1. Introduction

Hip osteoarthritis (HOA) is a chronic degenerative condition that causes pain, stiffness, and limited mobility in both the hip and lumbar regions, being one of the leading causes of disability in adults. The prevalence is estimated between 8% and 10.4% in the general population [

1,

2], with geographical variations and a marked increase with age [

3,

4,

5]. THA has been established as the most effective surgical treatment to relieve pain and restore function in patients with advanced HOA [

6].

Despite the clear benefits of THA, this surgical procedure is associated with potential complications [

7]. Consequently, some patients develop postoperative LBP, which can significantly challenge the recovery process [

8]. This complication can generate significant disability, negatively impacting quality of life. Although the biomechanical connection between the hip and lumbar spine is well documented, the factors contributing to the development of LBP after surgery continue to be the subject of study.

The incidence of LBP associated with untreated HOA has been reported between 21.2% and 100% [

9,

10]. Recent studies, such as that by Vigdorchik et al., have suggested that THA can alleviate LBP in up to 82% of patients with HOA within two years of follow-up [

11]. However, there is a possibility that THA may generate biomechanical changes in the lumbar spine, accelerating disc degeneration and contributing to the appearance of new episodes of LBP in the long term [

12,

13].

Given the limited evidence on the long-term impact of THA on the development of LBP, further investigation with rigorous methodology is warranted. This study hypothesizes that THA in patients with OA will be associated with an increased risk of developing long-term LBP. The primary objective of this study is to determine the long-term impact of THA on the incidence of LBP in patients with and without pre-existing LBP, while controlling for potential confounding factors.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

A cohort study was conducted in patients diagnosed with HOA who underwent THA. Each patient was divided into two periods: 1) prior to THA (unexposed) and 2) after THA (exposed).

Participants and Follow-Up

The study included all patients who underwent THA at the University Clinical Hospital Lozano Blesa in Zaragoza between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2020, aged between 18 and 72 years at the time of the intervention. The complete eligibility criteria are detailed in

Table 1.

In the preoperative THA group, the start of follow-up was established at the time of diagnosis of HOA. Follow-up was extended until the occurrence of the first episode of LBP, the THA intervention or 5 years, whichever occurred first. In the postoperative THA group, follow-up began on the date of the intervention and continued until the occurrence of the first episode of LBP, the end of follow-up or 5 years, whichever occurred first.

Variables and Data Sources

The exposure variable was considered to be the preoperative THA or postoperative THA group. The outcome variables were the occurrence of LBP within 5 years of the start of follow-up and the time until its occurrence. To control for confounding, information on age, sex, height, and weight at the time of surgery was collected. All information was extracted from the Electronic Medical Records of the Aragon Health Service.

Data Analysis

Several proportional hazards models were fitted, all of which considered the exposure group as the independent variable and time to the first episode of LBP as the dependent variable. First, an unadjusted model was created, followed by a model adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and the period of follow-up initiation. Finally, a model for paired data was used, pairing the preoperative THA and postoperative THA periods for each patient and adjusting for age at the start of follow-up for each period. Hazard Ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Sensitivity Analysis

To assess the potential existence of selection or confounding biases, two additional sensitivity analyses were performed. First, the analysis was conducted with a smaller restricted sample, applying only the absolute exclusion criteria. Second, a target trial emulation study design was implemented. This type of design has been described in other articles [

14]. This approach first involves specifying the protocol of a hypothetical target trial and then emulating the trial as faithfully as possible using observational data.

The selection criteria for the hypothetical trial were: 1) diagnosed with HOA, 2) not previously undergone THA prior to the start of the trial, 3) not have developed LBP between diagnosis and the start of the trial, and 4) not meet any of the exclusion criteria in

Table 1. At the start of the trial, subjects were assigned to one of two groups: 1) not intervened and 2) THA-intervened, based on whether they underwent the surgery during the month of trial initiation. Subsequently, subjects were followed until they developed a first episode of LBP, 5 years passed, the end of the study follow-up was reached, or, in the case of the non-intervened group, they underwent THA, whichever occurred first. Finally, through combined logistic regression analysis, the incidence of LBP in the 5 years following the start of the study was modeled. In our case, this hypothetical trial was emulated with the available data and replicated 132 times, considering as the start date each month between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2020. All analyses were performed using R software.

Ethical Aspects

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research of the Autonomous Community of Aragon with the code C.P.-C.I.-PI21/346 and registered in the ClinicalTrial.gov database with the identifier NCT05647629. Authorization was obtained from the hospital’s medical director to conduct this study.

3. Results

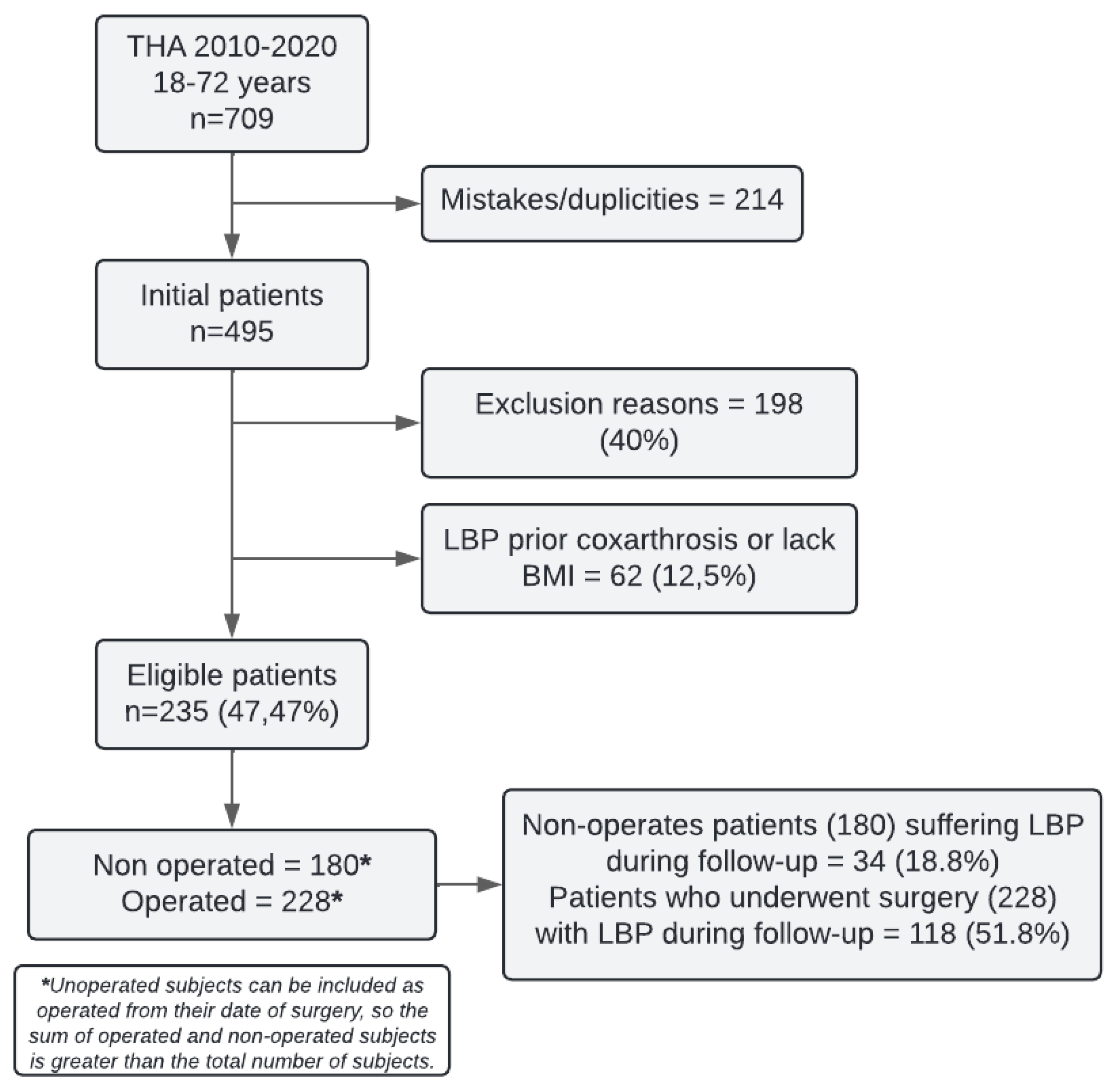

495 subjects diagnosed with HOA and undergoing THA were identified at the hospital during the 2010-2020 period. After applying exclusion criteria, 198 patients were excluded. Additionally, 62 more patients were excluded due to LBP prior to the diagnosis of coxarthrosis or lack of BMI data, leaving a total of 235 eligible patients for the study. 180 patients were included in the preoperative THA group and 228 in the postoperative THA group (

Figure 1).

Of the subjects included in the preoperative THA group, 34 experienced an episode of LBP during a median follow-up of 35 months (IQR: 15-72). In the postoperative THA group, 118 patients experienced an episode of LBP during a median follow-up of 51 months (IQR: 30-83). From the preoperative THA group, 173 subjects were subsequently operated on and were also included in the postoperative THA group.

Baseline Characteristics and Initial Follow-Up Period

The proportion of men and women is similar in both groups, with a slight difference in median age. BMI was constant between the two groups, with an average value of 29 (

IQR 26-32) (

Table 2). The first records obtained date from 2001 to the last ones from 2022, over a 21-year period, with the greatest pre-surgical follow-up accumulating between 2006 and 2015 and the post-surgical group between 2011 and 2020 (

Table 2).

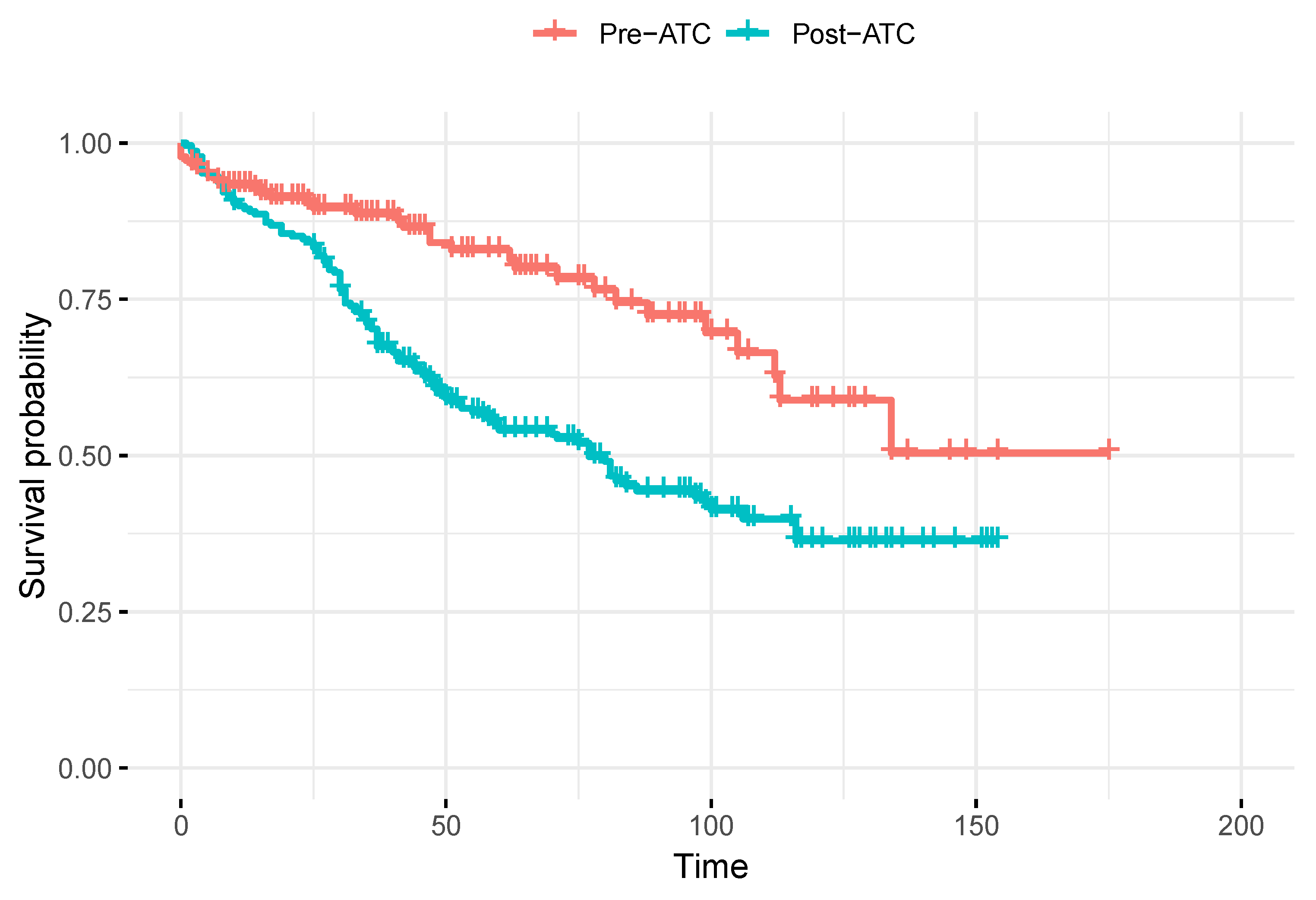

Survival Function and HR of LBP During 5 Years of Follow-Up

Table 3 presents the HRs for the development of LBP after 5 years of follow-up across the different analysis models. The unadjusted model estimated an HR of 2.2 (

95%CI 1.5-3.2) for patients in the post-THA period compared to the preoperative THA period, with their survival function over time shown in

Figure 2. However, after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and the period of study inclusion, the HR decreased to 1.6 (

95%CI 1.0-2.6). In the matched and age-adjusted analysis, the HR was further reduced, showing a value of 1.1 (

95%CI 0.4-3.0).

Sensitivity Analysis

Replicating the matched analysis and excluding only subjects with absolute exclusion criteria, an LBP HR of 0.8 (95%CI 0.3-1.8) was estimated for the postoperative THA period compared to the preoperative THA period. This suggests that matching and adjusting for age can balance the baseline differences between the groups. Finally, the approach using target trial emulation, which adjusts for age, sex, BMI, disease progression time, and the period of study inclusion, estimated a RR of 1.04 (95%CI 0.7-1.8).

4. Discussion

Previous studies have reported a prevalence of LBP around 49.4% and a recovery rate of 88.2% after THA with a two-year follow-up [

8,

11]. However, this short-term follow-up period may not fully capture the prolonged impact of muscle atrophy on lumbar biomechanics, underscoring the need for further long-term investigations.

The initial hypothesis of this study was based on the potential long-term biomechanical alterations that may arise due to damage and weakness of the psoas muscle following THA [

8,

12,

15,

16]. This powerful, bilateral muscle plays a crucial role in lumbopelvic biomechanical control and stability. Unilateral damage could result in an asymmetric balance of tensile forces at its dorsolumbar origin (T12 to L4), leading to facet joint overload in the lumbar structures and progressive long-term damage.

Eligibility criteria were defined to ensure reliable long-term outcomes. Age was limited to 18-72 years to reduce loss to follow-up due to natural causes. Patients with previous lower extremity fractures were excluded to avoid confounding orthopedic factors, and those with significant mental impairments were excluded due to potential difficulties with follow-up. These measures aimed to identify patients with OA without other comorbidities and strengthen the internal validity of the study.

Our sample revealed a similar distribution between men and women (64-62% and 36-38% respectively and an average BMI of 29, ensuring baseline comparability between groups. In the unadjusted analysis, the occurrence of postoperative LBP had a median duration of 25 months (

IQR: 3-66,

SD 1.35), suggesting an earlier manifestation in the surgical group, possibly due to medium-to-long-term psoas atrophy (

Table 2 and

Figure 2). This temporal finding indicates that the onset of LBP after THA may not be immediate, but rather develop over a variable time interval [

12,

17], with a greater dispersion after the initial 25 months, the time required for the atrophied psoas to cause biomechanical problems in the lumbar spine.

Initially, our unadjusted analyses revealed a higher incidence of LBP in THA patients, with an HR of 2.23 (95%CI: 1.5-3.2). However, when adjusting for relevant confounding variables such as age, sex, BMI, and recruitment period, this association attenuated to an HR of 1.64 (95%CI: 1.0-2.6). Subsequently, in a matched adjusted analysis, where we compared each patient in the preoperative and post-surgical periods, the HR decreased to 1.09 (95%CI: 0.4-3.0), indicating that THA alone does not increase the risk of LBP. These results are consistent with those obtained through target-trial emulation, where we calculated the 5-year RR as 1.03 (95%CI: 0.7-1.8), suggesting that there are no differences in the long-term risk of LBP between patients who underwent the intervention and those who did not.

“Target-trial emulation

” is an advanced epidemiological technique that aims to replicate the conditions of a randomized clinical trial using observational data [

18]. This approach is particularly valuable when conducting a clinical trial is infeasible due to economic, ethical, or logistical reasons [

19]. However, it is important to note that, like other observational studies, target-trial emulation cannot fully control for unknown or unmeasured confounding factors, which may impact the validity of the obtained results [

20].

Despite the initial findings suggesting an association between THA and LBP, a rigorous multivariable analysis revealed that this relationship is primarily due to confounding factors. The simulation of a clinical trial supported these results, indicating that surgery cannot be considered either protective or causative of subsequent LBP. This study, with its retrospective design, methodological rigor, and extensive follow-up, underscores the importance of controlling for confounding variables in the evaluation of complex data. The results obtained contribute to a better understanding of the risk profile associated with THA.

Previous investigations, such as that conducted by Vigdorchik et al

., have reported postoperative improvements [

11]. However, our study suggests that the risk of developing LBP is similar among patients diagnosed with HOA, regardless of whether they receive surgical treatment. Therefore, THA cannot be considered an intervention that improves LBP in addition to hip pain. These findings are consistent with research indicating that muscle atrophy may result from disuse, not only of the psoas muscle [

12], but also from the weakness of other muscles involved in hip control [

21,

22]. Furthermore, these results tend to be consistent, regardless of the surgical technique employed [

23].

Our findings support the evidence suggesting that THA does not increase the incidence of postoperative LBP, but it is also not a technique that definitively solves this problem. Therefore, it should not be promoted as a definitive solution. It is essential that patients be properly informed that surgery does not guarantee the complete disappearance of their symptoms. A multidisciplinary approach, including physical therapy, exercise, nutritional advice, and in certain cases, pharmacological treatments, may be necessary for the optimal and effective management of LBP.

5. Conclusions

This study found no conclusive evidence to support an increased risk of LBP following THA. Employing advanced epidemiological analysis techniques, we estimated a 5-year RR of 1.03 for the development of LBP in patients undergoing THA, indicating that the surgery neither substantially increases nor decreases the long-term risk of LBP compared to those who did not undergo surgical intervention. The initial association observed was not statistically significant after adjusting for key confounder such as age, sex, BMI, and disease progression time.

These findings do not support the hypothesis that THA increases the long-term risk of postoperative LBP, nut they also contradict previous hypotheses suggesting that THA could resolve pre-existing LBP. This study highlights the importance of considering demographic and clinical factors when evaluating the risks associated with THA, providing a more solid basis for making informed clinical decisions.

A critical appraisal of this study must consider its limitations, particularly the potential for confounding bias introduced by its retrospective design. Additional studies, preferably with prospective and controlled designs, are needed to confirm and expand these findings, as well as to explore more deeply the underlying factors that could influence the relationship between THA and long-term LBP.

In summary, this study offers a critical perspective on the relationship between THA and the occurrence of postoperative LBP, underscoring the need for continued research to improve the quality of life for patients and optimize clinical outcomes in those undergoing this intervention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.J.G.P. and E.M.G.T.; methodology, F.J.G.P., S.B.R.H., and E.M.G.T.; data collection, F.J.G.P. and S.B.R.H.; data curation, A.C.P.; formal analysis, A.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, F.J.G.P., S.B.R.H., A.C.P., and E.M.G.T.; writing—review and editing, F.J.G.P., S.B.R.H., A.C.P., and E.M.G.T.; supervision, A.C.P. and E.M.G.T.; project administration, F.J.G.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Research of the Community of Aragon (CEICA) with the protocol code C.P.-C.I.-PI21/346 and registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database with the identifier NCT05647629. Authorization to conduct the study was also obtained from the Medical Director of the Lozano Blesa Clinical Hospital in Zaragoza, Spain.

Informed Consent Statement

This study has a confidentiality agreement and a specific purpose for research studies approved by the Medical Director of the Lozano Blesa Clinical Hospital in Zaragoza, Spain.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions and agreements with the hospital from which they were obtained.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the iHealthy Research Group for their support and collaboration in this project. Their dedication has significantly enriched our scientific work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HOA |

Hip osteoarthritis |

| THA |

Total hip arthroplasty |

| LBP |

Low back pain |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| HR |

Hazard ratio |

References

- Dagenais S, Garbedian S, Wai EK. Systematic review of the prevalence of radiographic primary hip osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:623–37. [CrossRef]

- Lo J, Chan L, Flynn S. A systematic review of the incidence, prevalence, costs, and activity and work limitations of amputation, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, back pain, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord injury, stroke, and traumatic brain injury in the United States: A 2019 update. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021;102:115–31. [CrossRef]

- Fan Z, Yan L, Liu H, Li X, Fan K, Liu Q, et al. The prevalence of hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2023;25:51. [CrossRef]

- Hoaglund FT, Steinbach LS. Primary osteoarthritis of the hip: etiology and epidemiology. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:320–7. [CrossRef]

- Skousgaard SG, Hjelmborg J, Skytthe A, Brandt LPA, Möller S, Overgaard S. Probability and heritability estimates on primary osteoarthritis of the hip leading to total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide population based follow-up study in Danish twins. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:336. [CrossRef]

- BASSAMAT O. AHMED D.N.Sc. EMHMS, ABD EL-NABY D.N.Sc. AG. Discharge needs of patients after total hip arthroplasty. Med J Cairo Univ 2018;86:179–85. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Rao S, Mekkawy KL, Rahman R, Sarfraz A, Hollifield L, et al. Risk factors for pain after total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Arthroplasty 2023;5:19. [CrossRef]

- Parvizi J, Pour AE, Hillibrand A, Goldberg G, Sharkey PF, Rothman RH. Back pain and total hip arthroplasty: A prospective natural history study. Clin Orthop Relat Res [Internet]. 2010;468(5):1325-30. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Galim P, Ben-Galim T, Rand N. Hip-spine syndrome: the effect of total hip replacement surgery on low back pain in severe osteoarthritis of the hip. Spine (Phila Pa). 1976;32:2099–102.

- Wang W, Sun M, Xu Z, Qiu Y, Weng W. The low back pain in patients with hip osteoarthritis: current knowledge on the diagnosis, mechanism and treatment outcome. Ann Jt 2016;1:9–9. [CrossRef]

- Vigdorchik JM, Shafi KA, Kolin DA, Buckland AJ, Carroll KM, Jerabek SA. Does low back pain improve following total hip arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty 2022;37:S937–40. [CrossRef]

- Mak D, Chisholm C, Davies AM, Botchu R, James SL. Psoas muscle atrophy following unilateral hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol 2020;49:1539–45. [CrossRef]

- Oichi T, Taniguchi Y, Oshima Y, Tanaka S, Saito T. Pathomechanism of intervertebral disc degeneration. JOR Spine 2020;3:e1076. [CrossRef]

- Hernán MA, Robins JM. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol 2016;183:758–64. [CrossRef]

- Eyvazov K, Eyvazov B, Basar S, Nasto LA, Kanatli U. Effects of total hip arthroplasty on spinal sagittal alignment and static balance: a prospective study on 28 patients. Eur Spine J 2016;25:3615–21. [CrossRef]

- Gouveia K, Shah A, Kay J, Memon M, Simunovic N, Cakic JN, et al. Iliopsoas tenotomy during hip arthroscopy: A systematic review of postoperative outcomes. Am J Sports Med 2021;49:817–29. [CrossRef]

- Genc AS, Agar A, Güzel N. Evaluation of psoas muscle atrophy and the degree of fat infiltration after unilateral hip arthroplasty. Cureus 2023;15:e41506. [CrossRef]

- Kutcher SA, Brophy JM, Banack HR, Kaufman JS, Samuel M. Emulating a randomised controlled trial with observational data: An introduction to the target trial framework. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:1365–77. [CrossRef]

- Matthews AA, Danaei G, Islam N, Kurth T. Target trial emulation: applying principles of randomised trials to observational studies. BMJ 2022;378:e071108. [CrossRef]

- Matthews AA, Young JC, Kurth T. The target trial framework in clinical epidemiology: principles and applications. J Clin Epidemiol 2023;164:112–5. [CrossRef]

- Rasch A, Byström AH, Dalen N, Berg HE. Reduced muscle radiological density, cross-sectional area, and strength of major hip and knee muscles in 22 patients with hip osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop 2007;78:505–10. [CrossRef]

- Rasch A, Byström AH, Dalén N, Martinez-Carranza N, Berg HE. Persisting muscle atrophy two years after replacement of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:583–8. [CrossRef]

- Vasarhelyi EM, Williams HA, Howard JL, Petis S, Barfett J, Lanting BA. The effect of total hip arthroplasty surgical technique on postoperative muscle atrophy. Orthopedics 2020;43:361–6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).