Submitted:

23 November 2024

Posted:

26 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

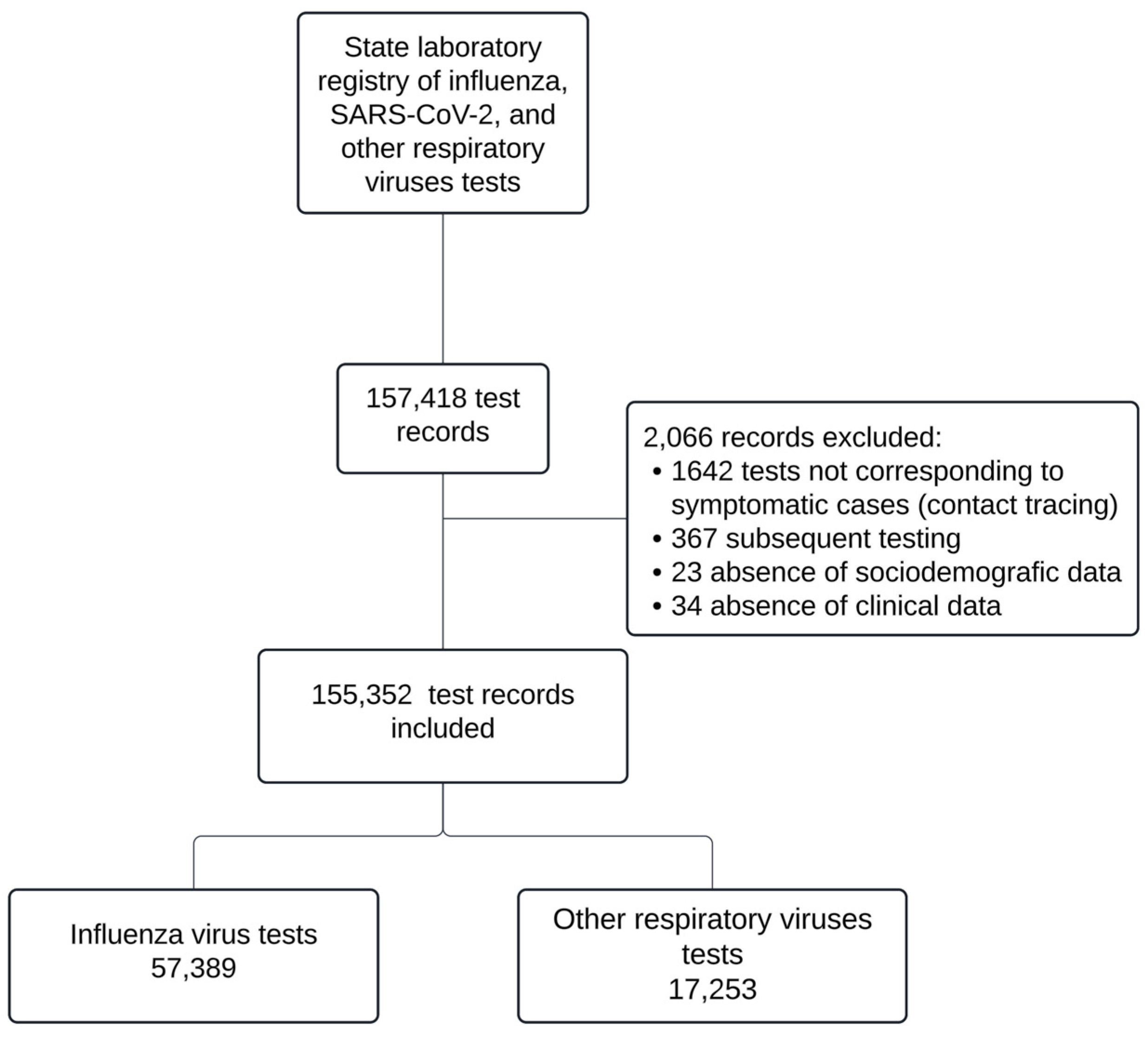

2.2. Population and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Viral Testing

2.4. Testing Restrictions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

| Influenza | RSV* | HEV/HRV* | hMPV* | HPIV* | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | SE | P-value | β | SE | P-value | β | SE | P-value | β | SE | P-value | β | SE | P-value |

| Constant (β0) | 2.365 | 0.166 | <0.001 | 0.215 | 0.193 | 0.265 | -2.821 | 0.360 | <0.001 | 0.016 | 0.208 | 0.937 | -0.964 | 0.254 | <0.001 |

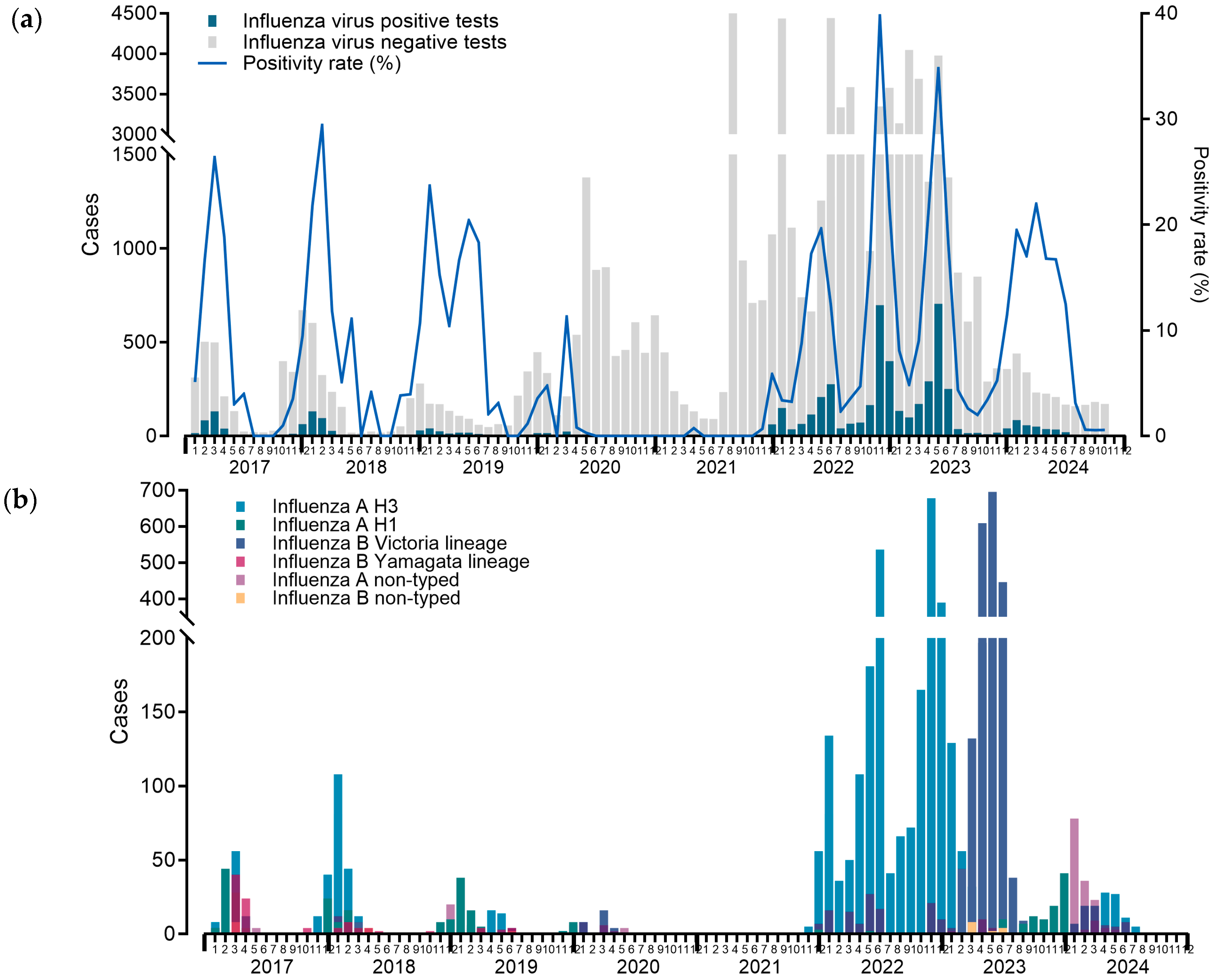

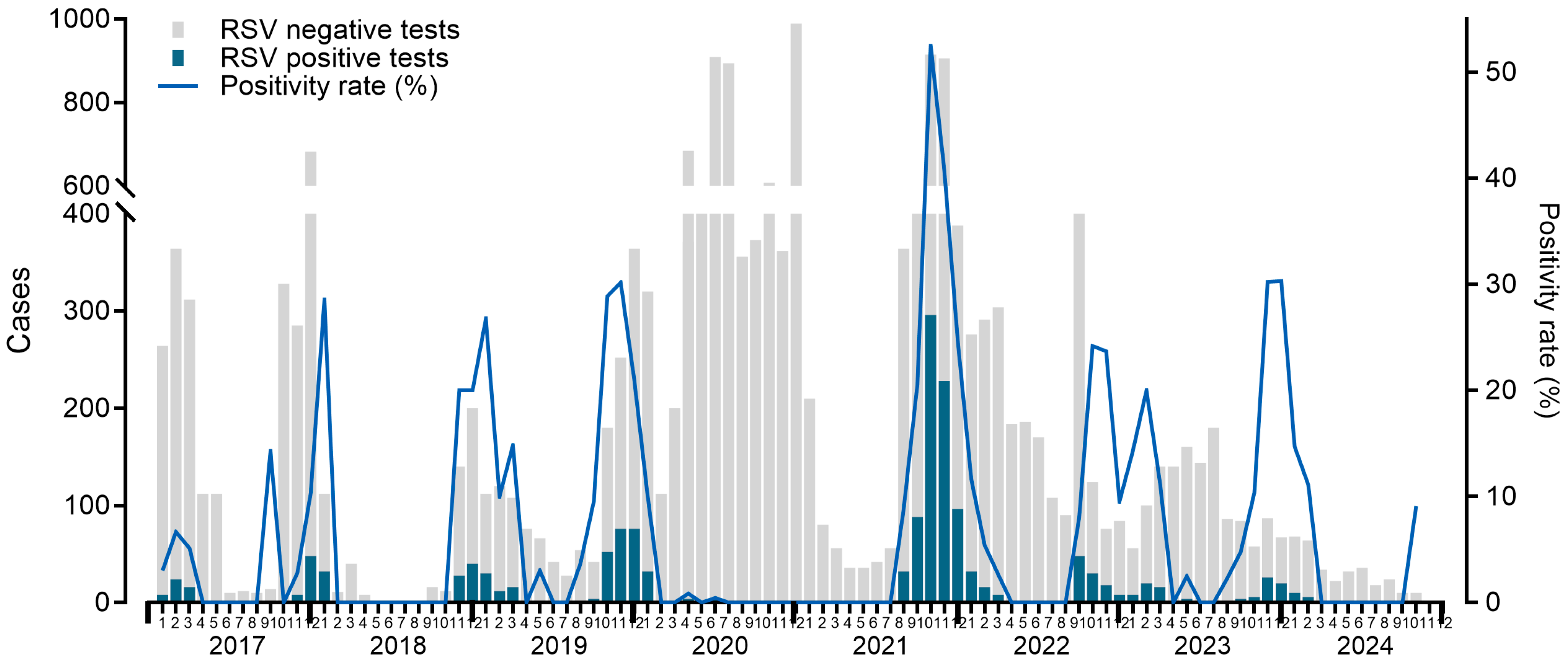

| Time (β1) | -1.030 | 0.180 | <0.001 | 0.939 | 0.191 | <0.001 | 2.988 | 0.301 | 0.566 | 0.405 | 0.210 | 0.054 | 1.049 | 0.240 | <0.001 |

| Level (β2) | |||||||||||||||

| 2020-2021 | -4.266 | 0.670 | <0.001 | -6.428 | 0.629 | <0.001 | -1.170 | 0.308 | <0.001 | -1.200 | 0.364 | 0.001 | -5.912 | 1.035 | <0.001 |

| 2022 | 9.418 | 0.686 | <0.001 | 5.367 | 0.658 | <0.001 | -1.250 | 0.402 | 0.002 | 0.679 | 0.428 | 0.112 | 4.720 | 1.060 | <0.001 |

| Trend (β3) | |||||||||||||||

| 2020-2021 | 0.066 | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.086 | 0.009 | <0.001 | -0.016 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.005 | 0.043 | 0.056 | 0.014 | <0.001 |

| 2022 | -0.013 | 0.003 | <0.001 | -0.024 | 0.003 | <0.001 | -0.044 | 0.004 | <0.001 | -0.016 | 0.003 | <0.001 | -0.017 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Costa VGD, Gomes AJC, Bittar C, Geraldini DB, Previdelli da Conceição PJ, Cabral ÁS, Carvalho T, Biselli JM, Provazzi PJS, Campos GRF, Sanches PRDS, Costa PI, Nogueira ML, Araujo JP Jr, Spilki FR, Calmon MF, Rahal P. Burden of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Viruses in Suspected COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional and Meta-Analysis Study. Viruses. 2023 Mar 1;15(3):665. [CrossRef]

- Matias G, Taylor R, Haguinet F, Schuck-Paim C, Lustig R, Shinde V. Estimates of hospitalization attributable to influenza and RSV in the US during 1997-2009, by age and risk status. BMC Public Health. 2017 Mar 21;17(1):271. [CrossRef]

- Thindwa D, Li K, Cooper-Wootton D, Zheng Z, Pitzer VE, Weinberger DM. Global patterns of rebound to normal RSV dynamics following COVID-19 suppression. BMC Infect Dis. 2024 Jun 25;24(1):635. [CrossRef]

- Del Riccio M, Caini S, Bonaccorsi G, Lorini C, Paget J, van der Velden K, Meijer A, Haag M, McGovern I, Zanobini P. Global analysis of respiratory viral circulation and timing of epidemics in the pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 pandemic eras, based on data from the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). Int J Infect Dis. 2024 Jul;144:107052. [CrossRef]

- Hu W, Fries AC, DeMarcus LS, Thervil JW, Kwaah B, Brown KN, Sjoberg PA, Robbins AS. Circulating Trends of Influenza and Other Seasonal Respiratory Viruses among the US Department of Defense Personnel in the United States: Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 May 13;19(10):5942. [CrossRef]

- Guadalupe-Fernández V, Martínez-Solanas E, Sabrià-Sunyé A, Ferrer-Mikoly C, Martínez-Mateo A, Ciruela-Navas P, Mendioroz J, Basile L; Epidemiological Surveillance Network of Catalonia. Investigating epidemiological distribution (temporality and intensity) of respiratory pathogens following COVID-19 de-escalation process in Catalonia, September 2016-June 2021: Analysis of regional surveillance data. PLoS One. 2024 Feb 9;19(2):e0285892. [CrossRef]

- Almeida T, Guimarães JT, Rebelo S. Epidemiological Changes in Respiratory Viral Infections in Children: The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses. 2023 Sep 5;15(9):1880. [CrossRef]

- Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, Brammer L, Sullivan S, Pineda RF, Cohen C, Fry AM. Decreased Influenza Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Sep 18;69(37):1305-1309. [CrossRef]

- Agha R, Avner JR. Delayed Seasonal RSV Surge Observed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021 Sep;148(3):e2021052089. [CrossRef]

- Kurai D, Natori M, Yamada M, Zheng R, Saito Y, Takahashi H. Occurrence and disease burden of respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory pathogens in adults aged ≥65 years in community: A prospective cohort study in Japan. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2022 Mar;16(2):298-307. [CrossRef]

- Huang QS, Wood T, Jelley L, Jennings T, Jefferies S, Daniells K, Nesdale A, Dowell T, Turner N, Campbell-Stokes P, Balm M, Dobinson HC, Grant CC, James S, Aminisani N, Ralston J, Gunn W, Bocacao J, Danielewicz J, Moncrieff T, McNeill A, Lopez L, Waite B, Kiedrzynski T, Schrader H, Gray R, Cook K, Currin D, Engelbrecht C, Tapurau W, Emmerton L, Martin M, Baker MG, Taylor S, Trenholme A, Wong C, Lawrence S, McArthur C, Stanley A, Roberts S, Rahnama F, Bennett J, Mansell C, Dilcher M, Werno A, Grant J, van der Linden A, Youngblood B, Thomas PG; NPIsImpactOnFlu Consortium; Webby RJ. Impact of the COVID-19 nonpharmaceutical interventions on influenza and other respiratory viral infections in New Zealand. Nat Commun. 2021 Feb 12;12(1):1001. [CrossRef]

- Bardsley M, Morbey RA, Hughes HE, Beck CR, Watson CH, Zhao H, Ellis J, Smith GE, Elliot AJ. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in England during the COVID-19 pandemic, measured by laboratory, clinical, and syndromic surveillance: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Jan;23(1):56-66. [CrossRef]

- Yeoh DK, Foley DA, Minney-Smith CA, Martin AC, Mace AO, Sikazwe CT, Le H, Levy A, Blyth CC, Moore HC. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Public Health Measures on Detections of Influenza and Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Children During the 2020 Australian Winter. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 15;72(12):2199-2202. [CrossRef]

- Falsey AR, Cameron A, Branche AR, Walsh EE. Perturbations in Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activity During the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2022 Dec 28;227(1):83-86. [CrossRef]

- Li M, Cong B, Wei X, Wang Y, Kang L, Gong C, Huang Q, Wang X, Li Y, Huang F. Characterising the changes in RSV epidemiology in Beijing, China during 2015-2023: results from a prospective, multi-centre, hospital-based surveillance and serology study. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2024 Mar 27;45:101050. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T, Chen D, Chen Q, Jin X, Su M, Zhang H, Tian L, Wen S, Zhong L, Ma Y, Ma D, Liang L, Lu X, Ni Q, Yang N, Pi G, Zhu Y, Chen X, Ma J, Jiang M, Wang J, Luo X, Li L, Zhang X, Ma Z, Zhang M, Zhang H, Lin L, Xiao N, Jiang W, Gu W, Cai D, Chen H, Chen L, Lei J, Du H, Li Y, Shao L, Shang Y, Xie N, Lei X, Ding S, Liang Y, Dong L, Chen X, Li Y, Zhang X, He B, Ren L, Liu E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on RSV outbreaks in children: A multicenter study from China. Respir Med. 2024 Oct 3;234:107828. [CrossRef]

- Hamid S, Winn A, Parikh R, Jones JM, McMorrow M, Prill MM, Silk BJ, Scobie HM, Hall AJ. Seasonality of Respiratory Syncytial Virus - United States, 2017-2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023 Apr 7;72(14):355-361. [CrossRef]

- Chen B, Zhu Z, Li Q, He D. Resurgence of different influenza types in China and the US in 2021. Math Biosci Eng. 2023 Feb 1;20(4):6327-6333. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Son HS. Analysis of the incidence of influenza before and after the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Trop Med Int Health. 2024 Nov 6. [CrossRef]

- Pendrey CG, Strachan J, Peck H, Aziz A, Moselen J, Moss R, Rahaman MR, Barr IG, Subbarao K, Sullivan SG. The re-emergence of influenza following the COVID-19 pandemic in Victoria, Australia, 2021 to 2022. Euro Surveill. 2023 Sep;28(37):2300118. [CrossRef]

- Rolfes MA, Talbot HK, McLean HQ, Stockwell MS, Ellingson KD, Lutrick K, Bowman NM, Bendall EE, Bullock A, Chappell JD, Deyoe JE, Gilbert J, Halasa NB, Hart KE, Johnson S, Kim A, Lauring AS, Lin JT, Lindsell CJ, McLaren SH, Meece JK, Mellis AM, Moreno Zivanovich M, Ogokeh CE, Rodriguez M, Sano E, Silverio Francisco RA, Schmitz JE, Vargas CY, Yang A, Zhu Y, Belongia EA, Reed C, Grijalva CG. Household Transmission of Influenza A Viruses in 2021-2022. JAMA. 2023 Feb 14;329(6):482-489. [CrossRef]

- Cao G, Guo Z, Liu J, Liu M. Change from low to out-of-season epidemics of influenza in China during the COVID-19 pandemic: A time series study. J Med Virol. 2023 Jun;95(6):e28888. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Jia M, Jiang M, Cao Y, Dai P, Yang J, Yang X, Xu Y, Yang W, Feng L. Increased population susceptibility to seasonal influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic in China and the United States. J Med Virol. 2023 Oct;95(10):e29186. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Chan KH, Suen LK, Chan KP, Wang X, Cao P, He D, Peiris JS, Wong CM. Impact of the 2009 H1N1 Pandemic on Age-Specific Epidemic Curves of Other Respiratory Viruses: A Comparison of Pre-Pandemic, Pandemic and Post-Pandemic Periods in a Subtropical City. PLoS One. 2015 Apr 30;10(4):e0125447. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2015 Jul 20;10(7):e0133946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133946. [CrossRef]

- Roberts MG, Hickson RI, McCaw JM, Talarmain L. A simple influenza model with complicated dynamics. J Math Biol. 2019 Feb;78(3):607-624. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría de Salud, Subsecretaría de Prevención y Promoción de la Salud. Lineamiento Estandarizado para la Vigilancia Epidemiológica y por Laboratorio de la Enfermedad Respiratoria Viral. Dirección General de Epidemiología, 2023, p. 34. Available at: https://epidemiologia.salud.gob.mx/gobmx/salud/documentos/manuales/12_Manual_VE_Influenza.pdf.

- Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos. (2015). Lineamientos para la vigilancia de Influenza por laboratorio (Versión 1). Secretaría de Salud. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/20769/lineamientos_para_la_vigilancia_de_influenza.pdf.

- Instituto de Diagnóstico y Referencia Epidemiológicos. (2024). Lineamientos para la vigilancia por laboratorio de virus respiratorios (Versión 2). Secretaría de Salud. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/884541/LVL_Virus_respiratorios_190124.pdf.

- Lavoie PM, Reicherz F, Solimano A, Langley JM. Potential resurgence of respiratory syncytial virus in Canada. CMAJ. 2021 Jul 26;193(29):E1140-E1141. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Q, Hu J, Hu W, Li H, Lin GZ. Interrupted time series analysis using the ARIMA model of the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence rate of notifiable communicable diseases in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2023 Jun 5;23(1):375. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Yuan F, Fan S, Tian J, Yang J. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on reported notifiable infectious diseases in China: An interrupted time series analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2024 Oct 23:S0196-6553(24)00763-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Gu L. Resurgence of seasonal influenza driven by A/H3N2 and B/Victoria in succession during the 2023-2024 season in Beijing showing increased population susceptibility. J Med Virol. 2024 Jun;96(6):e29751. [CrossRef]

- Fossum E, Rohringer A, Aune T, Rydland KM, Bragstad K, Hungnes O. Antigenic drift and immunity gap explain reduction in protective responses against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and A(H3N2) viruses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of human sera collected in 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2023. Virol J. 2024 Mar 6;21(1):57. Erratum in: Virol J. 2024 Mar 18;21(1):66. [CrossRef]

- Koutsakos M, Wheatley AK, Laurie K, Kent SJ, Rockman S. Influenza lineage extinction during the COVID-19 pandemic? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021 Dec;19(12):741-742. [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran V, Sullivan S, Edwards KM, Xie R, Khvorov A, Valkenburg SA, Cowling BJ, Barr IG. Human seasonal influenza under COVID-19 and the potential consequences of influenza lineage elimination. Nat Commun. 2022 Mar 31;13(1):1721. [CrossRef]

- Chow EJ, Uyeki TM, Chu HY. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat Rev Microbiol [Internet]. 2022 Oct 17 [cited 2024 Nov 17]; Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-022-00807-9.

- Munro AP, House T. Cycles of susceptibility: Immunity debt explains altered infectious disease dynamics post -pandemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Oct 11:ciae493. [CrossRef]

- Lee PI, Hsueh PR, Chuang JH, Liu MT. Changing epidemic patterns of infectious diseases during and after COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2024 Oct;57(5):685-690. [CrossRef]

- Leung C, Konya L, Su L. Postpandemic immunity debt of influenza in the USA and England: an interrupted time series study. Public Health. 2024 Feb;227:239-242. [CrossRef]

- Principi N, Autore G, Ramundo G, Esposito S. Epidemiology of Respiratory Infections during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses. 2023 May 13;15(5):1160. [CrossRef]

- Petros BA, Milliren CE, Sabeti PC, Ozonoff A. Increased Pediatric Respiratory Syncytial Virus Case Counts Following the Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Can Be Attributed to Changes in Testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2024 Jun 14;78(6):1707-1717. [CrossRef]

- Alhumaid S, Alabdulqader M, Al Dossary N, Al Alawi Z, Alnaim AA, Al Mutared KM, Al Noaim K, Al Ghamdi MA, Albahrani SJ, Alahmari AA, Al Hajji Mohammed SM, Almatawah YA, Bayameen OM, Alismaeel AA, Alzamil SK, Alturki SA, Albrahim ZR, Al Bagshi NA, Alshawareb HY, Alhudar JA, Algurairy QA, Alghadeer SM, Alhadab HA, Aljubran TN, Alabdulaly YA, Al Mutair A, Rabaan AA. Global Coinfections with Bacteria, Fungi, and Respiratory Viruses in Children with SARS-CoV-2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022 Nov 15;7(11):380. [CrossRef]

- Weidmann MD, Green DA, Berry GJ, Wu F. Assessing respiratory viral exclusion and affinity interactions through co-infection incidence in a pediatric population during the 2022 resurgence of influenza and RSV. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023 Jun 14;13:1208235. [CrossRef]

| Before pandemic | After pandemic | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cases (N) | (%) | Annual mean | cases (N) | (%) | Annual mean | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 1106 | 53.20 | 272 | 4022 | 55.75 | 800.8 | 0.036 | |

| Male | 973 | 46.80 | 240.25 | 3192 | 44.25 | 635.8 | ||

| Age group | ||||||||

| 0-2 | 758 | 36.46 | 187.25 | 1691 | 23.44 | 336.6 | <0.001 | |

| 3-5 | 199 | 9.57 | 48 | 460 | 6.38 | 90.8 | ||

| 6-14 | 150 | 7.22 | 36.25 | 780 | 10.81 | 154.8 | ||

| 15-65 | 757 | 36.41 | 188 | 3825 | 53.02 | 763.4 | ||

| >65 | 215 | 10.34 | 52.75 | 458 | 6.35 | 91 | ||

| Variable | Total of positive tests (n=9,283) |

Total of positive tests in men (n=4,165) |

Total of positive tests in women (n= 5,128) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age – median, (IQR) | 22.0 (IQR 2.0-38.0) | 16.0 (IQR 1.0-36.0) | 24.0 (IQR 3.0-39.0) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities - n, (%) | 2808 (30.25) | 1250 (30.10) | 1558 (30.38) | 0.651 |

| Asthma - n, (%) | 598.0 (6.44) | 212.0 (5.10) | 386.0 (7.53) | <0.001 |

| COPD - n, (%) | 390.0 (4.20) | 155.0 (3.73) | 235.0 (4.58) | 0.041 |

| Smoking - n, (%) | 624.0 (6.72) | 374.0 (9.01) | 250.0 (4.88) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes - n, (%) | 605.0 (6.52) | 261.0 (6.28) | 344.0 (6.71) | 0.392 |

| Hypertension - n, (%) | 816.0 (8.79) | 348.0 (8.38) | 468.0 (9.13) | 0.188 |

| Cardiovascular disease - n, (%) | 245.0 (2.64) | 123.0 (2.96) | 122.0 (2.38) | 0.104 |

| Chronic kidney disease - n, (%) | 177.0 (1.91) | 96.0 (2.31) | 81.0 (1.58) | 0.014 |

| Obesity - n, (%) | 652.0 (7.02) | 278.0 (6.69) | 374.0 (7.29) | 0.245 |

| Immunosuppression - n, (%) | 365.0 (3.93) | 222.0 (5.35) | 143.0 (2.79) | <0.001 |

| HIV infection - n, (%) | 86.0 (0.93) | 58.0 (1.40) | 28.0 (0.55) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy - n, (%) | 186.0 (2.00) | - | 186.0 (3.63) | - |

| Virus - n, (%) | Total of positive tests (n=9,283) |

Total of positive tests in men (n=4,165) |

Total of positive tests in women (n= 5,128) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza virus* | 5325.0 (9.28) | 2198.0 (3.83) | 3127.0 (5.45) | <0.001 |

| Influenza A | 3677.0 (69.05) | 1528.0 (36.79) | 2149.0 (42.15) | 0.569 |

| Influenza A H3 | 2968.0 (55.73) | 1208.0 (29.09) | 1760.0 (34.52) | 0.346 |

| Influenza A H1N1 | 326.0 (6.12) | 169.0 (4.07) | 157.0 (3.08) | <0.001 |

| Influenza A nonsubtyped | 387.0 (7.27) | 153.0 (3.68) | 234.0 (4.59) | 0.501 |

| Influenza B | 1647.0 (30.93) | 670.0 (16.13) | 977.0 (19.16) | 0.569 |

| Influenza B Victoria lineage | 1511.0 (28.38) | 611.0 (14.71) | 900.0 (17.65) | 0.447 |

| Influenza B Yamagata lineage | 105.0 (1.97) | 43.0 (1.04) | 62.0 (1.22) | 1 |

| Influenza B nonsubtyped | 32.0 (0.60) | 17.0 (0.41) | 15.0 (0.29) | 0.236 |

| Other respiratory viruses* | 3958.0 (22.94) | 1967.0 (11.40) | 2001.0 (11.59) | 0.177 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | 1534.0 (38.76) | 760.0 (18.30) | 774.0 (15.18) | 0.924 |

| Human enterovirus/rhinovirus | 1458.0 (36.84) | 719.0 (17.31) | 739.0 (14.49) | 0.756 |

| Human metapneumovirus | 485.0 (12.25) | 222.0 (5.35) | 263.0 (5.16) | 0.074 |

| Human parainfluenza virus 1 | 76.0 (1.92) | 48.0 (1.16) | 28.0 (0.55) | 0.024 |

| Human parainfluenza virus 2 | 86.0 (2.17) | 74.0 (1.78) | 12.0 (0.24) | <0.0010 |

| Human parainfluenza virus 3 | 167.0 (4.22) | 95.0 (2.29) | 72.0 (1.41) | 0.068 |

| Human parainfluenza virus 4 | 46.0 (1.16) | 25.0 (0.60) | 21.0 (0.41) | 0.624 |

| Human adenovirus | 366.0 (9.25) | 150.0 (3.61) | 216.0 (4.24) | 0.001 |

| Human coronavirus 229E | 71.0 (1.79) | 28.0 (0.67) | 43.0 (0.84) | 0.105 |

| Human coronavirus OC43 | 104.0 (2.63) | 42.0 (1.01) | 62.0 (1.22) | 0.069 |

| Human coronavirus HKU1 | 42.0 (1.06) | 21.0 (0.51) | 21.0 (0.41) | <0.0011 |

| Human coronavirus NL63 | 59.0 (1.49) | 32.0 (0.77) | 27.0 (0.53) | 0.565 |

| Human bocavirus | 58.0 (1.47) | 36.0 (0.87) | 22.0 (0.43) | 0.077 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).