Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

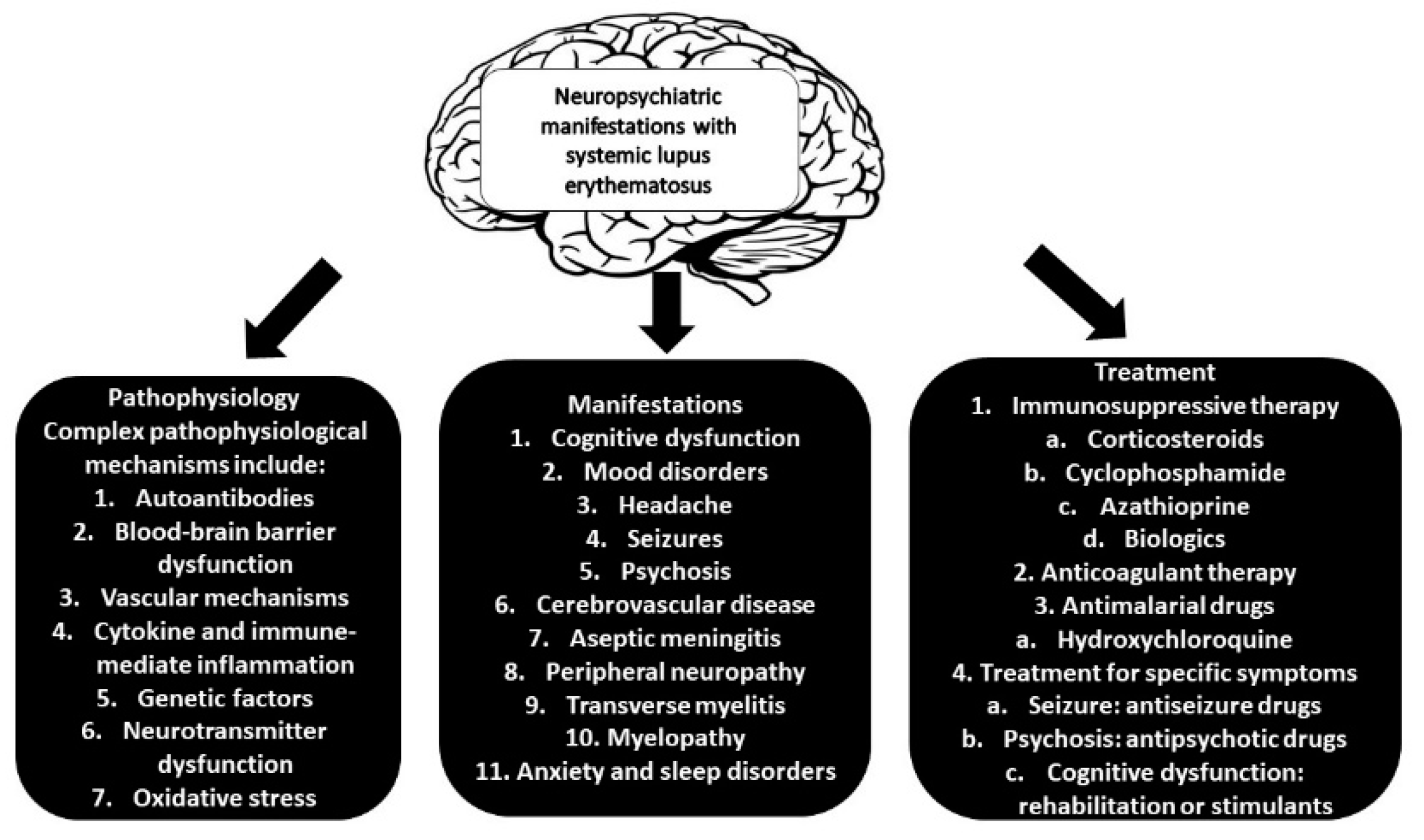

2. Neurological Involvement In SLE: Proposed Mechanisms

2.1. Autoantibodies in NPSLE

2.1.1. Antiphospholipid Antibodies Include β2-Glycoprotein 1, Cardiolipin Anticardiolipin (Anti-CL), and Lupus Anticoagulant (LA)

2.1.2. Anti-Ribosomal P protein Antibodies (anti-RP Ab)

2.1.3. Antibodies Against the N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor (anti-NMDA)

2.1.4. Antibodies Against Aquaporin 4 (NMO-IgG/AQP4-Ab)

2.1.5. Structural Endothelial Proteins

2.1.6. Anti-Endothelial Cell Antibodies (AECAb)

2.1.7. Anti-Ubiquitin Carboxyl Hydrolase L1 Antibodies (Anti-UCH-L1 Ab)

2.1.8. Antibodies Against Glyceraldehyde 3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase (GAPDH)

2.1.9. Triosephosphate Isomerase (Anti-TPI Antibody)

2.1.10. Microtubule-Associated Protein (Anti-MAP-2 Ab)

2.1.11. U1 Ribonucleoprotein (Anti-U1RNP Ab)

2.1.12. Others

2.2. The Cerebrovascular Pathway

2.3. Genetic And Environmental Factors

3. Spectrum of Neurological Manifestations in SLE

3.1. Psychiatric Disorders (Anxiety, Depression, and Psychosis)

3.2. Cognitive Dysfunction

3.3. Seizures

3.4. Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attacks (TIAs)

3.5. Peripheral Neuropathy

3.6. Demyelinating Syndromes

4. Diagnostic Challenges in Neurological SLE

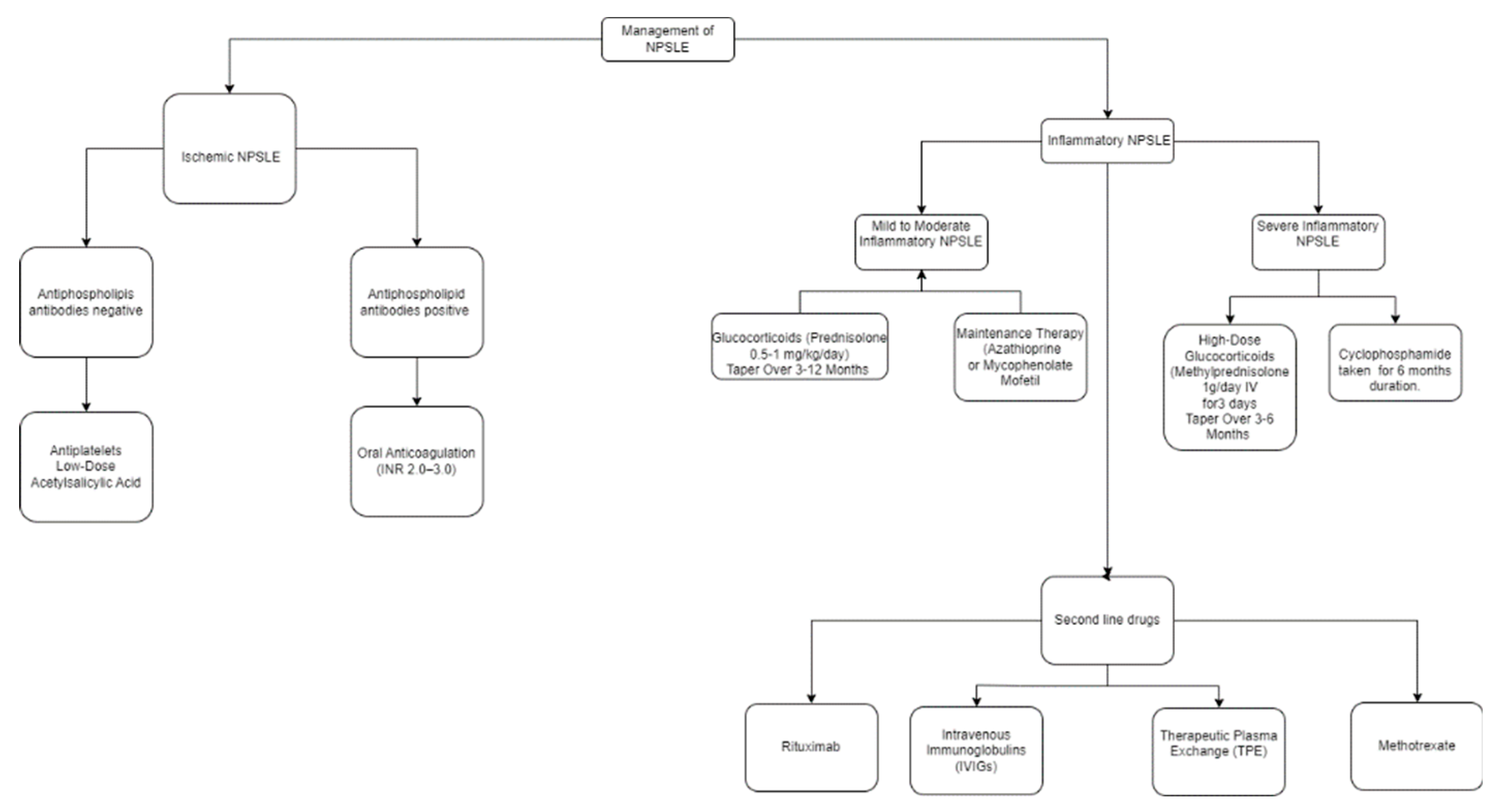

5. Management and Treatment Strategies for Neurological SLE

6. Prognosis And Long-Term Outcomes In NPSLE

7. Neurological SLE Research's Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karrar, S.; Cunninghame Graham, D.S. Abnormal B Cell Development in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: What the Genetics Tell Us. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 496–507.

- Didier, K.; Bolko, L.; Giusti, D.; Toquet, S.; Robbins, A.; Antonicelli, F.; Servettaz, A. Autoantibodies Associated With Connective Tissue Diseases: What Meaning for Clinicians? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 541.

- Magro, R.; Borg, A.A. Characterisation of Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Malta: A Population Based Cohort Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 2385386.

- Anstey, N.M.; Bastian, I.; Dunckley, H.; Currie, B.J. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Australian Aborigines: High Prevalence, Morbidity and Mortality. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1993, 23, 646–651.

- Grennan, D.M.; Bossingham, D. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): Different Prevalences in Different Populations of Australian Aboriginals. Aust. N. Z. J. Med. 1995, 25, 182–183.

- Danchenko, N.; Satia, J.A.; Anthony, M.S. Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Comparison of Worldwide Disease Burden. Lupus 2006, 15, 308–318.

- McMurray, R.W.; May, W. Sex Hormones and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 2100–2110.

- Dave, M.; Rankin, J.; Pearce, M.; Foster, H.E. Global Prevalence Estimates of Three Chronic Musculoskeletal Conditions: Club Foot, Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis and Juvenile Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2020, 18, 49.

- Lewandowski, L.B.; Schanberg, L.E.; Thielman, N.; Phuti, A.; Kalla, A.A.; Okpechi, I.; Nourse, P.; Gajjar, P.; Faller, G.; Ambaram, P.; et al. Severe Disease Presentation and Poor Outcomes among Pediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients in South Africa. Lupus 2017, 26, 186–194.

- Aggarwal, A.; Phatak, S.; Srivastava, P.; Lawrence, A.; Agarwal, V.; Misra, R. Outcomes in Juvenile Onset Lupus: Single Center Cohort from a Developing Country. Lupus 2018, 27, 1867–1875.

- Rees, F.; Doherty, M.; Grainge, M.J.; Lanyon, P.; Zhang, W. The Worldwide Incidence and Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017, 56, 1945–1961.

- Stojan, G.; Petri, M. Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Update. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2018, 30, 144–150.

- Yen, E.Y.; Singh, R.R. Brief Report: Lupus-An Unrecognized Leading Cause of Death in Young Females: A Population-Based Study Using Nationwide Death Certificates, 2000-Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018, 70, 1251–1255.

- Lee, Y.H.; Choi, S.J.; Ji, J.D.; Song, G.G. Overall and Cause-Specific Mortality in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An Updated Meta-Analysis. Lupus 2016, 25, 727–734.

- Muscal, E.; Brey, R.L. Neurologic Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Children and Adults. Neurol. Clin. 2010, 28, 61–73.

- Sibbitt, W.L.J.; Brandt, J.R.; Johnson, C.R.; Maldonado, M.E.; Patel, S.R.; Ford, C.C.; Bankhurst, A.D.; Brooks, W.M. The Incidence and Prevalence of Neuropsychiatric Syndromes in Pediatric Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 1536–1542.

- Govoni, M.; Bortoluzzi, A.; Padovan, M.; Silvagni, E.; Borrelli, M.; Donelli, F.; Ceruti, S.; Trotta, F. The Diagnosis and Clinical Management of the Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of Lupus. J. Autoimmun. 2016, 74, 41–72.

- Unterman, A.; Nolte, J.E.S.; Boaz, M.; Abady, M.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Zandman-Goddard, G. Neuropsychiatric Syndromes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Meta-Analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 41, 1–11.

- The American College of Rheumatology Nomenclature and Case Definitions for Neuropsychiatric Lupus Syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42, 599–608.

- Brey, R.L.; Holliday, S.L.; Saklad, A.R.; Navarrete, M.G.; Hermosillo-Romo, D.; Stallworth, C.L.; Valdez, C.R.; Escalante, A.; del Rincón, I.; Gronseth, G.; et al. Neuropsychiatric Syndromes in Lupus: Prevalence Using Standardized Definitions. Neurology 2002, 58, 1214–1220.

- Zardi, E.M.; Giorgi, C.; Zardi, D.M. Diagnostic Approach to Neuropsychiatric Lupus Erythematosus: What Should We Do? Postgrad. Med. 2018, 130, 536–547.

- Meier, A.L.; Bodmer, N.S.; Wirth, C.; Bachmann, L.M.; Ribi, C.; Pröbstel, A.-K.; Waeber, D.; Jelcic, I.; Steiner, U.C. Neuro-Psychiatric Manifestations in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review and Results from the Swiss Lupus Cohort Study. Lupus 2021, 30, 1565–1576.

- Magro-Checa, C.; Zirkzee, E.J.; Huizinga, T.W.; Steup-Beekman, G.M. Management of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Current Approaches and Future Perspectives. Drugs 2016, 76, 459–483.

- Monahan, R.C.; Fronczek, R.; Eikenboom, J.; Middelkoop, H.A.M.; Beaart-van de Voorde, L.J.J.; Terwindt, G.M.; van der Wee, N.J.A.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; Kloppenburg, M.; et al. Mortality in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Neuropsychiatric Involvement: A Retrospective Analysis from a Tertiary Referral Center in the Netherlands. Lupus 2020, 29, 1892–1901.

- Hanly, J.G.; Li, Q.; Su, L.; Urowitz, M.B.; Gordon, C.; Bae, S.-C.; Romero-Diaz, J.; Sanchez-Guerrero, J.; Bernatsky, S.; Clarke, A.E.; et al. Cerebrovascular Events in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results From an International Inception Cohort Study. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2018, 70, 1478–1487.

- Abdel-Nasser, A.M.; Ghaleb, R.M.; Mahmoud, J.A.; Khairy, W.; Mahmoud, R.M. Association of Anti-Ribosomal P Protein Antibodies with Neuropsychiatric and Other Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2008, 27, 1377–1385.

- Florica, B.; Aghdassi, E.; Su, J.; Gladman, D.D.; Urowitz, M.B.; Fortin, P.R. Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 41, 203–211.

- Bonfa, E.; Golombek, S.J.; Kaufman, L.D.; Skelly, S.; Weissbach, H.; Brot, N.; Elkon, K.B. Association between Lupus Psychosis and Anti-Ribosomal P Protein Antibodies. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987, 317, 265–271.

- Sanna, G.; Bertolaccini, M.L.; Cuadrado, M.J.; Laing, H.; Khamashta, M.A.; Mathieu, A.; Hughes, G.R.V. Neuropsychiatric Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Prevalence and Association with Antiphospholipid Antibodies. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 985–992.

- Williams, R.C.J.; Sugiura, K.; Tan, E.M. Antibodies to Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 in Patients with Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2004, 50, 1239–1247.

- Conti, F.; Alessandri, C.; Bompane, D.; Bombardieri, M.; Spinelli, F.R.; Rusconi, A.C.; Valesini, G. Autoantibody Profile in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with Psychiatric Manifestations: A Role for Anti-Endothelial-Cell Antibodies. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004, 6, R366-372.

- Delunardo, F.; Soldati, D.; Bellisario, V.; Berry, A.; Camerini, S.; Crescenzi, M.; Alessandri, C.; Conti, F.; Ceccarelli, F.; Francia, A.; et al. Anti-GAPDH Autoantibodies as a Pathogenic Determinant and Potential Biomarker of Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016, 68, 2708–2716.

- Stock, A.D.; Gelb, S.; Pasternak, O.; Ben-Zvi, A.; Putterman, C. The Blood Brain Barrier and Neuropsychiatric Lupus: New Perspectives in Light of Advances in Understanding the Neuroimmune Interface. Autoimmun. Rev. 2017, 16, 612–619.

- Jacob, A.; Hack, B.; Chiang, E.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Quigg, R.J.; Alexander, J.J. C5a Alters Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Experimental Lupus. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 1682–1688.

- Jacob, A.; Hack, B.; Chen, P.; Quigg, R.J.; Alexander, J.J. C5a/CD88 Signaling Alters Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in Lupus through Nuclear Factor-κB. J. Neurochem. 2011, 119, 1041–1051.

- Kivity, S.; Agmon-Levin, N.; Zandman-Goddard, G.; Chapman, J.; Shoenfeld, Y. Neuropsychiatric Lupus: A Mosaic of Clinical Presentations. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 43.

- Yoshio, T.; Okamoto, H.; Kurasawa, K.; Dei, Y.; Hirohata, S.; Minota, S. IL-6, IL-8, IP-10, MCP-1 and G-CSF Are Significantly Increased in Cerebrospinal Fluid but Not in Sera of Patients with Central Neuropsychiatric Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2016, 25, 997–1003.

- Duan, L.; Yao, Y.; Kong, H.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, D. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: Potential Therapeutic Targets in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cytokine 2024, 184, 156770.

- Santer, D.M.; Yoshio, T.; Minota, S.; Möller, T.; Elkon, K.B. Potent Induction of IFN-Alpha and Chemokines by Autoantibodies in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Neuropsychiatric Lupus. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 1192–1201.

- Bialas, A.R.; Presumey, J.; Das, A.; van der Poel, C.E.; Lapchak, P.H.; Mesin, L.; Victora, G.; Tsokos, G.C.; Mawrin, C.; Herbst, R.; et al. Retraction Note: Microglia-Dependent Synapse Loss in Type I Interferon-Mediated Lupus. Nature 2020, 578, 177.

- Hirohata, S.; Kikuchi, H. Role of Serum IL-6 in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021, 3, 42–49.

- Qiao, X.; Wang, H.; Lu, L.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Q.; Guo, M.; Hou, Y.; Dou, H. Hippocampal Microglia CD40 Mediates NPSLE Cognitive Dysfunction in Mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 357, 577620.

- Sciascia, S.; Bertolaccini, M.L.; Roccatello, D.; Khamashta, M.A.; Sanna, G. Autoantibodies Involved in Neuropsychiatric Manifestations Associated with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 1706–1714.

- Salmon, J.E.; de Groot, P.G. Pathogenic Role of Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Lupus 2008, 17, 405–411.

- Harper, B.E.; Wills, R.; Pierangeli, S.S. Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Rheumtol. 2011, 6, 157–171.

- Katzav, A.; Ben-Ziv, T.; Blank, M.; Pick, C.G.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Chapman, J. Antibody-Specific Behavioral Effects: Intracerebroventricular Injection of Antiphospholipid Antibodies Induces Hyperactive Behavior While Anti-Ribosomal-P Antibodies Induces Depression and Smell Deficits in Mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 2014, 272, 10–15.

- de Carvalho, J.F.; Pasoto, S.G.; Appenzeller, S. Seizures in Primary Antiphospholipid Syndrome: The Relevance of Smoking to Stroke. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 2012, 981519.

- Shi, Z.-R.; Han, Y.-F.; Yin, J.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Jiang, Z.-X.; Zheng, L.; Tan, G.-Z.; Wang, L. The Diagnostic Benefit of Antibodies against Ribosomal Proteins in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Adv. Rheumatol. 2020, 60, 45.

- Caponi, L.; Bombardieri, S.; Migliorini, P. Anti-Ribosomal Antibodies Bind the Sm Proteins D and B/B’. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 112, 139–143.

- Alajangi, H.K.; Kaur, M.; Sharma, A.; Rana, S.; Thakur, S.; Chatterjee, M.; Singla, N.; Jaiswal, P.K.; Singh, G.; Barnwal, R.P. Blood-Brain Barrier: Emerging Trends on Transport Models and New-Age Strategies for Therapeutics Intervention against Neurological Disorders. Mol. Brain. 2022, 15, 49.

- Li, F.; Tsien, J.Z. Memory and the NMDA Receptors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 302–303.

- Levite, M. Glutamate Receptor Antibodies in Neurological Diseases: Anti-AMPA-GluR3 Antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR1 Antibodies, Anti-NMDA-NR2A/B Antibodies, Anti-mGluR1 Antibodies or Anti-mGluR5 Antibodies Are Present in Subpopulations of Patients with Either: Epilepsy, Encephalitis, Cerebellar Ataxia, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Neuropsychiatric SLE, Sjogren’s Syndrome, Schizophrenia, Mania or Stroke. These Autoimmune Anti-Glutamate Receptor Antibodies Can Bind Neurons in Few Brain Regions, Activate Glutamate Receptors, Decrease Glutamate Receptor’s Expression, Impair Glutamate-Induced Signaling and Function, Activate Blood Brain Barrier Endothelial Cells, Kill Neurons, Damage the Brain, Induce Behavioral/Psychiatric/Cognitive Abnormalities and Ataxia in Animal Models, and Can Be Removed or Silenced in Some Patients by Immunotherapy. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2014, 121, 1029–1075.

- Schüler, T.; Mesic, I.; Madry, C.; Bartholomäus, I.; Laube, B. Formation of NR1/NR2 and NR1/NR3 Heterodimers Constitutes the Initial Step in N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 37–46.

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Long, T.; Li, Z. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Associated with Recurrent Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis during Pregnancy. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2021, 24, 525–528.

- Saikali, P.; Cayrol, R.; Vincent, T. Anti-Aquaporin-4 Auto-Antibodies Orchestrate the Pathogenesis in Neuromyelitis Optica. Autoimmun. Rev. 2009, 9, 132–135.

- Rocca, M.A.; Cacciaguerra, L.; Filippi, M. Moving beyond Anti-Aquaporin-4 Antibodies: Emerging Biomarkers in the Spectrum of Neuromyelitis Optica. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2020, 20, 601–618.

- Asgari, N.; Jarius, S.; Laustrup, H.; Skejoe, H.P.; Lillevang, S.T.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Voss, A. Aquaporin-4-Autoimmunity in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Predominantly Population-Based Study. Mult. Scler. 2018, 24, 331–339.

- Risau, W.; Flamme, I. Vasculogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1995, 11, 73–91.

- Bergkamp, S.C.; Wahadat, M.J.; Salah, A.; Kuijpers, T.W.; Smith, V.; Tas, S.W.; van den Berg, J.M.; Kamphuis, S.; Schonenberg-Meinema, D. Dysregulated Endothelial Cell Markers in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 2023, 20, 18.

- Moschetti, L.; Piantoni, S.; Vizzardi, E.; Sciatti, E.; Riccardi, M.; Franceschini, F.; Cavazzana, I. Endothelial Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Systemic Sclerosis: A Common Trigger for Different Microvascular Diseases. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 849086.

- Ichinose, K.; Ohyama, K.; Furukawa, K.; Higuchi, O.; Mukaino, A.; Satoh, K.; Nakane, S.; Shimizu, T.; Umeda, M.; Fukui, S.; et al. Novel Anti-Suprabasin Antibodies May Contribute to the Pathogenesis of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 193, 123–130.

- Li, X.; Xiang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Feng, L.; Li, C.; Li, Z. Prevalence, Outcome and Prognostic Factors of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Real World Single Center Study. Mod. Rheumatol. 2020, 30, 321–326.

- Liu, Y.; Tu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Du, K.; Xie, Z.; Lin, Z. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Review. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 998328.

- Stock, A.D.; Wen, J.; Putterman, C. Neuropsychiatric Lupus, the Blood Brain Barrier, and the TWEAK/Fn14 Pathway. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 484.

- Li, X.; Sun, J.; Mu, R.; Gan, Y.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Yi, L.; Wang, Q.; Sun, X.; Li, Z. The Clinical Significance of Ubiquitin Carboxyl Hydrolase L1 and Its Autoantibody in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37, 474–480.

- Muslimov, I.A.; Iacoangeli, A.; Eom, T.; Ruiz, A.; Lee, M.; Stephenson, S.; Ginzler, E.M.; Tiedge, H. Neuronal BC RNA Transport Impairments Caused by Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Autoantibodies. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 7759–7777.

- Lindblom, J.; Mohan, C.; Parodis, I. Biomarkers in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Literature Review of the Last Decade. Brain Sci. 2022, 12.

- Myers, T.D.; Palladino, M.J. Newly Discovered Roles of Triosephosphate Isomerase Including Functions within the Nucleus. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 18.

- Sato, S.; Yashiro, M.; Asano, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Watanabe, H.; Migita, K. Association of Anti-Triosephosphate Isomerase Antibodies with Aseptic Meningitis in Patients with Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 36, 1655–1659.

- Sánchez, C.; Díaz-Nido, J.; Avila, J. Phosphorylation of Microtubule-Associated Protein 2 (MAP2) and Its Relevance for the Regulation of the Neuronal Cytoskeleton Function. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000, 61, 133–168.

- Kang, H.J.; Voleti, B.; Hajszan, T.; Rajkowska, G.; Stockmeier, C.A.; Licznerski, P.; Lepack, A.; Majik, M.S.; Jeong, L.S.; Banasr, M.; et al. Decreased Expression of Synapse-Related Genes and Loss of Synapses in Major Depressive Disorder. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 1413–1417.

- Vlachoyiannopoulos, P.G.; Guialis, A.; Tzioufas, G.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. Predominance of IgM Anti-U1RNP Antibodies in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Br. J. Rheumatol. 1996, 35, 534–541.

- Dema, B.; Charles, N. Autoantibodies in SLE: Specificities, Isotypes and Receptors. Antibodies (Basel) 2016, 5, 2.

- Ota, Y.; Srinivasan, A.; Capizzano, A.A.; Bapuraj, J.R.; Kim, J.; Kurokawa, R.; Baba, A.; Moritani, T. Central Nervous System Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Pathophysiologic, Clinical, and Imaging Features. Radiographics 2022, 42, 212–232.

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, B.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L. Roles of Circular RNAs in Immune Regulation and Autoimmune Diseases. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 503.

- Bertsias, G.K.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Aringer, M.; Bollen, E.; Bombardieri, S.; Bruce, I.N.; Cervera, R.; Dalakas, M.; Doria, A.; Hanly, J.G.; et al. EULAR Recommendations for the Management of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with Neuropsychiatric Manifestations: Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for Clinical Affairs. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 2074–2082.

- Murray, S.G.; Yazdany, J.; Kaiser, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Trupin, L.; Yelin, E.H.; Katz, P.P.; Julian, L.J. Cardiovascular Disease and Cognitive Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2012, 64, 1328–1333.

- Cervera, R.; Khamashta, M.A.; Font, J.; Sebastiani, G.D.; Gil, A.; Lavilla, P.; Mejía, J.C.; Aydintug, A.O.; Chwalinska-Sadowska, H.; de Ramón, E.; et al. Morbidity and Mortality in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus during a 10-Year Period: A Comparison of Early and Late Manifestations in a Cohort of 1,000 Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003, 82, 299–308.

- Saadatnia, M.; Sayed-Bonakdar, Z.; Mohammad-Sharifi, G.; Sarrami, A.H. The Necessity of Stroke Prevention in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2012, 17, 894–895.

- Zandman-Goddard, G.; Chapman, J.; Shoenfeld, Y. Autoantibodies Involved in Neuropsychiatric SLE and Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 36, 297–315.

- Barbhaiya, M.; Zuily, S.; Naden, R.; Hendry, A.; Manneville, F.; Amigo, M.-C.; Amoura, Z.; Andrade, D.; Andreoli, L.; Artim-Esen, B.; et al. The 2023 ACR/EULAR Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 1687–1702.

- Giannakopoulos, B.; Krilis, S.A. The Pathogenesis of the Antiphospholipid Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1033–1044.

- Hanly, J.G.; Walsh, N.M.; Sangalang, V. Brain Pathology in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 1992, 19, 732–741.

- Ellis, S.G.; Verity, M.A. Central Nervous System Involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Review of Neuropathologic Findings in 57 Cases, 1955--1977. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1979, 8, 212–221.

- Cohen, D.; Rijnink, E.C.; Nabuurs, R.J.A.; Steup-Beekman, G.M.; Versluis, M.J.; Emmer, B.J.; Zandbergen, M.; van Buchem, M.A.; Allaart, C.F.; Wolterbeek, R.; et al. Brain Histopathology in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Identification of Lesions Associated with Clinical Neuropsychiatric Lupus Syndromes and the Role of Complement. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017, 56, 77–86.

- Bruce, I.N.; Urowitz, M.B.; Gladman, D.D.; Ibañez, D.; Steiner, G. Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease in Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The Toronto Risk Factor Study. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 3159–3167.

- Holmqvist, M.; Simard, J.F.; Asplund, K.; Arkema, E.V. Stroke in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Cohort Studies. RMD Open 2015, 1, e000168.

- Ward, M.M. Premature Morbidity from Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Diseases in Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42, 338–346.

- Mikdashi, J.; Handwerger, B.; Langenberg, P.; Miller, M.; Kittner, S. Baseline Disease Activity, Hyperlipidemia, and Hypertension Are Predictive Factors for Ischemic Stroke and Stroke Severity in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Stroke 2007, 38, 281–285.

- Urowitz, M.B.; Gladman, D.; Ibañez, D.; Bae, S.C.; Sanchez-Guerrero, J.; Gordon, C.; Clarke, A.; Bernatsky, S.; Fortin, P.R.; Hanly, J.G.; et al. Atherosclerotic Vascular Events in a Multinational Inception Cohort of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2010, 62, 881–887.

- Levine, S.R.; Brey, R.L.; Tilley, B.C.; Thompson, J.L.P.; Sacco, R.L.; Sciacca, R.R.; Murphy, A.; Lu, Y.; Costigan, T.M.; Rhine, C.; et al. Antiphospholipid Antibodies and Subsequent Thrombo-Occlusive Events in Patients with Ischemic Stroke. JAMA 2004, 291, 576–584.

- Fernández-Nebro, A.; Rúa-Figueroa, Í.; López-Longo, F.J.; Galindo-Izquierdo, M.; Calvo-Alén, J.; Olivé-Marqués, A.; Ordóñez-Cañizares, C.; Martín-Martínez, M.A.; Blanco, R.; Melero-González, R.; et al. Cardiovascular Events in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Nationwide Study in Spain From the RELESSER Registry. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e1183.

- Saadatnia, M.; Sayed-Bonakdar, Z.; Mohammad-Sharifi, G.; Sarrami, A.H. Prevalence and Prognosis of Cerebrovascular Accidents and Its Subtypes Among Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Isfahan, Iran: A Hospital Clinic-Based Study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 123–126.

- Ho, R.C.; Ong, H.; Thiaghu, C.; Lu, Y.; Ho, C.S.; Zhang, M.W. Genetic Variants That Are Associated with Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2016, 43, 541–551.

- de Vries, B.; Steup-Beekman, G.M.; Haan, J.; Bollen, E.L.; Luyendijk, J.; Frants, R.R.; Terwindt, G.M.; van Buchem, M.A.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; van den Maagdenberg, A.M.J.M.; et al. TREX1 Gene Variant in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 1886–1887.

- Namjou, B.; Kothari, P.H.; Kelly, J.A.; Glenn, S.B.; Ojwang, J.O.; Adler, A.; Alarcón-Riquelme, M.E.; Gallant, C.J.; Boackle, S.A.; Criswell, L.A.; et al. Evaluation of the TREX1 Gene in a Large Multi-Ancestral Lupus Cohort. Genes Immun. 2011, 12, 270–279.

- Karageorgas, T.P.; Tseronis, D.D.; Mavragani, C.P. Activation of Type I Interferon Pathway in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Association with Distinct Clinical Phenotypes. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 273907.

- Lundström, E.; Gustafsson, J.T.; Jönsen, A.; Leonard, D.; Zickert, A.; Elvin, K.; Sturfelt, G.; Nordmark, G.; Bengtsson, A.A.; Sundin, U.; et al. HLA-DRB1*04/*13 Alleles Are Associated with Vascular Disease and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72, 1018–1025.

- Rullo, O.J.; Tsao, B.P. Recent Insights into the Genetic Basis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 72 Suppl 2, ii56-61.

- Koga, M.; Kawasaki, A.; Ito, I.; Furuya, T.; Ohashi, J.; Kyogoku, C.; Ito, S.; Hayashi, T.; Matsumoto, I.; Kusaoi, M.; et al. Cumulative Association of Eight Susceptibility Genes with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Japanese Female Population. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 56, 503–507.

- Vista, E.S.; Farris, A.D.; James, J.A. Chapter 24 - Roles for Infections in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Pathogenesis. In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Fifth Edition); Lahita, R.G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2011; pp. 425–435 ISBN 978-0-12-374994-9.

- Iliopoulos, A.G.; Tsokos, G.C. Immunopathogenesis and Spectrum of Infections in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1996, 25, 318–336.

- Telles, R.W.; Lanna, C.C.D.; Souza, F.L.; Rodrigues, L.A.; Reis, R.C.P.; Ribeiro, A.L. Causes and Predictors of Death in Brazilian Lupus Patients. Rheumatol. Int. 2013, 33, 467–473.

- Warnatz, K.; Peter, H.H.; Schumacher, M.; Wiese, L.; Prasse, A.; Petschner, F.; Vaith, P.; Volk, B.; Weiner, S.M. Infectious CNS Disease as a Differential Diagnosis in Systemic Rheumatic Diseases: Three Case Reports and a Review of the Literature. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2003, 62, 50–57.

- Zhong, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Peng, F. Cryptococcal Meningitis in Chinese Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2015, 131, 59–63.

- Yang, C.-D.; Wang, X.-D.; Ye, S.; Gu, Y.-Y.; Bao, C.-D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.-L. Clinical Features, Prognostic and Risk Factors of Central Nervous System Infections in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26, 895–901.

- Lu, X.Y.; Zhu, C.Q.; Qian, J.; Chen, X.X.; Ye, S.; Gu, Y.Y. Intrathecal Cytokine and Chemokine Profiling in Neuropsychiatric Lupus or Lupus Complicated with Central Nervous System Infection. Lupus 2010, 19, 689–695.

- Zandman-Goddard, G.; Berkun, Y.; Barzilai, O.; Boaz, M.; Ram, M.; Anaya, J.M.; Shoenfeld, Y. Neuropsychiatric Lupus and Infectious Triggers. Lupus 2008, 17, 380–384.

- Nived, O.; Johansson, I.; Sturfelt, G. Effects of Ultraviolet Irradiation on Natural Killer Cell Function in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1992, 51, 726–730.

- Abe, M.; Ishikawa, O.; Miyachi, Y.; Kanai, Y. In Vitro Spontaneous and UVB-Induced Lymphocyte Apoptosis Are Not Specific to SLE. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 1997, 13, 204–207.

- Cohen, M.R.; Isenberg, D.A. Ultraviolet Irradiation in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Friend or Foe? Br. J. Rheumatol. 1996, 35, 1002–1007.

- Kuhn, A.; Fehsel, K.; Lehmann, P.; Krutmann, J.; Ruzicka, T.; Kolb-Bachofen, V. Aberrant Timing in Epidermal Expression of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase after UV Irradiation in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1998, 111, 149–153.

- Norris, D.A. Pathomechanisms of Photosensitive Lupus Erythematosus. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1993, 100, 58S-68S.

- Molina, J.F.; McGrath, H.J. Longterm Ultraviolet-A1 Irradiation Therapy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 1997, 24, 1072–1074.

- Schmidt, E.; Tony, H.-P.; Bröcker, E.-B.; Kneitz, C. Sun-Induced Life-Threatening Lupus Nephritis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1108, 35–40.

- Geara, A.S.; Torbey, E.; El-imad, B. Lupus Cerebritis after Visiting a Tanning Salon. Bull. NYU Hosp. Jt. Dis. 2009, 67, 391–393.

- Yung, R.L.; Richardson, B.C. Chapter 22 - Drug-Induced Lupus Mechanisms. In Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (Fifth Edition); Lahita, R.G., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, 2011; pp. 385–403 ISBN 978-0-12-374994-9.

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Atzeni, F.; Capsoni, F.; Lubrano, E.; Doria, A. Drug-Induced Lupus Erythematosus. Autoimmunity 2005, 38, 507–518.

- Aguirre Zamorano, M.A.; Lopez Pedrera, R.; Cuadrado Lozano, M.J. Drug-Induced Lupus. Medicina Clinica 2010, 135, 124–129.

- Pretel, M.; Marquès, L.; España, A. Lupus Eritematoso Inducido Por Fármacos. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas 2014, 105, 18–30.

- Bracke, A.; Nijsten, T.; Vandermaesen, J.; Meuleman, L.; Lambert, J. Lansoprazole-Induced Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus: Two Cases. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2005, 85, 353–354.

- McKay, D.A.; Schofield, O.M.V.; Benton, E.C. Terbinafine-Induced Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2004, 84, 472–474.

- Suess, A.; Sticherling, M. Leflunomide in Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus - Two Sides of a Coin. Int. J. Dermatol. 2008, 47, 83–86.

- Costa, M.F.; Said, N.R.; Zimmermann, B. Drug-Induced Lupus Due to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha Agents. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 37, 381–387.

- Guhl, G.; Diaz-Ley, B.; García-García, C.; Fraga, J.; Garcia-Diez, A. Chemotherapy-Induced Subacute Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2009, 18, 859–860.

- Grönhagen, C.M.; Fored, C.M.; Linder, M.; Granath, F.; Nyberg, F. Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus and Its Association with Drugs: A Population-Based Matched Case-Control Study of 234 Patients in Sweden. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 296–305.

- Merlin, F.; Prochilo, T.; Kildani, B.; Lombardi, C.; Pasolini, G.; Bonetti, F.; Beretta, G.D. Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE)-like Lesions Induced by Capecitabine. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2008, 23, 715–716.

- Pamuk, O.N.; Raza, A.A.; Hasni, S. Neuropsychiatric Lupus in Late- and Early-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 8–15.

- Liao, J.; Kang, J.; Li, F.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Tang, Q.; Mao, N.; Li, S.; Xie, X. A Cross-Sectional Study on the Association of Anxiety and Depression with the Disease Activity of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 591.

- Mehat, P.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Esdaile, J.M.; AviÑa-Zubieta, A.; De Vera, M.A. Medication Nonadherence in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2017, 69, 1706–1713.

- Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Pouchot, J.; Guettrot-Imbert, G.; Le Guern, V.; Leroux, G.; Marra, D.; Morel, N.; Piette, J.-C. Adherence to Treatment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 329–340.

- Abrol, E.; Coutinho, E.; Chou, M.; Hart, M.; Vincent, A.; Howard, R.; Zandi, M.S.; Isenberg, D. Psychosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE): 40-Year Experience of a Specialist Centre. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60, 5620–5629.

- Chau, S.Y.; Mok, C.C. Factors Predictive of Corticosteroid Psychosis in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Neurology 2003, 61, 104–107.

- Tokunaga, M.; Saito, K.; Kawabata, D.; Imura, Y.; Fujii, T.; Nakayamada, S.; Tsujimura, S.; Nawata, M.; Iwata, S.; Azuma, T.; et al. Efficacy of Rituximab (Anti-CD20) for Refractory Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Involving the Central Nervous System. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007, 66, 470–475.

- Raghunath, S.; Glikmann-Johnston, Y.; Golder, V.; Kandane-Rathnayake, R.; Morand, E.F.; Stout, J.C.; Hoi, A. Clinical Associations of Cognitive Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus Sci. Med. 2023, 10, e000835.

- Harrison, M.J.; Morris, K.A.; Horton, R.; Toglia, J.; Barsky, J.; Chait, S.; Ravdin, L.; Robbins, L. Results of Intervention for Lupus Patients with Self-Perceived Cognitive Difficulties. Neurology 2005, 65, 1325–1327.

- Petri, M.; Naqibuddin, M.; Sampedro, M.; Omdal, R.; Carson, K.A. Memantine in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2011, 41, 194–202.

- Hanly, J.G.; Urowitz, M.B.; Su, L.; Gordon, C.; Bae, S.-C.; Sanchez-Guerrero, J.; Romero-Diaz, J.; Wallace, D.J.; Clarke, A.E.; Ginzler, E.; et al. Seizure Disorders in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Results from an International, Prospective, Inception Cohort Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2012, 71, 1502–1509.

- de Amorim, L.C.D.; Maia, F.M.; Rodrigues, C.E.M. Stroke in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Antiphospholipid Syndrome: Risk Factors, Clinical Manifestations, Neuroimaging, and Treatment. Lupus 2017, 26, 529–536.

- Su, L.; Qi, Z.; Guan, S.; Wei, L.; Zhao, Y. Exploring the Risk Factors for Ischemic Cerebrovascular Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Single-Center Case-Control Study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 978910.

- Harris, E.N.; Pierangeli, S. Antiphospholipid Antibodies and Cerebral Lupus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1997, 823, 270–278.

- Jasmin, R.; Sockalingam, S.; Ramanaidu, L.P.; Goh, K.J. Clinical and Electrophysiological Characteristics of Symmetric Polyneuropathy in a Cohort of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients. Lupus 2015, 24, 248–255.

- Mahran, S.A.; Galluccio, F.; Khedr, T.M.; Elsonbaty, A.; Allam, A.E.-S.; Garcia Martos, A.; Osman, D.M.M.; Matucci-Cerinic, M.; Guiducci, S.; Galal, M.A.A. Peripheral Neuropathy in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: What Can Neuromuscular Ultrasonography (NMUS) Tell Us? A Cross-Sectional Study. Lupus Sci. Med. 2021, 8, e000521.

- Xianbin, W.; Mingyu, W.; Dong, X.; Huiying, L.; Yan, X.; Fengchun, Z.; Xiaofeng, Z. Peripheral Neuropathies Due to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94, e625, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000000625.

- Bhoi, S.K.; Jha, M.; Jaiswal, B. Guillain-Barre Syndrome as the Initial Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Case Report with a Systematic and Literature Review. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2023, 79, S360–S364.

- Xiong, H.; Tang, F.; Guo, Y.; Xu, R.; Lei, P. Neural Circuit Changes in Neurological Disorders: Evidence from in Vivo Two-Photon Imaging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 87, 101933.

- Chessa, E.; Piga, M.; Floris, A.; Mathieu, A.; Cauli, A. Demyelinating Syndrome in SLE: Review of Different Disease Subtypes and Report of a Case Series. Reumatismo 2017, 69, 175–183.

- Miller, D.H.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Filippi, M.; Banwell, B.L.; Cohen, J.A.; Freedman, M.S.; Galetta, S.L.; Hutchinson, M.; Johnson, R.T.; Kappos, L.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Suspected Multiple Sclerosis: A Consensus Approach. Mult. Scler. 2008, 14, 1157–1174.

- Magro Checa, C.; Cohen, D.; Bollen, E.L.E.M.; van Buchem, M.A.; Huizinga, T.W.J.; Steup-Beekman, G.M. Demyelinating Disease in SLE: Is It Multiple Sclerosis or Lupus? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2013, 27, 405–424.

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Kitsos, D.; Papathanasiou, M.; Kapsala, N.; Garantziotis, P.; Pieta, A.; Gioti, O.; Grivas, A.; Voumvourakis, K.; Boumpas, D.; et al. Demyelinating Syndromes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Data From the “Attikon” Lupus Cohort. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 889613.

- Esdaile, J.M.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Grodzicky, T.; Li, Y.; Panaritis, C.; du Berger, R.; Côte, R.; Grover, S.A.; Fortin, P.R.; Clarke, A.E.; et al. Traditional Framingham Risk Factors Fail to Fully Account for Accelerated Atherosclerosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2001, 44, 2331–2337.

- Kozora, E.; West, S.G.; Kotzin, B.L.; Julian, L.; Porter, S.; Bigler, E. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities and Cognitive Deficits in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients without Overt Central Nervous System Disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 41, 41–47.

- Nomura, K.; Yamano, S.; Ikeda, Y.; Yamada, H.; Fujimoto, T.; Minami, S.; Fukui, R.; Takaoka, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Dohi, K. Asymptomatic Cerebrovascular Lesions Detected by Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Lacking a History of Neuropsychiatric Events. Intern. Med. 1999, 38, 785–795.

- Sibbitt, W.L.J.; Sibbitt, R.R.; Brooks, W.M. Neuroimaging in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 42, 2026–2038.

- Waterloo, K.; Omdal, R.; Sjöholm, H.; Koldingsnes, W.; Jacobsen, E.A.; Sundsfjord, J.A.; Husby, G.; Mellgren, S.I. Neuropsychological Dysfunction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Is Not Associated with Changes in Cerebral Blood Flow. J. Neurol. 2001, 248, 595–602.

- Zirkzee, E.J.M.; Magro Checa, C.; Sohrabian, A.; Steup-Beekman, G.M. Cluster Analysis of an Array of Autoantibodies in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. J. Rheumatol. 2014, 41, 1720–1721.

- Birnbaum, J.; Kerr, D. Devic’s Syndrome in a Woman with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications of Testing for the Neuromyelitis Optica IgG Autoantibody. Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 347–351.

- Birnbaum, J.; Petri, M.; Thompson, R.; Izbudak, I.; Kerr, D. Distinct Subtypes of Myelitis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 3378–3387.

- González-Duarte, A.; Cantú-Brito, C.G.; Ruano-Calderón, L.; García-Ramos, G. Clinical Description of Seizures in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Eur. Neurol. 2008, 59, 320–323.

- Appenzeller, S.; Cendes, F.; Costallat, L.T.L. Epileptic Seizures in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Neurology 2004, 63, 1808–1812.

- Hanly, J.G. Diagnosis and Management of Neuropsychiatric SLE. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014, 10, 338–347.

- Zirkzee, E.J.M.; Steup-Beekman, G.M.; van der Mast, R.C.; Bollen, E.L.E.M.; van der Wee, N.J.A.; Baptist, E.; Slee, T.M.; Huisman, M.V.; Middelkoop, H.A.M.; Luyendijk, J.; et al. Prospective Study of Clinical Phenotypes in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; Multidisciplinary Approach to Diagnosis and Therapy. J. Rheumatol. 2012, 39, 2118–2126.

- Stojanovich, L.; Stojanovich, R.; Kostich, V.; Dzjolich, E. Neuropsychiatric Lupus Favourable Response to Low Dose i.v. Cyclophosphamide and Prednisolone (Pilot Study). Lupus 2003, 12, 3–7.

- Neuwelt, C.M. The Role of Plasmapheresis in the Treatment of Severe Central Nervous System Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2003, 7, 173–182.

- Milstone, A.M.; Meyers, K.; Elia, J. Treatment of Acute Neuropsychiatric Lupus with Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Clin. Rheumatol. 2005, 24, 394–397.

- Vina, E.R.; Fang, A.J.; Wallace, D.J.; Weisman, M.H. Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Prognosis and Outcome. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 35, 175–184.

- Barile-Fabris, L.; Ariza-Andraca, R.; Olguín-Ortega, L.; Jara, L.J.; Fraga-Mouret, A.; Miranda-Limón, J.M.; Fuentes de la Mata, J.; Clark, P.; Vargas, F.; Alocer-Varela, J. Controlled Clinical Trial of IV Cyclophosphamide versus IV Methylprednisolone in Severe Neurological Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005, 64, 620–625.

- Muñoz-Rodriguez, F.J.; Font, J.; Cervera, R.; Reverter, J.C.; Tàssies, D.; Espinosa, G.; López-Soto, A.; Carmona, F.; Balasch, J.; Ordinas, A.; et al. Clinical Study and Follow-up of 100 Patients with the Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1999, 29, 182–190.

- Jung, H.; Bobba, R.; Su, J.; Shariati-Sarabi, Z.; Gladman, D.D.; Urowitz, M.; Lou, W.; Fortin, P.R. The Protective Effect of Antimalarial Drugs on Thrombovascular Events in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 62, 863–868.

- Hermosillo-Romo, D.; Brey, R.L. Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (NPSLE). Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2002, 16, 229–244.

- Fessler, B.J.; Alarcón, G.S.; McGwin, G.J.; Roseman, J.; Bastian, H.M.; Friedman, A.W.; Baethge, B.A.; Vilá, L.; Reveille, J.D. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in Three Ethnic Groups: XVI. Association of Hydroxychloroquine Use with Reduced Risk of Damage Accrual. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 1473–1480.

- Petri, M. Use of Hydroxychloroquine to Prevent Thrombosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2011, 13, 77–80.

- Schäcke, H.; Döcke, W.D.; Asadullah, K. Mechanisms Involved in the Side Effects of Glucocorticoids. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 96, 23–43.

- Buttgereit, F.; da Silva, J.A.P.; Boers, M.; Burmester, G.-R.; Cutolo, M.; Jacobs, J.; Kirwan, J.; Köhler, L.; Van Riel, P.; Vischer, T.; et al. Standardised Nomenclature for Glucocorticoid Dosages and Glucocorticoid Treatment Regimens: Current Questions and Tentative Answers in Rheumatology. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2002, 61, 718–722.

- Hejaili, F.F.; Moist, L.M.; Clark, W.F. Treatment of Lupus Nephritis. Drugs 2003, 63, 257–274.

- Houssiau, F.A.; Vasconcelos, C.; D’Cruz, D.; Sebastiani, G.D.; de Ramon Garrido, E.; Danieli, M.G.; Abramovicz, D.; Blockmans, D.; Cauli, A.; Direskeneli, H.; et al. The 10-Year Follow-up Data of the Euro-Lupus Nephritis Trial Comparing Low-Dose and High-Dose Intravenous Cyclophosphamide. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2010, 69, 61–64.

- Ognenovski, V.M.; Marder, W.; Somers, E.C.; Johnston, C.M.; Farrehi, J.G.; Selvaggi, S.M.; McCune, W.J. Increased Incidence of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia in Women with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Treated with Intravenous Cyclophosphamide. J. Rheumatol. 2004, 31, 1763–1767.

- DiPiero, J.; Teng, K.; Hicks, J.K. Should Thiopurine Methyltransferase (TPMT) Activity Be Determined before Prescribing Azathioprine, Mercaptopurine, or Thioguanine? Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2015, 82, 409–413.

- Oelzner, P.; Abendroth, K.; Hein, G.; Stein, G. Predictors of Flares and Long-Term Outcome of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus during Combined Treatment with Azathioprine and Low-Dose Prednisolone. Rheumatol. Int. 1996, 16, 133–139.

- Allison, A.C. Mechanisms of Action of Mycophenolate Mofetil. Lupus 2005, 14, s2-8.

- Pisoni, C.N.; Sanchez, F.J.; Karim, Y.; Cuadrado, M.J.; D’Cruz, D.P.; Abbs, I.C.; Khamasta, M.A.; Hughes, G.R.V. Mycophenolate Mofetil in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Efficacy and Tolerability in 86 Patients. J. Rheumatol. 2005, 32, 1047–1052.

- Zhou, H.Q.; Zhang, F.C.; Tian, X.P.; Leng, X.M.; Lu, J.J.; Zhao, Y.; Tang, F.L.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, X.F.; Zhang, Z.L.; et al. Clinical Features and Outcome of Neuropsychiatric Lupus in Chinese: Analysis of 240 Hospitalized Patients. Lupus 2008, 17, 93–99.

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lei, H.; Zhu, G.; Fu, B. Impact Analysis of Autoantibody Level and NR2 Antibody Level in Neuropsychiatric SLE Treated by Methylprednisolone Combined with MTX and DXM Intrathecal Injection. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 70, 1005–1009.

- Bambauer, R.; Schwarze, U.; Schiel, R. Cyclosporin A and Therapeutic Plasma Exchange in the Treatment of Severe Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Artif. Organs. 2000, 24, 852–856.

- Yang, M.; Li, M.; He, W.; Wang, B.; Gu, Y. Calcineurin Inhibitors May Be a Reasonable Alternative to Cyclophosphamide in the Induction Treatment of Active Lupus Nephritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2014, 7, 1663–1670.

- Glennie, M.J.; French, R.R.; Cragg, M.S.; Taylor, R.P. Mechanisms of Killing by Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibodies. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 44, 3823–3837.

- Camara, I.; Sciascia, S.; Simoes, J.; Pazzola, G.; Salas, V.; Karim, Y.; Roccatello, D.; Cuadrado, M.J. Treatment with Intravenous Immunoglobulins in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Series of 52 Patients from a Single Centre. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014, 32, 41–47.

- Baigent, C.; Blackwell, L.; Collins, R.; Emberson, J.; Godwin, J.; Peto, R.; Buring, J.; Hennekens, C.; Kearney, P.; Meade, T.; et al. Aspirin in the Primary and Secondary Prevention of Vascular Disease: Collaborative Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data from Randomised Trials. Lancet 2009, 373, 1849–1860.

- Tektonidou, M.G.; Laskari, K.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Moutsopoulos, H.M. Risk Factors for Thrombosis and Primary Thrombosis Prevention in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus with or without Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 61, 29–36.

- Adams, R.J.; Albers, G.; Alberts, M.J.; Benavente, O.; Furie, K.; Goldstein, L.B.; Gorelick, P.; Halperin, J.; Harbaugh, R.; Johnston, S.C.; et al. Update to the AHA/ASA Recommendations for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack. Stroke 2008, 39, 1647–1652.

- Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Cuadrado, M.J.; Ruiz-Arruza, I.; Brey, R.; Crowther, M.; Derksen, R.; Erkan, D.; Krilis, S.; Machin, S.; Pengo, V.; et al. Evidence-Based Recommendations for the Prevention and Long-Term Management of Thrombosis in Antiphospholipid Antibody-Positive Patients: Report of a Task Force at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Lupus 2011, 20, 206–218.

- Cuadrado, M.J.; Bertolaccini, M.L.; Seed, P.T.; Tektonidou, M.G.; Aguirre, A.; Mico, L.; Gordon, C.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Egurbide, M.V.; Gil, A.; et al. Low-Dose Aspirin vs Low-Dose Aspirin plus Low-Intensity Warfarin in Thromboprophylaxis: A Prospective, Multicentre, Randomized, Open, Controlled Trial in Patients Positive for Antiphospholipid Antibodies (ALIWAPAS). Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014, 53, 275–284.

- Nikolopoulos, D.; Cetrez, N.; Lindblom, J.; Palazzo, L.; Enman, Y.; Parodis, I. Patients with NPSLE Experience Poorer HRQoL and More Fatigue than SLE Patients with No Neuropsychiatric Involvement, Irrespective of Neuropsychiatric Activity. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 2494–2502.

- Jönsen, A.; Bengtsson, A.A.; Nived, O.; Ryberg, B.; Sturfelt, G. Outcome of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus within a Defined Swedish Population: Increased Morbidity but Low Mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002, 41, 1308–1312.

- Baker, K.; Pope, J. Employment and Work Disability in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009, 48, 281–284.

- Mendelsohn, S.; Khoja, L.; Alfred, S.; He, J.; Anderson, M.; DuBois, D.; Touma, Z.; Engel, L. Cognitive Impairment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Is Negatively Related to Social Role Participation and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. Lupus 2021, 30, 1617–1630.

- Ahn, G.Y.; Kim, D.; Won, S.; Song, S.T.; Jeong, H.-J.; Sohn, I.-W.; Lee, S.; Joo, Y.B.; Bae, S.-C. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Impact on Mortality of Neuropsychiatric Lupus: A Prospective, Single-Center Study. Lupus 2018, 27, 1338–1347.

- Bortoluzzi, A.; Fanouriakis, A.; Silvagni, E.; Appenzeller, S.; Carli, L.; Carrara, G.; Cauli, A.; Conti, F.; Costallat, L.T.L.; De Marchi, G.; et al. Therapeutic Strategies and Outcomes in Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: An International Multicentre Retrospective Study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024, 63, 2711–2720.

- Kostopoulou, M.; Ugarte-Gil, M.F.; Pons-Estel, B.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; Bertsias, G. The Association between Lupus Serology and Disease Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review to Inform the Treat-to-Target Approach in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2022, 31, 307–318.

- Jiang, Y.; Yuan, F.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Zhao, C. Correlation between Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Immunological Markers: A Real-World Retrospective Study. Clin. Rheumatol. 2024, 43, 2833–2842.

- Abdul-Sattar, A.B.; Goda, T.; Negm, M.G. Neuropsychiatric Manifestations in a Consecutive Cohort of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; a Single Center Study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2013, 16, 715–723.

- Aso, K.; Kono, M.; Kono, M.; Watanabe, T.; Shimizu, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Fujieda, Y.; Kato, M.; Oku, K.; Amengual, O.; et al. Low C4 as a Risk Factor for Severe Neuropsychiatric Flare in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Lupus 2020, 29, 1238–1247.

- Zheng, J.; Gu, J.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Xiong, C.; Cao, H.; Quasny, H.; Chu, M.; Curtis, P.; et al. Efficacy of Belimumab in Patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus from North East Asia: Results of Exploratory Subgroup Analyses. Mod. Rheumatol. 2023, 33, 751–757.

- Hsu, T.-Y.; Wang, S.-H.; Kuo, C.-F.; Chiu, T.-F.; Chang, Y.-C. Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy as the Initial Presentation of Lupus. Am J Emerg Med 2009, 27, 900.e3-5.

| Central Nervous system | Peripheral Nervous system |

| Aseptic meningitis (0.3–2.7%) Cerebrovascular disease (8.0–15%) Headache (including migraine and benign intracranial hypertension) (12.2–28.3%) Movement disorder (chorea) (0.9%) Myelopathy (0.9–3.9%) Seizure disorders (7.0–20%) Acute confusional state (0.9–7%) Anxiety disorder (6.4–40%) Cognitive dysfunction (6.6–80%) Mood disorder (7.4–65%) Psychosis (0.6–11%) |

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (Guillain-Barre syndrome) (0.08–1.2%) Autonomic disorder (0.08–1.3%) Mononeuropathy, single/multiplex (0.9–6.9%) Myasthenia gravis (0.2%) Neuropathy, cranial (1.0%) Plexopathy (Not available data) Polyneuropathy (1.5–5.4%) |

| Mechanism | Description | Autoantibodies | Manifestations | References |

| The anti-P antiidiotypic antibody population could induce disease by binding to membrane receptors, as has been shown with experimentally induced antibodies to insulin and acetylcholine. | In 18 of 20 patients with psychosis secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), autoantibodies to ribosomal P proteins were detected by immunoblotting and measured with a new radioimmunoassay using a synthetic peptide as antigen. | Anti-ribosomal P protein antibodies (Anti-RP Ab) |

Psychosis | Bonfa et al. (1987) [28] |

| The strong association between aPL and NP manifestations in this study supports the theory that an occlusive vasculopathy may be a major mechanism for NPSLE | The study included 323 consecutive SLE patients and investigated the associations between aPL and neuropsychiatric manifestations. | Antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL antibodies) |

Cerebrovascular disease, headache, and seizures | Sanna et al. (2003) [29] |

| MAP-2, have repetitive microtubule-binding motifs, so that they not only control cytoskeletal integrity but also interact with other structural elements of the cell | Sera from 100 patients with SLE, 74 patients with other neurologic disorders and injuries, and 60 normal controls were examined both by enzyme immunoassays and by Western immunoblotting for autoantibodies to MAP-2 | Anti-microtubule-associated protein 2 antibodies (Anti-MAP-2 Ab) |

Psychosis, seizure, neuropathy, and cerebritis | Williams et al. (2004) [30] |

| It has been postulated that AECA reactivity may be due in part to the binding to a complex of β2-GPI with phospholipids on endothelial cells | This study included 51 unselected outpatients with SLE (44 women, 7 men; mean age 36.8 years, range 22–54 years; mean disease duration 9.4 years, range 0.5–26 years) | Anti-endothelial-cell antibodies (AECA) | Psychosis and mood disturbances | Conti et al. (2004) [31] |

| Suggesting that these antibodies, generated in the periphery, penetrate the CNS from the peripheral blood across the altered blood–brain barrier and bind to cell surfaces, possibly interfering with neuronal function | Investigate the potential role of circulating autoantibodies specific to neuronal cell surface antigens in the pathophysiology of neuropsychiatric disorders. | Antibodies against glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) |

Cognitive dysfunction | Delunardo et al. (2016) [32] |

| Test | Utility in Neurological SLE | Reference |

| MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) | The imaging technique of choice is MRI especiallyT2-weighted images. The most frequent pathological pattern is small punctate hyperintense T2-weighted focal lesions in subcortical and periventricular white matter (WM), usually in the frontal-parietal regions. Unfortunately, these MRI lesions are also present in many patients without neuropsychiatric manifestations. MRI can exclude multiple sclerosis, malignancy, infarction, subarachnoid hemorrhage. | Kozora et al. (1998) [152] Nomura et al. (1999) [153] Magro-Checa et al. (2016) [23] |

| Computed tomography | Used to exclude other causes of neurological symptoms such as bleeding, tumors and hemorrhage. | Magro-Checa et al. (2016) [23] |

| PET (Positron Emission Tomography) | SPECT imaging has detected both widespread and localized deficits in patients with SLE, which may be either persistent or reversible. SPECT imaging can be abnormal in up to half of patients with SLE with no clinical manifestations of neuropsychiatric disease. Thus, SPECT findings are not unique to SLE. | Sibbitt et al. (1999) [154] Waterloo et al. (2001) [155] |

| Autoantibody Profiling | Several circulating autoantibodies like apl (antiphospholipid antibodies) and β2-glycoprotein antibodies both correlate with disease activities specially with focal events such as cerebrovascular disease and seizures. Antiribosomal P antibodies found to be specifically related to lupus psychosis. Aquaporin 4 autoantibodies can help in the diagnostic process of a patient presenting with myelopathy and optic neuritis and Neuromyelitis optica (NMO). | Zirkzee et al. (2014) [156] Birnbaum et al. (2007) [157] Birnbaum et al. (2009) [158] |

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis | Help to exclude CNS infection in patients with fever or other signs and symptoms suggestive of infection; mild CSF abnormalities are common (40–50%) but are not specific to the neuropsychiatric SLE. It can exclude infection,malignancy,myasthenia gravis and oligoclonal bands. | Kozora et al. (1998) [152] Nomura et al. (1999) [153] 1/22/25 2:18:00 PM |

| Electroencephalogram (EEG) | EEG studies help to diagnose underlying seizure disorder. |

González-Duarte et al. (2008) [159] Appenzeller et al. (2004) [160] |

| Neuropsychological Testing | It’s carried out when suspicion of impaired cognitive abilities is present. Patients with suspected impaired cognitive ability should be referred for full neuropsychological assessment. | Hanly et al. (2014) [161] Zirkzee et al. (2012) [162] |

| Drug name | Mechanism of action | Indication | Administration | Side effects | References |

| Corticosteroids | Modulate immune response and inflammation via glucocorticoid receptors | First line drug and used to control of SLE flares (mild-severe) | IV Methylprednisolone (1g/day x 3 days), oral Prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) tapering over 3-12 months | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, osteoporosis, diabetes, cataract, glaucoma psychiatric issues (10% risk), infections, and peptic ulcer disease | Schäcke et al. (2002) [173] Bertsias et al. (2010) [76] Buttgereit et al. (2002) [174] |

| Cyclophosphamide | Impairs DNA replication and immune cell proliferation. It is a prodrug that is converted by liver cytochrome 450 enzymes to its metabolite 4-hydroxy cyclophosphamide. | Severe NPSLE manifestations, mainly CNS involvement | Monthly IV regimen (0.75–1.5 g/m²), 500 mg fixed dose in less severe cases | Alopecia, nausea, leukopenia, hemorrhagic cystitis, cardiotoxicity, gonadal failure | Hejaili et al. (2003) [175] Houssiau et al. (2010) [176] Ognenovski et al. (2004) [177] |

| Azathioprine | Inhibits purine synthesis, affects both cellular and humoral immune functions | Used as maintenance therapy. In prevention of flares. It is a first option in mild NPSLE symptoms as a glucocorticoid-sparing agent | Oral (2–3 mg/kg/day) | Bone marrow suppression, hepatotoxicity,increased risk of infection | DiPiero et al. (2015) [178] Oelzner et al. (1996) [179] |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | Inhibits lymphocyte proliferation via inosine-5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase | Maintenance after induction in renal SLE the efficacy of this drug in NPSLE patients is very modest and lacks strong evidence for its efficacy in neuropsychiatric symptoms | Oral (1000–3000 mg/day) | GI intolerance, bone marrow suppression, infections | Allison et al. (2005) [180] Pisoni et al. (2005) [181] |

| Methotrexate | Methotrexate is a folic acid antagonist. It inhibits IL-2 transcription, suppresses T-cell activity | Limited evidence for NPSLE, some reports suggest positive effects with intrathecal administration | Oral, subcutaneous, or intrathecal in CNS involvement | GI symptoms, stomatitis, increased levels of liver enzymes and mild cytopenia. In severe cases liver fibrosis, interstitial pneumonitis, and severe pancytopenia | Zhou et al. (2008) [182] Wang et al. (2014) [183] |

| Cyclosporin A | Inhibits IL-2 transcription, suppresses T-cell activity | Rarely used in NPSLE with Limited evidence, but may aid in organic brain syndrome and psychosis when combined with therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE) | Oral (2.5–3 mg/kg/day), sometimes with plasma exchange | Hypertension, renal dysfunction, hypertrichosis | Bambauer et al. (2000) [184] Yang et al. (2014) [185] |

| Rituximab | Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against the B-cell-specific antigen CD20. | It is used in severe refractory NPSLE. But, it lacks of long-term data. | IV (1000 mg doses separated by 15 days) | Infusion reactions, infections | Glennie et al. (2007) [186] Tokunaga et al. (2007) [134] |

| IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) |

Mixture of natural IgG antibodies derived from the blood of healthy donors. It inhibits the activity of autoreactive B lymphocytes and suppresses typeI interferon-driven differentiation of dendritic cells and reduces nucleosome endocytosis. | Positive effects in small case reports, with limited evidence. But, it is used a adjunctive therapy in refractory cases | IV administration 2g/kg, with divided doses over 2–5 days | Mild and self-limited such as headaches, fever, flushing, chills, arthralgia and myalgia. Infusion reactions, risk of thrombosis | Camara et al. (2014) [187] Milstone et al. (2005) [165] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).