1. Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has profoundly impacted human health, both directly and indirectly. During the pandemic, widespread implementation of nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), such as social distancing, mask use, isolation, and quarantine, led to significant changes in human behavior [

1]. These measures resulted in a remarkable decrease in the global prevalence of epidemic respiratory pathogens, including seasonal influenza [

2].

In the 2023-2024 influenza season, flu severity was classified as moderate, with activity levels returning to pre-pandemic patterns [

3,

4]. According to the CDC, an estimated 40 million individuals in the United States contracted influenza, with 18 million seeking medical care, 470,000 hospitalized, and 28,000 fatalities. Elderly patients (≥65 years) were disproportionately affected, accounting for 68% of deaths and 50% of hospitalizations [

5]. Pediatric mortality also remained significant, with 724 estimated deaths among children and neonates. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive vaccination campaigns featuring vaccine compositions tailored to the circulating strains, alongside other preventive measures, such as widespread public health communication campaigns and the implementation of NPI, to mitigate the public health burden of seasonal influenza [

6]. Unfortunately, the pandemic also indirectly impacted immunization rates for other vaccine preventable diseases, including influenza [

7,

8].

The pandemic disrupted the global circulation of seasonal influenza, partly due to changes in air travel connectivity between world regions. Moreover, the initial decline in flu activity was strongly influenced by the global adoption of stringent public health measures including mask mandates and physical distancing [

9,

10,

11], which effectively curtailed person-to-person transmission of respiratory viruses.

Since the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in December 2019 it has infected over 700 million individuals globally and caused more than seven million deaths. The United States alone, was one of the most affected countries, with CDC estimates bordering 40 million COVID-19 infections occurred up to 2024 [

12].

This study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of influenza incidence, vaccination rates, and mortality in the United States across three critical phases: before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. By examining data from the 2018-2019 through 2023-2024 influenza seasons, we elucidate how the interplay between influenza and SARS-CoV-2 has reshaped public health strategies and underscore the urgent need for sustainable interventions to mitigate the dual burden of respiratory diseases in the post-pandemic era.

2. Materials and Methods

The influenza surveillance period follows a seasonal framework, spanning 52 or 53 weeks, beginning in week 36 of the current year and ending in week 35 of the subsequent year. This structure allows for consistent tracking and analysis of influenza trends over time. For this study, data from the 2018-2019 through 2023-2024 influenza seasons were retrieved from the CDC repository (

https://data.cdc.gov/), providing a comprehensive overview of influenza activity across six consecutive seasons. To investigate the interplay between COVID-19 and influenza dynamics during the pandemic, additional data on COVID-19 incidence from 2020 to 2024 were obtained from both the CDC repository and the global data platform “Our World in Data” (

https://ourworldindata.org/) (specifically for the containment and health index),. This dataset enabled a detailed exploration of the temporal and spatial fluctuations in influenza activity alongside the emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2. By integrating these datasets, the study aims to capture the impact of the pandemic on the circulation and incidence of seasonal influenza and to identify potential shifts in respiratory disease patterns influenced by public health interventions and changing societal behaviors. Data analysis and visualization were done in R studio 2024.04.2, and R package 4.4.1 was used for map visualization.

3. Results

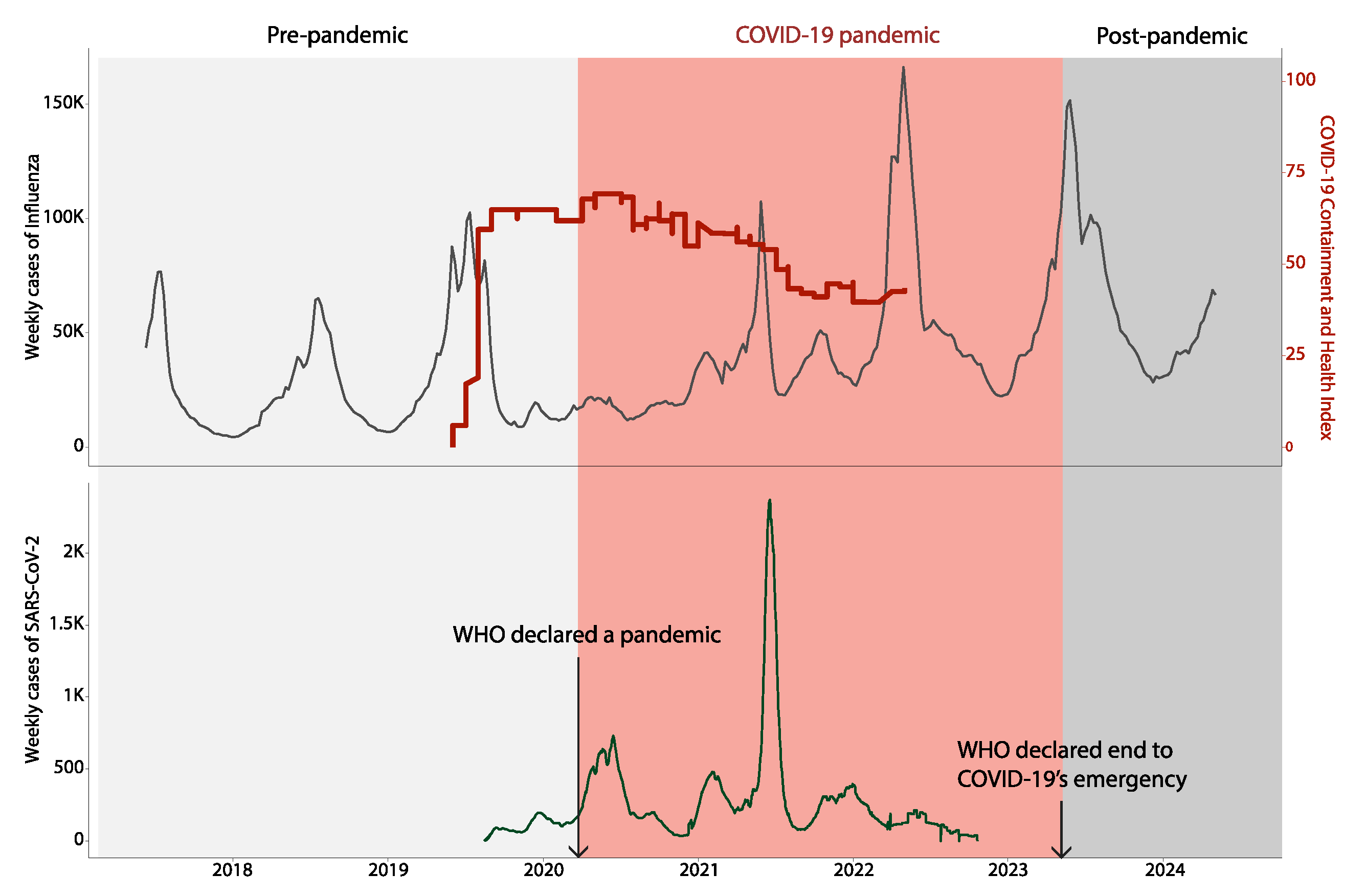

The analysis of weekly influenza case data spanning six influenza seasons (2018-2019 to 2023-2024) revealed notable temporal patterns influenced by the emergence and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 (

Figure 1).

During the pre-pandemic period (2018-2019 to 2019-2020), influenza cases followed predictable seasonality, with activity typically rising in late autumn, peaking in mid-winter, and tapering off by early spring. This cyclical pattern was disrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2022), with influenza activity experiencing an unprecedented decline. Influenza cases were markedly suppressed during the pandemic years, coinciding with the implementation of widespread nonpharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as mask-wearing, physical distancing, and international travel restrictions. It is worth noting that there was a decrease in testing for Influenza and other viruses, like dengue [

13], during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might have led to underreporting of cases [

11]. The containment and health index, plotted alongside influenza cases, reflects the intensity of these measures, which peaked in early 2020. In the post-pandemic period (2023-2024), influenza activity exhibited a robust rebound, returning to levels consistent with the pre-pandemic era. This resurgence underscores the waning impact of NPIs as public health measures were relaxed and global travel resumed. The results highlight how behavioral and policy-driven interventions, though effective in the short term, are not sufficient to sustain long-term suppression of respiratory pathogens like influenza.

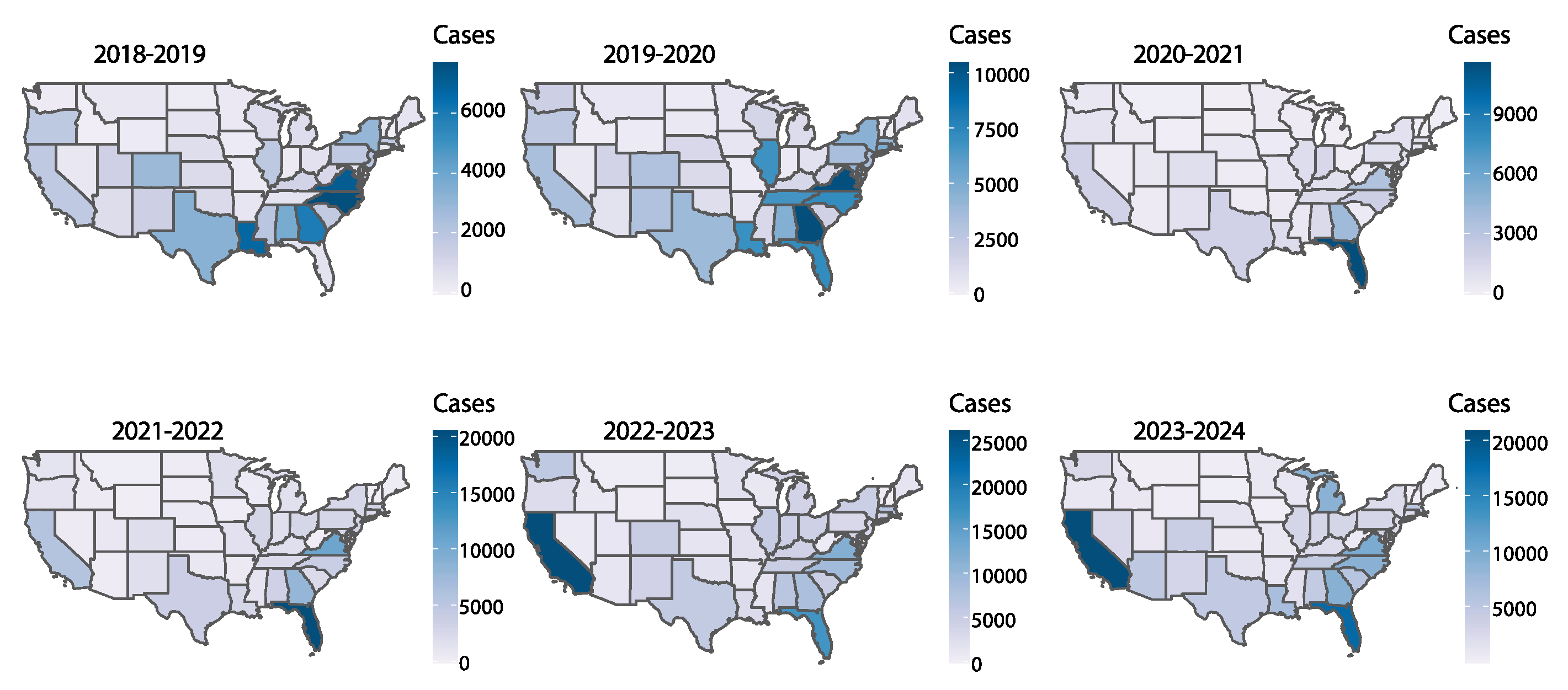

The geographic distribution of influenza cases across U.S. states over six influenza seasons illustrates the differential impact of the pandemic and subsequent recovery periods across regions (

Figure 2). Additionally, a correlation analysis indicated that states in the U.S. with higher flu incidence experienced more COVID-19 cases during and after the pandemic period (

Supplementary Figure S1). This indicates that the common risk factors, including population density, healthcare accessibility, and behavioral determinants, may affect the transmission dynamics of these respiratory viruses [

14].

Pre-pandemic seasons (2018-2019 and 2019-2020) show widespread influenza activity, with case hotspots appearing consistently across highly populated federal units - such as California, Texas, and New York. However, during the pandemic (2020-2021), influenza transmission was notably reduced nationwide, with no state showing significant activity. This decline aligns with reduced person-to-person contact, restricted mobility, and the widespread adoption of masking policies. The 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 seasons marked the resurgence of influenza, with case clusters re-emerging in several states. Interestingly, the geographic distribution during these seasons suggested a shift in hotspot locations, potentially influenced by varying levels of public health compliance, vaccine uptake, and demographic factors. By the 2023-2024 season, influenza activity was widely distributed again, emphasizing the adaptive nature of the virus and the need for sustained regional surveillance and targeted interventions.

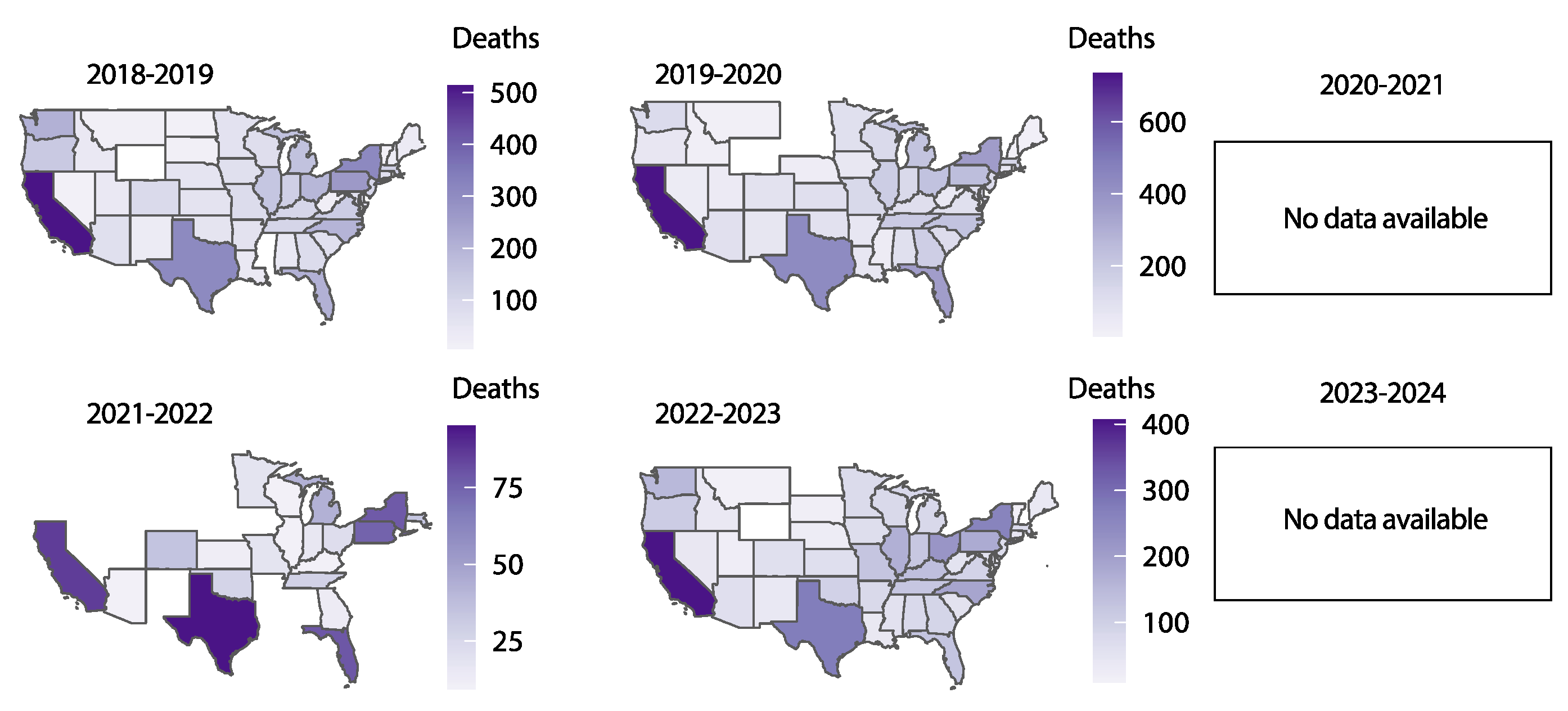

Influenza-related deaths mirrored the trends observed in case counts, with a pronounced reduction during the pandemic years (2020-2021) and a gradual return to pre-pandemic levels in subsequent seasons (

Figure 3). During the 2018-2019 and 2019-2020 seasons, influenza mortality was widespread, with higher death tolls observed in densely populated states and regions with older demographics. The 2020-2021 season showed a dramatic decline in mortality, reflecting the significant suppression of influenza transmission during this period. In the 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 seasons, influenza-related mortality began to increase again, coinciding with the resurgence in cases. However, geographic patterns of mortality showed some variation, likely influenced by differences in healthcare access, vaccination coverage, and the prevalence of underlying health conditions. Mortality data for the 2023-2024 season were unavailable at the time of this analysis, limiting the ability to fully assess recent trends. These findings underscore the critical role of effective surveillance, timely intervention, and vaccination campaigns in minimizing the burden of influenza-related deaths.

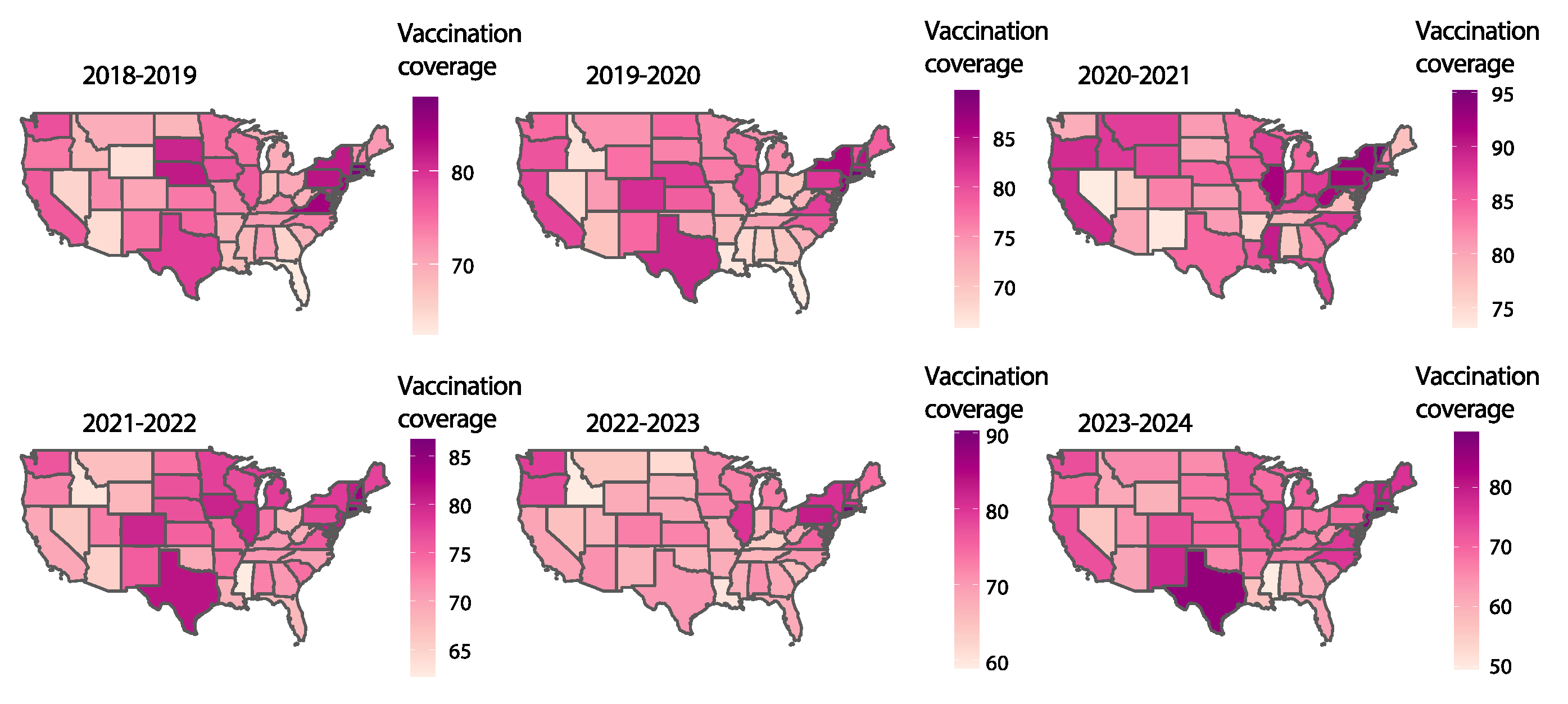

Influenza vaccination coverage varied substantially across states and seasons, reflecting differences in public health strategies, population behaviors, and vaccine acceptance (

Figure 4). Pre-pandemic seasons (2018-2019 and 2019-2020) exhibited moderate vaccination uptake, with coverage ranging from 40% to 80% across states. During the pandemic (2020-2021), vaccination rates increased slightly, likely due to heightened public awareness of respiratory diseases and enhanced public health messaging.

However, in the post-pandemic seasons (2022-2024), vaccination coverage exhibited considerable variability across states, with some regions showing declines in uptake. Despite the increased risk of co-circulating respiratory pathogens (i.e. respiratory syncytial virus, SARS-CoV-2, Streptococcus pneumoniae, human metapneumovirus), vaccination rates remained below optimal levels in several states, particularly in the southern and midwestern regions. However, there was a statistically significant increase in vaccination rates pre and post pandemic seasons scattered across some US states, though not uniformly. These patterns highlight the challenges of maintaining public interest and trust in vaccination campaigns after the acute phase of a pandemic has passed. Importantly, sustained and equitable vaccination efforts are necessary to mitigate the long-term impact of influenza and other vaccine-preventable respiratory pathogens.

4. Discussion

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic profoundly impacted human health on multiple levels. Beyond the direct effects of viral exposure, which included high mortality rates [

12] and chronic conditions such as long COVID-19 [

15,

16,

17], the pandemic indirectly disrupted the global epidemiology of respiratory pathogens, including the seasonal circulation of influenza strains. For three years, the pandemic-induced perturbation significantly altered the global dispersion of influenza viruses, although, by 2023, the observed pattern reverted to its pre-pandemic state. This phenomenon underscores the impact of public health interventions and behaviors on respiratory virus dynamics [

18,

19]. During the pre-pandemic period, influenza activity exhibited predictable seasonal patterns, peaking during mid-winter in highly populous states such as California, Texas, and New York. However, during the 2020-2021 season, the widespread implementation of NPIs such as mask-wearing, physical distancing, and travel restrictions led to an unprecedented suppression of influenza cases and related mortality across the United States. Another critical factor that must also be considered is the redirection of diagnostic efforts toward detecting SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples on a large scale, which has likely contributed to the underestimation of influenza prevalence and strain circulation.

Similar trends were observed globally, in US, Chile, South Korea and Chile [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. This also led to the underestimation of the circulation of other respiratory viruses including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among others during the first couple of years of the pandemic [

26,

27,

28]. However, an underestimation of other pathogens happened due to the extensive focus on SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis [

13]. The effectiveness of these measures was reflected in the peak of the containment and health index in early 2020 [

29]. However, the suppression of influenza activity was not largely sustained. With the ease of the restriction measures, return of global mobility, and effective influenza testing, an increase in influenza activity during the 2021-2023 seasons was observed, eventually returning to pre-pandemic levels in 2023-2024. Moreover, there was a significant improvement in the availability of diagnostic platforms, such as BioFire, which enhanced the ability to quickly and accurately detect various pathogens. This advancement played a crucial role in managing the spread of infectious diseases by enabling timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment [

30,

31].This resurgence highlights the adaptive nature of influenza viruses and the limitations of behavioral interventions as long-term suppression strategies.

Geographic analysis during the post-pandemic period revealed shift in influenza hotspots, influenced by regional disparities in public health compliance, vaccine administration, and demographic factors [

26,

32,

33,

34]. Regions with lower vaccination coverage, particularly in the southern and midwestern states, experienced variability in incidence of influenza activity during the flu seasons. Although public health campaigns during the pandemic temporarily increased vaccination rates due to heightened awareness [

34,

35,

36], this momentum waned in the post-pandemic period, with some states exhibiting significant declines. Influenza-related mortality mirrored these trends, with a dramatic reduction during in 2020-2021 followed by a gradual rise in subsequent seasons [

26]. Variations in healthcare access, vaccination coverage, and comorbid conditions likely contributed to the geographic disparities in mortality, consistent with prior research [

37,

38,

39,

40].

To mitigate the burden of influenza in future seasons, a comprehensive and sustained approach is essential. Increasing vaccination coverage remains the cornerstone of influenza control, with efforts needed to address vaccine hesitancy and logistical challenges, particularly in underserved regions [

35,

41]. Advances in genomic surveillance and predictive modeling offer opportunities to refine intervention strategies, enabling real-time monitoring and response to emerging threats [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Public health strategies should also incorporate lessons from the pandemic, combining targeted NPIs and advanced diagnostic strategies with timely vaccination campaigns during high-risk periods to reduce influenza transmission while minimizing societal disruption [

20,

21,

47].

5. Conclusions

The concurrent analysis of influenza and SARS-CoV-2 dynamics revealed significant interactions between the two respiratory pathogens during the study period. During the pandemic years, the reduced number of influenza cases suggests both direct and indirect effects. Directly, viral interference may have played a role, with SARS-CoV-2 outcompeting influenza for susceptible hosts. Indirectly, NPIs such as masking, physical distancing, and reduced travel significantly suppressed influenza spread. However, as public health measures were relaxed, influenza re-emerged, demonstrating the virus’s inherent adaptability and the challenges of maintaining long-term suppression. The resurgence of influenza in the post-pandemic period highlights the critical importance of integrating surveillance systems for multiple respiratory pathogens. Understanding the dynamics of co-circulating viruses is essential for developing effective public health strategies that minimize the burden of respiratory diseases and enhance preparedness for future pandemics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1. Positive Correlation Between Flu Cases and COVID-19 Cases Across Three Influenza Seasons (2020–2023). Scatterplots showing the correlation between the log-transformed flu cases (x-axis) and log-transformed COVID-19 cases (y-axis) for the 2020–2021, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023 influenza seasons across U.S. states. Each point represents a state, and the blue line denotes the line of best fit. The Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and corresponding p-value are presented for each season.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Data curation, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Formal analysis, Sobur Ali, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Investigation, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Methodology, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Supervision, Taj Azarian and Eleonora Cella; Visualization, Marta Giovanetti and Eleonora Cella; Writing – original draft, Marta Giovanetti, Svetoslav Nanev Slavov, and Eleonora Cella; Writing – review & editing, Marta Giovanetti, Sobur Ali, Svetoslav Nanev Slavov, Taj Azarian and Eleonora Cella. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study is freely available in CDC data website and is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

M. G.’s funding is provided by PON “Ricerca e Innovazione” 2014-2020 and by the CRP-ICGEB RESEARCH GRANT 2020 Project CRP/BRA20-03, Contract CRP/20/03.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhang, J.; Litvinova, M.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wu, Q.; Merler, S.; Viboud, C.; Vespignani, A.; et al. Changes in Contact Patterns Shape the Dynamics of the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. Science 2020, 368, 1481–1486. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Shaman, J.; Pei, S. Quantifying the Impact of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions on Influenza Transmission in the United States. J Infect Dis 2021, 224, 1500–1508. [CrossRef]

- 2023-2024 Influenza Season Summary: Influenza Severity Assessment, Burden and Burden Prevented | Influenza (Flu) | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/whats-new/flu-summary-addendum-2023-2024.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Past Flu Season Severity Assessments | Influenza (Flu) | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/php/surveillance/past-seasons.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Preliminary Estimated Flu Disease Burden 2023–2024 Flu Season | Flu Burden | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu-burden/php/data-vis/2023-2024.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Influenza Activity in the United States during the 2023–2024 Season and Composition of the 2024–2025 Influenza Vaccine | Influenza (Flu) | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/whats-new/flu-summary-2023-2024.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2023-2024/flu-summary-2023-2024.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Routine Immunizations on Schedule for Everyone (RISE) | Vaccines & Immunizations | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/php/rise/index.html (accessed on 31 December 2024).

- Hamson, E.; Forbes, C.; Wittkopf, P.; Pandey, A.; Mendes, D.; Kowalik, J.; Czudek, C.; Mugwagwa, T. Impact of Pandemics and Disruptions to Vaccination on Infectious Diseases Epidemiology Past and Present. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023, 19, 2219577. [CrossRef]

- Brownstein, J.S.; Wolfe, C.J.; Mandl, K.D. Empirical Evidence for the Effect of Airline Travel on Inter-Regional Influenza Spread in the United States. PLoS Med 2006, 3, 1826–1835. [CrossRef]

- Lemey, P.; Rambaut, A.; Bedford, T.; Faria, N.; Bielejec, F.; Baele, G.; Russell, C.A.; Smith, D.J.; Pybus, O.G.; Brockmann, D.; et al. Unifying Viral Genetics and Human Transportation Data to Predict the Global Transmission Dynamics of Human Influenza H3N2. PLoS Pathog 2014, 10. [CrossRef]

- Betancourt-Cravioto, M.; Falcón-Lezama, J.A.; Saucedo-Martínez, R.; Alfaro-Cortés, M.M.; Tapia-Conyer, R. Public Health and Economic Benefits of Influenza Vaccination of the Population Aged 50 to 59 Years without Risk Factors for Influenza Complications in Mexico: A Cross-Sectional Epidemiological Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 188. [CrossRef]

- Preliminary Estimates of COVID-19 Burden for 2024-2025 | COVID-19 | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/php/surveillance/burden-estimates.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Olive, M.M.; Baldet, T.; Devillers, J.; Fite, J.; Paty, M.C.; Paupy, C.; Quénel, P.; Quillery, E.; Raude, J.; Stahl, J.P.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic Should Not Jeopardize Dengue Control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2020, 14, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Similarities and Differences between COVID-19 and Influenza Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-similarities-and-differences-with-influenza (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Roever, L.; Cavalcante, B.R.R.; Improta-Caria, A.C. Long-Term Consequences of COVID-19 on Mental Health and the Impact of a Physically Active Lifestyle: A Narrative Review. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2023, 22, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Vahratian, A.; Saydah, S.; Bertolli, J.; Unger, E.R.; Gregory, C.O. Prevalence of Post–COVID-19 Condition and Activity-Limiting Post–COVID-19 Condition Among Adults. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2451151–e2451151. [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, C.; Collins, L.F.; Malani, P. Long-Term Health Consequences of COVID-19. JAMA 2020, 324, 1723–1724. [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, T.; Dooley, L.; Ferroni, E.; Al-Ansary, L.A.; van Driel, M.L.; Bawazeer, G.A.; Jones, M.A.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Clark, J.; Beller, E.M.; et al. Physical Interventions to Interrupt or Reduce the Spread of Respiratory Viruses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Lasheras, I.; Perfeito, L.; Mesquita, S.; Gonçalves-Sá, J. The Effects of Weather and Mobility on Respiratory Viruses Dynamics before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the USA and Canada. PLOS digital health 2023, 2. [CrossRef]

- Bonacina, F.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Colizza, V.; Lopez, O.; Thomas, M.; Poletto, C. Global Patterns and Drivers of Influenza Decline during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 128, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tsui, J.L.-H.; Gutierrez, B.; Moreno, S.B.; Plessis, L. du; Deng, X.; Cai, J.; Bajaj, S.; Suchard, M.A.; Pybus, O.G.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Interventions Reshaped the Global Dispersal of Seasonal Influenza Viruses. Science (1979) 2024, 386. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Son, H.S. Analysis of the Incidence of Influenza before and after the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea. Tropical Medicine & International Health 2024, 29, 1018–1025. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shen, C.; Luo, J.; Yu, W. Decreased Incidence of Influenza During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Gen Med 2022, 15, 2957–2962. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, E.; Mook, P.; … K.V.-W. epidemiological; 2021, undefined Review of Global Influenza Circulation, Late 2019 to 2020, and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Influenza Circulation. iris.who.intEA Karlsson, PAN Mook, K Vandemaele, J Fitzner, A Hammond, V Cozza, W Zhang, A MoenWeekly epidemiological record, 2021•iris.who.int. [CrossRef]

- Cowling, B.J.; Ali, S.T.; Ng, T.W.Y.; Tsang, T.K.; Li, J.C.M.; Fong, M.W.; Liao, Q.; Kwan, M.Y.; Lee, S.L.; Chiu, S.S.; et al. Impact Assessment of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions against Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Influenza in Hong Kong: An Observational Study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e279–e288. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.J.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Budd, A.P.; Brammer, L.; Sullivan, S.; Pineda, R.F.; Cohen, C.; Fry, A.M. Decreased Influenza Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020, 69, 1305–1309. [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Ishikane, M.; Ueda, P. Seasonal Influenza Activity During the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Japan. JAMA 2020, 323, 1969–1971. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Broberg, E.K.; Campbell, H.; Nair, H.; Redlberger-Fritz, M.; Emborg, H.D.; Trebbien, R.; Ellis, J.; Bernal, J.L.; et al. Seasonality of Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Its Association with Meteorological Factors in 13 European Countries, Week 40 2010 to Week 39 2019. Euro Surveill 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Hale, T.; Angrist, N.; Goldszmidt, R.; Kira, B.; Petherick, A.; Phillips, T.; Webster, S.; Cameron-Blake, E.; Hallas, L.; Majumdar, S.; et al. A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker). Nature Human Behaviour 2021 5:4 2021, 5, 529–538. [CrossRef]

- Comyn, A.; Ronayne, A.; Nielsen, M.J.; Cleary, J.; Cunney, R.; Drew, R.J. BioFire Film Array Blood Culture Identification Panel for Rapid Detection of Pathogens from Sterile Sites - A Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Open Infect Dis J 2018, 10, 15–22. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.O.; Ochoa, A.R.; Hall, S.L.; Voelker, C.R.; Mahoney, R.E.; McDaniel, J.S.; Blackburn, A.; Asin, S.N.; Yuan, T.T. Comparison of next Generation Diagnostic Systems (NGDS) for the Detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Lab Anal 2022, 36, e24285. [CrossRef]

- Bonacina, F.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Colizza, V.; Lopez, O.; Thomas, M.; Poletto, C. Global Patterns and Drivers of Influenza Decline during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2023, 128, 132–139. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Chun, J.Y.; Lee, S.; Yoo, D.; Kim, Y.; Ali, S.T.; Chun, B.C. Epidemiology and Transmission Dynamics of Infectious Diseases and Control Measures. Viruses 2022, 14, 2510. [CrossRef]

- McLean, H.Q.; Belongia, E.A. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness: New Insights and Challenges. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2021, 11, a038315. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.K.; WEI, W.I.; Tang, A.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Lee, S.S. Influenza Vaccine Uptake, COVID-19 Vaccination Intention and Vaccine Hesitancy among Nurses: A Survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2021, 114, 103854. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Rajaram, S.; English, P.M. How the COVID 19 Pandemic Will Shape Influenza Public Health Initiatives: The UK Experience. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18, 2056399. [CrossRef]

- Lafond, K.E.; Nair, H.; Rasooly, M.H.; Valente, F.; Booy, R.; Rahman, M.; Kitsutani, P.; Yu, H.; Guzman, G.; Coulibaly, D.; et al. Global Role and Burden of Influenza in Pediatric Respiratory Hospitalizations, 1982–2012: A Systematic Analysis. PLoS Med 2016, 13. [CrossRef]

- Molinari, N.A.M.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; Messonnier, M.L.; Thompson, W.W.; Wortley, P.M.; Weintraub, E.; Bridges, C.B. The Annual Impact of Seasonal Influenza in the US: Measuring Disease Burden and Costs. Vaccine 2007, 25, 5086–5096. [CrossRef]

- About Estimated Flu Burden | Flu Burden | CDC Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu-burden/php/about/index.html (accessed on 21 December 2024).

- Salman, M.; Badar, N.; Ikram, A.; Nisar, N.; Farooq, U. Estimation of Seasonal Influenza Disease Burden Using Sentinel Site Data in Pakistan 2017-2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J. V.; Wyka, K.; White, T.M.; Picchio, C.A.; Rabin, K.; Ratzan, S.C.; Parsons Leigh, J.; Hu, J.; El-Mohandes, A. Revisiting COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy around the World Using Data from 23 Countries in 2021. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, J.; Megill, C.; Bell, S.M.; Huddleston, J.; Potter, B.; Callender, C.; Sagulenko, P.; Bedford, T.; Neher, R.A. Nextstrain: Real-Time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 4121–4123. [CrossRef]

- Hill, V.; Githinji, G.; Vogels, C.B.F.; Bento, A.I.; Chaguza, C.; Carrington, C.V.F.; Grubaugh, N.D. Toward a Global Virus Genomic Surveillance Network. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 861–873. [CrossRef]

- Brito, A.F.; Semenova, E.; Dudas, G.; Hassler, G.W.; Kalinich, C.C.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Ho, J.; Tegally, H.; Githinji, G.; Agoti, C.N.; et al. Global Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Cella, E.; Fonseca, V.; Branda, F.; Tosta, S.; Moreno, K.; Schuab, G.; Ali, S.; Slavov, S.N.; Scarpa, F.; Santos, L.A.; et al. Integrated Analyses of the Transmission History of SARS-CoV-2 and Its Association with Molecular Evolution of the Virus Underlining the Pandemic Outbreaks in Italy, 2019-2023. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2024, 149, 107262. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Giovanetti, M.; Johnston, C.; Urdaneta-Páez, V.; Azarian, T.; Cella, E. From Emergence to Evolution: Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in Florida. Pathogens 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1095 2024, 13, 1095. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Kawashima, R. Disappearance and Re-Emergence of Influenza during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Association with Infection Control Measures. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).