Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

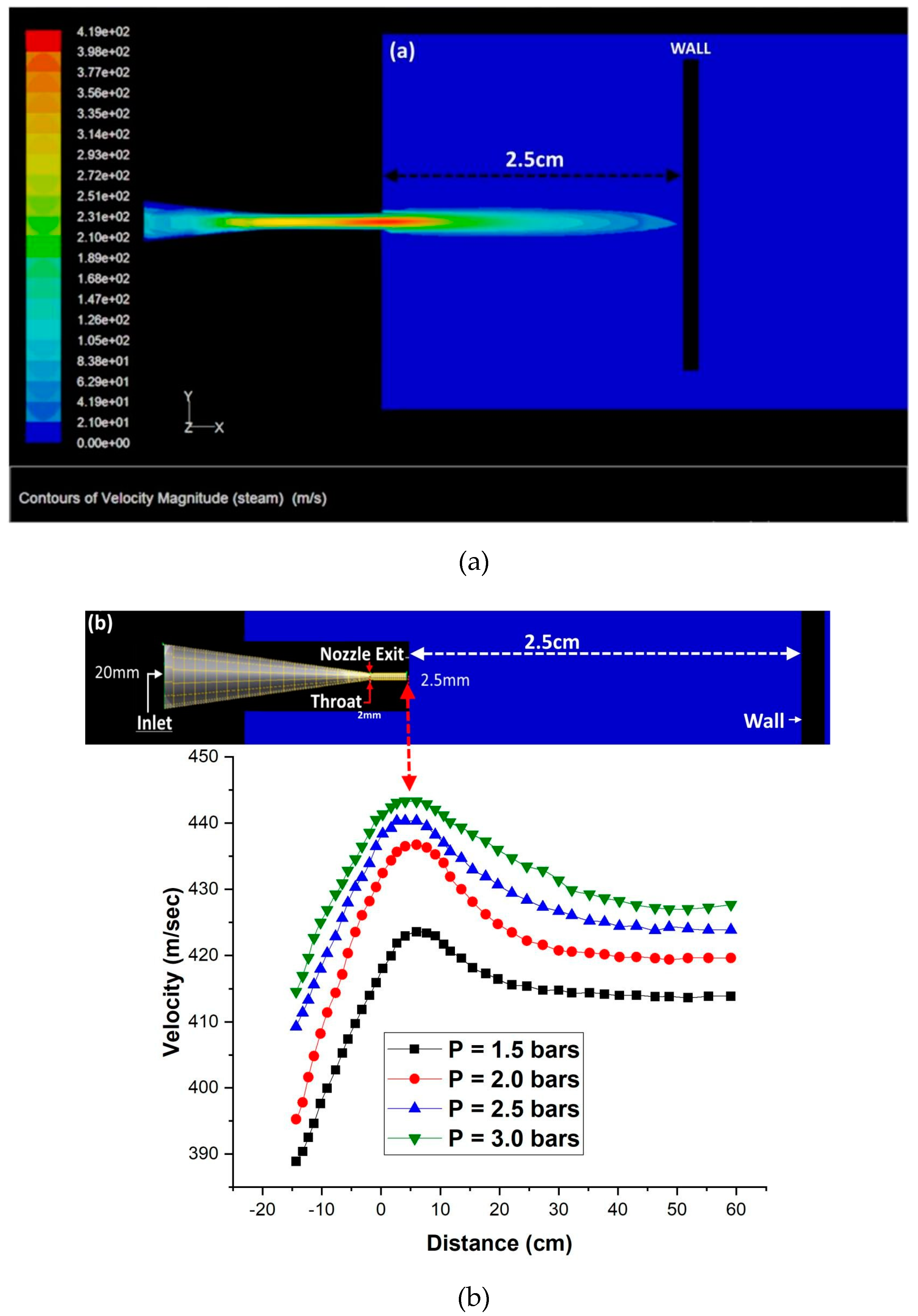

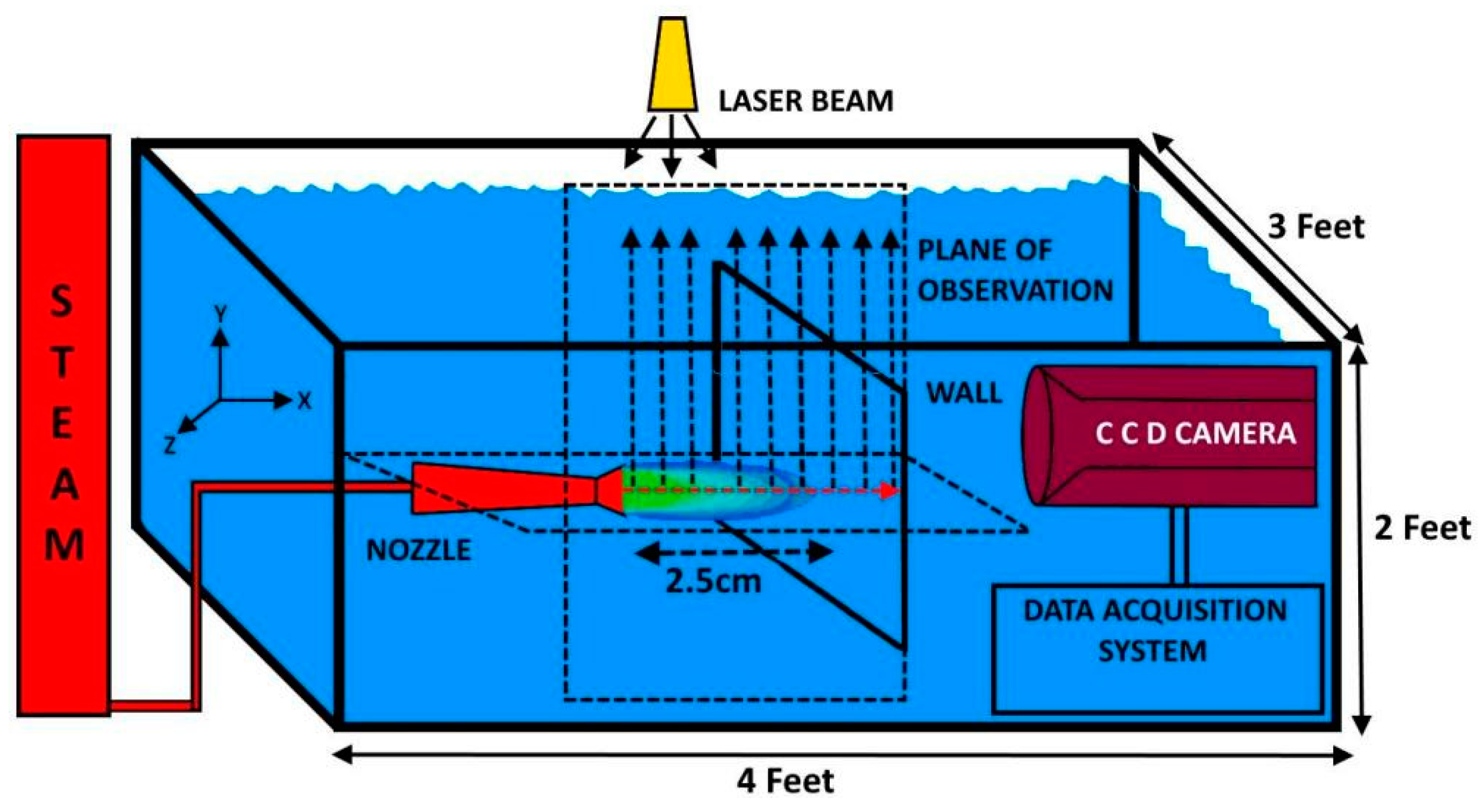

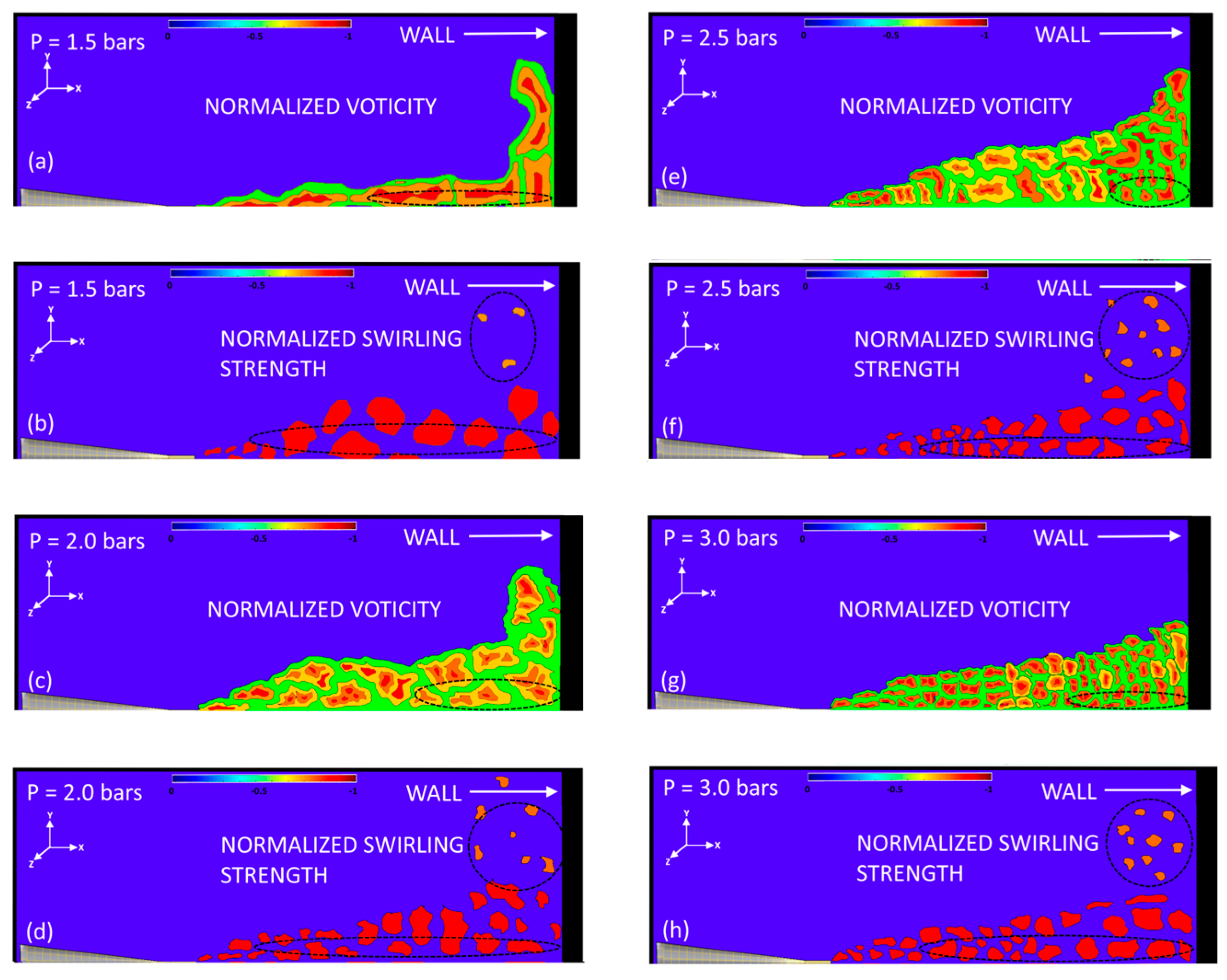

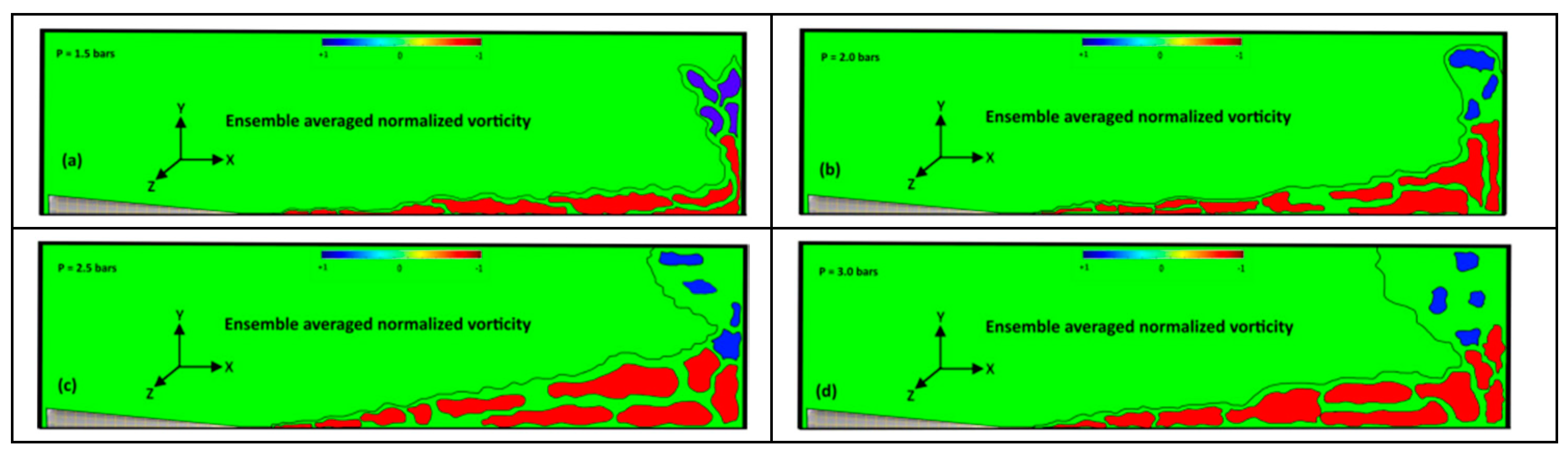

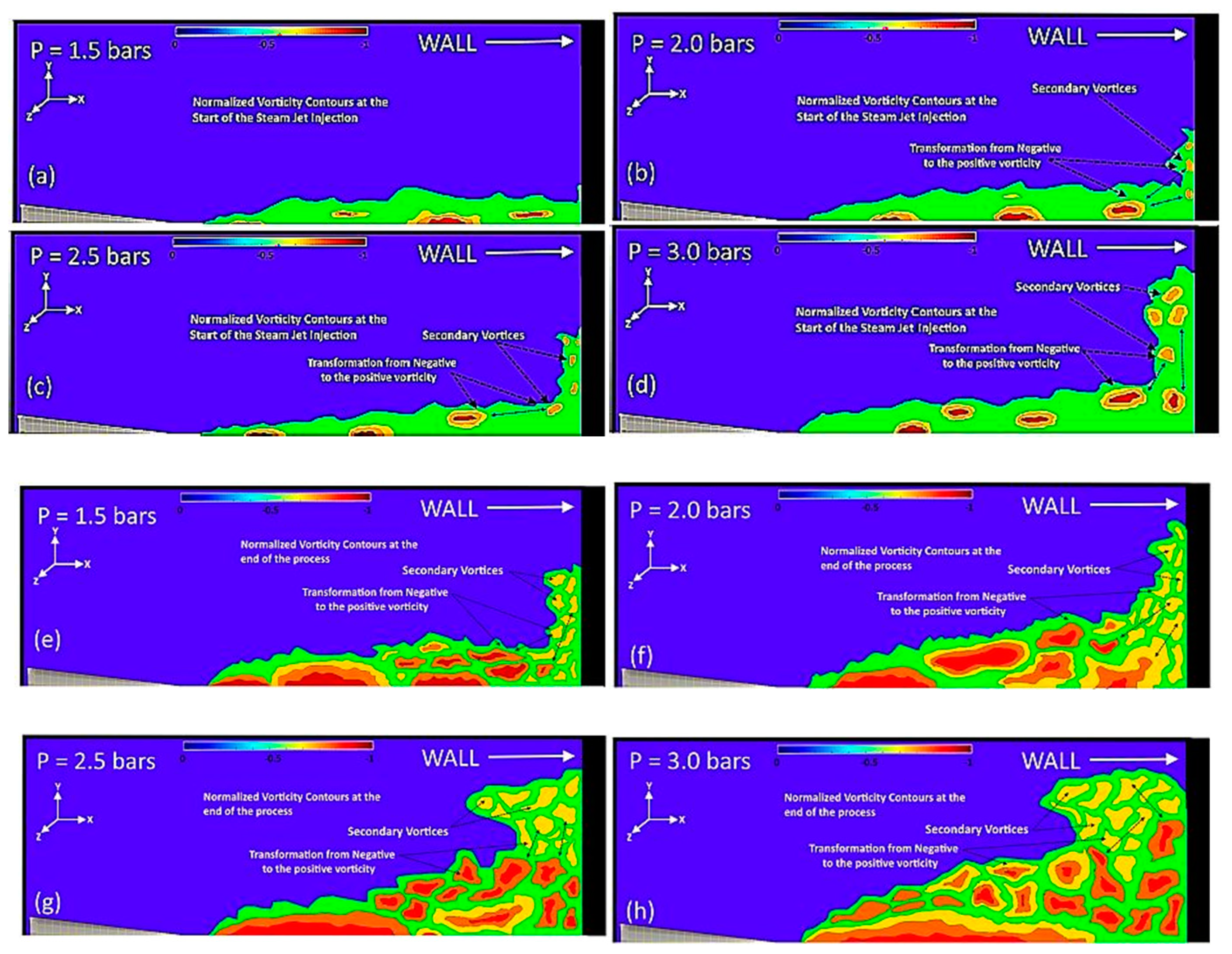

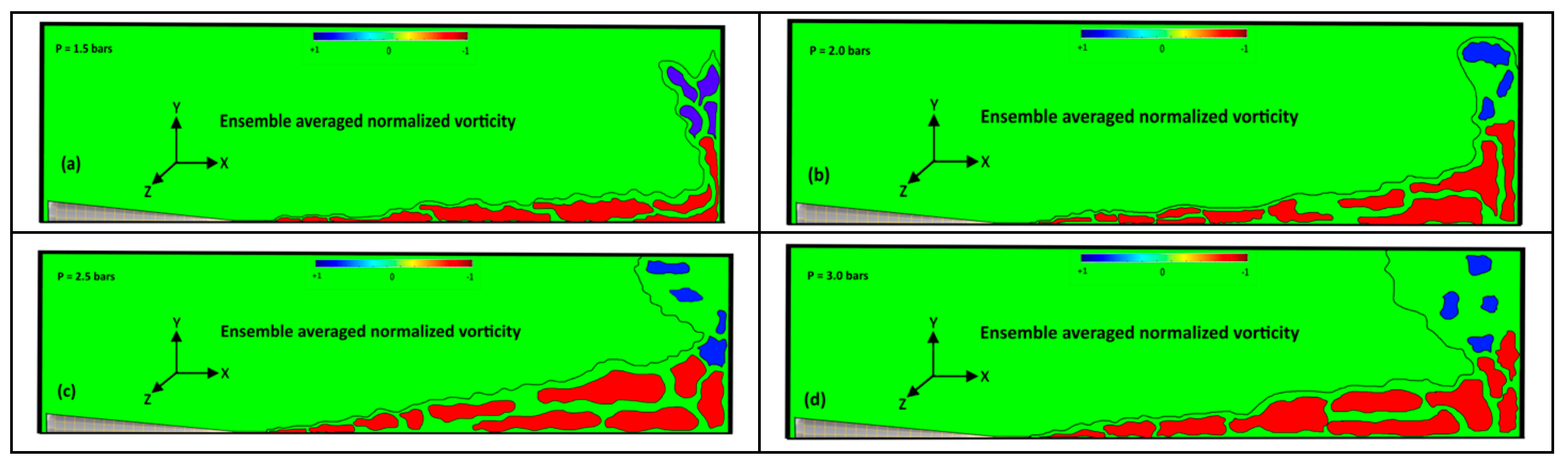

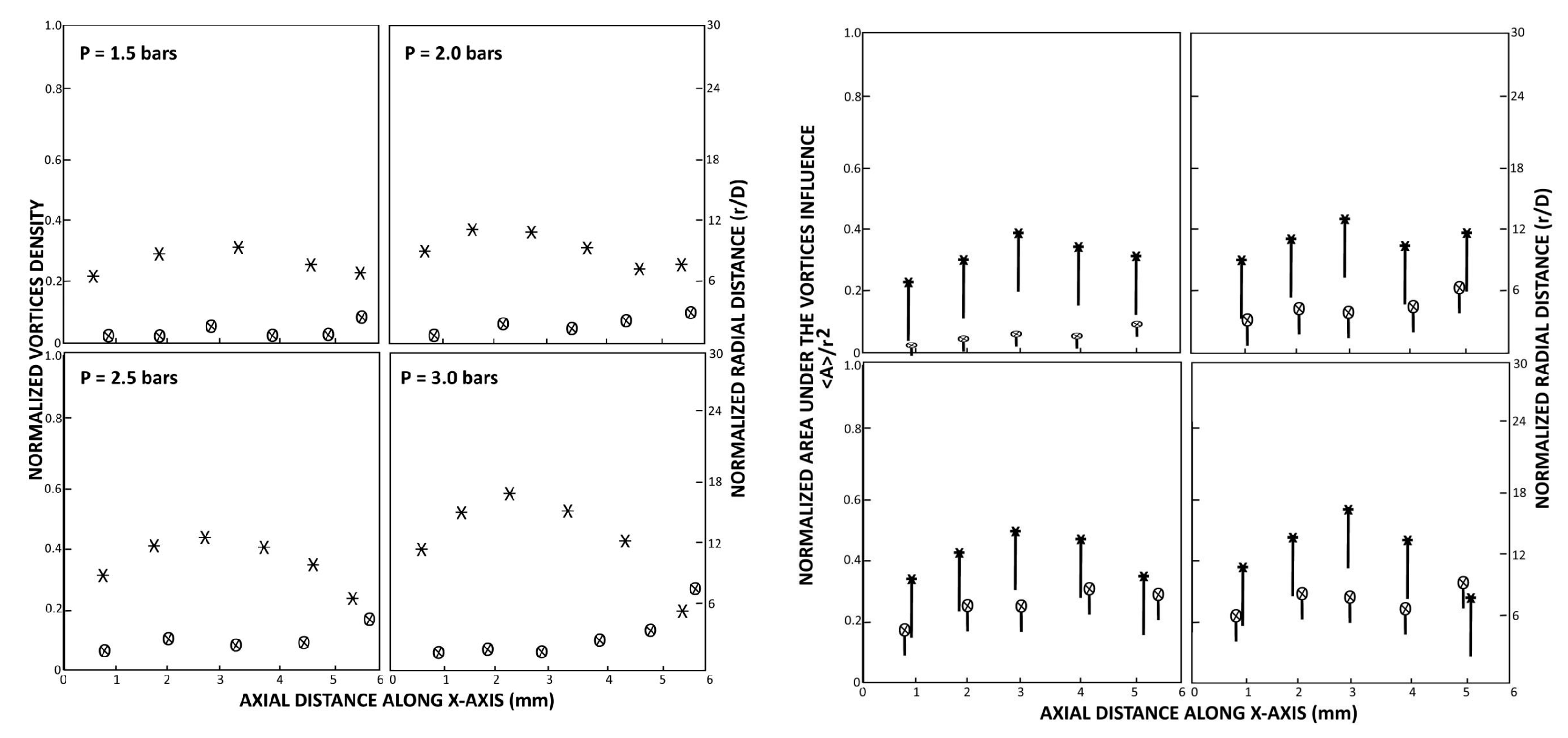

This study presents an experimental investigation into the impingement of a supersonic steam jet onto a wall. Steam was injected through a supersonic nozzle at a varying total pressure of 1.5-3.0 bars, producing a supersonic steam jet at a pressure gradient of 0.5-2.0 bars. The whole fluid domain is comprised of two regions: the jet region and the region near the wall involving the impingement of the supersonic steam jet. Within this region, the transformation of primary vortices into secondary vortices occurs and these vortices expel outward in the radial direction after impingement. Measurements have shown the spreading of the normalized density of the vortical structures along the axial length within the region near the wall. However, the probability density function analysis has indicated that the vortical structures become denser within the impingement region. Whereas subsequent to an impingement of the steam jet onto the wall, along the radial direction, weak traces of their existence in the jet region may be attributed to the vorticity diffusion within the jet region.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Setup

| Phase | Density | Dynami c | Kinem atic | Youn g’s | Poisso n’s | press ure | Tempera ture (0C) | Ultim ate | |

| (kg/m | Viscosit | Viscosi | modu | ratio | (bars | Tensil | |||

| 3) | y | ty | lus | ) | e | ||||

| ((Pa s, Ns/m2) x | ((m2/s)x 10-6) | (GPa) | Strength | ||||||

| 10-3) | (MPa) | ||||||||

| Const | |||||||||

| ant value take Water from | 0.798- | 0.801- | --- | ---- | Outlet press ure=1 bar 250C ---- | ||||

| Steam | Co nstant value taken from Fluent data base | Fluent data base | Fluent data base | --- | --- | Nozzl e Inlet= 1-3bars | 100-1340C [22] | --- | |

| Model Solver: Pressure based Formulation: Implicit | |||||||||

| Multiph ase model |

Scheme: Euler 2 Phase Viscous Model: k-epsilon 2 equations k-epsilon: Realizable |

Near wall treatment: Standard wall function k-epsilon multiphase model: Mixture |

|||||||

| Drag |

Steam-water: Symmetric Heat: Ranz-Marshall Mass transfer: Will be determined by User Defined Function (DCC model) Under relaxation factor: 0.1 Pressure-velocity coupling: Phase coupled SIMPLE Discretization: First order upwind |

||||||||

| Multigrid control |

Cycle type: F- Cycle Termination restriction: 0.1 AGM method stabilization method: Aggregative- BCGSTAB Convergence criteria: 1 e-5 |

||||||||

| Direction of pressure specification method: Normal to the boundary | Turbulence specification method: k-epsilo | ||||||||

2.1. Mathematical Formulations

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Analysis of the Vortices

3.2. Transformation from Negative to Positive Vortices & Their Spatial Occurrence Probability

Conclusions

Acknowledgment

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description |

| L | Axial length (m) |

| r | Radial length (m) |

| D | Nozzle diameter (m) |

| t | Time (s) |

| u | Axial velocity (m/s) |

| B | Sum of external forces |

| Greek symbols | |

| ω | Vorticity |

| ρ | Fluid density (kg/m3) |

| Viscous stress tensor | |

| Optimal in-homogeneous proper orthogonal decomposition (POD) basis function for the axial component of the velocity | |

| Ω | Swirling strength |

| Subscripts | |

| x | Along axial axis |

| r | Along radial axis |

| θ | Ensemble averaged |

References

- P. Bakke, An experimental investigation of a wall jet, J. Fluid Mech. 2 (1957) 467– 472. [CrossRef]

- T. Deng, S. Norris, R.N. Sharma, Numerical investigation on the stability of tunnel smoke stratification under the effect of water spray and longitudinal ventilation, Tunn. Undergr. Sp. Technol. 112 (2021) 103901. [CrossRef]

- J. Lede, J. Villermaux, R. Ouzane, M.A. Hossain, R. Ouahes, Production of hydrogen by simple impingement of a turbulent jet of steam upon a high temperature zirconia surface, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 12 (1987) 3–11. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, J.L. Gaddis, T. Wang, Modeling of heat transfer in a mist/steam impinging jet, J. Heat Transfer 123 (2001) 1086–1092. [CrossRef]

- C.B. Domnick, F.K. Bera, D. Brillert, C. Musch, Modification of a steam valve diffuser for enhanced full load and part load operation using numerical methods, Period. Polytech. Mech. Eng. 60 (2016) 185–192. [CrossRef]

- J. Woisetschläger, H. Jericha, W. Sanz, F. Gollner, Optical investigation of transonic wall-jet film cooling, ASME Cogen Turbo Power 95 (1995).

- M. Shademan, R. Balachandar, V. Roussinova, R. Barron, Round impinging jets with relatively large stand-off distance, Phys. Fluids 28 (2016). [CrossRef]

- B.E. Launder, W. Rodi, The turbulent wall jet, Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 19 (1979) 81–128. [CrossRef]

- Y.M. Chung, K.H. Luo, Unsteady heat transfer analysis of an impinging jet, J. Heat Transfer 124 (2002) 1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- C.J. Hoogendoorn, The effect of turbulence on heat transfer at a stagnation point, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 20 (1977) 1333–1338. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee, S.J. Lee, The effect of nozzle configuration on stagnation region heat transfer enhancement of axisymmetric jet impingement, Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 43 (2000) 3497–3509. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, K. Sanaullah, M. Sobri Takriff, A. Hussain, A. Shah, I. Rafiq Chughtai, Void fraction of supersonic steam jet in subcooled water, Flow Meas. Instrum. 47 (2016) 35–44. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, K. Sanaullah, M.S. Takriff, H. Zen, A.R.H. Rigit, A. Shah, I.R. Chughtai, Numerical and experimental investigations on the physical characteristics of supersonic steam jet induced hydrodynamic instabilities, Asia-Pacific J. Chem. Eng. 11 (2016) 271–283. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, CFD Based Hydrodynamic Parametric Study of Inclined Injected Supersonic Steam into Subcooled Water, in: 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, K. Sanaullah, M.S. Takriff, H. Zen, L.S. Fong, Inclined Injection of Supersonic Steam into Subcooled Water: A CFD Analysis, Adv. Mater. Res. 845 (2014) 101–107. [CrossRef]

- A. Khan, K. Sanaullah, N.U. Haq, Development of a Sensor to Detect Condensation of Super-Sonic Steam, Adv. Mater. Res. 650 (2013) 482–487. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Yule, Large-scale structure in the mixing layer of a round jet, J. Fluid Mech. 89 (1978) 413–432. [CrossRef]

- K. Nishino, M. Samada, K. Kasuya, K. Torii, Turbulence statistics in the stagnation region of an axisymmetric impinging jet flow, Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 17 (1996) 193– 201. [CrossRef]

- N. Zuckerman, N. Lior, Radial slot jet impingement flow and heat transfer on a cylindrical target, J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 21 (2007) 548–561.

- A. Khan, K. Sanaullah, M.S. Takriff, H. Zen, A.R.H. Rigit, A. Shah, I.R. Chughtai, T. Jamil, Pressure stresses generated due to supersonic steam jet induced hydrodynamic instabilities, Chem. Eng. Sci. 146 (2016) 44–63. [CrossRef]

- A. Shah, I.R. Chughtai, M.H. Inayat, Numerical Simulation of Direct-contact Condensation from a Supersonic Steam Jet in Subcooled Water, Chinese J. Chem. Eng. 18 (2010) 577–587. [CrossRef]

- E.B. Entry, STEAM TABLES, A-to-Z Guid. to Thermodyn. Heat Mass Transf. Fluids Eng. (2011). [CrossRef]

- F.R. Hama, Streaklines in a perturbed shear flow, Phys. Fluids 5 (1962) 644–650. [CrossRef]

- I. Gursul, D. Lusseyran, D. Rockwell, On interpretation of flow visualization of unsteady shear flows, Exp. Fluids 9 (1990) 257–266. [CrossRef]

- M.S. Chong, A.E. Perry, B.J. Cantwell, A general classification of three-dimensional flow fields, Phys. Fluids A 2 (1990) 765–777. [CrossRef]

- DALLMANN, U. , On the Footprints of Three-Dimensional Separated Vortex Flows Around Blunt Bodies, AGARD CP 494 (1991).

- J. Zhou, R.J. Adrian, S. Balachandar, Autogeneration of near-wall vortical structures in channel flow, Phys. Fluids 8 (1996) 288–290. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou, R.J. Adrian, S. Balachandar, T.M. Kendall, Mechanisms for generating coherent packets of hairpin vortices in channel flow, J. Fluid Mech. 387 (1999) 353– 396. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Adrian, K.T. Christensen, Z.C. Liu, Analysis and interpretation of instantaneous turbulent velocity fields, Exp. Fluids 29 (2000) 275–290. [CrossRef]

- S. Herpin, M. Stanislas, J. Soria, The organization of near-wall turbulence: A comparison between boundary layer SPIV data and channel flow DNS data, J. Turbul. 11 (2010) 1–30. [CrossRef]

- S.J. Lee, Y.S. Choi, Decrement of spanwise vortices by a drag-reducing riblet surface, J. Turbul. 9 (2008) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- V.K. Natrajan, Y. Wu, K.T. Christensen, Spatial signatures of retrograde spanwise vortices in wall turbulence, J. Fluid Mech. 574 (2007) 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu, K.T. Christensen, Population trends of spanwise vortices in wall turbulence, J. Fluid Mech. 568 (2006) 55–76. [CrossRef]

- W.T. Hambleton, N. Hutchins, I. Marusic, Simultaneous orthogonal-plane particle image velocimetry measurements in a turbulent boundary layer, J. Fluid Mech. 560 (2006) 53–64. [CrossRef]

- K.T. Christensen, Y. Wu, Visualization and characterization of small-scale spanwise vortices in turbulent channel flow, J. Vis. 8 (2005) 177–185. [CrossRef]

- K.T. Christensen, R.J. Adrian, Statistical evidence of hairpin vortex packets in wall turbulence, J. Fluid Mech. 431 (2001) 433–443. [CrossRef]

- C.D. Tomkins, R.J. Adrian, Spanwise structure and scale growth in turbulent boundary layers, J. Fluid Mech. 490 (2003) 37–74. [CrossRef]

- Q. Chen, R.J. Adrian, Q. Zhong, D. Li, X. Wang, Experimental study on the role of spanwise vorticity and vortex filaments in the outer region of open-channel flow, J. Hydraul. Res. 52 (2014) 476–489. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, D. Li, R. Bai, X. Wang, Comparison of swirling strengths derived from two- and three-dimensional velocity fields in channel flow, AIP Adv. 8 (2018) 055302. [CrossRef]

- MATLAB, Statistics for labeled regions - Simulink, (n.d.).

- R.L. (Ronald L. Panton, Incompressible flow, n.d.

- S. Lu, G. Tsechpenakis, D.N. Metaxas, M.L. Jensen, J. Kruse, Blob analysis of the head and hands: A method for deception detection, in: Proc. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst. Sci., 2005: p. 20. [CrossRef]

- S. Corrsin, A.L. Kistler, Free-Stream Boundaries of Turbulent Flows, Johns Hopkins Univ.; Balt. MD, United States (1955).

- J.L. Henk Tennekes, Hendrik Tennekes, John Leask Lumley, A First Course in Turbulence - Emeritus Professor of Aeronautical Engineering Henk Tennekes, Hendrik Tennekes, John Leask Lumley, J. L... Lumley - Google Books, MIT Press., 1972.

- F.H. Clauser, The structure of turbulent shear flow, Nature 179 (1957) 60. [CrossRef]

- N.N. Smirnov, N.I. Zverev, M. V. Tyurnikov, Two-phase flow behind a shock wave with phase transitions and chemical reactions, Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 13 (1996) 11– 20. [CrossRef]

- R. van Hout, V. Rinsky, Y.G. Grobman, Experimental study of a round jet impinging on a flat surface: Flow field and vortex characteristics in the wall jet, Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 70 (2018) 41–58. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).