Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Structural and Microstructural Analysis

3.2. Magnetocaloric Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jafari, M., Botterud, A., et al., Decarbonizing power systems: A critical review of the role of energy storage, Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158 2022 112077 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Golombek, R., Lind, A., et al., The role of transmission and energy storage in European decarbonization towards 2050, Energy 239 2022 122159 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Oskouei, M.Z., Şeker, A.A., et al., A Critical Review on the Impacts of Energy Storage Systems and Demand-Side Management Strategies in the Economic Operation of Renewable-Based Distribution Network, Sustainability 14 2022 2110 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, H., Dincer, I., et al., A review on hydrogen production and utilization: Challenges and opportunities, Int. Jour. Hydrogen Energy 47 2022 62 26238-26264. [CrossRef]

- Ratnakar, R.R., Gupta, N., et al., Hydrogen supply chain and challenges in large-scale LH2 storage and transportation, Int. Jour. Hydrogen Energy 46 2021 47 24149-24168. [CrossRef]

- Al Ghafri, S.Z.S., Munro, S., et al., Hydrogen liquefaction: a review of the fundamental physics, engineering practice and future opportunities, Energy & Environ. Sci. 15 2022 7 2690-2731. [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G., Di Dio, V., et al., Perspective on hydrogen energy carrier and its automotive applications, Int. Jour. Hydrogen Energy 39 2014 16 8482-8494. [CrossRef]

- Kitanovski, A., Energy Applications of Magnetocaloric Materials, Adv. Energy Mater. 10 2020 1903741 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Taake, C., et al., Magnetocaloric effect in the (Mn,Fe)2(P,Si) system: From bulk to nano, Acta Materialia 224 2022 117532 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Belo, J.H., Pereira, A.M., et al., Phase control studies in Gd5Si2Ge2 giant magnetocaloric compound, Jour. Alloys and Compounds 529 2012 89-95. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H., Kuang, C., et al., Magnetocaloric effect of Gd5Si2Ge2 alloys in low magnetic field, Bull. Mater. Sci. 34 2011 4 825-828. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.F., Mu, L.J., et al., Hydriding and dehydriding kinetics in magnetocaloric La(Fe,Si)13 compounds, Jour. Appl. Phys. 115 2014 143903 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Adapa, S.R., Feng, T.S., et al., Optimisation of a packed particle magnetocaloric refrigerator: A combined experimental and theoretical study, Int. Jour. Refrigeration 159 2024 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Asamoto, K., et al., Magnetocaloric effect of (ErxR1_x)Co2 (R = Ho, Dy) for magnetic refrigeration between 20 and 80 K, Cryogenics 51 2011 494-498.

- Terada, N., Mamiya, H., High-efficiency magnetic refrigeration using holmium, Nat. Comm. 12 2021 1212 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Bykov, E., Liu, W., et al., Magnetocaloric effect in the Laves-phase Ho1−xDyxAl2 family in high magnetic fields, Phys. Rev. Materials 5 2021 095405 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Park, I., Jeong, S., Development of the active magnetic regenerative refrigerator operating between 77 K and 20 K with the conduction cooled high temperature superconducting magnet, Cryogenics 88 2017 106-115. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., Sepehri-Amin, H., et al., Magnetic refrigeration material operating at a full temperature range required for hydrogen liquefaction, Nat. Comm. 13 2022 1817 1-8. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, P.B., Terashima, K., et al., Enhancement of giant refrigerant capacity in Ho1-xGdxB2 alloys (0.1 ≤ x ≤ 0.4), Jour. Alloys and Compounds 865 2021 158881 1-6. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, P.B., Terashima, K.T., et al., Machine-learning-guided discovery of the gigantic magnetocaloric effect in HoB2 near the hydrogen liquefaction temperature, NPG Asia Materials 12 2020 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Bruker, K., Technical Reference Manual Bruker AXS, Germany 2014.

- Franco, V., Blázquez, J.S., et al., Magnetocaloric effect: From materials research to refrigeration devices, Prog. Mater. Sci. 93 2018 112.

- Kravchenko, S.E., Kovalev, D.Y., et al., Synthesis and Thermal Oxidation Stability of Nanocrystalline Niobium Diboride, Inorg. Mater. 57 2021 10 1005-1014. [CrossRef]

- Moze, O., Kockelmann, W., et al., Neutron diffraction study of CeNi5Sn, Jour. Alloys and Compounds 279 1998 2 110-112. [CrossRef]

- Whittle, K.R., Hyatt, N.C., et al., Combined neutron and X-ray diffraction determination of disorder in doped zirconolite-2M, Amer. Mineral. 97 2012 2-3 291-298. [CrossRef]

- Vegard, L., Die Konstitution der Mischkristalle und die Raumfüllung der Atome, Zeit. für Physik 5 1921 1 17-26. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Goldbach, A., et al., Structural and Permeation Kinetic Correlations in PdCuAg Membranes, ACS Appl. Mater. & Interfaces 6 2014 24 22408-22416. [CrossRef]

- Terada, N., Terashima, K., et al., Relationship between magnetic ordering and gigantic magnetocaloric effect in HoB2 studied by neutron diffraction experiment, Phys. Rev. B 102 2020 094435 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.K., On a generalised approach to 1st and 2nd order magnetic transitions, Phys. Lett. 12 1964 1 16-17. [CrossRef]

- de Castro, P.B., Terashima, K., et al., Effect of Dy substitution in the giant magnetocaloric properties of HoB(2), Sci Technol Adv Mater 21 2021 1 849-855. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Bykov, E., et al., A study on rare-earth Laves phases for magnetocaloric liquefaction of hydrogen, Appl. Mater. Today 29 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.E.-M., Hernando, B., Self-assembled impurity and its effect on magnetic and magnetocaloric properties of manganites, Ceramics International 44 2018 14 17044.

- Mokhatab, S., Mak, J.Y., et al., Chapter 3 - Natural Gas Liquefaction, in: Mokhatab, S., et al. (Eds.), Handbook of Liquefied Natural Gas, Gulf Professional Publishing, Boston, 2014, pp. 147-183. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Nielsen, C.P., et al., Breaking the hard-to-abate bottleneck in China’s path to carbon neutrality with clean hydrogen, Nat. Energy 7 2022 10 955-965. [CrossRef]

- Park, I., Lee, C., et al., Performance of the Fast-Ramping High Temperature Superconducting Magnet System for an Active Magnetic Regenerator, IEEE Trans. Appl. Superconductivity 27 2017 4601105 1-5.

- Zhou, X., Shang, Y., et al., Large rotating magnetocaloric effect of textured polycrystalline HoB2 alloy contributed by anisotropic ferromagnetic susceptibility, Appl. Phys. Lett. 120 2022 132401 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, S., Yamamoto, T.D., et al., Al substitution effect on magnetic properties of magnetocaloric material HoB2, Solid State Communications 342 2022 114616 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Lai, J., Bolyachkin, A., et al., Machine learning assisted development of Fe2P-type magnetocaloric compounds for cryogenic applications, Acta Materialia 232 2022 117942 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.D., Takeya, H., et al., Effect of Non-Stoichiometry on Magnetocaloric Properties of HoB2 Gas-Atomized Particles, IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 58 2022 6 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H., Schlesinger, M.E., et al., Ho (Holmium) Binary Alloy Phase Diagrams, Alloy Phase Diagrams, ASM International 2016.

- Kim, J.Y., Cho, B.K., et al., Anisotropic magnetic phase diagrams of HoB4 single crystal, Journal of Applied Physics 105 2009 07E116 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Fisk, Z., Maple, M.B., et al., Multiple phase transitions in rare earth tetraborides at low temperature, Solid State Communications 39 1981 11 1189-1192. [CrossRef]

- Boutahar, A., Moubah, R., et al., Large reversible magnetocaloric effect in antiferromagnetic Ho2O3 powders, Scientific Reports 7 2017 13904 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Shinde, K.P., Nana, W.Z., et al., Magnetocaloric effect in rare earth Ho2O3 nanoparticles at cryogenic temperature, Jour. Magnet. Magnetic Mater. 500 2020 166391 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Rajivgandhi, R., Chelvane, J.A., et al., Effect of rapid quenching on the magnetism and magnetocaloric effect of equiatomic rare earth intermetallic compounds RNi (R = Gd, Tb and Ho), Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 433 2017 169-177. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.A., Nakagawa, T., et al., Magnetocaloric effect of rare earth mono-nitrides, TbN and HoN, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 376 2004 1-2 17-22. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.D., Takeya, H., et al., Gas-atomized particles of giant magnetocaloric compound HoB2 for magnetic hydrogen liquefiers, Applied Physics A 127 2021 1-8. [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | Starting materials | Reactant ratio | Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| HoB2 | Ho:B | 1:2 | HoB2 (92.1%), Ho2O3 (4.0%), Ho (3.9%) |

| (Ho,Nb)B2 | Ho:Nb:B | 0.9:0.1:2 | HoB2 (72.1%), HoB4 (9.2%), Ho2O3 (4.6%), Ho (4.6%), HoB12 (3.8%), NbB2 (3.2%) |

| Sample | a (Å) | c (Å) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| HoB2 | 3.28296(2) | 3.814454(4) | This work |

| Ho1-xNbxB2 | 3.268009(6) | 3.784152(1) | This work |

| HoB2 | 3.2835(4) | 3.8186(14) | PDF# 04-003-0232 |

| *NbB2 | 3.1049(3) | 3.2990(2) | PDF# 04-014-5978 |

| Alloy | TC (K) |

(Jkg-1K-1) | RCP (Jkg-1) |

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

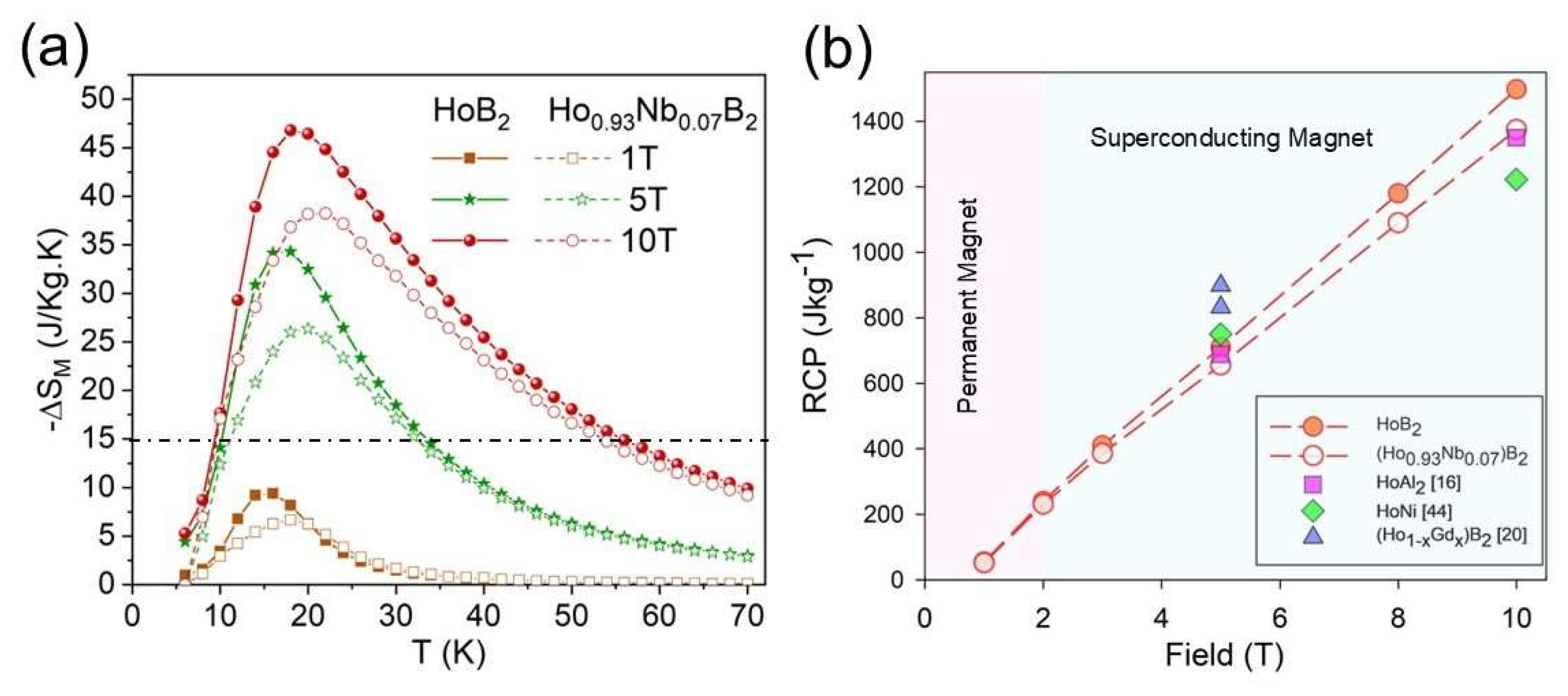

| at 5 T | at 10 T | At 5 T | At 10 T | |||

| HoB2 | 15 | 39.2 | - | 706* | - | [39] |

| HoB2 | 15.8 | 34.3 | 46.8 | 720 | 1,474 | This work# |

| Ho0.93Nb0.07B2 | 17.5 | 26.4 | 38.2 | 673 | 1,337 | This work# |

| Ho0.9Gd0.1B2 | 19 | 34.6 | - | 833 | - | [19] |

| Ho0.6Gd0.4B2 | 30 | 20.2 | - | 889 | - | [19] |

| HoAl2 | 29 | 21.5 | 30* | 688* | 1,350* | [16] |

| HoNi | 36 | 17.4 | ~26* | 750 | 1,222* | [45] |

| HoN | 18 | 28.2 | - | 846* | - | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).