1. Introduction

Mammary tumors represent the most frequent mammary gland neoplasia in female dogs. In epidemiological studies, the annual incidence of mammary tumors is 47.7% for benign and 47.5% for malignant tumors [

1]. In the USA, mammary tumors in canines have decreased because of early neutering, but in European countries still are the most frequent mammary cancer forms in female dogs [

1,

2]. The golden standard treatment procedure worldwide is represented by the surgical excision of the mammary chain but with unsatisfactory results. The high number of dogs with mammary cancer show lymphatic or vascular invasion and high rates of recurrence and metastasis [

3,

4]. There is limited information about chemotherapy and radiotherapy efficacy in treating canine mammary tumors CMT, probably because the procedures are expensive. Despite some case reports regarding the responses to chemotherapeutics such as doxorubicin [

5], mitoxantrone [

6], paclitaxel [

7,

8] and carboplatin [

9], it is not clear if the chemotherapy improves overall survival of the treated dogs [

2,

10].

One of the most used therapeutic agents in human cancer is the anthracycline Doxorubicin (DOXO) [

11,

12,

13]. In the last years, a few studies have shown the efficiency of this drug in canine patients [

4,

14]. Doxorubicin induces the production of free radicals, intercalation into DNA strands and inhibition of topoisomerases I and II, causing DNA damage and activating caspases, ultimately leading to apoptosis [

12,

15].

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is essential in embryonic development and tissue regeneration. An aberrant reactivation of EMT is associated with malignant properties of tumor cells during cancer progression and metastasis, including migration and invasiveness, increased tumor stemness, and enhanced resistance to therapy [

16,

17,

18]. Studies performed in humans identified EMT as involved in DOX-resistance to therapy, stimulating migration of tumor cells and metastasis; furthermore, EMT mediates resistance of cancer cells to DOX-mediated apoptosis [

18,

19].

The present study aimed to analyze the inhibitory effect of Doxorubicin in vitro models of canine mammary cancer to evaluate the efficiency of this therapeutic agent and the expression levels of key genes involved in the EMT process.

2. Materials and Methods

Our experiment was conducted in two canine mammary carcinoma cell lines (P114 and CMT-U27) kindly donated by Prof. Gerard Rutteman from the Netherlands and Prof. Eva Hellmen from Sweden. The two canine cell lines were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Glutamine for P114, respectively DMEM low glucose supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Glutamine for CMT-U27. The culture medium and supplements were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

The P114 cell line is a canine anaplastic mammary carcinoma (AMC) cell line shown in dogs and felines. In dogs, AMC is considered the most aggressive type of mammary tumor, showing a low frequency, and is associated with a short survival time. This histologic presentation is characterized by a diffuse infiltrating neoplasm composed of large, pleomorphic, multinucleated giant cells, frequently showing acidophilic cytoplasm, and dispersed nuclear chromatin. The CMT-U27 cell line is a canine mammary carcinoma cell line [

20,

21,

22]

1x104 cells/well were cultured in 96-well culture plates for 24h at 37ºC in 5% CO2 atmosphere incubators. After 24h incubation, cell cultures were treated with Doxorubicin – Sigma Aldrich (DOXO) doses. At 48h after treatment, the medium was discarded, and 100 µl MTT solution was added to every well. After 2h incubation at 37ºC, the MTT solution was removed, and the formazan crystal was solubilized with 100 µl DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) (Sigma-Aldrich). The absorbance was measured at 570/690 nm for the cell viability assay in a microplate reader (Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader Biotech).

The Multi-Parameter Apoptosis Kit (Cayman) was used for the fluorescence microscopy evaluation of apoptosis. Cell staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Stained cells were analyzed at UV wavelength for Hoechst and 560/595 nm for TMRE staining on an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope. Hoechst is a specific stain for the nucleus, while TMRE indicates the mitochondrial membrane activity potential.

Apoptosis evaluation was also performed using a triple fluorescence marking by Actin-stain 488 Fluorescent Phalloidin (Cytoskeleton, Inc.), Mitotracker (Invitrogen) for mitochondria labelling and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Invitrogen) for nucleus staining.

Cell lines were cultured in a 96-well culture plate for 48h and then treated with 2.5 µM DOXO. After 48 h treatment, cell confluency was analyzed using a Celigo Image Cytometer (Nexcelom).

Cell lines were cultured in a 96-well culture plate for 48 h and then treated with 2.5 μM DOXO. After 48 h treatment, cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol at 4°C 30 minutes. After fixation, the cells were marked with RNase A and Propidium Iodide (PI) solution for 45 minutes in dark 37ºC in 5% CO2 atmosphere incubators. The cell cycle analysis was performed using Celigo Image Cytometer (Nexcelom).

P114 and CMT-U27 cells were incubated with 2.5 µM doxorubicin for 48h to induce DNA damage. The cells were detached after 48 hours, counted, and reseeded in the standard medium in triplicate for each condition and cellular type (500 cells/6 well plate). Cells returned to the incubator for 7 days to form colonies and then were fixed with ice-cold methanol for 15 minutes, dried, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 25% methanol for 20 minutes. After washing with water and drying, colonies were counted manually using the Celigo Image Cytometer (Nexcelom).

Canine mammary cancer cells were pre-treated individually with DOXO for 48 hours in 24-well plates. After treatment, cell proliferation was blocked by a 30-minute pretreatment with mitomycin C (40 μg/ml). A scratch was then made in each well using a 20-μl pipette tip, and cells were maintained in a medium with 1% serum. The distances between the edges were scaled at 0, 8, and 24h.

Canine cells (15X103 cells/well) were cultured in the upper 8 µm Falcon cell culture inserts pre-coated with 100 µl Matrigel in 500 µl media without serum. In the lower chambers (24 well plates), 750 µl complete medium containing 10% FBS was added. After 48 h of incubation, the cells that had invaded through the pores and attached to the bottom surface of the membrane were stained with Calcein-AM (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Images of the stained invaded cells were captured under an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescent microscope.

For the extraction of total RNA, the Trizol (TriReagent Sigma-Aldrich) protocol was used, and the quantitative and qualitative control was performed using the Nanodrop-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), and the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. CDNA synthesis was performed using the RT2 First Strand Kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. For the RT2 Profiler PCR Array (PAFD-090ZE-1 Dog Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transmission – EMT- Qiagen), we used the SYBR Green Master Mix and the ViiA7 instrument from Applied Biosystems according to the manufacturer protocol. Alterations of gene expression levels for the studied genes were evaluated using the Qiagen RT2 Profiler PCR Array and Assays Data Analysis software.

3. Results

3.1. Doxorubicin Inhibits CELL viability in Both In Vitro Canine Mammary Cancer Models

Treatment of P114, CMT-U27 mammary cancer cell lines with different concentrations of DOXO for 48 hours shows inhibition of viability in a dose-dependent manner for both canine cell lines. Moreover, the two cell lines have similar values for the half maximal inhibitory concentration with an approximate dose of 13 µM Doxorubicin (

Figure 1A,B). Because of the high toxicity of the DOXO we choose to apply the smallest concentration which shows an inhibitory effect in the cell proliferation in the canine mammary tumor cell lines. Due to the relatively equal concentration of DOXO corresponding to the IC50 of each cell line, we decided to continue the experiments with 2.5 µM of therapeutic agent to compare the response of each cell line under standard conditions.

3.2. Doxorubicin Treatment Decreases Cell Viability and Induces Apoptosis in Cell Lines

The triple fluorescence staining for the cytoskeleton, mitochondria, and nucleus shows damage to the cells by the treatment (

Figure 1C,D). Fluorescence microscopy assay revealed that DOXO treatment after 48h induced in P114 and CMT-U27 cell lines a decreased mitochondrial membrane potential activity and morphological changes, including nuclear DNA condensation, nuclear shrinkage, and fragmentation (marked with green arrows). We can observe a significant reduction of the viable cell’s percentage to 30% (p-value = 0.0061) in the P114 treated cells versus untreated cells and 32% for the CMT-U27 cells (p-value = 0.0002) (

Figure 1E,F).

3.3. Reduced Cell Confluency in the Treated Versus UNTREATED cells

P114 and CMT-U27 treated with 2.5 µM of DOXO for 48h presents a lower confluency rate than untreated cells. We can observe that the treated cells show between 30-40% reduced confluency versus the untreated cells. (

Figure 2A,B)

3.4. Cell Cycle Arrest Induced by Doxorubicin

Doxorubicin induces cell cycle arrest in both cell lines in the G0/G1 phase. For the evaluation of cell growth inhibition induced by ABT-199, a cell cycle assay was performed by Celigo imaging flow cytometry. In both cell lines was observed a decreased percentage of cells in the G0/G1 phase in treated cells versus control cells. In the P114 treated cell line, the S phase distribution is slightly decreased (p-value 0.0456), the G2/M phase distribution increased from 62% to 72% (p-value 0.0379), and the G0/G1 phase distribution decreased from 31% to 25% (p-value 0.0456). CMT-U27 treated cells show an increased distribution in the S phase from 10% to 17% (p-value 0.0043), while the G0/G1 phase distribution decreased from 76% to 64% (p-value <0.0001). In the G2/M phase, no statistically significant changes were observed (

Table 1) (

Figure 2C,D).

3.5. Doxorubicin Reduces Colony Formation in Both Canine Mammary Cancer Cell Lines

Both canine cell lines treated with 2.5 µM of DOXO for 48h show a significantly reduced colony formation capacity demonstrated through the ability of untreated cells to form more colonies compared to the treated (P114 p-value 0.0039; CMT-U27 p-value 0.017) ones where we can observe a significant low number of colonies after 7 days from the treatment. (

Figure 2E,F)

3.6. Doxorubicin Impairs Cell Migration in Both Canine In Vitro Mammary Cancer Models

CMT-U27 and P114 cell lines treated with 2.5 µM of DOXO for 48h show a significantly reduced migratory capacity demonstrated through the ability of control cells to close the gap from the scratch assay compared to the treated ones where the gap is still significantly visible after 48h (

Figure 3A,B).

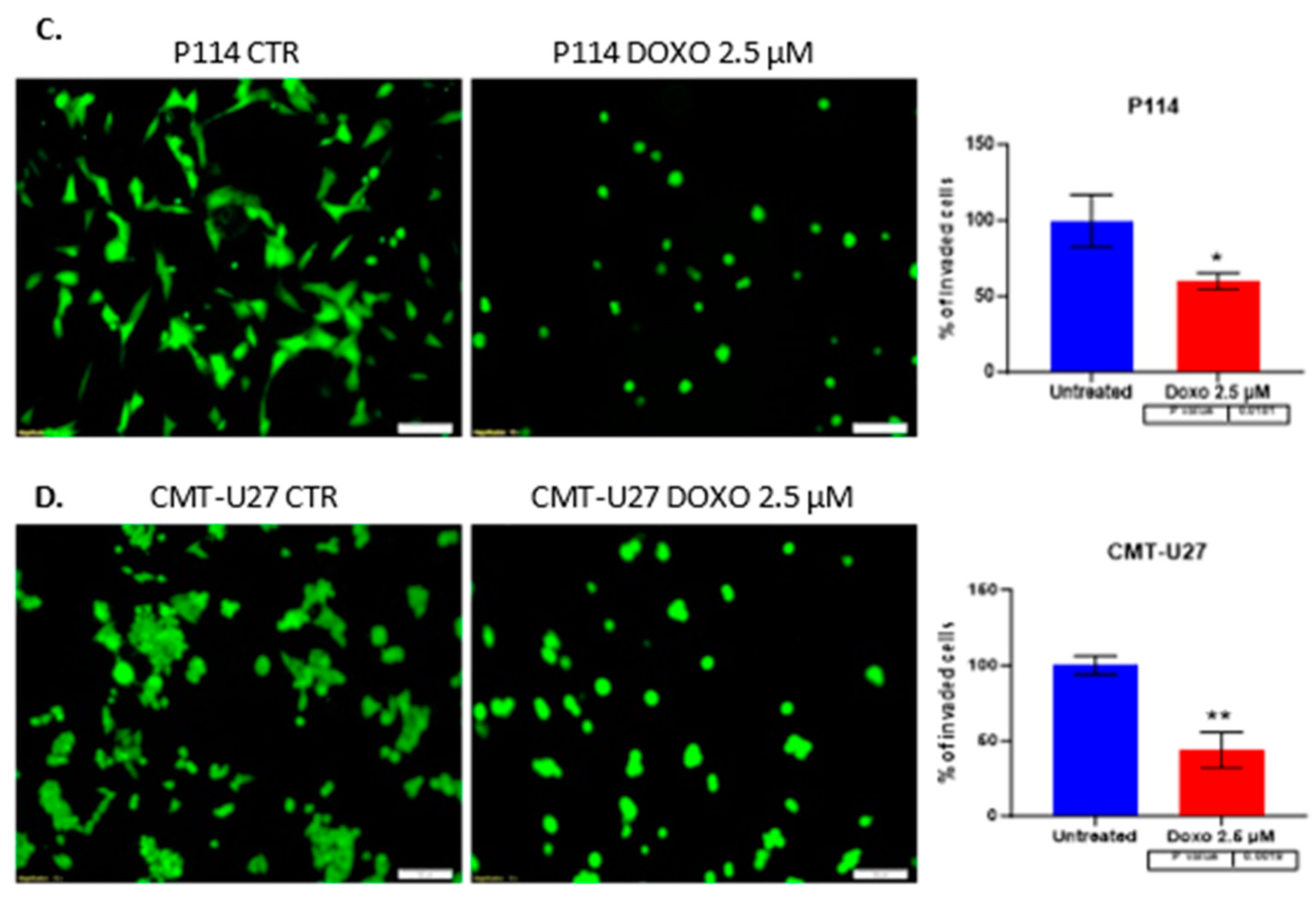

3.7. Doxorubicin Treatment Suppresses Cell Invasion

A significantly suppressed invasion ability was observed in both canine mammary cancer cell lines treated with DOXO. Canine cells treated with 2.5 µM DOXO show a reduced percentage of the invaded cells, a 60% p-value of 0.018 for P114 and a 43% p-value of 0.001 for the CMT-U27 cell line. (

Figure 3C,D)

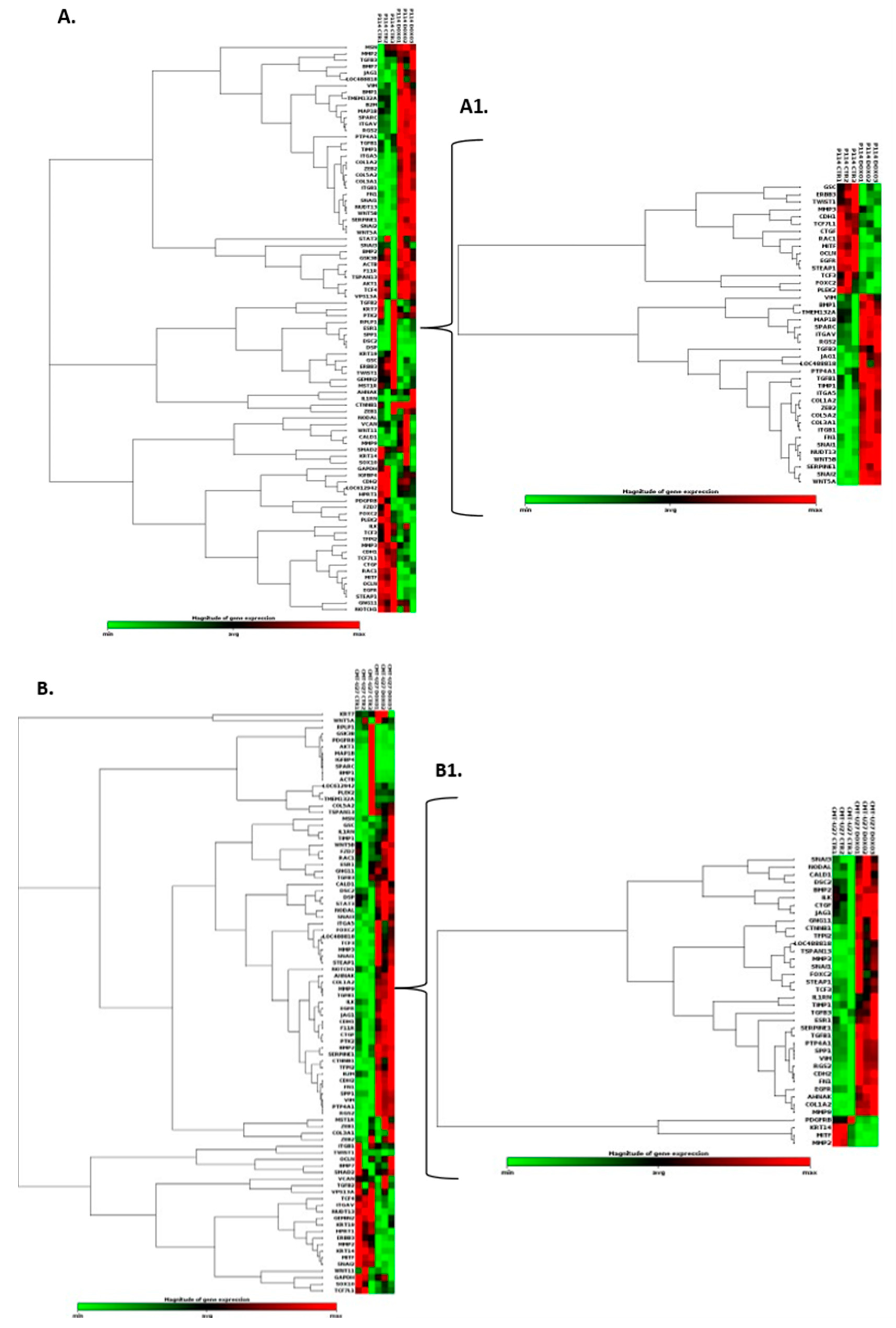

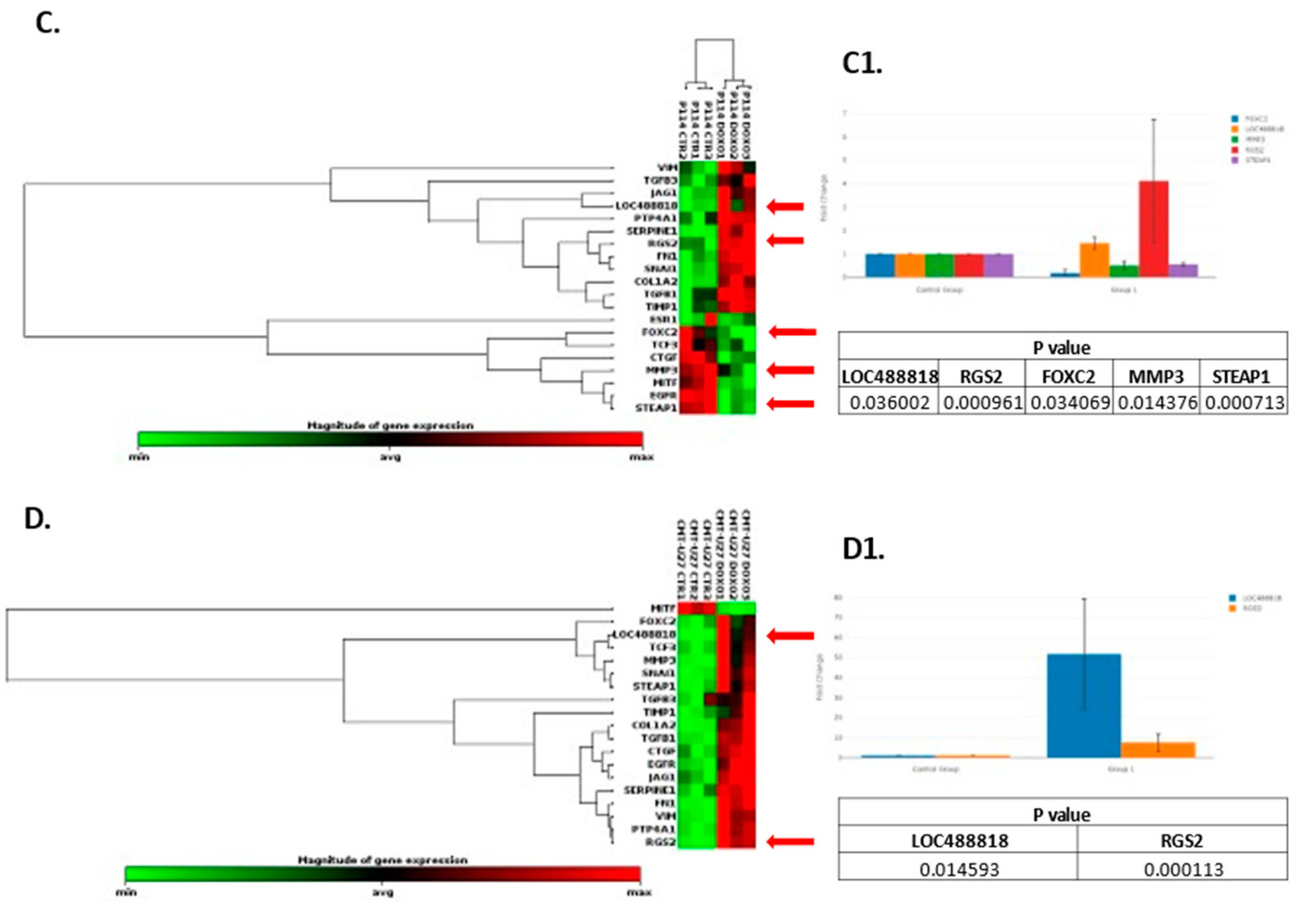

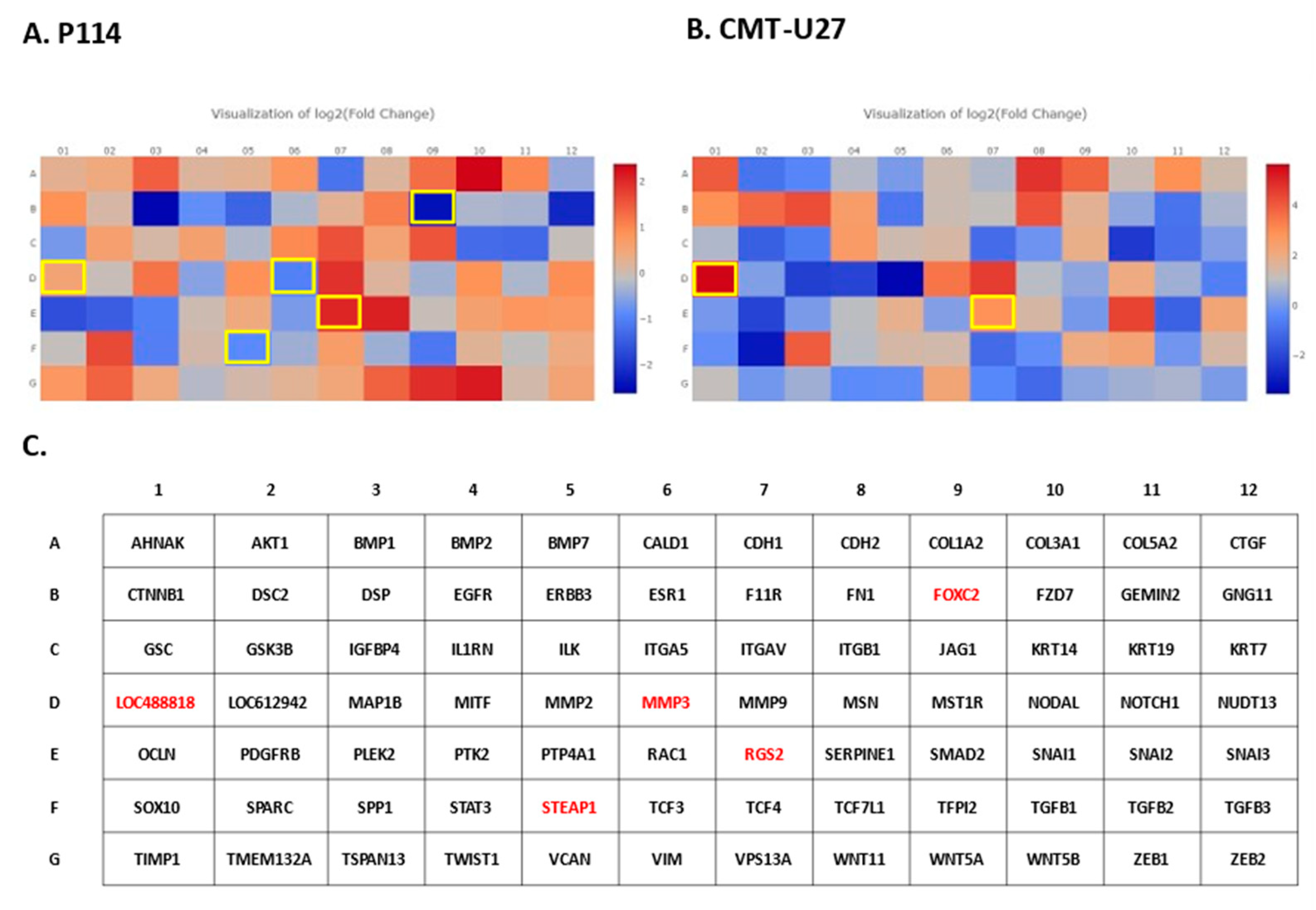

3.8. Doxorubicin Treatment Induces EMT Gene Expression Level Alteration

Based on the RT

2 Profiler PCR Array analysis of Dog Epithelial to Mesenchymal Transition genes, a total of 41 for the P114 cell line and 38 for the CMT-U27 cell line significantly (p-value < 0.05) differentially expressed EMT-related genes were identified (

Figure 4A/A1, B/B1). Nineteen genes were identified to be common in the two cell lines treated with DOXO. P114 cell line treated with DOXO shows an altered expression level for five genes (LOC488818/FGF-BP1, RGS2, FOXC2, STEAP1 and MMP3) and CMT-U27 only for two genes (LOC488818 and RGS2) (

Figure 4C/C1 4D/D1).

4. Discussion

Our

in vitro study aimed to investigate doxorubicin’s efficacy in treating CMT. Our findings suggest that therapy with Doxorubicin has apoptotic effects on canine

in vitro models of mammary cancer and can significantly reduce cell migration, invasion, confluency, and cell colony formation and can induce cell cycle arrest in treated versus untreated cells. Moreover, Doxorubicin treatment can alter EMT gene expression levels. Consistent with our data, DOXO treatment inhibited the cell proliferation at 48h in two CMT cell lines: one from a primary tumor and one from a lymph node metastasis; furthermore, a substantial effect on the cell cycle has been observed and an increase in the gene expression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and Breast Cancer Resistance Protein (BCRP) compared to the controls [

14].

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a biological process that occurs in various types of tumors, including canine mammary tumors [

1]. In this complex cellular phenomenon, epithelial cells are organized tightly and present specific adhesion properties. They suffer molecular and structural characteristics to become more mesenchymal cells, losing their connectivity and acquiring migratory properties [

2]. This phenomenon involves cancer progression, invasion, and metastasis [

3]. EMT plays a key role in cancer progression [

23,

24]. Our data suggests that canine mammary tumors can benefit from the activity of Doxorubicin through inhibition of EMT and different cancer-related biological processes inducing tumor suppressor mechanisms. Regulator of G protein signaling 2 (RGS2) belongs to a family of proteins that serve as a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) for Gα subunits [

25]. It has been described as a potential target in different types of human cancer, including breast cancer [

25,

26]. Thus, RGS2 was upregulated in MCF7 breast cancer cells inhibiting cell proliferation [

25]. In breast-invasive carcinoma of no special type (BIC-NST), the downregulation of RGS2 was associated with a significantly poorer overall survival rate [

25]. LOC488818 is also named FGF-BP1 (Fibroblast Growth Factor Binding Protein 1) and plays an important role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration. FGF-BP1 is a protein that acts as a chaperone molecule and is found to be up-regulated in breast cancers, squamous cell cancer and colon cancer [

27]. Overexpression of FGF-BP1 was correlated with better prognosis in human breast cancer patients [

28]. A transcription factor known as FOXC2, which plays an important role in determining the fate of mesenchymal cells during embryonic development, has also been implicated in cancer cells’ ability to metastasize [

29]. FOXC2 is a transcription factor that induces mesenchymal differentiation during EMT [

29,

30] and has the potential to be a therapeutic target in inhibition of metastasis [

31]. FOXC2 overexpression was significantly associated with aggressive basal-like human breast cancers [

29]. The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) family of zinc-containing and calcium-dependent proteinases play a crucial role in various biological processes, including tissue remodeling, wound healing and angiogenesis, and diseases such as arthritis, cancer, and tissue ulceration. As they hydrolyze extracellular matrix components (ECM), they are also known as matrixins. MMP3 is a zinc-dependent proteolytic enzyme that regulates different biological processes by altering the extracellular matrix [

32]. MMP3 over-expression was correlated with tumor growth and metastasis in different types of cancer, including breast cancer [

32,

33]. Several changes are induced by MMP-3 (increased cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, changes in the stroma, etc.), which may result in the development of breast cancer in women. This protein may also affect Mammary tumors in canines [

34]. STEAP1 is a membrane-bound channel protein found overexpressed in various cancers [

35,

36,

37,

38] and was associated with a malignant phenotype and disease prognosis [

39]. STEAP1 upregulation significantly inhibited the capacity of migration of the tumor cells and invasion potential and downregulated expression of the EMT-related genes in the human breast cancer [

39].

5. Conclusions

The treatment and knowledge of canine mammary tumors (CMTs) have made significant progress in veterinary oncology as a spontaneous model for breast cancer research in the last few decades. Using Doxorubicin to target specific biological processes like apoptosis, cell cycle, migration, invasion, and EMT may result in better outcomes for patients with this disease. The canine model of breast cancer represents a good opportunity for new therapeutic strategies to be developed for human breast cancer. Doxorubicin is a widely used antineoplastic agent in humans and animals. Multiple mechanisms are involved in DOXO’s action, producing free radicals, intercalation into DNA strands, and inhibiting topoisomerases I and II, causing DNA damage, activating caspases, and ultimately causing apoptosis. The importance of new therapeutic strategies development in canine mammary cancer represents a major challenge worldwide. Findings from our study provide valuable information for revealing the link between doxorubicin, phenotypic changes, and proliferation dynamics in malignant cells that may contribute to chemotherapy treatment limitations in the canine model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Madalina Gherman, Oana Zanoaga, Lajos Raduly and Ioana-Berindan Neagoe.; methodology, Madalina Gherman, Lajos Raduly, Oana Zanoaga, Liviuta Budisan: data curation, Oana Zanoaga, Lajos Raduly and Ioana-Berindan Neagoe.; writing—original draft preparation, Madalina Gherman, Oana Zanoaga, Lajos Raduly.; writing—review and editing, Oana Zanoaga, Lajos Raduly and Ioana-Berindan Neagoe.; supervision, Ioana-Berindan Neagoe. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the support from the PCD 2461/28/17 January 2020 research project founded by “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania. The authors acknowledge the support from the research project - PCD 1033/27/13 January 2021, founded by “Iuliu Hatieganu” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Acknowledgments

This work was granted by project PDI-PFE-CDI2021, entitled Increasing the Performance of Scientific Research, Supporting Excellence in Medical Research, and Innovation in Medicine, PROGRES, no. 40PFE/30 December 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

References

- Salas, Y.; Marquez, A.; Diaz, D.; Romero, L. Epidemiological Study of Mammary Tumors in Female Dogs Diagnosed during the Period 2002-2012: A Growing Animal Health Problem. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raduly L, Cojocneanu R, Sarpataki O, Chira S, Atanasov A, Braicu C, Berindan - Neagoe I, Marcus I: Canis lupus familiaris as relevant animal model for breast cancer - A comparative oncology review. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2018, 36, 119–148.

- Sorenmo, K.U.; Rasotto, R.; Zappulli, V.; Goldschmidt, M.H. Development, anatomy, histology, lymphatic drainage, clinical features, and cell differentiation markers of canine mammary gland neoplasms. Vet. Pathol. 2011, 48, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivia, G.; Alonso-Diez, A.; Perez-Alenza, D.; Pena, L. From Conventional to Precision Therapy in Canine Mammary Cancer: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 623800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R. Identifying problems in the motivation, performance, and retention of nursing staff. Foreword: Reliving the forums. NLN: Washington, DC, USA, 1979; pp. 1–5.

- Ogilvie, G.K.; Obradovich, J.E.; Elmslie, R.E.; Vail, D.M.; Moore, A.S.; Straw, R.C.; Dickinson, K.; Cooper, M.F.; Withrow, S.J. Efficacy of mitoxantrone against various neoplasms in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1991, 198, 1618–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Poirier, V.J.; Hershey, A.E.; Burgess, K.E.; Phillips, B.; Turek, M.M.; Forrest, L.J.; Beaver, L.; Vail, D.M. Efficacy and toxicity of paclitaxel (Taxol) for the treatment of canine malignant tumors. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2004, 18, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Euler, H.; Rivera, P.; Nyman, H.; Haggstrom, J.; Borga, O. A dose-finding study with a novel water-soluble formulation of paclitaxel for the treatment of malignant high-grade solid tumours in dogs. Vet. Comp. Oncol. 2013, 11, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorenmo, K. Canine mammary gland tumors. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2003, 33, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raduly, L.; Gulei, D.; Jurj, A.; Moldovan, C.; Balint, E.; Marcus, I.; Sarpataki, O.; Korban, S.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Comparative effects of BCL-2 inhibition in canine and human breast cancer in vitro models-a review. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2022, 40, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Mentoor, I.; Engelbrecht, A.M.; van de Vyver, M.; van Jaarsveld, P.J.; Nell, T. The paracrine effects of adipocytes on lipid metabolism in doxorubicin-treated triple negative breast cancer cells. Adipocyte 2021, 10, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, E.M.; Smith, K.L.; Stearns, V. Management of hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2020, 47, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocan-Cartita, C.A.; Jurj, A.; Zanoaga, O.; Cojocneanu, R.; Pop, L.A.; Moldovan, A.; Moldovan, C.; Zimta, A.A.; Raduly, L.; Pop-Bica, C.; et al. Correction to: New insights in gene expression alteration as effect of doxorubicin drug resistance in triple negative breast cancer cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2020, 39, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levi, M.; Salaroli, R.; Parenti, F.; De Maria, R.; Zannoni, A.; Bernardini, C.; Gola, C.; Brocco, A.; Marangio, A.; Benazzi, C.; et al. Doxorubicin treatment modulates chemoresistance and affects the cell cycle in two canine mammary tumour cell lines. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciocan-Cartita, C.A.; Jurj, A.; Raduly, L.; Cojocneanu, R.; Moldovan, A.; Pileczki, V.; Pop, L.A.; Budisan, L.; Braicu, C.; Korban, S.S.; et al. New perspectives in triple-negative breast cancer therapy based on treatments with TGFbeta1 siRNA and doxorubicin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2020, 475, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirlog, R.; Chiroi, P.; Rusu, I.; Jurj, A.M.; Budisan, L.; Pop-Bica, C.; Braicu, C.; Crisan, D.; Sabourin, J.C.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. Cellular and Molecular Profiling of Tumor Microenvironment and Early-Stage Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groza, I.M.; Braicu, C.; Jurj, A.; Zanoaga, O.; Lajos, R.; Chiroi, P.; Cojocneanu, R.; Paun, D.; Irimie, A.; Korban, S.S.; et al. Cancer-Associated Stemness and Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Signatures Related to Breast Invasive Carcinoma Prognostic. Cancers 2020, 12, 3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, S.; Abadi, A.J.; Gholami, M.H.; Hashemi, F.; Zabolian, A.; Hushmandi, K.; Zarrabi, A.; Entezari, M.; Aref, A.R.; Khan, H.; et al. The involvement of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in doxorubicin resistance: Possible molecular targets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 908, 174344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmen, E. Characterization of four in vitro established canine mammary carcinoma and one atypical benign mixed tumor cell lines. J. Tissue Cult. Assoc. 1992, 28A, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.A.; van Wolferen, M.E.; Gracanin, A.; Bhatti, S.F.; Krol, M.; Holstege, F.C.; Mol, J.A. Gene expression profiles of progestin-induced canine mammary hyperplasia and spontaneous mammary tumors. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Pol. Physiol. Soc. 2009, 60 (Suppl. 1), 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Krol, M.; Pawlowski, K.M.; Skierski, J.; Rao, N.A.; Hellmen, E.; Mol, J.A.; Motyl, T. Transcriptomic profile of two canine mammary cancer cell lines with different proliferative and anti-apoptotic potential. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. Off. J. Pol. Physiol. Soc. 2009, 60 (Suppl. 1), 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, D.; Fritz, A.J.; Zaidi, S.K.; van Wijnen, A.J.; Nickerson, J.A.; Imbalzano, A.N.; Lian, J.B.; Stein, J.L.; Stein, G.S. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells contribute to breast cancer heterogeneity. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 9136–9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.H.; Park, D.W.; Huang, B.; Kang, S.H.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, C.; Bae, Y.S.; Lee, J.G.; Baek, S.H. RGS2 suppresses breast cancer cell growth via a MCPIP1-dependent pathway. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ye, Q.; Cao, Y.; Tan, J.; Wang, F.; Jiang, J.; Cao, Y. Downregulation of regulator of G protein signaling 2 expression in breast invasive carcinoma of no special type: Clinicopathological associations and prognostic relevance. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tassi, E.; Al-Attar, A.; Aigner, A.; Swift, M.R.; McDonnell, K.; Karavanov, A.; Wellstein, A. Enhancement of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) activity by an FGF-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 40247–40253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Di, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Feng, L.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Y. An immune-related signature that to improve prognosis prediction of breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 1267–1285. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, S.A.; Yang, J.; Brooks, M.; Schwaninger, G.; Zhou, A.; Miura, N.; Kutok, J.L.; Hartwell, K.; Richardson, A.L.; Weinberg, R.A. Mesenchyme Forkhead 1 (FOXC2) plays a key role in metastasis and is associated with aggressive basal-like breast cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10069–10074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollier, B.G.; Tinnirello, A.A.; Werden, S.J.; Evans, K.W.; Taube, J.H.; Sarkar, T.R.; Sphyris, N.; Shariati, M.; Kumar, S.V.; Battula, V.L.; et al. FOXC2 expression links epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stem cell properties in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 1981–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werden, S.J.; Sphyris, N.; Sarkar, T.R.; Paranjape, A.N.; LaBaff, A.M.; Taube, J.H.; Hollier, B.G.; Ramirez-Pena, E.Q.; Soundararajan, R.; den Hollander, P.; et al. Phosphorylation of serine 367 of FOXC2 by p38 regulates ZEB1 and breast cancer metastasis, without impacting primary tumor growth. Oncogene 2016, 35, 5977–5988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaimi, S.A.; Chan, S.C.; Rosli, R. Matrix Metallopeptidase 3 Polymorphisms: Emerging genetic Markers in Human Breast Cancer Metastasis. J. Breast Cancer 2020, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argote Camacho, A.X.; Gonzalez Ramirez, A.R.; Perez Alonso, A.J.; Rejon Garcia, J.D.; Olivares Urbano, M.A.; Torne Poyatos, P.; Rios Arrabal, S. Nunez MI: Metalloproteinases 1 and 3 as Potential Biomarkers in Breast Cancer Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.; Kumar, B.V.; Singh, S.; Verma, R. Development of recombinant matrix metalloproteinase-3 based sandwich ELISA for sero-diagnosis of canine mammary carcinomas. J. Immunoass. Immunochem. 2017, 38, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, T.G.P.; Ranft, A.; Esposito, I.; da Silva-Buttkus, P.; Aichler, M.; Baumhoer, D.; Schaefer, K.L.; Ottaviano, L.; Poremba, C.; Jundt, G.; et al. High STEAP1 expression is associated with improved outcome of Ewing’s sarcoma patients. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2185–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, I.M.; Arinto, P.; Lopes, C.; Santos, C.R.; Maia, C.J. STEAP1 is overexpressed in prostate cancer and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia lesions, and it is positively associated with Gleason score. Urol. Oncol. 2014, 32, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Chen, S.L.; Sung, W.W.; Lai, H.W.; Hsieh, M.J.; Yen, H.H.; Su, T.C.; Chiou, Y.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Lin, C.Y.; et al. The Prognostic Role of STEAP1 Expression Determined via Immunohistochemistry Staining in Predicting Prognosis of Primary Colorectal Cancer: A Survival Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, T.G.; Diebold, I.; Esposito, I.; Plehm, S.; Hauer, K.; Thiel, U.; da Silva-Buttkus, P.; Neff, F.; Unland, R.; Muller-Tidow, C.; et al. STEAP1 is associated with the invasive and oxidative stress phenotype of Ewing tumors. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2012, 10, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; Sun, J.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J. STEAP1 Inhibits Breast Cancer Metastasis and Is Associated With Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Procession. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, e195–e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).