Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Geospatial analysis has become essential in modern business analytics and decision-making processes. The unique nature of spatial data, being bidirectional and 360-degree oriented (unlike linear time series data), requires specific referencing systems using latitude-longitude coordinates and appropriate projections. Data can be represented in two main formats: raster (grid cells) and vector (points, lines, and polygons). Various digital map formats exist, both proprietary (like ESRI's Shapefile and MapInfo's TAB files) and open source (including GeoJSON, GeoPackage, and KML), each with different organizational structures and capabilities. These formats support the growing integration of geospatial analysis across sectors such as urban planning, site selection, and competitive intelligence. Platforms like ArcGIS, QGIS, and GeoDa have democratized access to geospatial analytics through user-friendly interfaces and visualization tools. These technologies enable professionals across industries to leverage spatial data effectively, enhancing operational efficiency and strategic planning through location-specific analysis and pattern recognition.

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION TO GEOSPATIAL ANALYSIS

- A)

- In the private sector: Market researchers and independent consultants, retailers, telecommunication and network companies, transport and logistic companies, investment banks and private equity firms, insurance companies, and property appraisers.

- B)

- In the public sector and government: Academic research, national banks (e.g. Bank of Spain), urban and regional planners, real estate developers, state security forces and criminologists.

- Mapping. A good example of geospatial data use is visualizing the area that the data describes, like transportation routes, building sites, administrative areas, etc. A precisely drawn map can be an immensely powerful tool. This is the case of travelers who may not know their way around a particular area and need to use Google Maps or Waze, among others.

- Site selection There are some things to consider when selecting or deselecting retail sites: Where locations are currently located? Are other nearby stores in competence (market competition), or possibly collaboration (market agglomeration)? How close is a shop to where the target customers live? How accessible are the company sites to those target customers? Where are the successful stores whose qualities should be mimic?

- Visit attribution. Another use case is telling the difference between someone entering your store or just simply passing by. You can compare accurate building area data with precise GPS from mobile devices to know how many people entered your store.

- Urban planning. If you are working in the government or the public sector, you can make sound planning decisions based on data about building location, people living areas, commuting flows, traffic data, etc. For instance, you can plan construction for roads or other transportation systems to reduce walk/drive times work and/or education facilities. Or, on the contrary you can plan to build hospitals or schools in areas with good access.

- Network planning. For example, foot traffic data can help providers, like Movistar, Orange, etc. They can implement a sufficient coverage with the least amount of hardware. They also can fix the price they charge for WIFI hotspots, with installations in higher-traffic areas being more expensive. For other businesses, like retailers, they can decide on the telecom plan and infrastructure they need.

- Investment research. Investment banks and private equity firms can model and predict consumer behavior and movement patterns using variables like location data for stores, and other points of interest, traffic data, and contextual data (like per capita income, population by age, etc.). This will allow them to get a better picture of how the businesses they are investing in are actually performing or the ones they are planning on investing in.

- Competitive intelligence. Competition affects in part a business performance. For instance: A map can reveal customers’ choice among different competitors depending on parking space and transportation routes. It is also possible to discover if a business stores are too close together in terms of walk/drive time, and if they are competing over the same customers (they are being phagocytized). Or it can also be noticed if nearby stores that are assumed to compete each other, actually are not, because the target customers may be coming from different locations.

- Risk assessment. The insurance industry is another sector that is making use of geospatial analysis. For instance, to assess building vulnerability to things like destructive weather, foods, fire, vehicle accident, etc., insurers need to know a number of their geospatial attributes like where a building is, how much space it takes up, how close it is to surrounding buildings, how many businesses are contained in the same building, what they do or sell, since some businesses present more hazards than others. Regarding occupancy, the more people living in or visiting a building daily, the greater the risk for an accident to happen.

- Trade area analysis: Sometimes it is not enough to just look at how accessible a location is and how close competitors are. It must be known, for example: if potential customers’ lifestyles make them want to buy what you are selling, if they would afford the products a business is selling, based on their average income range, if there are many competitors nearby and how well-established they are, if the competitors have a good reputation, to consider another area where compete with easiest rival businesses, etc. Asking these types of questions helps you more accurately adjust your site selection (among other things) to satisfy the people who will most likely be your clients.

- Consumer insights. A specific geospatial data sample may be able to give you even more granular insights into your customers’ shopping habits. For instance, looking at establishments that consumers visit before or after they come a specific shop. This could be the case of a health-conscious shop or restaurant noticing that a lot of customers are going to gyms or yoga studios before or after they go to their shop or restaurant. Hence, this knowledge could be used to identify nearby stores of this type on a map and approach them for cross-promotion opportunities.

2. WHY IS SPATIAL DATA SPECIAL?

2.1. SPATIAL DIMENSIONS

- -

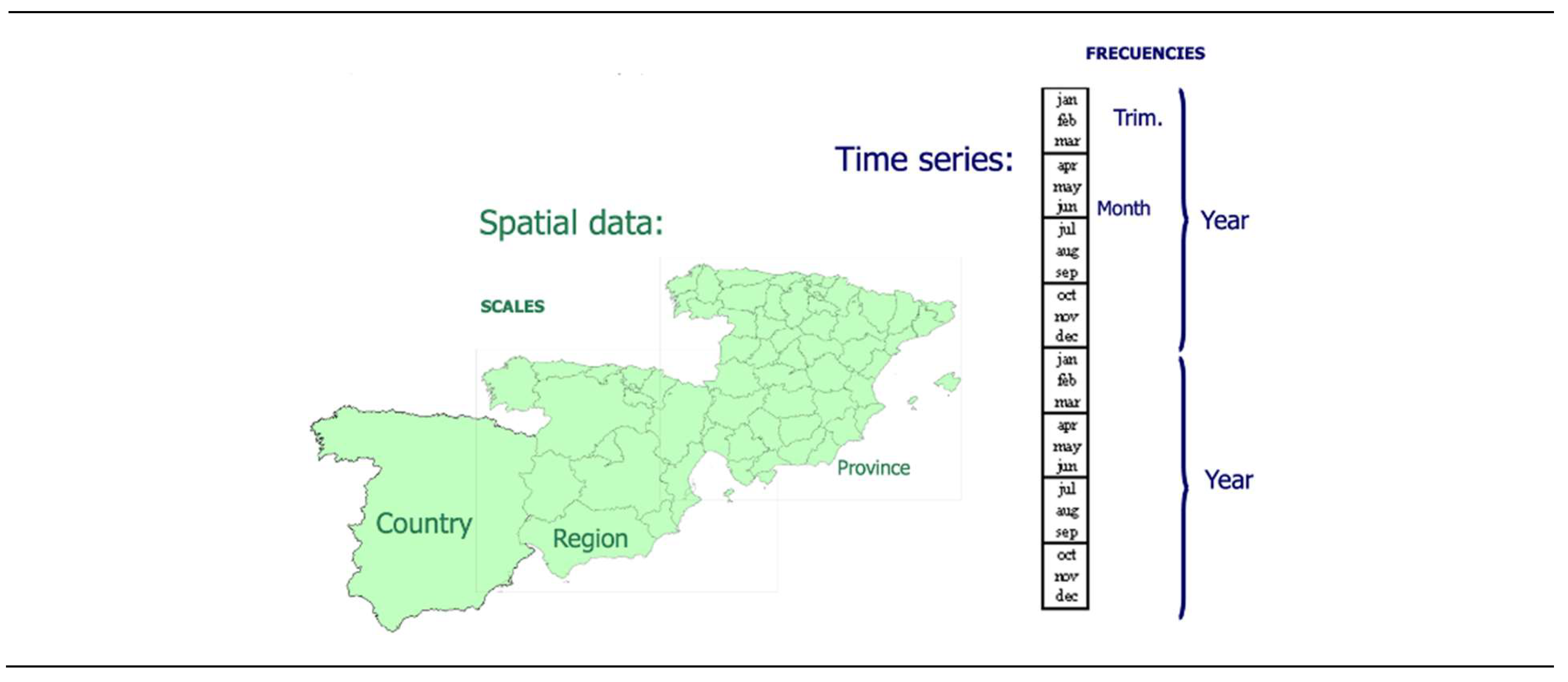

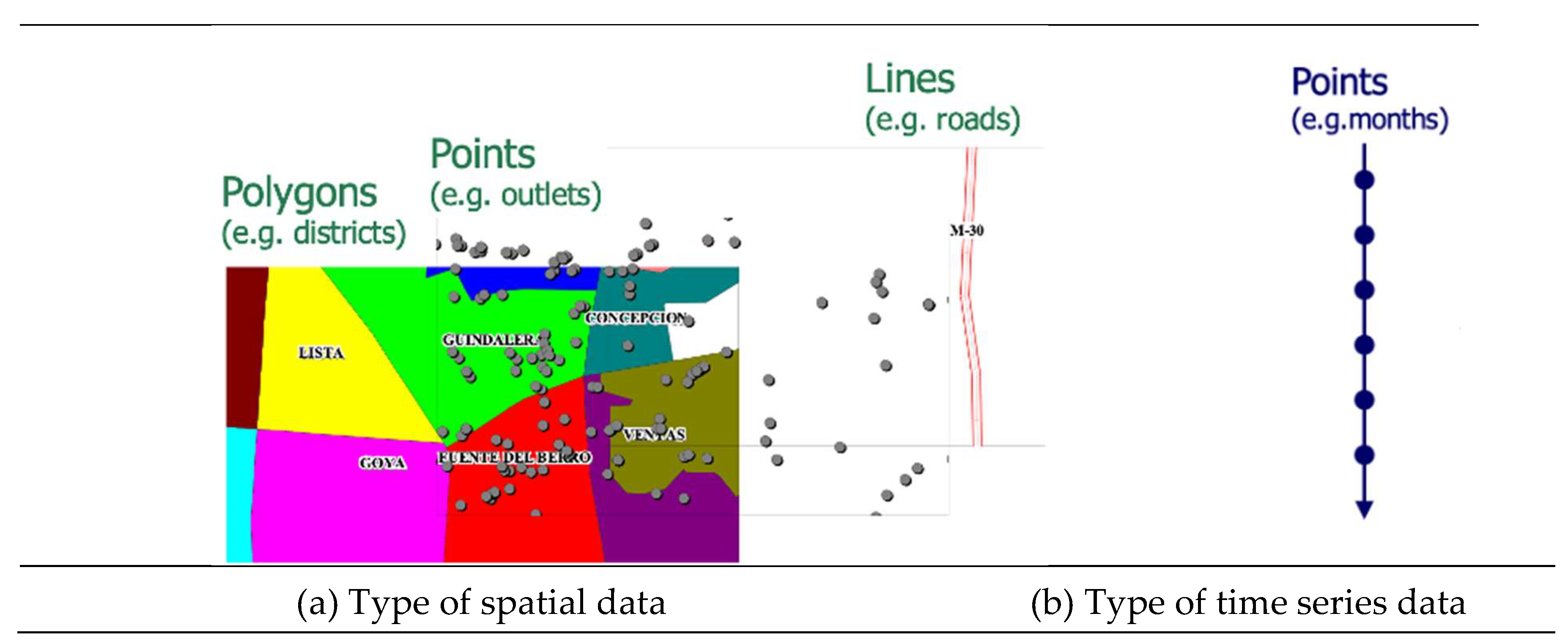

- Space can be represented as a continuous, two-dimensional surface, while time is represented as a continuous, one-dimensional line.

- -

- In geographic space, any point “i” is interconnected with the other points in a 360-degree circular space., usually simplified by the 4 cardinal points (north, south, east and west) and intercardinal points (NE, SE, NW, SW). In time, a moment “t” is related linearly in 2 directions: to the past (“t – 1”) and to the future (“t + 1”).

- -

- In geographic space, any point “i” is interconnected with the other points in a 360-degree circular space., usually simplified by the 4 cardinal points (north, south, east and west) and intercardinal points (NE, SE, NW, SW). In time, a moment “t” is related linearly in 2 directions: to the past (“t – 1”) and to the future (“t + 1”).

2.2. SPATIAL SCALES

- 1)

- Member countries.

- 2)

- NUTS 1: major socio-economic regions.

- 3)

- NUTS 2: basic regions, which are eligible for the EU regional policies.

- 4)

- NUTS 3: small regions.

- 5)

- LAU: municipalities or communes.

- -

- The NUTS are the reference countries’ regions, which have been developed for statistical purposes and, in the case of the NUTS 2, to frame EU regional policies. Based on existing national administrative subdivisions, they have been established following criteria based on population segments (with some exceptions).

- -

- The LAUs are a subdivision of the NUTS 3 regions covering the EU's whole economic territory. They are appropriate for implementing local level typologies like the one that classifies LAUs as cities (densely populated areas, towns and suburbs (intermediate density areas) and rural areas (thinly populated areas).

- 1)

- 7 NUTS 1: Noroeste, Noreste, Comunidad de Madrid, Centro, Este, Sur, and Canarias (their official name is in Spanish).

- 2)

- 19 NUTS 2: the 17 autonomous communities and 2 autonomous cities (Ciudad de Ceuta and Ciudad de Melilla).

- 3)

- 59 NUTS 3: the 50 provinces, 3 Balearic Islands (Mallorca, Menorca, and Eivissa and Formentera), 7 Canary Islands (Gran Canaria, Tenerife, Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, La Palma, La Gomera and El Hierro), plus Ceuta and Melilla.

- 4)

- 8,131 LAU: the municipalities.

- a)

- Postal code areas: territorial divisions that are important to companies because it is a piece of information that customers tend to provide in surveys and loyalty cards without much suspicion. However, these divisions do not coincide with the administrative divisions of NUTS and LAUs, for which the statistical institutes produce most of their databases. Eurostat has therefore developed the TERCET NUTS-postal codes matching tables containing a lookup-list of European postal codes and their corresponding NUTS codes.

- b)

- Square grids of small resolution (1x1 and 10x10 km). In this case, administrative divisions (such as countries) are not respected. For example, there are 1x1 grids that include territory of Irun (Spain) and territory of Hendaye (France). In this case, there are areas that are not gridded because there is no population in them (such as large areas of the Pyrenees).

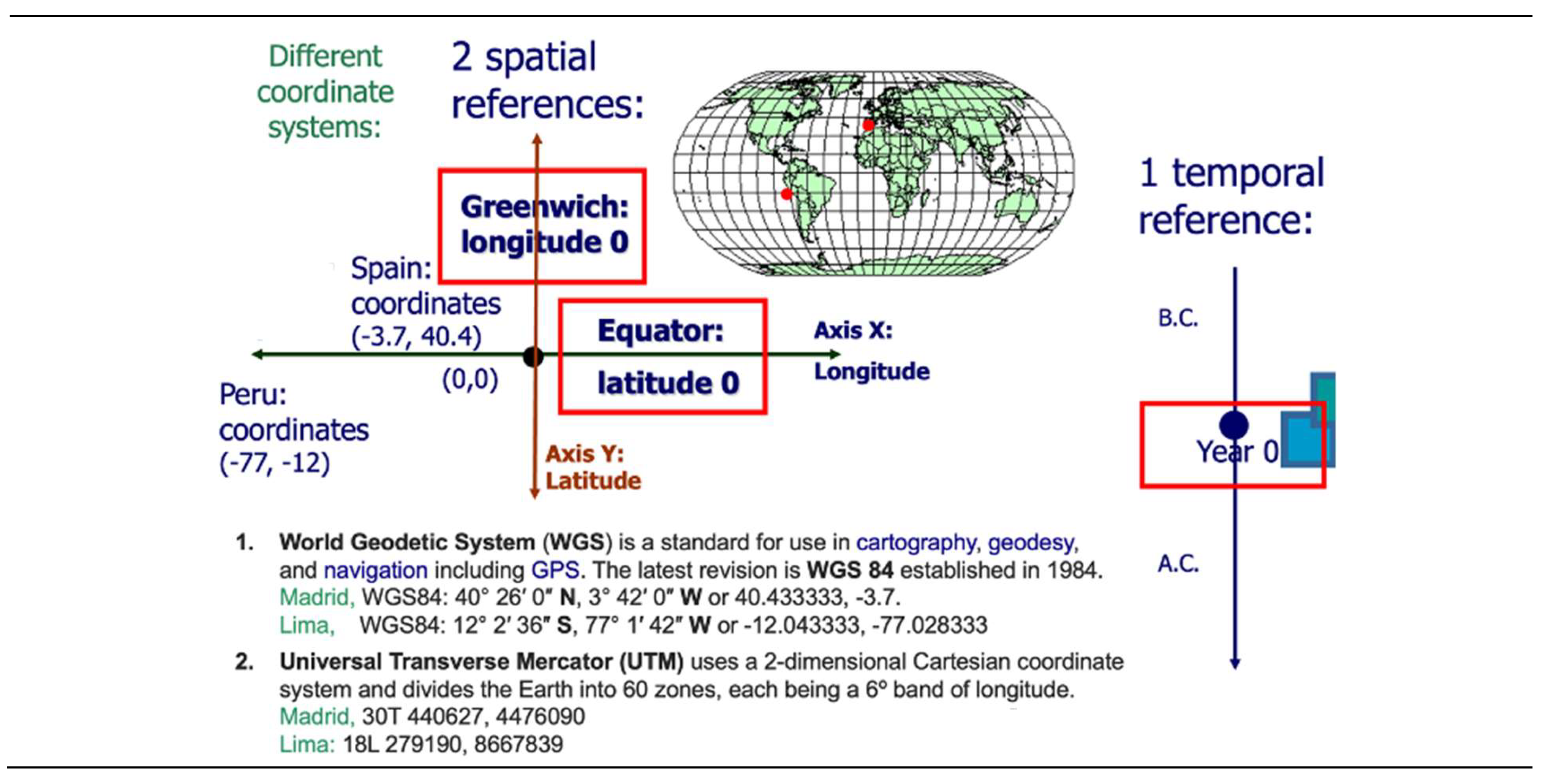

2.3. SPATIAL REFERENCES

2.3.1. Transformation from a spherical shape to a flat map

- 1)

- Selecting a so-called geodetic datum model. The most commonly used datum is the World Geodetic System of 1984, WGS 84, which represents the Earth as an ellipsoid (and not as a perfect sphere). In Europe, an alternative is the European Terrestrial Reference System 1989, ETRS89.

- 2)

- Converting the latitude-longitude coordinates to cartesian X-Y coordinates in a planar system, using a cartographic projection. Hundreds of projections have been developed, as mathematical methods of converting a 3-dimensional quasi-sphere to a 2-dimensional flat map. The use of an inappropriate projection may yield to misleading distance computations among locations, especially for analyses that cover large areas (e.g., continent-wide).

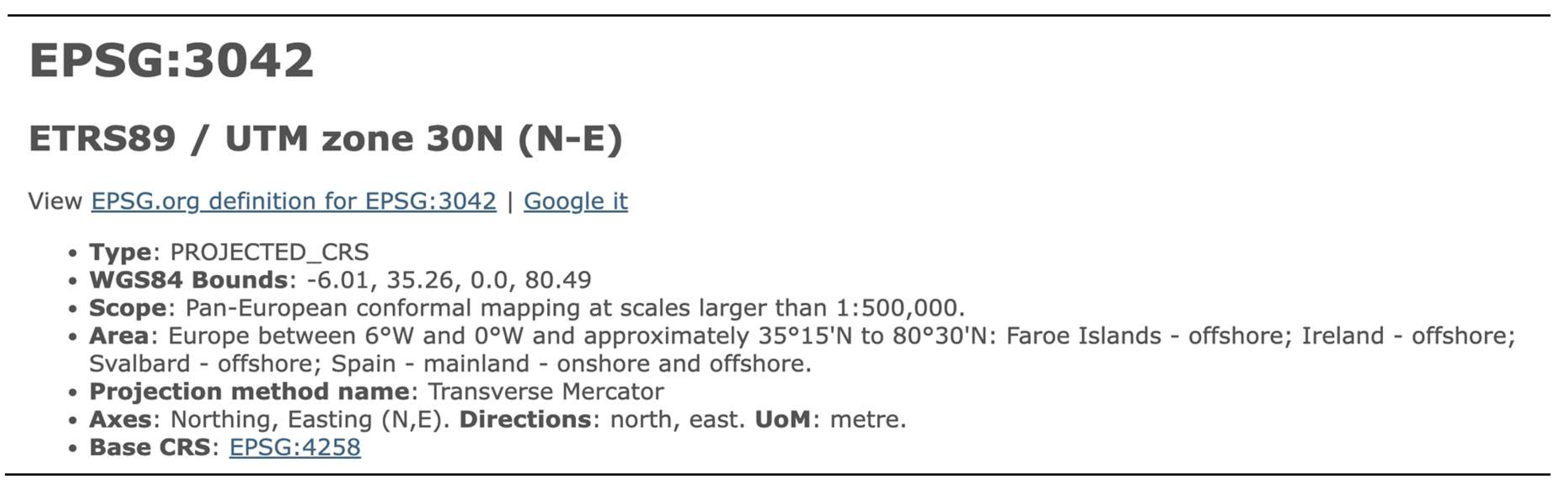

2.3.2. Coordinate Reference System (CRS)

2.3.3. Selection of a projection

- -

- CRS code: EPGS 3042

- -

- Geodetic datum: ETRS89

- -

- Projection: UTM zone 30N

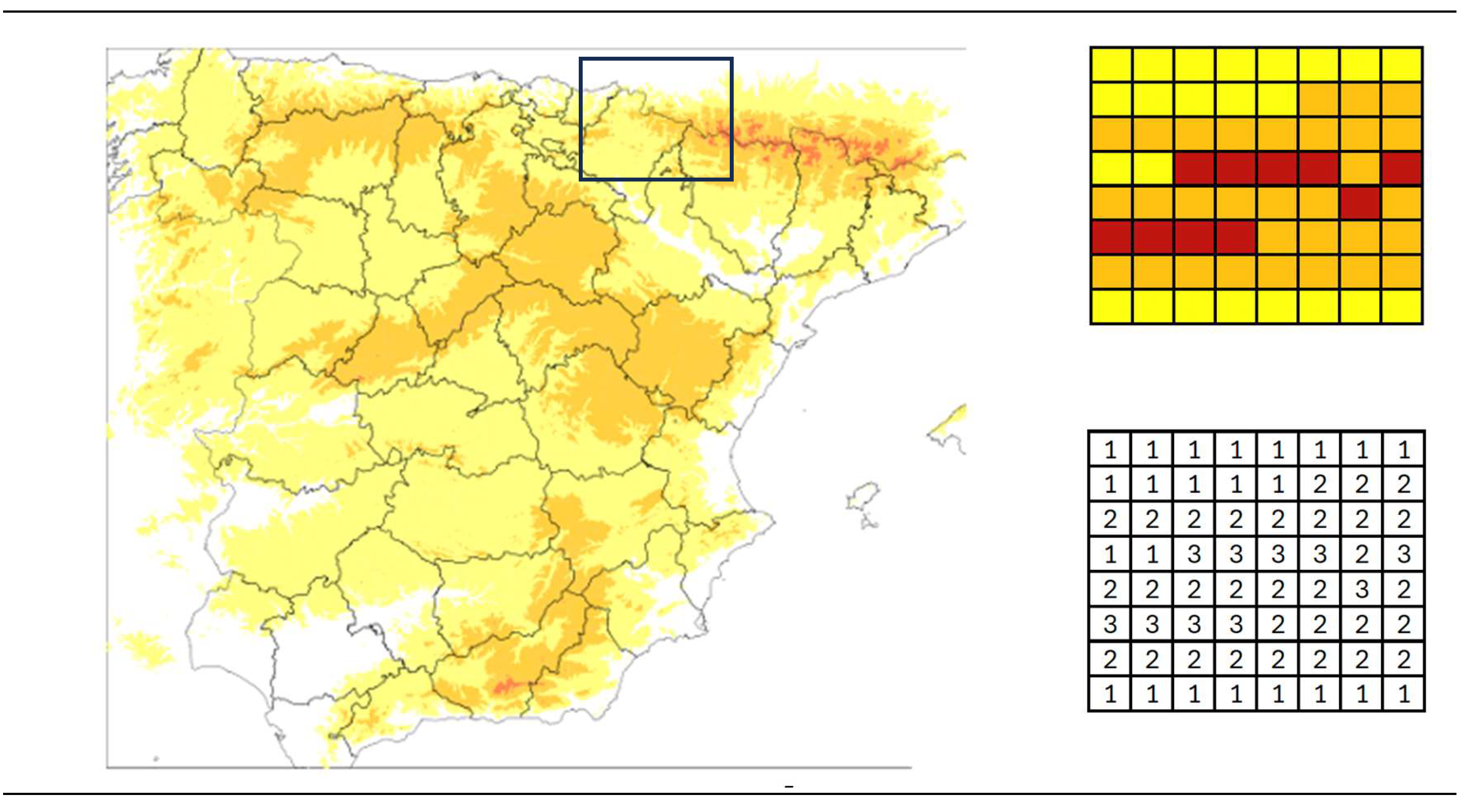

2.3.4. Types of spatial data

- a)

- Raster data is made up of pixels or grid cells. They are usually small squares of equal size. Each pixel value has a value, which is represented with a color (red, green, blue, etc.). Raster data are useful for storing data that varies continuously like elevation surfaces, temperature, rainfall and contamination (Figure 5).

- b)

-

Vector data: Vector data is not made up of a grid of pixels. Instead, vector graphics are comprised of vertices and paths. The three basic symbol types for vector data are points, lines, and polygons or areas (Figure 6).

- -

- Vector points are latitude-longitude (non-projected) or cartesian (projected) XY coordinates. They are useful to represent locations like houses, trees, or cities. The thickness of the dots usually represents data values (e.g., a large city will be represented by a larger diameter dot than a small town).

- -

- Vector lines connect the points with lines. When you connect the points in a set order, it becomes a vector line or path with each dot representing a vertex. Lines usually represent features that are linear in nature or can be built with small lines (like curves), for example, rivers, roads, and pipelines. The size of the different lines usually represents data values, like traffic (e.g., busier highways have thicker lines than abandoned roads).

- -

- Vector polygons join a set of vertices in a particular order and close it. Hence, in a polygon feature, the first and last coordinate pairs are the same. Vector polygons are used to show areas surrounded by boundaries like countries, regions, or grids. Data values are represented by different colors or a gradation of colors (e.g., highest values have higher values have more intense or darker colors).

3. WEB RESOURCES FOR SPATIAL DATA

3.1. GEOCODING POSTAL ADDRESSES

3.1.1. Google Maps Platform

3.1.2. ESRI’s ArcGIS Location Platform

3.1.3. Precisely’s Geo Addressing

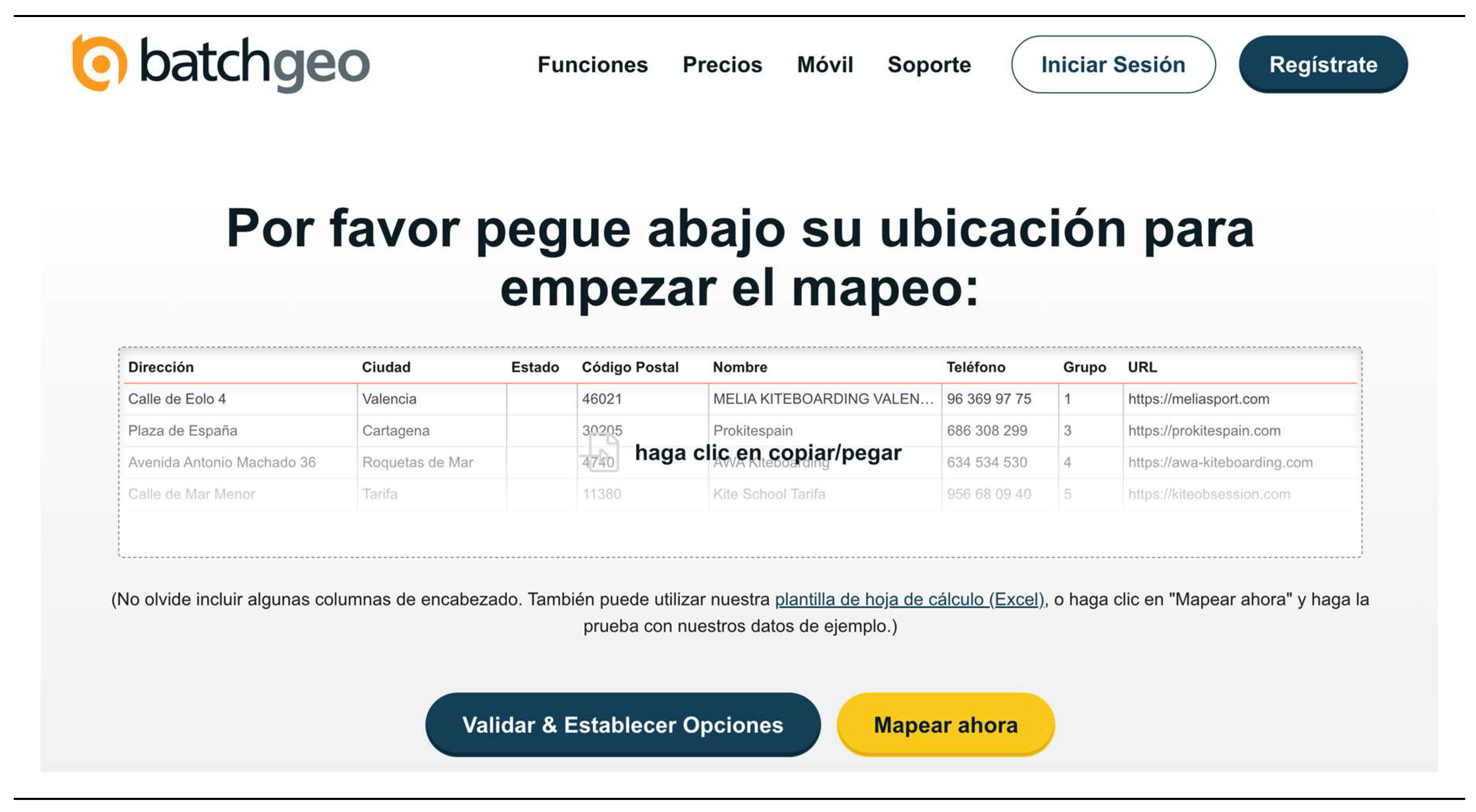

3.1.4. batchgeo.com

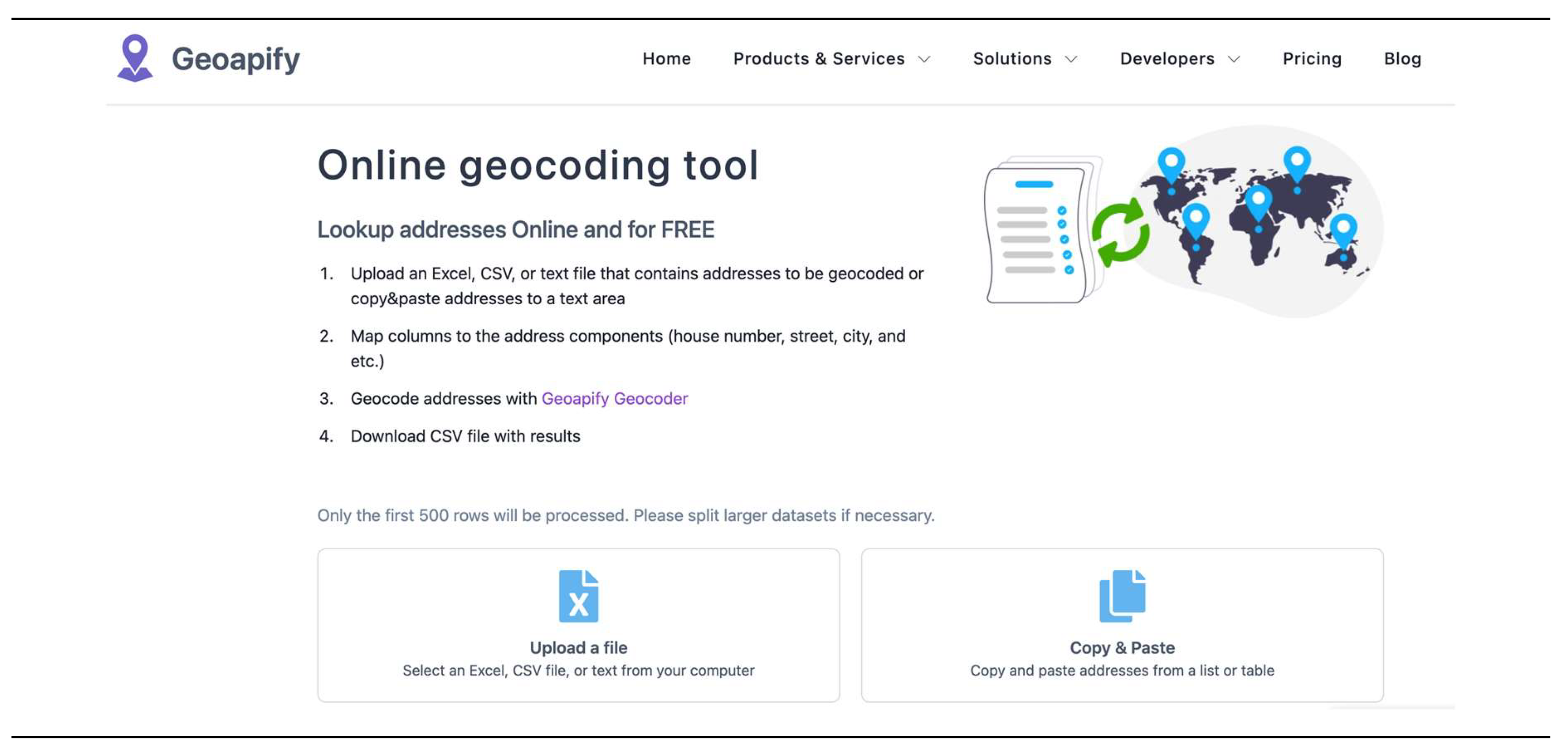

3.1.5. geoapify.com

- a)

- Original addresses.

- b)

- Found addresses.

- c)

- Their latitude and longitude coordinates.

- d)

- Their address components.

- e)

- A confidence coefficient, which indicates how confident they are in found address: a confidence equal to 1 tells that they are sure that the address is correct.

3.2. DIGITAL MAPS FORMATS

3.2.1. Proprietary digital maps

- a)

-

Shapefile: the GIS vendor ESRI ("Environmental Systems Research Institute") developed the shapefile format for its ArcGIS products. The terminology is a bit confusing, since there is no such thing as one shape file, but a collection of three (or four) files:

- -

- The map’s main file, with the extension *.shp, is a table which each record describes a shape with a list of its vertices.

- -

- An index file, with the extension *.shx, which links geometry (“shp” file) with attributes (“dbf” file) based on a number.

- -

- A dBase table, with the extension *.dbf, which contains the spatial features attributes with one record per feature. Attribute records in this file must be in the same order as records in the main “shp” file.

- -

- A *.prj file with the map projection information.

The first three files (*.shp, *.shx, *.dbf) are required and the fourth (*.prj) is optional, but highly recommended. The files should all be in the same directory and have the same file name, except for the file extension.Shapefiles are fundamentally row oriented, with each row representing a geometric shape and its associated attributes stored in columns (Table 1). The shapefiles are older structures and have a significant size limitation, up to 2 GB. It supports only vector data (point, line and polygon geometry types). ESRI has its own native raster data called Esri grid (*.adf). - b)

-

TAB: The GIS vendor Precisely develops the TAB file format for its MapInfo software products (Precisely 2024b). Again, these maps are a collection several files, which are related with two basic environments for working in MapInfo: the "Browser View" (*.TAB, *.DAT) and the "Mapper View" (*.MAP, *.ID, *.IND).TAB files are also row oriented. They have a size limitation, around 2 GB, though they depend on the MapInfo version and the computer capacity. It supports only vector data (point, line and polygon geometry types). MapInfo has its own native raster data called Multi-Resolution Raster, MRR (*.mrr).

- c)

- File Geodatabase (*.gdb): It is an ESRI’s data container, which is row-oriented, allowing the efficient storage and management of large amounts of geospatial data within a single file by using compression to minimize space. It supports vector and raster data and can store up to 1 TB of data per file (Wikipedia 2024b).

3.2.2. Open-source digital maps

- a)

- GeoArrow (*.arrow): It allows storing geospatial data in Apache Arrow and Arrow-compatible data structures and formats, which is specified as a columnar memory format (Table 1) and is supported by many programming languages and data libraries (GeoArrow 2024). Spatial information can be represented as a collection of discrete objects using points, lines and polygons (i.e., vector data). It was designed to manage big databases and has no specific technical size limit beyond the limitations of the file system (e.g., in the Windows operative system, it can reach more than 200 TB).

- a)

- Geography Markup Language or GML (*.gml): GML of the Open Geographic Consortium (OGC) is a standard Extensive Markup Language (XML) grammar for defining geographical features (Wikipedia 2024c). Hence, it is neither a row-oriented nor a column-oriented format. It organizes data hierarchically using nested elements. It supports point, line and polygon geometry types (only vector data, not raster). It has no specific technical size limit beyond the limitations of the file system. However, since it is a text format, large files can become unmanageable.

- b)

-

GeoJSON (*.geojson, *.json): It is an increasingly common format for open-source digital maps (Anselin 2023). It is the geographic augmentation of the JSON standard, which is derived from JavaScript Object Notation. This format is contained in a text file, and it is easy for machines to read, due to its highly structured nature in a hierarchical scheme (it is not strictly row or column oriented as other formats). It supports point, line and polygon geometry types (only vector data, not raster).It has no specific technical size limit beyond the limitations of the file system or the environment in which it is being used. However, since it is a text format, large files can become unmanageable.

- c)

- GeoPackage (*.gpkg): It is a universal file format built on the basis of SQLite, for sharing and transferring vector and raster spatial data (Open Geospatial Consortium 2024). It is a single file, which has been designed to store complex and voluminous data (up to 140 TB). Since SQLite is a type of the relation SQL database, it is specified as a row-oriented data.

- d)

- GeoParquet (*.parquet): It is an OGC under development standard that adds interoperable geospatial types (point, line, polygon) to Parquet (Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública 2024). Both Parquet and GeoParquet are defined as a column-oriented data format that is intended as a modern alternative to row-based CSV files. It was designed to manage big databases and has no specific technical size limit beyond the limitations of the Hadoop file system, which can reach several TB.

- e)

-

Keyhole Markup Language or KML (*.kml): KML allows geographic annotation and visualization within two-dimensional maps and three-dimensional Earth browsers (Wikipedia 2024d). Since it is an XML-based format, it is neither a row-oriented nor a column-oriented format. It organizes data hierarchically using nested elements. It was developed for use with Google Earth. The KML file specifies a wide set of vector data features (images, polygons, 3D models, textual descriptions, etc.) with the exception of raster data. It has no specific technical size limit beyond the limitations of the file system. It is advisable to keep KML files under a few megabytes to ensure good performance and responsiveness.For its reference system, KML uses 3D geographic coordinates: longitude, latitude, and altitude, in that order, with negative values for west, south, and below sea level. Altitude is expressed in meters. For example, the capital city of Spain, Madrid, has the following 3D geographic coordinates: (40.4168, -3.7038, 667).

- f)

-

SpatiaLite (*.sqlite): SpatiaLite is an open-source library intended to extend the SQLite core to support fully fledged Spatial SQL capabilities (Wikipedia 2024c). SQLite is intrinsically simple and lightweight. As an SQLite extension, it is a row-oriented database management system. SpatiaLite primarily focuses on vector data (polygons, points, lines), although it also includes limited support for raster data through its RasterLite2 extension. SpatiaLite databases have a theoretical maximum size limit of about 140 terabytes. However, practical limits are generally much lower, depending on the operating environment.Finally, it is important to note that a digital map can include one or more spatial layers and databases. For example, a map of a city can include only the spatial layer for zoning (e.g., districts) or other spatial layers for traffic density, public transportation routes, and population density, each of these independently analyzed with their own databases. Spatial layers can be of polygonal, point and linear types.

3.3. MAP VIEWERS

- -

- Zoom and Pan: zoom in and out and move around the map to explore different areas.

- -

- Layer Control: toggle different map layers on and off, such as roads, terrain, satellite imagery, and more.

- -

- Search and Query: search for specific locations, addresses, or points of interest and get detailed information about them.

- -

- Data Visualization: visualize various types of data, such as population density, weather patterns, or traffic conditions, on the map.

- -

- Upload digital maps: upload own digital maps to the platform to visualize them with a more complete base map.

4. DIGITAL MAP SERVERS AND SOFTWARE FOR SPATIAL DATA

4.1. WEB PAGES WITH FREE DIGITAL MAPS

4.1.1. OpenStreetMap, OSM (OpenStreetMap Foundation 2025)

4.1.2. GADM data (GADM 2022)

4.1.3. ArcGIS Hub (ESRI 2025c)

4.1.4. GISCO Geodata (Eurostat 2025)

4.1.5. Cartography of the Spanish Institute for Statistics (INE)

- a)

- Population in 1 km2 cells and associated digitalized cartography.

- b)

- Cartography of the Censal Sections.

- c)

- Electoral Census Street Map.

4.2. GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS (GIS)

4.2.1. ArcGIS Pro

4.2.2. QGIS (Quantum GIS)

4.2.3. MapInfo Pro

4.2.3. Google Earth Pro

4.3. INTRODUCTION TO GEODA SOFTWARE

5. CONCLUSIONS

| 1 | Other interesting map viewers are GeoMap.com (GeoMap 2025), DigitalAtlasProject.net (McDonald 2025), USGS (United States of the Interior 2025) and COVID-19 Dashboard (Johns Hopkins 2025), among many others. |

Appendix 1: Characteristics of digital map formats

| Extension | Source | Programing languages | Data formatting | Data | Weight | |

| Proprietary | ||||||

| Shapefiles | shp, shx, dbf, prj | ESRI | Java, C++, Python, SQL, HTML5 | Row-oriented | Vector* | 20 MB |

| TAB | tab, dat, map, id, ind | MapInfo | C++, .NET, Java | Row-oriented | Vector** | 20 MB |

| Geodatabase | gbd | ESRI | C++, Python, Java, .NET, SQL | Row-oriented | Vector, raster | 1 TB |

| Open source | ||||||

| GeoArrow | arrow | Apache Arrow | C++, Python, Java, JavaScript, R | Column-oriented | Vector | 200 TB |

| GML | gml | XML | Java, C++, Python, .NET | Hierarchical | Vector | Several GB |

| GeoJSON | geojson,json | JSON | JavaScript, Python, Java, C++ | Hierarchical | Vector | Several GB |

| GeoPackage | gpkg | SQLite | C++, Java, C | Row-oriented | Vector, raster | 140 TB |

| GeoParquet | parquet | Parquet | C++, Java, Python | Column-oriented | Vector | Several TB |

| KML | kml | XML | Java, C++, Python, JavaScript | Hierarchical | Vector | Several MB |

| SpatiaLite | sqlite | SQLite | C++, Java, C | Row-oriented | Vector*** | 140 TB |

References

- Anselin. An Introduction to Spatial Data Science with GeoDa Volume 1: Exploring Spatial Data. 2023. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/zrc8afa3.

- Anselin. Introducing GeoDa 1.22. GeoDa An Introduction to Spatial Data Science. 2025. Available online: https://geodacenter.github.io (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Başarsoft. MapInfo Pro. The World's Most Flexible, Extensible GIS Software. 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/nhcypcc4 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- BEEILAB. What is QGIS? Exploring the Power of Quantum GIS. 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/mryrwamv (accessed on 1 January 2025). Medium.

- Chasco C, Fernández-Avilés G. Análisis de datos espacio-temporales para la economía y el geomarketing. 2009. Ed. Netbiblo. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2uyamf2n.

- ESRI. Esri Grid format. 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4buzr9nr (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World. 2025. Available online: https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/en/browse/#d=2 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ESRI. Map Viewer. 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5n8p2z5k (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ESRI. ArcGIS Hub. 2025. Available online: https://hub.arcgis.com/search (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ESRI. Pricing for ArcGIS Pro. 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/3f584bzh (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- ESRI Developer. Geocoding. 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5n6dxuck (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- ESRI UK. ArcGIS Pro. The world's leading GIS software. 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/236uh4sm (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Eurostat. GISCO Grids. 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/54dvyupv (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Eurostat (2024b) Local administrative units (LAU). Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4y9srkvf.

- Eurostat (2024c) NUTS - Nomenclature of territorial units for statistics. Overview. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/7ktnn82v.

- Eurostat (2025) GISCO Geodata. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4cyj4kx6.

- GADM (2022) GADM data. Available online: https://gadm.org/data.html.

- Geoapify (2024) Online geocoding tool. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/ypwtsm4u.

- GeoArrow (2024) GeoArrow. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://geoarrow.org.

- GeoMap (2025) GeoMap.com. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://www.geamap.com/en.

- GISGeography (2024) Vector vs Raster in GIS: What’s the Difference? Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/38a485yb.

- Google Earth (2025) Download Google Earth Pro. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4rfr9mny.

- Google Maps Platform (2024) Geolocation API overview. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4bp6je9a.

- INE (2025a) Population in 1 km2 cells and associated digitalized cartography. In Population and Housing Census 2021. Advanced query system. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/52j85hmk.

- INE (2025b) Cartography of the Censal Sections and Electoral Census Street Map. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2dhmtu8u.

- Johns Hopkins (2025) COVID-19 Dashboard. Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE). Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- Ministerio para la Transformación Digital y de la Función Pública (2024) GeoParquet 1.0.0: new format for more efficient access to spatial data. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/y33sjs4c.

- OpenStreetMap Foundation (2025) OpenStreetMap. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/3cv3c9jv.

- Open Geospatial Consortium (2024) GeoPackage. An Open Format for Geospatial Information. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://www.geopackage.org.

- Ordnance Survey (2025) What is GIS? Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4767mzpr.

- Precisely (2024a) Geo Addressing. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/jfvh9tte.

- Precisely (2024b) MapInfo Pro. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/4ykpdsj6.

- Precisely (2024c) Multi Resolution Raster (MRR) - Revolutionizing Raster Performance and usage. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5fz9e62t.

- Precisely (2025) MapInfo Pro 30-Day Free Trial. Accessibility in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5ybce87v.

- QGIS (2025) QGIS download web page. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://www.qgis.org.

- SAFEGRAPH (2024a), Geospatial Data Analytics: What It Is, Benefits, and Top Use Cases. Web page accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/49667hs7.

- SAFEGRAPH (2024b), Top 10 Uses of Geospatial Data + Where to Get It. Web page accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yc5rap78.

- Softonic (2025) Google Earth for Mac. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/32kphz2b.

- Tobias M (2024) What is QGIS? In: Intro to Desktop GIS with QGIS. 2024-05-14. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yrkh3ux6.

- United States of the Interior (2025) USGS, U.S. Geological Survey. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://apps.nationalmap.gov/downloader/#/.

- Warmerdam F, Rouault E & others (2025) RasterLite2 – Rasters in SQLite DB. Accessed in January 2025. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/2tzyy6cy.

- Wikipedia (2024a) Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/5n9xmdmv.

- Wikipedia (2024b) Geodatabase (ESRI). Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/bdzbdhwe.

- ikipedia (2024c) Geography Markup Language. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/52xbcb88.

- Wikipedia (2024d) Keyhole Markup Language. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/yc3vtwd5.

- Wikipedia (2024e) SpatiaLite. Accessed in December 2024. Available online: https://tinyurl.com/3d8h3yhz.

| Row-oriented data formatting | Column-oriented data formatting | |

| 1, John, Smith, London, 27 | ID: 1, 2, 3, 4 | |

| 2, Mary, Taylor, Birmingham, 40 | Name: John, Mary, Celine, Peter | |

| 3, Celine, Brown, Liverpool, 72 | Surname: Smith, Taylor, Brown, Wilson | |

| 4, Peter, Wilson, Glasgow, 89 | Age: 27, 40, 72, 89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).