Submitted:

30 July 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

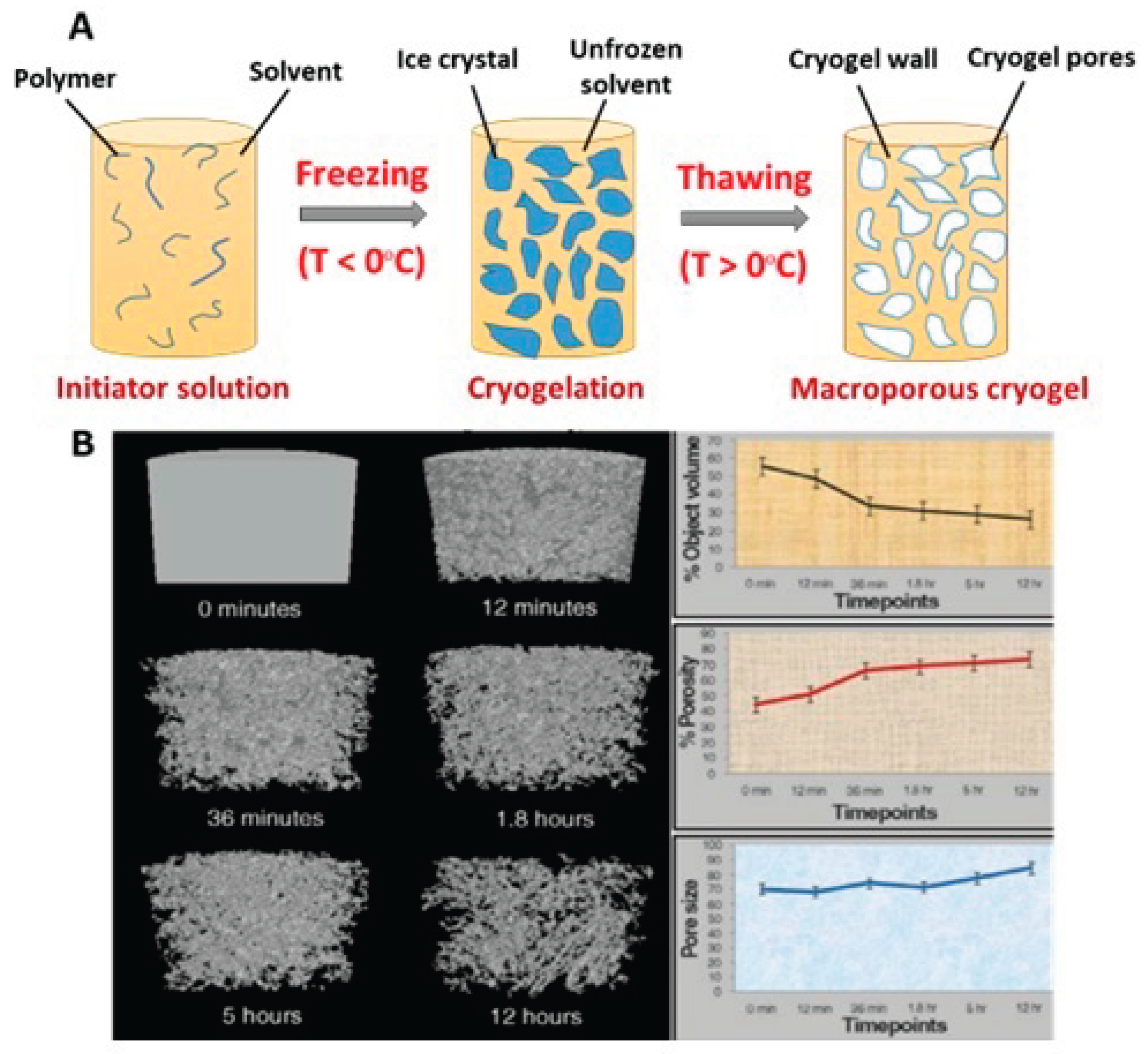

2. Phenomenon of Cryogel Synthesis

2.1. Freezing of Precursor Solutions and Phase Separation with Ice Formation

2.2. Incubation Under Frozen Condition, Cryo-Concentration and Polymerization

2.3 Thawing and Formation of Interconnected Pore Network

3. Crosslinking Mechanisms for Cryogels

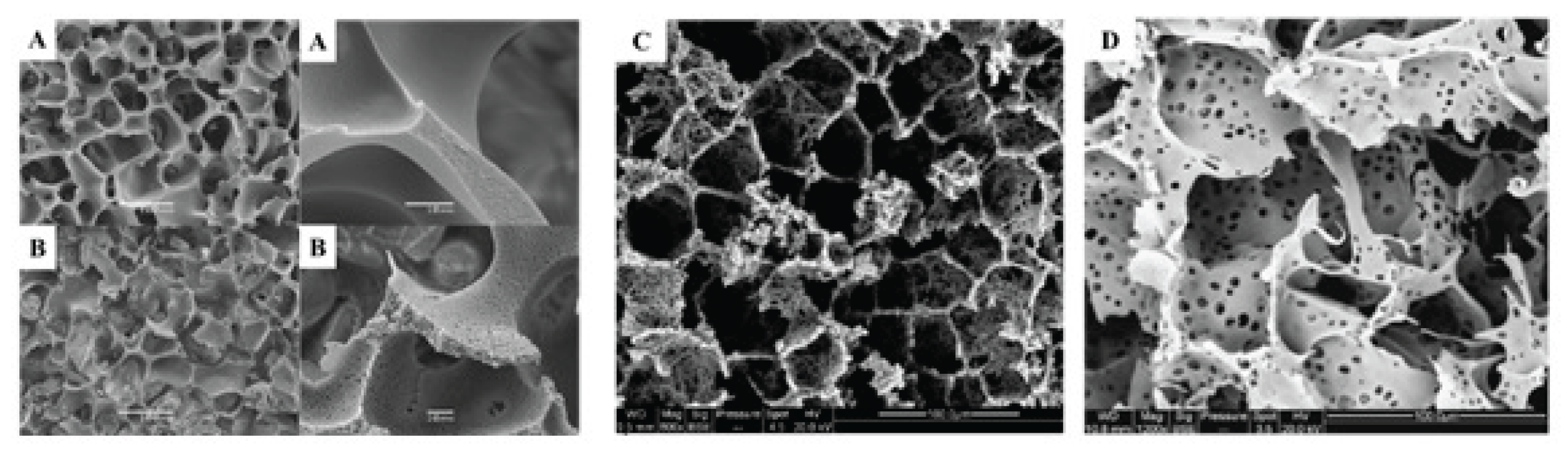

3.1. Covalently Cross-Linked Cryogels:

3.2. Physically Cross-Linked Cryogels:

3.3. Ionically Crosslinked-Cryogels

3.4. Mechanical Stability of Physical and Covalently Crosslinked Cryogels

4. Factors Affecting Cryotropic Gel Formation

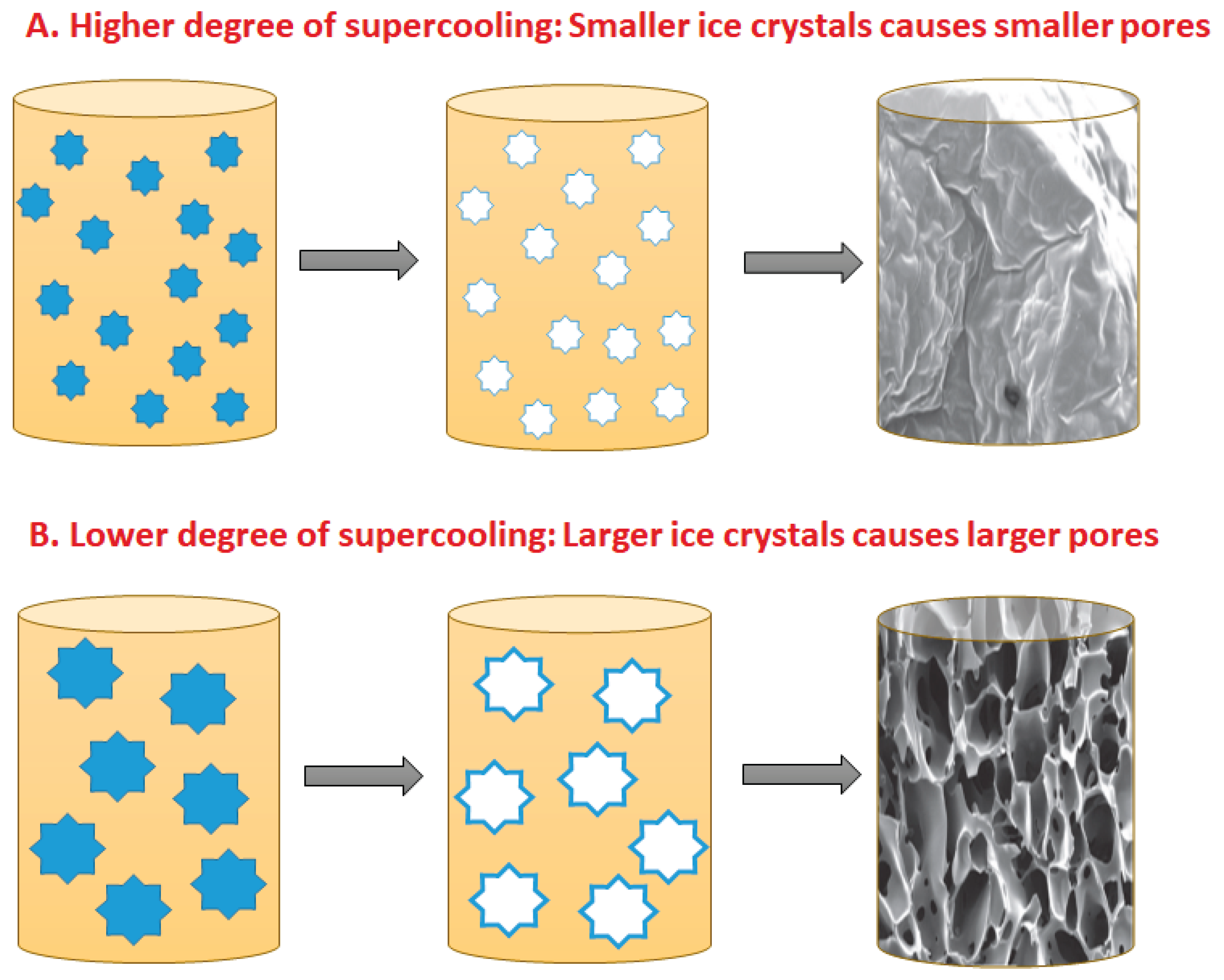

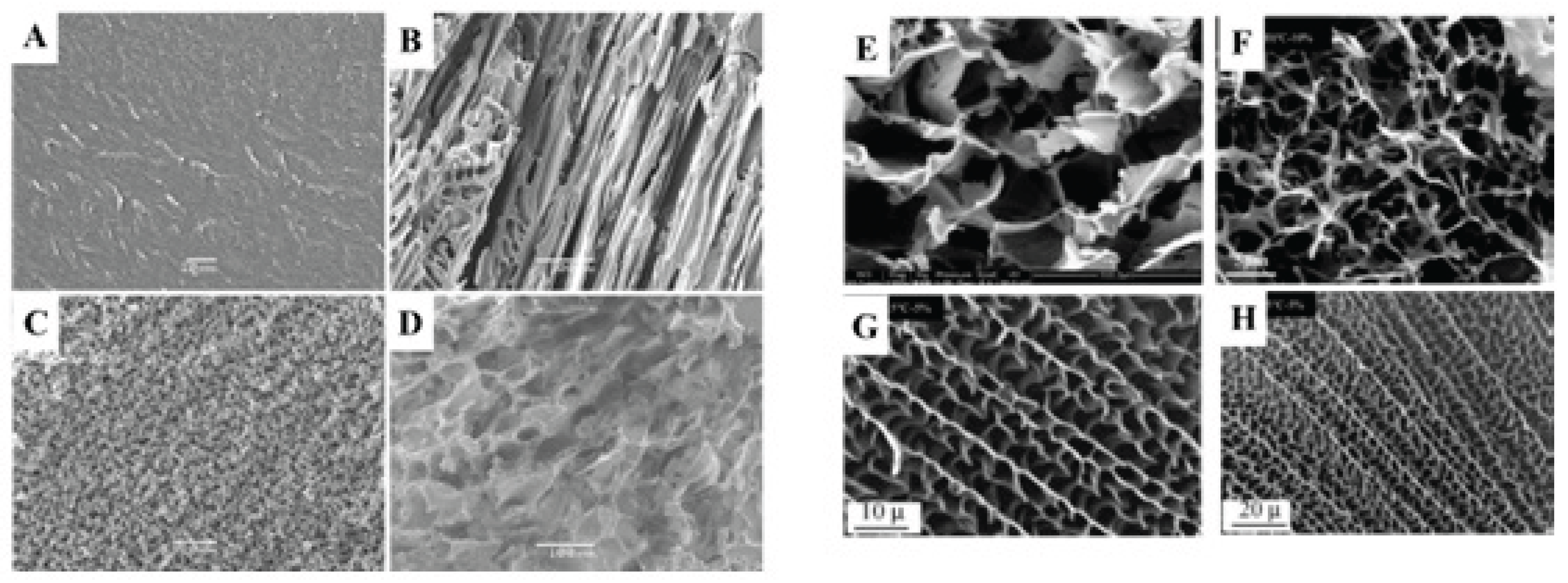

4.1. Ice Nucleation and Crystal Growth

4.2. Effect of Solvent

4.3. Effect of Temperature

4.4. Rate of Thawing

4.5. Effects of Added Solutes

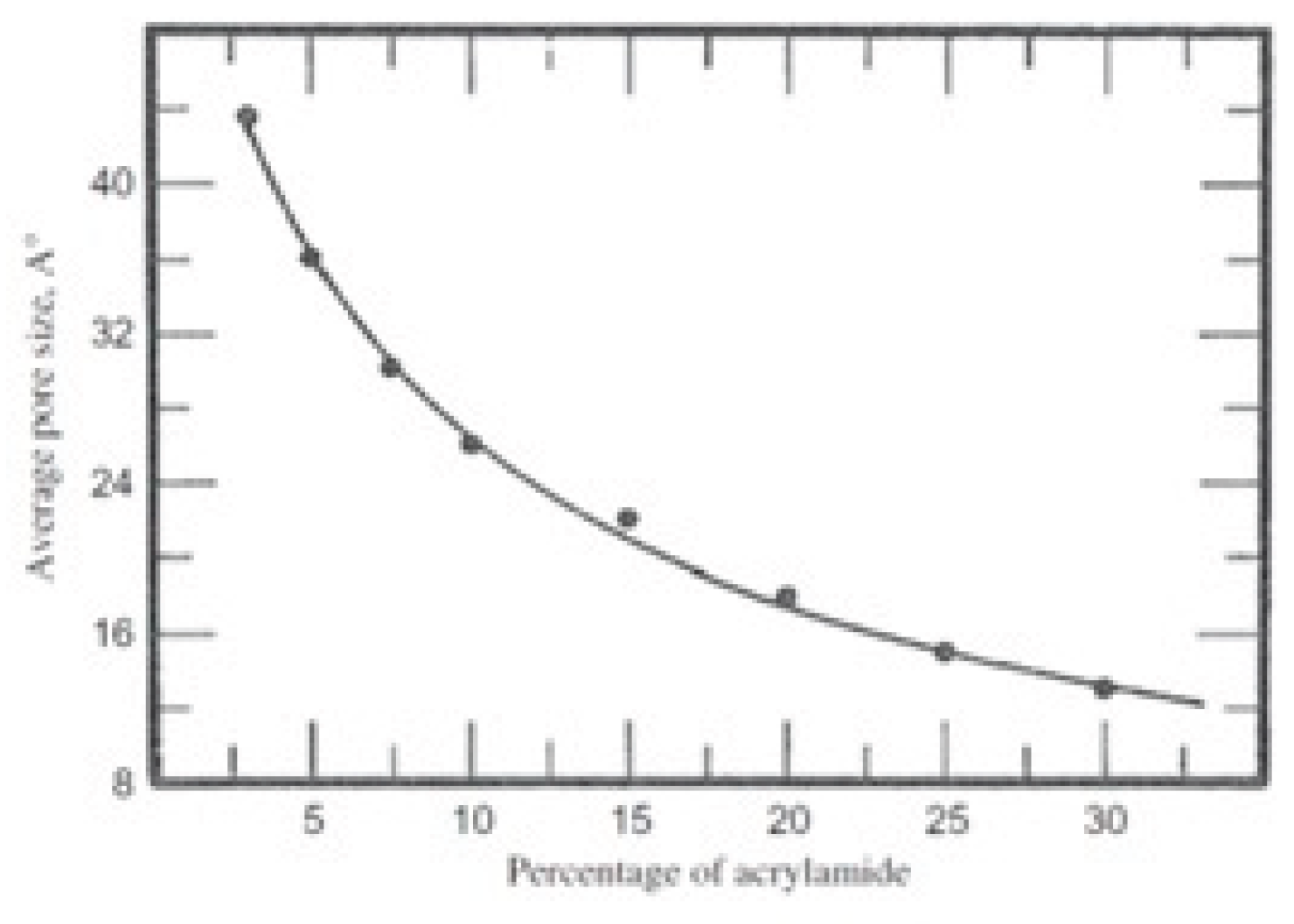

4.6. Precursor Composition

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

References

- Wegst, U. G.; Bai, H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A. P.; Ritchie, R. O., Bioinspired structural materials. Nat Mater 2015, 14 (1), 23-36. [CrossRef]

- Petkovich, N. D.; Stein, A., Controlling macro- and mesostructures with hierarchical porosity through combined hard and soft templating. Chemical Society reviews 2013, 42 (9), 3721-39. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gan, L.; Huang, J., Design, Manufacturing and Functions of Pore-Structured Materials: From Biomimetics to Artificial. Biomimetics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 8 (2). [CrossRef]

- Sai, H.; Tan, K. W.; Hur, K.; Asenath-Smith, E.; Hovden, R.; Jiang, Y.; Riccio, M.; Muller, D. A.; Elser, V.; Estroff, L. A.; Gruner, S. M.; Wiesner, U., Hierarchical porous polymer scaffolds from block copolymers. Science 2013, 341 (6145), 530-4. [CrossRef]

- Loh, Q. L.; Choong, C., Three-Dimensional Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: Role of Porosity and Pore Size. Tissue Eng Part B-Re 2013, 19 (6), 485-502. [CrossRef]

- Ma, P. X., Scaffolds for tissue fabrication. Mater Today 2004, 7 (5), 30-40. [CrossRef]

- Górnicki, T.; Lambrinow, J.; Golkar-Narenji, A.; Data, K.; Domagała, D.; Niebora, J.; Farzaneh, M.; Mozdziak, P.; Zabel, M.; Antosik, P., Biomimetic Scaffolds—A Novel Approach to Three Dimensional Cell Culture Techniques for Potential Implementation in Tissue Engineering. Nanomaterials 2024, 14 (6), 531. [CrossRef]

- Çimen, D.; Özbek, M. A.; Bereli, N.; Mattiasson, B.; Denizli, A., Injectable Functional Polymeric Cryogels for Biological Applications. Biomedical Materials & Devices 2024, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Andres, M.; Robertson, E.; Hall, A.; McBride-Gagyi, S.; Sell, S., Controlled pore anisotropy in chitosan-gelatin cryogels for use in bone tissue engineering. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 2024, 08853282231222324. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Yan, J.; Bao, X.; Gleadall, A.; Sun, T., Investigation of cell infiltration and colonization in 3D porous scaffolds via integrated experimental and computational strategies. Journal of Biotechnology 2024, 382, 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Garg, T.; Singh, O.; Arora, S.; Murthy, R. S. R., Scaffold: A Novel Carrier for Cell and Drug Delivery. Crit Rev Ther Drug 2012, 29 (1), 1-63. [CrossRef]

- Shih, T. Y.; Blacklow, S. O.; Li, A. W.; Freedman, B. R.; Bencherif, S.; Koshy, S. T.; Darnell, M. C.; Mooney, D. J., Injectable, Tough Alginate Cryogels as Cancer Vaccines. Adv Healthc Mater 2018, 7 (10). [CrossRef]

- Mi, H. Y.; Jing, X.; Turng, L. S., Fabrication of porous synthetic polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. J Cell Plast 2015, 51 (2), 165-196. [CrossRef]

- Pelin, G.; Sonmez, M.; Pelin, C.-E., The Use of Additive Manufacturing Techniques in the Development of Polymeric Molds: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16 (8), 1055. [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yang, B.; Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Q., Macroporous Hydrogels Prepared By Ice Templating: Developments And Challenges. Chinese Journal of Chemistry 2023, 41 (22), 3082-3096. [CrossRef]

- Hollister, S. J., Porous scaffold design for tissue engineering. Nat Mater 2005, 4 (7), 518-24. [CrossRef]

- Deville, S., Ice-templating, freeze casting: Beyond materials processing. J Mater Res 2013, 28 (17), 2202-2219. [CrossRef]

- Deville, S.; Maire, E.; Lasalle, A.; Bogner, A.; Gauthier, C.; Leloup, J.; Guizard, C., Influence of Particle Size on Ice Nucleation and Growth During the Ice-Templating Process. J Am Ceram Soc 2010, 93 (9), 2507-2510. [CrossRef]

- Deville, S.; Saiz, E.; Nalla, R. K.; Tomsia, A. P., Freezing as a path to build complex composites. Science 2006, 311 (5760), 515-8. [CrossRef]

- Deville, S.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A. P., Freeze casting of hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27 (32), 5480-9. [CrossRef]

- Joukhdar, H.; Seifert, A.; Jüngst, T.; Groll, J.; Lord, M. S.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J., Ice Templating Soft Matter: Fundamental Principles and Fabrication Approaches to Tailor Pore Structure and Morphology and Their Biomedical Applications. Advanced materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 2021, 33 (34), e2100091. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Mishra, R.; Reinwald, Y.; Bhat, S., Cryogels: Freezing unveiled by thawing. Mater Today 2010, 13 (11), 42-44. [CrossRef]

- Saylan, Y.; Denizli, A., Supermacroporous Composite Cryogels in Biomedical Applications. Gels 2019, 5 (2). [CrossRef]

- Shur, Y. L.; Jorgenson, M. T., Patterns of permafrost formation and degradation in relation to climate and ecosystems. Permafrost Periglac 2007, 18 (1), 7-19. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I., Polymeric cryogels as a new family of macroporous and supermacroporous materials for biotechnological purposes. Russian Chemical Bulletin 2008, 57 (5), 1015-1032. [CrossRef]

- Joukhdar, H.; Seifert, A.; Jüngst, T.; Groll, J.; Lord, M. S.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J., Ice Templating Soft Matter: Fundamental Principles and Fabrication Approaches to Tailor Pore Structure and Morphology and Their Biomedical Applications. Advanced Materials 2021, 33 (34), 2100091. [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom, H.; Mattiasson, B.; Galaev, I. Y., Building macroporous materials from microgels and microbes via one-step cryogelation. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2009, 25 (15), 8462-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lee, J. Y.; Ahmed, A.; Hussain, I.; Cooper, A. I., Freeze-align and heat-fuse: microwires and networks from nanoparticle suspensions. Angewandte Chemie 2008, 47 (24), 4573-6. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Galaev, I. Y.; Plieva, F. M.; Savina, I. N.; Jungvid, H.; Mattiasson, B., Polymeric cryogels as promising materials of biotechnological interest. Trends in Biotechnology 2003, 21 (10), 445-51. [CrossRef]

- Attwater, J.; Wochner, A.; Pinheiro, V. B.; Coulson, A.; Holliger, P., Ice as a protocellular medium for RNA replication. Nat Commun 2010, 1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. H.; Orgel, L. E., Efficient oligomerization of negatively-charged beta-amino acids at -20 degrees C. J Am Chem Soc 1997, 119 (20), 4791-4792. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I., Cryogels on the basis of natural and synthetic polymers: Preparation, properties and application. Uspekhi Khimii 2002, 71 (6), 559-585. [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom, H.; Rata, G.; Topgaard, D.; Mattiasson, B.; Galaev, I. Y., Mechanism of Cryopolymerization: Diffusion-Controlled Polymerization in a Nonfrozen Microphase. An NMR Study. Macromolecules 2009, 42 (14), 5208-5214. [CrossRef]

- Pincock, R. E., Reactions in Frozen Systems. Accounts Chem Res 1969, 2 (4), 97-&. [CrossRef]

- Bruice, T. C.; Butler, A. R., Ionic Reactions in Frozen Aqueous Systems. Federation proceedings 1965, 24, S45-9.

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Plieva, F. M.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B., The potential of polymeric cryogels in bioseparation. Bioseparation 2001, 10 (4-5), 163-88. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B. M. A.; Da Silva, S. L.; Da Silva, L. H. M.; Minim, V. P. R.; Da Silva, M. C. H.; Carvalho, L. M.; Minim, L. A., Cryogel Poly(acrylamide): Synthesis, Structure and Applications. Sep Purif Rev 2014, 43 (3), 241-262. [CrossRef]

- Kirsebom, H.; Topgaard, D.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B., Modulating the Porosity of Cryogels by Influencing the Nonfrozen Liquid Phase through the Addition of Inert Solutes. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2010, 26 (20), 16129-16133. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Vainerman, E. S.; Titova, E. F.; Belavtseva, E. M.; Rogozhin, S. V., Study of Cryostructurization of Polymer Systems .4. Cryostructurization of the System - Solvent Vinyl Monomer Divinyl Monomer Initiator of Polymerization. Colloid and Polymer Science 1984, 262 (10), 769-774. [CrossRef]

- Gusev, D. G.; Lozinsky, V. I.; Bakhmutov, V. I., Study of Cryostructurization of Polymer Systems .10. H-1-Nmr and H-2-Nmr Studies of the Formation of Cross-Linked Polyacrylamide Cryogels. European Polymer Journal 1993, 29 (1), 49-55.

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Domotenko, L. V.; Zubov, A. L.; Simenel, I. A., Study of cryostructuration of polymer systems .12. Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels: Influence of low-molecular electrolytes. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1996, 61 (11), 1991-1998. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Kathuria, N.; Kumar, A., Elastic and macroporous agarose-gelatin cryogels with isotropic and anisotropic porosity for tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2009, 90a (3), 680-694. [CrossRef]

- Kathuria, N.; Tripathi, A.; Kar, K. K.; Kumar, A., Synthesis and characterization of elastic and macroporous chitosan-gelatin cryogels for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 2009, 5 (1), 406-418. [CrossRef]

- Dainiak, M. B.; Galaev, I. Y.; Kumar, A.; Plieva, F. M.; Mattiasson, B., Chromatography of living cells using supermacroporous hydrogels, cryogels. Adv Biochem Eng Biot 2007, 106, 101-127. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T. W.; Hsu, S. H., Self-Healing Hydrogels and Cryogels from Biodegradable Polyurethane Nanoparticle Crosslinked Chitosan. Adv Sci (Weinh) 2020, 7 (3), 1901388. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-W.; Hsu, S.-h., Self-Healing Hydrogels and Cryogels from Biodegradable Polyurethane Nanoparticle Crosslinked Chitosan. Advanced Science 2020, 7 (3), 1901388. [CrossRef]

- Yetiskin, B.; Okay, O., High-strength silk fibroin scaffolds with anisotropic mechanical properties. Polymer 2017, 112, 61-70. [CrossRef]

- Yetiskin, B.; Okay, O., High-strength and self-recoverable silk fibroin cryogels with anisotropic swelling and mechanical properties. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 122, 1279-1289. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.-P.; Hsu, S.-h., A self-healing hydrogel and injectable cryogel of gelatin methacryloyl-polyurethane double network for 3D printing. Acta Biomaterialia 2023, 164, 124-138. [CrossRef]

- Bilici, C.; Altunbek, M.; Afghah, F.; Tatar, A. G.; Koc, B., Embedded 3D Printing of Cryogel-Based Scaffolds. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9 (8), 5028-5038. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Xiao, L.; Cheng, W.; Lu, Q. J. B., Macroporous silk nanofiber cryogels with tunable properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 23 (5), 2160-2169. [CrossRef]

- Petrov, P. D.; Tsvetanov, C. B., Cryogels via UV Irradiation. In Polymeric Cryogels: Macroporous Gels with Remarkable Properties, Okay, O., Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp 199-222. [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, S.; Abe, C.; Hainich, S.; Knolle, W.; Decker, U.; Prager, A.; Konieczny, R., Electron-beam derived polymeric cryogels. Soft Matter 2013, 9 (8), 2484-2492. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Chen, S.; Pan, J.; Weidong, H., Gamma radiation induced synthesis of double network hydrophilic cryogels at low pH loaded with AuNPs for fast and efficient degradation of Congo red. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 10, 100299. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Sakhno, N. G.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Bakeeva, I. V.; Zubov, V. P.; Kurochkin, I. N.; Kurochkin, I. I., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems: 31. Effect of additives of alkali metal chlorides on physicochemical properties and morphology of poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels. Colloid J+ 2011, 73 (2), 234-243. [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, I. A.; Grinberg, N. V.; Burova, T. V.; Grinberg, V. Y.; Lozinsky, V. I., Cryostructuring of polymer systems. Proteinaceous wide-pore cryogels generated by the action of denaturant/reductant mixtures on bovine serum albumin in moderately frozen aqueous media. Soft Matter 2015, 11 (24), 4921-4931. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H., Physically Cross-Linked Hyaluronan-Based Ultrasoft Cryogel Prepared by Freeze–Thaw Technique as a Barrier for Prevention of Postoperative Adhesions. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22 (12), 4967-4979. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, H., Freeze–Thaw-Induced Gelation of Hyaluronan: Physical Cryostructuration Correlated with Intermolecular Associations and Molecular Conformation. Macromolecules 2017, 50 (17), 6647-6658. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Brown, R.; Norton, I. T., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems. XIX. On the nature of intermolecular links in the cryogels of locust bean gum. Polymer International 2000, 49 (11), 1434-1443. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Brown, R.; Norton, I. T., Study of cryostructuration of polymer systems. XXI. Cryotropic gel formation of the water-maltodextrin systems. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2002, 83 (8), 1658-1667. [CrossRef]

- Soradech, S.; Williams, A. C.; Khutoryanskiy, V. V., Physically Cross-Linked Cryogels of Linear Polyethyleneimine: Influence of Cooling Temperature and Solvent Composition. Macromolecules 2022, 55 (21), 9537-9546. [CrossRef]

- Takei, T.; Danjo, S.; Sakoguchi, S.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshinaga, T.; Nishimata, H.; Yoshida, M., Autoclavable physically-crosslinked chitosan cryogel as a wound dressing. J Biosci Bioeng 2018, 125 (4), 490-495. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E. S.; Dinu, M. V.; Ghiorghita, C. A. Chitosan-Based Polyelectrolyte Complex Cryogels with Elasticity, Toughness and Delivery of Curcumin Engineered by Polyions Pair and Cryostructuration Steps Gels [Online], 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pita-López, M. L.; Fletes-Vargas, G.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R., Physically cross-linked chitosan-based hydrogels for tissue engineering applications: A state-of-the-art review. European Polymer Journal 2021, 145, 110176. [CrossRef]

- Berillo, D.; Mattiasson, B.; Kirsebom, H., Cryogelation of Chitosan Using Noble-Metal Ions: In Situ Formation of Nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15 (6), 2246-2255. [CrossRef]

- Takei, T.; Danjo, S.; Sakoguchi, S.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshinaga, T.; Nishimata, H.; Yoshida, M., Autoclavable physically-crosslinked chitosan cryogel as a wound dressing. Journal of bioscience and bioengineering 2018, 125 (4), 490-495. [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Kumar, A., Designing supermacroporous cryogels based on polyacrylonitrile and a polyacrylamide-chitosan semi-interpenetrating network. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2009, 20 (7-8), 877-902. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Kumar, A., Synthesis and characterization of a temperature-responsive biocompatible poly(N-vinylcaprolactam) cryogel: a step towards designing a novel cell scaffold. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed 2009, 20 (10), 1393-415. [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Damania, A.; Shakya, A. K.; Kumar, A.; Sarin, S. K.; Kumar, A., Fabrication of macroporous cryogels as potential hepatocyte carriers for bioartificial liver support. Colloid Surface B 2015, 136, 761-771. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Sangaj, N.; Varghese, S., Interconnected macroporous poly(ethylene glycol) cryogels as a cell scaffold for cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A 2010, 16 (10), 3033-41. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Bajpai, J.; Bajpai, A. K.; Mishra, A., Thermoresponsive cryogels of poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate-co-N-isopropyl acrylamide) (P(HEMA-co-NIPAM)): fabrication, characterization and water sorption study. Polymer Bulletin 2020, 77 (8), 4417-4443. [CrossRef]

- Tonta, M. M.; Sahin, Z. M.; Cihaner, A.; Yilmaz, F.; Gurek, A., Synthesis of Polyacrylamide-Based Redox Active Cryogel Using Click Chemistry and Investigation of Its Electrochemical Properties. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6 (45), 12644-12651. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E. S.; Dinu, M. V.; Ghiorghita, C. A.; Lazar, M. M.; Doroftei, F. Preparation and Characterization of Semi-IPN Cryogels Based on Polyacrylamide and Poly(N,N-dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate); Functionalization of Carrier with Monochlorotriazinyl-β-cyclodextrin and Release Kinetics of Curcumin Molecules [Online], 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sedlačík, T.; Nonoyama, T.; Guo, H.; Kiyama, R.; Nakajima, T.; Takeda, Y.; Kurokawa, T.; Gong, J. P., Preparation of Tough Double- and Triple-Network Supermacroporous Hydrogels through Repeated Cryogelation. Chemistry of Materials 2020, 32 (19), 8576-8586. [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, A., Macroporous interpenetrating cryogel network of poly(acrylonitrile) and gelatin for biomedical applications. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2009, 20 (1), 173-179. [CrossRef]

- Dispinar, T.; Van Camp, W.; De Cock, L. J.; De Geest, B. G.; Du Prez, F. E., Redox-Responsive Degradable PEG Cryogels as Potential Cell Scaffolds in Tissue Engineering. Macromolecular Bioscience 2012, 12 (3), 383-394. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Srivastava, A., Cell separation using cryogel-based affinity chromatography. Nature Protocols 2010, 5 (11), 1737-1747. [CrossRef]

- Davidson-Rozenfeld, G.; Chen, X.; Qin, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; Sohn, Y. S.; Li, Z.; Nechushtai, R.; Willner, I., Stiffness-Switchable, Biocatalytic pH-Responsive DNA-Functionalized Polyacrylamide Cryogels and their Mechanical Applications. Advanced Functional Materials 2024, 34 (4), 2306586. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E. S.; Cocarta, A. I., Smart Macroporous IPN Hydrogels Responsive to pH, Temperature, and Ionic Strength: Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Controlled Release of Drugs. Acs Appl Mater Inter 2016, 8 (19), 12018-12030. [CrossRef]

- Okten, N. S.; Tanc, B.; Orakdogen, N., Design and molecular dynamics of multifunctional sulfonated poly (dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate)/mica hybrid cryogels through freezing-induced gelation. Soft Matter 2019, 15 (35), 7043-7062. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. S.; Sangaj, N.; Varghese, S., Interconnected Macroporous Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Cryogels as a Cell Scaffold for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering Part A 2010, 16 (10), 3033-3041. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y. S.; Zhang, C.; Varghese, S., Poly(ethylene glycol) cryogels as potential cell scaffolds: effect of polymerization conditions on cryogel microstructure and properties. J Mater Chem 2010, 20 (2), 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Ferraraccio, L. S.; Russell, J.; Newland, B.; Bertoncello, P., Poly (ethylene glycol)(PEG)-Cryogels: a novel Platform towards Enzymatic Electrochemiluminescence (ECL)-based Sensor Applications. Electrochimica Acta 2024, 144007. [CrossRef]

- Uygun, M.; Senay, R. H.; Avcibasi, N.; Akgol, S., Poly(HEMA-co-NBMI) Monolithic Cryogel Columns for IgG Adsorption. Appl Biochem Biotech 2014, 172 (3), 1574-1584. [CrossRef]

- Bakhshpour, M.; Topcu, A. A.; Bereli, N.; Alkan, H.; Denizli, A., Poly (Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate) immunoaffinity cryogel column for the purification of human immunoglobulin M. Gels 2020, 6 (1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Jain, E.; Kumar, A., The physical characterization of supermacroporous poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) cryogel: Mechanical strength and swelling/de-swelling kinetics. Materials Science and Engineering A 2007, 464 (1-2), 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Salar Amoli, M.; Anand, R.; EzEldeen, M.; Geris, L.; Jacobs, R.; Bloemen, V., Development of 3D Printed pNIPAM-Chitosan Scaffolds for Dentoalveolar Tissue Engineering. Gels 2024, 10, 140. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Persson, P.; Baybak, O.; Plieva, F.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B.; Nilsson, B.; Axelsson, A., Characterization of a continuous supermacroporous monolithic matrix for chromatographic separation of large bioparticles. Biotechnology and Bioengineering 2004, 88 (2), 224-236. [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Wu, F.; Ullah, M.; Saeed, T.; Li, H.; Pan, J., Chitosan functionalization with vinyl monomers via ultraviolet illumination under cryogenic conditions for efficient palladium recovery from waste electronic materials. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 329, 125213. [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva, V.; Momekova, D.; Kostova, B.; Petrov, P., Stimuli sensitive super-macroporous cryogels based on photo-crosslinked 2-hydroxyethylcellulose and chitosan. Carbohyd Polym 2014, 99, 825-830. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Ghosal, K.; Kumar, M.; Mahmood, S.; Thomas, S., A detailed discussion on interpenetrating polymer network (IPN) based drug delivery system for the advancement of health care system. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 79, 104095. [CrossRef]

- Thönes, S.; Kutz, L. M.; Oehmichen, S.; Becher, J.; Heymann, K.; Saalbach, A.; Knolle, W.; Schnabelrauch, M.; Reichelt, S.; Anderegg, U., New E-beam-initiated hyaluronan acrylate cryogels support growth and matrix deposition by dermal fibroblasts. International journal of biological macromolecules 2017, 94, 611-620. [CrossRef]

- Madaghiele, M.; Salvatore, L.; Demitri, C.; Sannino, A., Fast synthesis of poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate cryogels via UV irradiation. Materials Letters 2018, 218, 305-308. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, G. L.; Trzebicka, B.; Kostova, B.; Petrov, P. D., Super-macroporous dextran cryogels via UV-induced crosslinking: synthesis and characterization. Polymer International 2017, 66 (9), 1306-1311. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, M.; Zhang, H., Aligned porous stimuli-responsive hydrogels via directional freezing and frozen UV initiated polymerization. Soft Matter 2013, 9 (9), 2723-2729. [CrossRef]

- Van Vlierberghe, S., Crosslinking strategies for porous gelatin scaffolds. Journal of Materials Science 2016, 51 (9), 4349-4357. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. M.; Shea, L. D., Cryotemplation for the rapid fabrication of porous, patternable photopolymerized hydrogels. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2014, 2 (28), 4521-4530. [CrossRef]

- Serex, L.; Braschler, T.; Filippova, A.; Rochat, A.; Béduer, A.; Bertsch, A.; Renaud, P., Pore Size Manipulation in 3D Printed Cryogels Enables Selective Cell Seeding. Advanced Materials Technologies 2018, 3 (4), 1700340. [CrossRef]

- Bilici, C. i. d.; Altunbek, M.; Afghah, F.; Tatar, A. G.; Koç, B., Embedded 3D printing of cryogel-based scaffolds. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering 2023, 9 (8), 5028-5038. [CrossRef]

- Bencherif, S. A.; Sands, R. W.; Bhatta, D.; Arany, P.; Verbeke, C. S.; Edwards, D. A.; Mooney, D. J. J. P. o. t. N. A. o. S., Injectable preformed scaffolds with shape-memory properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109 (48), 19590-19595. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Zo, S. M.; Kumar, A.; Han, S. S., Engineering three-dimensional macroporous hydroxyethyl methacrylate-alginate-gelatin cryogel for growth and proliferation of lung epithelial cells. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 2013, 24 (11), 1343-1359. [CrossRef]

- Berillo, D.; Volkova, N., Preparation and physicochemical characteristics of cryogel based on gelatin and oxidised dextran. Journal of materials science 2014, 49, 4855-4868. [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Pedrares, N.; López-Seijas, J.; Miranda-Balbuena, D.; Lamas, I.; Yáñez, J.; Rey-Rico, A., Gene-activated hyaluronic acid-based cryogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 362, 606-619. [CrossRef]

- Bayir, E., Comparative evaluation of alginate-gelatin hydrogel, cryogel, and aerogel beads as a tissue scaffold. Sakarya University Journal of Science 2023, 27 (2), 335-348. [CrossRef]

- Mancino, R.; Caccavo, D.; Barba, A. A.; Lamberti, G.; Biasin, A.; Cortesi, A.; Grassi, G.; Grassi, M.; Abrami, M., Agarose Cryogels: Production Process Modeling and Structural Characterization. Gels 2023, 9 (9), 765. [CrossRef]

- Şeker, Ş.; Aral, D.; Elçin, A. E.; Murat, E. Y., Biomimetic mineralization of platelet lysate/oxidized dextran cryogel as a macroporous 3D composite scaffold for bone repair. Biomedical Materials 2024, 19 (2), 025006. [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, S.; Becher, J.; Weisser, J.; Prager, A.; Decker, U.; Moller, S.; Berg, A.; Schnabelrauch, M., Biocompatible polysaccharide-based cryogels. Mat Sci Eng C-Mater 2014, 35, 164-170. [CrossRef]

- Kumakura, M., Preparation method of porous polymer materials by radiation technique and its application. Polym Advan Technol 2001, 12 (7), 415-421. [CrossRef]

- Reichelt, S.; Prager, A.; Abe, C.; Knolle, W., Tailoring the structural properties of macroporous electron-beam polymerized cryogels by pore forming agents and the monomer selection. Radiat Phys Chem 2014, 94, 40-44. [CrossRef]

- Tonta, M. M.; Sahin, Z. M.; Cihaner, A.; Yilmaz, F.; Gurek, A., Synthesis of Polyacrylamide-Based Redox Active Cryogel Using Click Chemistry and Investigation of Its Electrochemical Properties. ChemistrySelect 2021, 6 (45), 12644-12651. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H. C.; Finn, M. G.; Sharpless, K. B., Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2001, 40 (11), 2004-2021. [CrossRef]

- Crowell, A. D.; FitzSimons, T. M.; Anslyn, E. V.; Schultz, K. M.; Rosales, A. M., Shear Thickening Behavior in Injectable Tetra-PEG Hydrogels Cross-Linked via Dynamic Thia-Michael Addition Bonds. Macromolecules 2023, 56 (19), 7795-7807. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. P., Chemical and Proteolytic Modification of Antibodies. Making and Using Antibodies 2006, 195-260.

- Lin, T. W.; Hsu, S. h., Self-Healing Hydrogels and Cryogels from Biodegradable Polyurethane Nanoparticle Crosslinked Chitosan. Advanced Science 2020, 7 (3), 1901388. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-T.; Ma, R.; Wang, P.; Xin, J.; Zhang, J.; Wolcott, M. P.; Zhang, X., Deep eutectic solvent assisted facile synthesis of lignin-based cryogel. Macromolecules 2018, 52 (1), 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Sezen, S.; Thakur, V. K.; Ozmen, M. M. J. G., Highly effective covalently crosslinked composite alginate cryogels for cationic dye removal. Gels 2021, 7 (4), 178. [CrossRef]

- Chambre, L.; Maouati, H.; Oz, Y.; Sanyal, R.; Sanyal, A., Thiol-Reactive Clickable Cryogels: Importance of Macroporosity and Linkers on Biomolecular Immobilization. Bioconjugate Chemistry 2020, 31 (9), 2116-2124. [CrossRef]

- Ciolacu, D.; Rudaz, C.; Vasilescu, M.; Budtova, T., Physically and chemically cross-linked cellulose cryogels: Structure, properties and application for controlled release. Carbohydrate polymers 2016, 151, 392-400. [CrossRef]

- Fukumori, T.; Nakaoki, T., Significant improvement of mechanical properties for polyvinyl alcohol film prepared from freeze/thaw cycled gel. Open Journal of Organic Polymer Materials 2013, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.; Onggowarsito, C.; Feng, A.; Zhang, S.; Fu, Q.; Nghiem, L. D., A cryogel solar vapor generator with rapid water replenishment and high intermediate water content for seawater desalination. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2023, 11 (2), 858-867. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Kumar, A., Multi-featured macroporous agarose–alginate cryogel: Synthesis and characterization for bioengineering applications. Macromolecular bioscience 2011, 11 (1), 22-35. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, L. P.; Cerqueira, M. T.; Sousa, R. A.; Reis, R. L.; Correlo, V. M.; Marques, A. P., Engineering cell-adhesive gellan gum spongy-like hydrogels for regenerative medicine purposes. Acta biomaterialia 2014, 10 (11), 4787-4797. [CrossRef]

- Elsherbiny, D. A.; Abdelgawad, A. M.; El-Naggar, M. E.; El-Sherbiny, R. A.; El-Rafie, M. H.; El-Sayed, I. E.-T., Synthesis, antimicrobial activity, and sustainable release of novel α-aminophosphonate derivatives loaded carrageenan cryogel. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 163, 96-107. [CrossRef]

- Meena, L. K.; Raval, P.; Kedaria, D.; Vasita, R., Study of locust bean gum reinforced cyst-chitosan and oxidized dextran based semi-IPN cryogel dressing for hemostatic application. Bioactive Materials 2018, 3 (3), 370-384. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Wu, J., Physically crosslinked hydrogels from polysaccharides prepared by freeze–thaw technique. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2013, 73 (7), 923-928. [CrossRef]

- Kolosova, O. Y.; Karelina, P. A.; Vasil'ev, V. G.; Grinberg, V. Y.; Kurochkin, I. I.; Kurochkin, I. N.; Lozinsky, V. I., Cryostructuring of polymeric systems. 58. Influence of the H2N-(CH2)n-COOH–type amino acid additives on formation, properties, microstructure and drug release behaviour of poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels. Reactive and Functional Polymers 2021, 167, 105010. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, A.; Miyoshi, T., A BIOCOMPATIBLE GEL OF HYALURONAN. In Hyaluronan, Kennedy, J. F.; Phillips, G. O.; Williams, P. A., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2002; pp 285-292.

- Luan, T.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y., A study on the nature of intermolecular links in the cryotropic weak gels of hyaluronan. Carbohyd Polym 2012, 87 (3), 2076-2085. [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, R.; Dutta, A.; Ray, P. G.; Seesala, V. S.; Ojha, A. K.; Dogra, N.; Roy, S.; Banerjee, M.; Dhara, S., High fibroin-loaded silk-PCL electrospun fiber with core–shell morphology promotes epithelialization with accelerated wound healing. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10 (46), 9622-9638. [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, P. U.; Jain, E.; Hixon, K. R.; Eberlin, C. T.; Sell, S. A., Sonication induced silk fibroin cryogels for tissue engineering applications. Materials Research Express 2016, 3 (5), 055401. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hao, B.; Ge, P.; Chen, S., Highly stretchable, self-healing, and 3D printing prefabricatable hydrophobic association hydrogels with the assistance of electrostatic interaction. Polymer Chemistry 2020, 11 (29), 4741-4748. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Cui, X.; Liu, X.; Qu, X.; Sun, J., Highly tough, stretchable, self-healing, and recyclable hydrogels reinforced by in situ-formed polyelectrolyte complex nanoparticles. Macromolecules 2019, 52 (8), 3141-3149. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, E. S.; Dinu, M. V.; Ghiorghita, C. A., Chitosan-Based Polyelectrolyte Complex Cryogels with Elasticity, Toughness and Delivery of Curcumin Engineered by Polyions Pair and Cryostructuration Steps. Gels 2022, 8 (4). [CrossRef]

- Pacelli, S.; Di Muzio, L.; Paolicelli, P.; Fortunati, V.; Petralito, S.; Trilli, J.; Casadei, M. A. J. I. J. o. B. M., Dextran-polyethylene glycol cryogels as spongy scaffolds for drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 166, 1292-1300. [CrossRef]

- Plieva, F.; Xiao, H. T.; Galaev, I. Y.; Bergenstahl, B.; Mattiasson, B., Macroporous elastic polyacrylamide gels prepared at subzero temperatures: control of porous structure. J Mater Chem 2006, 16 (41), 4065-4073. [CrossRef]

- Plieva, F. M.; Andersson, J.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B., Characterization of polyacrylamide based monolithic columns. J Sep Sci 2004, 27 (10-11), 828-836. [CrossRef]

- Priya, S. G.; Gupta, A.; Jain, E.; Sarkar, J.; Damania, A.; Jagdale, P. R.; Chaudhari, B. P.; Gupta, K. C.; Kumar, A., Bilayer Cryogel Wound Dressing and Skin Regeneration Grafts for the Treatment of Acute Skin Wounds. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8 (24), 15145-59. [CrossRef]

- Mishra Tiwari, R.; Channey, H. S.; Jain, E., Interpenetrating Polymer Network of Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Chitosan as Cryogels for Tissue Engineering Applications. Polym Advan Technol 2025, 36 (1), e70055. [CrossRef]

- Plieva, F. M.; Ekström, P.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B., Monolithic cryogels with open porous structure and unique double-continuous macroporous networks. Soft Matter 2008, 4 (12), 2418-2428. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jia, Z.; Wang, Q.; Tang, P.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Fang, J.; Zhao, C.; Ren, F.; Ge, X.; Lu, X., A resilient and flexible chitosan/silk cryogel incorporated Ag/Sr co-doped nanoscale hydroxyapatite for osteoinductivity and antibacterial properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2018, 6 (45), 7427-7438. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, Z.; Seitz, M. P.; Jain, E., Macroporous PEG-Alginate Hybrid Double-Network Cryogels with Tunable Degradation Rates Prepared via Radical-Free Cross-Linking for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2024, 7 (9), 5925-5938. [CrossRef]

- Memic, A.; Colombani, T.; Eggermont, L. J.; Rezaeeyazdi, M.; Steingold, J.; Rogers, Z. J.; Navare, K. J.; Mohammed, H. S.; Bencherif, S. A., Latest Advances in Cryogel Technology for Biomedical Applications. Advanced Therapeutics 2019, 2 (4), 1800114. [CrossRef]

- Van Rie, J.; Declercq, H.; Van Hoorick, J.; Dierick, M.; Van Hoorebeke, L.; Cornelissen, R.; Thienpont, H.; Dubruel, P.; Van Vlierberghe, S., Cryogel-PCL combination scaffolds for bone tissue repair. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Medicine 2015, 26, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Varghese, S., Poly(ethylene glycol) cryogels as potential cell scaffolds: effect of polymerization conditions on cryogel microstructure and properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2010, 20 (2), 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, H.; Xu, C.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Fu, A.; Li, H.; Lee, J. Y.; Zhang, S.; Ni, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Ge, S. S.; Jin, M. L.; Wang, L.; Xia, Y., Skin-like cryogel electronics from suppressed-freezing tuned polymer amorphization. Nature Communications 2023, 14 (1), 5010. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G. J. J. o. A. P. S., Study of cryostructuration of polymer systems. XVII. Poly (vinyl alcohol) cryogels: Dynamics of the cryotropic gel formation. 2000, 77 (9), 2017-2023. [CrossRef]

- Tuncaboylu, D. C.; Okay, O., Hierarchically macroporous cryogels of polyisobutylene and silica nanoparticles. Langmuir : the ACS journal of surfaces and colloids 2010, 26 (10), 7574-81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Z.; Wang, F. J.; Chu, C. C., Thermoresponsive hydrogel with rapid response dynamics. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2003, 14 (5), 451-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Z.; Chu, C. C., Thermosensitive PNIPAAm cryogel with superfast and stable oscillatory properties. Chemical communications 2003, (12), 1446-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Z.; Chu, C. C., Synthesis of temperature sensitive PNIPAAm cryogels in organic solvent with improved properties. J Mater Chem 2003, 13 (10), 2457-2464. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Kathuria, N.; Kumar, A., Elastic and macroporous agarose–gelatin cryogels with isotropic and anisotropic porosity for tissue engineering. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 2009, 90 (3), 680-694. [CrossRef]

- Ak, F.; Oztoprak, Z.; Karakutuk, I.; Okay, O., Macroporous Silk Fibroin Cryogels. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14 (3), 719-727. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Shaskol'skii, B. L.; Babushkina, T. A.; Kurochkin, I. N.; Kurochkin, I. I., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems: 27. Physicochemical properties of poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels and specific features of their macroporous morphology. Colloid J+ 2007, 69 (6), 747-764. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G., Study of cryostructuration of polymer systems. XVII. Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels: Dynamics of the cryotropic gel formation. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2000, 77 (9), 2017-2023. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Ivanov, R. V.; Kalinina, E. V.; Timofeeva, G. I.; Khokhlov, A. R., Redox-initiated radical polymerisation of acrylamide in moderately frozen water solutions. Macromolecular Rapid Communications 2001, 22 (17), 1441-1446. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Vainerman, E. S.; Korotaeva, G. F.; Rogozhin, S. V., Study of Cryostructurization of Polymer Systems .3. Cryostructurization in Organic Media. Colloid and Polymer Science 1984, 262 (8), 617-622. [CrossRef]

- Gun'ko, V. M.; Savina, I. N.; Mikhalovsky, S. V., Cryogels: Morphological, structural and adsorption characterisation. Advances in colloid and interface science 2013, 187, 1-46. [CrossRef]

- Ozmen, M. M.; Dinu, M. V.; Dragan, E. S.; Okay, O., Preparation of Macroporous Acrylamide-Based Hydrogels: Cryogelation Under Isothermal Conditions. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part A: Pure and Applied Chemistry 2007, 44 (11), 1195-1202. [CrossRef]

- Okay, O.; Lozinsky, V. I., Synthesis and Structure–Property Relationships of Cryogels. In Polymeric Cryogels: Macroporous Gels with Remarkable Properties, Okay, O., Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp 103-157. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Dai, B., Control of ice crystal growth and its effect on porous structure of chitosan cryogels. Chemical Engineering Science 2019, 201, 50-57. [CrossRef]

- Ni, X.; Ke, F.; Xiao, M.; Wu, K.; Kuang, Y.; Corke, H.; Jiang, F., The control of ice crystal growth and effect on porous structure of konjac glucomannan-based aerogels. Int J Biol Macromol 2016, 92, 1130-1135. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, R. V.; Lozinsky, V. I.; Noh, S. K.; Han, S. S.; Lyoo, W. S., Preparation and characterization of polyacrylamide cryogels produced from a high-molecular-weight precursor. I. influence of the reaction temperature and concentration of the crosslinking agent. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2007, 106 (3), 1470-1475. [CrossRef]

- Muslumova, S.; Yetiskin, B.; Okay, O. Highly Stretchable and Rapid Self-Recoverable Cryogels Based on Butyl Rubber as Reusable Sorbent Gels [Online], 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Hatakeyama, T.; Hatakeyama, H., Formation of locust bean gum hydrogel by freezing-thawing. Polymer International 1998, 45 (1), 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rodriguez-Caballero, A.; Plieva, F. M.; Galaev, I. Y.; Nandakumar, K. S.; Kamihira, M.; Holmdahl, R.; Orfao, A.; Mattiasson, B., Affinity binding of cells to cryogel adsorbents with immobilized specific ligands: effect of ligand coupling and matrix architecture. Journal of Molecular Recognition 2005, 18 (1), 84-93. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Bloch, K. O.; Vardi, P.; Grinberg, N. V.; Burova, T. V.; Grinberg, V. Y., Cryostructuring of polymer systems. XXIX. Preparation and characterization of supermacroporous (spongy) agarose-based cryogels used as three-dimensional scaffolds for culturing insulin-producing cell aggregates. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2008, 108 (5), 3046-3062. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Zubov, A. L.; Savina, I. N.; Plieva, F. M., Study of cryostructuration of polymer systems. XIV. Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels: Apparent yield of the freeze-thaw-induced gelation of concentrated aqueous solutions of the polymer. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2000, 77 (8), 1822-1831. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Zubov, A. L.; Kulakova, V. K.; Titova, E. F.; Rogozhin, S. V., Study of Cryostructurization of Polymer Systems .9. Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) Cryogels Filled with Particles of Cross-Linked Dextran Gel. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 1992, 44 (8), 1423-1435.

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Zubov, A. L.; Makhlis, T. A., Entrapment of Zymomonas mobilis cells into PVA-cryogel carrier in the presence of polyol cryoprotectants. Immobilized Cells: Basics and Applications 1996, 11, 112-117.845. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Savvichev, A. S.; Tumansky, B. L.; Nikitin, D. I., Some microorganisms during their entrapment in PAAG act as ''biological accelerators'' in how they affect the gel-formation rate. Immobilized Cells: Basics and Applications 1996, 11, 118-125. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Zubov, A. L.; Titova, E. F., Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels employed as matrices for cell immobilization .2. Entrapped cells resemble porous fillers in their effects on the properties of PVA-cryogel carrier. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 1997, 20 (3), 182-190. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Kurochkin, I. N.; Kurochkin, I. I., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems: 25. The influence of Surfactants on the properties and structure of gas-filled (Foamed) poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels. Colloid J+ 2005, 67 (5), 589-601. [CrossRef]

- Lozinskii, V. I.; Savina, I. N., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems: 22. Composite poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels filled with dispersed particles of various degrees of hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity. Colloid J+ 2002, 64 (3), 336-343. [CrossRef]

- Savina, I. N.; Mattiasson, B.; Galaev, I. Y., Graft polymerization of acrylic acid onto macroporous polyacrylamide gel (cryogel) initiated by potassium diperiodatocuprate. Polymer 2005, 46 (23), 9596-9603. [CrossRef]

- Savina, I. N.; Lozinskii, V. I., Study of cryostructuring of polymer systems: 23. Composite poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels filled with dispersed particles containing ionogenic groups. Colloid J+ 2004, 66 (3), 343-349. [CrossRef]

- Savina, I. N.; Hanora, A.; Plieva, F. M.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B.; Lozinsky, V. I., Cryostructuration of polymer systems. XXIV. Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels filled with particles of a strong anion exchanger: Properties of the composite materials and potential applications. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2005, 95 (3), 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Savina, I. N.; Hanora, A.; Plieva, F. M.; Galaev, I. Y.; Mattiasson, B.; Lozinsky, V. I., Cryostructuration of polymer systems. XXIV. Poly (vinyl alcohol) cryogels filled with particles of a strong anion exchanger: Properties of the composite materials and potential applications. Journal of applied polymer science 2005, 95 (3), 529-538. [CrossRef]

- Kolosova, O. Y.; Ryzhova, A. S.; Chernyshev, V. P.; Lozinsky, V. I., Study of Cryostructuring of Polymer System. 65. Features of Changes in the Physicochemical Properties of Poly(vinyl alcohol) Cryogels Caused by the Action of Aqueous Solutions of Amino Acids of General Formula H2N–(CH2)n–COOH. Colloid Journal 2023, 85 (6), 930-942. [CrossRef]

- Jain, E.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, A., Macroporous interpenetrating cryogel network of poly(acrylonitrile) and gelatin for biomedical applications. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2009, 20 Suppl 1, S173-9. [CrossRef]

- Lozinsky, V. I.; Bakeeva, I. V.; Presnyak, E. P.; Damshkaln, L. G.; Zubov, V. P., Cryostructuring of polymer systems. XXVI. Heterophase organic-inorganic cryogels prepared via freezing-thawing of aqueous solutions of poly(vinyl alcohol) with added tetramethoxysilane. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2007, 105 (5), 2689-2702. [CrossRef]

- Plieva, F.; Huiting, X.; Galaev, I. Y.; Bergenståhl, B.; Mattiasson, B., Macroporous elastic polyacrylamide gels prepared at subzero temperatures: control of porous structure. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2006, 16 (41), 4065-4073. [CrossRef]

- Podorozhko, E. A.; Buzin, M. I.; Golubev, E. K.; Shcherbina, M. A.; Lozinsky, V. I., A Study of Cryostructuring of Polymer Systems. 59. Effect of Cryogenic Treatment of Preliminarily Deformed Poly (vinyl alcohol) Cryogels on Their Physicochemical Properties. Colloid Journal 2021, 83, 634-641. [CrossRef]

- Konstantinova, N. R.; Lozinsky, V. I., Cryotropic gelation of ovalbumin solutions. Food Hydrocolloids 1997, 11 (2), 113-123. [CrossRef]

- Nadgorny, M.; Collins, J.; Xiao, Z.; Scales, P. J.; Connal, L. A., 3D-printing of dynamic self-healing cryogels with tuneable properties. Polymer Chemistry 2018, 9 (13), 1684-1692. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Jain, E.; Kumar, A., The physical characterization of supermacroporous poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) cryogel: mechanical strength and swelling/de-swelling kinetics. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2007, 464 (1-2), 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-Z.; Chu, C.-C., Synthesis of temperature sensitive PNIPAAm cryogels in organic solvent with improved properties. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2003, 13 (10), 2457-2464. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, B. M. A.; Da Silva, S. L.; Da Silva, L. H. M.; Minim, V. P. R.; Da Silva, M. C. H.; Carvalho, L. M.; Minim, L. A., Cryogel poly (acrylamide): synthesis, structure and applications. Separation & Purification Reviews 2014, 43 (3), 241-262. [CrossRef]

| Type of Crosslinking | Polymerization Mechanism | Chemical Reaction or Initiating Agent | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Chemical cross-linking | Free radical polymerization | Chemical initiators using redox pair | Highly efficient reaction yield in frozen conditions leading to high mechanical strength and better control over the polymerization reaction. | Residual initiators may cause toxicity. Uncontrolled reaction with side products |

| Free radical polymerization | Gamma irradiation using low dose or high energy electron beam | Additional chemical initiators or crosslinkers traces of which may sometimes be toxic. | Limited penetration into the sample leading gradient of radiation dose and inhomogeneous reaction conditions. | |

| Free radical polymerization | U.V. cross-linking using photo initiators like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), AIBN or Irgacure | Cryogels can be templated using both porogen that is ice and light to create complex architecture | Limited penetration into the sample leading gradient of radiation dose and inhomogeneous reaction conditions. | |

| Addition reaction | Click reactions such as Michael addition reaction. | Highly efficient reaction, biocompatible reaction conditions, no side products | Low reaction yield under frozen conditions. | |

| Physical cross-linking | Physical interactions | Hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions. Polymers rich in hydroxyl, carboxyl, or amine groups are usually amenable to such reactions. | High biocompatibility & biodegradability. Can be used as stimuli-response cryogels. | Cryogels usually have poor mechanical properties. Usually applicable to natural polymers. |

| Ionic cross-linking | Ionic interactions | Few examples such as alginate, chitosan, poly(ethylene imine) | High biocompatibility, biodegradability & mechanical strength. | Cryogels usually have poor mechanical properties. Usually applicable to natural polymers |

| Characteristic | Physically Crosslinked Cryogels | Covalently Crosslinked Cryogels |

| Crosslinking Mechanism | Non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions) | Chemical bonds between polymer chains |

| Preparation Methods | Freeze-thawing cycles, ion-mediated gelation | Chemical crosslinking agents, photopolymerization |

| Stability | Generally less stable; more susceptible to dissolution or degradation | Enhanced stability; resistant to dissolution |

| Mechanical Strength | Typically, lower | Generally higher |

| Reversibility | Often reversible (can be melted and reformed) | Typically irreversible |

| Stimuli-Responsiveness | More likely to respond to environmental changes (e.g., pH, temperature) | Less responsive to environmental stimuli |

| Biodegradability | Often more biodegradable | Potentially less biodegradable, depending on crosslinking agents |

| Porosity | Can exhibit high porosity, but may be prone to structural collapse | High porosity with improved structural integrity |

| Biocompatibility | Generally good, due to absence of potentially toxic crosslinking agents | May be affected by residual crosslinking agents; requires thorough purification |

| Efficiency of Preparation | Often simpler and faster but less reproducible. | May require longer preparation times and additional purification steps, but may have more reproducible results. |

| Examples | Poly(vinyl alcohol) cryogels, alginate cryogels | Poly(acrylamide) cryogels, Poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) cryogels |

| Applications | Soft tissue engineering, drug delivery, wound dressing | Tissue engineering scaffolds, bioseparation, water treatment, cell culture substrates |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).