1. Introduction

Bone fractures are a major global public health concern and pose a significant economic burden on the healthcare system, with an increasing incidence in elderly population. In the United States, it is estimated to cost

$5 billion dollars annually to treat bone defects [

1]. Common disorders that are associated with complex or compromised bone fractures are diabetes, osteoporosis, bone tumors, endocrine and hormonal-related disorders, and other degenerative bone diseases. These fractures often fail to heal properly requiring surgical intervention to facilitate bone repair. Bone grafting has seen increasing use in surgery, with currently more than two million procedures per year worldwide to facilitate bone regeneration for unrepaired bone defects [

2]. There are several factors to consider when designing an ideal bone graft: defect size, tissue viability, cost, biomechanical characteristics, and the like [

3]. The current gold standard treatment for repairing bone defects is autografts. Autografts possess osteogenic characteristics necessary to promote bone healing, growth, and remodeling [

4]. There are several limitations associated with autografts; however, the main limitations are donor-site morbidity, injury during harvesting, and remodeling issues of the implanted bone [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Alternative approaches that have shown promise in providing structural benefits for bone regeneration are bone graft substitutes. Bone substitutes consist of synthetic and/or natural biomaterials with or without incorporated biological factors. The ideal criteria to consider for engineering bone substitutes to improve clinical outcomes are selecting material that is biocompatible, biodegradable, osteoinductive, osteoconductive, cost-effective, and structurally similar to bone [

3,

4]. Injectable in-situ forming bone substitutes such as calcium sulfate (CS) and calcium phosphate cement (CPC), are attractive candidates to fill irregularly shaped bone defects [

3,

9,

10]. However, there are several drawbacks associated with these injectable materials. Calcium sulfate bone substitutes have limited ability to achieve optimal bone regeneration due to their fast degradation rates and weak internal mechanical strength limiting their application to smaller bone defects [

3,

9]. Similar to calcium sulfate, calcium phosphate cement possesses unpredictable degradation kinetics and low flexural strength after load is applied [

3,

9]. Given these concerns, injectable, in-situ forming, three-dimensional, porous hydrogel scaffolds are alternatives to these aforementioned biomaterials.

Injectable hydrogels are well suited biomaterials for tissue engineering applications due to their ability to incorporate bioactive molecules, cells, fill any irregular shape or critically sized defect, their minimally invasive and biodegradable nature, thus eliminating the need for removal [

11]. In particular, chitosan-based hydrogels are attractive injectable biomaterials given their biocompatibility, biodegradability, unique antimicrobial properties, and ability to mimic native extracellular matrix (ECM) composition [

11,

12,

13]. When exposed to an aqueous environment, CS exhibits shear thinning and self-healing properties making it easily injectable. Additionally, CS based hydrogels can be designed to exhibit fast gelation properties upon injection under physiological conditions. An FDA approved CS-based scaffold, BST-CarGel®, has shown to be effective at repairing cartilage [

14]. This bioscaffold technology is mixed with patient’s whole blood prior to implantation and injected into damaged cartilage for repair. Furthermore, CS can be used as a bioscaffold material to support attachment and proliferation of osteoblasts for bone repair [

12]. In addition, cellulose nanomaterials have shown promise as biomaterials for regenerative medicine applications owing to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and high mechanical strength [

15,

16]. They have been widely studied as reinforcing agents for polymers. There are various sources and isolation methods available to synthesize nanocellulose [

16]. However, the method and source of synthesis influences the size, dimensions and surface functionality of nanocellulose [

16]. Given the versatility in fabrication methods, the mechanical and rheological properties of these nanomaterials are highly tunable, making them an attractive material to incorporate for bone regeneration.

In this study, we investigated the use of an injectable in-situ forming chitosan-based hydrogel to support the proliferation and differentiation of pre-osteoblasts for bone regeneration. Given the poor mechanical properties of chitosan-based scaffolds [

12,

13], we have incorporated cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) as a nanomaterial to strengthen mechanical properties and provide support for load-bearing implantation areas. We investigated the effects of CNCs on the rheological properties and cytocompatibility of the injectable cell-laden hydrogels. Moreover, we investigated the effects of cell seeding density on osteogenic differentiation potential. Storage modulus, yield stress and viscosity properties of hydrogels were determined to assess the impact of CNCs and cells on the rheological properties of cell laden hydrogels. Additionally, cell viability was determined for a range of cell densities to determine optimal cell seeding density within the hydrogel system. The impact of hydrogel formulations on cell differentiation was also evaluated using an alkaline phosphatase activity assay corroborated with collagen and calcium histological staining. These results provide a strong foundation for the development of our injectable cell laden hydrogel technology and determining the required optimal cells and CNCs content that can result in optimal efficacy in vivo and effectively promote bone tissue regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Chitosan (CS) powder (85% deacetylated, 200-800 cP, 3 wt% in 0.1 M acetic acid), -glycerophosphate (BGP), hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC, MW: 90,000 Da), laboratory grade Triton X-100, ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and dexamethasone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Luer-Lock (1 mL) syringes were purchased from Becton and Dickinson (Macquarie Park, Australia). Luer-Lock connectors were purchased from Baxter (Deerfield, IL, USA). BD PrecisionGlide 18 G x 1” hypodermic needles were purchased from Becton and Dickinson (Macquarie Park, Australia). Fisherbrand™ Disposable Base Molds were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Tissue-Tek® Embedding Rings were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA, USA). Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Colorimetric Assay kit was purchased from Biovision, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). LIVE/DEAD® Viability/Cytotoxicity kit containing Calcein AM and Ethidium Homodimer-1 reagents and Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay kit and dsDNA reagents were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). MC3T3-E1 subclone 4 preosteoblast cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cell culture media was prepared using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Gibco) and 4 mM L-glutamine (referred to as complete media). Osteogenic media was prepared using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Gibco), 4 mM L-glutamine, 50 g/mL ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, and 100 nM dexamethasone.

2.2. Preparation of Injectable Hydrogels

A 3%

w/v chitosan (CS) stock solution was prepared as previously reported by stirring chitosan powder in 0.1 M acetic acid in deionized water at room temperature for 48 h [

17,

18]. The 1 M

-glycerophosphate (BGP) stock solution was prepared by dissolving BGP in deionized water. Hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) stock solution (25 mg/mL) was prepared by dissolving HEC in serum free DMEM. In brief, as previously reported, the injectable thermogelling hydrogels were prepared using a three component, two-step mixing process under aseptic conditions. The three components consisted of: 1) CS, 2) BGP, 3) HEC, cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), and with or without preosteoblast cells in DMEM. The components were homogenously mixed using a Luer-lock connector to create a pre-hydrogel mixture for injection.

2.3. Rheological Properties of Cell-Laden CNC-CS Hydrogels

Rheological characterization of cell free and cell-laden CS and CNC-CS hydrogels was carried out using a rotational rheometer, Discovery Hybrid Rheometer (DHR-3) following hydrogel preparation. All rheology measurements were made using an 8 mm Sandblasted Peltier Plate. The samples were placed onto the lower plate surface and the upper plate was lowered to 0.5 mm gap distance. All viscosity measurements were performed using a logarithmic sweep and a shear rate of 0.1 to 100 s

-1 at room temperature. To determine yield stress, a continuous oscillation with a direct strain of 0.1 – 2000% and constant frequency of 1 Hz was performed for all measurements at room temperature. The point at which the storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) intersect was determined to be the yield stress. The complex viscosity was also determined at a constant frequency of 1 Hz. Viscoelasticity measurements were performed using dynamic frequency sweep testing. Prior to analysis, hydrogels were prepared and stored in 1X PBS at 37°C for 24 hours. For all measurements, the hydrogels were exposed to a constant strain amplitude of 1% and frequency of 0.1 – 20 rad/s. Gelation times were determined at 37

C using the Peltier Plate heating system. The linear viscoelastic region of CS and CNC-CS hydrogels was previously optimized and reported [

17,

18]. All gelation measurements were performed using a dynamic time sweep at a constant strain and angular frequency: 0.05% and 20 rad/s.

2.4. In Vitro Cell Viability

To determine cell viability of MC3T3-E1 preosteoblasts, 5 106 – 2 107 cells were encapsulated in 1 mL of pre-hydrogel. Cell-laden pre-hydrogels were seeded into an 8-well Nunc-chamber slide glass slide (50 L; n=3) and placed in an incubator at 37 C/5%CO2 to allow gelation to take place. After gelation, complete media was added to all samples. Twenty-four hours following incubation, cell viability was evaluated using LIVE/DEAD® Viability/Cytotoxicity kit. The samples were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope at 10x magnification. 12 z-stacks were collected per sample.

2.5. In Vitro Osteogenic Differentiation of Cell-Laden Hydrogel Scaffolds

Hydrogels containing 5 106 MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells were prepared and seeded into 6-well plates with osteogenic media. Osteogenic media was replaced every two days for up to 21 days. On day 7, 14, and 21 hydrogel scaffolds were harvested and analyzed to determine alkaline phosphatase activity, collagen formation, and calcium deposition.

2.6. Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

In brief, 1 mL of 1% Triton X-100 solution was added to each hydrogel sample and the cells were lysed by performing 3 repeat freeze-thaw cycles. To measure intracellular ALP activity, 20 mL of cell lysate and 60 mL of ALP assay buffer was added into a 96-well plate. Subsequently, 50 mL of 5 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate was added to each well containing hydrogel samples. ALP standards were prepared and added to the 96-well plate according to manufacturer protocol (Alkaline Phosphatase Activity Colorimetric Assay kit; BioVision). The samples were incubated in the dark at 25°C for 60 minutes to allow reaction to take place. ALP activity was determined by measuring optical density at 405 nm using a Biotek Synergy 2 microplate reader.

2.7. Histological Staining and Imaging

Cell-laden hydrogels were prepared and seeded into 6-well plates containing osteogenic media as previously described. On day 7, 14, and 21 hydrogel samples were placed in an equal volume of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixative and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Following incubation, samples were gently dehydrated by immersing the samples in a graded series of sucrose solutions ranging from 10-30% sucrose in 1X PBS. Hydrogel samples were subsequently embedded in cryomolds using optimal cutting temperature (OCT) embedding media and simultaneously frozen using dry ice. The hydrogel blocks were then fixed onto the cryostat base for sectioning. The samples were subsequently cut into cryosections with a thickness of 10 μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to determine ECM composition and with von Kossa to detect the presence of calcium deposits. All hydrogel sections were imaged using a Nikon Ti2 Eclipse Color and Widefield Microscope at 20x magnification.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one- and two-way Tukey’s multiple comparisons test with GraphPad Prism Software v9.3.1.

3. Results

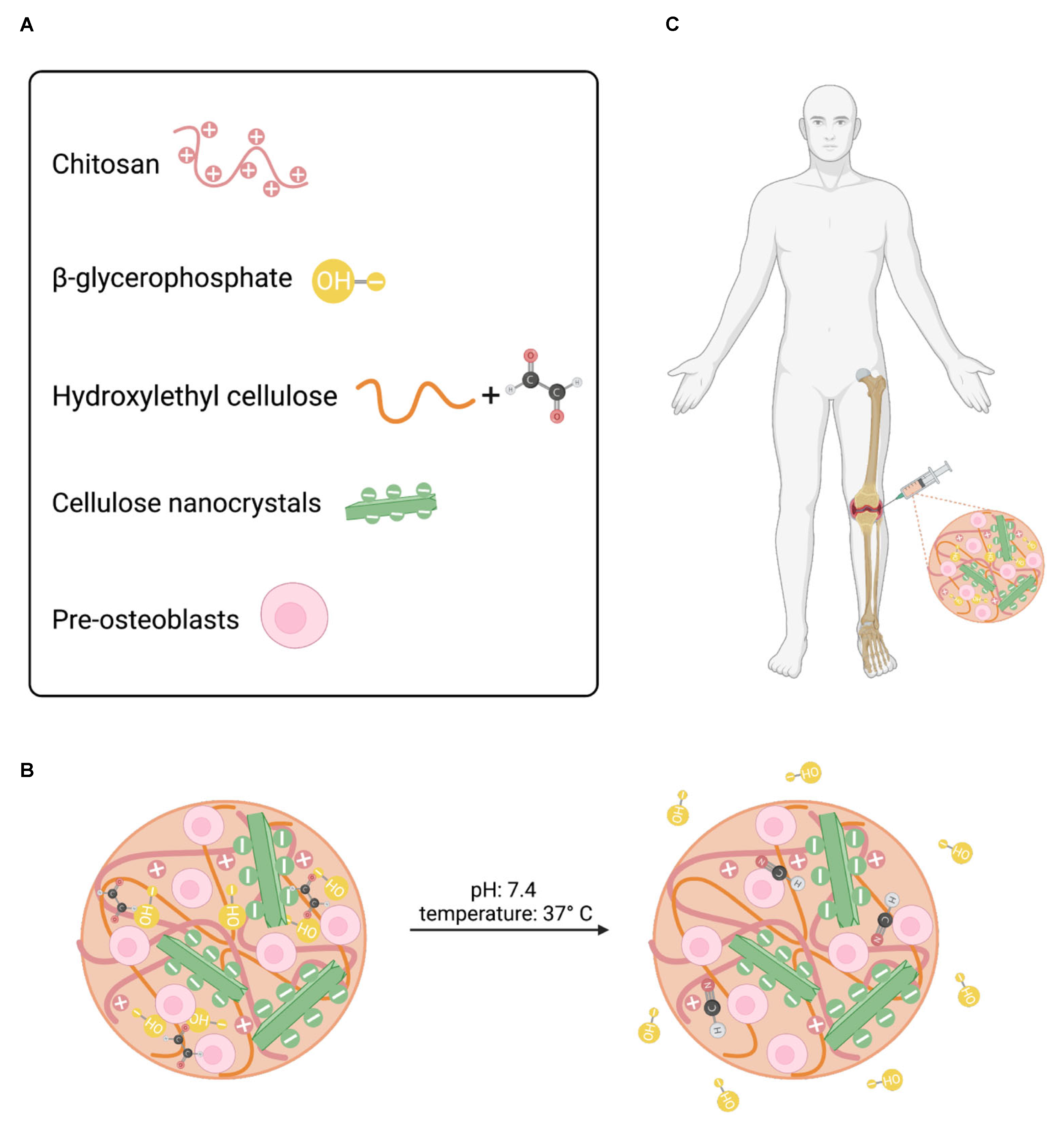

3.1. Injectable CNC-hybridized CS Hydrogels

The CNC-hybridized chitosan based injectable hydrogels were prepared as previously reported [

17]. The concentration of each component in the hydrogel formulation has been previously optimized and reported in the literature (

Figure 1A). The optimized hydrogel formulations used in this study are shown in

Table 1. In brief, the concentration of the primary and secondary gelling agent, BGP and HEC, were optimized to maintain cell survival at different seeding densities and promote faster gelation kinetics, respectively [

17]. At room temperature, non-covalent crosslinking, via ionic interactions and hydrogen bonding, is the predominate interaction within the polymer-polymer backbone owing to its liquid-like state. Under physiological conditions, pH 7.4 and 37°C, primary non-covalent interactions in addition to secondary chemical crosslinking via a Schiff base reaction between the glyoxal molecules in HEC and the amine groups in the CS network predominate thus promoting fast gelation (

Figure 1B). As a result, these hydrogels can be injected intraosseously to form an in-situ gel at the critical defect site (

Figure 1C).

3.2. Rheological Properties of Injectable CNC-Hybridized CS Hydrogels

Previous work has demonstrated that the incorporation of CNCs at 1.5% was able to enhance the hydrogel’s mechanical properties and promote osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 in 3D bioprinted hydrogel scaffolds (referred to as bioinks) [

19]. Therefore, in this study, we set out to evaluate cell viability of MC3T3-E1 cells at varying cell seeding densities, rheological effects of incorporating MC3T3-E1 cells, and the osteogenic differentiation potential of the injectable hydrogels with and without 1.5% CNCs. Initial screening process of CS and CNC-CS hydrogels was performed with varying MC3T3-E1 cell loading densities ranging from 5 to 20 million. Results demonstrated that higher cell loading densities

10 million cells per mL hydrogel were viable following encapsulation as shown in

Supplementary Figure 1. However, these cell concentrations were not uniformly distributed throughout the pre-hydrogel mixture resulting in a non-homogenous cell-laden hydrogel formulation (

Supplementary Figure 2). Given these results, cell concentrations

10 million cells per mL hydrogel were not further characterized in this study.

Rheological measurements were evaluated on all optimized cell-laden CS and CNC-CS hydrogel scaffolds to determine viscosity, yield stress, and gelation kinetics. These properties are significant parameters that influence the hydrogels’ injectability, ability to maintain shape fidelity, and retain encapsulated cells at the defect site upon injection. Ideally, hydrogels that exhibit 1) high viscosity to maintain shape and prevent hydrogel escape at site of injection, 2) shear-thinning behavior during injection, and 3) fast gelation kinetics to retain cells and prevent loss of hydrogel following injection [

20].

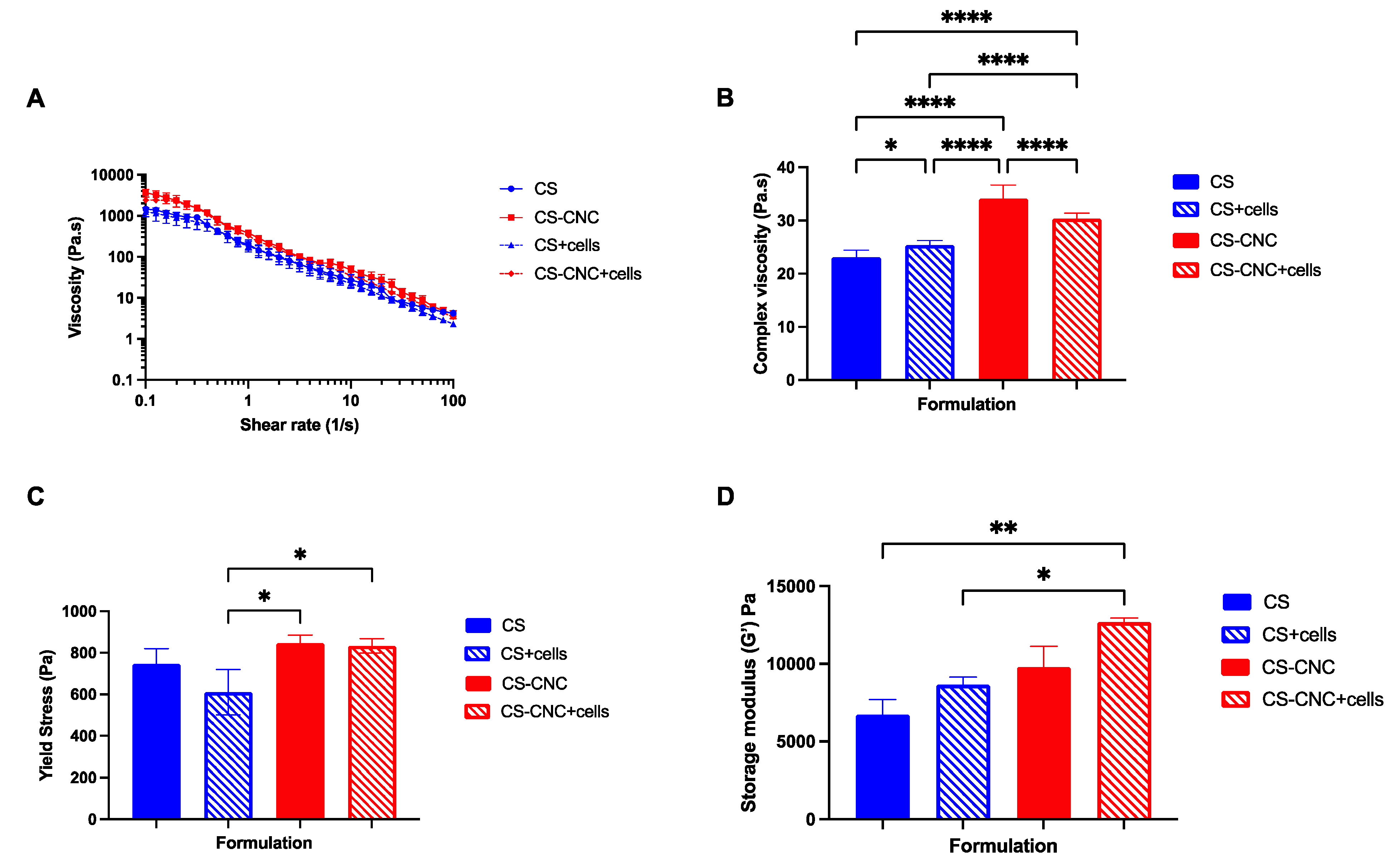

The viscosity of CS and CNC-CS hydrogels were investigated to determine the effect of incorporating MC3T3-E1 cells on hydrogel flow behavior. The viscosity measurements were determined by using a flow sweep analysis (

Figure 2A). Results demonstrated that all hydrogel formulations exhibited shear-thinning properties as the shear rate increased, demonstrating their injectability. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference in viscosity between cell free and cell-laden injectable hydrogels. However, at a frequency of 1 Hz, results demonstrated that there was statistically significant difference between cell free CS and CNC-CS hydrogels (23.12

1.285

vs. 34.11

2.560;

p < 0.0001), cell free CS and cell-laden CS hydrogels (23.12

1.285

vs. 25.34

0.9209;

p < 0.05), cell-laden CS and CNC-CS hydrogels (25.34

0.9209

vs. 30.35

1.038;

p < 0.0001), respectively (

Figure 2B). The differences observed in cell free and cell-laden CNC-CS hydrogels can be attributed to cells occupying void space within the polymer matrix thus causing less interactions between the polymer backbone which ultimately may result in a decrease in the complex viscosity.

Yield stress of injectable hydrogel formulations was measured to further characterize the ability of hydrogels to maintain their shape fidelity upon injection. Yield stress can be defined as the point at which the hydrogel begins to flow under applied stress. There were no statistically significant differences observed in both cell free hydrogel scaffolds, i.e. with and without CNCs (

p = 0.50). Conversely, results showed that in the presence of cells, CNC-CS hydrogels exhibited a significant increase in yield stress in comparison to CS hydrogels (610.5

109.0

vs. 833.5

34.70;

p < 0.05). More importantly, incorporating cells into either hydrogel formulations (with and without CNCs) did not significantly change the hydrogels’ yield stress (

Figure 2C).

The storage modulus was evaluated to determine the elastic behavior or stiffness of the hydrogel scaffolds. Results from the mechanical testing, shown in

Figure 2D, demonstrate that the addition of CNCs and cells increases the mechanical properties of CS hydrogels. Moreover, cell-laden CNC-CS hydrogels exhibited significantly higher modulus in comparison to cell free (6713 ± 993.6

vs.12698 ± 247.13;

p < 0.005) and cell laden CS hydrogels (8650 ± 494.9

vs.12698 ± 247.13;

p < 0.05). These results indicate that the CNC-CS hydrogel formulation can achieve desirable mechanical stiffness to mechanically induce osteogenic differentiation of preosteoblast [

21].

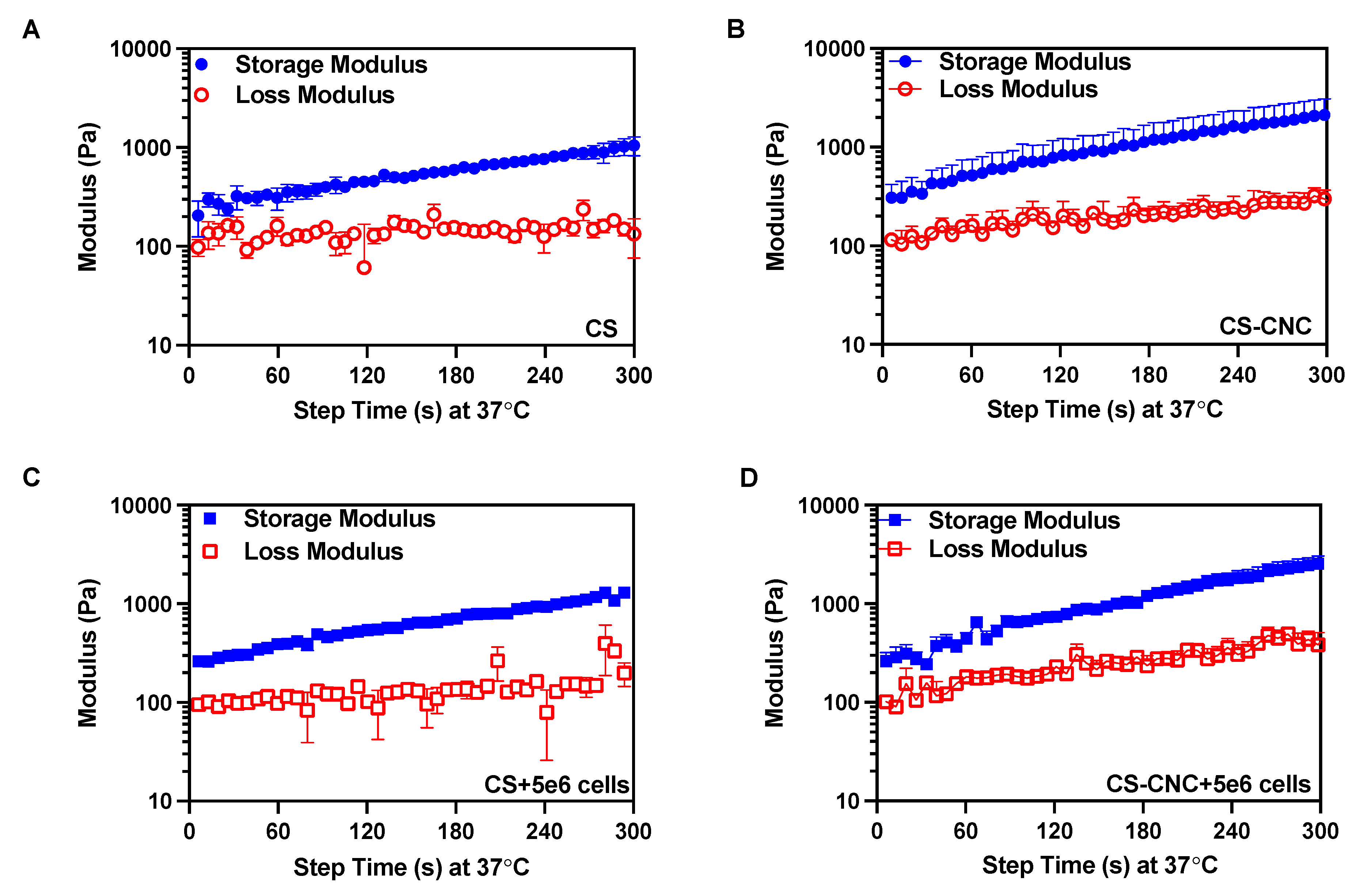

As previously discussed, it is important to not only maintain shape fidelity of the hydrogels upon injection but, also retain the encapsulated cells at defect site. To characterize the gelation time of cell free and cell-laden hydrogel formulations, gelation kinetics were analyzed. Given the thermogelling behavior of the injectable hydrogels, the gelation kinetics were determined by performing a dynamic time sweep under constant temperature, strain, and angular frequency. Gelation is defined as the crossover point between the storage (G’) and loss modulus (G”). Results from the gelation analysis showed that all hydrogel formulations gelled in less than 7 seconds and hydrogels continued to stiffen 5 minutes following injection (

Figure 3). These results demonstrate that the presence of cells did not have an effect on CS and CNC-CS thermogelling properties. Furthermore, the gelling behavior of cell free and cell-laden hydrogels suggest instantaneous gelation upon injection under physiological conditions. A detailed report of all rheological analysis is summarized in

Table 2.

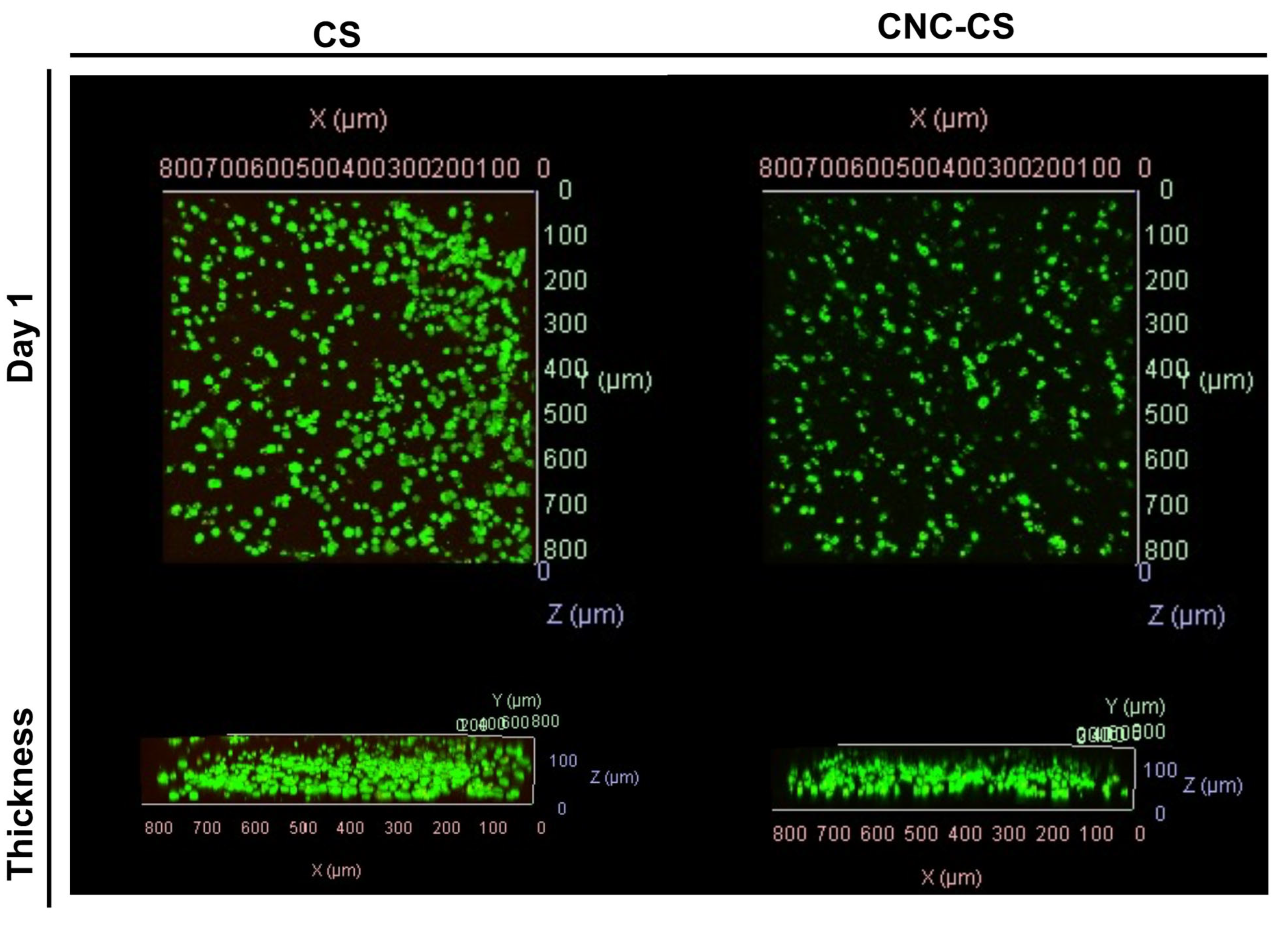

3.3. In Vitro Cell Viability of MC3T3-E1 Cells

Cell viability was assessed to determine cytocompatibility of injectable hydrogels. MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast cells were encapsulated in CS and CNC-CS hydrogels at a cell loading density of 5 million cells per 1 mL of hydrogel. In previous studies, we have demonstrated the ability to encapsulate neural stem cells in the injectable hydrogels for treatment of glioblastoma and MC3T3-E1 cells in bioink formulations for tissue engineering applications [

18,

19]. Herein, we report the semi-quantitative analysis of MC3T3-E1 cell viability in the injectable CS and CNC-CS hydrogels using confocal microscopy. Live image analysis was used to detect viable vs non-viable cells within the hydrogel scaffold following twenty-four hours of encapsulation. As illustrated in

Figure 4, MC3T3-E1 cells showed similar cell viability in both hydrogel scaffolds. These results indicate that the components within the injectable hydrogel do not significantly impact cell viability, thus suggesting these hydrogels are cytocompatible and suitable biomaterials.

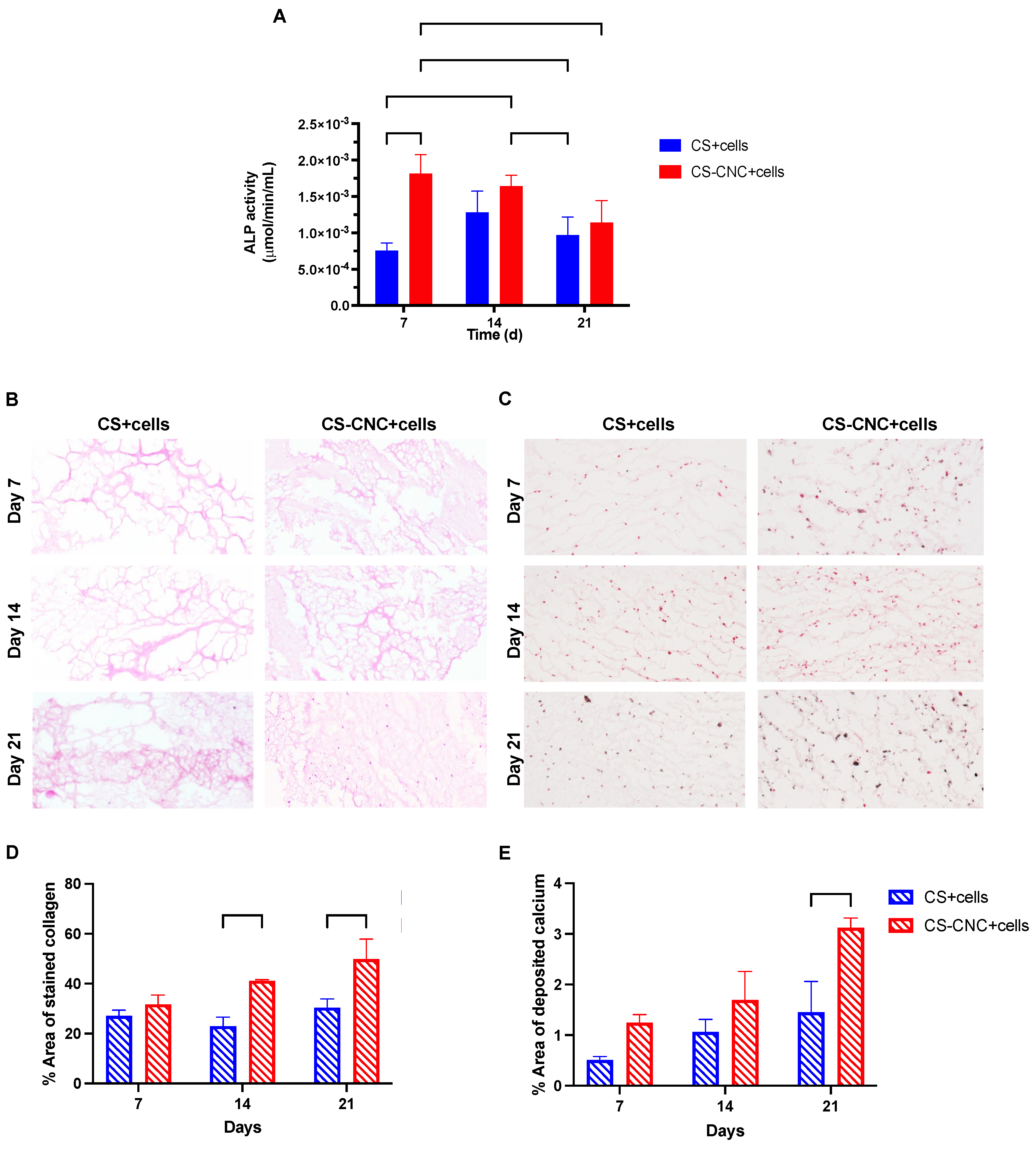

3.4. In Vitro Osteogenic Differentiation of MC3T3-E1 Cells in Injectable Hydrogels

In normal conditions, bone tissue formation occurs in three stages: 1) cell proliferation, 2) matrix synthesis and maturation and 3) matrix mineralization [

22,

23]. Pre-osteoblasts are key regulators in matrix maturation and mineralization by expression of early markers such as alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin, which are necessary for collagen production [

22,

23]. To evaluate the osteogenic differentiation potential of MC3T3-E1 cells in the CS and CNC-CS hydrogels, in vitro osteogenesis assays were performed. Preosteoblasts were encapsulated in the hydrogels, cultured in osteogenic media, and ALP activity, collagen formation, and calcium deposition were investigated over 21 days. As shown in

Figure 5A, within the first 7 days of culturing, ALP activity was significantly increased in MC3T3-E1 cells in CNC-CS hydrogels in comparison to CS hydrogels (0.002 ± 0.0003

vs. 0.0008 ± 0.0001;

p < 0.005) showing a faster onset of ALP activity in the presence of CNCs. At day 14, the ALP activity remained unchanged in the cell-laden CS-CNC hydrogels. In addition, at day 14 the ALP activity increased in the cell-laden CS hydrogels to reach similar activity observed in the CS-CNC hydrogels. Graphical representation of ALP activity for cell concentrations > 10 million cells per mL hydrogel is illustrated in

Supplementary Figure 3. Given the challenges with preparing these formulations as shown in

Supplementary Figure 2, there was no correlation or additive effect between increasing the cell density and ALP activity. Altogether, these findings suggest that the incorporation of CNC nanomaterials significantly upregulates the expression of early osteogenesis marker ALP. The differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells were further assessed by examining the collagen formation and calcium deposition in hydrogel scaffolds, as shown in

Figure 5B-C. The percent area of stained collagen and deposited calcium were analyzed, and results are shown in

Figure 5D-E. Similarly, the formation of collagen (41.1 ± 0.511

vs. 22.9 ± 3.61 and 49.9 ± 7.93

vs. 30.4 ± 3.48;

p < 0.05) and the deposition of calcium (3.12 ± 0.194

vs. 1.46 ± 0.603) in hydrogel scaffolds were significantly increased at day 14 and 21 in CNC-CS compared to CS-only hydrogels. Collectively, these results demonstrate that both hydrogel scaffolds can promote osteogenic differentiation of preosteoblast. However, the addition of CNCs to CS hydrogels induces the early expression of markers for osteogenesis and further promotes cell survival, differentiation, matrix maturation and mineralization to support bone formation.

4. Discussion

Although autografts are effective in bone reconstruction, they are associated with severe complications that lead to graft failure and improper bone healing. Research efforts have focused on the development of innovative injectable biomaterials that closely mimic the extracellular matrix and architecture of bone tissue. Factors including polymer type, concentration, and crosslinking behavior and/or mechanisms can influence a biomaterial’s ability to induce bone formation [

21]. Hydrogels possess the ability to provide mechanical and physical support to promote cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation for bone healing. Due to their three-dimensional network, hydrogels provide an environment for encapsulation of cells and bioactive molecules and are excellent structures for integration into bone tissue. Given these advantages, we investigated a novel injectable, in-situ CNC-CS-based hydrogel system to evaluate its potential as a scaffold to promote osteogenesis and differentiation of preosteoblasts in vitro.

The biodegradability and mechanical integrity of hydrogel scaffolds are two key properties that determine their ability to promote proper bone healing and optimal efficacy in vivo. In this study, CNCs were incorporated as a nanomaterial to improve rheological and mechanical properties. All hydrogel formulations investigated in this study exhibited shear-thinning properties with similar viscosity measurements under increasing shear rates. Moreover, complex viscosity measurements were comparable and within standard range (25 – 4540 Pa

s) [

24] for both cell free and cell-laden CS and CNC hydrogels indicating their potential ability to resist shear forces within the tissue post injection. The addition of CNCs to CS hydrogels had a significant impact on yield stress and storage modulus. CNC-CS hydrogels exhibited greater yield stress and storage modulus than CS hydrogels alone. Moreover, the significantly higher modulus of CNC-CS hydrogels demonstrates their potential ability to mimic the extracellular matrix of bone

in vivo. Additionally, in cell laden hydrogels the yield stress and storage modulus increased concomitantly in the presence of CNCs, which could lead to better shape fidelity and mechanical integrity when injected in vivo.

It is well known that osteogenic differentiation of cells within biomaterials is a requisite for effective bone tissue formation. Following a bone fracture, bone growth and development usually occurs over 3 to 12 weeks [

1]. Hence, ALP activity and ECM components were analyzed to determine the ability of CS and CNC-CS hydrogels to promote bone formation. The histological analysis showed that the cell-laden hydrogels promoted collagen formation and calcium deposition for up to 21 days thereby supporting bone maturation and mineralization of the ECM. Similar to our previous observations with bioink formulations [

19], results showed that incorporation of CNCs within the hydrogel formulation promoted enhanced osteogenesis, which could potentially enhance efficacy for bone healing. It is worth noting that a longer culture period greater than 3 weeks could provide more detailed observation on the ability of CS and CNC-CS hydrogels to induce osteogenic differentiation of preosteoblasts and support bone maturation and mineralization.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides insights into a novel cellulose nanocrystal hybridized chitosan-based injectable hydrogel platform suitable for cell encapsulation to enable the osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts precursor cells to osteocyte-like cells. Our results demonstrate that the incorporation of CNC nanomaterial improved the rheological and mechanical properties of our CS-based injectable hydrogel system, making it an attractive cell delivery system for tissue engineering applications. In vitro histological analysis demonstrated the significant upregulation of osteocyte-like activity within 7 days. Furthermore, CNC-CS hydrogels maintained the ability to induce bone maturation and mineralization over 21 days. Further in vivo studies are needed to determine the efficacy of CNC-CS in a clinically relevant rodent model.

6. Patents

SRB and PM are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the University of North Carolina, Office of Technology Commercialization (UNC OTC) (PCT International Application PCT/US2019/034492). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: In vitro cell viability of MC3T3-E1 CS and CNC-CS hydrogels; Figure S2: Non-uniform distribution of MC3T3-E1 cells within CNC-CS hydrogels at high cell seeding densities; Figure S3: ALP activity of cell-laden CS and CS-CNC hydrogels over 21-day study period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L.K., P.M., S.R.B.; methodology, J.L.K., P.M., S.R.B.; software, N/A; validation, J.L.K., S.R.B.; formal analysis, J.L.K.; investigation, J.L.K.; resources, S.R.B.; data curation, J.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.K.; writing—review and editing, J.L.K., S.R.B.; visualization, J.L.K.; supervision, S.R.B.; project administration, J.L.K., S.R.B.; funding acquisition, J.L.K., S.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (grant award number 550KR252002 to SRB). This work was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award number T32GM086330 to JLK).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are within the article and Supplementary Material, or on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NC Translational and Clinical Sciences (NC TraCS) Institute, which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (grant award number 550KR252002 to SRB). This work was also supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award number T32GM086330 to JLK).

Conflicts of Interest

SRB and PM are inventors on a patent application related to this work filed by the University of North Carolina, Office of Technology Commercialization (UNC OTC) (PCT International Application PCT/US2019/034492).

References

- Perez, J. R.; Kouroupis, D.; Li, D. J.; Best, T. M.; Kaplan, L.; Correa, D. Tissue Engineering and Cell-Based Therapies for Fractures and Bone Defects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, V.; Milano, G.; Pagano, E.; Barba, M.; Cicione, C.; Salonna, G.; Lattanzi, W.; Logroscino, G. Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: from basic science to clinical practice. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2014, 25, 2445–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Yeung, K. W. K. Bone grafts and biomaterials substitutes for bone defect repair: A review. Bioact. Mater. 2017, 2, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oryan, A.; Alidadi, S.; Moshiri, A.; Maffulli, N. Bone regenerative medicine: classic options, novel strategies, and future directions. J Orthop Surg Res 2014, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, T. W.; Muschler, G. F. Bone graft materials. An overview of the basic science. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2000, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Long, W. G.; Einhorn, T. A.; Koval, K.; McKee, M.; Smith, W.; Sanders, R.; Watson, T. Bone grafts and bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic trauma surgery. A critical analysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 649–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkenke, E.; Neukam, F. W. Autogenous bone harvesting and grafting in advanced jaw resorption: morbidity, resorption and implant survival. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2014, 7 Suppl 2, S203–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, A. T.; Jensen, S. S.; Worsaae, N. Complications related to bone augmentation procedures of localized defects in the alveolar ridge. A retrospective clinical study. Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016, 20, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.; Hannink, G. Injectable bone-graft substitutes: current products, their characteristics and indications, and new developments. Injury 2011, 42 Suppl 2, S30–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J. T.; Sandler, A. L.; Tepper, O. A review of reconstructive materials for use in craniofacial surgery bone fixation materials, bone substitutes, and distractors. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2012, 28, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olov, N.; Bagheri-Khoulenjani, S.; Mirzadeh, H. Injectable hydrogels for bone and cartilage tissue engineering: a review. Prog. Biomater. 2022, 11, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levengood, S. L.; Zhang, M. Chitosan-based scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B, Mater. Biol. Med. 2014, 2, 3161–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, A. Chitosan-Based Biomaterials for Bone Tissue Engineering Applications: A Short Review. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shive, M. S.; Stanish, W. D.; McCormack, R.; Forriol, F.; Mohtadi, N.; Pelet, S.; Desnoyers, J.; Méthot, S.; Vehik, K.; Restrepo, A. BST-CarGel® Treatment Maintains Cartilage Repair Superiority over Microfracture at 5 Years in a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Cartilage 2015, 6, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, M.; Si, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, B. Cellulose nanocrystals and cellulose nanofibrils based hydrogels for biomedical applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 209, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.; Sabapathi, S. N. Cellulose nanocrystals: synthesis, functional properties, and applications. Nanotechnol. Sci. Appl. 2015, 8, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maturavongsadit, P.; Paravyan, G.; Shrivastava, R.; Benhabbour, S. R. Thermo-/pH-responsive chitosan-cellulose nanocrystals based hydrogel with tunable mechanical properties for tissue regeneration applications. Materialia 2020, 12, 100681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J. L.; Maturavongsadit, P.; Hingtgen, S. D.; Benhabbour, S. R. Injectable pH Thermo-Responsive Hydrogel Scaffold for Tumoricidal Neural Stem Cell Therapy for Glioblastoma Multiforme. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturavongsadit, P.; Narayanan, L. K.; Chansoria, P.; Shirwaiker, R.; Benhabbour, S. R. Cell-Laden Nanocellulose/Chitosan-Based Bioinks for 3D Bioprinting and Enhanced Osteogenic Cell Differentiation. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 2342–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stojkov, G.; Niyazov, Z.; Picchioni, F.; Bose, R. K. Relationship between Structure and Rheology of Hydrogels for Various Applications. Gels 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Gao, M.; Syed, S.; Zhuang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.-Q. Bioactive hydrogels for bone regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2018, 3, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infante, A.; Rodríguez, C. I. Osteogenesis and aging: lessons from mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2018, 9, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekara, D. S.; Kim, S.; Rho, J. Regulation of osteoblast differentiation by cytokine networks. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vildanova, R. R.; Sigaeva, N. N.; Kukovinets, O. S.; Kolesov, S. V. Preparation and rheological properties of hydrogels based on N-succinyl chitosan and hyaluronic acid dialdehyde. Polym. Test. 2021, 96, 107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).