Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

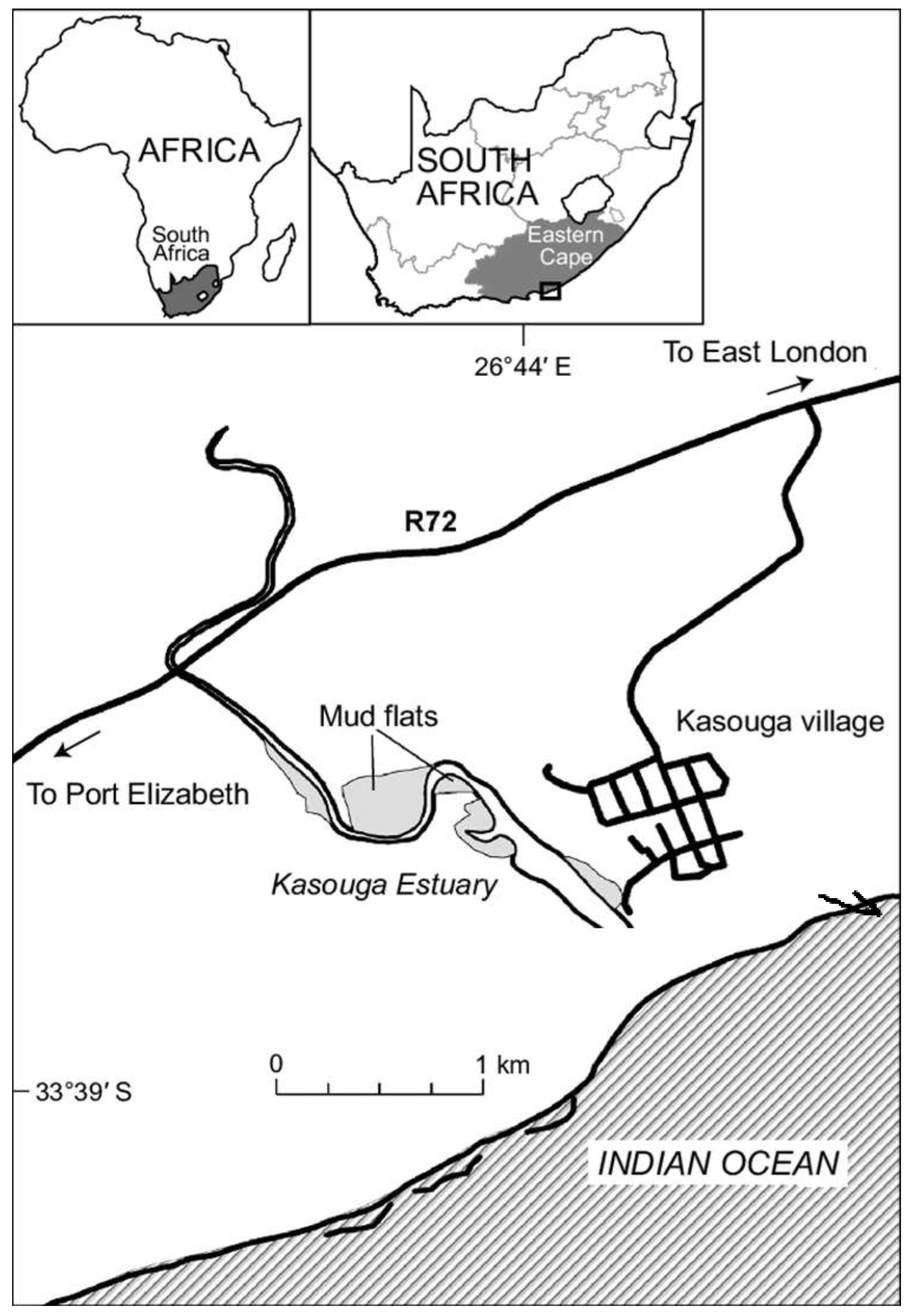

2.Study Site

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bioturbation

3.1.1. Microphytobenthic Algal Concentrations

3.1.2. Epifauna and Infauna Community Structure

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

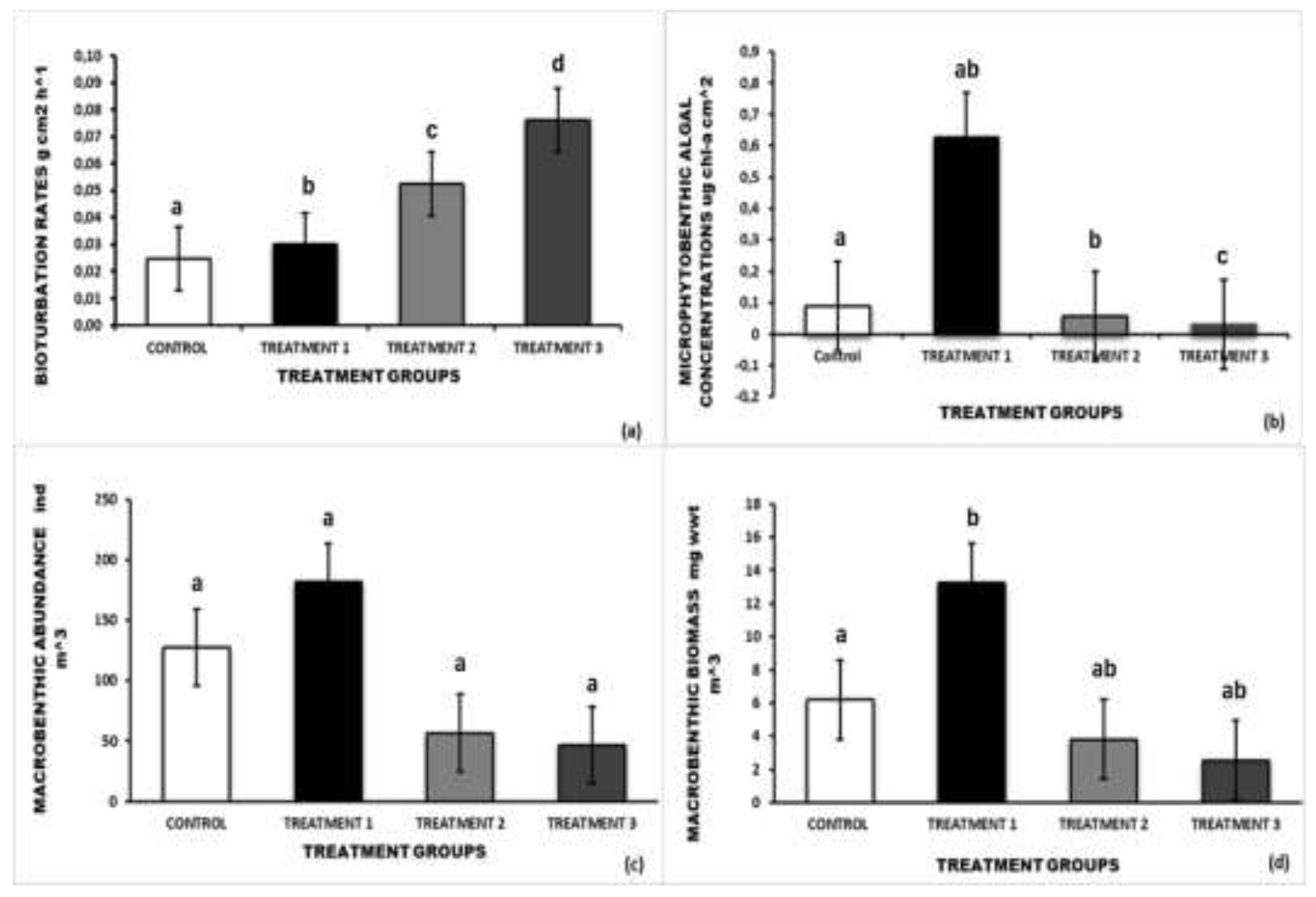

5.1. Bioturbation

5.1.1. Microphytobenthic Algal Concentrations

5.1.2. Macrobenthic Abundances

5.1.3. Macrobenthic Biomass

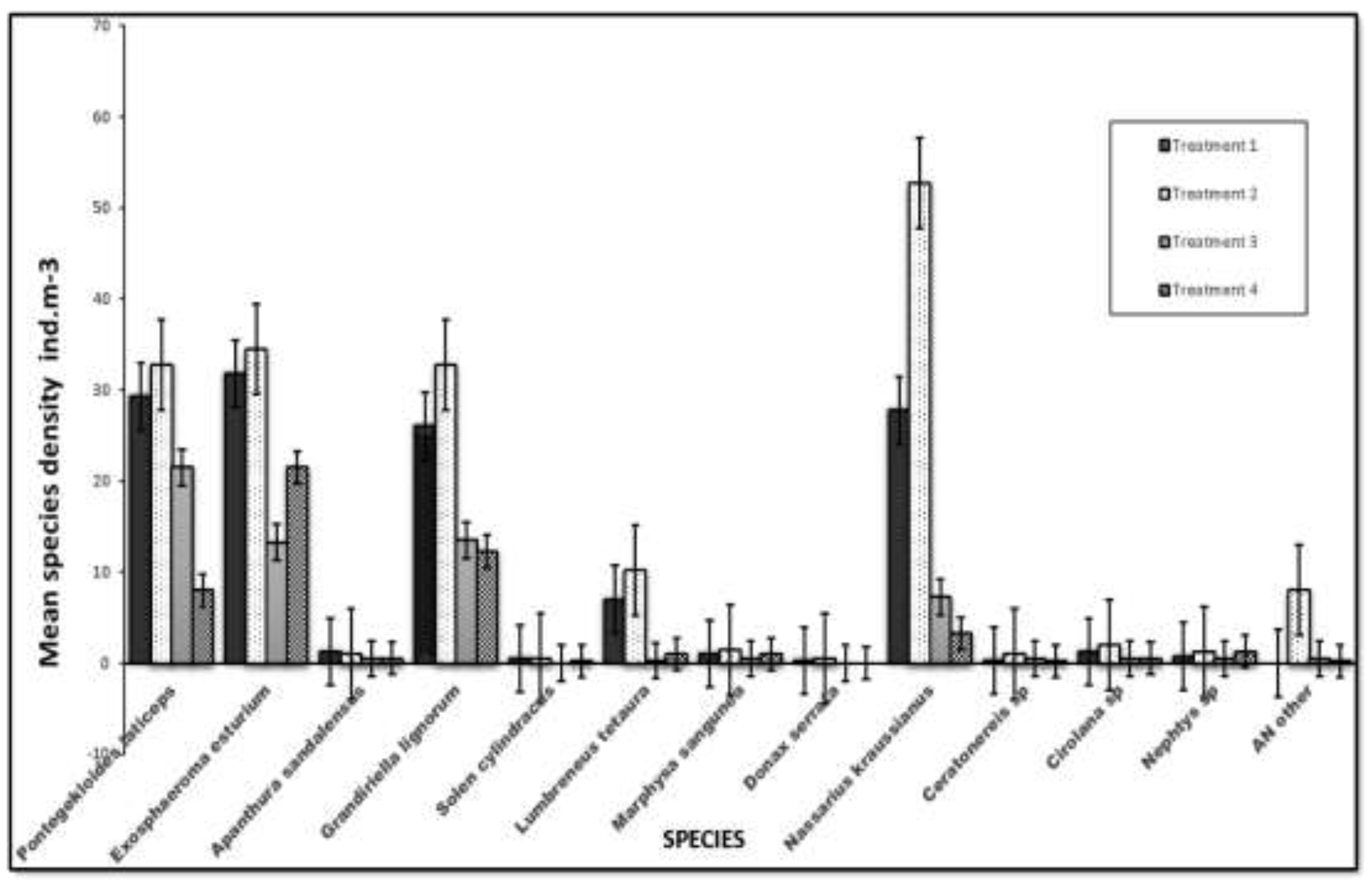

5.1.4. Epifaunal and Infaunal Community Structure

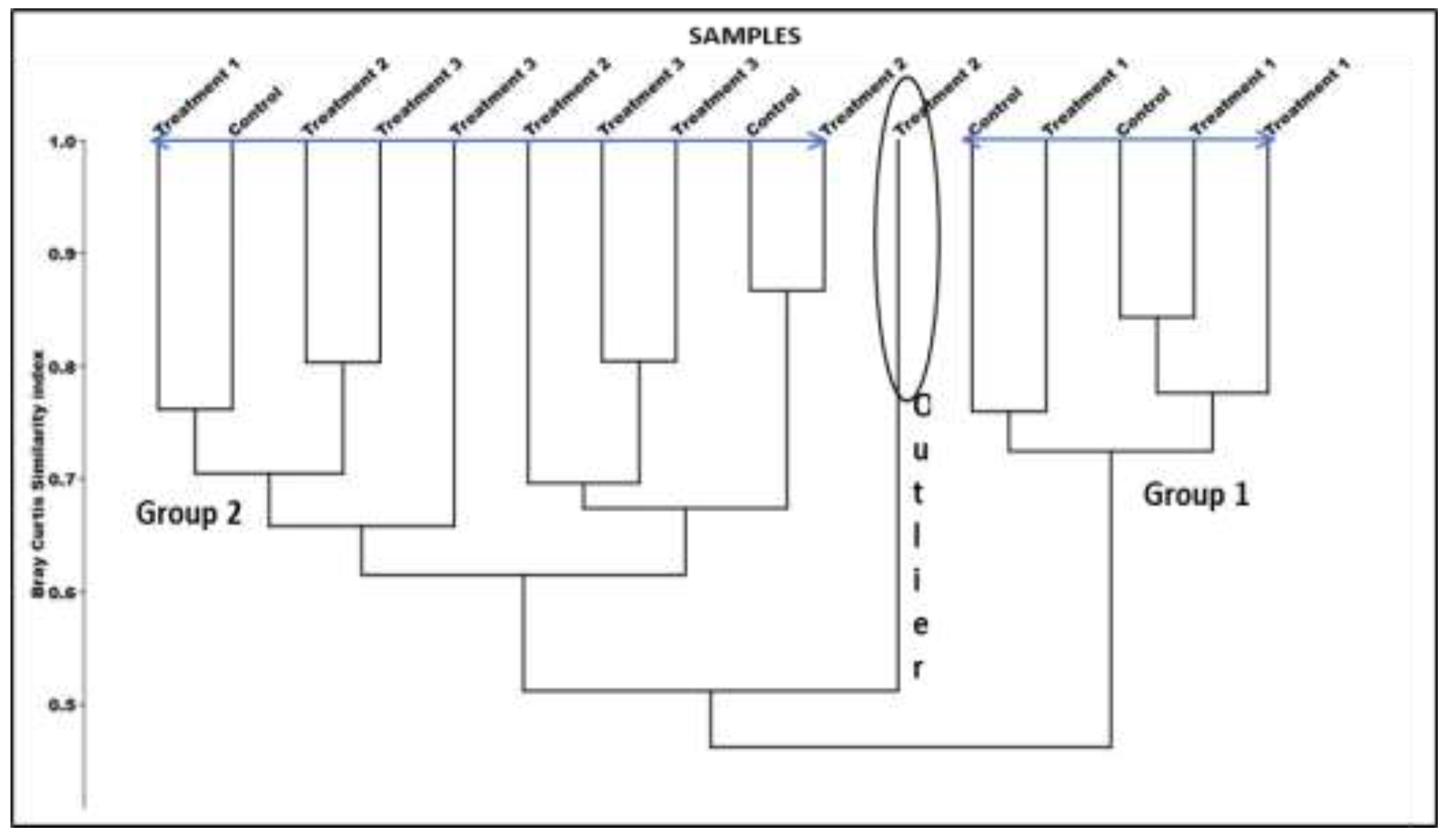

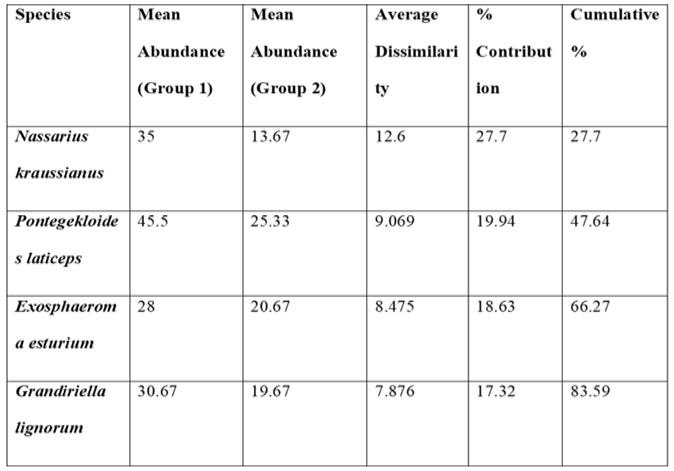

5.1.5. Bray Curtis Cluster Analysis

|

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moyo, R. 2014. Ecology and behaviour of burrowing prawns and their burrow symbionts. University of Cape Town. MSc thesis.

- Siebert, T., & Branch, G.M. 2006. Ecosystem engineers: interactions between eelgrass Zostera capensis and the sandprawn Callianassa kraussi and their indirect effects on the mudprawn Upogebia africana. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 338: 253–270.

- Meysman, F. J. R., Middelburg, J. J., & Heip, C. H. R. (2006a). Bioturbation: a fresh look at Darwin’s last idea. In Trends in Ecology and Evolution (Vol. 21, Issue 12, pp. 688–695). [CrossRef]

- Henninger, T. O., & Froneman, P. W. (2013). Role of the sandprawn Callichirus kraussi as an ecosystem engineer in a South African temporarily open/closed estuary. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 38(1), 101–107. [CrossRef]

- Richter, R. (1952). Fluidal-texture in Sediment-Gesteinen und ober Sedifluktion überhaupt. Notizbl. Hess. L.-Amt. Bodenforsch. 3, 67-81.

- Dauwe, B., Herman P. M. J., & Heip C. H. R. (1998). Community structure and bioturbation potential of macrofauna at four North Sea stations with contrasting food supply. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 173: 67-83.

- Wilkinson, M. T., Richards, P. J., & Humphreys, G. S. (2009). Breaking ground: Pedological, geological, and ecological implications of soil bioturbation. In Earth-Science Reviews (Vol. 97, Issues 1–4). [CrossRef]

- Vasquez-Cardenas, D., Quintana, C. O., Meysman, F. J. R., Kristensen, E & Henricus, T. S., Boschker, H. T. S. (2016), Species-specific effects of two bioturbating polychaetes on sediment chemoautotrophic bacteria. Marine Ecology Series. 549: 55–68. [CrossRef]

- Queiros, A. M., Stephens, N., Cook, R., Ravaglioli C., Nunes, J., Dashfield, S., Harris, C., Tilstone, G. H., Fishwick, J., Braeckman, U., Somerfield, P. J., & Widdicombe, S.S. (2015), Can benthic community structure be used to predict the process of bioturbation in real ecosystems? Progress in Oceanography. 137: 559–569.

- Biles, C. and Paterson, David and Ford, Rich and Solan, Martin and Raffaelli, David. (2002). Bioturbation, ecosystem functioning and community structure. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 6. 10.5194/hess-6-999-2002.

- Pillay, D., Branch, G. M., & Forbes, A. T. (2007a). Experimental evidence for the effects of the thalassinidean sandprawn Callianassa kraussi on macrobenthic communities. Mar. Biol. 152, 611–618.

- Pillay, D., Branch, G. M., & Forbes, A. T. (2007). Effects of Callianassa kraussi on microbial biofilms and recruitment of macrofauna: A novel hypothesis for adult-juvenile interactions. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 347, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Hanekom, N., & Russell, I. (2015). Temporal changes in the macrobenthos of sandprawn (Callichirus kraussi) beds in Swartvlei Estuary, South Africa. African Zoology. 50. 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, A.K. (1998) Biology and Ecology of Fishes in Southern African Estuaries. Ichthyol. Monogr. Smith Inst. Ichthyol. No. 2.223 pp.

- Whitfield, A.K. (2022). Fishes of Southern African estuaries: from species to systems. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10962/97933.

- Gama, P. T., Adams J. B., Schael D.M., & Skinner T. (2005). Phytoplankton chlorophyll a concentration and community structure of two temporarily open/closed estuaries. WRC Report No. 1255/1/05. ISBN: 1-77005-326-3.

- Whitfield, A.K., & Bate G.C., (eds). 2007. A review of information on temporary open/closed estuaries in the warm and cool temperate biogeographic region of South Africa, with particular emphasis on the influence of river flow on these systems. WRC Report 1581/1/07. Pretoria: Water Research Commission.

- Whitfield, A. K., Adams, J. B., Bate, G. C., Bezuidenhout, K., Bornman, T. G, Cowley, P. D., Froneman, P. W., Gama, P. T., James, N. C., Mackenzie, B., Riddin T., Snow, G. C., Strydom, N. A., Taljaard, S., Terörde, A.I., Theron, A. K., Turpie, J. K., van Niekerk, L., Vorwerk, P. D., & Wooldridge, T. H. (2008). A multidisciplinary study of a small, temporarily open/closed South African estuary, with particular emphasis on the influence of mouth state on the ecology of the system, African Journal of Marine Science. Volume 30:3, 453-473 pp. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, A. K., Bate, G. C., Adams, J. B., Cowley, P. D., Froneman, P. W., Gama, P. T., Strydom, N. A., Taljaard, S., Theron, A. K., Turpie, J. K., van Niekerk, L., & Wooldridge, T. H. (2012). A review of the ecology and management of temporarily open/closed estuaries in South Africa, with particular emphasis on river flow and mouth state as primary drivers of these systems. In African Journal of Marine Science (Vol. 34, Issue 2, pp. 163–180). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, T. (2004). Physico-chemical characteristics of South African estuaries in relation to the zoogeography of the region. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 61. 73-87. [CrossRef]

- 21. Harrison,T.D. Whitfield,A.K.2006. Temperature and salinity as primary determinants influencing the biogeography of fishes in South African estuaries,Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 66,(1–2):335-345. ISSN 0272-7714(https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272771405003161). [CrossRef]

- Teske, P., & Wooldridge, T. (2001). A comparison of the benthic faunas of permanently open and temporarily open/closed South African estuaries. Hydrobiologia. 464. 227-243. 10.1023/A:1013995302300.

- Teske P.R., & Wooldridge T.H. (2003). What limits the distribution of subtidal macrobethos in permanently open and temporarily open/closed South African estuaries? Salinity vs sediment particle size. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 85: 407–421.

- Branch G.M., & Pringle A. (1987). The impact of the sand prawn Callianassa kraussi Stebbing on sediment turnover and on bacteria, meiofauna, and benthic microflora. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 107: 219–235.

- Humphreys G. S., & Mitchell P. B. (1983), A preliminary assessment of the role of bioturbation and rain wash on sandstone hillslopes in the Sydney Basin, in Australian and New Zealand Geomorphology Group. 66-80pp.

- Njozela, C. (2012). The role of the sandprawn, Callichirus kraussi, as an ecosystem engineer in a temporarily open/closed Eastern Cape estuary, South Africa.

- Wyness A.J., Fortune I., Blight AJ., Browne P., Hartley M., Holden M., Paterson D.M. (2021). Ecosystem engineers drive differing microbial community composition in intertidal estuarine sediments. PLoS One.16(2):e0240952. PMID: 33606695, PMCID: PMC7895378. [CrossRef]

- Pillay D, and Branch G.M. (2011). Bioengineering effects of burrowing thalassinidean shrimps on marine soft-bottom ecosystems. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. ,49:137–192.

- Goedefroo, N., Braeckman, U., Hostens, K., Vanaverbeke, J., Moens, T., & De Backer, A. (2023). Understanding the impact of sand extraction on benthic ecosystem functioning: A combination of functional indices and biological trait analysis. Frontiers in Marine Science, 10, 1268999. [CrossRef]

- Emmerson, M.C., Solan, M., Emes, C., Paterson, D.M. andRaffaelli., D. (2001). Consistent patterns and the idiosyncraticeffects of biodiversity in marine systems. Nature, 411: 73–77.

- IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Summary for policymakers. In: T.F., Stocker, D.Q., Plattner, G.K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung J. (eds), Climate change (2013). The physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ziervogel, G., New, M., van Garderen, A.E., Midgley, G., Taylor, A., Hamann, R., Stuart-Hill, S., Myers, J., & Warburton, M. (2014). Climate change impacts and adaptation in South Africa. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(5): 605–620. [CrossRef]

- Mahlalela P.T., Blamey R.C., Hart N.C.G., Reason C.J.C. (2020). Drought in the Eastern Cape region of South Africa and trends in rainfall characteristics. Clim Dyn.,55(9-10):2743-2759. PMID: 32836893, PMCID: PMC7428292. [CrossRef]

- Froneman, P. W. (2018). The Ecology and Food Web Dynamics of South African Intermittently Open Estuaries. In Estuary. InTech. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield AK. 2000. Available scientific information on individual South African estuarine systems. Water Research Commission Report No. 577/3/00: 217 pp. Pretoria, South Africa: Water Research Commission.

- Wasserman, R. J., Kramer, R., Vink, T. J. F. & Froneman, P. W. (2014). Conspecific alarm cue sensitivity by the estuarine calanoid copepod Paracartia longipatella. Austral Ecology 39(6): 732–738.

- Froneman, P. W. (2002b). Seasonal changes in selected physico-chemical and biological variables in the temporarily open/closed kasouga estuary, eastern cape, south africa. African Journal of Aquatic Science, 27(2), 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Whitfield A.K. (1992). A characterization of southern African estuarine systems. South African Journal of Science 18:89-103.

- Froneman P.W. (2002). Response of the biology to three different hydrological phases in the temporarily open/closed Kasouga estuary. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science., 55:535-546. ISSN 0272-7714. [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge TH, McGwynne L. (1996) The estuarine environment. Report No. C31. Institute of Coastal Research, Port Elizabeth, South Africa. 91pp.

- Froneman, P., W. (2004). In situ grazing rates of the copepods, Pseudodiaptomus hessei and Acartia longipatella in a temperate, temporarily open/closed estuary. South African Journal of Science. 100: 577-583.

- Wasserman, R. J., Froneman P. W., (2013). Risk effects on copepods: preliminary experimental evidence for the suppression of clutch size by predatory early life-history fish, Journal of Plankton Research. 35: 421–426. [CrossRef]

- Henninger, T., Froneman, P.,W., Richoux, N., & Hodgson, A,. N. (2009). Role of submerged macrohytes and a refuge and food source for the estuarine isopod, Exospheroma hylocoetes. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 82:285-293.

- Ellis, J., Cumming V., Hewitt, J., Thrush, S., & Norkko, A. (2002). Determining effects of suspended sediment on condition of suspension bivalve (Atrina zelanica): results from a survey, a laboratory experiment and field transplant experiment. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 267: 147-174.

- Whitfield, A., & Baliwe, N. (2012). A numerical assessment of research outputs on South African estuaries. South African Journal of Science. 109. 01-04. [CrossRef]

- Day, J.H. (1969). A guide to marine life on South African shores. AA Bakema, Cape Town. South Africa.

- Menge, B., Berlow, E., Blanchette, C., Navarrete, S. and Yamada, S. (1994). The keystone species concept: variation in interactionstrength in a rocky intertidal habitat. Ecol. Monogr., 64: 249–286.

- Marenco, K., & Bottjer, D. (2007). 8 Ecosystem engineering in the fossil record: Early examples from the Cambrian Period. Theoretical Ecology Series. 4. [CrossRef]

- Berke, S. (2010). Functional Groups of Ecosystem Engineers: A Proposed Classification with Comments on Current Issues. Integrative and comparative biology. 50. 147-57. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A., M. (2019). Foundation species, non-trophic interactions, and the value of being common. iScience 13: 254–268.

- Almeida G.M., Valente N. F., Pacheco, E.O., Ganci, C. L, Mathew A. M, Adriano S. P., & Diogo, B. (2020). How Does the Landscape Affect Metacommunity Structure? A Quantitative Review for Lentic Environments. Curr Landscape Ecol Rep 5, 68–75.

- Nozias, C., Persinotto R., Mundree, S. (2001). Annual cycle of microalgal biomass in a South African temporarily-open estuary: Nutrient versus light limitation. Marine Ecology Progress Series.,223:39-48.

- Perissinotto, R., Iyer, K., and Nozais, C. (2006). Response of microphytobenthos to flow and trophic variation in two South African temporarily open/closed estuaries. Botanica Marina, 49(1), 10–22. [CrossRef]

- Scharler, U.M., Lechman, K., Radebe, T., Jerling, H.L., (2020). Effects of prolonged mouth closure in a temporarily open/closed estuary : a summary of the responses of invertebrate communities in the uMdloti Estuary , South Africa. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 45, 121–130. [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B & Van Niekerk, L. (2020). Ten Principles to Determine Environmental Flow Requirements for Temporarily Closed Estuaries. Water 12, 1944. [CrossRef]

- Pillay, D. (2010). Expanding the envelope: linking invertebrate bioturbators with micro-evolutionary change. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 409:301-303. [CrossRef]

- Queiros, A.M., Stephens N., Cook R., Ravaglioli C., Nunes J., Dashfield S., Harris C., Tilstone G. H., Fishwick J., Braeckman U., Somerfield P. J., & Widdicombe S. (2015). Can benthic community structure be used to predict the process of bioturbation in real ecosystems? Progress in Oceanography. 137: 559–569.

- Pillay, D., Branch, G.M., Dawson, J., & Henry, D. (2011). Contrasting effects of ecosystem engineering by cordgrass Spartima maritima and the sandprawn Callianassa kraussi in a marine-dominated lagoon. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 91: 169-176.

- Venter, O., Pillay, D., & Prayag, K. (2020). Water filtration by burrowing sandprawns provides novel insights on endobenthic engineering and solutions for eutrophication. Scientific Reports, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Pillay, D., Williams, C., & Whitfield, A.K. (2012). Indirect effects of bioturbation by the burrowing sandprawn Callichirus kraussi on a benthic foraging fish, Liza richardsonii. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 453, 151–158.

- McIlroy, D., & Logan, G.A., (1999). The impact of bioturbation on infaunal ecology and evolution during the Proterozoic–Cambrian transition: Palaios, v. 14, p. 58–72.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).