Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

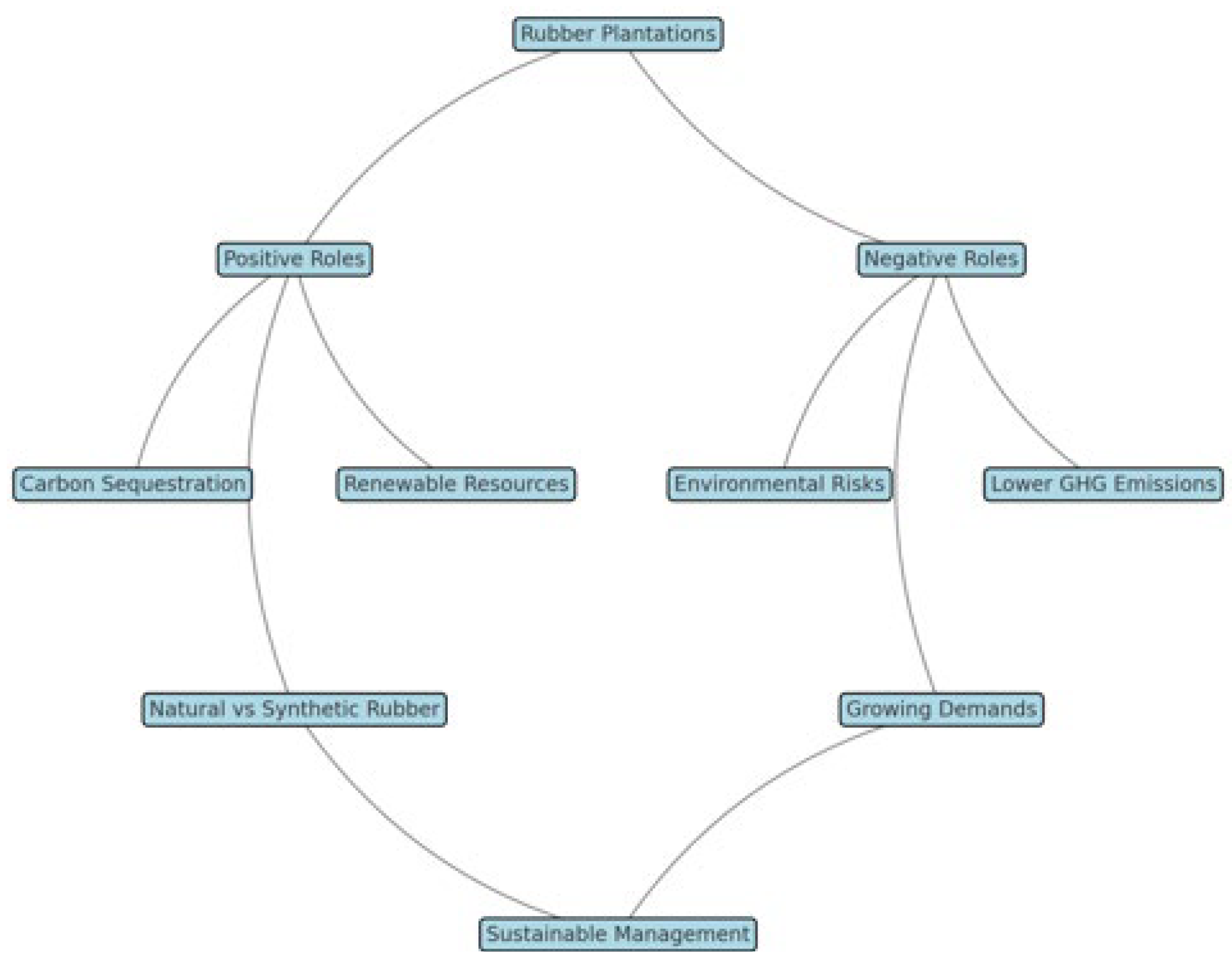

Tropical forest ecosystems play a significant role in carbon storage and climate regulation. However, these ecosystems are threatened by deforestation through slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and mining. Consequently, there is a pressing need to assess the carbon storage potential of tropical perennial plantations, particularly rubber plantations, as a sustainable alternative to deforestation and tropical forest degradation. This study utilizes a systematic review of the extant literature to assess the carbon sequestration potential of rubber plantations and to explore their viability as a complementary alternative to tropical forests in the context of climate change mitigation. The carbon stocks present in rubber plantations have been documented to range from 30 to over 100 tons of carbon per hectare in total dry weight. In comparison, dense tropical forests have been shown to store up to over 300 tons of carbon per hectare, placing rubber plantations in a competitive range, particularly when managed effectively. The potential for carbon sequestration varies considerably based on factors such as plantation age, tree density, environmental conditions, and land management practices, including crop rotation, tapping frequency, plantation maintenance, and biomass management. Optimizing plantation density and regulating water inputs to avoid excessive irrigation are among the management practices that have been shown to enhance carbon sequestration potential, maximize biomass storage, and preserve optimal physiological conditions for rubber trees. Notwithstanding their substantial carbon sequestration potential, rubber plantations are unable to fully compensate for the ecological functions and storage capacity of tropical forests. This limitation stems from their simplified structure and the reduction in biodiversity that is characteristic of monoculture. The findings of this study have the potential to inform the implementation of public policies that promote the adoption of rubber plantations in high-risk deforestation areas. These policies could be developed in conjunction with the development of sustainable management techniques, such as agroforestry, with the aim of maximizing carbon storage and biodiversity preservation. In this context, rubber plantations emerge as a complementary alternative to tropical forest conservation initiatives, offering an economically viable option while contributing significantly to carbon sequestration.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

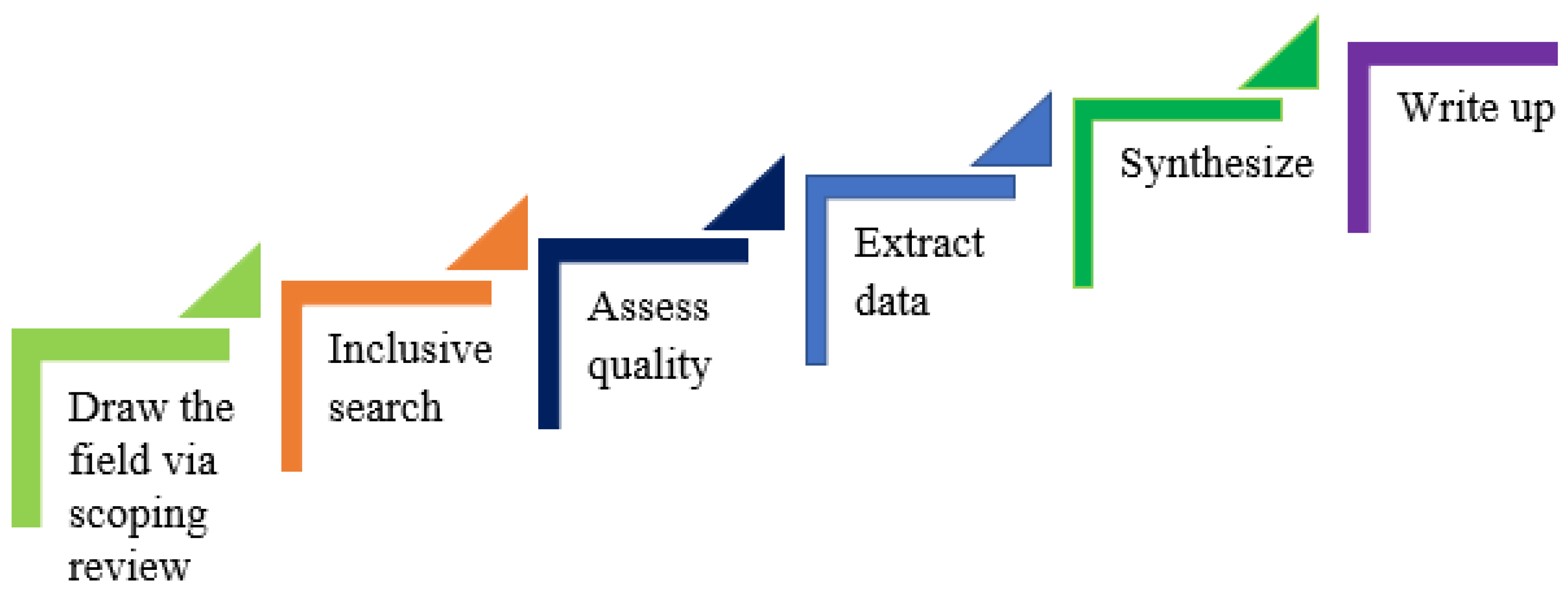

2. Methodology of the Literature Review

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Carbon Sequestration in Non-Traditional Tropical Plantations

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Rubber Plantations and Tropical Forests

| Type of Ecosystem | Carbon stock Tons of Mg C/ha |

References |

|---|---|---|

| Primary tropical forest | > 300 | OFAC [109] |

| Mature rubber plantation (Brasilia) | 80 - 150 | Lan et al. [35] |

| Young rubber plantation ≤ 10 years old (Sub-Saharan Africa) | 30 - 50 | Onoji et al. [110] |

| Mono-dominant forest (Ituri/DRC) | 267,5 | Makana et al. [100] |

| Mono-dominant forest (Yangambi/DRC) | 165,5 | Kearsley et al. [111] |

| Mixed forests (DRC) | 160,5 to 199,5 | Panzou et al. [112] |

| Young forests (DRC) | 202 | Panzou et al. [112] |

| Plantation forest (Ethiopia) | 223 | Dick et al. [98] |

| Secondary forest (Congo-Brazzaville) | 167 | Ekoungoulou et al. [97] |

| Teak plantation (Panama) | 3 - 41 | Derwish et al. [113] |

| Mixed forest (Colombia) | 122 - 141 | Saatchi et al. [114] |

| Mixed forest (Venezuela) | 118 - 139 | |

| Mixed forest (Bolivia) | 84 - 94 | |

| Mixed forest (Myanmar) | 146 - 157 | |

| Mixed forest (Papua New Guinea) | 147 - 153 | |

| Acacia magium and Eucalyptus plantation (Vietnam) | 11,5 | Sang et al. [115] |

| Production forest (Indonesia) | 46,32 | Situmorang et al. [116] |

| Mixed forest (Cameroon) | 318 | Zapfack et al. [117] |

| Plantation forests (Ghana) | 56 - 70 | Brown et al. [118] |

| Community forests (Nepal) | 301 | Joshi et al. [119] |

| Agroforestry (Peru) | 106 | Aragon et al. [120] |

| Teak plantation (Thailand) | 45 - 82 | Chayaporn et al. [121] |

| All types of forests (Malaysia) | 157,5 | Raihan [122] |

| Peatland (Congo) | 634 | Crezee et al. [123] |

| Type of forest | Location | Country | Sampling | Tree diameter threshold (cm) | Biomass (Mg ha-1) | Reference | |

| Size (ha) | n | ||||||

| Mono-dominant forest | Dja Ituri Yangambi |

Cameroun DRC DRC |

1 10 1 |

5 2 5 |

D ≥ 10 D ≥ 1 D ≥ 10 |

596 ± 62 535 331 ± 28 |

Djuikouo et al. [99] Makana et al.[100] Kearsley et al. [111] |

| Mixed forest | Dja Ituri Yangambi |

Cameroun DRC DRC |

1 10 1 |

5 2 8 |

D ≥ 10 D ≥ 1 D ≥ 10 |

402 ± 58 399 321 ±48 |

Djuikouo et al. [99] Makana et al. [100] Kearsley et al.[111] |

| Mature forest | Kakamaga Yangambi |

Kenya DRC |

0,04 1 |

46 1 |

D ≥ 5 D ≥ 10 |

498 ± 45 163 |

Glenday [124] Kearsley et al. [111] |

| Young forest | Kakamaga Yangambi |

Kenya DRC |

0,04 1 |

16 3 |

D ≥ 5 D ≥ 10 |

202 ± 40 37 ± 4 |

Glenday [124] Kearsley et al. [111] |

| Semi-caducifolia forest on rich soils | South-east | RCA | 0,5 | 324 | D ≥ 20 | 248 ± 10 | Gourlet-Fleury et al. [104] |

| Semi-caducifolia forest on poor soils | South-east | RCA | 0,5 | 101 | D ≥ 20 | 198 ± 18 | |

| Semi-caducifolia forest (logged) | M’Baïki | RCA | 4 | 3 | D ≥ 10 | 375 ± 58 | Gourlet-Fleury et al. [104] |

| Semi-caducified forest (logged + thinned) | M’Baïki | RCA | 4 | 4 | D ≥ 10 | 356 ± 64 | |

| Semi-caducifolia forest (not exploited) | M’Baïki | RCA | 4 | 3 | D ≥ 10 | 375 ± 40 | |

| Semi-deciduous forest | Mindourou | Cameroun | 0,5 | 5 152 | D ≥ 10 | 348 | Fayolle et al. [102] |

| Evergreen forest | Ma’an | Cameroun | 0,5 | 2 101 | D ≥ 10 | 260 | |

| Natural forest | Hawassa | Ethiopia | 0,12 | 10 | D ≥ 5 | 200 | Wondrade et al. [98] |

| Plantation forest | Hawassa | Ethiopia | 0,12 | 38 | D ≥ 5 | 223 | |

| Semi-deciduous mixed forest | Yangambi Yoko |

DRC DRC |

1 1 |

5 5 |

D ≥ 10 D ≥ 10 |

326 ± 38 382 ± 56 |

Doetterl et al. [103] |

| Agro-forestry | Campo-Ma’an | Cameroun | 0,5 | 8 | D ≥ 5 |

231 ± 45 |

Djomo et al. [95] |

| Production forest | Campo-Ma’an | Cameroun | 0,5 | 8 | D ≥ 5 | 283 ± 51 | |

| Protected forest | Campo-Ma’an | Cameroun | 0,5 | 8 | D ≥ 5 | 278 ± 48 | |

| Secondary forest | Lesio-louna | Congo | 0,12 | 3 | D ≥ 10 | 167 ± 15 | Ekoungoulou et al. [97] |

| Forest gallery | Lesio-louna | Congo | 0,12 | 3 | D ≥ 10 | 92 ± 29 | |

| Olacaceae, Caesalpiaceae, Burseraceae forest | Center | Gabon | 0,3 | 766 | D ≥ 5 | 333 ± 7 | Maniatis et al.[101] |

| Burseraceae, Myristicaceae, Euphorbiaceae | Center | Gabon | 0,3 | 885 | D ≥ 5 | 324 ± 5 | |

| Mountain forest | Monts de Cristal Park | Gabon | 1 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 456 ± 88 | Day et al. [125] |

| Lowland and mountain tropical forest | Park Waka Park Monte Mitra |

Gabon Equatorial Guinea |

1 1 |

5 3 |

D ≥ 10 D ≥ 10 |

394 ± 169 384 ± 42 |

|

| Forests under mountains, plains, and riparian forests | Park Takamanda | Cameroun | 1 | 10 | D ≥ 10 | 351 ± 147 | |

| Semi-deciduous tropical forest | Park Nouabalé Ndoki | Congo | 1 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 281 ± 52 | |

| Atlantic coastal and swamp forest | Park Campo Ma’an | Cameroun | 1 | 3 | D ≥ 10 | 250 ± 64 | |

| Atlantic evergreen forest | Reserve Ejaghan | Cameroun | 1 | 2 | D ≥ 10 | 247 ± 128 | |

| Miombo-type forest with medium-sized trees | Kasangu | Malawi | 1,35 | 15 | D ≥ 5 | 8 ± 5 | Kuyah et al. [91] |

| Forest with low diversity of large canopy trees | Neno | Malawi | 0,9 | 10 | D ≥ 5 | 5 ± 4 | |

| Mountain forest | Hanang | Tanzania | 0,08 | 60 | D ≥ 5 | 55 ± 6 | |

| Miombo forest | Kiolombero | Tanzania | 0,08 | 162 | D ≥ 5 | 26 ± 1 | |

| Low-level natural forest | Mount Kilimanjaro | Tanzania | 0,25 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 361 ± 88 | Ensslin et al. [105] |

| Natural mountain forest | Mount Kilimanjaro | Tanzania | 0,25 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 357 ± 22 | |

| Mountain-level natural forest | Mount Kilimanjaro | Tanzania | 0,25 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 372 ± 4 | |

| Miombo-type open forest at 791 m altitude | Nyanganje | Tanzania | 1 | 1 | D ≥ 10 | 61 ± 2 | Shirima et al. [93] |

| Miombo-type open forest at 502 m altitude | Nyanganje | Tanzania | 1 | 1 | D ≥ 10 | 56 ± 2 | |

| Miombo-type open forest at 1 333 m altitude | Kitonga | Tanzania | 1 | 1 | D ≥ 10 | 48 ± 2 | |

| Miombo-type open forest at 1 500 m altitude | Kitonga | Tanzania | 1 | 1 | D ≥ 10 | 28 ± 1 | |

| Plain forest (˂ 750 m altitude) | Udzungwa | Tanzania | 1 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 14 | Marshall et al. [92] |

| Transition forest (750 – 1 200 m altitude) | Udzungwa | Tanzania | 1 | 5 | D ≥ 10 | 23 | |

| Afromontane forest (> 1200 m altitude) | Udzungwa | Tanzania | 1 | 8 | D ≥ 10 | 21 | |

3.3. Long-Term stability of Carbon Stocks in Rubber Plantations

3.4. The Role of Rubber Plantations in the Context of Climate Change

3.5. Measuring Carbon Sequestration in Rubber Plantations

3.6. Future Research Needs for Policy Formulation to Enhance Carbon Sequestration in Rubber Plantations

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, W.; Wu, J.; Li, X. Intercropping with Cash Crops Promotes Sustainability of Rubber Agroforestry: Insights from Litterfall Production and Associated Carbon and Nutrient Fluxes. Eur. J. Agron., 2024, 154 (August 2023), 127071. [CrossRef]

- Tuddenham, M.; Mazin, V.; Robert, C.; Cozette, L. Consensus Scientifique Sur Rapport Technique Du GIEC 2022 Sur Le Changement Climatique. 2022, 1–54. https://www.citepa.org/wp content/uploads/Citepa_2022_05_d01_INT_GIEC_Attenuation_AR6_Vol3_VF.pdf.

- Pinizzotto.; A., K.; V., G.; J., S.-B.; L., N.; E., G.; E., P.; A., M. Natural Rubber and Climate Change: A Policy Paper. Nat. rubber Clim. Chang. a policy Pap., 2021, No. 6. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Changement Climatique 2021 Les Bases Scientifiques Physiques; 2023. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WG1_SPM_French.pdf.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Han, H.; Shi, Z.; Yang, X. Biomass Accumulation and Carbon Sequestration in an Age-Sequence of Mongolian Pine Plantations in Horqin Sandy Land, China. Forests, 2019, 10 (2), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Kitula, R.A.; Larwanou, M.; Munishi, P.K. T. . M. Carbon Sequestration Potential on Agricultural Lands: A Review of Current Science and Available Practices In Association with: National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition Breakthrough Strategies and Solutions, LLC. Breakthr. Strateg. Solut. LLC, 2015, No. November, 35. https://afforum.org/publication/climate-vulnerability-of-socio-economic-systems-in-different-forest-types-and-coastal-wetlands-in-africa-a-synthesis-in-international-forestry-review-vol-17-s3/.

- FAO. La Situation Des Forêts Du Monde En 2024; 2024. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Etats Des Forets Du Monde; 2022. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Des Forets Du Monde; 2020. [CrossRef]

- Köhl, M.; Lasco, R.; Cifuentes, M.; Jonsson, Ö.; Korhonen, K.T.; Mundhenk, P.; de Jesus Navar, J.; Stinson, G. Changes in Forest Production, Biomass and Carbon: Results from the 2015 UN FAO Global Forest Resource Assessment. For. Ecol. Manage., 2015, 352 (September), 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Gitz; Gohet, E.; Nguyen, A.; Nghia, N.A. Natural Rubber Contributions to Mitigation of Climate Change. XV World For. Congr., 2022, 2–6 (May), 1–9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360992907_Natural_rubber_contributions_to_adaptation_to_climate_change.

- Lal, R.; Smith, P.; Jungkunst, H.F.; Mitsch, W.J.; Lehmann, J.; Ramachandran Nair, P.K.; McBratney, A.B.; De Moraes Sá, J.C.; Schneider, J.; Zinn, Y.L.; et al. The Carbon Sequestration Potential of Terrestrial Ecosystems. J. Soil Water Conserv., 2018, 73 (6), 145A-152A. 10.2489/jswc.73.6.145A.

- Mahmud, A.A.; Raj, A.; Jhariya, M.K. Agroforestry Systems in the Tropics: A Critical Review. Agric. Biol. Res., 2021, 37 (1), 83–87. file:///C:/Users/adm/Downloads/Agroforestry-systems-in-the-tropicsa-critical-review.pdf.

- Cusack, D.F.; Turner, B.L. Fine Root and Soil Organic Carbon Depth Distributions Are Inversely Related Across Fertility and Rainfall Gradients in Lowland Tropical Forests. Ecosystems, 2021, 24 (5), 1075–1092. [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Búrquez, A.; Chidumayo, E.; Colgan, M.S.; Delitti, W.B. C.; Duque, A.; Eid, T.; Fearnside, P.M.; Goodman, R.C.; et al. Improved Allometric Models to Estimate the Aboveground Biomass of Tropical Trees. Glob. Chang. Biol., 2014, 20 (10), 3177–3190. [CrossRef]

- Omokhafe, K. . The Place of the Rubber Tree ( Hevea Brasiliensis ) in Climate Change Omokhafe , K . O . Rubber Res. Inst. Niger. P.M.B. 1049, Benin City, 2020, 1–29. file:///C:/Users/adm/Downloads/Omokhafe222020AJORIB310.pdf.

- Fox, J.M.; Castella, J.C.; Ziegler, A.D.; Westley, S.B. Rubber Plantations Expand in Mountainous Southeast Asia: What Are the Consequences for the Environment? Asia Pacific Issues, 2014, No. 114. file:///C:/Users/adm/Downloads/2014_Fox_RubberPlantations_AsiaPacificIssue.pdf.

- Zou, R.; Sultan, H.; Muse Muhamed, S.; Khan, M.N.; Pan, J.; Liao, W.; Li, Q.; Cheng, S.; Tian, J.; Cao, Z.; et al. Sustainable Integration of Rubber Plantations within Agroforestry Systems in China: Current Research and Future Directions. Plant Sci. Today, 2024, 11 (3), 421–431. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; Mortimer, P.E. Investigation of Rubber Seed Yield in Xishuangbanna and Estimation of Rubber Seed Oil Based Biodiesel Potential in Southeast Asia. Energy, 2014, 69, 837–842. [CrossRef]

- Kitula. Climate Vulnerability of Socio-Economic Systems in Different Forest Types and Coastal Wetlands in Africa: A Synthesis. Int. For. Rev., 2015, 17 (3), 78–91. [CrossRef]

- Birot J and Lelarge K. Étude de La Séquestration Du Carbone Par Les Écosystèmes de La Réserve Naturelle Du Pinail; 2021. https://www.reserve-pinail.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/S%C3%A9questrationCarbone_RNNPinail_2021.pdf.

- Ameray, A.; Bergeron, Y.; Valeria, O.; Montoro Girona, M.; Cavard, X. Forest Carbon Management: A Review of Silvicultural Practices and Management Strategies Across Boreal, Temperate and Tropical Forests. Curr. For. Reports, 2021, 7 (4), 245–266. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, C.S. de; Miccoli, L.S.; Andhini, N.F.; Aranha, S.; Oliveira, L.C. de; Artigo, C.E.; Em, A.A. R.; Em, A.A. R.; Bachman, L.; Chick, K.; et al. No 主観的健康感を中心とした在宅高齢者における 健康関連指標に関する共分散構造分析Title. Rev. Bras. Linguística Apl., 2016, 5 (1), 1689–1699.

- Augusto, L.; Boča, A. Tree Functional Traits, Forest Biomass, and Tree Species Diversity Interact with Site Properties to Drive Forest Soil Carbon. Nat. Commun., 2022, 13 (1), 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Pang, J.; Jepsen, M.R.; Lü, X.; Tang, J. Carbon Stocks across a Fifty Year Chronosequence of Rubber Plantations in Tropical China. Forests, 2017, 8 (6). [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J. P.; Talbot, J.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Qie, L.; Begne, S.K.; Chave, J.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Hubau, W.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; et al. Diversity and Carbon Storage across the Tropical Forest Biome. Sci. Rep., 2017, 7 (1), 39102. [CrossRef]

- Srijanani, V.; Malathi, P.; Anandham, R.; Sellamuthu, K.; Jayashree, R. Harnessing Endophytes: Advanced Insights into Nutrient Acquisition and Plant Growth Enhancement. Plant Sci. Today, 2024, 11 (sp4). [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A. Carbon Sequestration in Agricultural Soils via Cultivation of Cover Crops – A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2015, 200, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Quandt, A.; Neufeldt, H.; Gorman, K. Climate Change Adaptation through Agroforestry: Opportunities and Gaps. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain., 2023, 60, 101244. [CrossRef]

- Bayala, J.; Kalinganire, A.; Sileshi, G.W.; Tondoh, J.E. Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen in Agroforestry Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review. In Improving the Profitability, Sustainability and Efficiency of Nutrients Through Site Specific Fertilizer Recommendations in West Africa Agro-Ecosystems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Blagodatsky, S.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Carbon Balance of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantations: A Review of Uncertainties at Plot, Landscape and Production Level. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2016, 221 (April), 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.D.; Dhyani, B.; Kumar, V.D.; Singh, A.D.; Indar Navsare, R.D.; Singh, A.; Dhyani, B.; Kumar, V.; Singh, A.; Indar Navsare, R. Potential Carbon Sequestration Methods of Agriculture: A Review. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem., 2021, 10 (2), 562–565. https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2021/vol10issue2/PartG/10-2-32-592.pdf.

- Pérez-Piqueres, A.; Martínez-Alcántara, B.; Rodríguez-Carretero, I.; Canet, R.; Quiñones, A. Estimating Carbon Fixation in Fruit Crops. In Fruit Crops; Elsevier, 2020; pp 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, L.; Qi, D.; Wu, Z.; Tang, M.; Yang, C.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, Y. The Opportunities and Challenges Associated with Developing Rubber Plantations as Carbon Sinks in China. J. Rubber Res., 2024, 27 (3), 309–321. [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Wu, Z.; Chen, B.; Xie, G. Species Diversity in a Naturally Managed Rubber Plantation in Hainan Island, South China. Trop. Conserv. Sci., 2017, 10. [CrossRef]

- Koh, L.P.; Wilcove, D.S. Is Oil Palm Agriculture Really Destroying Tropical Biodiversity? Conserv. Lett., 2008, 1 (2), 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.S.; Yadav, S.S.; Gupta, S.R.; Meena, R.S.; Lal, R.; Sheoran, N.S.; Jhariya, M.K. Carbon Sequestration Potential and CO2 Fluxes in a Tropical Forest Ecosystem. Ecol. Eng., 2022, 176, 106541. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Slik, J.W. F.; Jeon, Y.S.; Tomlinson, K.W.; Yang, X.; Wang, J.; Kerfahi, D.; Porazinska, D.L.; Adams, J.M. Tropical Forest Conversion to Rubber Plantation Affects Soil Micro- & Mesofaunal Community & Diversity. Sci. Rep., 2019, 9 (1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gitz, V.; Meybeck, A.; Pinizzotto, S.; Nair, L.; Penot, E.; Baral, H.; Jianchu, X. Sustainable Development of Rubber Plantations: Challenges and Opportunities. XV World For. Congr., 2022, 1–10. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/publications/pdf_files/Papers/WFC2022-Gitz-Meybeck.pdf.

- Gitz, V.; Meybeck, A., Pinizzotto, S.; Nair, L., Penot, E.; Baral, H.; Xu, J. Sustainable Development of Rubber Plantations in a Context of Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustain. Dev. rubber Plant. a Context Clim. Chang. Challenges Oppor., 2020, No. 4. [CrossRef]

- Wibawa, G.; Joshi, L.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Penot, E. Rubber Based Agroforestry Systems (RAS) as Alternatives for Rubber Monoculture System. IRRDB Annu. Meet. Int. Conf., 2006, 22. https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00137596/file/Rubber_based_Agroforestry_Systems_IRRDB_Vietnam_2006.pdf.

- Gitz, V.; Meybeck, A., Pinizzotto, S.; Nair, L., Penot, E.; Baral, H.; Xu, J. Sustainable Development of Rubber Plantations in a Context of Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustain. Dev. rubber Plant. a Context Clim. Chang. Challenges Oppor., 2020, No. December. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.W.; Pang, J.P.; Chen, M.Y.; Guo, X.M.; Zeng, R. Biomass and Its Estimation Model of Rubber Plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Chinese J. Ecol., 2009, 28 (10), 1942–1948. https://www.cje.net.cn/EN/abstract/abstract16321.shtml.

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for Ecosystem Services and Environmental Benefits: An Overview. Agrofor. Syst., 2009, 76 (1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K. R.; Nair, V.D.; Kumar, B.M.; Haile, S.G. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Tropical Agroforestry Systems: A Feasibility Appraisal. Environ. Sci. Policy, 2009, 12 (8), 1099–1111. [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L. Beyond Deforestation: Restoring Forests and Ecosystem Services on Degraded Lands. Science (80-. )., 2008, 320 (5882), 1458–1460. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Lennox, G.D.; Ferreira, J.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A.C.; Nally, R. Mac; Thomson, J.R.; Ferraz, S.F. D. B.; Louzada, J.; Oliveira, V.H. F.; et al. Anthropogenic Disturbance in Tropical Forests Can Double Biodiversity Loss from Deforestation. Nature, 2016, 535 (7610), 144–147. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.M. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Tropical Homegardens. 2006, No. June, 185–204. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science (80-. )., 2011, 333 (6045), 988–993. [CrossRef]

- Teague, R.; Provenza, F.; Kreuter, U.; Steffens, T.; Barnes, M. Multi-Paddock Grazing on Rangelands: Why the Perceptual Dichotomy between Research Results and Rancher Experience? J. Environ. Manage., 2013, 128 (November 2017), 699–717. [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Cerri, C.E. P.; Osborne, B.B.; Paustian, K. Grassland Management Impacts on Soil Carbon Stocks: A New Synthesis. Ecol. Appl., 2017, 27 (2), 662–668. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Bustamante, M.; Uk, P.S.; Brazil, M.B. AR5 WGIII Chapter 11 - Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use (AFOLU). Ar5, Wg3, 2014, No. January, 811–922. https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/103008543/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter11.pdf.

- Siarudin, M.; Rahman, S.A.; Artati, Y.; Indrajaya, Y.; Narulita, S.; Ardha, M.J.; Larjavaara, M. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Agroforestry Systems in Degraded Landscapes in West Java, Indonesia. Forests, 2021, 12 (6), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Dave, R.; Tompkins, E.L.; Schreckenberg, K. Forest Ecosystem Services Derived by Smallholder Farmers in Northwestern Madagascar: Storm Hazard Mitigation and Participation in Forest Management. For. Policy Econ., 2017, 84, 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Shorrocks VM, T. Mineral Nutrition, Growth and Nutrient Cycle of Hevea Brasiliensis. Glob. Sci. B., 2009, No. May, 1–5. file:///C:/Users/adm/Downloads/Shorrocks_1965_Mineral_nutrition_growth.pdf.

- Dejene, T.; Kidane, B.; Yilma, Z.; Teshome, B. Farmers’ Perception towards Farm Level Rubber Tree Planting: A Case Study from Guraferda, South–Western Ethiopia. For. Res. Eng. Int. J., 2018, 2 (4), 192–196. [CrossRef]

- Keskitalo, E.C. H.; Legay, M.; Marchetti, M.; Nocentini, S.; Spathelf, P. The Role of Forestry in National Climate Change Adaptation Policy: Cases from Sweden, Germany, France and Italy. Int. For. Rev., 2015, 17 (1), 30–42. [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.J.; Brahma, B.; Das, A.K. Rubber Plantations and Carbon Management. Rubber Plant. Carbon Manag., 2019, No. May. [CrossRef]

- James, J.; Harrison, R. The Effect of Harvest on Forest Soil Carbon: A Meta-Analysis. Forests, 2016, 7 (12), 308. [CrossRef]

- Nair, P.K. R. Agroforestry Systems and Environmental Quality: Introduction. J. Environ. Qual., 2012, 40 (3), 784–790. [CrossRef]

- Basri, M.H. A.; McCalmont, J.; Kho, L.K.; Hartley, I.P.; Teh, Y.A.; Rumpang, E.; Signori-Müller, C.; Hill, T. Reducing Bias on Soil Surface CO2 Flux Emission Measurements: Case Study on a Mature Oil Palm (Elaeis Guineensis) Plantation on Tropical Peatland in Southeast Asia. Agric. For. Meteorol., 2024, 350, 110002. [CrossRef]

- Germer, J.; Sauerborn, J. Estimation of the Impact of Oil Palm Plantation Establishment on Greenhouse Gas Balance. Environ. Dev. Sustain., 2008, 10 (6), 697–716. [CrossRef]

- Nizami, S.M.; Yiping, Z.; Liqing, S.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Managing Carbon Sinks in Rubber (Hevea Brasilensis) Plantation by Changing Rotation Length in SW China. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9 (12), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- CHENG, C.; WANG, R.; JIANG, J. Variation of Soil Fertility and Carbon Sequestration by Planting Hevea Brasiliensis in Hainan Island, China. J. Environ. Sci., 2007, 19 (3), 348–352. [CrossRef]

- Wauters, J.B.; Coudert, S.; Grallien, E.; Jonard, M.; Ponette, Q. Carbon Stock in Rubber Tree Plantations in Western Ghana and Mato Grosso (Brazil). For. Ecol. Manage., 2008, 255 (7), 2347–2361. [CrossRef]

- Duguma, B., Gockowski, J. & Bakala, J. Smallholder Cacao (Theobroma Cacao Linn.) Cultivation in Agroforestry Systems of West and Central Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Onofre; Abas, E.L.; Salibio, F.C. Potential Carbon Storage of Rubber Plantations. Indian J. Pharm. Biol. Res., 2014, 2 (02), 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Siriki; Yusuf, M.A.; Karembe, Y.; Dembélé, F.; Karembe, M. Séquestration de Carbone Par Les Arbres Des Systèmes Agroforestiers En Zone Soudanienne de La Région de Dioïla Au Mali. 2022, No. May. file:///C:/Users/adm/Downloads/MSAS2020_paper_28%20(1).pdf.

- Yuda, L.D.; Danoedoro, P. Above-Ground Carbon Stock Estimates of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Using Sentinel 2A Imagery: A Case Study in Rubber Plantation of PTPN IX Kebun Getas and Kebun Ngobo, Semarang Regency. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci., 2020, 500 (1). [CrossRef]

- Maggiotto, S.R.; de Oliveira, D.; Jamil Marur, C.; Soares Stivari, S.M.; Leclerc, M.; Wagner-Riddle, C. Potencial de Sequestro de Carbono Em Seringais No Noroeste Do Paraná, Brasil. Acta Sci. - Agron., 2014, 36 (2), 239–245. [CrossRef]

- Cotta, M.K.; Jacovine, L.A. G.; Valverde, S.R.; de Paiva, H.N.; de Castro Virgens Filho, A.; da Silva, M.L. Economic Analysis of the Rubber-Cocoa Intercropping for Generation of Certified Emission Reduction. Rev. Árvore, 2006, 30 (6), 969–979. [CrossRef]

- Orjuela, J.A.; Andrade C, H.J.; Vargas-Valenzuela, Y. Potential of Carbon Storage of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) Plantations in Monoculture and Agroforestry Systems in the Colombian Amazon. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosystems, 2014, 17 (2), 231–240. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/939/93931761009.pdf.

- Kongsager, R.; Mertz, O. The Carbon Sequestration Potential of Tree Crop Plantations. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang., 2013, 18 (8), 1197–1213. [CrossRef]

- Bustillo, E.; Raets, L.; Beeckman, H.; Bourland, N.; Rousseau, M.; Hubau, W.; De Mil, T. Evaluation Du Potentiel Énergétique de La Biomasse Aérienne Ligneuse Des Anciennes Plantations de l’INERA Yangambi. 2018, No. Mai.

- Sain; Schilling, E.B.; Aust, W.M. Evaluation of Coarse Woody Debris and Forest Litter Based on Harvest Treatment in a Tupelo-Cypress Wetland. For. Ecol. Manage., 2012, 280, 2–8. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Forest Soils and Carbon Sequestration. For. Ecol. Manage., 2005, 220 (1–3), 242–258. [CrossRef]

- Genesio, L.; Vaccari, F.P.; Miglietta, F. Black Carbon Aerosol from Biochar Threats Its Negative Emission Potential. Glob. Chang. Biol., 2016, 22 (7), 2313–2314. [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M.; Hector, A. Partitioning Selection and Complementarity in Biodiversity Experiments. Nature, 2001, 412 (6842), 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science (80-. )., 2008, 320 (5882), 1444–1449. [CrossRef]

- Baccini, A.; Walker, W.; Carvalho, L.; Farina, M.; Sulla-Menashe, D.; Houghton, R.A. Tropical Forests Are a Net Carbon Source Based on Aboveground Measurements of Gain and Loss. Science (80-. )., 2017, 358 (6360), 230–234. [CrossRef]

- Griscom, B.W.; Busch, J.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ellis, P.W.; Funk, J.; Leavitt, S.M.; Lomax, G.; Turner, W.R.; Chapman, M.; Engelmann, J.; et al. National Mitigation Potential from Natural Climate Solutions in the Tropics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 2020, 375 (1794), 20190126. [CrossRef]

- Morrison Vila, L.; Ménager, M.; Finegan, B.; Delgado, D.; Casanoves, F.; Aguilar Salas, L.Á.; Castillo, M.; Hernández Sánchez, L.G.; Méndez, Y.; Sánchez Toruño, H.; et al. Above-Ground Biomass Storage Potential in Primary Rain Forests Managed for Timber Production in Costa Rica. For. Ecol. Manage., 2021, 497. [CrossRef]

- Yguel, B.; Piponiot, C.; Mirabel, A.; Dourdain, A.; Hérault, B.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Forget, P.-M.; Fontaine, C. Beyond Species Richness and Biomass: Impact of Selective Logging and Silvicultural Treatments on the Functional Composition of a Neotropical Forest. For. Ecol. Manage., 2019, 433, 528–534. [CrossRef]

- Matala, B.R., Meruva V., K.G. R. Carbon Gold: How Tropical Rainforests Are Key to Climate Survival. Bioscene, 2024, 21 (September), 306–322. https://explorebioscene.com/assets/uploads/doc/475cd-306-322.10000229.pdf.

- Huntingford, C.; Zelazowski, P.; Galbraith, D.; Mercado, L.M.; Sitch, S.; Fisher, R.; Lomas, M.; Walker, A.P.; Jones, C.D.; Booth, B.B. B.; et al. Simulated Resilience of Tropical Rainforests to CO2-Induced Climate Change. Nat. Geosci., 2013, 6 (4), 268–273. [CrossRef]

- Pugh, T.A. M.; Lindeskog, M.; Smith, B.; Poulter, B.; Arneth, A.; Haverd, V.; Calle, L. Role of Forest Regrowth in Global Carbon Sink Dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 2019, 116 (10), 4382–4387. [CrossRef]

- Slik, J.W. F.; Paoli, G.; McGuire, K.; Amaral, I.; Barroso, J.; Bastian, M.; Blanc, L.; Bongers, F.; Boundja, P.; Clark, C.; et al. Large Trees Drive Forest Aboveground Biomass Variation in Moist Lowland Forests across the Tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 2013, 22 (12), 1261–1271. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.L.; Sonké, B.; Sunderland, T.; Begne, S.K.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; van der Heijden, G.M. F.; Phillips, O.L.; Affum-Baffoe, K.; Baker, T.R.; Banin, L.; et al. Above-Ground Biomass and Structure of 260 African Tropical Forests. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 2013, 368 (1625). [CrossRef]

- Bastin, J.-F.; Barbier, N.; Réjou-Méchain, M.; Fayolle, A.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Maniatis, D.; de Haulleville, T.; Baya, F.; Beeckman, H.; Beina, D.; et al. Seeing Central African Forests through Their Largest Trees. Sci. Rep., 2015, 5 (1), 13156. [CrossRef]

- Velasco, E.; Roth, M.; Tan, S.H.; Quak, M.; Nabarro, S.D. A.; Norford, L. The Role of Vegetation in the CO2 Flux from a Tropical Urban Neighbourhood. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 2013, 13 (20), 10185–10202. [CrossRef]

- Kuyah, S.; Sileshi, G.W.; Njoloma, J.; Mng’omba, S.; Neufeldt, H. Estimating Aboveground Tree Biomass in Three Different Miombo Woodlands and Associated Land Use Systems in Malawi. Biomass and Bioenergy, 2014, 66, 214–222. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.R.; Willcock, S.; Platts, P.J.; Lovett, J.C.; Balmford, A.; Burgess, N.D.; Latham, J.E.; Munishi, P.K. T.; Salter, R.; Shirima, D.D.; et al. Measuring and Modelling Above-Ground Carbon and Tree Allometry along a Tropical Elevation Gradient. Biol. Conserv., 2012, 154, 20–33. [CrossRef]

- Shirima, D.D.; Totland, Ø.; Munishi, P.K. T.; Moe, S.R. Relationships between Tree Species Richness, Evenness and Aboveground Carbon Storage in Montane Forests and Miombo Woodlands of Tanzania. Basic Appl. Ecol., 2015, 16 (3), 239–249. [CrossRef]

- Panzou, G.J. L.; Doucet, J.-L.; Loumeto, J.-J.; Biwole, A.; Bauwens, S.; Fayolle, A. Biomasse et Stocks de Carbone Des Forêts Tropicales Africaines (Synthèse Bibliographique). Base, 2016, 20 (4), 508–522. [CrossRef]

- Djomo, A.N.; Knohl, A.; Gravenhorst, G. Estimations of Total Ecosystem Carbon Pools Distribution and Carbon Biomass Current Annual Increment of a Moist Tropical Forest. For. Ecol. Manage., 2011, 261 (8), 1448–1459. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J. P.; Lewis, S.L.; Affum-Baffoe, K.; Castilho, C.; Costa, F.; Sanchez, A.C.; Ewango, C.E. N.; Hubau, W.; Marimon, B.; Monteagudo-Mendoza, A.; et al. Long-Term Thermal Sensitivity of Earth’s Tropical Forests. Science (80-. )., 2020, 368 (6493), 869–874. [CrossRef]

- Ekoungoulou, R.; Niu, S.; Joël Loumeto, J.; Averti Ifo, S.; Enock Bocko, Y.; Mikieleko, F.; Eusebe, D.M.; Senou, H.; Liu, X. Evaluating the Carbon Stock in Above-and Below- Ground Biomass in a Moist Central African Forest " Evaluating the Carbon Stock in Above-and Below-Ground Biomass in a Moist Central African. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Sci., 2015, 3 (2), 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Dick OB, W.N. Estimating above Ground Biomass and Carbon Stock in the Lake Hawassa Watershed, Ethiopia by Integrating Remote Sensing and Allometric Equations. For. Res. Open Access, 2015, 04 (03). [CrossRef]

- Djuikouo, M.N. K.; Doucet, J.L.; Nguembou, C.K.; Lewis, S.L.; Sonké, B. Diversity and Aboveground Biomass in Three Tropical Forest Types in the Dja Biosphere Reserve, Cameroon. Afr. J. Ecol., 2010, 48 (4), 1053–1063. [CrossRef]

- Makana, J.-R.; Ewango, C.N.; McMahon, S.M.; Thomas, S.C.; Hart, T.B.; Condit, R. Demography and Biomass Change in Monodominant and Mixed Old-Growth Forest of the Congo. J. Trop. Ecol., 2011, 27 (5), 447–461. [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, D.; Malhi, Y.; Saint André, L.; Mollicone, D.; Barbier, N.; Saatchi, S.; Henry, M.; Tellier, L.; Schwartzenberg, M.; White, L. Evaluating the Potential of Commercial Forest Inventory Data to Report on Forest Carbon Stock and Forest Carbon Stock Changes for REDD+ under the UNFCCC. Int. J. For. Res., 2011, 2011, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Loubota Panzou, G.J.; Drouet, T.; Swaine, M.D.; Bauwens, S.; Vleminckx, J.; Biwole, A.; Lejeune, P.; Doucet, J.-L. Taller Trees, Denser Stands and Greater Biomass in Semi-Deciduous than in Evergreen Lowland Central African Forests. For. Ecol. Manage., 2016, 374, 42–50. [CrossRef]

- Doetterl, S.; Kearsley, E.; Bauters, M.; Hufkens, K.; Lisingo, J.; Baert, G.; Verbeeck, H.; Boeckx, P. Aboveground vs. Belowground Carbon Stocks in African Tropical Lowland Rainforest: Drivers and Implications. PLoS ONE, 2015, 10 (11), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Rossi, V.; Rejou-Mechain, M.; Freycon, V.; Fayolle, A.; Saint-André, L.; Cornu, G.; Gérard, J.; Sarrailh, J.-M.; Flores, O.; et al. Environmental Filtering of Dense-Wooded Species Controls above-Ground Biomass Stored in African Moist Forests. J. Ecol., 2011, 99 (4), 981–990. [CrossRef]

- Ensslin, A.; Rutten, G.; Pommer, U.; Zimmermann, R.; Hemp, A.; Fischer, M. Effects of Elevation and Land Use on the Biomass of Trees, Shrubs and Herbs at Mount Kilimanjaro. Ecosphere, 2015, 6 (3), 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chazdon, R.L.; Broadbent, E.N.; Rozendaal, D.M. A.; Bongers, F.; Zambrano, A.M. A.; Aide, T.M.; Balvanera, P.; Becknell, J.M.; Boukili, V.; Brancalion, P.H. S.; et al. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Second-Growth Forest Regeneration in the Latin American Tropics. Sci. Adv., 2016, 2 (5). [CrossRef]

- Poorter, L.; Bongers, F.; Aide, T.M.; Almeyda Zambrano, A.M.; Balvanera, P.; Becknell, J.M.; Boukili, V.; Brancalion, P.H. S.; Broadbent, E.N.; Chazdon, R.L.; et al. Biomass Resilience of Neotropical Secondary Forests. Nature, 2016, 530 (7589), 211–214. [CrossRef]

- Mitchard, E.T. A. The Tropical Forest Carbon Cycle and Climate Change. Nature, 2018, 559 (7715), 527–534. [CrossRef]

- OFAC. Les Forêts Du Bassin Du Congo - Etat Des Forêts 2021. Off. des Publ. l’Union Eur., 2021, 1–425. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Guillaume-Lescuyer/publication/360689049_THE_2021_STATE_OF_THE_FOREST_Book_abstract/links/63d421cbc465a873a262ab97/THE-2021-STATE-OF-THE-FOREST-Book-abstract.pdf#page=408.

- Onoji, S.E.; Iyuke, S.E.; Igbafe, A.I.; Nkazi, D.B. Rubber Seed Oil: A Potential Renewable Source of Biodiesel for Sustainable Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Convers. Manag., 2016, 110, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Kearsley, E.; De Haulleville, T.; Hufkens, K.; Kidimbu, A.; Toirambe, B.; Baert, G.; Huygens, D.; Kebede, Y.; Defourny, P.; Bogaert, J.; et al. Conventional Tree Height-Diameter Relationships Significantly Overestimate Aboveground Carbon Stocks in the Central Congo Basin. Nat. Commun., 2013, 4. [CrossRef]

- Panzou, G.J. L.; Doucet, J.-L.; Loumeto, J.-J.; Biwole, A.; Bauwens, S.; Fayolle, A. Biomasse et Stocks de Carbone Des Forêts Tropicales Africaines (Synthèse Bibliographique). BASE, 2016, 508–522. [CrossRef]

- Derwisch, S.; Schwendenmann, L.; Olschewski, R.; Hölscher, D. Estimation and Economic Evaluation of Aboveground Carbon Storage of Tectona Grandis Plantations in Western Panama. New For., 2009, 37 (3), 227–240. [CrossRef]

- Saatchi, S.S.; Harris, N.L.; Brown, S.; Lefsky, M.; Mitchard, E.T. A.; Salas, W.; Zutta, B.R.; Buermann, W.; Lewis, S.L.; Hagen, S.; et al. Benchmark Map of Forest Carbon Stocks in Tropical Regions across Three Continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2011, 108 (24), 9899–9904. [CrossRef]

- Sang, P.M.; Lamb, D.; Bonner, M.; Schmidt, S. Carbon Sequestration and Soil Fertility of Tropical Tree Plantations and Secondary Forest Established on Degraded Land. Plant Soil, 2013, 362 (1–2), 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Pandapotan Situmorang, J.; Sugianto, S.; . D. Estimation of Carbon Stock Stands Using EVI and NDVI Vegetation Index in Production Forest of Lembah Seulawah Sub-District, Aceh Indonesia. Aceh Int. J. Sci. Technol., 2016, 5 (3), 126–139. [CrossRef]

- Zapfack, L.; Noiha, N.; Tabue, M. Economic Estimation of Carbon Storage and Sequestration as Ecossytem Services of Protected Areas: A Case Study of Lobeke National Park. J. Trop. For. Sci., 2016, 28 (4), 406–415. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43956807.pdf?casa_token=jT25MMYmOhEAAAAA:JTYgN7O6hKod5MCb8sec4-GkFx_4g3ujthj7mKyxzIqo2ho9YtHka5UpmW-LgKvqSbzmVd3CQWGBRgUOnSyR5psW4Z5hQSoYoWZfvIT0kJ3fEFJ17EG7.

- Brown, H.C. A.; Berninger, F.A.; Larjavaara, M.; Appiah, M. Above-Ground Carbon Stocks and Timber Value of Old Timber Plantations, Secondary and Primary Forests in Southern Ghana. For. Ecol. Manage., 2020, 472, 118236. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Singh, H.; Chhetri, R. Assessment of Carbon Sequestration Potential in Degraded and Non-Degraded Community Forests in Terai Region of Nepa. 2020, 36 (August), 113–121. [CrossRef]

- Aragón, S.; Salinas, N.; Nina-Quispe, A.; Qquellon, V.H.; Paucar, G.R.; Huaman, W.; Porroa, P.C.; Olarte, J.C.; Cruz, R.; Muñiz, J.G.; et al. Aboveground Biomass in Secondary Montane Forests in Peru: Slow Carbon Recovery in Agroforestry Legacies. Glob. Ecol. Conserv., 2021, 28, e01696. [CrossRef]

- Chayaporn, P.; Sasaki, N.; Venkatappa, M.; Abe, I. Assessment of the Overall Carbon Storage in a Teak Plantation in Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand – Implications for Carbon-Based Incentives. Clean. Environ. Syst., 2021, 2, 100023. [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. Toward Sustainable and Green Development in Chile: Dynamic Influences of Carbon Emission Reduction Variables. Innov. Green Dev., 2023, 2 (2), 100038. [CrossRef]

- Crezee, B.; Dargie, G.C.; Ewango, C.E. N.; Mitchard, E.T. A.; Emba B., O.; Kanyama T., J.; Bola, P.; Ndjango, J.-B. N.; Girkin, N.T.; Bocko, Y.E.; et al. Mapping Peat Thickness and Carbon Stocks of the Central Congo Basin Using Field Data. Nat. Geosci., 2022, 15 (8), 639–644. [CrossRef]

- Glenday, J. Carbon Storage and Emissions Offset Potential in an East African Tropical Rainforest. For. Ecol. Manage., 2006, 235 (1–3), 72–83. [CrossRef]

- DAY, M.; BALDAUF, C.; RUTISHAUSER, E.; SUNDERLAND, T.C. H. Relationships between Tree Species Diversity and Above-Ground Biomass in Central African Rainforests: Implications for REDD. Environ. Conserv., 2014, 41 (1), 64–72. [CrossRef]

- Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Mortier, F.; Fayolle, A.; Baya, F.; Ouédraogo, D.; Bénédet, F.; Picard, N. Tropical Forest Recovery from Logging: A 24 Year Silvicultural Experiment from Central Africa. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 2013, 368 (1625), 20120302. [CrossRef]

- Eba’a Atyi, R.; Hiol Hiol, F.; Lescuyer, G.; Mayaux, P.; Defourny, P.; Bayol, N.; Saracco, F.; Pokem, D.; Sufo Kankeu, R.; Nasi, R.. Les Forêts Du Bassin Du Congo : État Des Forêts 2021; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Medjibe, V.P.; Putz, F.E.; Starkey, M.P.; Ndouna, A.A.; Memiaghe, H.R. Impacts of Selective Logging on Above-Ground Forest Biomass in the Monts de Cristal in Gabon. For. Ecol. Manage., 2011, 262 (9), 1799–1806. [CrossRef]

- Gideon Neba, S.; Kanninen, M.; Eba’a Atyi, R.; Sonwa, D.J. Assessment and Prediction of Above-Ground Biomass in Selectively Logged Forest Concessions Using Field Measurements and Remote Sensing Data: Case Study in South East Cameroon. For. Ecol. Manage., 2014, 329, 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Ndjondo, M.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Manlay, R.J.; Engone Obiang, N.L.; Ngomanda, A.; Romero, C.; Claeys, F.; Picard, N. Opportunity Costs of Carbon Sequestration in a Forest Concession in Central Africa. Carbon Balance Manag., 2014, 9 (1), 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hubau, W.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Affum-Baffoe, K.; Beeckman, H.; Cuní-Sanchez, A.; Daniels, A.K.; Ewango, C.E. N.; Fauset, S.; Mukinzi, J.M.; et al. Asynchronous Carbon Sink Saturation in African and Amazonian Tropical Forests. Nature, 2020, 579 (7797), 80–87. [CrossRef]

- Lung, M.; Espira, A. The Influence of Stand Variables and Human Use on Biomass and Carbon Stocks of a Transitional African Forest: Implications for Forest Carbon Projects. For. Ecol. Manage., 2015, 351, 36–46. [CrossRef]

- Cazzolla Gatti, R.; Castaldi, S.; Lindsell, J.A.; Coomes, D.A.; Marchetti, M.; Maesano, M.; Di Paola, A.; Paparella, F.; Valentini, R. The Impact of Selective Logging and Clearcutting on Forest Structure, Tree Diversity and Above-ground Biomass of African Tropical Forests. Ecol. Res., 2015, 30 (1), 119–132. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Baltensweiler, A.; James, J.; Rigling, A.; Hagedorn, F. A Global Synthesis and Conceptualization of the Magnitude and Duration of Soil Carbon Losses in Response to Forest Disturbances. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 2024, 33 (1), 141–150. [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D.; Aide, T.M. When and Where to Actively Restore Ecosystems? For. Ecol. Manage., 2011, 261 (10), 1558–1563. [CrossRef]

- Ahrends, A.; Hollingsworth, P.M.; Ziegler, A.D.; Fox, J.M.; Chen, H.; Su, Y.; Xu, J. Current Trends of Rubber Plantation Expansion May Threaten Biodiversity and Livelihoods. Glob. Environ. Chang., 2015, 34, 48–58. [CrossRef]

- Goh, K. . Carbon Storage in Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantations in Peninsular Malaysia. Plant Soil, 2007, 33 (1), 15–28.

- Pinizzotto, S.; Aziz, A.; Gitz, V.; Sainte-Beuve, J.; Nair, L.; Gohet, E.; Penot, E.; Meybeck, A.. Natural Rubber Systems and Climate Change: Proceedings and Extended Abstracts from the Online Workshop, 23–25 June 2020. Nat. rubber Syst. Clim. Chang. Proc. Ext. Abstr. from online Work. 23–25 June 2020, 2021, No. May, 23–25. [CrossRef]

- Hazir, M.H. M.; Kadir, R.A.; Gloor, E.; Galbraith, D. Effect of Agroclimatic Variability on Land Suitability for Cultivating Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) and Growth Performance Assessment in the Tropical Rainforest Climate of Peninsular Malaysia. Clim. Risk Manag., 2020, 27, 100203. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.; Xia, T.; Gu, S.; Liang, J.; Xu, C.-Y. Short-Term Evapotranspiration Forecasting of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Agronomy, 2023, 13 (4), 1013. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Shi, Z.; Gu, S.; Wang, T.; Zhu, W.; Feng, G. Impact of Climate Change and Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantation Expansion on Reference Evapotranspiration in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Front. Plant Sci., 2022, 13 (March). [CrossRef]

- De Roover, E. DE. Analyse De La Chaîne De Valeur Hevea Selon La Methode Vca4D, Dans Les Territoires De Lodja Et Lomela, Province Du Sankuru, Rdc, En Vue De La Relance De La Filiere. Https://Matheo.Uliege.Be, 2022, 89. https://matheo.uliege.be/handle/2268.2/13863.

- Ajalli, M. Conceptual Modeling of Determining Factors in the Assessment of Sustainability and Resilience of the Supply Chain: A Study of Rubber Industry Suppliers in Iran. J. Rubber Res., 2024, 27 (2), 259–274. [CrossRef]

- Srisawasdi, W.; Cortes, J. Natural Rubber Trade and Production Toward Sustainable Development Goals: A Global Panel Regression Analysis. ABAC J., 2024, 44 (4). [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.F.; Akber, M.A.; Smith, C.; Aziz, A.A. The Dynamics of Rubber Production in Malaysia: Potential Impacts, Challenges and Proposed Interventions. For. Policy Econ., 2021, 127, 102449. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, C.L.; Rimbawanto, A.; Page, D.E. Management of Basidiomycete Root- and Stem-rot Diseases in Oil Palm, Rubber and Tropical Hardwood Plantation Crops. For. Pathol., 2014, 44 (6), 428–446. [CrossRef]

- Monkai, J.; Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Diversity and Ecology of Soil Fungal Communities in Rubber Plantations. Fungal Biol. Rev., 2017, 31 (1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ainusyifa, F.; Lestari, R.; Yuniati, R. A Review of Fungal Disease in Hevea Brasiliensis (Willd. Ex A. Juss.) Mull. Arg.: From Identification to Scientific Investigation for Control Strategies. J. Penelit. Pendidik. IPA, 2024, 10 (12), 977–987. [CrossRef]

- Gitz, V.; Meybeck, A.; Pinizzotto, S.; Nair, L.; Penot, E.; Baral, H.; Xu, J. . Sustainable Development of Rubber Plantations in a Context of Climate Change: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustain. Dev. rubber Plant. a Context Clim. Chang. Challenges Oppor., 2020, No. May. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.; Moraes, L.A. C.; Fageria, N.K. Potential of Rubber Plantations for Environmental Conservation in Amazon Region. 2009.

- Gohet, E.; Cauchy, T.; Des, S.; Premieres, M.; Gay, F. Climate Change and Rubber Production : Risks Scenarios and Research Needs for Adaptation . 2023, No. April 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eric-Gohet/publication/379892750_Climate_Change_and_Rubber_Production_Risks_Scenarios_and_Research_Needs_for_Adaptation/links/66200b1339e7641c0bd3fe9b/Climate-Change-and-Rubber-Production-Risks-Scenarios-and-Research-Needs-for-Adaptation.pdf.

- Moreira, A.; Moraes, L. a C.; Fageria, N.K. Potential of Rubber Plantations for Environmental Conservation in Amazon Region. Glob. Sci. B., 2009, 1–5.

- Miller, S.A.; Habert, G.; Myers, R.J.; Harvey, J.T. Assessing the Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Rubber Plantations: A Comparative Study. J. Clean. Prod., 2021, 278 (10), 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, E.; Richards, M.; Smith, P.; Havlík, P.; Obersteiner, M.; Tubiello, F.N.; Herold, M.; Gerber, P.; Carter, S.; Reisinger, A.; et al. Impact of Agricultural Practices on Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A Meta-Analysis. Glob. Chang. Biol., 2016, 22 (12), 3859–3864. [CrossRef]

- FAO. Rubber (Naturel) FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. Rubber FAOSTAT, Food Agric. Organ. United Nations pdf, 2023, 61 (10), 480–483. https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=FAO&f=itemCode%3A836.

- Satakhun, D.; Chayawat, C.; Sathornkich, J.; Phattaralerphong, J.; Chantuma, P.; Thaler, P.; Gay, F.; Nouvellon, Y.; Kasemsap, P. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Rubber-Tree Plantation in Thailand. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2019, 526 (1). [CrossRef]

- Blagodatsky, S.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Carbon Balance of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantations: A Review of Uncertainties at Plot, Landscape and Production Level. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2016, 221, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Ebuy, J.; Lokombe, J.P.; Ponette, Q.; Sonwa, D.; Picard, N. Allometric Equation for Predicting Aboveground Biomass of Three Tree Species. J. Trop. For. Sci., 2011, 23 (2), 125–132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23616912.

- Golbon, R.; Ogutu, J.O.; Cotter, M.; Sauerborn, J. Rubber Yield Prediction by Meteorological Conditions Using Mixed Models and Multi-Model Inference Techniques. Int. J. Biometeorol., 2015, 59 (12), 1747–1759. [CrossRef]

- Petsri, S.; Chidthaisong, A.; Pumijumnong, N.; Wachrinrat, C. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Carbon Stock Changes in Rubber Tree Plantations in Thailand from 1990 to 2004. J. Clean. Prod., 2013, 52, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- MUNASINGHE, E.S.; RODRIGO, V.H. L.; GUNAWARDENA, U.A. D. P. MODUS OPERANDI IN ASSESSING BIOMASS AND CARBON IN RUBBER PLANTATIONS UNDER VARYING CLIMATIC CONDITIONS. Exp. Agric., 2014, 50 (1), 40–58. [CrossRef]

- Jing-Cheng, Y.; Jian-Hui, H.; Jian-Wei, T.; Qing-Min, P.; Xing-Guo, H. CARBON SEQUESTRATION IN RUBBER TREE PLANTATIONS ESTABLISHED ON FORMER ARABLE LANDS IN XISHUANGBANNA, SW CHINA. Chinese J. Plant Ecol., 2005, 29 (2), 296–303. [CrossRef]

- Chakarn Saengruksawong, Soontorn Khamyong, Niwat Anongrak, A.; Pinthong, J. Growths and Carbon Stocks of Para Rubber Plantations on Phonpisai Soil Series in Northeastern Thailand. Plant Sci., 2011, 19 (December), 1–16. https://www.thaiscience.info/Journals/Article/SJST/10890449.pdf.

- KOSEI SONE, NORIE WATANABE, MASAO TAKASE, T.H. A. K. G. ( Hevea Brasiliensis ) in North Sumatra. J. Rubber Res., 2014, 17 (2), 115–127. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kosei-Sone-2/publication/285032539_Carbon_Sequestration_Tree_Biomass_Growth_and_Rubber_Yield_of_PB260_Clone_of_Rubber_Tree_Hevea_brasiliensis_in_North_Sumatra/links/5b728d07299bf14c6da19a49/Carbon-Sequestration-Tree-Biomass-Growth-and-Rubber-Yield-of-PB260-Clone-of-Rubber-Tree-Hevea-brasiliensis-in-North-Sumatra.pdf.

- Lusiana, B. Uncertainty of Net Carbon Loss: Error Propagation from Land Cover Classification and Plot-Level Carbon Stock. Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in Land Use Change Modelling. ICRAF Univ. Hohenheim, Bogor, Indones., 2014, 159. https://doi.org/Lusiana, B., 2014. Uncertainty of net carbon loss: error propagation from land cover classification and plot-level carbon stock. Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in Land Use Change Modelling. ICRAF and University of Hohenheim, Bogor, Indonesia 159 p. [CrossRef]

- Palm, C.A.; Woomer, P.L.; Alegre, J.; Arevalo, L.; Castilla, C.; Cordeiro, D.G.; Feigl, B.; Hairiah, K.; Mendes, A.; Moukam, A.; et al. Carbon Sequestration and Trace Gas Emissions in Slash-and-Burn and Alternative Land Uses in the Humid Tropics. ASB Clim. Chang. Work. Gr., 2014, No. May 2014, 29. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/28165/.

- Hairiah, K.; Sonya, D.; Agus, F.; Velarde, S.; Ekadinata, A.; Rahayu, S.; van Noordwijk, M. Measuring Carbon Stocks Accross Land Use Systems; 2011. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/33313/.

- Lang, R.; Goldberg, S.; Blagodatsky, S.; Piepho, H.P.; Harrison, R.D.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Converting Forests into Rubber Plantations Weakened the Soil CH4 Sink in Tropical Uplands. L. Degrad. Dev., 2019, 30 (18), 2311–2322. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Overview. 2019 Refinement to 2006 IPCC Guidel. Natl. Greenh. Gas Invent., 2019, 2, 5–13. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/2019-refinement-to-the-2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/.

- Ren, Y.; Lin, F.; Jiang, C.; Tang, J.; Fan, Z.; Feng, D.; Zeng, X.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; Olatunji, O.A. Understory Vegetation Management Regulates Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Storage in Rubber Plantations. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems, 2023, 127 (2), 209–224. [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Yang, C.; Wu, Z.; Sun, R.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X. Network Complexity of Rubber Plantations Is Lower than Tropical Forests for Soil Bacteria but Not for Fungi. SOIL, 2022, 8 (1), 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Wu, Z.; Lan, G.; Yang, C.; Fraedrich, K. Effects of Rubber Plantations on Soil Physicochemical Properties on Hainan Island, China. J. Environ. Qual., 2021, 50 (6), 1351–1363. [CrossRef]

- Satakhun, D.; Chayawat, C.; Sathornkich, J.; Phattaralerphong, J.; Chantuma, P.; Thaler, P.; Gay, F.; Nouvellon, Y.; Kasemsap, P. Carbon Sequestration Potential of Rubber-Tree Plantation in Thailand. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., 2019, 526 (1). [CrossRef]

- Blagodatsky, S.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Carbon Balance of Rubber (Hevea Brasiliensis) Plantations: A Review of Uncertainties at Plot, Landscape and Production Level. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 2016, 221, 8–19. [CrossRef]

- Ebuy, J.; Lokombe, J.P.; Ponette, Q.; Sonwa, D.; Picard, N. Allometric Equation for Predicting Aboveground Biomass of Three Tree Species. J. Trop. For. Sci., 2011, 23 (2), 125–132. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23616912.

- Golbon, R.; Ogutu, J.O.; Cotter, M.; Sauerborn, J. Rubber Yield Prediction by Meteorological Conditions Using Mixed Models and Multi-Model Inference Techniques. Int. J. Biometeorol., 2015, 59 (12), 1747–1759. [CrossRef]

- Petsri, S.; Chidthaisong, A.; Pumijumnong, N.; Wachrinrat, C. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Carbon Stock Changes in Rubber Tree Plantations in Thailand from 1990 to 2004. J. Clean. Prod., 2013, 52, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- MUNASINGHE, E.S.; RODRIGO, V.H. L.; GUNAWARDENA, U.A. D. P. MODUS OPERANDI IN ASSESSING BIOMASS AND CARBON IN RUBBER PLANTATIONS UNDER VARYING CLIMATIC CONDITIONS. Exp. Agric., 2014, 50 (1), 40–58. [CrossRef]

- Jing-Cheng, Y.; Jian-Hui, H.; Jian-Wei, T.; Qing-Min, P.; Xing-Guo, H. CARBON SEQUESTRATION IN RUBBER TREE PLANTATIONS ESTABLISHED ON FORMER ARABLE LANDS IN XISHUANGBANNA, SW CHINA. Chinese J. Plant Ecol., 2005, 29 (2), 296–303. [CrossRef]

- Chakarn Saengruksawong, Soontorn Khamyong, Niwat Anongrak, A.; Pinthong, J. Growths and Carbon Stocks of Para Rubber Plantations on Phonpisai Soil Series in Northeastern Thailand. Plant Sci., 2011, 19 (December), 1–16. https://www.thaiscience.info/Journals/Article/SJST/10890449.pdf.

- KOSEI SONE, NORIE WATANABE, MASAO TAKASE, T.H. A. K. G. ( Hevea Brasiliensis ) in North Sumatra. J. Rubber Res., 2014, 17 (2), 115–127. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kosei-Sone-2/publication/285032539_Carbon_Sequestration_Tree_Biomass_Growth_and_Rubber_Yield_of_PB260_Clone_of_Rubber_Tree_Hevea_brasiliensis_in_North_Sumatra/links/5b728d07299bf14c6da19a49/Carbon-Sequestration-Tree-Biomass-Growth-and-Rubber-Yield-of-PB260-Clone-of-Rubber-Tree-Hevea-brasiliensis-in-North-Sumatra.pdf.

- Lusiana, B. Uncertainty of Net Carbon Loss: Error Propagation from Land Cover Classification and Plot-Level Carbon Stock. Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in Land Use Change Modelling. ICRAF Univ. Hohenheim, Bogor, Indones., 2014, 159. https://doi.org/Lusiana, B., 2014. Uncertainty of net carbon loss: error propagation from land cover classification and plot-level carbon stock. Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in Land Use Change Modelling. ICRAF and University of Hohenheim, Bogor, Indonesia 159 p. [CrossRef]

- Palm, C.A.; Woomer, P.L.; Alegre, J.; Arevalo, L.; Castilla, C.; Cordeiro, D.G.; Feigl, B.; Hairiah, K.; Mendes, A.; Moukam, A.; et al. Carbon Sequestration and Trace Gas Emissions in Slash-and-Burn and Alternative Land Uses in the Humid Tropics. ASB Clim. Chang. Work. Gr., 2014, No. May 2014, 29. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/28165/.

- Hairiah, K.; Sonya, D.; Agus, F.; Velarde, S.; Ekadinata, A.; Rahayu, S.; van Noordwijk, M. Measuring Carbon Stocks Accross Land Use Systems; 2011. https://www.cifor-icraf.org/knowledge/publication/33313/.

- Lang, R.; Goldberg, S.; Blagodatsky, S.; Piepho, H.P.; Harrison, R.D.; Xu, J.; Cadisch, G. Converting Forests into Rubber Plantations Weakened the Soil CH4 Sink in Tropical Uplands. L. Degrad. Dev., 2019, 30 (18), 2311–2322. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Overview. 2019 Refinement to 2006 IPCC Guidel. Natl. Greenh. Gas Invent., 2019, 2, 5–13. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/2019-refinement-to-the-2006-ipcc-guidelines-for-national-greenhouse-gas-inventories/.

- Ren, Y.; Lin, F.; Jiang, C.; Tang, J.; Fan, Z.; Feng, D.; Zeng, X.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C.; Olatunji, O.A. Understory Vegetation Management Regulates Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Storage in Rubber Plantations. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems, 2023, 127 (2), 209–224. [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Yang, C.; Wu, Z.; Sun, R.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X. Network Complexity of Rubber Plantations Is Lower than Tropical Forests for Soil Bacteria but Not for Fungi. SOIL, 2022, 8 (1), 149–161. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Wu, Z.; Lan, G.; Yang, C.; Fraedrich, K. Effects of Rubber Plantations on Soil Physicochemical Properties on Hainan Island, China. J. Environ. Qual., 2021, 50 (6), 1351–1363. [CrossRef]

| Type de systèmes | Rate of Carbone sequestered tCO2/ha/year |

Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agroforestry systems | 5 à 20 | Biological diversity Improvement of soil fertility |

Competition between crops | [44,45] |

| Secondary forests | 10 à 50 | Biological diversity Vegetation restoration Biodiversity Ecosystem services |

Dépendance on environmental conditions Vunerability to fire |

[46,47] |

| Rubber plantations | 5 à 30 | Vegetation restoration Air retention Biodiversity enchancement |

Dependance on humain intervention | [48,49] |

| Abandoned pastures | 2 à 10 | Restoration of vegetation Air retention Biofiversity enchancement |

Risk of invasion | [50,51] |

| Type | Age (years) | Area (tC/ha) | Location | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber | Mature plantation | 275,1 | Brazil | Shorrocks [55] |

| Rubber | 20 | 257,95 | Philippines | Onofore et al. [67] |

| Rubber | 35 | 246,23 | Philippines | |

| Agroforestry system | - | 195 | Dioïla/Mali | Siriki et al. [68] |

| Rubber | Mature plantation | 198,4 | Ngobo, Indonesia | Yuda & Danoedoro [69] |

| Rubber | 15 | 146,30 | Parana State/Brazil | Maggiotto et al. [70] |

| Rubber | 34 | 169,22 | Brazil | Cotta et al. [71] |

| Rubber | 40 | 186,65 | China | Nizami et al. [63] |

| Rubber | 8 - 20 | 156 | Colombia | Orjuela et al [72] |

| Agroforest/rubber | 8 - 20 | 159 | Colombia | |

| Rubber | - | 214 | Ghana | Kongasager & Mertz [73] |

| Cocoa | - | 65 | Ghana | |

| Orange | - | 76 | Ghana | |

| Oil palm | - | 45 | Ghana | |

| Oil palm | Mature plantation | 173,81 | Yangambi/DRC | Bustillo et al. [74] |

| Rubber | Mature plantation | 337,33 | Yangambi/DRC |

| Carbon stock, (Mg C ha-1) | Pool description | Rotation length (years) | Tree density per ha | Location | Refence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51.2a | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 35 | 469 | Brazil, Mato Crosso | Wauters et al. [65] |

| 63.7a | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 25 | 419 | Thailand | Pestri et al. [160] |

| 42.4b | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 25 | No data | China, Xishuangbanna | Tang et al. [43] |

| 45.3b | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 30 | 375 | China, Hainan | Cheng et al. [64] |

| 40.4a | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 30 | Variable | Sri Lanka, wet zone | Munasinghe et al.[161] |

| 43.2a | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 30 | Variable | Sri Lanka, intermediate zone | Munasinghe et al. [161] |

| 65.1a | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 38 | 450 | China, Xishuangbanna | Yang et al. [162] |

| 41.7b | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 20 | 500 - 680 | Thailand, Nong Khai | Saengruksawong et al.[163] |

| 42.0c | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 20 | 500 | Indonesia, Sumatra | Sone et al. [164] |

| 38.2b | Aboveground biomass | 1 - 30 | No data | Indonesia | Lusiana [165] |

| 46.2b | Aboveground biomass | 1 - 30 | Jungle rubber | Indonesia | Palm et al. [166] |

| 23.0b | Above – and belowground biomass | 1 - 15 | 500 | Brazil, Parana | Maggioto et al. [70] |

| 52.7 | Soil, 0-60 cm depth | 14 | 433 | Ghana | Wauters et al. [65] |

| 105.6 | Soil, 0-60 cm depth | 14 | 469 | Brazil, Mato Grosso | Wauters et al. [65] |

| 79.3 | Soil, 0-60 cm depth | 15 | 460 | Brazil, Parana | Maggioto et al. |

| 72.0d | Soil, 0-40 cm depth | 15 | 375 | China, Hainan | Cheng et al. [64] |

| 147.2 | Soil, 0-100 cm depth | 19 | 450 | China, Xishuangbanna | Yang et al. [162] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).