Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.1. Procedure Methodology

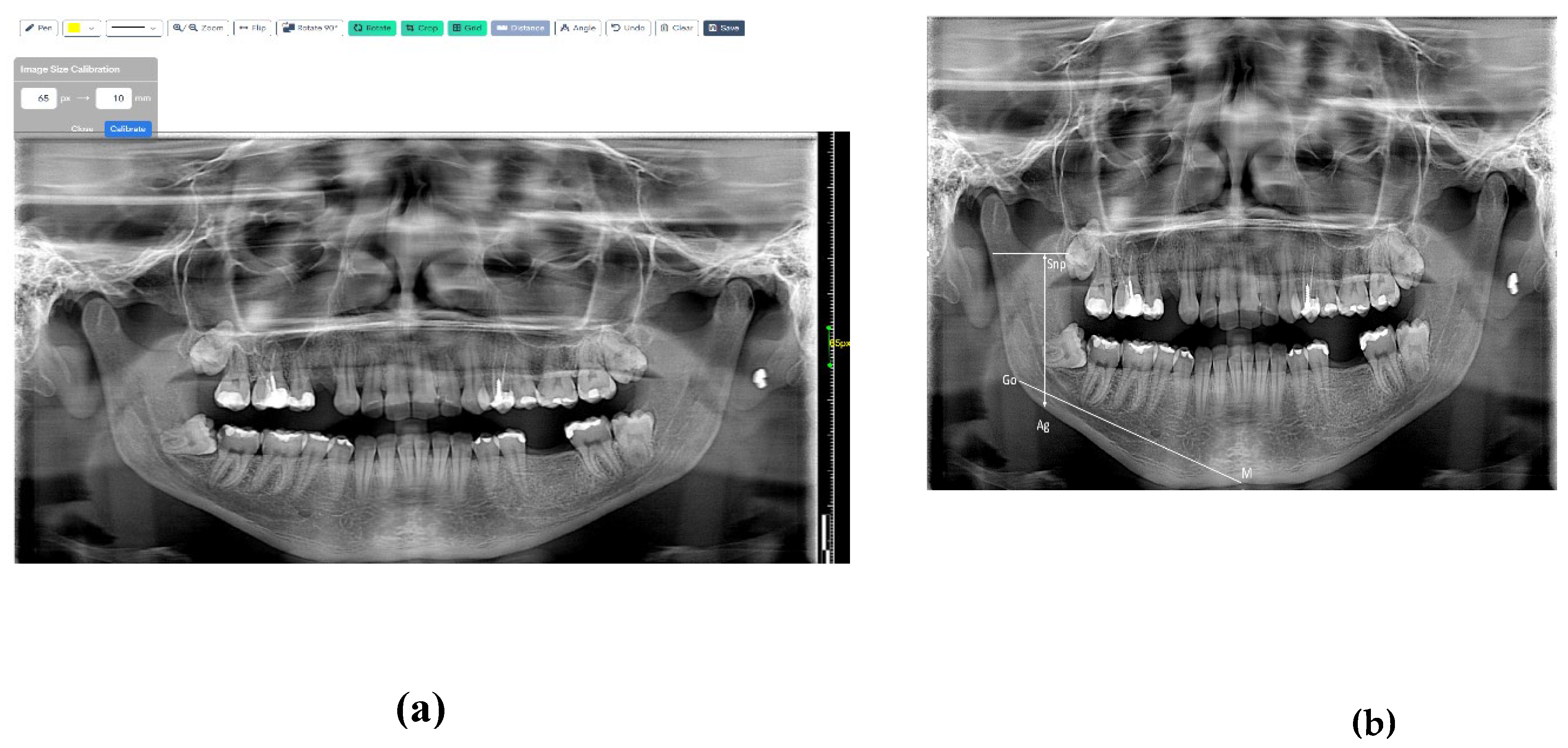

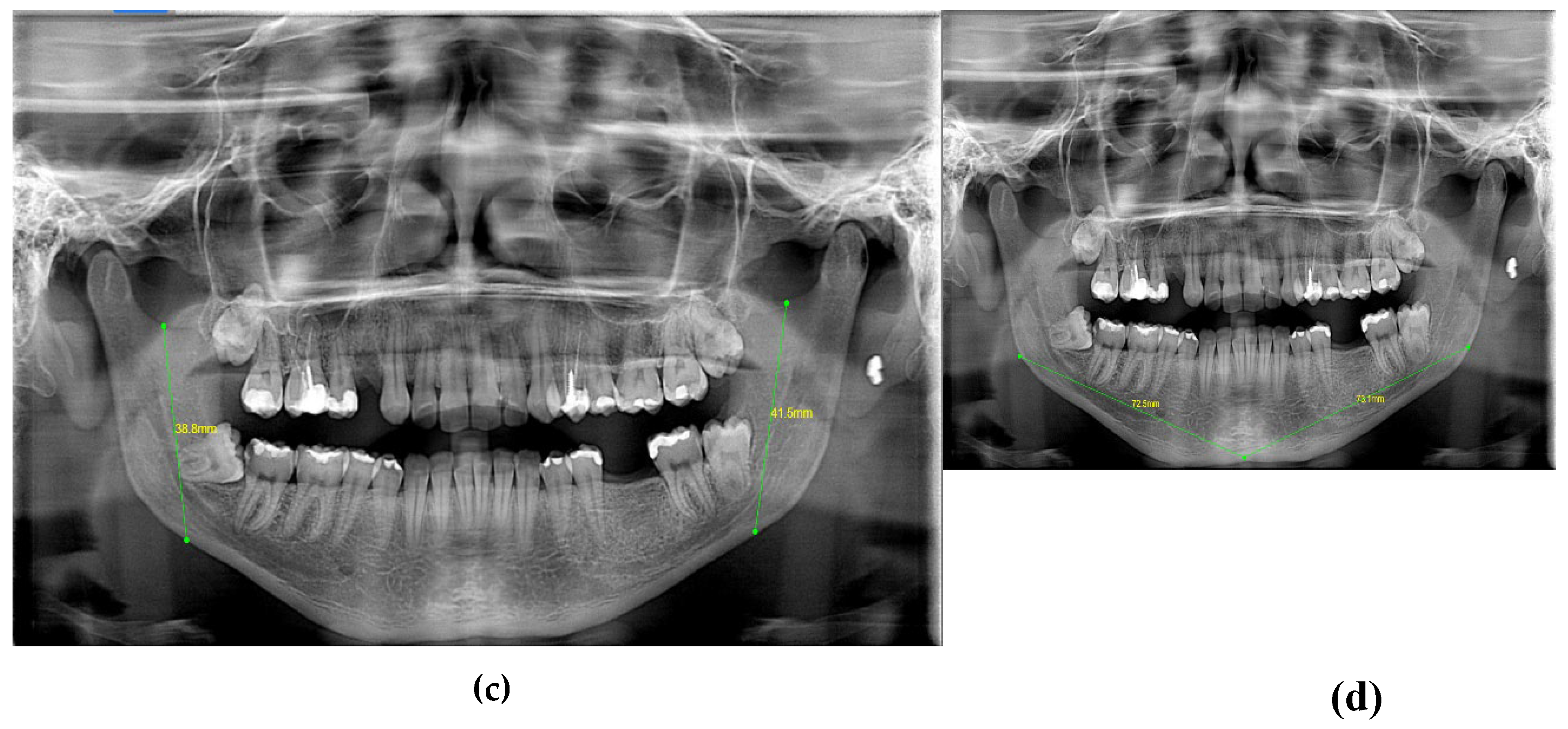

2.1.1. Protocol and Measurements for Digital Lateral Cephalometry and Orthopantomographs

2.1.2. Reliability Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tashkandi, N.E.; Alnaqa, N.H.; Al-Saif, N.M.; Allam, E. Accuracy of Gonial Angle Measurements Using Panoramic Imaging versus Lateral Cephalograms in Adults with Different Mandibular Divergence Patterns. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 1923–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, M.; Ramazanzadeh, B.A.; Mokhber, N. Comparison between the external gonial angle in panoramic radiographs and lateral cephalograms of adult patients with Class I malocclusion. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 51, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Oh, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ahn, H.W.; Kang, Y.G.; Choi, Y.S.; Nelson, G. Effectiveness of 2D Radiographs in Detecting CBCT-Based Incidental Findings in Orthodontic Patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farman, A.G. Panoramic Radiographic Assessment in Orthodontics. In Panoramic Radiology: Seminars on Maxillofacial Imaging and Interpretation; Langlais, R.P., Langland, O.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007; pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent, B.H. A New X-Ray Technique and Its Application to Orthodontia. Angle Orthod. 1931, 1(2), 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.A.; Lee, J.S.; Hwang, H.S.; Lee, K.M. Benefits of Lateral Cephalogram During Landmark Identification on Posteroanterior Cephalograms. Korean J. Orthod. 2019, 49(1), 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mangoury, N.H.; Shaheen, S.I.; Mostafa, Y.A. Landmark Identification in Computerized Posteroanterior Cephalometrics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1987, 91(1), 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, P.W.; Johnson, D.E.; Hesse, K.L.; Glover, K.E. Landmark Identification Error in Posterior Anterior Cephalometrics. Angle Orthod. 1994, 64(6), 447–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, A.E.; Miethke, R.R.; Van Der Meij, A.J.W. Random Errors in Localization of Landmarks in Postero-Anterior Cephalograms. Br. J. Orthod. 1999, 26(4), 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, S.; Iguchi, Y.; Takada, K. Asymmetry of the Face in Orthodontic Patients. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78(3), 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, M.S.; Naini, F.B.; Gill, D.S. The Aetiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Mandibular Asymmetry. Orthod. Update 2008, 1(2), 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.W.; Lo, L.J. Facial Asymmetry: Etiology, Evaluation, and Management. Chang Gung Med. J. 2011, 34(4), 341–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Jain, S. Orthopantomographic Analysis for Assessment of Mandibular Asymmetry. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2012, 46(1), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Thailavathy, V.; Srinivasan, D.; Loganathan, D.; Yamini, J. Comparison of Orthopantomogram and Lateral Cephalogram for Mandibular Measurements. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2017, 9 (Suppl. 1), S92–S95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Park, J.-B.; Chang, M.-S.; Ryu, J.-J.; Lim, W.H.; Jung, S.-K. Influence of the Depth of the Convolutional Neural Networks on an Artificial Intelligence Model for Diagnosis of Orthognathic Surgery. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Bae, K.H.; Park, Y.J.; Hong, R.K.; Nam, J.H.; Kim, M.J. Assessment of Antero-Posterior Skeletal Relationships in Adult Korean Patients in the Natural Head Position and Centric Relation. Korean J. Orthod. 2010, 40(6), 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.K.; Alfawzan, A.A. Dental Characteristics of Different Types of Cleft and Non-cleft Individuals. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.K.; Alfawzan, A.A. Evaluation of Sella Turcica Bridging and Morphology in Different Types of Cleft Patients. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Correlations between Mandibular Ramus Height and Occlusal Planes in Han Chinese Individuals with Normal Occlusion: A Cross-Sectional Study. APOS Trends Orthod. 2021, 11(3), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan, P.D.; Varma, N.K.S.; Ajith, V.V. Dilemma of Gonial Angle Measurement: Panoramic Radiograph or Lateral Cephalogram. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2017, 47(2), 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gunaid, T.H.; Bukhari, A.K.; El Khateeb, S.M.; Yamaki, M. Relationship of Mandibular Ramus Dimensions to Lower Third Molar Impaction. Eur. J. Dent. 2019, 13, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuhanek, C.; Schiller, A.; Grigore, A.; Popa, L. Ghid Ortodonție; Editura Victor Babeș: 2019.

- Jensen, E.; Palling, M. The Gonial Angle: A Survey. Am. J. Orthod. 1954, 40, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larheim, T.A.; Svanaes, D.B. Reproducibility of Rotational Panoramic Radiography: Mandibular Linear Dimensions and Angles. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 1986, 90, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongkosuwito, E.M.; Dieleman, M.M.; Kuijpers-Jagtman, A.M.; Mulder, P.G.; van Neck, J.W. Linear Mandibular Measurements: Comparison between Orthopantomograms and Lateral Cephalograms. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2009, 46, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronje, G.; Welander, U.; McDavid, W.D.; Morris, C.R. Image Distortion in Rotational Panoramic Radiography: IV. Object Morphology; Outer Contours. Acta Radiol. Diagn. 1981, 22, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, K.; Altonen, M.; Haavikko, K. Determination of the Gonial Angle from the Orthopantomogram. Angle Orthod. 1977, 47, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nohadani, N.; Ruf, S. Assessment of Vertical Facial and Dentoalveolar Changes Using Panoramic Radiography. Eur. J. Orthod. 2008, 30, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akcam, M.O.; Altiok, T.; Ozdiler, E. Panoramic radiographs: A tool for investigating skeletal pattern. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2003, 123, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, G.; Uysal, T.; Sisman, Y.; Ramoglu, S.I. Mandibular Asymmetry in Class II Subdivision Malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| S. No. | Measurement | Description |

|---|---|---|

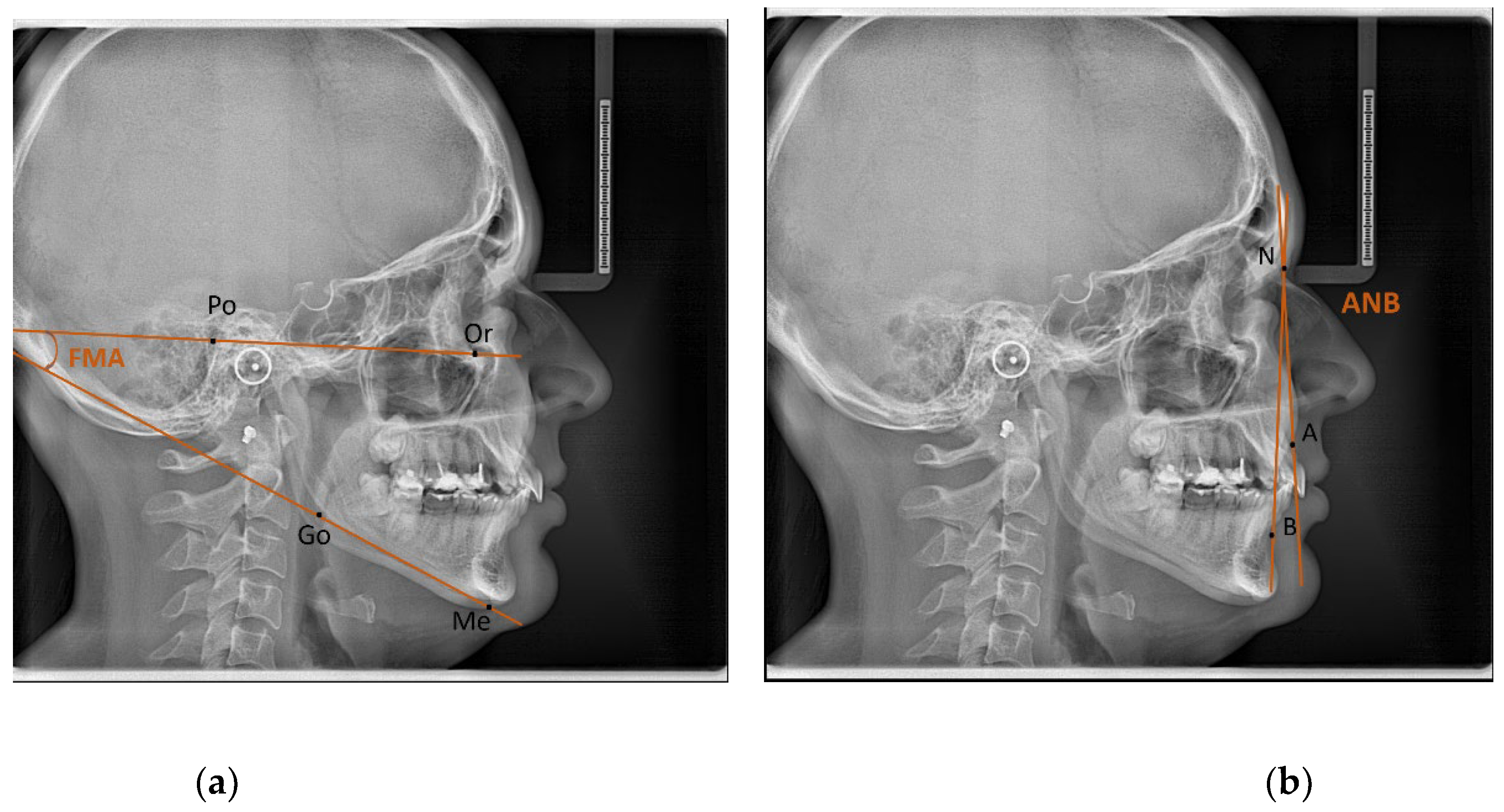

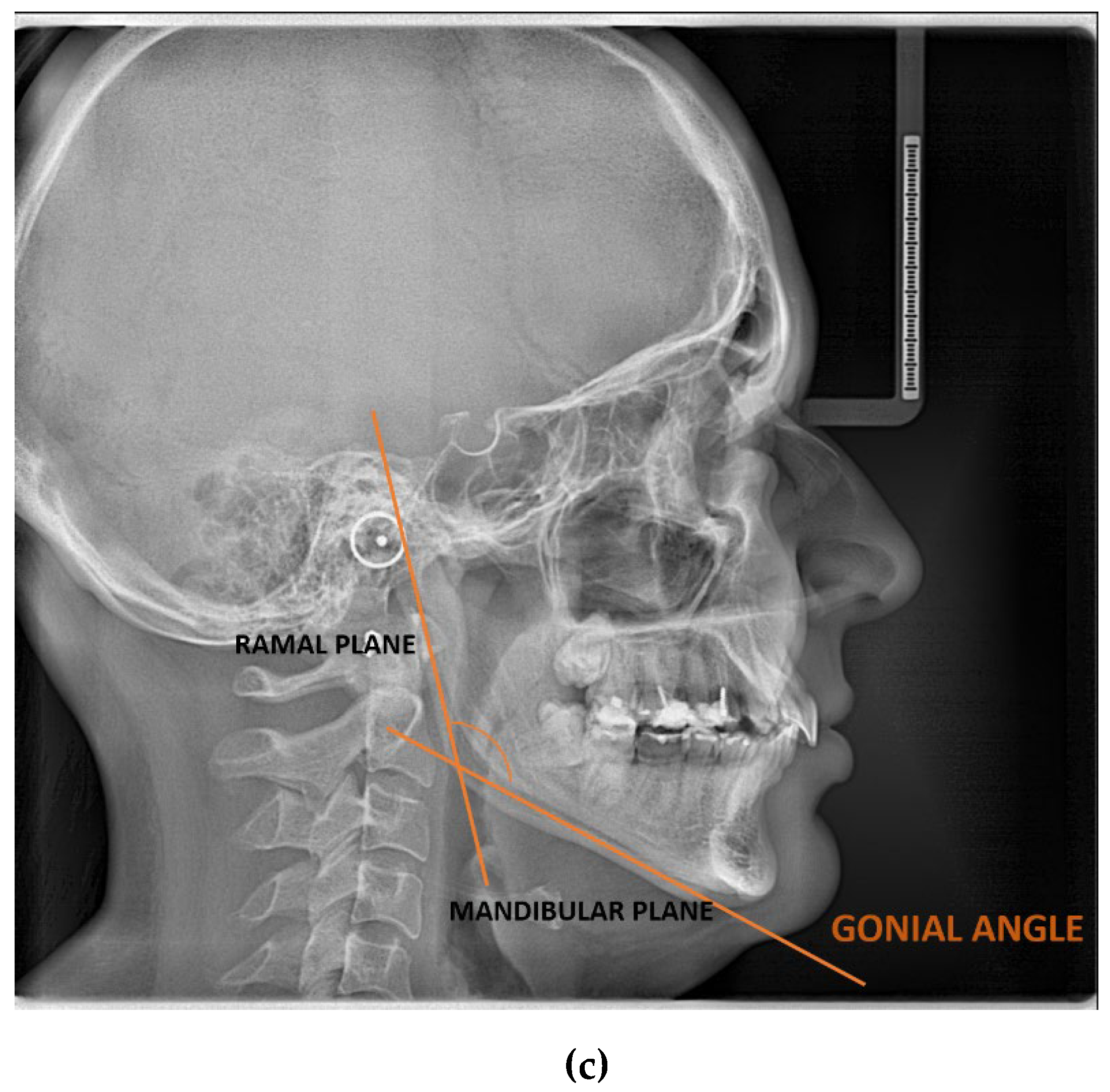

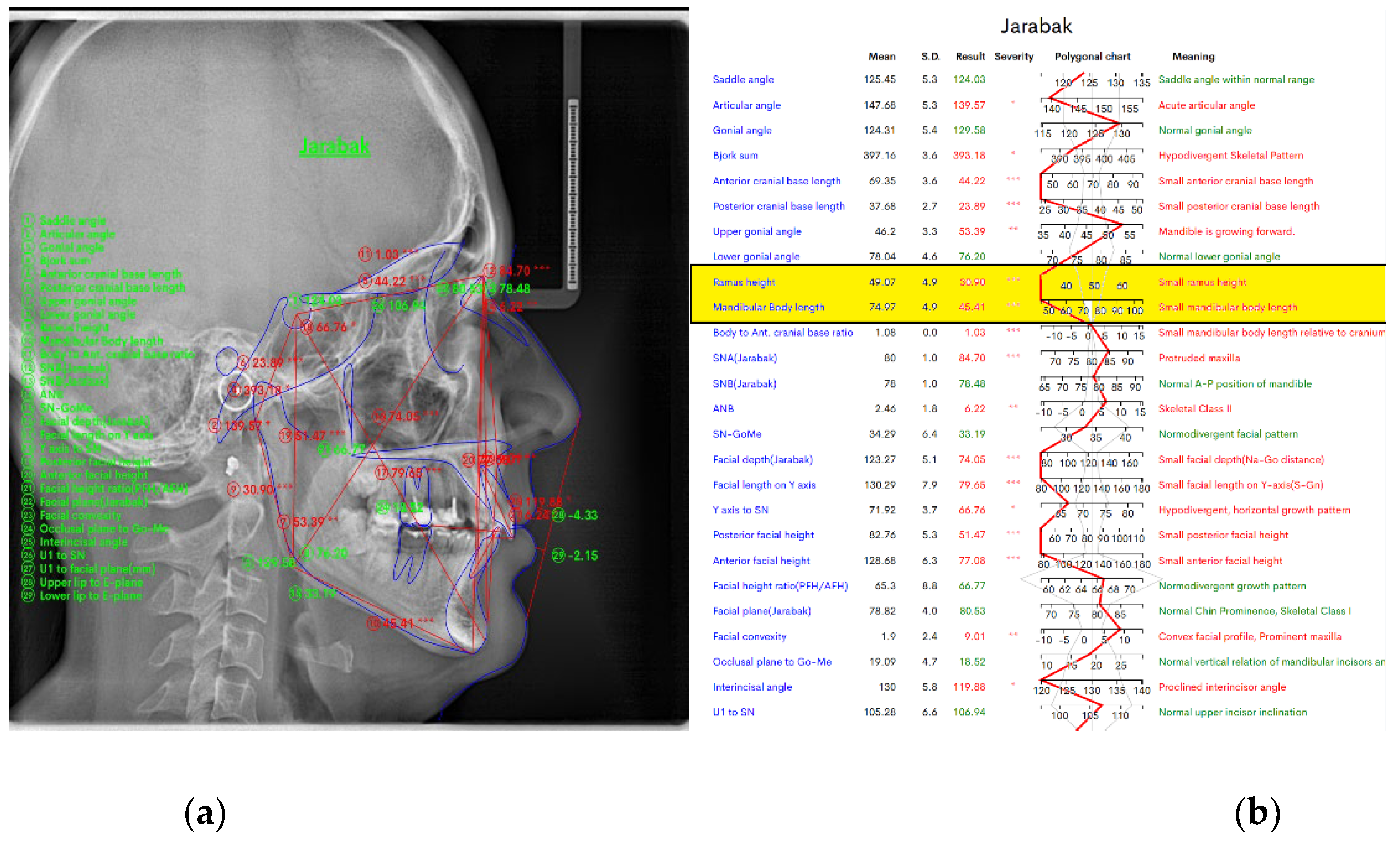

| 1 | ANB (°) | Angle between the Nasion-A point and the Nasion-B point plane [19]. |

| 2 | FMA (°) | Angle formed by the FH plane and the mandibular plane [19]. |

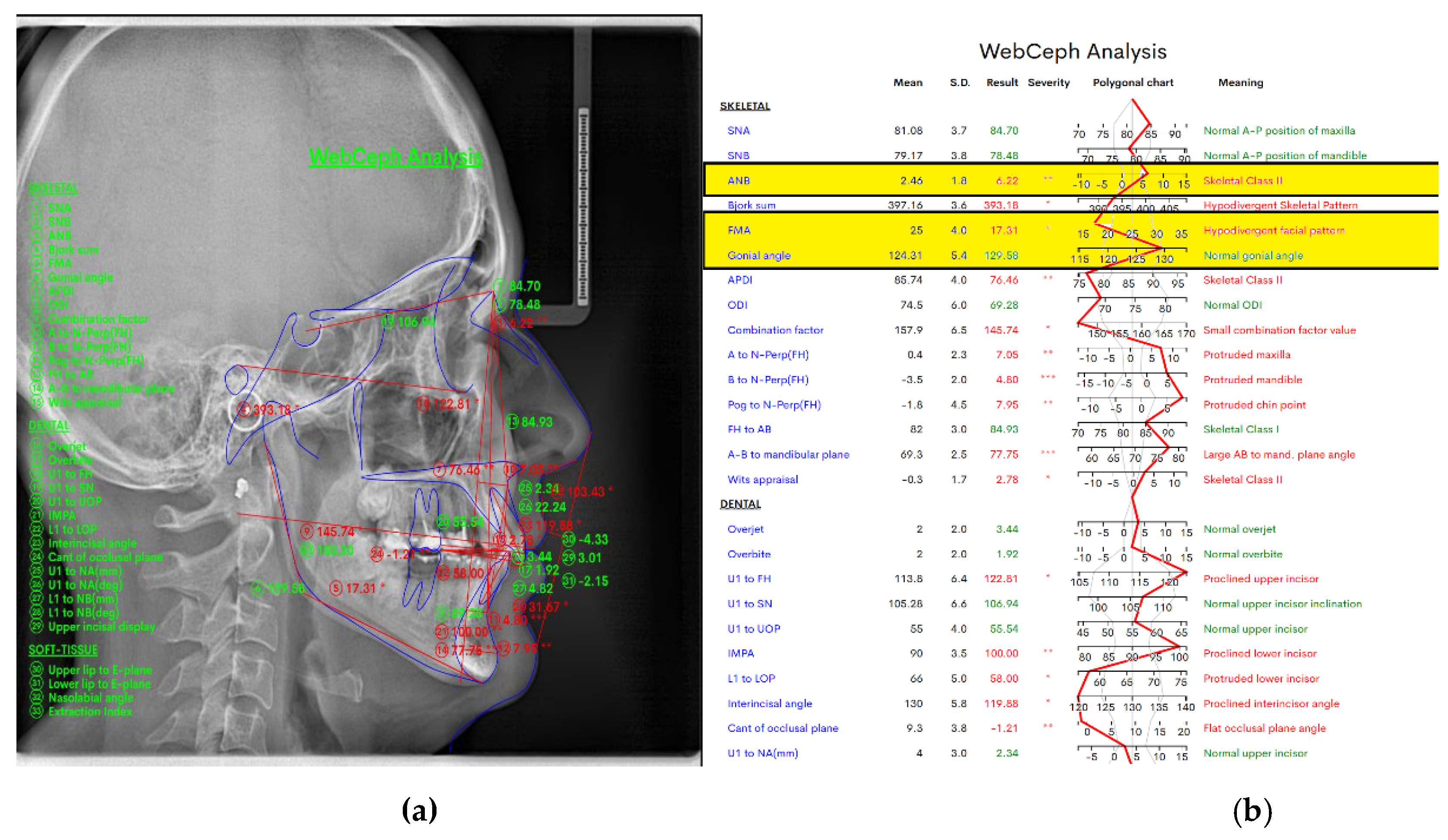

| 3 | GONIAL ANGLE (°) | At lateral cephalograms, it was determined at the junction of the mandibular and ramus planes. A line tangent to the lower border of the mandible and another line tangent to the distal border of the ascending ramus and the condyle on either side were drawn in order to measure the gonial angle in the panoramic radiographs [20]. The mandibular plane and the ramus plane’s built point of junction. |

| 4 | RAMUS HEIGHT | (mm) The distance between Ag and Snp [21]. |

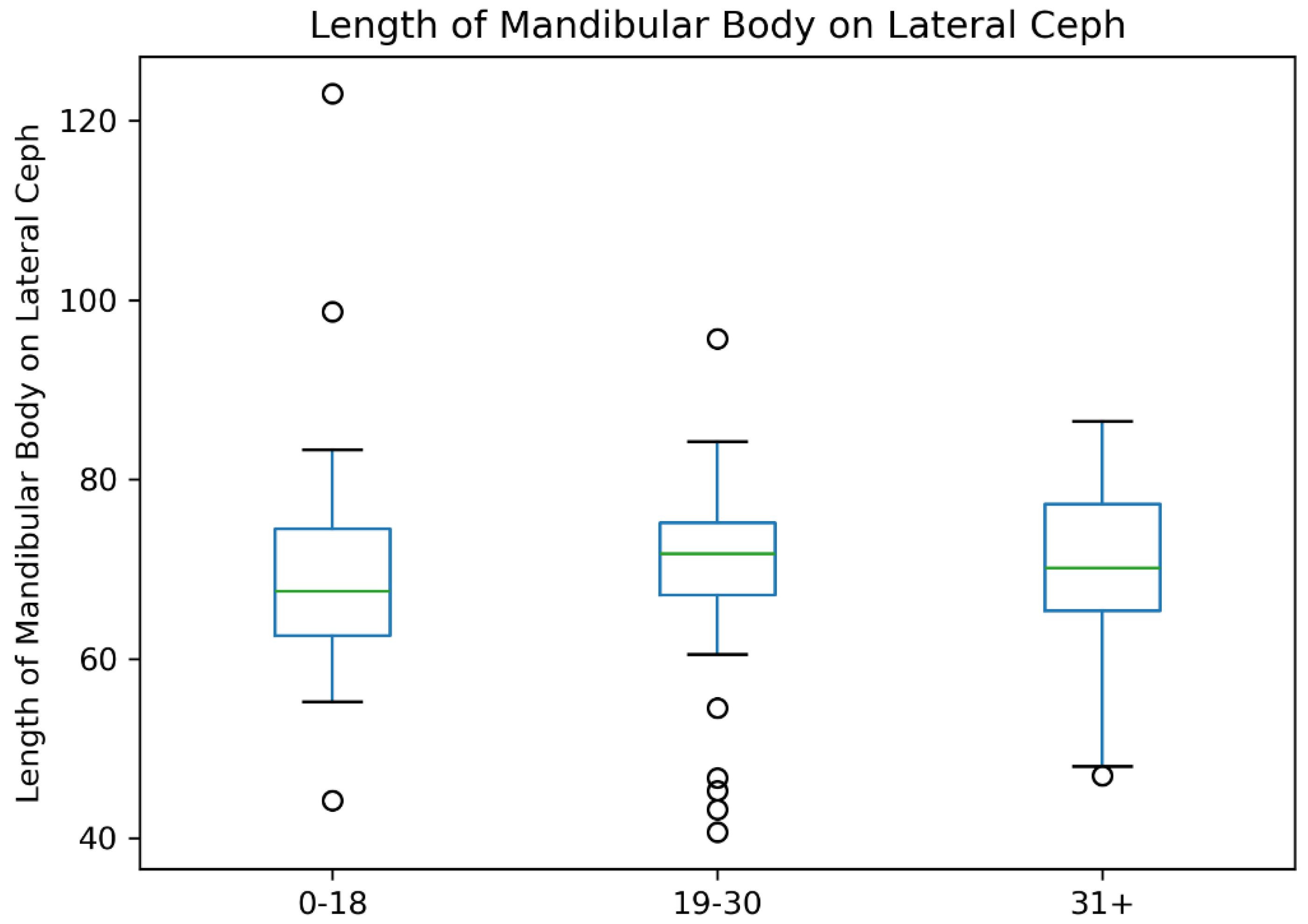

| 5 | MANDIBULAR BODY LENGTH | (mm) The distance between point Go and point M [21]. |

| Characteristic | N = 128 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female (F) | 67 (52%) |

| Male (M) | 61 (48%) |

| Age | 21 (16, 29) |

| FMA | 22 (17, 25) |

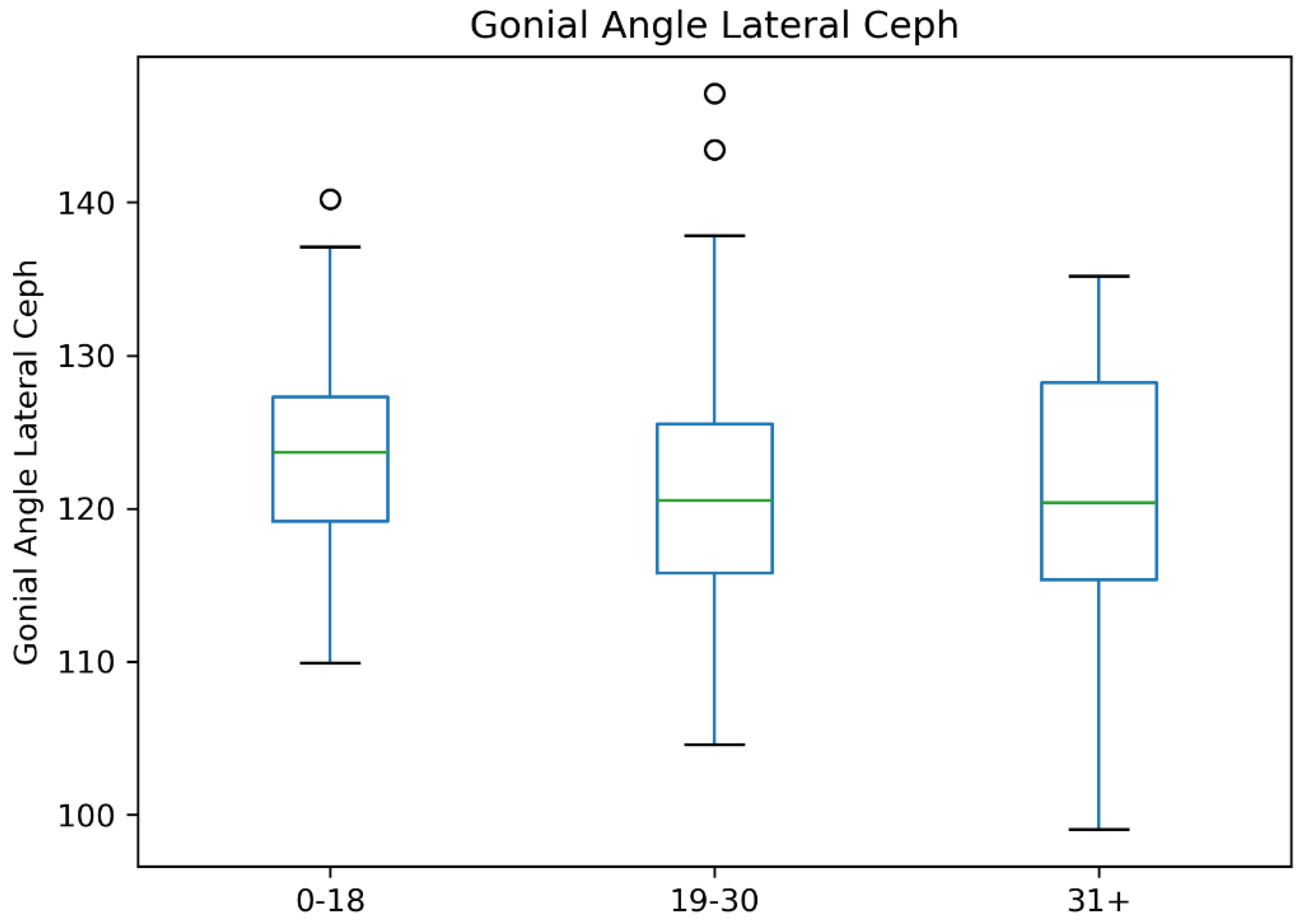

| Gonial Angle (Lateral Ceph) | 121 (116, 127) |

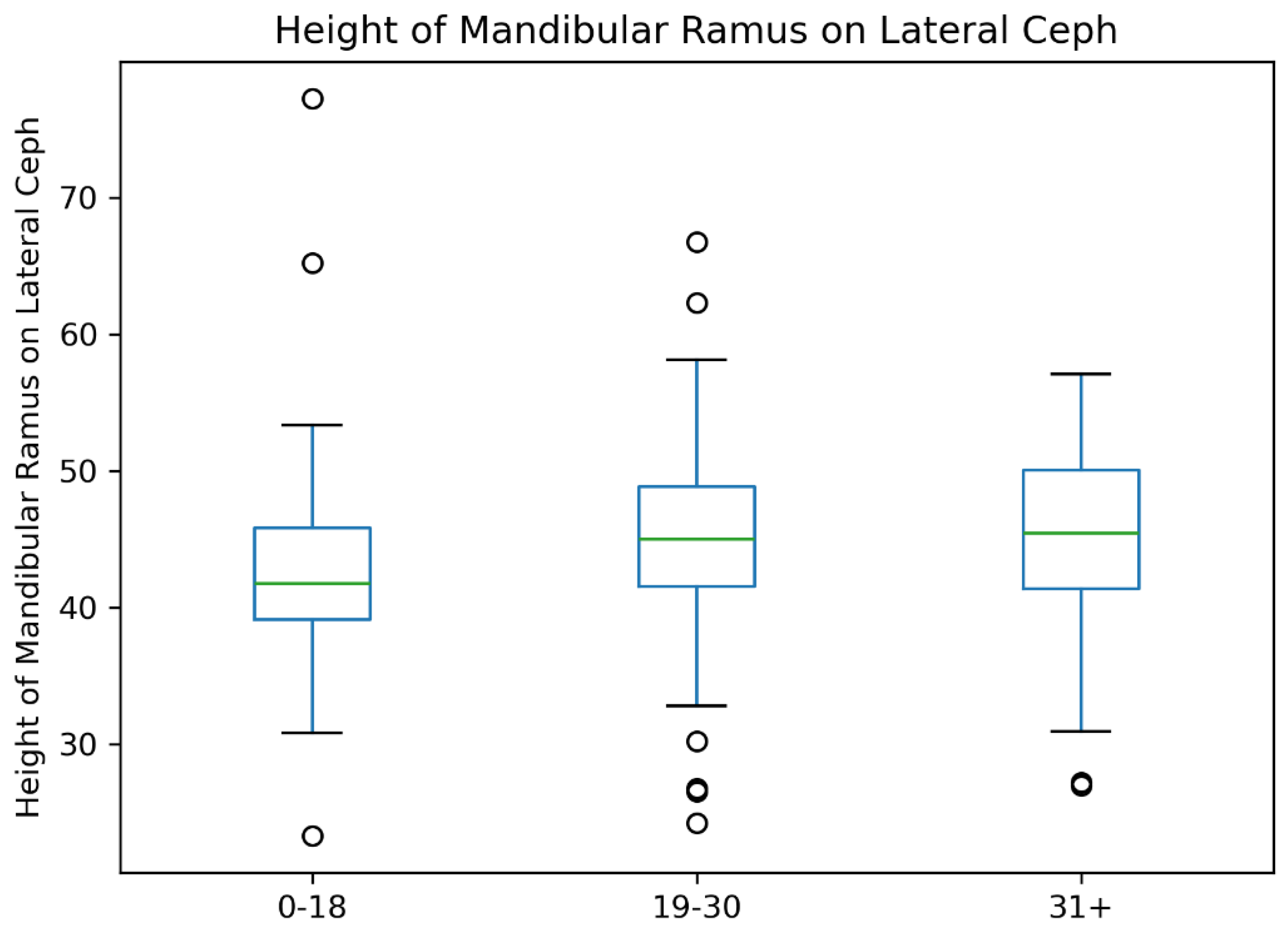

| Mandibular Ramus Height (Lateral Ceph) | 44 (41, 48) |

| Mandibular Body Length (Lateral Ceph) | 70 (65, 76) |

| Gonial Angle Right (OPG) | 121 (116, 127) |

| Gonial Angle Left (OPG) | 122 (117, 127) |

| Mandibular Ramus Height Right (OPG) | 44.0 (40.0, 47.0) |

| Mandibular Ramus Height Left (OPG) | 43 (40, 48) |

| Mandibular Body Width Right (OPG) | 71 (67, 76) |

| Mandibular Body Width Left (OPG) | 71 (67, 75) |

| Variable | N | Female (F) (N = 67) (Median, Q1, Q3) | Male (M) (N = 61) (Median, Q1, Q3) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 128 | 21.0 (17.0, 26.0) | 23.0 (15.7, 30.7) | 0.42 |

| FMA (°) | 121 | 21.0 (16.0, 25.0) | 22.0 (18.7, 26.0) | 0.5 |

| Gonial Angle (Lateral Ceph) (°) | 128 | 120.4 (115.4, 125.2) | 123.4 (118.5, 128.9) | 0.01 |

| Mandibular Ramus Height (Lateral Ceph) (mm) | 128 | 41.9 (38.5, 45.0) | 46.9 (42.0, 52.1) | <0.01 |

| Mandibular Body Length (Lateral Ceph) (mm) | 128 | 69.8 (64.7, 73.9) | 73.0 (66.7, 77.3) | 0.01 |

| Gonial Angle Right (OPG) (°) | 128 | 120.0 (114.9, 125.8) | 123.0 (117.0, 129.0) | 0.01 |

| Gonial Angle Left (OPG) (°) | 128 | 123.0 (116.2, 125.0) | 122.0 (117.0, 129.0) | 0.2 |

| Mandibular Ramus Height Right (OPG) (mm) | 126 | 42.0 (39.0, 45.0) | 46.0 (42.7, 50.0) | <0.01 |

| Mandibular Ramus Height Left (OPG) (mm) | 126 | 42.0 (38.0, 44.3) | 47.0 (42.0, 51.0) | <0.01 |

| Mandibular Body Width Right (OPG) (mm) | 128 | 69.5 (66.3, 74.0) | 73.7 (69.1, 77.2) | <0.01 |

| Mandibular Body Width Left (OPG) (mm) | 127 | 70.0 (66.0, 74.1) | 72.0 (69.0, 76.3) | 0.02 |

| Variable | Ramus Height Lateral Ceph | Ramus Height Right OPG | Ramus Height Left OPG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ramus Height Lateral Ceph | — | ||

| Spearman’s rho | — | 0.901 (95% CI: 0.863, 0.930) | 0.844 (95% CI: 0.785, 0.888) |

| p-value | — | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** |

| Ramus Height Right OPG | — | ||

| Spearman’s rho | — | 0.800 (95% CI: 0.725, 0.855) | |

| p-value | — | <0.001 *** | |

| Ramus Height Left OPG | — |

| Variable | Gonial Angle Lateral Ceph | Gonial Angle Right OPG | Gonial Angle Left OPG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gonial Angle (Lateral Ceph) | — | ||

| Spearman's rho | — | 0.946 *** | 0.858 *** |

| Degrees of Freedom (DF) | — | 126 | 126 |

| p-value | — | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Gonial Angle Right (OPG) | — | ||

| Spearman's rho | — | 0.811 *** | |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | — | 126 | |

| p-value | — | <0.001 | |

| Gonial Angle Left (OPG) | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).