Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

20 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Earth Air Heat Exchangers (EAHEs) provide a compelling solution for improving building en-ergy efficiency by harnessing the stable subterranean temperature to pre-treat ventilation air. This comprehensive review delves into the foundational principles of EAHE operation, meticu-lously examining heat and mass transfer phenomena at the ground-air interface. The study me-ticulously investigates the impact of key factors, including soil characteristics, climatic condi-tions, and crucial system design parameters, on overall system performance. Beyond independ-ent applications, this review explores the synergistic integration of EAHEs with a diverse array of renewable energy technologies, such as air source heat pumps, photovoltaic thermal (PVT) panels, wind turbines, fogging systems, water spray channels, solar chimneys, and photovoltaic systems. This exploration aims to clarify the potential of hybrid systems in achieving enhanced energy efficiency, minimizing environmental impact, and improving the overall robustness of the system.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. EAHE Fundamentals

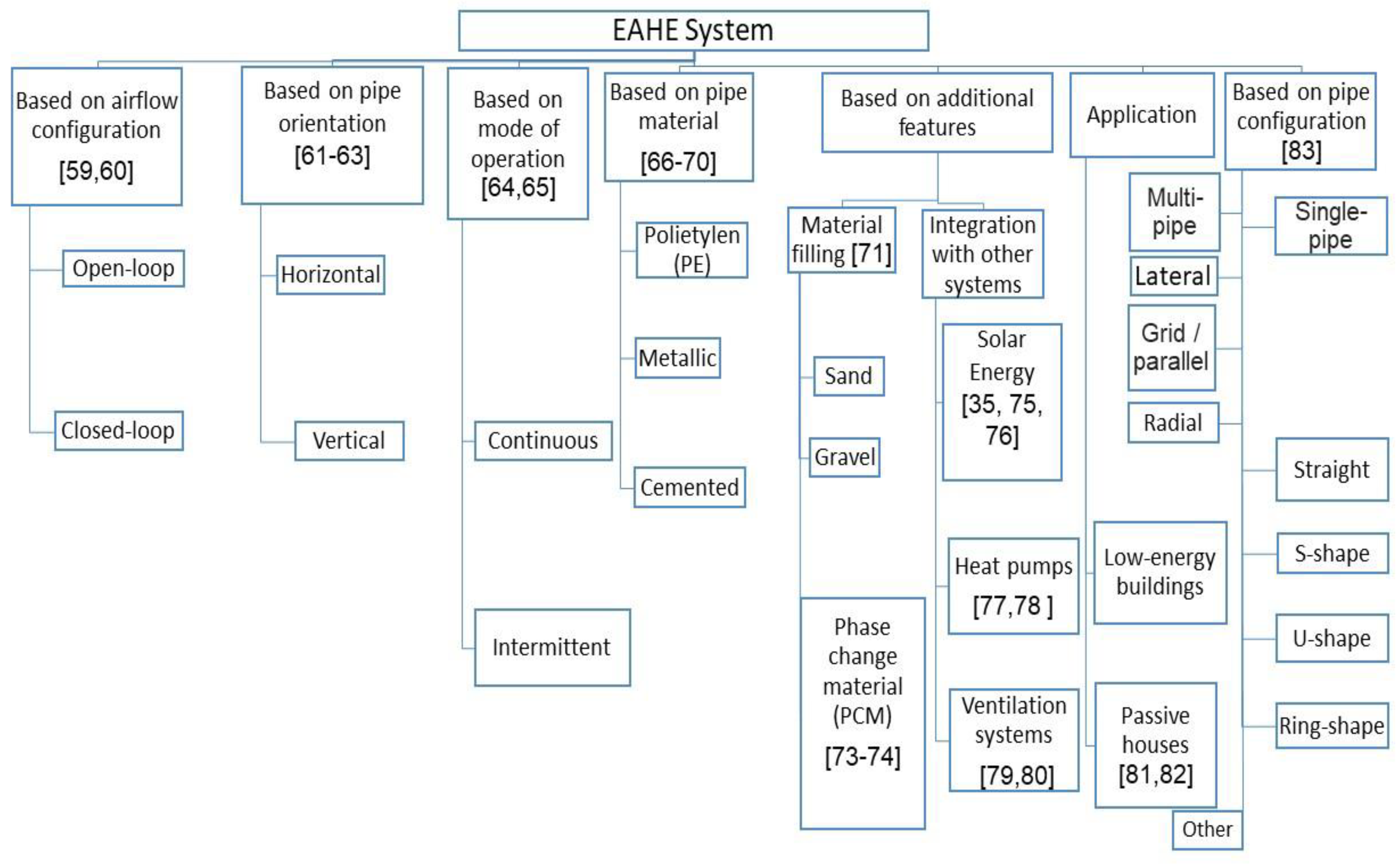

3.1. Classification of EAHE Systems

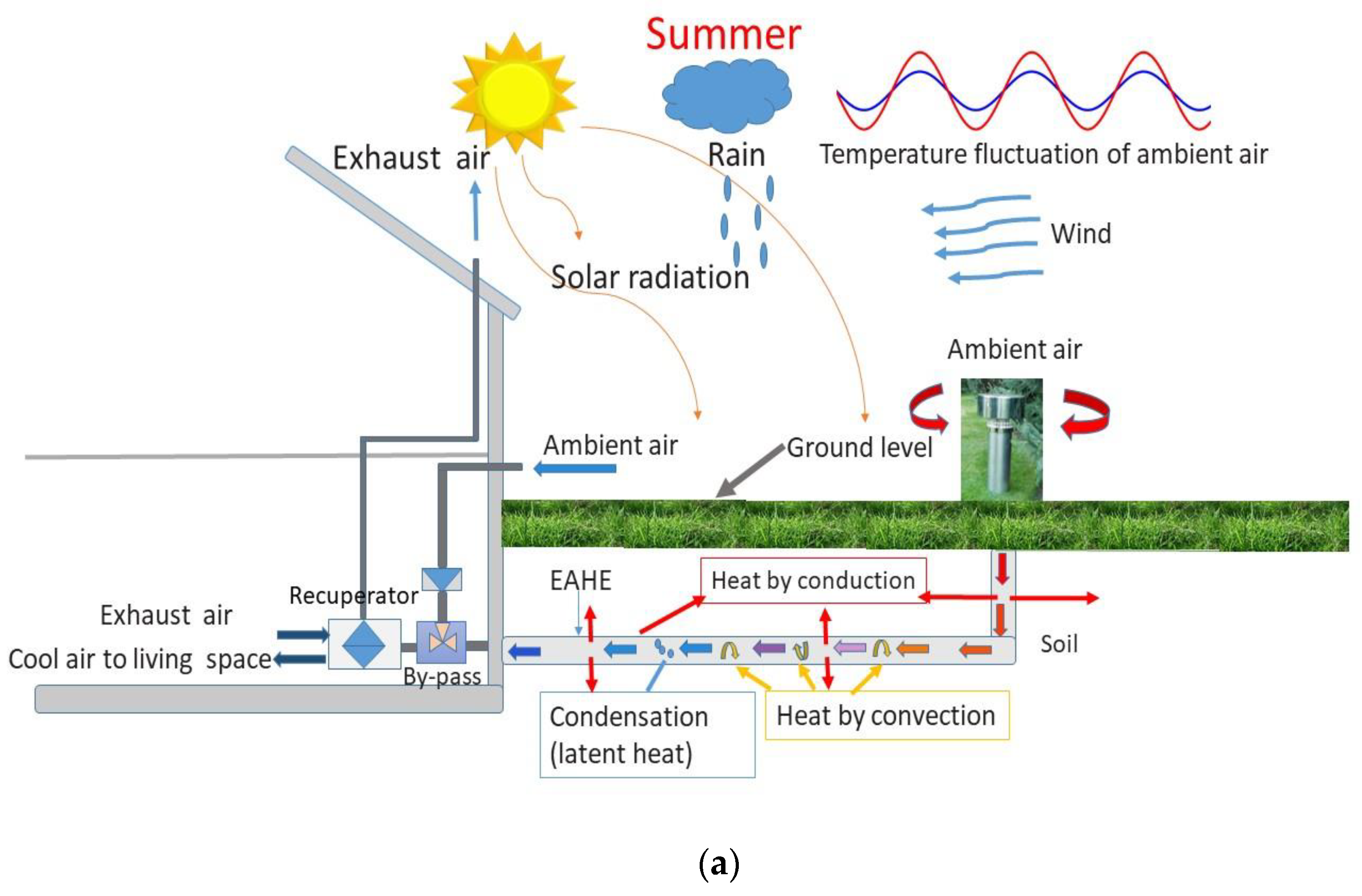

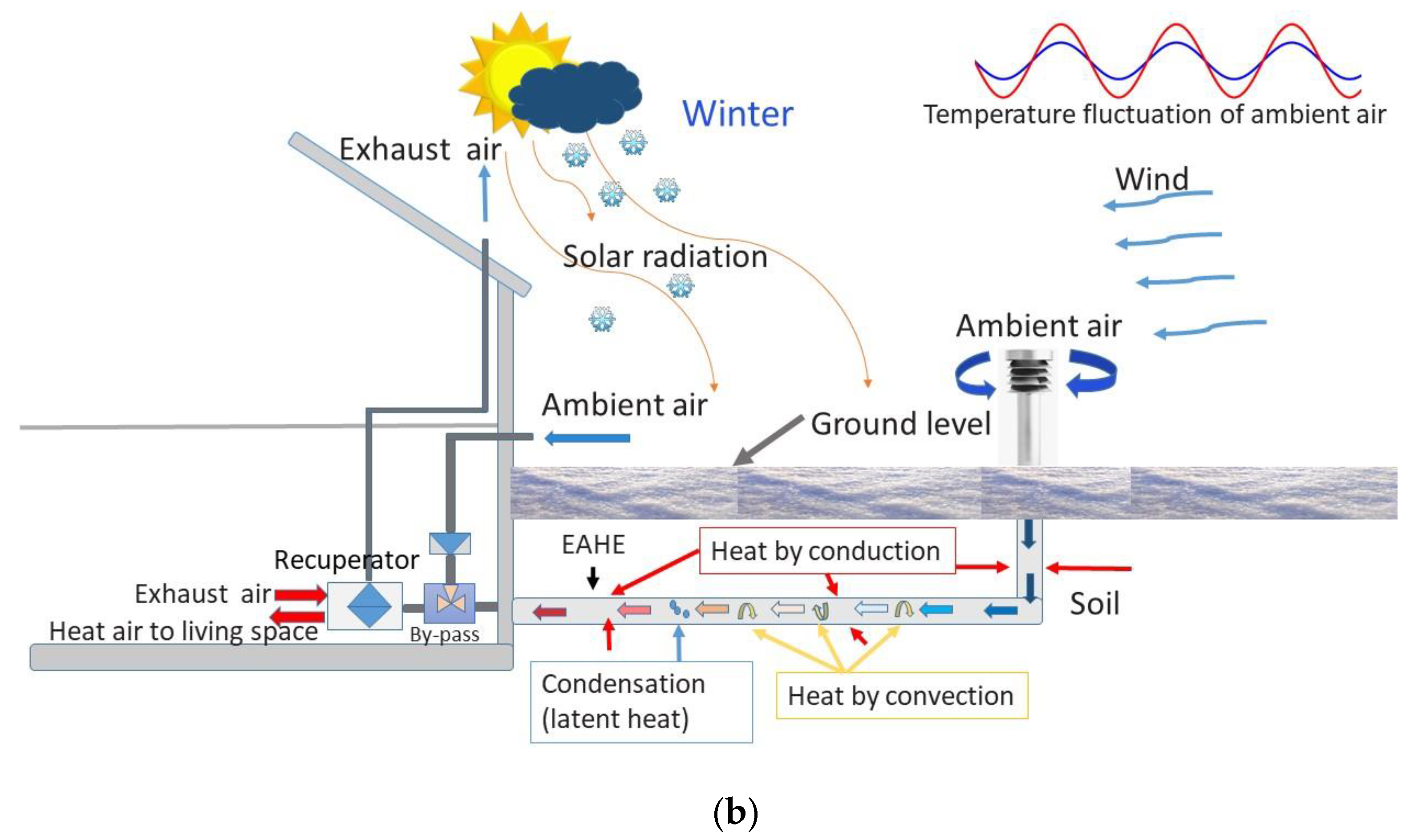

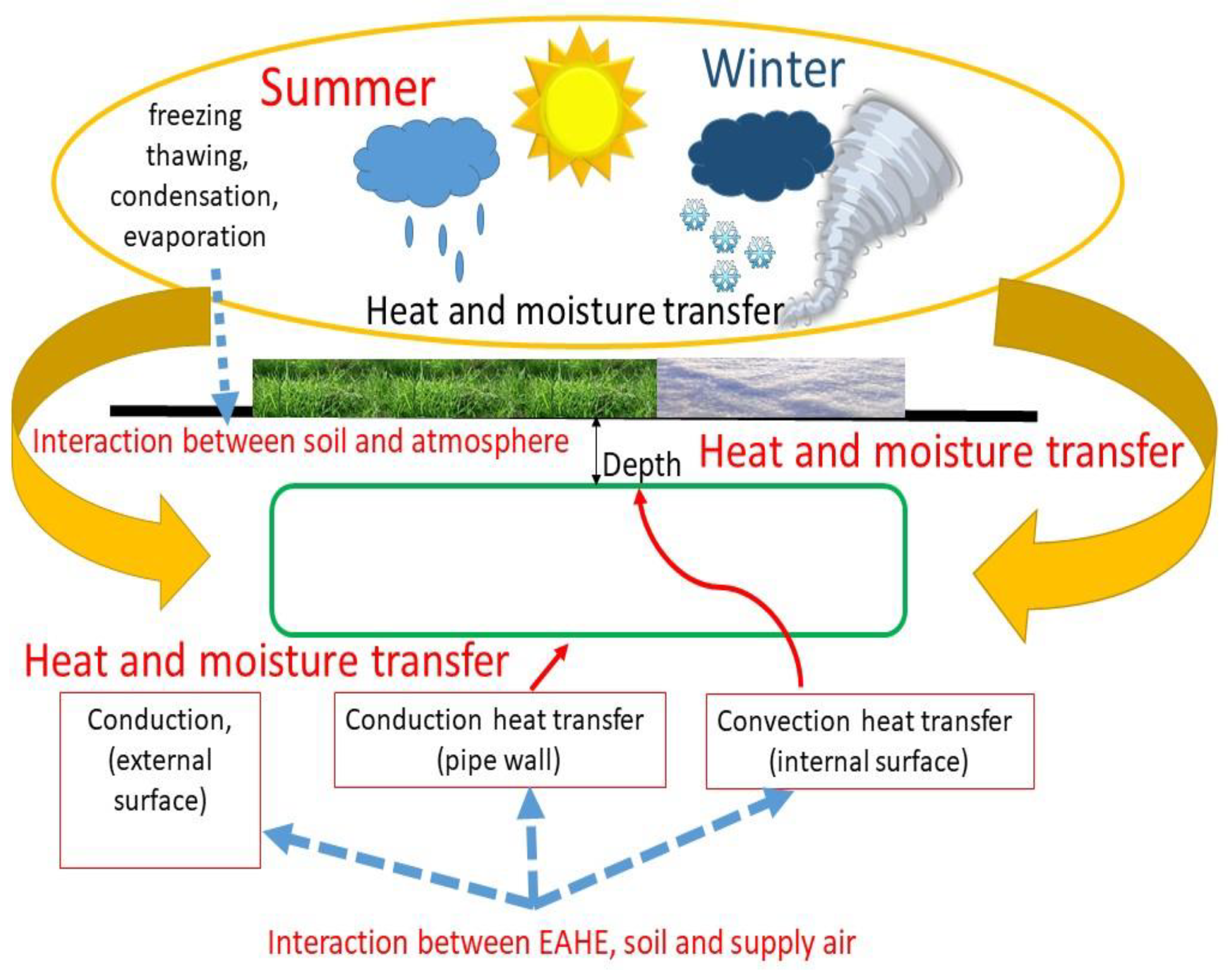

3.2. Heat and Mass Transfer in Earth-Air Heat Exchangers

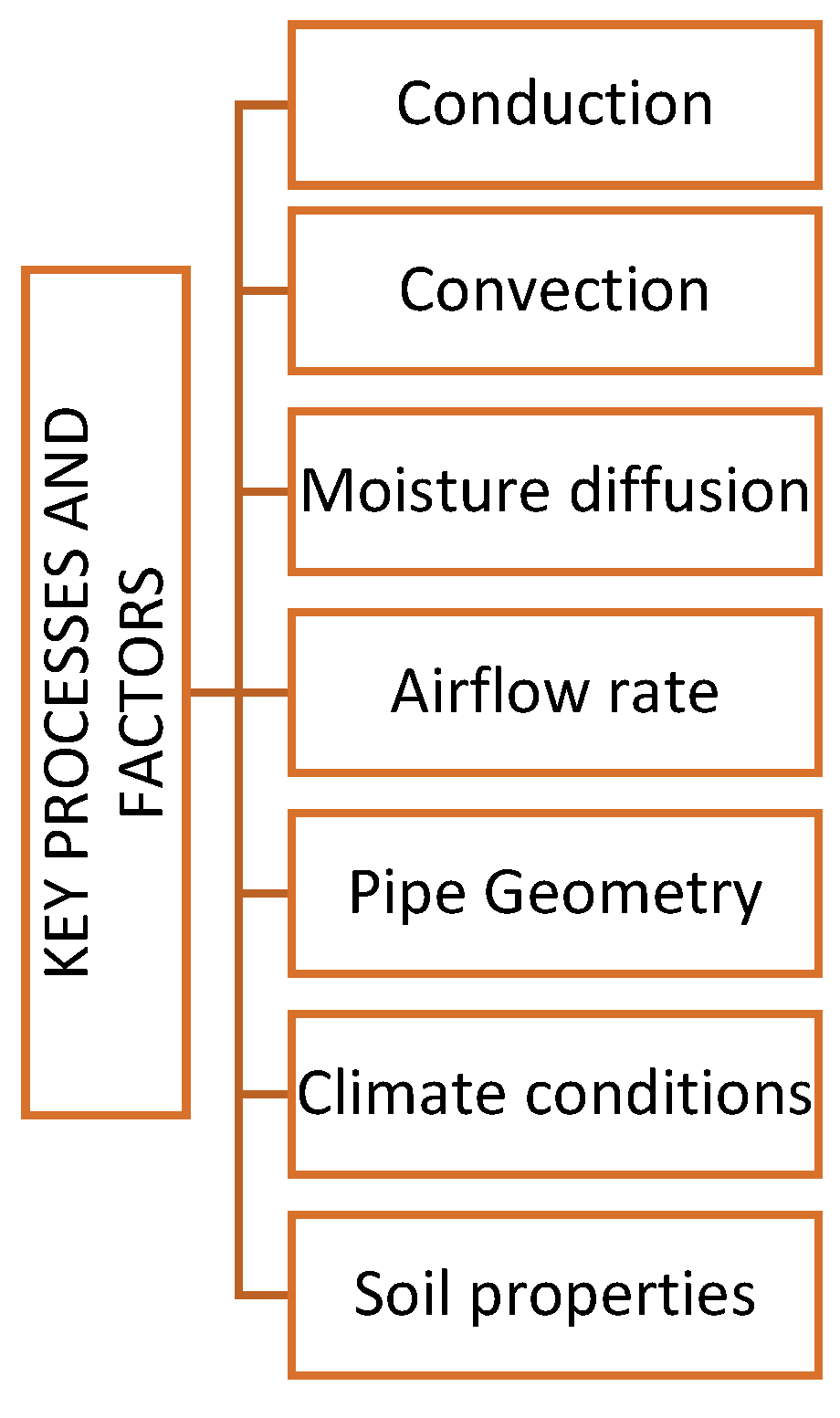

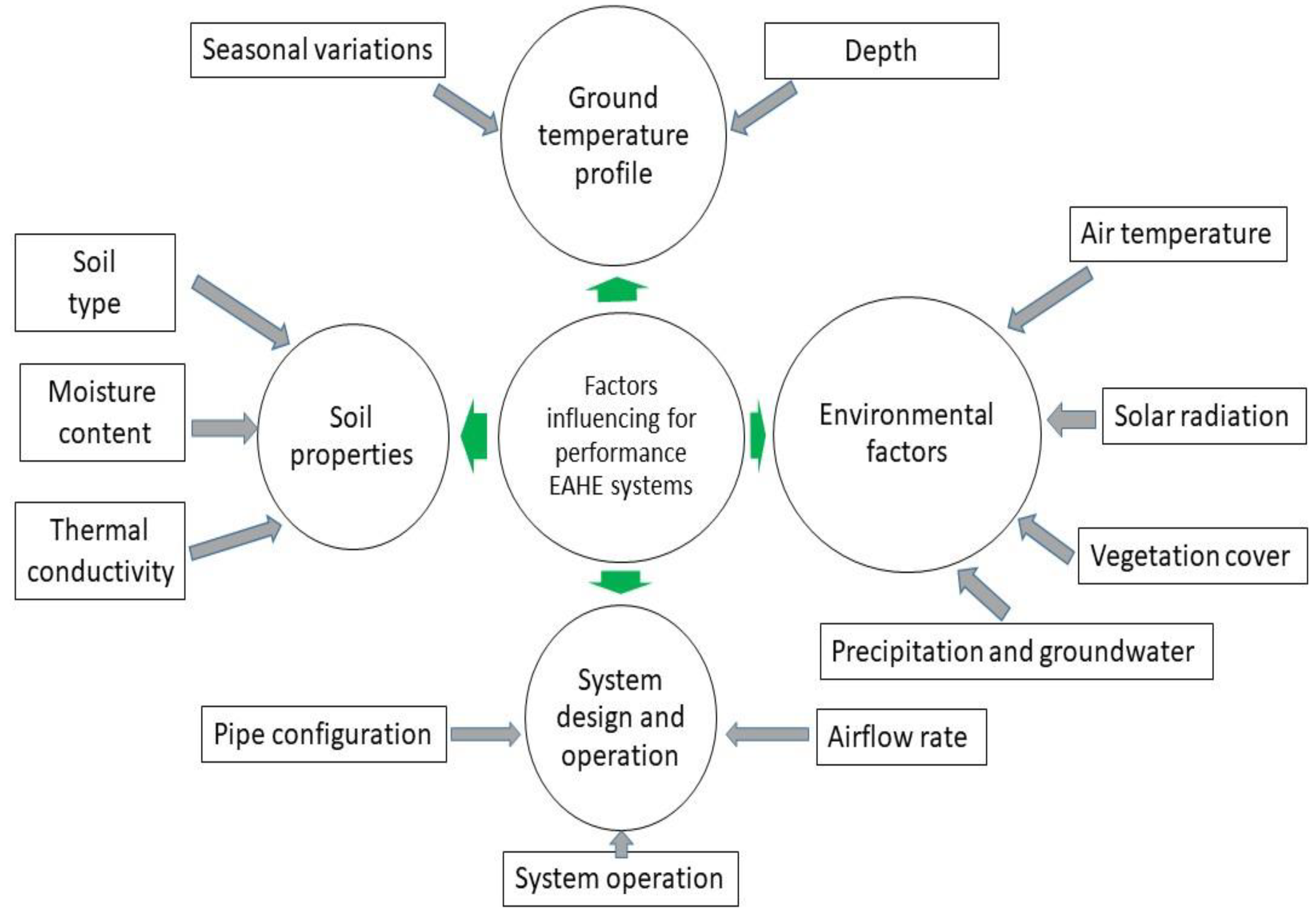

3.3. Factors Influencing for Performance of Earth Air Heat Exchangers

4. Integration of EAHE with Renewable Energy Sources

4.1. Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers (EAHEs) Integrating with Air-Source Heat Pumps (ASHPs)

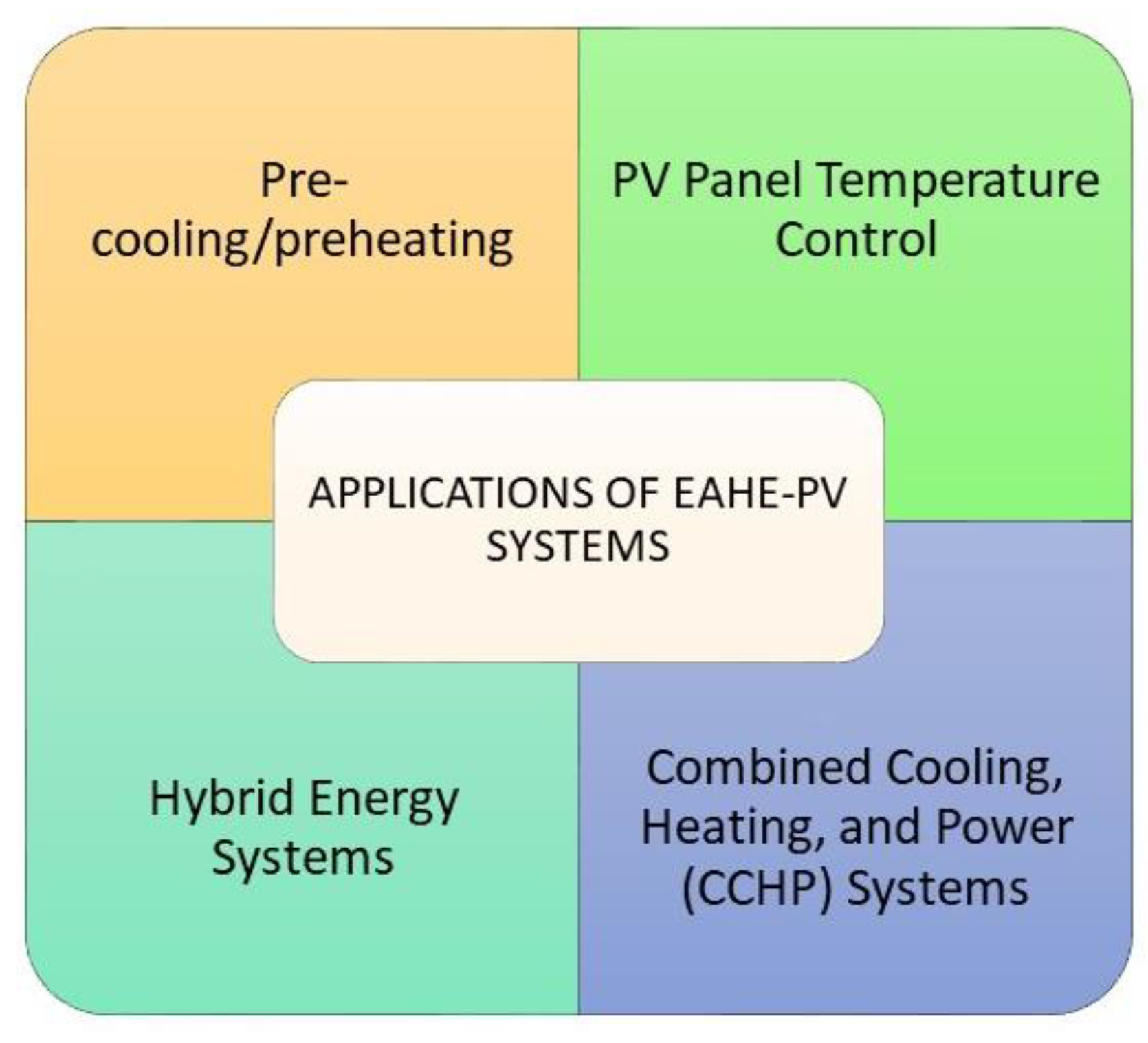

4.1. Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers (EAHEs) Integrating with Photovoltaic Systems

4.2. Energy Systems Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers (EAHEs) Integrated with Solar Energy

4.3. Advanced Applications: Cooling, Heating, and Power Systems

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ferdinando Salata, Serena Falasca, Virgilio Ciancio, Gabriele Curci, Pieter de Wilde, Climate-change related evolution of future building cooling energy demand in a Mediterranean Country, Energy and Buildings, Volume 290, 2023, 113112, ISSN 0378-7788. [CrossRef]

- Deroubaix, A., Labuhn, I., Camredon, M., Gaubert, B., Monerie, P. A., Popp, M., ... & Siour, G. (2021). Large uncertainties in trends of energy demand for heating and cooling under climate change. Nature communications, 12(1), 5197.

- United Nations Environment Programme (2024). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction: Beyond foundations: Mainstreaming sustainable solutions to cut emissions from the buildings sector. Nairobi. [CrossRef]

- Arowoiya, V.A.; Onososen, A.O.; Moehler, R.C.; Fang, Y. Influence of Thermal Comfort on Energy Consumption for Building Occupants: The Current State of the Art. Buildings 2024, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA (2023), Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023, Licence: CC BY 4.

- IEA (2024), Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2024, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/southeast-asia-energy-outlook-2024, Licence: CC BY 4.0.

- M. Santamouris, K. Vasilakopoulou, Present and future energy consumption of buildings: Challenges and opportunities towards decarbonisation, e-Prime - Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy, Volume 1, 2021, 100002, ISSN 2772-6711. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772671121000024. [CrossRef]

- Damm, A., Köberl, J., Prettenthaler, F., Rogler, N., & Töglhofer, C. (2017). Impacts of + 2 °C global warming on electricity demand in Europe. Climate Services, 7, 12–30. [CrossRef]

- IEA. (2022). World Energy Outlook. License: CC BY 4.0 (report); CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Annex A). IEA, Paris. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022. Accessed 15 May 2023.

- Gonçalves, A.C.R., Costoya, X., Nieto, R. et al. Extreme weather events on energy systems: a comprehensive review on impacts, mitigation, and adaptation measures. Sustainable Energy res. 11, 4 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Danny H.W. Li, Liu Yang, Joseph C. Lam, Impact of climate change on energy use in the built environment in different climate zones – A review, Energy, Volume 42, Issue 1, 2012, Pages 103-112, ISSN 0360-5442, Danny H.W. Li, Liu Yang, Joseph C. Lam, Impact of climate change on energy use in the built environment in different climate zones – A review, Energy, Volume 42, Issue 1, 2012, Pages 103-112, ISSN 0360-5442,. [CrossRef]

- Ferdinando Salata, Serena Falasca, Virgilio Ciancio, Gabriele Curci, Pieter de Wilde, Climate-change related evolution of future building cooling energy demand in a Mediterranean Country, Energy and Buildings, Volume 290, 2023, 113112, ISSN 0378-7788, (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778823003420). [CrossRef]

- Kai Gao, K.F. Fong, C.K. I: Lee, Kevin Ka-Lun Lau, Edward Ng, Balancing thermal comfort and energy efficiency in high-rise public housing in Hong Kong. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652624001884), 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M. Chapter 2—Energy Consumption and Environmental Quality of the Building Sector. In Minimizing Energy Consumption, Energy Poverty and Global and Local Climate Change in the Built Environment: Innovating to Zero; Santamouris, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Yu, H.; Sun, Q.; Tam, V.W.Y. A critical review of occupant energy consumption behavior in buildings: How we got here, where we are, and where we are headed. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 182, 113396 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisoniya, T.S. , Kumar, A., & Baredar, P.V. (2013). Experimental and analytical studies of earth–air heat exchanger (EAHE) systems in India: A review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 19, 238-246.

- Peñaloza Peña, S.A.; Jaramillo Ibarra, J.E. Potential Applicability of Earth to Air Heat Ex-changer for Cooling in a Colombian Tropical Weather. Buildings 2021, 11, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H.P. Díaz-Hernández, E.V. H.P. Díaz-Hernández, E.V. Macias-Melo, K.M. Aguilar-Castro, I. Hernández-Pérez, J. Xamán, J. Serrano-Arellano, L.M. López-Manrique, Experimental study of an earth to air heat exchanger (EAHE) for warm humid climatic conditions, Geothermics, Volume 84, 2020, 101741, ISSN 0375-6505. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0375650519301208)],. [CrossRef]

- Bughio, M.; Ba-hale, S.; Mahar, W.A.; Schuetze, T. Parametric Performance Analysis of the Cooling Poten-tial of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchangers in Hot and Humid Climates. Energies 2022, 15, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Gang, W. Utiliza-tion of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger to Pre-Cool/Heat Ventilation Air and Its Annual En-ergy Performance Evaluation: A Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SeyedAli Mohammadi, Mohammad Hossein Jahang-ir, Numerical investigation of the saturating soil layers' effect on air temperature drops along the pipe of Earth-Air Heat Exchanger systems in heating applications, Geothermics, Volume 123, 2024, 103109, ISSN 0375-6505. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0375650524001962); [CrossRef]

- Yingjun Yue, Zengfeng Yan, Pingan NI, Fuming Lei, Guojin Qin, Enhancing the performance of earth-air heat exchanger: A flexible multi-objective optimization framework, Applied Thermal Engineering, Volume 244, 2024, 122718, ISSN 1359-4311. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1359431124003867); [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y. , Yan, Z., Ni, P., Lei, F., & Yao, S. (2024). Machine learning-based multi-performance prediction and analysis of Earth-Air Heat Exchanger. Renewable Energy, 227, 120550.

- Xiao, J. , & Li, J. (2024). Influence of different types of pipes on the heat exchange performance of an earth-air heat exchanger. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 55, 104116.

- Xiao, J. , Wang, Q., Wang, X., Hu, Y., Cao, Y., & Li, J. (2023). An earth-air heat exchanger integrated with a greenhouse in cold-winter and hot-summer regions of northern China: Modeling and ex-perimental analysis. Applied Thermal Engineering, 232, 120939.

- Dewangan, C. , Shukla, A. K., Salhotra, R., & Dewan, A. (2024). Analysis of an earth-to-air heat exchanger for enhanced residential thermal comfort. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 43(3), e14346.

- Ahsan, T. A. , Rahman, M. S., & Ahamed, M. S. (2025). Geothermal energy application for greenhouse microclimate management: A review. Geothermics, 127, 103209.

- Kazem, H. A. , Chaichan, M. T., Al-Waeli, A. H., Sopian, K., Alnaser, N. W., & Alnaser, W. E. (2024). Energy Enhancement of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic/Thermal Systems: A Systematic Review. Solar Compass, 100093.

- Ma, Q. , Qian, G., Yu, M., Li, L., & Wei, X. (2024). Performance of windcatchers in improving indoor air quality, thermal comfort, and energy efficiency: A review. Sustainability, 16(20), 9039.

- Hu, Z. , Yang, Q., Tao, Y., Shi, L., Tu, J., & Wang, Y. (2023). A review of ventilation and cooling systems for large-scale pig farms. Sustainable Cities and Society, 89, 104372.

- Castro, R. P. , Dinho da Silva, P., & Pires, L. C. C. (2024). Advances in Solutions to Improve the Energy Performance of Agricultural Greenhouses: A Comprehensive Review. Applied Sciences (2076-3417), 14(14).

- Vahid Vakiloroaya, Bijan Samali, Ahmad Fakhar, Kambiz Pishghadam, A review of dif-ferent strategies for HVAC energy saving, Energy Conversion and Management, Volume 77, 2014, Pages 738-754, ISSN 0196-8904. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0196890413006584), ]. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Meng, Q.; Liu, X. A Ventilation Experimental Study of Thermal Performance of an Urban Underground Pipe Rack. Energy Build. 2021, 241, 110852 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jimenez-Bescos, C.; Calautit, J.K.; Yao, J. Evaluating the Energy-Saving Potential of Earth-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHX) for Passivhaus Standard Buildings in Different Cli-mates in China. Energy Build. 2023, 288, 113005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikra, G. , Darmanto, P. S., & Astina, I. M. (2024). A review of solar chimney-earth air heat exchanger (SCEAHE) system integration for thermal comfort building. Journal of Building Engineering, 111484.

- Azzi, A. , Tabaa, M., Chegari, B., & Hachimi, H. (2024). Balancing Sustainability and Comfort: A Holistic Study of Building Control Strategies That Meet the Global Standards for Efficiency and Thermal Comfort. Sustainability, 16(5), 2154.

- Acharya, P. , Sharma, A., Singh, Y., & Sirohi, R. (2024). Passive Cooling Strategies Towards the Sustainability of Livestock Building-An Overview. The Indian Veterinary Journal, 101(03), 17-26.

- Shukla, B. K. , Pandey, A. K., Singh, A., Singh, D., & Anas, M. A holistic review on energy-efficient green buildings considering environmental, economical, and technical factors. Clean Energy, 68-85.

- Bosu, I. , Mahmoud, H., Ookawara, S., & Hassan, H. (2023). Applied single and hybrid solar energy techniques for building energy consumption and thermal comfort: A comprehensive review. Solar Energy, 259, 188-228.

- Amin Shahsavar, Müslüm Arıcı, Multi-objective energy and exergy optimization of hybrid building-integrated heat pipe photovoltaic/thermal and earth air heat exchanger system using soft computing technique, Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, Volume 148, 2023, Pages 293-304, ISSN 0955-7997. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0955799722004854). [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Arriola, J. , Velázquez-Limón, N., Aguilar-Jiménez, J.A. et al. Air Conditioning of an Off-Grid Remote School with an Earth to air Heat Exchanger Coupled Indirectly to a Solar Cooling System. Int J Environ Res 18, 112 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Di Qin, Jiang Liu, Guoqiang Zhang, A novel solar-geothermal system integrated with earth–to–air heat exchanger and solar air heater with phase change material—numerical modelling, experimental calibration and parametrical analysis, Journal of Building Engineering, Volume 35, 2021, 101971, ISSN 2352-7102. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352710220336032). [CrossRef]

- Xin Guo, Haibin Wei, Xiao He, Jinhui Du, Dong Yang, Experimental evaluation of an earth–to–air heat exchanger and air source heat pump hybrid indoor air conditioning system, Energy and Buildings, Volume 256, 2022, 111752, ISSN 0378-7788. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378778821010367). [CrossRef]

- C. Baglivo, P.M. C. Baglivo, P.M. Congedo, D. Laforgia Air cooled heat pump coupled with horizontal air-ground heat exchanger (haghe) for zero energy buildings in the mediterranean climate Energy Procedia, 140 (2017), pp. 2-12, 10.1016/j.egypro.2017.11.

- S.L. Do, J.C. S.L. Do, J.C. Baltazar, J. Haberl Potential cooling savings from a ground-coupled return-air duct system for residential buildings in hot and humid climates Energy Build., 103 (2015), pp. 206-215, 10.1016/j.enbuild.2015.05.

- Soni, S. K. , Pandey, M., & Bartaria, V. N. (2016). Hybrid ground coupled heat exchanger systems for space heating/cooling applications: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 60, 724-738.

- Yang, L. H. , Huang, B. H., Hsu, C. Y., and Chen, S. L. 2019. Performance analysis of an earth–air heat exchanger integrated into an agricultural irrigation system for a greenhouse environmental temperature-control system. Energy and Buildings, 202, 109381.

- Soares, N. , Rosa, N., Monteiro, H., & Costa, J. J. (2021). Advances in standalone and hybrid earth-air heat exchanger (EAHE) systems for buildings: A review. Energy and Buildings, 253, 111532.

- Anshu, K. , Kumar, P., & Pradhan, B. (2023). Numerical simulation of stand-alone photovoltaic integrated with earth to air heat exchanger for space heating/cooling of a residential building. Renewable Energy, 203, 763-778.

- Ali, B. M. , & Akkaş, M. (2023). The Green Cooling Factor: Eco-Innovative Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning Solutions in Building Design. Applied Sciences, 14(1), 195.

- D'agostino, D. , Greco, A., Masselli, C., & Minichiello, F. (2020). The employment of an earth-to-air heat exchanger as pre-treating unit of an air conditioning system for energy saving: A comparison among different worldwide climatic zones. Energy and Buildings, 229, 110517.

- Serageldin, A. A. , Abdeen, A., Ahmed, M. M., Radwan, A., Shmroukh, A. N., & Ookawara, S. (2020). Solar chimney combined with earth to-air heat exchanger for passive cooling of residential buildings in hot areas. Solar Energy, 206, 145-162.

- Agarwal, S. K. , & Batista, R. C. (2023). Enhancement of building thermal performance: A comparative analysis of integrated solar chimney and geothermal systems. Journal of Sustainability for Energy, 2(2), 91-108.

- El-Said, E. M., Sharaf, M. A., Aljabr, A., & Marzouk, S. A. (2024). Enhancing the performance of an earth air heat exchanger with novel pipe configurations. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 110, 109630.

- Rosa, N. , Soares, N., Costa, J. J., Santos, P., & Gervásio, H. (2020). Assessment of an earth-air heat exchanger (EAHE) system for residential buildings in warm-summer Mediterranean climate. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 38, 100649.

- Hasan, N. , Arif, M., & Khader, M. A. (2021). Earth Air Tunnel Heat Exchanger for Building Cooling and Heating. In Heat Transfer-Design, Experimentation and Applications. IntechOpen.

- Mitha, S. B. , & Omarsaib, M. (2024). Emerging technologies and higher education libraries: a bibliometric analysis of the global literature. Library Hi Tech, (ahead-of-print).

- Van Eck, N. , & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. scientometrics, 84(2), 523-538.

- Ahmad, S. N. , & Prakash, O. (2022). A review on modelling, experimental analysis and parametric effects of earth–air heat exchanger. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 8(2), 1535-1551.

- Agrawal, K. K. , Misra, R., Agrawal, G. D., Bhardwaj, M., & Jamuwa, D. K. (2019). Effect of different design aspects of pipe for earth air tunnel heat exchanger system: A state of art. International Journal of Green Energy, 16(8), 598-614.

- Noman, S. , Tirumalachetty, H., & Athikesavan, M. M. (2022). A comprehensive review on experimental, numerical and optimization analysis of EAHE and GSHP systems. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(45), 67559-67603.

- Liu, Z. , Sun, P., Li, S., Yu, Z. J., El Mankibi, M., Roccamena, L.,... & Zhang, G. (2019). Enhancing a vertical earth-to-air heat exchanger system using tubular phase change material. Journal of Cleaner Production, 237, 117763.

- Ahmed, S. F. , Khan, M. M. K., Amanullah, M. T. O., Rasul, M. G., & Hassan, N. M. S. (2015). Performance assessment of earth pipe cooling system for low energy buildings in a subtropical climate. Energy conversion and management, 106, 815-825.

- Maytorena, V. M., Moreno, S., & Hinojosa, J. F. (2021). Effect of operation modes on the thermal performance of EAHE systems with and without PCM in summer weather conditions. Energy and Buildings, 250, 111278.

- Niu, F., Yu, Y., Yu, D., & Li, H. (2015). Investigation on soil thermal saturation and recovery of an earth to air heat exchanger under different operation strategies. Applied Thermal Engineering, 77, 90-100.

- Sakhri, N. , Menni, Y., & Ameur, H. (2020). Effect of the pipe material and burying depth on the thermal efficiency of earth-to-air heat exchangers. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, 2, 100013.

- Lekhal, M. C. , Benzaama, M. H., Kindinis, A., Mokhtari, A. M., & Belarbi, R. (2021). Effect of geo-climatic conditions and pipe material on heating performance of earth-air heat exchangers. Renewable Energy, 163, 22-40.

- Xiao, J. , & Li, J. (2024). Influence of different types of pipes on the heat exchange performance of an earth-air heat exchanger. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 55, 104116.

- Peretti, C. , Zarrella, A., De Carli, M., & Zecchin, R. (2013). The design and environmental evaluation of earth-to-air heat exchangers (EAHE). A literature review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 28, 107-116.

- Pavlenko, A. M. Pavlenko, A. M., Usenko, B. O., & Koshlak, H. V. (2014). Analysis of thermal peculiarities of alloying with special properties. Metallurgical and Mining Industry, 2, 15-20.

- Agrawal, K. K. , Misra, R., & Agrawal, G. D. (2020). Improving the thermal performance of ground air heat exchanger system using sand-bentonite (in dry and wet condition) as backfilling material. Renewable Energy, 146, 2008-2023.

- Besler, M. , Cepiński, W., & Kęskiewicz, P. (2021). Direct-contact air, gravel, ground heat exchanger in air treatment systems for cowshed air conditioning. Energies, 15(1), 234.

- Liu, Z. , Sun, P., Xie, M., Zhou, Y., He, Y., Zhang, G.,... & Qin, D. (2021). Multivariant optimization and sensitivity analysis of an experimental vertical earth-to-air heat exchanger system integrating phase change material with Taguchi method. Renewable Energy, 173, 401-414.

- Zhou, T. , Xiao, Y., Huang, H., & Lin, J. (2020). Numerical study on the cooling performance of a novel passive system: Cylindrical phase change material-assisted earth-air heat exchanger. Journal of Cleaner Production, 245, 118907.

- Shahsavar, A. , & Azimi, N. (2024). Performance evaluation and multi-objective optimization of a hybrid earth-air heat exchanger and building-integrated photovoltaic/thermal system with phase change material and exhaust air heat recovery. Journal of Building Engineering, 90, 109531.

- Myroniuk, K., Furdas, Y., Zhelykh, V., Adamski, M., Gumen, O., Savin, V., & Mitoulis, S. A. (2024). Passive Ventilation of Residential Buildings Using the Trombe Wall. Buildings, 14(10), 3154.

- Cavazzini, G. , Zanetti, G., & Benato, A. (2024). Analysis of a domestic air heat pump integrated with an air-geothermal heat exchanger in real operating conditions: The case study of a single-family building. Energy and Buildings, 315, 114302.

- Baglivo, C., Bonuso, S., & Congedo, P. M. (2018). Performance Analysis of Air Cooled Heat Pump Coupled with Horizontal Air Ground Heat Exchanger in the Mediterranean Climate. Energies, 11(10), 2704.

- Lapertot, A. , Cuny, M., Kadoch, B., & Le Métayer, O. (2021). Optimization of an earth-air heat exchanger combined with a heat recovery ventilation for residential building needs. Energy and Buildings, 235, 110702.

- Li, H. , Ni, L., Yao, Y., & Sun, C. (2020). Annual performance experiments of an earth-air heat exchanger fresh air-handling unit in severe cold regions: Operation, economic and greenhouse gas emission analyses. Renewable energy, 146, 25-37.

- Ascione, F. , D'Agostino, D., Marino, C., & Minichiello, F. (2016). Earth-to-air heat exchanger for NZEB in Mediterranean climate. Renewable Energy, 99, 553-563.

- Thiers, S. , & Peuportier, B. (2008). Thermal and environmental assessment of a passive building equipped with an earth-to-air heat exchanger in France. Solar Energy, 82(9), 820-831.

- Wojtkowiak, J. (2012). Experimental flow characteristics of multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers. Foundations of Civil and Environmental Engineering, (15), 5-18.

- Bojic, M. , Trifunovic, N., Papadakis, G., & Kyritsis, S. (1997). Numerical simulation, technical and economic evaluation of air-to-earth heat exchanger coupled to a building. Energy, 22(12), 1151-1158.

- Li, H. , Ni, L., Liu, G., Zhao, Z., & Yao, Y. (2019). Feasibility study on applications of an Earth-air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) for preheating fresh air in severe cold regions. Renewable Energy, 133, 1268-1284.

- Lattieff, F. A. , Atiya, M. A., Lateef, R. A., Dulaimi, A., Jweeg, M. J., Abed, A. M.,... & Talebizadehsardari, P. (2022). Thermal analysis of horizontal earth-air heat exchangers in a subtropical climate: An experimental study. Frontiers in Built Environment, 8, 981946.

- Molina-Rodea, R. , Wong-Loya, J. A., Pocasangre-Chávez, H., & Reyna-Guillén, J. (2024). Experimental evaluation of a “U” type earth-to-air heat exchanger planned for narrow installation space in warm climatic conditions. Energy and Built Environment, 5(5), 772-786.

- Ahmed, S. F. , Liu, G., Mofijur, M., Azad, A. K., Hazrat, M. A., & Chu, Y. M. (2021). Physical and hybrid modelling techniques for earth-air heat exchangers in reducing building energy consumption: Performance, applications, progress, and challenges. Solar Energy, 216, 274-294.

- Tasdelen, F. , & Dagtekin, I. (2022). A numerical study on heating performance of horizontal and vertical earth-air heat exchangers with equal pipe lengths. Thermal Science, 26(4 Part A), 2929-2939.

- Salhein, K., Kobus, C. J., Zohdy, M., Annekaa, A. M., Alhawsawi, E. Y., & Salheen, S. A. (2024). Heat Transfer Performance Factors in a Vertical Ground Heat Exchanger for a Geothermal Heat Pump System. Energies, 17(19), 5003.

- Liu, Z. , Yu, Z. J., Yang, T., Li, S., El Mankibi, M., Roccamena, L.,... & Zhang, G. (2019). Experimental investigation of a vertical earth-to-air heat exchanger system. Energy Conversion and Management, 183, 241-251.

- Koshlak, H.; Pavlenko, A. Heat and Mass Transfer During Phase Transitions in Liquid Mixtures. Rocz. Ochr. Srodowiska 2019, 21, 234–249. [Google Scholar]

- Basok, B.; Davydenko, B.; Koshlak, H.; Novikov, V. Free Convection and Heat Transfer in Porous Ground Massif during Ground Heat Exchanger Operation. Materials 2022, 15, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, G. H., Lee, S. R., Nikhil, N. V., & Yoon, S. (2015). A new performance evaluation algorithm for horizontal GCHPs (ground coupled heat pump systems) that considers rainfall infiltration. Energy, 83, 766-777.

- Rodríguez-Vázquez, M. , Xamán, J., Chávez, Y., Hernández-Pérez, I., & Simá, E. (2020). Thermal potential of a geothermal earth-to-air heat exchanger in six climatic conditions of México. Mechanics & Industry, 21(3), 308.

- Bisoniya, T. S. (2015). Design of earth–air heat exchanger system. Geothermal Energy, 3, 1-10.

- Basok, B. , Pavlenko, A., Nedbailo, A., Bozhko, I., Novitska, M., Koshlak, H., & Tkachenko, M. (2022). Analysis of the Energy Efficiency of the Earth-To-Air Heat Exchanger. Rocznik Ochrona Środowiska, 24, 202-213.

- Greco, A. , Gundabattini, E., Solomon, D. G., Singh Rassiah, R., & Masselli, C. (2022). A Review on Geothermal Renewable Energy Systems for Eco-Friendly Air-Conditioning. Energies, 15(15), 5519.

- Peñaloza Peña, S. A., & Jaramillo Ibarra, J. E. (2021). Potential applicability of earth to air heat exchanger for cooling in a colombian tropical weather. Buildings, 11(6), 219.

- Malek, K., Malek, K., & Khanmohammadi, F. (2021). Response of soil thermal conductivity to various soil properties. International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer, 127, 105516.

- Agrawal, K. K. , Yadav, T., Misra, R., & Agrawal, G. D. (2019). Effect of soil moisture contents on thermal performance of earth-air-pipe heat exchanger for winter heating in arid climate: In situ measurement. Geothermics, 77, 12-23.

- Di Sipio, E., & Bertermann, D. (2017). Factors influencing the thermal efficiency of horizontal ground heat exchangers. Energies, 10(11), 1897.

- Kumar Singh, R., & Sharma, R. V. (2017). Mathematical Investigation of Soil Temperature Variation for Geothermal Applications. International Journal of Engineering, 30(10), 1609-1614.

- Faridi, H. , Arabhosseini, A., Zarei, G., & Okos, M. (2021). Degree-Day Index for Estimating the Thermal Requirements of a Greenhouse Equipped with an Air-Earth Heat Exchanger System. Journal of Agricultural Machinery, 11(1), 83-95.

- Ascione, F. , Bellia, L., & Minichiello, F. (2011). Earth-to-air heat exchangers for Italian climates. Renewable energy, 36(8), 2177-2188.

- Vidhi, R. (2018). A review of underground soil and night sky as passive heat sink: Design configurations and models. Energies, 11(11), 2941.

- Singh, R. K., & Sharma, R. V. (2017). Numerical analysis for ground temperature variation. Geothermal Energy, 5, 1-10.

- Kaushal, M. (2017). Geothermal cooling/heating using ground heat exchanger for various experimental and analytical studies: Comprehensive review. Energy and Buildings, 139, 634-652.

- Sanusi, A. N., Shao, L., & Ibrahim, N. (2013). Passive ground cooling system for low energy buildings in Malaysia (hot and humid climates). Renewable energy, 49, 193-196.

- Babar, H. , Ali, H. M., Haseeb, M., Abubaker, M., Muhammad, A., & Irfan, July). Experimental investigation of the ground coupled heat exchanger system under the climatic conditions of Sahiwal, Pakistan. In Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, London, UK (pp. 4-6)., M. (2018. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, T. A. , Shabbir, K., Khan, M. M., Siddiqui, F. A., Taseer, M. Y. R., & Imtiaz, S. (2020). Earth-tube system to control indoor thermal environment in residential buildings. Technical Journal, 25(02), 33-40.

- Alves, A. B. M., & Schmid, A. L. (2015). Cooling and heating potential of underground soil according to depth and soil surface treatment in the Brazilian climatic regions. Energy and Buildings, 90, 41-50.

- Bhandari, R. (2024). Sustainable cooling solutions for building environments: A comprehensive study of earth-air cooling systems. Advances in Mechanical Engineering, 16(9), 16878132241272209.

- Pollack, H. N. , Smerdon, J. E., & van Keken, P. E. (2005). Variable seasonal coupling between air and ground temperatures: A simple representation in terms of subsurface thermal diffusivity. Geophysical Research Letters, 32(15).

- Smerdon, J. E. , Pollack, H. N., Cermak, V., Enz, J. W., Kresl, M., Safanda, J., & Wehmiller, J. F. (2004). Air-ground temperature coupling and subsurface propagation of annual temperature signals. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 109(D21).

- Kane, D. L. , Hinkel, K. M., Goering, D. J., Hinzman, L. D., & Outcalt, S. I. (2001). Non-conductive heat transfer associated with frozen soils. Global and Planetary Change, 29(3-4), 275-292.

- Zajch, A. , & Gough, W. A. (2021). Seasonal sensitivity to atmospheric and ground surface temperature changes of an open earth-air heat exchanger in Canadian climates. Geothermics, 89, 101914.

- Zajch, A. , W., & Chiesa, G. (2020). Earth–Air Heat Exchanger Potential Under Future Climate Change Scenarios in Nine North American Cities. In Sustainability in Energy and Buildings: Proceedings of SEB 2019 (pp.

- Singh, B. , Kumar, R., & Asati, A. K. (2018). Influence of parameters on performance of earth air heat exchanger in hot-dry climate. Journal of Mechanical Science and Technology, 32, 5457-5463.

- Liu, Z. , Yu, Z. J., Yang, T., Roccamena, L., Sun, P., Li, S.,... & El Mankibi, M. (2019). Numerical modeling and parametric study of a vertical earth-to-air heat exchanger system. Energy, 172, 220-231.

- Hasan, M. I. , Noori, S. W., & Shkarah, A. J. (2019). Parametric study on the performance of the earth-to-air heat exchanger for cooling and heating applications. Heat Transfer—Asian Research, 48(5), 1805-1829.

- Ali, S., Muhammad, N., Amin, A., Sohaib, M., Basit, A., & Ahmad, T. (2019). Parametric optimization of earth to air heat exchanger using response surface method. Sustainability, 11(11), 3186.

- Agrawal, K. K. , Misra, R., & Agrawal, G. D. (2020). To study the effect of different parameters on the thermal performance of ground-air heat exchanger system: In situ measurement. Renewable Energy, 146, 2070-2083.

- Mahach, H. , & Benhamou, B. (2021). Extensive parametric study of cooling performance of an earth-to-air heat exchanger in hot semi-arid climate. Journal of Thermal Science and Engineering Applications, 13(3), 031006.

- Zhang, Z. , Sun, J., Zhang, Z., Jia, X., & Liu, Y. (2021). Numerical Research and Parametric Study on the Thermal Performance of a Vertical Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger System. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2021(1), 5557280.

- Yu, W. , Chen, X., Ma, Q., Gao, W., & Wei, X. (2022). Modeling and assessing earth-air heat exchanger using the parametric performance design method. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects, 44(3), 7873-7894.

- Sghiouri, H. , Wakil, M., Charai, M., & Mezrhab, A. (2024). Development of a Multi-Objective optimization framework for Earth-to-Air heat Exchanger Systems: Enhancing thermal performance and economic viability in Moroccan climates. Energy Conversion and Management, 321, 119024.

- de Andrade, I. R. , dos Santos, E. D., Zhang, H., Rocha, L. A. O., Razera, A. L., & Isoldi, L. A. (2024). Multi-Objective Numerical Analysis of Horizontal Rectilinear Earth–Air Heat Exchangers with Elliptical Cross Section Using Constructal Design and TOPSIS. Fluids, 9(11), 257.

- Wei, H. , & Yang, D. (2019). Performance evaluation of flat rectangular earth-to-air heat exchangers in harmonically fluctuating thermal environments. Applied Thermal Engineering, 162, 114262.

- Jahanbin, A. (2020). Thermal performance of the vertical ground heat exchanger with a novel elliptical single U-tube. Geothermics, 86, 101804.

- Benhammou, M. , Sahli, Y., & Moungar, H. (2022). Investigation of the impact of pipe geometric form on earth-to-air heat exchanger performance using Complex Finite Fourier Transform analysis. Part I: Operation in cooling mode. International Journal of Thermal Sciences, 177, 107484.

- Darius, D. , Misaran, M. S., Rahman, M. M., Ismail, M. A., & Amaludin, A. (2017, July). Working parameters affecting earth-air heat exchanger (EAHE) system performance for passive cooling: A review. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 217, No. 1, p. 012021). IOP Publishing.

- Benrachi, N. , Ouzzane, M., Smaili, A., Lamarche, L., Badache, M., & Maref, W. (2020). Numerical parametric study of a new earth-air heat exchanger configuration designed for hot and arid climates. International Journal of Green Energy, 17(2), 115-126.

- Mihalakakou, G. , Lewis, J. O., & Santamouris, M. (1996). On the heating potential of buried pipes techniques—application in Ireland. Energy and Buildings, 24(1), 19-25.

- Amanowicz, Ł. , & Wojtkowiak, J. (2021). Comparison of single-and multipipe earth-to-air heat exchangers in terms of energy gains and electricity consumption: A case study for the temperate climate of central europe. Energies, 14(24), 8217.

- Mihalakakou, G. , Souliotis, M., Papadaki, M., Halkos, G., Paravantis, J., Makridis, S., & Papaefthimiou, S. (2022). Applications of earth-to-air heat exchangers: a holistic review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 155, 111921.

- Qi, D. , Li, S., Zhao, C., Xie, W., & Li, A. (2022). Structural optimization of multi-pipe earth to air heat exchanger in greenhouse. Geothermics, 98, 102288.

- Amanowicz, Ł. , & Wojtkowiak, J. (2020). Thermal performance of multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers considering the non-uniform distribution of air between parallel pipes. Geothermics, 88, 101896.

- Minaei, A. , & Rabani, R. (2023). Development of a transient analytical method for multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers with parallel configuration. Journal of Building Engineering, 73, 106781.

- Qi, D., Li, A., Li, S., & Zhao, C. (2021). Comparative analysis of earth to air heat exchanger configurations based on uniformity and thermal performance. Applied Thermal Engineering, 183, 116152.

- Brum, R. S. , Ramalho, J. V., Rodrigues, M. K., Rocha, L. A., Isoldi, L. A., & Dos Santos, E. D. (2019). Design evaluation of Earth-Air Heat Exchangers with multiple ducts. Renewable Energy, 135, 1371-1385.

- Amanowicz, Ł. , & Wojtkowiak, J. (2020). Approximated flow characteristics of multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers for thermal analysis under variable airflow conditions. Renewable Energy, 158, 585-597.

- Amanowicz, Ł. (2018). Influence of geometrical parameters on the flow characteristics of multi-pipe earth-to-air heat exchangers–experimental and CFD investigations. Applied energy, 226, 849-861.

- Badescu, V. , & Isvoranu, D. (2011). Pneumatic and thermal design procedure and analysis of earth-to-air heat exchangers of registry type. Applied Energy, 88(4), 1266-1280.

- Sofyan, S. E. , Riayatsyah, T. M. I., Hu, E., Tamlicha, A., Pahlefi, T. M. R., & Aditiya, H. B. (2024). Computational fluid dynamic simulation of earth air heat exchanger: A thermal performance comparison between series and parallel arrangements. Results in Engineering, 24, 102932.

- Muehleisen, R. T. (2012). Simple design tools for earth-air heat exchangers. Proceedings of SimBuild, 5(1), 723-730.

- Mehdid, C. E. , Benchabane, A., Rouag, A., Moummi, N., Melhegueg, M. A., Moummi, A.,... & Brima, A. (2018). Thermal design of Earth-to-air heat exchanger. Part II a new transient semi-analytical model and experimental validation for estimating air temperature. Journal of cleaner production, 198, 1536-1544.

- Ali, M. H. , Kurjak, Z., & Beke, J. (2023). Investigation of earth air heat exchangers functioning in arid locations using Matlab/Simulink. Renewable Energy, 209, 632-643.

- Congedo, P. M. , Baglivo, C., Bonuso, S., & D’Agostino, D. (2020). Numerical and experimental analysis of the energy performance of an air-source heat pump (ASHP) coupled with a horizontal earth-to-air heat exchanger (EAHX) in different climates. Geothermics, 87, 101845.

- Guo, X. , Wei, H., He, X., Du, J., & Yang, D. (2022). Experimental evaluation of an earth–to–air heat exchanger and air source heat pump hybrid indoor air conditioning system. Energy and Buildings, 256, 111752.

- Do, S. L. , Baltazar, J. C., & Haberl, J. (2015). Potential cooling savings from a ground-coupled return-air duct system for residential buildings in hot and humid climates. Energy and Buildings, 103, 206-215.

- Mahmoud, M. , Abdelkareem, M. A., & Olabi, A. G. (2024). Earth air heat exchangers. In Renewable Energy-Volume 2: Wave, Geothermal, and Bioenergy (pp. 163-179). Academic Press.

- Yan, T. , & Xu, X. (2018). Utilization of ground heat exchangers: a review. Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports, 5, 189-198.

- Qi, X. , Yang, D., Guo, X., Chen, F., An, F., & Wei, H. (2024). Theoretical modelling and experimental evaluation of thermal performance of a combined earth-to-air heat exchanger and return air hybrid system. Renewable Energy, 236, 121418.

- Kundu, A. (2025). Application of Geothermal Energy-Based Earth-Air Heat Exchanger in Sustainable Buildings. Heat Transfer Enhancement Techniques: Thermal Performance, Optimization and Applications, 221-232.

- Dokmak, H. , Faraj, K., Faraj, J., Castelain, C., & Khaled, M. (2024). Geothermal systems classification, coupling, and hybridization: A recent comprehensive review. Energy and Built Environment.

- Yadav, S. , Panda, S. K., Tiwari, G. N., Al-Helal, I. M., & Hachem-Vermette, C. (2022). Periodic theory of greenhouse integrated semi-transparent photovoltaic thermal (GiSPVT) system integrated with earth air heat exchanger (EAHE). Renewable Energy, 184, 45-55.

- Hraibet, M. K. , Ismaeel, A. A., & Mohammed, M. J. (2024, June). Performances evaluation of different photovoltaic-thermal solar collector designs for electrical and hot air generation technology. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 3002, No. 1). AIP Publishing.

- Zhao, J. , Huang, B., Li, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2024). Comprehensive review on climatic feasibility and economic benefits of Earth-to-Air Heat Exchanger (EAHE) systems. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 68, 103862.

- Gorjian, S. , Singh, R., Shukla, A., & Mazhar, A. R. (2020). On-farm applications of solar PV systems. In Photovoltaic solar energy conversion (pp. 147-190). Academic Press.

- Aljashaami, B. A. , Ali, B. M., Salih, S. A., Alwan, N. T., Majeed, M. H., Ali, O. M.,... & Shcheklein, S. E. (2024). Recent improvements to heating, ventilation, and cooling technologies for buildings based on renewable energy to achieve zero-energy buildings: A systematic review. Results in Engineering, 102769.

- Hepbasli, A. (2013). Low exergy modelling and performance analysis of greenhouses coupled to closed earth-to-air heat exchangers (EAHEs). Energy and Buildings, 64, 224-230.

- Shaaban, A. , Mosa, M., El Samahy, A., & Abed, K. (2023). Enhancing the Performance of Photovoltaic Panels by Cooling: a Review. International Review of Automatic Control, 16(1), 26-43.

- Dhaidan, N. S. , Al-Shohani, W. A., Abbas, H. H., Rashid, F. L., Ameen, A., Al-Mousawi, F. N., & Homod, R. Z. (2024). Enhancing the thermal performance of an agricultural solar greenhouse by geothermal energy using an earth-air heat exchanger system: A review. Geothermics, 123, 103115.

- Jakhar, S. , Soni, M. S., & Boehm, R. F. (2018). Thermal modeling of a rooftop photovoltaic/thermal system with earth air heat exchanger for combined power and space heating. Journal of Solar Energy Engineering, 140(3), 031011.

- Lopez-Pascual, D. , Valiente-Blanco, I., Manzano-Narro, O., Fernandez-Munoz, M., & Diez-Jimenez, E. (2022). Experimental characterization of a geothermal cooling system for enhancement of the efficiency of solar photovoltaic panels. Energy Reports, 8, 756-763.

- Tiwari, G. N. , Singh, S., Singh, Y., Tiwari, A., & Panda, S. K. (2022). Enhancement of daily and monthly electrical power of off-grid greenhouse integrated semi-transparent photo-voltaic thermal (GiSPVT) system by integrating earth air heat exchanger (EAHE). e-Prime-Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy, 2, 100074.

- Salem, H. H. , & Hashem, A. L. (2023, July). Integration of Earth-air heat exchanger in buildings review for theoretical researches. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 2787, No. 1). AIP Publishing.

- Yildiz, A., Ozgener, O., & Ozgener, L. (2011). Exergetic performance assessment of solar photovoltaic cell (PV) assisted earth to air heat exchanger (EAHE) system for solar greenhouse cooling. Energy and Buildings, 43(11), 3154-3160.

- Alkaragoly, M. , Maerefat, M., Targhi, M. Z., & Abdljalel, A. (2022). An innovative hybrid system consists of a photovoltaic solar chimney and an earth-air heat exchanger for thermal comfort in buildings. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering, 40, 102546.

- Li, Y., Chu, S., Zhao, J., Li, W., Tan, B., & Lu, J. (2024). A numerical study on the performance of a hybrid ventilation and power generation system. Applied Thermal Engineering, 238, 122228.

- Yang, L. H. , Hu, J. W., Chiang, Y. C., & Chen, S. L. (2021). Performance analysis of building-integrated earth-air heat exchanger retrofitted with a supplementary water system for cooling-dominated climate in Taiwan. Energy and Buildings, 242, 110949.

- Ahmadi, S. , Irandoost Shahrestani, M., Sayadian, S., Maerefat, M., & Haghighi Poshtiri, A. (2021). Performance analysis of an integrated cooling system consisted of earth-to-air heat exchanger (EAHE) and water spray channel. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 143, 473-483.

- Radchenko, M. , Yang, Z., Pavlenko, A., Radchenko, A., Radchenko, R., Koshlak, H., & Bao, G. (2023). Increasing the efficiency of turbine inlet air cooling in climatic conditions of China through rational designing—Part 1: A case study for subtropical climate: general approaches and criteria. Energies, 16(17), 6105.

- Liu, T. , Pang, H., He, S., Zhao, B., Zhang, Z., Wang, J.,... & Gao, M. (2023). Evaporative Cooling Applied in Thermal Power Plants: A Review of the State-of-the-Art and Typical Case Studies. Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing, 19(9).

- Barakat, S., Ramzy, A., Hamed, A. M., & El-Emam, S. H. (2019). Augmentation of gas turbine performance using integrated EAHE and Fogging Inlet Air Cooling System. Energy, 189, 116133.

- de la Rocha Camba, E. , & Petrakopoulou, F. (2020). Earth-cooling air tunnels for thermal power plants: Initial design by CFD modelling. Energies, 13(4), 797.

- Shahsavar, A. , & Arıcı, M. (2023). Multi-objective energy and exergy optimization of hybrid building-integrated heat pipe photovoltaic/thermal and earth air heat exchanger system using soft computing technique. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, 148, 293-304.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).