2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Experimental Procedures

IR spectra were recorded using a JASCO FT/IR-4100 spectrometer (JASCO Corporation) equipped with a PIKE MIRacle

TM single reflection ATR accessory.

1H and

13C NMR spectra were obtained at 500 MHz, using a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz spectrometer (500 MHz and 125 MHz for

1H and

13C NMR respectively) equipped with a low volume 1.7 mm inverse detection microcryoprobe (Bruker Biospin, Fällanden, Switzerland). HRESIMS and LC-UV-MS data were measured using a Bruker maXis QTOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany) coupled to an Agilent 1200 HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) and on an Agilent 1100 single quadrupole LC-MS system (Santa Clara, CA, USA), as previously described [

10]. Preparative HPLC was performed on a Gilson 322 System (Gilson Technologies, USA) using a Xbridge™ C18 (19 × 250mm, 5 μm) column at a flow rate of 20 ml/min. Semipreparative HPLC was performed on the same system using a Xbridge™ C18 (10 × 150mm, 5 μm) column at a flowrate of 2 ml/min. Evaporation of solvents was performed on a vacuum rotatory evaporator (Rotavapor R-3000r, Buchi, Postfach, Switzerland). The acetone employed for extraction, as well as the solvents used for isolation were of analytical and HPLC grade, respectively.

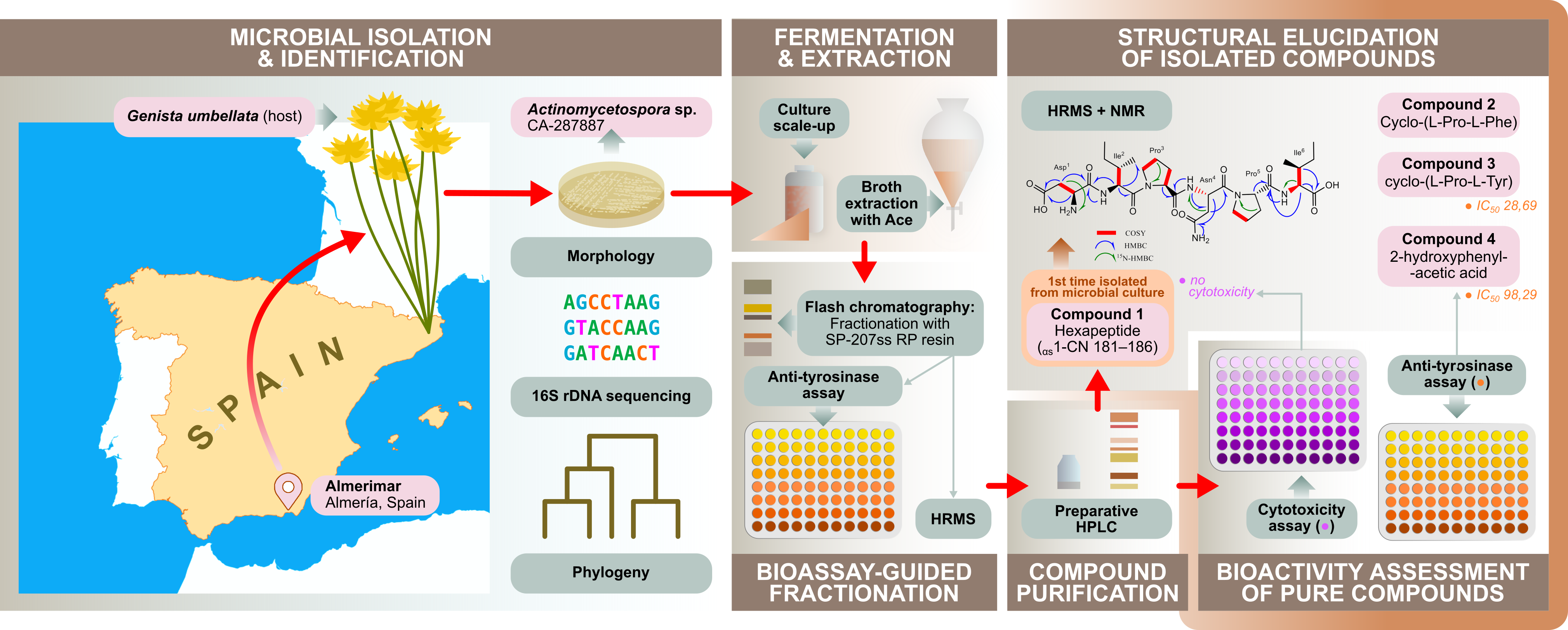

2.2. Isolation and Identification of the Strain CA-287887

2.2.1. Microbial Source

The producing strain CA-287887 is an endophyte isolated from the aerial part of a specimen of the plant

Genista umbellata, collected in Almerimar (Almería, Spain). The original colony was isolated from YECD agar medium (yeast extract-casein hydrolysate agar) [

11], containing nalidixic acid (20 µg/ml) and purified on Yeast Extract Malt Extract Glucose medium (ISP2) before its preservation as frozen agar plugs in 10% glycerol in MEDINA’s culture collection.

2.2.2. DNA Extraction and 16S rDNA Sequencing

Total genomic DNA was recovered and purified as previously described [

12] from the strain grown in ATCC-2 liquid medium (0.5% yeast extract (Difco, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), 0.3% beef extract (Difco), 0.5% peptone (Difco), 0.1% dextrose (Difco), 0.2% starch from potato (Panreac, Barcelona, Spain), 0.1% CaCO

3 (E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and 0.5% NZ amine E (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA). DNA preparations were used as template DNA for Taq Polymerase. PCR primers fD1 and 1100r were used for amplifying the 16S ribosomal RNA gene of the strain [

12]. Reactions were performed in a final volume of 50 µl containing 0.4 µM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each of the four deoxyribonucleotide triphosphates (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), 5 µl of extracted DNA, 1U Taq polymerase (Appligene, Watford, UK) with its recommended reaction buffer. PCR amplifications were performed in a Peltier Thermal Cycler PTC-200, according to the following profile: 5 min at 95°C and 40 cycles of 30s at 94°C, 30s at 52°C for and 1min at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C. The amplification products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 2% (w/v) pre-cast agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (E-gel 2%, 48 wells, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR products were sent to Secugen (

http://www.secugen.es/) for sequencing and were purified and used as a template in sequencing reactions using the primers fD1 and 1100r [

12]. Amplified DNA fragments were sequenced using the ABI PRISMDYE Terminator Cycle sequencing kit and fragments were resolved using the ABI3130 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Partial sequences were assembled and edited using the Assembler contig editor component of Bionumerics (ver 6.6) analysis software (Applied Maths NV, Sint-Martens-Latem, Belgium).

2.2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

The nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequence (1361 nucleotides) of strain CA-287887 was compared with those deposited in public databases and the EzBiocloud server [

13,

14]. The strain exhibited the highest similarity (99.56%) with

Actinomycetospora atypica NEAU-st4

T (KC412867), using EzBiocloud and GenBank sequence similarity searches and homology analysis.

Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version X [

15]. Multiple alignment was carried out using CLUSTALX [

16], integrated in the software. The phylogenetic analysis, based on the Neighbor-Joining method [

17] using matrix pairwise comparisons of sequences corrected with Jukes and Cantor algorithm [

18], shows that the strain is closely related to the type strain

Actinomycetospora atypica NEAU-st4

T and this relatedness is supported in the analysis by the bootstrap value (76) (

Figure S17).

The morphological, 16S rRNA gene sequence and phylogenetic data were indicative that strain CA-287887 was representative of members of the genus Actinomycetospora and the strain was referred to as Actinomycetospora sp. CA-287887.

2.3. Scale-Up Fermentation, Extraction and Isolation of Compounds 1-4

To scale-up the microfermentation to 2 L, 0.5 ml of the frozen inoculum stocks were added into a sterile colony tube (150 × 24 mm with a cover slip inside) filled with 10 ml of ATCC-2 seed medium (starch 20 g, dextrose 10 g, NZ Amine type E 5 g, Difco Beef extract 3 g, Bacto Peptone 5 g, Yeast extract 5 g, CaCO

3 1 g, distilled H

2O 1 L) and incubated in an orbital Kühner shaker for 5 days, at 28 °C, 70% humidity, 225 rpm. After the end of the incubation, 2.5 ml were transferred into two 250 ml baffled-flasks filled with 50 ml of seed medium and were incubated following the same conditions. 7.5 ml of the second seed medium was transferred to twenty 500 ml flasks containing 150 ml of the fermentation medium M016 [

19] and incubated for 7 days, under the same conditions.

The scale up fermentation broth (2 L) was extracted with acetone (2 L) under continuous shaking at 220 rpm for 1 h and centrifugation was followed. The remaining mixture (ca. 4 L) was concentrated to ca. 2 L under a nitrogen flow. The solution was loaded, with continuous 1:1 water dilution, keeping the flow-through (aqueous fraction, AQ) on a column packed with SP-207ss reversed-phase resin (brominated styrenic polymer, 65 g) previously equilibrated with water. The loaded column was further washed with water (2 L) and eluted at 10 ml min−1 on an automatic flash-chromatography system (CombiFlash Rf, Teledyne Isco) using a linear gradient from 5% to 100% acetone in water (in 30 min) with a final 100% acetone step (for 20 min) collecting 32 fractions of 20 ml. Fractions were concentrated to dryness on a centrifugal evaporator, tested for their tyrosinase inhibitory activity and analyzed by HRMS. Fractions 12, 13, 14 and AQ exhibited tyrosinase inhibitory effect and thus they were forwarded to a detailed chemical investigation.

Purification of fraction 12, containing mainly compound 1, was performed by preparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm) using a linear gradient of H2O−CH3CN from 5% to 35% CH3CN over 36 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min to obtain 86 fractions, that were collected every 0.5 min. Fraction 44 (13.2 mg, eluted at 22.2 min), that contained compound 1, was further purified by semipreparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm) using a linear gradient of H2O−CH3CN from 5% to 60% CH3CN over 20 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min, to yield compound 1 in high purity (1.7 mg) with a retention time of 10.4 min.

Compounds 2, 3 and 4 were obtained from fractions 13, 14 and AQ respectively. Compound 2 (2.6 mg) was obtained by using semipreparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm), using isocratic elution with H2O−CH3CN: 25-75% for 20 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 15 min (retention time of 2: 2.6 min).

Compound 3 (5.6 mg) was obtained by using first a preparative HPLC (UV detection at 210 nm), using a linear gradient from H2O−CH3CN: 95-5% to H2O−CH3CN: 30-70% over 36 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min (elution time of fraction containing 3: 10.1 min). Further purification of the fraction containing 3 was performed by semipreparative HPLC using a linear gradient system from H2O−CH3CN: 95-5% to H2O−CH3CN: 78-22% over 18 min, followed by a gradient to 100% CH3CN in 2 min (retention time of 3: 9.9 min).

Compound 4 (1.2 mg) was eluted at 4.7 min from the AQ fraction, using an isocratic method with H2O−CH3CN: 98-2% for 10 min, followed by a gradient to 100 % CH3CN in 6 min (retention time of 4: 4.7 min).

Compound (1)

Brownish solid; UV (MeOH) λ

max only end absorption detected; IR v

max 3293, 3286, 2965, 1722, 1644, 1632, 1537, 1448, 1314, 1254, 1220, 1024, 953 cm

-1;

1H (500 MHz) and

13C (125 MHz) NMR spectral data in DMSO-

d6, see

Table S1; HRESIMS

m/z: 668.3585 [M + H]

+ (calcd for C

30H

50N

7O

10, 668.3619).

2.4. Marfey’s Analysis

Compound

1 (0.5 mg, 0.5 mg/ml) was treated with 6 N HCl in a sealed vial at 110 °C for 16 h. After concentration of the hydrolyzed sample to dryness, it was reconstituted in H

2O (100 μl) and 50 μl of the sample were treated with 150 μl of L-FDVA (1% in acetone) and 20 μl of 1 M NaHCO

3 in a sealed vial at 40 °C for 1 h. The neutralization of the reaction mixture was performed with 30 μl of 1 N HCl [

20]. For the LC-MS analysis a 10 μl aliquot was diluted with 40 μl of CH

3CN. For each standard amino acid the same process was followed starting with a stock solution of 50 mM. The resulting solutions were analyzed by LC-MS using a Zorbax SB-C8 column (21 x 300 mm, 3.5 μm) and the solvents used were A (10% CH

3CN, 90% H

2O, 1.3 mM TFA, 1.3 mM ammonium formiate) and B (90% CH

3CN, 10% H

2O, 1.3 mM TFA, 1.3 mM ammonium formiate)/90%). For the hydrolysate of

1 and amino acids Ile and

allo-Ile, an isocratic system of 10% B for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient to 60% B in 33 min at flow of 1 ml/min was used. For the hydrolysate of

1 and amino acids Pro and Asp, an isocratic system of 10% B for 2 min, followed by a linear gradient to 20% B in 33 min at flow of 1 ml/min was used. The hydrolysate of

1 contained L-Ile (12.76 min), L-Pro (13.27 min) and L-Asp (6.75 min). The retention time of the L-FDVA derivatives of the authentic amino acids were as follows: L-Ile (12.77 min), D-Ile (17.83 min), L-Allo-Ile (12.55 min), D-Allo-Ile (17.66 min), L-Pro (13.21 min), D-Pro (18.94 min), L-Asp (6.52 min) and D-Asp (9.08 min).

2.5. Biological Evaluation

2.5.1. Tyrosinase Inhibitory Assay

Enzymatic Assay

The ability of the tested extracts and compounds to inhibit the catalytic action of tyrosinase in the oxidation of L-DOPA to dopachrome was performed by using mushroom tyrosinase, a lyophilized powder, ≥ 1000 units/mg solid (EC Number: 1.14.18.1) [

21].

Cell-Based Assays

Cell lines and cell culture conditions

Mouse skin melanoma cells (B16-F10) were obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATTC). B16-F10 cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% (v/v) FBS and 2 mM glutamine. Cells were maintained in a humidified environment of 5% CO2 and 37°C. They were subcultured using a trypsin/EDTA solution (ThermoFisher Scientific).

Tyrosinase activity

Mouse melanocytes B16F10 were planted in 60-mm dishes. After 24h of treatment with 1 μg/ml or 10 μg/ml for each extract, cells were lysed with 0.2% Nonidet P-40 buffer. L-DOPA (Sigma Chemical) was used as a substrate for the tyrosinase activity assay. A total of 20 μg of proteins from each sample (diluted in 100 μl of phosphate buffer) were placed in 96 well micro plate. L-DOPA (final concentration 5 mM) was added to each sample. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 60 min. The absorbance was measured at 475 nm. Each sample was prepared in triplicate. The percentage of relative tyrosinase activity was calculated as follows: % Activity = [(A1-Bl)/ (A0-Bl)] x100. Where A0 = Control absorbance, Bl = Blank absorbance (L-DOPA only), A1 = Sample absorbance.

2.5.2. Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxicity was tested against HepG2, A2058, A549, MCF-7 and MIA PaCa-2 cell lines by the ΜΤΤ method and on CCD25sk cell line by the HOECHST assay, following an already described process [

12].

3. Results and Discussion

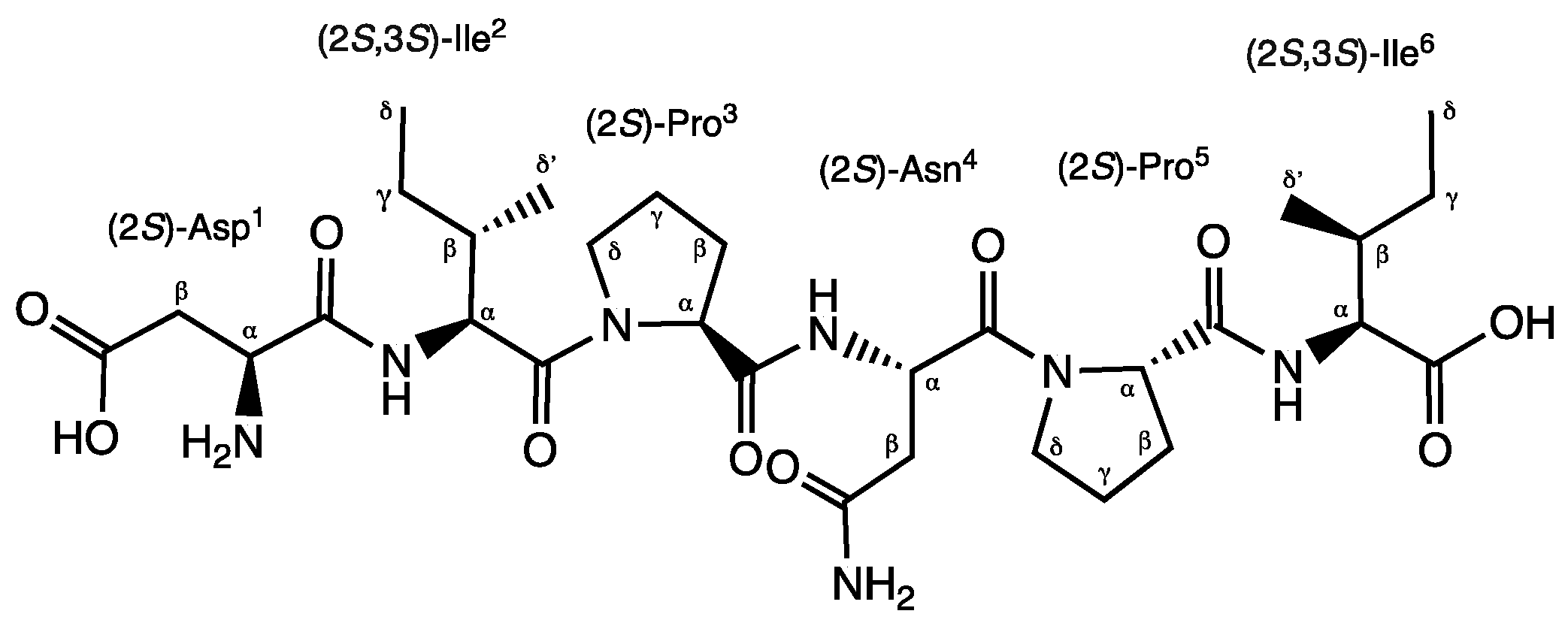

Compound 1 was obtained as a brownish solid. On the basis of 1D and 2D- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) experiments, along with High Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectroscopy (HRESIMS) data, its molecular formula, implying ten degrees of unsaturation, was deduced to be C30H49N7O10 (m/z 666.3454 [M-H]-, m/z 668.3585 [M+H]+). The infrared spectroscopy (IR) spectrum of compound 1 showed characteristic absorption bands for secondary amines (3286 cm−1) and amide carbonyls (1632 cm−1), while the absence of any UltraViolet (UV) absorption above 201 nm excluded the presence of conjugated π (pi) bond systems. Analysis of the 13C NMR spectrum revealed 30 signals. On the basis of a Distortionless Enhancement by Polarization Transfer (DEPT) and of a Heteronuclear Single-Quantum Correlation Spectroscopy (HSQC)-DEPT experiment, aforementioned signals were assigned to eight methine, ten methylene, four methyl, and eight quaternary carbons, while the analysis of the 15N-HSQC and 15N-Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation (15N-HMBC) spectra revealed additional nitrogen signals relative to one primary, three secondary and two tertiary amide groups. In the ¹H-¹H Correlation Spectroscopy (COSY) experiment, NH signals of each secondary amide showed cross-peaks with proton resonances at δH 4.07, 4.34 and 4.74 in the 1H NMR spectrum, which is characteristic of the α-methine protons of amino acidic residues. The analysis of the different spin systems by 2D- Total Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-TOCSY) resolved and assigned the α-methine protons at δH 4.07 and 4.34 to two isoleucine residues (Ile2 and Ile6), while the HMBC correlation of the α-methine proton at δH 4.74 with the carbonyl of a primary amide group at δC 171.8 suggested the presence of Asparagine (Asn4). In addition, the HMBC correlations of Ile2 and Ile6 Hα protons with their respective Cγ, Cδ’ protons, as well the hetero correlations between the primary amide protons at δH 7.40 and 6.88 and the carbonyl carbon at δC 171.8 of the side chain of Asn4, further confirmed the above hypothesis.

Three additional α-methine protons at δH 3.75, 4.31, 4.38 were identified in the 1HNMR spectrum. However, unlike Hα protons of Ile2, Ile6 and of Asn4, they didn’t show any COSY correlation with amino carbonyl protons. Regarding downshifted α-protons at δH 4.31 and 4.38, this was a clear evidence of an adjacent tertiary amide group instead of a primary amine. Analysis of the HMBC spectrum evidenced the correlation of the α-proton at δH 4.31 and 4.38 with methylene carbons at δC 29.1, 24.2, 47.2 and 28.9, 24.4, 46.6, respectively. Aforementioned chemical shifts in combination to the presence of tertiary amide groups suggested the presence of two proline residues in the molecule (Pro3 and Pro5). Further analysis of COSY and TOCSY spectra confirmed the above findings.

Finally, the upfield shift of the α-methine proton at δH 3.75 in combination to its COSY correlation with methylene β-protons at δH 2.45 and 2.27, which in turn give 15N HMBC correlations to an aliphatic ammine at δC 32.9, suggested the presence of a N-terminal aminoacidic residue. Further analysis of the HMBC spectrum showed the 2J and 3J long range correlation between the α- and β-protons and the quaternary carbon at δC 172.6, suggesting an acetyl side chain relative to aspartic acid (Asp1).

The exact sequence was established on the basis of HMBC and Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments (

Figure S1 &

Figure S2). The HMBC correlation between the H

α of Ile

2 and the carbonyl amide at

δC 170.9 of Asp

1 confirmed the first two amino acids of the hexapeptide molecule, while the NOESY correlations H

α, H

δ΄ (Ile

2)/ H

δ (Pro

3), H

α (Pro

3)/ NH(Asn

4), H

α (Pro

3)/ NH(Asn

4) in combination to the HMBC correlation H

α(Pro

3), NH(Asn

4)/ CO(Pro

3) unambiguously assigned the position of the residues Pro

3 and Asn

4. Finally, the positions of Pro

5 and of Ile

6 were defined on the basis of the NOESY correlations between H

α (Asn

4)/ H

δ (Pro

5), H

α (Pro

5)/ NH(Ile

6) and of the HMBC correlations between H

α, NH (Ile

6)/ CO(Pro

5). Consequently, the presence of the linear peptide N-Asp-Ile-Pro-Asn-Pro-Ile was assumed. Further ESI-MS/MS analysis confirmed our hypothesis. Indeed, it showed characteristic ions at

m/z 551.3, 438.2, 324.1, 341.1, 227.1, and 130.9 corresponding to the fragmentation of the five peptide bonds composing the hexapeptide. (

Figure S3).

The absolute configuration of the amino acid residues was determined by performing Marfey’s analysis [

20]. The hydrolysis of compound

1 with hydrochloric acid (HCl) 6N and the derivatization of the hydrolysate with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-

L-valinamide (

L-FDVA) disclosed that the absolute configuration of all residues was

L. Amino acid derivatives were identified by comparison of their retention time with Nα-(2,4- dinitro-5-fluorophenyl)-L-leucinylamide (FDLA) derivatized

D- and

L-amino acid standards. Accordingly, the absolute configuration of compound

1 was elucidated as L-Asp-L-Ile-L-Pro-L-Asn-L

-Pro-L-Ile.

In addition, bioassay-guided fractionation led to the isolation of three known compounds, namely cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Phe) (

2) [

22], cyclo-(L-Pro-L-Tyr) (

3) [

23] and 2-hydroxyphenylacetic acid (

4) [

24]. Their structures were established on the basis of NMR and HRMS data and by comparison of their spectroscopic and physical data with the literature.

All isolated compounds were tested for their ability to inhibit tyrosinase. Compound

3 (IC

50 =28.69 μΜ) exhibited the highest inhibitory activity with an IC

50 value comparable to that of the positive control kojic acid (IC

50 =14.07 μΜ). Its potential use as a tyrosinase inhibitor was further supported by its lack of any cytotoxic effect [

25,

26,

27]. A moderate activity was also found for compound

4 (IC

50 =98.29 μΜ) while no inhibitory effect was confirmed for compounds

1 and

2 (IC

50 >300 μM). The inhibitory capacity of compounds

3 and

4 was statistically significant (P<0.01)

vs. control samples. To our knowledge, this is the first report on investigating the anti-tyrosinase effect of compounds

3 and

4 using L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) as substrate [

28]. Compound

1 represent a class of peptides with high resistance to proteolysis and capable of immune modulation and of other therapeutic activities, including but not limited to the protection against viral infection, in growth stimulation and in normalizing serum cholesterol levels [

29,

30,

31]. During our analysis, we screened compound

1 against a panel of cancer cell lines. No cytotoxic effect against the cancer cell lines HepG2, A2058, A549 and MiaPaca-2 was detected at the highest concentration used. Consideration that compound

1 belongs to a class of peptides that are capable of surviving gastrointestinal digestion, the lack of cytotoxicity can be interpreted as a positive outcome in view of its potential therapeutic activities.

Compound (1)

Brownish solid;

UV (MeOH) λ

max only end absorption detected; IR v

max 3293, 3286, 2965, 1722, 1644, 1632, 1537, 1448, 1314, 1254, 1220, 1024, 953 cm

-1;

1H (500 MHz) and

13C (125 MHz) NMR spectral data in DMSO-

d6, see

Table S1; NMR homo- and hetero-correlations in DMSO-

d6, see

Table S2; HRESIMS

m/z: 668.3605 [M + H]

+ (calcd for C

30H

50N

7O

10, 668.3619).