Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

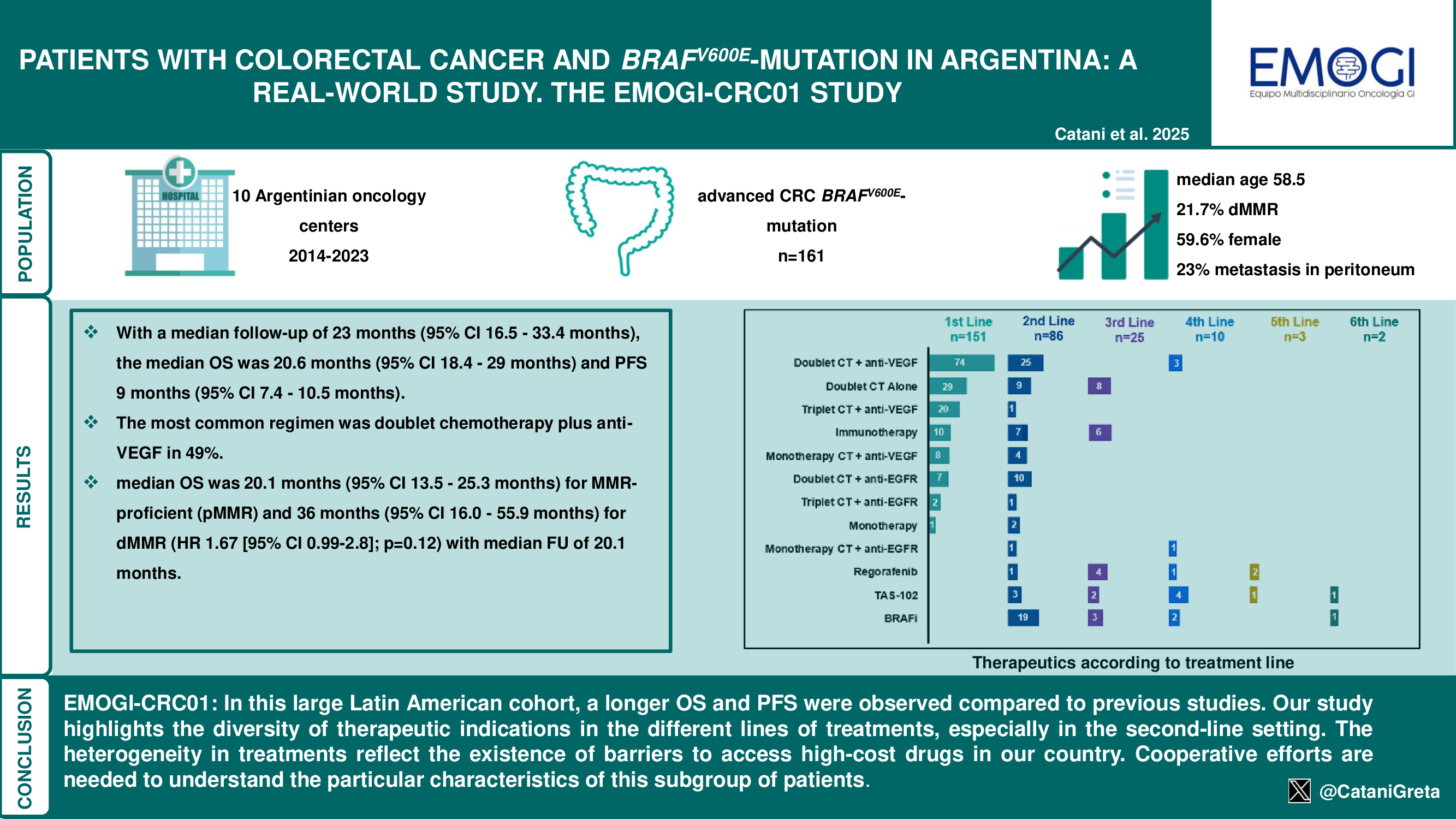

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Key Study Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analyses

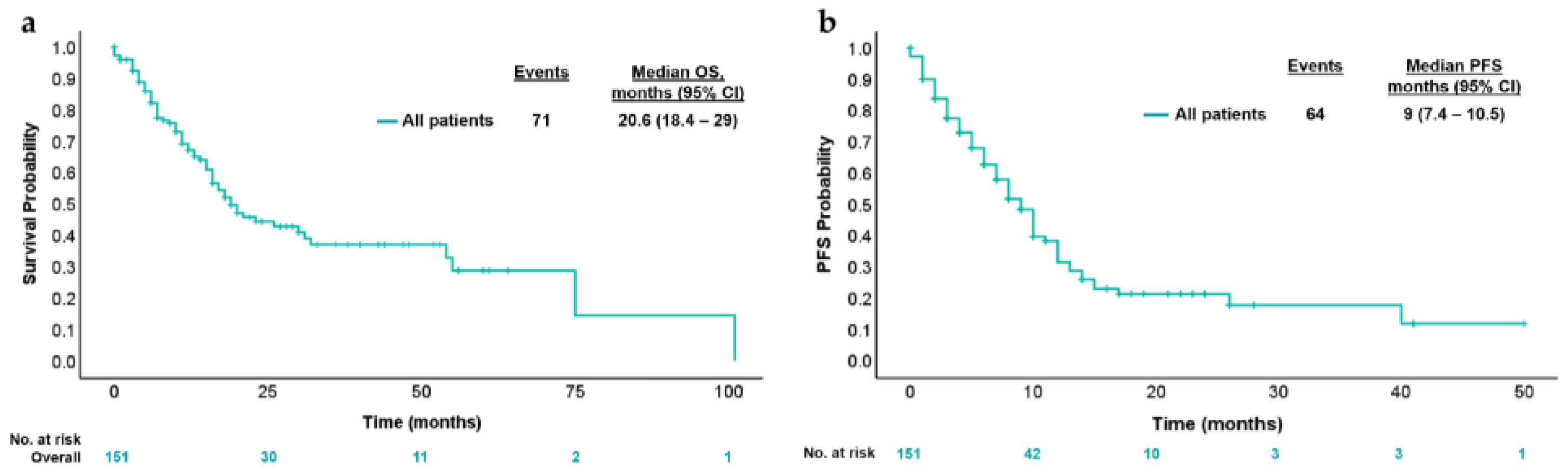

3. Results

3.1. Patient’s Characteristics

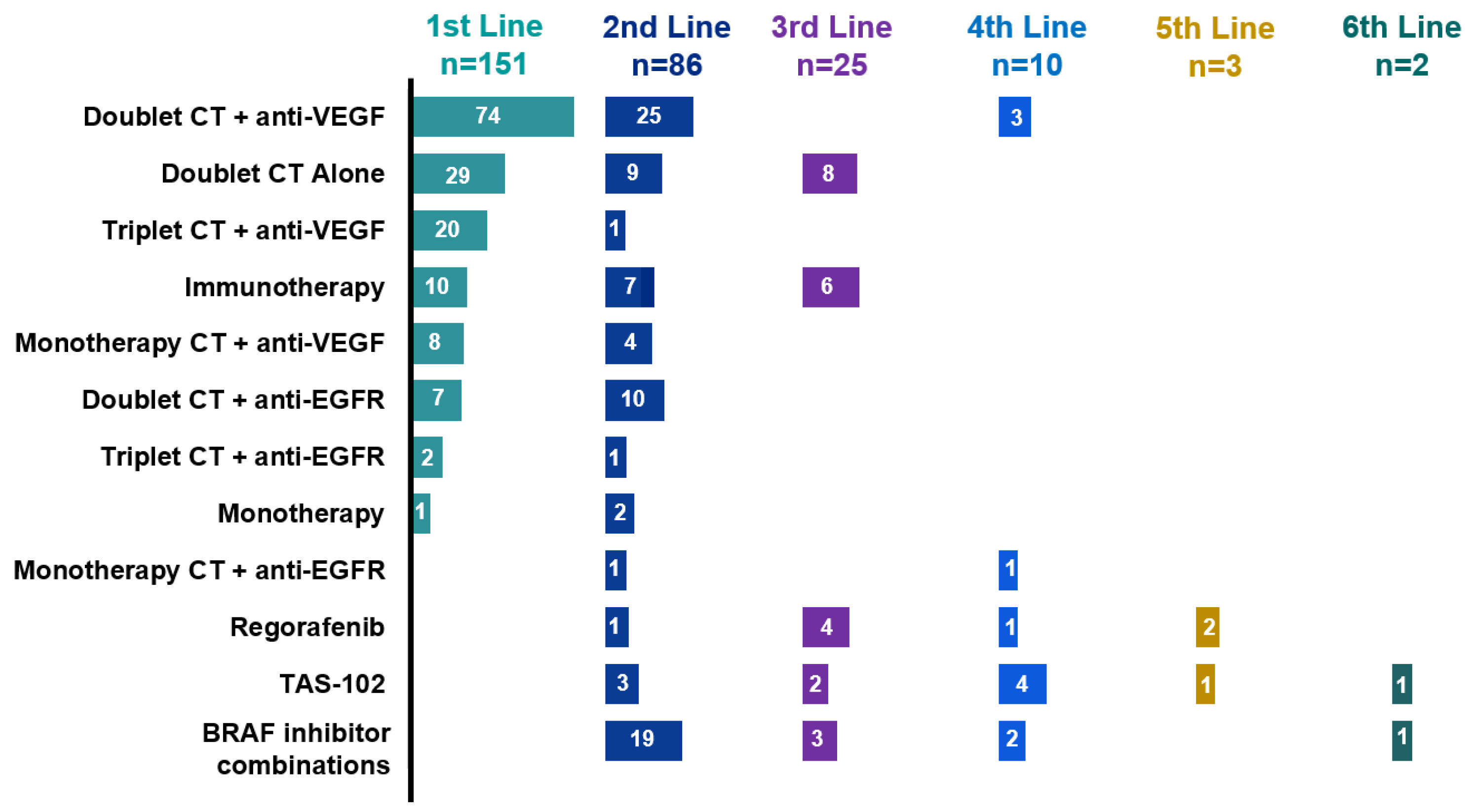

3.2. Treatment Sequences

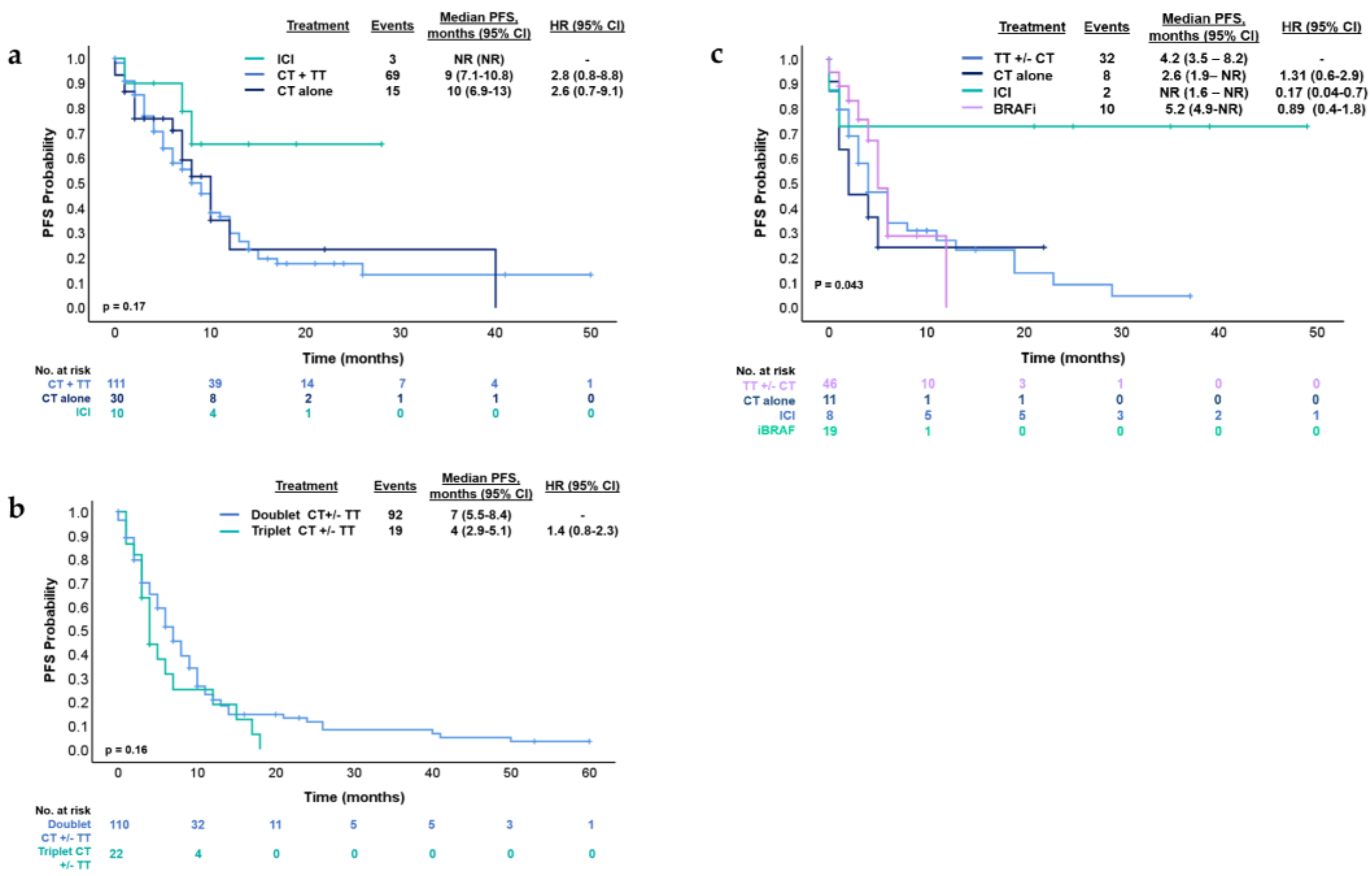

3.3. Treatment Strategies and Outcomes in First- and Second-Line Therapy

3.4. Immunotherapy and BRAF inhibitors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017;66(4):683-691. [CrossRef]

- Estadísticas - Incidencia. Argentina.gob.ar 2019. https://www.argentina.gob.ar/salud/instituto-nacional-del-cancer/estadisticas/incidencia (accessed November 26, 2024).

- Cancer of the Colon and Rectum - Cancer Stat Facts. SEER n.d. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html (accessed November 26, 2024).

- Cervantes A, Adam R, Roselló S, Arnold D, Normanno N, Taïeb J, Seligmann J, De Baere T, Osterlund P, Yoshino T, Martinelli E. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(1):10–32. [CrossRef]

- Morris VK, Kennedy EB, Baxter NN, Benson AB 3rd, Cercek A, Cho M, Ciombor KK, Cremolini C, Davis A, Deming DA, Fakih MG, Gholami S, Hong TS, Jaiyesimi I, Klute K, Lieu C, Sanoff H, Strickler JH, White S, Willis JA, Eng C. Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ASCO Guideline. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2023;41(3):678–700. [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda AR, Hamilton SR, Allegra CJ, Grody W, Cushman-Vokoun AM, Funkhouser WK, Kopetz SE, Lieu C, Lindor NM, Minsky BD, Monzon FA, Sargent DJ, Singh VM, Willis J, Clark J, Colasacco C, Rumble RB, Temple-Smolkin R, Ventura CB, Nowak JA. Molecular Biomarkers for the Evaluation of Colorectal Cancer: Guideline From the American Society for Clinical Pathology, College of American Pathologists, Association for Molecular Pathology, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(13):1453-1486. [CrossRef]

- Caputo F, Santini C, Bardasi C, Cerma K, Casadei-Gardini A, Spallanzani A, Andrikou K, Cascinu S, Gelsomino F. BRAF-Mutated Colorectal Cancer: Clinical and Molecular Insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(21):5369. [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012;487:330–7. [CrossRef]

- Tabernero J, Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Yaeger R, Wasan H, Yoshino T, Desai J, Ciardiello F, Loupakis F, Hong YS, Steeghs N, Guren TK, Arkenau HT, Garcia-Alfonso P, Elez E, Gollerkeri A, Maharry K, Christy-Bittel J, Kopetz S. Encorafenib Plus Cetuximab as a New Standard of Care for Previously Treated BRAF V600E-Mutant Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Updated Survival Results and Subgroup Analyses from the BEACON Study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(4):273-284. [CrossRef]

- Belló M, Becerril-Montekio V. The health system of Argentina. Salud Publica Mex 2011;53 suppl 2:S96-S108.

- Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol 1972;34:187–202. [CrossRef]

- Barras D, Missiaglia E, Wirapati P, Sieber OM, Jorissen RN, Love C, Molloy PL, Jones IT, McLaughlin S, Gibbs P, Guinney J, Simon IM, Roth AD, Bosman FT, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M. BRAF V600E Mutant Colorectal Cancer Subtypes Based on Gene Expression. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23(1):104-115. [CrossRef]

- Genetics and Epidemiology of Colorectal Cancer Consortium. Fred Hutch n.d. https://www.fredhutch.org/en/research/divisions/public-health-sciences-division/research/cancer-prevention/genetics-epidemiology-colorectal-cancer-consortium-gecco.html (accessed June 29, 2024).

- Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D, Dietrich D, Biesmans B, Bodoky G, Barone C, Aranda E, Nordlinger B, Cisar L, Labianca R, Cunningham D, Van Cutsem E, Bosman F. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer: results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):466-74. [CrossRef]

- Venderbosch S, Nagtegaal ID, Maughan TS, Smith CG, Cheadle JP, Fisher D, Kaplan R, Quirke P, Seymour MT, Richman SD, Meijer GA, Ylstra B, Heideman DA, de Haan AF, Punt CJ, Koopman M. Mismatch repair status and BRAF mutation status in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a pooled analysis of the CAIRO, CAIRO2, COIN, and FOCUS studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(20):5322-30. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli E, Cremolini C, Mazard T, Vidal J, Virchow I, Tougeron D, Cuyle PJ, Chibaudel B, Kim S, Ghanem I, Asselain B, Castagné C, Zkik A, Khan S, Arnold D. Real-world first-line treatment of patients with BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: the CAPSTAN CRC study. ESMO Open. 2022;7(6):100603. [CrossRef]

- Xu T, Li J, Wang Z, Zhang X, Zhou J, Lu Z, Shen L, Wang X. Real-world treatment and outcomes of patients with metastatic BRAF mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2023;12(9):10473-10484. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor J, Torrecillas-Torres L, Alvarado F, Colombero C, Sasse A. Biomarkers and treatment characteristics in metastatic colorectal cancer RASwt patients in Latin America. Gac Mex Oncol. 2023;22:10022. [CrossRef]

- Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, Lonardi S, Masi G, Salvatore L, Cortesi E, Tomasello G, Spadi R, Zaniboni A, Tonini G, Barone C, Vitello S, Longarini R, Bonetti A, D'Amico M, Di Donato S, Granetto C, Boni L, Falcone A. Early tumor shrinkage and depth of response predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: results from phase III TRIBE trial by the Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(6):1188-1194. [CrossRef]

- Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, Lupi C, Sensi E, Lonardi S, Mezi S, Tomasello G, Ronzoni M, Zaniboni A, Tonini G, Carlomagno C, Allegrini G, Chiara S, D'Amico M, Granetto C, Cazzaniga M, Boni L, Fontanini G, Falcone A. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1306-15. [CrossRef]

- Ros J, Baraibar I, Sardo E, Mulet N, Salvà F, Argilés G, Martini G, Ciardiello D, Cuadra JL, Tabernero J, Élez E. BRAF, MEK and EGFR inhibition as treatment strategies in BRAF V600E metastatic colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:1758835921992974. [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem E, Lang I, Folprecht G, Nowacki M, Barone C, Shchepotin I, et al. Cetuximab plus FOLFIRI: Final data from the CRYSTAL study on the association of KRAS and BRAF biomarker status with treatment outcome. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3570–3570. [CrossRef]

- Stintzing S, Miller-Phillips L, Modest DP, Fischer von Weikersthal L, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, Al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Kahl C, Seipelt G, Kullmann F, Stauch M, Scheithauer W, Held S, Moehler M, Jagenburg A, Kirchner T, Jung A, Heinemann V; FIRE-3 Investigators. Impact of BRAF and RAS mutations on first-line efficacy of FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab: analysis of the FIRE-3 (AIO KRK-0306) study. Eur J Cancer. 2017;79:50-60. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli E, Arnold D, Cervantes A, Stintzing S, Van Cutsem E, Tabernero J, Taieb J, Wasan H, Ciardiello F. European expert panel consensus on the clinical management of BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023;115:102541. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto RD, Chakhtoura JJA, Aguilar-Ponce JL, Garcia-Rivello H, Jansen AM, Parra Medina R, Ramos-Esquivel A, Stefani SD. BRAF Testing in Melanoma and Colorectal Cancer in Latin America: Challenges and Opportunities. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31972. [CrossRef]

- Loupakis F, Intini R, Cremolini C, Orlandi A, Sartore-Bianchi A, Pietrantonio F, Pella N, Spallanzani A, Dell'Aquila E, Scartozzi M, De Luca E, Rimassa L, Formica V, Leone F, Calvetti L, Aprile G, Antonuzzo L, Urbano F, Prenen H, Negri F, Di Donato S, Buonandi P, Tomasello G, Avallone A, Zustovich F, Moretto R, Antoniotti C, Salvatore L, Calegari MA, Siena S, Morano F, Ongaro E, Cascinu S, Santini D, Ziranu P, Schirripa M, Buggin F, Prete AA, Depetris I, Biason P, Lonardi S, Zagonel V, Fassan M, Di Maio M. A validated prognostic classifier for V600EBRAF-mutated metastatic colorectal cancer: the 'BRAF BeCool' study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;118:121-130. [CrossRef]

- Ros J, Rodríguez-Castells M, Saoudi N, Baraibar I, Salva F, Tabernero J, Élez E. Treatment of BRAF-V600E mutant metastatic colorectal cancer: new insights and biomarkers. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2023;23(8):797-806. [CrossRef]

- Bottos A, Martini M, Di Nicolantonio F, Comunanza V, Maione F, Minassi A, Appendino G, Bussolino F, Bardelli A. Targeting oncogenic serine/threonine-protein kinase BRAF in cancer cells inhibits angiogenesis and abrogates hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(6):E353-9. [CrossRef]

- Quintanilha JCF, Graf RP, Oxnard GR. BRAF V600E and RNF43 Co-mutations Predict Patient Outcomes With Targeted Therapies in Real-World Cases of Colorectal Cancer. Oncologist. 2023;28(3):e171-e174. [CrossRef]

- Elez E, Ros J, Fernández J, Villacampa G, Moreno-Cárdenas AB, Arenillas C, Bernatowicz K, Comas R, Li S, Kodack DP, Fasani R, Garcia A, Gonzalo-Ruiz J, Piris-Gimenez A, Nuciforo P, Kerr G, Intini R, Montagna A, Germani MM, Randon G, Vivancos A, Smits R, Graus D, Perez-Lopez R, Cremolini C, Lonardi S, Pietrantonio F, Dienstmann R, Tabernero J, Toledo RA. RNF43 mutations predict response to anti-BRAF/EGFR combinatory therapies in BRAFV600E metastatic colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2022;28(10):2162-2170. [CrossRef]

- Ros J, Matito J, Villacampa G, Comas R, Garcia A, Martini G, Baraibar I, Saoudi N, Salvà F, Martin Á, Antista M, Toledo R, Martinelli E, Pietrantonio F, Boccaccino A, Cremolini C, Dientsmann R, Tabernero J, Vivancos A, Elez E. Plasmatic BRAF-V600E allele fraction as a prognostic factor in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with BRAF combinatorial treatments. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(6):543-552. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total=161 n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age, years | 58.3 (47-69) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 96 | 59.6% |

| Male | 65 | 40.4% |

| ECOG* | ||

| 0-1 | 135 | 85.7 |

| ≥2 | 23 | 14.3 |

| Tumor location | ||

| Left | 114 | 70.8% |

| Right | 33 | 20.5% |

| Rectum | 14 | 8.7 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||

| I | 1 | 0.6% |

| II | 12 | 7.5% |

| III | 33 | 20.5% |

| IV | 115 | 71.4% |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 112 | 69.5 |

| Mucinous | 43 | 26.8 |

| Unknown | 6 | 3.7 |

| Number of metastasis site | ||

| One | 69 | 42.8 |

| Two or more | 78 | 48.5 |

| Unknown | 14 | 8.7 |

| Site of metastasis | ||

| Liver | 90 | 55.9% |

| Nodes | 82 | 50.9% |

| Lung | 19 | 11.8% |

| Peritoneum | 37 | 23% |

| Type of testing | ||

| Primary tumor | 144 | 89.5 |

| Metastasis | 8 | 4.9 |

| Liquid biopsy | 9 | 5.6 |

| Status MMR** | ||

| MMR-deficient | 35 | 21.7% |

| MMR-proficient | 711 | 72.7% |

| Unknown | 9 | 5.6% |

| Status RAS | ||

| Mutated | 3 | 1.2% |

| Wild-type | 134 | 83.8% |

| Unknown | 24 | 15% |

| Lines of treatment received | ||

| First | 151 | 93.8% |

| Second | 86 | 53.4% |

| Third | 25 | 15.5% |

| Forth | 10 | 6.2% |

| Fifth | 3 | 1.8% |

| Sixth | 2 | 1.2% |

| Variable | Progression or death | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n=87 (%) |

No n=64 (%) |

HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|

Age at diagnosis ≤50 years 50-70 years >70 years |

27 (62.8) 44 (56.4) 16 (53.4) |

16 (37.2) 34 (43-6) 14 (46.6) |

- 0.71 (0.44-1.16) 0.58 (0.31-1.08) |

0.18 0.08 |

- 0.76 (0.45-1.27) 0.74 (0.37-1.43 |

0.29 0.36 |

|

Gender Female Male |

49 (55) 38 (61.3) |

40 (45) 24 (38.7) |

- 1.57 (1.01-2.4) |

0.04 |

- 1.55 (0.98-2.45) |

0.06 |

|

Stage at diagnosis I II III IV |

1 (100) 7 (58.3) 18 (54.5) 61 (58.1) |

- 5 (41.7) 15 (45.5) 44 (41.9) |

- 0.15 (0.01-0.99) 0.12 (0.01-0.72) 0.14 (0.01-0.86) |

0.08 0.04 0.05 |

/ |

/ |

|

Tumor location Left Right Rectum |

61 (57.5) 14 (45.2) 12 (85.7) |

45 (42.5) 17 (54.8) 2 (14.3) |

- 1.12 (0.62-2.01) 2.1 (1.12-3.9) |

0.71 0.01 |

- 0.96 (0.53-1.77) 1.67 (0.37-3.3) |

0.09 0.14 |

|

Histology Adenocarcinoma Mucinous |

60 (54.6) 23 (65.7) |

50 (45.4) 12 (34.3) |

- 0.76 (0.26-2.22) |

0.61 |

/ |

/ |

|

Diagnosis of the metastatic setting Synchronous Metachronous |

66 (62.3) 21 (46.7) |

40 (37.7) 24 (53.3) |

0.94 (0.13-8.87) 0.65 (0.09-4.84) |

0.96 0.67 |

/ |

/ |

|

Liver metastasis No Yes |

34 (50.7) 53 (63.1) |

33 (49.3) 31 (36.9) |

- 1.18 (0.77-2.72) |

- 0.45 |

/ |

/ |

|

Peritoneum metastasis No Yes |

65 (55.1) 20 (64.5) |

53 (44.9) 11 (35.5) |

- 1.64 (0.99-2.72) |

- 0.05 |

1.92 (1.12-3.28) |

0.01 |

|

MMR status pMMR dMMR |

72 (60.5) 15 (46.9) |

47 (39.5) 17 (53.1) |

- 0.65 (0.38-1.16) |

- 0.15 |

/ |

/ |

|

Surgery primary tumor No Yes |

72 (60.5) 15 (46.9) |

46 (45.5) 18 (36) |

1.8 (1.15-2.8) - |

0.009 |

1.79 (1.11-2.88) |

0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).