1. Introduction

The automotive industry’s traditional reliance on fossil fuels has contributed large greenhouse gas emissions in the last Century, which has contributed to climate change. According to a recent European Union report, transport is the only sector where greenhouse gas emissions have increased significantly in Europe over the past three decades, rising 33.5% between 1990 and 2019 [

1]. Achieving climate neutrality by 2050 requires reducing the sector’s fossil fuel dependency [

2]. With tighter regulations on CO

2 emissions, the demand for EVs has surged recently. Both battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) are currently regarded as crucial routes to achieving future environmental impact standards and sustainable transport. Rechargeable LIBs have gained global attention since their commercialization by Sony in 1991 [

3]. LIBs were initially developed for commercial use in portable consumer electronics. In recent years, their application has expanded significantly, particularly in EVs [

4], due to their high current density, low self-discharge, long lifespan, and low environmental effect [

5,

6,

7], and versatility across various applications, including portable electronics and EVs. To improve battery lifespan, reliability, safety, and performance, various battery chemistries haven been developed in recent years, and are still currently under development [

8]. As highlighted in [

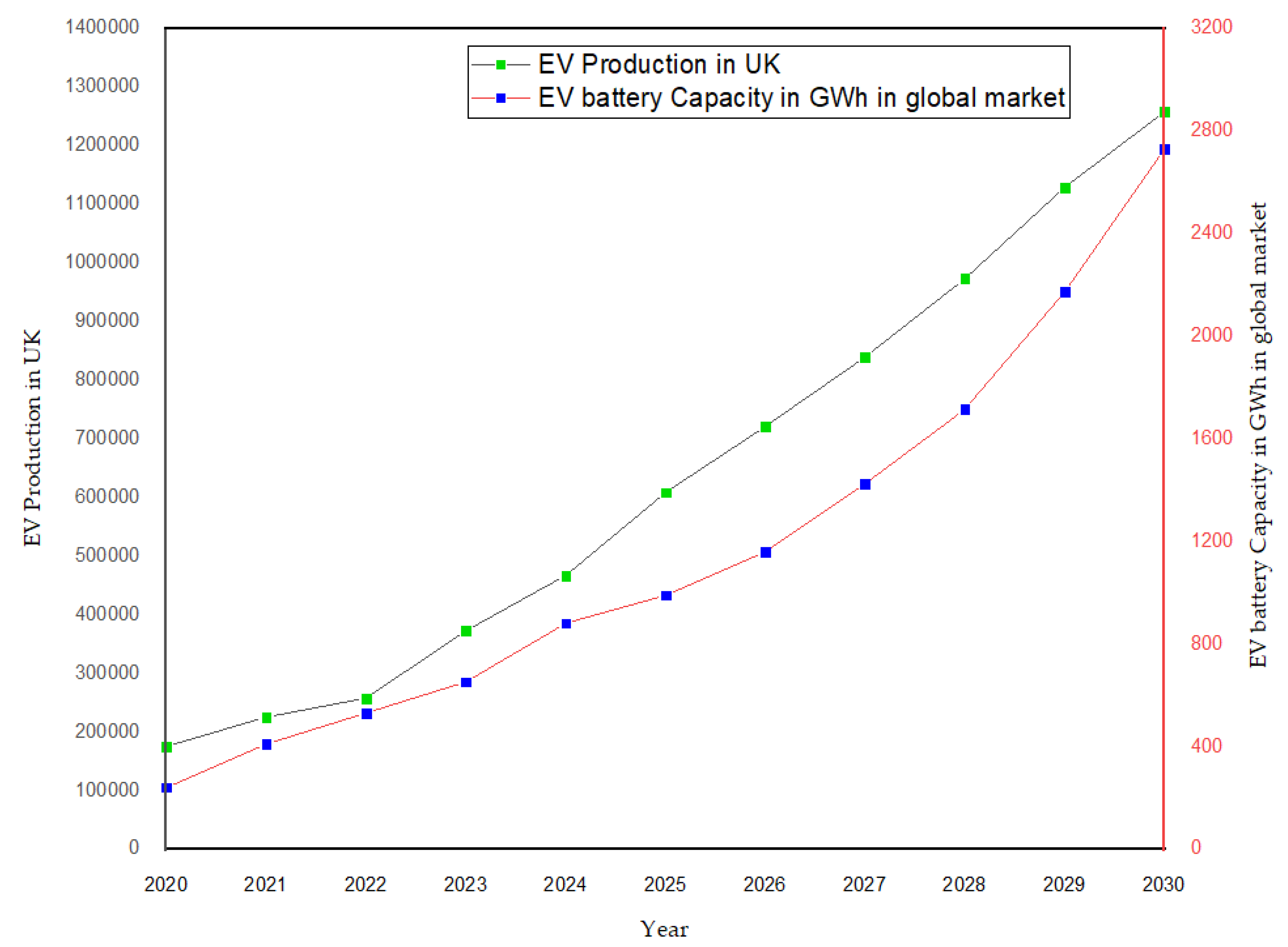

9] the global lithium-ion battery (LIB) market is expanding rapidly, with production capacity rising from 242 GWh in 2020 to 822 GWh in 2024 and projected to reach 991 GWh in 2025 and 2,731 GWh by 2030. This represents an over 11-times surge in LIBs capacity within just a decade. Sales of EVs have been rising at an exponential rate; more than 10 million passenger EVs were sold in 2022, and by 2025, sales are predicted to double [

10]. As the production of EVs continues to rise, the number of retired LIBs from these vehicles also increases, albeit with a significant lag: this leads to a growing need to consider end of life and dismantling/decommissioning for huge numbers of LIBs in the coming years. In particular, efficient upcycling/second life, recycling and disposal solutions are needed to manage this rising waste stream, and potentially recover and re-valorize any reusable materials [

11].

Figure 1 illustrates the projected growth in EV battery production in the UK alongside the global market’s EV battery capacity from 2020 to 2030. This projection highlights the increasing demand for EV batteries driven by the rise of electric vehicle adoption. The UK’s production capacity is expected to expand significantly, supporting the country’s commitment to becoming a leader in sustainable automotive solutions. Meanwhile, global production capacity is set to experience exponential growth, reflecting broader trends in electrification and efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, making EVs a cornerstone of future transportation strategies.

The growing demand for LIBs has increased the need for critical raw materials such as lithium (Li), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co), which are concentrated in specific regions. For example, over 50% of cobalt is sourced from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and about 80% of lithium is controlled by Australia and Chile [

12]. This uneven distribution raises concerns about supply chain stability, with geopolitical factors contributing to price volatility and potential monopolies [

13]. To mitigate these risks, establishing a secondary supply of critical materials through the recycling of spent LIBs from electric vehicles, stationary storage, and manufacturing waste is essential for sustainability [

14]. Materials like copper (Cu) and aluminium (Al) that are easily recyclable are used to make packaging and covers. High-value metals like cobalt (5–20 weight percent), lithium (5–7 weight percent), and nickel (5–7 weight percent) are found in considerable numbers in spent lithium-ion batteries and are found in higher concentrations than in natural ores [

15]. Thus, one of the best waste management solutions for discarded LIBs seems to be recycling processing [

4,

16] Recycling techniques may reduce the need for raw material extraction, which involves high energy consumption and the production of CO

2 emissions, as certain elements will be recovered as high-quality outputs [

17]. EoL battery recycling in high volumes has become a major priority due to the rising number of EVs being produced, the rising number of spent batteries, and environmental concerns. At the EoL stage, inadequate handling and recycling of batteries can significantly amplify environmental and health risks [

18].

Table 1 illustrates the key components of the cell and their corresponding mass fractions, providing a detailed breakdown for reference.

The study and deployment of LIBs is currently of tremendous scientific and technological interest to provide alternatives which help decrease the number of fossil fuel-powered vehicles. Vehicle electrification is an emerging solution to (among other things, such as potential weight reduction and improved powertrain performance) to reduce fossil fuel dependence and the environmental pollution caused by automobile emission [

19]. As the market for LIBs grows, there is an increasing demand to recover and recycle spent LIBs [

20]. Health and environmental risks associated with battery waste could affect society’s ability to grow sustainably [

21]. Therefore, developing efficient and sustainable recycling methods is key to reducing the environmental impact and promoting a circular economy. Recycling not only recovers valuable materials but also reduces the need for raw material extraction, which is energy-intensive and generates significant CO

2 emission [

16,

22,

23]. Recycling opportunities are expected to emerge early, driven by the need to process manufacturing scrap from the battery production process. This scrap includes defective cells, modules, and excess electrode material. During initial scale-up and optimization, production scrap can reach 20-30%, dropping to 5-10% once stabilized [

24]. In the 2020s, production scrap will be the main source of recyclable material [

25], while by the 2030s, EoL batteries will contribute significantly more, by 2040, around 83% of recycled battery material will come from EOL batteries [

26]. Furthermore, a significant portion of EVs are written off annually by insurers due to the inability to assess or repair damaged battery packs, particularly after incidents such as vehicle collisions [

27]. These compromised battery packs, often deemed unserviceable due to safety and performance risks, are classified as non-repairable and must undergo EOL processing for safe material recovery and recycling [

28].

Repurposed LIBs can be a valuable source of future battery materials. By 2030, it is anticipated that more than 5 million metric tons of LIBs will reach the end of their operational lifespan [

29]. The National Academy of Science and Engineering predicts that by 2035, there will be 150 million used EV batteries, up from 50,000 in 2020. This highlights the significance of having a recycling infrastructure and established reuse procedures in place to handle the influx of spent batteries [

30]. This projected surge necessitates the development of extensive recycling infrastructures to recover valuable materials and mitigate the environmental and health hazards posed by improperly managed toxic components. Ensuring sustainable battery management practices is crucial to preventing these burdens from being passed to future generations. Thus, the battery manufacturing industry must embrace a model that prioritizes social responsibility, environmental sustainability, economic feasibility, and innovative practices [

31].

Removing the battery from the vehicle and discarding it is not the best option. In this case, the battery industry has two choices for dealing with the battery’s EoL phase. Redirecting the battery to a second life-use circuit extends its usable life and provides alternate energy storage, lowering the environmental effect per kWh delivered. Transfer the battery to a recycling circuit, where important components, including critical raw materials are reused to make new batteries, lowering the environmental effect of manufacturing [

31]. The rapid deployment of EVs in the market, in combination with reuse and recycling, has the potential to create a circular economy [

32]. Technologies for recycling must be versatile and adaptable to developing methods of manufacturing, especially those that process materials for future battery generations [

33].

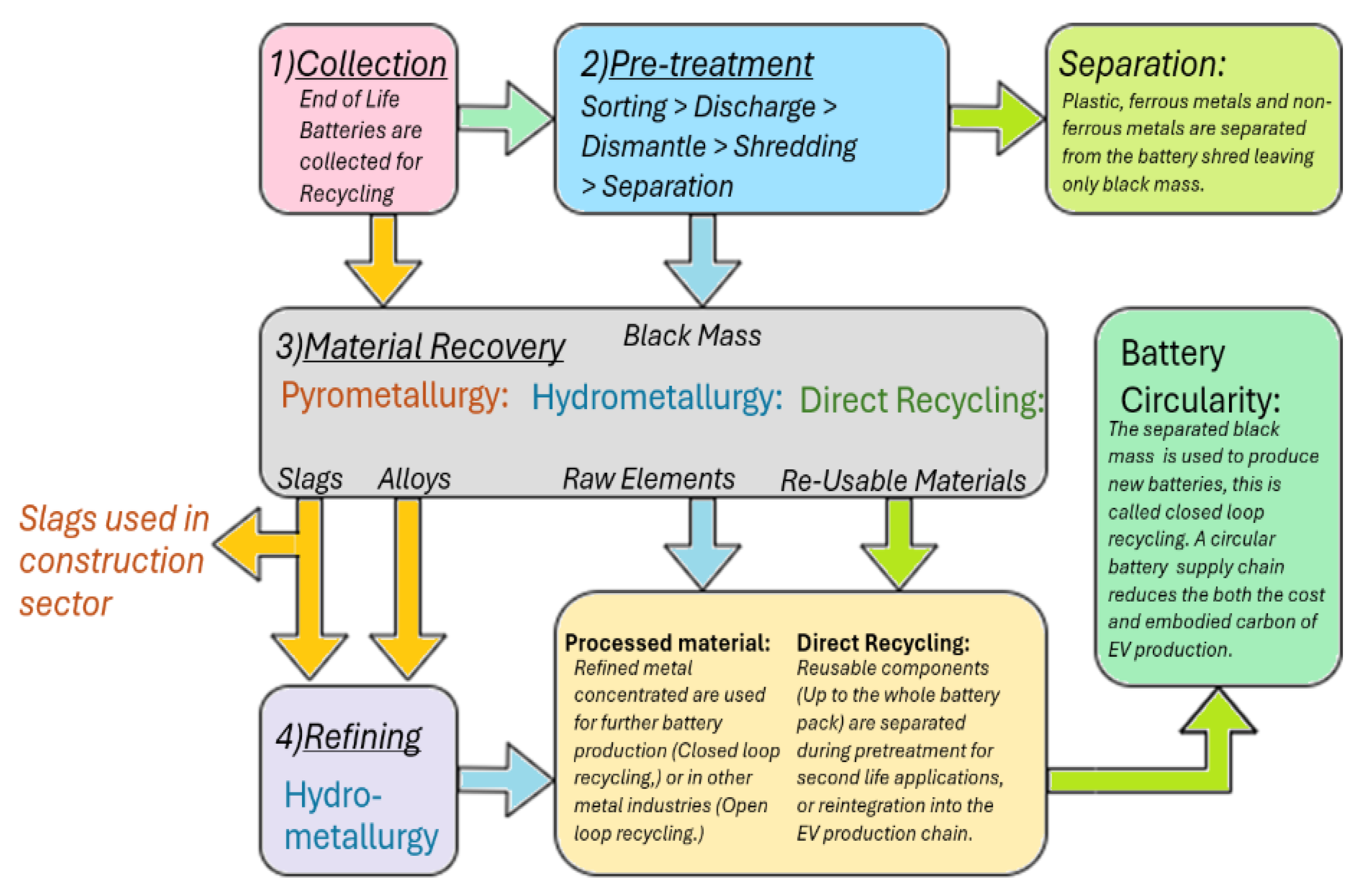

Figure 2 presents a schematic overview of the potential recycling pathways for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs).

Recycling lithium-ion batteries presents a variety of technical, economic, and environmental challenges that need to be addressed. Some of the key challenges are discussed below.

Lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and graphite are among the components that make up lithium-ion batteries. The recycling process is complicated and costly because each of these materials requires a different set of processes[

34,

35].

The variety of battery formulations makes sorting difficulties according to their chemistry a crucial problem when it comes to recycling lithium-ion batteries. Distinct recycling procedures are needed for different battery chemistries, and incorrect sorting can result in lower material recovery, safety hazards, and inefficiencies [

36].

The wide variations in battery designs among manufacturers pose a challenge to the development of standardised recycling procedures. Automatic disassembly and recovery are made more difficult by this irregularity [

37,

38].

Battery systems in electrically powered vehicles store energy in chemical form, with capacities ranging from 20 to 100 kWh and system voltages between 300 and 800 V [

39,

40]. The associated hazards become particularly critical when the battery is disconnected from its operational context, such as during dismantling or recycling procedures [

41].

There are significant regional differences in the laws regarding battery recycling. Large-scale recycling system development is hampered by a lack of international standards and a lack of enforcement of current laws [

42,

43].

Recycling is intended to lessen environmental damage, however the procedures themselves can be harmful and energy intensive.

Each of the existing materials recovery process technologies such as direct recycling process, hydrometallurgical process, and pyrometallurgical process has disadvantages [

15,

44], namely:

Pyrometallurgy process uses a lot of energy and yields fewer valuable materials (it recovers cobalt but not lithium) [

45,

46].

Hydrometallurgy process uses a lot of chemicals, which leads to secondary environmental issues [

47].

Direct recycling process is a promising but undeveloped technique that entails reusing battery components without disassembling them into their component raw materials.

There are concerns regarding the future availability of essential elements like lithium and cobalt as the demand for LIBs keeps increasing, particularly with the popularity of EVs [

48,

49]. Recycling might reduce these supply risks, but the challenges mentioned above need to be overcome.

If LIBs are handled improperly during manufacture or transportation, they may experience thermal runaway, which can result in explosions or fires [

50]. It Is important to follow safety precautions when handling damaged or used batteries.

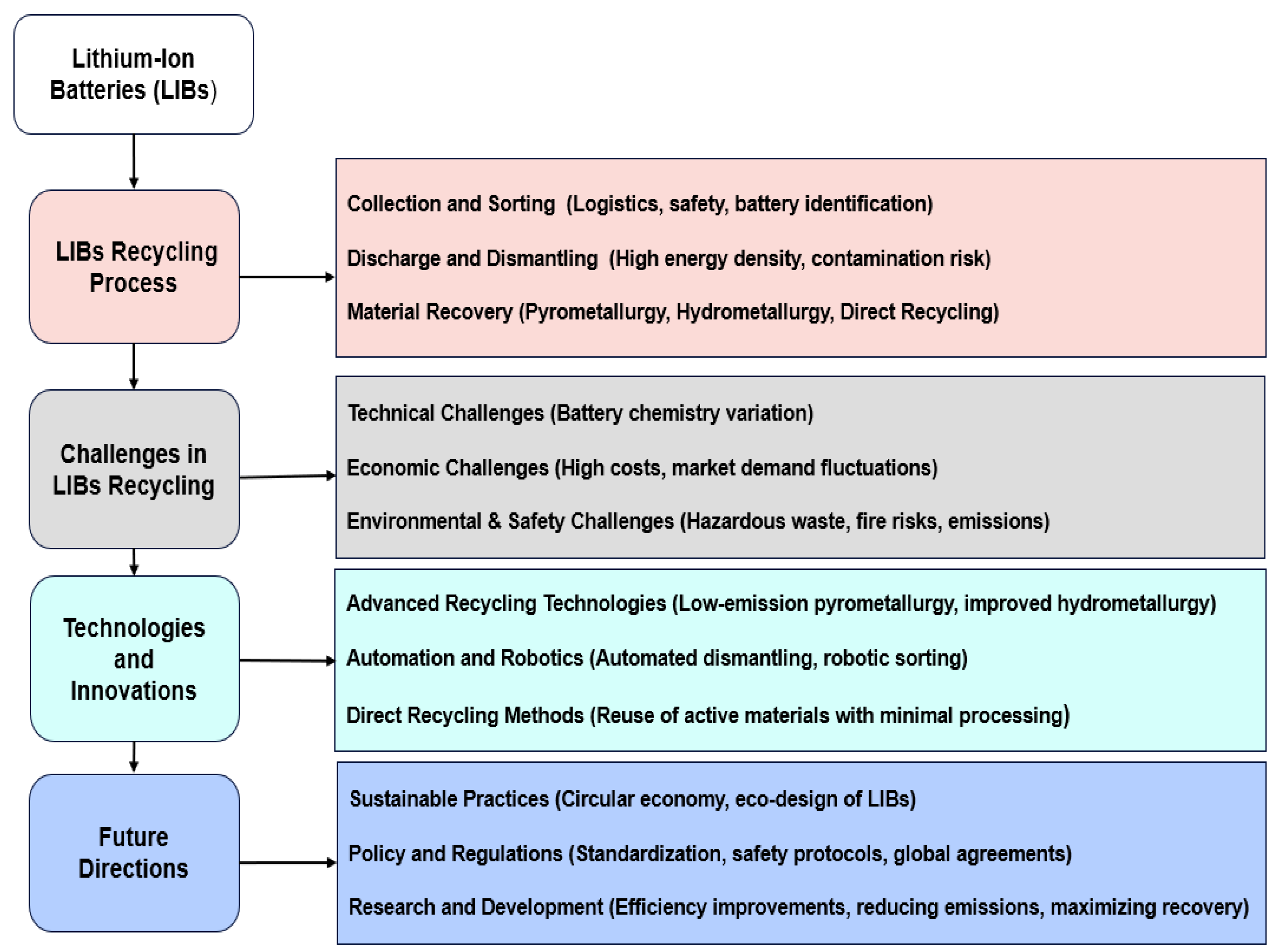

Figure 3 presents a comprehensive flowchart outlining the key challenges and advanced technologies involved in LIBs recycling.

This review paper provides an in-depth review of the high-volume recycling challenges related to LIBs, including the materials recovery procedure, current recycling technologies and based upon the results offering advanced technical insights that set it apart from existing literature. Unlike many reviews that focus on specific aspects such as material recovery or environmental impacts, this paper takes a holistic approach by integrating the challenges associated with the entire lifecycle and recycling process, including LB battery online tracking and condition monitoring, recycling decision support, material recovery, battery discharge management, and automated dismantling. A key distinguishing feature is the inclusion of practical technical data, such as datasets for battery sorting, control algorithms for battery discharge, and methodologies for robotic dismantling. These elements are often underexplored in other reviews, yet they are crucial for advancing the scalability and safety of recycling processes. Additionally, the paper emphasizes the adoption of emerging technologies like automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence, addressing the critical need for efficient and scalable solutions in line with Industry 4.0 advancements. By bridging knowledge gaps, enabling industrial adoption, and providing actionable insights, this paper not only enhances academic understanding but also supports the transition of innovative recycling technologies from research to real-world applications. Its focus on practical data and future-oriented solutions makes it a significant resource for driving progress in sustainable LIB recycling, particularly in the context of the growing demand for electric vehicles.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a comprehensive background review and an in-depth analysis of current developments in the field of electric vehicle (EV) battery recycling, in light of recent commitments to vehicle electrification. This section addresses several critical challenges, including the complexities involved in sorting EV batteries efficiently, managing the discharge of batteries during the scale-up production process, and the technical hurdles associated with dismantling batteries for recycling. These challenges are essential to overcome in order to support the growing demand for EVs and ensure sustainable battery life cycles.

Section 3 explores the groundbreaking innovations reshaping the recycling of EoL EV batteries, focusing specifically on automation technologies and the advancement of sophisticated sorting and disassembly methods. The use of robots in dismantling EV batteries is a key area of innovation, providing significant improvements in safety, efficiency, and precision. Robotic systems can perform complex tasks such as the removal of battery modules, disassembling battery packs, and sorting materials, reducing the need for manual labor and mitigating risks associated with handling hazardous materials. This section also explores the recovery of critical materials from EoL EV batteries, such as lithium, cobalt, and nickel, which are essential for new battery production. Innovations in this area aim to increase recovery rates, reduce costs, and minimize environmental impact, contributing to a more sustainable and circular economy in the automotive industry.

2. Current Challenges and Developments

Growing demand for batteries and their use in a variety of industries, especially in various types of vehicles, are the results of the quick development of LIBs, which has improved manufacturing efficiency and decreased costs for manufacturers [

16,

51]. Reusing, recycling, and repurposing LIBs is essential to creating a sustainable battery economy that can meet demand for LIBs while reducing emissions that have an adverse effect on the climate [

16,

52]. The increasing demand for EVs worldwide due to the urgent need for greener transportation and reduced greenhouse gas emissions has made recycling LIBs more crucial than ever [

53]. These batteries, which are essential to the operation of the majority of EVs, contain lithium, cobalt, and nickel in addition to other valuable and scarce minerals. Improper disposal of these batteries poses significant environmental risks [

23]. Effective recycling reduces the carbon footprint of battery manufacturing and dependency on virgin resources [

54]. It also makes it easier to recover necessary materials and reduces the risk of environmental contamination [

55]. A more sustainable strategy to managing EVs batteries is being made possible by recent advancements in recycling technologies, changing regulatory frameworks, and heightened industry stakeholder collaboration. Because of this, LIB recycling is a fundamental component of the circular economy and is necessary to promote environmental stewardship and the long-term sustainability of electric vehicles.

2.1. Challenges in Sorting EV Batteries

Sorting is the first step in recycling EV batteries, and it is a crucial but difficult procedure. Due to the large variety of battery chemistries, forms, and architectures that have been produced by the quick rate of innovation in EV battery technologies, separating batteries effectively for recycling has become increasingly difficult [

13,

31,

56]. LIBs packs are intricate assemblies consisting of multiple interconnected modules. Each module contains numerous cells, which can be of pouch, prismatic, or cylindrical types [

57]. These cells are typically arranged in diverse parallel-series configurations to achieve the desired electrical output. Common techniques for joining within LIB cells, modules, and packs include welding, wire bonding, and mechanical fastening, ensuring structural integrity and electrical connectivity [

58]. Diversity in chemistry, intricate battery designs, labour-intensive procedures, a lack of standardised labelling, and safety concerns are some of the issues that affect sorting accuracy, which in turn affects the safety, effectiveness, and economic viability of recycling processes [

59,

60].

The chemistry of the battery is a primary criterion in the sorting process and is often complemented by additional parameters such as state of health (SoH), remaining usable life (RUL), and state of charge (SoC). These parameters are crucial for determining the most appropriate recycling pathway for spent LIBs [

61]. However, accurately estimating a battery’s SoH is particularly challenging due to the variability in internal side reactions and external operating conditions [

62]. Batteries must be properly sorted in order to be arranged in storage chambers based on their unique types and conditions, which lowers safety risks associated with damaged and unknown EoL batteries [

63].

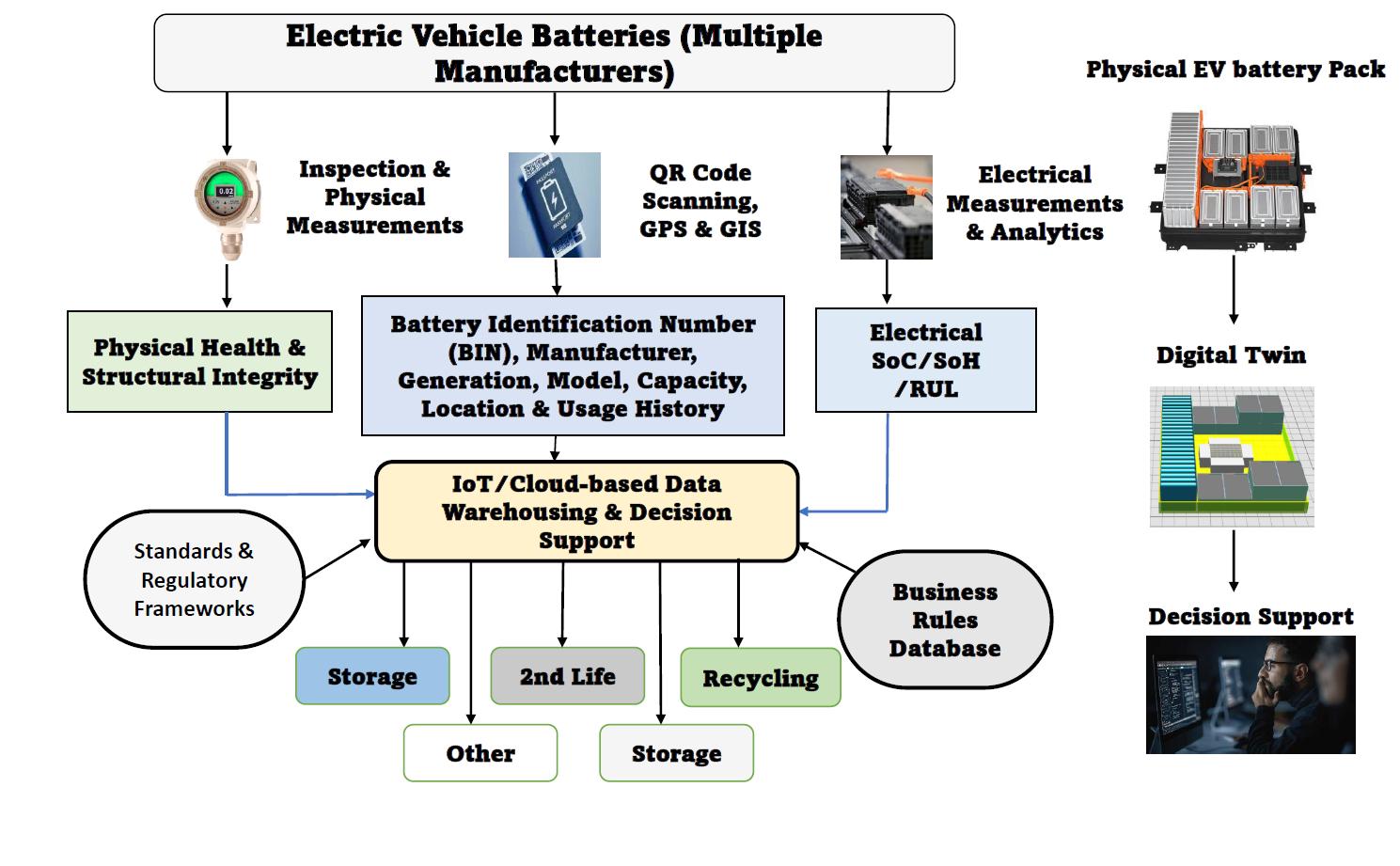

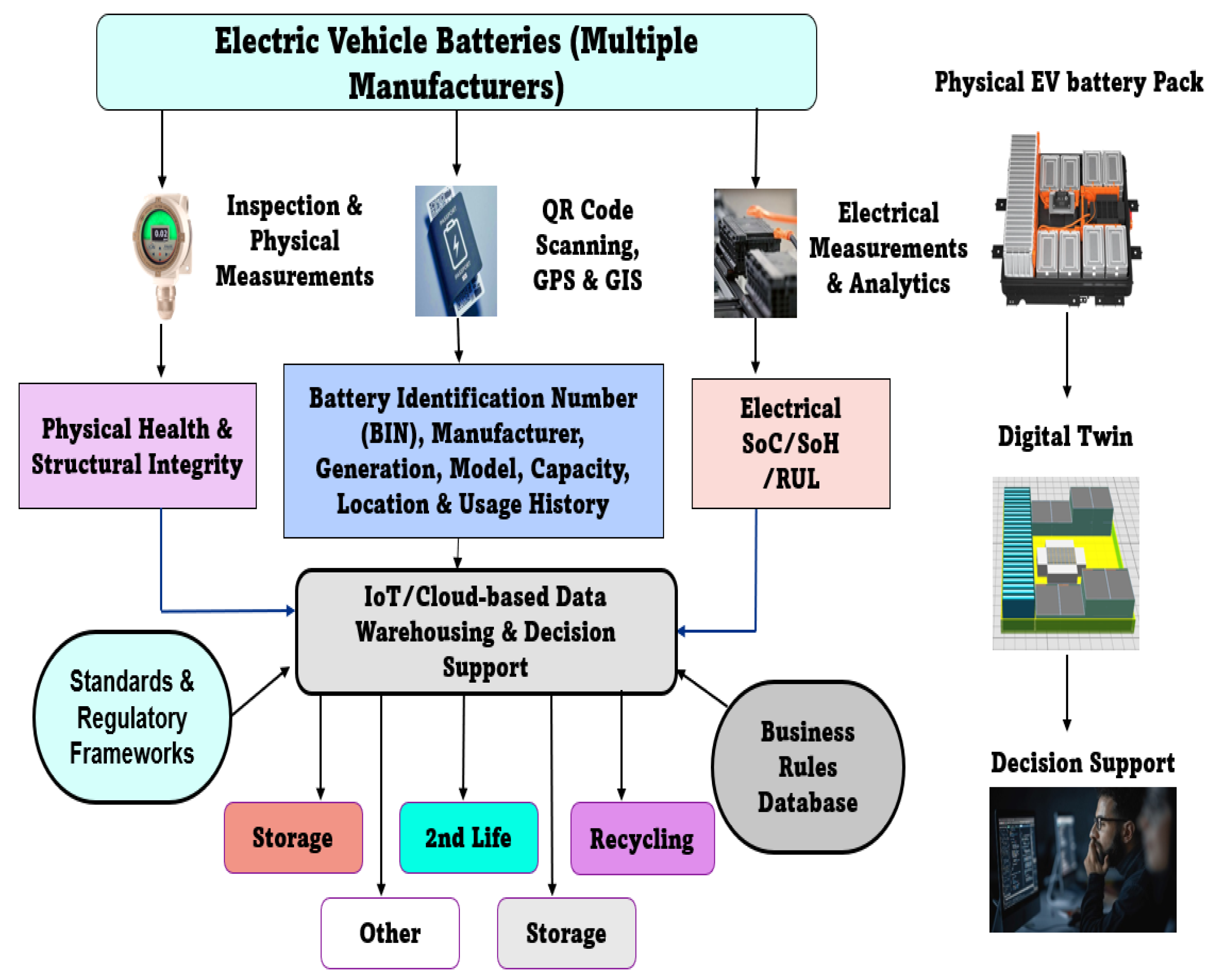

In

Figure 4, a comprehensive framework for cloud-based battery tracking, classification, sorting, and recycling support is presented. A prototype implementation of such a framework is currently developed at Teesside University. Test, analysis, and experience reporting is part of planned future work. [

64].

2.1.1. Diversity in Chemistry and Compatibility Issues

EV batteries use a range of chemistries, including Lithium cobalt oxide (LCO), lithium nickel cobalt aluminium oxide (NCA), lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC), and lithium iron phosphate (LFP), Lithium Manganese Oxide (LMO) and Lithium Titanate (LTO) [

65,

66,

67]. To maximise recovery and reduce contamination, each type requires a different approach to treatment. For example, NMC batteries are valued for their nickel and cobalt content, whereas LFP batteries have fewer high-value elements, which makes recovery using traditional techniques less profitable [

68]. In the recycling process, mixing numerous chemistries can decrease the purity of recovered materials, making it more difficult to re-enter the battery supply chain and reducing profit [

23,

69,

70]. Additionally, there are safety and handling standards for these chemicals; improper sorting increases the risk of fires, particularly when volatile chemicals are inadvertently mixed [

71].

Table 2 compares various characteristics of the chemistries in terms of specific energy, cycle life, thermal runaway, nominal voltage, operating range and applications. [

23,

69,

70]

2.1.2. Complexity of Battery Pack Design

Disassembling EV batteries presents significant challenges due to the wide variety of battery designs [

72], the lack of detailed knowledge about each battery’s condition, and the limited availability of comprehensive design information from original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). This complexity often necessitates adaptive strategies and specialized expertise to navigate unknown variables effectively [

73]. To maximise battery performance and safety, manufacturers frequently create packs with distinctive electronics, cooling systems, module designs, and casing. Because of this diversity, specific disassembly methods are needed, which are time consuming and need for specific abilities and tools. For instance, some packs have welded joints or adhesive coatings that make it difficult to separate cells and modules using conventional disassembly techniques [

37].

The complexity of battery pack design varies significantly across manufacturers, driven by differences in battery chemistry, cell configuration, thermal management strategies, and scalability. For example, Tesla uses cylindrical cells, such as the 18650 and 2170 models, in its battery packs. These cells are arranged in large-scale configurations, with up to 7,000 cells in models like the Model S, allowing for high energy density and efficient use of space. However, this design introduces significant complexity, as each cell requires individual monitoring for voltage balancing, temperature regulation, and charge/discharge optimization. Tesla addresses these challenges with an advanced liquid cooling system that circulates coolant around the cells, ensuring temperature control and enhancing battery longevity.

In contrast, the Nissan Leaf uses pouch cells, which are lighter and more flexible than prismatic cells, allowing for efficient packing and better optimization of space within the battery pack. The 48-module configuration in the Leaf’s battery pack can range from 24 kWh to 62 kWh in the latest models, providing a balance between energy density and system simplicity. However, pouch cells have certain limitations, particularly in their thermal management, as they are more sensitive to temperature fluctuations. The air-cooling system used in the Leaf is less efficient than liquid cooling solutions, affecting the long-term performance in extreme conditions.

The design complexity of EV battery packs is influenced by the choice of cell format, thermal management methods, and overall system integration. Tesla’s cylindrical cells and advanced cooling systems are optimized for high energy density and long-range performance but require complex thermal and management solutions. In contrast, manufacturer like Nissan leaf cost-effective designs with pouch cells and simpler thermal strategies, which offer trade-offs in energy density and range. Each approach reflects the manufacturer’s priorities, whether it is maximizing performance, minimizing costs, or balancing both.

2.1.3. Lack of Standardized Labelling and Identification Systems

The lack of standardised labelling for battery chemistries, structural designs, and manufacturer-specific data is a significant impediment to efficient sorting, the absence of material labelling significantly impedes the quality of recycling processes [

38]. Many battery packs lack unambiguous labelling indicating their composition or even manufacturer origin, which slows sorting and raises the chance of errors. Several initiatives have proposed universal labelling standards, such as the use of QR codes [

74], with information on chemistry, capacity, and recycling instructions, however acceptance has been uneven across sectors and countries . The review by Bai et al. [

75] provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of research and introduces the concept of the Battery Identity Global Passport (BIGP). This concept aims to enhance the recyclability of LIBs by facilitating the separation of components. This can be achieved by identifiable markings, such as labels, QR codes, which simplify the sorting and processing of battery materials during recycling. Without a standardised strategy, recycling facilities are compelled to use human identification methods, which adds time and cost to the sorting process. Standardised labelling has the potential to increase sorting accuracy and efficiency by providing recyclers with crucial information for safe and optimized handling. European governments and battery industry businesses are working to enhance battery and accumulator regulations [

76].

2.1.4. High-Cost, Labor-Intensive Processes

At present, disassembly is typically performed manually and is not non-destructive. Additionally, the absence of proper labelling for materials used in the batteries impedes the ability to conduct high-quality recycling [

38]. Due to technological limitations, in automated systems, current sorting processes remain largely manual, resulting in high labor costs and limited throughput. These limitations arise from the complexity of accurately identifying diverse battery chemistries, the need for precision in handling delicate components, and the difficulty in scaling automation to accommodate various battery types. While advancements in robotic systems offer potential for improved precision and efficiency, their integration into sorting processes is still in the developmental phase, limiting the effectiveness of fully automated solutions in high-volume operations. The sophisticated construction of battery packs necessitates expert workers identifying chemistries, disassembling components, and sorting them by kind, a time-consuming and error-prone task. While robotic solutions and Artificial intelligence (AI) powered sorting systems are being developed, they are still prohibitively expensive and not yet feasible for general usage. Advanced AI technologies capable of distinguishing battery kinds by visual or chemical fingerprints, for example, could speed up sorting, but the needed equipment and cost commitment make it difficult for many facilities to implement. Furthermore, human error in sorting might result in misclassification, lowering recycling efficiency and posing safety issues.

2.1.5. Safety Risks and Environmental Hazards

Sorting EV batteries involves several environmental and safety issues that need to be carefully handled. During handling, batteries may retain residual charge, which could result in short circuits or thermal runaways [

77]. Thermal runaway in LIBs refers to a rapid, uncontrolled increase in temperature caused by a chain reaction of exothermic chemical processes within the battery. This phenomenon occurs when the internal temperature of the battery rises to a critical point, causing the materials inside—such as the electrolyte, anode, and cathode—to decompose and release more heat. As the temperature continues to rise, it accelerates the reaction, leading to potential fire, explosion, or permanent damage to the battery, posing serious safety risks.[

78].

The global commitment to decarbonizing the transportation sector has catalysed significant growth in the electric vehicle (EV) market, which in turn drives an escalating demand for battery raw materials. As the world strives to meet net-zero emissions targets, the demand for key materials such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite is expected to rise substantially. Specifically, between 2021 and 2050, the global demand for lithium is projected to increase 26-times, cobalt 6times, nickel 12-times, and graphite 9-times. This surge in demand underscores the critical need for sustainable sourcing and efficient recycling strategies to meet the future needs of the EV industry while addressing environmental concerns associated with raw material extraction [

51].

Furthermore, several batteries have dangerous components like cobalt, lithium salts, and poisonous electrolytes that, if handled improperly, can cause fires, or release hazardous compounds into the environment. Therefore, to reduce these dangers, sorting procedures must follow strict safety guidelines, such as fireproof enclosure and specialised handling equipment. Inadequate sorting and processing of batteries can result in groundwater and soil contamination, which presents long-term ecological risks [

23]. The economic feasibility of battery recycling is thus further impacted by safety precautions, which increase the difficulty and expense of sorting.

2.1.6. Logistics and Infrastructure Limitations

In many areas, there is insufficient infrastructure to process different types of batteries, which makes sorting logistically difficult. Since recycling centres are frequently centralised, spent EV batteries must be carried across great distances, raising expenses and carbon emissions. Furthermore, sorting efficiency and recycling capacity are decreased by the fact that many facilities lack the necessary equipment to handle a range of battery types. Enhancing sorting procedures, cutting emissions from transportation, and lowering total costs are all possible with the development of regional sorting and recycling infrastructure, but this calls for a large financial outlay and stakeholder collaboration [

31].

2.2. Challenges in discharge EV Batteries (Scaleup Production)

The disassembly of electric vehicle batteries is a pivotal step in the recovery, recycling, and reuse of valuable materials. However, this process is hindered by a lack of standardization, intricate design variations, and safety challenges posed by the uncertain and variable conditions of end-of-life batteries [

79]. Scaling up the discharge of EV batteries presents numerous issues, the most significant of which is the large residual energy that EoL batteries retain, which increases the risk of short circuits, fires, and chemical reactions [

80,

81]. To ensure safety, specialised equipment and protocols are required, which are expensive and difficult to execute on a large scale. The lack of standardisation among battery types complicates matters further, as each kind may require distinct discharge procedures, slowing the process and increasing labour expenses [

82,

83]. The discharge process is often time-consuming and requires a balance of speed and safety, since quick discharge can result in overheating, whilst sluggish discharge diminishes operational efficiency [

84]. Furthermore, large-scale discharge facilities must meet severe environmental and regulatory requirements, manage hazardous waste, and employ experienced workers trained in high-voltage safety, all of which add to expenses [

85]. Limited automation choices, as well as the challenging logistics of transporting and processing multiple batteries, impede scaling efforts and make it difficult to build efficient, safe, and economically sustainable EV battery discharge facilities.

2.3. Challenges in Dismantle EV Batteries

Dismantling EV batteries on a large scale is difficult due to their complicated and non-standard designs [

86]. Each manufacturer has a unique battery design, cell arrangement, and module structure, making it challenging to establish uniform dismantling techniques [

69]. EoL batteries provide significant safety issues due to their high energy and dangerous contents, which can lead to, fires, and chemical exposure [

87]. Dismantling is primarily manual and labour-intensive because existing robotic techniques are not fully ready to properly handle the vast range of battery designs. Scaling up is further complicated by environmental and legal limits, as the process must adhere to stringent handling and disposal regulations for dangerous chemicals such as heavy metals and electrolytes. Furthermore, diversity in battery conditions such as damage, degeneration, or leakage requires flexible handling techniques, which makes automated dismantling difficult to standardise. To manage huge volumes of batteries, parts, and materials, facilities need huge area and logistics [

88]. Finally, the economics of dismantling are difficult; the high costs of labour, specialised equipment, and compliance can surpass the value of materials recovered, making large-scale operations economically unsustainable [

89]. To tackle these obstacles, advancements in automation, improved design standardisation, and efficient safety standards, as well as industry collaboration to ease dismantling and enable more sustainable battery recycling, are required.

3. Innovations in EoL EV batteries recycling

EoL EVs battery recycling innovations are revolutionising the sector by improving sustainability, efficiency, and material recovery [

90]. With the use of advanced recycling processes, such as hydrometallurgical processes and direct recycling, vital materials like nickel, cobalt, and lithium can be recovered with minimal waste and energy. Sorting and processing are optimised through the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, allowing for more accurate battery component identification and classification [

91]. Furthermore, automated robotic technologies improve battery disassembly effectiveness and safety, and new chemical processes are being developed to recover components without producing dangerous by products [

79]. By reusing EV batteries for energy storage solutions, research into second-life uses is also essential to prolonging the batteries’ lifespan. Together, these developments not only make battery recycling more economically feasible, but they also help create a more circular economy by lowering dependency on virgin resources and lessening the negative effects on the environment.

3.1. Automation In Recycling

As EV demand rises, automation in EV battery recycling is becoming more and more vital to improving sustainability and operating efficiency. This innovative technique safely and efficiently disassembles battery packs by using advanced robotic tools, such the ABB IRB 6700. AI powered technologies and automated sorting lines also greatly improve the recovery and classification of precious materials, guaranteeing the best possible use of available resources. Using data analytics and predictive maintenance, these automated systems save downtime, optimise operations, and enhance safety by handling dangerous materials in regulated settings [

92,

93]. Moreover, traceability and regulatory compliance are guaranteed throughout the recycling process via integrated automated systems. Automation has the potential to transform EV battery recycling, making it more effective, efficient, and environmentally friendly, even while obstacles like high upfront costs and the need for skilled employees still exist. Automating the dismantling of batteries could lead to significant cost reductions. For example, the manual disassembly of EV battery packs from manufacturers like Renault, Nissan, Peugeot, Tesla, BAIC, and BYD ranges in cost from US

$ 47 to US

$ 197 per pack. This cost variation primarily arises from differences in the number of modules, screws, fasteners, and welded components [

94]. Transitioning from manual to semi-automated or fully automated recycling could dramatically lower these costs. For instance, the recycling cost for a Nissan Leaf battery could decrease from US

$ 0.64 per kg to just US

$ 0.02 per kg [

94]. Ongoing research into automation, alongside advancements in artificial intelligence, is progressing rapidly, aiming to enable the sorting of batteries based on visual characteristics such as size, colour, and geometry [

95].

There are a few challenges in automating the LIBs disassembly process due to absence of standardisation among battery designs makes it difficult to automate the disassembly of lithium-ion traction batteries, requiring robots to adapt to different configurations [

73,

96]. The wide variation in component geometries within battery packs, coupled with the complexity of differing battery pack designs, presents a major challenge for automating the disassembly process; even between EV battery packs from the same manufacturer [

97]. Additionally, significant differences in component weights complicate the precise and efficient selection of appropriate disassembly tools and robotic platforms [

38]. Another significant challenge arises from non-detachable connections, such as glued or welded joints, including thermal interface materials used to couple battery cells to cooling plates and adhesive seals between the housing cover and tray. Developing specialised tools and processes is essential to automate the separation of these components. Additionally, the limited accessibility of individual parts further complicates the design of an effective automation concept [

95,

98]. Another challenge is hazardous materials and high-voltage components require complex sensors and control systems to limit toxic exposure and prevent fires, safety hazards further hinder automation [

99]. Furthermore, it is challenging for robots to disassemble batteries without damaging the strong adhesives and fasteners used in their production; this necessitates sophisticated manipulation techniques that raise the complexity and expense. Because of these issues, automation is not economically feasible for extensive recycling applications due to its high cost and technical demands. In industrial production, robots are usually programmed for repetitive tasks on fixed objects within structured environments. However, disassembling used EV batteries presents a more complex challenge, as it involves working with less predictable conditions that vary depending on the battery’s state, type, and design. This requires robots to be adaptable to different battery configurations and conditions. To achieve this, higher-level control systems and advanced machine vision are necessary to accommodate the variability in processes and parameters [

72].

Despite these difficulties, an automated disassembly solution that can successfully overcome the associated technological obstacles is desperately needed. These issues must be specifically addressed by creating specialised tools and sophisticated component detection techniques, as well as by structuring the disassembly system to consider the particular needs of battery disassembly. With the anticipated rapid increase in the number of electric vehicles on the road, the volume of battery returns at the end of their life cycle will rise significantly. This highlights the critical need for process automation to ensure a cost-effective and efficient separation process in the future.

3.2. Advance Sorting and Disassembly Techniques

Battery sorting presents a significant challenge and can become a costly component within the battery recycling process [

100]. Currently, battery sorting relies heavily on manual labour, with technicians and staff performing many of the tasks. However, this process demands a deeper understanding of battery chemistries and SoH, which adds complexity [

101]. Given the substantial energy stored in battery packs, they are not suitable for manual disassembly. Their intricate designs, numerous components, varying configurations, and different EoL conditions make automated disassembly the most viable solution. Automation is necessary to ensure safety, efficiency, and scalability in handling these complex systems [

63]. The various battery designs, chemistries, sizes, electrical connections, and packaging formats present ongoing challenges to the development and implementation of automated disassembly solutions, despite the fact that researchers and industry players are actively exploring automated disassembly technologies to improve the efficiency and scalability of the recycling process [

102].

Parameters such as size, weight, and magnetic properties are crucial for developing a basic approach to approximating battery chemistry [

103]. However, the chemistries and internal structures of many batteries are either not disclosed or are obscured due to battery degradation. This makes the chemistry-based sorting process more challenging. To address this, recent studies propose integrating electrochemical models with deep learning and machine learning algorithms to better determine the electrochemical characteristics of the battery [

104]. Recent advances of incorporating AI and machine learning in sorting processes provide innovative approaches to cope with the demanding situations of computerized disassembly [

105]. Understanding the disassembly process through human worker monitoring and analysis can help in developing efficient automation strategies [

106].

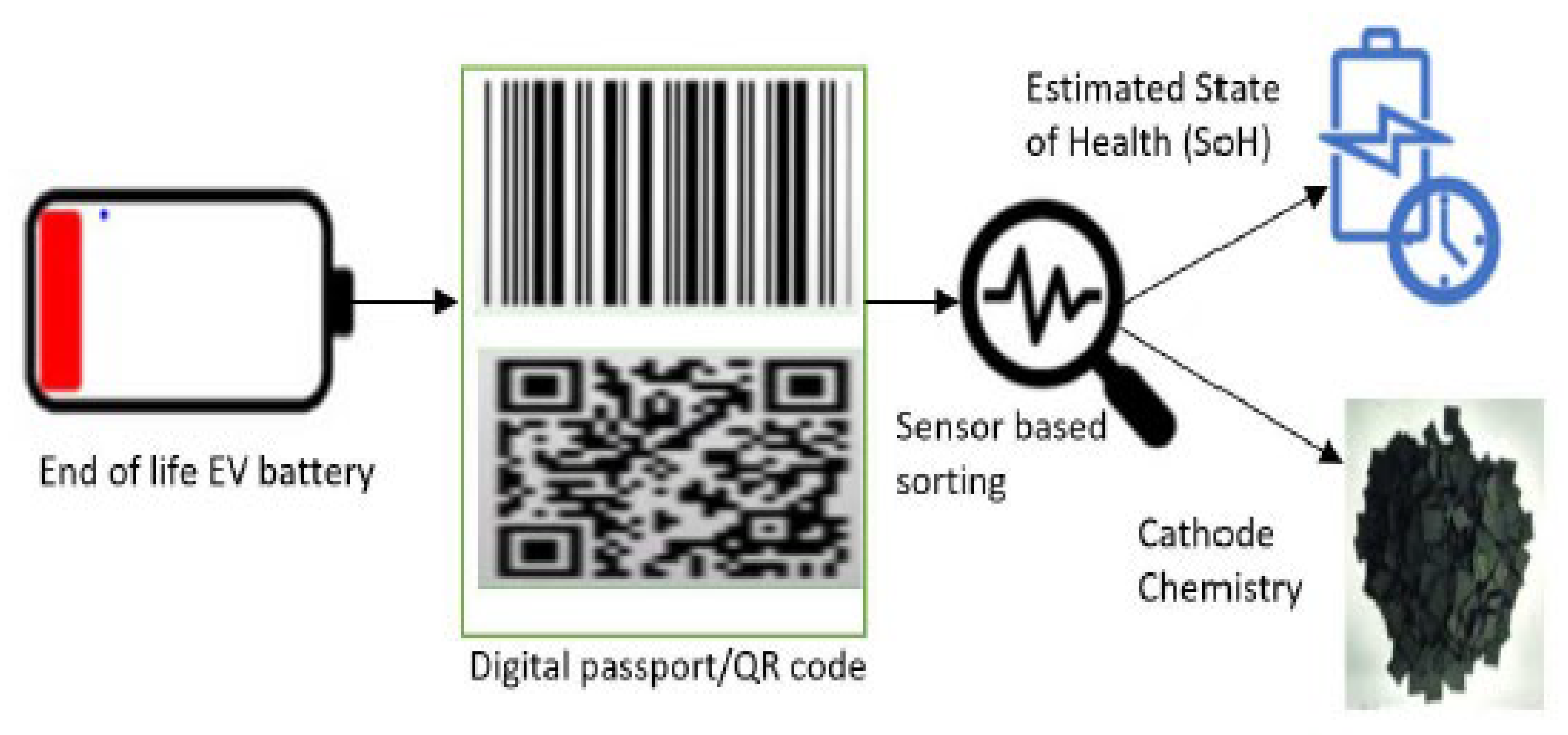

Figure 5 presents a conceptual flowchart for sorting EV batteries based on their SoH and cathode chemistry. One effective solution to address the variability in battery designs is the creation of digital passports for EV batteries. These digital passports would be invaluable for automating processes such as testing and disassembly. They would store critical information, including component dimensions, 3D CAD models, the level of degradation in battery modules, and whether a module is damaged or still reusable. Additionally, sensor-based sorting technologies could be utilized to analyze cathode chemistry and assess the SoH of the battery, further enhancing the sorting and recycling process [

63]. Additionally, AI and machine learning (ML) methodologies can significantly improve the dismantling process through advanced computer vision pipelines and sensor-based sorting technologies. When effectively implemented, these technologies can accelerate the process while reducing time, costs, and safety risks compared to manual methods. AI and ML enhance the accuracy and efficiency of sorting by enabling the recognition of battery components, such as screws and connectors, which allows robots to perform disassembly more effectively. Redwood Materials is an example of a company that has developed efficient methods for recycling lithium-ion batteries. They employ cutting-edge sorting systems, utilizing high precision robots and advanced material recovery processes to optimize recycling efficiency.

3.3. Integration of Artificial Intelligence/ Machine Learning in Recycling Processes

The incorporation of AI and ML in the recycling of EV batteries has revolutionized the industry by significantly enhancing efficiency, sustainability, and resource recovery [

107]. AI technologies leverage ML algorithms, sensors, and data analysis to automate the sorting and identification of various battery types based on their chemistry, size, and state of charge [

108]. AI detection systems utilize advanced visual inspection technologies to evaluate material quality, identify defects, and ensure precise placement during recycling processes [

109]. This automation not only minimizes human labor but also increases the accuracy and speed of sorting, ensuring that batteries are correctly categorized for appropriate processing [

96]. Once sorted, AI optimizes the subsequent recycling processes, such as dismantling and material recovery, by continuously analyzing data and predicting the most effective methods for extracting valuable metals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel [

110]. This results in improved resource utilization, reduced waste, and a more sustainable recycling process. Furthermore, AI plays a crucial role in the logistics of battery collection and transportation, analyzing data on collection routes and facility capacities to optimize the flow of materials. This optimization reduces transportation costs, lowers fuel consumption, and minimizes the environmental footprint of the recycling operations. By enabling higher recovery rates and reducing the need for new raw materials. AI contributes to the circular economy, helping to mitigate the environmental impacts of battery production and disposal. As AI technologies continue to evolve, their potential to further improve the sustainability of EV battery recycling becomes increasingly significant, driving both economic and environmental benefits [

55].

3.4. Recovery of Critical Materials from EoL EV Batteries

Sustainability requires recovering crucial elements from EoL EV batteries because of the growing demand for EVs and the valuable metals they contain, including nickel, manganese, cobalt, and lithium [

95]. Although the production of new batteries depends on these metals, their extraction from natural sources is expensive and harmful to the environment. Recycling and recovering these elements from EoL batteries can help save natural resources, lessen waste and environmental effect, and drastically reduce reliance on raw material mining. Battery packs are safely and methodically disassembled at the start of the recovery process, usually with the aid of sophisticated robotic devices. Because it expedites the disassembly process and reduces human exposure to hazardous chemicals, high-voltage systems, and other possible hazards, automation is essential in this situation [

111]. In this phase, battery packs are disassembled into separate cells and modules, making it possible to efficiently access the vital components inside. Robotic systems with machine vision and sophisticated manipulation skills guarantee accurate handling of battery parts, lowering the possibility of contamination or damage and enhancing the process’s overall safety and effectiveness [

38]. After disassembly, separated battery cells undergo a series of chemical extraction processes to isolate and purify key metals [

68]. The two most common methods are hydrometallurgy and pyrometallurgy [

112,

113,

114]. Alongside these traditional approaches, direct recycling is gaining traction as an innovative technique for recovering essential materials from EOL EV batteries.

Table 3 provides a detailed comparison of various EV battery recycling methods, each with its unique advantages and disadvantages.

3.4.1. Mechanical Treatment of Spent LIBs

Mechanical treatment in EVs Battery recycling is a key procedure that involves physically separating spent batteries to recover valuable materials such as metals, plastics, and critical minerals. The process starts by discharging the batteries to eliminate any residual charge, minimizing the risk of fire or explosion. Once discharged, the batteries are dismantled to remove the outer casings and separate the individual modules or cells. This can be done either manually or using robotic systems, which enhance both efficiency and safety [

111].

The next phase involves shredding, where the battery cells are broken down into smaller pieces. This is followed by size reduction, achieved through milling, or grinding, to create finer materials, especially when separating metals from other components. Various separation techniques, including magnetic separation for ferrous metals, eddy current separation for non-ferrous metals, and gravity separation based on density differences, help extract valuable materials such as aluminum, copper, and iron from plastics, ceramics, and other waste. Additionally, air classification is used to further separate lightweight materials.

The final product is black mass, a powder rich in lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese, which is then processed through hydrometallurgical treatment to recover these valuable metals [

115]. This mechanical treatment is a crucial step in the recycling process, offering an efficient and energy-conscious way to recover essential elements while minimizing the environmental risks linked to battery disposal [

7].

3.4.2. Metallurgical Recycling

Mechanical techniques cannot separate black mass components due to the physical and chemical features of active materials, such as microscopic grain size. These processing steps can be accomplished through metallurgical techniques [

116]. Pyrometallurgy is a high-temperature process [

117,

118] widely used to recover valuable metals such as cobalt, nickel, and copper. In the pyrometallurgical process, which is a conventional method of recovering metal, various thermal processes, including roasting, sintering, smelting, and burning, are performed at regulated high temperatures in order to extract the metallic components from electronic waste [

119]. Although the high-temperature smelting method is relatively simple and productive [

120], its poor Li recovery efficiency and high energy consumption have limited its further application [

121].

The hydrometallurgical process is a chemical-based method for recycling EV batteries that uses selective precipitation and dissolution to extract important metals like nickel, cobalt, and lithium from EoL batteries [

68]. The process of hydrometallurgy delivers a high recovery rate of over 98% for copper, nickel and lithium [

24]. Hydrometallurgy uses a sequence of aqueous (water-based) chemical processes and works at relatively low temperatures, in contrast to pyrometallurgy, which depends on high temperatures. This makes it a more environmentally friendly and energy-efficient technique to recycle EV batteries, particularly as it gives you more control over the extraction of high-purity metals [

122]. Following battery disassembly and shredding into “black mass,” this substance is dissolved in an acidic solution (usually sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid)in a process known as leaching [

123,

124] Metals can dissolve into ions as a result of the materials being broken down. After the metals have dissolved, high-purity metals are isolated for further usage using methods such as solvent extraction and precipitation [

7,

125]. Energy efficiency and accurate metal recovery are two benefits of hydrometallurgy [

115]; nevertheless, controlling acidic waste and increasing recovery rates are still difficulties. Nevertheless, it is a productive method for creating battery-grade materials, enabling a closed-loop system in the electric vehicle sector.

The direct recycling of the active material is a third option, in addition to pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy [

126]. This procedure was created to produce new LIBs by reusing the cathode active material from LIBs recycling. Recovering electrode material from LIBs and then regenerating the recycled electrode material are the two main processes in the method [

127]. Numerous studies have already shown success on a laboratory scale, but industrial application has not yet occurred.

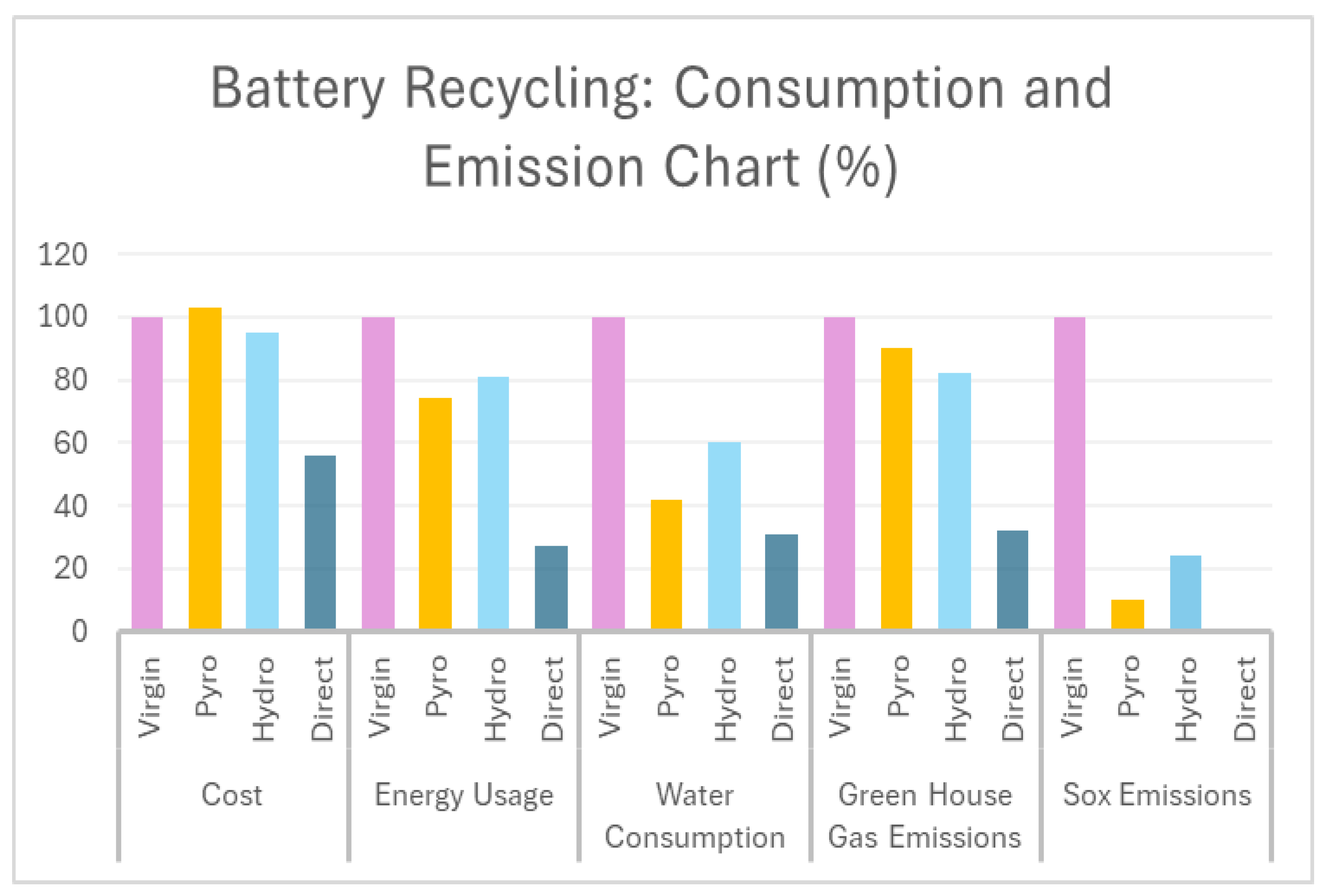

Figure 6 compares the costs and key environmental impacts associated with producing 1 kg of NMC111 from virgin raw materials and through three recycling methods pyrometallurgical, hydrometallurgical, and direct recycling at a large commercial scale (50,000 tons per year). The data reveals that direct recycling results in the lowest environmental and cost impacts across all categories [

128].

4. Discussion

LIBs play a critical role in modern technology, powering applications ranging from portable consumer devices to EVs and large-scale energy storage systems. The rapid growth of EV adoption, driven by stricter decarbonization policies and CO2 emission reduction targets, has intensified the need for affordable EVs and efficient strategies for managing end-of-life batteries.

Battery recycling has emerged as a sustainable and practical solution. Advanced methods allow for the recovery of valuable metals like Ni, Co, Mn, Li and packaging materials such as aluminum (Al) and Cu, reducing dependence on raw material extraction. This not only conserves resources but also lowers energy consumption and environmental emissions. Additionally, efficient recycling processes significantly reduce the costs of new battery production, making EVs more economically viable. The reviewed literature highlights significant challenges in the current EV battery recycling processes, including the wide variation in battery chemistries, complex pack designs, and the absence of standardized labeling systems. These issues increase the complexity of dismantling and sorting operations, leading to higher costs, lower efficiency, and elevated environmental and safety risks. While advancements in robotic dismantling and material recovery technologies show promise, their scalability and efficiency are limited due to the lack of integration with standardized manufacturing and automated sorting systems. This underscores a critical research gap in achieving seamless automation and harmonization across the battery lifecycle, from production to end-of-life recycling.

A key observation is the lack of universal standards in battery pack design, which significantly hinders the efficiency of recycling operations. Proprietary designs and non-uniform configurations complicate automated disassembly. The implementation of standardized modular designs and digital labeling technologies, such as QR codes could facilitate precise identification of battery chemistries and configurations, streamlining sorting and dismantling processes. Moreover, while robotic dismantling technologies have shown potential, they remain in the developmental phase and require further optimization to address the diverse designs and chemistries of battery packs effectively.

Another major gap identified is the absence of integrated data management systems for real-time tracking of battery chemistries and electrical parameters. Establishing comprehensive, database-driven sorting methodologies could significantly enhance the accuracy and efficiency of material recovery processes. Furthermore, leveraging advanced technologies such as digital twin models for process simulation and optimization could enable dynamic adaptation to varying battery designs, improving both safety and efficiency. Addressing these gaps through interdisciplinary research, policy support, and collaboration between manufacturers and recyclers is essential for conserving resources, reducing environmental impacts, and transitioning toward a sustainable circular economy for EV batteries.

Robotic battery dismantling represents a significant innovation in recycling workflows. Robots enhance precision and safety, reducing human exposure to hazardous materials while improving efficiency in disassembling complex battery packs. Currently, robotic dismantling is still in its early stages, requiring substantial advancements to enhance its speed, efficiency, and overall effectiveness. Optimizing this technology will allow for the rapid dismantling of entire battery packs, meeting the demands of large-scale recycling. By combining these advanced methods robotic dismantling, data-driven sorting, and digital twin technology battery recycling is evolving into a critical pillar of the circular economy. Continued innovation in these areas is essential for creating a robust and sustainable infrastructure to meet the growing demands of EV and energy storage industries.

Altilium, a UK-based clean technology innovator, is spearheading the global transition toward a zero-carbon energy future through its proprietary EcoCathode™ technology [

64]. This advanced hydrometallurgical process represents a significant breakthrough in the recycling of EOL LIBs and production waste from gigafactories. Designed to maximize material recovery and minimize environmental impact, EcoCathode™ enables the efficient extraction of critical metals including lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese at high purity levels suitable for direct reuse in the manufacturing of new batteries.

Unlike conventional pyrometallurgical methods, which are energy-intensive and often result in the loss of valuable materials like lithium and manganese, Altilium’s EcoCathode™ process leverages aqueous chemical extraction techniques to achieve superior recovery rates. Specifically, the process recovers over 95% of key metals from EV battery waste streams, preserving their quality for reintegration into the battery supply chain. This ensures a closed-loop recycling system that reduces dependency on raw material mining, which is both environmentally damaging and subject to volatile market conditions.

EcoCathode™ is engineered to address the dual challenges of sustainability and economic viability in battery recycling. The process achieves a 60% reduction in carbon emissions compared to traditional mining and refining of virgin raw materials, making it a more environmentally sustainable solution. Additionally, the process reduces material recovery costs by 20%, offering a competitive edge to manufacturers seeking to lower production expenses without compromising quality or performance [

129].

The scalability of EcoCathode™ further enhances its industrial appeal. Its modular design and adaptability to different battery chemistries, including NMC and LFP, make it a versatile solution for the rapidly evolving energy storage market. By addressing key technical, environmental, and economic barriers, Altilium’s EcoCathode™ technology provides a robust framework for establishing a circular economy within the battery industry, ensuring long-term sustainability and resilience in the transition to clean energy systems.

Altilium Clean Technology is partnering with leading UK automakers to establish a circular economy for EV battery recycling. Their advanced processes focus on maximizing material recovery, minimizing environmental impact, and enabling the reuse of critical metals in new battery production. Planned UK recycling facilities are expected to produce enough sustainable lithium annually to manufacture over 250,000 EV batteries, equivalent to powering more than 80% of the EVs sold in the UK in 2023, significantly reducing reliance on virgin material sourcing [

130].

Through this review and observations, it is evident that improving EV battery recycling requires a combination of standardized manufacturing practices, technological innovation, and policy support. By addressing these challenges, the industry can significantly reduce waste, conserve critical resources, and make EVs more sustainable. Continued research and collaboration between stakeholders will be critical to achieving these goals, ensuring that the EV revolution aligns with environmental and economic sustainability.

5. Conclusion

This review has explored the critical challenges and emerging technologies in EV battery recycling, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable and efficient solutions. Key obstacles such as the diversity in battery chemistries, complex pack designs, the absence of standardized labeling systems, high operational costs, and safety risks continue to hinder progress in recycling processes. Despite these challenges, advancements in robotic dismantling, database-driven sorting, and innovative material recovery techniques show significant potential. However, the lack of industry wide standardization and limited integration of advanced digital tools remain significant barriers to widespread adoption.

Addressing these challenges is essential to improving the economic feasibility and environmental sustainability of battery recycling. By adopting standardized manufacturing practices, integrating automation technologies, and utilizing digital twin models, the recycling process can be transformed into a streamlined and scalable operation. Collaboration between policymakers, manufacturers, and researchers is crucial to developing harmonized frameworks that support innovation in battery lifecycle management and resource conservation.

The digital twin model represents a transformative, technologically advanced approach to EV battery recycling. By integrating automation, real-time monitoring, and chemistry-specific processing, it addresses key challenges associated with resource recovery and sustainability. The model’s ability to simulate and optimize the recycling process offers significant benefits, including improved safety, enhanced material recovery rates, and reduced environmental impact. Ultimately, this innovation contributes to a more sustainable and resource-efficient future for the EV industry.

6. Future Work

To overcome current limitations and drive progress in EV battery recycling, several future research and development directions must be pursued.

First, the development of standardized battery pack designs should be prioritized. Universal guidelines for modular, recycling-friendly pack designs, coupled with digital labeling systems such as Barcode/QR codes, can simplify sorting and dismantling processes. These measures will enable efficient identification of battery chemistries and configurations, reducing complexity during recycling.

Second, significant advancements in robotic dismantling systems are needed. Future efforts should focus on enhancing the speed, precision, and adaptability of robotic technologies to handle diverse battery pack structures. Incorporating machine learning and AI algorithms into robotic systems could further improve their ability to manage variability in design while ensuring safety and precision.

Third, the integration of digital twin technology offers immense potential for optimizing recycling operations. Digital twins can enable real-time simulation, monitoring, and predictive maintenance of recycling systems, increasing efficiency and scalability while reducing operational costs.

Additionally, the implementation of centralized, database-driven sorting systems can enhance material recovery rates. These systems should track battery chemistries, configurations, and lifecycle data, ensuring accurate sorting and efficient recovery of valuable materials. Concurrently, research must focus on developing eco-friendly and cost-effective recycling processes that minimize environmental impacts while achieving high recovery yields for critical materials.

Finally, strong policy and regulatory frameworks are essential to support these advancements. Regulations promoting circular economy practices, extended producer responsibility, and financial incentives for recycling-friendly designs can drive widespread adoption. Collaborative efforts between stakeholders are vital to achieving a sustainable battery recycling ecosystem.

By addressing these priorities, the EV battery industry can overcome existing challenges and establish a robust, resource-efficient recycling framework. These advancements will not only conserve critical materials but also mitigate environmental impacts, contributing to the global shift toward cleaner and more sustainable energy systems.

Supplementary Materials

N/A

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R. M.G.; formal Analysis, S.R; Investigation, S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R., A.B.; M.S., M.G., X.C; visualization, S.R., A.B.; supervision, M.S., M.G., X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

N/A

Acknowledgments

The work described in the paper was carried out in the context of the project entitled ‘Development of new, innovative technologies for electric vehicle battery recycling & low carbon minerals recovery in the Tees Valley’ which was funded by Innovate UK under the Launchpad: Net Zero, CR&D Tees Valley, R2 Competition, Grant No. 10075111. The authors are grateful for the support from the funder and industry partner. Preliminary versions of some of the material presented in this article were presented at the 29th International Conference on Automation and Computing [63,64] in August 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

List of Abbreviations.

Table A1.

List of Abbreviations.

| LIBs |

Lithium-Ion Batteries |

| EoL |

End-of-Life |

| EV |

Electric Vehicle |

| Mn |

Manganese |

| Co |

Cobalt |

| Li |

Lithium |

| Ni |

Nickle |

| LCO |

Lithium Cobalt Oxide |

| NCA |

Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminium Oxide |

| NMC |

Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide |

| LFP |

Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| LMO |

Lithium Manganese Oxide |

| LTO |

Lithium Titanate |

| Cu |

Copper |

| Al |

Aluminium |

| BEVs |

battery electric vehicles |

| PHEVs |

plug-in hybrid electric vehicles |

| BIGP |

Battery Identity Global Passport |

| AI |

Artificial intelligence |

| ML |

Machine learning |

| EC |

Ethylene Carbonate |

| DMC |

Dimethyl Carbonate |

| DEC |

Diethyl Carbonate |

References

- European Parliament, “CO2 emissions from cars: Facts and figures (infographics),” Eur. Parliam., pp. 1–6, 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20190313STO31218/co2-emissions-from-cars-facts-and-figures-infographics.

- C. R. Hung, S. Völler, M. Agez, G. Majeau-Bettez, and A. H. Strømman, “Regionalized climate footprints of battery electric vehicles in Europe,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 322, no. August, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Service, “Lithium-ion battery development takes Nobel,” Science (80-. )., vol. 366, no. 6463, p. 292, 2019. [CrossRef]

- B. K. Biswal, B. Zhang, P. Thi Minh Tran, J. Zhang, and R. Balasubramanian, “Recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries for a sustainable future: recent advancements,” Chem. Soc. Rev., vol. 53, no. 11, pp. 5552–5592, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Cognet, J. Condomines, J. Cambedouzou, S. Madhavi, M. Carboni, and D. Meyer, “An original recycling method for Li-ion batteries through large scale production of Metal Organic Frameworks,” J. Hazard. Mater., vol. 385, no. November 2019, p. 121603, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Cui, L. Wang, Q. Li, and K. Wang, “A comprehensive review on the state of charge estimation for lithium-ion battery based on neural network,” Int. J. Energy Res., vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 5423–5440, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Windisch-Kern et al., “Recycling chains for lithium-ion batteries: A critical examination of current challenges, opportunities and process dependencies,” Waste Manag., vol. 138, pp. 125–139, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. SHEIKH, M. Rashid, and S. Rehman, “Robust testing requirements for Li-ion battery performance analysis,” Renew. Energy Gener. Appl., vol. 43, pp. 197–204, 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Estimated Capacity of Lithium-Ion Batteries Placed on the Global Market in 2020 with Forecast for 2021 through 2030 (in Gigawatt Hours).” Accessed: Dec. 12, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1246914/capacity-of-lithium-ion-batteries-placed-on-the-global-market/.

- I.- International Energy Agency, “Global EV Outlook 2023: Catching up with climate ambitions,” 2023, [Online]. Available: www.iea.org.

- A. Pražanová, V. Knap, and D.-I. Stroe, “Literature Review, Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles, Part II: Environmental and Economic Perspective,” Energies, vol. 15, p. 7356, 2022.

- A. Zeng et al., “Battery technology and recycling alone will not save the electric mobility transition from future cobalt shortages,” Nat. Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, 2022,. [CrossRef]

- M. Chen et al., “Recycling End-of-Life Electric Vehicle Lithium-Ion Batteries,” Joule, vol. 3, no. 11, pp. 2622–2646, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Yu et al., “Current Challenges in Efficient Lithium-Ion Batteries’ Recycling: A Perspective,” Glob. Challenges, vol. 6, no. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., “Recent progress on the recycling technology of Li-ion batteries,” J. Energy Chem., vol. 55, pp. 391–419, 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Zanoletti, E. Carena, C. Ferrara, and E. Bontempi, “A Review of Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling: Technologies, Sustainability, and Open Issues,” Batteries, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- EuRIC AISBL, “Metal Recycling Factsheet,” EuRIC AISBL – Recycl. Bridg. Circ. Econ. Clim. Policy, p. 8, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/knowledge/metal-recycling-factsheet-euric.

- Y. Nie, Y. Wang, L. Li, and H. Liao, “Literature Review on Power Battery Echelon Reuse and Recycling from a Circular Economy Perspective,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 20, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. RASHID, M. Sheikh, and S. Rehman, “Li-ion batteries life cycle from electric vehicles to energy storage,” Renew. Energy Gener. Appl., vol. 43, pp. 223–229, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Carey, “JLR, Altilium to test EV batteries made with recycled materials.” Accessed: Dec. 22, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/jlr-altilium-test-ev-batteries-made-with-recycled-materials-2024-09-26/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- S. S. Gloria Kang GJ, Ewing-Nelson SR, Mackey L, Schlitt JT, Marathe A, Abbas KM, “乳鼠心肌提取 HHS Public Access,” Physiol. Behav., vol. 176, no. 1, pp. 139–148, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Marchese et al., “An Overview of the Sustainable Recycling Processes Used for Lithium-Ion Batteries,” Batteries, vol. 10, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Mrozik, M. A. Rajaeifar, O. Heidrich, and P. Christensen, “Environmental impacts, pollution sources and pathways of spent lithium-ion batteries,” Energy Environ. Sci., vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 6099–6121, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Leong, “Developing a UK lithium-ion battery recycling industry,” no. 20, pp. 1–16, 2024.

- “Battery production scrap to be main source of recyclable material this decade.” [Online]. Available: https://source.benchmarkminerals.com/article/battery-production-scrap-to-be-main-source-of-recyclable-material-this-decade.

- J. Fleischmann et al., “Battery 2030: Resilient, sustainable, and circular,” pp. 1–18, 2023.

- S. M. Nick Carey, Paul Lienert, “Insight: Scratched EV battery? Your insurer may have to junk the whole car.” Accessed: Dec. 10, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/scratched-ev-battery-your-insurer-may-have-junk-whole-car-2023-03-20/.

- C. Staff, “Electric car battery recycling: what happens to the dead batteries?” Accessed: Dec. 09, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.carwow.co.uk/blog/ev-battery-recycling-what-happens-to-dead-batteries#gref.

- Propulsion Quebec, “Developing a promising sector for Quebec’s economy Lithium-ion Battery Sector,” no. April, 2019.

- Circular Economy Initiative Germany, “Resource-Efficient Battery Life Cycles - Driving Electric Mobility with the Circular Economy,” 2020.

- A. Beaudet, F. Larouche, K. Amouzegar, P. Bouchard, and K. Zaghib, “Key challenges and opportunities for recycling electric vehicle battery materials,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 14, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kotak et al., “End of electric vehicle batteries: Reuse vs. recycle,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 8, pp. 1–15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Fan et al., “Sustainable Recycling Technology for Li-Ion Batteries and Beyond: Challenges and Future Prospects,” Chem. Rev., vol. 120, no. 14, pp. 7020–7063, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Toro et al., “A Systematic Review of Battery Recycling Technologies: Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects,” Energies, vol. 16, no. 18, pp. 1–24, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Sojka, Q. Pan, and L. Billmann, “Comparative study of Li-ion battery recycling processes,” ACCUREC Recycl. GmbH, pp. 1–54, 2020.

- Pengwei Li, Shaohua Luo, Yicheng Lin, Jiefeng Xiao, Xiaoning Xia, Xin Liu, Li Wang and Xiangming Heao, “Fundamentals of the recycling of spent lithium-ion batteries,” Chem. Soc. Rev., 2024.

- D. Klohs, C. Offermanns, H. Heimes, and A. Kampker, “Automated Battery Disassembly—Examination of the Product- and Process-Related Challenges for Automotive Traction Batteries,” Recycling, vol. 8, no. 6, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Zorn et al., “An Approach for Automated Disassembly of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs and High-Quality Recycling Using Computer Vision, Labeling, and Material Characterization,” Recycling, vol. 7, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Kwade, W. Haselrieder, R. Leithoff, A. Modlinger, F. Dietrich, and K. Droeder, “Current status and challenges for automotive battery production technologies,” Nat. energy, 2018. [CrossRef]

- C. Iclodean, B. Varga, N. Burnete, D. Cimerdean, and B. Jurchiş, “Comparison of Different Battery Types for Electric Vehicles,” IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 252, no. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Kwade and J. Diekmann, Recycling of Lithium-Ion Batteries, 1st ed. Springer Cham, 2018. [CrossRef]

- O. Velázquez-Martínez, J. Valio, A. Santasalo-Aarnio, M. Reuter, and R. Serna-Guerrero, “A critical review of lithium-ion battery recycling processes from a circular economy perspective,” Batteries, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 5–7, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Islam and U. Iyer-Raniga, “Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling in the Circular Economy: A Review,” Recycling, vol. 7, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. He et al., “A Comprehensive Review of Lithium-Ion Battery (LiB) Recycling Technologies and Industrial Market Trend Insights,” Recycling, vol. 9, no. 1, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A.B. Botelho Junior, S. Stopic, B. Friedrich, J. A. S. Tenório, and D. C. R. Espinosa, “Cobalt recovery from li-ion battery recycling: A critical review,” Metals (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 1–25, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Zhou, D. Yang, T. Du, H. Gong, and W. Bin Luo, “The Current Process for the Recycling of Spent Lithium Ion Batteries,” Front. Chem., vol. 8, no. December, pp. 1–7, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Nkuna, G. N. Ijoma, T. S. Matambo, and N. Chimwani, “Accessing Metals from Low-Grade Ores and the Environmental Impact Considerations: A Review of the Perspectives of Conventional versus Bioleaching Strategies,” Minerals, vol. 12, no. 5, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Das, A. Kleiman, A. U. Rehman, R. Verma, and M. H. Young, “The Cobalt Supply Chain and Environmental Life Cycle Impacts of Lithium-Ion Battery Energy Storage Systems,” Sustain. , vol. 16, no. 5, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. M. P.-O. Victor Osvaldo Vega-Muratalla, César Ramírez-Márquez, Luis Fernando Lira-Barragán, “Review of Lithium as a Strategic Resource for Electric Vehicle Battery Production : Availability, Extraction, and Future Prospects,” 2024.

- Z. Chen, A. Yildizbasi, Y. Wang, and J. Sarkis, “Safety Concerns for the Management of End-of-Life Lithium-Ion Batteries,” Glob. Challenges, vol. 6, no. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Jannesar Niri, G. A. Poelzer, S. E. Zhang, J. Rosenkranz, M. Pettersson, and Y. Ghorbani, “Sustainability challenges throughout the electric vehicle battery value chain,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 191, no. January 2023, p. 114176, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Ahmed, F. Hasan, S. S. Kabir, and A. S. Khan, “Sustainable Management of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries : The Role of Reverse Logistics in the Automotive Sector †,” 2024.

- J. A. Llamas-Orozco et al., “Estimating the environmental impacts of global lithium-ion battery supply chain: A temporal, geographical, and technological perspective,” PNAS Nexus, vol. 2, no. 11, pp. 1–16, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Breiter, M. Linder, T. Schuldt, G. Siccardo, and N. Vekic, “202303_McKinsey_Battery recycling takes the driver’s seat,” McKinsey Co., no. March, 2023.

- B.I Chigbu, “Advancing sustainable development through circular economy and skill development in EV lithium-ion battery recycling: a comprehensive review,” Front. Sustain., vol. 5, no. June, pp. 1–16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Doose, J. K. Mayer, P. Michalowski, and A. Kwade, “Challenges in ecofriendly battery recycling and closed material cycles: A perspective on future lithium battery generations,” Metals (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 1–17, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Kerem Eren, K. Aras, T. Gucukoglu, K. Erhan, and E. Ipek, “Effects of Cell and Module Configuration on BatterySystem in Electric Vehicles,” Int. J. Eng. Technol., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 143–152, 2018.

- W. Cai et al., “Analysis of Li-Ion Battery Joining Technologies*,” 2017.

- A.N. Patel et al., “Lithium-ion battery second life: pathways, challenges and outlook,” Front. Chem., vol. 12, no. April, pp. 1–21, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. D. J. Harper et al., “Roadmap for a sustainable circular economy in lithium-ion and future battery technologies,” JPhys Energy, vol. 5, no. 2, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Johansson et al., “Challenges and opportunities to advance manufacturing research for sustainable battery life cycles,” Front. Manuf. Technol., vol. 4, no. August, pp. 1–19, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, X. Zhang, K. Li, G. Zhao, and Z. Chen, “Perspectives and challenges for future lithium-ion battery control and management,” eTransportation, vol. 18, no. June, p. 100260, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Rehman et al., “A Review of the EoL EV Batteries Sorting and Disassembly Challenges,” 2024 29th Int. Conf. Autom. Comput., pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. Short et al., “Technologies for EoL EV Batteries Recycling : Assessment and Proposals,” 2024 29th Int. Conf. Autom. Comput., pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. S. E. Houache, C. H. Yim, Z. Karkar, and Y. Abu-Lebdeh, “On the Current and Future Outlook of Battery Chemistries for Electric Vehicles—Mini Review,” Batteries, vol. 8, no. 7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J.-J. Marie, “Developments in Lithium-Ion Battery Cathodes,” Faraday Insights-Issue, vol. 18, no. 18, pp. 1–12, 2023.

- “BU-205: Types of Lithium-ion.” Accessed: Oct. 30, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://batteryuniversity.com/article/bu-205-types-of-lithium-ion#google_vignette.

- K. Davis and G. P. Demopoulos, “Hydrometallurgical recycling technologies for NMC Li-ion battery cathodes: current industrial practice and new R&D trends,” RSC Sustain., vol. 1, no. 8, pp. 1932–1951, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D.L. Thompson et al., “The importance of design in lithium ion battery recycling-a critical review,” Green Chem., vol. 22, no. 22, pp. 7585–7603, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Vegh, A. K. Madikere Raghunatha Reddy, X. Li, S. Deng, K. Amine, and K. Zaghib, “North America’s Potential for an Environmentally Sustainable Nickel, Manganese, and Cobalt Battery Value Chain,” Batteries, vol. 10, no. 11, 2024. [CrossRef]