Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

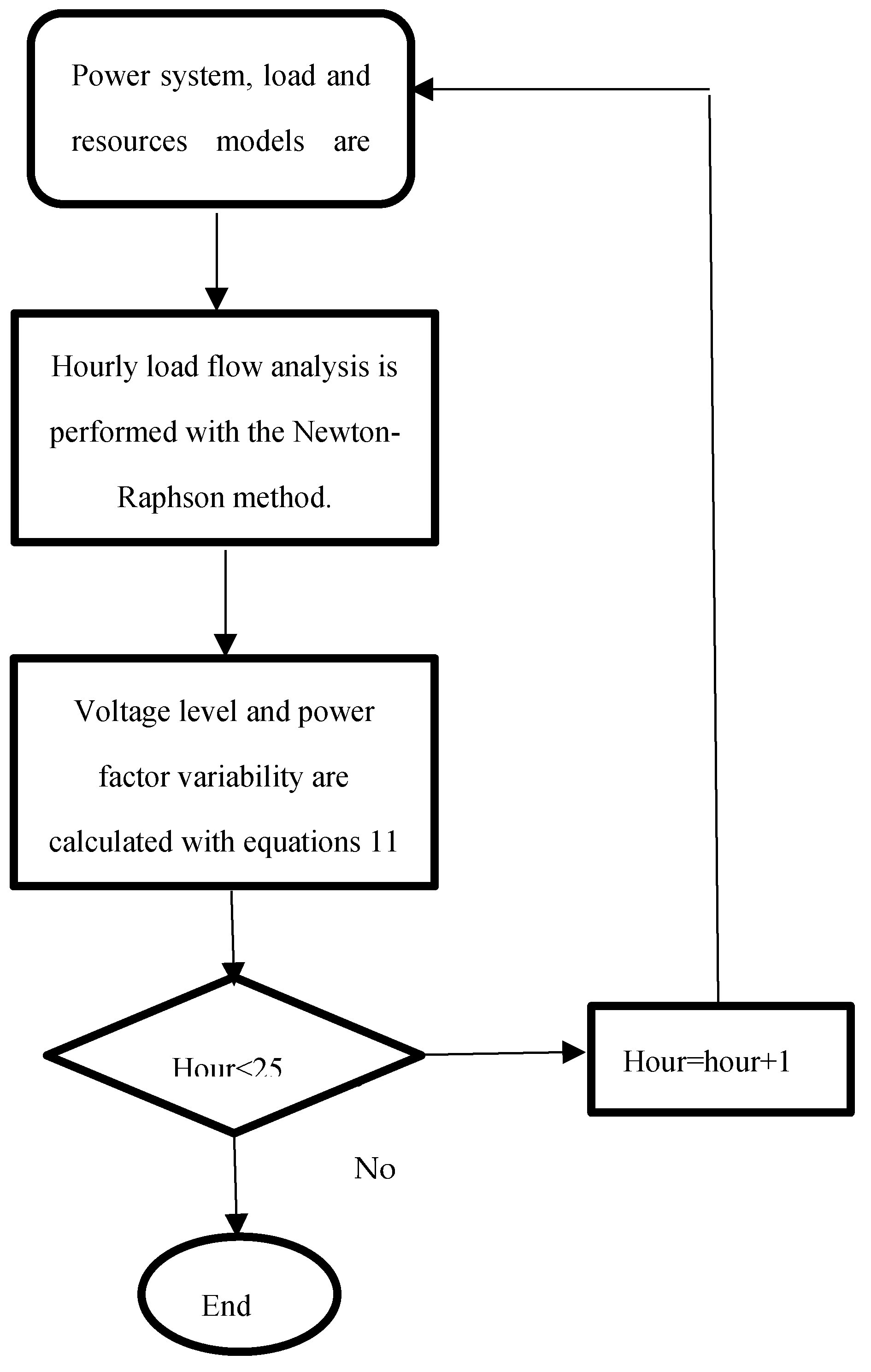

2.1. Numerical Analysis Method

2.1.1. Newton-Raphson Method

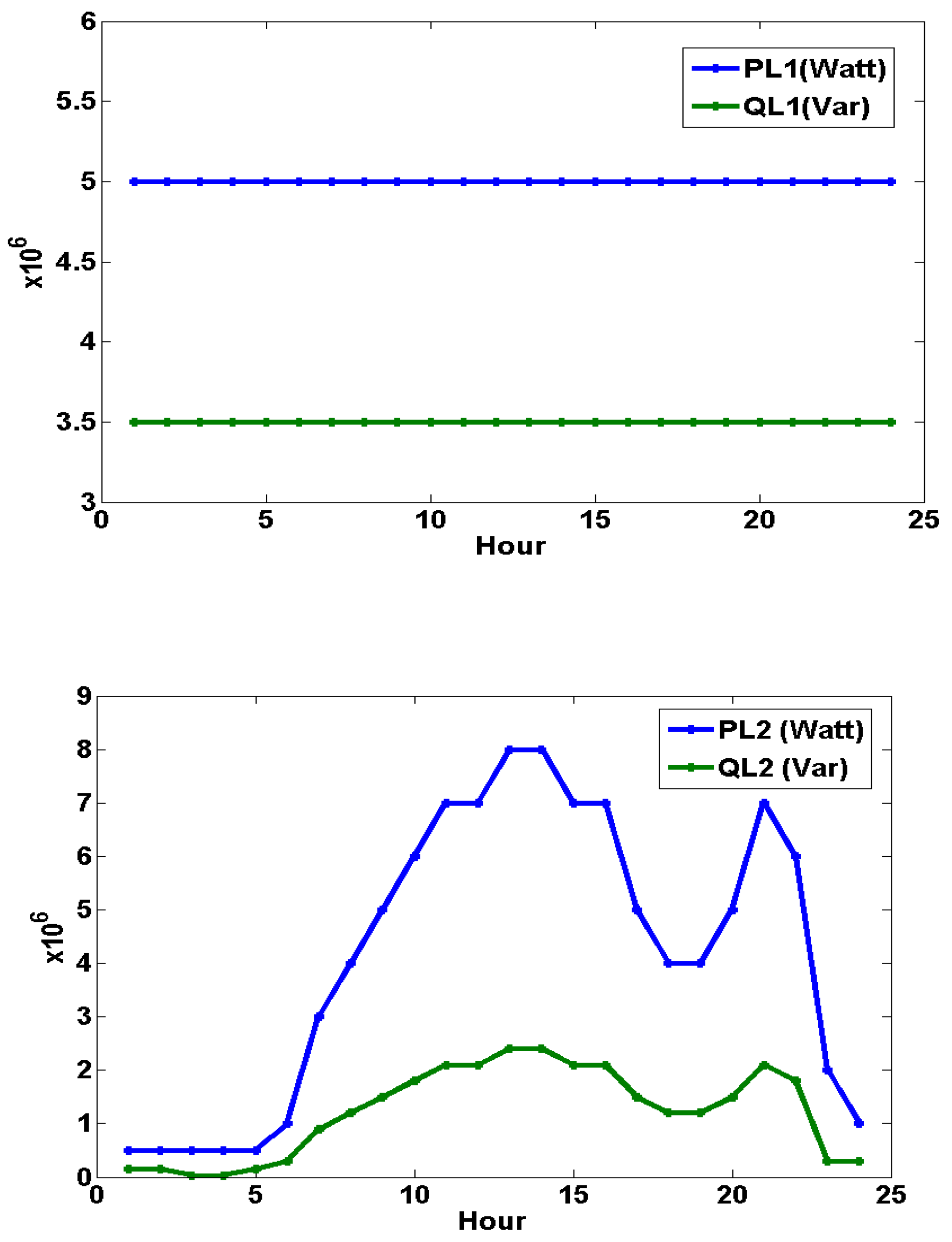

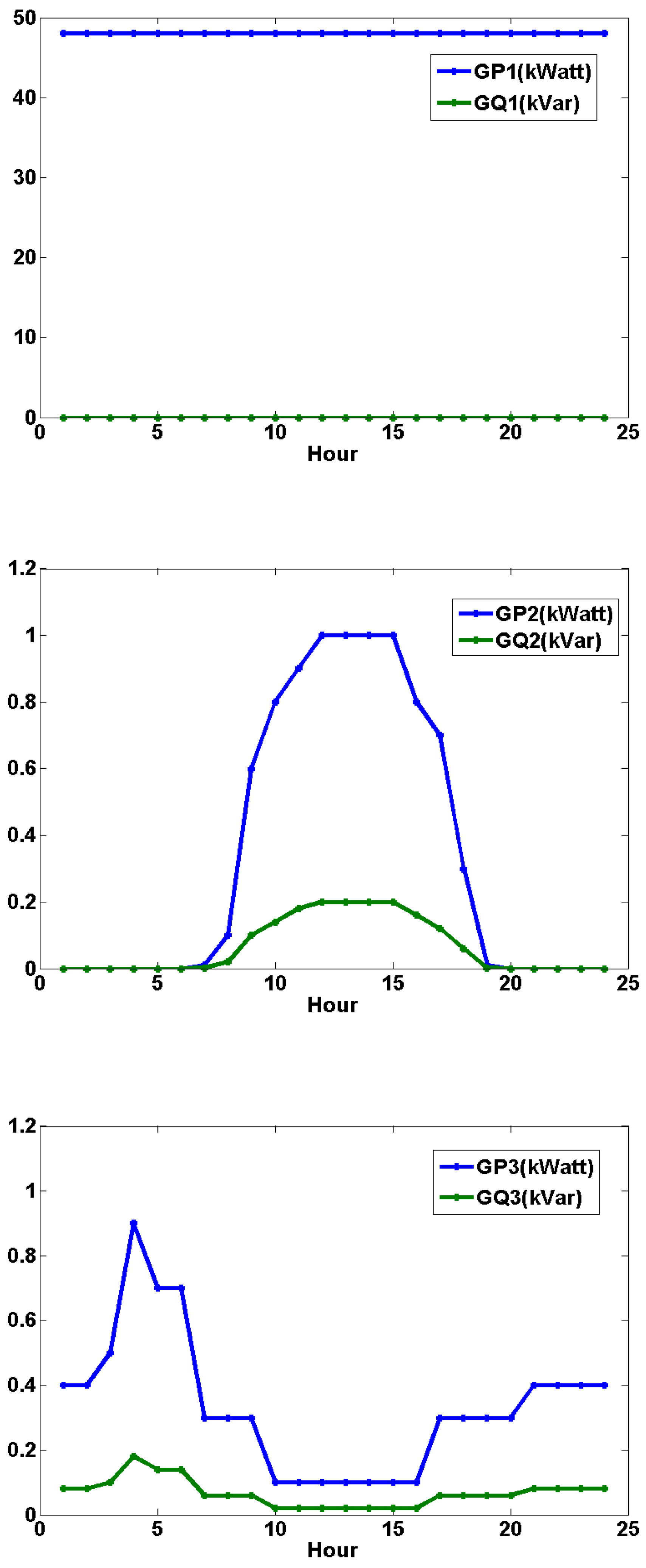

2.1.2. 24 Hour Dynamic Load Flow Analysis Based on the Newton-Raphson Method

3. Results and Discussion

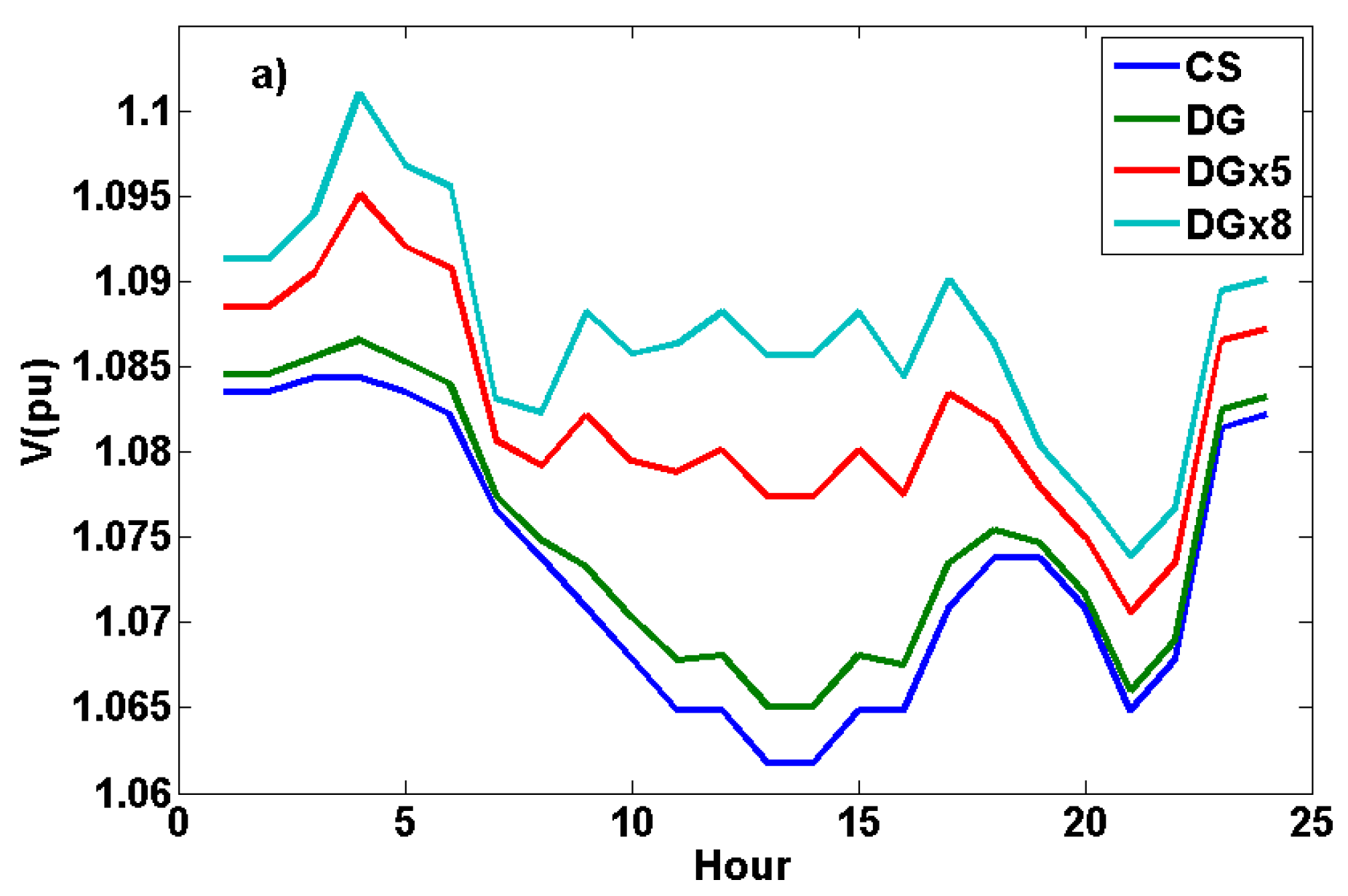

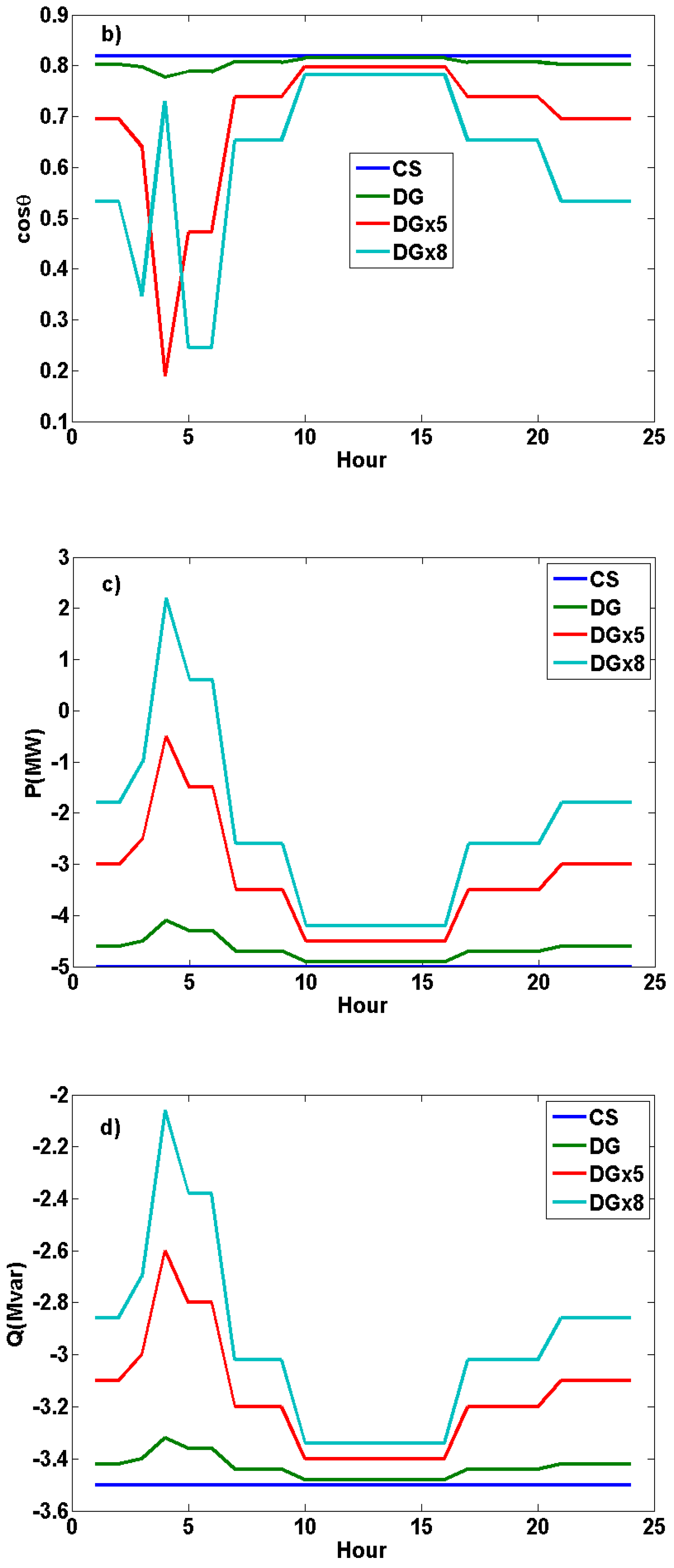

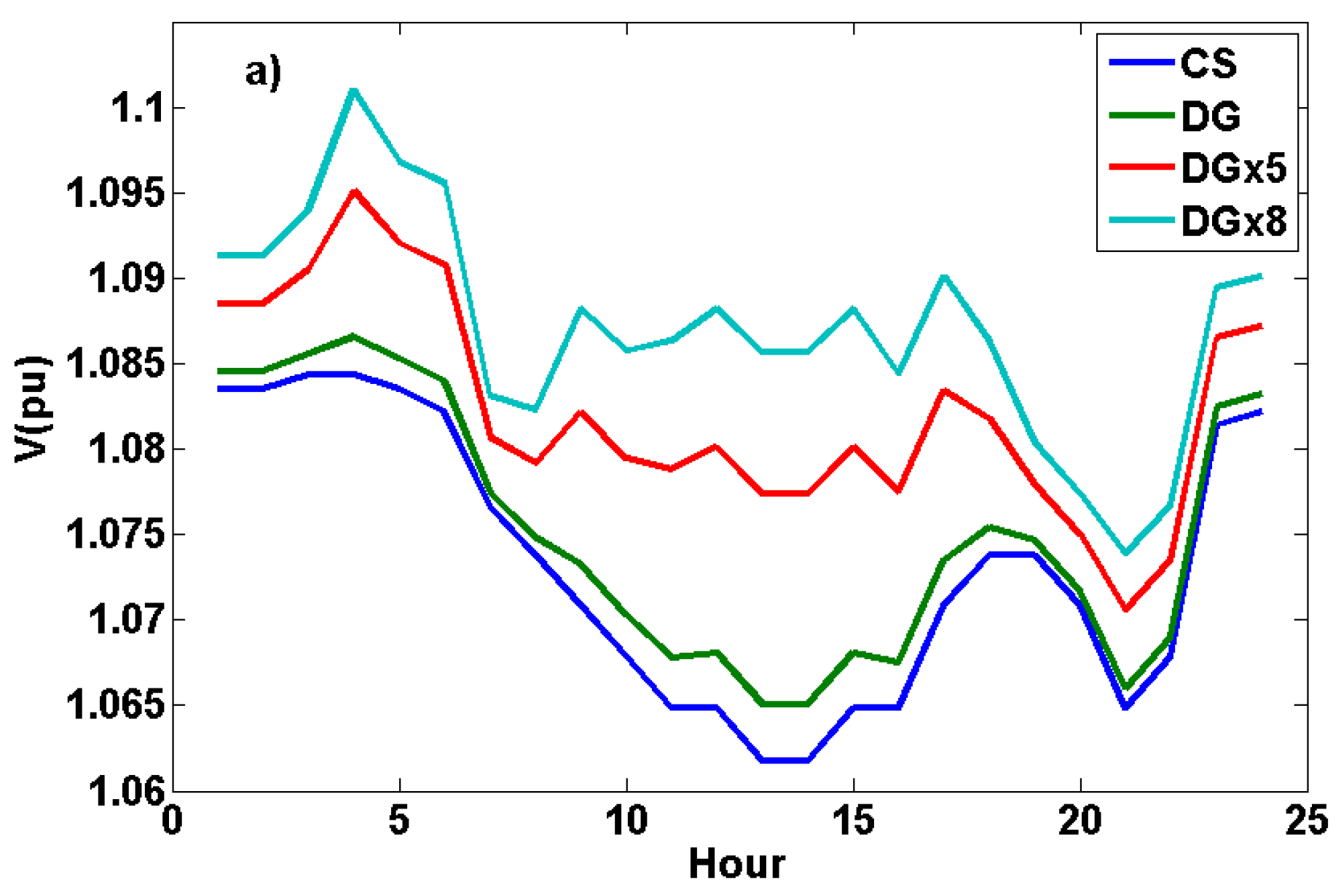

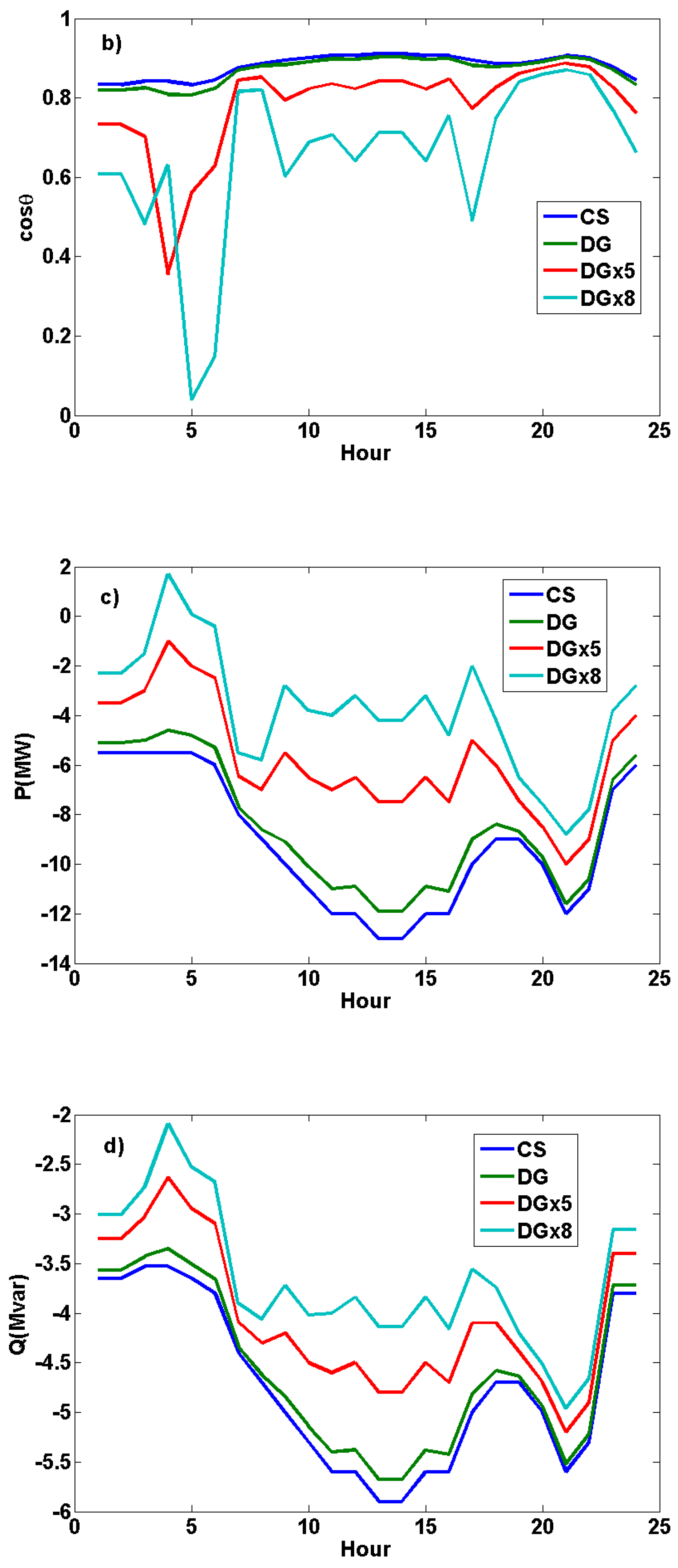

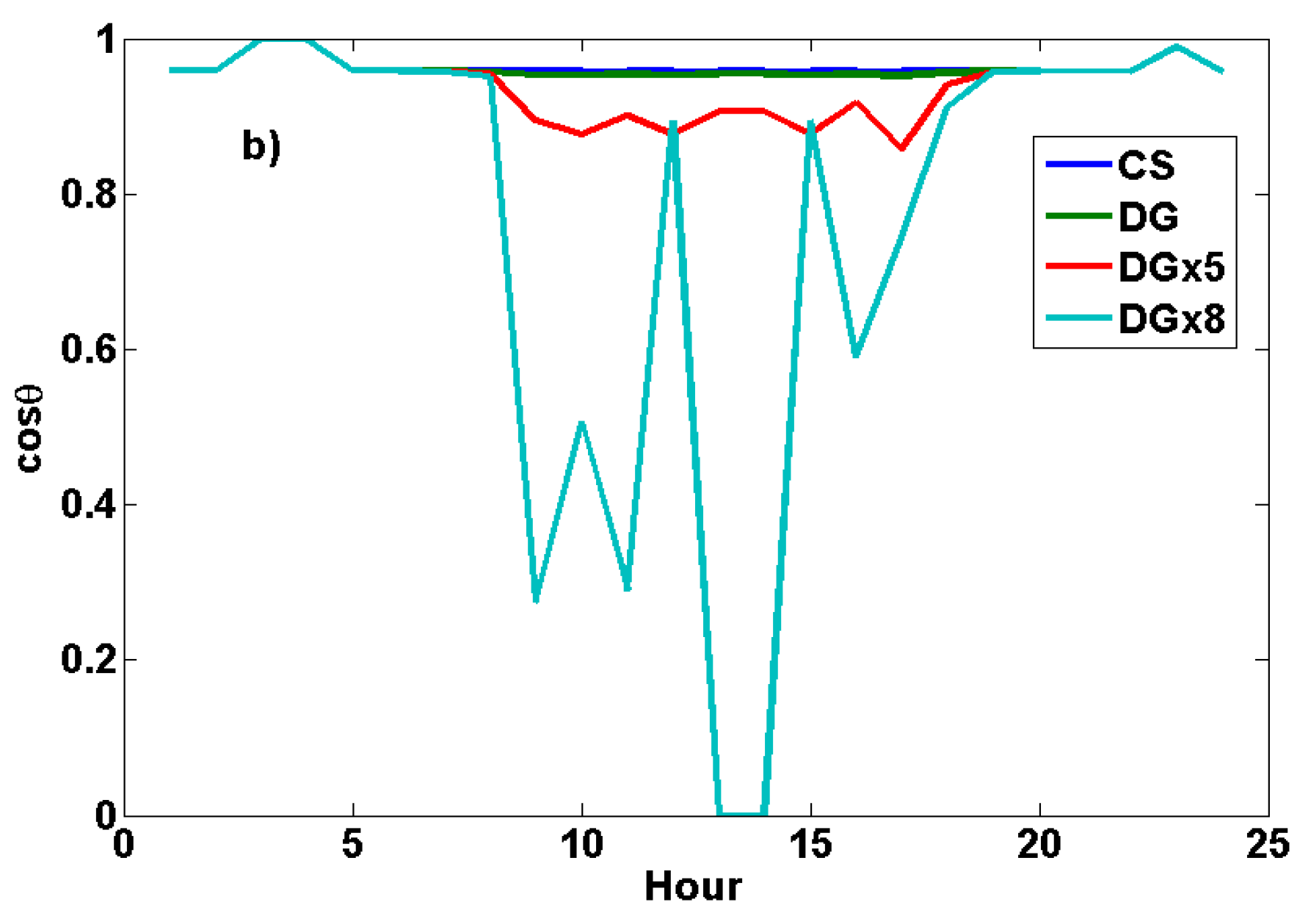

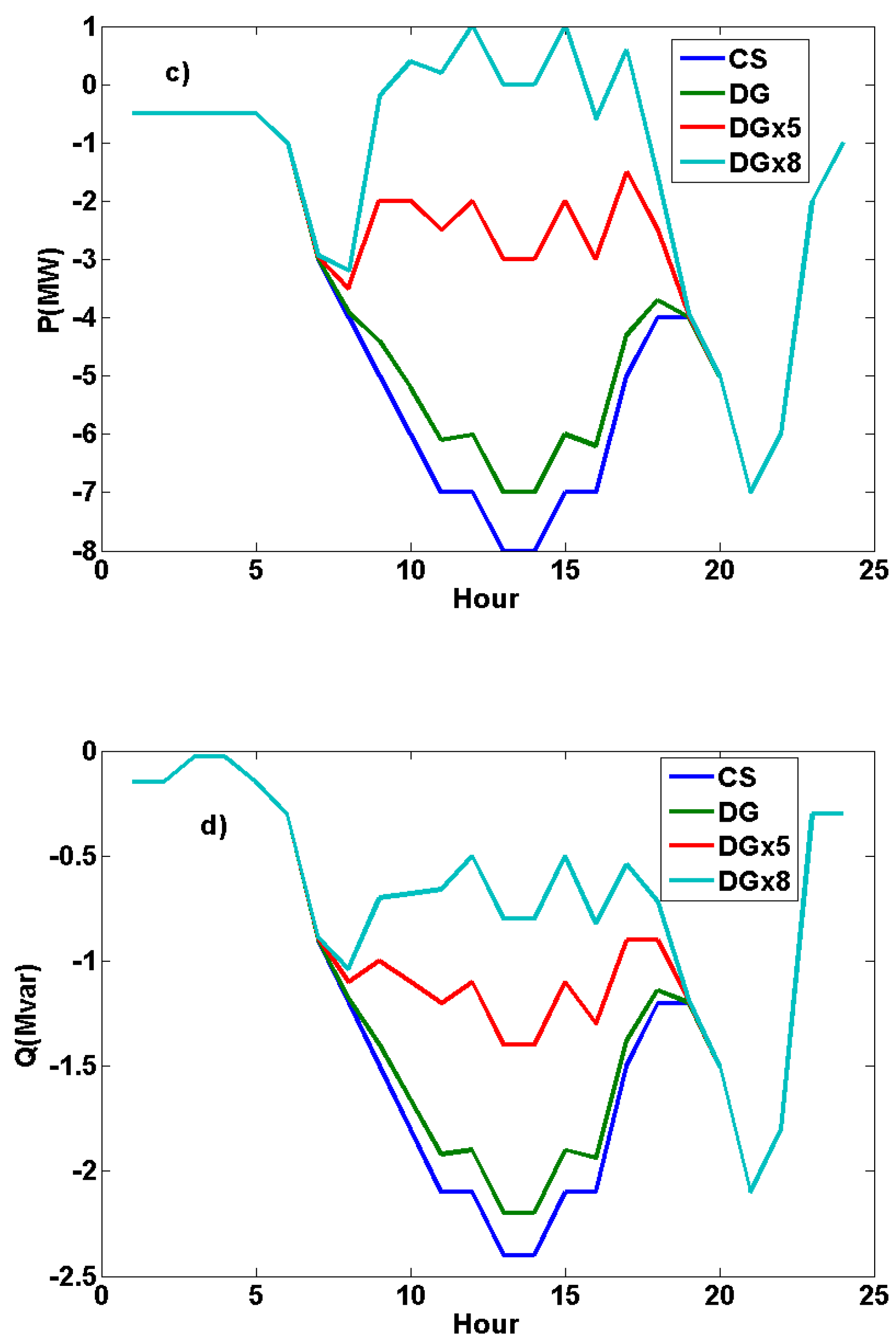

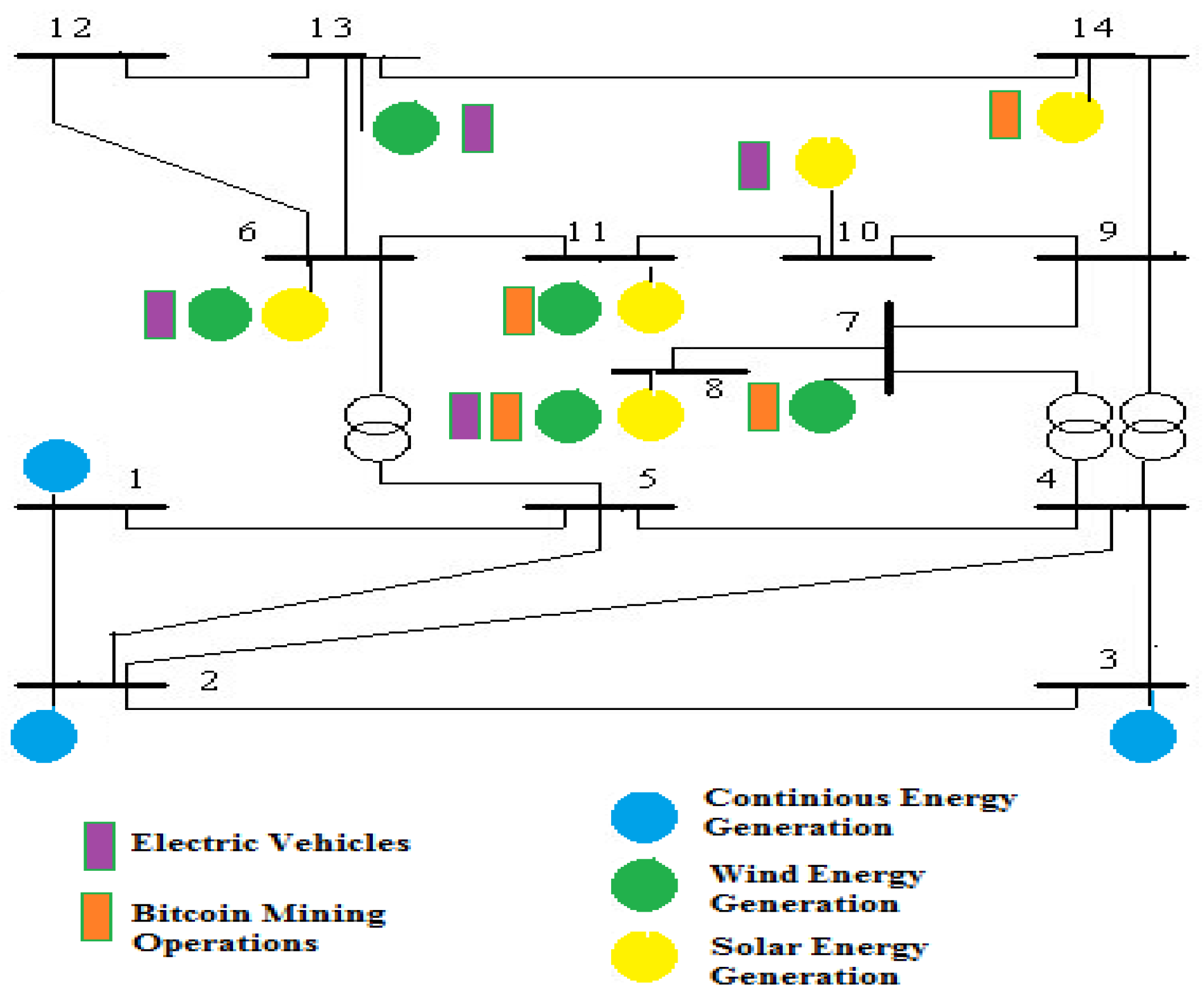

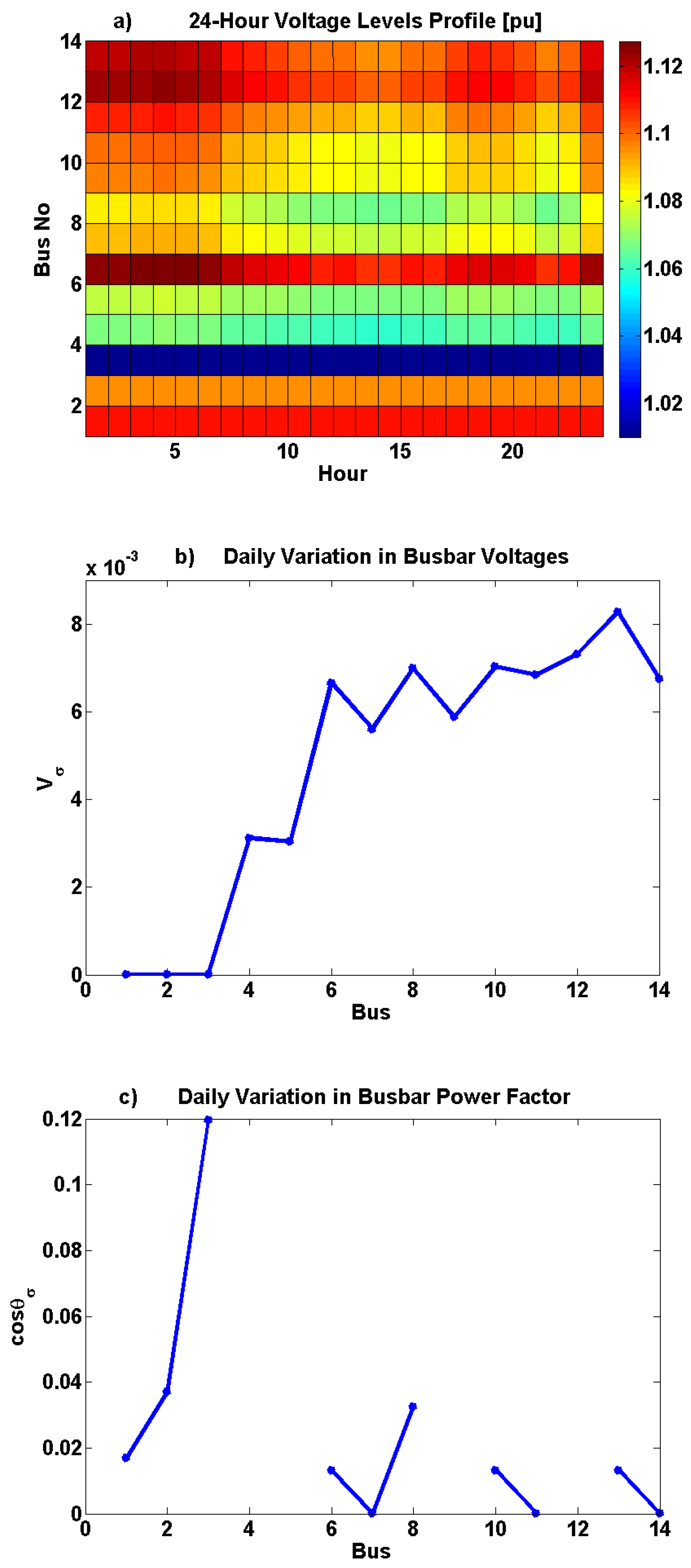

3.1. 24-Hour Dynamic Load Flow Analyses on the IEEE 14-Bus Test System

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Treiblmaier, H. A comprehensive research framework for Bitcoin’s energy use: Fundamentals, economic rationale, and a pinch of thermodynamics. Blockchain:Research and Applications, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, R.; Zare, S. G.; Gharehbaghi, A.; Nazari, S.; Weber, G-W. Robust optimization for energy-aware cryptocurrency farm location with renewable energy. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 2023, 177. [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Ji J.; Qin, X. Study on optimal configuration of EV charging stations based on second-order cone. Energy, 2023, 284. [CrossRef]

- Tabar, V.S.; Ghassemzadeh, S.; Tohidi, S. Risk-based day-ahead planning of a renewable multi-carrier system integrated with multi-level electric vehicle charging station, cryptocurrency mining farm and flexible loads. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2022 380(1). [CrossRef]

- Peças Lopes, J.A.; Hatziargyriou N.; Mutale, J.; Djapic, P.; Jenkins, N., Integrating distributed generation into electric power systems: A review of drivers, challenges and opportunities. Electric Power Systems Research, 2006, 7(9), pp.1189-1203. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Kim HS. ReviewChain: Smart Contract Based Review System with Multi-Blockchain Gateway. 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData); 2018.

- Wang, X.; Yang, W.; Noor, S.; Chen, C.; Guo, M.; Dam Khv. Blockchain-based smart contract for energy demand management, Energy Procedia, 2019, 168, 2719-2724. [CrossRef]

- Shafiei, M.; Ghasemi-Marzbali, A. Fast-charging station for electric vehicles, challenges and issues: a comprehensive review. J. Energy Storage, 2022, 49. [CrossRef]

- García-Villalobos, J.; Zamora, I.; San Martín, J.L.; Asensio F.J; Aperribay, V. Plug-in electric vehicles in electric distribution networks: A review of smart charging approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 717–731. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Calvo, A.; Cossent R.; Frías, P. Integration of PV and EVs in unbalanced residential LV networks and implications for the smart grid and advanced metering infrastructure deployment. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2017, 91, 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, N.; Peng, J.; Cui, H.; Wu, Z. Energy consumption of cryptocurrency mining: A study of electricity consumption in mining cryptocurrencies. Enegry, 2019, 168, 1189-1203. [CrossRef]

- Kaygusuz, A.; Gül, O.; Alagöz, B.B. An analysis for impacts of renewable distributed generation conditions on the load flow stability of electrical power system. EMO Bilimsel Dergi: Elektrik, Elektronik, Bilgisayar, Biyomedikal Mühendisliği Bilimsel Dergi. 2012, 2(4), 77-85.

- Tinney, W. F.; Hart, C. E. Power Flow Solution by Newton's Method, 1967, IEEE Trans. Power App. Syst., 86, 1449-1460.

- R. D. Zimmerman, R. D.; Chiang, H. D. Fast Decoupled Power Flow for Unbalanced Radial Distribution Systems, 1995 IEEE PES Winter Meeting, New York, 95, 1995.

- Stott B.; Alsaq, O. Fast Decoupled Load Flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Apparatus and Systems, 1974, 3, 859-869.

- Moorthy, S.; Al-Dabbagh, M.; Vawser, M. Improved Phase–Cordinate Gauss-Seidel Load Flow Algorithm,, 1995, Electric Power System Research, 34, 91- 95.

- Zang W.; Liu, Y. Reactive Power Optimization Based on PSO in a Partical Power System. Power Engineering Society General Meeting, 2004 IEEE, Denver, CO, USA, 2004, 1, 239-243.

- Vlachogiannis, J. Q. Fuzzy Logic Application in Load Flow Studies. IEE Proc. Generation, Transmission and Distribution, 2001, 148, 1, 34-40. [CrossRef]

- Storn R.; Price, K. Differential Evolution-a Simple and Efficient Heuristic for Global Optimization over Continuous Spaces, 1997, Journal of Global Optimization, 11, 341-359.

- Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Liu, Y. Distributed Reactive Power Optimization and Programming for Area Power System. International Conference on Power System Technology, POWERCOM 2004, Singapore, 2004, 2, 1447-1450.

- Wei, H.; Cong, Z.; Jingyan, Y.; Jianhua, Z.; Zifa, L.; Zhilian, W.; Dongli, P. Using Bacterial Chemotaxis Method for Reactive Power Optimization. 2008 IEEE/PES Transmission and Distribution Conference and Exposition, Chicago, Illinois, USA, April 2008, 1-7.

- Shirmohammadi, D.; Hong, H. W. ; Semlyen, A.; Luo, G. X. Compensation-Based Power Flow Method for Weakly Meshed Distribution and Transmission Networks. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 1988, 3, 753-762.

- Absar, M. N.; Islam, M. F.; Ahmed, A. Power quality improvement of a proposed grid-connected hybrid system by load flow analysis using static var compensator, Heliyon, 2023, 9(7). [CrossRef]

- Saadat, H. Power Systems Analysis, McGraw Hill, Boston, 1999.

- Bayat, M.; Koushki, M. M.; Ghadimi, A. A.; Véliz, M. T.; Jurado, F. Comprehensive enhanced Newton Raphson approach for power flow analysis in droop-controlled islanded AC microgrids. 2022, International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 143. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Xin Li, G.; Zhng, C. False data injection in power smart grid and identification of the most vulnerable bus; a case study 14 IEEE bus network. Energy Reports, 2021,7, 8476-8484. [CrossRef]

|

Bus No |

Vσ(CS--LDx3--LDx7) | cosθσ(CS--LDx3--LDx7) |

| 1 | %0--%0--%0 | %1.6--%13--%68 |

| 2 | %0--%0--%0 | %3.6--%16--%98 |

| 3 | %0--%0--%0 | %12--%50--%30 |

| 4 | %0.35--%2--%10.6 | %--%--%-- |

| 5 | %0.32--%2.5--%11.2 | %--%--%-- |

| 6 | %0.7--%4.6--%8.3 | %1.3--%1.3--%1.3 |

| 7 | %0.6--%4.3--%51.7 | %0.01--%0.01--%0.01 |

| 8 | %0.7--%5.2--%22.05 | %3.2--%3.2--%3.2 |

| 9 | %0.6--%4.4--%32.57 | %--%--%-- |

| 10 | %0.7--%5--%7.89 | %1.3--%1.3--%1.3 |

| 11 | %0.68--%5--%6.89 | %0.01--%0.01--%0.01 |

| 12 | %0.77--%4.9--%8.8 | %--%--%-- |

| 13 | %0.87--%5.36--%31.3 | %1.3--%1.3--%1.3 |

| 14 | %0.75--%5.16--%31.4 | %0.01--%0.01--%0.01 |

|

Bus No |

Vσ(DG—DGx5—DGx8) | cosθσ(DG—DGx5—DGx8) |

| 1 | %0--%0--%0 | %1.5--%1.3--%1.3 |

| 2 | %0--%0--%0 | %3.3--%2.5--%2.5 |

| 3 | %0--%0--%0 | %9.8--%6.0--%5.8 |

| 4 | %0.31--%0.26--%0.27 | %--%--%-- |

| 5 | %0.30--%0.25--%0.26 | %--%--%-- |

| 6 | %0.66--%0.56--%0.56 | %21.8--%32.5--%16.4 |

| 7 | %0.56--%046--%0.48 | %1.2--%20--%26.3 |

| 8 | %0.69--%0.58--%059 | %3.9--%15.4--%31.2 |

| 9 | %0.58--%0.48--%0.49 | %--%--%-- |

| 10 | %0.70--%0.56--%0.59 | %1.4--%4.3--%41.2 |

| 11 | %0.68--%0.57--%0.63 | %2--%59.5--%36.6 |

| 12 | %0.73--%0.62--%0.62 | %--%--%-- |

| 13 | %0.82--%0.72--%0.71 | %21.3--%21.3--%3.8 |

| 14 | %0.67--%0.54--%0.63 | %2.5--%55.5--%27.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).