Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

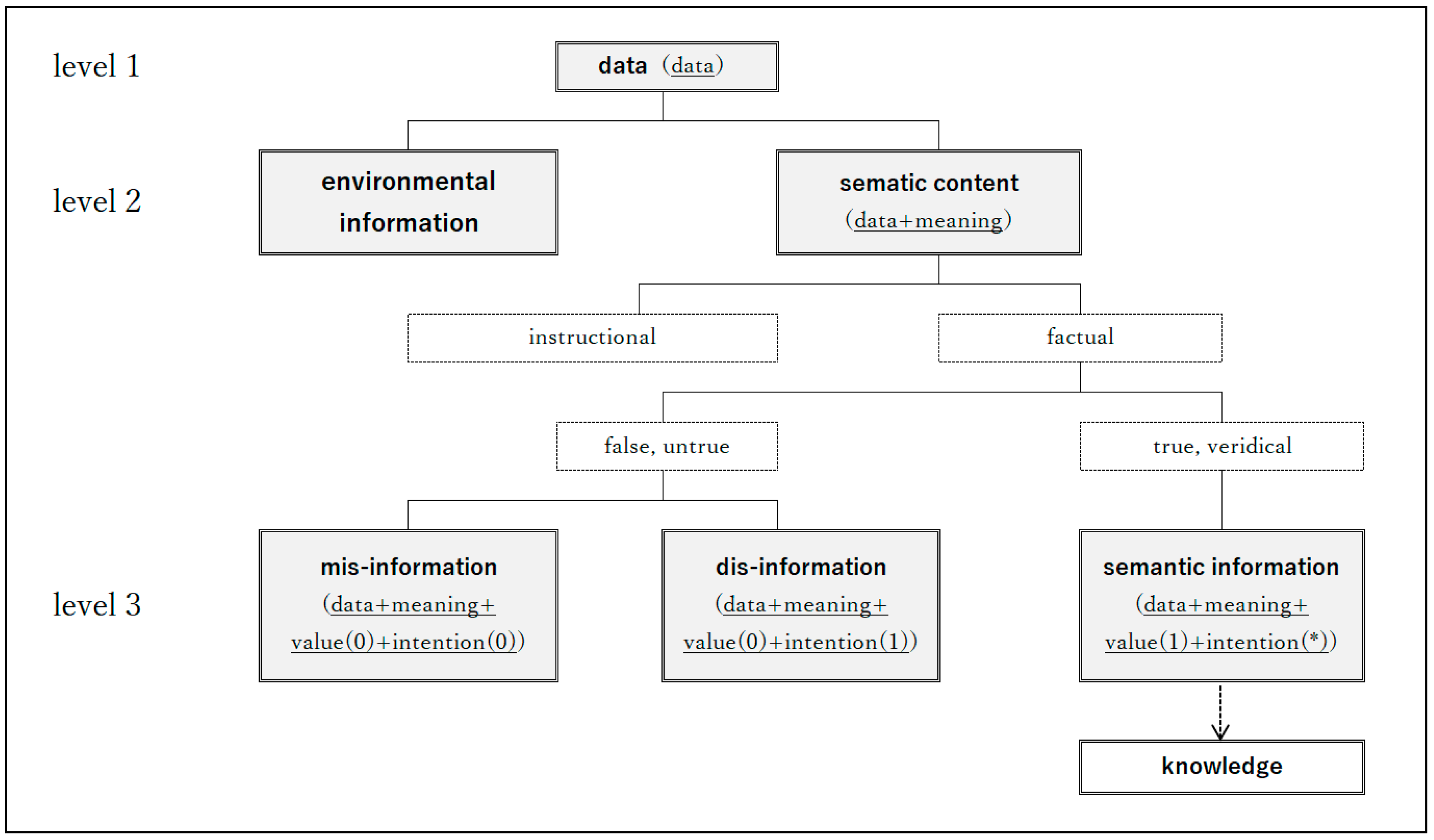

The definition of information concepts has been approached in various ways. Previous studies have classified these definitions into three categories: (1) reductionism, (2) antireductionism, and (3) non-reductionism. The map of information concepts developed by Luciano Floridi organizes information concepts in terms of (3) non-reductionism. However, the map is often criticized due to misunderstandings, since neither the specific method for constructing the map nor its structure is described in detail. The purpose of this paper is to reconstruct the map using the method of levels of abstraction (LoA) and to make its structure explicit. First, Section 2 reviews previous studies and organizes the definitions of information concepts based on the above classification scheme. Next, Section 3 explains the method of LoA and applies it to information concepts. As a result, it becomes clear that the map differs from the well-known DIKW pyramid in that each element is arranged by adding observables in order from higher to lower degrees of abstraction. This work allows us to demonstrate the relationship between the map and the method of LoA, and to re-evaluate Floridi’s achievement.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Classify Various Information Concepts

2.1. How to Classify Information Concepts

| reductionism | : | The position that any element can be reduced to one specific underlying element, with a linear, or hierarchical structure in which the various elements are arranged in a row. In some cases, there are branches within the hierarchical structure. |

| non-reductionism | : | All positions except reductionism and anti-reductionism. Each element is distributed and involves an interconnected network-like structure. |

| anti-reductionism | : | The position that each element refers to something different and that there is no interconnection between the elements. |

2.2. Various Information Concepts

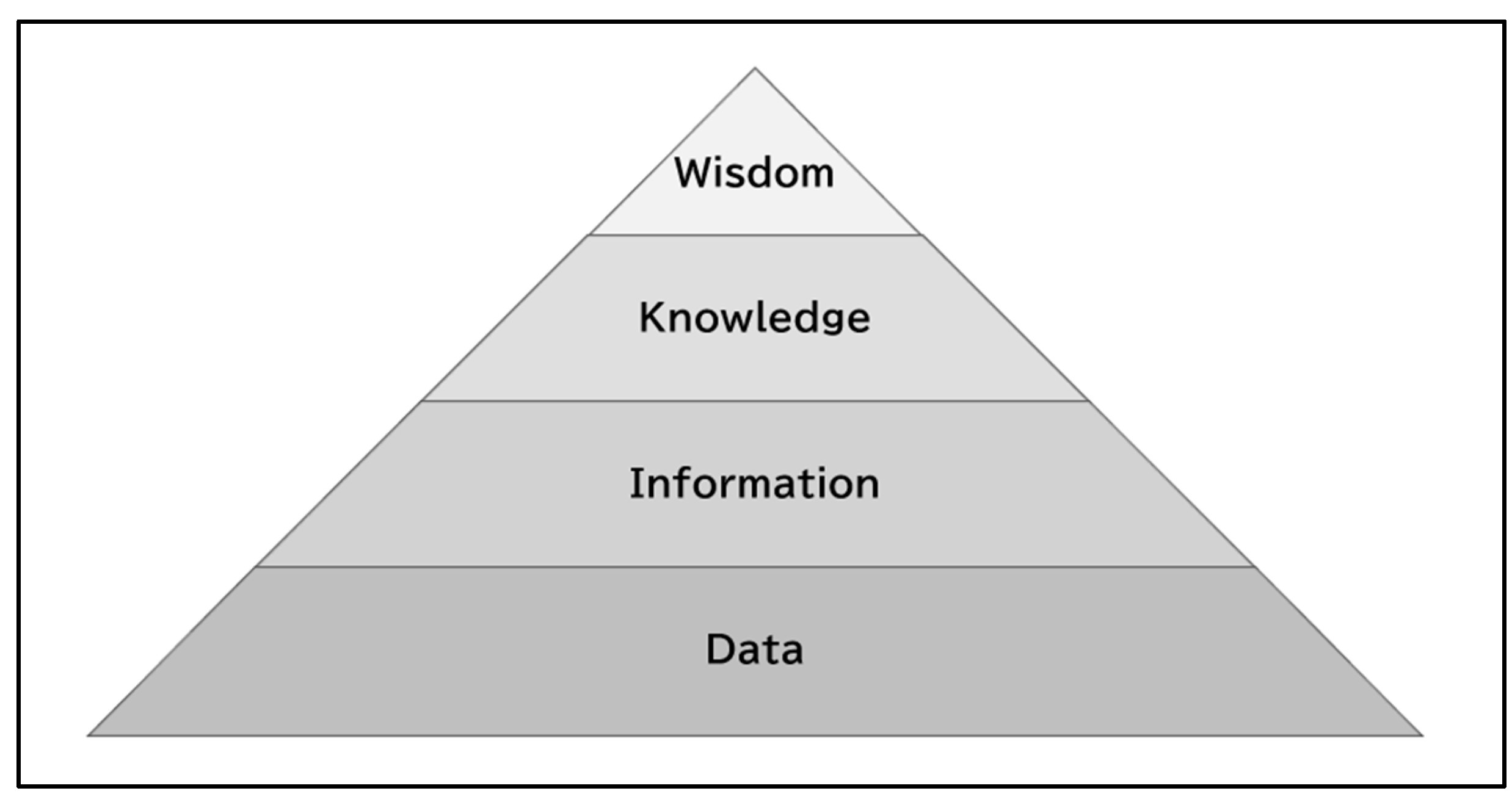

| ● Quantitative Assumptions | : | The image of the world is that there is more knowledge than wisdom, more information than knowledge, and more data than information. When we filter out the noise (in the everyday sense) from the many data in the world, information, knowledge, and wisdom are taken out in order. |

| ● Normative Assumptions | : | The image is of normatively superior wisdom positioned at the apex, and as it becomes less valuable, it is positioned at the bottom of the pyramid. |

2.2.1. Examples of Anti-Reductionism

2.2.2. Examples of Reductionism

2.3. Information Concept Map As Non-Reductionism

3. Actually Create a Map of Floridi’s Information Concepts

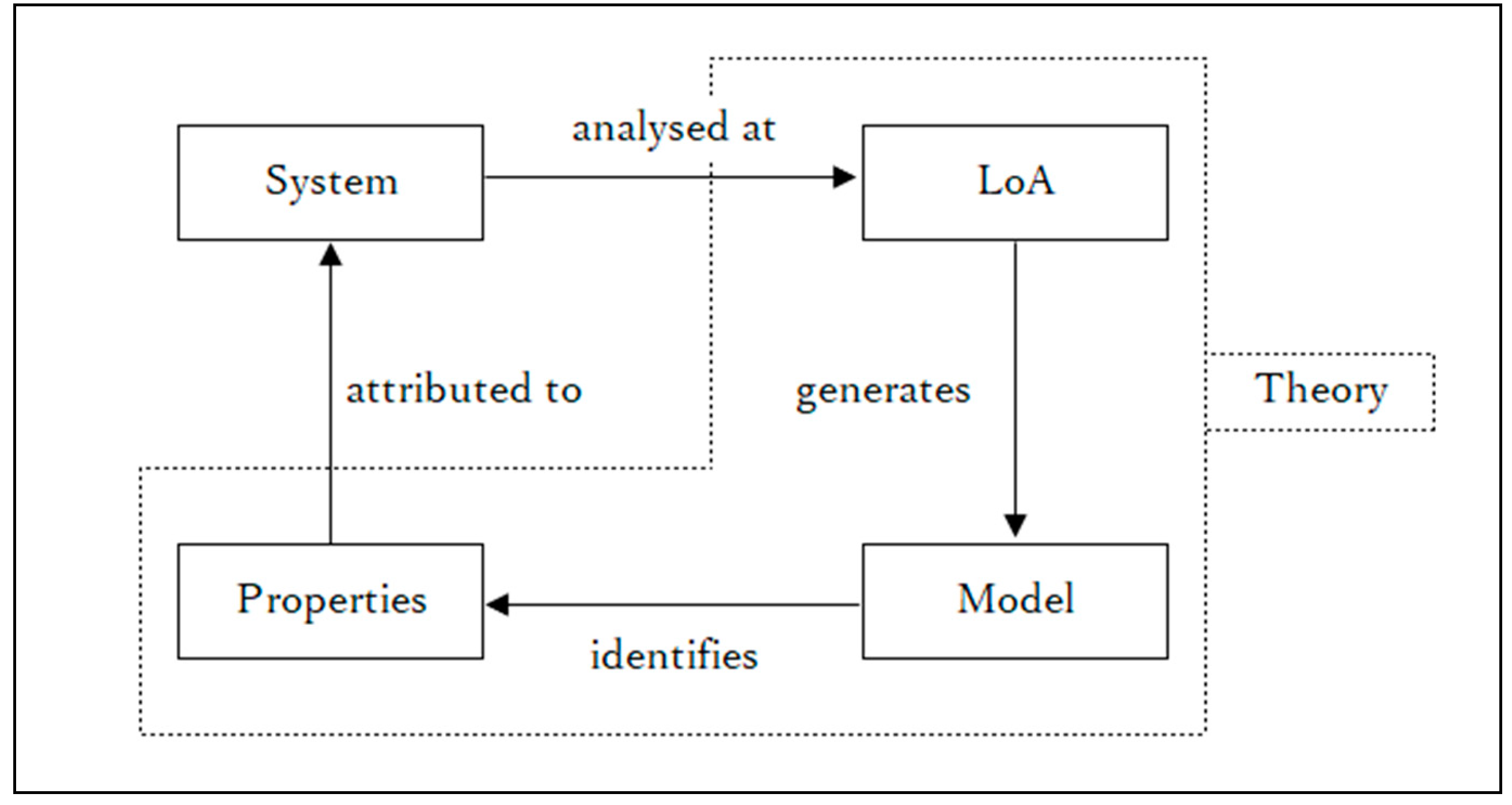

3.1. Overview of the Method of Level of Abstraction

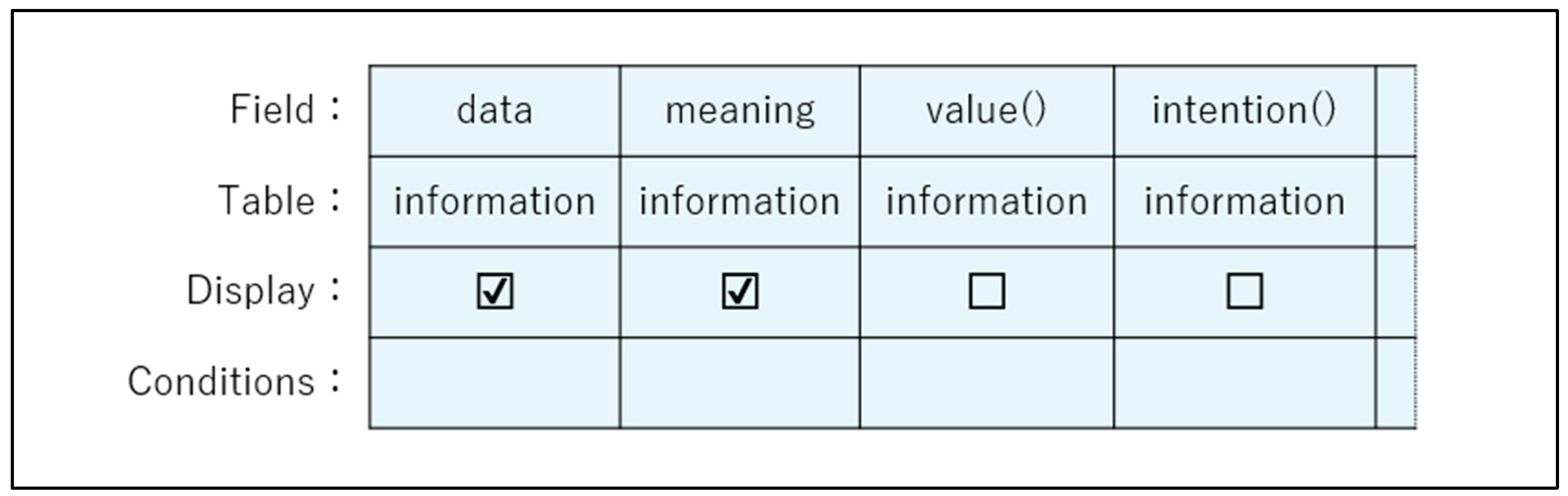

3.2. Application to Information Concepts

Conclusions

References

- Adriaans, P., and van Benthem, J. (eds.), 2008, Philosophy of Information: Handbook of The Philosophy of Science, Elsevier.

- Allow, P. (ed.), 2010, Putting Information First: Luciano Floridi and the Philosophy of Information, Wiley-Blackwell.

- Burgin, M., 2010, Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity, and Unification, World Scientific.

- Capurro, R., 2020, Pasado, presente y futuro de la noción de la información, in: Ápeiron. Estudios de filosofía, 12.

- Capurro, R., and Hjørland, B., 2003, The Concept of Information, Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 37, 343-411.

- D’Alfonso, S., 2012, Towards a Framework for Semantic Information, Ph.D. thesis, The University of Melbourne.

- D’Alfonso, S., 2013, Truth, in The Π Research Network, The Philosophy of Information - An Introduction, 90-99.

- Dretske, F., 1981, Knowledge and the Flow of Information, Blackwell.

- Floridi, L., 2004, Information, in: Floridi, L. (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Computing and Information, Oxford University Press, 40-. 61.

- Floridi, L., 2005a, Is Semantic Information Meaningful Data?”, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, LXX(2), 351-370.

- Floridi, L., 2005b, “Semantic Conceptions of Information”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed. .), URL = < https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2005/entries/information-semantic/>.

- Floridi, L., 2010, Information: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press.

- Floridi, L., 2011, The Philosophy of Information, Oxford University Press.

- Floridi, L., 2013, The Ethics of Information, Oxford University Press.

- Floridi, L. (ed.), 2016, The Routledge Handbook of the Philosophy of Information, Routledge.

- Floridi, L., 2019, The Logic of Information, Oxford University Press.

- Floridi, L. and Sanders, J., 2004, The Method of Abstraction, in M. Negrotti (ed.), Yearbook of Artificial, Nature, Culture and Technology, 2, Peter Lang, 177-220.

- Frické, M., 2019, The Knowledge Pyramid: the DIKW Hierarchy, Knowledge Organization, 46(1), 33-46.

- Iliadis, A., 2013, A quick history of the philosophy of information, in The Π Research Network, The Philosophy of Information - An Introduction , 9-27.

- Illari, P., 2013, What is the philosophy of information now? in The Π Research Network, The Philosophy of Information - An Introduction, 28 -42.

- Lundgren, B., 2019, Does semantic information need to be truthful?, Synthese, 196, 2885-2906.

- Mikkilineni, R., 2023, Mark Burgin’s Legacy: The General Theory of Information, the Digital Genome, and the Future of Machine Intelligence, Philosophies, 8(6), 107.

- Millikan, R., 2004, Varieties of Meaning, The MIT Press.

- Osgood, C., 1952, The nature and measurement of meaning, Psychological Bulletin, 49(3), 197-237.

- Ridi, R., 2020, La piramide dell’informazione: una introduzione, AIB Studi, 59(1-2).

- Rowley, J., 2007, The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy, Journal of information science, 33(2), 163-180.

- Rowley, J., and Hartley, R., 2008, Organizing Knowledge: An Introduction to Managing Access to Information, Routledge.

- Shannon, C., 1993, The Lattice Theory of Information, in: Sloane, N. and Wyner, A. (eds.), Claude Elwood Shannon: Collected Papers, IEEE Press, 180-183 .

- Scarantino, A., and Piccinini, G., 2010, Information without Truth, Metaphilosophy, 41(3), 313-330.

- Wiener, N., 1989, The Human Use of Human Beings: Cybernetics and Society, FREE ASSOCIATION BOOKS.

- Akio Akagi, 2006, Anti-Information Theory, Iwanami Shoten.

- Enomoto, T., 2023, A Database Understanding of Two “Abstractions” in the method of Level of Abstraction, The Philosophical Association of Kansai University, Philosophy, 41, 24-53.

- Kawashima, S., 2021, <in lieu of commentary> Multiple Approaches to the Construction of the Information Sphere: Floridi’s Information Theory and Neo-Cybernetics, in Floridi (translated by Shiozaki and Kawashima), For Philosophy of Information: From Data to Information Ethics, Keiso Shobo, 181-216.

- Sugino, T., 2016, Considering a New Definition of “Information”, 12th National Conference and Research Presentation Conference of the Association for Information Systems.

- Nishigaki, T., 2004, Fundamental Informatics: From Life to Society, NTT Publishing.

- Nishigaki, T., 2021, New Fundamental Informatics - Kikai wo Koeru Seimei - (New Fundamental Informatics - Life beyond Machines), NTT Publishing.

- Hagiya, M., 2014, Defining informatics─Reference standards in the field of informatics, IPSJ, 55(7), 734-743.

| 1 | For example, the meaning of "information" differs between fields that focus on the concept of information as semantic content, such as fake news, and those that focus on the topic of genetic information, which requires that responses be well-formed as a minimum. One of the possible misunderstandings that can arise in the absence of an organized concept is the misunderstanding that genes have information as semantic content. |

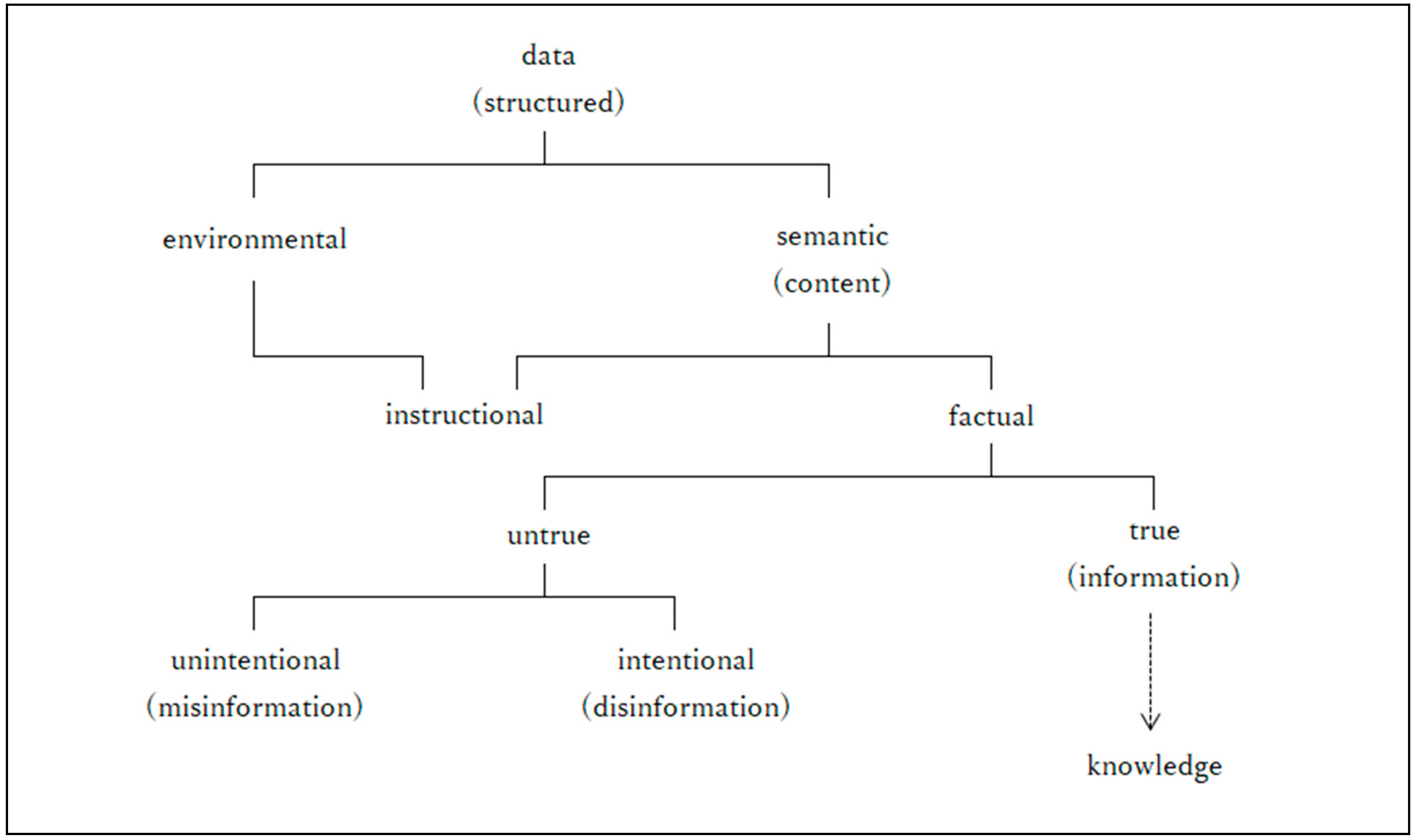

| 2 | The following are typical examples. For example, Scarantino and Piccinini criticize Floridi for his positive support of the Veridicality Thesis by pointing out that the concept of information is polysemous, and that he is a monist regarding the concept of information (Scarantino and Piccinini 2010). However, it is clear from reading the map of information concepts that this is a misunderstanding, and Floridi himself refutes this claim by saying that he himself is a pluralist (Allo ed. 2010, p. 157). Lundgren also criticizes the Information Concept Map, saying that it should be distinguished from truth-neutral information by establishing a subcategory that represents true (veridical) information, and the author believes that the Information Concept Map attempts to make an arrangement that includes exactly that distinction (Lundgren 2019). |

| 3 |

Some of the commentary and criticisms by Akagi (2006) appear to be based on misunderstandings. For example, there is no such fact, although it is stated as follows (Akagi 2006, pp. 65-77).

The second anti-reductionist theory, while attempting to offer a counterproposal to the right reductionist theory, tries to narrow down the source of the multiplicity of information to a single concept. [...] Despite the name "anti-reductionism," it merely opposes the first reductionism on the right, but has no substance at all.

The current mainstream philosophy of information, represented by Floridi, excludes reductionism and anti-reductionism from the philosophy of information and implicitly states that their success or failure should be handled by the philosophy of science.

Within the framework of the information philosophy, misinformation is excluded as not being information.

Further derivative misunderstandings have also spread, originating from the misunderstanding-based criticism by Akagi (cf. Sugino 2016, p. 3). It is obvious that the following quote is far removed from Floridi's view, which is organized in this paper ([10] in the quote is from Akagi (2006)).

Regarding the possibility of unifying the concept of information in an interdisciplinary way, Floridi sets out that information can be defined from three standpoints: reductionism, anti-reductionism, and non-reductionism, and then says that in effect there are only two types left: reductionism and non-reductionism [10]. [...] The broad scope of the concept of information probably means that it is difficult for philosophy to be fully responsible for its application to each of these fields.

|

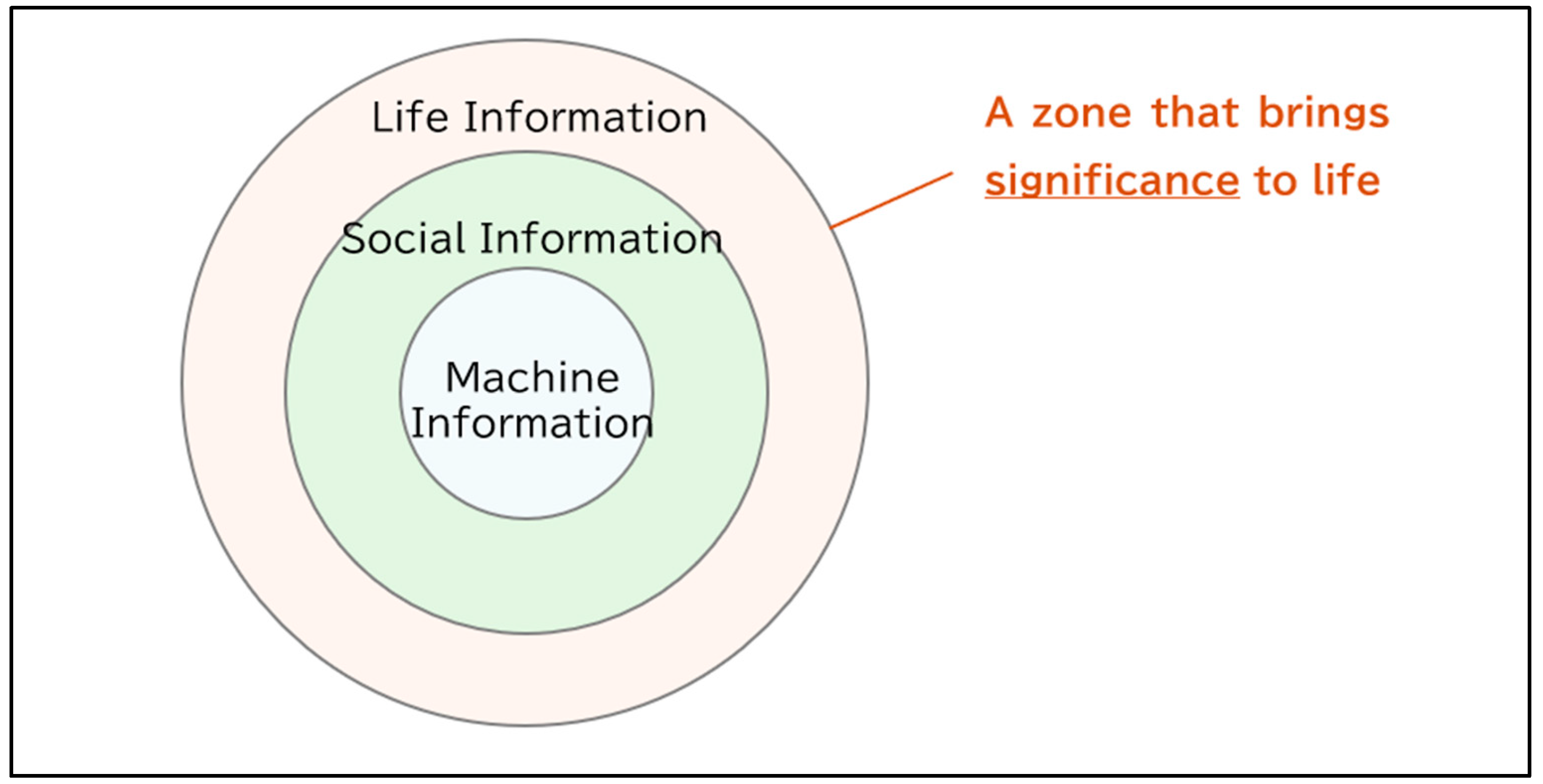

| 4 | According to Nishigaki, "information" emerges along with the semantic action involved in some life activity. Therefore, we cannot speak of information as if it were an external thing, ignoring the historical aspects that accompany life activity (Nishigaki 1998, p. 28; 2004, p. 23). |

| 5 | It should be noted that, coincidentally in this case, both sides view what could be called subjective information as fundamental. |

| 6 | Burgin's General Theory of Information (GTI) is similar to cybernetics in that it views information as “the ability to cause change” and in that it can be interpreted as an analysis of systems in an autopoietic way (Burgin 2010; Mikkilineni 2023). However, while cybernetics is a form of anti-reductionism, the author considers GTI to be a form of non-reductionism in that it seeks to explain the interrelatedness of different information elements in several dimensions. In that sense, even though GTI differs from Floridi's view of information (Floridi sees information as static, while GTI sees it as dynamic), it is still part of the non-reductionist camp, just like Floridi. Note, however, that this paper focuses on Floridi's map, so it mainly discusses Floridi as a representative example of non-reductionism. |

| 7 | At first glance, this seems strange. The reason I said in 2-1 that this classification scheme is "misleading" is because it runs counter to my intuition on this point. It should be noted that when Floridi speaks of "reductionism" in this context, the particular element of the reduction destination must have the privileged status of explaining other elements, such as "life information" in Fundamental informatics. |

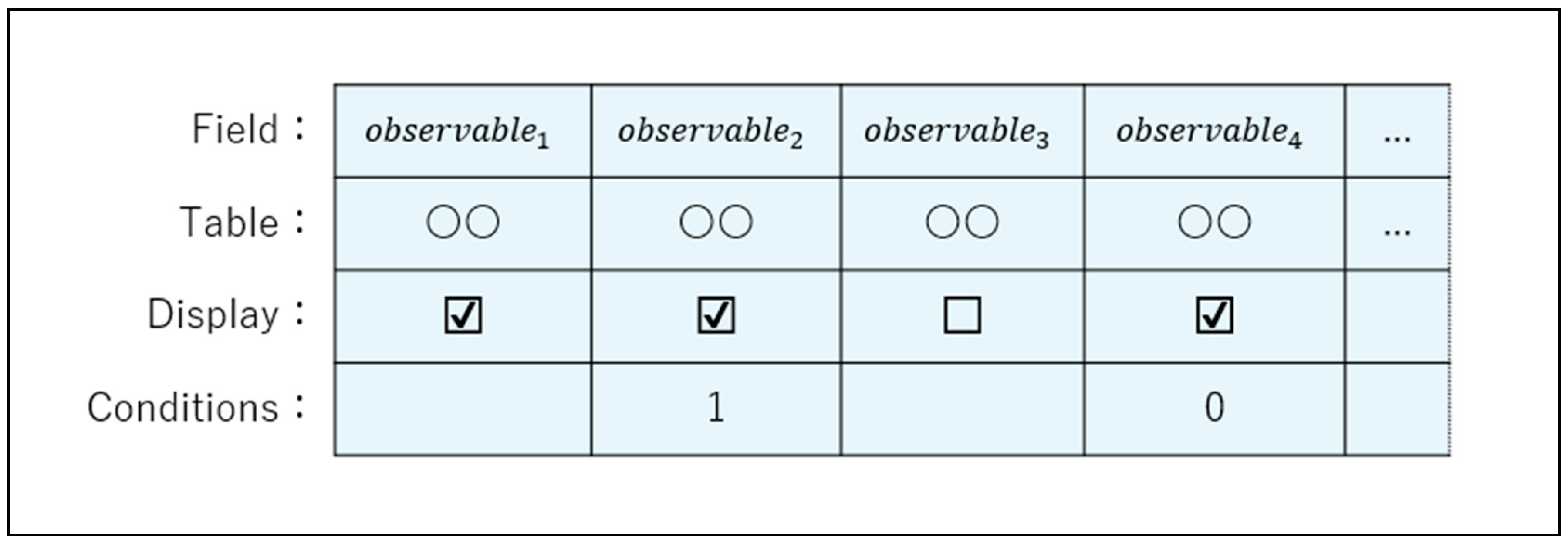

| 8 | Note that "table" in the figure originally means a two-dimensional table consisting of rows and columns, but here, for convenience, it is considered to mean the system to be analyzed. In addition, "extraction conditions" in the figure is a place to enter appropriate conditions when you wish to search for items that satisfy specific conditions. |

| 9 | A few more examples. The expression "semantic content" is common, but "directive semantic content" is not. While "semantic content" is already an established word, "directive" (and its counterpart "factual") are used to describe what the semantic content looks like. |

| 10 | The Japanese translation of Information: A Very Short Introduction (Floridi 2010), which contains a map of information concepts, translates "true" as "truthful" and "veridical" as "consistent with fact. However, Floridi states in several references that "true" and "veridical" (and "truthful") are synonymous and mean "true" in terms of truth value" (cf. Floridi 2005a, pp. 16-17). |

| 11 | Although "factual" appears before truth-value-related properties such as "true" and "untrue" in the original information concept map, Floridi points out that the property "factual" means having a truth value (Floridi 2011, Chapter 4). Therefore, in this chapter, by displaying the observable "value()", the property "factual" can be satisfied at the same time. On the other hand, some may point out, "Isn't it also important to bifurcate between factual and directive? The answer to this question is that the original information concept map is used to determine whether or not an element is placed at the destination of the branch, and whether or not it is adopted as an observable is determined by calculating backward from there. In this sense, it may be said that the candidates for observables are quite arbitrary. |

| 12 | The resulting LoA is a "moderated LoA" in that the observables "value()" and "intention()" have restrictions on the values that can be entered. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).