Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. NUS and School Selection

2.2. The School Meal Menus

2.3. The Optimizations

3. Results

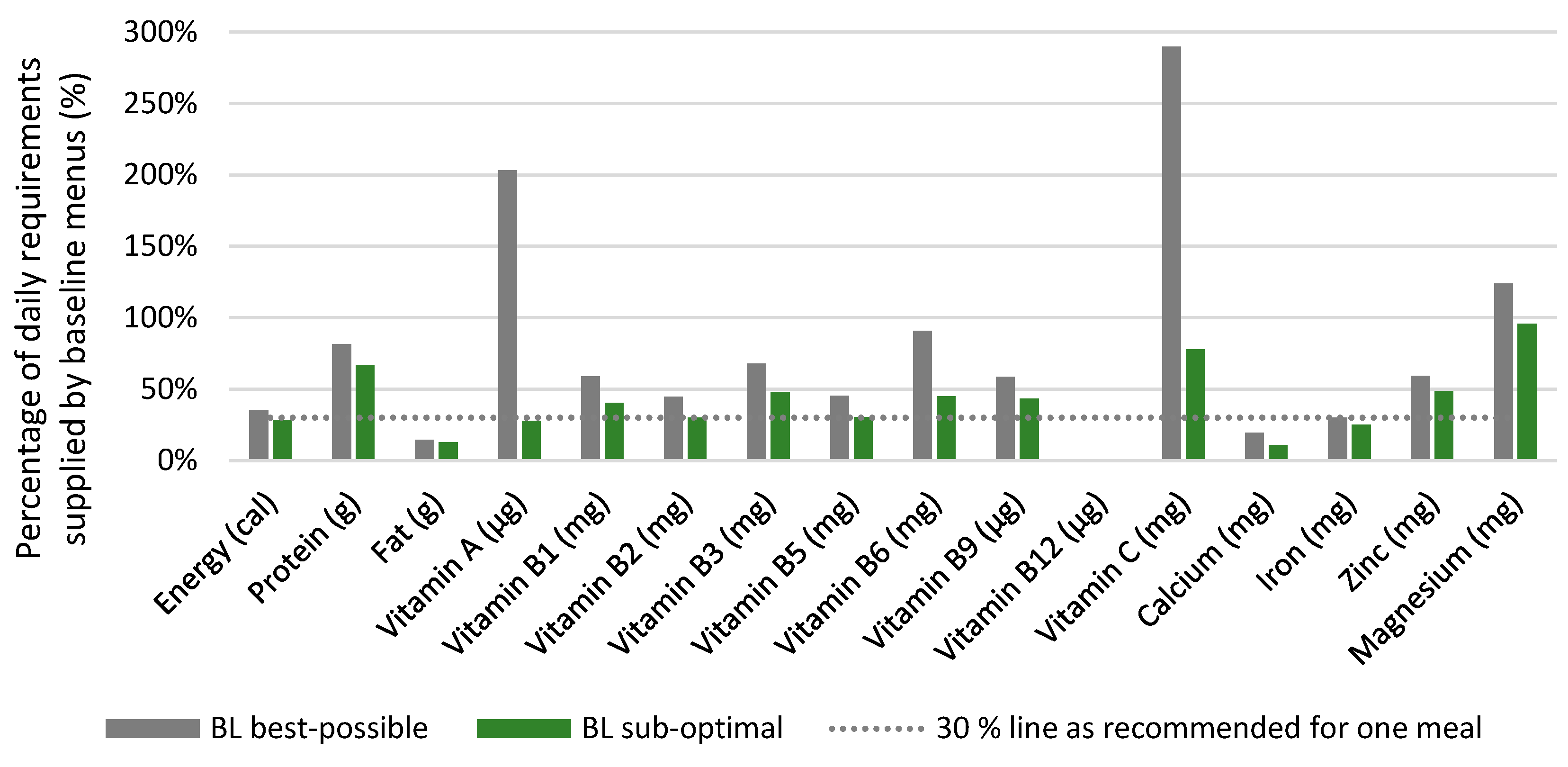

3.1. Nutritional Analysis of the Baseline Menus

3.1.1. The Best-Possible Baseline Menu (BL Best-Possible)

- Monday: White rice (Oryza sativa), green grams (Vigna radiata) (known locally as ndengu), and mixed vegetables;

- Tuesday: Maize meal (ugali) and mixed vegetables;

- Wednesday: White rice, yellow beans (Phaseolus vulgaris), and mixed vegetables;

- Thursday: White rice, green grams, and Irish potatoes (Solanum tuberosum)

- Friday: White rice, yellow beans, and mixed vegetables.

3.1.2. The Sub-Optimal Baseline Menu (BL Sub-Optimal)

- Monday: White rice, green grams (ndengu), and spinach;

- Tuesday: Maize meal (ugali) and spinach;

- Wednesday: White rice, yellow beans, and spinach;

- Thursday: White rice and green grams;

- Friday: White rice, yellow beans, and spinach.

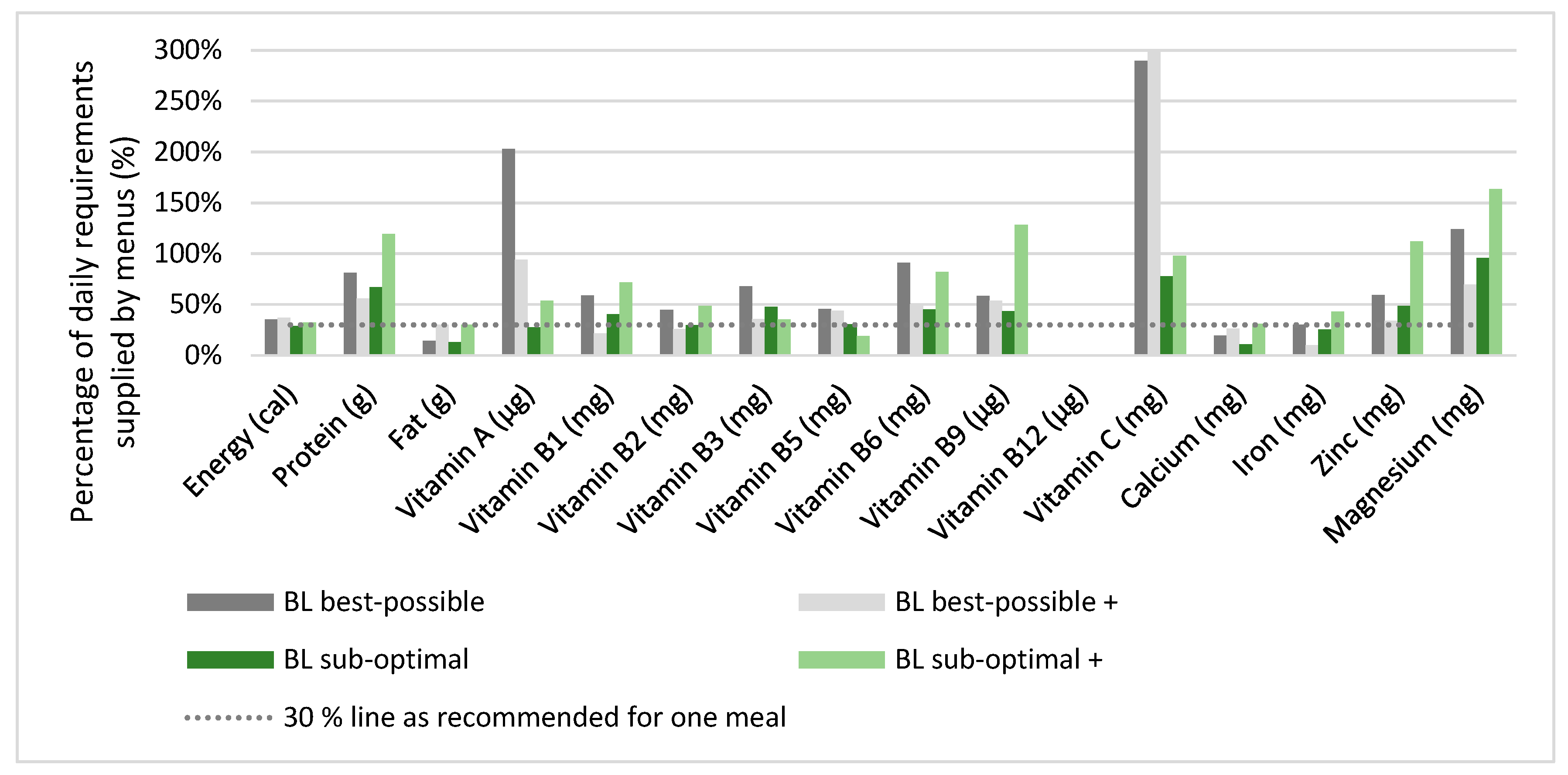

3.2. SMP PLUS Optimizations

3.2.1. First Optimization: Baseline Menu Ingredients in Optimum Quantity

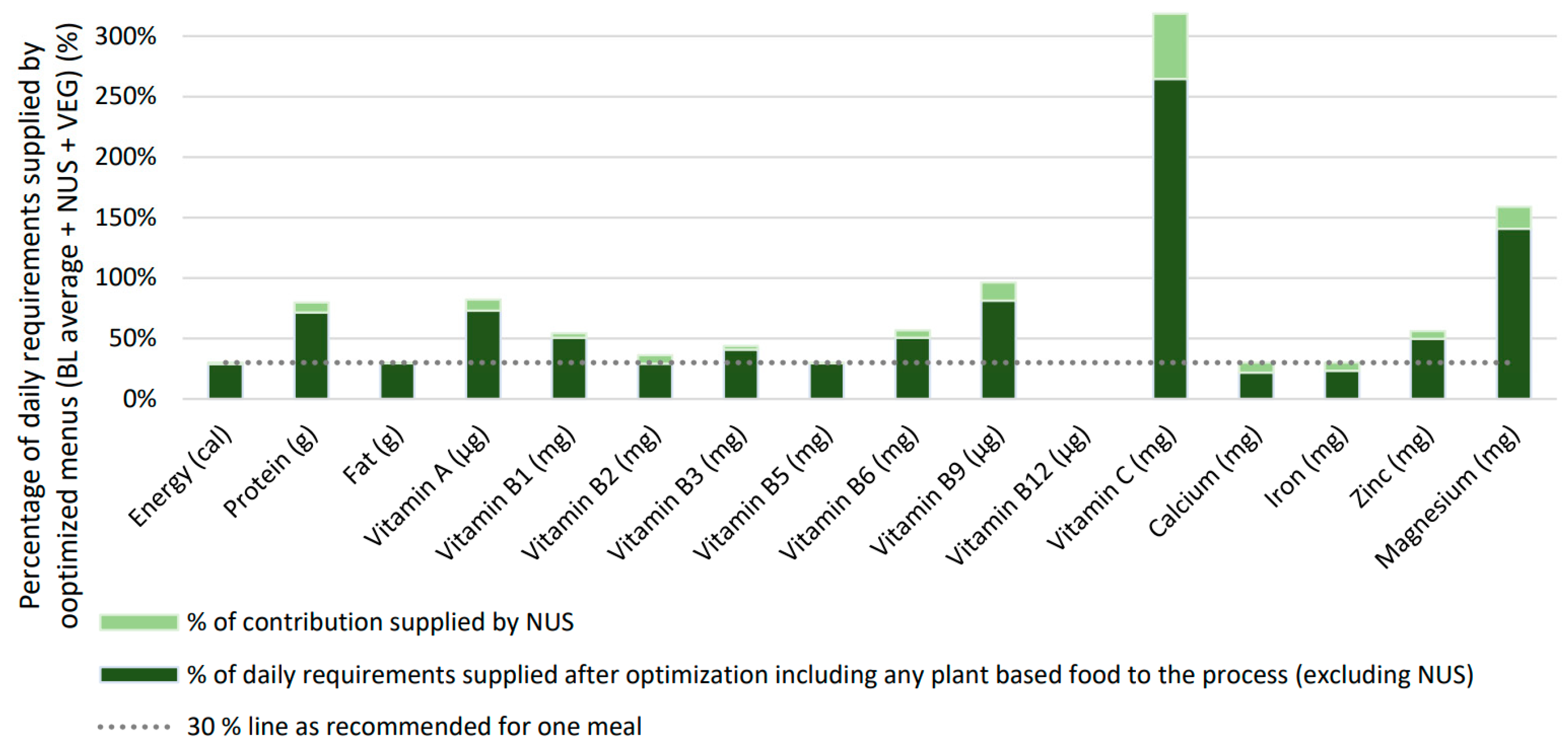

3.2.2. Second Optimization: Software Freely Selects Fruits, Legumes, and Vegetables, Including NUS

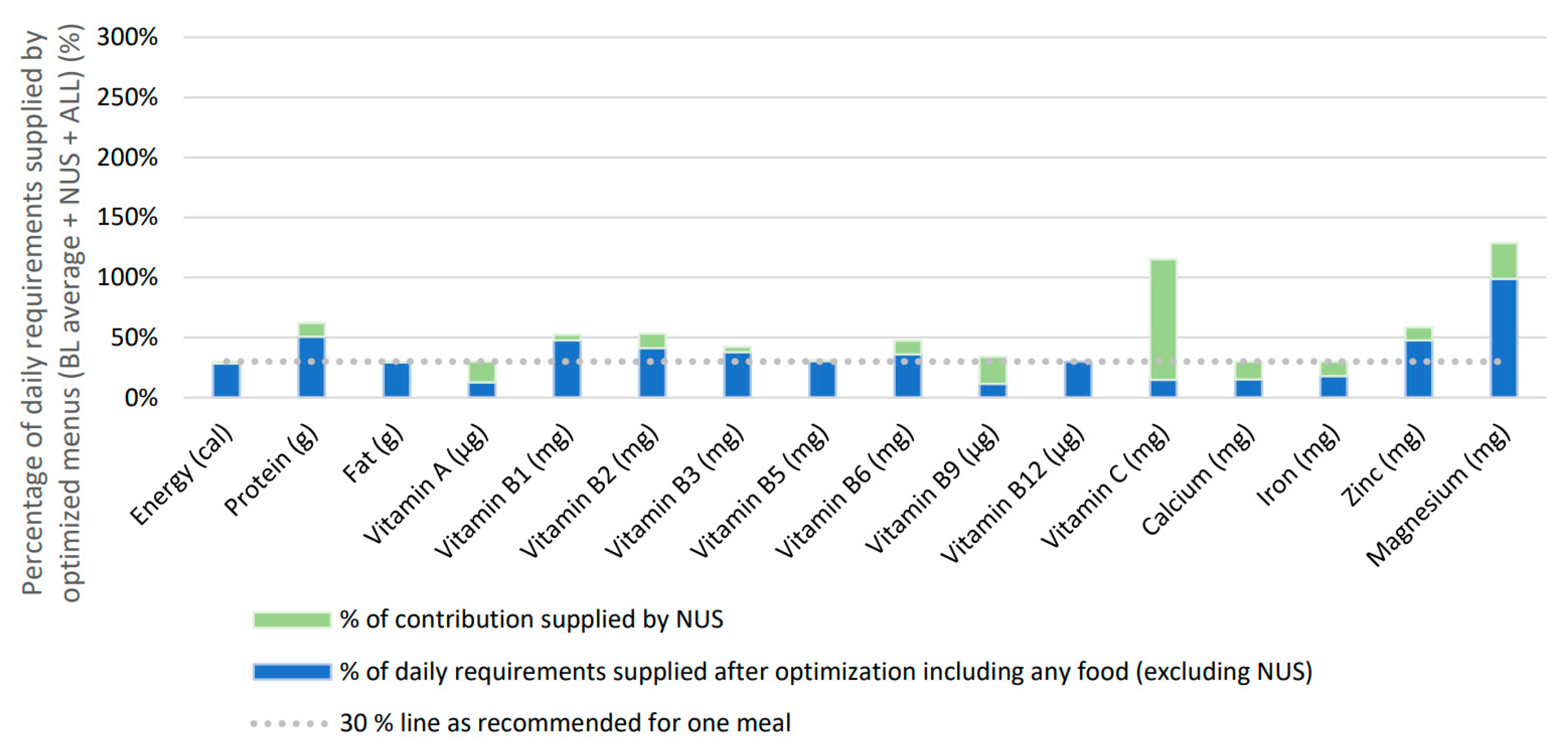

3.2.3. Third Optimization: Software Freely Selects All Menu Ingredients Including NUS

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kenya Food Security Steering Group The 2023 Short Rains. Food and Nutrition Security Assessment Report; Nairobi, Kenya, 2024;

- Global Nutrition Report Kenya Country Profile Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/africa/eastern-africa/kenya/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, W. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024; FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024; ISBN 978-92-5-138882-2.

- UNICEF Undernourished and Overlooked: A Global Nutrition Crisis in Adolescent Girls and Women; New York, USA, 2023;

- Bundy, D.A.P.; de Silva, N.; Horton, S.; Patton, G.C.; Schultz, L.; Jamison, D.T.; Abubakara, A.; Ahuja, A.; Alderman, H.; Allen, N.; et al. Investment in Child and Adolescent Health and Development: Key Messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. Lancet 2018, 391, 687–699.

- Beal, T.; Manohar, S.; Miachon, L.; Fanzo, J. Nutrient-Dense Foods and Diverse Diets Are Important for Ensuring Adequate Nutrition across the Life Course. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121, doi:10.1073/pnas.2319007121. [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, S.; Hughes, D.; Schultz, L.; Owen, S.; Morris, K.M.; Backlund, U.; Bellanca, R.; Hunter, D.; Kaljonen, M.; Singh, S.; et al. School Meals and Food Systems: Rethinking the Consequences for Climate, Environment, Biodiversity, and Food Sovereignty; London, UK, 2023.

- Republic of Kenya Sessional Paper No. 4 of 1981 on National Food Policy 1981, 52.

- Republic of Kenya The Constitution of Kenya, 2010 2010, 211.

- Republic of Kenya National School Meals and Nutrition Strategy 2017-2022 2018, 61.

- Office of the Auditor-General The Auditor-General’s Performance Audit Report on National School Meals and Nutrition Programme; Nairobi, Kenya, 2023.

- School Meals Coalition Kenya Champions Planet-Friendly School Meals Available online: https://schoolmealscoalition.org/stories/kenya-champions-planet-friendly-school-meals (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- School Meals Coalition Governments Announce Strategic Priorities to Achieve Universal School Meals by 2030 Available online: https://schoolmealscoalition.org/stories/press-release-governments-announce-strategic-priorities-achieve-universal-school-meals-2030 (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- SMC Secretariat Kenya Champions Planet-Friendly School Meals Available online: https://schoolmealscoalition.org/stories/kenya-champions-planet-friendly-school-meals (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Hunter, D.; Borelli, T.; Beltrame, D.M.O.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Coradin, L.; Wasike, V.W.; Wasilwa, L.; Mwai, J.; Manjella, A.; Samarasinghe, G.W.L.; et al. The Potential of Neglected and Underutilized Species for Improving Diets and Nutrition. Planta 2019, 250, 709–729, doi:10.1007/s00425-019-03169-4. [CrossRef]

- Borelli, T.; Wasike, V.; Manjella, A.; Hunter, D.; Wasilwa, L. Linking Farmers and Schools to Improve Diets and Nutrition in Busia County, Kenya. In Public food procurement for sustainable food systems and healthy diets – Volume 2; Swensson, L.F.J., Hunter, D., Schneider, S., Tartanac, F., Eds.; FAO; Bioversity International and Editora UFRGS: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 338–353 ISBN 978-92-5-135479-7.

- Gelli, A.; Aurino, E. School Food Procurement and Making the Links between Agriculture, Health and Nutrition; Swensson, L.F.J., Hunter, D., Schneider, S., Tartanac, F., Eds.; 1st ed.; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135475-9.

- Agrobiodiversity, School Gardens and Healthy Diets; Hunter, D., Monville-Oro, E., Burgos, B., Rogel, C.N., Calub, B., Gonsalves, J., Lauridsen, N., Eds.; 1st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2020., 2020; ISBN 9780429053788.

- Hunter, D.; Loboguerrero, A.M.; Martínez-Barón, D. Next-Generation School Feeding: Nourishing Our Children While Building Climate Resilience. UN-Nutrition. Transform. Nutr. 2022, 1, 158–163, doi:10.4060/cc2805en. [CrossRef]

- FAO; Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT; Editora da UFRGS Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Food Systems and Healthy Diets - Volume 2; Swensson, L.F.J., Hunter, D., Schneider, S., Tartanac, F., Eds.; 1st ed.; Rome, Italy, 2021; ISBN 978-92-5-135479-7.

- Gelli, A.; Neeser, K.; Drake, L. Home Grown School Feeding: Linking Small Holder Agriculture to School Food Provision; HGSF; London, UK, 2010.

- Borelli, T.; Nekesa, T.; Mbelenga, E.; Jumbale, M.; Morimoto, Y.; Bellanca, R.; Jordan, I. Planet Friendly Home-Grown School Feeding: What Does It Mean?; Rome, Italy, 2024.

- Karl, K.; MacCarthy, D.; Porciello, J.; Chimwaza, G.; Fredenberg, E.; Freduah, B.S.; Guarin, J.; Mendez Leal, E.; Kozlowski, N.; Narh, S.; et al. Opportunity Crop Profiles for the Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS) in Africa; 2024.

- Singh, S. Home-Grown School Feeding: Promoting the Diversification of Local Production Systems through Nutrition-Sensitive Demand for Neglected and Underutilized Species. In Public food procurement for sustainable food systems and healthy diets - Volume 1; Swensson, L.F.J., Hunter, D., Schneider, S., Tartanac, F., Eds.; FAO and Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2021; pp. 125–141 ISBN 978-92-5-135475-9.

- Medeiros, G.C.B.S. de; Azevedo, K.P.M. de; Garcia, D.; Oliveira Segundo, V.H.; Mata, Á.N. de S.; Fernandes, A.K.P.; Santos, R.P. dos; Trindade, D.D.B. de B.; Moreno, I.M.; Guillén Martínez, D.; et al. Effect of School-Based Food and Nutrition Education Interventions on the Food Consumption of Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19.

- Contento, I.R.; Manning, A.D.; Shannon, B. Research Perspective on School-Based Nutrition Education. J. Nutr. Educ. 1992, 24, doi:10.1016/S0022-3182(12)81240-4. [CrossRef]

- Berg, A. More Resources for Nutrition Education: Strengthening the Case. J. Nutr. Educ. 1993, 25.

- FAO; Alliance of Bioversity International; CIAT Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Food Systems and Healthy Diets - Volume 2; 2021.

- Padulosi, S.; Roy, P.; Rosado-May, F.J. Supporting Nutrition Sensitive Agriculture through Neglected and Underutilized Species - Operational Framework ; Rome, 2019.

- Bharucha, Z.; Pretty, J. The Roles and Values of Wild Foods in Agricultural Systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 2913–2926.

- FAO The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture; Belanger, J., Pilling, D., Eds.; 1st ed.; FAO, Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture Assessments: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131270-4.

- Smith, G.C.; Dueker, S.R.; Clifford, A.J.; Grivetti, L.E. Carotenoid Values of Selected Plant Foods Common to Southern Burkina Faso, West Africa. Ecol. Food Nutr. 1996, 35, doi:10.1080/03670244.1996.9991474. [CrossRef]

- UNEP; CBD; WHO Connecting Global Priorities: Biodiversity and Human Health: A State of Knowledge Review; 1st ed.; World Health Organization and Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2015; ISBN 9789241508537.

- Kuyper, E.; Vitta, B.; Dewey, K. Novel and Underused Food Sources of Key Nutrients for Complementary Feeding; A&T Technical Brief; Washington DC, USA, 2013; Vol. 6.

- Fuks, D.; Schmidt, F.; García-Collado, M.I.; Besseiche, M.; Payne, N.; Bosi, G.; Bouchaud, C.; Castiglioni, E.; Dabrowski, V.; Frumin, S.; et al. Orphan Crops of Archaeology-based Crop History Research. Plants, People, Planet 2024, doi:10.1002/ppp3.10468. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, L.; Hussain, A.; Rasul, G. Tapping the Potential of Neglected and Underutilized Food Crops for Sustainable Nutrition Security in the Mountains of Pakistan and Nepal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 291, doi:10.3390/su9020291. [CrossRef]

- Padulosi, S.; Thompson, J.; Rudebjer, P. Fighting Poverty, Hunger and Malnutrition with Neglected and Underutilized Species: Needs, Challenges and the Way Forward; 2013.

- Bala Ravi, S.; Swain, S..; Sengotuvel, D.; Parida, N.R. Promoting Nutritious Millets for Enhancing Income and Improved Nutrition: A Case Study From Tamil Nadu and Orissa. In Minor millets in South Asia – Learning from the IFAD-NUS Project in India and Nepal; Bioversity International, Ed.; Bioversity International: Chennai, 2010; pp. 19–46.

- Vietmeyer, N.D. Lesser-Known Plants of Potential Use in Agriculture and Forestry. Science (80-. ). 1986, 232, 1379–1384, doi:10.1126/science.232.4756.1379. [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, M.; Scheelbeek, P.; Mjabuliseni, N.; Mabhaudhi, T. Underutilized Crops for Diverse, Resilient and Healthy Agri-Food Systems: A Systematic Review of Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. Sec. Clim. Food Syst. 2024, 8, doi:10.3389/fsufs.2024.1498402. [CrossRef]

- Gelli, A.; Masset, E.; Folson, G.; Kusi, A.; Arhinful, D.K.; Asante, F.; Ayi, I.; Bosompem, K.M.; Watkins, K.; Abdul-Rahman, L.; et al. Evaluation of Alternative School Feeding Models on Nutrition, Education, Agriculture and Other Social Outcomes in Ghana: Rationale, Randomised Design and Baseline Data. Trials 2016, 17, 37, doi:10.1186/s13063-015-1116-0. [CrossRef]

- Sumberg, J.; Sabates-Wheeler, R. Linking Agricultural Development to School Feeding in Sub-Saharan Africa: Theoretical Perspectives. Food Policy 2011, 36, 341–349, doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2011.03.001. [CrossRef]

- FAO, A. of B.I.& C. Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Food Systems and Healthy Diets - Volume 1; 2021.

- Mashamaite, C.V.; Manyevere, A.; Chakauya, E. Cleome Gynandra: A Wonder Climate-Smart Plant for Nutritional Security for Millions in Semi-Arid Areas. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1003080. [CrossRef]

- Kayitesi, E.; Moyo, S.M. Spider Plant (Cleome Gynandra). In Handbook of Phytonutrients in Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables; CABI: GB, 2022; pp. 27–49.

- Van den Heever, E.; Venter, S.L. Nutritional and Medicinal Properties of Cleome Gynandra. Acta Hortic. 2007, 127–130, doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2007.752.17. [CrossRef]

- Ramatsetse, K.E.; Ramashia, S.E.; Mashau, M.E. A Review on Health Benefits, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Properties of Bambara Groundnut (Vigna Subterranea). Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 91–107, doi:10.1080/10942912.2022.2153864. [CrossRef]

- Chelangat, M.; Muturi, P.; Gichimu, B.; Gitari, J.; Mukono, S. Nutritional and Phytochemical Composition of Bambara Groundnut (Vigna Subterranea [L.] Verdc) Landraces in Kenya. Int. J. Agron. 2023, 2023, 1–11, doi:10.1155/2023/9881028. [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Azam-Ali, S.; Goh, E. Von; Mustafa, M.; Chai, H.H.; Ho, W.K.; Mayes, S.; Mabhaudhi, T.; Azam-Ali, S.; Massawe, F. Bambara Groundnut: An Underutilized Leguminous Crop for Global Food Security and Nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, doi:10.3389/fnut.2020.601496. [CrossRef]

- Veldsman, Z.; Pretorius, B.; Schönfeldt, H.C. Examining the Contribution of an Underutilized Food Source, Bambara Groundnut, in Improving Protein Intake in Sub-Saharan Africa. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, doi:10.3389/fsufs.2023.1183890. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D.K.; Singh, S.; Dubey, S.K.; Mehra, T.S.; Dixit, S.; Sawargaonkar, G. Nutrient Profiling of Lablab Bean (Lablab Purpureus) from North-Eastern India: A Potential Legume for Plant-Based Meat Alternatives. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 119, 105252, doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2023.105252. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Naresh, P.; Acharya, G.C.; Laxminarayana, K.; Singh, H.S.; Raghu, B.R.; Aghora, T.S. Nutritional Diversity of Indian Lablab Bean (Lablab Purpureus (L.) Sweet): An Approach towards Biofortification. South African J. Bot. 2022, 149, 189–195, doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2022.06.002. [CrossRef]

- Sahou, D.M.; Makokha, A.O.; Sila, D.N.; Abukutsa-Onyango, M.O. Nutritional Composition of Slenderleaf (Crotalaria Ochroleuca and Crotalaria Brevidens) Vegetable at Three Stages of Maturity. J. Agric. Food Technol. 2014, 4.

- Ngidi, M.S.C. The Role of Traditional Leafy Vegetables on Household Food Security in Umdoni Municipality of the KwaZulu Natal Province, South Africa. Foods 2023, 12, 3918, doi:10.3390/foods12213918. [CrossRef]

- Abukutsa-Onyango, M.O.; Kavagi, P.; Amoke, P.; Habwe, F.O. Iron and Protein Content of Priority Vegetables in the Lake Victoria Basin. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2010, 4, 67–69.

- Kirigia, D.; Winkelmann, T.; Kasili, R.; Mibus, H. Nutritional Composition in African Nightshade (Solanum Scabrum) Influenced by Harvesting Methods, Age and Storage Conditions. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2019, 153, 142–151, doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2019.03.019. [CrossRef]

- FAO; Republic of Kenya Kenya Food Composition Tables; 1st ed.; FAO/Republic of Kenya: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018; ISBN 978-92-5-130445.

- Mibei, E.K.; Ojijo, N.K.O.; Karanja, S.M.; Kinyua, J.K. Compositional Attributes of the Leaves of Some Indigenous African Leafy Vegetables Commonly Consumed in Kenya. Ann. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 12, 146–154.

- Government of Kenya School Nutrition and Meals Strategy for Kenya; 2016.

- Government of Kenya National School Meals and Nutrition Strategy 2017-2022; 2018.

- Bundy, D.A..; Gentilini, U.; Schultz, L.; Bedasso, B.; Singh, S.; Okamura, Y.; Iyengar, H.T.M.M.; Blakstad, M.M. School Meals, Social Protection and Human Development: Revisiting Trends, Evidence, and Practices in South Asia and Beyond; Social Protection & Jobs; Washington DC, USA, 2024.

- Nyonje, W.; Roothaert, R. Feasibility Study for Inclusion of Traditional Leafy Vegetables in School Feeding Programs in Kenya; Arusha, Tanzania, 2024.

- MUFPP School Meals: The Transformative Potential of Urban Food Policies; Milan, Italy, 2024.

- Mathenge, N.M.; Ghauri, T.A.; Mutie, C.K.; Sienaert, A.; Angelique, U. Kenya Economic Update: Aiming High. Securing Education to Sustain the Recovery; Nairobi, Kenya, 2022.

- Kamau, J.; Wanjohi, M.N.; Raburu, P. School Meals Case Study: Kenya; Nairobi, Kenya, 2024.

- SMC Secretariat School Meals Coalition Task Force Meeting Outcome Statement Available online: https://schoolmealscoalition.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/Leaders Statement Kenya TF Meeting 29 October 2024_29.10.24 final pub.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Kimani, O.; Chege, C.; Musita, C.; Termote, C. Transforming Food Systems in Kisumu: Sustainable Innovations for Nutrition and Food Security Available online: https://alliancebioversityciat.org/stories/transforming-food-systems-kisumu-sustainable-innovations-nutrition-and-food-security (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- WFP State of School Feeding Worldwide 2020; Rome, Italy, 2020.

- EFSA Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for Vitamins and Minerals; 2006.

- FAO Nutrition Guidelines and Standards for School Meals: A Report from 33 Low and Middle-Income Countries; Rome, Italy, 2019.

| Nutritional analysis and optimizations | VFA menus | Cost per meal, per day (USD) | Kcal | Prot (g) | Fat(g) | Vit A (µg) | Vit C (mg) | Vit B12 (µg) | Ca (mg) | Fe (mg) | Zn (mg) | Mg (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline menus | Best menu | 0.40 | √ | √ | ▼ | ▲ | ▲ | X | ▼ | √ | √ | ▲ |

| Sub-optimal menu | 0.25 | √ | √ | ▼ | √ | √ | X | ▼ | ▼ | √ | √ | |

| First optimization | BL best-possible + | 0.22 | √ | √ | √ | ▲ | ▲ | X | √ | √ | √ | ▲ |

| BL sub-optimal + | 0.26 | √ | ▲ | √ | √ | √ | X | √ | √ | √ | ▲ | |

| Second optimization | BL average + NUS + VEG** | 0.14 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ▲ | X | √ | √ | √ | ▲ |

| Third optimization | BL average + NUS + ALL** | 0.13 | √ | √ | √ | √ | ▲ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ▲ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).