1. Introduction

The research focuses on exploring the fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equation with the initial-boundary value

is a bounded convex polygonal domain.

is boundary of

.

.

is known initial function.

,

satisfying

for some positive constants

,

,

,

and

.

is a positive constant.

adheres to the properties of Lipschitz continuity, implying the existence of a positive constant

satisfying

For simplicity, we assume that

in the following theoretical analysis.

The fourth-order parabolic equations are commonly used to describe higher-order physical behaviors, such as considering the internal damping or viscoelastic properties of materials. Within the category of fourth-order parabolic equations, models such as the Cahn-Hilliard equation [

1,

2], fourth-order reaction-diffusion equation [

3,

4], and the Swift-Hohenberg equation [

5] are included. Due to the inclusion of higher-order derivatives, solving and analyzing these kinds of equations is usually more complex and often requires the use of numerical methods. Currently, various numerical methods have been employed to solve fourth-order parabolic equations. For example, finite element (FE) method [

1,

6,

7], mixed finite element method (MFE) [

3,

8,

9,

10], discontinuous space-time MFE method [

11,

12], two-grid MFE method [

13,

14], weak galerkin FE method [

2,

15], finite difference method [

16], implicit compact difference method [

17,

18,

19,

20], cubic spline method [

21], blow-up [

22,

23,

24,

25] and so on. In the paper, the MFE method is employed to study the fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equation for spatial analysis. The method of time discretization is the Crank-Nicolson (CN) scheme.

A prevalent challenge in addressing high-order partial differential equations (PDEs) through the MFE method is the rapid escalation of unknown dimensions when dealing with coupled equations, often resulting in a doubling of the data volume processed. Such significantly elevated dimensions not only heighten memory requirements but also substantially escalate computational costs. In practical scenarios, this increased computational burden can pose a significant barrier to solving complex PDE problems. An effective strategy to mitigate these challenges involves the implementation of order reduction techniques. The primary objective of these techniques is to minimize the number of variables considered during the solution process using mathematical methods, thereby alleviating computational demands while preserving as much as possible a good approximation quality. Currently, several effective numerical reduced-order methods have gained widespread application, including the POD method [

26,

27], the spectral element method [

28] , the sparse grid method [

29], and the balanced truncation method [

30] .

Certainly, integrating POD technology with diverse numerical methods can effectively address a range of PDEs. It is the most widely utilized method for dimensionality reduction and has been attracting increasing attention. [

31] and [

32] combined the compact difference method and POD technique to study the fourth-order parabolic equation. Zhao and Piao [

33] studied the KDV-RLW-Rosenau equation using the POD method in conjunction with B-spline Galerkin FE formulations. In [

34], the heat equation was addressed using the POD reduced-order methods and the two-step backward differentiation formula (BDF2). Janes and Singler [

35] solved the damped wave equation by the POD method and the second difference quotients (DDQs). He et al. [

36] employed a space-time FE method that integrates a POD-based extrapolation with DG time stepping to analyze the parabolic equation. Lu et al. [

37] merged the POD method with a collocation approach using local radial basis functions (RBFs) to address time-dependent nonlocal diffusion problems.

For the POD-based FE and MFE reduced-dimension models, there are two existing methods. The first involves establishing optimized models which reduce the dimensions of the FE or the MFE subspaces. For further references, please consult [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. The second, introduced by Luo et al. in 2020, presented an innovative strategy for dimension reduction of CNFE [

45,

46] and CNMFE [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51] solution coefficient vectors. To our understanding, no existing literature has documented simplifying the solution coefficient vectors of CNMFE scheme used POD technology in solving fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equations. The paper primary objective presents a rapid algorithm capable of solving fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equations.

The research is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses the CNMFE scheme, detailing its uniqueness, stability, and convergence.

Section 3 dedicates to construct a POD-based RDCNMFE matrix model, while also analyze its uniqueness, stability, and error estimates. In

Section 4, we perform numerical simulations on 2D fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equations. Finally,

Section 5 summarizes the key results and conclusions of the research.

2. The CNMFE Method for the Fourth-Order Variable Coefficient Parabolic Equation

2.1. The CNMFE Scheme

In this paper, the Sobolev spaces and the associated norms adhere to the conventional definitions commonly found in existing literature [

52]. To construct the CNMFE scheme for the fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equation (

1), we begin by introducing a diffusion term defined as

. This introduces a pair of lower-order equations

Applying Green’s formula, we obtain the mixed weak form of (4) as provided below.

Problem 1.

Find : , such that

Let

represent the quasi-uniform triangulation on

. The FE subspace

is defined as the following span of the orthonormal basis

where

is a polynomial space of

degree.

For a positive integer

N, define

,

,

and

. Hence, Problem 1 can be reformulated at time

as follows.

The equivalent equation is that

where

When , define the CNMFE approximations of as . Therefore, we can formulate the CNMFE scheme of Problem 1 using the form below.

Problem 2.

For , find , such that

Remark 1. [

50], Formula (12) Using the linearized term

it is evident that equation (12) structured as a linear scheme.

2.2. The Uniqueness, Stability and Error Estimates of the CNMFE Solutions

Utilizing the orthonormal basis of the FE space

, the CNMFE approximations

to Problem 2 can be expressed as

in which

is the orthonormal basis function vector.

and represent the unknown CNMFE solution coefficient vectors. With the solutions defined in (14), the matrix-form of Problem 2 is as follows.

Problem 3.

For , find and that satisfy

where

and

Theorem 1. Given that is small enough, the Problem 3 has the unique CNMFE solutions .

Proof of Theorem 1. Problem 3 can alternatively be expressed as

where

denotes the

identity matrix, and

stands for a zero column vector of

.

where represents the zero matrix. Because is small enough, is invertible. Hence, the coefficient matrix of (16) is invertible, then there exists the unique solutions for Problem 3. □

It is necessary to discuss the characteristics of and in Problem 3 for establishing the stability of the CNMFE solutions.

Lemma 1. [

53], Lemma 1.19 Matrices

and

are positive definite and satisfy the following properties

Theorem 2. The CNMFE solutions have unconditional stability.

Proof of Theorem 2.

Inserting the second equation of (19) into the first, and considering that

is positive definite, we obtain

Letting

, and taking the inner product of (20) and

, we have

Then, two sides of (21) are that

and

Combining lemma 1 with (3), and considering that

and

are bounded, we obtain

Combining (22), (23) and (24), we have

Multiplying (25) by

, summating from 2 to

n and noting that

, we have

We apply the Gronwall inequality to (26) to obtain

From (27) and (28), we get

Given that

, it easily follows

As indicated by (29) and (30), the CNMFE solution coefficient vectors are bounded, implying that the CNMFE solutions retain unconditional stability.

□

It is essential to define the projection operators and for analyzing the convergence of the CNMFE solutions.

Lemma 2.

The projection , defined by

with the following estimates

Lemma 3.

The projection , defined by

with the following estimates

Errors can be divided for simplifying theoretical analysis as follows

Subtracting (12) from (8) and using (31) and (34) at

, the error equations are derived as

The following lemma is presented for deriving error estimates. The lemma can be straightforwardly obtained through Taylor expansion.

Lemma 4. [

54]

and

satisfy the following estimates

Based on Lemmas 2, 3 and 4, we can establish the theorems that concern the fully discrete error estimates for the Crank-Nicolson method.

Theorem 3.

Given that the solutions to (5) adhere to regularity conditions with , , . It follows that a positive constant C exists, which does not depend on h and , satisfying

in which .

Proof of Theorem 3. Taking

and

in (39) and (40), respectively, we obtain

Subtracting (45) from (44), we have

Multiplying (46) by

, summating from

, and considering that

and

, we obtain

For the nonlinear term

, from reference [

50], we have

Substituting (48) into (47), and using the Gronwall lemma and

, we get

Substituting (50) and (51) into (49) and combining Lemma 4, we obtain

The proof of (43) is effectively completed combining Lemma 2, 3, (52), and the triangle inequality.

□

Theorem 4.

With and , given that the solutions to (5) adhere to regularity conditions with , , . It follows that a positive constant C exists, which does not depend on h and , satisfying

Proof of Theorem 4.

Taking

and

in (39) and (54), respectively, we obtain

Substituting (58) into (56) yields

Multiplying (59) by

, summating from

and employing (50) and (51), we get

Using the Gronwall Lemma and (48),we have

Substitute (52) and Lemma 4 into (61), we get

We complete the proof combining Lemma 2, 3, (62) and the triangle inequality. □

3. The POD-Based RDCNMFE Method for the Fourth-Order Variable Coefficient Parabolic Equation

3.1. Structure of POD Bases

Initially, computing the first

-step coefficient vectors

by Problem 3, the snapshot matrices

and

are generated. Next, we compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of matrices

. Organize the eigenvalues as

. The eigenvectors form the eigenmatrix

. Lastly, the initial

d vectors of

are selected as POD bases

, such that

in which

and

for vector

. For

, it follows that

, the nth component being 1, named unit vectors. Consequently, are optimal POD bases.

Remark 2. It is obvious that the order of the matrices is significantly greater than the order of the matrices . However, their positive eigenvalues are same, we can compute the first d eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the matrices . Then, we can derive the eigenvectors for through the relationships . This approach facilitates the creation of POD bases .

3.2. The RDCNMFE Scheme

Initially, we let and , and define the RDCNMFE solution coefficient vectors as follows: and . Next, the first RDCNMFE solution coefficient vectors are promptly derived using and , for , as outlined in section 3.1. Finally, for subsequent time steps , we employ and , replacing the original CNMFE solution vectors in Problem 3. This allows us to develop the following RDCNMFE matrix scheme.

Problem 4.

Find and , such that

Here, denotes the first solution vectors of Problem 3. The definitions of matrix , , and vector , along with the FE basis vectors are detailed in section 2.2.

3.3. The Uniqueness, Stability and Error Estimate of the RDCNMFE Solutions

Theorem 5.

With the assumptions laid out in Theorem 3 and 4, we consider as the solutions of Problem 1, and as reduced-dimension solutions of Problem 4. Then the RDCNMFE solutions are both unique and unconditionally stable for , and have the error estimate as follows.

Proof of Theorem 5.

- (1)

-

Demonstrate the uniqueness.

For , Theorem 1 ensures that the solutions in problem 3 are unique. Consequently, the corresponding solutions , derived from the first and fourth expressions of problem 4, also have uniqueness.

For

, by applying

and

, the last three equations of Problem 4 are reformulated as

For , the solutions in Problem 3 are unique. Because adhere to the identical structure as problem 3, the solutions for also have uniqueness.

- (2)

-

Analyse the stability.

(i) When .

Applying Theorem 2 and considering the orthonormality of the vectors in

and

, it follows that

(ii) When .

From the positive definite symmetry of matrix

, (68) can be reformulated as

Substituting (69) into (72), and since

is positive definite, we obtain

Letting

, and taking the inner product of (73) and

, we have

Then, two sides of (74) are that

and

Similar to (24), we obtain

Combining (75), (76) and (77), we have

Multiplying (78) by

and summating from 2 to

n, it follows that

Noting that

putting (80) into (79), we have

Using the Gronwall inequality for (81),

Because of

, we get

Based on (71) and (85), we can conclude that the solutions exhibit unconditional stability.

- (3)

-

Discuss the error estimates.

(i) For .

According to (64) and (65), and considering

, we obtain

(ii) For .

Defining

and

, and combining (19), (72) and (69), we obtain

Putting (88) into (87), and since

is positive definite, we have

Letting

, we obtain

Taking the inner product of (90) and

,

Then, two sides of (91) are that

and

Using Lemma 1 and (3), we can estimate the first term of (93) as follows

Combining (92), (93) and (94), we have

Multiplying (95) by

and summating from

to

, it follows that

Putting (97) into (96), from (64) and (65), we have

Applying the Gronwall’s inequality for (98),

Because of

, we have

Combining the triangle inequality, with Theorem 3 and 4, (86) and (102), we obtain

□

4. The Numerical Experiments for the Fourth-Order Parabolic Equations

The efficiency of the proposed method is validated by two numerical examples. We compare the reduced-dimension scheme with the standard CNMFE scheme in terms of errors, convergence orders, and CPU runtime. For the purpose of analysis, we conduct experiments on the specified fourth-order parabolic equation.

Solving Problem 3 gets the standard CNMFE solutions . In order to get the RDCNMFE solutions , the four steps are as follows.

- Step 1:

In order to generate the snapshot matrices and , the initial CNMFE solution vectors are calculated out by Problem 3.

- Step 2:

Calculate the eigenvalues of the matrix and arrange them in descending order, along with their corresponding eigenvectors .

- Step 3:

By calculating, it is observed that . From the matrix , the first 6 eigenvectors can be selected. Applying the formula , we construct the POD bases .

- Step 4:

Inserting the result into Problem 4 and calculating the RDCNMFE solutions.

Example 1.

We consider the model in with the exact solution . Choosing , , the source term is

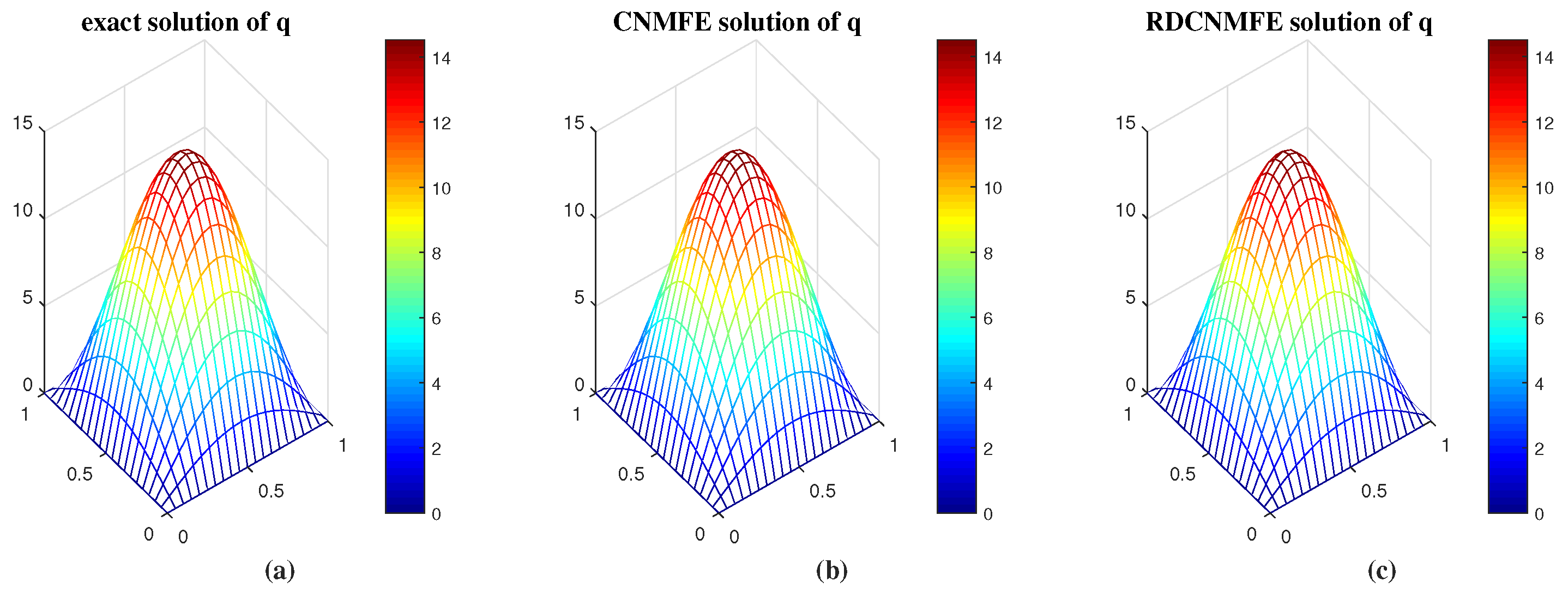

Since , the exact solution of q is .

When

, with

and

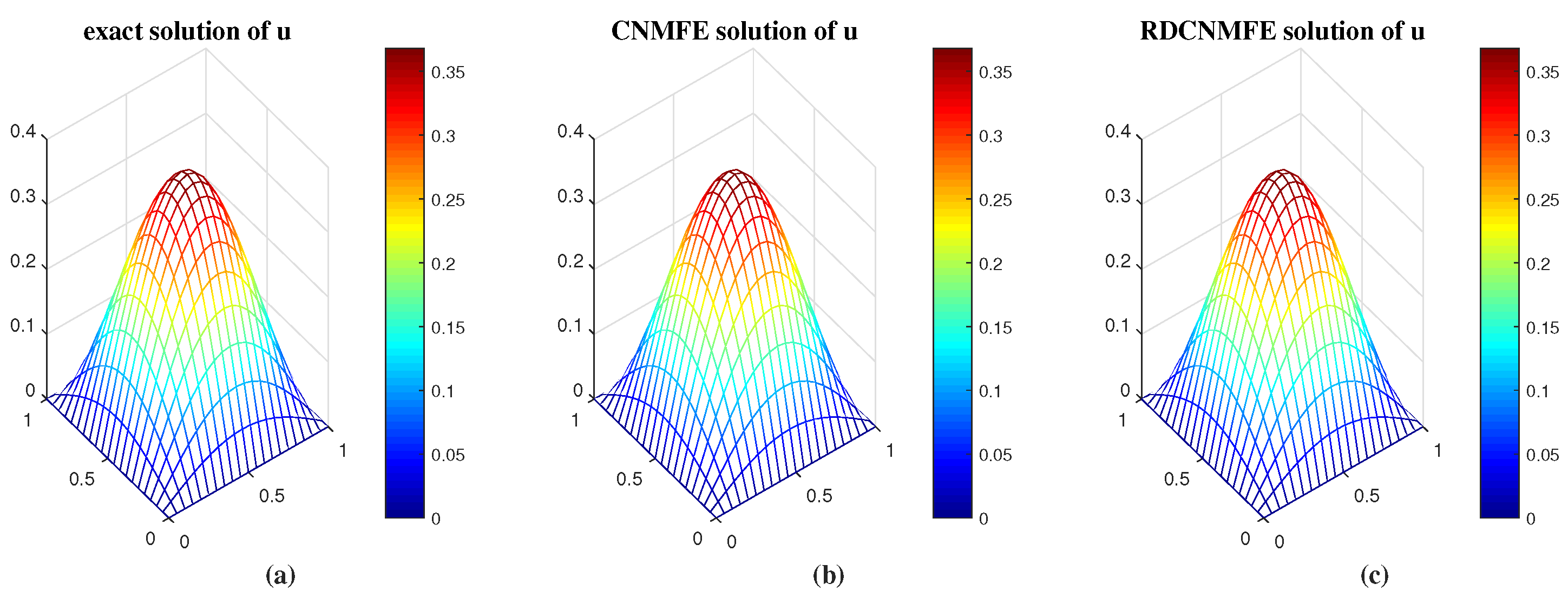

, we get the standard CNMFE solutions and RDCNMFE solutions. They are compared with the exact solutions, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. Obviously, both methods simulate the exact solutions very well.

When

and

, so as to enable easier comparison, we use both methods to compute the

error and convergence order of

, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

When

, with

and

, we record the

error obtained and the CPU runtime required using both methods to further examing the efficacy of the POD-based RDCNMFE method, as shown in

Table 3. The data indicates that both methods obtain the same

errors. With each incremental second, the conventional CNMFE method increases by approximately 260 seconds, whereas the RDCNMFE method only increases just over 10 seconds.

Example 2.

We explore the model in with the exact solution . Letting , , the source term is

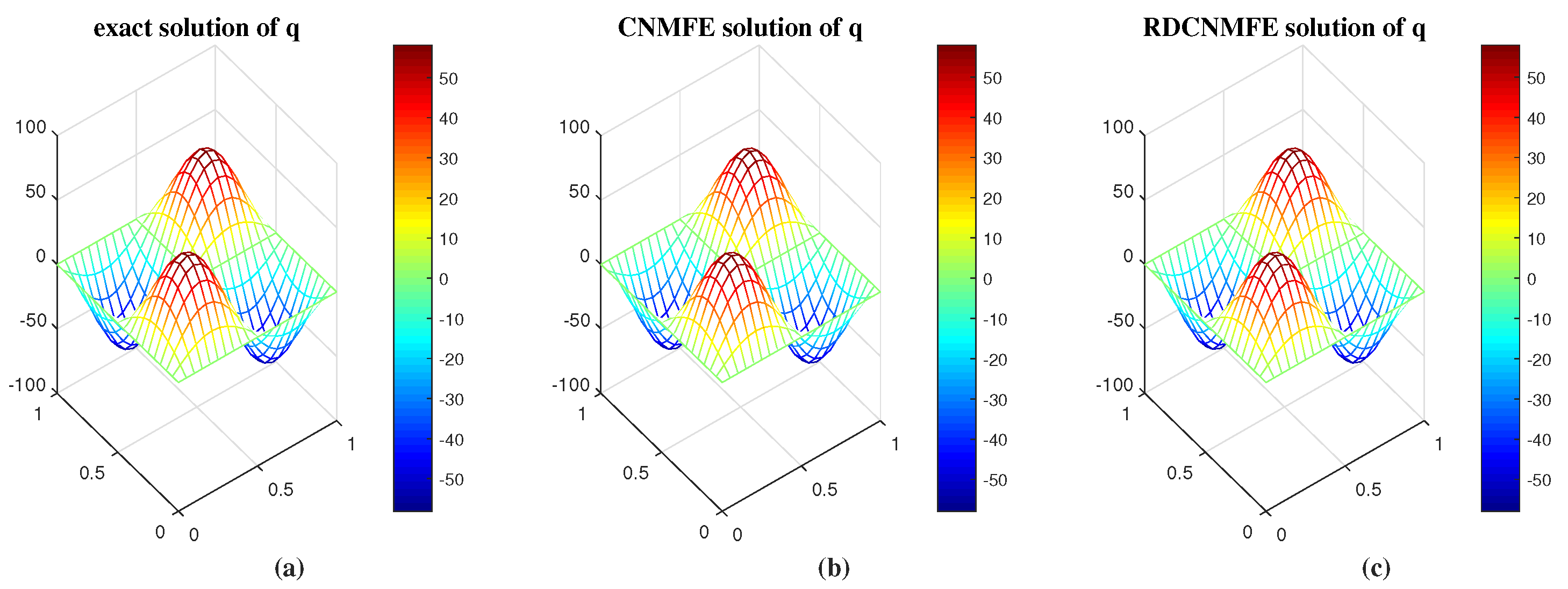

The exact solution of q is .

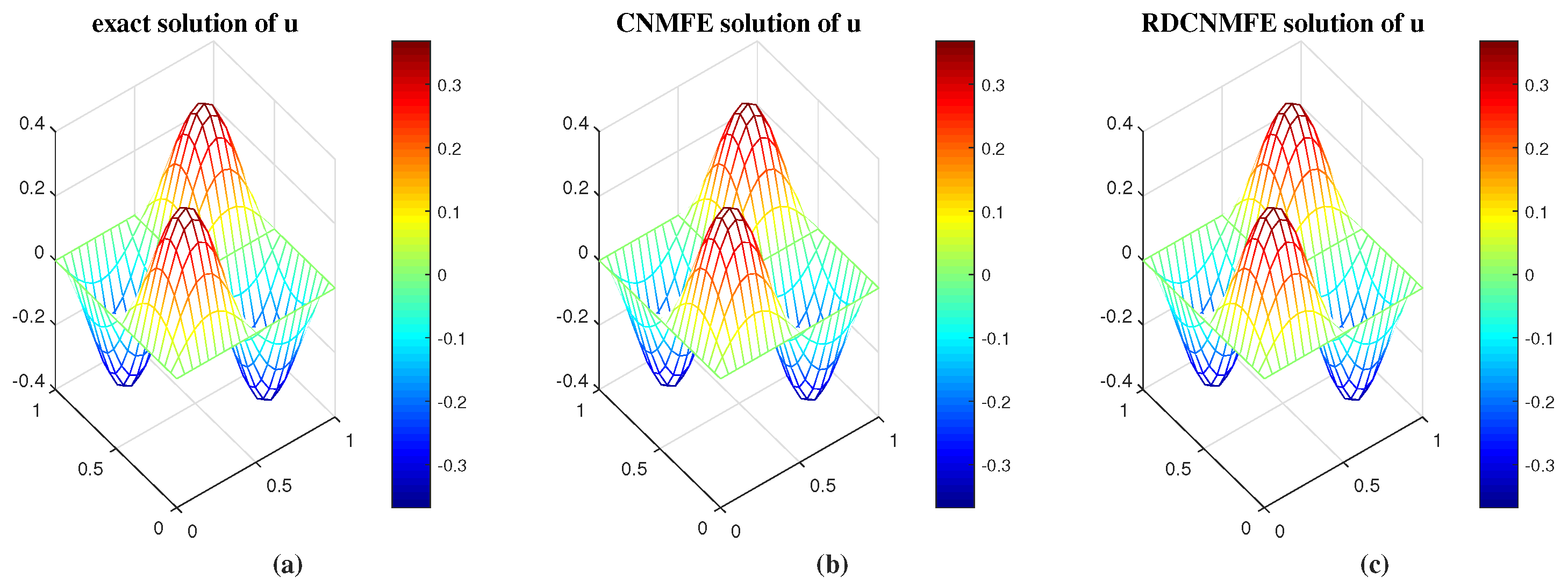

When

, setting

and

, we employ the CNMFE and RDCNMFE methods to obtain the numerical solutions for equation

that has the noted source term

. Both solutions of

are compared with the exact solutions. It can be seen clearly from

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 that both solutions closely approximate the exact solutions.

When

, setting

and

, we compute the CNMFE and RDCNMFE solutions of

. Then we get the

errors and convergence orders of both methods, as shown in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

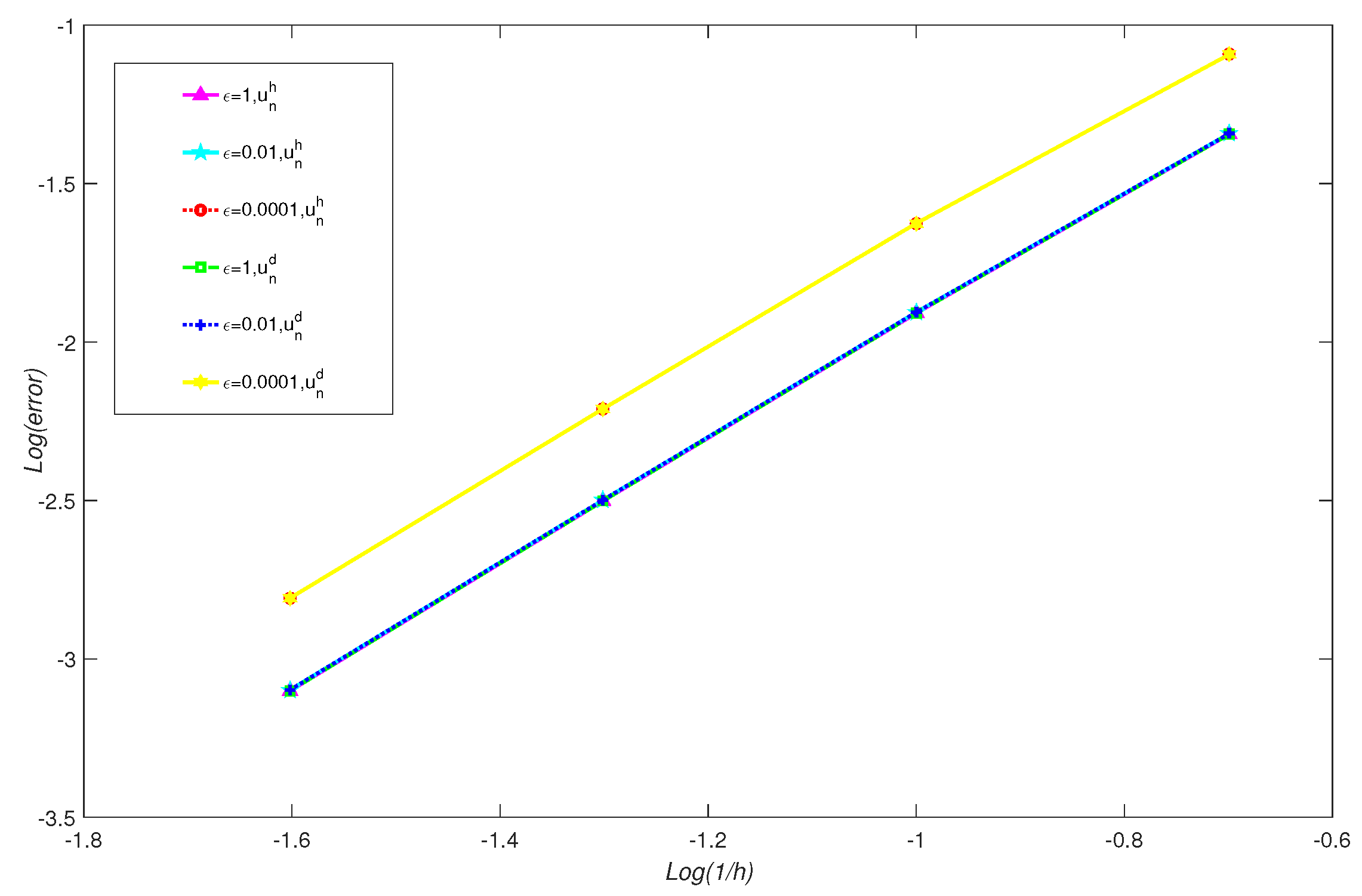

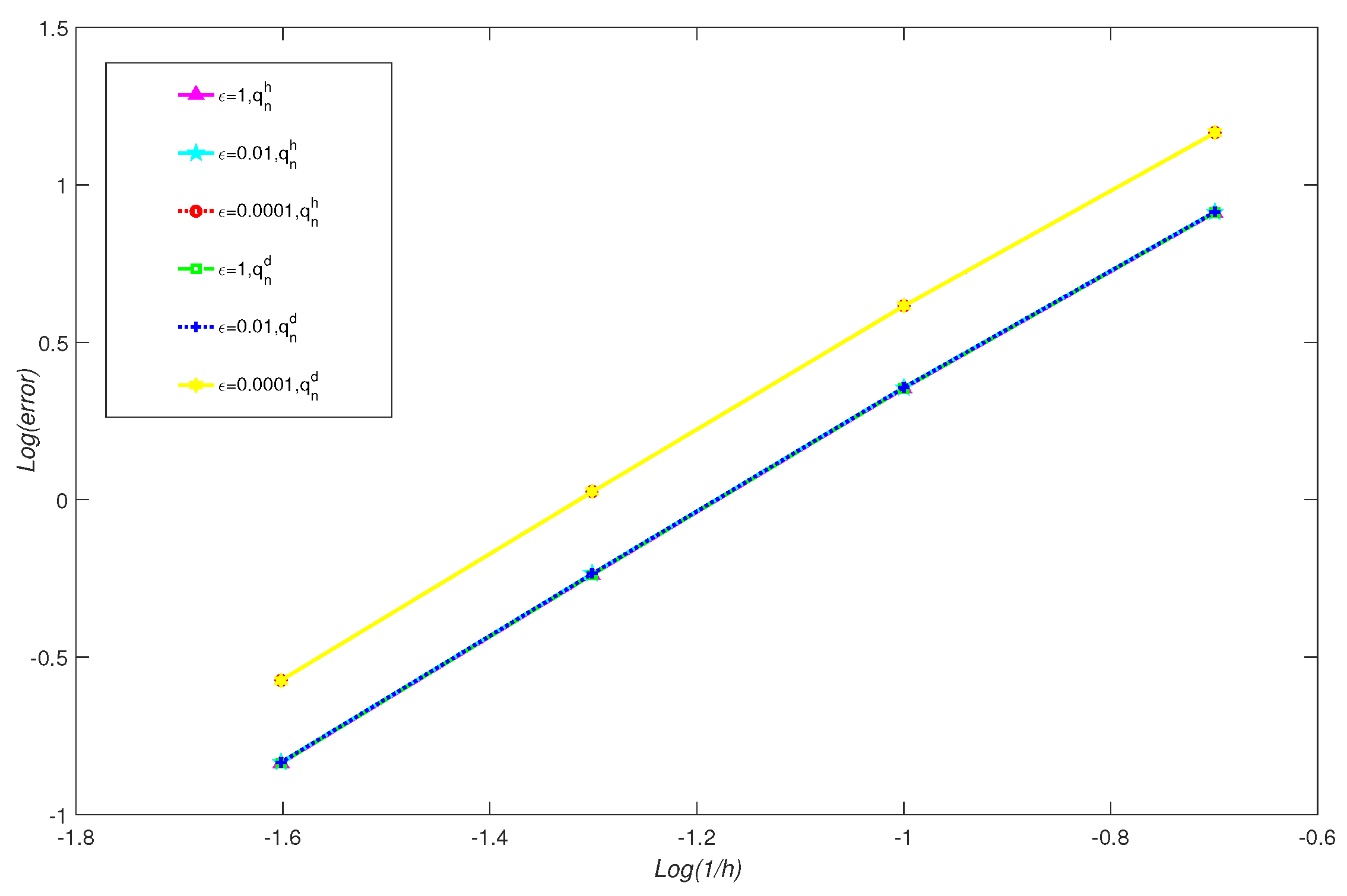

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 provide the comparison of error results of

when

. The figures demonstrates that when

is set to a very small value, such as

, although the solutions obtained by both methods are convergent, their associated errors tend to increase.

For purpose of demonstrating the effectiveness of the POD-based reduce-dimension method, we need to compare the CPU runtime of both methods. When

, with

and

, we calculate the CNMFE and RDCNMFE solutions. Then we recorded the CPU runtime required using both methods in

Table 6. Evidenced in

Table 6, using the CNMFE method, the CPU runtime increases by about 130 seconds for every additional

second. However, applying the RDCNMFE method, it takes just a few seconds for every added

second. The significant reduction in CPU runtime using the reduced-dimension method can be attributed to the difference in degrees of freedom at each time node. Specifically, the standard CNMFE method is calculated with

degrees of freedom, while the RDCNMFE method just has

degrees of freedom.

From the numerical results obtained from the above provided examples, it is evident that the RDCNMFE method based on POD serves as an efficient numerical technique for addressing the fourth-order variable coefficient parabolic equations.

5. Conclusions

In this research, our focus was on reducing dimension of solution coefficient vectors employing the CNMFE method combined with POD technique for the nonlinear variable coefficient fourth-order parabolic equation. Firstly, we developed a CNMFE scheme for the equations. We extensively analyzed the uniqueness, stability, and error estimates of the CNMFE solutions. Subsequently, the POD bases was derived from the initial CNMFE solution coefficient vectors. We constructed a reduced-dimension matrix model and applied conventional FE analysis techniques in order to study the uniqueness, stability and convergence of the RDCNMFE solutions. Furthermore, we conducted detailed numerical experiments to compare the efficacy of both methods. The RDCNMFE method exhibited a reduced number of degrees of freedom at each time nodes compared to the conventional CNMFE method. This feature significantly reduces the computational load of the RDCNMFE method, thereby decreasing the runtime. Notably, this study has streamlined the calculations by linearizing the nonlinear terms, thereby eliminating repetitive numerical iterations. Thus, the RDCNMFE method emerges as an innovative and efficient numerical approach for addressing complex nonlinear PDEs.

In the following study, the method will be extended to more high-order PDEs, such as the fractional fourth-order PDEs, the Schrödinger equation with fourth-order disturbance term and so on. Additionally, we believe this method can be adapted to more complex problems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and H.L.; methodology, X.C.; numerical simulation, X.C.; formal analysis, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C.; validation, X.C. and H.L.; writing—review, H.L.; supervision, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12161063) and the Program for Innovative Research Team in Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (NMGIRT2207).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors for their invaluable comments, which greatly refined the content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| POD |

proper orthogonal decomposition |

| CNMFE |

Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element |

| RDCNMFE |

reduced-dimension Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element |

References

- Zhang, T. Finite element analysis for Cahn-Hilliard equation. Math. Numer. Sin. 2006, 28, 281-292. (in Chinese).

- Chai S, Wang Y , Zhao W ,et al. A C0 weak Galerkin method for linear Cahn-Hilliard-Cook equation with random initial condition. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022, 126659.

- Danumjaya, P., Pani, A.K. Mixed finite element methods for a fourth order reaction diffusion equation. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2012, 28, 1227-1251. [CrossRef]

- Tian J., He M., Sun P. Energy-stable finite element method for a class of nonlinear fourth-order parabolic equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2024, 438, 115576. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X., Yang R., Qi R.J., Sun H. Energy stability and convergence of variable-step L1 scheme for the time fractional Swift-Hohenberg model. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2024, 27, 82-101. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.W., Blowey, J.F., Garcke, H. Finite element approximation of a fourth order nonlinear degenerate parabolic equation. Numer. Math. 1998, 80, 525-556. [CrossRef]

- Du S., Cheng Y., Li M. High order spline finite element method for the fourth-order parabolic equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2023, 184, 496-511. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y., Fang Z.C., Li H., et al. A coupling method based on new MFE and FE for fourth-order parabolic equation. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2013, 43, 249-269. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, H., He, S., Gao, W., Fang, Z.C. H1-Galerkin mixed element method and numerical simulation for the fourth-order parabolic partial differential equations. Math. Numer. Sin. 2012, 34, 259-274. (in Chinese).

- Shi D.Y., Shi Y.H., Wang F.L. Supercloseness and the optimal order error estimates of H1-Galerkin mixed element method for fourth order parabolic equation. Math. Numer. Sin. 2014, 36, 363-380. ( in Chinese).

- Li H., Guo Y. The space-time mixed finite element method for fourth order parabolic problems. Journal of Inner Mongolia University (Natural Science Edition) 2006, 37, 19-22. (in Chinese).

- He S., Li H. The mixed discontinuous space-time finite element method for the fourth order linear parabolic equation with generalized boundary condition. Math. Numer. Sinica. 2009, 31, 167-178. (in Chinese).

- Liu Y., Du Y., Li H., et al. A two-grid mixed finite element method for a nonlinear fourth-order reaction-diffusion problem with time-fractional derivative. Comput. Math. Appl. 2015, 70, 2474-2492. [CrossRef]

- Yin B.L., Liu Y, Li H., et al. TGMFE algorithm combined with some time second-order schemes for nonlinear fourth-order reaction diffusion system. Results. Appl. Math. 2019, 4, 100080. [CrossRef]

- Chai S., Zou Y., Zhou C., et al. Weak Galerkin finite element methods for a fourth order parabolic equation. Numer. Meth. Part. D. E. 2019, 35, 1745-1755. [CrossRef]

- Zhao X., Liu F., Liu B. Finite difference discretization of a fourth-order parabolic equation describing crystal surface growth. Appl. Anal. 2015, 94, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty R.K., Kaur D., Singh S. A class of two- and three-level implicit methods of order two in time and four in space based on half-step discretization for two-dimensional fourth order quasi-linear parabolic equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 352, 68-87.

- Kaur D., Mohanty R.K. Highly accurate compact difference scheme for fourth order parabolic equation with Dirichlet and Neumann boundary conditions: Application to good Boussinesq equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2020, 378, 125202.

- Gao G., Huang Y., Sun Z. Pointwise error estimate of the compact difference methods for the fourth-order parabolic equations with the third Neumann boundary conditions. Math. Meth. Appl. Sci. 2023, 47, 634-659. [CrossRef]

- Kaur D., Mohanty R.K. High-order half-step compact numerical approximation for fourth-order parabolic PDEs. Numer. Algorithms. 2024, 95, 1127-1153. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S., Sharma N. A fast computational technique to solve fourth-order parabolic equations: application to good Boussinesq, Euler-Bernoulli and Benjamin-Ono equations. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2024, 101, 194-216. [CrossRef]

- Ishige K., Miyake N., Okabe S. Blowup for a Fourth-Order Parabolic Equation with Gradient Nonlinearity. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 2020, 52, 927-953. [CrossRef]

- Ding H., Zhou J. Infinite Time Blow-Up of Solutions to a Fourth-Order Nonlinear Parabolic Equation with Logarithmic Nonlinearity Modeling Epitaxial Growth. Mediterr. J. Math. 2021, 18, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Shao X., Tang G. Blow-up phenomena for a class of fourth order parabolic equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2021, 505, 125445. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J., Guo B., Wang J. Global existence and blow-up of weak solutions for a fourth-order parabolic equation with gradient nonlinearity. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 2024, 75, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D. Finite element and reduced dimension methods for partial differential equations; Springer Singapore: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Luo Z.D., Chen G. Proper Orthogonal Decomposition Methods for Partial Differential Equations; Academic Press of Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2018.

- Shao W., Chen C. A fourth order Runge-Kutta type of exponential time differencing and triangular spectral element method for two dimensional nonlinear Maxwell’s equations. Appl. Numer. Math. 2025, 207, 348-369. [CrossRef]

- Zeiser A. Sparse grid time-discontinuous Galerkin method with streamline diffusion for transport equations. Part. D. E. Appl. 2023, 4, 38. [CrossRef]

- Jiang S., Cheng Y., Cheng Y., Huang Y. Generalized multiscale finite element method and balanced truncation for parameter-dependent parabolic problems. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4695. [CrossRef]

- Xu B., Zhang X., Ji D. A Reduced High-Order Compact Finite Difference Scheme Based on POD Technique for the Two Dimensional Extended Fisher-Kolmogorov Equation. IAENG Int. J. Appl. Math. 2020, 50, 474-483.

- Li Q., Chen H., Wang H. A proper orthogonal decomposition-compact difference algorithm for plate vibration models. Numer. Algorithms. 2023, 94, 1489-1518. [CrossRef]

- Zhao W., Piao G.R. A reduced Galerkin finite element formulation based on proper orthogonal decomposition for the generalized KDV-RLW-Rosenau equation. J. Inequal. Appl. 2023, 2023, 104. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Archilla B., John V., Novo J. Second order error bounds for POD-ROM methods based on first order divided differences. Appl. Math. Letters. 2023, 146, 108836. [CrossRef]

- Janes A., Singler R.J. A new proper orthogonal decomposition method with second difference quotients for the wave equation. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2025, 457, 116279. [CrossRef]

- He S., Li H., Liu Y. A POD based extrapolation DG time stepping space-time FE method for parabolic problems. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2024, 539, 128501. [CrossRef]

- Lu J., Zhang L., Guo X., Qi Q. A POD based reduced-order local RBF collocation approach for time-dependent nonlocal diffusion problems. Appl. Math. Letters. 2025, 160, 109328. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D., Li L., Sun P. A reduced-order MFE formulation based on POD method for parabolic equations. Acta. Math. Sci. 2013, 33B, 1471-1484. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q., Teng F., Luo Z.D. A reduced-order extrapolation algorithm based on CNLSMFE formulation and POD technique for two-dimensional Sobolev equations. Appl. Math. Ser. B. 2014, 29, 171-182. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D., Zhou Y.J., Yang X.Z. A reduced finite element formulation based on proper orthogonal decomposition for Burgers equation. Appl. Numer. Math. 2009, 59, 1933-1946. [CrossRef]

- Song J., Rui H. A reduced-order characteristic finite element method based on POD for optimal control problem governed by convection-diffusion equation. Comput. Meth. Appl. M. 2022, 391, 114538. [CrossRef]

- Song J, Rui H. Reduced-order finite element approximation based on POD for the parabolic optimal control problem. Numer. Algorithms. 2024, 95, 1189-1211. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D. A POD-Based Reduced-Order Stabilized Crank-Nicolson MFE Formulation for the Non-Stationary Parabolized Navier-Stokes Equations. Math. Model. Anal. 2015, 20, 346-368. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D. A POD-based reduced-order TSCFE extrapolation iterative format for two-dimensional heat equations. Bound. Value. Probl. 2015, 2015, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D. The reduced-order extrapolating method about the Crank-Nicolson finite element solution coefficient vectors for parabolic type equation. Mathematics. 2020, 8, 1261. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y., Luo Z.D. The reduced-dimension technique for the unknown solution coefficient vectors in the Crank-Nicolson finite element method for the Sobolev equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2022, 513, 126207. [CrossRef]

- Teng F., Luo Z.D. A reduced-order extrapolation technique for solution coefficient vectors in the mixed finite element method for the 2D nonlinear Rosenau equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2020, 485, 123761. [CrossRef]

- Luo Z.D. The dimensionality reduction of Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element solution coefficient vectors for the unsteady Stokes equation. Mathematics. 2022, 10, 2273. [CrossRef]

- Li Y., Teng F., Zeng Y., et al. Two-grid dimension reduction method of Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element solution coefficient vectors for the fourth-order extended Fisher-Kolmogorov equation. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2024, 536, 128168. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Li, H. The reduced-dimension method for Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element solution coefficient vectors of the extended Fisher-Kolmogorov equation. Axioms. 2024, 13, 710. [CrossRef]

- Zeng Y., Li Y., Zeng Y., et al. The dimension reduction method of two-grid Crank-Nicolson mixed finite element solution coefficient vectors for nonlinear fourth-order reaction diffusion equation with temporal fractional derivative. Commun. Nonlinear. Sci. 2024, 107962.

- Adams R.A. Sobolev Spaces; Academic Press, New York, USA, 1975.

- Luo Z.D. The founfations and applications of mixed finite element methods; Chinese Science Press, Beijing, China, 2006. (in Chinese).

- Wang, J.F.; Li, H.; He, S.; Gao, W.; Liu, Y. A new linearized Crank-Nicolson mixed element scheme for the extended Fisher-Kolmogorov equation. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 756281. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).