Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Ladder & Fuel Stacking Concepts

1.2. Health, Economic and Environmental Risks Associated with Cooking Fuels

2. Materials and Methods

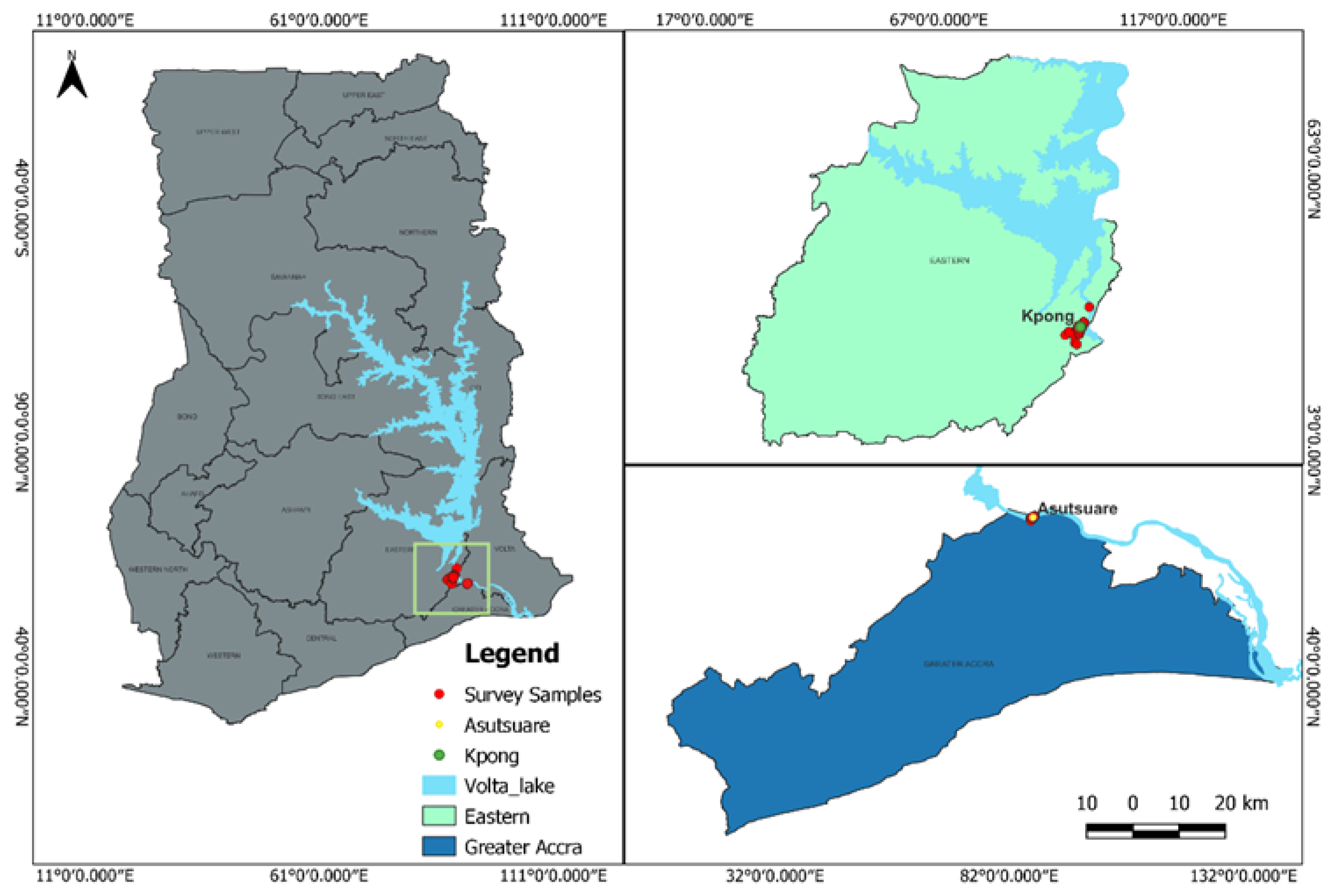

2.1. Study Setting, Sampling, and Sample Size Calculation

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Measures

Outcome Variables

Explanatory Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Participants

3.2. Bivariate Association Between Participant Characteristics and Fuel Type

3.3. Predicting the Association Between Study Characteristics and Fuel Choice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| B4CooingF | Briquette for cooking fuel |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| HH | Household |

| LPG | Liquified petroleum gas |

| LVL | Lower volta lake |

| REDCap | Research electronic device capture |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

References

- World Health Organization. Household Air Pollution and Health. Geneva, Switzerland. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs292/en/ (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Baiden, P.; Boateng, G.O; Dako-Gyeke, M.; Acolatse, C.K.; Peters, K.E. Examining the effects of household food insecurity on school absenteeism among Junior High School students: findings from the 2012 Ghana global school-based student health survey, African Geographical Review,2019,. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Marhold, K. Determinants of household energy use and fuel switching behavior in Nepal. Energy, 2019 169, 1132–1138. [CrossRef]

- Rahut, D. B.; Das, S.; Groote, H.; Behera, B. Determinants of household energy use in Bhutan. Energy, 2014 69, 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Karimu, A. ; Cooking fuel preferences among Ghanaian Households: An empirical analysis. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2015, 27, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, B.; Ali, A. Household energy choice and c intensity: Empirical evidence from Bhutan. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016, 53, 993–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Tang, X.; Wei, Y. M. Solid fuel use in rural China and its health effects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016, 60, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J.; & Bohara, A. K. Household preferences for cooking fuels and inter-fuel substitutions: Unlocking the modern fuels in the Nepalese household. Energy Policy, 2017, 107, 507–523.

- Muller, C.; Yan, H. Household fuel use in developing countries: Review of theory and evidence. Energy Economics, 2018, 70, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meried, E. W. Rural household preferences in transition from traditional to renewable energy sources: the applicability of the energy ladder hypothesis in North Gondar Zone. Heliyon, 2021, 7(11), 08418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, R. The Energy Ladder: A Valid Model for Household Fuel Transitions in Sub-Saharan Africa? Master of Science in Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning and Economics http://hdl.handle.net/10427/012067 (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Karimu A., Mensah J.T., Adu G. Who Adopts LPG as the Main Cooking Fuel and Why? Empirical Evidence on Ghana Based on National Survey. World Dev. 2016; 85:43–57. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.R.; McCracken, J.P.; Thompson, L.; Edwards, R.; Shields, K.N.; Canuz, E.; Bruce, N. Personal child and mother carbon monoxide exposures and kitchen levels: Methods and results from a randomized trial of woodfired chimney cookstoves in Guatemala (RESPIRE). J. Exp. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2010, 20, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dendup N., Arimura T.H. Information leverage: The adoption of clean cooking fuel in Bhutan. Energy Policy. 2018; 125:181–195 . [CrossRef]

- Ogwumike, F. O.; Ozughalu, U. M.; Abiona, G. A. Household energy use and determinants: Evidence from Nigeria. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 2014, 4, 248–262. [Google Scholar]

- Masera, O. R.; Navia, J. Fuel switching or multiple cooking fuels? Understanding inter-fuel substitution patterns in rural Mexican households. Biomass and Bioenergy, 1997, 12, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonjour, S.; Adair-Rohani, H.; Wolf, J.; Bruce, N.G.; Mehta, S.; Prüss-Ustün, A.; Lahi, M.; Rehfuess, E.A.; Mishra, V.; Smith, K.R. Solid fuel use for household cooking: Country and regional estimates for 1980–2010. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A. The impact of credit accessibility on rural households clean cooking energy consumption: The case of Ghana. Energy Rep. 2020; 6:974–983. [CrossRef]

- McCarron A., Uny I., Caes L., Lucas S.E., Semple S., Ardrey J., Price H. Solid fuel users’ perceptions of household solid fuel use in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. Environ. Int. 2020; 143:105991. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105991. [CrossRef]

- Nansaior, A.; Patanothai, A.; Rambo, A. T.; Simaraks, S. Climbing the energy ladder or diversifying energy sources? The continuing importance of household use of biomass energy in urbanizing communities in Northeast Thailand. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2011 35(10), 4180-4188.

- Lam, N. L.; Smith, K. R.; Gauthier, A.; Bates, M. N. Kerosene: a review of household uses and their hazards in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B, 2012, 15, 396–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldemberg, J. Pesquisa e desenvolvimento na área de energia. São Paulo em perspectiva, 2000, 14, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heltberg, R. Household fuel and energy use in developing countries: A multi-country study. The World Bank, 2005, 1–87.

- Gould C.F., Schlesinger S.B., Molina E., Bejarano M.L., Valarezo A., Jack D.W. Household fuel mixes in peri-urban and rural Ecuador: Explaining the context of LPG, patterns of continued firewood use and the challenges of induction cooking. Energy Policy. 2020; 136:111053. [CrossRef]

- Van der Kroon, B.; Brouwer, R.; Van Beukering, P. J. The energy ladder: Theoretical myth or empirical truth? Results from a meta-analysis. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 2013, 20, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W. , Zhou X., Renwick A. Impact of off-farm income on household energy expenditures in China: Implications for rural energy transition. Energy Policy. 2018; 127:248–258. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2016). Clean Household Energy for Health, Sustainable Development, and Wellbeing of Women and children. In WHO Guide. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204717/1/9789241565233_eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Sharma, D.; Ravindra, K.; Kaur, M.; Prinja, S.; Mor, S. Cost evaluation of different household fuels and identification of the barriers for the choice of clean cooking fuels in India. Sustainable Cities and Society, 2020, 52, 101825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.; Beard, M.; Clifford, M. J.; Watson, M. C. An evaluation of a biomass stove safety protocol used for testing household cookstoves, in low and middle-income countries. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2016, 33, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Mottaleb, K. A.; Aryal, J. P. Wealth, education and cooking-fuel choices among rural households in Pakistan. Energy Strategy Reviews, 2019, 24, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiritu, S. W.; Nyangena, W. Environmental goods collection and children’s schooling: Evidence from Kenya. Regional Environmental Change, 2011, 11(3), 531–542.

- World Energy Outlook 2022. www.iea/org/weo. Accessed on 15th December, 2025.

- World Energy Outlook 2019. www.iea.org/weo. Accessed on 7th January, 2022.

- Burwen, J.; Levine, D. I. A rapid assessment randomized-controlled trial of improved cookstoves in rural Ghana. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2012, 16(3), 328–338.

- Adeyemi, P. A.; Adereleye, A. Determinants of household choice of cooking energy in Ondo state, Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 2016, 7, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, V. B.; Meshram, P. U. Behavioral Change in Determinants of the Choice of Fuels amongst Rural Households after the Introduction of Clean Fuel Program: A District-Level Case Study. Global Challenges, 2021, 5, 2000004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mperejekumana, P.; Li, H.; Wu, R.; Lu, J.; Tursunov, O.; Elshareef, H.; Dong, R. Determinants of household energy choice for cooking in Northern Sudan: A multinomial logit estimation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021; 18, 21, 11480. [Google Scholar]

- Endalew, M.; Belay, D. G.; Tsega, N. T.; Aragaw, F. M.; Gashaw, M.; Asratie, M. H. Household Solid Fuel Use and Associated Factors in Ethiopia: A Multilevel Analysis of Data From 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. Environmental Health Insights, 2022, 16, 11786302221095033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quansah, R.; Semple, S.; Ochieng, C. A.; Juvekar, S.; Armah, F. A.; Luginaah, I.; Emina, J. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce household air pollution and/or improve health in homes using solid fuel in low-and-middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int. 2017, 103:73-90. [CrossRef]

- Rutterford, C.; Copas, A; Eldridge, S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2015, 44:1051-67. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Questionnaire on Health Survey. 2019.(2_harmonized_household_energy_survey_questions long_roster_final_nov2019.pdf). (accessed on 30 November 2019).

- Thompson, C. G.; Kim, R. S.; Aloe, A. M.; Becker, B. J. Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology,2017 39(2), 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Florkowski, W.J.; Sarpong, D.B.; Chinnan, M.; Resurreccion, A.V. Cooking fuel usage in sub-Saharan urban households, Energies 2021, 14(15), 4629.

- Kutortse, D.K. Residential energy demand elasticity in Ghana: an application of the quadratic almost ideal demand systems (QUAIDS) model. Cogent Economics & Finance, 2022 10(1).

- Ifegbesan, A.P.; Rampedi, I.T.; Annegarn, H. Nigerian households' cooking energy use, determinants of choice, and some implications for human health and environmental sustainability. Habitat International, 2016, 55, 17-24.

- Zhang, X.-B.; Hassen, S. Household fuel choice in urban China: evidence from panel data. Environment and Development Economics, 2017, 22(4), 392–413. [CrossRef]

- Waweru, D.; Mose, N. Fuel Choices in Urban Kenyan Households. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development. 2022, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Assa, M.; Maonga, B.; Gebremariam, G. Non-price determinants of household’s choice of cooking energy in Malawi. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 2015, 4 (1).

- Immurana, M.; Kisseih, K.; Yakubu, M.; Yusif, H. Financial inclusion and households’ choice of solid waste disposal in Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2022, 22. 10.1186/s12889-022-13512-2.

- Katutsi, V.; Dickson, T.; Migisha, A. Drivers of Fuel Choice for Cooking among Uganda's Households. Open Journal of Energy Efficiency. 2020, 9. 111-129. Open Journal of Energy Efficiency. [CrossRef]

- Perros, T.; Allison, A.L.; Tomei, J. Behavioural factors that drive stacking with traditional cooking fuels using the COM-B model. Nat Energy. 2022 ,7. 886–898. [CrossRef]

| Study population characteristics | Frequency | Percent | ||

| Characteristics of primary cook | ||||

| Age | 248 160 12 |

59.20 38.20 2.60 |

||

| Less than 40years | ||||

| 41 - 64years 65years and above |

||||

| Sex of primary cook Male Female |

27 393 |

6.40 93.50 |

||

| Educational level of primary cook Primary Secondary Tertiary |

331 68 21 |

79.00 16.20 4.80 |

||

| Civil status of primary cook Single Married Ever Married |

81 212 127 |

19.10 50.60 30.30 |

||

| Religion of primary cook Christian Muslim Agonist |

386 25 9 |

92.10 6.00 1.90 |

||

| Ethnicity of Primary Cook Ga-Adambge Ewe Akan Others |

83 239 19 79 |

19.80 57.00 4.50 18.60 |

||

| BMI category Under weight (<18.5) Normal (18.5- 24.9) Over weight (25.0-29.9) Obese (≥ 29,9) |

27.0 ±6.7 19 137 99 103 |

5.30 38.10 27.70 28.90 |

||

| Characteristics of household head | ||||

| Age of household head | 8 18 394 |

1.70 4.30 94.00 |

||

| Less than or equal to 40years | ||||

| 41 - 64years 65 years and above | ||||

| Sex of household head Male Female |

282 138 |

67.1032.90 | ||

| Educational level of household head Primary Secondary Tertiary |

296 93 30 |

70.60 22.20 7.20 |

||

| Characteristics of household | ||||

| Community type Peri urban Rural |

331 89 |

78.80 21.20 |

||

| Size of family Less than 3 3-5 6 or more |

112 142 166 |

26.70 33.70 39.60 |

||

| Toilet facility type *Improved Toilet Facility *Unimproved Toilet Facility |

336 84 |

80.20 19.80 |

||

| Water source ^Improved Water Source ^Unimproved water Source |

404 16 |

96.20 3.82 |

||

| Waste disposal Burning Indiscriminate Disposal Collection. |

156 225 36 |

37.20 53.70 8.60 |

||

| Wealth index Lower class Middle class Upper class |

284 107 29 |

67.80 25.30 6.90 |

||

| Charcoal | Wood fuel | LPG | Chi-square | P-value | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Characteristics of Primary Cook | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 12 (44.4) | 13 (48.2) | 2 (7.4) | 8.7782 | 0.019b** |

| Female | 80 (20.4) | 254 (64.6) | 59 (15.0) | ||

| Age of primary cook | |||||

| Less than 40 | 4 (23.5) | 10 (58.8) | 3 (17.7) | 11.1562 | 0.427b |

| 41-64years | 24 (25.0) | 60 (62.5) | 12 (12.5) | ||

| 65 years and above | 7 (26.9) | 14 (53.9) | 5 (19.2) | ||

| Civil Status | |||||

| Single | 32 (15.5) | 136 (65.7) | 39 (18.8) | 14.2701 | 0.001a** |

| Married | 60 (28.2) | 131 (61.5) | 22 (10.3) | ||

| BMI | |||||

| Underweight | 4 (15.4) | 16 (61.5) | 6 (23.1) | 9.146 | 0.204b |

| Normal BMI | 27 (17.9) | 99 (65.5) | 25 (16.6) | ||

| Overweight | 31 (25.8) | 70 (58.4) | 19 (15.8) | ||

| Obese | 30 (24.4) | 82 (66.7) | 11 (8.9) | ||

| Education level of primary cook | |||||

| Primary | 22 (19.0) | 81 (69.8) | 13 (11.2) | 30.5222 | <0.001b |

| Secondary | 19 (33.9) | 33 (59.0) | 4 (7.1) | ||

| Tertiary | 8 (66.7) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Religion of primary cook | |||||

| Christianity | 35 (30.2) | 63 (54.3) | 18 (15.5) | 12.1612 | 0.075b |

| Muslim | 52 (19.2) | 178 (65.7) | 41 (15.1) | ||

| Agonist | 3 (12.0) | 21 (84.0) | 1 (4.0) | ||

| Ethnicity of primary cook | |||||

| Ga Adagmbe | 21 (16.3) | 91 (70.5) | 17 (13.2) | 16.0099 | 0.024b |

| Ewe | 57 (23.8) | 141 (58.7) | 42 (17.5) | ||

| Akan | 9 (40.9) | 12 (54.5) | 1 (4.6) | ||

| Others | 5 (17.2) | 23 (79.3) | 1 (3.5) | ||

| Household Head Characteristics | |||||

| Sex of household head | |||||

| Male | 73 (25.9) | 172 (61.0) | 37 (13.1) | 9.2732 | 0.016a |

| Female | 19 (13.8) | 95 (68.8) | 24 (17.4) | ||

| Educational level of household head | |||||

| Primary | 16 (15.7) | 76 (74.5) | 10 (9.8) | 59.3349 | <0.001b |

| Secondary | 27 (36.0) | 43 (57.3) | 5 (6.7) | ||

| Tertiary | 16 (57.1) | 11 (39.3) | 1 (3.6) | ||

| Household Characteristics | |||||

| Household average monthly income | |||||

| Less or equal GHS 250-500 | 15 (15.0) | 62 (62.0) | 23 (23.0) | 18.8999 | 0.022b |

| GHS 501-GHS 1000 | 37 (23.4) | 97 (61.4) | 24 (15.2) | ||

| GHS 1001 and above | 13 (36.1) | 20 (55.6) | 3 (8.3) | ||

| House ownership | |||||

| Sole Ownership | 23 (18.8) | 71 (58.2) | 28 (23.0) | 16.4935 | 0.004a |

| Family house | 21 (17.1) | 84 (68.3) | 18 (14.6) | ||

| Rented | 48 (27.4) | 112 (64.0) | 15 (8.6) | ||

| Dwelling | |||||

| Single | 20 (13.8) | 9 (62.1) | 35 (24.1) | 23.2729 | 0.001b |

| Multiple | 2 (16.7) | 90 (75.0) | 1 (8.3) | ||

| Enclosed | 11 (29.7) | 24 (64.9) | 2 (5.4) | ||

| Size of family | |||||

| Less than 3 | 37 (32.7) | 65 (57.5) | 11 (9.7) | 29.9784 | <0.001a |

| 5-Mar | 40 (20.2) | 138 (69.7) | 20 (10.1) | ||

| 6 or more | 15 (13.8) | 64 (58.7) | 30 (27.5) | ||

| Study population characteristics |

LPG OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

Charcoal OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Sex of primary cook | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.12 (0.01, 2.54) | 0.175 | 0.35 (0.02, 5.70) | 0.462 |

| Age range of primary cook | ||||

| 40years and less | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 41 – 59years | 0.69 (0.21, 2.22) | 0.530 | 0.77 (0.30, 1.97) | 0.581 |

| 60years and above | 0.53 (0.05, 6.10) | 0.610 | 0.67 (0.09, 5.22) | 0.705 |

| Marital status of primary cook | ||||

| Married | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Single | 0.56 (0.13, 2.38) | 0.436 | 0.62 (0.19, 1.99) | 0.426 |

| Ever married | 0.12 (0.02, 0.71) | 0.020 | 0.18 (0.04, 0.83) | 0.027 |

| Religion of primary cook | ||||

| Christian | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Moslem | 0.25 (0.00, 112.20) | 0.657 | 0.64 (0.00, 2.31) | 0.883 |

| Agnostic | 0.96 (0.04, 21.84) | 0.980 | 1.40 (0.09, 21.93) | 0.810 |

| Ethnicity of primary cook | ||||

| Ga Adamgbe | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Ewe | 0.73 (0.18, 2.88) | 0.648 | 0.43 (0.14, 1.30) | 0.136 |

| Krobo | 0.19 (0.02, 1.62) | 0.129 | 0.53 (0.10, 2.77) | 0.451 |

| Other | 5.09 (0.01, 2084.02) | 0.596 | 4.98 (0.01, 17.16) | 0.590 |

| Dwelling | ||||

| Single Occupancy | 1.00 | 1,00 | ||

| Multiple Occupancy | 2.06 (0.68, 6.20) | 0.200 | 1.36 (0.55, 3.35) | 0.505 |

| Enclosed Dwelling | 2.37 (0.36, 15.37) | 0.367 | 1.64 (0.33, 8.08) | 0.541 |

| Educational level of primary cook | ||||

| Primary | 1.00. | 100. | ||

| Secondary | 1. 70 (0.54, 5.33) | 0.363 | 2.11 (0.79, 5.56) | 0.132 |

| Tertiary | 0.047 (0.00, 3.63) | 0.168 | 0.012 (0.000, 1.033) | 0.052 |

| Relationship to household head | ||||

| Head of house | 1..00 | 1.00 | ||

| Married to household head | 0.70 (0.12, 4.10) | 0.696 | 1.35 (0.28, 6.52) | 0.711 |

| Partner | 0.39 (0.03, 5.88) | 0.499 | 0.64 (0.07, 6.41) | 0.708 |

| Other relative | 1.04 (0.04, 24.19) | 0.982 | 0.97 (0.05, 17.61) | 0.981 |

| Age of household head | ||||

| 40years and less | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 41 – 59years | 0.99 (0.03, 36.44) | 0.995 | 15.00 (0.36, 62.07) | 0.154 |

| 60years and above | 0.74 (0.06, 8.56) | 0.811 | 12.93 (0.79, 21.26) | 0.073 |

| Sex of household head | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00. | ||

| Female | 0.85 (0.14, 5.29) | 0.858 | 2.41 (0.52, 11.08) | 0.260 |

| Educational level of household head | ||||

| Primary | 100. | 100 | ||

| Secondary | 2.38 (0.69, 8.11) | 0.167 | 0.91 (0.34, 2.45) | 0.853 |

| Tertiary | 11.66 (1.57,12.08) | 0.031 | 12.76 (0.16, 97.09) | 0.252 |

| House ownership | ||||

| Sole Ownership | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Family house | 1.12 (0.29, 4.30) | 0.867 | 2.05 (0.71, 5.88) | 0.183 |

| Rented | 1.51 (0.44, 5.19) | 0.514 | 2.07 (0.74, 5.80) | 0.164 |

| Occupation of household head | ||||

| Trader | 1.00. | 1.00 | ||

| Farmer | 0.22 (0.05, 1.04) | 0.057 | 0.44 (0.13, 1.51) | 0.191 |

| Artisan | 0.55 (0.10, 2.94) | 0.482 | 0.61 (0.14, 2.63) | 0.509 |

| Employed | 0.63 (0.01, 3.97) | 0.622 | 0.96 (0.19, 4.98) | 0.963 |

| Unemployed | 0.92 (0.18, 4.53) | 0.920 | 0.50 (0.13, 1.96) | 0.319 |

| Household average monthly Income | ||||

| Ghc 250 or less | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Ghc 251 – 1000 | 0.84 (0.12, 5.87) | 0.860 | 0.46 (0.11, 1.99) | 0.300 |

| Greater than or equal to Ghc 1001 | 3.18(0.29, 34.51) | 0.341 | 2.64 (0.39, 17.89) | 0.319 |

| Reluctant | 0.09 (0.00, 2.93) | 0.177 | 0.36 (0.04, 3.58) | 0.386 |

| Waste disposal | ||||

| Burning | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Indiscriminate disposal | 1.07 (0.38, 3.00) | 0.894 | 1.14(0.49, 2.66) | 0.768 |

| Collection | 8.95 (1.20, 66.48) | 0.032 | 0.94 (0.16, 5.66) | 0.947 |

| Family size | ||||

| 5members or less | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 6 members or more | 0.18 (0.06, 0.51) | 0.001 | 0.48 (0.21, 1.09) | 0.081 |

| ^Water sources | ||||

| Improved water source | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unimproved water source | 0.53 (0.07, 3.79) | 0.524 | 0.17 (0.03, 0.98) | 0.047 |

| *Toilet facilities | ||||

| Improved toilet facility | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unimproved toilet facility | 0.23(0.06,0.86) | 0.028 | 0.46(0.17,1.25) | 0.130 |

| #Wealth Index | ||||

| Relatively poor household | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Relatively rich household | 3.65 (1.48,9.03) | 0.005 | 11(2.62,46.26) | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).