1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal diseases (MSDs) are a group of diseases affecting the skeletal system, muscles, joints and tissues and cause acute/chronic pain, impaired movement, and extensive health challenges. Reduced musculoskeletal health is recognized globally as having increased morbidity and mortality. The focus here is on the static nature of the musculoskeletal system. For example, bone and cartilage, the main tissues of the musculoskeletal system, have very limited intrinsic capacity for tissue regeneration, especially if the defect is large. Furthermore, this intrinsic repair capacity varies on the basis of individual factors such as age, metabolic condition, and disease severity [

1]. The global burden of musculoskeletal disorders is immense, with an estimated 1.71 billion individuals affected, thereby underscoring the urgent and pervasive clinical need for effective and minimally invasive regenerative therapies to mitigate pain, restore mobility, and improve the quality of life of countless individuals [

2].

The inherent complexity and avascular nature of cartilage and bone tissues present significant challenges to their self-repair mechanisms following injury or disease [

3]. The age-related decline in tissue regenerative capacity is associated with degradation of tissue homeostasis, and the catastrophic outcome of tissue injury clearly identifies a significant unmet medical requirement for compelling regenerative solutions [

4]. Current treatments, including autografts and allografts, often face limitations such as donor site morbidity, immune rejection, and a limited supply [

5]. The use of biomaterials as scaffolds to facilitate and control tissue repair and regeneration is another approach. Biomaterials describe a broad category of materials or substances, including the kind, quality, structure and ability or characteristics of a material used with or in the human body. Some biomaterials, such as hydroxyapatite ceramics, bioactive glasses or modified carbon materials, can bond with tissues or induce their regeneration (

Figure 1).

Thus, the bioapplications of hydrogels have attracted much interest and have been investigated, among other biomaterials, for several reasons, such as their biocompatibility, mechanical properties and ability to replicate the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

6]. Moreover, injectable hydrogels are another advantage because they allow minimally invasive interventions and more complex defect filling due to minimal surgical trauma [

7]. This review specifically focuses on injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone regeneration, explores the critical aspects of material properties, delivery strategies for bioactive molecules and cells, and current clinical applications.

Diseases of bones and cartilage are major causes of disability in the human population, and there are no known cures for such diseases [

8]. Osteochondral defects refer to a condition in which a piece of cartilage together with the underlying subchondral bone is damaged and are among the difficult problems faced by orthopedic surgeons in terms of lesion repair owing to the complexity of the interface between the bone and cartilage [

9]. Tissue engineering is an exciting strategy for bone regeneration and has advantages over conventional grafting techniques since it enhances bone healing [

10]. Bone tissue engineering (BTE), as an applied science or branch of knowledge that has received increased attention in the 21st century, is centered on the creation of suitable conditions to promote boned tissue growth. In cooperation with stem cells, biomaterial scaffolds and growth factors, BTE tends to create biological alternatives for the treatment of damaged bone tissue [

11,

12]. The development of BTE over the past few decades since the introduction of tissue engineering has highlighted the importance of scaffold materials. A wide variety of natural and synthetic biomaterials have been investigated in this regard [

13,

14]. Advanced Materials: Hydrogels are three-dimensional structures with high water absorbing capacities made from natural or artificial polymers and are used extensively in the biomedical sector [

15]. Their advantageous properties, including excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and tunability, make them ideal for in situ injection to fill irregular defects and precisely conform to lesion geometries. Hydrogels consist of physically or chemically cross-linked polymer networks [

16]. As the supporting structure for tissue organization, they offer a proper scaffold for cell attachment, division, movement, and differentiation; hence, they have a wide range of applications in tissue engineering and bone repair [

17,

18].

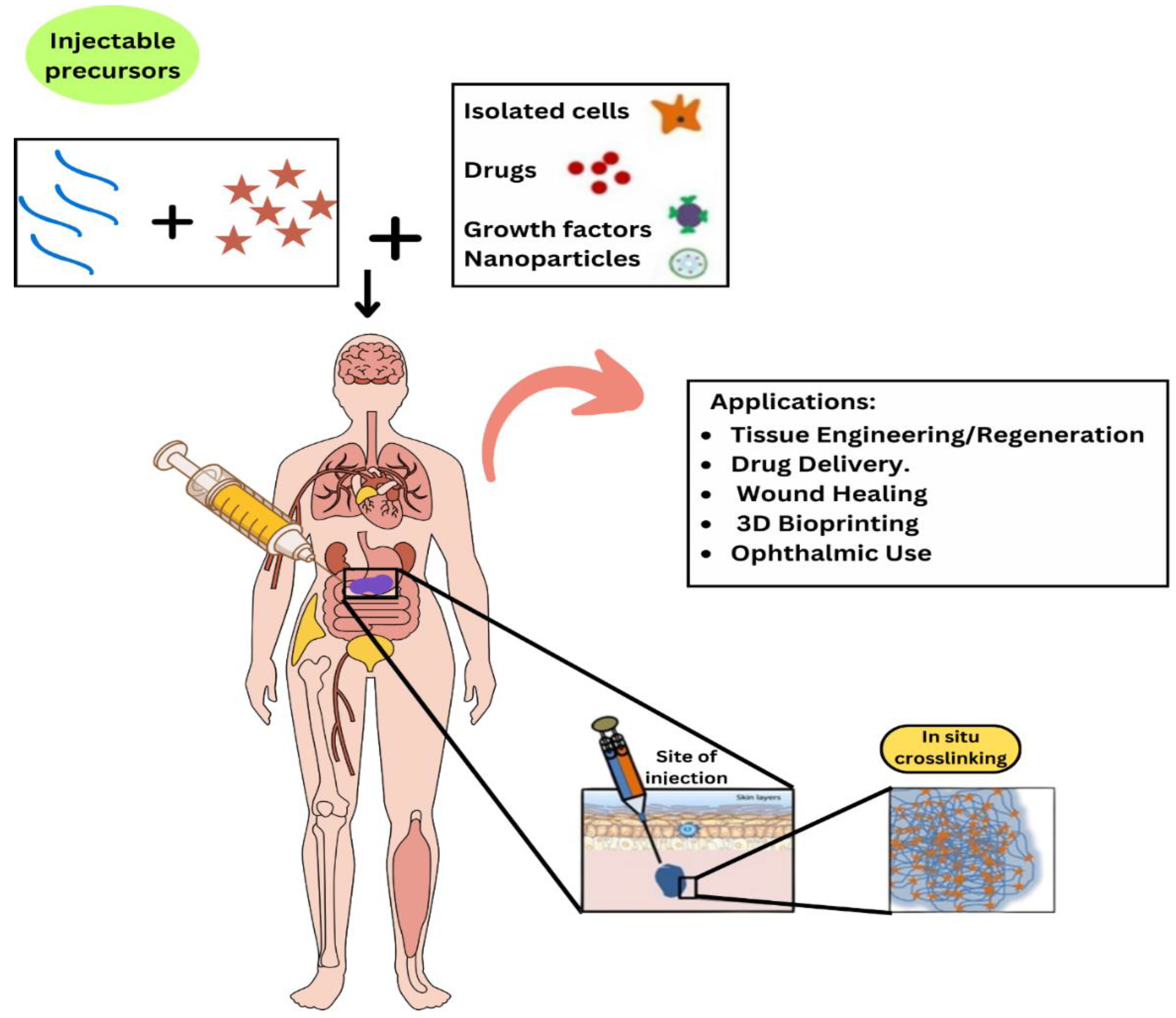

Injection hydrogels, specifically, are smart materials that have attracted significant interest in literature because of their ability to be injected into the body via a minimally invasive procedure and be directly deployed at the site of action [

19]. Owing to their viscoelastic and diffusive characteristics, they act as scaffolds that can also support tissue regeneration through mechanical stimulation, facilitate drug delivery and initiate host cell migration at the wound site for rapid repair of damaged tissue [

20]. This has placed injectable, and especially self-healing, hydrogels on the list of novel platform strategies aimed at tissue repair and regeneration in various fields, including cartilage repair [

21], cancer immunotherapy [

22], antibacterial therapies [

23], wound healing [

24,

25], and controlled drug release [

26].

The use of injectable hydrogels is most ideal for enhancing osteochondral tissues, mainly because of their similarities with the ECM in terms of their properties. In particular, through their high-water absorption and retention capacity as well as the porous nature of the material, traditional hydrogels are capable of encapsulating cells and simultaneously promoting intracellular functions and delivering signals that induce cell differentiation [

27,

28]. In addition, clinical utility emerges from the use of minimally invasive administration procedures and the capacity for naturally modeling irregularly shaped bone defects [

29]. This makes them excellent candidates for delivering therapeutics in a controlled manner, as illustrated in (

Figure 2) Injectable hydrogel-based drug delivery system for cartilage regeneration.

This review aims to systematically summarize information on injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue engineering. The first section describes the basic physical and chemical characteristics of both natural and synthetic hydrogels for these uses. After this, an overview of different methods for the delivery of growth factors and cells, which include the alteration, encapsulation and controlled release of hydrogels, is provided. Third, the present clinical use and results are briefly reviewed, with an emphasis on animal experiments and the clinic. Finally, we summarize and discuss the latter perspectives, further considerations, and remaining concerns, as well as the future of injectable hydrogel-based regenerative medicine for cartilage and bone regeneration.

2. Material Properties of the Injectable Hydrogels

Hydrogels, defined as three-dimensional networks of hydrophilic polymers capable of absorbing significant amounts of water, have garnered substantial attention in the biomedical field because of their biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and ability to mimic the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

31,

32]. Their importance stems from their applications in drug delivery, tissue engineering, and wound healing [

33]. The process of forming these networks can be crosslinked via chemical, physical, and enzymatic techniques. Chemical crosslinking involves the use of crosslinking agents that form covalent bonds to generate stable mechanically strong hydrogels [

34]. Physical crosslinking involves the formation of crosslinks through weak interactions such as hydrogen bonding, ion interactions or hydrophobic interactions, which are generally reversible and dependent on the medium [

35]. Enzymatic crosslinking offers a more biocompatible route, utilizing enzymes to catalyze the formation of covalent bonds under mild conditions [

36]. Injectability versatility is essential for delivering hydrogels in minimally invasive procedures, as it enables localized therapy without many side effects and a short healing time in patients [

37]. The characteristics of an injectable hydrogel include an increase in viscosity to allow the gel to be injected through a small-gauge needle and a short gelation time to ensure that the gel maintains the desired form and place after injection and is biocompatible [

38]. Furthermore, the hydrogel should exhibit suitable mechanical properties and degradation rates to support the desired therapeutic outcome [

39].

2.1. Specific Natural Polymer Types

Bone and cartilage tissue regeneration via natural polymers is one of the most promising branches in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. The integration of natural polymers into biomedical applications offers promising avenues for enhancing tissue repair and regeneration, yet significant knowledge gaps remain that warrant further investigation.

Table 1 provides a quick overview of the most relevant natural polymers being explored for cartilage and bone regeneration.

In the context of bone regeneration, the natural polymers used include collagen, gelatin and silk fibroin. In particular, for type I collagen, an ideal environment for osteogenesis is created when it is a part of the bone tissue. Nevertheless, it must often be combined with calcium phosphates to improve the mechanical properties and diminish immunogenicity. Other promising materials are chitosan and alginate, through which bioactive molecules can be incorporated to increase their osteoinductivity [

54,

55].

(

Figure 3) Huang et al. focused on the fabrication and analysis of hydrogels and subsequently employed them for the culture and identification of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). The mechanical properties of the composite hydrogels, specifically their stress‒strain relationships with various concentrations of cell-derived extracellular matrix (CECM) (0, 1, 1.5, and 2% w/v), were assessed alongside their compressive strength. Macroscopic differences between three hydrogel types—gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), gelatin-ECM (GE), and a GelMA/ECM-PFS composite—were documented, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed their microstructural morphology. Furthermore, pore characteristics, including porosity and pore size, were quantified for the three freeze-dried hydrogel types. The swelling capacity and biodegradation rates of these hydrogels were also evaluated. BMSCs were cultured, and their potential for differentiation into general, osteogenic (bone), adipogenic (fat), and chondrogenic (cartilage) lineages were assessed. Finally, flow cytometry analysis was used to determine the concentrations of several surface markers on the BMSC surface. The values are displayed as the means ± SDs, and significant differences were determined as *p < 0.05, while ‘ns’ represents no significance; all the experiments were conducted three times (n = 3). In the context of a given line, the proposed approach, which is based on the application of natural polymers for cartilage and bone tissue engineering, is promising because of the biocompatibility and bioactivity of the materials. In a recently published study, the authors explained how gelatin methacrylate (GelMA), a modified gelatin, was used in composites with a cartilage-derived extracellular matrix (ECM). Researchers have combined these peptides with a peptide sequence (PFS) to increase cell recruitment and chondrogenesis. This study highlights the utility of using natural polymers to create scaffolds for tissue engineering while highlighting hyaluronic acid as an important ECM component involved in cell recruitment [

56].

The use of natural polymers is a widely developing approach for cartilage and bone tissue engineering applications because of their inherent biocompatibility and bioactivity. Among these, collagen, particularly type I collagen, is known to promote osteogenesis, often requiring reinforcement with calcium phosphates to improve mechanical properties and reduce immunogenicity. Similarly, the characteristics of chitosan and alginate are important, which implies the possibility of incorporating bioactive molecules, thereby increasing osteoinductivity. However, turning to cartilage repair in this new direction involves the use of natural polymers to create scaffolds for tissue engineering. One such example is a study employing gelatin methacrylate (GelMA), a modified gelatin, and an extracellular matrix (ECM) derived from cartilage, which is further enhanced with a peptide sequence (PFS) to promote cell recruitment and chondrogenesis, thus highlighting the crucial role of hyaluronic acid within the ECM.

In a study by Huang et al., like the work performed in this investigation, the authors sought to investigate the possibility of applying hydrogels derived from natural polymers to culture BMSCs for the purpose of bone regeneration. In particular, they synthesized hydrogels from two types of gelatin: gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA), gelatin-ECM (GE), and the GelMA/ECM-PFS composite. With respect to the mechanical characteristics of these hydrogels, they studied the stress, strain and compression modulus relative to various CECM concentrations. Additionally, the nature of the hydrogels’ microstructure was described by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), pore parameters, water uptake and biodegradation. Finally, they assessed the potential of BMSCs to differentiate into different lineages after they were cultured on these scaffolds. Therefore, by systematically describing these hydrogels, this research contributes to the understanding of how the chemistry of natural polymer-based matrices can modulate the cell response to improve regenerative medicine applications [

56].

2.2. Synthetic Hydrogels

Polymer hydrogels, especially PEG-based hydrogels, are significant for tissue engineering, especially for cartilage and bone tissue regeneration. PEG hydrogels are characterized by their biocompatibility, hydrophilicity, and tunable properties, making them suitable carriers for growth factors essential for tissue repair. Recent works have shown the compatibility of PEG-based systems in loading these growth factors and sustain their ability for therapeutic exploitation and longer half-lives [

57,

58]. The application of synthetic injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue engineering has emerged as one of the most popular approaches in recent years, mainly because of the high ECM likeness and tissue-friendly environment provided by hydrogels. Hydrogels derived from natural polymers were described by Vlierberghe et al. (2011), who focused on their importance in tissue engineering applications. This body of research has been built upon subsequent studies that delve deeper into specific hydrogel formulations and their regenerative capabilities [

59]. In a study published in 2022, Lee et al. reported that thermosensitive hydrogels can be designed for cartilage tissue engineering because of their ability to have desirable mechanical characteristics and high biocompatibility. These hydrogels can change to a gel form at physiological temperatures, so the application methods are minimally invasive [

60]. Chen et al. (2023) further focused on the hydrogel composition and reported that a new injectable hydrogel prepared from gelatin and hyaluronic acid promoted chondrocyte proliferation and matrix synthesis in culture [

61]. Furthermore, Liu et al. reported that these hydrogels can be used for delivering stem cells for cartilage repair; their outcomes were described as promising in animal studies [

62]. However, several limitations remain, including information gaps concerning the sustained performance of these hydrogels after their implantation in model organisms. Subsequent studies could investigate other imaging modalities to assess hydrogel breakdown and tissue incorporation in real time. Furthermore, studies on the design of stimuli-responsive elements in hydrogels might improve their performance via the incorporation of stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems, which release active agents in response to external stimuli, according to Utech and Boccaccini (2015) [

63].

2.3. Hybrid Hydrogels

Natural and synthetic hydrogels have created a novel crossroad of hybrid systems for improving tissue engineering strategies, with a particular focus on bone and cartilage tissue repair. The growing appreciation of the need to replicate the physical and biological characteristics of native tissues has led to the enhancement of these advanced materials. The use of natural polymers, which are essential for cell compatibility and bioactivity, when combined with the superior mechanical properties of synthetic polymers increases the compatibility of the implant with the host tissue [

55]. These characteristics make it easier for hybrid hydrogels to solve the multiple challenges posed in the field of tissue engineering and improve the rate of tissue regeneration.

These novel hydrogels are fabricated by blending different materials and have unique characteristics, which allows further exploration of hydrogels for guided bone regeneration, since addressing the complexity of tissue repair is a great challenge. (

Figure 4) illustrates a typical architecture of a bilayered hybrid hydrogel for guided bone regeneration, adapted from [

64]. The system consists of two key components: an electrospun, fibrous membrane layer (typically made of PLGA) to act as a physical barrier preventing the infiltration of soft tissue and a self-healing hydrogel layer containing bioactive components. The self-healing hydrogel layer is fabricated to have dynamic and covalent bonds that are able to repair mechanical damage while delivering bioactive components, such as nHA, gradually to the bone defect site, promoting bone formation and integration. This synergistic combination of barrier function and bioactive delivery within a single platform offers great potential for the development of advanced strategies for bone tissue engineering.

One promising direction is the engineering of cartilage-like protein hydrogels through entanglement, which has shown potential in mimicking the native extracellular matrix, thereby enhancing cell adhesion and proliferation [

57]. These hydrogels have the potential to accommodate the MSCs necessary for proper tissue engineering/regeneration. Furthermore, the development of living injectable porous hydrogel microspheres, which can enhance the paracrine ability of MSCs, has led to new developments. These hydrogels not only stimulate the native environment but also attract endogenous stem cells and increase the ability to stimulate tissue regeneration for the treatment of osteoarthrosis and other diseases associated with degenerative joint pathology [

65]. These hydrogels may be useful for creating the right supportive culture media for mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which is pivotal in tissue engineering. In addition, the development of living injectable porous hydrogel microspheres has led to the enhanced paracrine efficiency of MSCs, which constitutes a major advancement. These hydrogels not only improve the local niche but also call native MSCs, which improve the regenerative potential for arthritis and other degenerative joint diseases [

66]. Furthermore, studies have highlighted the versatility of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels as drug delivery systems that support osteogenic substance delivery, thus promoting bone healing [

67]. Self-healing hydrogels are also very smart-responsive hydrogels that operate in accordance with certain stimuli from the outside and are also extraordinary inventions in this field. These hydrogels can also self-assemble to regulate encapsulated and non-encapsulated therapeutic agents, alter the local immune status and increase osteogenesis, which could be useful for bone tissue engineering [

68]. The incorporation of black phosphorus nanosheets in hydrogel formulations improves the therapeutic aspects of hydrogels, a common foundation for more advanced hydrogel combinations for bone defect treatment [

65].

Hybrid hydrogels represent a promising avenue for advancing cartilage and bone regeneration. As research progresses, continued exploration of innovative materials, smart design strategies, and comprehensive evaluations of hydrogel performance will be essential to overcome existing challenges and optimize their therapeutic applications.

3. Desired Characteristics for Tissue Engineering

Tissue engineering is a relatively new field with the goal of constructing new functional tissues or organs by using biologic three-dimensional matrices on which cells may grow and develop. Ideal properties considered important for the tissue engineering of cartilage and bone include mechanical properties, biocompatibility, degradation characteristics, and rheological properties such that the material can be easily injected.

3.1. Mechanical Strength

Mechanical strength is a critical factor in tissue engineering, particularly for applications involving load-bearing tissues such as bone. As suggested by Sheikh et al. (2015), there is a need for the development of new biodegradable materials or improvements in existing materials because all current biodegradable devices are appropriate merely for use in low-load-bearing applications. The physicochemical characteristics of the materials used, including the mechanical properties of the polymers, ceramics, and magnesium alloys, are essential for scaffold construction and should resist external forces acting in vivo [

69]. Furthermore, advancements in hydrogel technology have demonstrated that supramolecular adhesive hydrogels can exhibit tunable mechanical strength, making them adaptable to the mechanical demands of various tissues [

70]. These hydrogels not only provide structural support but also promote cell adhesion and proliferation, which are vital for successful tissue integration. Studies have shown that materials such as PEG-GelMA composites can be engineered to possess specific mechanical and biological properties, supporting cell adhesion and 3D network formation [

71].

3.2. Biocompatibility

The compatibility of a scaffold is one of the most important factors that defines the success of tissue engineering scaffolds, as it describes the ability of a scaffold to integrate with host tissues. In their recent study, Naahidi et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of the interface formed at the material‒tissue interface [

72]. Hydrogels derived from collagen and hyaluronic acid have demonstrated good results concerning cell proliferation and safe surgery via minimally invasive approaches [

71]. The biocompatibility and mechanical properties of electrospun poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) scaffolds, with an emphasis on bone and cartilage applications, have been highlighted by Wei et al. (2022) [

73]. Additionally, chitosan-gelatin-agarose hydrogels doped with halloysite nanotubes have exhibited improved biocompatibility and mechanical strength, showing their capacity to promote neovascularization, a critical aspect of tissue repair [

74].

3.3. Degradation Profiles

The degradation behavior of scaffolds is significant, as they should support tissues that are regenerating while assimilating into the body without negative effects. Several studies have shown that hydrogels such as oxidized alginate have shorter degradation times to enable successful interactions with localized tissue [

75]. Additionally, the ability of the system to achieve enzymatic degradation in PEG-GelMA hydrogels to complement the properties mentioned in engineered tissue needs to guarantee that scaffolds can degrade as new tissues grow [

71]. These results clearly highlight the need to design materials with predetermined degradation rates relevant to the healing process.

3.4. Injectability

Biocompatibility is a major requirement of scaffolds for cartilage and bone tissue engineering since their injectability enables minimally invasive surgical operations. The synthesis of stimuli-responsive hydrogels has therefore highlighted the ability of a material not only to respond to the mechanical forces required for tissue formation but also to be biocompatible during injection. Hydrogels that can be applied through injections, such as those made of biocompatible materials, can conform to irregular defect sites and enable site-specific deposition to promote tissue repair [

76].

4. Delivery Strategies for Enhanced Tissue Regeneration

Tissue regeneration is a highly complex process that requires complex approaches for delivering the growth factors and other agents necessary for tissue repair. Advanced hydrogel and nanotechnology materials science has significantly improved the bioavailability and therapeutic effect of these agents.

4.1. Delivery Strategies Overview

4.1.1. Cell Encapsulation

Cell encapsulation is crucial in designing an environment that reflects native tissue and enhances the viability and functionality of cells. In this context, the application of hydrogels has been widely reviewed. New developments in hydrogel engineering have ranked porosity and microstructure as key factors in providing nutrients and cell response [

77]. Adaptable hydrogels enabling 3D cell encapsulation to have also emerged as promising platforms, allowing for localized modifications that support complex cellular functions while maintaining structural integrity [

78]. Furthermore, advancements in porous hydrogels indicate that the porous structure of hydrogels enhances nutrient diffusion and promotes cell growth to enhance the outcomes of tissue regeneration [

79]. The incorporation of microfluidic technologies in the fabrication of micro- and nanostructures adds to the application of creating scaffolds that promote cell encapsulation and achieve the desired controlled release [

80].

4.1.2. Controlled Release of Growth Factors

The role of growth factors in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is crucial given their therapeutic potential. However, their short half-lives and associated side effects present significant challenges. However, their half-life is short, and their use is characterized by various side effects that are very demanding. Current studies have investigated the application of hydrogels as a system of controlled release delivery where growth factors can be coaxed to be sequestered [

81]. This approach addresses the issues of rapid proteolysis and burst release, significantly enhancing the overall effectiveness of tissue regeneration methods.

Chitosan is a biocompatible biopolymer that forms structures that can also be used as carriers of growth factors and therapeutics [

82]. The progressive release of therapeutics from chitosan-based biomaterials not only increases the effectiveness of biomaterials in stimulating tissue repair but also presents a suitable approach for the controlled delivery of growth factors in various tissues. Moreover, nanohydroxyapatite (n-HAp) has emerged as a promising material for bone tissue engineering because of its ability to mimic human bone minerals [

83]. Through the coating of n-HAp composites with bioactive factors, various researchers have shown that enhanced bone defect healing is a sign of the prospect of including mineralizing agents in delivery systems.

Zhang et al. (2023) reviewed the effectiveness of PAG/AG hydrogels incorporated with heparin for bFGF delivery in terms of their sustained release. Another finding of the study was that the release of bFGF was directly proportional to the concentration of heparin incorporated in the hydrogel-based system and that a higher concentration of heparin resulted in slower release rates. Specifically, the cumulative percentages of gel release factors after 3 weeks were 65.7% for 0.5% heparin, 61.1% for 1.0% heparin and 58.9% for 2.0% heparin, indicating that heparin is very effective in controlling the release kinetics of GFs [

84].

In another innovative approach, a study by Lee et al. (2019) utilized 3D printing technology to create geometrically complex hydrogel structures that encapsulated GFs. This method facilitated the means of controlling the release rates through the incorporation of various thicknesses of hydrogel layers into the structure. The data obtained here showed that increasing the shell thickness considerably decreased the release rate of GF, allowing for the divergence of a delivery system controlled according to tissue engineering needs. This work also presented a mathematical model to determine the release rate of GF for hydrogel structure geometries, which expands the knowledge on how altering structures can affect drug delivery [

85].

4.1.3. Incorporation of Mineralizing Agents

The integration of mineralizing agents into scaffolding materials is critical for enhancing tissue regeneration, particularly in bone applications. New approaches to the immobilization of bioactive molecules with a scaffold can increase the growth factors needed for tissue regeneration [

86]. These strategies stress the notion of controlled release systems, which are crucial for bone regeneration. Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels and drug delivery systems have also been reported as other remarkable processes of bone regeneration. Since PEG is hydrophilic and biocompatible, it may be functionalized via various approaches that can enhance it as a drug delivery system. This paper also discusses PEG-based systems to obtain information concerning enhanced delivery systems for increasing the regenerative impact on tissue [

67].

4.1.4. Drug Delivery for Infection Control

Managing infections during tissue regeneration is paramount, as infections can significantly impede healing processes. In the last few years, progress in the field of drug delivery systems, such as the use of DFO@ZIF-8 nanoparticles, has yielded positive results in terms of angiogenesis and osteogenesis, with the ability to control infection [

87]. This approach also reinforces the importance of delivery systems in improving the quality of tissue regeneration.

In addition, progress in intelligent biomaterials that control drug release has led to promising modalities for cartilage repair [

88]. By tailoring the release of therapeutics, these materials can create a conducive environment for effective tissue regeneration, demonstrating the importance of sophisticated delivery strategies across various tissue types.

5. Major Applications of Injectable Hydrogels

Injectable hydrogels have become a vital component in various biomedical applications (

Figure 5) due to their unique properties, including biocompatibility, biodegradability, and the ability to form in situ.

5.1. Major Applications of Injectable Hydrogels

The following table (

Table 2) presents a comparative analysis of the natural and synthetic hydrogel biomaterials commonly used in cartilage tissue engineering. It is useful for researchers, students and other professionals as it provides an overview of the main benefits and drawbacks of each type of material. This helps when choosing the right hydrogel for use in regeneration medicine due to its properties that enable sound decision making. As highlighted in recent literature, injectable hydrogels are particularly useful in tissue engineering where they can serve as sole supportive structures for tissue regeneration. Certain polymer-based hydrogels have shown promise in bone fracture and cartilage repair, mimicking the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) [

67]. Specifically, chitosan-based nanoparticles incorporated into hydrogels have been shown to enhance localized drug delivery, promoting the regeneration of damaged tissues [

89]. In addition, the preparation of PEG-based hydrogels has been highlighted as versatile for delivering osteogenic factors leading to enhanced bone healing [

90]. However, several questions still arise, especially in the deeper understanding of these hydrogels’ biocompatibility and degradation rates as a function of time in vivo. The limitations of this study should be addressed in future research as follows: Long-term efficacy must be evaluated in terms of attenuation of hydrogel formulations and its biodistribution and interaction with surrounding tissues.

5.2. Drug Delivery Systems

Hydrogels have been extensively studied for their role in wound healing, particularly due to their ability to maintain a moist environment and deliver therapeutic agents to promote healing [

106,

107]. Recent studies show the effectiveness of pH sensitive hydrogels with adhesion property as they provide the means to close the wound and fight against bacterial infection [

108]. Bioactive hydrogels have also been shown to enhance skin regeneration post-injury, demonstrating their potential in treating chronic wounds [

109]. Nevertheless, there is still a need for more research on the scalability of these hydrogels for clinical use. Future studies could explore the manufacturing processes and regulatory pathways required to bring these innovative wound dressings to market.

5.3. 3D Bioprinting

Hydrogels used in 3D bioprinting is a relatively new field of study. The literature of the present time shows that hydrogels can be modified for fabrication of complicated tissue architecture but there is a lack of detailed analysis of their mechanical and biological performance upon 3D bioprinting [

90,

110]. Further studies should be conducted to improve the hydrogel properties for applications in 3D bioprinting with reference to the bonding between the bioink and printed structures to improve the cell survival and functionality.

5.4. Ophthalmic Applications

The application of hydrogels in ophthalmic uses is an area that warrants further investigation. The biocompatibility and moisture-retaining properties of hydrogels suggest their potential in ocular drug delivery and corneal repair [

111]. However, scientific literature does not include numerous comprehensive studies that illustrate the relationships between hydrogels as well as their impact on ocular tissues. In regard to future work the following needs to be established: The action of hydrogel formulations need to be investigated more widely for use in ocular therapeutics, specifically to discover formulations which allow controlled release of medication therefore decreasing inflammation or irritation of ocular tissues.

5.5. Wound Healing Applications

Hydrogels have been extensively studied for their role in wound healing, particularly due to their ability to maintain a moist environment and deliver therapeutic agents to promote healing [

106,

107]. Recent studies show the effectiveness of pH sensitive hydrogels with adhesion property as they provide the means to close the wound and fight against bacterial infection [

108]. Bioactive hydrogels have also been shown to enhance skin regeneration post-injury, demonstrating their potential in treating chronic wounds [

109]. Nevertheless, there is still a need for more research on the scalability of these hydrogels for clinical use. Future studies could explore the manufacturing processes and regulatory pathways required to bring these innovative wound dressings to market.

6. Limitations and Future Directions

One of the primary challenges in the development of injectable hydrogels is the effective delivery of growth factors, which are crucial for enhancing tissue regeneration. According to Shan and Wu (2023), although hydrogels enhance the delivery of growth factors through controlled release media, issues such as the complexity of optimizing multiple release profiles and ensuring the bioactivity of encapsulated factors persist [

81]. However, substantial challenges remain in achieving the required mechanical properties for load-bearing structures in cartilage and bone applications. Future research should focus on developing hydrogels that can respond to physiological stimuli to enable the spatiotemporal release of growth factors and explore the incorporation of synergistic bioactive molecules.

In the context of osteoarthritis treatment, Li et al. (2023) introduced a living injectable porous hydrogel microsphere that enhances the paracrine activity of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Although such an approach shows some potential, additional improvement of the mechanical characteristics for withstanding the conditions within which cartilage and bone exist is yet to be achieved. The release and stability of the incorporated factors, particularly PDGF-BB, should be evaluated for the steady progression of therapy. Moreover, the applicability of the technique described for clinical applications and its possible integration with other regenerative approaches, such as gene therapy or three-dimensional bioprinting, remain to be investigated [

65]. Thus, another promising line of research involves the synthesis of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based hydrogels, which, although highly biocompatible, demonstrate lower bioactivity than natural hydrogels. The difficulty lies in achieving the maximum mechanical strength found in load-bearing applications. According to Li et al. (2023), the addition of PEG to natural polymers may improve their osteoconductivity and bioactivity [

65]. However, incorporating the fabrication of smart hydrogels that are self-responsive to the records of the surroundings might enhance the regenerative functionalities of PEG-based systems in bone tissue engineering to a greater extent.

Other versatile injectable hydrogels have also been developed on the basis of their immunomodulatory functions and photothermal activity in eradicating bacteria during bone regeneration. Nevertheless, according to Sun et al. (2023), for a better understanding of the consequences for bone healing and immune reactions, more in vivo research should be performed [

67]. Further studies need to focus on enhancing the mechanical characteristics and bioactivity of hydrogels by adjusting their chemical properties and concentrations and testing the concept of targeted medicine delivery via the use of hydrogels as carriers for personalized treatments. Furthermore, an overarching theme in literature is the need for a deeper understanding of the interactions between hydrogels and biological tissues. In the work of Ghandforoushan et al. (2023), the authors noted that guaranteeing the reliability of injectable hydrogels in clinical practice is the reproducibility of the results. Further advancements should encourage stronger cooperation with other fields to develop novel hydrogel formulations with oriented application and investigate the application of hydrogels as part of multimodal repair strategies [

112]. Key challenges include optimizing mechanical properties, ensuring the bioactivity and stability of growth factors, and understanding interactions with biological tissues. Future studies should fill these gaps by creating new hydrogels that can respond to signals from the body, consider hybrids and study the effects of several hydrogels on improving the regenerative capabilities of injectable hydrogels in medical treatments.

7. Conclusions

Injectable hydrogels are promising and multifunctional systems that can successfully address important clinical issues associated with cartilage and bone repair. As this review has shown, these materials have several benefits: they can be implanted through minimally invasive procedures; their properties can be tailored to match those of the ECM; and they can also serve as carriers for cells, growth factors and mineralizing agents. The natural, synthetic and integrated characteristics of natural synthetic and hydrogel systems continue to be explored to explain the progress that has been made. From the viewpoint of improving the mechanical properties and biocompatibility of materials and carriers, such as collagen, alginate, and PEG-based polymers, to improve the design of hydrogels and their controlled release system, researchers are trying to innovate on these hydrogels. However, the advent of smart and stimuli-responsive hydrogels and the combination and incorporation of microfluidic and 3D printing technologies show potential and innovative development in this field. Considerable progress has been achieved, but many limitations and problems persist. Challenges such as maintaining the persistent biological activity of encapsulated growth factors, controlling the mechanical properties of load-bearing tissue, and understanding the relationship between hydrogels and surrounding tissues are considered core requirements for translation into practice. More investigations are needed to improve the material design, delivery methods, systems containing bioactive molecules, and application of individualized therapies through hydrogel systems. As a next step, efforts based on a multidisciplinary interdisciplinary approach involving material scientists, biologists and clinicians will be needed to unlock the full potential of injectable hydrogels. With such versatile materials, overcoming current difficulties and further developing new methods of cartilage and bone tissue regeneration that effectively enhance patients’ quality of life are possible. Further studies on the synthesis of new materials, the application of intelligent design thinking and comprehensive testing of injectable hydrogels clinically will provide the basis for the implementation of injectable hydrogels in routine clinical practice.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

Open access funding was provided by the Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research. No funding is involved while preparing the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

NA.

Acknowledgments

All the authors would like to acknowledge the Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Wardha and Research House, DMIHER, and Wardha for providing support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

MSDs: Musculoskeletal diseases

ECM: Extracellular matrix

PEG: Poly (ethylene glycol)

PVA: Poly (vinyl alcohol)

TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta

BMPs: Bone morphogenetic proteins

BTE: Bone tissue engineering

NFC: Nanofibrillated cellulose

SF: Silk fibroin

OA: Oxidized alginate

HA: Hyaluronic acid

GE: Gelatin-ECM

GelMA: Gelatin methacryloyl

PFS: Peptide sequence

SEM: Scanning electron microscopy

BMSCs: Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

CECM: Cell-derived extracellular matrix

DBM: Decellurized Bone Matri

PLGA: Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)

nHAp: nanohydroxyapatite

bFGF: basic fibroblast growth factor

DFO: Deferoxamine

ZIF-8: Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8

PDGF-BB: Platelet-derived growth factor BB

PAG/AG: Poly (acrylic acid-co-acrylamide)/agarose

References

- Briggs, A.M.; Cross, M.J.; Hoy, D.G.; Sànchez-Riera, L.; Blyth, F.M.; Woolf, A.D.; March, L. Musculoskeletal Health Conditions Represent a Global Threat to Healthy Aging: A Report for the 2015 World Health Organization World Report on Ageing and Health. Gerontol. 2016, 56, S243–S255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musculoskeletal health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions.

- Focsa, M.A.; Florescu, S.; Gogulescu, A. Emerging Strategies in Cartilage Repair and Joint Preservation. Medicina 2024, 61, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovev, I.; Sergeeva, A.; Geraskina, A.; Shaposhnikov, M.; Vedunova, M.; Borysova, O.; Moskalev, A. Aging and physiological barriers: mechanisms of barrier integrity changes and implications for age-related diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Manshaii, F.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Yin, J.; Yang, M.; Chen, X.; Yin, X.; Zhou, Y. Unleashing the Potential of Electroactive Hybrid Biomaterials and Self-Powered Systems for Bone Therapeutics. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, R.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, J.J.; Xue, J. Advances in the Development of Gradient Scaffolds Made of Nano-Micromaterials for Musculoskeletal Tissue Regeneration. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Damme, L.; Blondeel, P.; Van Vlierberghe, S. Injectable biomaterials as minimal invasive strategy towards soft tissue regeneration—an overview. J. Physics: Mater. 2020, 4, 022001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Yue, O.; Zheng, M.; Liu, X. Development of a multifunctional injectable temperature-sensitive gelatin-based adhesive double-network hydrogel. Biomaterials Advances 2021, 134, 112556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karami, P.; Laurent, A.; Philippe, V.; Applegate, L.A.; Pioletti, D.P.; Martin, R. Cartilage Repair: Promise of Adhesive Orthopedic Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battafarano, G.; Rossi, M.; De Martino, V.; Marampon, F.; Borro, L.; Secinaro, A.; Del Fattore, A. Strategies for Bone Regeneration: From Graft to Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhursani, S.A.; Ghobashy, M.M.; Al-Gahtany, S.A.; Meganid, A.S.; El-Halim, S.M.A.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, F.S.; Atia, G.A.N.; Cavalu, S. Application of Nano-Inspired Scaffolds-Based Biopolymer Hydrogel for Bone and Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Polymers 2022, 14, 3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.U.A.; Aslam, M.A.; Bin Abdullah, M.F.; Stojanović, G.M. Current Perspectives of Protein in Bone Tissue Engineering: Bone Structure, Ideal Scaffolds, Fabrication Techniques, Applications, Scopes, and Future Advances. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2024, 7, 5082–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseti, L.; Parisi, V.; Petretta, M.; Cavallo, C.; Desando, G.; Bartolotti, I.; Grigolo, B. Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering: State of the art and new perspectives. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 78, 1246–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.S.B.; Ponnamma, D.; Choudhary, R.; Sadasivuni, K.K. A Comparative Review of Natural and Synthetic Biopolymer Composite Scaffolds. Polymers 2021, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mredha, T.I.; Jeon, I. Biomimetic anisotropic hydrogels: Advanced fabrication strategies, extraordinary functionalities, and broad applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2022, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondiah, P.J.; Choonara, Y.E.; Kondiah, P.P.D.; Marimuthu, T.; Kumar, P.; Du Toit, L.C.; Pillay, V. A Review of Injectable Polymeric Hydrogel Systems for Application in Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2016, 21, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasheva, F.; Adilova, L.; Dyussenbinov, A.; Yernaimanova, B.; Abilev, M.; Akilbekova, D. Optimizing scaffold pore size for tissue engineering: insights across various tissue types. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1444986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gholap, A.D.; Rojekar, S.; Kapare, H.S.; Vishwakarma, N.; Raikwar, S.; Garkal, A.; Mehta, T.A.; Jadhav, H.; Prajapati, M.K.; Annapure, U. Chitosan scaffolds: Expanding horizons in biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 323, 121394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, H.; Abidnejad, R.; Fazeli, M.; Lipponen, J.; Niskanen, J.; Kontturi, E.; Seppälä, J.; Rojas, O.J. Innovations in hydrogel-based manufacturing: A comprehensive review of direct ink writing technique for biomedical applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 324, 103095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xu, L. Recent advancements in hydrogels as novel tissue engineering scaffolds for dental pulp regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.-X.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Liu, W.; Wang, H.-C.; Ren, C.; Zhang, Y.-Q.; Shi, T.-L.; Chen, W. Cartilage tissue healing and regeneration based on biocompatible materials: a systematic review and bibliometric analysis from 1993 to 2022. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1276849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, K.; Huang, M.; Zhang, W.; Yu, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Multifunctional Nanoparticle-Loaded Injectable Alginate Hydrogels with Deep Tumor Penetration for Enhanced Chemo-Immunotherapy of Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 18604–18621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, R.; Cui, J.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, M.; Hamley, I.W.; Xiao, C.; Chen, L. An injectable antibacterial hydrogel with bacterial-targeting properties for subcutaneous suppuration treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 151137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Ma, B.; Hua, S.; Ping, R.; Ding, L.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X. Chitosan-based injectable hydrogel with multifunction for wound healing: A critical review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 333, 121952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Fan, C.; Li, Z.A.; Zheng, L.; Luo, B.; Li, Z.-P.; Lin, B.; Zha, Z.-G.; et al. Collagen fibril-like injectable hydrogels from self-assembled nanoparticles for promoting wound healing. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 32, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wei, H.; Yu, C.-Y. Injectable hydrogels as emerging drug-delivery platforms for tumor therapy. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, Y.; Wang, M.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W. Endogenous Tissue Engineering for Chondral and Osteochondral Regeneration: Strategies and Mechanisms. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 4716–4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, H.; Faheem, S.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Sarwar, H.S.; Jamshaid, M. A Comprehensive Review of Hydrogel-Based Drug Delivery Systems: Classification, Properties, Recent Trends, and Applications. Aaps Pharmscitech 2024, 25, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi AT, Taheri SA mohammad, Karamouz M, Sarhaddi R. Rising Innovations: Revolutionary Medical and Dental Breakthroughs Revolutionizing the Healthcare Field. Nobel Sciences; 2024.

- García-Fernández, L.; Olmeda-Lozano, M.; Benito-Garzón, L.; Pérez-Caballer, A.; Román, J.S.; Vázquez-Lasa, B. Injectable hydrogel-based drug delivery system for cartilage regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 110, 110702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Chan, H.-P.; Chung, T.-W.; Shu, C.-W.; Chuang, K.-P.; Duh, T.-H.; Yang, M.-H.; Tyan, Y.-C. Hydrogels: Properties and Applications in Biomedicine. Molecules 2022, 27, 2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, S.; Lee, H. Engineering Hydrogels for the Development of Three-Dimensional In Vitro Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saghazadeh, S.; Rinoldi, C.; Schot, M.; Kashaf, S.S.; Sharifi, F.; Jalilian, E.; Nuutila, K.; Giatsidis, G.; Mostafalu, P.; Derakhshandeh, H.; et al. Drug delivery systems and materials for wound healing applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 127, 138–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Atif, M.; Haseen, M.; Kamal, S.; Khan, M.S.; Shahid, S.; Nami, S.A.A. Synthesis, classification and properties of hydrogels: their applications in drug delivery and agriculture. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 10, 170–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Luo, H. Constructions and Properties of Physically Cross-Linked Hydrogels Based on Natural Polymers. Polym. Rev. 2022, 63, 574–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Peng, K.; Mitragotri, S. Covalently Crosslinked Hydrogels via Step-Growth Reactions: Crosslinking Chemistries, Polymers, and Clinical Impact. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, F.; Kehr, N.S. Recent Advances in Injectable Hydrogels for Controlled and Local Drug Delivery. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2020, 10, e2001341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertsch, P.; Diba, M.; Mooney, D.J.; Leeuwenburgh, S.C.G. Self-Healing Injectable Hydrogels for Tissue Regeneration. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 834–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, K. Current hydrogel advances in physicochemical and biological response-driven biomedical application diversity. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, C.R.; Moreira-Teixeira, L.S.; Moroni, L.; Reis, R.L.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Karperien, M.; Mano, J.F. Chitosan Scaffolds Containing Hyaluronic Acid for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part C: Methods 2011, 17, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.C.; Lall, R.; Srivastava, A.; Sinha, A. Hyaluronic Acid: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Trajectory. Front. Veter- Sci. 2019, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, H.; Cai, Y.; Song, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, W. 3D printing of bone and cartilage with polymer materials. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1044726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, D.A.; Wu, D.; He, F.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Shi, D.; Liu, Q.; Ni, N.; Pakvasa, M.; et al. Applications of Biocompatible Scaffold Materials in Stem Cell-Based Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 603444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, P.; Laurent, A.; Philippe, V.; Applegate, L.A.; Pioletti, D.P.; Martin, R. Cartilage Repair: Promise of Adhesive Orthopedic Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Ma, Y.; Yao, X.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Li, C.; Lin, J.; He, Q.; Leptihn, S.; Ouyang, H. Advanced hydrogels for the repair of cartilage defects and regeneration. Bioact Mater. 2020, 6, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Q.; Deng, C.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lu, T. Exquisite design of injectable Hydrogels in Cartilage Repair. Theranostics 2020, 10, 9843–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zeng, X.; Ma, C.; Yi, H.; Ali, Z.; Mou, X.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; He, N. Injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue engineering. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, S.; Wang, N.; Kang, R.; Xie, L.; Liu, X. Therapeutic application of hydrogels for bone-related diseases. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 998988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giorgio, G.; Matera, B.; Vurro, D.; Manfredi, E.; Galstyan, V.; Tarabella, G.; Ghezzi, B.; D’angelo, P. Silk Fibroin Materials: Biomedical Applications and Perspectives. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janmohammadi, M.; Nazemi, Z.; Salehi, A.O.M.; Seyfoori, A.; John, J.V.; Nourbakhsh, M.S.; Akbari, M. Cellulose-based composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering and localized drug delivery. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Song, Q.; Liu, S.; Pei, W.; Wang, P.; Zheng, L.; Huang, C.; Ma, M.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, K. Advanced applications of cellulose-based composites in fighting bone diseases. Compos. Part B: Eng. 2022, 245, 110221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, F.; Yu, Y.; Liu, S.; Ming, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Jin, Y. Advancing application of mesenchymal stem cell-based bone tissue regeneration. Bioactive Materials 2020, 6, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemian, A. Evaluation of the effectiveness of 3D bone matrices osteoinduction by using in vitro and in vivo models. [Internet] [thesis]. University of Leicester; 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 19]. Available from: https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/Evaluation_of_the_effectiveness_of_3D_bone_matrices_osteoinduction_by_using_in_vitro_and_in_vivo_models_/25019765/1.

- Shi, C.; Yuan, Z.; Han, F.; Zhu, C.; Li, B. Polymeric biomaterials for bone regeneration. Ann. Jt. 2016, 1, 27–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, M.; Born, G.; Chaaban, M.; Scherberich, A. Natural Polymeric Scaffolds in Bone Regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Li, P.; Chen, M.; Peng, L.; Luo, X.; Tian, G.; Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Tian, Q.; Li, H.; et al. Hydrogel composite scaffolds achieve recruitment and chondrogenesis in cartilage tissue engineering applications. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Li, L.; Bian, Q.; Xue, B.; Jin, J.; Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Li, H. Cartilage-like protein hydrogels engineered via entanglement. Nature 2023, 618, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Wu, F. Hydrogel-Based Growth Factor Delivery Platforms: Strategies and Recent Advances. Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, e2210707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Schacht, E. Biopolymer-Based Hydrogels As Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering Applications: A Review. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H. Injectable hydrogels delivering therapeutic agents for disease treatment and tissue engineering. Biomater. Res. 2018, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.-K.; Kim, S.; Baljon, J.J.; Wu, B.M.; Aghaloo, T.; Lee, M. Microporous methacrylated glycol chitosan-montmorillonite nanocomposite hydrogel for bone tissue engineering. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zeng, X.; Ma, C.; Yi, H.; Ali, Z.; Mou, X.; Li, S.; Deng, Y.; He, N. Injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue engineering. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utech, S.; Boccaccini, A.R. A review of hydrogel-based composites for biomedical applications: enhancement of hydrogel properties by addition of rigid inorganic fillers. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 51, 271–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Kong, M.; Li, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, Q.; Teng, W. Self-healing hybrid hydrogels with sustained bioactive components release for guided bone regeneration. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Lin, J.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Cui, W. Living and Injectable Porous Hydrogel Microsphere with Paracrine Activity for Cartilage Regeneration. Small 2023, 19, e2207211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, H.; Pu, A.; Li, W.; Ban, K.; Xu, L. Hybrid assembly of polymeric nanofiber network for robust and electronically conductive hydrogels. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Cui, Y.; Yuan, B.; Dou, M.; Wang, G.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Yin, W.; Wu, D.; Peng, C. Drug delivery systems based on polyethylene glycol hydrogels for enhanced bone regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1117647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Liu, H.; Li, D.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, P.; Chen, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Z.; Cai, L. Smart-Responsive Multifunctional Therapeutic System for Improved Regenerative Microenvironment and Accelerated Bone Regeneration via Mild Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Sci. 2023, 11, e2304641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Verma, V.; Rashid, H.; Glogauer, M. Biodegradable Materials for Bone Repair and Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2015, 8, 5744–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebsch, N.; Lippens, E.; Lee, K.; Mehta, M.; Koshy, S.T.; Darnell, M.C.; Desai, R.M.; Madl, C.M.; Xu, M.; Zhao, X.; et al. Matrix elasticity of void-forming hydrogels controls transplanted-stem-cell-mediated bone formation. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 1269–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Hu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Su, J. Recent Advances in Design of Functional Biocompatible Hydrogels for Bone Tissue Engineering. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naahidi, S.; Jafari, M.; Logan, M.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Bae, H.; Dixon, B.; Chen, P. Biocompatibility of hydrogel-based scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Cui, J.; Lin, K.; Xie, J.; Wang, X. Recent advances in smart stimuli-responsive biomaterials for bone therapeutics and regeneration. Bone Res. 2022, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslahi, N.; Abdorahim, M.; Simchi, A. Smart Polymeric Hydrogels for Cartilage Tissue Engineering: A Review on the Chemistry and Biological Functions. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 3441–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afewerki, S.; Sheikhi, A.; Kannan, S.; Ahadian, S.; Khademhosseini, A. Gelatin-polysaccharide composite scaffolds for 3D cell culture and tissue engineering: Towards natural therapeutics. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2018, 4, 96–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.O.; Vorwald, C.E.; Dreher, M.L.; Mott, E.J.; Cheng, M.; Cinar, A.; Mehdizadeh, H.; Somo, S.; Dean, D.; Brey, E.M.; et al. Evaluating 3D-Printed Biomaterials as Scaffolds for Vascularized Bone Tissue Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2014, 27, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annabi, N.; Nichol, J.W.; Zhong, X.; Ji, C.; Koshy, S.; Khademhosseini, A.; Dehghani, F. Controlling the Porosity and Microarchitecture of Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering. Tissue Eng. Part B: Rev. 2010, 16, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Heilshorn, S.C. Adaptable Hydrogel Networks with Reversible Linkages for Tissue Engineering. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3717–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Luo, D.; Liu, Y. Effect of the nano/microscale structure of biomaterial scaffolds on bone regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.M.; Sant, S.; Masaeli, M.; Kachouie, N.N.; Zamanian, B.; Lee, S.-H.; Khademhosseini, A. Fabrication of three-dimensional porous cell-laden hydrogel for tissue engineering. Biofabrication 2010, 2, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, B.; Wu, F. Hydrogel-Based Growth Factor Delivery Platforms: Strategies and Recent Advances. Adv. Mater. 2023, 36, e2210707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Zharkinbekov, Z.; Raziyeva, K.; Tabyldiyeva, L.; Berikova, K.; Zhumagul, D.; Temirkhanova, K.; Saparov, A. Chitosan-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Regeneration. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, X.; Zhang, D.; Liu, K.; Zhao, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Nano-Hydroxyapatite Composite Scaffolds Loaded with Bioactive Factors and Drugs for Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, W.; Piao, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, H. Controlled Release of Growth Factor from Heparin Embedded Poly(aldehyde guluronate) Hydrogels and Its Effect on Vascularization. Gels 2023, 9, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Berry, D.; Moran, A.; He, F.; Tam, T.; Chen, L.; Chen, S. Controlled Growth Factor Release in 3D-Printed Hydrogels. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1900977–e1900977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szwed-Georgiou, A.; Płociński, P.; Kupikowska-Stobba, B.; Urbaniak, M.M.; Rusek-Wala, P.; Szustakiewicz, K.; Piszko, P.; Krupa, A.; Biernat, M.; Gazińska, M.; et al. Bioactive Materials for Bone Regeneration: Biomolecules and Delivery Systems. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 5222–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, L.; Li, R.; Wan, Q.; Pei, X.; Chen, J.; et al. Drug-Delivery Nanoplatform with Synergistic Regulation of Angiogenesis–Osteogenesis Coupling for Promoting Vascularized Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 17543–17561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Wang, J.; Fu, Y.; Pan, H.; He, H.; Gan, Q.; Liu, C. Smart Biomaterials for Articular Cartilage Repair and Regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafernik, K.; Ładniak, A.; Blicharska, E.; Czarnek, K.; Ekiert, H.; Wiącek, A.E.; Szopa, A. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles as Effective Drug Delivery Systems—A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, J.; Li, D.; Dong, W.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Deng, B. Mussel-Inspired Multifunctional Hydrogels with Adhesive, Self-Healing, Antioxidative, and Antibacterial Activity for Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 16515–16525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, K.; Fabra, G.T.; Bozkurt, Y.; Pandit, A. Bioactive potential of natural biomaterials: identification, retention and assessment of biological properties. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, J.F.; Silva, G.A.; Azevedo, H.S.; Malafaya, P.B.; Sousa, R.A.; Silva, S.S.; Boesel, L.F.; Oliveira, J.M.; Santos, T.C.; Marques, A.P.; et al. Natural origin biodegradable systems in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: Present status and some moving trends. J. R. Soc. Interface 2007, 4, 999–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, W.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Wan, Y.; Wang, X.; Bi, N.; Li, C. Advancements and Frontiers in the High Performance of Natural Hydrogels for Cartilage Tissue Engineering. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Heng, B.C.; Wang, D.-A.; Ge, Z. Modified hyaluronic acid hydrogels with chemical groups that facilitate adhesion to host tissues enhance cartilage regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrintaj, P.; Manouchehri, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Saeb, M.R.; Urbanska, A.M.; Kaplan, D.L.; Mozafari, M. Agarose-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 187, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, S.; Karim, S.; Aslam, S.; Jahangeer, M.; Nelofer, R.; Nadeem, A.A.; Qamar, S.A.; Jesionowski, T.; Bilal, M. Alginate-Based Bio-Nanohybrids with Unique Properties for Biomedical Applications. Starch-Starke 2022, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudiyarasu, S.; Perumal, M.K.K.; Renuka, R.R.; Natrajan, P.M. Chitosan composite with mesenchymal stem cells: Properties, mechanism, and its application in bone regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Dan, X.; Chen, H.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Ju, Y.; Li, Y.; Lei, L.; Fan, X.; Hu, Y.; et al. Developing fibrin-based biomaterials/scaffolds in tissue engineering. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 40, 597–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, M.C.; Nawaz, H.A. Multi-Functional Macromers for Hydrogel Design in Biomedical Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 27677–27706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercea, M. Recent Advances in Poly(vinyl alcohol)-Based Hydrogels. Polymers 2024, 16, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malikmammadov, E.; Tanir, T.E.; Kiziltay, A.; Hasirci, V.; Hasirci, N. PCL and PCL-based materials in biomedical applications. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2017, 29, 863–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkaban, H.; Barani, M.; Akbarizadeh, M.R.; Chauhan, N.P.S.; Jadoun, S.; Soltani, M.D.; Zarrintaj, P. Polyacrylic Acid Nanoplatforms: Antimicrobial, Tissue Engineering, and Cancer Theranostic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckanagul, J.A.; Alcantara, K.P.; Bulatao, B.P.I.; Wong, T.W.; Rojsitthisak, P.; Rojsitthisak, P. Thermo-Responsive Polymers and Their Application as Smart Biomaterials. In: Kim J-C, Alle M, Husen A, editors. Smart Nanomaterials in Biomedical Applications [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 20]. p. 291–343. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y. Advances in nanomaterial-based targeted drug delivery systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Liang, Y.; Dong, R. Physical dynamic double-network hydrogels as dressings to facilitate tissue repair. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 3322–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Le, T.T.N.; Nguyen, A.T.; Le, H.N.T.; Pham, T.T. Biomedical materials for wound dressing: recent advances and applications. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 5509–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, Z. Tailoring the Swelling-Shrinkable Behavior of Hydrogels for Biomedical Applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2303326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Ye Q, Yu S, Akhavan B. Poly Ethylene Glycol (PEG)-Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery in Cancer Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Adv Healthcare Materials 2023, 12, 2300105. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Du, R.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Z.; Yang, X. Injectable Self-Healing Adhesive Natural Glycyrrhizic Acid Bioactive Hydrogel for Bacteria-Infected Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 17562–17576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattilo, M.; Patitucci, F.; Prete, S.; Parisi, O.I.; Puoci, F. Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels and Their Application as Drug Delivery Systems in Cancer Treatment: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, N.H.; Chien, T.B.; Cuong, D.X. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Applied in Drug Delivery: An Overview. Gels 2023, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandforoushan, P.; Alehosseini, M.; Golafshan, N.; Castilho, M.; Dolatshahi-Pirouz, A.; Hanaee, J.; Davaran, S.; Orive, G. Injectable hydrogels for cartilage and bone tissue regeneration: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).