1. Introduction

General relativity (gr) stands as the preeminent theory of gravity, extensively corroborated through its capacity to elucidate an array of astrophysical phenomena. According to the uniqueness theorems, black holes are characterized exclusively by mass, angular momentum, and electromagnetic charge, often encapsulated by the "no-hair" theorem. Nevertheless, whether black holes are described by the Kerr solution or alternative solutions within or beyond the gr framework remains an open question.

Evidence from observations coming from a variety of cosmological probes has perpetually highlighted to the existence of dark energy, a cryptic entity responsible for the universe’s accelerating expansion. The cosmological constant provides a simple and elegant explanation for observed acceleration, thereby presenting an appealing option for further investigation. Furthermore, it is feasible to presume that black holes are slightly charged, making it worthwhile to investigate how this affects their observational characteristics. The Kerr Newmann de Sitter solution is a black hole model that takes into consideration both charge and the cosmological constant. This research project seeks to examine the effect of charge and the cosmological constant on the black hole photon ring.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) collaboration has recently conducted groundbreaking interferometric observations of the supermassive black holes M87* and Sagittarius

A* (Sgr

) at the centres of Messier 87 and the Milky Way, respectively [

1] and [

2]. These observations have provided unprecedented insights into the emission structure on horizon scales. The relentless pursuit of enhanced image resolution and unprecedented levels of detail persists, propelled by the ongoing endeavors of the next generation EHT [

3]. Through these endeavors, the next generation EHT aims to achieve the remarkable feat of capturing dynamic and high-resolution cinematic representations of black holes. This raises the questions:

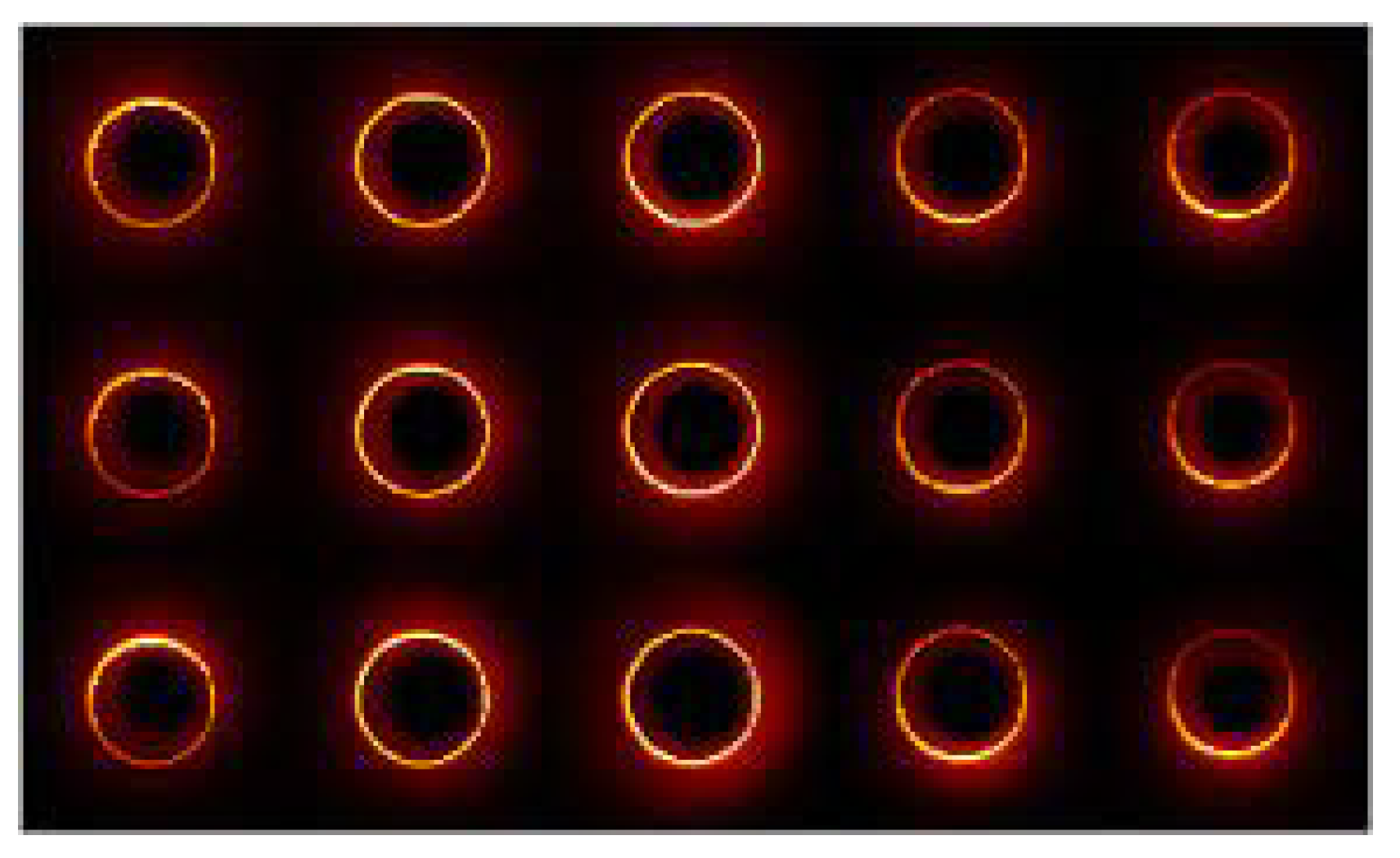

State of the art simulations employing general relativistic magnetohydrodynamics (grMHD) demonstrate the appearance of a black hole if high resolution was achieved is dominated by a conspicuous presence of a thin and bright ring, aptly christened the "photon ring", as illustrated in

Figure 1.

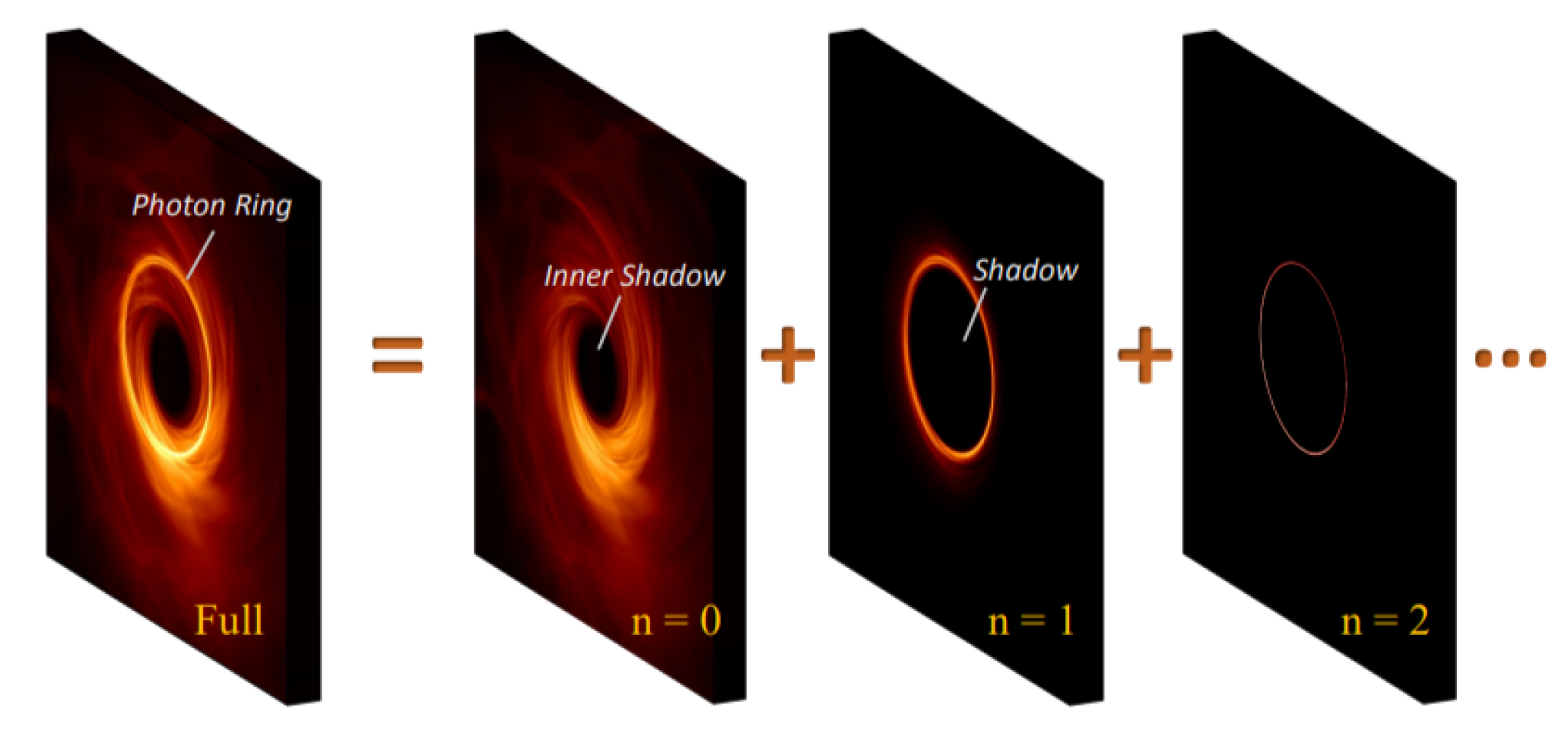

The existence of the photon ring is a categorical outcome of the strong gravity of the black hole, rendering it impervious to the details of the astrophysical source profile around the black hole. Calculations within the framework of gr unmask a captivating revelation: the photon ring, rather than being a single continual entity, unveils itself as a nested sequence of self-similar subrings. as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The subsequent subrings are exponentially demagnified and progressively converge to the critical curve. The very essence of the critical curve’s geometry is a candid manifestation of the black hole’s mass, spin, and the observer’s inclination, all intricately interwoven within the framework of gr. If the black hole’s metric encompasses additional parameters, the critical curve may undergo deviations from its gr archetype. Despite the undeniable significance of the critical curve, it is in itself not directly observable. Notably, unlike the critical curve, the photon ring bestows upon us a remarkable advantage—it is directly observable. Therefore, delving into the investigation of the photon ring unveils a captivating arena to peer deeply into the gravity’s nature in the vicinity of black holes both theoretically and experimentally.

Observational evidence from a wide range of cosmological probes [

5,

6] has consistently pointed to the existence of dark energy, an elusive entity responsible for the universe’s accelerating expansion. Because it provides a simple and elegant solution to the observed acceleration, the cosmological constant is a natural candidate for deciphering this phenomenon. Besides, it is plausible to presuppose that black holes are somewhat charged, making it noteworthy to study how this affects their observational features. The Kerr Newmann de Sitter solution is a black hole solution that takes into account both charge and cosmological constant. The goal of this paper is to investigate the effect of charge and the cosmological constant on the black hole photon ring.

This work is organized as follows: In

Section 2, we begin with a brief overview of the Kerr Newmann de Sitter solution. In

Section 3, we proceed to investigate direct images, lensing rings and the photon rings. Further, we explore the critical parameters governing the structure of the images in

Section 4 and give a conclusion of our results in

Section 5. In the

Section 5, we present the relevant calculation framework that has been used to obtain the solutions of various section.

2. Overview of Kerr Newmann De Sitter Solution

Kerr-Newman-de-sitter (KNDs) is one of the most general stationary, axially symmetric type D solutions of the Einsteins-Maxwell equations in general relativity that describes the spacetime geometry in the region surrounding an electrically charged, rotating Black hole. It generalizes the Kerr-Newman metric by taking into account the cosmological constant

. In Boyer Lindquist coordinates the metric is given by the line element [

7],

where

Rescaled units are used so that the speed of light and gravitational constants are normalized (c=1, G=1). The metric depends on four parameters, namely the mass

m, the spin

a, a parameter

for electric and magnetic charge

and the cosmological constant

. For

, (

1) reduces to the Reissner–Nordstrom–de Sitter metric [

8] while in the uncharged case, we have the Kerr-de Sitter (Kds) (

,

) or Schwarzschild–de Sitter (

, a = 0) solutions [

9].

Four fundamental quantities determine the equations of motion of photons: the Lagrangian, Carter’s constant

Q, energy

E and the angular momentum in the

z axis

.

and

E are due to the axial symmetry and stationarity of the black hole solution, while

Q is associated to the hidden symmetry in KNDs spacetime. In the case of photons, only the sign of

E has a physical meaning, hence the quantities

,

Q and

E can be reparametrized as,

Null geodesics in KNDs space time in terms of these parameters are then given by,

To decouple (

3) - (

5), the Mino time parameter

is introduced and defined as:

With which the decoupled equations become,

where

With the subscripts

o and

s denoting the observer and the source respectively and the Mino parameter is related to the integrals through the relation;

Solutions to these integrals have been expressed in terms of Jacobi elliptic functions in

Appendix G.

2.1. Analysis of the Angular Potential

In this subsection, we will do a brief analysis of the angular potential to get a grasp of various properties that will be useful in the subsequent sections. The angular potential has been given in Equation (11). Making use of the substitution

on Equation (11) results in,

Solving for the roots gives,

where

Thus, the roots in terms of

will be given by inverting

which results in,

Equation (17) represents the turning points that a photon encounters in the latitudinal direction. The nature of the roots of Equation (17) can be investigated by using the relation,

If then whereby and . Mathematically, this implies that and will be real while and will be complex. Physically, the photon will oscillate between and which is the ordinary type of motion. In ordinary type of motion, the photon crosses the equatorial plane each time as . Furthermore, if , then which implies that and . This means that all the roots will be real. In this case, the photon will either oscillate between and or and . This type of motion is referred to as vortical motion. In vortical motion, the photon is confined on one hemisphere since and or and . In the case that , then which gives rise to motion confined on the equatorial plane.

2.2. Analysis of the Radial Potential

In this subsection, we will conduct an analysis of the radial potential to get insights on the important features that arise as a result of this potential. Focus will be given to the aspects that are relevant to the subsequent sections. The radial potential is as expressed in Equation (10) and it’s roots have been calculated in

Appendix F. The roots represent the turning points that a photon encounters in the exterior of a black hole before escaping towards an observer or if there is no turning point in the exterior, the photon will plunge into the black hole. In the special case that a photon is bound at a constant radius in the exterior of a black hole, we have that

. This is the mathematical condition for the existence of bound photon orbits. Using this condition, the constants of motion for bound photon orbits can be analytically obtained as,

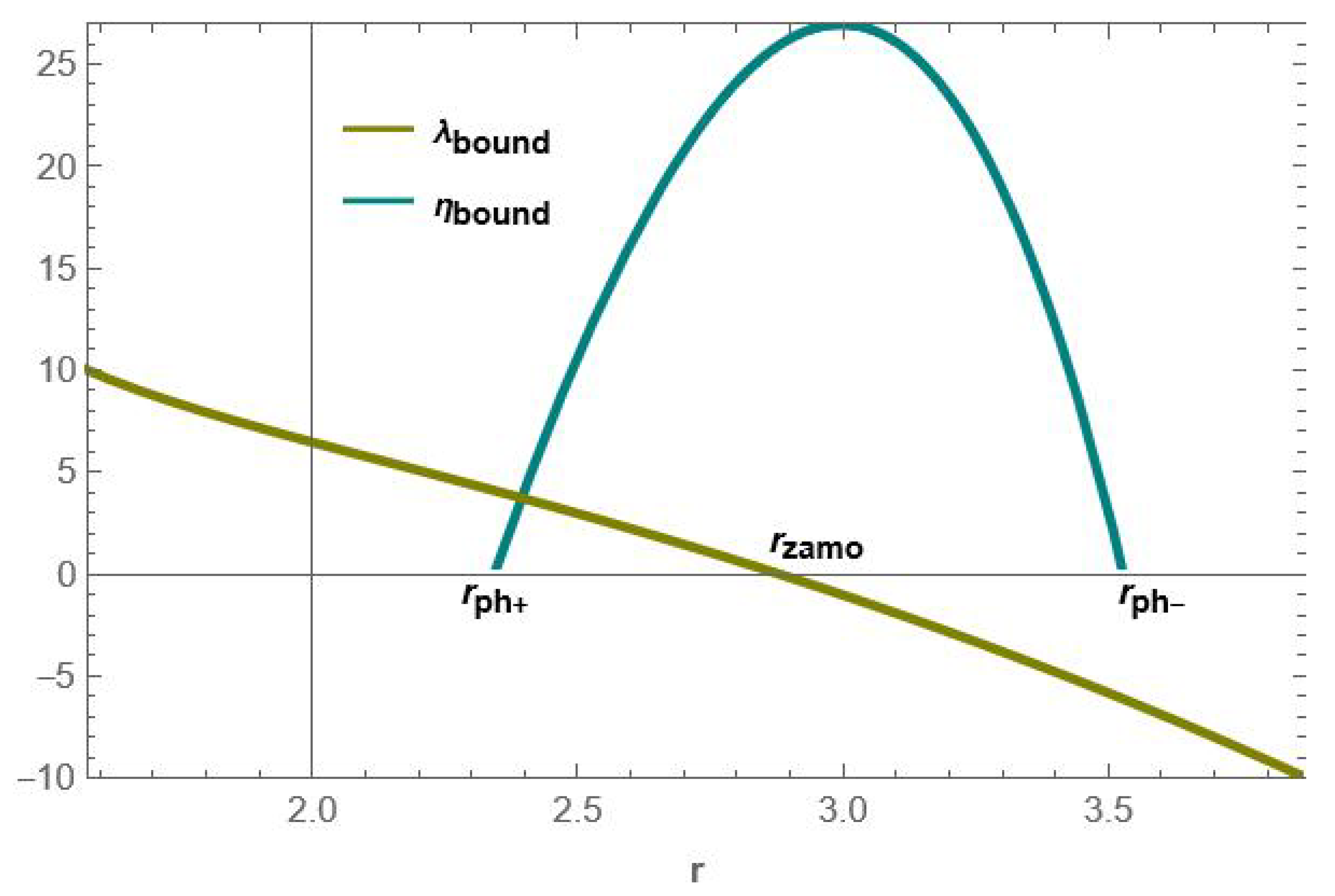

Using these constants of motion, Equation (19) and Equation (20), various important aspects of bound photon orbits can be obtained. An illustration of these parameters is as shown in

Figure 3.

The general behavior of is that it monotonically increases from zero to a maximum where it again begin to monotonically decrease to zero again. The points where form the lower and upper bounds in the exterior of a black hole where bound photon orbits can exist. These two radii, where , are referred to as the radius of equatorial bound photon orbits. We respectively denote them as and . The region is known as the photon region.

The parameter on the other hand monotonically decreases from positive values to negative values. The radial point where these parameter vanishes is known as the radius of the zero angular momentum orbit (). This radial point marks the region of transition of the orbits from co-rotating to counter rotating orbits. Therefore, in the region of co rotating orbits, , photons move with positive angular momentum in the azimuthal direction. On the other hand, in the region of counter rotating orbits, , photons move with negative angular momentum in the z direction. By co rotating we mean that the photons move on orbits that are in the same direction as the direction of rotation of the black hole. By counter rotating, we mean that photons move on orbits that are aligned in an opposite direction to the rotation of the black hole.

3. Direct Images, Lensing Rings and Photon Rings

Our approach of constructing the direct images, lensing rings and photon rings will consider locally static observers in the exterior of the KNDs black hole. Specifically, we will consider an observer with a frame of the form [

10],

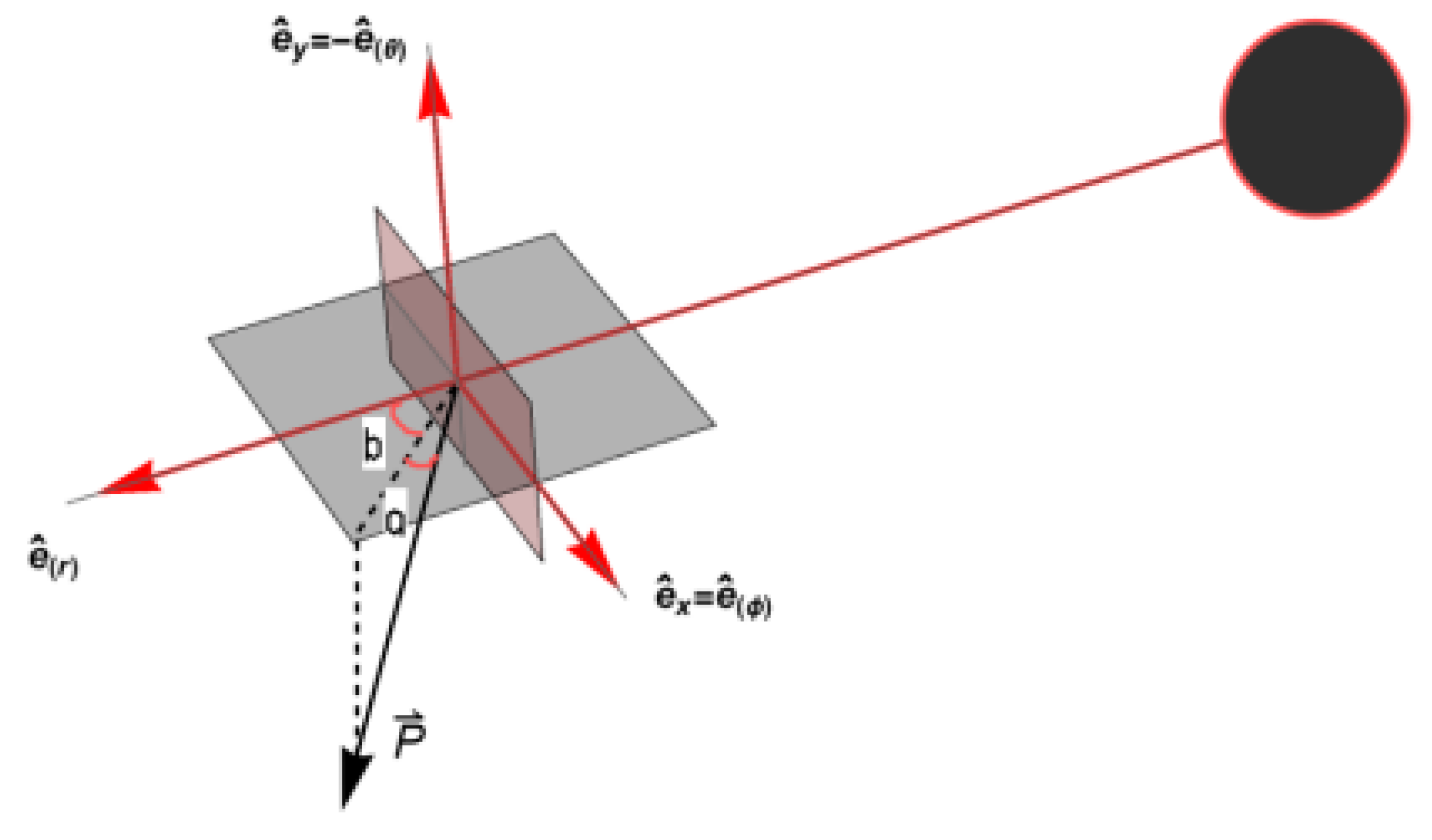

An illustration of this observer’s frame is as shown in

Figure 4.

Here,

represents the timelike vector where as

,

and

are the three basis vectors which correspond to the observers motion in the three spatial dimensions. The observer represented by the frame defined by (

22) has zero angular momentum owing to the fact that

. As a result, this observer is also referred to as the zero angular momentum observer.

The photon’s four momentum

when projected on the basis vector results in directly measurable quantities in the observer’s local frame [

11],

The observational angles

a and

b are then defined in terms of the four momenta as [

10,

12],

Considering that our observer is located at a distance

from the black hole, then it’s apparent position in terms of Cartesian coordinates is expressed as [

13],

Substituting the relations in Equation (24) as well as for

from Equations (

3)-(

5) into Equation (25) gives,

where,

Furthermore, it is convenient to express these Cartesian coordinates in terms of

and

which are the parameters depending on the constants of motion of the photons. Depending on the chosen values of

and

, the photons will occupy unique regions on the

plane. For instance, when

and

are such that the photons follow spherical null geodesics, then the corresponding shape on the

plane is a nearly circular image which is the so called critical curve. Besides, our goal is to conduct the ray tracing analytically, it is then important that we have Equation (26) in terms of

and

since the equations of null geodesics depend on these two parameters instead of

x and

y. Thus, making

and

the subject in Equation (26) gives,

Up to this point, we have the general expressions of the constants of motion in terms of the black hole parameters, the observer position and the Cartesian coordinates of the observer. It is important noting that these expressions are different from those derived in Equation (20) and Equation (19). This is because Equation (20) and Equation (19) defines only the special case when photons are bound at a constant radius while Equation (27) and Equation (28) are general to any type of photon orbit.

To obtain the direct images, lensing rings and photon ring, we will need to account for every turning point the photons make as they cross the equatorial plane. We consider photons crossing the equatorial plane as our approach is to obtain images of equatorial disks.

Thus, to achieve accurate analytic ray tracing, it is crucial to present the solutions in terms of the turning points that photons undergo [

12]. We then highlight the angular integrals in terms of the various turning points encountered by photons in the

direction. This approach is enhanced by the establishment of definitions and signs that are beneficial for the analysis [

14],

The parameter

m will denote the number of turning points. Furthermore,

and

denote the polar momentum at the endpoints

and

of the geodesic, respectively. By using the defined signs, the angular integrals unpack as [

14],

Using Equation (29) alongside the general solutions in Equation (A51), we have,

where

. At this point, the relation Equation (13) becomes important as we can now directly construct the images applying the analytical expression,

We will then investigate the images of the equatorial disks for different values of m using the analytical expression Equation (31).

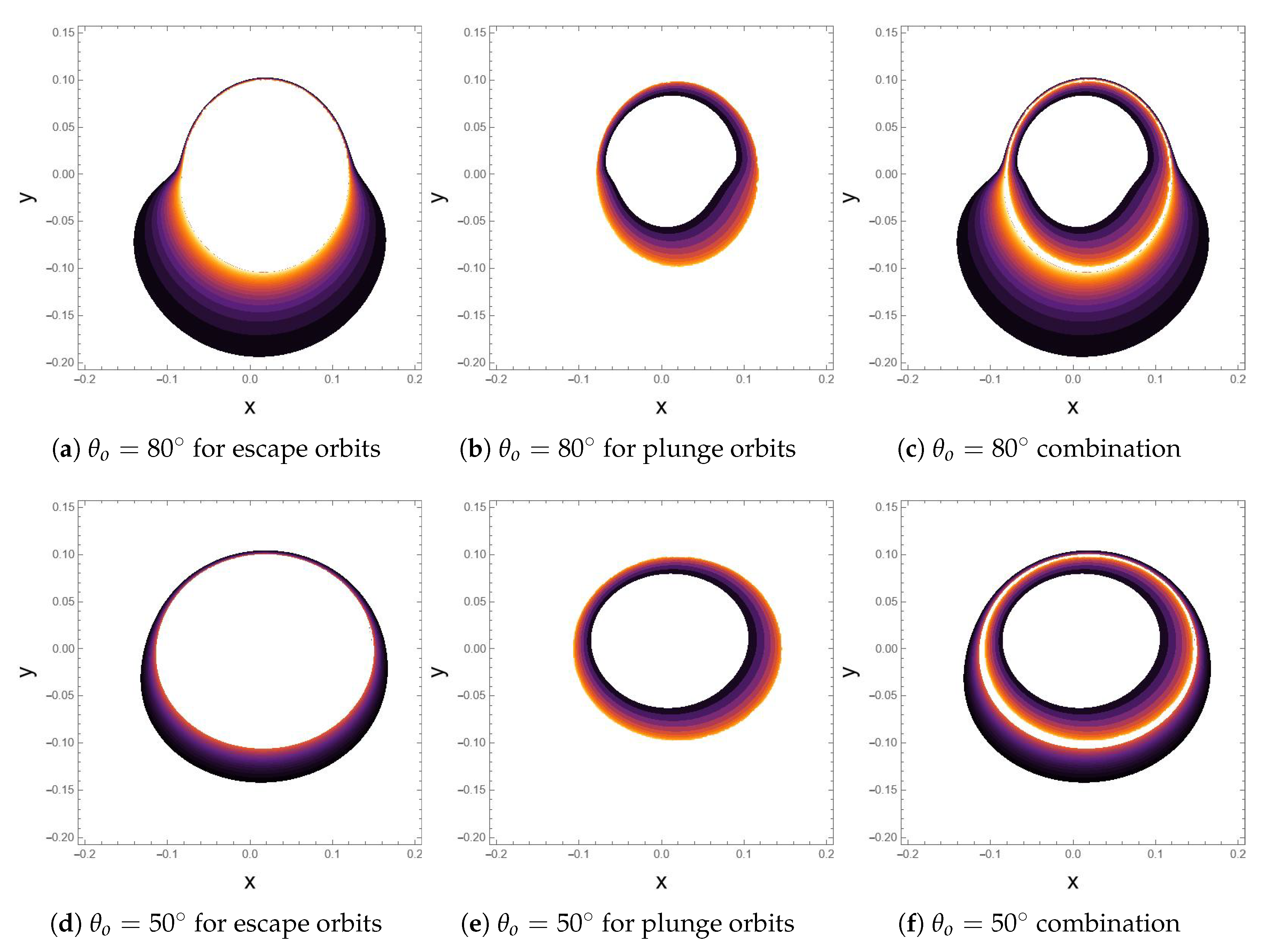

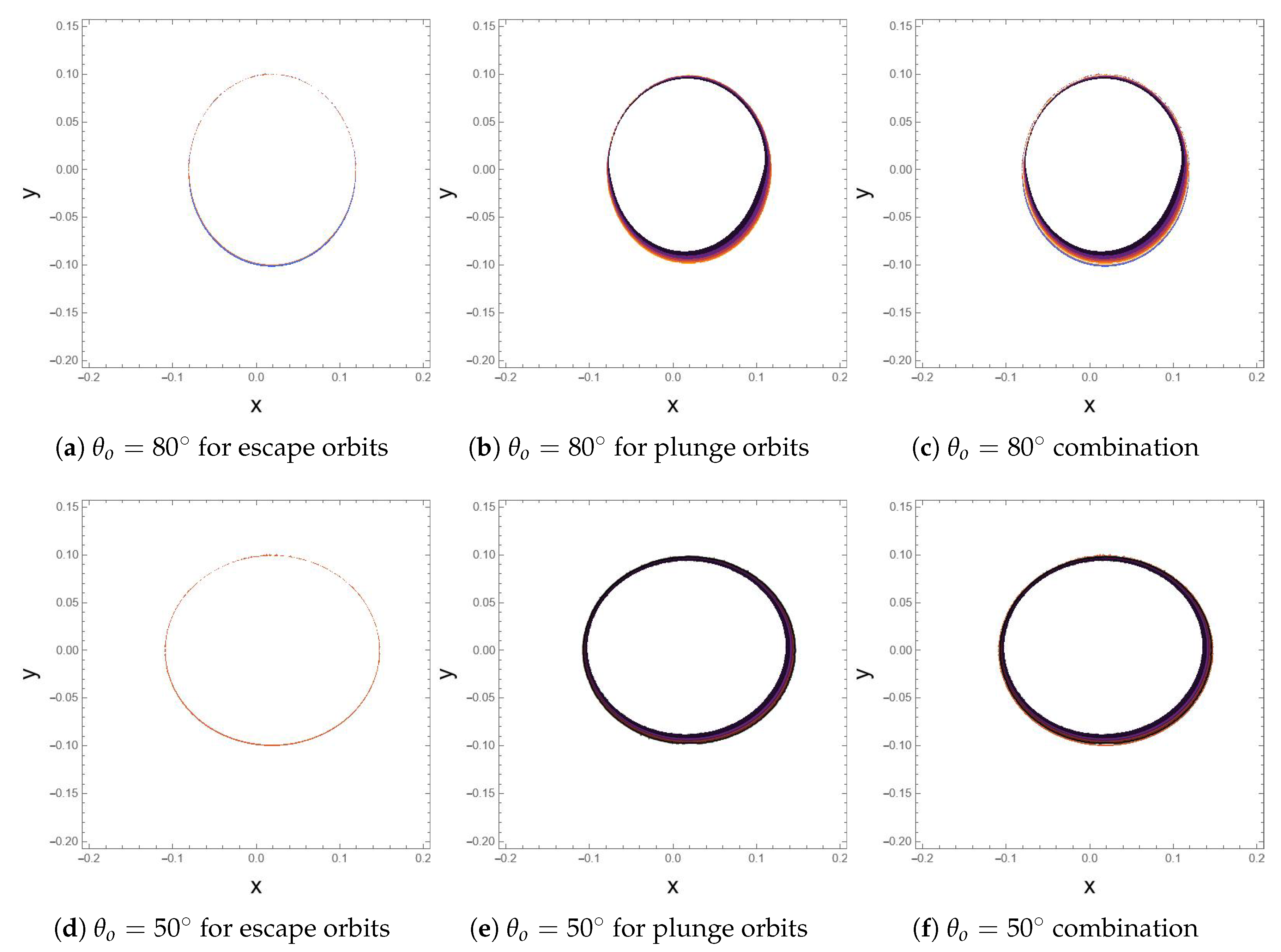

In

Figure 5, we investigate the images for

given two different angles of inclination,

and

. An observer detects these images after photons have crossed the equatorial disk once. The images for escape orbits are those images for which photons encounter a turning point in the exterior of a black hole and escape towards an observer. This region of the image forms the outer image while the region of the image for plunge orbits is that which arises from photons that do not encounter a turning point in the exterior of a black hole. As a result, these photons plunge into the black hole forming the inner region on the observers screen. When the angle of inclination is lower, i.e

, the images appear to be nearly circular as compared to

where they deviate so much from circularity. After just one half orbit, the orbits are weakly lensed hence the resulting images appear thick as can be seen from the images in these plots.

In

Figure 6, we investigate the images for

for two different angles of inclination,

and

. An observer detects these images after photons have crossed the equatorial disk twice. When

, the photons are on orbits that have undergone extreme lensing due to strong gravity. The resulting images appear extremely demagnified as compared to the images for which

. Images for which

comprises the photon ring. Since these images appear after photons have crossed the equatorial disk a number of times, their corresponding arrival time on the observer screen are different.

4. Analysis of Critical Parameters

In this section, we will derive the relations for time delay, the Lyapunov exponent, and the change in azimuthal angle, which are the parameters governing the arrival time, demagnification, and rotation of subsequent images on the observer’s screen. Besides, we will conduct an exploration of the influence of charge on these parameters as well as the cosmological constant. It is worthy noting that subsequent images occur after photons make extra half orbits around the black hole. Thus, for every extra half orbit a photon makes around the black hole, a different image that is exponentially demagnified appears on the observers screen. As a result, to express the critical parameters analytically, it is physically plausible to evaluate the angular integrals between two turning points as this corresponds to half an orbit around the black hole.

4.1. Time Delay

Derivation of time delay

will involve evaluation of Equation (9) over half an orbit. Solutions to the intergrals over half orbits have been expressed in Equation (A55)-Equation (A57). As a result, Equation (9) becomes,

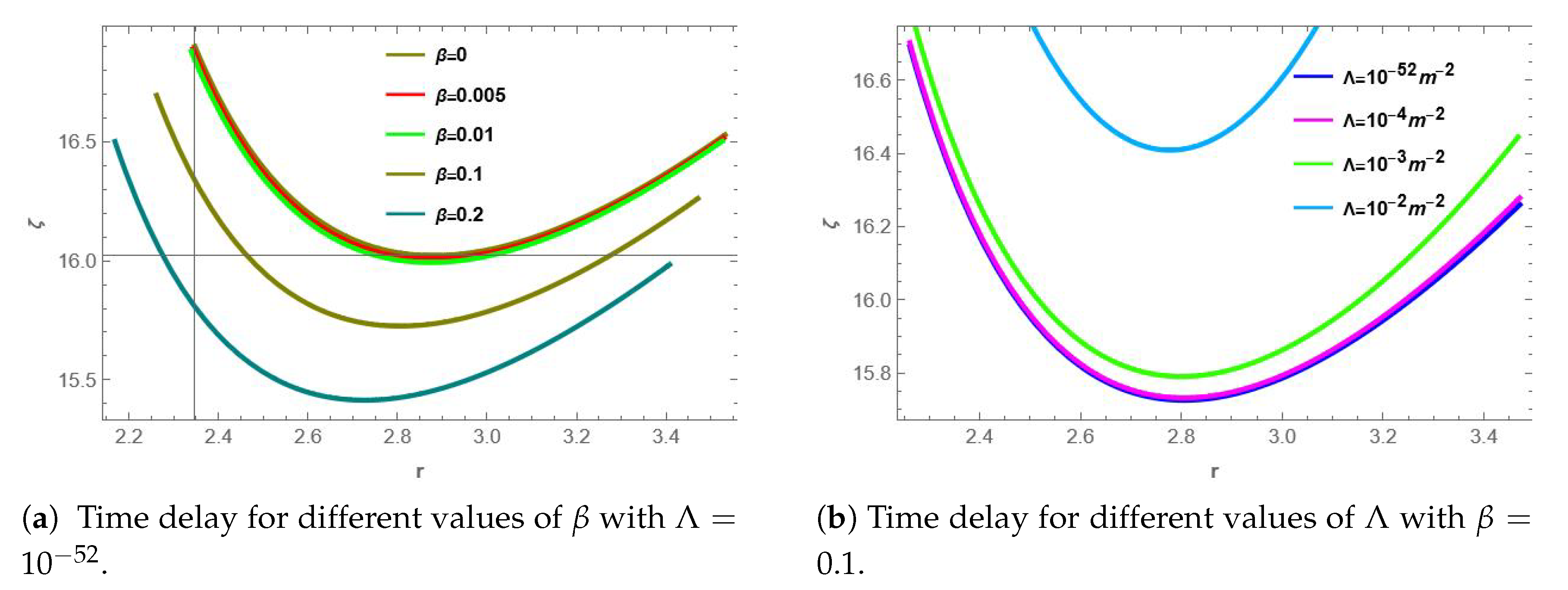

We note that the radial integral in Equation (9) has been expressed in terms of the angular integral through the relation Equation (13), resulting in the appearance of in the first term of Equation (32).

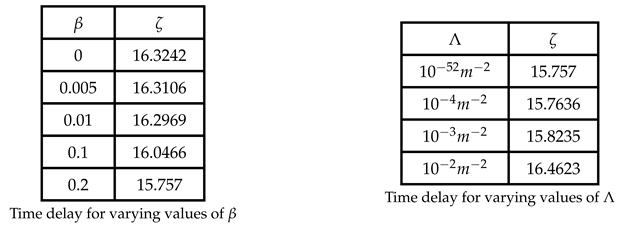

Figure 7 shows an illustration of how

varies with

and

. From the illustrations, it is clear that an increase in charge leads to a decrease in

. For instance, when

, we have that

while when

, we have that

. Therefore, in a highly charged KNDs black hole, photons would take less time to complete half orbits as compared to a less charged KNDs black hole. This then implies that subsequent images of a highly charged KNDs black hole will be detected faster by an observer. However, in the case of varying the cosmological constant, an increase on the value of

results to an increase on

. Thus, the implication of a larger cosmological constant would be that photons would take more time to complete half orbits. This would then slow down the time of detection of subsequent images by an observer.

Generally, in both cases,

monotonically decreases to a minimum at a value of

r, that correspond to the radial position of the zero angular momentum orbit, before beginning to increase monotonically. As a result, when the black hole has spin, photons take different times to complete half orbits depending on their radial position. In the case of spin zero (

),

no longer varies but rather takes specific values. This is owing to the fact that when black hole spin is zero, the photon region reduces to a photon shell. Even so, as shown in

Table 1, an increase in charge results in a decrease on the time taken for orbits to complete half orbits. Which corresponds to an observer detecting subsequent images faster when a RN black hole is highly charged. Besides, an increase on the cosmological constant results in an increase on the time taken for photons to complete half orbits. This implies that with a higher value of the cosmological constant, subsequent images of a RN black hole will be delayed more from being detected by an observer.

4.2. Lyapunov Exponent

The Lyapunov exponent,

, gives the rate of exponential deviation of nearly bound orbits from the bound orbits. Denoting the radial coordinate of a bound photon as

and considering a small deviation

. Then the radial coordinate of a nearly bound photon orbit will be

. The next step is to perform a Taylor series expansion of the radial potential with respect to this deviation. This will result in,

Equation (33) provides an approximation of a radial potential for a nearly bound photon orbit. We limit our consideration to terms up to the second order of

as higher-order terms become extremely infinitesimal. Furthermore,

which is basically the condition for bound photon orbits. This condition implies that the first two terms of Equation (33) will vanish. By defining

as the initial deviation and

as the deviation after

n half orbits, then after

n half orbits, we have that,

Simplifying Equation (34) results in,

Equation (35) gives the rate at which nearly bound photon orbits deviate from the bound photon orbits. This property gives rise to the exponential demagnification of the subsequent images of the photon ring.

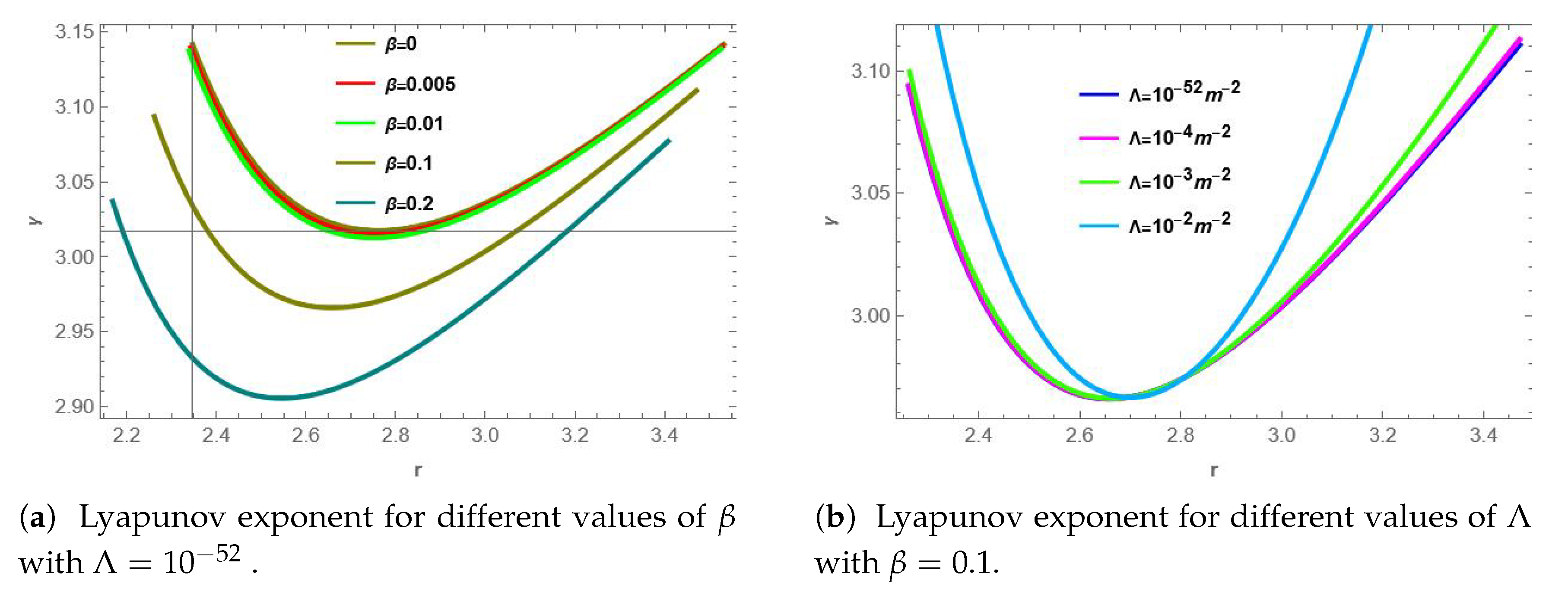

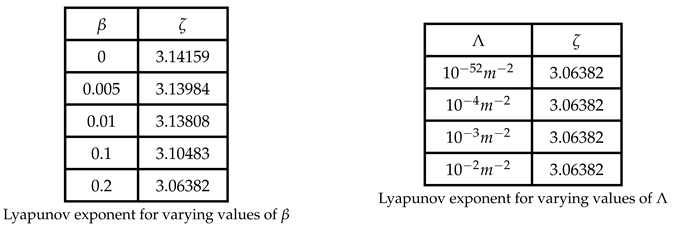

As illustrated in

Figure 8, an increase in charge results to a decrease in the rate of exponential deviation of nearly bound photons from bound photons. Thus, for a highly charged KNDs black hole, subsequent images will appear to be less demagnified as compared to the less charged KNDs black hole. Besides, with increasing value of the cosmological constant, the rate of exponential deviation also increases. This implies that with a higher value of

, subsequent images will appear more demagnified as compared to smaller values of

.

In the case of spin zero, the Lyapunov exponent is not varying with radius as this case lacks a photon region. The values of the the Lyapunov exponent in the case of spin zero are as illustrated in

Table 2. As shown, when the value of charge increases, the Lyapunov exponent decreases implying that the rate of deviation of nearly bound photon orbits decrease. This corresponds to a decrease on the magnitude of demagnification of subsequent images. However, a change on the cosmological constant appears to have no effect on the rate of deviation of nearly bound photon orbits as shown on the second table.

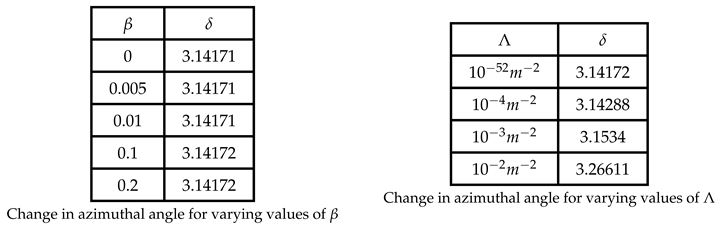

4.3. Change in Azimuthal Angle

The change in azimuthal angle,

, controls the rotation of subsequent images on the observers screen. This parameter is derived by evaluating Equation (8) over half orbits. The solutions of the respective integrals evaluated over half orbits have been given on Equation (A55)-Equation (A57). Substituting these solutions into Equation (8) gives,

Equation (36) is the analytical expression with which to explore the amount of rotation subsequent images experience on the observer’s screen.

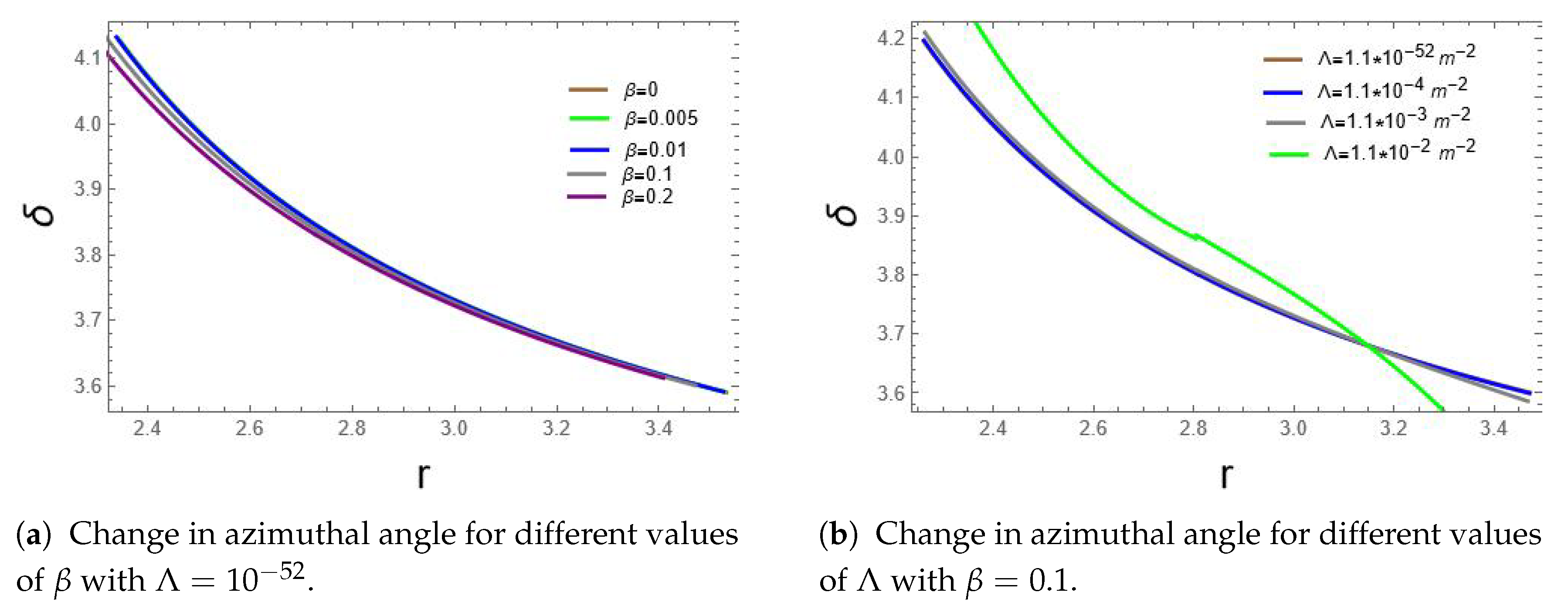

As illustrated

Figure 9 the change in azimuthal angle is monotonic and indistinguishable for small values of cosmological constant. However, as

increases or equals

there is a considerable change implying that for a KNDs black hole an increase in

leads to a greater change in azimuthal angle. For prograde orbits as

the change in azimuthal angle increases significantly and tends to decrease for retrograde orbits i.e beyond the

. Furthermore, the change in azimuthal angle is also monotonic for different charge values. For prograde orbits, an increase in charge leads to a decrease in the change in azimuthal angle as is illustrated in the figure whereas for retrograde orbits the change in azimuthal angle for different values of charge is insignificant. From

Table 3 for the case of spin zero, change in azimuthal angle does not vary with changes in charge but remains constant. This is brought about by the absence of frame-dragging for a non-rotating black hole making the change in azimuthal angle evolve symmetrically. On the other hand an increase in

leads to an increase in the change in azimuthal angle though at a slow rate.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we have done an analytic investigation of the imprints of charge on the photon ring of a KNDs black hole. Our analytic solutions of the integrals has made use of the Jacobi Elliptic integrals. We have analyzed images of equatorial disks for varying values of m, which we use to denote the number of times a photon crosses the equatorial plane. When , the photons are weakly lensed and the images appear thick. However, as m increases, the photons are strongly lensed which results in highly demagnified images referred to as the photon ring. Besides, when , the images appear more circular for smaller angles of inclination, i.e , and deviate extremely from circularity at higher observer inclination such as .

We have also investigated the imprints of charge on the critical parameters governing the exponential demagnification and arrival time of the subsequent images. These are the time delay , Lyapunov exponent and change in azimuthal angle . We observe that an increase in charge leads to a decrease in the time delay. Therefore, in a highly charged KNDs black hole, photons would take less time to complete half orbits as compared to a less charged KNDs black hole. This then implies that subsequent images of a highly charged KNDs black hole will be detected faster by an observer. However, in the case of varying the cosmological constant, an increase on the value of results to an increase on . Thus, the implication of a larger cosmological constant would be that photons would take more time to complete half orbits. This would then slow down the time of detection of subsequent images by an observer. Besides, an increase in charge results to a decrease in the rate of exponential deviation of nearly bound photons from bound photons. Thus, for a highly charged KNDs black hole, subsequent images will appear to be less demagnified as compared to the less charged KNDs black hole. Besides, with increasing value of the cosmological constant, the rate of exponential deviation also increases. This implies that with a higher value of , subsequent images will appear more demagnified as compared to smaller values of .

Appendix F. Calculation of Roots of the Radial Potential

In this appendix, we illustrate the Ferrari’s method with which we use to calculate the roots of the radial potential. In doing so, we express Equation (10) as,

The coefficients in (A37) have been defined as,

Since Equation (A37) is a quartic polynomial, the Ferrari’s method gives the general form for its roots as,

In Equation (A39),

is a root of the resolvent cubic of (A37) and can be obtained by first re writing (A37) as,

We proceed to introduce a parameter

p into (A40) by adding the terms

on on the left and right hand side of Equation (A40) to obtain,

The right hand side of (A41) is a perfect square, thus obtaining it’s discriminant and equating it to zero gives,

Equation (A42) is the resolvent cubic of Equation (A37) whose roots are obtained by first expressing it as a depressed cubic through the relation

. This results in,

Cardano’s method gives the roots of (A43) where we select the real root,

We substitute

v back into our relation for

p to obtain

Finally, substituting (A45) into (A39) and distributing the signs results in the four roots of the radial potential,

Appendix G. Solutions to the Angular Integrals

In this section, we present the solutions of the angular integrals in terms of the Jacobi elliptic integrals of first kind, second kind and third kind. These integrals are respectively denoted as , , and .

We express the angular potential in terms of its roots as:

where,

In Equation (A50), we have made use of the substitution

while in Equation (A51) we have utilized

. In the same approach, the solutions fo the remaining integrals become,

These integrals when evaluated over half an orbit i.e performing integration over

to

or vice versa reduces to,

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| gr |

General relativity |

| Kds |

Kerr-de Sitter |

| KNDs |

Kerr-Newman-de-sitter |

| EHT |

Event Horizon Telescope |

| Sgr |

Sagittarius

|

References

- Akiyama, K.; et al. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 875, L1, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/1906.11238]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; et al. First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2022, 930, L12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; et al. Key Science Goals for the Next-Generation Event Horizon Telescope. Galaxies 2023, 11, 61, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2304.11188]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, K.; et al. First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. V. Physical Origin of the Asymmetric Ring. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 875, L5, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/1906.11242]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Discovery of a supernova explosion at half the age of the Universe and its cosmological implications. Nature 1998, 391, 51–54, [astro-ph/9712212]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high redshift supernovae. Astrophys. J. 1999, 517, 565–586, [astro-ph/9812133]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gwak, B. Bound on Lyapunov exponent in Kerr-Newman-de Sitter black holes by a charged particle. Journal of High Energy Physics 2024, 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, B. Thermodynamics and cosmic censorship conjecture in Kerr–Newman–de Sitter black hole. Entropy 2018, 20, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slanỳ, P.; Stuchlík, Z. Equatorial circular orbits in Kerr–Newman–de Sitter spacetimes. The European Physical Journal C 2020, 80, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.C.; Guo, M.; Chen, B. Shadow of a spinning black hole in an expanding universe. Physical Review D 2020, 101, 084041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.C.; Guo, M.; Chen, B. Shadow of a Spinning Black Hole in an Expanding Universe. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 084041, [arXiv:gr-qc/2001.04231]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omwoyo, E.; Belich, H.; Fabris, J.C.; Velten, H. Black hole lensing in Kerr-de Sitter spacetimes. The European Physical Journal Plus 2023, 138, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J.M. Timelike and null geodesics in the Kerr metric. Proceedings, Ecole d’Eté de Physique Théorique: Les Astres Occlus: Les Houches, France, August, 1972, 215–240 1973, pp. 215–240.

- Kapec, D.; Lupsasca, A. Particle motion near high-spin black holes. Classical and Quantum Gravity 2019, 37, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).