Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

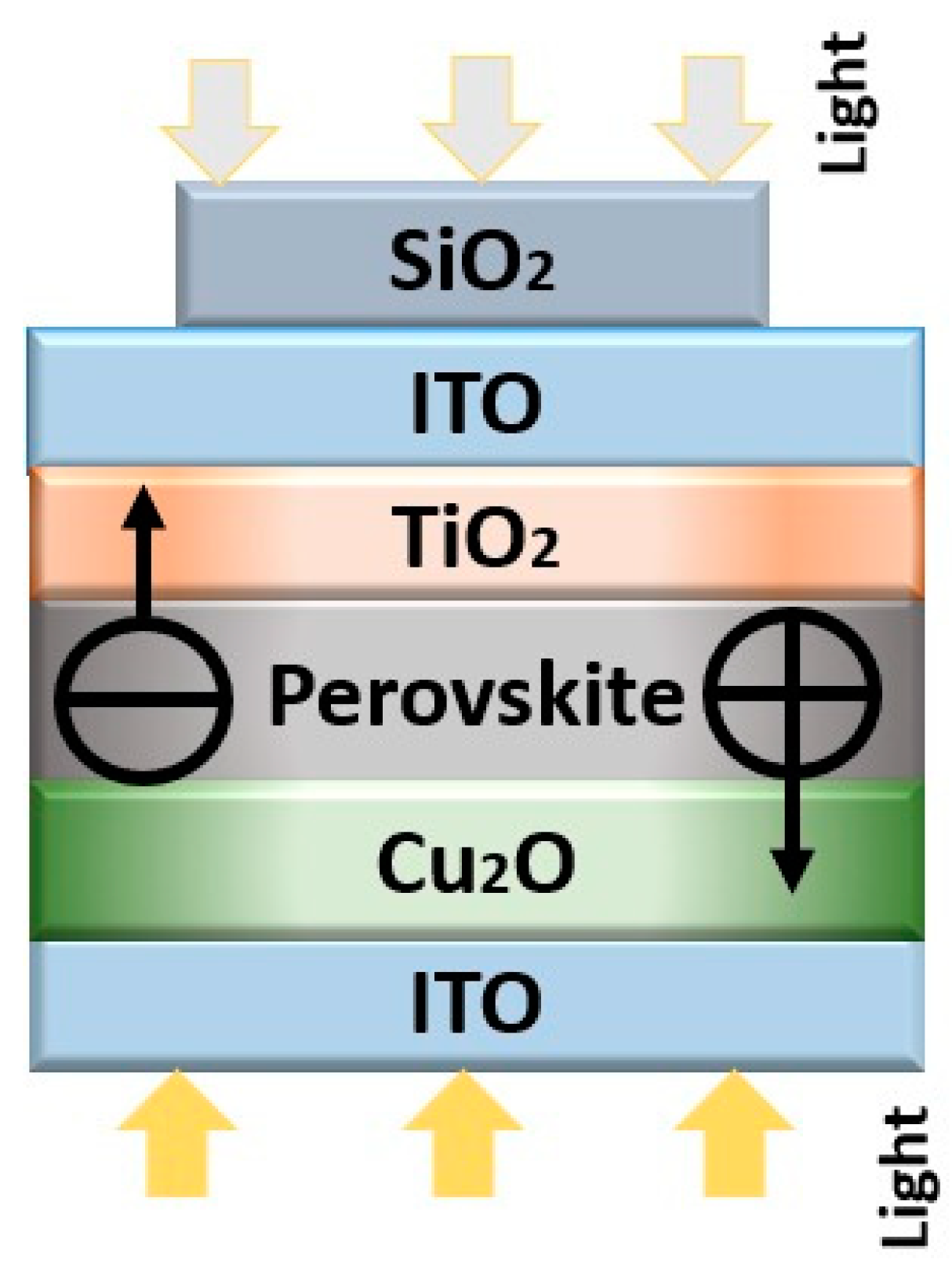

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

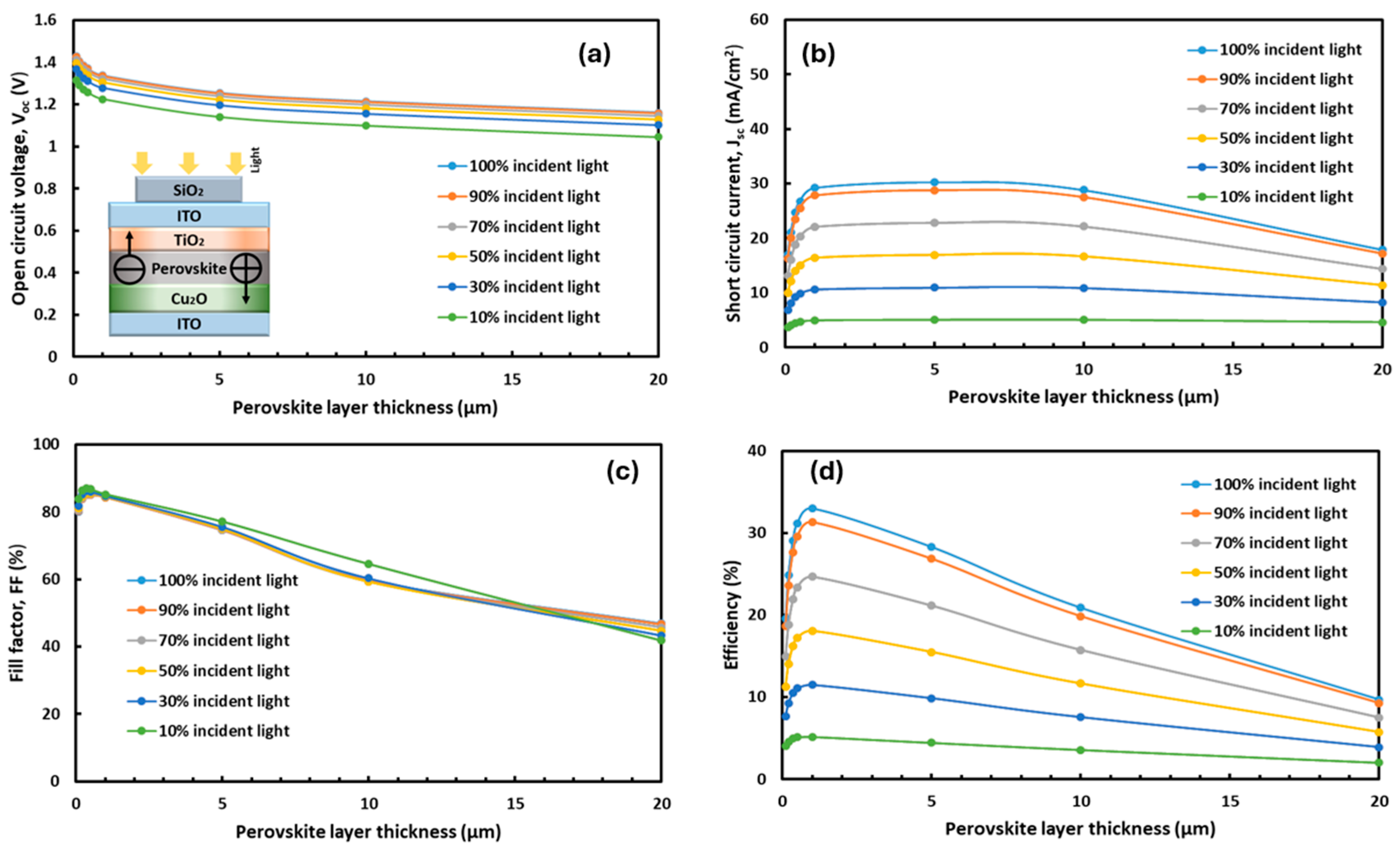

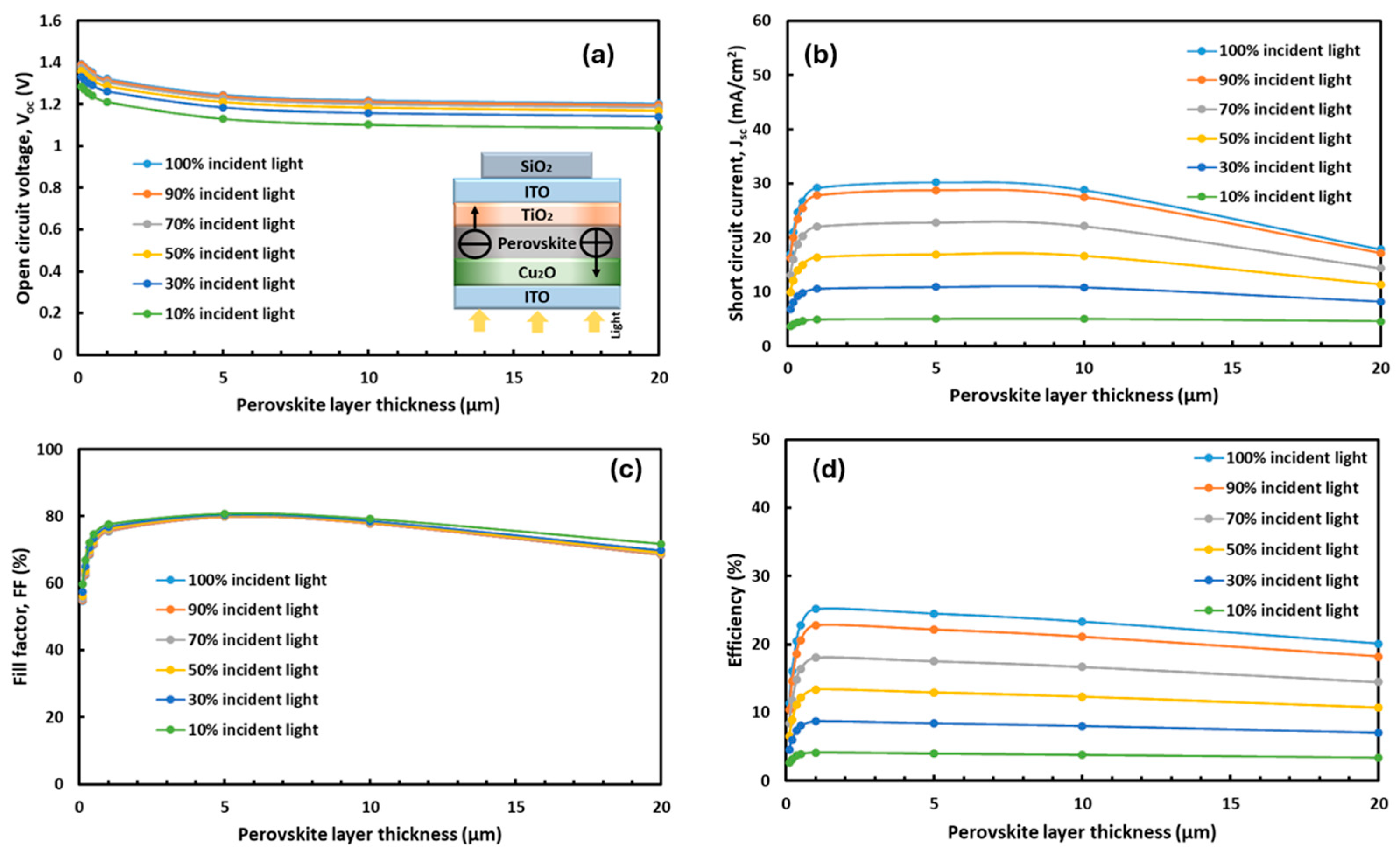

3.1. Layer Thickness Optimization

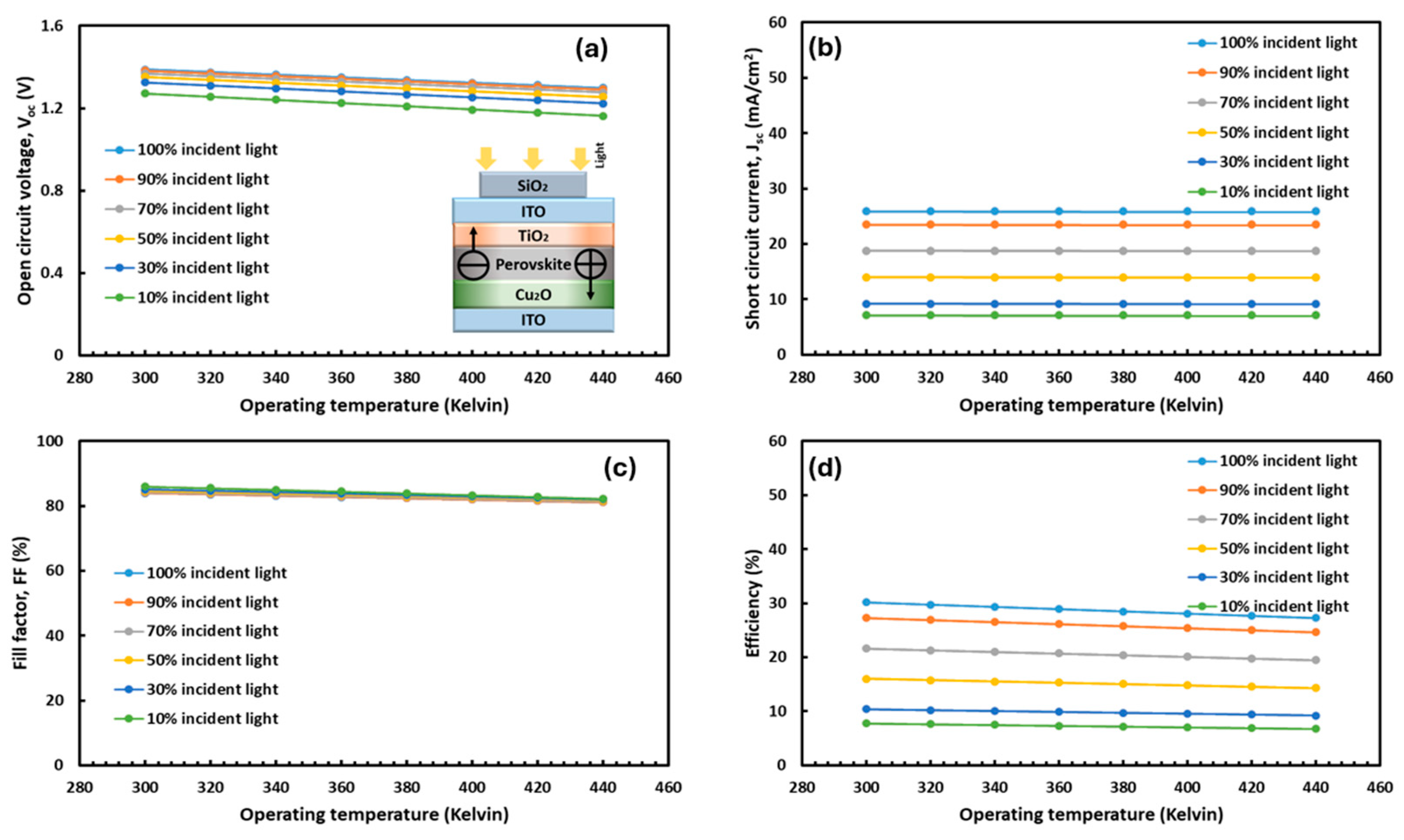

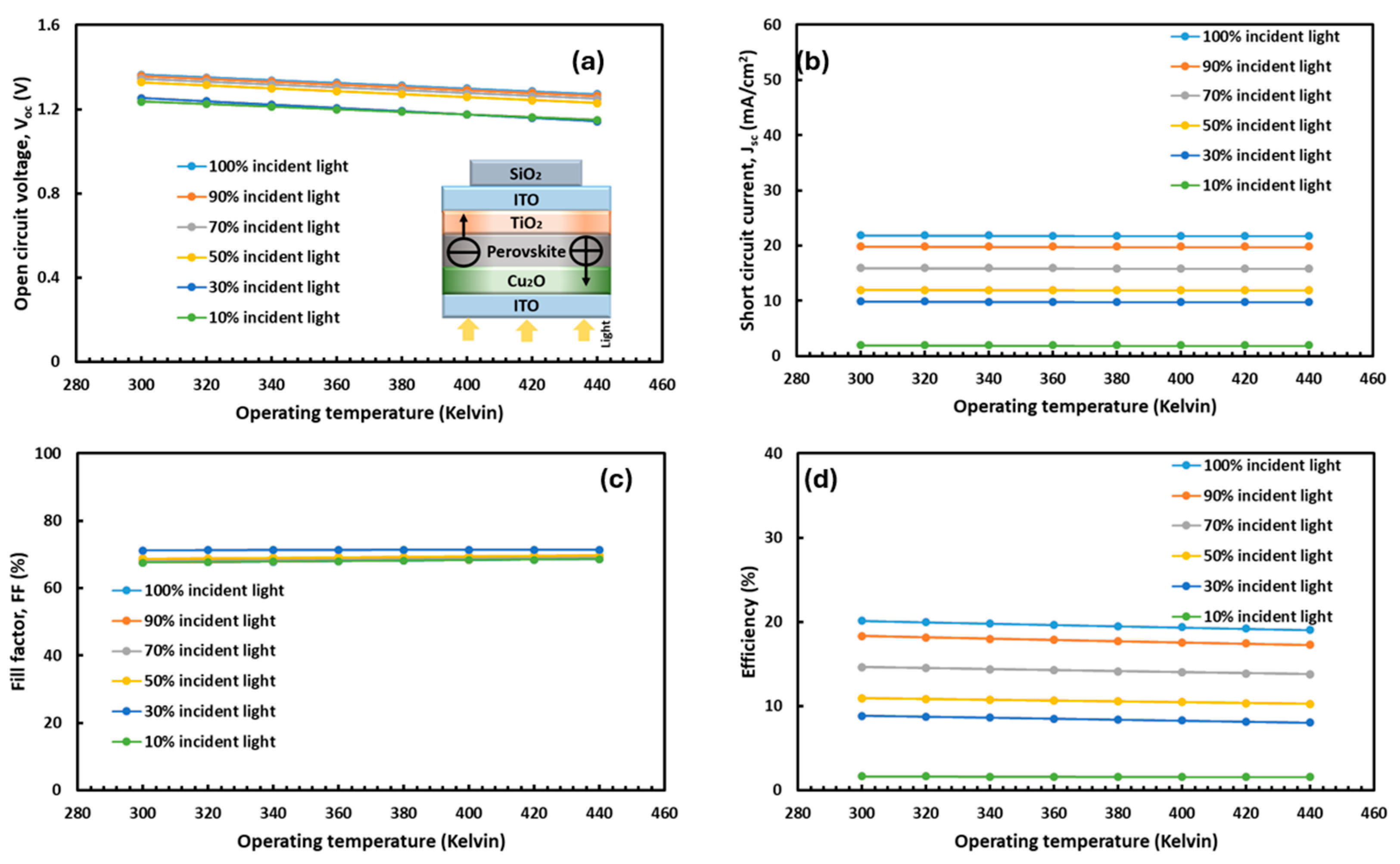

3.2. Effects of Operating Temperature on Bifacial Solar Cells

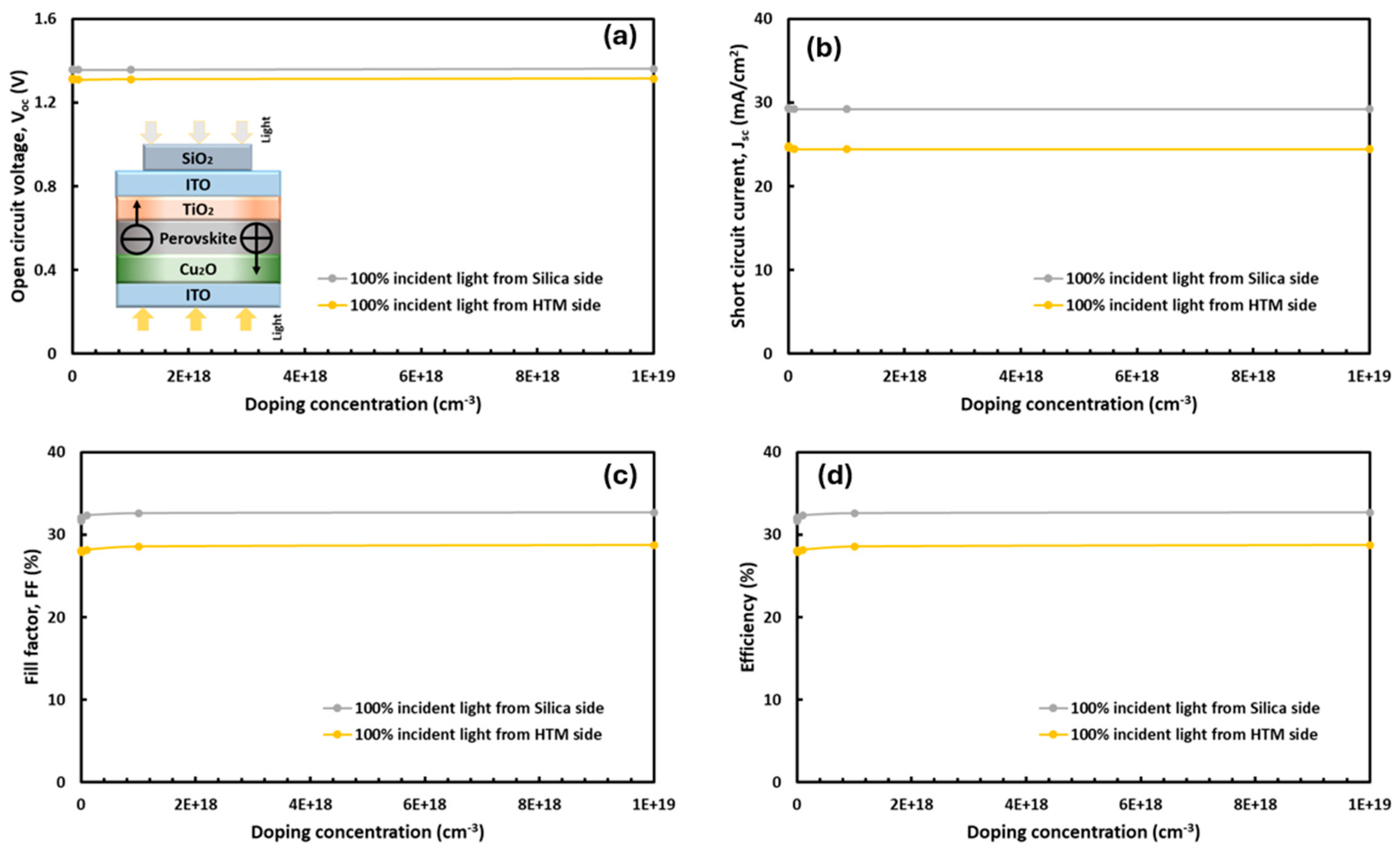

3.3. Effects of Doping Concentration on TiO2 Electron Transport Layer Layers

4. Discussion

4.1. Layer Thickness Optimization

4.2. Effects of Operating Temperature on Bifacial Solar Cells

4.3. Effects of Doping Concentration on TiO2 Electron Transport Layer Layers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grätzel, M. 2014. "The light and shade of perovskite solar cells." Nature Materials, 13: 838-842.

- Hossain, M. I., Tong, Y., Shetty, A., & Mansour, S. 2023. "Probing the degradation pathways in perovskite solar cells." Solar Energy, 265: 112128.

- M. I. Hossain, "E-beam evaporated hydrophobic metal oxide thin films as carrier transport materials for large scale perovskite solar cells.," Materials Technology, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 248-259, 2022.

- Aïssa, B., Bufere, M., & Hossain, M. I. 2023. "Solar cell technologies." In Photovoltaic Technology for Hot and Arid Environments, Institution of Engineering and Technology, 59-109.

- Noorasid, N. S., et al. 2023. "Improved performance of lead-free perovskite solar cell incorporated with TiO₂ ELECTRON TRANSPORT LAYER and CuI HOLE TRANSPORT LAYER using SCAPs." Applied Physics, 129(2): 132.

- Liang, M., et al. 2020. "Improving stability of organometallic-halide perovskite solar cells using exfoliation two-dimensional molybdenum chalcogenides." npj 2D Materials and Applications, 4(1).

- Wang, E., Chen, P., Yin, X., Gao, B., & Que, W. 2018. "Boosting efficiency of planar heterojunction perovskite solar cells by a low temperature TiCl₄ treatment." Journal of Advanced Dielectrics, 8: 1850009.

- Ghosh, P., Sundaram, S., Nixon, T. P., & Krishnamurthy, S. 2021. "Influence of nanostructures in perovskite solar cells." Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering. Elsevier.

- Wang, D. L. 2016. "Highly efficient light management for perovskite solar cells." Scientific Reports, 6.

- Yoo, G. Y. 2020. "Broadband anti-reflective nanostructures by coating a low-index MgF₂ film onto a SiO₂ moth-eye nanopattern." ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 12.

- Zhao, P. 2018. "Device simulation of organic-inorganic halide perovskite/crystalline silicon four-terminal tandem solar cell with various antireflection materials." IEEE J. Photovoltaics.

- Arabatzis, I. 2018. "Photocatalytic, self-cleaning, anti-reflective coating for photovoltaic panels: characterization and monitoring in real conditions." Solar Energy.

- Hossain, M. I., Chelvanathan, P., Al Kubaisi, G., & Mansour, S. 2023. “Experimental and Numerical Study of Different Metal Contacts for Perovskite Solar Cells.” Cogent Engineering, 10(1): 2189502.

- Elumalai, N. K., & Uddin, A. 2016. "Hysteresis in organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells." Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells.

- Lin, L., Jiang, L., Li, P., Fan, B., & Qiu, Y. 2019. "A modeled perovskite solar cell structure with a Cu2O hole-transporting layer enabling." J. Phys. Chem. Solids, 205-211.

- Mechole transport layery, E. A. 2002. "Properties of Materials." In Reference Data for Engineers. Elsevier.

- Song, Z., Li, C., Chen, L., & Yan, Y. 2022. “Perovskite Solar Cells Go Bifacial—Mutual Benefits for Efficiency and Durability.” Advanced Materials, 34(4): 2106805.

- Kumar, P., Shankar, G., & Pradhan, B. 2023. “Recent Progress in Bifacial Perovskite Solar Cells.” Applied Physics A, 129(1): 63.

- Afzaal, M., & Karkain, S. 2022. “Environmental Assessment of Perovskite Solar Cells.” In The Effects of Dust and Heat on Photovoltaic Modules: Impacts and Solutions, edited by A. Al-Ahmed et al., 279–289. Springer.

- Bal, S. S., Basak, A., & Singh, U. P. 2022. “Numerical Modeling and Performance Analysis of Sb-Based Tandem Solar Cell Structure Using SCAPS–1D.” Optical Materials, 127: 112282.

- Baloch, A. A. B., Hossain, M. I., Tabet, N., & Alharbi, F. H. 2018. “Practical Efficiency Limit of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite (CH₃NH₃PbI₃) Solar Cells.” Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 9(2): 426–434.

- Belarbi, M., Zeggai, O., & Louhibi-Fasla, S. 2022. “Numerical Study of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cells Using SCAPS-1D Simulation Program.” Materials Today: Proceedings. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Mohammad Istiaque, Brahim Aissa, Ayman Samara, Said A. Mansour, Cedric A. Broussillou, and Veronica Bermudez Benito. "Hydrophilic antireflection and antidust silica coatings." ACS omega 6, no. 8 (2021): 5276-5286.

- Hossain, M. I., Bousselham, A., Alharbi, F. H., & Tabet, N. 2017. “Computational Analysis of Temperature Effects on Solar Cell Efficiency.” Journal of Computational Electronics, 16: 776–786.

- Hossain, M. I., & Aïssa, B. 2017. “Effect of Structure, Temperature, and Metal Work Function on Performance of Organometallic Perovskite Solar Cells.” Journal of Electronic Materials, 46(3): 1806–1810.

- Khattak, Y. H., Vega, E., Baig, F., & Soucase, B. M. 2022. “Performance Investigation of Experimentally Fabricated Lead Iodide Perovskite Solar Cell via Numerical Analysis.” Materials Research Bulletin, 151: 111802.

- Michaelson, H. B. 1977. “The Work Function of the Elements and Its Periodicity.” Journal of Applied Physics, 48: 191911.

- Nath, B., Ramamurthy, P. C., Mahapatra, D. R., & Hegde, G. 2022. “Electrode Transport Layer-Metal Electrode Interface Morphology Tailoring for Enhancing the Performance of Perovskite Solar Cells.” ACS Applied Electronic Materials. [CrossRef]

- Nath, B., Ramamurthy, P. C., Hegde, G., & Mahapatra, D. R. 2022. “Role of Electrodes on Perovskite Solar Cells Performance: A Review.” ISSS Journal of Micro and Smart Systems. [CrossRef]

- Raza, E., et al. 2022. “Numerical Modeling and Performance Optimization of Carbon-Based Hole transport layer-Free Perovskite Solar Cells.” Optical Materials, 125: 112075.

- Saha, P., Halder, P., Singh, S., & Bhattacharya, S. 2024. “Optimization and Formulation of Different Hole-Transporting Materials (HTMs) for the Performance of Eco-Friendly Cs₂TiBr₆-Based Perovskite Solar Cells.” Energy Technology, 12(3): 2300991.

- Saha, P., Singh, S., & Bhattacharya, S. 2023. “Eco-Friendly Methyl-Ammonium Tin-Based Planar P–N Homojunction Perovskite Solar Cells: Design and Performance Estimation.” International Journal of Modern Physics B, 37(17): 22350169.

- Samantaray, M. R., Rana, N. K., Kumar, A., Ghosh, D. S., & Chander, N. 2022. “Stability Study of Large-Area Perovskite Solar Cells Fabricated with Copper as Low-Cost Metal Contact.” International Journal of Energy Research, 46(2): 1250–1262.

- Shiraishi, M., & Ata, M. 2001. “Work Function of Carbon Nanotubes.” Carbon, 39: 1913–17.

- Song, S. M., Park, J. K., Sul, O. J., & Cho, B. J. 2012. “Determination of Work Function of Graphene under a Metal Electrode and Its Role in Contact Resistance.” Nano Letters, 12: 3887–3892.

- Wang, M., et al. 2022. “Modular Perovskite Solar Cells with Cs₀.₀₅ (FA₀.₈₅MA₀.₁₅)₀.₉₅ Pb (I₀.₈₅Br₀.₁₅)₃ Light-Harvesting Layer and Graphene Electrode.” Journal of Electronic Materials, 51(5): 2381–2389.

- Wu, Y., et al. 2022. “Broad-Band-Enhanced Plasmonic Perovskite Solar Cells with Irregular Silver Nanomaterials.” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Layer used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | SiO2 | Cu2O | Perovskite | |

| Bandgap(eV) | 3.260 | 6.300 | 2.200 | 1.500 |

| Electron Thermal Velocity(cm/s) | 1.007E+7 | 1.007E+7 | 1.007E+7 | 1.007E+7 |

| Electron affinity(eV) | 4.000 | 3.200 | 3.200 | 3.900 |

| Dielectric permittivity | 10.000 | 3.900 | 9.400 | 10.000 |

| CB(1/cm3) | 2.00E+18 | 2.02E+17 | 8.00E+17 | 2.00E+18 |

| VB(1/cm3) | 1.80E+18 | 1.20E+19 | 1.80E+19 | 1.80E+18 |

| Electron Mobility(cm2/Vs) | 2.000E+2 | 6.250E+1 | 2.000E+2 | 2.000E+2 |

| Hole Thermal Velocity(cm/s) | 1.000E+2 | 1.000E+2 | 1.000E+7 | 1.000E+2 |

| Hole Mobility(cm2/Vs) | 2.500E+1 | 0.800 E+1 | 1.000E+2 | 1.000E+1 |

| CB(1/cm3) | 2.00E+18 | 2.02E+17 | 8.00E+17 | 2.00E+18 |

| VB(1/cm3) | 1.800E+18 | 1.10E+19 | 1.800E+19 | 1.800E+18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).