Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

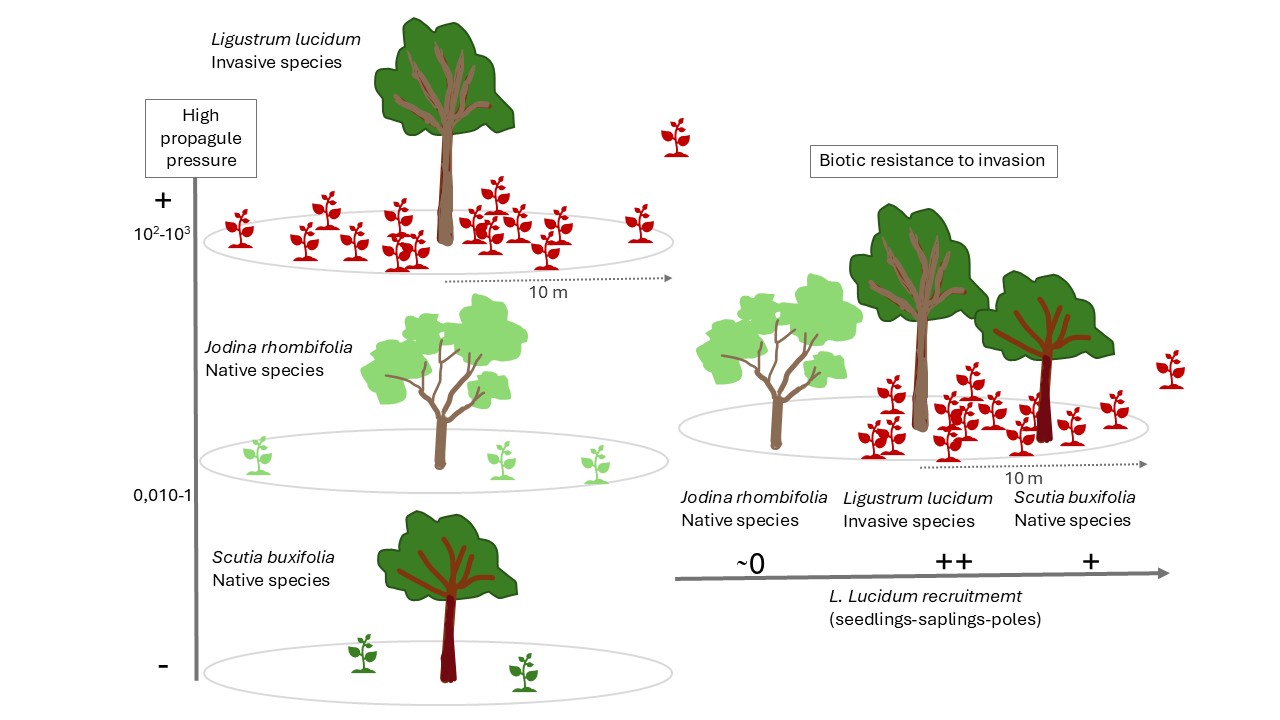

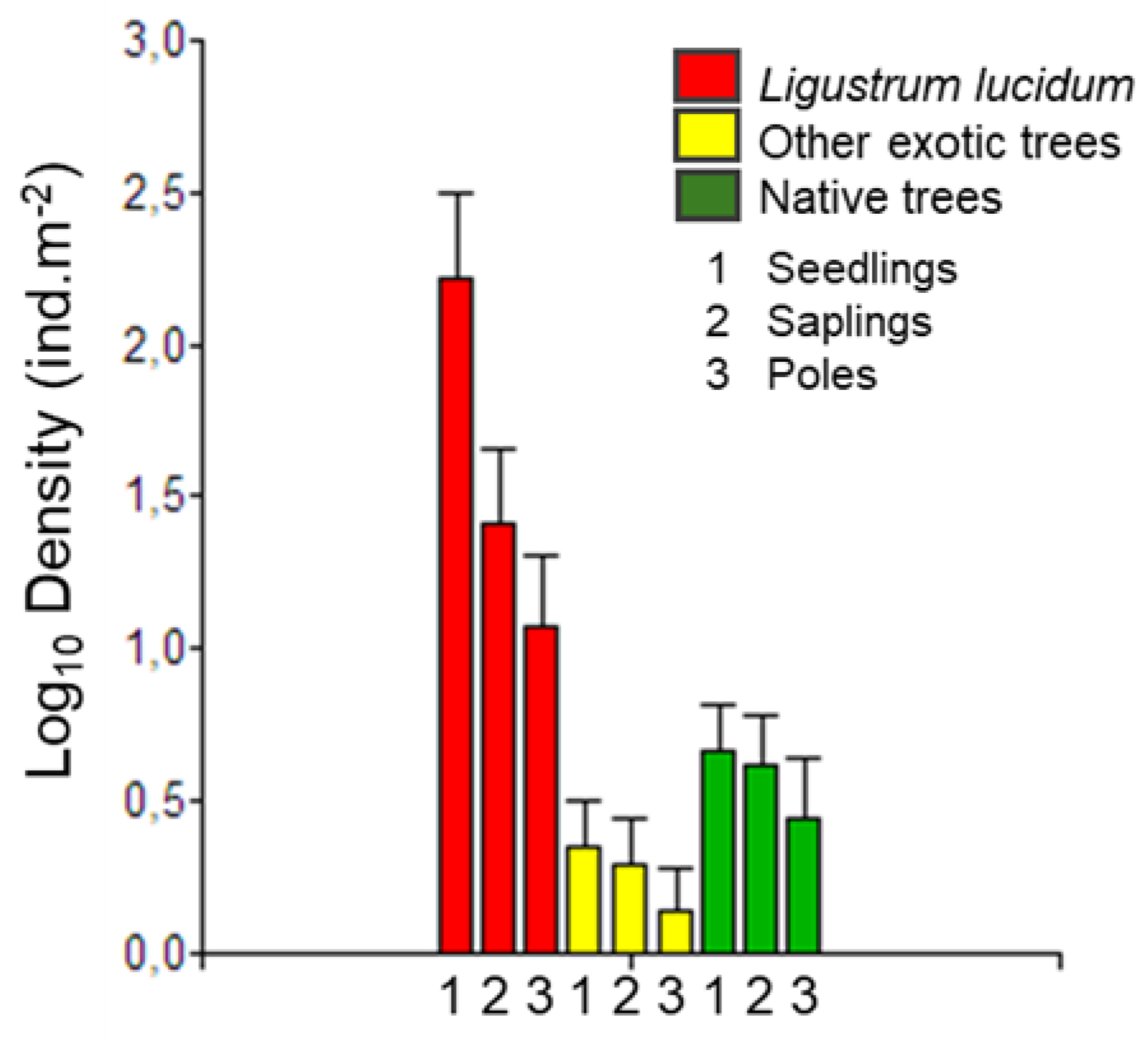

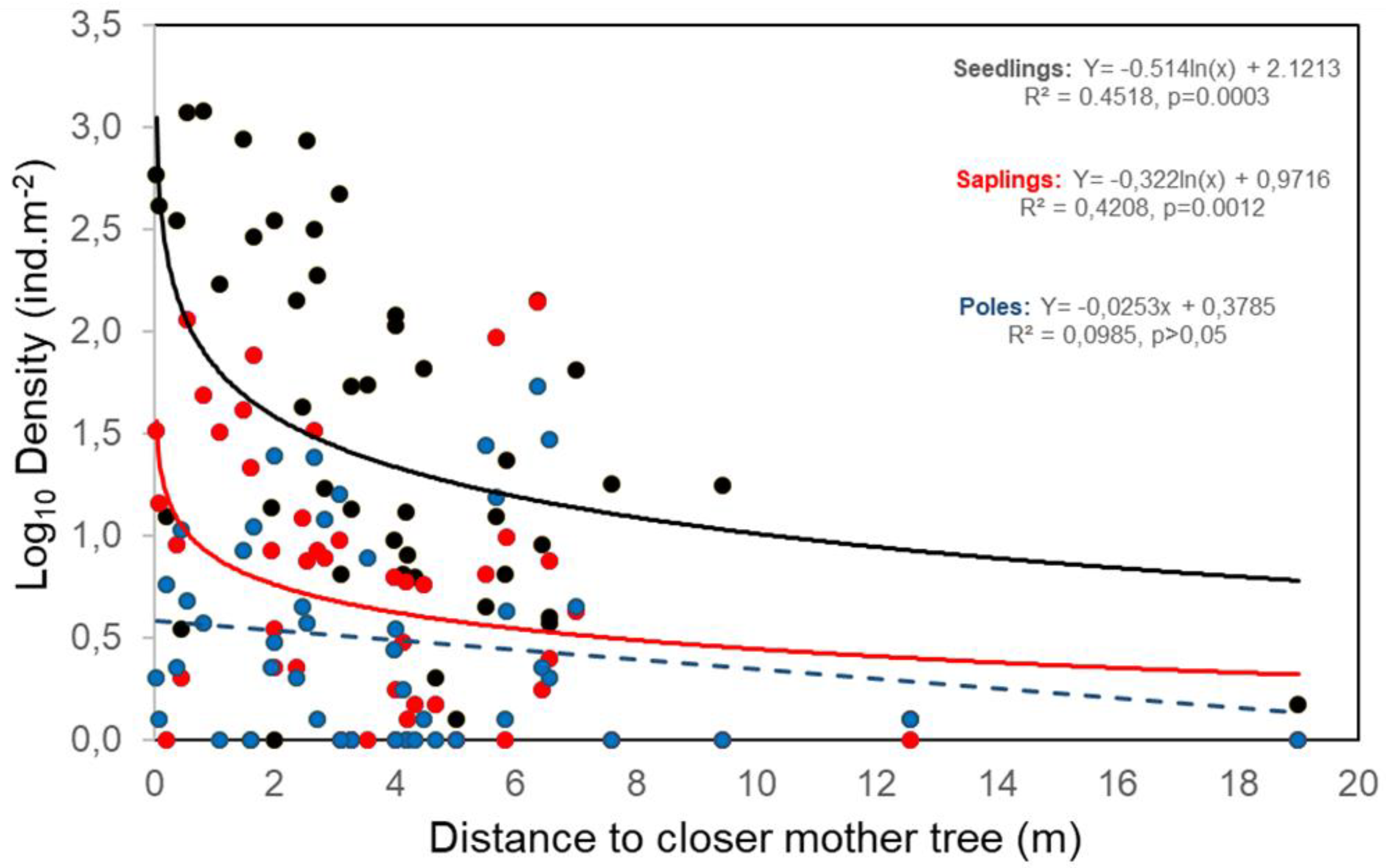

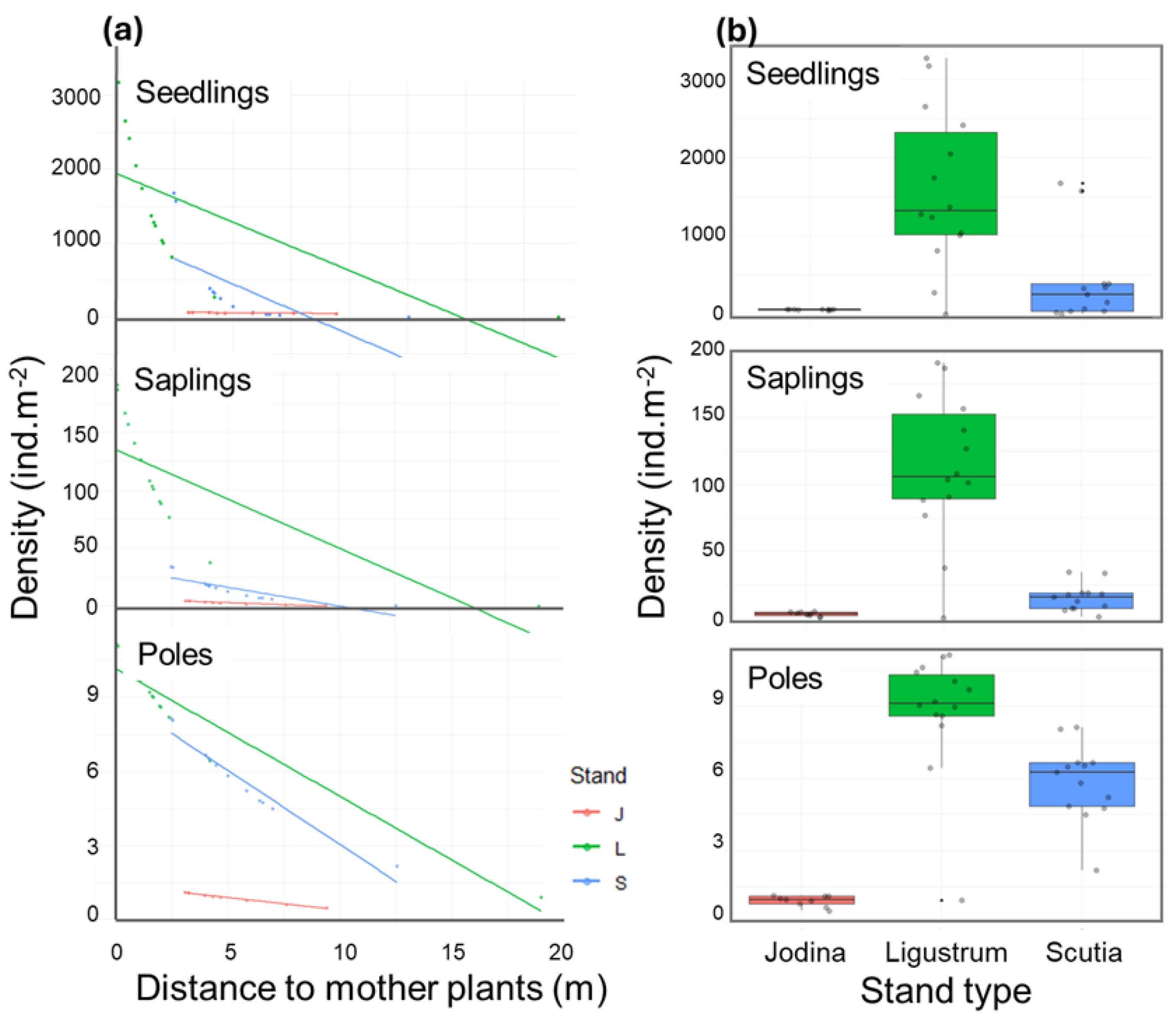

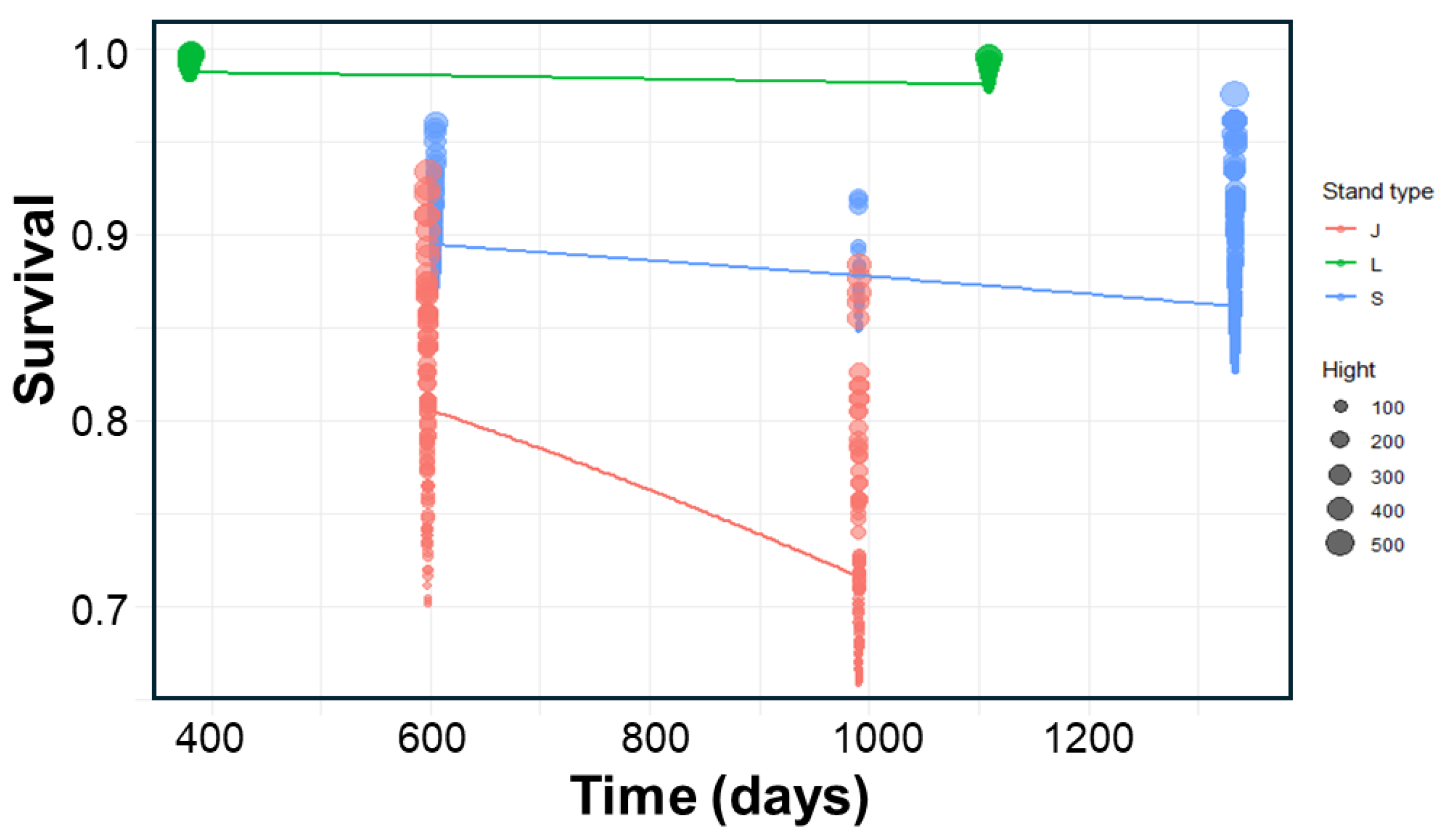

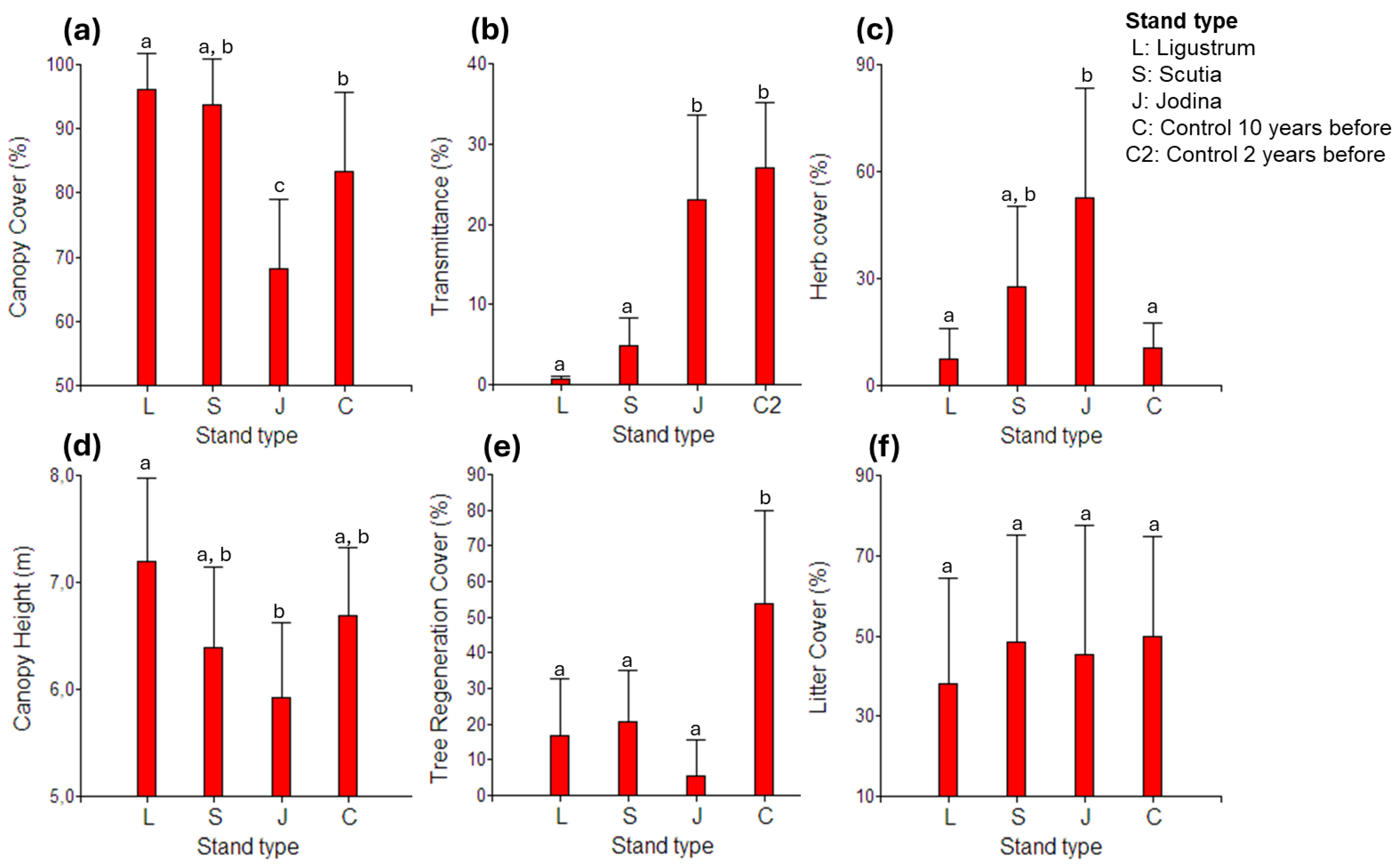

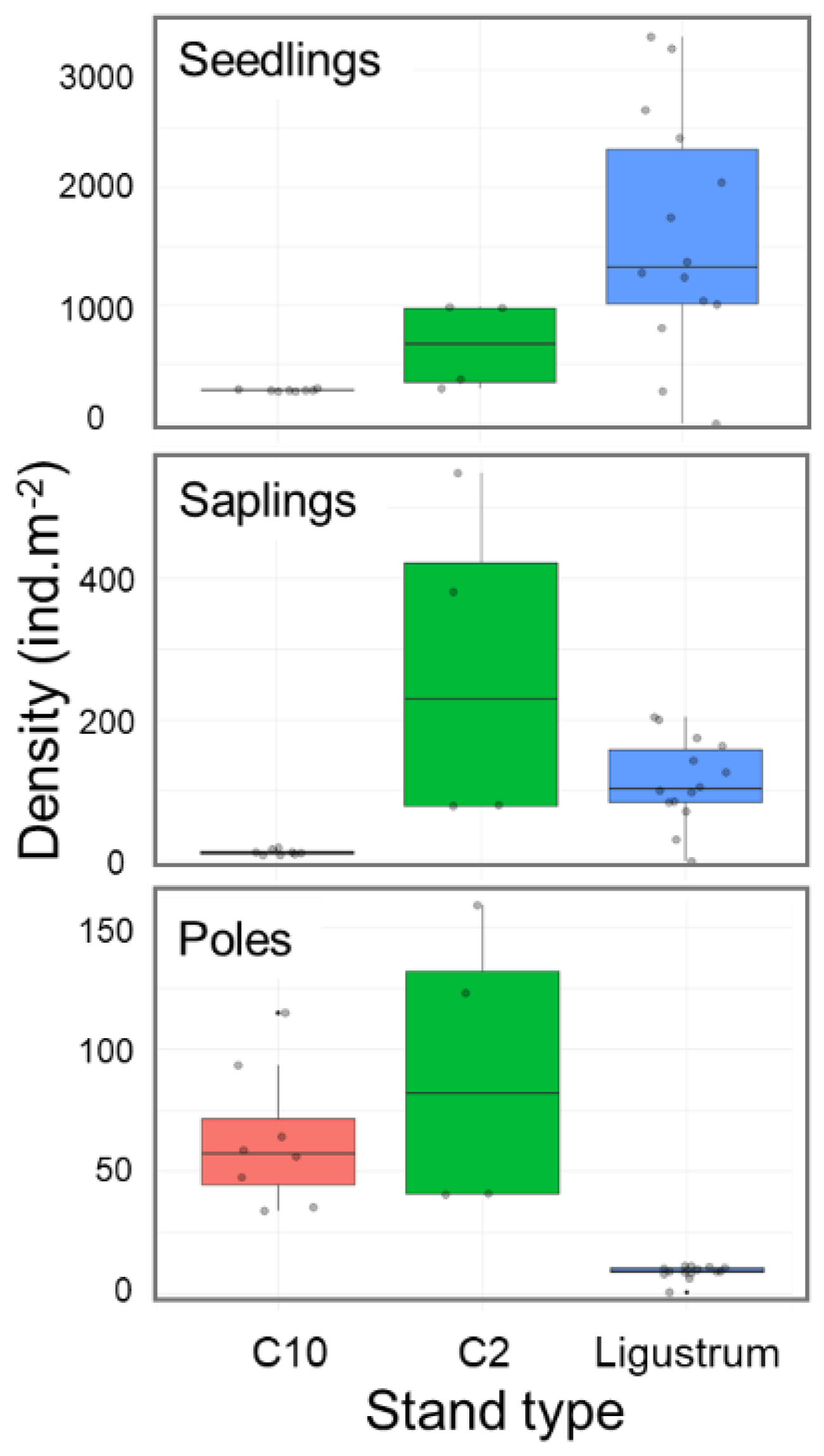

The tree Ligustrum lucidum (W. T. Aiton, Oleaceae), native to East Asia (China), has become an aggressive invader of subtropical and temperate forests around the world. To understand how its local small-scale spread is controlled, we studied in a subtropical forest of Uruguay the distribution of seedlings, saplings and poles in relation to distance to mother trees and forest stand (48 plots of 4 m-2). The propagule pressure of L. lucidum, estimated through seedlings density, was between 100 and 1000 times higher than that of other species of the community and was concentrated around mother trees (<10m). Spatial variability of seedlings, saplings and poles densities were explained by the interaction between distance to mother trees and forest stand. Significative lower densities were observed in stands dominated by Jodina rhombifolia, and a field survival experiment confirmed lower survival of poles at Jodina stands, demonstrating that some resistance mechanism is operating there. We propose two biotic mechanisms of resistance: herbaceous competition and roots hemiparasitism by J. rhombifolia. We concluded that a high propagule pressure, small-scale dispersal from mother trees and patchy biotic resistance at Jodina stands control the local spread and domination process of the tree L. lucidum in the studied forest.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Regenerating Species Assemblage and L. lucidum Propagule Pressure

2.2. Exploring Determinant of L. lucidum Recruitment

2.3. Survival Experiment: Assessing Stand Type Effects

2.4. Possible Underlying Factors Behind Stand Type Effects

2.5. Effects of Previous Control Activities on Current Recruitmet of L. lucidum

3. Discussion

3.1. High Propagule Pressure of L. lucidum

3.2. Small-Scale Dispersal from Parental Trees

3.3. Biotic Resistance in Jodina´s Stands to L. lucidum Invasion

3.4. Isolated Control of Adult Trees Is Not Sufficient to Restore Forests Invaded by L. lucidum

4. Materials and Methods

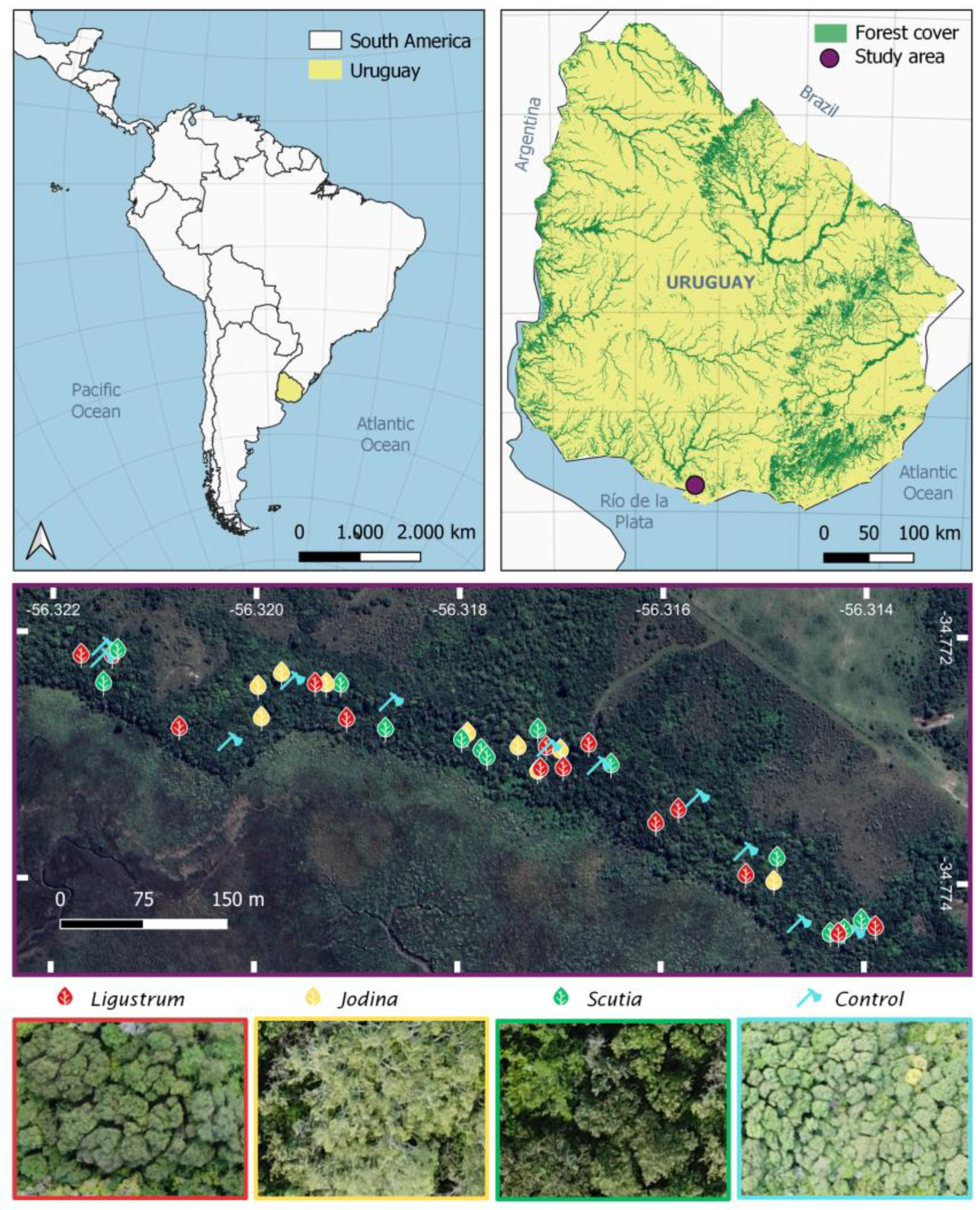

4.1. Study Area

4.2. Field Sampling

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| GLM | General Linear Model |

| INUMET | Instituto Nacional de Meteorología de Uruguay |

| LSD | Least Significant Difference |

| PAR | Photosynthetically Active Range |

References

- Vitousek, P.N.; D’ Antonio, C.M.; Loope, L.L.; Westbrook, R. Biological invasions as global environmental change. Am. Sci. 1996, 84: 468-478.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Island Press, Washington, DC., USA, 2005; https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.356.aspx.pdf. Accessed 25 Sep 2023.

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D. et al. Scientists’ warning on invasive alien species. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95(6):1511-1534. [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.E.; Pauchard, A.; Stoett, P.; Renard Truong, T.; Bacher, S.; Galil, B.S.; Hulme, P.E.; Ikeda, T.; Sankaran, K.; McGeoch, M.A.; et al. IPBES Invasive Alien Species Assessment: Summary for Policymakers; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, R.; Ceballos, C.; Aragón, R.; Malizia, A.; Montti, L.; Whitworth-Hulse, J.; Castro-Diez, P.; Grau, H.R. A global review of the invasion of glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum, Oleaceae). Bot. Rev. 2020, 86: 93-118. [CrossRef]

- Montti, L.; Velazco, S.J.; Travis, J.M.; Grau, H.R. Predicting current and future global distribution of invasive Ligustrum lucidum W.T. Aiton: Assessing emerging risks to biodiversity hotspots. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27:1568-1583. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, J.B.B.; Higuchi, P.; Silva, A.C. Ligustrum lucidum W. T. Aiton (broad-leaf privet) demonstrates climatic niche shifts during global-scale invasion. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9: 3813. [CrossRef]

- Zamora Nasca, L.; Montti, L.; Grau, R.; Paolini, L. Efectos de la invasión del ligustro, Ligustrum lucidum, en la dinámica hídrica de las Yungas del noroeste argentino. Bosque (Valdivia) 2014, 35(2): 195-205. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002014000200007.

- Aguirre-Acosta, N; Kowaljow, E.; Aguilar, R. Reproductive performance of the invasive tree Ligustrum lucidum in a subtropical dry forest: does habitat fragmentation boost or limit invasion? Biol. Invasions. 2014, 16:1397–1410. [CrossRef]

- Aragón, R.; Groom, M. Invasion by Ligustrum lucidum (Oleaceae) in NW Argentina: early-stage characteristics in different habitat types. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2003, 51(1): 59-70.

- Montaldo, N. Éxito reproductivo de plantas ornitócoras en un relicto de selva subtropical en Argentina. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2000, 73: 511-524. [CrossRef]

- Grau, H.R.; Aragón, R. Ecología de los árboles invasores de la Sierra de San Javier. In: Grau, H.R.; Aragón, R. (eds.). Árboles exóticos de las Yungas Argentinas. LIEY-UNT, Tucumán, Argentina, 2000, pp 5- 20.

- Hoyos, L.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.; Kuemmerle, T.; Bucher, E.; Radeloff, V.; Tecco, T. Invasion of glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum) and native forest loss in the Sierras Chicas of Córdoba, Argentina. Biol. Invasions. 2010, 12: 3261-3275. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, S.J.; Malizia, A.; Chacoff, N. Influencia de la invasión de Ligustrum lucidum (Oleaceae) sobre la comunidad de lianas en la sierra de San Javier (Tucumán–Argentina). Ecol. Austral. 2015, 25: 65–74. [CrossRef]

- Malizia, A.; Osinaga-Acosta, O.; Powell, P.; Aragón, R. Invasion of Ligustrum lucidum (Oleaceae) in subtropical secondary forests of NW Argentina: declining growth rates of abundant native tree species. J. Veg. Sci. 2017, 28(6): 1097-1269. [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.G.; Plaza, M.C.; Medina, M.; Pérez, C.; Mundo, I.A.; Cellini, J.M.; Arturi, M.F. Talares del NE bonaerense con presencia de Ligustrum lucidum: Cambios en la estructura y la dinámica del bosque. Ecol. Austral. 2018, 28: 502-512. [CrossRef]

- Bellis, L.M.; Astudillo, A.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.; Dardanelli, S.; Landi, M.; Hoyos, L. Glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum) invasion decreases Chaco Serrano Forest bird diversity but favors its seed dispersers. Biol. Invasions. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Whitworth-Hulse, J.I.; Magliano, P.N.; Zeballos, S.R.; Nosetto, M.D.; Gurvich, D.E.; Ferreras, A.; Spalazzi, F.; Kowaljow, E. Ligustrum lucidum invasion alters the soil water dynamic in a seasonally multispecific dry forest. Forest. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 549, 121493. [CrossRef]

- Brazeiro, A.; Olivera, J.; Betancourt, A.; Lado, I.; Romero, D.; Haretche, F.; Cravino, A. Disentangling the invasion process of subtropical native forests of Uruguay by the exotic tree Ligustrum lucidum: establishment and dominance determinants. Ecol. Proc. 2024, 13:49. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M. Frugivory, seed dispersal and plant community ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15: 487-488. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M. Biological Invasions. Chapman & Hall, New York.1996.

- Lockwood, J.L.; Hoopes, M.F.; Marchetti, M.P. Invasion ecology. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2007.

- Davis, M.A. Invasion Biology. Oxford University Press, New York, 2009.

- Martin, P.H.; Canham, C.D. Dispersal and recruitment limitation in native versus exotic tree species: life-history strategies and Janzen-Connell effects. Oikos 2010, 119:807–824. [CrossRef]

- Lamarque L.J.; Delzon, S.; Lortie, C.J. Tree invasions: a comparative test of the dominant hypotheses and functional traits. Biol Invasions, 2011. 13:1969–1989. [CrossRef]

- Colautti, R.I.; Grigorovich, I.A.; MacIsaac, H.J. Propagule pressure: a null model for biological invasions. Biol Invasions 2006, 8:1023–1037. [CrossRef]

- Diaz Villa, M.V.E.; Madane, N.; Cristiano, P.M.; Goldstein, G. Composición del banco de semillas e invasión de Ligustrum lucidum en bosques costeros de la provincia de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Bosque 2016, 37(3): 581–590. [CrossRef]

- Emer, A.A.; Oliveira, M.de.A.; Althaus-Ottmann, M.M. Biochemical composition and germination capacity of Ligustrum lucidum ait. seeds in the process of biological invasion. Acta Scient. Biol. Sci. 2012, 34(3): 353-357. [CrossRef]

- Powell, A.A.; Araóz, E. Biological and environmental effects on fine-scale seed dispersal of an invasive tree in a secondary subtropical forest. Biol Invasions. 2017, 20: 461–473. [CrossRef]

- Marco, E.M.; Montemurro, M.A.; Cannas, S.A. Comparing short and long-distance dispersal: modelling and field case studies. Ecography 2011, 34: 671-682. [CrossRef]

- Mazia, C.N., Chaneton, E.J.; Ghersa, C.M.; León, R.J.C. Limits to tree species invasion in pampean grassland and forest plant communities. Oecologia 2001, 128:594-602. [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.L.; Giudice, G.E. Anatomy of the haustorium of Jodina rhombifolia (Santalaceae). Nordic J. Bot. 2005, 24: 567-573. [CrossRef]

- Matthies, D. Interactions between a root hemiparasite and 27 different hosts: growth, biomass allocation and plant architecture. Persp. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 24: 118–37. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, D.D.; Seel, W.E. Functional anatomy of haustoria formed by Rhinanthus minor: Linking evidence from histology and isotope tracing. The New Phytologist 2007, 174(2): 412–419. [CrossRef]

- Těšitelová, T.; Knotková, K.; Knotek, A.; Cempírková, H.; Těšitel, K. (2024). Root hemiparasites suppress invasive alien clonal plants: evidence from a cultivation experiment. NeoBiota 2024, 90: 97–121. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Uruguayo de Meteorología (INUMET). Climatología estacional. Available online: https://www.inumet.gub.uy/clima/climatologia-estacional (Accessed 25 Sep 2023).

- Alonso-Paz, E. Descripción de un monte natural en la zona de Melilla, Montevideo, Rep. O. del Uruguay. Discusión de algunos aspectos fitogeográficos. 60-61 p. In: Resúmenes, Comunicaciones III Jornadas de Ciencias Naturales, Montevideo, 19-24 of September, 1983.

- Medina, S; Rachid, C. Estudio de una sucesión vegetal en las Barrancas de los Humedales del Río Santa Lucía. Thesis Agronomic Engineer. Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay, 101 p. 2004.

| Density (ind.m-2) (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Seedlings | Saplings | Poles | |

| Exotic species | |||

| Ligustrum lucidum W.T.Aiton | 253.7 (621.4) | 15.5 (30.3) | 5.6 (10.2) |

| Ligustrum sinense Lour. | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.05 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.10) |

| Laurus nobilis L. | 0.03 (0.1) | 0.23(0.5) | 0.06(0.2) |

| Cotoneaster sp. | 0 | 0.01 (0.1) | 0.02 (0.1) |

| Pyracantha coccinea M.Roem | 0 | 0.01(0.0) | 0.01(0.0) |

| Phoenix canariensis H.Wildpret | 0 | 0.01(0.0) | 0 |

| Morus alba P. | 0 | 0 | 0.01(0.0) |

| Pittosporum undulatum Vent. | 0 | 0.06(0.4) | 0.01(0.0) |

| Native species | |||

| Blepharocalyx salicifolius (Kunth) O.Berg | 1.07(1.47) | 1.52(2.10) | 0.44(1.62) |

| Myrsine laetevirens Mez | 0.08(0.36) | 0.02(0.08) | 0.01(0.04) |

| Jodina rhombifolia (Hook. & Arn.) Reissek | 0.07(0.26) | 0.02(0.08) | 0.01(0.05) |

| Scutia buxifolia Reissek | 0.04(0.09) | 0.01(0.05) | 0.04(0.15) |

| Celtis tala Gillies ex Planch. | 0.04(0.15) | 0.01(0.04) | 0.01(0.05) |

| Acca sellowiana (O. Berg) Burret | 0 | 0.03(0.18) | 0.01(0.04) |

| Eugenia uniflora L. | 0 | 0.01(0.04) | 0.01(0.04) |

| Schinus longifolia (Lindl.) Speg. | 0 | 0.01(0.05) | 0 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seedlings | |||||

| (Intercept) | 4.21835 | 0.11929 | 35.36 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Distance | -0.04003 | 0.02262 | -1.77 | 0.0768 | . |

| Stand-L | 3.89434 | 0.11970 | 32.53 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Stand-S | 5.56176 | 0.12813 | 43.41 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Distance-Stand-L | -0.55919 | 0.02410 | -23.21 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Distance-Stand-S | -0.91487 | 0.02656 | -34.45 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Saplings | |||||

| (Intercept) | 2.7507 | 0.222 | 12.381 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Distance | -0.3899 | 0.0242 | -16.109 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Stand-L | 2.5125 | 0.2140 | 11.738 | <2e-16 | *** |

| Stand-S | 1.7401 | 0.2122 | 8.199 | 2.43e-16 | *** |

| Poles | |||||

| (Intercept) | 0.518 | 0.3923 | 1.307 | 0.1912 | |

| Distance | -0.1314 | 0.0372 | -3.532 | 0.0004 | *** |

| Stand-L | 1.9012 | 0.3836 | 4.957 | 7.17e-7 | *** |

| Stand-S | 1.9071 | 0.3717 | 5.131 | 2.89e-7 | *** |

| Estimate | Std. Error | z value | Pr(>|z|) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.9009358 | 0.4556859 | 1.977 | 0.04803 | * |

| Stand-L | 3.1828581 | 0.4531533 | 7.024 | 2.16e-12 | *** |

| Stand-S | 1.0696586 | 0.2555241 | 4.186 | 2.84e-05 | *** |

| Height | 0.0047637 | 0.0017515 | 2.720 | 0.00653 | ** |

| Time | -0.0004883 | 0.0004007 | -1.219 | 0.22299 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).