will also produce

after Reynolds averaging. Therefore, George [

18] stated that

is not a stress at all, but simply a re-worked version of the fluctuation contribution to the nonlinear acceleration terms. And we know that inviscid fluids cannot generate turbulent motion, so it can be said that

is not the cause of turbulence.

So what is the cause of turbulence? This is a core issue in fluid mechanics. Although we are not yet able to predict the occurrence of turbulence with complete accuracy, we do know under what circumstances turbulence will definitely not occur, and that is in the flow of inviscid fluids, which cannot be turbulent. Currently, our understanding of turbulent flow can be macroscopically stated as follows: the interaction between fluid viscosity and velocity gradients is the main cause of turbulence. Viscosity causes the flow with non-zero velocity gradients to produce vorticity, leading to fluid rotation. Due to mass conservation, the fluid must replenish the mass that flows out. Additionally, the nonlinear modulation of the convection term makes the motion pattern very complex. When the velocity gradient is very small, the flow is mainly laminar; when the velocity gradient is very large, the flow is mainly turbulent.

Within the current framework of the Navier-Stokes equations, only one term, , in the Navier-Stokes equation contains the viscosity coefficient and the derivative of the velocity gradient , which is the divergence . Unfortunately, because , after Reynolds averaging, the divergence only retains the mean field , without including the fluctuating components. This may imply that the Navier-Stokes equations established based on , and , may not include the complete information of viscous fluid motion and are imperfect, necessitating a modification. Since is derived from the linear constitutive relation of viscous fluids combined with the mass conservation condition , that is, , it is necessary to re-examine the constitutive relation of fluids in order to include the complete information of fluid motion.

To obtain the governing equations for turbulent flow, let’s derive the momentum conservation equation in fluid mechanics from the "first principles." The term "first principles" originates from ancient Greek philosophy, where Aristotle first introduced this concept in his work "Metaphysics." He believed that first principles are "the most basic propositions or assumptions that cannot be further derived," serving as the ultimate foundation for all knowledge and reasoning. That is, by returning to the essence of things, analyzing the most fundamental principles and assumptions, we can construct new cognitive frameworks or solutions. Elon Musk [

32] is a key figure who popularized this term. In an interview, he expressed high praise for the "first principles" thinking approach: "By using first principles, I distill the essence of things and derive from the most fundamental level..." "It is crucial to think from the perspective of first principles rather than relying on comparative thinking. We often fall into the habit of comparing and doing what others have done or are doing, which only leads to incremental improvements. The first principles thinking is to examine the world from a physicist’s perspective, stripping away the external appearance of things layer by layer to insights into their inner essence, and then building from the essence step by step." This is how Musk understands the "first principles thinking model" - tracing the roots of things and rethinking the way of action. The Navier-Stokes equations have been established for over 200 years since 1822, if we want to make breakthroughs, we must start thinking from scratch with the mindset of first principles.

2. General Equations of Motion for an Incompressible Viscous Fluid

We know that before introducing the fluid constitutive relation, the mass conservation equation for incompressible fluids is

, and the momentum conservation equation is:

. The momentum conservation equation can also be rewritten in the form of tensor total quantity as follows:

where

is the stress tensor,

are the components of the stress tensor,

are the unit base vectors in the Cartesian coordinate system, and

is the gradient operator and

is right gradient of the stress tensor

, whose computational rule is

, in general

. Equation (

1) is the most general form of the momentum balance equation for a continuum and can be applied to describe the motion of any continuum.

To obtain a closed set of governing equations, we need to introduce the fluid’s constitutive relation, which is the relationship between the stress tensor and the rate-of-strain tensor , namely , where is the rate-of-strain tensor, and its components are .

It should be noted that in the process of introducing the fluid’s constitutive relation, there is an element of human interpretation involved in understanding the physical properties of the fluid, which is the most subjective part in establishing the equations of fluid motion. From Navier to Stokes, it is assumed that the fluid is isotropic and incompressible, and a linear constitutive relationship between the stress tensor and the rate-of-strain tensor is hypothesized: , where is the viscosity coefficient. This constitutive relation was proposed in an era when there was no understanding of tensors and has been adopted by all subsequent literature. In the modern era, equipped with knowledge of tensors, we must ask whether the constitutive relationship between the stress tensor and the rate-of-strain tensor can be rationally expressed, and if so, what form it should take.

Assuming the fluid’s physical properties are isotropic, since both the stress tensor

and the rate-of-strain tensor

are second-order tensors, according to the tensor representation theory [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37], the most general expression for the constitutive relation of an incompressible fluid

can always be written as follows:

where

; the term

is not referred to by name in the literature; in this text, it is termed the second-order viscosity coefficient. From the thermodynamic entropy inequality, the inequality can be obtained as cited in [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]:

. By utilizing the Cayley-Hamilton theorem, this inequality can be further simplified to:

.

The fluid viscosity leads to the dissipation of energy, which is ultimately converted into heat. The energy dissipation per unit time for an incompressible viscous fluid is given by

where

represents the volume configuration of the fluid control body,

is double dot product of two tensor

and

with computational rule:

It is particularly worth noting that there is an issue that does not need to be hidden, which is the data problem of the physical parameter . Currently, there are no data available for the parameter , and it is a research topic that needs to be measured in the future.

In the literature of fluid mechanics, from Navier and Stokes to the present, fluids have been regarded as Newtonian fluids, using the linear constitutive relation

, without considering the second-order term

. As for why the second-order term

is not considered, there may be two reasons. The first is that during the time of Newton, Navier, and Stokes, the nonlinear effects were not observable, and there were no tools for tensor analysis, let alone tensor representation theory and the Cayley-Hamilton theorem [

38], which was published after formulation of the Naver-Stokes equations. The second reason is that even if one could obtain the expression Equation (

2), it was considered that the second-order term

is small enough to be negligible.

This paper argues that neglecting the second-order term

is a significant oversight in the establishment of fluid mechanics equations. Because the spatial variation of velocity, such as the velocity gradient near a wall, is very large, neither the first nor the second power of the velocity gradient can be omitted. This is analogous to the situation in the boundary layer. Prandtl [

39] stated when proposing the boundary layer theory that the Reynolds number

in

cannot be omitted, no matter how large

(or how small

) is, because the velocity gradient is so large that the entire term

cannot be neglected.

Bringing Equation (

2) into Equation (

1) allows us to derive the fluid motion equation that considers second-order viscosity:

wherein, the kinematic viscosity is

, and the kinematic second-order viscosity is

. Equation (

4) represents the most general equation of motion for viscous fluids. The viscosity coefficients

are generally functions of pressure

p and temperature

T, and they cannot be factored out of the gradient operator.

In most cases, the viscosity coefficients

do not vary significantly within the fluid and can be considered as constants. Under the incompressible condition

, Equation (

4) can be simplified to:

where the Laplacian

. In this way, we have improved the Navier-Stokes equation to Equation (

5), which is the most general equation of motion for incompressible viscous fluids. The term

includes the nonlinear combination of the fluid’s second-order viscosity and velocity gradients, which is the main cause of complex flow phenomena. Since Equation (

5) already includes higher-order terms of the velocity gradient, it can be directly used to simulate turbulence without the need to employ Reynolds’ statistical averaging method, which is the statistical decomposition of the fluid velocity.

Equation (

5) can be written in component form as follows:

It should be particularly noted that for problems with specific characteristic length

and characteristic velocity

, the dimensionless process of Equation (

5) not only yields the Reynolds number

, but Equation (

5) also generates a new dimensionless parameter, denoted as

. The parameter

arises due to the consideration of second-order viscosity. For a fluid with a given

, this parameter

is independent of the characteristic velocity and only related to the characteristic length

, or in other words, for flow problems of a given length scale, the parameter

affects the fluid motion for all characteristic velocity scale. Therefore, it is necessary to retain the second-order viscosity coefficient.

The tensorial Equation (

6) can be further expanded in conventional form, in the Cartesian rectangular coordinate system, denoting

,

,

,

,

, the three-dimensional fluid momentum equation can be read as follows:

where

and

The difference from the Navier-Stokes equations can be seen from the above equations, namely, each equation includes higher-order terms of the velocity gradient.

After using the continuity equation

the two-dimensional momentum equation is expressed as follows:

For heat conduction problems, it is assumed that there is a heat flux density

, where

T is the temperature and

is the thermal conductivity. The general equation of heat transfer is given by

where

s is the entropy density per mass [

7].

3. Boundary Layer Theory and Application to Wedge Flow

In 1904, Ludwig Prandtl [

39] introduced the concept of the boundary layer at the third International Congress of Mathematicians, suggesting that the influence of frictional forces is confined to a thin boundary layer near the surface of an object. Within the boundary layer, the velocity gradient is large, as is the shear stress, leading to frictional resistance that cannot be neglected. The boundary layer equations are much simpler than the Navier-Stokes equations and can be solved numerically [

40]. In particular, Prandtl discovered that the flow within the boundary layer is also turbulent [

41,

42], and in 1925, Prandtl proposed the concept of the mixing length to characterize the turbulent viscosity [

43], which can be used to derive the logarithmic law for the wall in turbulent boundary layers. This was a significant attempt to close the Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations.

In 1908, Prandtl’s student Blasius [

40] studied the problem of steady flat-plate boundary layers. A thin flat plate is immersed at zero incidence in a uniform stream with speed

and is assumed not to be affected by the presence of the plate, except in the boundary layer. The fluid is supposed unlimited in extent, and the origin of coordinates is taken at the leading edge, with

x measured downstream along the plate and

y perpendicular to it. Blasius [

40] performed a similarity transformation on Prandtl’s equations

and

and successfully obtained a numerical solution for the problem. In 2024, Sun [

44] studied unsteady laminar boundary layers and applied a similarity transformation to the equations

and

, successfully obtaining an exact solution for the unsteady flat-plate laminar boundary layer. This solution is primarily expressed in terms of Kummer functions, and other flow problems were also investigated.

Based on the Prandtl’s magnitude analysis and approximations as shown in

Table 1, we can obtain the boundary layer equations as follows:

in which, the underlined segment represents the manifestation of the second-order theory proposed in this paper, which is where it differs from Prandtl’s boundary layer equations. The exact solution of partial differential equation systems in Equation (

16) and Equation (17) can be easily solved by using Maple, the solutions of velocity components

and

are mainly expressed in terms of Lambert function [

46]: LambertW=

, which satisfies:

. As the equation

has an infinite number of solutions y for each (non-zero) value of

z, LambertW has an infinite number of branches. Exactly one of these branches is analytic at 0.

Note

and

, the Maple code of solving above partial differential equations is provided in Appendix A. Hence, denoting

, we have the general solutions of Equation (

16) and Equation (17) for

as below:

and

Although we have obtained the solution, it is regrettable that the integral in Equation (

18) cannot be calculated explicitly at the moment, making this solution less applicable. Let us try other methods below.

Introducing a stream function

and express the velocity components as follows:

, the mass conservation Equation (17) is satisfied, and the momentum conservation Equation (

16) becomes

and corresponding boundary conditions.

Applying Sun’s similarity transformations [

44]:

. Denoting

and

, and noting the

and

, and by the chain rule for derivatives, we can obtain some useful relations as follows:

. Thus the velocity components become

Substituting Equation (

21) and Equation (22) into Equation (

20), we have a single partial differential equation as follows

where the coefficients are

,

, and

and their relation

.

If the coefficient

,

and

were constants, then we have:

, where the exponent

. It is clear, for arbitrary

, that the Equation (

23) explicitly contains the coordinate

x, which cann’t be solved easily for arbitrary exponent

m.

In the case of wedge flow with velocity field:

, so that

, then

and

, and leads to a constant boundary thickness

. If we set

, the Equation (

23) becomes

and boundary conditions:

,

and

, where

is a constant for given a problem. Equation (

24) has get rid of coordinate

x, can be solved numerically. A full Maple code of solving Equation (

24) is provided in Appendix B.

For its corresponding steady problem, the function

f is only a function of

, the Equation (

24) can be simplified into:

and boundary conditions:

and

. Equation (

25) not only facilitates solving the equation but also allows us to express the obtained results as a single profile in terms of the similar variable

. A full Maple code of solving Equation (

25) is provided in Appendix C.

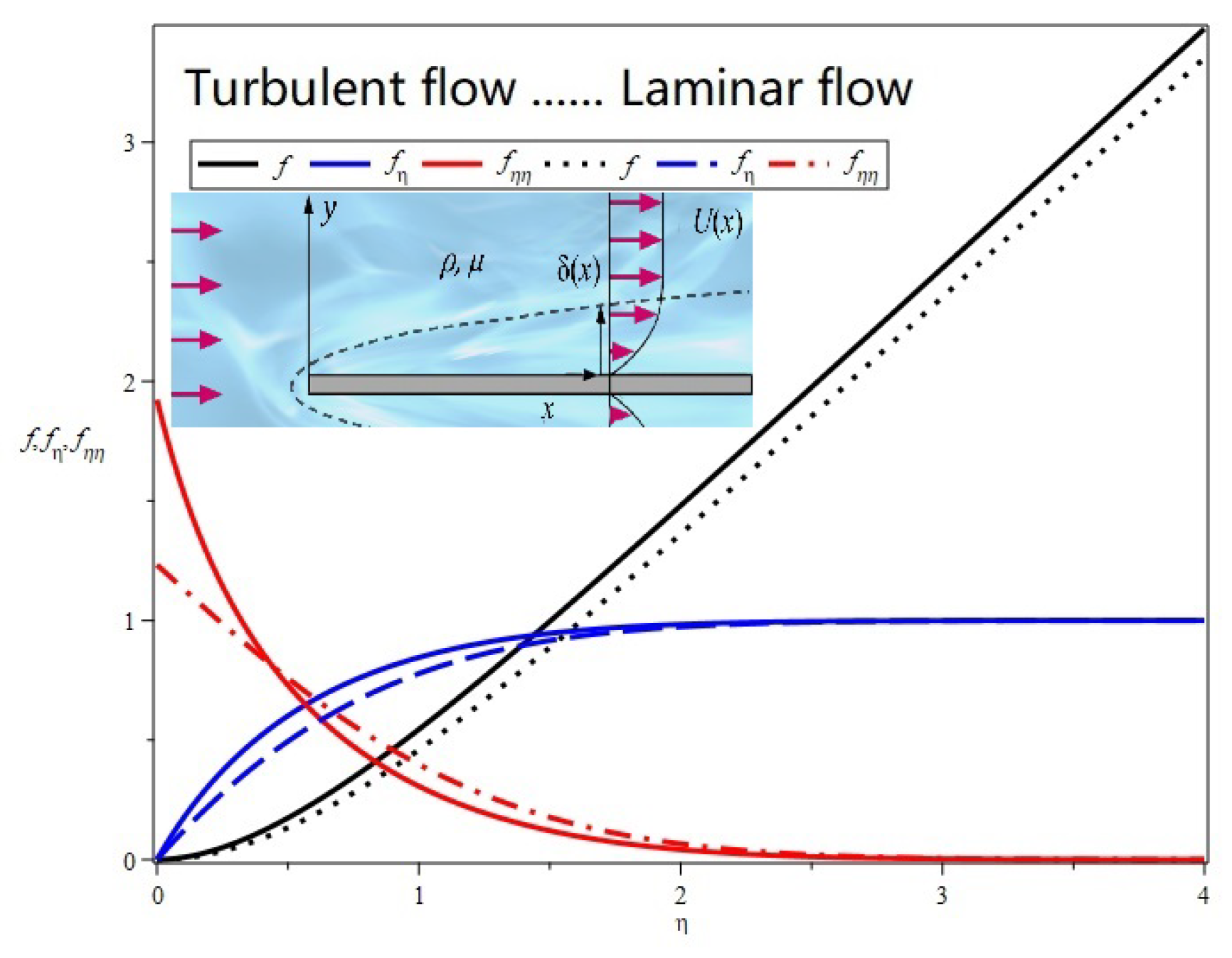

Although we do not yet have specific data for

, we can still assume

for the laminar boundary layer and

for the turbulent boundary layer. Using the program provided above, it is easy to calculate the corresponding

for both laminar and turbulent flow. The specific results are shown in

Figure 1. From the profile of

, it can be seen that the velocity profile in turbulent flow is blunter than that in laminar flow; from the profile of

, it can be observed that the friction in turbulent flow is much greater than that in laminar flow.

To demonstrate the difference in frictional resistance between turbulent and laminar flow, let’s calculate the shear stress

. Considering the order of magnitude approximation estimates of the Prandtl boundary layer theory in

Table 1, the shear stress can be approximated as:

. Therefore, the local wall shear stress

is given by

:

This expression reveals that the resistance of turbulent flow is much greater than that of laminar flow.

Table 2 lists the different

corresponding to different

; the larger the

, the greater the

.

Appendix A

with(student); with(PDEtools); layer:= diff(u(x, y, t), x) + diff(v(x, y, t), y) = 0, diff(u(x, y, t), t) + u(x, y, t)*diff(u(x, y, t), x) + v(x, y, t)*diff(u(x, y, t), y) = nu*diff(u(x, y, t), y, y) + kappa*diff(diff(u(x, y, t), y)*diff(u(x, y, t), y), x); pdsolve(layer); SimilaritySolutions(layer).

Appendix B

restart; with(student); with(plots);with(PDEtools);alpha := 1;beta := 1;Gamma := 2*(alpha - beta);B:= 0.95; sun := diff(f(eta, tau), eta, eta, eta) + alpha*f(eta, tau)*diff(f(eta, tau), eta, eta) + beta*(1 - diff(f(eta, tau), eta)*diff(f(eta, tau), eta)) + B*diff(f(eta, tau), eta, eta)*diff(f(eta, tau), eta, eta) = diff(f(eta, tau), tau, eta); ibc := f(0, tau) = 0, f(eta, 0) = 0, D[1](f)(0, tau) = 0, D[1](f)(8, tau) = 1; sol := pdsolve(sun, ibc, numeric, spacestep = 0.025); F := subs(sol:-value(output = listprocedure), f(eta, tau)); FF := (eta, tau) -> F(eta, tau); FFX := (a, b) -> fdiff(FF(eta, tau), [eta], eta = a, tau = b); FFtau := (a, b) -> fdiff(FF(eta, tau), [tau], eta = a, tau = b); FFXX := (a, b) -> fdiff(FF(eta, tau), [eta, eta], eta = a, tau = b); FFXXX := (a, b) -> fdiff(FF(eta, tau), [eta, eta, eta], eta = a, tau = b); FFXtau := (a, b) -> fdiff(FF(eta, tau), [eta, tau], eta = a, tau = b); Fx := proc(eta, tau) if not type([eta, tau], list(numeric)) then return ’procname(args)’; end if; fdiff(F, [1], [eta, tau]); end proc; Ftau := proc(eta, tau) if not type([eta, tau], list(numeric)) then return ’procname(args)’; end if; fdiff(F, [2], [eta, tau]); end proc; Fxx := proc(eta, tau) if not type([eta, tau], list(numeric)) then return ’procname(args))’; end if; fdiff(F, [1, 1], [eta, tau]); end proc; Fxtau := proc(eta, tau) if not type([eta, tau], list(numeric)) then return ’procname(args)’; end if; fdiff(F, [1, 2], [eta, tau]); end proc; Fxxx := proc(eta, tau) if not type([eta, tau], list(numeric)) then return ’procname(args)’; end if; fdiff(F, [1, 1, 1], [eta, tau]); end proc; plots:-animate(plot, [F(eta, tau), eta = 0 .. 8], tau = 0 .. 10, color = red, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); plots:-animate(plot, [Fx(eta, tau), eta = 0 .. 8], tau = 0 .. 40, color = red, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); plots:-animate(plot, [Fxx(eta, tau), eta = 0 .. 8], tau = 0 .. 20, color = red, thickness = 3, axes = boxed);

Appendix C

restart: with(student); with(plots); alpha := 1; beta := 1; Gamma := 2*(alpha - beta); B := 0.95; turb := diff(f(eta), eta, eta, eta) + alpha*f(eta)*diff(f(eta), eta, eta) + beta*(1 - diff(f(eta), eta)*diff(f(eta), eta)) + B*diff(f(eta), eta, eta)*diff(f(eta), eta, eta) = 0; solution := dsolve(turb, f(0) = 0, D(f)(0) = 0, D(f)(4) = 1, numeric); ft := odeplot(solution, [eta, f(eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = black, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); ftprime := odeplot(solution, [eta, diff(f(eta), eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = blue, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); ftpprime := odeplot(solution, [eta, diff(f(eta), eta, eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = red, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); A := 0; laminar := diff(f(eta), eta, eta, eta) + alpha*f(eta)*diff(f(eta), eta, eta) + beta*(1 - diff(f(eta), eta)*diff(f(eta), eta)) + A*diff(f(eta), eta, eta)*diff(f(eta), eta, eta) = 0; sol := dsolve(laminar, f(0) = 0, D(f)(0) = 0, D(f)(4) = 1, numeric); fl := odeplot(sol, [eta, f(eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = black, thickness = 3, linestyle = dot, axes = boxed); flprime := odeplot(sol, [eta, diff(f(eta), eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = blue, linestyle = dash, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); flpprime := odeplot(sol, [eta, diff(f(eta), eta, eta)], eta = 0 .. 4, color = red, linestyle = dashdot, thickness = 3, axes = boxed); display(ft, ftprime, ftpprime, fl, flprime, flpprime, legend = [f, f[eta], f[eta*eta], f, f[eta], f[eta*eta]], linestyle = [solid, solid, solid, dot, dash, dashdot]);