1. Introduction

During 2023 in Italy, 91.6 % of young people in the 15-17 age group used the Internet every day (1) and smartphones were in the first position among the devices with the widest rate of diffusion. Within the 11-13 age group, 78.3% of Italian children used the Internet every day, mainly through smartphones. The age at which young people begin to own or to use a smartphone also decreased and, after the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in children aged 6-10 years who use mobile phones every day, from 18.4% (2018-19) to 30.2% (2021-22) (2). This same phenomenon has been observed worldwide, with a general lowering of the age of first contact with mobile devices (3,4). The use of smartphones has radically changed people's daily habits, facilitating communication and access to information without constraints of time and place; on the other side, evidences show an increasing number of individuals who is suffering of problematic phone usage (5-7). A great number of studies has underlined the association between the use of smartphones, internet addiction, and psychiatric disorders, mostly in the area of mood and anxiety (8-11).

Specifically, in school-age children, Smartphone Addiction (SA) involves negative consequences in daily mental, psychological, physical and social functioning (12,13) and, like all addiction disorders, it’s a complex and multifaceted condition (14-16). SA has been described as the effect of unrestrained smartphone use on daily routine (17), and it comprises symptoms concerning the availability of the device, craving for its access and scarce outcomes in interpersonal relationships (18). The concept of addiction has been associated with technology early in the years of internet spreading (19), and a recent systematic review provided consistent evidence of neuroanatomical abnormalities in individuals with SA in the gratification circuit and in areas involved in executive functions (20). In this light, it has been proposed that SA may be supported by typical personality traits known to be related to addiction and dependency (18).

Personality is a manifold construct which features the dynamic progression of integrative characteristics into what the individual will display in terms of social interactions and behavioral outputs (21). It moves from the early stages of growth, as it is considered evolving from the infantile temperament, and it's therefore explorable during the developmental age (22). Personality dimensions have been extensively analyzed in adolescents and young adults, highlighting traits that may play a protective role or act as risk factors, and also their evolution related to a particular kind of Internet use. In particular, some personality dimensions have been reported to be related to SA, including impulsivity and instant gratification addiction (23, 24); low self-control (25); low self-esteem; and low Openness (26). A study focusing on young adults from different countries (27) found that SA is strongly associated with low Conscientiousness and high Neuroticism, and correlates positively with Social Anxiety and Impulsivity. Considering studies that have referenced the Person component of the I-PACE model (14), a recent meta-analysis (28) covering samples of adults and young adults found that Conscientiousness and Neuroticism, respectively, correlate negatively and positively with Smartphone Use Disorder (SUD), highlighting them as risk factors.

The role of personality dimensions regarding SA in children has been less investigated and comprehensive reviews are still scarce (25).

Basino on letterature’s analysis, the purpose of this study is to verify the level of SA and the relationship between SA and personality dimensions in children attending primary schools. To investigate personality dimensions, we decided to use the Big Five Children (BFC) (29). Marengo et al. provided empirical evidence that the Big Five personality model is useful to understand individual differences in smartphone use disorder and suggests using it in the assessment stages (28). To investigate SA, we used the Smartphone Addiction Risk Children Questionnaire (SARCQ), a test recently validated in Italy (30) which, unlike other similar questionnaires, allows to assess the ability to handle negative emotions and loneliness, and to test whether the smartphone is used as a transitional object, as this has been described by Winnicott (31).

2. Materials and Methods

Two self-assessment questionnaires, the Smartphone Addiction Risk Children Questionnaire (SARCQ) (30) and the Big Five Children (BFC) (29), were administered respectively to verify A) the presence of SA and its severity and B) to assess the interplay between personality dimensions and SA.

The SARCQ test (30) evaluates the risk of SA in children. The SARCQ is composed of 11 items, associated with two specific dimensions (the last 5 items are distractors).

The first dimension named “I’m not afraid with you” (INAWY) is related to handling negative emotions and loneliness. This dimension correlates with the use of smartphones to avoid negative emotions and its use as a relief. It implies escape from reality, stress and unhappiness (32). Moreover, it is also related to the use of smartphones instead of dealing with negative emotions such as fear, sadness and anger. Boys and girls increase their smartphone use to compensate for the negative feeling due to negative emotions: “I don’t feel them, so they aren’t there!“. This dimension is also related to the “addiction”: boys and girls feel bad if they cannot have their smartphone with them. The items correlated to INAWY are: “I feel alone if I can’t use my smartphone”, “I get angry if I can’t use my smartphone”, “I use my smartphone instead of doing something else (for example: play, draw, stay with friends)”, “I use my smartphone to get better when I’m sad”, “I feel sad if something bad is happening and I cannot use my smartphone” and “I go to sleep late because I use my smartphone”.

The second factor “Linus’ blanket” (LB) is inspired by the well-known cartoon’s character who held a protective blanket. This dimension is related to the use of smartphones in relationship with parents and friends and not to miss them. Thus, the smartphone becomes a transitional object for boys and girls. This dimension is related to socialization difficulties and avoiding any direct contact with the others or to sublimate their absence. LB is correlated with the items: “I check my smartphone to see if anyone has called or sent me a message”, “I need to keep my smartphone with me to feel more confident”, “When I take my smartphone with me I feel closer to mom and dad”, “When I take my smartphone with me, I feel safer” and “Mom and dad are calmer when I take my smartphone with me”.

The BFC (29) measures personality with five major dimensions.

Energy/Extraversion (E): refers to how much the child is cheerful, lively and how much he enjoys connecting with other people and getting involved in games. Friendliness (F): refers to how much the child is sociable, affectionate, empathetic and able to establish bonds of friendship. Conscientiousness (C): refers to how much the child is able to concentrate, to make a commitment in a precise and scrupulous way and how much he feels able to carry out the tasks. Emotional Stability (S): refers to how much the child can manage his emotions and respond to negative situations without getting discouraged or angry (in the Italian version this factor is a reverse factor, called “Emotion Instability”). Openness (O): refers to how the child is imaginative, creative, curious and is able to find solutions to problems in school or life.

The answers were at 3-point Likert scale: 1. Never; 2. Sometimes; 3. Always.

A sample (N = 94) of children (age: mean=9 years, SD=± 9.8 months). All participants were Caucasian. Recruited participants were all students of four primary schools pertaining to the Cagliari metropolitan area, south Sardinia, Italy, from March 2022 to June 2022. These schools accepted to take part in this research after a general request addressed to all the schools belonging to this district.

All the parents of participants signed the informed consent. SARCQ and BFC questionnaires were completed by participants in classrooms with four researchers supervising. Both children and their parents were informed that data collection and questionnaires’ answers would have been anonymized. Being all the participants underaged, their parents were submitted and asked to sign an informative sheet describing the aim of the research, data processing, informed consents, and the use of the data for research purposes. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethic Committee of the Department of Education, Psychology and Philosophy of University of Cagliari. The research was approved by the Ethic Board of the University of Cagliari (n. 26/17, on 06/27/2017).

Smartphone Addiction Risk Children Questionnaire (SARCQ)

SACRQ is 13-ítems questionnaire. The items measuring smartphone addition are 11:

item 1: “I check my smartphone to see if any-one has called or sent me a message“;

item 2: “I need to keep my smartphone with me to feel more confident”;

item 3: “I feel alone if I can’t use my smartphone”;

item 4: “When take my smartphone with me I feel closer to mom and dad”;

item 5: “I get angry if I cannot use my smartphone”;

item 6: “I use my smartphone instead of doing something else (for example: play, draw, stay with friends)”;

item 7: “When I take my smartphone with me, I feel safer”;

item 8: “I use my smartphone to get better when I’m sad”;

item 9: “Mom and dad are calmer when I take my smartphone with me”;

item 10: “I feel sad if something of bad is happening and I cannot use my smartphone”;

item 11: “, and “I go to sleep late because I use my smartphone”.

The answers were a three-points likert scale: 1-never; 2-sometimes, 3-always.

3. Results

3.1. The SARCQ Questionnaire

Frequencies mean and standard deviation (SD), skewness and kurtosis were performed for individual items. Skewness and Kurtosis were used to evaluate the relevance of the expected normal asymmetry of SARCQs items in the direction of little or moderate children’s problems. Specifically, skewness ranged from -.067 To 1.224 and Kurtosis ranged from -1.521 to 2.093.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the SARCQ questionary.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for the SARCQ questionary.

| Descriptive Statistics |

|---|

| |

Mean |

S. E. of the mean |

Median |

Std. Deviation |

Skewness |

S. E. of Skewness |

Kurtosis |

S. E. of Kurtosis |

| Item 1 |

2.04 |

.038 |

2 |

.823 |

-.067 |

.113 |

-1.521 |

.225 |

| Item 2 |

1.62 |

.035 |

1 |

.762 |

.769 |

.113 |

-.874 |

.225 |

| Item 3 |

1.3 |

.027 |

1 |

.594 |

1.809 |

.113 |

2.093 |

.225 |

| Item 4 |

1.65 |

.034 |

1 |

.742 |

.654 |

.113 |

-.916 |

.225 |

| Item 5 |

1.6 |

.033 |

1 |

.722 |

.768 |

.113 |

-.720 |

.225 |

| Item 6 |

1.53 |

.029 |

1 |

.638 |

.805 |

.113 |

-.39 |

.225 |

| Item 7 |

1.77 |

.037 |

2 |

0,807 |

.444 |

.113 |

-1.327 |

.225 |

| Item 8 |

1.59 |

.033 |

1 |

.721 |

.809 |

.113 |

-.667 |

.225 |

| Item 9 |

1.78 |

.038 |

2 |

.821 |

.428 |

.113 |

-1.389 |

.225 |

| Item 10 |

1.44 |

.031 |

1 |

0,665 |

1.224 |

.113 |

.234 |

.225 |

| Item 11 |

1.44 |

.030 |

1 |

.655 |

1.212 |

.113 |

.247 |

.225 |

Table 2.

Correlation matrix between SARCQs items.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix between SARCQs items.

| |

item3 |

item5 |

item23 |

item25 |

item34 |

item42 |

item45 |

item49 |

item51 |

item53 |

item56 |

| item3 |

1,000 |

,477 |

,328 |

,523 |

,523 |

,429 |

,299 |

,355 |

,229 |

,338 |

,207 |

| item5 |

,477 |

1,000 |

,481 |

,572 |

,640 |

,473 |

,360 |

,293 |

,217 |

,384 |

,216 |

| item23 |

,328 |

,481 |

1,000 |

,453 |

,428 |

,397 |

,331 |

,262 |

,121 |

,316 |

,193 |

| item25 |

,523 |

,572 |

,453 |

1,000 |

,637 |

,428 |

,361 |

,357 |

,291 |

,489 |

,268 |

| item34 |

,523 |

,640 |

,428 |

,637 |

1,000 |

,431 |

,246 |

,302 |

,217 |

,379 |

,189 |

| item42 |

,429 |

,473 |

,397 |

,428 |

,431 |

1,000 |

,388 |

,415 |

,259 |

,352 |

,290 |

| item45 |

,299 |

,360 |

,331 |

,361 |

,246 |

,388 |

1,000 |

,462 |

,375 |

,505 |

,423 |

| item49 |

,355 |

,293 |

,262 |

,357 |

,302 |

,415 |

,462 |

1,000 |

,412 |

,495 |

,370 |

| item51 |

,229 |

,217 |

,121 |

,291 |

,217 |

,259 |

,375 |

,412 |

1,000 |

,566 |

,502 |

| item53 |

,338 |

,384 |

,316 |

,489 |

,379 |

,352 |

,505 |

,495 |

,566 |

1,000 |

,555 |

| item56 |

,207 |

,216 |

,193 |

,268 |

,189 |

,290 |

,423 |

,370 |

,502 |

,555 |

1,000 |

Table 3 and

Table 4 show value of reliability of each item for INAWI and for LB.

Cronbach’s α for SARCQ and both INAWAY and LB sub-scales has been reported in

Table 5.

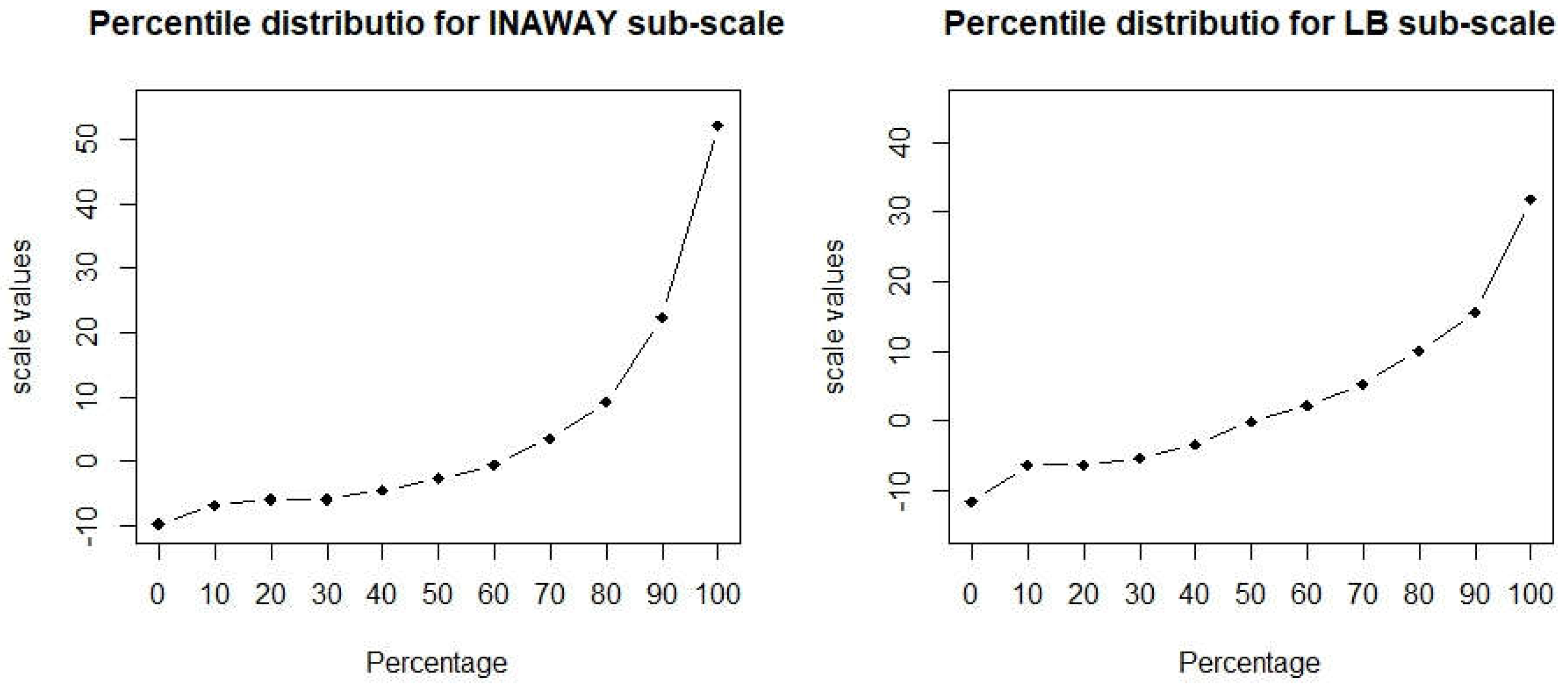

Table 3 shows percentage distribution of weighted scale values for the two factorial dimensions.

Table 6.

Scale scores.

| |

Min |

10% |

20% |

30% |

40% |

50% |

60% |

70% |

80% |

90% |

Max |

| INAWY |

-9.69 |

-6.75 |

-5.87 |

-5.87 |

-4.46 |

-2.62 |

-0.55 |

3.57 |

9.16 |

22.34 |

52.13 |

| LB |

-11.57 |

-6.26 |

-6.26 |

-5.33 |

-3.32 |

-0.049 |

2.16 |

5.37 |

10.07 |

15.55 |

31.73 |

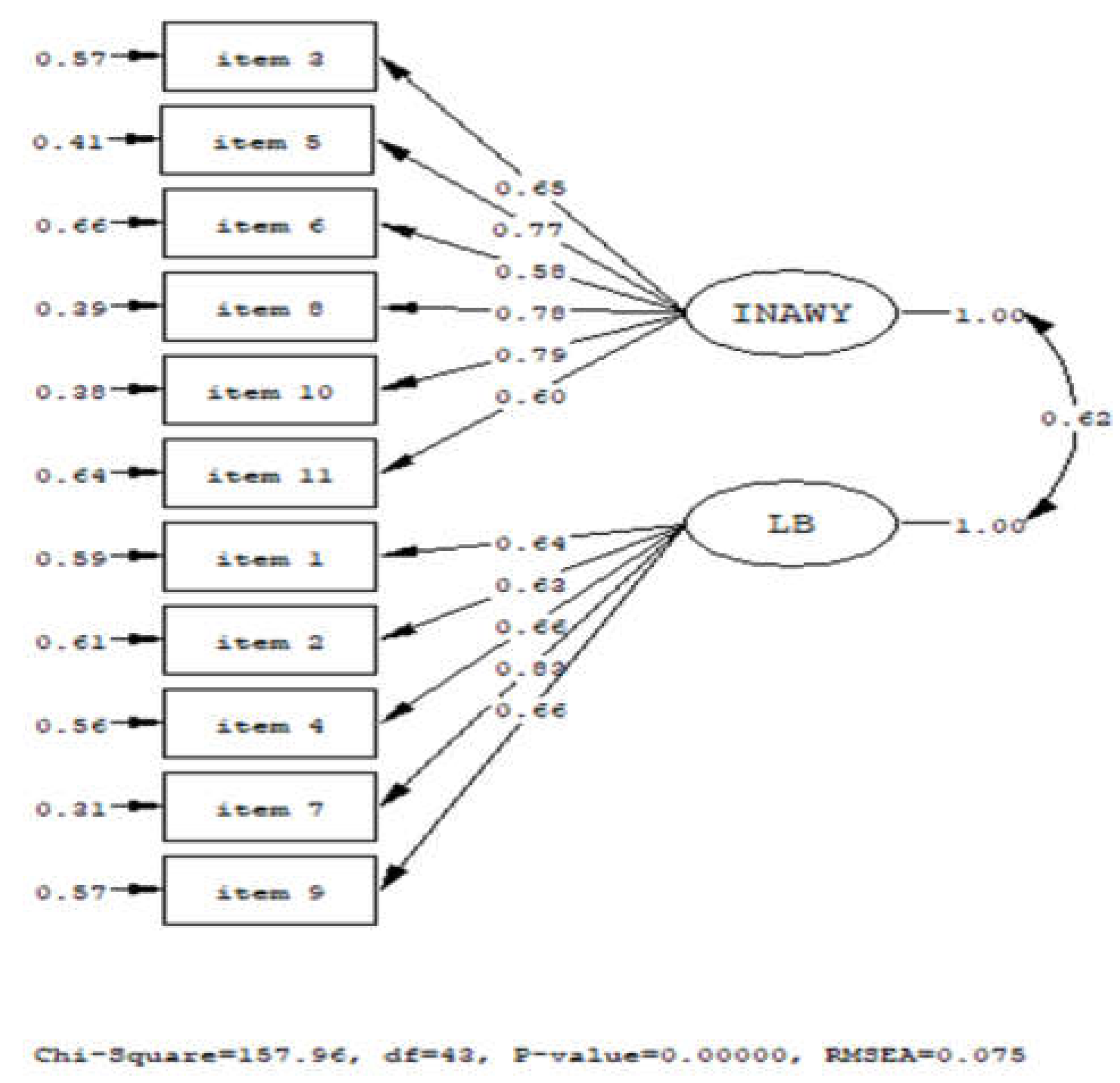

3.2. The Structural Confirmatory Factorial Model for SARCQ Questionnaire

In order to verify factor’s structure of exploratory factor analysis a confirmatory factor analysis was performed using statistical program LisRel 8.8 (Joreskög, K.G. (1969, 1970, 1973, 1979),).

Table 7 shows the values of estimated structural parameters Lambda-X completely randomized. The solution offered by confirmatory factor analysis endorsed the two-dimensional structure.

Table 7.

Confirmatory factor solution (Lambda-X).

Table 7.

Confirmatory factor solution (Lambda-X).

| LAMBDA-X |

| Items |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

| INAWY |

|

|

0.65* |

|

0.77* |

0.58* |

|

0.78* |

|

0.79* |

0.60* |

| LB |

0.64* |

0.63* |

|

0.66* |

|

|

0.83* |

|

0.66* |

|

|

Figure 2 shows graphic solution of confirmatory factor model with structural standardized parametric values.

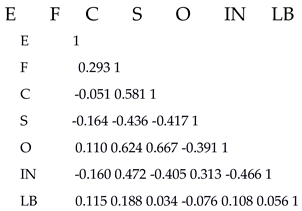

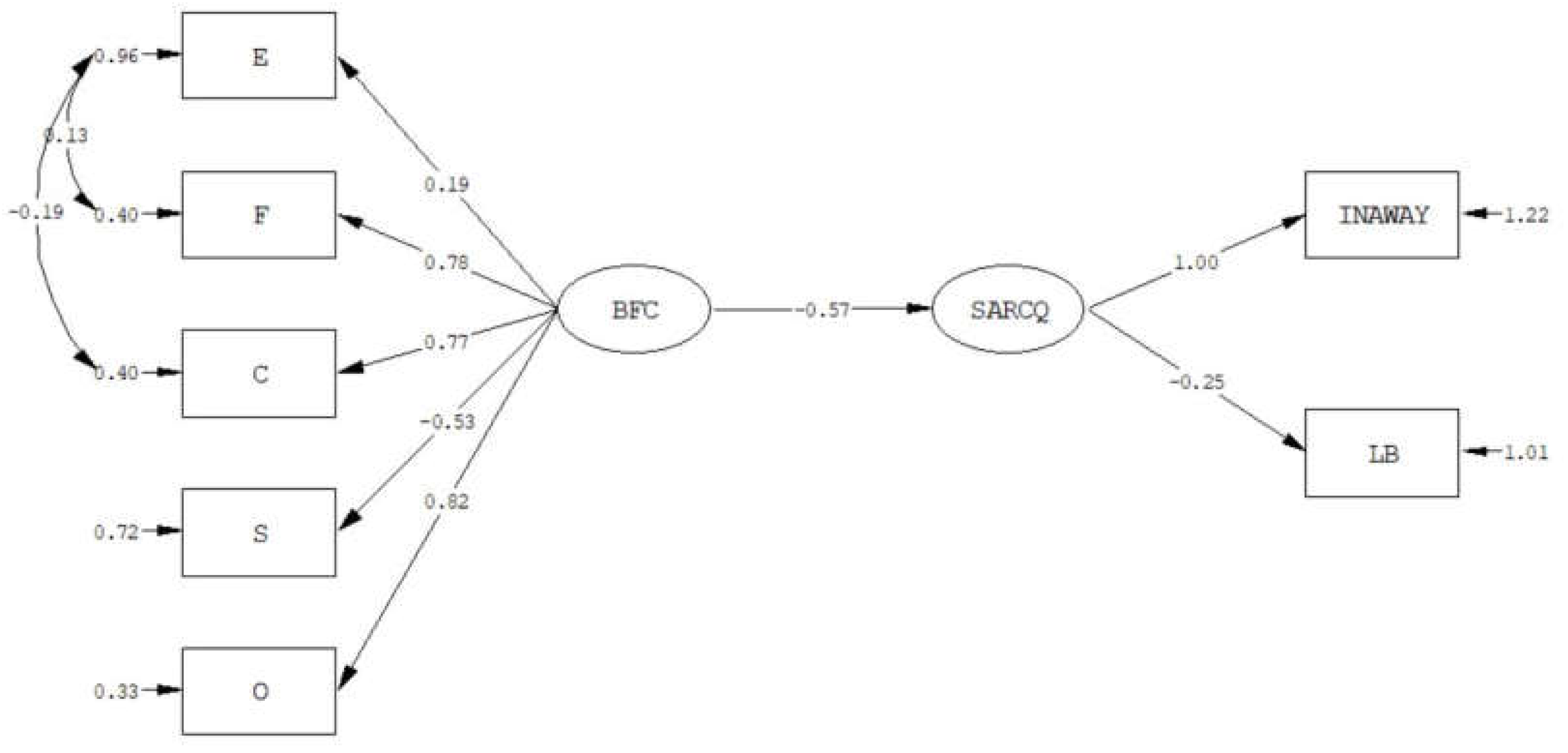

3.3. The Structural Equation Model Between BFC and SARCQ

First of all, Pearson’s correlation matrix has been performed between INAWY and LB dimensions of the SARCQ and the five factors of BFC. R Version 4.3.2 was used to process the dataset. The correlation structure was then employed and submitted to a Structural Equation Model (SEM), in order to discover the strength of relations existing between BFC representing the exogeneous dimensions of the model and the SARCQs dimensions as endogenous variables. The parametric solution of the tested model has been generated by the use of LisRel 8.8 (see Joreskög, K.G., Sörbom, D. (1988) for details). The implemented model is shown in

Figure 2, whereas the estimated parameters and fit indices will be shown, respectively, in

Table 1 and

Table 2 below. The different typology of structural parameters was displayed by columns; in contrast rows involve the profile concerning each single indicator inside the whole model tested. The analyzed triangular Pearsons’ correlation matrix between BFC and SARCQ has been reported in

Table 7:

Table 7.

Correlation matrix between BFC and SARCQ.

Table 7.

Correlation matrix between BFC and SARCQ.

Figure 3 shows the structural equation model solution obtained using the BFC as exogenous latent tract and SARCQ as endogenous latent tract.

Table 8.

Structural parameters and error variances for each indicator.

Table 8.

Structural parameters and error variances for each indicator.

| |

BFC |

SARCQ |

| |

λx |

θδ

|

λy |

θε

|

| E |

0.19 |

0.96 |

- |

- |

| F |

0.78 |

0.40 |

- |

- |

| C |

0.77 |

0.40 |

- |

- |

| S |

-0.53 |

0.72 |

- |

- |

| O |

0.82 |

0.33 |

- |

- |

| INAWAY |

- |

- |

1.00 |

1.22 |

| LB |

- |

- |

-0.25 |

1.01 |

Results of the analyses show that the model may not be rejected, at the light of the observed values of several Goodness of Fit Statistics, as reported in

Table 9.

Moreover, the theta-delta covariance matrix of errors for the five dimensions of BFC was found to be not diagonal indicating that some measurement error may covariate with some other. In this case, we found the error associated with Energy/Extraversion (E) covariate reliably both with Friendliness (F) and Conscientiousness (C) (see

Figure 3 for parametric details).

Table 10 show that the BFCs exogenous indicators may be indirectly associated with the endogenous indicators INAWAY and LB of SARCQ: with respect to the indirect effect components.

4. Discussion

In recent years, smartphones have had a great increase in their use being a user-friendly tool with fast access to digital information. They facilitate communication, working and relationships, but smartphone overuse causes problematic effects in both psychological and physical aspects (33-36). The main result of this study is that 1.6 participants out of 10 show signs of SA, in line with a recent nationwide study conducted in South Korea (3). Moreover, it emerged that the use of smartphones as ”emotion-handling tool” or as a "transitional object" concerns in particular children which exhibit low Friendliness, low Conscientiousness and with socialization issues (23, 37), so that these children may favor indirect relationships, lived through the smartphone, to directly accessed ones in presence. It has been proposed that smartphones may be used by individuals with an insecure attachment style (38), so that the anxiety that rises within the interpersonal relationship may be held back by the involvement in virtual engagement. Studies on adult subjects have underlined how this pattern of relationship has to be challenged, helping patients in developing solid connections in real life rather than the internet, in which the relief from attachment anxiety is artificial and unstable (23). Moreover, socialization issues are prone to isolate people, hampering the creation of strong relationships. It has been found that also loneliness and poor social skills can drive subjects to increase the time on screen (39), and therefore to focus on immaterial and mediated interactions instead of talking in person to others. Given that the Internet provides bashful subjects with entertainment and various contents, SA creates a comfortable environment in which public constraints and difficult situations are easily avoided. Therefore, individuals who suffer loneliness due to socialization issues would count on smartphones more and more, clearing the way to addiction (37).

This research underlined that negative personality dimensions could represent the background of addiction. Thus, primary prevention is crucial. A large body of evidence corroborates the effectiveness of early psychological intervention in preventing the development of mental health issues and aberrant behaviors, especially pertaining to addiction (40,41). These interventions should be focused on improving personality dimensions such as friendliness, emotional stability, consciousness and openness to experiences (42). Primary prevention is more profitable when implemented during childhood and/or early adolescence rather than during late ages, given the impact of SA and the consequences it may cause (43,44).

The application of the SARCQ test, specifically developed for children and saturating on the two factors “emotion management” and “smartphone use as a transitional object,” is an innovative element. The results it produces can be used as a specific target both in early treatment and prevention strategies. This research is affected by some limitations that may be considered for the design of future studies. Smartphone use in children may reflect attitudes or context pertaining to different cultural backgrounds, in terms of parenting styles (45), social consideration of new technologies (46) and their affordability; therefore it may vary across countries and social classes. Furthermore, it may evolve with aging. As SA may have repercussions in both personal and social contexts (10-11), more detailed observations about problematic smartphone use risk are expected. Considering that social networks in particular have been linked with poor mental outcomes for children in several studies (47), for instance, gathering more details on the specific content (social networks, instant messaging app, streaming platform, search engines) accessed by the participants could be profitable to this research topic in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and R.T.; methodology, C.G.; software, E.F.N.; validation, C.S., R.T. and C.G.; formal analysis, E.F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S., R.T. and C.G.; writing—review and editing, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ISTAT Giovani.stat: dati e indicatori sulla popolazione di 15-34 anni in Italia [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2023 May 22]. Available from: http://dati-giovani.istat.it/.

- De Marchi, V. Tempi digitali - Atlante dell’infanzia (a rischio) 2023. Save the Children Italia, editor. Roma: Save the Children Italia; 2023.

- Park, J.H.; Park, M. Smartphone use patterns and problematic smartphone use among preschool children. PLoS One. 2021, 16, e0244276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domoff, S.E.; Radesky, J.S.; Harrison, K.; Riley, H.; Lumeng, J.C.; Miller, A.L. A naturalistic study of child and family screen media and mobile device use. J Child Fam Stud. 2019, 28, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truzoli, R.; Biscaldi, V.; Valioni, E.; Conte, S.; Rovetta, C.; Casazza, G. Socio-demographic factors and different internet-use patterns have different impacts on internet addiction and entail different risk profiles in males and females. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2024, 66, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wolniewicz, C.A.; Tiamiyu, M.F.; Weeks, J.W.; Elhai, J.D. Problematic smartphone use and relations with negative affect, fear of missing out, and fear of negative and positive evaluation. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 262, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.Y.; Rees, P.; Wildridge, B.; Kalk, N.J.; Carter, B. Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry. 2019, 19, 356. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D.; Levine, J.C.; Hall, B.J. Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord. 2017, 207, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branciforti, S.; Valioni, E.; Biscaldi, V.; Rovetta, C.; Viganò, C.; Truzoli, R. Internet addiction disorder’s screening and its association with socio-demographic and clinical variables in psychiatric outpatients. Act Nerv Super Rediviva. 2023, 65, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, C.H.; Yen, J.Y.; Yen, C.F.; Chen, C.S.; Chen, C.C. The association between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorder: a review of the literature. Eur Psychiatry. 2012, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.; Payne, M.; Rees, P.; Sohn, S.Y.; Brown, J.; Kalk, N.J. A multi-school study in England, to assess problematic smartphone usage and anxiety and depression. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 2240–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapacz, M.; Rockman, G.; Clark, J. Are we addicted to our cell phones? Comput Human Behav. 2016, 57, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Valley, B.; Simecka, B.A. Mental Health Concerns in the Digital Age. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2017, 15, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Young, K.S.; Laier, C.; Wölfling, K.; Potenza, M.N. Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016, 71, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Osso B, Di Bernardo I, Vismara M, Piccoli E, Giorgetti F, Molteni L, et al. Managing Problematic Usage of the Internet and Related Disorders in an Era of Diagnostic Transition: An Updated Review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2021, 17, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineberg, N.A.; Menchón, J.M.; Hall, N.; Dell'Osso, B.; Brand, M.; Potenza, M.N.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Cirnigliaro, G.; Lochner, C.; Billieux, J.; Demetrovics, Z.; Rumpf, H.J.; Müller, A.; Castro-Calvo, J.; Hollander, E.; Burkauskas, J.; Grünblatt, E.; Walitza, S.; Corazza, O.; King, D.L.; Stein, D.J.; Grant, J.E.; Pallanti, S.; Bowden-Jones, H.; Ameringen, M.V.; Ioannidis, K.; Carmi, L.; Goudriaan, A.E.; Martinotti, G.; Sales, C.M.D.; Jones, J.; Gjoneska, B.; Király, O.; Benatti, B.; Vismara, M.; Pellegrini, L.; Conti, D.; Cataldo, I.; Riva, G.M.; Yücel, M.; Flayelle, M.; Hall, T.; Griffiths, M.; Zohar, J. Advances in problematic usage of the internet research - A narrative review by experts from the European network for problematic usage of the internet. Compr Psychiatry. 2022, 118, 152346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the smartphone addiction scale in a younger population. Klin. Psikofarmakol. Bul. -Bull. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 226–234. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Phillips, J.G. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005, 8, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.D. Gambling on the internet: a brief note. Journal of Gambling Studies 1996, 12, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León Méndez, M.; Padrón, I.; Fumero, A.; Marrero, R.J. Effects of internet and smartphone addiction on cognitive control in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review of fMRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2024, 159, 105572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrzus, Cornelia. (2020). Processes of personality development: An update of the TESSERA framework. [CrossRef]

- Shiner, R.L. How shall we speak of children's personalities in middle childhood? A preliminary taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 1998, 124, 308–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.; Cho, I.; Kim, E.J. Structural Equation Model of Smartphone Addiction Based on Adult Attachment Theory: Mediating Effects of Loneliness and Depression. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2017, 11, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotaiuti, P.; Mancone, S.; Corrado, S.; De Risio, A.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Girelli, L.; Chirico, A. Internet addiction in young adults: The role of impulsivity and codependency. Front Psychiatry. 2022, 13, 893861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fischer-Grote, L.; Kothgassner, O.D.; Felnhofer, A. Risk factors for problematic smartphone use in children and adolescents: a review of existing literature. Neuropsychiatr Klin Diagnostik, Ther und Rehabil Organ der Gesellschaft Osterr Nervenarzte und Psychiater. 2019, 33, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. How does self-esteem affect mobile phone addiction? The mediating role of social anxiety and interpersonal sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterka-Bonetta, J.; Sindermann, C.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. Personality Associations With Smartphone and Internet Use Disorder: A Comparison Study Including Links to Impulsivity and Social Anxiety. Front public Heal. 2019, 7, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, D.; Sindermann, C.; Häckel, D.; Settanni, M.; Elhai, J.D.; Montag, C. The association between the Big Five personality traits and smartphone use disorder: A meta-analysis. J Behav Addict. 2020, 9, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V.; Rabasca, A.B.F.Q.-C. Big Five Questionnaire-Children. Manuale. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali; 1998. pp. 3–83.

- Conte, S.; Ghiani, C.; Nicotra, E.; Bertucci, A.; Truzoli, R. Development and validation of the smartphone addiction risk children questionnaire (SARCQ). Heliyon. 2022, 8, e08874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnicott, D. Gioco e realtà. Fabbri Editore, editor. Milano; 1971.

- Cinti, M.E. Goldberg I. (1995). IAD. In: Internet Addiction Disorder: un fenomeno sociale in espansione. p. 6–7.

- Al-Barashdi, H. Smartphone Addiction among University Undergraduates: A Literature Review. J Sci Res Reports. 2015, 4, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liang, Y.; Mai, C.; Zhong, X.; Qu, C. General Deficit in Inhibitory Control of Excessive Smartphone Users: Evidence from an Event-Related Potential Study. Front Psychol. 2016, 7, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, J.; James, D. Exploring Addictive Consumption of Mobile Phone Technology. 2005.

- Wang, J.-L. The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Comput Human Behav. 2015, 53, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, M.; Leung, L. Linking Loneliness, Shyness, Smartphone Addiction Symptoms, and Patterns of Smartphone Use to Social Capital. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2014, 33, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PJ Flores, Addiction as an attachment disorder. Jason Aronson Inc. Publisher, Lanham (MD), 2004.

- Engelberg, E.; Sjöberg, L. Internet use, social skills, and adjustment. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004, 7, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster-Stratton, C.; Taylor, T. Nipping early risk factors in the bud: Preventing substance abuse, delinquency, and violence in adolescence through interventions targeted at young children (0-8 years). Prevention Science 2001, 2, 165192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izard, C.E. Translating emotion theory and research into preventive interventions. Psychological Bulletin 2002, 128, 796–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez de Albéniz Garrote, G.; Rubio, L.; Medina Gómez, B.; Buedo-Guirado, C. Smartphone Abuse Amongst Adolescents: The Role of Impulsivity and Sensation Seeking. Front Psychol. 2021, 12, 746626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ramey, C.T.; Ramey, S.L. Early learning and school readiness: Can early intervention make a difference? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly 2004, 50, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapee, R.M.; Kennedy, S.; Ingram, M.; Edwards, S.; Sweeney, L. Prevention and early intervention of anxiety disorders in inhibited preschool children. Journal of Counsulting Clinical Psychology 2005, 73, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, Hifizah; Setyaningrum, Putri; Novandita, Annisa. Permissive, Authoritarian, and Authoritative Parenting Style and Smartphone Addiction on University Students. Journal of Educational Health and Community Psychology. 2021, 10, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.; Hooker, E.; Rohleder, N.; Pressman, S. The Use of Smartphones as a Digital Security Blanket. Psychosomatic Medicine 2018, 80, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girela-Serrano, B.M.; Spiers, A.D.V.; Ruotong, L.; Gangadia, S.; Toledano, M.B.; Di Simplicio, M. Impact of mobile phones and wireless devices use on children and adolescents' mental health: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024, 33, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).