1. Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks as the third leading cause of both cancer incidence and cancer-related mortality worldwide[

1]. At diagnosis, approximately 25% of patients are diagnosed with stage IV CRC with synchronous metastases, and nearly 50% of all patients eventually develop liver metastases; 90% will ultimately die due to metastatic disease[

2]. Surgical resection of colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM) remains the traditional curative treatment, achieving 5-year survival rates up to 50%, offering the potential for a cure, with approximately 25% of patients remaining disease-free at 5 years[

3]. However, for roughly 85% of stage IV CRC patients, liver disease is deemed unresectable at presentation, leading to palliative systemic chemotherapy as the primary treatment[

4,

5,

6]. Unfortunately, this approach yields a 5-year overall survival rate of just 10% from the initiation of first-line chemotherapy[

7], underscoring the urgent need for alternative therapeutic options.

Locoregional therapies such as radioembolization (TARE), external radiation therapy (SBRT), Hepatic Artery Infusion (HAI) Pump Chemotherapy and thermal ablation like radiofrequency ablation or microwave ablation have been integral to the management of primary and metastatic liver tumors[

8,

9]. While these approaches are widely practiced, they are not without limitations, including their invasive nature, substantial radiation exposure, restricted real-time visualization of therapeutic effects, and inconsistent success in achieving reliable local tumor control[

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. These approaches are usually used as a palliative alternative.

Histotripsy is an innovative, non-invasive technique that employs precisely controlled acoustic cavitation to disrupt tumors without using heat or ionizing radiation and allowing real-time visualization of the tissue effect. Preclinical studies by Worlikar et al. have highlighted its’ effectiveness in achieving tumor ablation and reducing both local progression and metastatic spread in rodent models[

17,

18]. These encouraging findings sparked research interest in human clinical studies. The THERESA trial evaluated the use of histotripsy in eight patients with a total of 11 liver malignancies, including seven CRLMs in five patients. The trial achieved its primary endpoint, demonstrating acute technical success in all 11 tumors treated with histotripsy. Technical success was defined as creating a targeted zone of tissue destruction within the planned volume, as confirmed by MRI one day post-procedure. Importantly, no adverse events were deemed probably or definitely related to the device, underscoring the excellent safety profile of histotripsy[

19]. The #HOPE4LIVER trial involved 44 participants with 49 liver tumors, including 10 cases of CRLM. The study achieved a 95% technical success rate in tumor ablation, significantly exceeding the predefined performance goal of 70%. Major procedure-related complications were observed in approximately 7% of cases, which is within acceptable safety margins for liver-directed therapies[

20]. These results further highlight histotripsy’s potential as a safe and effective non-invasive treatment option for liver malignancies. Furthermore, histotripsy preserves collagenous structures, allowing direct treatment of major structures such as the portal or hepatic veins[

21]. Finally, there is a proposed immune-priming effect to histotripsy mediated in murine models by CD4/CD8+ T-cells, which in-turn leads to off-target immunologic destruction of tumors even that have received no direct or systemic therapy[

22].

2. Patient Selection

At our institution, all patients with liver tumors are carefully evaluated through a comprehensive, multidisciplinary weekly liver tumor board. This board consists of a diverse team of specialists, including liver transplant surgeons, liver surgical oncologists, interventional radiologists, abdominal radiologists, medical oncologists, and hepatologists. These collaborative discussions allow for a thorough assessment of each patient’s case, ensuring the most appropriate and individualized treatment recommendations.

Histotripsy is considered based on the collective expertise of the tumor board, with the procedure performed at the discretion of the procedural and surgical providers delivering the therapy. Patients are deemed suitable candidates for histotripsy at our institution under the following circumstances:

1. Ineligibility with current surgical or non-surgical treatment: Patients who are not candidates for curative-intent surgical or non-surgical treatment due to significant medical comorbidities or limited function of the liver that makes it unsafe or impractical.

2. Unresectable disease with palliative intent: Patients with unresectable liver tumors not responsive to current systemic or liver directed therapy.

3. Downstaging or bridging to liver transplantation: Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who require tumor downstaging to meet transplantation criteria or as a bridging therapy to reduce tumor progression while awaiting liver transplantation. This approach has been included as a recommended treatment by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS).

This patient-centered and multidisciplinary approach ensures that histotripsy is integrated thoughtfully into treatment protocols, balancing innovation with safety, clinical evidence, and individual patient needs.

3. How We Do It

3.1. Pre-Treatment Protocol

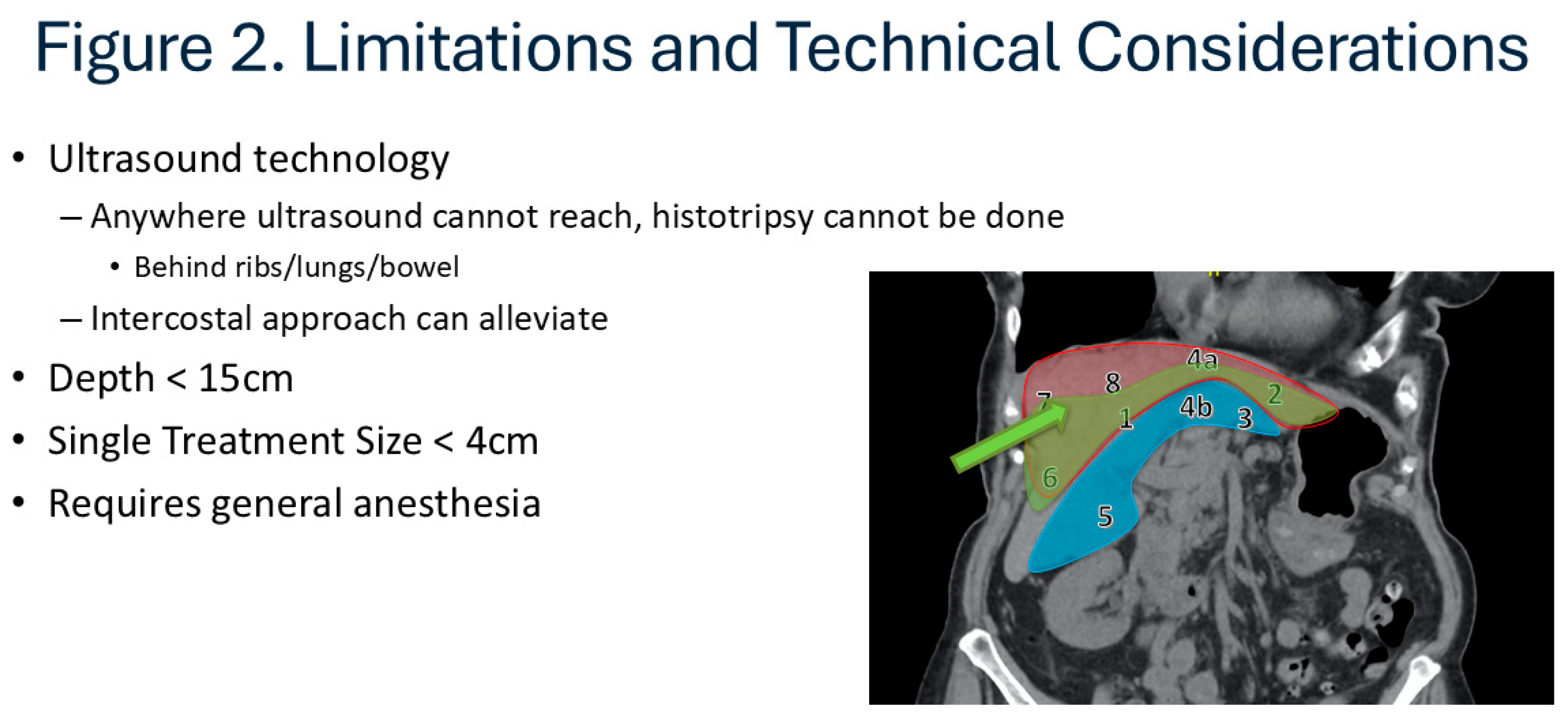

Patients are referred for histotripsy as previously described. They are initially reevaluated whether currently established surgical or non-surgical treatment options are available. Detailed description of the advantages and disadvantages of histotripsy is given to the patient before consideration. Once the patient decides to proceed with histotripsy, candidacy is assessed first using this cross-sectional imaging. At present, application of histotripsy is limited by bone, bowel gas, and depth which makes certain anatomic locations potentially prohibitive. (Figure) Subcostal approach are easier to target but the area it can cover is limited, and it can be expanded using trans-costal approach. However, most commonly the very superior lesions in the dome of the liver or deep lesions in the caudate lobe are difficult to target and may not be considered candidate. A crude guide to lesions that are anatomically favorable, intermediate, or unlikely to be feasible is provided [

Figure 1]. Ultrasound is performed to assess eligibility for histotripsy. The visibility, echogenicity, depth, method of approach (subcostal vs trans-costal), and angle of approach are described in detail by the ultrasonographer to evaluate the likelihood successful treatment and graded there upon. Dedicated ultrasonography to evaluate candidacy of histotripsy helps rule out tumors that are not targetable, but it does not mean the tumors seen on ultrasonography will definitively be treatable since the acoustic window of histotripsy does not completely align with the widow observed during ultrasound evaluation. We have developed a standard template for best communication between teams and to get objective data for future studies. [

Supplement 1]. Once eligibility is confirmed, patients proceed with a comprehensive pre-procedure workup designed to establish baseline assessments for accurate monitoring of treatment outcomes. This thorough evaluation focuses on tumor characteristics and overall health to optimize treatment planning.

3.1.1. Laboratory Tests

Patients undergo a complete blood count (CBC) and a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) to assess their overall health and liver function. Tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) for colorectal liver metastasis, CA19-9 for cholangiocarcinoma, CA-125 for ovarian cancer and AFP for hepatocellular carcinoma, are measured to provide additional information.

3.1.2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

A blood sample is collected to analyze ctDNA, a minimally invasive biomarker that can detect genetic alterations and tumor burden. ctDNA levels offer valuable insight into the molecular profile of the tumor and can serve as an early indicator of treatment response or recurrence. ctDNA has been well-described by our group in management of CRLM and other liver malignancies, including pre-operative selection and post-operative surveillance[

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. While novel, we do hope that ctDNA will serve in similar capacity surrounding histotripsy.

3.2. Procedure

Histotripsy is performed using the HistoSonics Edison System (HistoSonics, Plymouth, Minnesota, USA) under general anesthesia in an operating room setting. The whole procedure lasts approximately 2-4 hours, of which, 10-45 minutes are expected to be actual treatment time. Patients are initially positioned supine on the table to perform ultrasonography for pre-procedure imaging to allow optimal access to the target tumor. Trans-costal treatments are most frequently done in a “lazy lateral” position while sub-costal treatments are performed supine. The precise location and dimensions of the tumor are mapped with the HistoSonics system and targeting algorithms in the system optimize the delivery of focused ultrasound to the defined tumor region.

Lesion targeting and selection of anatomically favorable lesions are critical.

Figure 2 includes an image-based guide for lesions that are typically favorable (green, Segment 1, 2, 4a, 6), those which are possibly favorable with advanced targeting experience (e.g., trans-costal approach, Seg 3, 4B, 5) and those which are less likely to be favorable with current ultrasound-based techniques (red, Seg 7, 8, some 4A).

3.3. Post-Treatment Follow Up

Patients undergoing histotripsy are typically discharged on the same day as the procedure, reflecting the minimally invasive nature and low complication risk of the treatment. A structured follow-up schedule is implemented to closely monitor recovery, assess treatment efficacy, and guide further clinical decisions.

If direct treatment is applied to major vascular structures, patients are initiated on therapeutic anticoagulation, usually with direct oral anticoagulation (DOACs) for two weeks from treatment. This is done due to growing evidence of transient thrombosis after such treatments.

3.3.1. Postoperative Day (POD) 1

Patients return for outpatient imaging and laboratory testing on POD1. A tri-phasic CT scan of the liver is performed to evaluate the immediate effects of histotripsy, including tumor disruption and any potential complications such as thrombosis, ascites etc. Recently presented international work does demonstrate that such complications are very rare, but due to the novel nature of the procedure, extra caution is currently being taken. Bloodwork includes standard postoperative labs, such as a CBC and CMP and serum CEA levels to assess overall health and detect any abnormalities.

3.3.2. POD 14

A virtual follow-up appointment was scheduled to review the results of initial testing and assess the patient’s recovery. Providers discuss any symptoms, address patient concerns, and evaluate the progress of healing remotely, minimizing the need for unnecessary in-person visits. These visits are now considered optional as our experience has grown and are conducted at patient and physician preference based on individual case characteristics.

3.3.3. POD 30

Patients return for an in-person evaluation to ensure complete recovery and assess the longer-term effects of the procedure. Before this visit, patients undergo a comprehensive workup, including a tri-phasic CT scan of the liver to measure changes in tumor size and morphology, CBC, CMP and CEA levels, ctDNA testing to evaluate tumor burden and detect potential residual disease. These results are reviewed with the surgeon, allowing for tailored recommendations on ongoing care.

3.3.4. POD 90

Patients undergo a repeat evaluation with the same tests including imaging and bloodwork. The results are discussed during the patient visit. The 90-day visit is also unique in that the potential for re-treatment is considered at this time.

3.4. Management of Concomitant Therapies

To date, there are no documented interactions between histotripsy performed using the HistoSonics Edison® System and concomitant pharmacologic treatments for CRLM. This unique non-invasive technology, which relies on acoustic cavitation rather than thermal, ionizing, or chemical mechanisms, operates independently of the metabolic or pharmacodynamic pathways that might be influenced by systemic therapies such as chemotherapy or targeted agents. The absence of interaction concerns allows histotripsy to complement ongoing systemic therapies. This synergistic approach can maximize therapeutic efficacy, particularly in patients with advanced or multifocal disease, without compromising treatment continuity. Thus, in short, we continue all scheduled systemic medications throughout the peri-procedural period, including chemo/immunotherapy and, importantly, all anticoagulation. We note that anticoagulation is continued including the morning of surgery without interruption. We have not seen a bleeding event to date.

Patients undergoing histotripsy are ensured access to the full spectrum of supportive care to address procedural needs, manage potential side effects, and maintain overall well-being during treatment.

4. Discussion and Ethical Considerations

This is the first description of an institutional approach to a radically novel technology recently FDA-cleared for treatment of liver tumors. In our recent analysis, 18 hospitals had treated patients with this technology and another >50 hospitals are awaiting technology. This makes the adoption of clinical protocols of both immediate programmatic relevance. Such standardization will also aide research and further scientific advancement by allowing cross-institutional comparison.

The use of histotripsy presents some challenges due to limited clinical evidence currently available. As a new technology, its use requires a careful balance between exploring its full potential and maintaining rigorous standards for patient safety and ethical care. The use of histotripsy is justified with FDA-clearance for liver tumors, but its application requires more thoughtful consideration since its indication is backed up with very little evidence and is not clearly defined. When considering histotripsy, it is crucial to compare it to alternative interventions that have a stronger foundation of clinical data. The effectiveness, safety profiles, and long-term outcomes of established locoregional therapies, including thermal ablation, chemoembolization, and surgical resection, are well-supported by extensive clinical evidence and documented research.[

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33] While these methods are effective, they can be invasive, have higher complication rates and have limitations in certain patient populations. On the other hand, histotripsy provides a targeted, non-invasive method with promising initial outcomes, including minimal complications and short recovery periods. Clinicians must, however, balance the potential advantages of histotripsy against the unpredictability that comes with a novel treatment method. The justification for histotripsy lies in its potential to address unmet needs in current treatment options, such as patients who are not surgical candidates or who seek less invasive treatment options may benefit from histotripsy. While histotripsy has admittedly less data than other interventions, there are many populations where it seems to have immediate clinical advantages, and improved safety profile, such that its’ use immediate use might benefit patients in the immediate setting.

A fundamental component of ethical medical practice is the "do no harm" principle. When compared to invasive procedures like thermal ablation or surgical resection, histotripsy has shown an exceptional safety profile with noticeably lower rates of complications. Its ethical use is supported by its low risk profile, especially for patients who might not be able to tolerate conventional treatment methods because of comorbidities or advanced disease. Histotripsy is also used in a palliative setting with the aim of inducing off-target immunologic tumor damage but more data supporting optimal patient selection and application will be necessary Nevertheless, since it is shown to be safe and easy on the patient without interruption of systemic therapies throughout treatment, we are applying histotripsy with relatively little restriction until we get more supporting data. It is imperative that the patient is fully aware about limitations of histotripsy and that data regarding oncological outcome is very limited before making a decision.

A case report from our group recently described a patient that underwent liver transplantation following histotripsy in our clinic, and it documents the groundbreaking use of histotripsy as a bridging therapy prior to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), marking a significant step in advancing treatment modalities[

34]. The findings provide post-trial evidence of a complete pathological response, demonstrated by total necrosis of the treated lesion observed in the explanted liver. Despite histotripsy’s non-invasive nature and the lack of histological data from previous treatments, liver transplantation offered a unique opportunity to confirm the therapy’s effect. This allows potential de-coupling of oncologic urgency of transplant versus management of liver disease. Despite the increasing availability of grafts with machine perfusion, transplant oncology continues to represent a major disease burden, and studies have already shown how other LRT’s can impact post-transplant outcomes[

35,

36,

37,

38].

These human results align with preclinical studies by Worlikar et al., which showed complete tumor regression using histotripsy in animal models[

17]. The study’s outcomes are particularly promising, showing complete tumor necrosis at the cellular level. This finding raises the possibility of histotripsy serving as a curative treatment, as suggested by preclinical evidence. However, in the described case, cirrhosis due to metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) necessitated liver transplantation. Without the presence of cirrhosis, histotripsy might have provided a standalone curative solution. For this patient, conventional bridging therapies were not feasible due to hepatic-pulmonary arterial shunting. Histotripsy became the selected treatment, highlighting its potential to address gaps in current therapeutic options. The success of histotripsy in this case underscores its potential as a valuable addition to HCC treatment strategies, particularly as a non-invasive alternative to more risky and invasive bridging methods.

5. Conclusions

CRLM present significant challenges in cancer treatment, with limited options for patients deemed ineligible for surgical resection. Histotripsy is emerging as an innovative and non-invasive approach with the potential to address these gaps, offering precise tumor destruction with minimal damage to surrounding tissue. Herein, we describe our institutional approach to histotripsy before, during and after the procedure in an attempt to inform this growing practice. While more research is needed to confirm long-term benefits, histotripsy provides a promising alternative for managing CRLM and advancing liver cancer care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.H.D.K., F.A. and J.K.; M.U.; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.W.; writing—review and editing, C.H.D.K.; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as this is a review article.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Arain, M.A.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Garrido-Laguna, I.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Rectal Cancer, Version 6.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2020, 18, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Nordlinger, B.; Adam, R.; Köhne, C.H.; Pozzo, C.; Poston, G.; Ychou, M.; Rougier, P. Towards a pan-European consensus on the treatment of patients with colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Cancer 2006, 42, 2212–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordlinger, B.; Van Cutsem, E.; Rougier, P.; Köhne, C.H.; Ychou, M.; Sobrero, A.; Adam, R.; Arvidsson, D.; Carrato, A.; Georgoulias, V.; et al. Does chemotherapy prior to liver resection increase the potential for cure in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer? A report from the European Colorectal Metastases Treatment Group. Eur J Cancer 2007, 43, 2037–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Eynde, M.; Hendlisz, A. Treatment of colorectal liver metastases: a review. Rev Recent Clin Trials 2009, 4, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poston, G.J.; Figueras, J.; Giuliante, F.; Nuzzo, G.; Sobrero, A.F.; Gigot, J.F.; Nordlinger, B.; Adam, R.; Gruenberger, T.; Choti, M.A.; et al. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26, 4828–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solheim, J.M.; Dueland, S.; Line, P.D.; Hagness, M. Transplantation for Nonresectable Colorectal Liver Metastases: Long-Term Follow-Up of the First Prospective Pilot Study. Ann Surg 2023, 278, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.B.; D'Angelica, M.I.; Abbott, D.E.; Abrams, T.A.; Alberts, S.R.; Anaya, D.A.; Anders, R.; Are, C.; Brown, D.; Chang, D.T.; et al. Guidelines Insights: Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 2.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019, 17, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.B.; Venook, A.P.; Al-Hawary, M.M.; Cederquist, L.; Chen, Y.J.; Ciombor, K.K.; Cohen, S.; Cooper, H.S.; Deming, D.; Engstrom, P.F.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colon Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018, 16, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livraghi, T.; Meloni, F.; Solbiati, L.; Zanus, G. Complications of microwave ablation for liver tumors: results of a multicenter study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012, 35, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livraghi, T.; Solbiati, L.; Meloni, M.F.; Gazelle, G.S.; Halpern, E.F.; Goldberg, S.N. Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology 2003, 226, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Wang, Y.; Yu, X.; Dong, B. Malignant liver tumors: treatment with percutaneous microwave ablation--complications among cohort of 1136 patients. Radiology 2009, 251, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shady, W.; Petre, E.N.; Gonen, M.; Erinjeri, J.P.; Brown, K.T.; Covey, A.M.; Alago, W.; Durack, J.C.; Maybody, M.; Brody, L.A.; et al. Percutaneous Radiofrequency Ablation of Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases: Factors Affecting Outcomes--A 10-year Experience at a Single Center. Radiology 2016, 278, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapisochin, G.; Barry, A.; Doherty, M.; Fischer, S.; Goldaracena, N.; Rosales, R.; Russo, M.; Beecroft, R.; Ghanekar, A.; Bhat, M.; et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy vs. TACE or RFA as a bridge to transplant in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. An intention-to-treat analysis. J Hepatol 2017, 67, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livraghi, T.; Meloni, F.; Di Stasi, M.; Rolle, E.; Solbiati, L.; Tinelli, C.; Rossi, S. Sustained complete response and complications rates after radiofrequency ablation of very early hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: Is resection still the treatment of choice? Hepatology 2008, 47, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.; Yu, J.; Yu, X.L.; Wang, X.H.; Wei, Q.; Yu, S.Y.; Li, H.X.; Sun, H.T.; Zhang, Z.X.; Liu, H.C.; et al. Percutaneous cooled-tip microwave ablation under ultrasound guidance for primary liver cancer: a multicentre analysis of 1363 treatment-naive lesions in 1007 patients in China. Gut 2012, 61, 1100–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worlikar, T.; Zhang, M.; Ganguly, A.; Hall, T.L.; Shi, J.; Zhao, L.; Lee, F.T.; Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Cho, C.S.; Xu, Z. Impact of Histotripsy on Development of Intrahepatic Metastases in a Rodent Liver Tumor Model. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worlikar, T.; Hall, T.; Zhang, M.; Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Green, M.; Cho, C.S.; Xu, Z. Insights from in vivo preclinical cancer studies with histotripsy. Int J Hyperthermia 2024, 41, 2297650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Jove, J.; Serres, X.; Vlaisavljevich, E.; Cannata, J.; Duryea, A.; Miller, R.; Merino, X.; Velat, M.; Kam, Y.; Bolduan, R.; et al. First-in-man histotripsy of hepatic tumors: the THERESA trial, a feasibility study. Int J Hyperthermia 2022, 39, 1115–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendiratta-Lala, M.; Wiggermann, P.; Pech, M.; Serres-Créixams, X.; White, S.B.; Davis, C.; Ahmed, O.; Parikh, N.D.; Planert, M.; Thormann, M.; et al. The #HOPE4LIVER Single-Arm Pivotal Trial for Histotripsy of Primary and Metastatic Liver Tumors. Radiology 2024, 312, e233051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlaisavljevich, E.; Kim, Y.; Owens, G.; Roberts, W.; Cain, C.; Xu, Z. Effects of tissue mechanical properties on susceptibility to histotripsy-induced tissue damage. Phys Med Biol 2014, 59, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepple, A.L.; Guy, J.L.; McGinnis, R.; Felsted, A.E.; Song, B.; Hubbard, R.; Worlikar, T.; Garavaglia, H.; Dib, J.; Chao, H.; et al. Spatiotemporal local and abscopal cell death and immune responses to histotripsy focused ultrasound tumor ablation. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1012799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Wehrle, C.J.; Zhang, M.; Fares, S.; Stitzel, H.; Garib, D.; Estfan, B.; Kamath, S.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Ma, W.W.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Profiling in Liver Transplant for Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Cholangiocarcinoma, and Colorectal Liver Metastases: A Programmatic Proof of Concept. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, R.; Wehrle, C.J.; Aykun, N.; Stitzel, H.; Ma, W.W.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Estfan, B.; Kamath, S.; Kwon, D.C.H.; Aucejo, F. Immunotherapy Plus Locoregional Therapy Leading to Curative-Intent Hepatectomy in HCC: Proof of Concept Producing Durable Survival Benefits Detectable with Liquid Biopsy. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Hong, H.; Kamath, S.; Schlegel, A.; Fujiki, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Kwon, D.C.H.; Miller, C.; Walsh, R.M.; Aucejo, F. Tumor Mutational Burden From Circulating Tumor DNA Predicts Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Resection: An Emerging Biomarker for Surveillance. Ann Surg 2024, 280, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Raj, R.; Aykun, N.; Orabi, D.; Estfan, B.; Kamath, S.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Fujiki, M.; Hashimoto, K.; Quintini, C.; et al. Liquid Biopsy by ctDNA in Liver Transplantation for Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis. J Gastrointest Surg 2023, 27, 1498–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Raj, R.; Aykun, N.; Orabi, D.; Stackhouse, K.; Chang, J.; Estfan, B.; Kamath, S.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Walsh, R.M.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis: Analysis of Patients Receiving Liver Resection and Transplant. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 2023, 7, e2300111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogl, T.J.; Freichel, J.; Gruber-Rouh, T.; Nour-Eldin, N.A.; Bechstein, W.O.; Zeuzem, S.; Naguib, N.N.N.; Stefenelli, U.; Adwan, H. Interventional Treatments of Colorectal Liver Metastases Using Thermal Ablation and Transarterial Chemoembolization: A Single-Center Experience over 26 Years. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puls, R.; Langner, S.; Rosenberg, C.; Hegenscheid, K.; Kuehn, J.P.; Noeckler, K.; Hosten, N. Laser ablation of liver metastases from colorectal cancer with MR thermometry: 5-year survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009, 20, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Heo, J.S.; Cho, Y.B.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.C.; Lee, W.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Choi, D.W. Hepatectomy vs radiofrequency ablation for colorectal liver metastasis: a propensity score analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 3300–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, K.; McBride, J.D.; Georgiades, C.S.; Reyes, D.K.; Herman, J.M.; Kamel, I.R.; Geschwind, J.F. Salvage therapy for liver-dominant colorectal metastatic adenocarcinoma: comparison between transcatheter arterial chemoembolization versus yttrium-90 radioembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009, 20, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groeschl, R.T.; Pilgrim, C.H.; Hanna, E.M.; Simo, K.A.; Swan, R.Z.; Sindram, D.; Martinie, J.B.; Iannitti, D.A.; Bloomston, M.; Schmidt, C.; et al. Microwave ablation for hepatic malignancies: a multiinstitutional analysis. Ann Surg 2014, 259, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, M.; Kiefer, M.V.; Sun, W.; Haller, D.; Fraker, D.L.; Tuite, C.M.; Stavropoulos, S.W.; Mondschein, J.I.; Soulen, M.C. Chemoembolization of colorectal liver metastases with cisplatin, doxorubicin, mitomycin C, ethiodol, and polyvinyl alcohol. Cancer 2011, 117, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal, M.W., C. J.; Coppa, C.; Kamath, S.; Krishnamurthi, S.; Martin, C.; El Hag, M.; Khalil, M.; Fujiki, M.; Schlegel, A.; Miller, C.; Hashimoto, K.; Aucejo, F.; Kwon, D. C. H.; Kim, J. Bridging Therapy with Histotripsy prior to Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A First Case Report. Experimental Hematology & Oncology 2024.

- Wehrle, C.J.; Hong, H.; Gross, A.; Liu, Q.; Ali, K.; Cazzaniga, B.; Miyazaki, Y.; Tuul, M.; Modaresi Esfeh, J.; Khalil, M.; et al. The impact of normothermic machine perfusion and acuity circles on waitlist time, mortality, and cost in liver transplantation: A multicenter experience. Liver Transpl 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Zhang, M.; Khalil, M.; Pita, A.; Modaresi Esfeh, J.; Diago-Uso, T.; Kim, J.; Aucejo, F.; Kwon, D.C.H.; Ali, K.; et al. Impact of Back-to-Base Normothermic Machine Perfusion on Complications and Costs: A Multicenter, Real-World Risk-Matched Analysis. Ann Surg 2024, 280, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Kusakabe, J.; Akabane, M.; Maspero, M.; Zervos, B.; Modaresi Esfeh, J.; Whitsett Linganna, M.; Imaoka, Y.; Khalil, M.; Pita, A.; et al. Expanding Selection Criteria in Deceased Donor Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Long-term Follow-up of a National Registry and 2 Transplant Centers. Transplantation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, C.J.; Raj, R.; Maspero, M.; Satish, S.; Eghtesad, B.; Pita, A.; Kim, J.; Khalil, M.; Calderon, E.; Orabi, D.; et al. Risk assessment in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term follow-up of a two-centre experience. Int J Surg 2024, 110, 2818–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).