Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. PDMS Foam Preparation

2.3. Solvent Extraction for Porous PDMS Samples

2.4. Rheology Characterization

2.5. Porosity Characterization

2.6. Mechanical Characterization

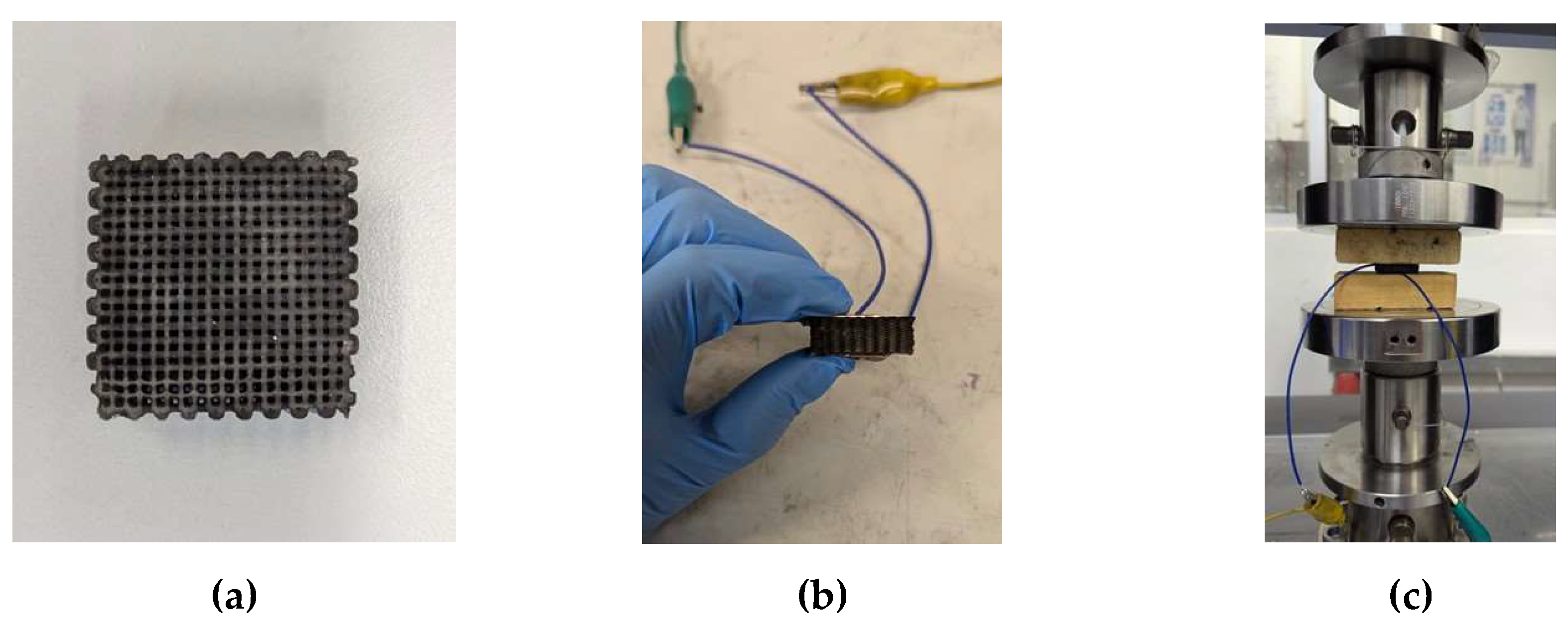

2.7. Piezoresistive Effect

3. Results and Discussion

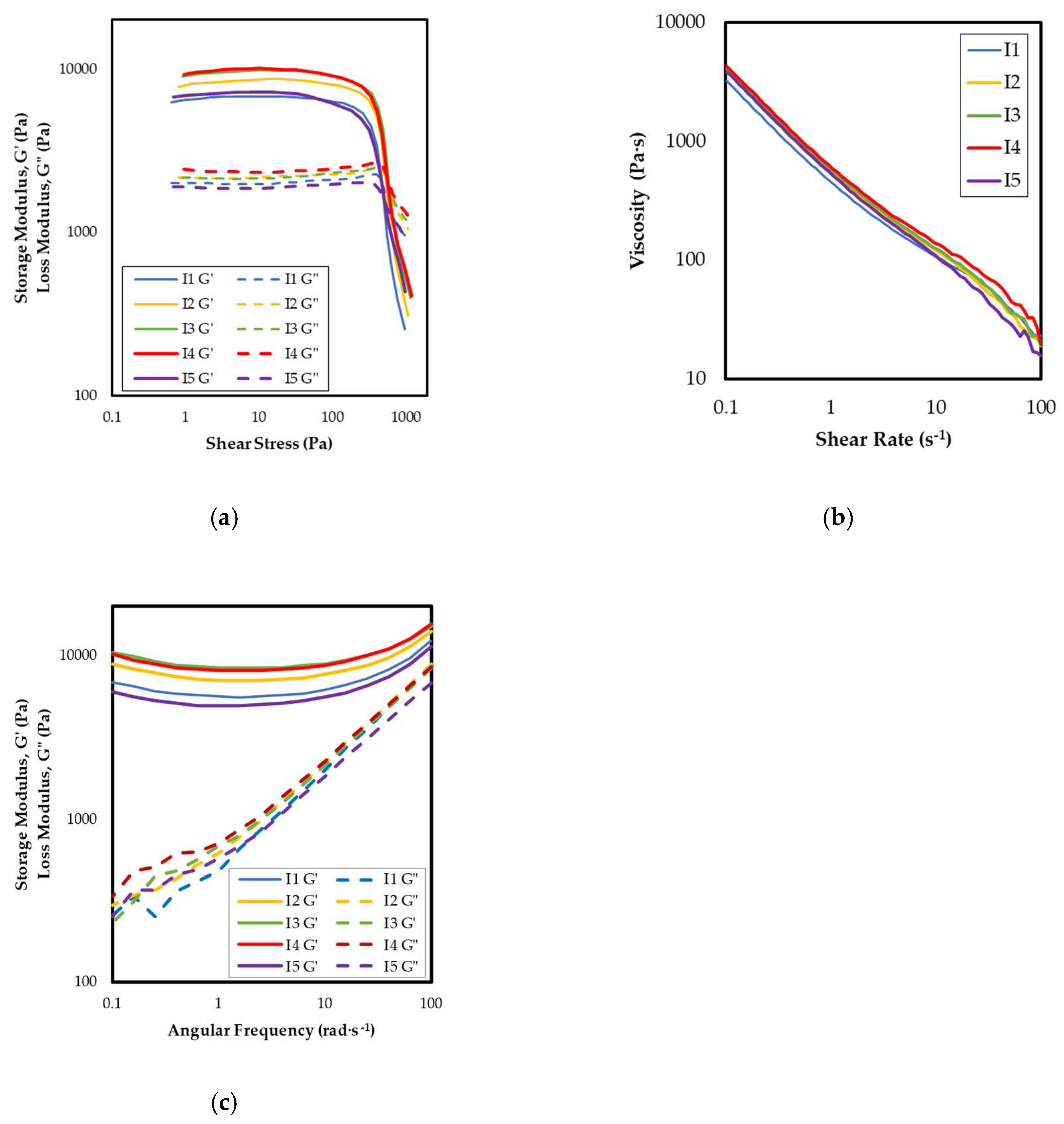

3.1. Rheology

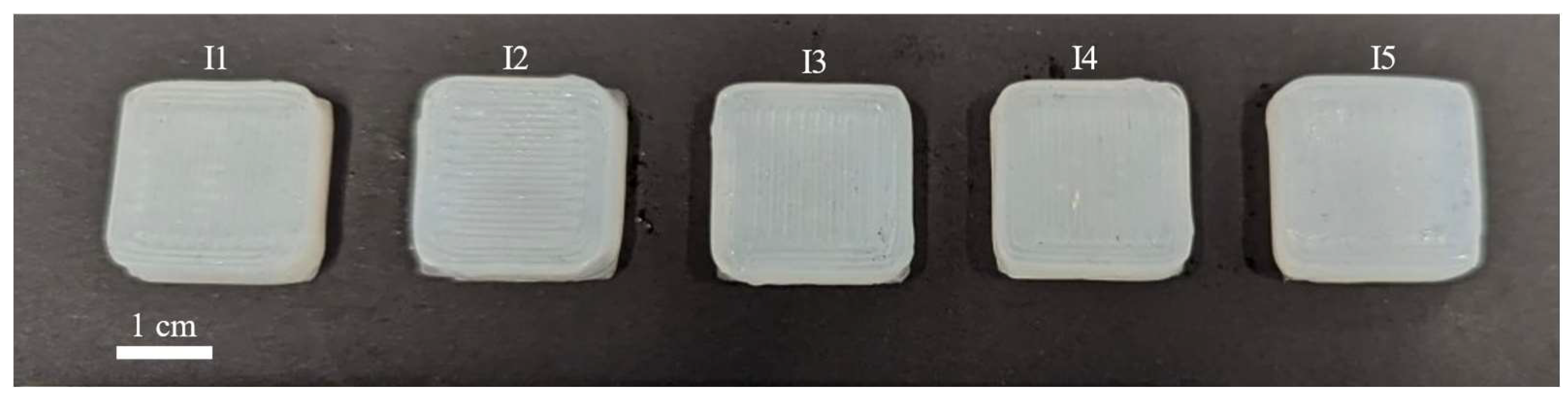

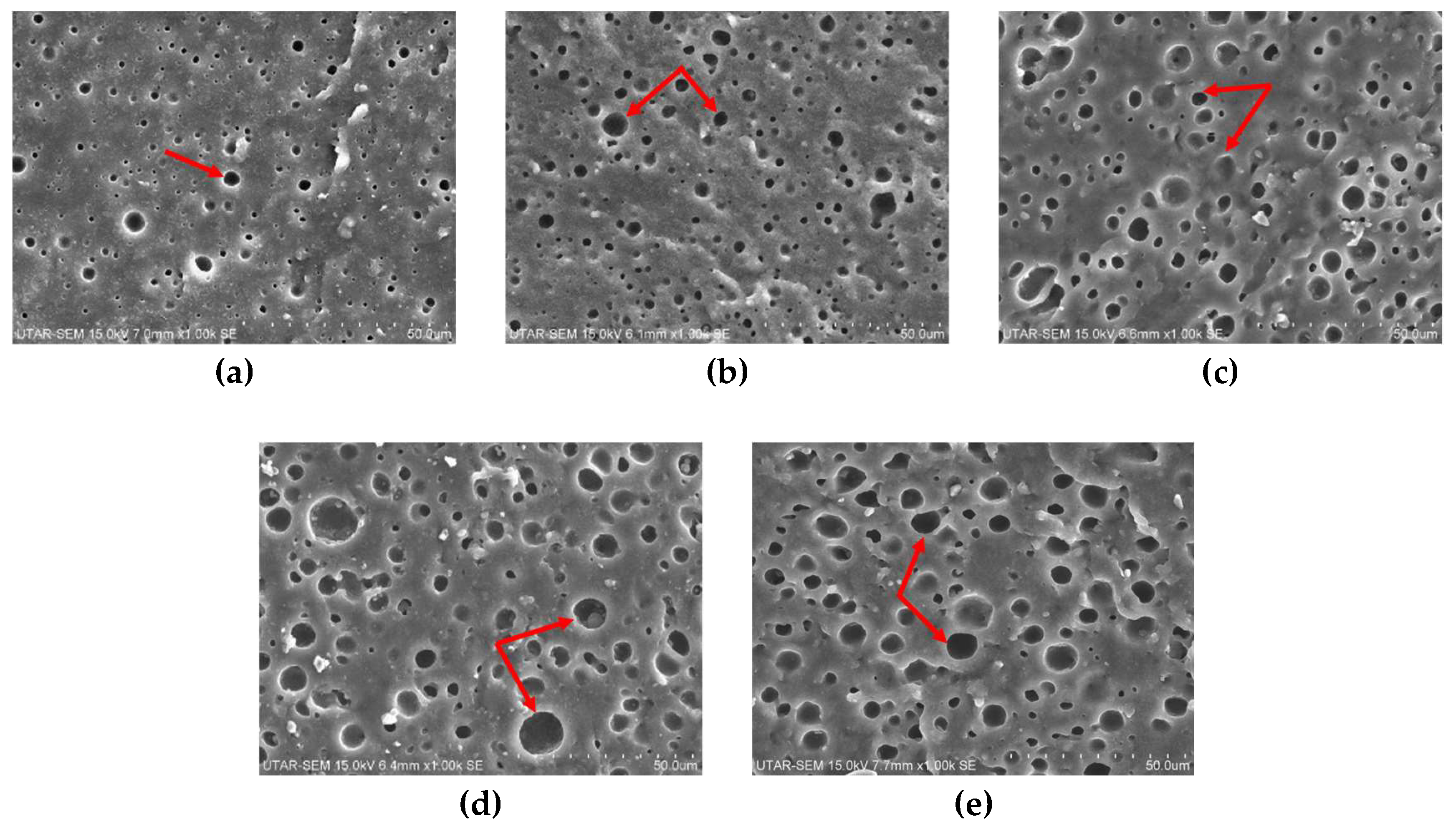

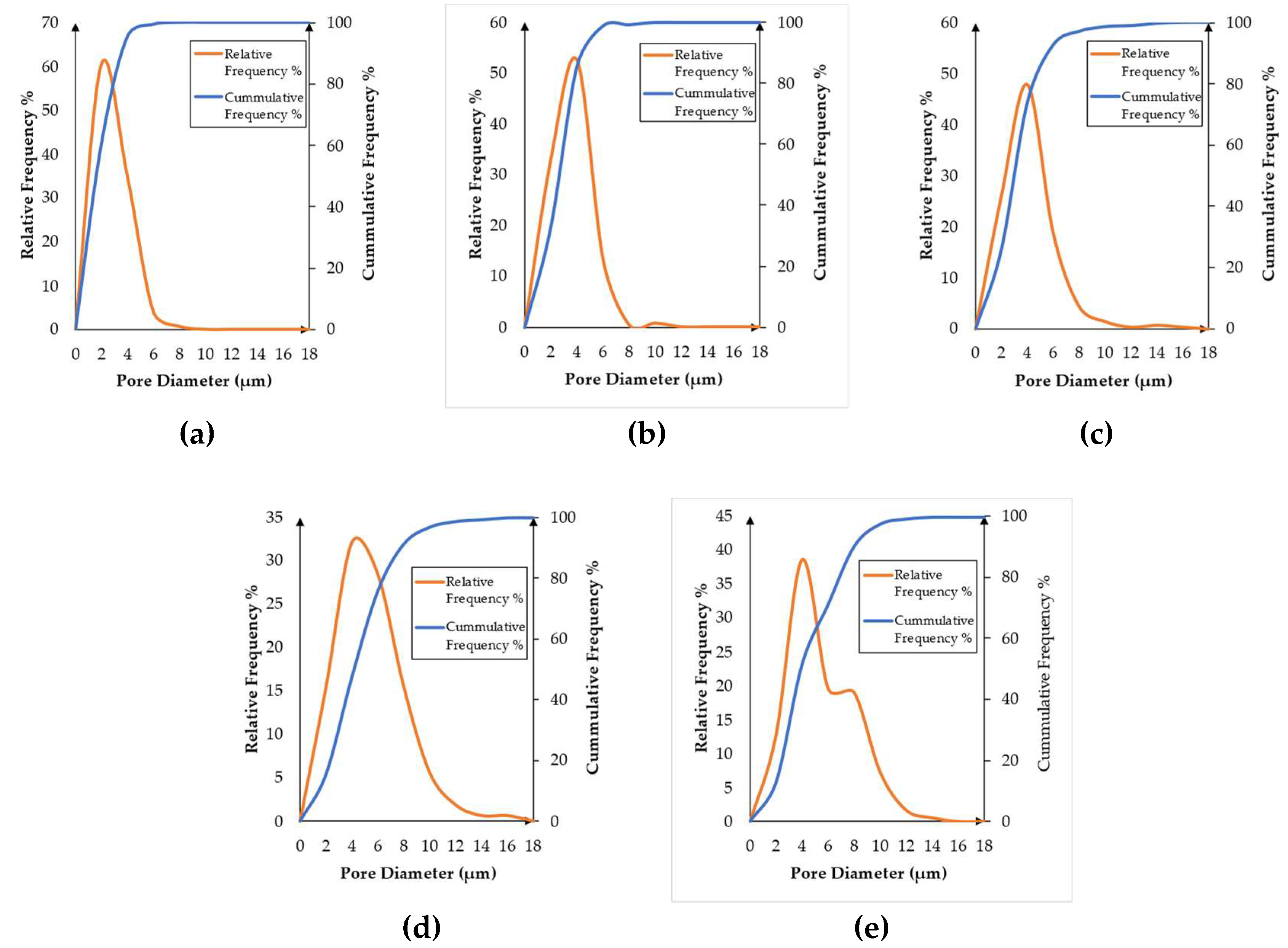

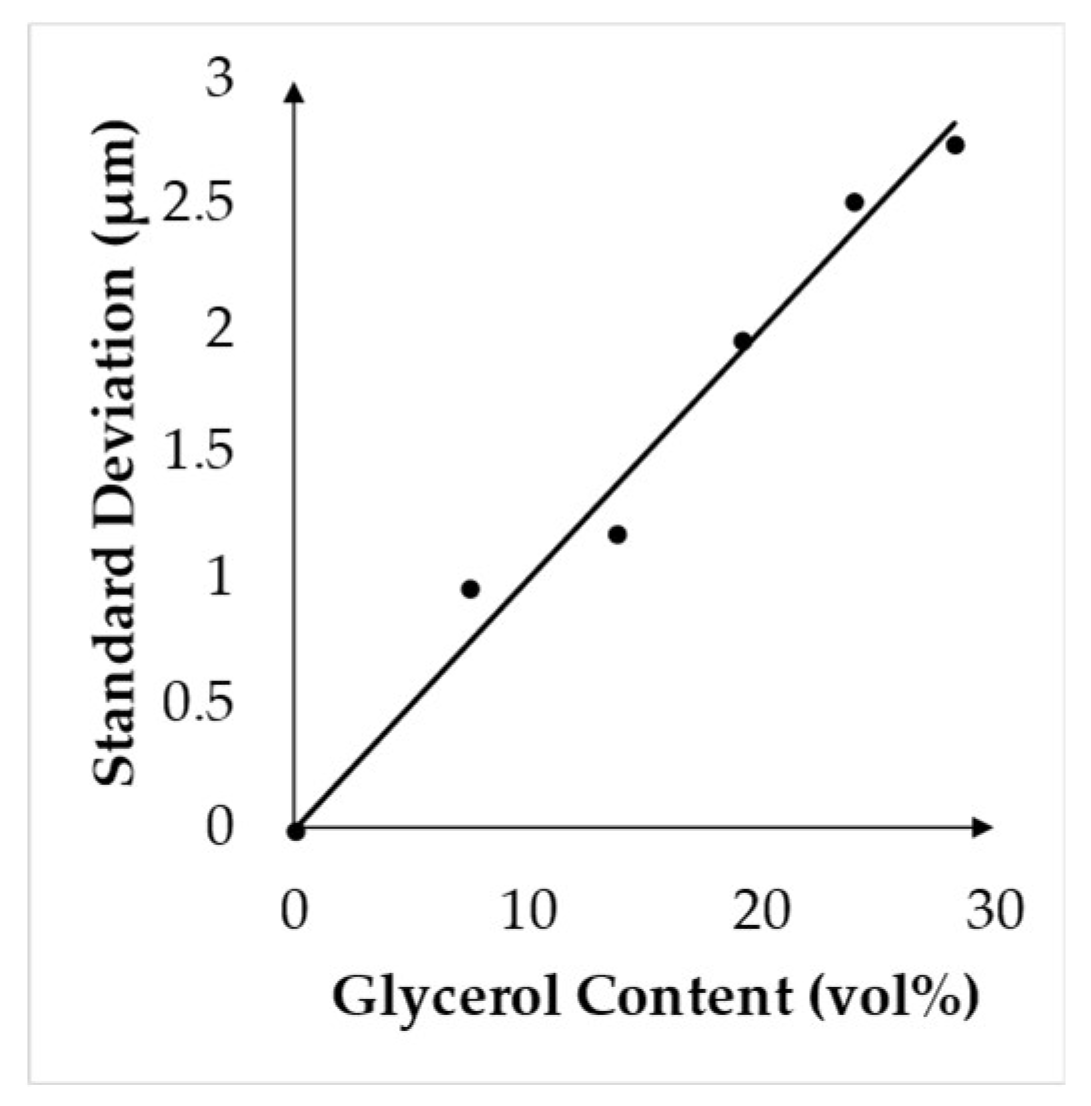

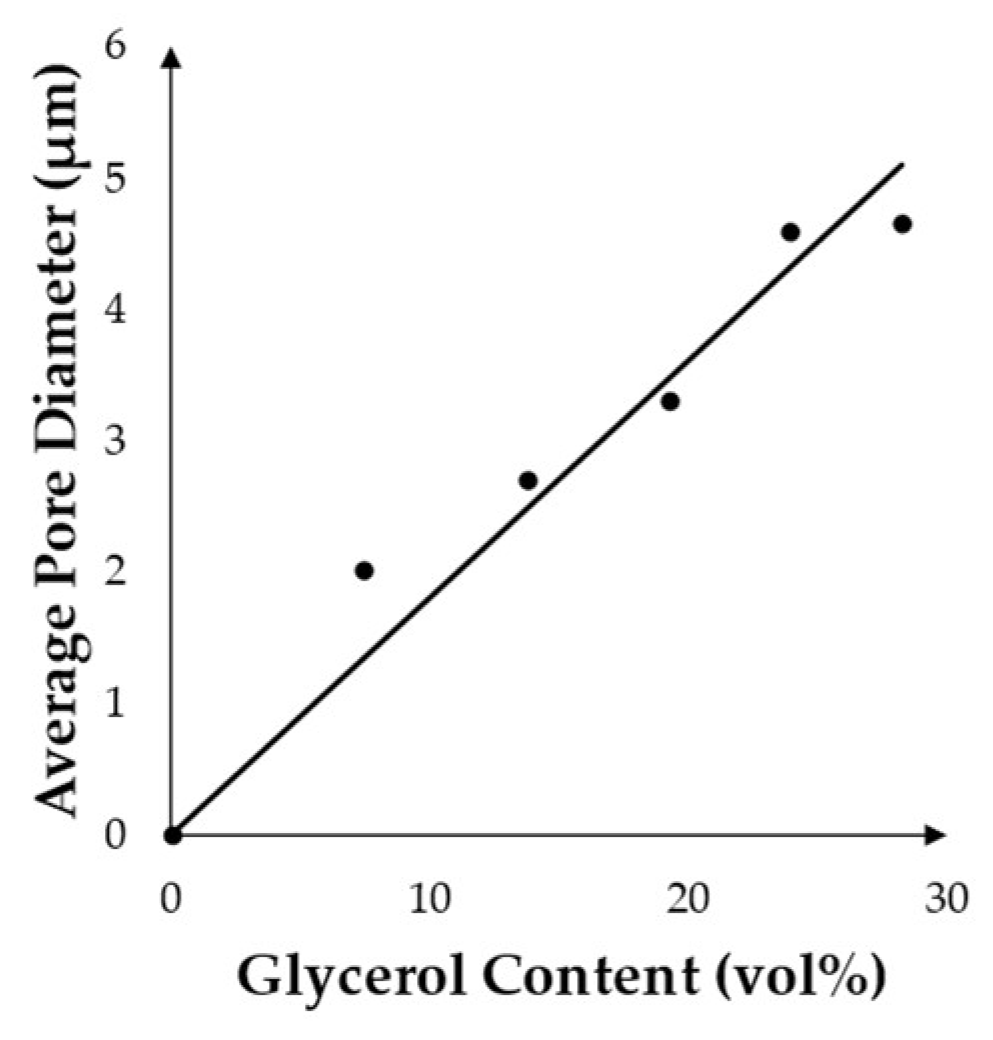

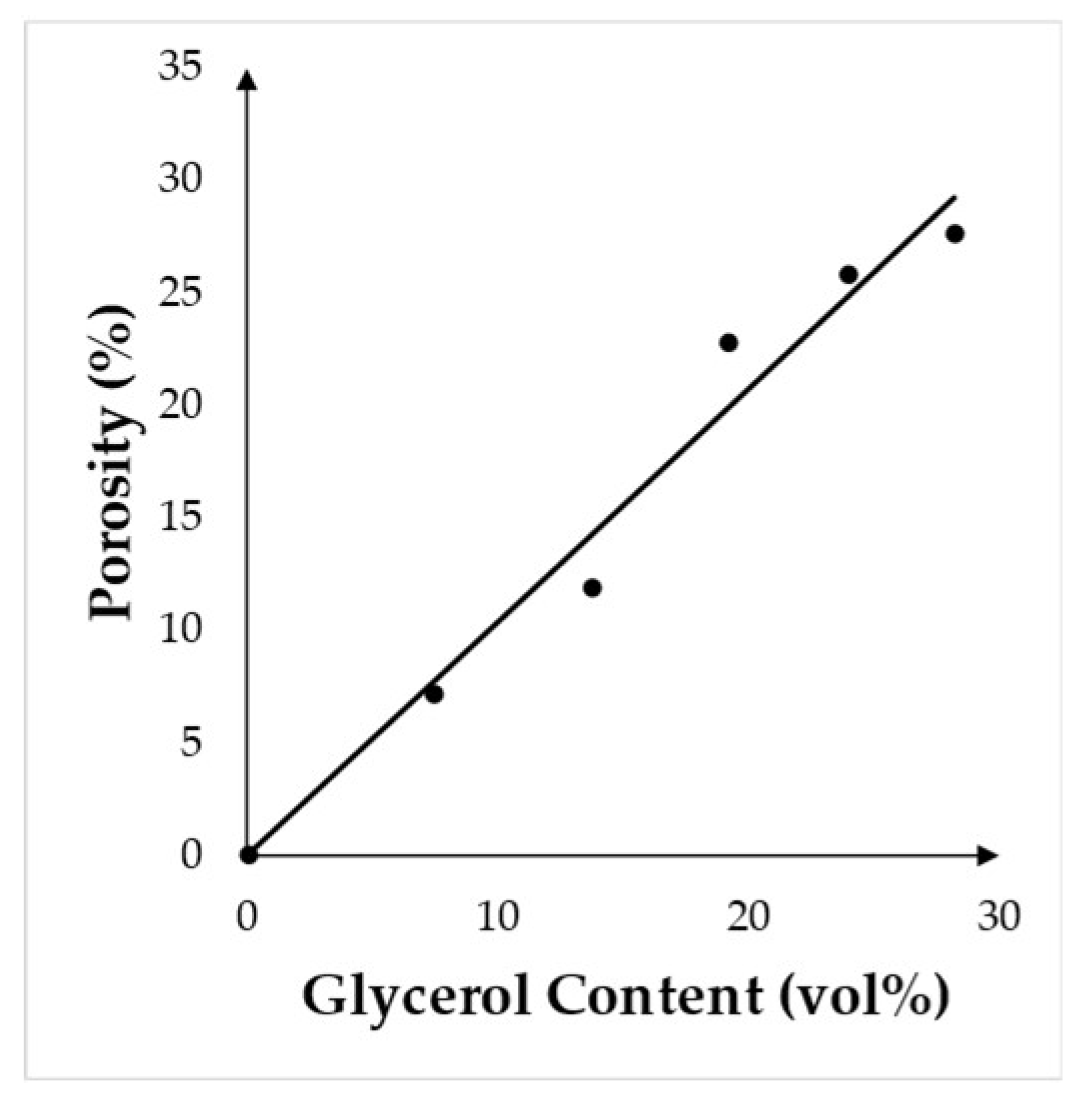

3.2. Porosity

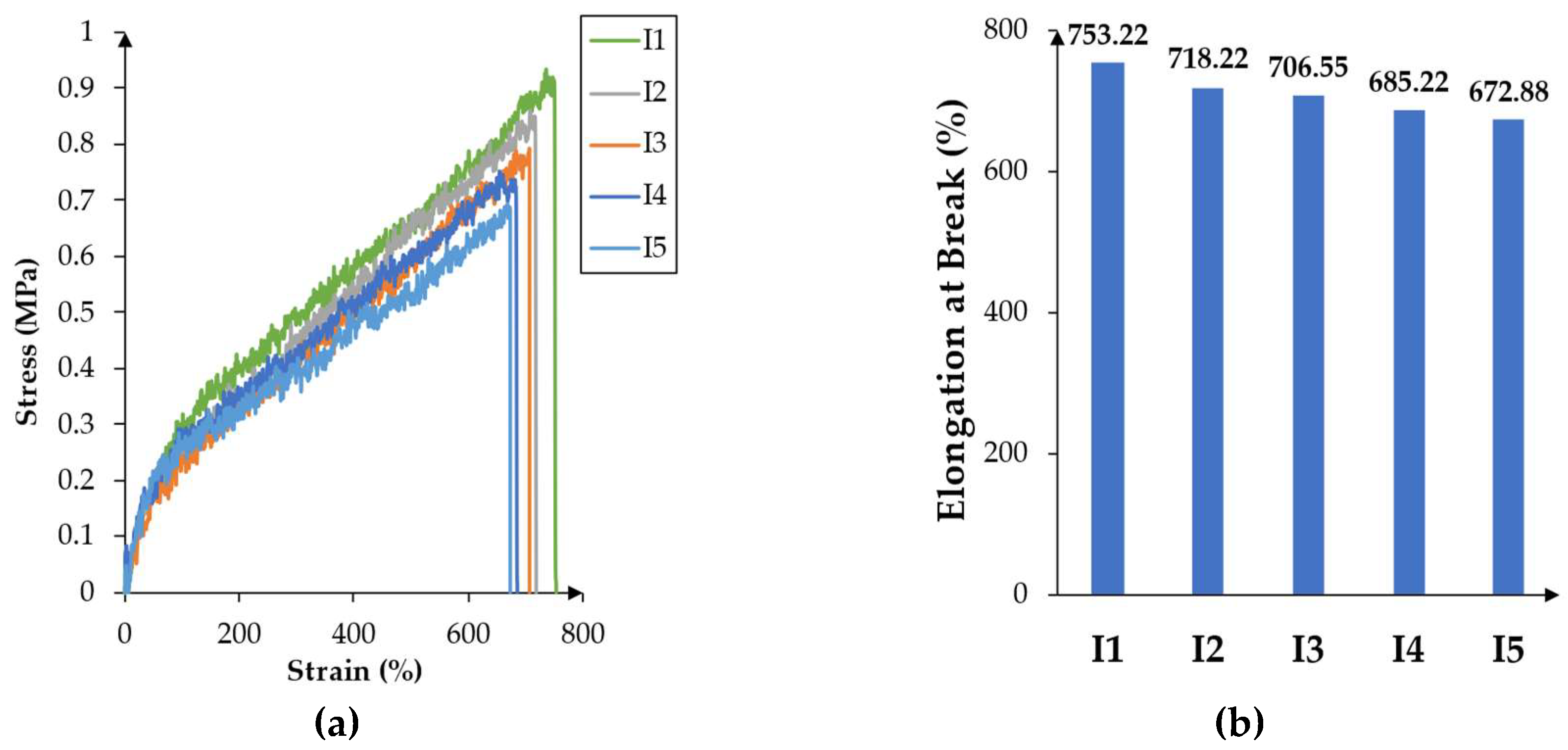

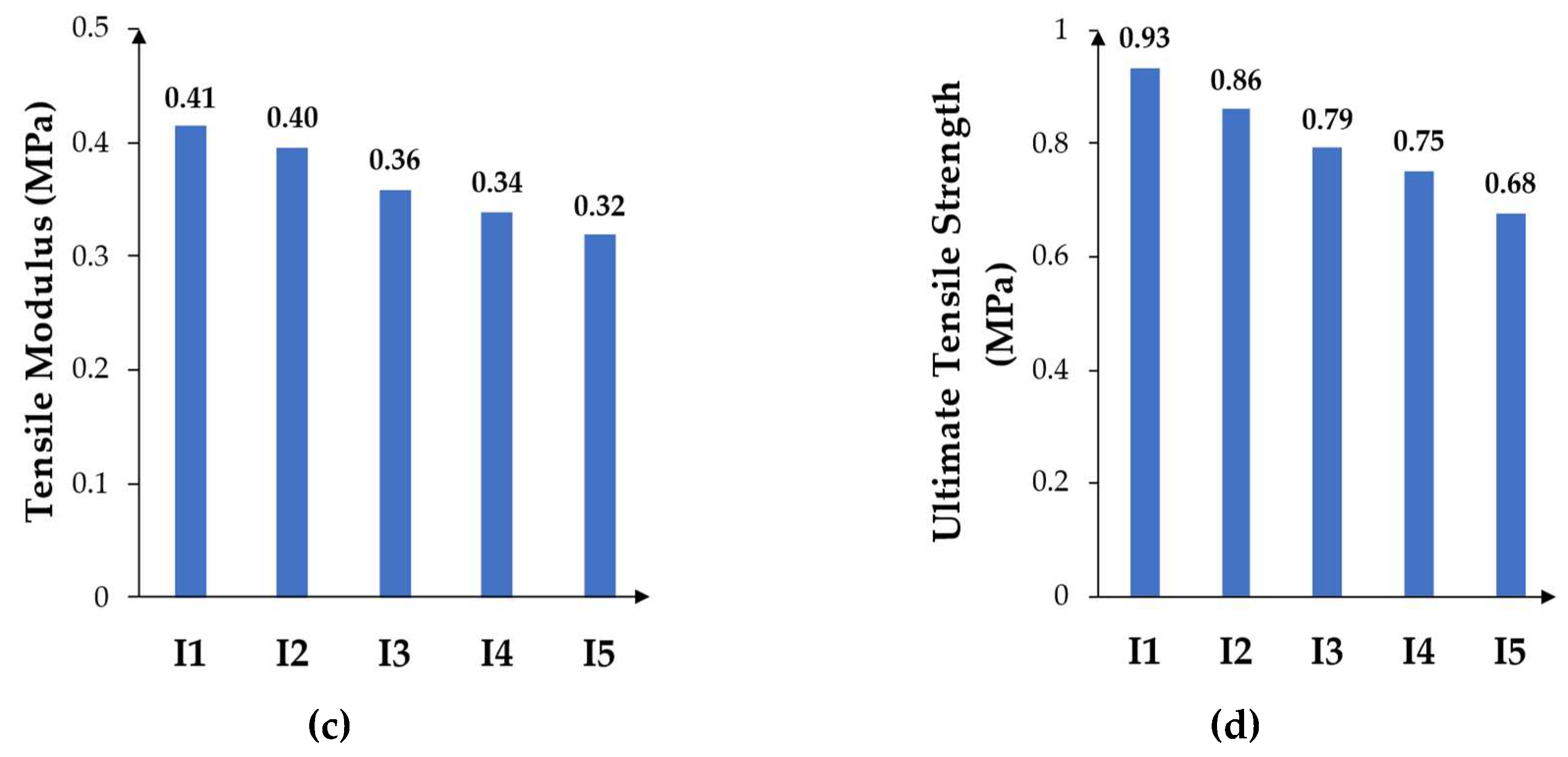

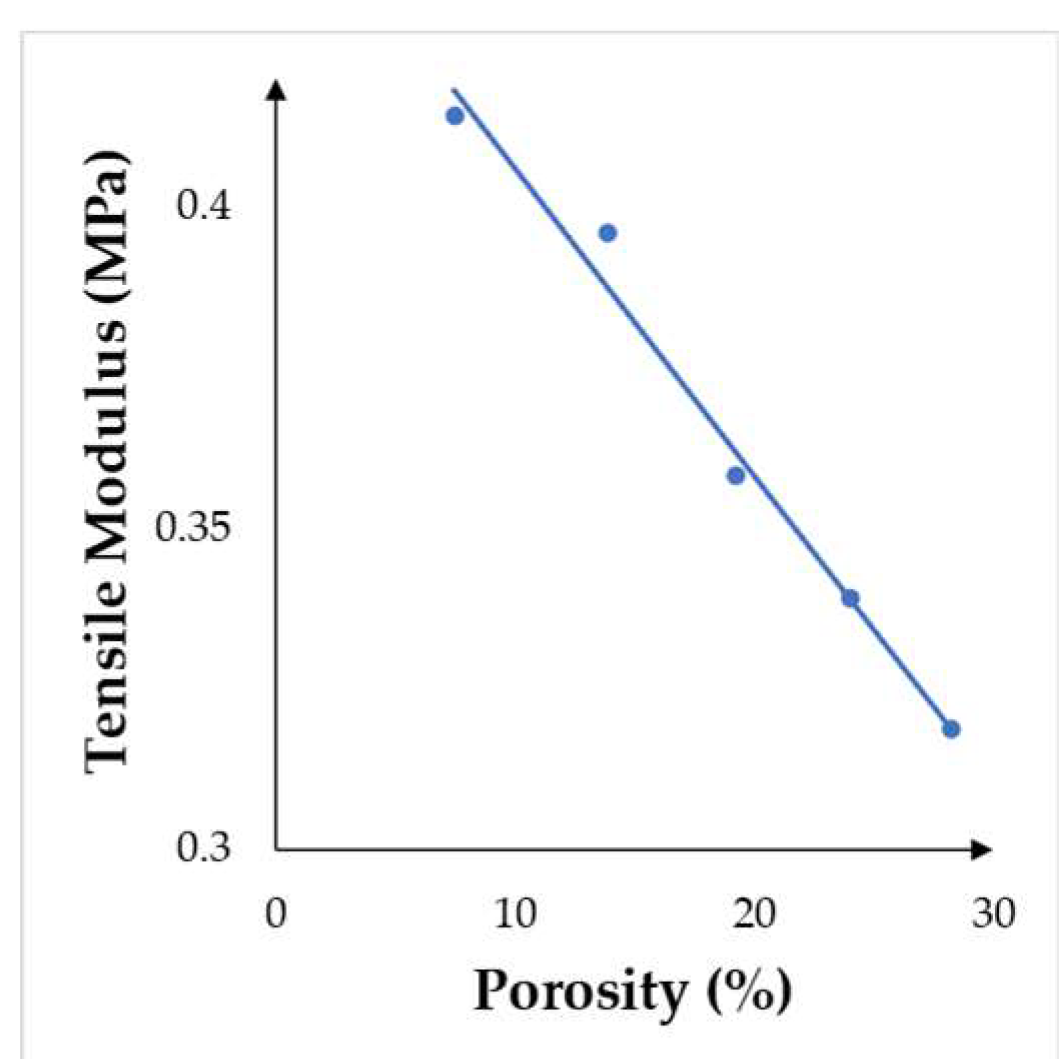

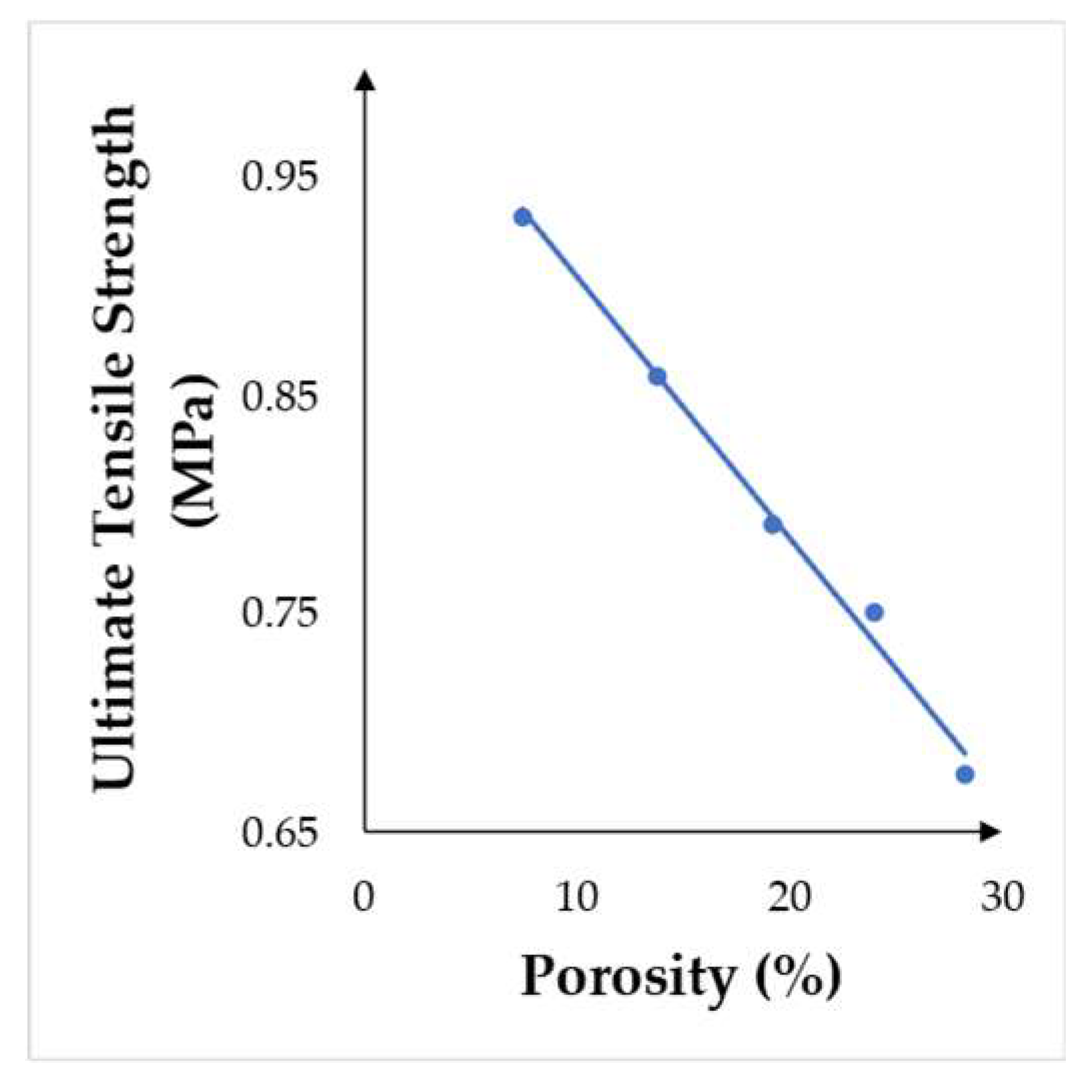

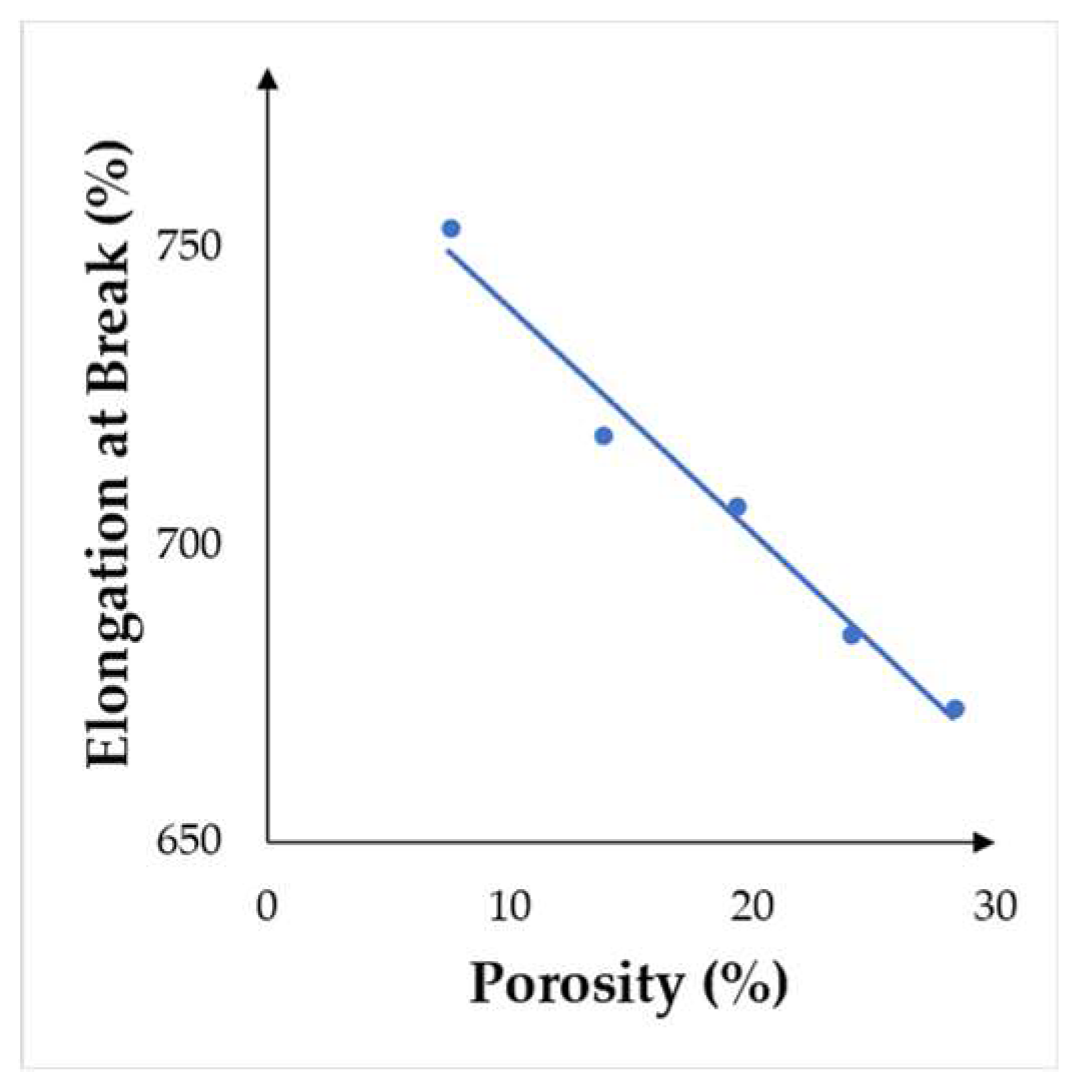

3.3. Tensile Properties

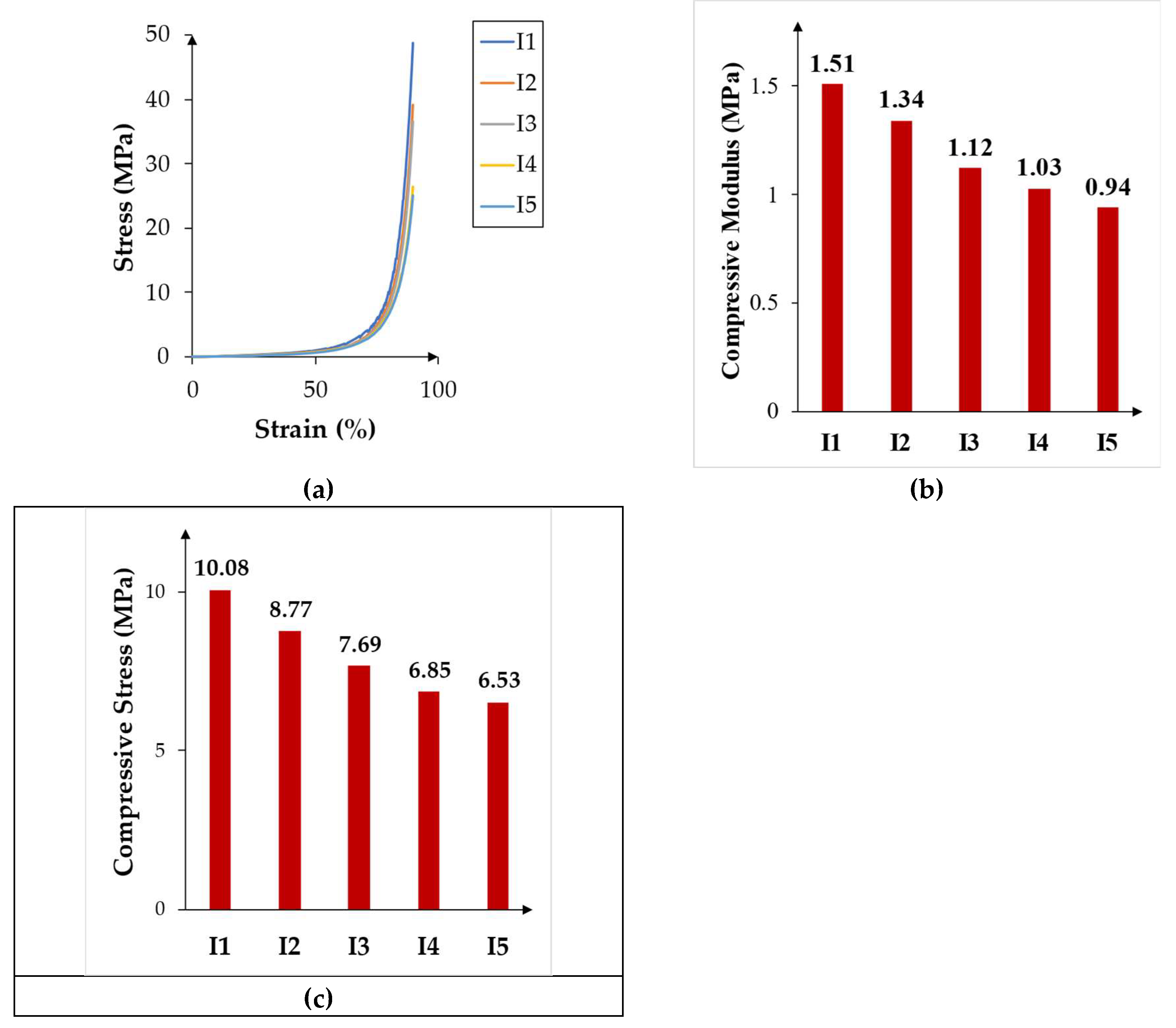

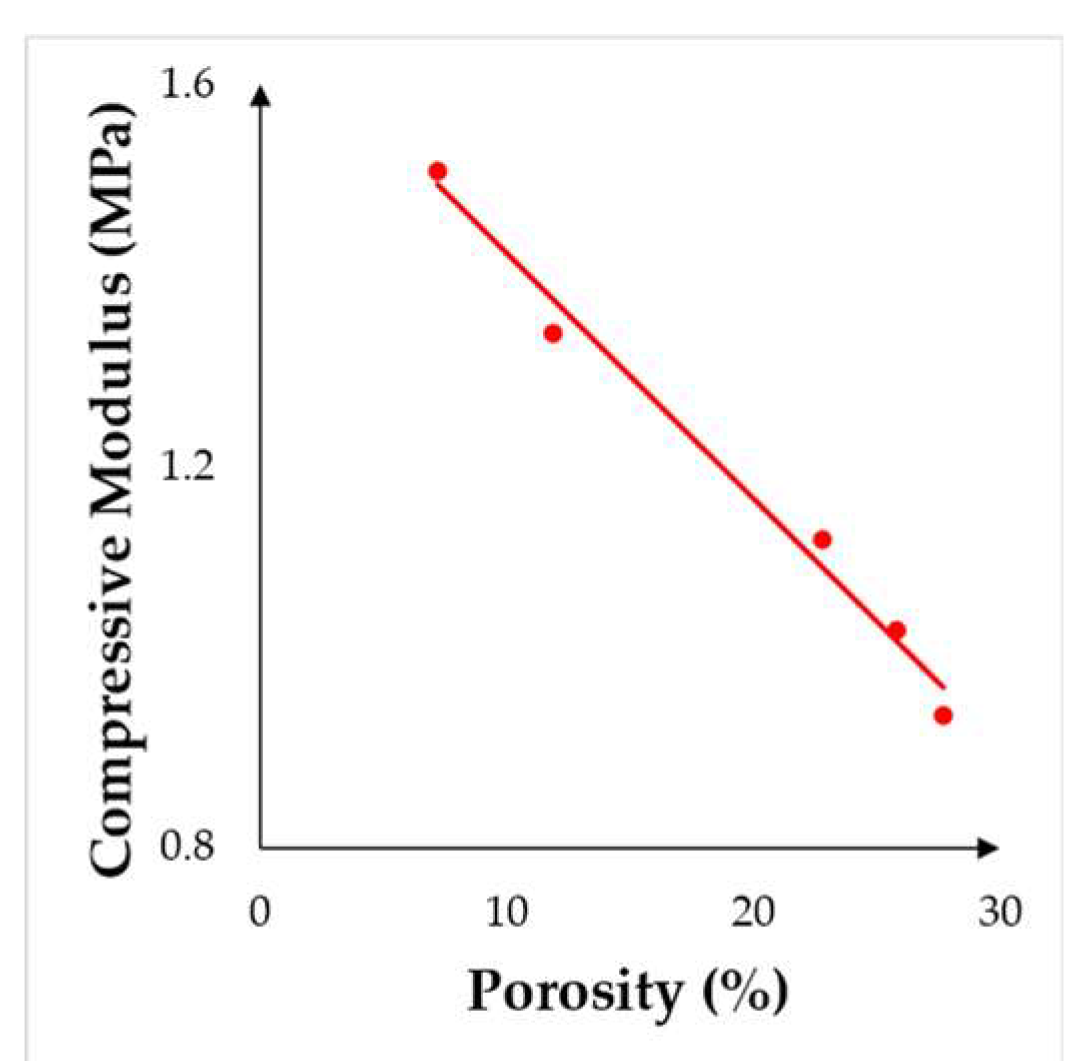

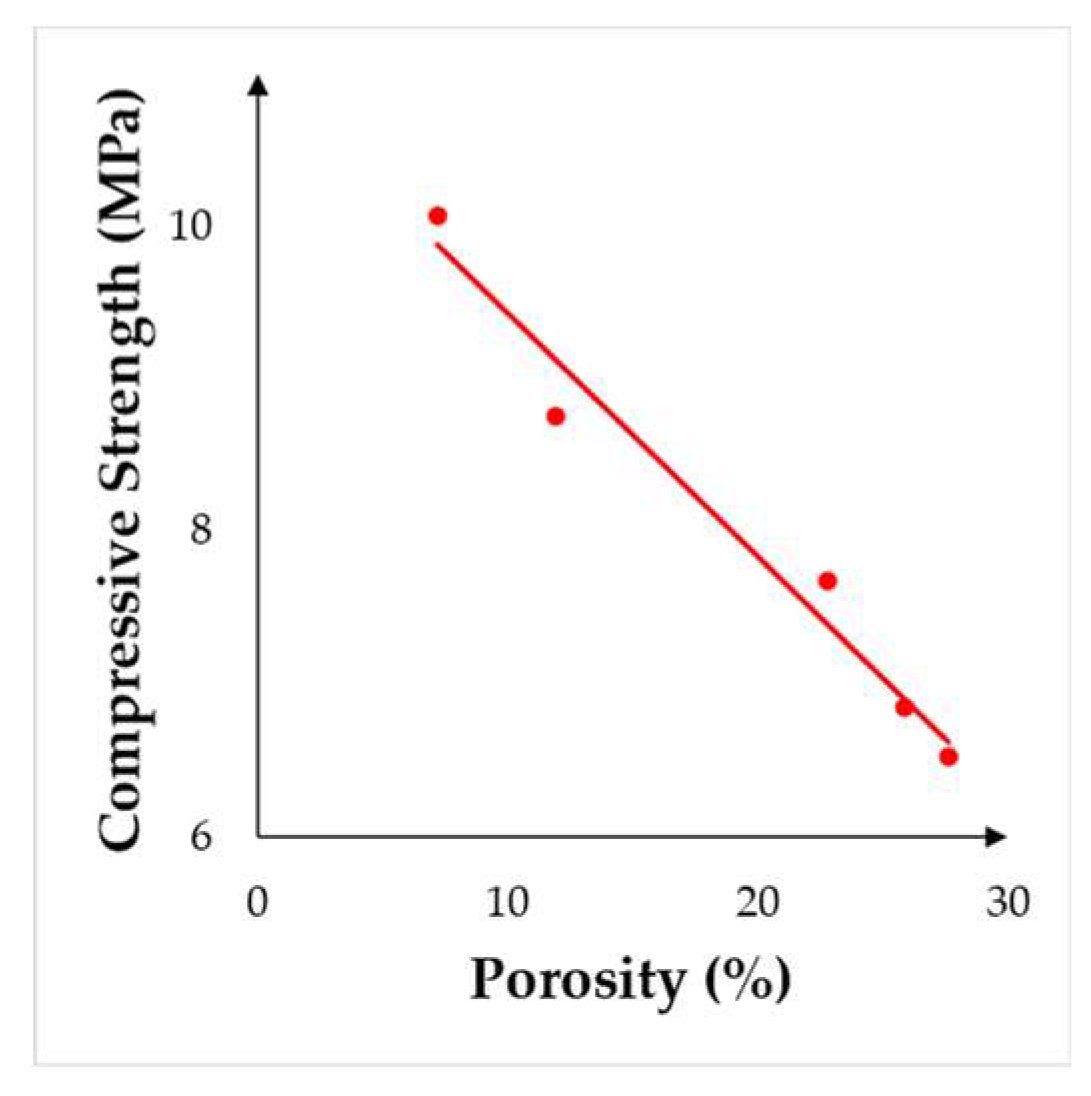

3.4. Compressive Properties

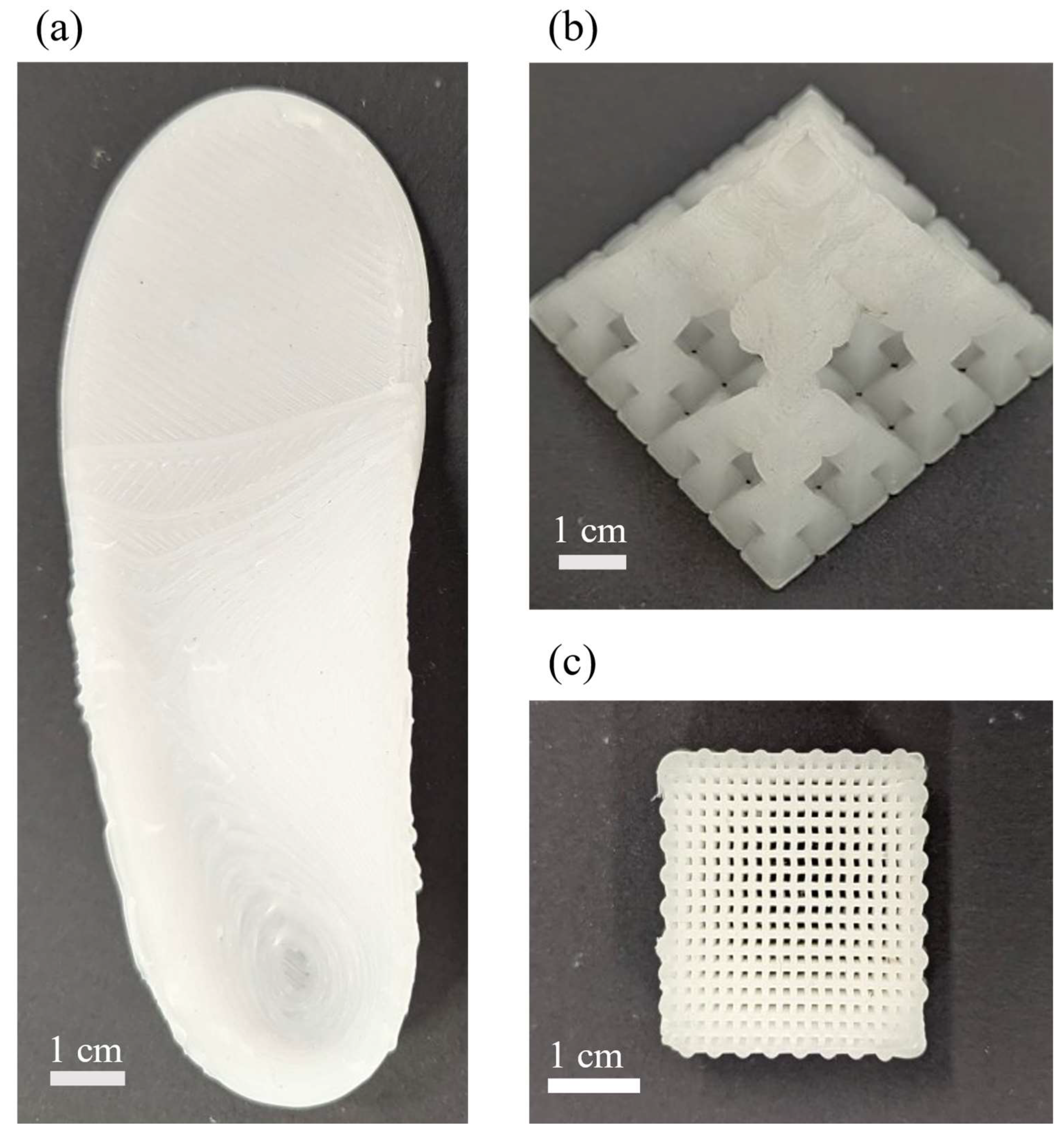

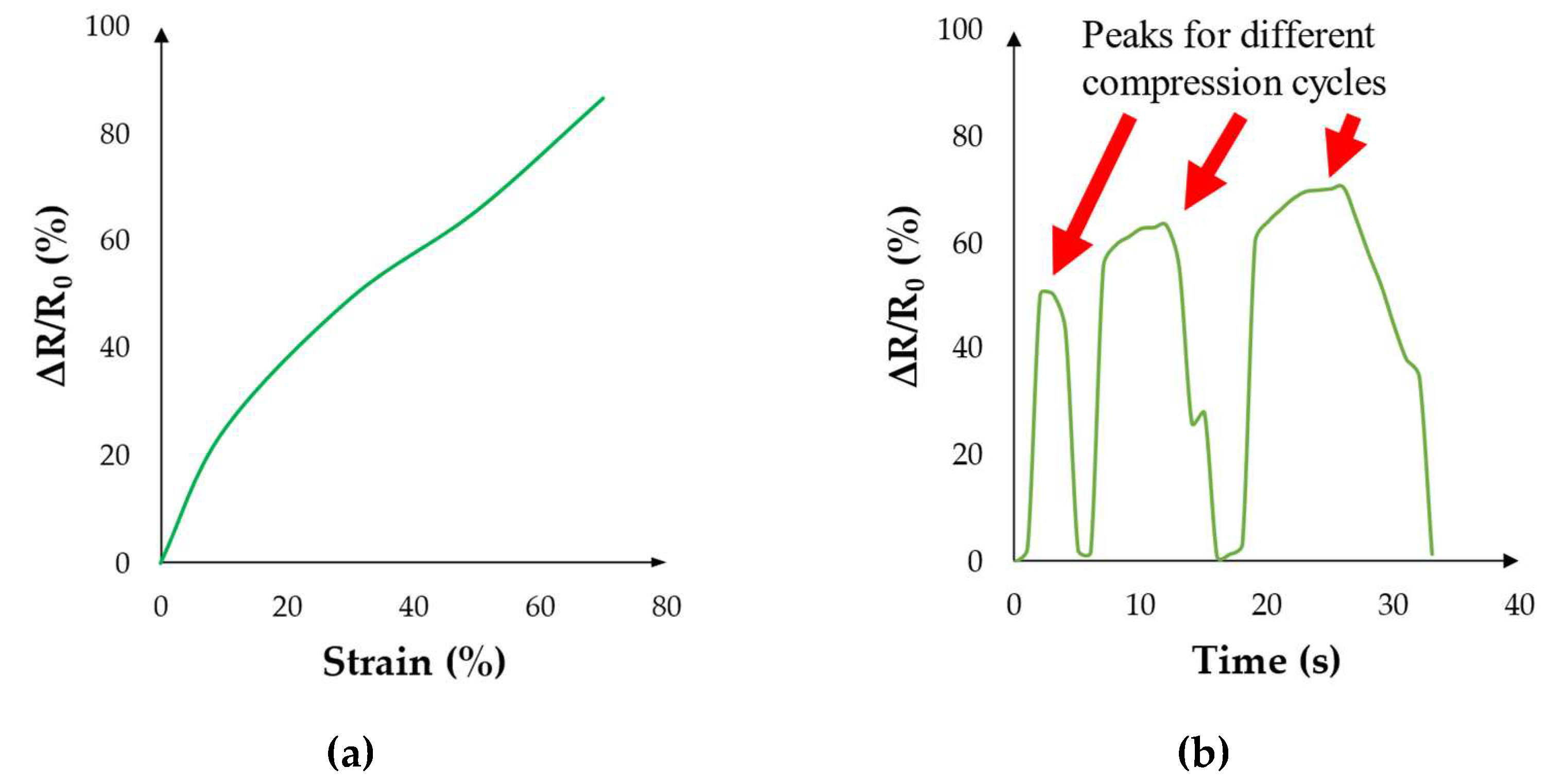

3.5. Potential Applications

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| phr | Parts per hundred rubber |

| DIW | Direct ink writing |

References

- Si, J.; Cui, Z.; Xie, P.; Song, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Liu, C. Characterization of 3D Elastic Porous Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Cell Scaffolds Fabricated by VARTM and Particle Leaching. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Eduok, U.; Faye, O.; Szpunar, J. Recent Developments and Applications of Protective Silicone Coatings: A Review of PDMS Functional Materials. Prog. Org. Coatings 2017, 111, 124–163. [CrossRef]

- Zare, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Venkatraman, P.D.; Ramakrishna, S. Silicone-Based Biomaterials for Biomedical Applications: Antimicrobial Strategies and 3D Printing Technologies. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 138.

- Owen, M.J. Silicone Surface Fundamentals. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, I.; Souza, A.; Sousa, P.; Ribeiro, J.; S Castanheira, E.M.; Lima, R.; Minas, G. Properties and Applications of PDMS for Biomedical Engineering: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ariati, R.; Sales, F.; Souza, A.; Lima, R.A.; Ribeiro, J. Polydimethylsiloxane Composites Characterization and Its Applications: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, S.; Krajnc, P. Hierarchically Porous Microspheres by Thiol-ene Photopoly-Merization of High Internal Phase Emulsions-in-water Colloi-Dal Systems. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Woo, R.; Chen, G.; Zhao, J.; Bae, J. Structure-Mechanical Property Relationships of 3D-Printed Porous Polydimethylsiloxane. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 3496–3503. [CrossRef]

- Berro, S.; El Ahdab, R.; Hajj Hassan, H.; Khachfe, H.M.; Hajj-Hassan, M. From Plastic to Silicone: The Novelties in Porous Polymer Fabrications. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Bindra, H.S.; Paul, D.; Nayak, R. Smart Multi-Tasking PDMS Nanocomposite Sponges for Microbial and Oil Contamination Removal from Water. J. Polym. Res. 2020, 27, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Turco, A.; Primiceri, E.; Frigione, M.; Maruccio, G.; Malitesta, C. An Innovative, Fast and Facile Soft-Template Approach for the Fabrication of Porous PDMS for Oil-Water Separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 23785–23793. [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Gong, Z.; He, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, M.; Lau, W.M. 3D Printing of a Mechanically Durable Superhydrophobic Porous Membrane for Oil-Water Separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 12435–12444. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Chen, M.; Du, C.; Guo, H.; Bai, H.; Li, L. Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Oil Absorbent with a Three-Dimensionally Interconnected Porous Structure and Swellable Skeleton. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 10201–10206. [CrossRef]

- Razavi, M.; Primavera, R.; Vykunta, A.; Thakor, A.S. Materials Science & Engineering C Silicone-Based Bioscaffolds for Cellular Therapies. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119, 111615. [CrossRef]

- Díaz Lantada, A.; Alarcón Iniesta, H.; Pareja Sánchez, B.; García-Ruíz, J.P. Free-Form Rapid Prototyped Porous PDMS Scaffolds Incorporating Growth Factors Promote Chondrogenesis. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pedraza, E.; Brady, A.C.; Fraker, C.A.; Molano, R.D.; Sukert, S.; Berman, D.M.; Kenyon, N.S.; Pileggi, A.; Ricordi, C.; Stabler, C.L. Macroporous Three-Dimensional PDMS Scaffolds for Extrahepatic Islet Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2013, 22, 1123–1125. [CrossRef]

- Montazerian, H.; Mohamed, M.G.A.; Montazeri, M.M.; Kheiri, S.; Milani, A.S.; Kim, K.; Hoorfar, M. Permeability and Mechanical Properties of Gradient Porous PDMS Scaffolds Fabricated by 3D-Printed Sacrificial Templates Designed with Minimal Surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2019, 96, 149–160. [CrossRef]

- González-Rivera, J.; Iglio, R.; Barillaro, G.; Duce, C.; Tinè, M.R. Structural and Thermoanalytical Characterization of 3D Porous PDMS Foam Materials: The Effect of Impurities Derived from a Sugar Templating Process. Polymers (Basel). 2018, 10, 616. [CrossRef]

- Masihi, S.; Panahi, M.; Maddipatla, D.; Hanson, A.J.; Bose, A.K.; Hajian, S.; Palaniappan, V.; Narakathu, B.B.; Bazuin, B.J.; Atashbar, M.Z. Highly Sensitive Porous PDMS-Based Capacitive Pressure Sensors Fabricated on Fabric Platform for Wearable Applications. ACS Sensors 2021, 6, 938–949. [CrossRef]

- Abshirini, M.; Saha, M.C.; Cummings, L.; Robison, T. Synthesis and Characterization of Porous Polydimethylsiloxane Structures with Adjustable Porosity and Pore Morphology Using Emulsion Templating Technique. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2021, 61, 1943–1955. [CrossRef]

- Abshirini, M.; Marashizadeh, P.; Saha, M.C.; Altan, M.C.; Liu, Y. Three-Dimensional Printed Highly Porous and Flexible Conductive Polymer Nanocomposites with Dual-Scale Porosity and Piezoresistive Sensing Functions. Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 14810–14825. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kim, Y.; Yang, H.; Oh, J.H. Fabrication of Hierarchically Porous Structured PDMS Composites and Their Application as a Flexible Capacitive Pressure Sensor. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 211, 108607. [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, E.; Montazerian, H.; Haghniaz, R.; Rashidi, A.; Ahadian, S.; Sheikhi, A.; Chen, J.; Khademhosseini, A.; Milani, A.S.; Hoorfar, M.; et al. 3D-Printed Ultra-Robust Surface-Doped Porous Silicone Sensors for Wearable Biomonitoring. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1520–1532. [CrossRef]

- Kalkal, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Pradhan, R.; Willander, M.; Packirisamy, G.; Kumar, S.; Malhotra, B.D. Recent Advances in 3D Printing Technologies for Wearable (Bio)Sensors. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102088. [CrossRef]

- Métivier, T.; Cassagnau, P. New Trends in Cellular Silicone: Innovations and Applications. J. Cell. Plast. 2019, 55, 151–200. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Yu, C.; Cui, L.; Song, Z.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, L. Facile Preparation of the Porous PDMS Oil-Absorbent for Oil/Water Separation. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 4, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Duan, T.; Shao, J.; Yu, H. Fabrication Method for Structured Porous Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 11873–11882. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J.K.; Algadi, H.; Al-Sayari, S.; Kim, D.E.; Kim, D.E.; Lee, T. Highly Sensitive Pressure Sensor Based on Bioinspired Porous Structure for Real-Time Tactile Sensing. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2016, 2. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, Y.; Hua, W.; Wang, Y.; You, G.; Li, P.; Liao, F.; Zhao, L.; Ding, Y. Improved Flowing Behaviour and Gas Exchange of Stored Red Blood Cells by a Compound Porous Structure. Artif. Cells, Nanomedicine Biotechnol. 2019, 47, 1888–1897. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, A.; Gu, H.; Qin, G.; Zhang, J.; Xu, J.; Jiang, G.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, H. Highly Interconnected Porous PDMS/CNTs Sandwich Sponges with Anti-Icing/Deicing Microstructured Surfaces. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 11723–11735. [CrossRef]

- Rauzan, B.M.; Nelson, A.Z.; Lehman, S.E.; Ewoldt, R.H.; Nuzzo, R.G. Particle-Free Emulsions for 3D Printing Elastomers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Sanguramath, R.A.; Israel, S.; Silverstein, M.S. Emulsion Templating: Porous Polymers and Beyond. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 5445–5479. [CrossRef]

- Racles, C.; Bele, A.; Vasiliu, A.L.; Sacarescu, L. Emulsion Gels as Precursors for Porous Silicones and All-Polymer Composites—A Proof of Concept Based on Siloxane Stabilizers. Gels 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Riesco, R.; Boyer, L.; Blosse, S.; Lefebvre, P.M.; Assemat, P.; Leichle, T.; Accardo, A.; Malaquin, L. Water-in-PDMS Emulsion Templating of Highly Interconnected Porous Architectures for 3D Cell Culture. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 28631–28640. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, Y.; Jo, E.; Kang, Y.; Kim, J. Highly Transparent Porous Polydimethylsiloxane with Micro-Size Pores Using Water and Isopropanol Mixture. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 33rd International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS); IEEE: Vancouver, 2020; Vol. 2020-Janua, pp. 287–290.

- Zhao, J.; Luo, G.; Wu, J.; Xia, H. Preparation of Microporous Silicone Rubber Membrane with Tunable Pore Size via Solvent Evaporation-Induced Phase Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 2040–2046. [CrossRef]

- Gharaie, S.; Zolfagharian, A.; Moghadam, A.A.A.; Shukur, N.; Bodaghi, M.; Mosadegh, B.; Kouzani, A. Direct 3D Printing of a Two-Part Silicone Resin to Fabricate Highly Stretchable Structures. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Xie, B.; Xu, Z.; Wu, H. A Systematic Printability Study of Direct Ink Writing towards High-Resolution Rapid Manufacturing. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2023, 5, 035002. [CrossRef]

- Marnot, A.; Dobbs, A.; Brettmann, B. Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing of Dense Pastes Consisting of Macroscopic Particles. MRS Commun. 2022, 12, 483–494. [CrossRef]

- M’Barki, A.; Bocquet, L.; Stevenson, A.; M’Barki, A.; Bocquet, L.; Stevenson, A. Linking Rheology and Printability for Dense and Strong Ceramics by Direct Ink Writing. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6017. [CrossRef]

- Loeb, C.K.; Nguyen, D.T.; Bryson, T.M.; Duoss, E.B.; Wilson, T.S.; Lenhardt, J.M. Hierarchical 3D Printed Porous Silicones with Porosity Derived from Printed Architecture and Silicone-Shell Microballoons. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55. [CrossRef]

- Slámečka, K.; Kashimbetova, A.; Pokluda, J.; Zikmund, T.; Kaiser, J.; Montufar, E.B.; Čelko, L. Fatigue Behaviour of Titanium Scaffolds with Hierarchical Porosity Produced by Material Extrusion Additive Manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2023, 225. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, P.; Ekbrant, B.E.F.; Madsen, F.B.; Yu, L.; Skov, A.L. Glycerol-Silicone Foams – Tunable 3-Phase Elastomeric Porous Materials. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 113, 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Zargar, R.; Nourmohammadi, J.; Amoabediny, G. Preparation, Characterization, and Silanization of 3D Microporous PDMS Structure with Properly Sized Pores for Endothelial Cell Culture. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2016, 63, 190–199. [CrossRef]

- Ozbolat, V.; Dey, M.; Ayan, B.; Povilianskas, A.; Demirel, M.C.; Ozbolat, I.T. 3D Printing of PDMS Improves Its Mechanical and Cell Adhesion Properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 682–693. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, P.; Hvilsted, S.; Skov, A.L. Green Silicone Elastomer Obtained from a Counterintuitively Stable Mixture of Glycerol and PDMS. Polymer (Guildf). 2016, 87, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Gerling, G.J.; Hauser, S.C.; Soltis, B.R.; Bowen, A.K.; Fanta, K.D.; Wang, Y. A Standard Methodology to Characterize the Intrinsic Material Properties of Compliant Test Stimuli. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2018, 11, 498–508. [CrossRef]

- Humairah, S.; Nabilah, N.; Abd, C.; Mahmud, J.; Mohammed, M.N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Alkhatib, S.E.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Hyperelastic Properties of Bamboo Cellulosic Fibre – Reinforced Silicone Rubber Biocomposites via Compression Test. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6338.

- Del-Mazo-Barbara, L.; Ginebra, M. Rheological Characterisation of Ceramic Inks for 3D Direct Ink Writing : A Review. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 18–33. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, D.; Shang, E.; Liu, Y. A Heating-Assisted Direct Ink Writing Method for Preparation of PDMS Cellular Structure with High Manufacturing Fidelity. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 1323. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Jia, S.; Shi, X.; Li, B.; Zhou, C. Coaxial Printing of Silicone Elastomer Composite Fibers for Stretchable and Wearable Piezoresistive Sensors. Polymers (Basel). 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Courtial, E.; Perrinet, C.; Colly, A.; Mariot, D.; Frances, J. Silicone Rheological Behavior Modification for 3D Printing : Evaluation of Yield Stress Impact on Printed Object Properties. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 50–57. [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Koh, J.J.; Lim, G.J.H.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, T.; Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Duan, J.; Ding, J.; Wang, J.; et al. Direct Ink Writing of Programmable Functional Silicone-based Composites for 4D Printing Applications. Interdiscip. Mater. 2022, 1, 507–516. [CrossRef]

- Ang, X.; Tey, J.Y.; Yeo, W.H.; Shak, K.P.Y. A Review on Metallic and Ceramic Material Extrusion Method: Materials, Rheology, and Printing Parameters. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 90, 28–42.

- Danner, P.M.; Pleij, T.; Siqueira, G.; Bayles, A. V.; Venkatesan, T.R.; Vermant, J.; Opris, D.M. Polysiloxane Inks for Multimaterial 3d Printing of High-Permittivity Dielectric Elastomers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34.

- Lim, J.J.; Sim, J.H.; Tey, J.Y. Rheological Formulation of Room Temperature Vulcanizing Silicone Elastomer Ink for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing at Room Temperature. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 102, 632–643. [CrossRef]

- Ang, X.; Yuen, J.; Hong, W. 3D Printing of Low Carbon Steel Using Novel Slurry Feedstock Formulation via Material Extrusion Method. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 38, 102174. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhao, J.; Ren, J.; Rong, L.; Cao, P.F.; Advincula, R.C. 3D Printed Multifunctional, Hyperelastic Silicone Rubber Foam. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1900469. [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, P.; Brook, M.A.; Skov, A.L. Glycerol-Silicone Elastomers as Active Matrices with Controllable Release Profiles. Langmuir 2018, 34, 11559–11566. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Scheffold, F.; Mason, T.G. Entropic, Electrostatic, and Interfacial Regimes in Concentrated Disordered Ionic Emulsions. Rheol. Acta 2016, 55, 683–697. [CrossRef]

- Brito, F.; Carvalho-guimar, D.; Correa, K.L.; Souza, T.P. De; Amado, J.R.R.; Riberio-Costa, R.M.; Silva-Júnior, J.O.C. A Review of Pickering Emulsions : Perspectives and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1413. [CrossRef]

- Bhaktha, S.; Hegde, S.; U, R.S.; Gandhi, N. Investigation of Tensile Properties of RTV Silicone Based Isotropic Magnetorheological. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Research in Mechanical Engineering Sciences; MATEC Web of Conferences, 2018; Vol. 144.

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yao, W.; Li, W. Split-Hopkinson Pressure Bar Test of Silicone Rubber : Considering Effects of Strain Rate and Temperature. Polymers (Basel). 2022, 14, 3892.

- Waldemar, G.; Oscar, D.; César, J.; César, A. Effect of Porosity on the Tensile Properties of Low Ductility Aluminum Alloys. Mater. Res. 2004, 7, 221–229.

- Carolis, S. De; Putignano, C.; Soria, L.; Carbone, G. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences Effect of Porosity and Pore Size Distribution on Elastic Modulus of Foams. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 261, 108661. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.U.O.; Guo, D.; Bin, D.A.I.; Meng, Y.; Fang, L.I.U. Study on the Cell Structure and Mechanical Properties of Methyl Vinyl Silicone Rubber Foam Materials. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1005, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Lei, L.; Liu, Y.; Du, L. Improved Mechanical and Sound Absorption Properties of Open Cell Silicone Rubber Foam with NaCl as The. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 195. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, R.; Cheng, H.; Zou, M.; Wang, H.; Zheng, K. Hollow Glass Microspheres/Phenolic Syntactic Foams with Excellent Mechanical and Thermal Insulate Performance. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Alam, M.N.; Yewale, M.A.; Park, S.S. Multifunctional Aspects of Mechanical and Electromechanical Properties of Composites Based on Silicone Rubber for Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting Systems. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, A.; Ullas, A. V. Compressive Properties of Poly (Dimethylsiloxane)–Hollow Glass Microballoons Syntactic Foams. Cell. Polym. 2022, 41, 243–251. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Q.; Chan, M.; Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Liao, W.H. Ultrahigh Energy-Dissipation and Multifunctional Auxetic Polymeric Foam Inspired by Balloon Art. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 167. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, K.; Nakano, K.; Nishiwaki, T.; Iwama, Y.; Murata, M. Effects of Graded Porous Structures on the Mechanical and Electrical Properties of Ketjenblack/Silicone-Rubber Composites. Sensors Actuators A Phys. 2021, 332, 113099. [CrossRef]

- AZoM Silicone Rubber Available online: https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=920 P.

| Ink Designations | Glycerol (phr) | Nanosilica (phr) | PDMS (phr) | Crosslinker (phr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 10 | 8 | 100 | 16.23 |

| I2 | 20 | 10 | 100 | 16.23 |

| I3 | 30 | 12 | 100 | 16.23 |

| I4 | 40 | 14 | 100 | 16.23 |

| I5 | 50 | 14 | 100 | 16.23 |

| Ink Formulation | Static Yield Stress, σyStat (Pa) | Dynamic Yield Stress, σyDyn (Pa) | Viscosity (Pa∙s) | Storage Modulus, G’LVR (Pa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 341.01 | 100.50 | 60.66 | 6461.94 |

| I2 | 318.83 | 191.00 | 55.73 | 8187.86 |

| I3 | 346.32 | 221.60 | 60.84 | 9286.62 |

| I4 | 338.63 | 249.70 | 72.36 | 9451.39 |

| I5 | 318.47 | 185.20 | 47.43 | 6677.00 |

| Foam Samples | D10 (µm) | D50 (µm) | D90 (µm) | Standard Deviation (µm) | Average Pore Diameter (µm) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 1.00 | 1.78 | 3.22 | 0.97 | 2.02 | 7.16 |

| I2 | 1.44 | 2.44 | 4.22 | 1.19 | 2.71 | 11.91 |

| I3 | 1.56 | 2.89 | 5.40 | 1.97 | 3.31 | 22.77 |

| I4 | 1.70 | 4.10 | 7.90 | 2.52 | 4.61 | 25.80 |

| I5 | 2.00 | 3.90 | 8.10 | 2.75 | 4.66 | 27.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).