Submitted:

22 January 2025

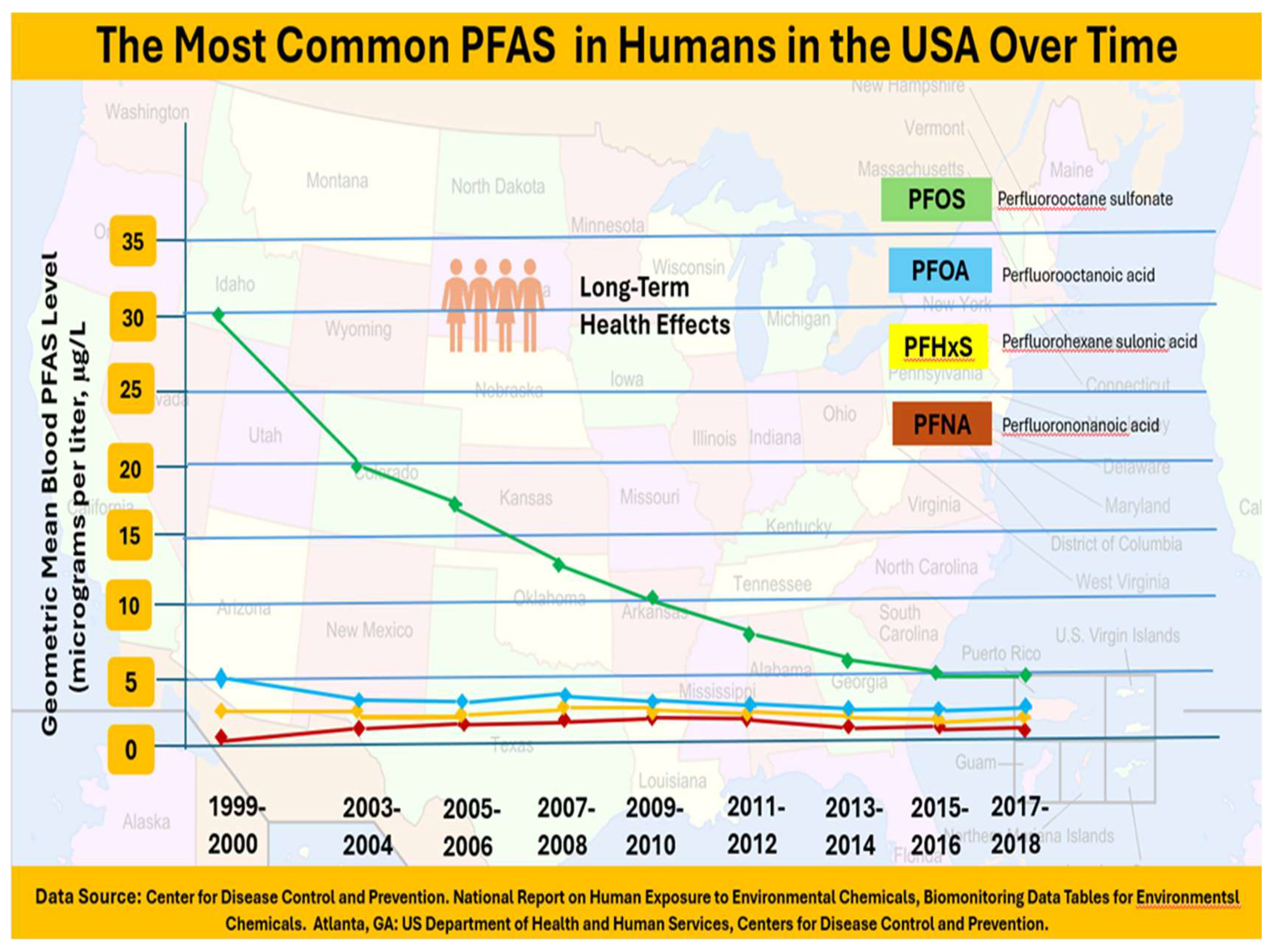

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are found everywhere including food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. This review introduces PFAS comprehensively, discussing their nature, identifying the interconnection with microplastics, and their impacts on public health and the environment. The Human cost of decades of delay, cover-ups, and mismanagement of PFAS and plastic waste has been outlined and briefly explained. Following that PFAS and long-term health effects have been criti-cally assessed. Risk assessment has then been critically reviewed mentioning different tools and models. Scientific Research and Health Impacts in the United States of America have been critically analyzed tak-ing into consideration the Center for Disease Control (CDC) PFAS Medical Studies and Guidelines. PFAS impact, activities, and studies around the world have focused on PFAS Levels in Food Products and Dietary Intake in Different Countries such as China, European countries, USA and Australia. Moreover, PFAS in Drinking Water and Food have been outlined with regard to risks, mitigation, and reg-ulatory needs taking into account chemical contaminants in food and their Impact on health and safety. Finally, PFAS impact and activities briefings specific to regions around the world refer to Australia, Vi-etnam, Canada, Europe, and the United States of America. Crisis Multi-Faceted Issue, exacerbated by mismanagement has been discussed in the context of applying problem-solving analytical tools: the Domino Effect Model of accident causation, the Swiss Cheese Theory Model, and the Ishikawa Fish Bone Root Cause Analyses. Last but not least, the PFAS impact on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of 2030 has been rigorously discussed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. PFAS Origins and Complacency

1.2. The Nexus between PFAS and Microplastics: An Emerging Threat to Public Health and the Environment

1.3. The Human Cost of Decades of Delay, Cover-Ups, and Mismanagement of PFAS and Plastic Waste

2. PFAS and Long-Term Health Effects

2.1. PFAS Around the Globe and Risk Assessment

2.2. Scientific Research and Health Impacts in the United States of America

2.3. Center for Disease Control (CDC) PFAS Medical Studies and Guidelines

3. PFAS Impact, Activities, and Studies Around the World

3.1. PFAS Levels in Food Products and Dietary Intake in Different Countries

- China:

- European Countries:

- USA and Australia:

3.2. PFAS in Drinking Water and Food: Risks, Mitigation, and Regulatory Needs

3.3. Chemical Contaminants in Food and Their Impact on Health and Safety

4. PFAS Impact and Activities Briefings: Regions Around the World

4.1. AUSTRALIA Briefing: PFAS Impact and Activities

4.2. VIET NAM Briefing: PFAS Impact and Activities

- o Phasing Out Production and Use: Gradually eliminating the manufacture and use of listed PFAS substances [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o Monitoring and Reporting: Regularly monitoring POPs in the environment and reporting findings to the Convention's Secretariat [228][ (UNEP, 2019).

- o Capacity Building: Enhancing national capabilities to manage and reduce POPs through training and technical assistance [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN): Vietnam works with IPEN to conduct surveys, research, and advocacy to eliminate toxic pollutants, including PFAS. This partnership supports Vietnam in developing strategies for PFAS management and remediation [223] (IPEN, 2020).

- o PanNature: As part of its membership in IPEN, PanNature engages in projects that monitor PFAS pollution and promote sustainable practices to reduce contamination [220] (PanNature, 2019).

- o ASEAN POPs Protocol: This regional agreement complements the Stockholm Convention by addressing POPs within Southeast Asia. Vietnam collaborates with neighboring countries to harmonize regulations, share best practices, and implement joint projects targeting PFAS reduction [229] (ASEAN, 2018).

- o Regional Workshops and Training Programs: Vietnam participates in regional capacity-building efforts, including training on PFAS detection, management, and remediation procedures [229] (ASEAN, 2018).

- o Joint Research Projects: Collaborative research initiatives focus on understanding the environmental and health impacts of PFAS, developing innovative remediation technologies, and assessing the effectiveness of regulatory measures [224] (Dai et al., 2022).

- o Knowledge Exchange Programs: These programs facilitate the exchange of expertise and technical knowledge between Vietnamese scientists and their international counterparts, fostering innovation in PFAS management [224] (Dai et al., 2022).

- o United Nations Environment Program (UNEP): UNEP provides technical assistance, funding, and guidance to help Vietnam implement PFAS regulations, conduct environmental assessments, and develop remediation strategies [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o World Bank and Other Funding Agencies: These organizations may fund projects to reduce PFAS pollution, improve waste management systems, and upgrade industrial processes to minimize PFAS emissions [230] (World Bank, 2020).

- o Global Chemical Safety Forums: These events provide platforms for Vietnamese policymakers and scientists to share experiences, learn about global advancements in PFAS management, and collaborate on international initiatives [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o Workshops and Seminars: Participation in specialized workshops helps Vietnam stay updated on the latest research, technologies, and regulatory trends related to PFAS [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o Incorporating Global Norms and Guidelines: Integrating global norms and guidelines into national legislation to regulate PFAS use and emissions effectively [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- o Public Awareness Campaigns: Leveraging international expertise to design and implement campaigns that educate the public and industries about the risks of PFAS and the importance of responsible chemical management [223] (IPEN, 2020).

- Expanding Monitoring Networks: Establishing more comprehensive PFAS monitoring systems with international partners [228] (UNEP, 2019).

- Innovative Remediation Technologies: Investing in innovative technologies developed through international research partnerships to remediate PFAS-contaminated sites effectively [224] (Dai et al., 2022).

- Policy Development Support: Receiving ongoing support to develop and enforce robust PFAS regulations aligned with global standards [230] (World Bank, 2020).

4.3. CANADA Briefing: PFAS Impact and Activities

4.4. EUROPE: PFAS Impact and Activities

4.5. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: PFAS Impact and Activities

5. Discussion

5.1. Crisis Multi-Faceted Issue, Exacerbated by Mismanagement

5.1.1. Domino Effect Model of Accident Causation

5.1.2. Swiss Cheese Model

5.1.3. Ishikawa Fish Bone Root Cause Analyses

5.2. The PFAS Impact on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of 2030

6. Conclusions

6.1. PFAS Crisis: A Multi-Faceted Issue Exacerbated by the Mismanagement of Waste

6.2. Wastewater and Landfills

6.3. PFAS in Plastics

6.4. Marine Life and Aqua Ecology

6.5. Consequences of PFAS Remediation in the Environment

6.6. Future Outlook and Sustainability

6.7. Summation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) |

References

- ITRC (2020) PFAS History and Use. Interstate Technology Regulatory Council Retrieved from:: https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/history_and_use_508_2020Aug_Final.pdf) [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- EWG (2021). Timeline: The PFOA saga. Environmental Working Group. Retrieved from:: https://www.ewg.org/research/timeline-forever-chemicals-and-firefighters [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- UCSUSA (2019). Dark Waters - The Lawyer Who Became DuPont's Worst Nightmare. Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved from: https://blog.ucsusa.org/genna-reed/dark-waters-speaks-the-truth-about-pfas/ [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- NIH US National Library of Medicine (2021). PFAS and health effects. Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK584690/ [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Lerner, S. (2024) How 3M Executives Convinced a Scientist the Forever Chemicals She Found in Human Blood Were Safe. 20th May. Retrieved from: https://www.propublica.org/article/3m-forever-chemicals-pfas-pfos-inside-story [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Pruitt, S. (2020) The Post World War II Boom: How America Got Into Gear. Retrieved from: https://www.history.com/news/post-world-war-ii-boom-economy) [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- ATSDR (2022) PFAS Exposure Assessments. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/activities/assessments.html. [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- ITRC (2023) 9 Site Risk Assessment- PFAS - Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Interstate Technology Regulatory Council Retrieved from: https://pfas-1.itrcweb.org/9-site-risk-assessment/. [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Balbuena,N. et al (2023) How Chemical Makers Hid the Truth About PFAS. Retrieved from: https://www.foodandwaterwatch.org/2023/11/08/pfas-coverups/. [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Tullo, A. (2021) C&EN’s top 50 US chemical producers for 2021. Retrieved from: https://cen.acs.org/business/finance/CENs-top-50-US-chemical-producers-for-2020/99/i17. [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Reed, G. (2019) DuPont's Worst Nightmare. Retrieved from: https://blog.ucsusa.org/genna-reed/dark-waters-speaks-the-truth-about-pfas/ [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Smith, J., Doe, A., & White, R. (2020). Interactions between PFAS and Microplastics in the Environment. Environmental Science & Technology, 54(12), pp. 12345-12350.

- Jones, L. & Brown, M. (2021). The PFAS and Microplastics Nexus: Implications for Public Health and Environmental Policy. Journal of Environmental Management, 278, pp. 111-120.

- ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (2024) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Your Health, 18th January. Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/index.html [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- NOAA National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2024) Microplastics and the Environment: Research and Guidelines |National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 10th June. Retrieved from: https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/search-md-website?search_api_fulltext=microplastics+and+the+environment+research+and+guidelines [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Bakir, A., Rowland, S. J., & Thompson, R. C. (2012). Competitive sorption of persistent organic pollutants onto microplastics in the marine environment. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 64 (12), 2782-2789.

- Wang, X., Wang, Y., Li, J., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., & Wu, Y. (2021). Occurrence and dietary intake of Perfluoroalkyl substances in foods of the residents in Beijing, China. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 14(1), 1-11.

- Rochman, C. M., Tahir, A., Williams, S. L., Baxa, D. V., Lam, R., Miller, J. T., ... & Teh, S. J. (2015). Anthropogenic debris in seafood: Plastic debris and fibers from textiles in fish and bivalves sold for human consumption. Scientific Reports, 5 (14340).

- Fossi, M. C., Marsili, L., Baini, M., Giannetti, M., Coppola, D., Guerranti, C., ... & Moscatelli, A. (2016). Fin whales and microplastics: The Mediterranean Sea and the Sea of Cortez scenarios. Environmental Pollution, 209, 68-78.

- Toms, L. M. L., Calafat, A. M., Kato, K., Thompson, J., Harden, F., Hobson, P., ... & Mueller, J. F. (2009). Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in pooled human serum from Australia in 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(11), 4194-4199.

- Teuten, E. L., Saquing, J. M., Knappe, D. R. U., Barlaz, M. A., Jonsson, S., Bjorn, A., ... & Takada, H. (2009). Transport and release of chemicals from plastics to the environment and to wildlife. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. Biological Sciences, 364*(1526), 2027-2045.

- NOAA (2024a) Addressing the Challenges of Plastics and PFAS. Environmental Defense Fund. 26th January. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved from: https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/research/influence-environmental-conditions-contaminants-leaching-and-sorbing-marine-microplastic [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- Merkl A and Charles D (2022) The Price of Plastic Pollution: Social Costs and Corporate Liabilities, Minderoo Foundation Pty Ltd. Retrieved from: (https://www.beyondplastics.org/reports/the-price-of-plastic-pollution The-Price-of-Plastic-Pollution.pdf (SECURED) (squarespace.com)) [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- MPCA Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (2023) Groundbreaking study shows unaffordable costs of PFAS cleanup from wastewater. 6th June. Retrieved from: https://www.pca.state.mn.us/news-and-stories/groundbreaking-study-shows-unaffordable-costs-of-pfas-cleanup-from-wastewater. [Accessed 27th September 2024].

- EPA US Environmental Protection Agency (2024). PFAS Explained | US EPA. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Ao, J., Yuan, T., Xia, H., Ma, Y., Shen, Z., Shi, R., 2019. Characteristic and human exposure risk assessment of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: a study based on indoor dust and drinking water in China. Environ. Pollut. 254 (Pt A), 112873.

- Cao, H., Zhou, Z., Hu, Z., Wei, C., Li, J., Wang, L., 2022. Effect of Enterohepatic Circulation on the Accumulation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: evidence from Experimental and Computational Studies. Environ. Sci Technol. 56 (5), 3214–3224.

- Jane, L.Espartero.L., Yamada, M., Ford, J., Owens, G., Prow, T., Juhasz, A., 2022. Health-related toxicity of emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: comparison to legacy PFOS and PFOA. Environ. Res. 212 (Pt C), 113431.

- Amstutz, V.H., Cengo, A., Gehres, F., Sijm, D.T.H.M., Vrolijk, M.F., 2022. Investigating the cytotoxicity of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in HepG2 cells: a structure-activity relationship approach. Toxicology 480, 153312.

- Ojo, A.F., Xia, Q., Peng, C., Ng, J.C., 2021. Evaluation of the individual and combined toxicity of perfluoroalkyl substances to human liver cells using biomarkers of oxidative stress. Chemosphere 281, 130808.

- Solan, M.E., Senthilkumar, S., Aquino, G.V., Bruce, E.D., Lavado, R., 2022. Comparative cytotoxicity of seven per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in six human cell lines. Toxicology 477, 153281.

- Xu, M., Wan, J., Niu, Q., Liu, R., 2019. PFOA and PFOS interact with superoxide dismutase and induce cytotoxicity in mouse primary hepatocytes: a combined cellular and molecular methods. Environ. Res. 175, 63–70.

- Xu, M., Liu, G., Li, M., Huo, M., Zong, W., Liu, R., 2020. Probing the cell apoptosis pathway induced by perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate at the subcellular and molecular levels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 68 (2), 633–641.

- Donat-Vargas, C., Bergdahl, I.A., Tornevi, A., Wennberg, M., Sommar, J., Koponen, J., 2019. Associations between repeated measure of plasma perfluoroalkyl substances and cardiometabolic risk factors. Environ. Int. 124, 58–65.

- Huang, M., Jiao, J., Zhuang, P., Chen, X., Wang, J., Zhang, Y., 2018. Serum polyfluoroalkyl chemicals are associated with risk of cardiovascular diseases in national US population. Environ. Int. 119, 37–46.

- Conley, J.M., Lambright, C.S., Evans, N., McCord, J., Strynar, M.J., Hill, D., 2021. Hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid (HFPO-DA or GenX) alters maternal and fetal glucose and lipid metabolism and produces neonatal mortality, low birthweight, and hepatomegaly in the Sprague-Dawley rat. Environ. Int. 146, 106204.

- Moro, G., Liberi, S., Vascon, F., Linciano, S., De Felice, S., Fasolato, S., 2022. Investigation of the interaction between human serum albumin and branched short-chain perfluoroalkyl compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 35 (11), 2049–2058.

- Solan, M.E., Koperski, C.P., Senthilkumar, S., Lavado, R., 2023. Short-chain per- and polyfluoralkyl substances (PFAS) effects on oxidative stress biomarkers in human liver, kidney, muscle, and microglia cell lines. Environ. Res. 223, 115424.

- Wen, Y., Mirji, N., Irudayaraj, J., 2020. Epigenetic toxicity of PFOA and GenX in HepG2 cells and their role in lipid metabolism. Toxicol. In Vitro 65, 104797.

- Yang, Y.D., Li, J.X., Lu, N., Tian, R., 2023a. Serum albumin mitigated perfluorooctane sulfonate-induced cytotoxicity by affecting the cellular responses. Biophys. Chem. 302, 107110.

- Yang, Y.D., Tian, R., Lu, N., 2023b. Binding of serum albumin to perfluorooctanoic acid reduced cytotoxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 876, 162738.

- Alesio, J.L., Slitt, A., Bothun, G.D., 2022. Critical new insights into the binding of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to albumin protein. Chemosphere 287 (Pt 1), 131979.

- Bangma, J., Szilagyi, J., Blake, B.E., Plazas, C., Kepper, S., Fenton, S.E., 2020. An assessment of serum-dependent impacts on intracellular accumulation and genomic response of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a placental trophoblast model. Environ. Toxicol. 35 (12), 1395–1405.

- Beesoon, S., Martin, J.W., 2015. Isomer-specific binding affinity of perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) to serum proteins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (9), 5722–5731.

- Chen, H., Wang, X., Zhang, C., Sun, R., Han, J., Han, G., ... & He, X. (2017). Occurrence and inputs of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) from rivers and drain outlets to the Bohai Sea, China. Environmental Pollution, 221, 234-243.

- Chi, Q., Li, Z., Huang, J., Ma, J., Wang, X., 2018. Interactions of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid with serum albumins by native mass spectrometry, fluorescence and molecular docking. Chemosphere 198, 442–449.

- Crisalli, A.M., Cai, A., Cho, B.P., 2023. Probing the Interactions of Perfluorocarboxylic Acids of Various Chain Lengths with Human Serum Albumin: calorimetric and Spectroscopic Investigations. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 36 (4), 703–713.

- Jackson, T.W., Scheibly, C.M., Polera, M.E., Belcher, S.M., 2021. Rapid characterization of human serum albumin binding for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances using differential scanning fluorimetry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55 (18), 12291–12301.

- Qin, P., Liu, R., Pan, X., Fang, X., Mou, Y., 2010. Impact of carbon chain length on binding of perfluoroalkyl acids to bovine serum albumin determined by spectroscopic methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 58 (9), 5561–5567.

- Zhang, R., Zhang, H., Chen, B., Luan, T., 2020. Fetal bovine serum attenuating perfluorooctanoic acid-inducing toxicity to multiple human cell lines via albumin binding. J. Hazard. Mater. 389, 122109.

- Peng, Shi-Ya, Ya-Di Yang, Rong Tian, Naihao Lu. Critical new insights into the interactions of hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid (GenX or HFPO-DA) with albumin at molecular and cellular levels. Journal of Environmental Sciences 149 (2025) 88–98.

- Rafiee, A., Sasan Faridi, Peter D. Sly, Lara Stone, Lynsey P. Kennedy, E. Melinda Mahabee-Gittens. Asthma and decreased lung function in children exposed to perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): An updated meta-analysis unveiling research gaps. Environmental Research 262 (2024) 119827.

- Starnes, H.M., Rock, K.D., Jackson, T.W., Belcher, S.M., 2022. A critical review and meta- analysis of impacts of per- and polyfluorinated substances on the brain and behavior. Front Toxicol 4, 881584.

- Haug, L.S., Huber, S., Becher, G., Thomsen, C., 2011. Characterisation of human exposure pathways to perfluorinated compounds - comparing exposure estimates with biomarkers of exposure. Environ. Int. 37 (4), 687–693. [CrossRef]

- Daly, E.R., Chan, B.P., Talbot, E.A., Nassif, J., Bean, C., Cavallo, S.J., et al., 2018. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance (PFAS) exposure assessment in a community exposed to contaminated drinking water, New Hampshire, 2015. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health 221, 569–577.

- Graber, J.M., Alexander, C., Laumbach, R.J., Black, K., Strickland, P.O., Georgopoulos, P. G., et al., 2019. Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) blood levels after contamination of a community water supply and comparison with 2013-2014 NHANES. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 29, 172–182.

- Rocabois, A., Margaux Sanchez, Claire Philippat, Am´elie Cr´epet, Blanche Wies, Martine Vrijheid, Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, R´emy Slama. Chemical exposome and children health: Identification of dose-response relationships from meta-analyses and epidemiological studies. Environmental Research 262 (2024) 119811.

- Schillemans T, Donat-Vargas C, Akesson A. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl sub¬stances and cardiometabolic diseases: a review. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;134(1):141–52.

- Ford, Lucie C., Hsing-Chieh Lin, Yi-Hui Zhou, Fred A. Wright, Vijay K. Gombar, Alexander Sedykh, Ruchir R. Shah, Weihsueh A. Chiu and Ivan Rusyn. Characterizing PFAS hazards and risks: a human population-based in vitro cardiotoxicity assessment strategy. Human Genomics (2024) 18:92 . [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, C., D’Hollander, W., Roosens, L., Covaci, A., Smolders, R., Van Den Heuvel, R., Govarts, E., Van Campenhout, K., Reynders, H., Bervoets, L., 2012. First assessment of population exposure to perfluorinated compounds in Flanders, Belgium. Chemosphere 86 (3), 308–314. [CrossRef]

- Stubleski, J., Salihovic, S., Lind, L., Lind, P.M., van Bavel, B., K¨arrman, A., 2016. Changes in serum levels of perfluoroalkyl substances during a 10-year follow-up period in a large population-based cohort. Environ. Int. 95, 86–92. [CrossRef]

- Sifakis, S., Androutsopoulos, V.P., Tsatsakis, A.M., Spandidos, D.A., 2017. Human exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals: effects on the male and female reproductive systems. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 51, 56–70. [CrossRef]

- Smarr, M.M., Kannan, K., Buck Louis, G.M., 2016. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 106 (4), 959–966. [CrossRef]

- Cousins, F.L., McKinnon, B.D., Mortlock, S., Fitzgerald, H.C., Zhang, C., Montgomery, G. W., Gargett, C.E., 2023. New concepts on the etiology of endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49 (4), 1090–1105. [CrossRef]

- de Haro-Romero, T., Francisco M. Peinado, Fernando Vela-Soria, Ana Lara-Ramos , Jorge Fern´andez-Parra, Ana Molina-Lopez, Alfredo Ubi˜na, Olga Oc´on, Francisco Artacho-Cord´on, Carmen Freire. Association between exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and endometriosis in the ENDEA case-control study. Science of the Total Environment 951 (2024) 175593.

- Giesy, J.P., Kannan, K., Jones, P.D., & Hilscherova, K., 2004. Perfluorinated chemicals in the environment: A review. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 179, pp. 1-110. [CrossRef]

- Hammarstrand, S., Jakobsson, K., Andersson, E., Xu, Y., Li, Y., Olovsson, M., Andersson, E.M., 2021. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in drinking water and risk for polycystic ovarian syndrome, uterine leiomyoma, and endometriosis: a Swedish cohort study. Environ. Int. 157 (March), 106819 . [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Fletcher, T., Mucs, D., Scott, K., Lindh, C.H., Tallving, P., Jakobsson, K., 2018. Half-lives of PFOS, PFHxS and PFOA after end of exposure to contaminated drinking water. Occup. Environ. Med. 75, 46–51. [CrossRef]

- Rickard, B.P., Rizvi, I., Fenton, S.E., 2022. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and female reproductive outcomes: PFAS elimination, endocrine-mediated effects, and disease. Toxicology 465 (June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Bjerve, K., Småstuen, L., Thomsen, C., Sabaredzovic, A., Becher, G., Brunborg, G., 2012. Placental transfer of perfluorinated compounds is selective – a Norwegian Mother and Child sub-cohort study. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 215 (2), 216–219. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.08.011.

- Domínguez-Liste, A., de Haro-Romero, T., Quesada-Jim´enez, R., P´erez-Cantero, A., Peinado, F.M., Ballesteros, ´O., Vela-Soria, F., 2024. Multiclass determination of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in meconium: first evidence of Perfluoroalkyl substances in this biological compartment. Toxics 12 (1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R., White, N., Br¨aunig, J., Vijayasarathy, S., Mueller, J.F., Knox, C.L., Harden, F. A., Pacella, R., Toms, L.M.L., 2020. Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in follicular fluid from women experiencing infertility in Australia. Environ. Res. 190 (July) . [CrossRef]

- Vela-Soria, F., Serrano-L´opez, L., García-Villanova, J., de Haro, T., Olea, N., Freire, C., 2020. HPLC-MS/MS method for the determination of perfluoroalkyl substances in breast milk by combining salt-assisted and dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412 (28), 7913–7923. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P., Liu, Y., An, Q., Yang, X., Yin, S., Ma, L.Q., Liu, W., 2022. Prenatal and postnatal exposure to emerging and legacy per/poly fluoroalkyl substances: levels and transfer in maternal serum, cord serum, and breast milk. Sci. Total Environ. 812 . [CrossRef]

- Fabelova, L., Beneito, A., Casas, M., Colles, A., Dalsager, L., Den Hond, E., Dereumeaux, C., Ferguson, K., Gilles, L., Govarts, E., Irizar, A., Lopez Espinosa, M.J., Montazeri, P., Morrens, B., Patayov´a, H., Rausov´a, K., Richterov´a, D., Rodriguez Martin, L., Santa-Marina, L., Murínov´a, Palkoviˇcov´a, 2023. PFAS levels and exposure determinants in sensitive population groups. Chemosphere 313, 1–29. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.137530.

- Freire, C., Vela-Soria, F., Castiello, F., Salamanca-Fern´andez, E., Quesada-Jim´enez, R., L´opez-Alados, M.C., Fern´andez, M., Olea, N., 2023. Exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and association with thyroid hormones in adolescent males. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 252. [CrossRef]

- McAdam, J., Bell, E.M., 2023. Determinants of maternal and neonatal PFAS concentrations: a review. Environ. Health 22 (1), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Richterova, D., Govartsb, E., Fabelova, L., Rausova, K., Martin, L.R., Gilles, L., Remy, S., Colles, A., Rambaudc, L., Riouc, M., Gabrield, C., Sarigiannisd, D., Pedraza-Diaze, S., Ramose, J.J., Kosjekf, T., Tratnikf, J.S., Lignellg, S., Gyllenhammarg, I., Thomsenh, C., Murínovaa, Ľ.P., 2023. PFAS levels and determinants of variability in exposure in European teenagers – Results from the HBM4EU aligned studies (2014–2021). Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 247. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Mustieles, V., Wang, Y., Sun, Y., Agudelo, J., Bibi, Z., Torres, N., Oulhote, Y., Slitt, A., Messerlian, C., 2023. Folate concentrations and serum perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in adolescents and adults in the USA (National Health and Nutrition Examination Study 2003–16): an observational study. Lancet Planet. Health 7 (6), e449–e458. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Yu Qiu, Yuying Wu, Husheng Li, Han Yang, Qingrong Deng, Baochang He, Fuhua Yan, Yanfen Li and Fa Chen. Association of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) with periodontitis: the mediating role of sex hormones. BMC Oral Health (2024) 24:243. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Xingren Wang, Tingting Ou, Lei Huang & Bin He. Association between family economic situation and serum PFAS concentration in American adults with hypertension and hyperlipemia. Scientific Reports | (2024) 14:20799 | . [CrossRef]

- Koulini, G. V. and Indumathi M. Nambi. Occurrence of forever chemicals in Chennai waters, India. Environmental Sciences Europe (2024) 36:60 . [CrossRef]

- Belmaker, I., Evelyn D. Anca, Lisa P. Rubin, Hadas Magen-Molho, Anna Miodovnik and Noam van der Hal. Adverse health effects of exposure to plastic, microplastics and their additives: environmental, legal and policy implications for Israel. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research (2024) 13:44 . [CrossRef]

- Biggeri, A., Giorgia Stoppa, Laura Facciolo, Giuliano Fin, Silvia Mancini, Valerio Manno, Giada Minelli, Federica Zamagni, Michela Zamboni, Dolores Catelan and Lauro Bucchi. All-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality in the population of a large Italian area contaminated by perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (1980–2018). Environmental Health (2024) 23:42 . [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (EFSA CONTAM Panel), Schrenk D, Bignami M, Bodin L, Chipman JK, del Mazo J, Grasl-Kraupp B, et al. Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food. EFSA J 2020; 18. [CrossRef]

- Iulini, M., Giulia Russo, Elena Crispino, Alicia Paini, Styliani Fragki, Emanuela Corsini, Francesco Pappalardo. Advancing PFAS risk assessment: Integrative approaches using agent-based modeling and physiologically based kinetic for environmental and health safety. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 23 (2024) 2763–2778.

- ATSDR (2024a). PFAS in the U.S. Population | ATSDR 18th January Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease. Registry Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/us-population.html : (Accessed 27th September 2024).

- CDC (2024) cdc.gov/exposurereport/data.tables.html. Retrieved from:CDC (2024). Food Safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/food-safety/index.html (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- ATSDR (2016) Community Health Assessments, 18th October | Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/hac/index.html (Accessed 27th September 2024).

- CDC (2024a) PFAS Information for Clinicians. Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/resources/pfas-information-for-clinicians.html (Accessed 27th September 2024).

- EPA (2024c) Key EPA Actions to Address PFAS 1st September. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/key-epa-actions-address-pfas (Accessed 27th September 2024).

- EPA (2024d). ‘Fact Sheet Treatment Options from Drinking Water’ 1st April, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-04/pfas-npdwr_fact-sheet_treatment_4.8.24.pdf (Accessed 27th September 2024).

- ATSDR (2024b). PFAS in the U.S. Population 18th January| Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/us-population.html. Acceded October 2024.

- Starling, M. C. V., Rodrigues, D. A., Miranda, G. A., Jo, S., Amorim, C. C., Ankley, G. T., & Simcik, M. (2024). Occurrence and potential ecological risks of PFAS in Pampulha Lake, Brazil, a UNESCO world heritage site. Science of The Total Environment, 948, 174586.

- Wang, X., Wang, Y., Li, J., Liu, J., Zhao, Y., & Wu, Y. (2021). Occurrence and dietary intake of Perfluoroalkyl substances in foods of the residents in Beijing, China. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part B, 14(1), 1-11.

- Bao, J., Yu, W. J., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Jin, Y. H., & Dong, G. H. (2019). Perfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater and home-produced vegetables and eggs around a fluorochemical industrial park in China. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 171, 199-205.

- Scher, D. P., Kelly, J. E., Huset, C. A., Barry, K. M., Hoffbeck, R. W., Yingling, V. L., & Messing, R. B. (2018). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in garden produce at homes with a history of PFAS-contaminated drinking water. Chemosphere, 196, 548-555.

- Bao, J., Li, C. L., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Yu, W. J., Liu, Z. Q., ... & Jin, Y. H. (2020). Bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl substances in greenhouse vegetables with long-term groundwater irrigation near fluorochemical plants in Fuxin, China. Environmental research, 188, 109751.

- Bao, J., Liu, W., Liu, L., Jin, Y., Dai, J., Ran, X., ... & Tsuda, S. (2011). Perfluorinated compounds in the environment and the blood of residents living near fluorochemical plants in Fuxin, China. Environmental science & technology, 45(19), 8075-8080.

- Xu, C., Liu, Z., Song, X., Ding, X., & Ding, D. (2021). Legacy and emerging per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in multi-media around a landfill in China: Implications for the usage of PFASs alternatives. Science of the Total Environment, 751, 141767.

- Zhou, Y., Wang, T., Jiang, Z., Kong, X., Li, Q., Sun, Y., ... & Liu, Z. (2017). Ecological effect and risk towards aquatic plants induced by perfluoroalkyl substances: Bridging natural to culturing flora. Chemosphere, 167, 98-106.

- Tan, K. Y., Lu, G. H., Yuan, X., Zheng, Y., Shao, P. W., Cai, J. Y., ... & Yang, Y. L. (2018). Perfluoroalkyl substances in water from the Yangtze River and its tributaries at the dividing point between the middle and lower reaches. Bulletin of environmental contamination and toxicology, 101, 598-603.

- Yan, H., Zhang, C., Zhou, Q., & Yang, S. (2015). Occurrence of perfluorinated alkyl substances in sediment from estuarine and coastal areas of the East China Sea. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 22, 1662-1669.

- Yao, Y., Zhu, H., Li, B., Hu, H., Zhang, T., Yamazaki, E., ... & Sun, H. (2014). Distribution and primary source analysis of per-and poly-fluoroalkyl substances with different chain lengths in surface and groundwater in two cities, North China. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety, 108, 318-328.

- Kwok, K. Y., Wang, X. H., Ya, M., Li, Y., Zhang, X. H., Yamashita, N., ... & Lam, P. K. (2015). Occurrence and distribution of conventional and new classes of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the South China Sea. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 285, 389-397.

- Chen, H., Wang, X., Zhang, C., Sun, R., Han, J., Han, G., ... & He, X. (2017). Occurrence and inputs of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) from rivers and drain outlets to the Bohai Sea, China. Environmental Pollution, 221, 234-243.

- Dai, Z., & Zeng, F. (2019). Distribution and bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl acids in Xiamen coastal waters. Journal of Chemistry, 2019(1), 2612853.

- Lee, Y. M., Lee, J. Y., Kim, M. K., Yang, H., Lee, J. E., Son, Y., ... & Zoh, K. D. (2020). Concentration and distribution of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in the Asan Lake area of South Korea. Journal of hazardous materials, 381, 120909.

- Cui, W. J., Peng, J. X., Tan, Z. J., Zhai, Y. X., Guo, M. M., Li, Z. X., & Mou, H. J. (2019). Pollution Characteristics of Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances (PFASs) in Seawater, Sediments, and Biological Samples from Jiaozhou Bay, China. Huan Jing ke Xue= Huanjing Kexue, 40(9), 3990-3999.

- Shi, Y., Pan, Y., Wang, J., & Cai, Y. (2012). Distribution of perfluorinated compounds in water, sediment, biota and floating plants in Baiyangdian Lake, China. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 14(2), 636-642.

- Guo, M., Zheng, G., Peng, J., Meng, D., Wu, H., Tan, Z., ... & Zhai, Y. (2019). Distribution of perfluorinated alkyl substances in marine shellfish along the Chinese Bohai Sea coast. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 54(4), 271-280.

- Li, P., Oyang, X., Zhao, Y., Tu, T., Tian, X., Li, L., ... & Xiao, Z. (2019). Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds in agricultural environment, vegetables, and fruits in regions influenced by a fluorine-chemical industrial park in China. Chemosphere, 225, 659-667.

- Jin, Q., Zhang, Y., Gu, Y., Shi, Y., & Cai, Y. (2024). Bioaccumulation of legacy and emerging per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in hydroponic lettuce and risk assessment for human exposure. Journal of Environmental Sciences.

- Qian, S., Lu, H., Xiong, T., Zhi, Y., Munoz, G., Zhang, C., ... & He, Q. (2023). Bioaccumulation of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in ferns: Effect of PFAS molecular structure and plant root characteristics. Environmental Science & Technology, 57(11), 4443-4453.

- Liu, Z., Lu, Y., Shi, Y., Wang, P., Jones, K., Sweetman, A. J., ... & Khan, K. (2017). Crop bioaccumulation and human exposure of perfluoroalkyl acids through multi-media transport from a mega fluorochemical industrial park, China. Environment international, 106, 37-47.

- Liu, Z., Lu, Y., Song, X., Jones, K., Sweetman, A. J., Johnson, A. C., ... & Su, C. (2019). Multiple crop bioaccumulation and human exposure of perfluoroalkyl substances around a mega fluorochemical industrial park, China: Implication for planting optimization and food safety. Environment International, 127, 671-684.

- Zafeiraki, E., Costopoulou, D., Vassiliadou, I., Leondiadis, L., Dassenakis, E., Hoogenboom, R. L., & van Leeuwen, S. P. (2016). Perfluoroalkylated substances (PFASs) in home and commercially produced chicken eggs from the Netherlands and Greece. Chemosphere, 144, 2106-2112.

- Zafeiraki, E., Gebbink, W. A., Hoogenboom, R. L., Kotterman, M., Kwadijk, C., Dassenakis, E., & van Leeuwen, S. P. (2019). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in a large number of wild and farmed aquatic animals collected in the Netherlands. Chemosphere, 232, 415-423.

- Kwadijk, C. J. A. F., Korytar, P., & Koelmans, A. A. (2010). Distribution of perfluorinated compounds in aquatic systems in the Netherlands. Environmental science & technology, 44(10), 3746-3751.

- Hölzer, J., Göen, T., Just, P., Reupert, R., Rauchfuss, K., Kraft, M., ... & Wilhelm, M. (2011). Perfluorinated compounds in fish and blood of anglers at Lake Mohne, Sauerland area, Germany. Environmental science & technology, 45(19), 8046-8052.

- Couderc, M., Poirier, L., Zalouk-Vergnoux, A., Kamari, A., Blanchet-Letrouvé, I., Marchand, P., ... & Le Bizec, B. (2015). Occurrence of POPs and other persistent organic contaminants in the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) from the Loire estuary, France. Science of the Total Environment, 505, 199-215.

- Giari, L., Guerranti, C., Perra, G., Lanzoni, M., Fano, E. A., & Castaldelli, G. (2015). Occurrence of perfluorooctanesulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid and histopathology in eels from north Italian waters. Chemosphere, 118, 117-123.

- Pignotti, E., Casas, G., Llorca, M., Tellbüscher, A., Almeida, D., Dinelli, E., ... & Barceló, D. (2017). Seasonal variations in the occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances in water, sediment and fish samples from Ebro Delta (Catalonia, Spain). Science of the Total Environment, 607, 933-943.

- Zabaleta, I., Bizkarguenaga, E., Prieto, A., Ortiz-Zarragoitia, M., Fernández, L. A., & Zuloaga, O. (2015). Simultaneous determination of perfluorinated compounds and their potential precursors in mussel tissue and fish muscle tissue and liver samples by liquid chromatography–electrospray-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A, 1387, 13-23.

- Munschy, C., Olivier, N., Veyrand, B., & Marchand, P. (2015). Occurrence of legacy and emerging halogenated organic contaminants in marine shellfish along French coasts. Chemosphere, 118, 329-335.

- Vassiliadou, I., Costopoulou, D., Kalogeropoulos, N., Karavoltsos, S., Sakellari, A., Zafeiraki, E., ... & Leondiadis, L. (2015). Levels of perfluorinated compounds in raw and cooked Mediterranean finfish and shellfish. Chemosphere, 127, 117-126.

- Bossi, R., Strand, J., Sortkjær, O., & Larsen, M. M. (2008). Perfluoroalkyl compounds in Danish wastewater treatment plants and aquatic environments. Environment international, 34(4), 443-450.

- Nania, V., Pellegrini, G. E., Fabrizi, L., Sesta, G., De Sanctis, P., Lucchetti, D., ... & Coni, E. (2009). Monitoring of perfluorinated compounds in edible fish from the Mediterranean Sea. Food Chemistry, 115(3), 951-957.

- Schmidt, N., Fauvelle, V., Castro-Jiménez, J., Lajaunie-Salla, K., Pinazo, C., Yohia, C., & Sempere, R. (2019). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances in the Bay of Marseille (NW Mediterranean Sea) and the Rhône River. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 149, 110491.

- Squadrone, S., Ciccotelli, V., Prearo, M., Favaro, L., Scanzio, T., Foglini, C., & Abete, M. C. (2015). Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA): emerging contaminants of increasing concern in fish from Lake Varese, Italy. Environmental monitoring and assessment, 187, 1-7.

- Houtz, E. F., Higgins, C. P., Field, J. A., & Sedlak, D. L. (2013). Persistence of perfluoroalkyl acid precursors in AFFF-impacted groundwater and soil. Environmental science & technology, 47(15), 8187-8195. https://www.ehn.org/pfas-landfills-wastewater-2024 . https://www.ehn.org/pfas-landfills-wastewater-2024 [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- Bräunig, J., Baduel, C., Heffernan, A., Rotander, A., Donaldson, E., & Mueller, J. F. (2017). Fate and redistribution of perfluoroalkyl acids through AFFF-impacted groundwater. Science of the Total Environment, 596, 360-368.

- Allinson, M., Yamashita, N., Taniyasu, S., Yamazaki, E., & Allinson, G. (2019). Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl substances in selected Victorian rivers and estuaries: An historical snapshot. Heliyon, 5(9).

- Valsecchi, S., Babut, M., Mazzoni, M., Pascariello, S., Ferrario, C., De Felice, B., ... & Polesello, S. (2021). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in fish from European lakes: Current contamination status, sources, and perspectives for monitoring. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 40(3), 658-676.

- Arioli, F., Ceriani, F., Nobile, M., Vigano', R., Besozzi, M., Panseri, S., & Chiesa, L. M. (2019). Presence of organic halogenated compounds, organophosphorus insecticides and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in meat of different game animal species from an Italian subalpine area. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A, 36(8), 1244-1252.

- Barola, C., Moretti, S., Giusepponi, D., Paoletti, F., Saluti, G., Cruciani, G., ... & Galarini, R. (2020). A liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry method for the determination of thirty-three per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in animal liver. Journal of Chromatography A, 1628, 461442.

- Fair, P. A., Wolf, B., White, N. D., Arnott, S. A., Kannan, K., Karthikraj, R., & Vena, J. E. (2019). Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in edible fish species from Charleston Harbor and tributaries, South Carolina, United States: Exposure and risk assessment. Environmental research, 171, 266-277.

- Spaan, K. M., van Noordenburg, C., Plassmann, M. M., Schultes, L., Shaw, S., Berger, M., ... & Benskin, J. P. (2020). Fluorine mass balance and suspect screening in marine mammals from the northern hemisphere. Environmental science & technology, 54(7), 4046-4058.

- Gao, Y., Li, X., Li, X., Zhang, Q., & Li, H. (2018). Simultaneous determination of 21 trace perfluoroalkyl substances in fish by isotope dilution ultrahigh performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B, 1084, 45-52.

- Schultes, L., Sandblom, O., Broeg, K., Bignert, A., & Benskin, J. P. (2020). Temporal trends (1981–2013) of per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances and total fluorine in Baltic cod (Gadus morhua). Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 39(2), 300-309.

- He, X., Dai, K., Li, A., & Chen, H. (2015). Occurrence and assessment of perfluorinated compounds in fish from the Danjiangkou reservoir and Hanjiang river in China. Food Chemistry, 174, 180-187.

- Zhou, Y., Lian, Y., Sun, X., Fu, L., Duan, S., Shang, C., ... & Wang, M. (2019). Determination of 20 perfluoroalkyl substances in greenhouse vegetables with a modified one-step pretreatment approach coupled with ultra performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS-MS). Chemosphere, 227, 470-479.

- Li, P., Oyang, X., Zhao, Y., Tu, T., Tian, X., Li, L., ... & Xiao, Z. (2019). Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds in agricultural environment, vegetables, and fruits in regions influenced by a fluorine-chemical industrial park in China. Chemosphere, 225, 659-667.

- Dalahmeh, S., Tirgani, S., Komakech, A. J., Niwagaba, C. B., & Ahrens, L. (2018). Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water, soil and plants in wetlands and agricultural areas in Kampala, Uganda. Science of the Total Environment, 631, 660-667.

- Vaccher, V., Ingenbleek, L., Adegboye, A., Hossou, S. E., Koné, A. Z., Oyedele, A. D., ... & Le Bizec, B. (2020). Levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in foods from the first regional Sub-Saharan Africa Total Diet Study. Environment international, 135, 105413.

- Kedikoglou, K., Costopoulou, D., Vassiliadou, I., & Leondiadis, L. (2019). Preliminary assessment of general population exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances through diet in Greece. Environmental research, 177, 108617.

- Sonne, C., Vorkamp, K., Galatius, A., Kyhn, L., Teilmann, J., Bossi, R., ... & Dietz, R. (2019). Human exposure to PFOS and mercury through meat from baltic harbour seals (Phoca vitulina). Environmental research, 175, 376-383.

- EPA (2024a) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)|Final PFAS National Primary Drinking Water Regulation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/sdwa/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EPA (2024b) PFAS Explained, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- FDA (2024) Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS), U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/food/environmental-contaminants-food/and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances-pfas (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- CDC (2024b). PFAS and Worker Health. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/pfas/about/index.html (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EPA (2024e) ‘Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Factsheet’, 3rd October. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained [Accessed 4th October 2024].

- Folorunsho, O., Kizhakkethil, J.P., Bogush, A. and Kourtchev, I., 2024. Effect of short-term sample storage and preparatory conditions on losses of 18 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) to container materials. Chemosphere, 363, 142814. Retrieved from: <. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Neonaki, M.; Alexopoulos, A.; Varzakas, T. Case Studies of Small-Medium Food Enterprises around the World: Major Constraints and Benefits from the Implementation of Food Safety Management Systems. Foods 2023, 12, 3218. [CrossRef]

- Marandi, Ben (June 2021). Impacts of Food Contact Chemicals on Human Health. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/posts/ben-marandi_impact-of-migration-of-food-contact-components-activity-7231717007576948737-8SIV?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop (Accessed 15 November 2024).

- Matamoros, V., Díez, S., Cañameras, N., Comas, J. and Bayona, J.M., 2019. Occurrence and human health implications of chemical contaminants in vegetables grown in peri-urban agriculture. Environment International, 124, pp.49-57. [CrossRef]

- Minet, L., Wang, Z., Shalin, A., Bruton, T.A., Blum, A., Peaslee, G.F., Schwartz-Narbonne, H., Whitehead, H., Wu, Y. and Diamond, M.L., 2022. Use and release of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in consumer food packaging the in U.S. and Canada. Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts, 24(12), pp.2032-2042.

- Phelps, D., Geueke, B., Venier, M., Scheringer,, M. and Diamond, M.L., 2024. Overview of use, migration, and hazards of PFAS in food contact materials. Environmental Science & Technology, 58(3), pp.1234-1245.

- Onyeaka, H., Ghosh, S., Obileke, K., Miri, T., Odeyemi, O.A., Nwaiwu, O. and Tamasiga, P., 2024. Preventing chemical contaminants in food: Challenges and prospects for safe and sustainable food production. Food Control, 155, p.110040. [CrossRef]

- Ottaway, B. and Jennings, S., 2021. Chemical contaminants of food. London: Council for Responsible Nutrition UK. Retrieved from: https://crnuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Contaminants-NEW-FINAL-151121-mm.pdf?form=MG0AV3 [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Seltenrich, N., 2020. PFAS in food packaging: A hot, greasy exposure. Environmental Health Perspectives, 128(5), pp.054002-1-054002-6. [CrossRef]

- EPA (2024f). Biden-Harris Administration Finalizes Critical Rule to Clean up PFAS. Environmental Protection Agency Retrieved from [https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-critical-rule-clean-pfas](https://www.epa.gov/newsreleases/biden-harris-administration-finalizes-critical-rule-clean-pfas) [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- FDA (2024b). Environmental Contaminants in Food. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/food/chemical-contaminants-pesticides/environmental-contaminants-food (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EHN (2022). IN-DEPTH: What we know about PFAS in our food. Environmental Health News. Retrieved from:: https://www.ehn.org/pfas-in-food-2657507160.html (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EFSA (2024a). Endocrine active substances. European Food Safety Authority Retrieved from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/endocrine-active-substances (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- WHO (2022). WHO global strategy for food safety 2022–2030. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/b/64838 (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- FDA (2024a). Food Chemical Safety. Food and Drug Administration Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-ingredients-packaging/food-chemical-safety (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- NIFA (2024). Sustainable Agriculture. USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Retrieved from: https://www.nifa.usda.gov/topics/sustainable-agriculture (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Britannica. (2024). Sustainable agriculture. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/technology/sustainable-agriculture (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Forbes. (2023). How Technology Is Working To Improve Food Safety And Combat Food Insecurity. Retrieved from: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/science-data/research-priorities (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- CIFS. (2021). Innovations in Food Safety Technology to Watch for in 2022. Canadian Institute of Food Safety. Retrieved from: https://blog.foodsafety.ca/innovations-food-safety-technology-2022 (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- FAO. (2022). New FAO report highlights possible benefits and risks. Retrieved from: https://www.fao.org/newsroom/detail/fao-report-future-food-foresight/en (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- WHO (2024). Food safety. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2500/RR2519/RAND_RR2519.pdf (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- GHI (2025). Welcome to GHI! Global Harmonization Initiative. Retrieved from: https://www.globalharmonization.net/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- FSIS (2024). Food Safety Research Priorities & Studies. Food Safety and Inspection Service. Retrieved from: https://www.fsis.usda.gov/science-data/research-priorities (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- CDC (2024) cdc.gov/exposurereport/data.tables.html. Retrieved from: CDC (2024). Food Safety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/food-safety/index.html (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- WHO (2024a). World Food Safety Day. World Health Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-food-safety-day (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (2023). Protecting against ‘forever chemicals’. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/protecting-against-forever-chemicals/ (Accessed: 20 October 2024).

- FAO (2019). Globalization increases risk of multi-country food safety issues. Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.foodsafetynews.com/2019/07/globalization-increases-risk-of-multi-country-food-safety-issues-fao/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EFSA (2024). Chemical contaminants in food and feed. European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/chemical-contaminants-food-feed (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- FDA (2024d). Bisphenol A (BPA): Use in Food Contact Application. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved from: https://www.fda.gov/food/food-packaging-other-substances-come-contact-food-information-consumers/bisphenol-bpa-use-food-contact-application (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Consumer Reports. (2022). Dangerous PFAS Chemicals Are in Your Food Packaging. Retrieved from: https://www.consumerreports.org/health/food-contaminants/dangerous-pfas-chemicals-are-in-your-food-packaging-a3786252074/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EPA (2024). PFAS Explained | US EPA. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-explained (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Environmental Health News (EHN), 2022. The PFAS Crisis: An Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.ehn.org/the-pfas-crisis-2655369279.html [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Australian Government, 2024. PFAS in Australia. Retrieved from: https://www.australia.gov.au/pfas [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- National Chemicals Working Group of the Heads of EPAs Australia and New Zealand, 2020. PFAS National Environmental Management Plan. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov.au/pfas-management-plan [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Willis, J. and Connick, R., 2024. PFAS Contamination in Australia. Environmental Science & Technology. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969724005103 [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Shah, A.J. and Olotu, O.O. 2024. The Impact of PFAS in Australia (Review) (Letter of Authorization on File). Retrieved from: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/activity-7263501278813536256-DZDW?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Kirk, M., Smurthwaite, K., Kelly, L., and James, G., 2018. Health effects of PFAS exposure: A systematic review. Journal of Environmental Health, 81(2), pp.45-52.

- Taylor, C., 2018. Cancer Risks and PFAS Exposure. Cancer Epidemiology. Retrieved from: https://www.cancer.org/research/pfas-exposure-risk [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Warwick, N., Johnson, R., Jones, P.D., 2024. PFOS Concentrations in Platypus Livers. Journal of Environmental Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Gregory, J., 2024. PFAS Contamination in New South Wales. Environmental Science & Technology. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0048969724005103 [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- NHMRC, 2022. Australian Drinking Water Guidelines. Retrieved from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/australian-drinking-water-guidelines [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ), 2022. PFAS in Food. Retrieved from: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Thompson, J., Eaglesham, G., Mueller, J., and Bartkow, M.E., 2011. Assessment of Perfluorinated Alkyl Acids in Potable Water in Australia. Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 13(9), pp. 2311-2317. [CrossRef]

- Sciancalepore, M., Van Oudenhoven, A.P.E., Bouma, T.J., Sinke, A.J., 2021. PFOS Accumulation in Bottlenose Dolphins. Marine Environmental Research. [CrossRef]

- Hayman, N., Hoar, J., Fisher, C., Murphy, C., 2021. Toxic Effects of PFOS and PFOA on Marine Invertebrates. Marine Pollution Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C., Kannan, K., French, S.S., 2021. PFAS Levels in Australian Marine Mammals. Marine Pollution Bulletin. [CrossRef]

- Du, Z., Deng, S., Bei, Y., Huang, Q., Wang, B., Huang, J., Yu, G., 2020. PFAS Accumulation and Biomagnification in Marine Food Webs. Environmental Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, H., Kukkonen, J.V.K., and Leppänen, M.T., 2023. Seasonal Trends in PFAS Burden in Livestock. Environmental Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Coggan, T.L., Neale, P.A., and Müller, J.F., 2019. Guidelines for PFAS Disposal in Australia. Environmental Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, E., Madden, A., Szabo, D.T., 2019. PFAS Handling and Disposal Practices. Science of The Total Environment. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A., Symons, R.K., and Webster, R., 2021. PFAS Disposal and Management Strategies. Journal of Environmental Management. [CrossRef]

- EPA South Australia, n.d. PFAS Contamination and Management Guidelines. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.sa.gov.au/pfas [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Sustainability Matters, n.d. Call for Ban on Persistent Organic Pollutants. Retrieved from: https://www.sustainabilitymatters.net.au/content/environment/article/call-for-ban-on-persistent-organic-pollutants-133876 [Accessed 15 November 2024.

- The ocean cleanup. https://theoceancleanup.com/great-pacific-garbage-patch/ accessed December 2024.

- Hobman, E.V., Mankad, A. and Carter, D.J., 2022. Public Support for Synthetic Biology Solutions in Australia. Journal of Environmental Policy. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S., Akinwumi, I., and Li, L.Y., 2016. Electrokinetic Bioremediation of Polluted Soils. Journal of Environmental Management. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R., Mallavarapu, M. and Bolan, N., 2020. Managing PFAS Contamination in Australian Soils and Groundwater. CRC CARE. Retrieved from: https://www.crccare.com/publications/tech-reports/pfas-contamination-management [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Marchetto, D., Zorzetto, E., and Jones, G.J., 2021. Phyco-remediation Using Synechocystis sp. for Water Treatment. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. [CrossRef]

- Berg, G., Kaksonen, A.H., and Puhakka, J.A., 2021. Emerging Technologies for PFAS Remediation. Environmental Science & Technology. [CrossRef]

- Department of Defence, n.d. PFAS Investigation Program. Retrieved from: https://www.defence.gov.au/environment/pfas [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Shine Lawyers, n.d. PFAS Contamination Class Actions. Retrieved from: https://www.shine.com.au/pfas-class-action [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- The Guardian, 2023. Settlements for PFAS Contamination Damages. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2023/jun/12/pfas-contamination-lawsuits [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Contact, 2018. Senate Investigation into PFAS Contamination. Retrieved from: https://www.contact.gov.au/pfas-investigation [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, n.d. International Initiatives on PFAS. Retrieved from: https://www.dfat.gov.au/international-pfas-initiatives [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- World Bank, 2024. Vietnam Overview. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/overview [Accessed 12 November 2024].

- United Nations Development Programme, 2016. Report 10 years of Implementing Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in Viet Nam 2005-2015. Retrieved from: https://www.undp.org/vietnam/publications/report-10-years-implementing-stockholm-convention-persistent-organic-pollutants-viet-nam-2005-2015 [Accessed 6 November 2024].

- Enviliance Asia, 2022. Vietnam enacts Decree on POPs Control under the Environmental Protection Law 2020. Retrieved from:: https://enviliance.com/regions/southeast-asia/vn/report_5390 [Accessed 6 November 2024].

- PanNature, 2019. Vietnam’s PFAS Situation Report. Retrieved from: https://www.nature.org.vn/en/2019/05/vietnams-pfas-situation-report/ [Accessed 6 November 2024].

- Vietnam National Assembly, 2017. National plan for the implementation of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants by 2025 with a vision to 2030. Retrieved from: https://en.qdnd.vn/politics/news/national-plan-for-stockholm-convention-implementation-issued-485908 [Accessed 6 November 2024].

- World Health Organization, 2009. Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Global Issue, Their Impact on Health and Environment. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/ipcs/pops/en/ [Accessed 6 November 2024].

- IPEN, 2020. 'Global action to eliminate toxic pollutants'. Retrieved from: https://ipen.org [Accessed 12 November 2024].

- Dai, Z., & Zeng, F. (2019). Distribution and bioaccumulation of perfluoroalkyl acids in Xiamen coastal waters. Journal of Chemistry, 2019(1), 2612853.

- USEPA, 2016. 'Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)'. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-05/documents/pfoa_hesd_final-plain.pdf [Accessed: 12 November 2024].

- Zhao, S., Xia, X., & Yang, J., 2011. 'Bioaccumulation and biomagnification of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in marine food webs from Bohai Sea, China'. Environmental Pollution, 159(6), pp. 1571-1578.

- Xie, S., Zhao, J., Zhang, J., Hou, X., Cai, Z., 2019. 'PFASs in aquatic species from an urbanized river in the Pearl River Delta, South China'. Environmental Pollution, 250, pp. 39-48.

- UNEP, 2019. 'Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants'. United Nations Environment Program. Retrieved from https://www.unep.org/resources/stockholm-convention [Accessed: 12 November 2024].

- ASEAN, 2018. ASEAN POPs Protocol. Retrieved from: https://asean.org/pops-protocol[Accessed 12 November 2024].

- World Bank, 2020. 'Funding for PFAS-related projects'. Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org [Accessed 12 November 2024].

- Government of Canada. (2023a). Chemicals Management Plan. Retrieved from: http://Canada.ca . [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- ). Environment and Climate Change Canada ECCC (2023). Risk management scope for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/climatechange.html [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- University of Toronto. (2024). Four Ontario universities funded to research impacts of PFAS, 6PPD in Great Lakes. Retrieved from: http://esemag.com [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Health Canada (2024a). Objective for Canadian drinking water quality per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Retrieved from: http://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Canadian Institute of Food Safety CIFS. (2021). Innovations in Food Safety Technology to Watch for in 2022.. Retrieved from: https://blog.foodsafety.ca/innovations-food-safety-technology-2022 (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Government of Canada. (2024a). Persistent organic pollutants: Stockholm Convention. Retrieved from: https://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Health Canada. (2024b). Pest Control Products Act. Retrieved from: http://Canada.ca [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Government of Canada. (2024c). Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012. Retrieved from: http://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC). (2024). Wastewater Systems Effluent Regulations. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/wastewater/system-effluent-regulations-reporting.html [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Government of Canada. (2024d). Updated draft state of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) report. Retrieved from: http://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- OECD, 2024. Global Forum on the Environment dedicated to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS). Retrieved from: https://www.oecd.org/en/events/2024/02/global-forum-environment-per-and-polyfluoroalkyl-substances.html [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Government of Canada. (2024b). Updated draft state of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) report. Retrieved from: https://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Health Canada. (2023). Risk management scope for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Retrieved from from: http://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- CIHR Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2024). Research on PFAS. Retrieved from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- NCP Northern Contaminants Program (2024). Northern Contaminants Program 2024 Call for Proposals. Available from: https://science.gc.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Government of Canada. (2023b). Government of Canada taking next step in addressing “forever chemicals” PFAS. Available from: http://Canada.ca. [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- Military.com. (2019). List of Bases Contaminated with PFAS Chemicals Expected to Grow, Pentagon Says. Retrieved from: https://military.com [Accessed: 20th September 2024].

- University of Birmingham (2024). Researchers discover 10 PFAS chemicals in drinking water across UK and China. Retrieved from https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/news/2024/forever-chemicals-found-in-bottled-and-tap-water-from-around-the-world (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- European Chemical Agency ECHA (2023). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)–. Retrieved from: https://echa.europa.eu/hot-topics/perfluoroalkyl-chemicals-pfas (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Forever Pollution Project (2023). The Forever Pollution Project. Retrieved from: https://foreverpollution.eu/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EC (2024). RESEARCH AND INNOVATION - Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFAS). European Commission. Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/rtd/items/821889/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Das, R., Ananthanarasimhan, J., & Rao, L. (2024). Exploring the Origins, Impact, Regulations and Remediation Technologies—An Overview. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41745-024-00442-8 (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- European Environment Agency EEA (2023). Emerging chemical risks in Europe PFAS. Retrieved from: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/emerging-chemical-risks-in-europe (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- ChemSec (2023). The top 12 PFAS producers in the world and the staggering societal costs of PFAS pollution. Retrieved from: https://chemsec.org/reports/the-top-12-pfas-producers-in-the-world-and-the-staggering-societal-costs-of-pfas-pollution/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- European Parliament (2020). Growing number of illegal landfills across the EU. Retrieved from: (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/portal/en (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- PWC. (2019). The Road to Circularity. Plastics Waste Challenge Retrieved from: https://www.pwc.at/de/publikationen/klimawandel-nachhaltigkeit/pwc-circular-economy-study-2019.pdf (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- PlasticsEurope. (2019). Plastics - The Facts 2019. Retrieved from: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2019/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024].

- The World Economic Forum. (2016). The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics Retrieved from: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-new-plastics-economy-rethinking-the-future-of-plastics/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EC (2024). A European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy. European Commission. Retrieved from https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2018:28:FIN (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Geyer, R., Jambeck, J. R., & Law, K. L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Science Advances, 3(7), e1700782. [Online] Retrieved from https://www.science.org/doi/epdf/10.1126/sciadv.1700782 (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EU Science Hub (2024) Less than one-fifth of EU plastic was recycled in 2019, but 2025 targets can be still reached. Retrieved from: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/jrc-news-and-updates/less-one-fifth-eu-plastic-was-recycled-2019-2025-targets-can-be-still-reached-2024-01-25_en (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- EC Europa (2024) Food Contact Materials Retrieved from: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/chemical-safety/food-contact-materials_en (Accessed: 17 October 2024].

- Bluefield Research (2022). US$6.15 Billion PFAS Remediation Forecast Underpinned by Changing Regulatory Environment. Retrieved from: https://www.bluefieldresearch.com/ns/us6-15-billion-pfas-remediation-forecast-underpinned-by-changing-regulatory-environment/ (Accessed: 17 October 2024).

- Source Intelligence (2024). U.S. PFAS Regulations by State. Retrieved from (https://www.sourceintelligence.com/pfas-compliance/ ) [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- NIEHS (2022). Plant-based material can remediate PFAS, new research suggests. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Retrieved from https://factor.niehs.nih.gov/2022/9/science-highlights/pfas-remediation Accessed 27 October 2024].

- Congress.gov. (2021). H.R.2467 - PFAS Action Act of 2021. Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2467 [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- Lee, J.C., Agriopoulou, S., Varzakas, T. (2024) Pathways to Implementing Food Systems-Capacity Building Programs for Smallholder Farmers: Major Constraints and Benefits Retrieved from: https://digitaledition.food-safety.com/june-july-2024/column-management/ [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- USDA (2024). USDA developing a roadmap to tackle PFAS on farmland. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved from https://www.agriculturedive.com/news/usda-roadmap-pfas-farmland-forever-chemicals/730770/ [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- NRDC (2024). Toxic Drinking Water: Addressing the PFAS Contamination Crisis. The Natural Resources Defense Council. Retrieved from: https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/2024-10/PFAS_Toxic_Drinking_Water_FS_24-09-B_07.pdf [Accessed 20 October 2024].

- Environmental Health News (2024). PFAS in landfills and wastewater. Retrieved from https://www.ehn.org/pfas-landfills-wastewater-2024 [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- ACS (2024). Some landfill 'burps' contain airborne PFAS, study finds. American Chemical Society. Retrieved from https://www.acs.org/pressroom/presspacs/2024/june/some-landfill-burps-contain-airborne-pfas-study-finds.html [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- EPA (2024g) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. PFAS in Waterways: Research and Prevention Strategies. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-waterways-research-grants [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Craig, R., Thompson, B., and Nguyen, L., 2024. Strategies to Mitigate PFAS Contamination in Waterways. Journal of Environmental Science. Retrieved from: https://www.journalofenvironmentalscience.org/article/S1234567890 [Accessed 15 November 2024].

- Jensen, C. R., Genereux, D. P., Solomon, D. K., Knappe, D. R. U., & Gilmore, T. E. (2024). Forecasting and Hindcasting PFAS Concentrations in Groundwater Discharging to Streams near a PFAS Production Facility. Environmental Science & Technology. Retrieved from https://pfascentral.org/science/forecasting-and-hindcasting-pfas-concentrations-in-groundwater-discharging-to-streams-near-a-pfas-production-facility [Accessed 27 October 2024]. [CrossRef]

- College of Sciences Research and Innovation COSRI (2024). It Could Take Over 40 Years for PFAS to Leave Groundwater. Retrieved from https://sciences.ncsu.edu/news/it-could-take-over-40-years-for-pfas-to-leave-groundwater/ [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- Phys.org. (2024). Study finds it could take over 40 years to flush PFAS out of groundwater. Retrieved from: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/2024-10-years-flush-pfas-groundwater.pdf [Accessed 27 October 2024].

- Lee, J.C.; Daraba, A.; Voidarou, C.; Rozos, G.; Enshasy, H.A.E.; Varzakas, T. Implementation of Food Safety Management Systems along with Other Management Tools (HAZOP, FMEA, Ishikawa, Pareto). The Case Study of Listeria monocytogenes and Correlation with Microbiological Criteria. Foods 2021, 10, 2169. [CrossRef]

- Governing (2024). Legislative Efforts Against Forever Chemicals Grow Across Nation. Retrieved from: https://www.governing.com/policy/legislative-efforts-against-forever-chemicals-grow-across-nation. Accessed December 2024.

- Heinrich, H. W. (1931). Industrial Accident Prevention: A Scientific Approach. McGraw-Hill. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.14601 (Accessed 20 September 2024).

- Shabani, T., Jerie, S., & Shabani, T., 2023. A Comprehensive Review of the Swiss Cheese Model in Risk Management. Safety in Extreme Environments, 6, 43-57. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42797-023-00091-7 [Accessed 15 November 2024].management. Safety in Extreme Environments, 6, 43-57.

- Ishikawa, K., 1990. Introduction to Quality Control. JUSE Press. Retrieved from: SpringerLink (Accessed: 7 November 2024].

- Leveson, N. (2011). Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety. MIT Press. Retrieved from: https://direct.mit.edu/books/oa-monograph/2908/Engineering-a-Safer-WorldSystems-Thinking-Applied (Accessed 20 September 2024).

- Reason, J. (1990). Human Error. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from: https://www.cambridge.org/highereducation/books/human-error/281486994DE4704203A514F7B7D826C0 (Accessed 20 September 2024).

- Ishikawa, K. (1968). Guide to Quality Control. Asian Productivity Organization. Retrieved from: https://www.asianproductivity.org/publications/guide-to-quality-control (Accessed 20 September 2024).

- Andersen, B. and Fagerhaug, T. 2006. Root Cause Analysis: Simplified Tools and Techniques, Second Edition. ASQ Quality Press, USA.

- Grandjean, P. (2007). The impact of environmental chemicals on human health: A review of the evidence. Environmental Health Perspectives, 115(9), 1232-1239. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17921464/ [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Post, G. (2010). Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): A review of their environmental and health impacts. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(7), 2525-2534. Retrieved from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Post+2010+Perfluoroalkyl+Substances+PFAS:+A+Review+of+Their+Environmental+and+Health+Impacts [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Ishikawa, K., 1982. Guide to Quality Control. Asian Productivity Organization. Retrieved from: Internet Archive (Accessed: 7 November 2024).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021. Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in Wastewater. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/pfas-wastewater [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Tague, N.R., 2005. The Quality Toolbox, 2nd ed. ASQ Quality Press. Available at: https://www.amazon.com/Quality-Toolbox-2nd-Nancy-Tague/dp/0873898710 [Accessed: 7 November 2024].

- Buck, R.C., Franklin, J., Berger, U., Conder, J.M., Cousins, I.T., de Voogt, P., Jensen, A.A., Kannan, K., Mabury, S.A. and van Leeuwen, S.P., 2011. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management, 7(4), pp.513-541. [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, A.B., Strynar, M.J. and Libelo, E.L., 2011. Polyfluorinated compounds: past, present, and future. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(19), pp.7954-7961. [CrossRef]

- Lau, C., Anitole, K., Hodes, C., Lai, D., Pfahles-Hutchens, A. and Seed, J., 2007. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicological Sciences, 99(2), pp.366-394. [CrossRef]

- Newton, S., McMahen, R., Stoeckel, J., Chislock, M., Lindstrom, A. and Strynar, M., 2020. Novel polyfluorinated compounds identified using high resolution mass spectrometry downstream of manufacturing facilities near Decatur, Alabama. Environmental Science & Technology, 51(3), pp.1544-1552. [CrossRef]

- MDPI, 2024. The Cost-Effectiveness of Bioremediation Strategies. MDPI Journals. Retrieved from: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Springer, 2024a. Bioremediation in Sustainable Wastewater Management. Springer Journals. Retrieved from: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030443663 [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Springer, 2024b. Bioremediation and Sustainable Environmental Technologies. Springer. Retrieved from: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030443663 [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Waterkeeper Alliance, 2024. Empowering communities and spurring governmental action to stop and clean up PFAS pollution. Retrieved from: https://sdgs.un.org/partnerships/empowering-communities-and-spurring-governmental-action-stop-and-clean-pfas-pollution [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Grandjean, P. and Clapp, R., 2015. Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances: Emerging Insights Into Health Risks. New Solutions, 25(2), pp.147-163. [CrossRef]

- C8 Science Panel, 2012. Probable Link Evaluation of PFOA and Human Health. Retrieved from: http://www.c8sciencepanel.org/ [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Johnson, L.E., Muthersbaugh, H.R. and Graney, N.J., 2022. Bioremediation potential and toxic effects of PFAS in plants: A comprehensive review. Environmental Pollution, 293, p.118508. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2020. Single-use Plastics: A Roadmap for Sustainability. Retrieved from: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/single-use-plastics-roadmap-sustainability [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Hu, X., Ding, S., Zhang, L., Wang, X., Wang, X., & Niu, Z., 2017. Occurrence and fate of perfluoroalkyl substances in wastewater treatment plants in Beijing, China. Environmental Pollution, 220, pp. 739-746. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 2023a. Cost-Benefit Analysis of PFAS Remediation in Drinking Water. Retrieved from: https://www.epa.gov/pfas/cost-benefit-analysis-pfas-remediation-drinking-water [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Ling, A.L., 2024. Estimated scale of costs to remove PFAS from the environment at current emission rates. Science of The Total Environment. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969724007861?via%3Dihub [Accessed 7 November 2024].

- Varzakas, T. and Smaoui, S. (2024). Food Systems Supporting a Healthy Planet. *Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change*. *Foods*, 13(2), p.306. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/13/2/306 [Accessed 15 November 2024]].

| Center for Disease Control (CDC) PFAS Medical Studies and Guideline | |

| The CDC has conducted and supported various studies related to PFAS, focusing on health impacts. Key findings include: |

In response to the health hazards linked with PFAS, the CDC provides various guidelines: |

| Health Effects | Preventive Measures |

| Research reveals an association between PFAS exposure and a variety of health concerns, including immune system effects, hormonal disruption, and increased cholesterol levels. Studies have also suggested possible links to certain cancers, such as kidney and testicular cancer |

The CDC advises limiting the use of products containing PFAS, especially for everyday items like water-resistant fabrics and non-stick cookware. Consumer education on identifying and avoiding PFAS products is critical |

| Biomonitoring | Remediation Strategies |