1. Introduction

Organogels are fascinating systems as they form three-dimensional networks from solutions containing a low percentage of relatively small-sized molecules designated as organogelators or low-molecular weight gelators (LMWG) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. In a recent monograph these molecules have been regarded as “chimeras” due to the fact they bear simultaneously different kind of interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, van der waals, and the like [

5]. Due to this unusual chemical architecture their crystallization habit favours one specific growth face, which results in the making of very long fibrillar entities that are more or less connected so as to produce an infinite network.

The knowledge of their molecular structure is a topical issue [

5,

6,

7,

8]. One specific point raised quite recently concerns the formation of

molecular compounds, that is the co-crystallization of the organogelator and the solvent [

5,

6].

Molecular compound is the generic terminology for systems that combine two or more molecules under a well-defined stoichiometry whatever the way they interact. This term is customary in the nomenclature used in temperature-concentration phase diagrams [

17]. In practice, several names can designate these systems depending on the type of interactions:

crystallo-solvates,

molecular complexes,

inclusion compounds,

intercalates, guest-host compounds, and the like [

17,

18,

19]. Systems form through hydrogen bonds are rather designated as

molecular complexes, a situation that will be encountered in this paper.

Several authors have already suspected from circumstantial evidence that the solvent is not only a simple diluent but plays a role in the gelation process [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The existence of molecular compounds has only been recently demonstrated by means of neutron diffraction while investigating the gelation of triaryl trisamide molecules with a series of organic solvents [

24,

25]. It has been further shown that the occurrence of molecular compounds has a direct bearing on the gel properties [

26,

27]. Neutron diffraction by making use of the isotopic contrast brought about by using either hydrogenous or deuterated species can unambiguously demonstrate the occurrence of molecular compounds [

25].

Based on circumstantial evidence, we had already conjectured in previous papers that the occurrence of molecular complexes in some OPVs through hydrogen bonds should be contemplated [

21]. Here, we present neutron diffraction data that definitely establish the existence of these complexes with benzyl alcohol and an OPV molecule bearing OH terminal groups (see

Scheme 1). Conversely, we further show that no molecular complex occurs when the terminal group is replaced by a non-hydrogen forming group [

28].

2. Results and Discussion

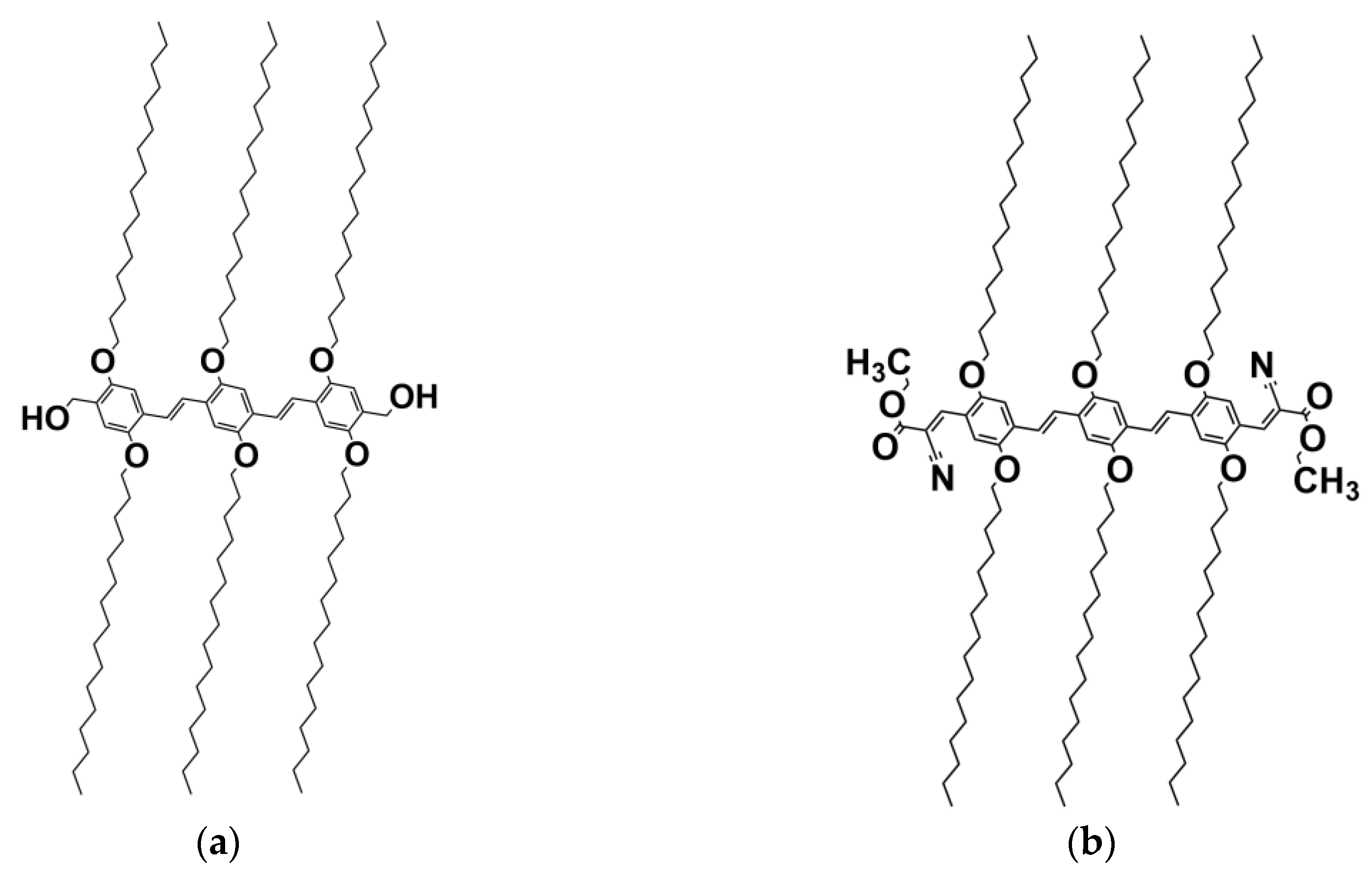

The oligo vinylene phenylene molecules investigated herein presented in scheme 1 are typical “chimera” molecules[

5,

28]. They consist of a central core made of phenyl groups linked by ethylene groups, and six aliphatic armes containing 16 carbons each. The structure is either completed with two CH

3-OH terminal groups that give a hydrogen bonding character to this molecule (OPVOH scheme 1a), and that mimic part of the benzyl alcohol or a NCOOC

2H

5 group (OPVR scheme 1b) free of hydrogen bond character [

28].

The present study of the molecular strcuture has been carried out by X-ray and neutron diffraction in systems prepared from hydrogenous benzyl alcohol (C7H9OH, called BzOHH) and deuterated benzyl alcohol (C7D9OH, called BzOHD).

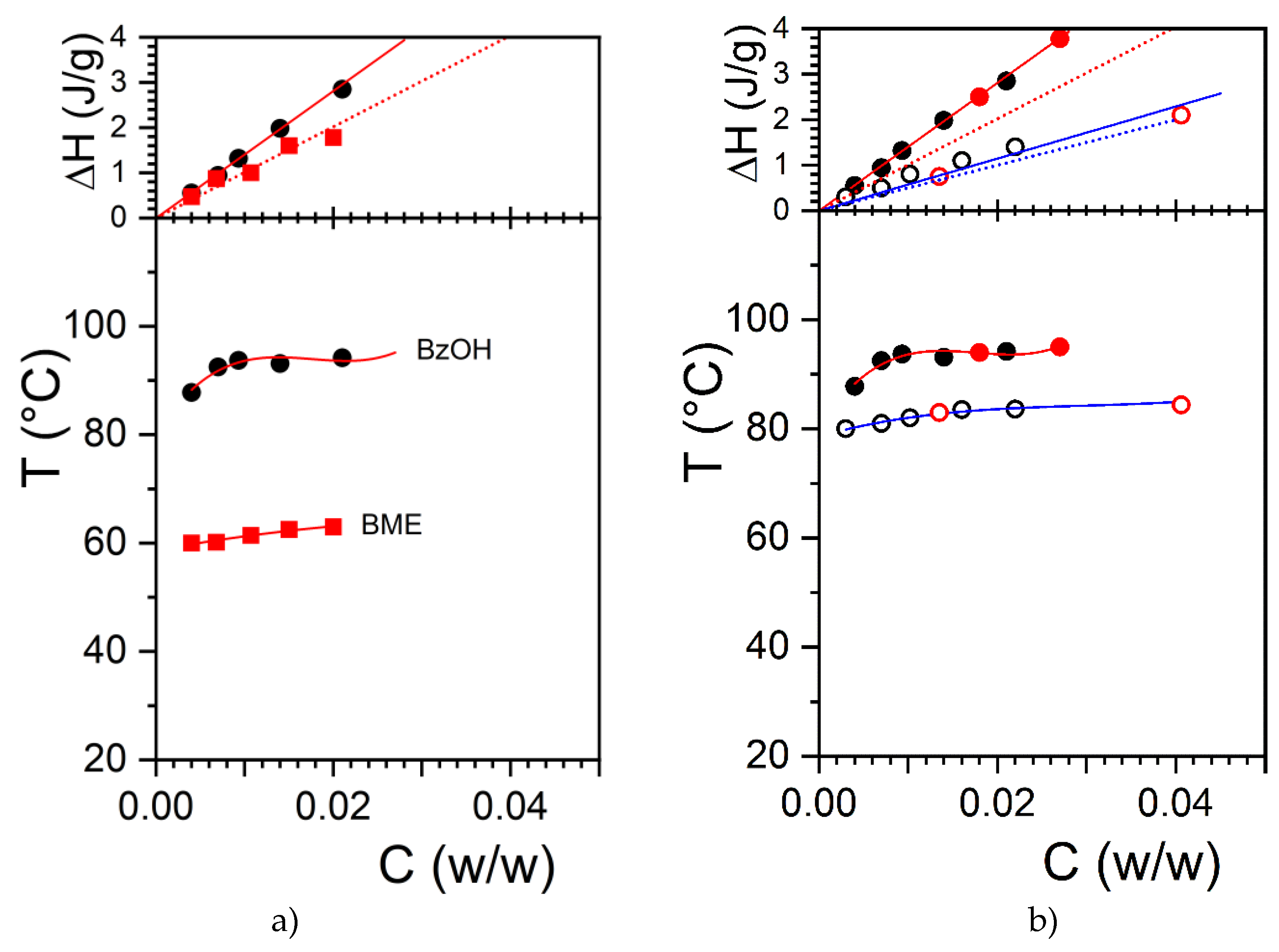

2.1. Thermodynamics

In a previous paper we had reported on the temperature-concentration phase diagram for OPVOH/benzyl alcohol and OPVOH/benzyl methyl ether [

21]. The chemical structure of benzyl methyl ether (BME) is very close to that of benzyl alcohol except that the OH function is replaced by OCH

3, which impairs the formation of hydrogen bonds.

The large difference in melting temperature between OPVOH/BzOH

H and OPVOH/BME together with the diffference in melting/formation enthalpies led us to suspect that benzyl alcohol may form a molecular complex with OPVOH through the formation of hydrogen bonds (see

Figure 1a) That the extrapolated melting enthalpy to C

OPVOH= 1 gives a values much larger than that measured in the solid state for OPVOH/BzOH gels as opposed to what is seen for OPVOH/BME supports the hypothesis of a differing molecular structure[

21]. This is further observed for the OPVR/BzOH systems in

Figure 1b, where the extrapolated enthalpy is found virtually identical to that in the solid state.

Yet, no direct demonstration had able us to confirm this conjecture so far. Note that this effect cannot be related to the solvent quality, which does not affect the value of the melting enthalpy.

The T-C phase diagram of OPVOH and OPVR in hydrogenous and deuterated benzyl alcohol is shown in

Figure 1. The use of deuterated benzyl alcohol instead of the hydrogenous version does not alter the thermodynamic properties of the organogels. The formation and melting temperatures are identical as are the associated enthalpies. Comparing the neutron diffraction patterns obtained with hydrogenous benzyl alcohol and deuterated benzyl alcohol is therefore a legitimate procedure, something already well-documented [

29].

To extend further this study, we have studied another OPV molecule, namely OPVR, where the chemical structure of the terminal group theoretically prevents the molecule to establish hydrogen bonds with benzyl alcohol (

Scheme 1b). As can be seen in the melting temperature of OPVR in benzyl alcohol is lower than that of OPVOH. Unlike OPVOH, extrapolation of the melting enthalpy to C= 1 does give a value nearly identical to that measured in the solid state (

Figure 1). In this system, the formation of an OPVR/benzyl alcohol complex is therefore not expected. Here too, there is no difference in the melting properties of OPVR organogels whether hydrogenous or deuterated benzyl alcohol are used (

Figure 1).

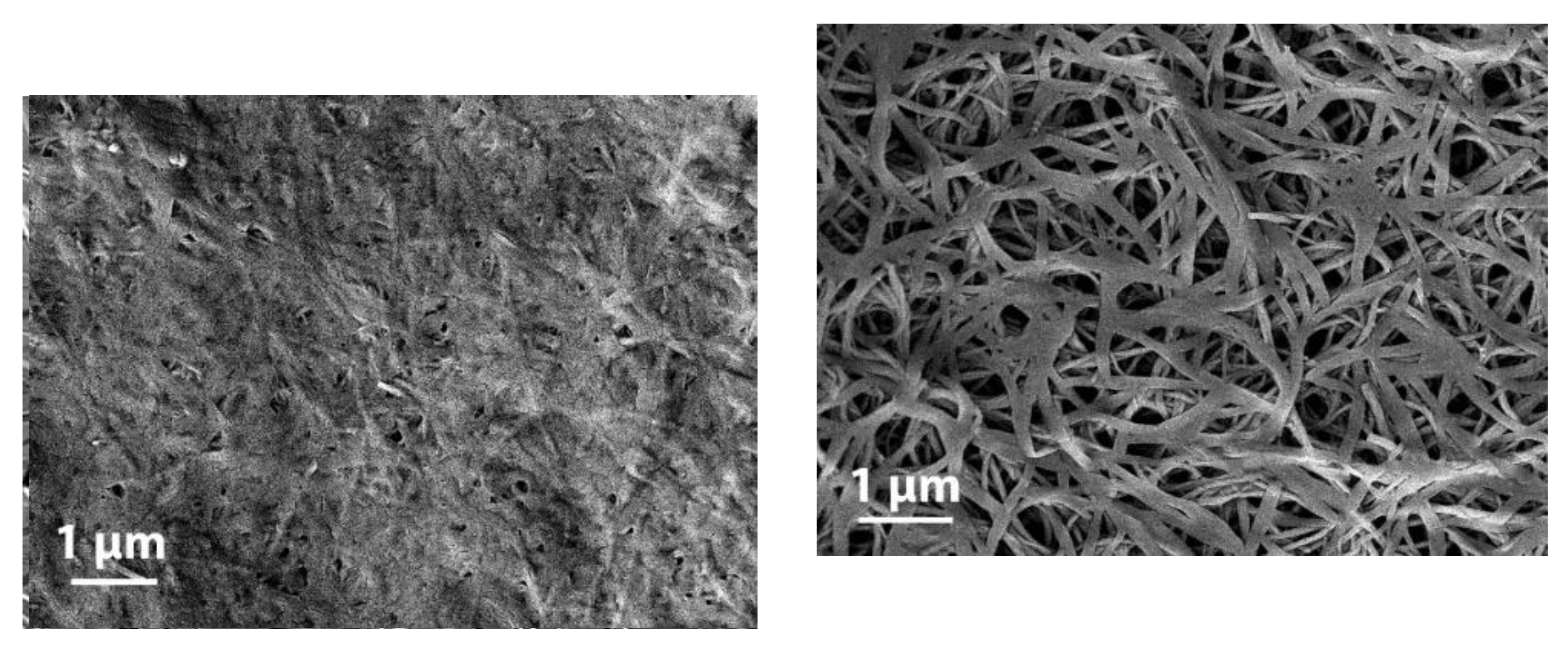

2.2. Morphology

The morphology of these organogels is also strongly dependent upon the terminal groups. OPVOH/benzyl alohol have un unusual morphology of these gels, which is of the hub-like type with thin ribbon-like fibrils that radiate from well-identified centers

Figure 2 top left). Conversely, OPVR/benzyl alocohol organogels display the commonly observed morphology, namely randomly-dispersed fibrils (

Figure 2 bottom). Interestingly, drying OPVOH/ benzyl alcohol gels for SEM observation leads to an apparent collapse of the gel structure (

Figure 2 top right) unlike what is seen with OPVR gels. This effect may arise from the dismantling of the OPVOH/benzyl alcohol molecular complex in the course of the drying process.

2.3. Neutron Diffraction for Studying Molecular Compounds

The main technique for deriving the molecular structure is radiation diffraction, and more commonly X-ray diffraction. Neutron diffraction offers further possibilities, especially in the case of molecular complexes thanks to the availability of the isotopic labelling [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

In the case of neutron diffraction, the intensity is written [

31]:

where a

i and a

j are the neutron scattering length of species i and j and r

ij the associated distance.

For systems comprising two types of molecules, 1 and 2, (1) is written:

where A

1 and A

2 are the scattering amplitudes of molecules 1 and 2, that are calculated by summing the scattering lengths of their constituting atoms (

) [

30]. It is understood that for the third term of relation 2 only the terms where A

m≠ A

n are considered. As opposed to X-rays, these scattering amplitudes do not depend on q as neutrons interact only with the nucleus [

30,

32], whose size is negligible with respect to the van der Waals radius. Relation (2) is rewritten:

For systems composed of a crystallizable component C and of a solvent S, two cases can occur: a solid solution where the solvent is totally expelled out of the crystal, and a molecular complex where the co-crystallization of both species occurs. The latter are characterized by a stoichiometric composition Cγ, corresponding to the number of solvent molecules S per crystallizable molecules C.

In the case of a solid solution, the cross-term in relation (2) vanishes so that:

Under these conditions, the diffraction pattern of the crystals from molecules C, I(q) does not depend upon the value of the scattering amplitude of AS (no change in peak intensity nor in peak number).

In the case of molecular complexes, the cross-term cannot be neglected. Also, there are two types of solvent molecules if the concentration is below the stoichiometric composition, those remaining liquid and those participating in the co-crystals. The intensity is written:

where

is the diffraction by the solvent molecules that are part of the molecular complex and thus organized, while

corresponds to the diffraction of solvent molecules in the liquid phase. As a result, the diffracted intensity from the molecular complex reads:

Therefore, modifying the scattering amplitude of the solvent molecules results in altering the diffraction pattern of the system, such as appearance or disappearance of peaks as well as modification in relative intensities [

25,

33]. Note that the use of isotopes does not change the molecular structure [

25,

32,

33].

Neutron diffraction therefore allows one to distinguish qualitatively and straightforwardly a solid solution from a molecular complex thanks to the availability of hydrogenous and deuterated solvents.

2.4. Diffraction Data

The diffraction data have all been recorded in a domain of transfer momentum q ( λ= wavelength, θ= scattering angle) ranging from 0.5 to 10 nm-1. As the solvent displays a flat scattering in this q-range, only the empty cell has been subtracted from the raw spectra.

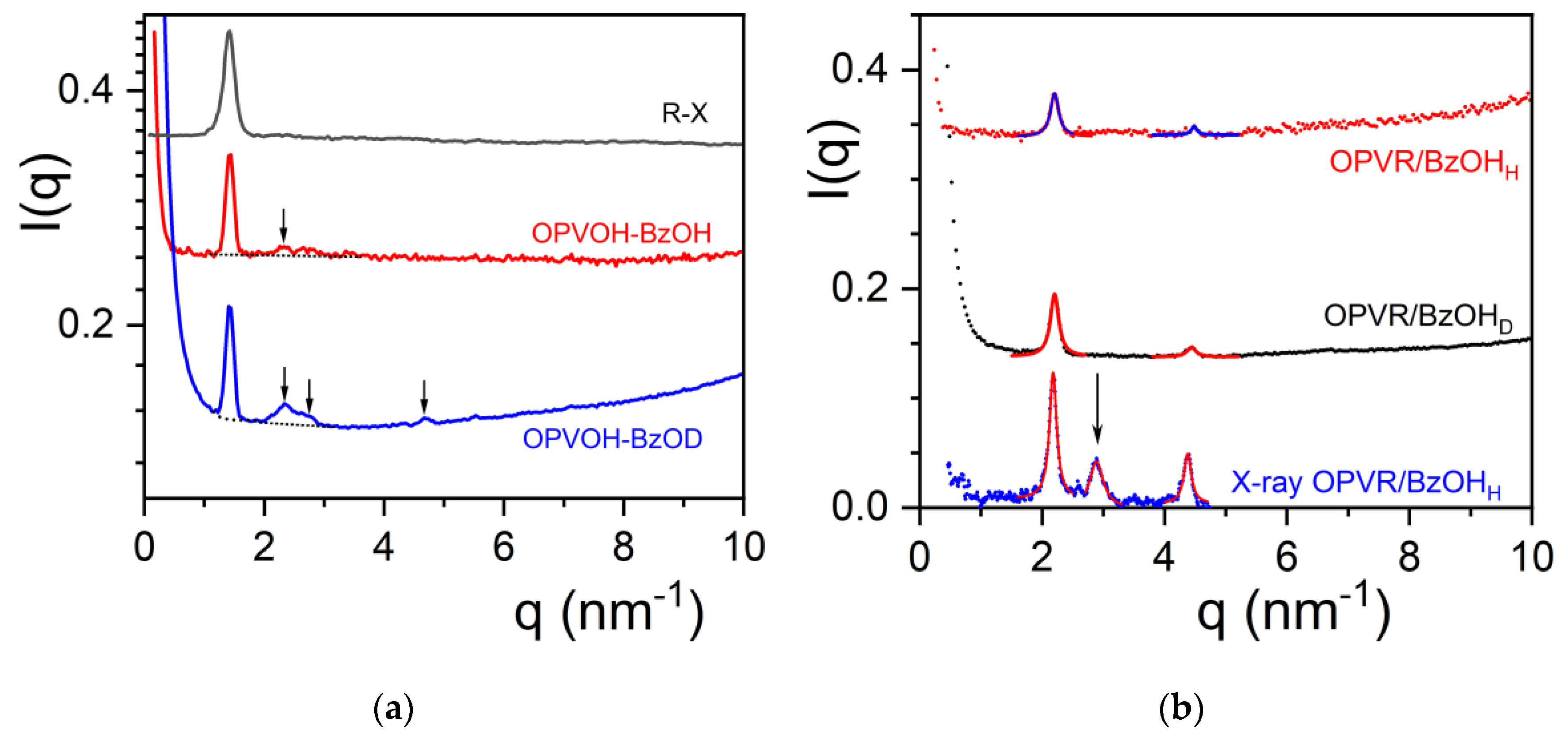

There is a significant difference between the diffraction patterns recorded by X-ray and by neutrons for the OPVOH/benzyl alcohol systems as seen in

Figure 3a. While there is only one peak at q= 1.405 nm

-1 for the X-ray pattern, other peaks appear in the neutron patterns. A weak peak is seen for OPVOH/BzOH

H at q= 2.329 nm

-1, against three additional peaks for OPVOH/BzOH

D at q= 2.329 nm

-1, q= 2.79 nm

-1 and q= 4.672 nm

-1 (see

Table 1). Miller indices are assigned to the peaks by taking the π-π stacking direction as the c axis (

Table 1). The relative intensities of the neutron diffraction peaks for each systems , I(q

i) in %, is calculated by:

where σ

i is the surface of peak i as determined by means of a fit with a Lorentzian function:

where S

B the flat background (solvent+incoherent), A a constant, q

o the peak maximum and ∆q the full width at half maximum.

The difference in relative intensities between peaks from OPVOH/BzOHH and OPVOH/BzOHD allows one to conclude unambiguously that OPVOH and benzyl alcohol form a molecular complex.

The peak at q= 2.329 nm

-1 for OPVOH/BzOH

D corresponds to a distance d= 2.7 nm close to the spacing between the terminal OH groups (2.6 nm). It therefore corresponds to the 100 plane which contains the BzOH molecules. The other peaks are simply second orders of the 010 and 100 planes, which shows the high degree of organization within the OPVOH fibrils. A possible model is drawn in

Figure 3a showing the way the benzyl acohol molecule can interact with OPVOH.

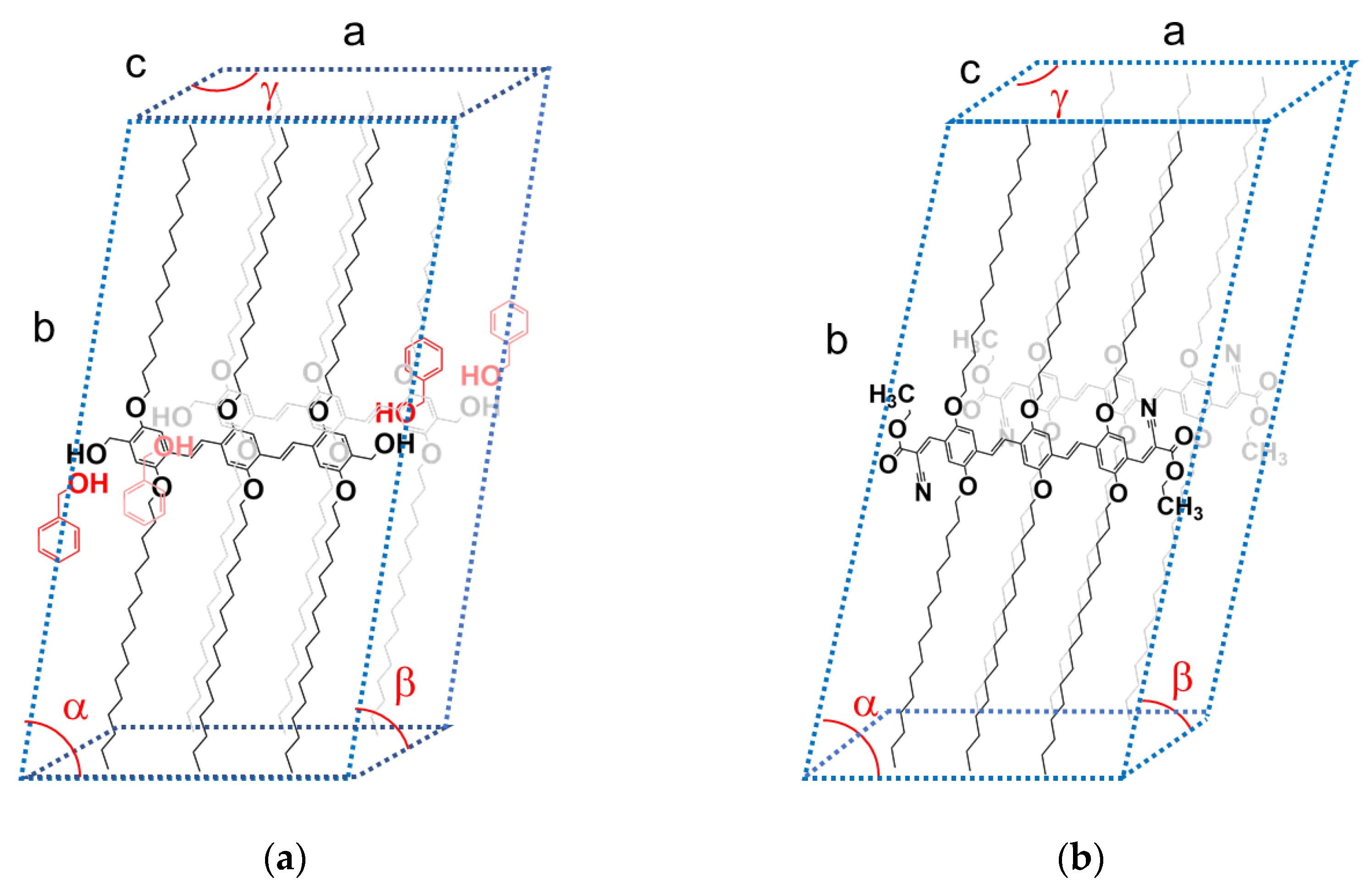

Figure 4.

a) tentative monoclinic crystalline lattice for OPVOH/benzyl alcohol gels with a tentative positioning of the benzyl alcohol molecules; a= 2.7 nm, b= 4.89 nm, c= 0.35 nm, α= 79± 2°, β= γ= 90°. b) tentative triclinic crystalline lattice for OPVR/benzyl alcohol gels based on a previous paper [

28] a= 2.8 nm, b= 4.89 nm, c= 0.49 nm, α= 79±2°, β= 42±2°, γ= 142±4°.

Figure 4.

a) tentative monoclinic crystalline lattice for OPVOH/benzyl alcohol gels with a tentative positioning of the benzyl alcohol molecules; a= 2.7 nm, b= 4.89 nm, c= 0.35 nm, α= 79± 2°, β= γ= 90°. b) tentative triclinic crystalline lattice for OPVR/benzyl alcohol gels based on a previous paper [

28] a= 2.8 nm, b= 4.89 nm, c= 0.49 nm, α= 79±2°, β= 42±2°, γ= 142±4°.

Drying OPVOH/benzyl alcohol gel, which results in the removal of the solvent from the crystalline lattice, is likely to introduce some local disorganization. This process may account for the observed collapse of the gel morphology.

The outcomes differ conspicuously in the case of OPVR/benzyl alcohol systems. As seen in

Figure 3b the intensities of the neutron diffraction peaks and their positions are virtually identical whether deuterated or hydrogenous benzyl alcohol is used. This demonstrates the absence of a molecular complex in the case of OPVR.

Interestingly, a third peak is observed by X-ray diffraction which is conspicuously absent in the neutron diffraction patterns. This peak corresponds to the 100 plane containing the C

2H

50 group. The neutron scattering amplitude of this group is calcutated

through:

where a

i is the scattering amplitude of each atome constituting the group.

Equation (9) gives a value close to

0 thanks to the negative value of hydrogen a

H= -0.375 [

30]. This therefore accounts for the absence of this peak in the neutron difffraction patterns.

The results are gathered in

Table 2 where the peaks are indexed by again taking the π-π stacking direction as the c-axis. A tentative crystalline lattice is displayed in

Figure 3b.

3. Conclusions

Results presented here provide a conclusive answer to a previous conjecture that predicted the occurrence of a molecular complex of OPVOH molecules in the organogelation process [

21]. Conversely, formation of this complex depends upon the terminal group as shown with OPVR molecules. This may have a direct impact on the differing morphologies of these gels (see figure 2), hub-like type with thin ribbon-like fibrils in OPVOH/benzyl alcohol systems against randomly-dispersed type in OPVR/benzyl alcohol gels, as well as the collape of the gel morphology of the latter (figure 2) [

36]. It is worth emphasizing that the existence of molecular complexes has also been recently demonstrated in the case of triaryl tris amide organogels [

24]. The occurrence of molecular complex is likely to occur in the gelation process of many other systems, and is something to consider when determining the molecular structure, and in accounting for the thermodynamic properties.

4. Materials and Methods

Materials: The synthesis and properties of oligo (p-phenylene vinylene) gelator (OPVOH) is described in reference 17. The basic chemical structure of the molecule used in this study is shown in figure 1. The solvent used for this investigation were benzyl alcohol (BzOH), and benzyl methyl ether (BME). The hydrogenous solvents of high purity grade, were purchased from Aldrich, and were used without further purification. The deuterated benzyl alcohol, C7D7OH, was purchased from Eurisotop (Saclay, France) and used as-received. The preparation conditions for the neutron and the X-ray experiments are the same (quenching temperature, and ageing).

Differential Scanning Calorimetry: Diamond DSC from Perkin Elmer has been used for determining the gel formation and gel melting. Heating and cooling rates ranging from 5°C/min to 15°C/min were used. Approximately 30 mg of previously prepared gels were transferred into stainless steel sample pan. These pans were then hermetically sealed by an O-ring to prevent solvent evaporation.

X-ray diffraction: X-ray diffraction experiments are performed by means of a diffractometer developed at the Institut Charles Sadron in the DiffériX platform. The instrument operates with A monochromatic beam of wavelength λ = 0.154 nm and a hybrid photon counting detector (HPC-Dectrics Pilatus®3 R 300K). The distance sample-detector is set so as to access scattering vectors q= 4πsin(θ/2)/λ (θ= diffraction angle) ranging from q= 0.5 to 10 nm-1. Calibration of the detector is performed with a silver behenate sample. The gel samples are placed in home-made sealed cells of adjustable thickness.

Neutron diffraction: The neutron diffraction experiments have been carried out on D16, a camera located at Institut Laue-Langevin (Grenoble, France) [

37]. D16 is equipped with a new curved detector 38 cm high which covers a 86° solid angle with a high angular resolution of 0.075°. This detector is based on the Trench-MultiWire Proportional Chamber (MWPC) detector technology developed at ILL: 6 modules are mounted side by side in an 3He-filled curved vessel [

38]. Each module consists of 192 cathode blades positioned every 2 mm, and 192 anode wires spaced by 1.5 mm [

39]. The neutron wavelength is selected by beam reflection onto a focussing pyrolytic graphite monochromator. The present experiments were obtained with a neutron wavelength of λ= 0.449 nm, giving access to the following transfer momenta range of 0.6 nm

-1≤ q ≤ 10 nm

-1.

Optical Microscopy: Pictures were taken with a NIKON Optiphot-2 equipped with CCD camera by means of Nomarsky phase contrast. The samples were prepared by re-melting between glass-slides those gels obtained beforehand in a test-tube.

Scanning electron microscopy: The electron microscopy images were obtained on a JEOL (JSM 6700F) FESEM instrument. Hot solutions of OPV/benzyl alcohol were drop casted on silicon wafer and subsequently quenched to 00C in order to form the gel network. The samples were then dried under vacuum at room temperature. The dried gels were further coated by indium sputtering.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, J.M.G.; resources, writing—review and editing, A.A and V.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the ILL for allocating neutron beam time on D16 camera under proposal nr 9-11-2146. The authors are particularly indebted to Dr. Bruno DEME from ILL for his continuous assistance during the neutron diffraction experiments on D16. They also acknowledge C. Saettel-Herr for the DSC measurements, and G. Fleith for the X-ray experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Terech, P.; Weiss, R.G. Low molecular mass gelators of organic liquids and the properties of their gels. Chemical Reviews, 1997, 97, 3133–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terech, P.; Weiss, R.G., Editors Molecular Gels: Materials with Self-Assembled Fibrillar Networks, Springer Verlag, 2006.

- Liu, X.L.; Li, J.L. Soft Fibrillar Materials: Fabrication and Applications, Wiley-VCH, 2013.

- Weiss, R.G. The past, present and future of molecular gels. What is the status of the field, and where is it going? JACS 2014, 136, 7519–7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenet, J.M. Organogels: thermodynamics, structure, solvent role and properties, 2016, N.Y., Springer International Publishing.

-

Molecular Gels, Structure and Dynamics. Monograph in Supramolecular Chemistry, Weiss, R. G., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, 2018.

- Nonappa, L.M.; Behera, B.; Kolehmainen, E.; Maitra, U. Unraveling the packing pattern to gelation using SS NMR and X-ray diffraction: direct observation of the evolution of self-assemble fibres. Soft Matter, 2010, 6, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terech, P.; Aymonier, C.; Loppinet-Serani, A.; Bhat, S.; Banerjee, S.; Das, R.; Maitra, U.; Del Guerzo, A.; Desvergne, J.P. Structural relationships in 2,3-bis-n-decyloxyanthracene and 12-hydrostearic acid molecular gels and aerogels processed in supercritical CO2. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 11409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, A.; Ghosh, Y.K.; Bhattacharya, S. Molecular mechanism of physical gelation of hy-drocarbons by fatty acid amides of natural amino acids. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 7334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.Y.G.; Zhang, H.; Ding, L.; Fang, Y. Glucose-Based Fluorescent Low-Molecular Mass Compounds: Creation of Simple and Versatile Supramolecular Gelators. Langmuir 2010, 26, 5909. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Cavicchi, K.A. Investigation of the relationships between the thermodynamic phase behavior and gelation behavior of a series of tripodal trisamide compounds. Soft Matter, 2012, 8, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Li, J.L. Soft Fibrillar Materials: Fabrication and Applications, Wiley-VCH, 2013.

- Collin, D.; Covis, R.; Allix, F.; Jamart-Grégoire, B.; Martinoty, P. Jamming transition in so-lutions containing organogelator molecules of amino-acid type: rheological and calo-rimetry experiments. Soft Matter, 2013, 9, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.X.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Diaz, N.; Schmutz, M.; Deme, B.; Jestin, J.; Combet, J.; Mesini, P.J. Self-assembling properties of a series of homologous ester-diamides - from ribbons to nanotubes. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armao IV, J.J.; Maaloum, M.; Ellis, T.; Fuks, G.; Rawiso, M.; Moulin, E.; Giuseppone, N. Healable supramolecular polymers as organic metals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 11382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulin, E.; Armao IV, J.J.; Giuseppone, N. Triaryl amine-based supramolecular polymers: structure, dynamics, and functions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisman, A. Phase Equilibria: Basic Principles, Applications, Experimental Techniques 1970, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Point, J. J.; Coutelier, C. Linear high polymers as host in intercalates. Introduction and example. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys 1985, 23, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, U.S.; Mandal, K.D. Chemistry of organic eutectics and 1/1 addition compounds: p-phenyl diamide catechol system. Thermochimica Acta 1989, 138, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.J.; Tomovic, Z.; Albertus; Schenning, P.H.J.; Meijer, E.W. Insight into the chiral induction in supramolecular stacks through preferential chiral solvation. Chem. Com. 2011, 47, 3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Rochas, C.; Ajayaghosh, A.; Guenet, J.M. Solvent-mediated fiber growth in organogels. Soft Matter, 2011, 7, 9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartha, K.K.; Babu, S.S.; Srinivasan, S.; Ajayaghosh, A. Attogram Sensing of Trinitrotoluene with a Self-Assembled Molecular Gelator. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, G.; Chakraborty, A.; Pal, P.; Jana, B.; Ghosh, S. Direct Participation of Solvent Molecules in the Formation of Supramolecular Polymers. Chem.-A Eur. J. 2022, 28, e2022010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenet, J.M.; Deme, B.; Gavat, O.; Moulin, E.; Giuseppone, N. Evidence by neutron diffraction of crystallo-solvates in tris-amide triarylamine organogels and in their hybrid thermoreversible gels with PVC. Soft Matter, 2022, 18, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guenet, J.M. Contribution of neutron diffraction to the study of crystallo-solvates (crystallo-solvates) from polymers and from supramolecular polymers. Polymer 2024, 293, 126638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Collin, D.; Gavat, O.; Carvalho, A.; Moulin, E.; Giuseppone, N.; Guenet, J.M. Effect of solvent isomer on the gelation properties of tri-aryl amine organogels and their hybrid thermoreversible gels with poly[vinyl chloride]. Soft Matter, 2022, 18, 5575. [Google Scholar]

- Collin, D.; Viswanatha-Pillai, G.; Gavat, O.; Vargas Jentzsch, A.; Moulin, E.; Giuseppone, N.; Guenet, J.M. Some remarkable rheological and conducting properties of hybrid PVC thermoreversible gels/organogels. Gels, 2022, 8, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.S.; Praveen, V.K.; Ajayaghosh, A. Functional π-Gelators and Their Applications. Chemical Reviews 2014, 114, 1973–2129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strazielle, C.; Benoit, H. Some Thermodynamic Properties of Polymer-Solvent Systems. Comparison between Deuterated and Undeuterated Systems. Macromolecules 1975, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, GE. Coherent neutron-scattering amplitudes. Acta Crystallogr A 1972, A28, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotton, J.P. in Neutron, X-ray and light scattering, Eds P. Lindner and T. Zemb, Elsevier 1991.

- Rundle, R.E.; Schull, C.G.; Wollan, E.O. The crystal structure of thorium and zirconium dihydrides by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Acta Cryst. 1952, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Point, J.J.; Damman, P.; Guenet, J.M. Neutron diffraction study of poly(ethylene oxide) p dihalogenobenzene crystalline complexes. Polymer Communication 1991, 32, 477. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko, F.; Seto, N.; Sato, S.; Radulescu, A.; Schiavone, M.M.; Allgaier, J.; Ute, K. Development of a Simultaneous SANS/FTIR Measuring System. Chemistry Letters, 2015, 44, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, F.; Radulescu, A.; Nakagawa, H. Simultaneous SANS/FTIR measurement system incorporating the ATR sampling method. J. Appl. Cryst. 2011, 56, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, D. .; Thierry; A.; Rochas, C; Ajayaghosh, A.; Guenet, J.M. Key role of Solvent type in organogelation. Soft Matter, 2012, 8, 8714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiglio, V.; Giroud, B.; Didier, L.; Demé, B. D16 is back to business: more neutrons, more space, more fun. Neutron News, 2015, 26, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffet, J.C.; Cristiglio, V.; Cuccaro, S.; Guérard, B.; Marchal, J.; Pentenero, J.; Platz, M.; Van Esch, P. Characterisation of a neutron diffraction detector prototype based on the Trench-MWPC technology. JINST 2017, 12, C12009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffet, J.C.; Clergeau, F.; Cuccaro, S.; Démé, B.; Guérard, B.N.; Marchal, J.; Pentenero, J.; Sartor, N.; Turi, J. Development of a large-area curved Trench-MWPC 3He detector for the D16 neutron diffractometer at the ILL. EPJ Web of Conferences 2023, 286, 03010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).