1. Introduction

Viral bronchiolitis is an acute respiratory illness that is the leading cause of hospitalization in young children; it represents the most common cause of acute respiratory failure in infants under one year of age in developing countries. 1

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) accounts for 60–80% of bronchiolitis presentations. It has been estimated that RSV infects more than 60% of all children during the first year of life and that RSV infects nearly all children by the time they are two years old. 2,3 RSV is the second cause of death worldwide after malaria and the first cause of death for respiratory illness. 4,5

The clinical presentation of RSV infections is highly variable. It may be limited to upper respiratory tract symptoms, such as fever, rhinorrhoea, and congestion; the severe presentation includes bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Bronchiolitis is generally self-limiting but can lead to hospitalization due to severe respiratory distress, acute respiratory failure or difficulty feeding. The main risk factors for severe disease are: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, age younger than 12 months, personal history of prematurity, male sex, immunodeficiency, formula feeding and congenital heart disease.

The primary preventive measure used is prophylaxis with Palivizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against RSV; this is used to defence against severe manifestations of respiratory infections due to RSV in high-risk patients. 6

RSV is characterized by a variable epidemiology, depending on geographic area. In Italy, the RSV circulates from mild November until the end of March, peaking in January/February; the total circulation duration is about four months. 7

Nevertheless, RSV circulation in the past has been influenced by previous Pandemics; for instance, influenza H1N1 in 2009, delaying the RSV peak; this variability of seasonality could be explained by possible viral interference, and the impact of preventive measures. 8

During the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic various restrictive measures were adopted worldwide, like activation of social distancing measures, closing of schools and commercial activities, strict hygiene behaviours, use of face masks and travels limitations. The massive effort to contain the spread of SARS-CoV2, also affected the circulation of respiratory pathogens, like influenza and RSV, with a similar transmission route (contact, droplets and aerosol transmission). 9

Especially, during the 2020-2021 season, few cases of bronchiolitis were reported worldwide, leading some authors to speak about “a nearly absent disease”. 10 In the 2021-2022 season a dramatic rebound of bronchiolitis was reported in the Northern and Southern hemispheres, due to RSV infections. 10 This data in Italy was detected by the Influenza Surveillance Network (InfluNet) system. 7

The first report of bronchiolitis decreased was in Australia and New Zealand, where the containment of SARS-CoV2 was excellent and quickly started to relax the SARS-CoV-2 preventive measures.

After, an unexpected unseasonal peak of bronchiolitis compared to pre-Pandemic periods has been registered worldwide. 11–13 This data was confirmed by intercontinental reports; it shows an anticipation of the peak of bronchiolitis, due to RSV. Also in Italy the data has been confirmed. 14–17

Our study aims to provide insights into the impact of the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic on the epidemiology of RSV infections in Spoke hospitals of our health district (ASL TO4). The secondary aim was to evaluate the differences in the clinical features of patients affected by RSV before and after the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic and the global increase of bronchiolitis due to RSV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A retrospective study was carried out in Spoke hospitals of ASLTO4. Our local health district (ASLTO4), in the north-west of Italy, includes 174 cities; the overall area is characterized by a great geographical variability, from high Alpine Mountains to urban areas. Total population of this area is 504467 people, with 3015 inhabitants under one year of age in 2022.18 The healthcare system is organized into five districts, with a great heterogeneity in demography, population density and infrastructures. General Emergency Department and Pediatric Unit are present in three Spoke hospitals of Ciriè, Chivasso and Ivrea.

We included patients under one year of age referred to our Pediatric Departments for acute bronchiolitis due to RSV requiring hospitalization over different seasons.

We divided the included patients into two groups: Group A hospitalized before the SARS-Cov2 Pandemic (from September 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018; from September 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019; from September 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020) and a Group B hospitalized after the period of Pandemic (from September 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022 and from September 1, 2022 to March 31, 2023). We also reported the total number of cases of bronchiolitis hospitalized in the same periods and the few cases of bronchiolitis in the Pandemic period (from September 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021).

We collected data about demographic variables (sex, age, months of admission). Clinical and epidemiological data were recorded (age at onset, gestational age and birth weight, weight at admission, feeding, fever) as well as personal history of chronic illnesses such as cardiopathy, neurological disease and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Relevant clinical variables were documented like laboratory (C-reactive protein and Pco2), microbiology (coinfection by other microbiological agents) and radiograph results and short-term outcomes (length of hospital stay, complications, Hub hospital transfer). Treatment during hospitalization (low or high-flow oxygen supplementation, nebulized therapy, steroids, antibiotics and intravenous hydration) and discharged therapy data were recorded in all patients.

Firstly, the temporal trend of RSV bronchiolitis after the SARS-COV2 Pandemic (Group B) was compared to those of the previous period (Group A).

Then, clinical and epidemiological characteristics were compared to study if there were differences in the patients affected, in the severity of the infections and in the short-term outcomes.

Finally, we analysed the RSV prevalence in global bronchiolitis hospitalization in the same periods, both over-reported and during the Pandemic.

The study was conducted in full conformance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In accordance with current legislation, this research is not among the types that require a formal opinion from the ethics committee. This a secondary use of data for research purposes for which a specific informed consent was requested ab initio from patients who would undertake a treatment process.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Univariate analysis was performed with the Chi-square or Fisher’s test for dichotomous variables while for continuous variables the Kruskal-Wallis test for nonparametric measures was used. 19 The Kaplan-Meier statistics were used to define probability of success.20 The difference between groups was calculated by a log-rank test.21

The univariate analysis was conducted by VassarStats (Statistical Computation Web Site), while the Kaplan-Meier statistics were performed by the NCSS software for Windows (

https://www.ncss.com/). A P-value below 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

3. Results

Overall, 237 patients were enrolled in the study: 109 in Group A and 128 in Group B.

3.1. Seasonality

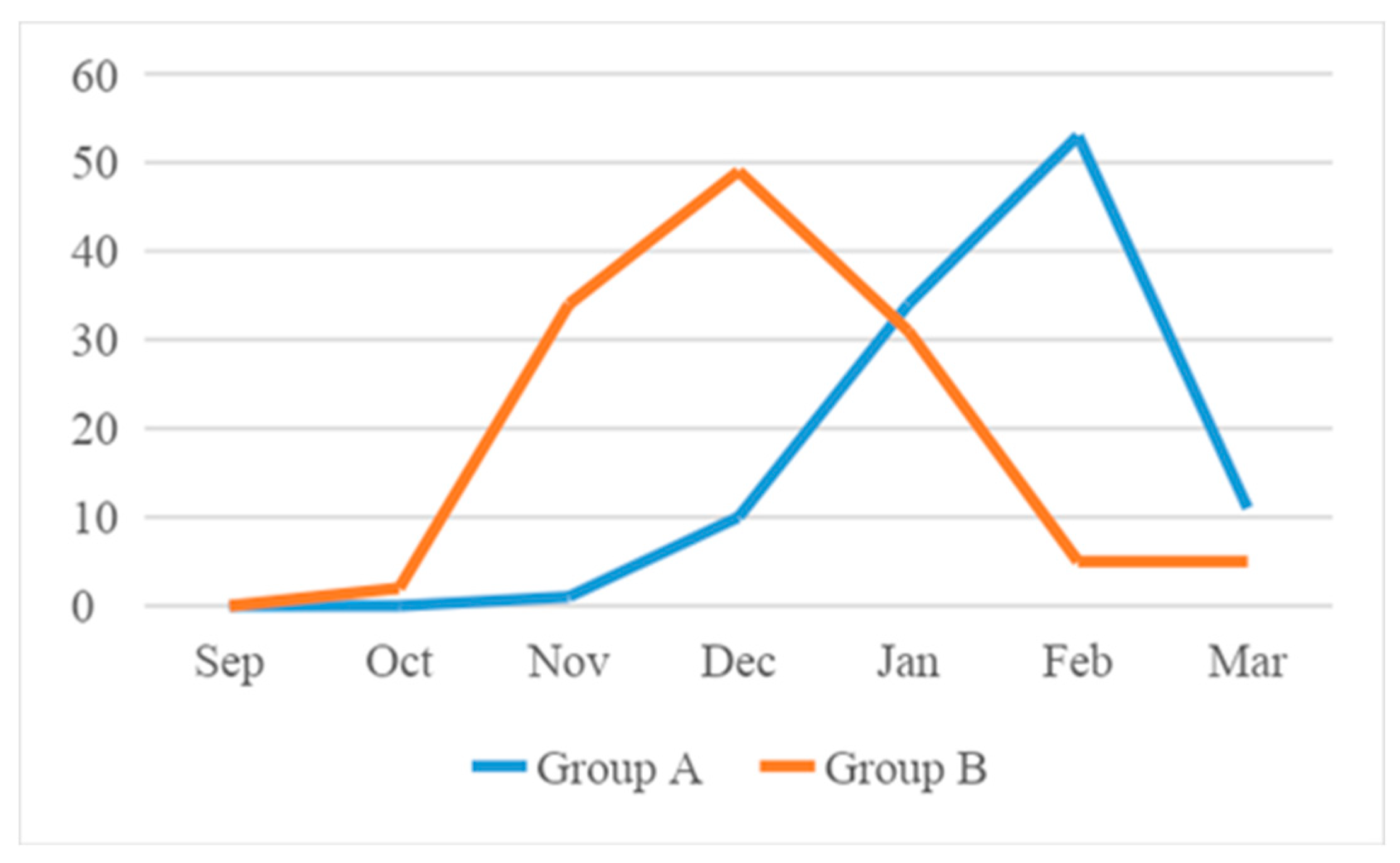

Hospitalization for RSV bronchiolitis follows a distinct seasonal trend in the two groups, as shown in

Figure 1.

In the Group A, in the period before the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic, the peaks in admissions occurred between November and March, usually lasting 2-4 months. Cases increased significantly in December and peaked in January and February, with only few cases in March.

Otherwise, in Group B, after the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic, an anticipated peak was reported. Indeed, bronchiolitis started slowly in October, peaked in November and December and slowly decreased during February and March.

The distribution of hospitalization month by month is summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients

The demography and clinical characteristics of patients are resumed in

Table 2.

In Group A, males were more represented than females (51% vs 49%); gestational age was reported in 98% of patients. Preterm infants accounted for about 11%; half of patients had a gestational age between 30 and 34 weeks and the remaining patients had a gestational age between 35 and 36 weeks. In this group no patient had a gestational age under 30 weeks. Two patients had bronchopulmonary dysplasia, two infants had chronic heart conditions, one had a neurological disease like epilepsy and no immunodeficiency was recorded. At the diagnosis, most patients (48%) had an age between one and three months while 34% of them were under one month; then 13% had an age between four and six months and 5% of them were over six months of age. Breastfeeding was reported in 58% of all patients, while formula feeding was reported in 34% of all and 6% of infants had already been weaned.

In Group B, more males than females (61% vs 39%) were represented, and the gestational age was reported in 95% of patients. Among these, preterm infants are calculated to be 12% of all; most of all (67%) had a gestational age between 35 and 36 weeks, while 27% of them had a gestational age between 30 and 34 weeks and only one infant had a gestational age of 25 weeks. Two patients had bronchopulmonary dysplasia, one infant had a neurological disease with hypotonia, and no immunodeficiency and chronic heart conditions were recorded. When hospitalized, most patients (48%) were newborns under one month of age, while the 23% had an age between one and three months and the 17% between four and six months. 11% of infants were over six months old. Breastfeeding was reported in 66% of all patients, while formula was reported feeding in 20% of all, and 10% of infants had already been weaned.

The description of patients involved in the study shows a remarkable difference in the age of the infants; in Group B, there are more newborns. No statistically differences in sex, gestational age, feeding, and comorbidity are recorded.

Concerning prophylaxis with Palivizumab, only one patient in Group B was hospitalized for Bronchiolitis due to RSV; he was born at 31 weeks of gestational age needed Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) at birth and presented pneumothorax. During the hospitalization for bronchiolitis, he didn’t need oxygen supplementation and was admitted in the hospital for three days.

Laboratory, X-ray findings and treatment during hospitalization are resumed in

Table 3.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in X ray findings, while there was a remarkable difference in CRP values.

Concerning the treatment, some differences are remarkable. Antibiotics and IV Hydration are less used in Group B; in Group A, 38% received an antibiotic therapy compared to the 19% of patients in Group B. Similarly, in Group B, only 18% of patients were treated with IV hydration (vs the 29% in the Group A).

There were no statistically significant differences in the type of respiratory support and length of respiratory supports in days.

Finally, concerning the short-term outcome, the complications, the length of hospital stay and the need to transfer to a Hub hospital are similar in the two groups. These data are resumed in

Table 4.

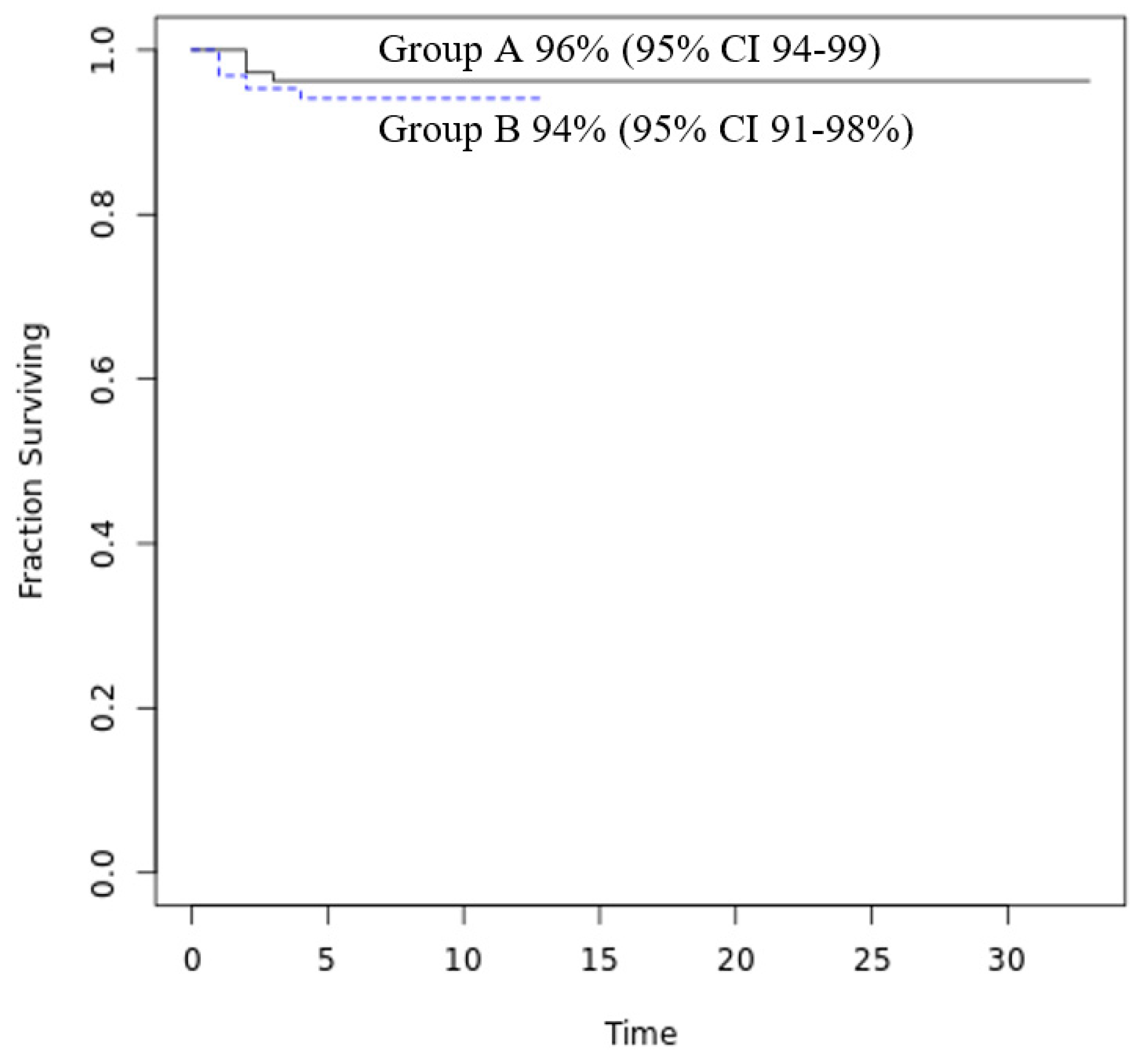

Figure 2 reports the probability of treatment success (discharge to home without transfer to a Hub hospital with PICU or NICU): 96% of patients in Group A and 94% in Group B.

Table 4.

Short-term outcome.

Table 4.

Short-term outcome.

| Complications |

Yes |

12 (11%) |

12 (9%) |

0.82 |

| |

No |

97 (89%) |

116 (91%) |

|

| Hospitalization (days) |

|

6 (2-33) |

5 (1-13) |

0.051 |

| Transfer to a Hub hospital |

Yes |

4 (4%) |

7 (5%) |

0.55 |

| |

No |

105 (96%) |

121 (94%) |

|

3.3. RSV Prevalence

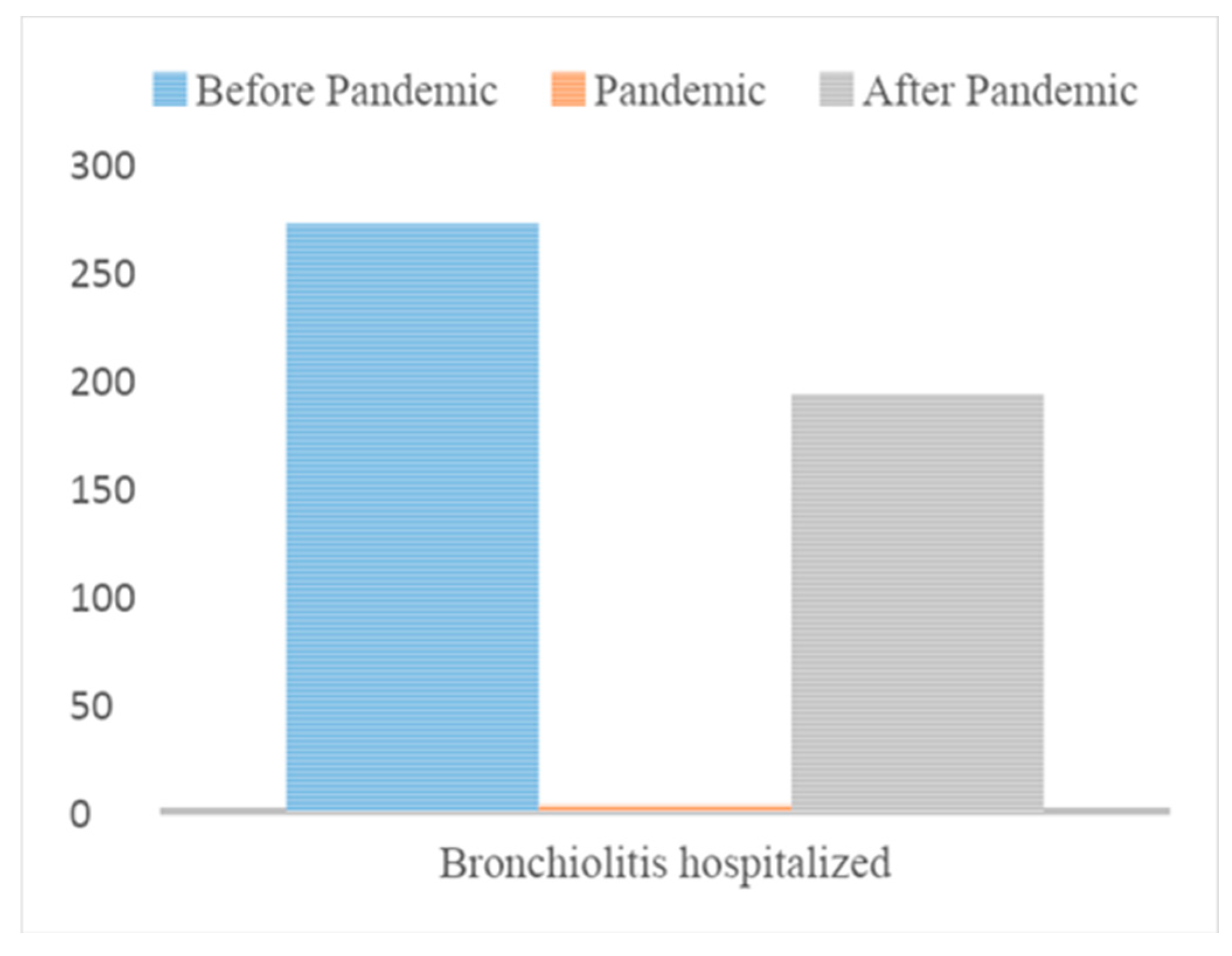

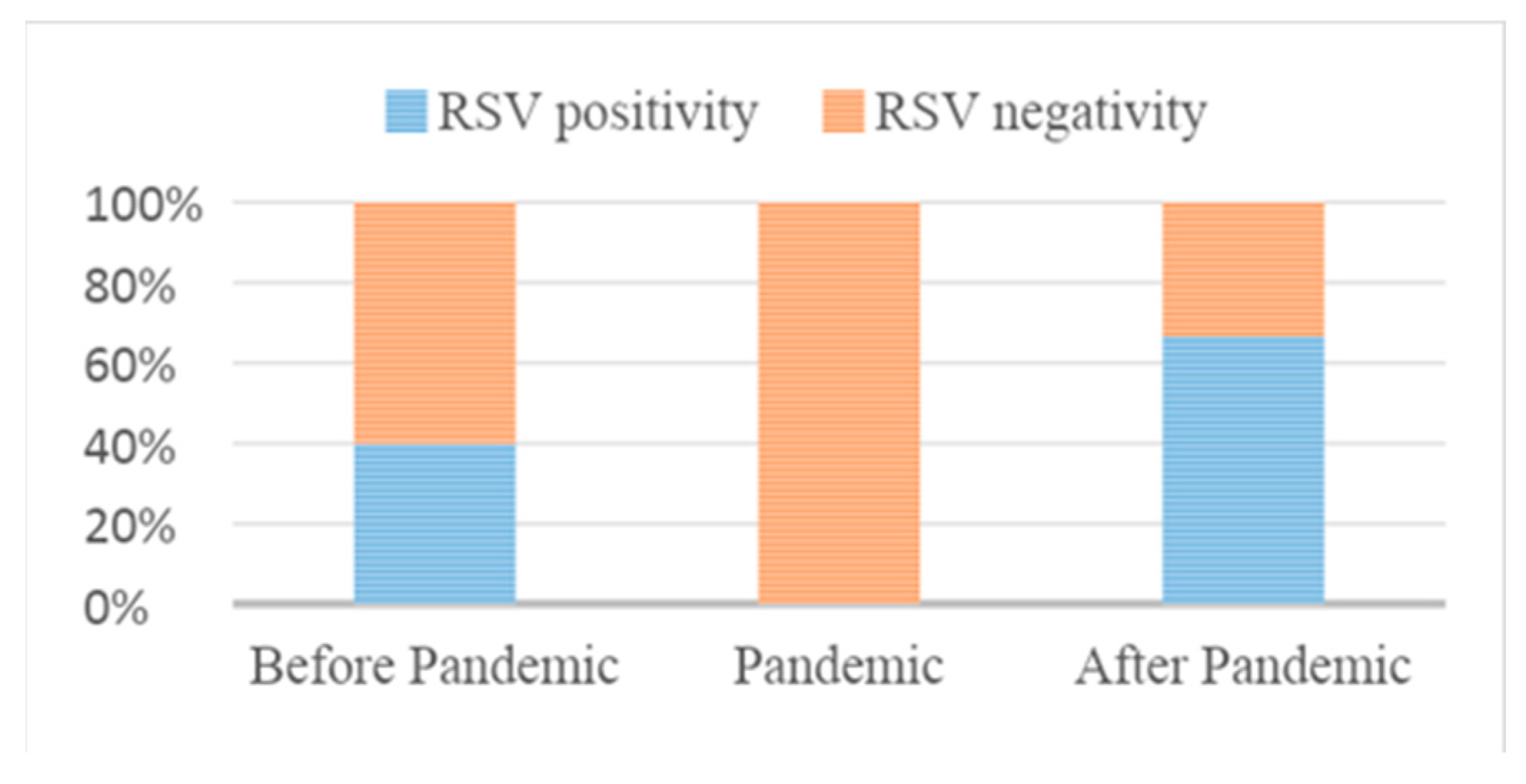

In the period before the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic (from September 1, 2017 to March 31, 2018; from September 1, 2018 to March 31, 2019; from September 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020) in the three ASLTO4 Pediatric Departments 272 patients were hospitalized with diagnosis of bronchiolitis; in 109 (40%) of them, RSV (Group A) was detected on nasal swab.

During the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic (from September 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021), when restrictive measures were adopted, 3 patients were hospitalized for bronchiolitis and RSV wasn’t detected.

After the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic (from September 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022 and from September 1, 2022 to March 31, 2023), the total number of hospitalizations for bronchiolitis was 193. In 128 cases (66%), the detected agent was RSV (Group B).

Therefore, we can demonstrate a significant increase in the prevalence of RSV after the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic; moreover, we notice a significant drop in cases of bronchiolitis but, above all, the complete absence of RSV infection in the Pandemic period.

Table 4.

Cases of RSV infections in patients hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

Table 4.

Cases of RSV infections in patients hospitalized for bronchiolitis.

| |

2017-2020 |

2021-2023 |

P value |

| RSV positive |

109 (40%) |

128 (66%) |

<0.0001 |

| RSV negative |

163 (60%) |

65 (34%) |

4. Discussion

Our study analyses the characteristics of infants hospitalized for acute RSV bronchiolitis in the three Pediatric Departments of ASLTO4 before, during and after the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic.

Our data highlight that after the Pandemic, the RSV epidemic started earlier than usual. We showed a peak in November-December in Group B, while in Group A, the peak was in January-February. This confirms new epidemiological trends of RSV infection as reported worldwide. 16,22–25

The surveillance of the seasonality of RSV is very important for the improvement and the adaptation of the prevention measures. The logistics and timing are very important to optimize its prevention results; if the prophylaxis begins months before the RSV season, the protection could wane before the end of the epidemic, leaving infants susceptible to RSV. Similarly, if the RSV season starts earlier than the prophylaxis, high-risk infants remain vulnerable. Considering the new epidemiological trends, in Piedmont, prophylaxis with Palivizumab in high-risk patients begins in October, starting from 2022, providing the first dose before the onset of the circulation of RSV. This highlights the importance of improving and updating the system of local surveillance, that in Italy started in 2019-2020 on the Influenza Surveillance Network (InfluNet) system.

In accordance with the current literature, no differences in the severity of RSV infection have been demonstrated in our study; no differences in X-ray findings, short-term outcomes (like complications, length of hospitalization, type of respiratory support, length of oxygen supplementation and need of transfer to Hub hospital) have been reported. 26–28 The only remarkable difference is in the value of CRP value; in group A, the average value was higher than in the Group B.

Interestingly, we show remarkable differences in treatment; fewer antibiotics are used in Group B. This suggests better adherence to the guidelines making an important effort to reduce the creation of antibiotic resistance. Also, the higher CRP value in the Group A, may explain the larger use of antibiotics in this group of patients; clinicians had more suspicion of bacterial complications so they prescribed antibiotics. Lastly, reducing IV hydration over the years, the patients were encouraged to maintain oral feeding with a higher number of fractionated meals. 3

Looking to the RSV prevalence, during the SARS-CoV2, we had a drop in bronchiolitis hospitalizations. We reported 3 patients hospitalized for bronchiolitis and no cases of RSV infections. This data is in agreement with other studies and epidemiological surveillance, showing a global reduction in respiratory infections that share the transmission path with SARS-CoV2, like Influenza and RSV. 24,29 Given that transmission of RSV occurs through droplets, the containment measures of the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic (like the use of face masks, social distancing, smart working, and closure of schools) have led to the reduction of RSV transmission. 9,30,31

Moreover, there is a strong correlation with environmental conditions, both weather and air pollution, and the incidence of RSV. A study shows a correlation between RSV transmission, benzene levels and humidity, while there is an inverse correlation with temperature. 32 Given that a significant reduction in air pollutants such as benzene was recorded during the Pandemic, it can be hypothesized that the reduction in pollution helped to decrease the circulation of RSV. It’s very hard to quantify the contribution, but we can suggest that it is not comparable with restrictive measures. We aim to explore such hypothesis by further studies.

The prevalence of RSV in our data increased significantly after the SARS-CoV2 Pandemic, confirming previous data published; we reported an RSV surge when the prevention measures were relaxed, and the social interactions increased. This confirms the main role of these measures in the contention of RSV circulation.

Furthermore, the “immunity debt” played a role in the increased circulation: during the Pandemic period, a cohort of RSV-naïve patients expanded, both due to the presence of children who have never had RSV infections and to the reduction in immunity duration, which decreased during the time and without re-exposure to RSV. This is confirmed by studies that show an increased number of holder infants affected by RSV. 32 In our study there is a remarkable difference in newborns hospitalized for RSV bronchiolitis pre and post Pandemic; we report 48% of newborns in Group B vs 34% of newborns in Group A. We can explain this result with a reduced exposition to respiratory viruses also in pregnant women; above all, the infection in the third trimester of pregnancy, could protect newborns against RSV infections through antibodies contained in breast milk and those transferred transplacental. 33–35

Our study has some limitations. Our analysis is conducted in Hub hospitals with a small sample size and based on a retrospective data collection of hospital records; so this study may be subject to information bias due to the lack of data or incomplete hospital records. In addition, we only reported data about hospitalized patient with bronchiolitis, while patients who visited the Emergency Department and were discharged or treated by general pediatric practitioners weren’t included. Consequently, global prevalence and incidence of RSV may be underestimated.

The main strength of our study is that it is performed in three Spoke hospitals which are part of the same health district (ASL); therefore, clinicians have the same devices for the treatment of respiratory failure and the same tests to detect RSV, share the protocols of treatment and have the same criteria of transfer to Hub hospital because of the lack of Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

5. Conclusions

The SARS-CoV2 Pandemic has changed the epidemiological trend of RSV infections. In details, the bronchiolitis season started earlier than usual after Pandemic; this is reported in our study according to data records from other countries. The unusual resurgence of RSV infection was not associated with an increased severity of the illness in our study group. In addition, we reported an increase in the prevalence of RSV bronchiolitis hospitalized after the Pandemic, with high proportion of newborns possibly due to the “immunity debt” and the lower exposition in pregnant women.

The surveillance of circulation of the respiratory virus is necessary to adapt the preventive measures and hospital activity organization to the seasonal changes; indeed, the analysis of changes in seasonality allows the high-risk patients to receive the optimal level of prevention with a correct prophylaxis while hospitals reorganize the activity. It may also imply transferring patients from the Hub to the Spoke hospitals, leading to a remarkable contention of costs. Lastly, a lesson learned during the Pandemic period shows us that simple preventive measures should not be forgotten, because they can markedly reduce RSV circulation; this underlines how important are strict hygiene behaviours and the utilisation of face masks by healthcare workers, above all who deal with high-risk patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In accordance with current legislation, this research is not among the types that require a formal opinion from the ethics committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The collected data are available from corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meissner HC. Viral Bronchiolitis in Children. Ingelfinger JR, ed. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):62-72. [CrossRef]

- Perez A, Lively JY, Curns A, et al. Respiratory Virus Surveillance Among Children with Acute Respiratory Illnesses — New Vaccine Surveillance Network, United States, 2016–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(40):1253-1259. [CrossRef]

- Manti S, Staiano A, Orfeo L, et al. UPDATE - 2022 Italian guidelines on the management of bronchiolitis in infants. Ital J Pediatr. 2023;49(1):19. [CrossRef]

- Cutrera R, Wolfler A, Picone S, et al. Impact of the 2014 American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation and of the resulting limited financial coverage by the Italian Medicines Agency for palivizumab prophylaxis on the RSV-associated hospitalizations in preterm infants during the 2016–2017 epidemic season: a systematic review of seven Italian reports. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):139. [CrossRef]

- Mazur NI, Martinón-Torres F, Baraldi E, et al. Lower respiratory tract infection caused by respiratory syncytial virus: current management and new therapeutics. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(11):888-900. [CrossRef]

- Viguria N, Navascués A, Juanbeltz R, Echeverría A, Ezpeleta C, Castilla J. Effectiveness of palivizumab in preventing respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk children. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(6):1867-1872. [CrossRef]

- Azzari C, Baraldi E, Bonanni P, et al. Epidemiology and prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections in children in Italy. Ital J Pediatr. 2021;47(1):198. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang X, Msosa T, De Wit F, Murdock J, Nair H. The impact of the 2009 influenza pandemic on the seasonality of human respiratory syncytial virus: A systematic analysis. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15(6):804-812. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento MS, Baggio DM, Fascina LP, Do Prado C. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on the seasonality of pediatric respiratory diseases. Morrow BM, ed. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0243694. [CrossRef]

- Van Brusselen D, De Troeyer K, Ter Haar E, et al. Bronchiolitis in COVID-19 times: a nearly absent disease? Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180(6):1969-1973. [CrossRef]

- Foley DA, Yeoh DK, Minney-Smith CA, et al. The Interseasonal Resurgence of Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Australian Children Following the Reduction of Coronavirus Disease 2019–Related Public Health Measures. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e2829-e2830. [CrossRef]

- Saravanos GL, Hu N, Homaira N, et al. RSV Epidemiology in Australia Before and During COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2022;149(2):e2021053537. [CrossRef]

- Public Health Surveillance Inforamtion for New Zealands Public Health Action. Laboratory-Based Virology Weekly Report, 2004–2019. 2021. Available online: https://surv.esr.cri.nz/virology/virology_weekly_report.php.

- Camporesi A, Morello R, Ferro V, et al. Epidemiology, Microbiology and Severity of Bronchiolitis in the First Post-Lockdown Cold Season in Three Different Geographical Areas in Italy: A Prospective, Observational Study. Children. 2022;9(4):491. [CrossRef]

- Tulyapronchote R, Selhorst JB, Malkoff MD, Gomez CR. Delayed sequelae of vertebral artery dissection and occult cervical fractures. Neurology. 1994;44(8):1397-1397. [CrossRef]

- Agha R, Avner JR. Delayed Seasonal RSV Surge Observed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021052089. [CrossRef]

- Guitart C, Bobillo-Perez S, Alejandre C, et al. Bronchiolitis, epidemiological changes during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):84. [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.ruparpiemonte.it/infostat/risultati.jsp.

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. [CrossRef]

- Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50(3):163-170.

- Kruskal WH, Wallis WA. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1952;47(260):583-621. [CrossRef]

- Curatola A, Graglia B, Ferretti S, et al. The acute bronchiolitis rebound in children after COVID-19 restrictions: a retrospective, observational analysis. Acta Biomed Atenei Parm. 2023;94(1):e2023031. [CrossRef]

- Pruccoli G, Castagno E, Raffaldi I, et al. The Importance of RSV Epidemiological Surveillance: A Multicenter Observational Study of RSV Infection during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses. 2023;15(2):280. [CrossRef]

- Olsen SJ, Winn AK, Budd AP, et al. Changes in Influenza and Other Respiratory Virus Activity During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(29):1013-1019. [CrossRef]

- Weinberger Opek M, Yeshayahu Y, Glatman-Freedman A, Kaufman Z, Sorek N, Brosh-Nissimov T. Delayed respiratory syncytial virus epidemic in children after relaxation of COVID-19 physical distancing measures, Ashdod, Israel, 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(29). [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez Barrezueta L, Gutiérrez Zamorano M, López-Casillas P, Brezmes-Raposo M, Sanz Fernández I, Pino Vázquez MDLA. Influencia de la pandemia COVID-19 sobre la epidemiología de la bronquiolitis aguda. Enfermedades Infecc Microbiol Clínica. 2023;41(6):348-351. [CrossRef]

- Shanahan KH, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Severity of Illness in Bronchiolitis Amid Unusual Seasonal Pattern During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Hosp Pediatr. 2022;12(4):e119-e123. [CrossRef]

- Correction to: Outbreak of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Bronchiolitis in Italy. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(4):777-779. [CrossRef]

- Nenna R, Matera L, Pierangeli A, et al. First COVID-19 lockdown resulted in most respiratory viruses disappearing among hospitalised children, with the exception of rhinoviruses. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111(7):1399-1403. [CrossRef]

- Ferrero F, Ossorio MF. Is there a place for bronchiolitis in the COVID-19 era? Lack of hospitalizations due to common respiratory viruses during the 2020 winter. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(7):2372-2373. [CrossRef]

- Wilder JL, Parsons CR, Growdon AS, Toomey SL, Mansbach JM. Pediatric Hospitalizations During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146(6):e2020005983. [CrossRef]

- Lumley SF, Richens N, Lees E, et al. Changes in paediatric respiratory infections at a UK teaching hospital 2016–2021; impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. J Infect. 2022;84(1):40-47. [CrossRef]

- Koivisto K, Nieminen T, Mejias A, et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV)–Specific Antibodies in Pregnant Women and Subsequent Risk of RSV Hospitalization in Young Infants. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(7):1189-1196. [CrossRef]

- Manti S, Leonardi S, Rezaee F, Harford TJ, Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Effects of Vertical Transmission of Respiratory Viruses to the Offspring. Front Immunol. 2022;13:853009. [CrossRef]

- Hatter L, Eathorne A, Hills T, Bruce P, Beasley R. Respiratory syncytial virus: paying the immunity debt with interest. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5(12):e44-e45. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).