Submitted:

19 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Tumor diseases represent a significant global health challenge, impacting both humans and companion animals, notably dogs. The parallels observed in the pathophysiology of cancer between humans and dogs underscore the importance of advancing comparative oncology and translational research methodologies. Moreover, dogs serve as valuable models for human cancer research due to shared environments, genetics, and treatment responses. Notably, breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) and breast cancer gene 2 (BRCA2), which are pivotal in human oncology, also influence the development and progression of canine tumors. The role of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in canine cancers remains underexplored, but their potential significance as therapeutic targets is strongly considered. This systematic review aims to broaden the discussion of BRCA1 and BRCA2 beyond mammary tumors, exploring their implications across various canine cancers. By emphasizing shared genetic underpinnings between species and advocating for a comparative approach, the review indicates the potential of BRCA genes as targets for innovative cancer therapies in dogs, contributing to advancements in both human and veterinary oncology.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Main Text

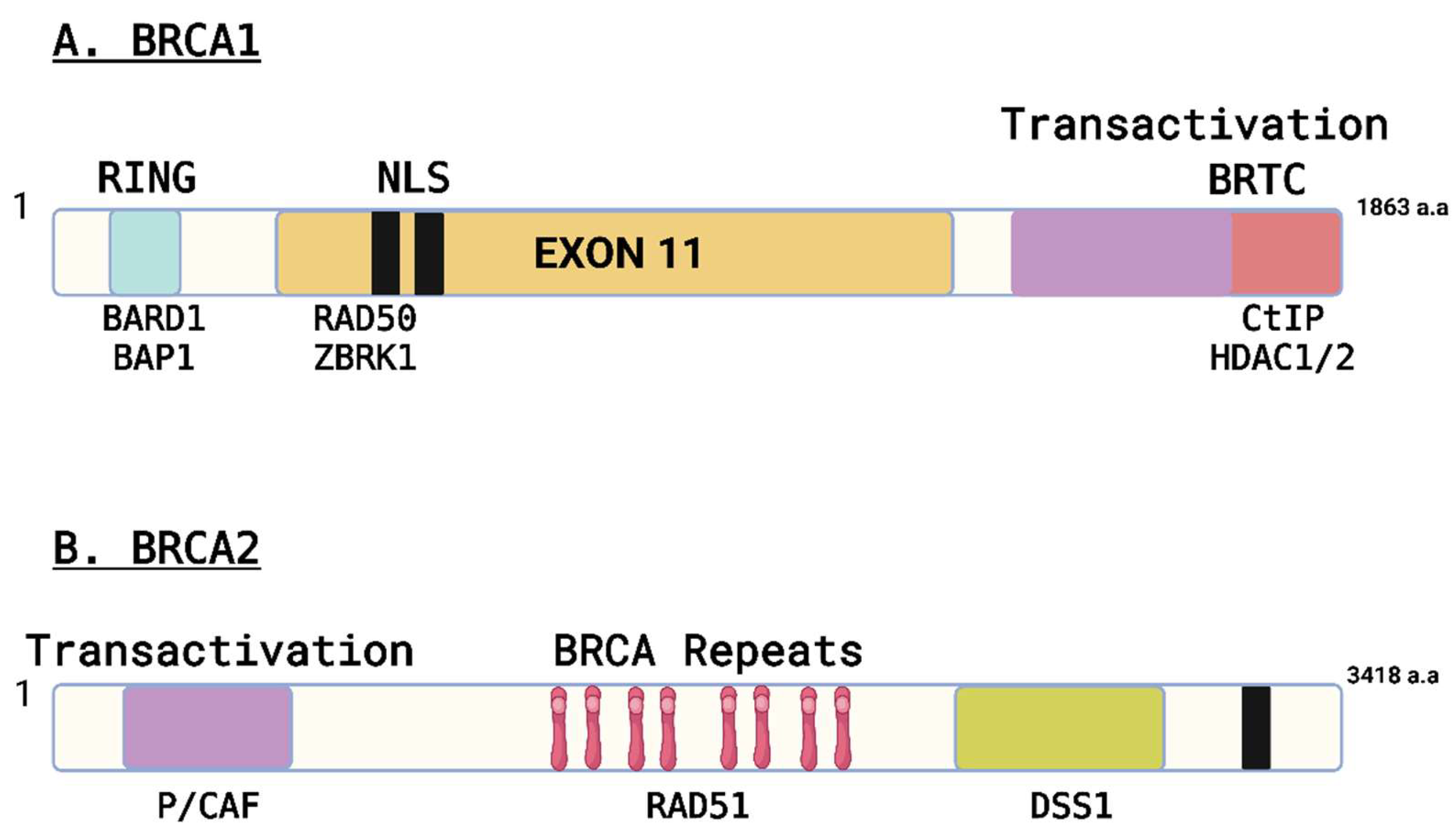

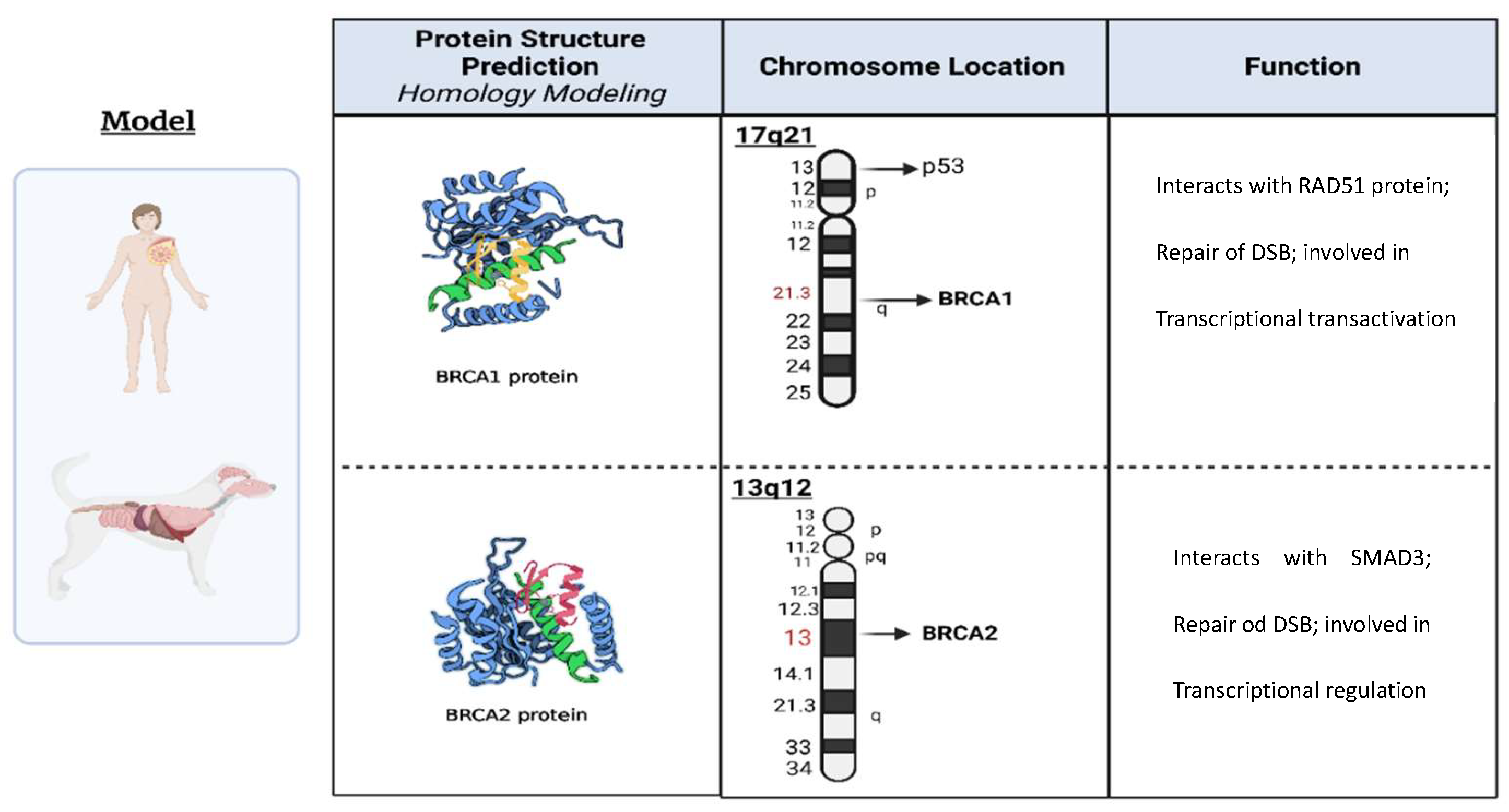

3.1. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Structural, Biological and Molecular Functions

3.2. Molecular and Biological Functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in Cancer: A Comparative View Between Humans and Canines

3.3. Targeting BRCA1 and BRCA2 Using PARP Inhibitors (PARPi) for Personalized Therapies

3.4. Advancing BRCA-Targeted Therapies in Veterinary Oncology

4. Conclusion and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, V.; Evans, K.M.; Sampson, J.; et al. Methods and mortality results of a health survey of purebred dogs in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 2010, 51, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.E. Naturally Occurring Cancers in Dogs: Insights for Translational Genetics and Medicine. ILAR Journal 2014, 55, 16–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnesen, K.; Glattre, E.; Grøndalem, J.; et al. The Norwegian canine cancer register 1990–1998. Report from the Project “Cancer in dog”. EJCAP 2001, 11, 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Audeh, M.W.; Carmichael, J.; et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertwistle, D.; Swift, S.; Marston, N.J.; et al. Nuclear location and cell cycle regulation of the BRCA2 protein. Cancer Research 1997, 57, 5485–5488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Ear, U.S.; Koller, B.H.; et al. The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is required for subnuclear assembly of Rad51 and survival following treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin. J Biol Chem 2000, 275, 23899–23903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochar, D.; Wang, L.; Beniya, H.; et al. BRCA1 Is Associated with a Human SWI/SNF-Related Complex Linking Chromatin Remodeling to Breast Cancer. Cell 2000, 102, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, B.N.; Egenvall, A.; Hedhammar, A.; Olson, P. Mortality in over 350,000 insured Swedish dogs from 1995-2000: I. Breed-, gender-, age- and cause-specific rates. Acta Vet Scand 2005, 46, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borge, K.S.; Lingaas, F.; et al. Identification of genetic variation in 11 candidate genes of canine mammary tumour. Vet Comp Oncol 2011, 9, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; Amend, S.R.; Austin, R.H.; et al. Updating the Definition of Cancer. Mol Cancer Res 2023, 21, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, H.E.; Thomas, H.D.; Parker, K.M.; et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature 2005, 434, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrum, A.K.; Vindigni, A.; Mosammaparast, N. Defining and Modulating ’BRCAness’. Trends in Cell Biology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadieu, E.; Ostrander, E.A. Canine genetics offers new mechanisms for the study of human cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007, 16, 2181–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caestecker, K.W.; Van de Walle, G.R. The role of BRCA1 in DNA double-strand repair: past and present. Experimental Cell Research 2013, 319, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalasani, P.; Livingston, R.B. Differential chemotherapeutic sensitivity for breast tumors with “BRCAness”: A review. The Oncologist 2013, 18, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, E.; Sakthikumar, S.; Tang, M.; et al. Novel genomic prognostic biomarkers for dogs with cancer. J Vet Intern Med 2023, 37, 2410–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, E.; Wang, G.; Whitley, D.; et al. Genomic tumor analysis provides clinical guidance for the management of diagnostically challenging cancers in dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2023, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bono, J.R.; Mina, L.; Chugh, R.; et al. Phase I, dose-escalation, two-part trial of the PARP inhibitor talazoparib in patients with advanced germline BRCA1/2 mutations and selected sporadic cancers. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Brodie, S.G. Roles of BRCA1 and its interacting proteins. BioEssays 2000, 22, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Scott, F. Role of the tumor suppressor gene Brca1 in genetic stability and mammary gland tumor formation. Oncogene 2000, 19, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J.M. Breed-predispositions to cancer in pedigree dogs. ISRN 2013, 41275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wang, S. Exploring the cancer genome in the era of next-generation sequencing. Frontiers of Medicine 2012, 6, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dréan, A.; Lord, C.J.; Ashworth, A. PARP inhibitor combination therapy. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 2016, 108, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, D.F.; Steele, L.; Fields, P.; et al. Cancer risks in two large breast cancer families linked to BRCA2 on chromosome 13q12-13. American Journal of Human Genetics 1997, 61, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egenvall, A.; Bonnett, B.N.; Hedhammar, A.; Olson, P. Mortality in over 350,000 insured Swedish dogs from 1995-2000: II. Breed-specific age and survival patterns and relative risk for causes of death. Acta Vet Scand 2005, 46, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egenvall, A.; Bonnett, B.N.; Ohagen, P.; et al. Incidence of and survival after mammary tumors in a population of over 80,000 insured female dogs in Sweden from 1995 to 2002. Prev Vet Med 2005, 69, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enginler, S.O.; Akış, I.; Toydemir, T.S.; et al. Genetic variations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in dogs with mammary tumours. Vet Res Commun 2014, 38, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, T.; Matulonis, U. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: evidence, experience and clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2017, 9, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmer, H.; Lord, C.J.; Tutt, A.; et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature 2005, 434, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, J.; Creevy, K.E.; Promislow, D.E. Mortality in north american dogs from 1984 to 2004: an investigation into age-, size-, and breed-related causes of death. J Vet Intern Med 2011, 25, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, P.C.; Boss, D.S.; Yap, T.A.; et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med 2009, 361, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futreal, P.A.; Liu, Q.; Shattuck-Eidens, D.; Cochran, C.; et al. BRCA1 mutations in primary breast and ovarian carcinomas. Science 1994, 266, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe, P.L. The companion animal as a sentinel for environmentally related human diseases. Acta Vet Scand Suppl 1988, 84, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gompper, M.E. The dog–human–wildlife interface: assessing the scope of the problem; Oxford University Press, 2023; pp. 9–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.M.; Lee, M.K.; Newman, B.; Morrow, J.E.; et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science 1990, 250, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, N.D.; Shaw, S.C.; Craigon, P.J.; et al. Environmental risk factors for canine atopic dermatitis: a retrospective large-scale study in Labrador and golden retrievers. Veterinary Dermatology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heron, M.; Anderson, R.N. Changes in the Leading Cause of Death: Recent Patterns in Heart Disease and Cancer Mortality. NCHS Data Brief 2016, 254, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, A. Case Study: Malignant Oral Melanoma. Fido Cure Publishing Web, VTS ECC. 2022. Available online: https://blog.fidocure.com/fidocure-blog/malignant-oral-melanoma (accessed on 3 April 2022).

- Hull, A. Adrenocortical Carcinoma Case Study: Pixelle. Fido Cure Publishing Web, VTS ECC. 2023. Available online: https://blog.fidocure.com/fidocure-blog/adrenocortical-carcinoma-case-study-pixelle (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Inazawa, J.; Inoue, J.; Imoto, I. Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH)-arrays pave the way for identification of novel cancer-related genes. Cancer Science 2004, 95, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isakoff, S.; Overmoyer, B.; Tung, N.; et al. A phase II trial of the PARP inhibitor veliparib (ABT888) and temozolomide for metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010, 28, 1019–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.B.; Carreira, A.; Kowalczykowski, S.C. Purified human BRCA2 stimulates RAD51-mediated recombination. Nature 2010, 467, 678–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhanwar-Uniyal, M. BRCA1 in cancer, cell cycle and genomic stability. Frontiers in Bioscience : a Journal and Virtual Library 2003, 8, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Yano, K.; Matsuo, F.; et al. Identification of Rad51 alteration in patients with bilateral breast cancer. J Hum Genet 2000, 45, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, B.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Schmutzler, R.K.; et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 2015, 33, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Sharip, A.; Jiang, J.; et al. Reverse the Resistance to PARP Inhibitors. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2017, 13, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klopfleisch, R.; Klose, P.; Gruber, A.D. The combined expression pattern of BMP2, LTBP4, and DERL1 discriminates malignant from benign canine mammary tumors. Vet Pathol 2010, 47, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kol, A.; Arzi, B.; Athanasiou, K.A.; et al. Companion animals: Translational scientist’s new best friends. Science Translational Medicine 2015, 7, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, L. Population-based incidence of mammary tumours in some dog breeds. J Reprod Fertil Suppl 2001, 439–443. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo, J.; Moreno, V.; Gupta, A.; et al. An Adaptive Study to Determine the Optimal Dose of the Tablet Formulation of the PARP Inhibitor Olaparib. Target Oncol 2016, 11, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, Y.J.; Shattuck-Eidens, D.; Futreal, P.A.; et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 1994, 266, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.E.; El-Shakankery, K.H.; Lee, J.Y. PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer: overcoming resistance with combination strategies. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology 2022, 33, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misenko, S.M.; Patel, D.S.; Her, J.; Bunting, S.F. DNA repair and cell cycle checkpoint defects in a mouse model of ‘BRCAness’ are partially rescued by 53BP1 deletion. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 881–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.E.; Burkman, K.D.; Carter, M.N.; Peterson, M.R. Causes of death or reasons for euthanasia in military working dogs: 927 cases (1993-1996). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2001, 219, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieto, A.; Perez-Alenza, M.D.; Del Castillo, N.; et al. BRCA1 expression in canine mammary dysplasias and tumours: relationship with prognostic variables. Journal of Comparative Pathology 2003, 128, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiai, K.; Morimatsu, M.; Tomizawa, N.; Syuto BCloning sequencing full length of canine, B.r.c.a. 2.; Rad51, c.D.N.A. J Vet Med Sci 2001, 63, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paoloni, M.; Davis, S.; Lana, S.; et al. Canine tumor cross-species genomics uncovers targets linked to osteosarcoma progression. BMC Genomics 2009, 10, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, M.; Khanna, C. Translation of new cancer treatments from pet dogs to humans. Nature Reviews Cancer 2008, 8, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paynter, A.N.; Dunbar, M.D.; Creevy, K.E.; Ruple, A. Veterinary Big Data: When Data Goes to the Dogs. Animals 2021, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, A.; Pasaol, J.; Bajzert, A.; et al. PARP inhibition as a potential target for canine lymphoma and leukemia. Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2023, 46, 38–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penson, R.; Whalen, C.; Lasonde, B.; et al. A phase II trial of iniparib (BSI-201) in combination with gemcitabine/carboplatin (GC) in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011, 29, 5004–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 2000, 406, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyraud, F.; Italiano, A. Combined PARP Inhibition and Immune Checkpoint Therapy in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2020, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, R.; Jones, C.; Middleton, M.; et al. Phase I study of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, AG014699, in combination with temozolomide in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res 2008, 14, 7917–7923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Lorigan, P.; Steven, N.; et al. A phase II study of the potent PARP inhibitor, Rucaparib (PF-01367338, AG014699), with temozolomide in patients with metastatic melanoma demonstrating evidence of chemopotentiation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2013, 71, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proschowsky, H.F.; Rugbjerg, H.; Ersbøll, A.K. Mortality of purebred and mixed-breed dogs in Denmark. Prev Vet Med 2003, 58, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, N.; Fang, F.; Ozes, A.; et al. An Effective Epigenetic-PARP Inhibitor Combination Therapy for Breast and Ovarian Cancers Independent of BRCA Mutations. Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 24, 3163–3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Sun, W.; Yang, X.; et al. Promoter mutation and reduced expression of BRCA1 in canine mammary tumors. Research in Veterinary Science 2015, 103, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebbeck, T.R.; Mitra, N.; Domchek, S.M.; et al. Modification of BRCA1-Associated Breast and Ovarian Cancer Risk by BRCA1-Interacting Genes. Cancer Research 2011, 71, 5792–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, P.; Euler, H.P. Molecular Biological Aspects on Canine and Human Mammary Tumors. Veterinary Pathology 2011, 48, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, P.; Melin, M.; Biagi, T.; et al. Mammary tumor development in dogs is associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 8770–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, P.M.; Biagi, T.; Fall, T.; et al. Mammary tumor development in dogs is associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cancer Res 2009, 69, 8770–8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Dobbin, Z.C.; Nowsheen, S. An ex vivo assay of XRT-induced Rad51 foci formation predicts response to PARP-inhibition in ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology 2014, 134, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Zhao, W.; Ju, Z.; et al. PARPi Triggers the STING-Dependent Immune Response and Enhances the Therapeutic Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Blockade Independent of BRCAness. Cancer Research 2018, 79, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; et al. Cancer Statistics 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thirthagiri, E.; Klarmann, K.D.; Shukla, A.; et al. BRCA2 minor transcript lacking exons 4-7 supports viability in mice and may account for survival of humans with a pathogenic biallelic mutation. Human Molecular Genetics 2016, 25, 1934–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Duke, S.E.; Wang, H.J.; et al. ’Putting our heads together’: insights into genomic conservation between human and canine intracranial tumors. J Neurooncol 2009, 94, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorlacius, S.; Olafsdóttir, G.H.; Tryggvadottir, L.; et al. A single BRCA2 mutation in male and female breast cancer families from Iceland with varied cancer phenotypes. Nature Genetics 1996, 13, 117–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thumser-Henner, P.; Nytko, K.; Rohrer, C. Mutations of BRCA2 in canine mammary tumors and their targeting potential in clinical therapy. BMC Veterinary Research 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, N.; Wilson, L.; Bhatnagar, P.; et al. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J 2016, 37, 3232–3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillano, D.; Weiss, M.E.; Schneider, J.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes for the genetic diagnostics of hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2015, 17, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, N.M.; Boughey, J.C.; Pierce, L.J.; et al. Management of Hereditary Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2020, 38, 2080–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutt, A.; Robson, M.; Garber, J.E.; et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Stingl, L.; Berghammer, H. Mice lacking ADPRT and poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation develop normally but are susceptible to skin disease. Genes Dev 1995, 9, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalon, M.; Tuval-Kochen, L.; Castel, D.; et al. Overcoming Resistance of Cancer Cells to PARP-1 Inhibitors with Three Different Drug Combinations. PLoS ONE 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, Y.; Morimatsu, M.; Ochiai, K.; et al. Reduced canine BRCA2 expression levels in mammary gland tumors. BMC Vet Res 2015, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, Y.; Ochiai, K.; Morimatsu, M.; et al. Effects of the Missense Mutations in Canine BRCA2 on BRC Repeat 3 Functions and Comparative Analyses between Canine and Human BRC Repeat 3. PLoS ONE 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BRCA1 (Human) | BRCA1 (Canine) | BRCA2 (Human) | BRCA2 (Canine) | |

| Chromosome Location | 17q21 | Chr.9 | 13q12.3 | Chr.25 |

| Gene Length (base pairs) | ~100,000 | ~85,000 | ~84,000 | ~81,000 |

| Protein Length (amino acids) | 1863 | 1832 | 3418 | 3414 |

| Conservation across species | Highly conserved | Conserved | Highly conserved | Conserved |

| Biological Function | Tumor suppressor | Tumor suppressor | DNA repair | DNA repair |

| Protein Domains | RING, BRCT, SQ/TQ cluster | RING, BRCT, SQ/TQ cluster | BRC repeats, DNA-binding, helicase | BRC repeats, DNA-binding, helicase |

| Association with Cancer | Breast, ovarian, other cancers | Mammary gland, ovarian, other cancers | Breast, ovarian, other cancers | Mammary gland, ovarian, other cancers |

| Genetic Variants | Numerous pathogenic variants identified | Limited studies on genetic variants | Numerous pathogenic variants identified | Limited studies on genetic variants |

| Mutational Spectrum | Point mutations, insertions, deletions | Point mutations, insertions, deletions | Point mutations, insertions, deletions | Point mutations, insertions, deletions |

| Disease Risk | Increased risk of breast, ovarian, and other cancers | Increased risk of mammary gland, ovarian, and other cancers | Increased risk of breast, ovarian, and other cancers | Increased risk of mammary gland, ovarian, and other cancers |

| References | (Deng and Brodie 2000; Rebbeck et al.2011; Caestecker et al. 2013) | (Nieto et al. 2003; Rivera and Euler 2011; Qiu et al. 2015) | (Thorlacius et al.1996; Bertwistle et al. 1997; Thirthagiri et al. 2016) | (Yoshikawa et al. 2012; Yoshikawa et al. 2015; Thumser-Henner et al. 2020) |

| PARP inhibitor tested | Cancer type | Efficacy | Refs |

| Olaparib | Solid tumors (ovarian: 35%) | Clinical benefit for 63% (in BRCA mutations carriers’ patients) | (Fong et al. 2009) |

| Breast | ORR*: 41% | (Tutt et al. 2010) | |

| Ovarian | ORR*: 33% | (Audeh et al. 2010) | |

| Ovarian, breast, pancreatic and prostate | Tumor response rate*: 26.2% | (Kaufman et al. 2015) | |

| Rucaparib (Temozolomide) | Metastatic melanoma | Clinical benefit for 34.8% of the patients | (Plummer et al. 2013) |

| Advanced solid malignancies |

CR: 1/32 (melanoma) PR: 2/32 (melanoma, desmoid tumor) |

(Plummer et al. 2008) | |

| Veliparib | Metastatic breast cancer | ORR (CR+PR) 12.5% (3/24) | (Isakoff et al. 2010) |

| Iniparib | Metastatic TNBC | ORR (CR+PR) 32% | (Penson et al. 2011) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).