I. Introduction

Natural Cordyceps sinensis is one of most valued and expensive therapeutic agents in traditional Chinese medicine and has a rich history of clinical use for several centuries in health maintenance, disease amelioration, postdisease and postsurgery recovery and antiaging therapy [Zhu et al. 1998a, 1998b, 2011]. As defined by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, natural C. sinensis is an insect-fungal complex containing the Ophiocordyceps sinensis fruiting body and the remains of a Hepialidae moth larva (an intact, thick larval body wall with numerous bristles, intact larval intestine and head tissues, and fragments of other larval tissues) [Ren et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2016; Zhu & Li 2017; Li et al. 2022]. Studies of natural C. sinensis have demonstrated its multicellular heterokaryotic structures and genetic heterogeneity, including at least 17 genomically independent genotypes of O. sinensis fungi, >90 other fungal species spanning at least 37 fungal genera and larval genes [Jiang & Yao 2003; Zhang et al. 2010, 2018; Xia et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2017; Zhu & Li 2017; Li et al. 2016b, 2020, 2022, 2023c; Zhong et al. 2018; Kang et al. 2024]. Among the numerous heterogeneous fungal species, Hirsutella sinensis has been postulated to be the sole-anamorph of O. sinensis by Wei et al. [2006]; however, 10 years later, the key authors reported a species contradiction in an artificial cultivation project conducted in a product-oriented industrial setting between anamorphic inoculates of 3 GC-biased H. sinensis strains on Hepialidae moth larvae and the sole AT-biased teleomorph (Genotype #4 of O. sinensis) in cultivated C. sinensis [Wei et al. 2016]. Notably, the Latin name Cordyceps sinensis has been used indiscriminately since the 1840s for both the teleomorph/holomorph of the fungus C. sinensis and the wild insect-fungal complex, and the fungus was renamed Ophiocordyceps sinensis in 2007 [Sung et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2012; Ren et al. 2013; Zhu & Yao 2014; Zhu & Li 2017; Li et al. 2022]. Although mycologists Zhang et al. [2013] proposed improper implementation of the “One Fungus=One Name” nomenclature rule of the International Mycological Association [Hawksworth et al. 2011] while disregarding the presence of multiple genomically independent genotypes of O. sinensis fungi and inappropriately replacing the anamorphic name H. sinensis with the teleomorphic name O. sinensis, we continue using the anamorphic name H. sinensis for Genotype #1 of the 17 O. sinensis genotypes in this paper and refer to the genomically independent Genotypes #2‒17 fungi as O. sinensis before their systematic positions are determined, regardless of whether they are GC- or AT-biased genetically. We continue the customary use of the name C. sinensis to refer to the wild or cultivated insect-fungal complex because the renaming of C. sinensis to O. sinensis in 2007 did not involve the indiscriminate use of the Latin name for the natural insect-fungi complex, although this practice will likely be replaced in the future by the differential use of proprietary and exclusive Latin names for the multiple genome-independent O. sinensis genotypic fungi and the insect-fungi complex.

The sexual reproductive behavior of ascomycetes is controlled by transcription factors encoded at the mating-type (MAT) locus [Debuchy et al. 2006; Jones & Bennett 2011; Zheng & Wang 2013; Wilson et al. 2015]. Holliday et al. [2008], Stone et al. [2010], and Hu et al. [2013] reported the failures to induce the development of C. sinensis fruiting bodies and ascospores via the use of pure H. sinensis cultures as inoculants. Zhang et al. [2013] summarized the failures over 40 years of academic experience in research-oriented academic settings. Hu et al. [2013] and Bushley et al. [2013] hypothesized that H. sinensis undergoes self-fertilization under homothallism or pseudohomothallism; however, Zhang et al. [2009, 2011] and Zhang and Zhang [2015] reported differential occurrence of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes in numerous wild-type C. sinensis isolates and hypothesized that O. sinensis underwent facultative hybridization. Moreover, Li et al. [2023a, 2024] reported alternative splicing, differential occurrence and differential transcription of mating-type and pheromone receptor genes in H. sinensis and natural C. sinensis, suggesting the occurrence of self-sterility in H. sinensis under heterothallism or hybridization and the requirement of sexual partners during the sexual life of natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complex.

Sequences of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes and proteins of H. sinensis are available in the GenBank database, but little is known about the polymorphic stereostructures of the proteins in H. sinensis strains and C. sinensis isolates, which are extremely crucial to the sexual reproduction of O. sinensis and to maintain the natural population volume of the Level II endangered authentic traditional Chinese medicinal “herb”, which is a natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complex. In this work, we analyzed the clustering of the AlphaFold-predicted 3D structural morphs of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins from 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates and correlated the heteromorphic structural morphs with the protein sequences translated from the genome, transcriptome and metatranscriptome assemblies of H. sinensis and natural C. sinensis.

II. Materials and Methods

II-1. C. sinensis Isolates and Accession Numbers of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Proteins

The AlphaFold database lists the accession numbers of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins and the 3D protein structures, which were derived from 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates that were collected from various production areas on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau [Zhang et al. 2009, 2011; Hu et al. 2013; Zhang & Zhang 2015; Tunyasuvunakool et al. 2021].

II-3. Clustering Analysis for the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Protein Sequences

Multiple protein sequences of the H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates were analyzed via the auto mode of MAFFT (v7.427). Bayesian clustering trees of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 protein sequences were then inferred using MrBayes v3.2.7 software (Markov chain Monte Carlo [MCMC] algorithm) with a sampling frequency of 100 iterations after discarding the initial 25% of the samples from a total of 1 million iterations [Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001; Li et al. 2022, 2023b, 2024]. Clustering analysis was conducted at Nanjing Genepioneer Biotechnologies Co.

II-4. AlphaFold-Based Prediction of 3D Structures of Mating Proteins

The 3D structures of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins of the 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates were computationally predicted from their amino acid sequences using the artificial intelligence (AI)-based machine learning technology AlphaFold (

https://alphafold.com/) and downloaded from the AlphaFold database (accessed on 10/18/2024 to 12/31/2025) for structural polymorphism analysis in this study [Jumper et al. 2021; David et al. 2022; Abramson et al. 2024; Varadi et al. 2024]. The heteromorphic 3D structures of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins were grouped on the basis of the results of AlphaFold structural and Bayesian clustering analyses.

II-5. Alignment Analysis of Protein Sequences

The amino acid sequences of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins of H. sinensis and natural C. sinensis were aligned and compared using the GenBank Blastp program (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

II-6. Amino Acid Properties and Scale Analysis

The amino acid components of the mating proteins were scaled on the basis of the general chemical characteristics of their side chains (cf.

Table S1) and plotted sequentially with a window size of 21 amino acid residues for the α-helices, β-sheets, β-turns, and coils of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins using the linear weight variation model of the ExPASy ProtScale algorithm (

https://web.expasy.org/protscale/) [Deleage & Roux 1987; Gasteiger et al. 2005; Peters & Elofsson 2014; Simm et al. 2016; Li et al. 2024]. The plotting topologies and waveforms of the ProtScale plots for the proteins were compared to explore alterations in the 2D structures of the mating-type proteins.

III. Results

III-1. Diversity of MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Proteins in H. sinensis Strains and C. sinensis Isolates Based on the AlphaFold-Predicted 3D Structures

The AlphaFold database lists the accession numbers for 138 MAT1-1-1 proteins and 79 MAT1-2-1 proteins, which were derived from 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates [Zhang et al. 2009, 2011, 2013; Bushley et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2013; Zhang & Zhang 2015]. Among the strains/isolates, 42 (24.3%) had records of AlphaFold-predicted 3D structures for both the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins. A majority (75.7%) of the strains/isolates presented 3D structure records for either the MAT1-1-1 or MAT1-2-1 protein, suggesting differential co-occurrence of the 2 mating proteins essential for the sexual reproduction of O. sinensis.

Strain GS09_111 has 2 accession numbers for the MAT1-1-1 proteins, namely, ALH24945 and AGW27528; the sequences were released by GenBank on 28-SEP-2013 and shared 100% sequence identity. However, ALH24945 is a full-length protein containing 372 amino acids, whereas AGW27528 is an N- and C-terminally truncated protein containing 301 amino acids with 80.9% query coverage.

Strain CS2 has accession numbers for 2 MAT1-2-1 proteins, namely, AEH27625 and ACV60400, containing 249 amino acids and sharing 100% sequence identity; the sequences were released by GenBank 6 years apart on 03-JUN-2010 and 25-JUL-2016, respectively.

The 138 MAT1-1-1 protein sequences belong to the diverse 3D structural morphs under 24 UniProt codes in the AlphaFold database and are listed in

Table 1.

The 79 MAT1-2-1 proteins belong to the diverse 3D structural morphs under 21 UniProt codes in the AlphaFold database and are listed in

Table 2.

III-2. Bayesian Analysis of the Mating Proteins

A total of 118 of the 138 MAT1-1-1 protein sequences are full-length proteins belonging to the 3D structural morphs under 15 AlphaFold UniProt codes; 89 (75.4%) of the 118 full-length proteins are under the UniProt code U3N942 (cf.

Table 1). The remaining 20 MAT1-1-1 proteins are truncated and belong to 3D structural morphs under 9 other UniProt codes.

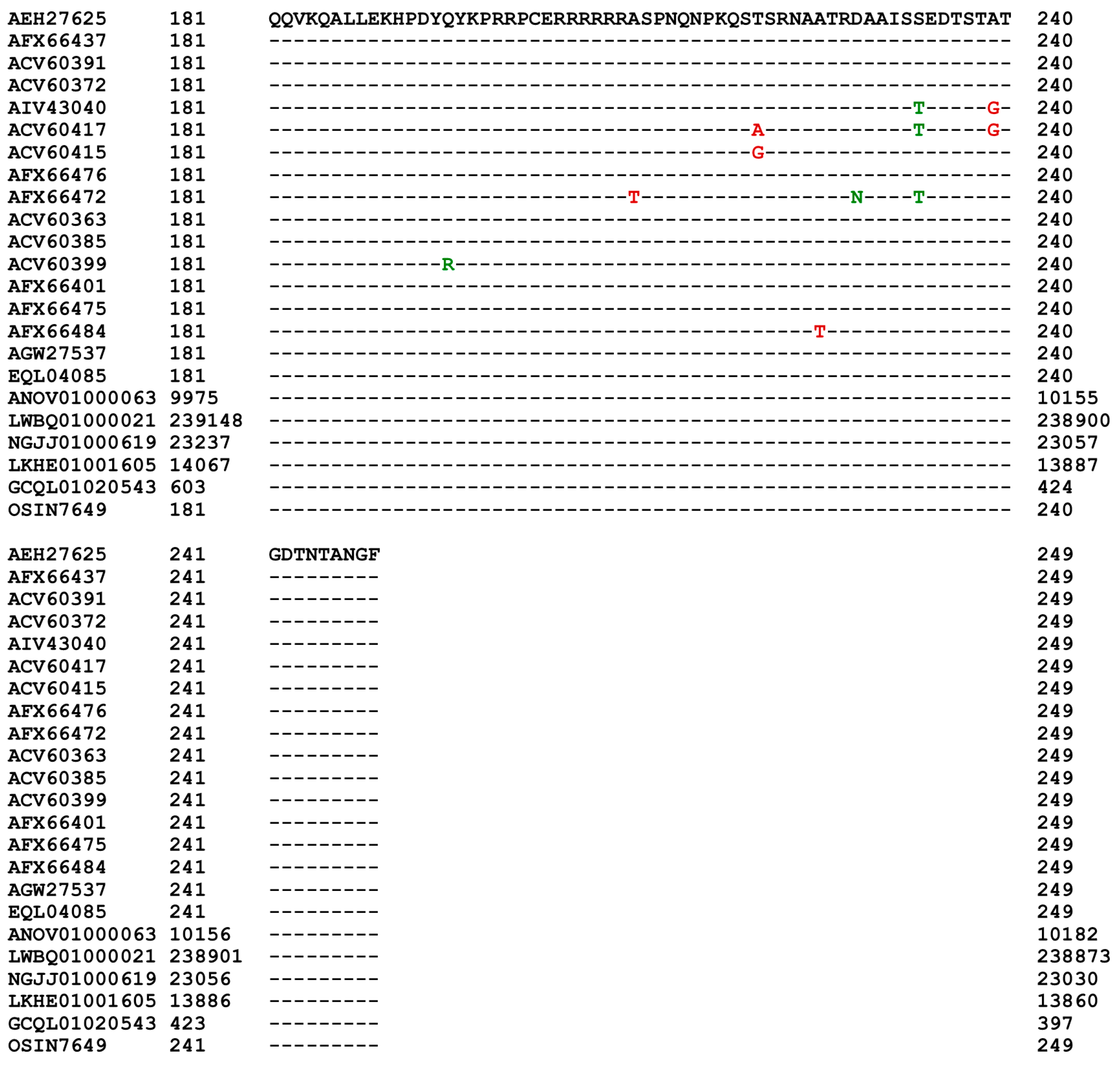

Figure 1 shows the Bayesian clustering tree for 40 protein sequences representing the diverse structural morphs of MAT1-1-1 proteins under 24 UniProt codes. The representative sequences ALH24945, ALH24947, and AGW27560 under UniProt code U3N942 were clustered into Branch A1 of Cluster A, as shown in red alongside the tree in

Figure 1. Branch A1 of

Figure 1 also includes the full-length proteins under UniProt codes A0A0N9QMM1 and T5A511, also shown in

Table 1. Cluster A includes other full-length MAT1-1-1 protein sequences with very similar 3D structures, which were clustered into Branch A2 in pink and Branch A3 in purple alongside the tree. The full-length MAT1-1-1 protein sequences with significantly variable 3D structures were clustered within Clusters B−E of

Figure 1, either branched or unbranched, under various UniProt codes in red for Branch 1, in pink for Branch 2, in purple for Branch 3, or in brown for Branch 4.

Many truncated proteins were found under UniProt codes U3N919, U3N6U0, U3N9T9, U3N7G5, U3N6U4, U3NE87, U3N6U8, and U3N7H7, shown in green alongside the tree in

Figure 1, and were clustered into Branches A1−A3 of Cluster A. In addition, Cluster F contains the truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins under the UniProt code U3NE79 in green alongside the tree in

Figure 1.

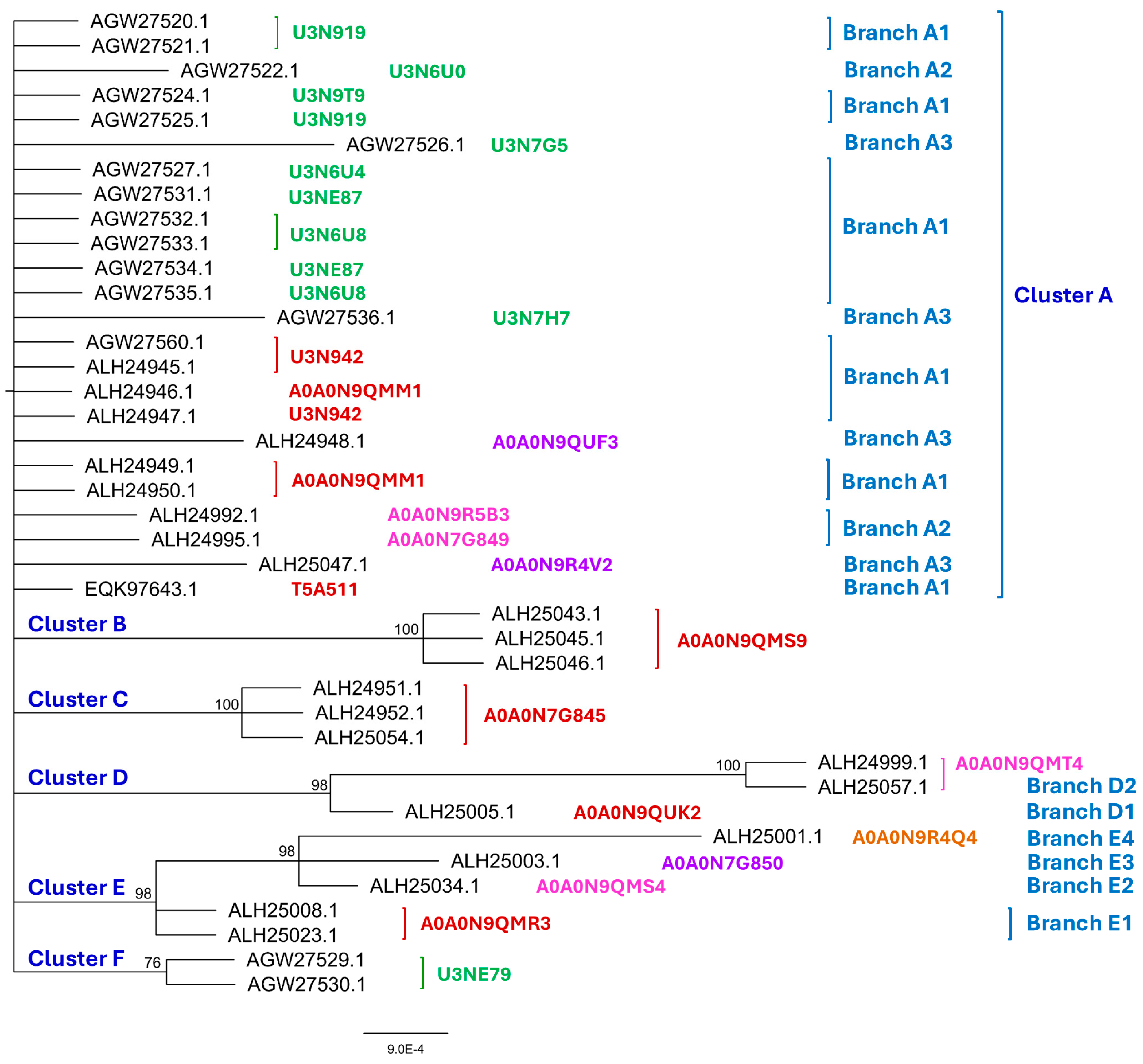

The 79 MAT1-2-1 proteins have various 3D structural morphs under 21 UniProt codes in the AlphaFold database (cf.

Table 2), 32 representative sequences of which were subjected to Bayesian clustering analysis, as shown in

Figure 2.

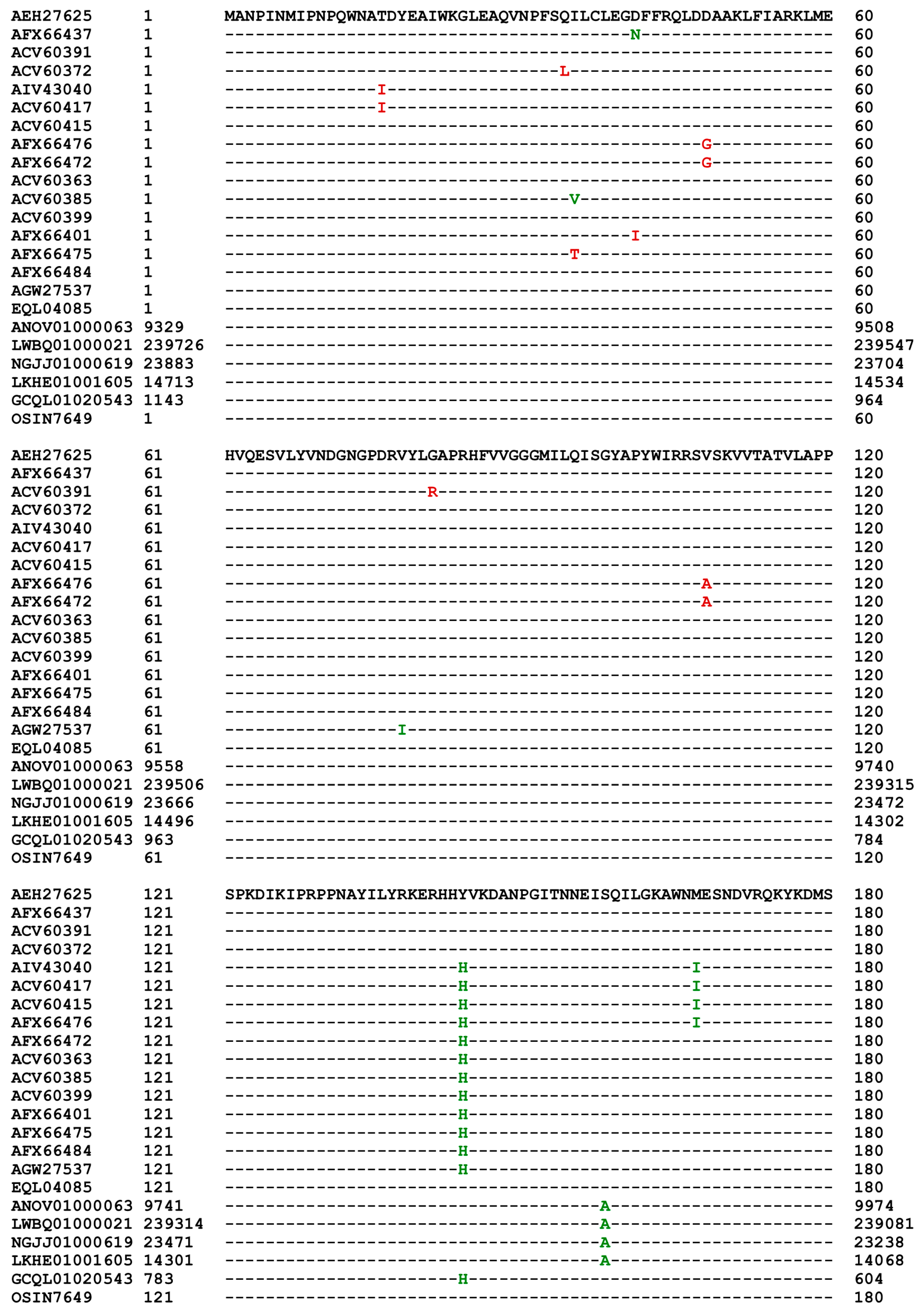

Seventy-four MAT1-2-1 proteins are full-length proteins, containing 249 amino acids belonging to the diverse 3D structural morphs under 17 AlphaFold UniProt codes. The remaining 5 MAT1-2-1 proteins are truncated and belong to 3D structural morphs under 4 other UniProt codes.

Among the 74 full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins, 38 (51.4%) are under the UniProt code D7F2E9 (cf.

Table 2), which were clustered into Branch I-1 of Cluster I of the Bayesian tree shown in

Figure 2. Branch I-1 also includes the full-length protein EQL04085 under the UniProt code T5AF56. Branch I-2 of Cluster I includes the MAT1-2-1 proteins with very similar 3D structures belonging to 3D structural morphs under the UniProt codes V9LW10, D7F2H1, and D7F2F2. Five other full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins with significantly variable 3D structures were within Clusters II−V, shown in

Figure 2 under various UniProt codes. Branches V-1 and V-2 of Cluster V also include the truncated proteins under different UniProt codes shown in green alongside the tree.

III-3. Heteromorphic AlphaFold-Predicted 3D Structures of the MAT1-1-1 Proteins

Figure 3 shows the AlphaFold-predicted 3D structures of the 118 full-length MAT1-1-1 proteins under 15 structural morphs, which are also listed in

Table 1. The sequence distributions and 3D structures of 20 N- and C-terminally truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins are shown in

Figure 4; these structures constitute the remaining 9 stereostructural morphs.

III-4. Heteromorphic AlphaFold-Predicted 3D Structures of the MAT1-2-1 Proteins

Among the 79 MAT1-2-1 protein sequences belonging to the 21 diverse 3D structural morphs, 74 are full-length proteins belonging to diverse structural morphs under 17 UniProt codes and are shown in

Figure 5.

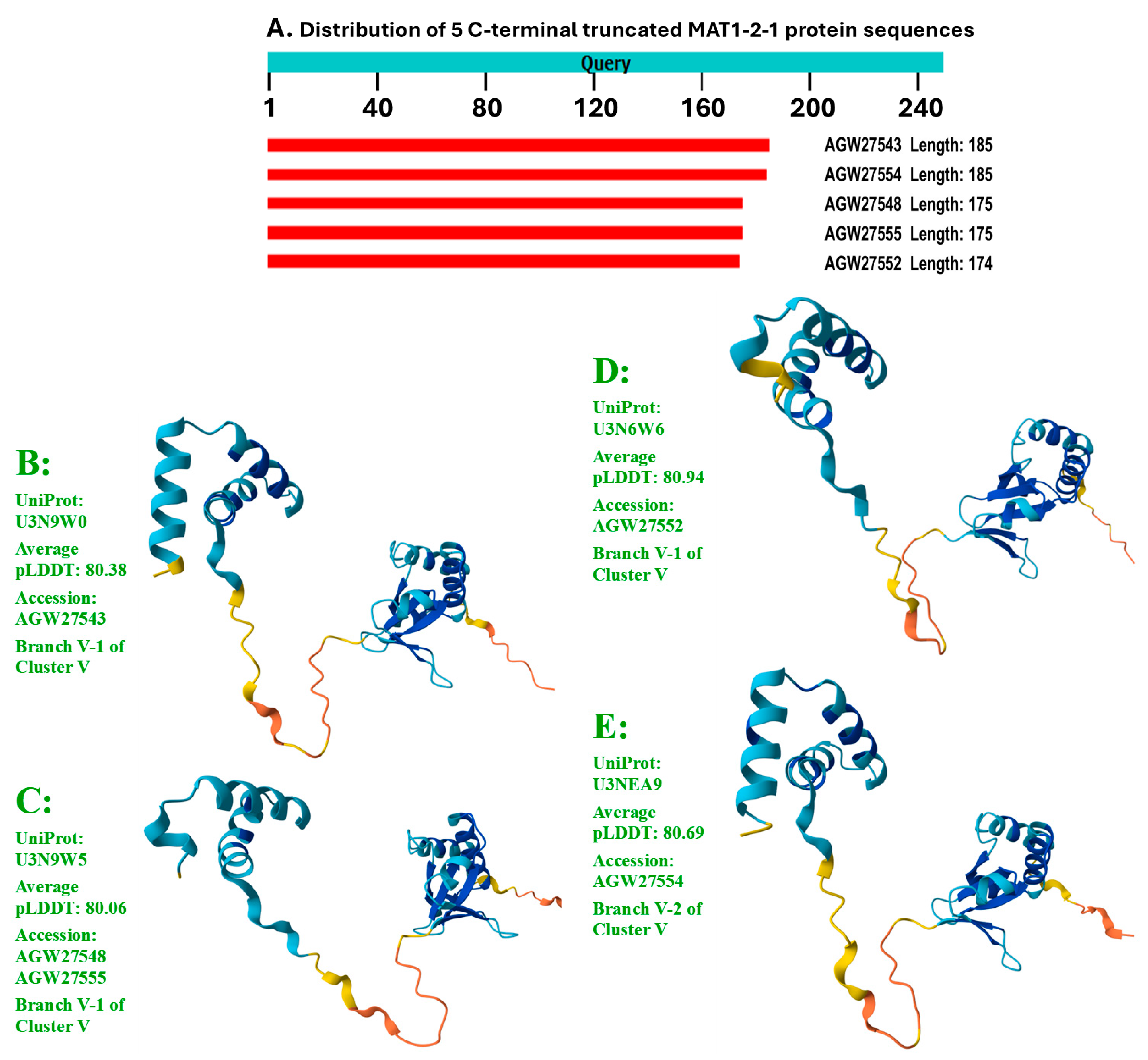

Figure 6 shows the sequence distribution and the AlphaFold-predicted 3D structures of the C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins, which constitute the remaining 4 stereostructural morphs.

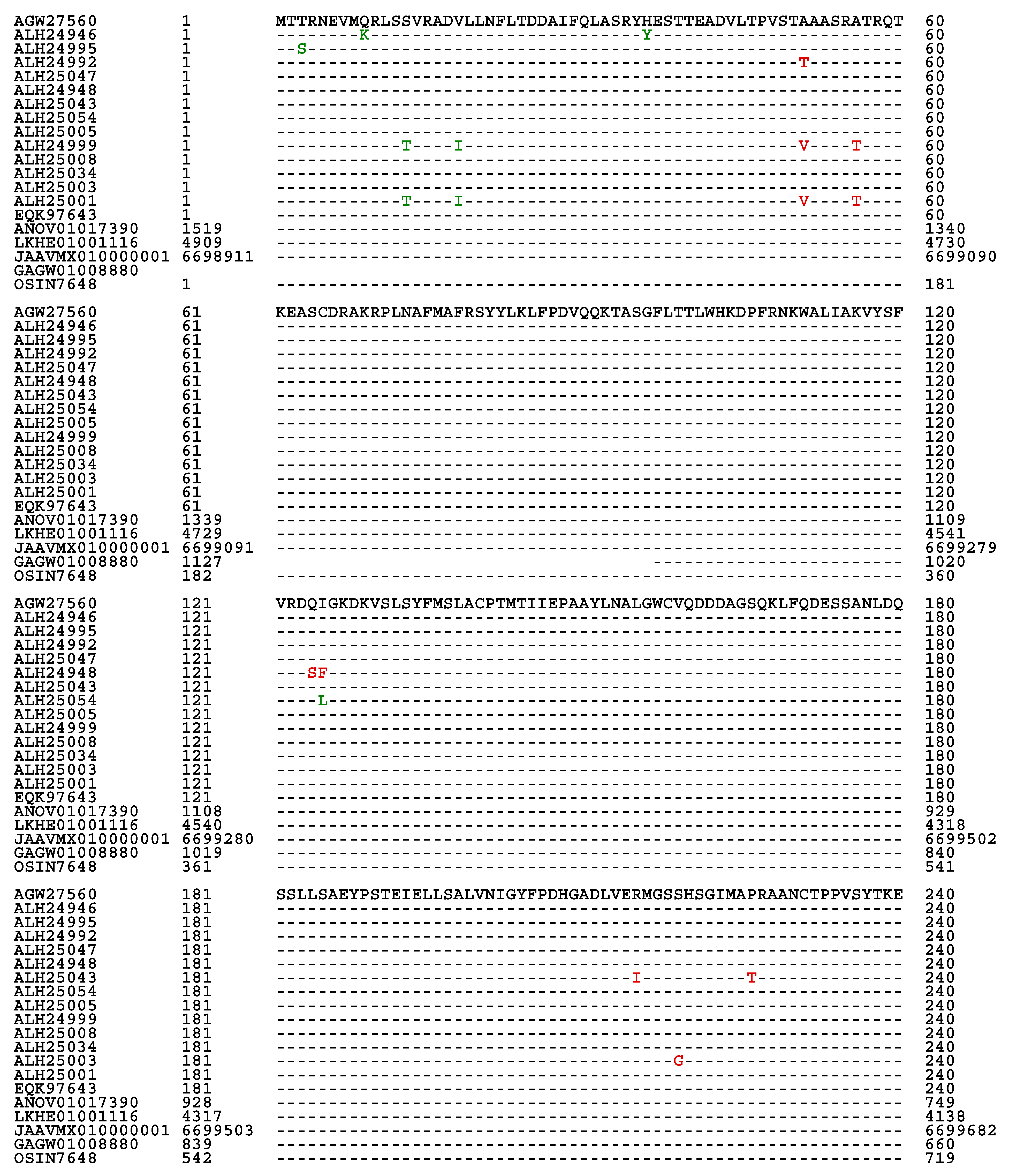

III-5. Primary Sequences of the MAT1-1-1 Proteins

Because of the diversity of the 3D structures of the proteins, the variations in the primary sequences of the MAT1-1-1 proteins were analyzed and are shown in

Figure 7. The 118 full-length MAT1-1-1 proteins (cf.

Table 1) consisted of 372 amino acids and contributed 15 diverse 3D structural morphs, as shown in

Figure 3. Among the 118 full-length proteins, 89 shared 100% sequence identity with the query protein sequence (AGW27560) whereas 20 other proteins shared 98.1−99.6% sequence similarity with the query sequence containing various conservatively and nonconservatively replaced residues at isolated sites, which may have an impact on the mating function.

Figure 7 shows the alignment of the full-length MAT1-1-1 protein sequences covering 5 Bayesian clusters (branches A1, A2, A3, B, C, D1, D2, E1, E2, E3, and E4; cf.

Figure 1) and 15 AlphaFold 3D structural morphs (cf.

Figure 3), as well as the MAT1-1-1 protein sequences encoded by the genome assemblies of H. sinensis and the metatranscriptome assemblies of natural C. sinensis.

The full-length MAT1-1-1 protein sequence EQK97643 (370 aa) was derived from H. sinensis strain Co18 under the AlphaFold UniProt T5A511 and published in GenBank on 22-MAR-2015 (cf.

Table 1;

Figure 3). A segment of the genome assembly ANOV01017390 (410←1519), which was also annotated as KE657544 (410←1519) in GenBank, was derived from the same H. sinensis strain but published in GenBank on 20-AUG-2013 and was found to be C-terminally truncated (352 aa; 95.1% query coverage vs. EQK97643).

Among the 138 MAT1-1-1 protein sequences, 20 are truncated at both the N- and C-termini, showing 68−80% query coverage and belonging to 9 diverse 3D structural morphs, as shown in

Figure 4. Eighteen of the 20 truncated proteins presented 100% sequence identity with the representative full-length MAT1-1-1 protein ALH24945 under the UniProt code U3N942 (cf.

Table S1,

Figure 1). Two other truncated proteins (AGW27522 and AGW27536) under the UniProt codes U3N6U0 and U3N7H7 shared 99.6−99.7% sequence similarity with the query sequence ALH24945 with either a nonconservative P-to-L substitution or an L residue deletion. AGW27522 and AGW27536 were clustered into Branches A2 and A3 of Cluster A, respectively.

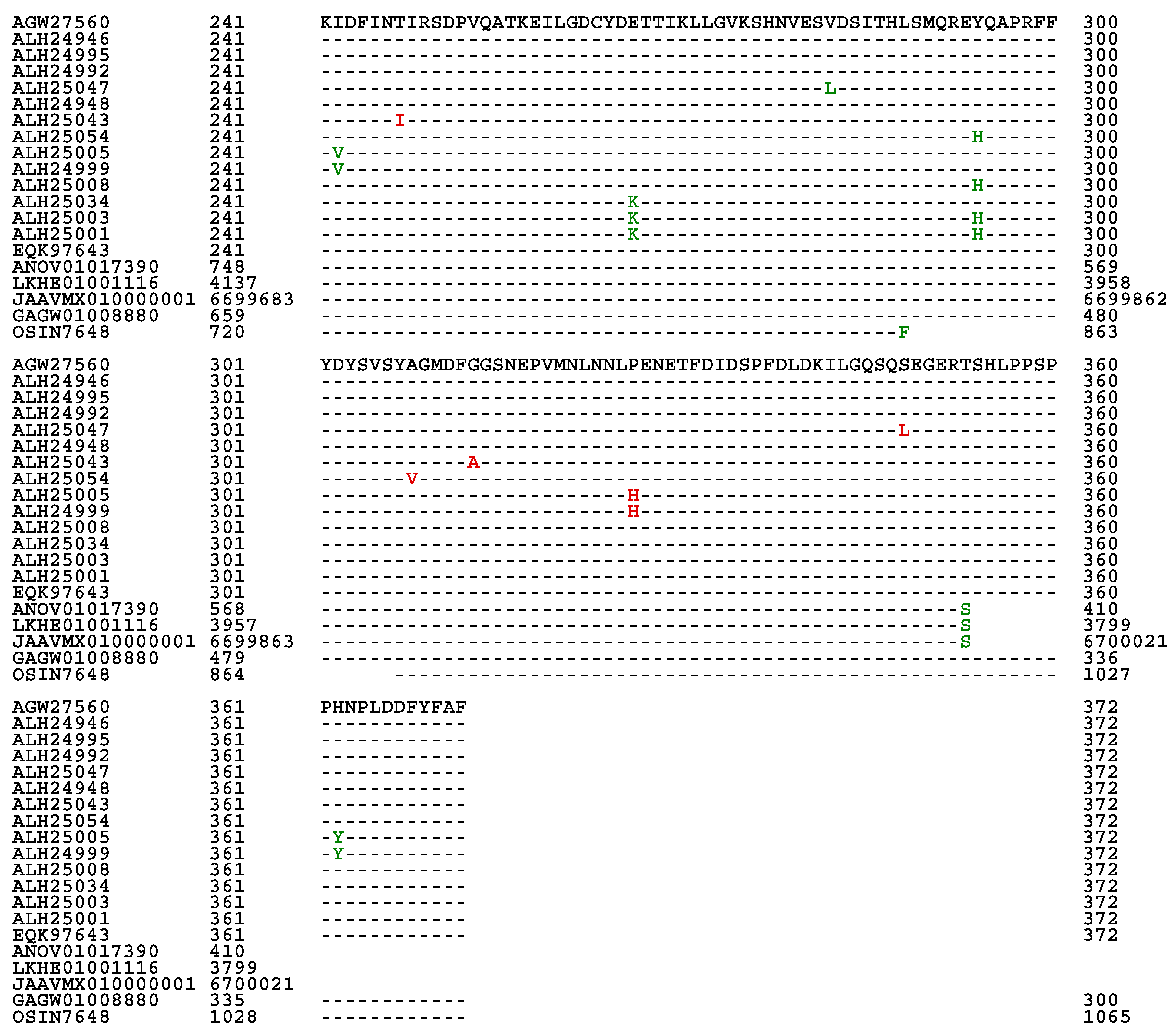

III-6. Primary Sequences of the MAT1-2-1 Proteins

Among the 74 MAT1-2-1 proteins available in the AlphaFold database, 69 are full-length proteins containing 249 amino acids and are attributed to diverse 3D structural morphs under 17 UniProt codes (cf.

Figure 5;

Table 2). Both accessions AEH27625 and ACV60400 of the MAT1-2-1 proteins were derived from H. sinensis strain CS2, sharing 100% sequence identity; however, they were published in GenBank on 25-JUL-2016 and 03-JUN-2010, respectively. Among the 69 full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins, 39 are 100% identical to the query sequence AEH27625 and are clustered into Branch I-1 of Cluster I of the Bayesian tree shown in

Figure 2. The remaining 30 full-length proteins share 97.6−99.6% sequence similarity with the query sequence, containing various conservatively and nonconservatively replaced residues at isolated sites, which may have an impact on the mating function.

Figure 8 shows the alignment of the full-length MAT1-2-1 protein sequences covering 5 Bayesian clusters (Branches I-1, I-2, II-1, II-2, III, IV-1, IV-2, V-1, and V-2; cf.

Figure 2) and 17 AlphaFold 3D structural morphs (cf.

Figure 5), as well as the MAT1-2-1 protein sequences encoded by the genome and transcriptome assemblies of H. sinensis and the metatranscriptome assembly of the natural C. sinensis specimen that was collected from Deqin, Yunnan Province, China. According to GenBank, both the MAT1-2-1 protein sequence EQL04085 and the genome assembly ANOV01000063 (9329→10182) were derived from H. sinensis strain Co18 and submitted to GenBank by the same group of authors. However, the genome assembly ANOV01000063 (9329→10182) contains a conservative S-to-A substitution, whereas EQL04085 does not contain this substitution. Note: the arrows “→” and “←” indicate sequences in the sense and antisense strands of the genomes, respectively.

The GenBank database contains 5 other MAT1-2-1 protein sequences, AFX66471, AFX66481, AFX66483, AFX66485, and AFX66486, which were derived from the C. sinensis isolates YN09_3, YN09_96, YN09_140, NP10_1, and NP10_2, respectively, with 3D structure records in the AlphaFold database for the MAT1-1-1 proteins but not for the MAT1-2-1 proteins. As shown in

Figure S1, these 5 protein sequences are 100% identical to the reference sequence ACV60363 of Branch V-1 of Cluster V in the Bayesian clustering tree (cf.

Figure 2,

Table 2), indicating that the 5 MAT1-2-1 protein sequences most likely belong to Branch V-1 of Cluster V (cf.

Figure 2), together with the reference protein ACV60363 within Branch V-1, and belong to the 3D structural morph under the AlphaFold code D7F2E3 shown in Panel K in

Figure 5.

In addition to the 74 full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins, 5 other protein sequences are C-terminally truncated, exhibiting 69−74% query coverage and 99.4−99.5% similarity in protein sequences to the reference AEH27625 of the full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins under the UniProt code D7F2E9. The 5 truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins contain a single conserved Y-to-H substitution, belonging to different 3D structural morphs under 4 AlphaFold UniProt codes (cf.

Figure 6).

III-7. Differential Genomic Occurrence of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Genes in H. sinensis

Table 3 lists the differential occurrence of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins encoded by the genome assemblies ANOV01017390, JAAVMX010000001, LKHE01001116, LWBQ01000021, and NGJJ01000619 of the H. sinensis strains Co18, IOZ07, 1229, ZJB12195, and CC1406-20395, respectively [Hu et al. 2013; Li et al. 2016a; Jin et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2020]. The genome assemblies LWBQ00000000 and NGJJ00000000 do not contain the genes encoding the MAT1-1-1 proteins, and the genome assembly JAAVMX000000000 does not contain the gene encoding the MAT1-2-1 protein.

IV. Discussion

IV-1. Heteromorphic 3D Structures of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Proteins in H. sinensis Strains and Wild-Type C. sinensis Isolates

The study presented in this paper demonstrated the heteromorphic 3D structures of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins in 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. Pairing of the mating proteins is essential for the sexual reproduction of O. sinensis during the lifecycle of natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complex. However, 75.7% of the strains/isolates contained either MAT1-1-1 or MAT1-2-1 proteins but did not generate corresponding pairing mating proteins. These strains/isolates were harvested from scattered production locations on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau. The harvesting location and protein accession information are available in both the GenBank and AlphaFold databases.

A total of 6 Bayesian clusters with clustering branches and 24 AlphaFold-predicted 3D structural morphs were demonstrated for the heteromorphic structures of 138 MAT1-1-1 proteins (cf.

Figure 1 and

Figure 3−4). The full-length and truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins belonged to 15 and 9 stereostructural morphs, respectively. Most authentic MAT1-1-1 proteins were clustered into Branch A1 of Cluster A in the Bayesian tree (cf.

Figure 1 and

Table 1), belonging to 3D structural morph A of the MAT1-1-1 proteins (cf.

Figure 3).

A total of 5 Bayesian clusters with clustering branches and 21 AlphaFold 3D structural morphs were demonstrated for the heteromorphic structures of 79 MAT1-2-1 proteins (cf.

Figure 2 and

Figure 4−5). The full-length and truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins belonged to 17 and 4 stereostructural morphs, respectively. Many of the MAT1-2-1 proteins were clustered into Branch I-1 of Cluster I in the Bayesian tree (cf.

Figure 2 and

Table 2), belonging to 3D structural morph A of the MAT1-2-1 proteins (cf.

Figure 4).

Zhang and Zhang (2015) reported 4.7% and 5.7% variations in the exon sequences of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes, respectively, in numerous wild-type C. sinensis isolates. Exon variations may disrupt the translation of coding sequences, in addition to alternative splicing and differential occurrence and transcription of mating genes, as reported by Li et al. [2023a, 2024]. The mutation rates reported by Zhang and Zhang [2015] appeared to be much greater than those present in the GenBank database, which includes numerous variable sequences of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins of C. sinensis isolates [Li et al. 2024]. Presumably, Zhang and Zhang [2015] might not have uploaded all the variable sequences to GenBank to truthfully represent the natural diversity of the variable stereostructures of the mating proteins.

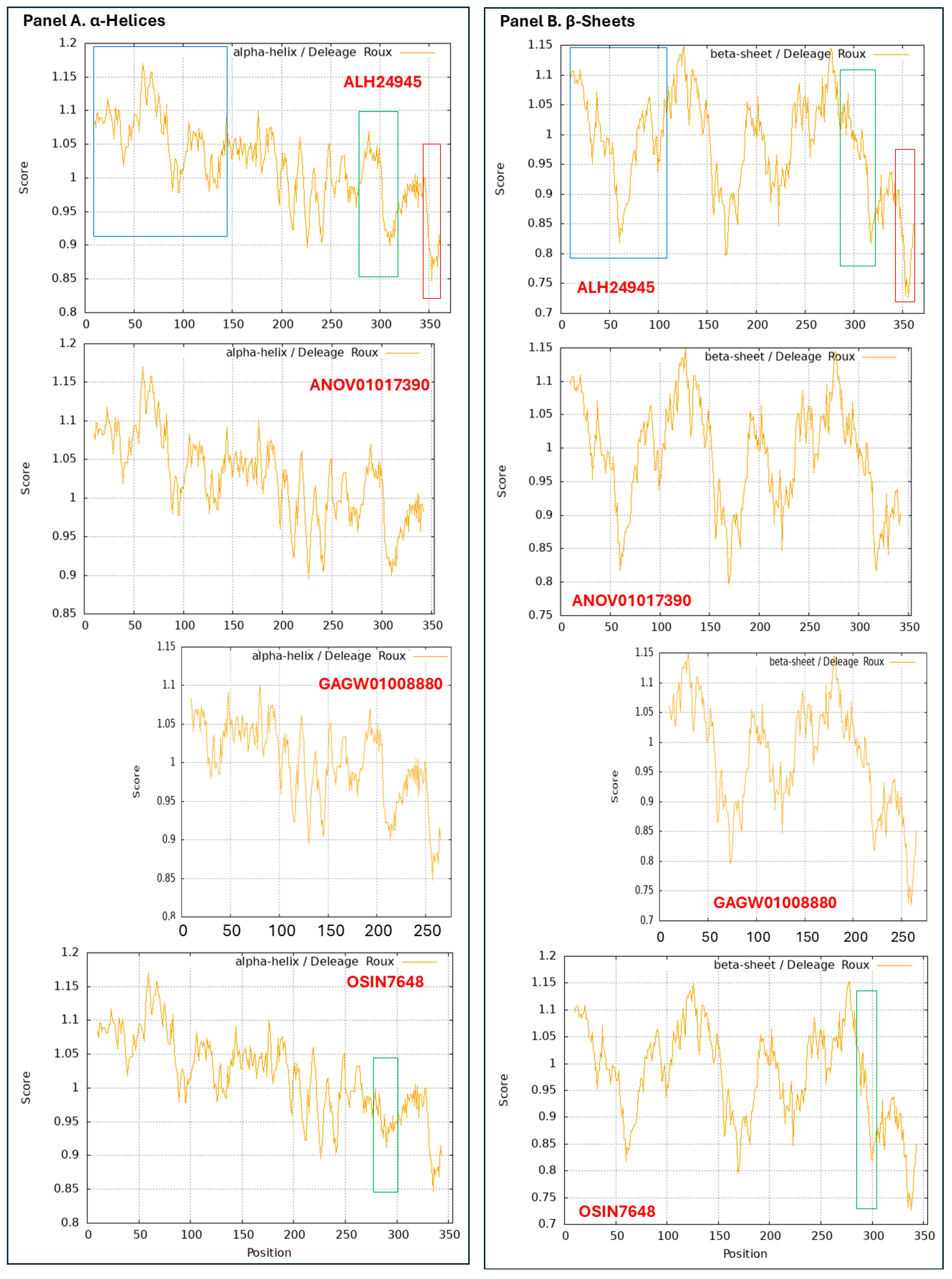

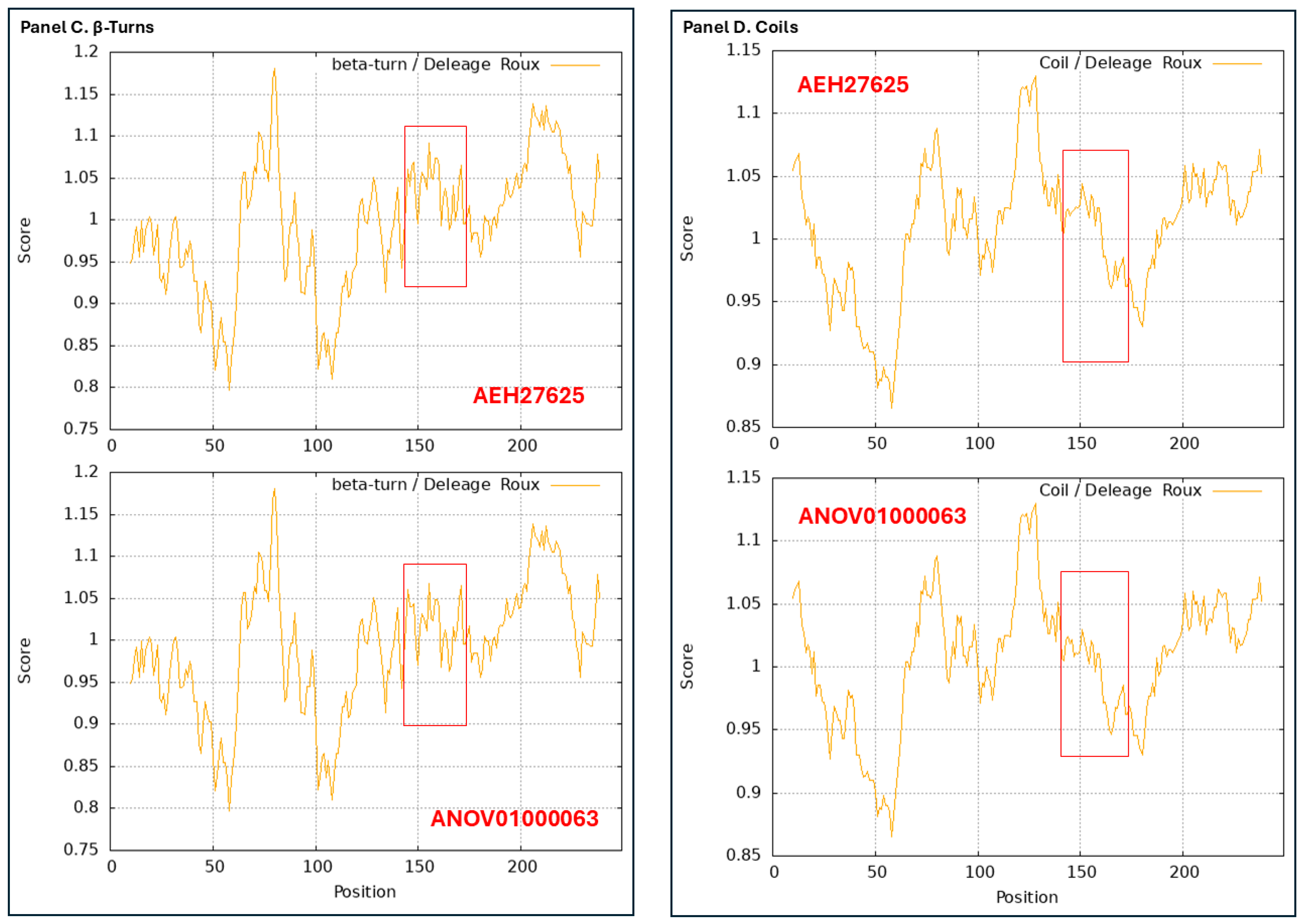

Although the AlphaFold database does not include the predicted 3D structures for the mating proteins encoded by the genome and transcriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains and the metatranscriptome assemblies of natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complexes, the 2D structures of the mutant MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins (including those with truncation of large protein segments) that were translated from the nucleotide sequences were analyzed to explore the variations in the α-helices, β-sheets, β-turns, and coils using ExPASy ProtScale technology (cf.

Figure 7). The apparent changes in the 2D structures of the mating proteins indicate altered 3D structures and subsequent dysfunction and even complete deactivation of the mating proteins.

The heteromorphic stereostructures of the mating proteins might explain, at least partially, why efforts made in the past 40−50 years to cultivate pure H. sinensis, Genotype #1 of the 17 O. sinense genotypes, in research-oriented academic settings to induce the production of fruiting bodies and ascospores have consistently failed, as reported and summarized previously [Holliday & Cleaver 2008; Stone 2010; Hu et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2013].

Table 3 and

Table 4 of this paper further confirmed the differential occurrence and transcription of the mating-type genes of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs in the genome and transcriptome assemblies of the H. sinensis strains and in the metatranscriptome assemblies of natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complex. Bushley et al. [2013] and Li et al. [2024] reported alternative splicing of the MAT1-2-1 gene with unspliced intron I, which contains 3 stop codons, in H. sinensis strain 1229. Consequently, the C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 protein lacked the major portion of the protein encoded by exons II and III of the gene.

IV-2. Differential Occurrence of MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 Proteins with Heteromorphic Structures in the H. sinensis Strains and C. sinensis Isolates

Uploaded in the AlphaFold database, 131 (75.7%) of the 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates generated either the MAT1-1-1 or the MAT1-2-1 proteins but not both. This phenomenon was confirmed by the differential occurrence and differential translation of the mating proteins encoded by the genome, transcriptome, and metatranscriptome assemblies of the H. sinensis strains and natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complexes (cf.

Table 3 and

Table 4).

However, 42 other strains/isolates (24.3%) produced both MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins, the sequences of which were derived from genomic DNA obtained from the H. sinensis strains or wild-type C. sinensis isolates but, unfortunately, not from direct biochemical examinations of the proteins. In addition to the intracellular biological processes of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins, such as differential transcription and alternative splicing of the genes, as reported by Li et al. [2024], the heteromorphic 3D structures of the mating proteins may need to be added to the scope of consideration for the functional expression of the proteins involved in the sexual reproduction of O. sinensis.

The MAT1-1-1 proteins produced from 35 of 42 strains/isolates were clustered into Bayesian Cluster A (cf.

Figure 1), accompanied by one of 20 MAT1-2-1 proteins clustered into Bayesian Cluster I or 15 MAT1-2-1 proteins clustered into Bayesian Cluster V (cf.

Figure 2). These results will be useful for future design of protein biochemical and reproductive physiological research to explore the functionalities of mating proteins that are clustered into different Bayesian clusters and have diverse stereostructural morphs. The most challenging aspect of biochemical examinations is to determine the stereostructures of fully functioning proteins under native conditions or after renaturation [Zhu & Gray 1994].

IV-3. Sexual Reproductive Behavior of H. sinensis, Genotype #1 of O. sinensis

Sexual reproduction of O. sinensis is crucial for maintaining the natural population volume of the C. sinensis insect-fungi complex, which is endangered at Level 2, not only because of the co-occurrence of the mating-type genes of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs but also because of the appropriate pairing of the fully functioning MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins. The following hypotheses have been previously proposed for H. sinensis, the postulated sole-anamorph of O. sinensis [Wei et al. 2006]: homothallism [Hu et al. 2013], pseudohomothallism [Bushley et al. 2013], and facultative hybridization [Zhang & Zhang 2015], all of which were based on the nucleotide data derived from H. sinensis genome and transcriptome studies. In theory, self-fertilization under homothallism and pseudohomothallism in ascomycetes becomes a reality when the appropriately paired MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins exhibit mating functions within a single fungal cell [Turgeon & Yoder 2000; Debuchy & Turgeo 2006; Jones & Bennett 2011; Zhang et al. 2011; Bushley et al. 2013; Hu et al. 2013; Zheng & Wang 2013; Wilson et al. 2015; Zhang & Zhang 2015]. However, after thoroughly analyzing genetic and transcriptional data for H. sinensis in the literature, Li et al. [2023a, 2024] reported differential occurrence, alternative splicing, and differential transcription of the mating-type genes of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs in 237 H. sinensis strains. Thus, the evidence indicated that H. sinensis, which is Genotype #1 of the 17 genomically independent O. sinensis genotypes, was self-sterilizing and incapable of completing self-fertilization but requires sexual partners to accomplish O. sinensis sexual reproduction under heterothallism or hybridization.

The alternative splicing and differential occurrence and transcription of the mating-type genes and the diversity of heteromorphic 3D structures of the mating proteins with functional alterations indicate that two or more H. sinensis populations, either monoecious or dioecious, may participate as sexual partners capable of producing either the functioning MAT1-1-1 or MAT1-2-1 proteins for reciprocal pairing during successful physiological heterothallism crossing. Thus, pheromones and pheromone receptor proteins will play a critical role in sexual signal communication between sexual partners. If this assumption is correct, the sexual partners might possess indistinguishable H. sinensis-like morphological and growth characteristics, as elucidated previously [Kinjo & Zang 2001; Zhang et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2011; Li et al. 2013; Mao et al. 2013]. For example, the indistinguishable H. sinensis strains 1229 and L0106 produce complementary transcripts of the mating-type genes and mating proteins of the MAT1-1 and MAT1-2 idiomorphs [Bushley et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2015; Li et al. 2023a, 2024].

Even if the physiological heterothallism hypothesis is incorrect for O. sinensis, one of the mating proteins might be produced by heterospecific fungal species, which would result in plasmogamy and the formation of heterokaryotic cells (cf.

Figure 3 of [Bushley et al. 2013]) to ensure successful sexual hybridization or even parasexual reproduction if the heterospecific species are capable of breaking interspecific reproduction isolation, similar to many cases of fungal sexual hybridization and parasexual reproduction that promote adaptation to the extremely adverse ecological environment on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau [Pfennig 2007; Seervai et al. 2013; Seervai et al. 2013; Nakamura et al. 2019; Du et al. 2020; Hėnault et al. 2020; Samarasinghe et al. 2020; Mishra et al. 2021; Steensels et al. 2021; Kück et al. 2022]. Alternatively, to complete physiological heterothallism or hybridization for reproduction, mating partners might exist in adjacent hyphal cells, which might determine their mating choices, and they may communicate with each other through a mating signal-based transduction system of pheromones and pheromone receptors and form “H”-shaped crossings of multicellular hyphae [Hu et al. 2013; Bushley et al. 2013; Mao et al. 2013]. In fact, Mao et al. [2013] illustrated the “H”-shaped morphology in C. sinensis hyphae that genetically contained either AT-biased Genotype #4 or #5 of O. sinensis without co-occurrence of the GC-biased Genotype #1 H. sinensis and that the genome-independent AT-biased O. sinensis genotypes shared indistinguishable H. sinensis-like morphological and growth characteristics. To date, no study has reported identifications of a and α pheromone genes in the genome or transcriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains or in the metatranscriptome assemblies of natural C. sinensis; however, the a and α pheromone receptor genes were found to differentially occur in the genome, transcriptome, and metatranscriptome assemblies [Hu et al. 2013; Li et al. 2024].

IV-4. Sexual Reproduction Strategy During the Lifecycle of Natural C. sinensis Insect-Fungi Complex

In addition to the intensive attention given to H. sinensis subspecies or subpopulations, the N-terminally and midsequence truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins and the variable MAT1-2-1 proteins encoded by the metatranscriptome assemblies of the natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complex exhibit alterations in the 2D structures of the proteins (cf.

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). The results suggest heteromorphic 3D structures of the mating proteins and dysfunctional or anomalous fungal mating processes during the lifecycle of natural C. sinensis.

Li et al. [2016b] reported the genetic heterogeneity of wild-type C. sinensis isolates CH1 and CH2, isolated from the intestines of healthy living larvae of Hepialus lagii Yan, on the basis of the H. sinensis-like morphology and growth characteristics. The C. sinensis isolates CH1 and CH2 contained GC-biased Genotype #1 (H. sinensis) and AT-biased Genotypes #4−5 of O. sinensis, as well as Paecilomyces hepiali [Dai et al. 1989], which was renamed Samoneilla hepiali in 2020 [Wang et al. 2020]. The impure C. sinensis isolates exhibited 15−39-fold greater inoculation potency on the larvae of Hepialus armoricanus than did pure H. sinensis (n=100 for each inoculant experiment; P<0.001), indicating the symbiosis of multiple intrinsic fungi during the lifecycle of natural C. sinensis, at least in the larval infection stage [Li et al. 2016b]. The genetic heterogeneity of the wild-type C. sinensis isolates suggests that the coexisting MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins detected in 24.3% of the wild-type C. sinensis isolates might have been derived from genome-independent heterospecific fungi, which may pair complementarily and reciprocally to accomplish mating processes during the heterothallic or hybrid reproduction of O. sinensis. The different fungal sources for the cooccurring MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins are evidenced by the species contradiction between the inoculants (3 GC-biased H. sinensis strains) and the sole-teleomorph of genome-independent AT-biased Genotype #4 reportedly as exclusively existing in the fruiting body of cultivated C. sinensis [Wei et al. 2016]. These authors reported that the successful artificial inoculation-based cultivation project under product-oriented industrial settings used a special cultivation strategy without pursuing strict fungal purification by adding soil that was transported from natural C. sinensis production areas into the industrial cultivation system [Wei et al. 2016].

Li et al. [2013] reported the genetic heterogeneity of 15 cultures of 2 groups derived after 25 days of in vitro incubation at 18 °C from monoascospores, the reproductive cells of natural C. sinensis. The first group included 7 homogeneous clones (1207, 1218, 1219, 1221, 1222, 1225, and 1229), containing only H. sinensis (GC-biased Genotype #1 of O. sinensis). The second group included 8 heterogeneous clones (1206, 1208, 1209, 1214, 1220, 1224, 1227, and 1228), containing both GC-biased Genotype #1 and AT-biased Genotype #5 of O. sinensis. The sequences of the GC- and AT-biased O. sinensis genotypes reside in independent genomes and belong to independent fungi [Xiao et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2010; Zhu & Li 2017; Li et al. 2022, 2024]. Bushley et al. [2013], the collaborators of Li et al. [2013], observed multicellular heterokaryotic hyphae and ascospores of natural C. sinensis with mononucleated, binucleated, trinucleated, and tetranucleated structures and reported the PCR results for 22 clones, which included 7 additional clones (1210, 1211, 1212, 1213, 1216, 1223, and 1226) forming the third group of ascosporic clones in addition to the aforementioned first and second groups of clones (cf.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 of [Bushley et al. 2013]). However, neither Bushley et al. [2013] nor Li et al. [2013] reported the genetic features of the third group of ascosporic clones. There is no doubt from the 2 literature reports that the ascosporic clones of the third group were genetically distinct from those in the homogeneous first group or the heterogeneous second group.

Zhang and Zhang [2015] suggested that the nuclei of binucleated hyphal and ascosporic cells (as well as mononucleated, trinucleated, and tetranucleated cells) of natural C. sinensis likely contain different genetic materials. These multicellular hyphal and ascosporic cells of natural C. sinensis might contain two or more sets of genomes of independent fungi, which might be responsible for the production of complementary mating proteins for sexual reproductive outcrossing. Thus, the monoascospores of natural C. sinensis might be characterized by more complex genetic heterogeneity, coexisting with more heterospecific fungal species than the cooccurring GC-biased Genotype #1 and AT-biased Genotype #5, which were disclosed by Li et al. [2013].

Unlike the culture-dependent experiments that were apparently unable to detect nonculturable fungal species, Li et al. [2023b, 2023c] reported culture-independent studies and demonstrated the genetic heterogeneity of C. sinensis ascospores and the stromal fertile portion (SFP) that is densely covered with numerous ascocarps, which are the reproductive cells and organs of natural C. sinensis. These authors observed semi and fully ejected ascospores of natural C. sinensis and reported the cooccurrence of the GC-biased O. sinensis Genotypes #1 and #13/14, AT-biased O. sinensis Genotypes #5‒6 and #16 within AT-biased clade A in the Bayesian phylogenetic tree, S. hepiali (≡ P. hepiali), and an AB067719-type fungus. In addition, the C. sinensis SFP contained another fungal group, AT-biased O. sinensis Genotypes #4 and #15, which were clustered into AT-biased clade B in the Bayesian phylogenetic tree [Li et al. 2023c]. Genotypes #4 and #15 were absent in the ascospores, consistent with the culture-dependent study results [Li et al. 2013]. The abundance of fungal components exhibited marked dynamic alterations in a disproportional and asynchronized manner in the C. sinensis SFP before and after ascospore ejection and in the 2 types of ascospores [Li et al. 2023b]. Thus, the coexistence of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins detected from the wild-type C. sinensis isolates might have been derived interindividually from fungi that might serve as mating partners of O. sinensis to accomplish heterothallic or hybrid reproduction.

Li et al. [2023a, 2024] summarized prior scientific evidence regarding the sexual reproduction of O. sinensis. On the basis of genetic heterogeneity with multiple heterospecific fungal species in natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complexes and multicellular heterokaryotic structures of ascospores and hyphae, the scientific evidence may be divided into 2 aspects: (1) the 17 cooccurring genome-independent genotypes of O. sinensis in different combinations and (2) the taxonomically heterospecific fungal species, on the basis of the mycobiota of >90 cocolonizing fungi belonging to at least 37 fungal genera in the stroma and caterpillar body of natural C. sinensis [Zhang et al. 2010, 2018; Xiang et al. 2014; Meng et al. 2015; Xia et al. 2015, 2017; Guo et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018; Zhong et al. 2018; Li et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2021; Kang et al. 2024].

- (1-a).

Differential occurrence of AT-biased Genotype #4 or #5 of O. sinensis without the cooccurrence of GC-biased H. sinensis in natural C. sinensis specimens collected from different production areas in geographically remote locations [Engh 1999; Kinjo and Zang 2001; Stensrud et al. 2005, 2007; Mao et al. 2013].

- (1-b).

Multiple cooccurring GC- and AT-biased genotypes of O. sinensis have been observed differentially in different combinations in the stroma, caterpillar body, ascocarps and ascospores of natural C. sinensis [Xiao et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2010; Li et al. 2013, 2022, 2023b, 2023c; Mao et al. 2013]. The abundances of the O. sinensis genotypes underwent dynamic alterations in an asynchronous, disproportional manner in the caterpillar bodies and stromata of C. sinensis specimens during maturation, with a consistent predominance of the AT-biased genotypes of O. sinensis, not the GC-biased H. sinensis, in the stromata, indicating that the sequences of O. sinensis genotypes were present in independent genomes of different fungi [Xiao et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2010; Gao et al. 2011, 2012; Hu et al. 2013; Li et al. 2013, 2016a, 2020, 2022, 2023b; Zhu & Li 2017; Jin et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020; Shu et al. 2020].

- (1-c).

The GC-biased Genotypes #1 and #2 of O. sinensis cooccur in the stromata of natural C. sinensis; the abundance of the GC-biased genotypes was dynamically altered during C. sinensis maturation [Zhu et al. 2010; Gao et al. 2011, 2012].

- (1-d).

The cooccurrence of GC-biased genomically independent Genotypes #1 and #7 of O. sinensis was detected in the same specimen of natural C. sinensis [Chen et al. 2011].

- (1-e).

Species contradiction between the anamorphic inoculants (GC-biased Genotype #1 H. sinensis strains) and the sole-teleomorph of AT-biased Genotype #4 of O. sinensis detected in the fruiting body of cultivated C. sinensis [Wei et al. 2016].

- (1-f).

Discovery of Genotypes #13 and #14 of O. sinensis in semi and fully ejected multicellular heterokaryotic ascospores, respectively, from the same C. sinensis specimens [Li et al. 2023c].

- (1-g).

The genetic heterogeneity of ascospores and SFP, the reproductive cells and organs of natural C. sinensis, involves multiple GC- and AT-biased O. sinensis genotypes in different combinations [Li et al. 2013, 2022, 2023b, 2023c].

- (2-a).

Mycobiota findings for differential cooccurrence of >90 fungal species of at least 37 fungal genera in the caterpillar bodies and stromata of natural C. sinensis [Zhang et al. 2010, 2018; Xia et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2017; Zhong et al. 2018; Kang et al. 2024].

- (2-b).

A good number of C. sinensis isolates contained mutant MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins, especially those proteins with C- and/or N-terminal truncations that belonged to 9 and 4 diverse 3D structural morphs (cf.

Figure 4 and

Figure 6), respectively. The mutant proteins were either clustered into a separate Bayesian clade or clustered within the main clustering branches in the Bayesian trees (cf.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins encoded by metatranscriptome assemblies of natural C. sinensis also exhibited either large-segment truncation or sequence variations similar to those observed in wild-type C. sinensis isolates (cf.

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Some of the mutant proteins might be produced by heterospecific fungi in the impure wild-type C. sinensis isolates and in the natural C. sinensis insect-fungal complex.

- (2-c).

Discoveries of the formation of the heterospecific Cordyceps‒Tolypocladium complex in natural C. sinensis [Engh 1999; Stensrud et al. 2005, 2007] and the dual anamorphs of O. sinensis, involving psychrophilic H. sinensis and mesophilic Tolypocladium sinensis [Li 1988; Chen et al. 2004; Leung et al. 2006; Barseghyan et al. 2011].

- (2-d).

A close association of psychrophilic H. sinensis and mesophilic S. hepiali (≡ P. hepiali) has been found in the caterpillar body, stroma, and stromal fertile portion that is densely covered with numerous ascocarps, and ascospores of natural C. sinensis and in the wild-type C. sinensis complexes, which appear to be difficult to purify [Dai et al. 1989; Jiang & Yao 2003; Chen et al. 2004; Zhu et al. 2007, 2010; Yang et al. 2008; Li et al. 2016b, 2023c; Zhu & Li 2017].

- (2-e).

Although Genotypes #13−14 are among the 17 genotypes of O. sinensis, these 2 GC-biased genotypes feature precise reciprocal cross substitutions of large DNA segments among 2 heterospecific parental fungi, namely, H. sinensis and an AB067719-type fungus. The taxonomic position of the AB067719-type fungus is undetermined to date, and more than 900 heterospecific fungal sequences, which are highly homologous to AB067719, have been uploaded to GenBank [Li et al. 2023c]. Chromosomal intertwining and genetic material recombination may occur after plasmogamy and karyogamy of the heterospecific parental fungi under sexual reproduction hybridization or parasexuality, which is characterized by the prevalence of heterokaryosis and results in concerted chromosome loss for transferring-substituting genetic materials without conventional meiosis [Bennett & Johnson 2003; Sherwood & Bennett 2009; Bushley et al. 2013; Seervai et al. 2013; Nakamura et al. 2019; Mishra et al. 2021; Kück et al. 2022; Li et al. 2023c].

Whether the different genotypes of O. sinensis or heterospecific fungal species select each other as sexual partners depends on their mating choices for hybridization and their ability to break interspecific isolation barriers to adapt to extremely harsh ecological environments on the Qinghai‒Tibet Plateau and the seasonal climate changes from extremely cold winters, when C. sinensis is in its asexual growth phase, to the warmer springs and early summers, when C. sinensis switches to the sexual reproduction phase [Pfennig 2007; Du et al. 2020; Hėnault et al. 2020; Samarasinghe et al. 2020; Steensels & Gallone 2021].

V. Conclusions

The analysis of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins in the 173 H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates revealed heteromorphic stereostructures of the mating proteins, which were clustered into multiple Bayesian clustering clades and branches. In addition to the evidence of alternative splicing and differential occurrence and translation of the MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 genes in H. sinensis [Li et al. 2023a, 2024], the diversity of heteromorphic mating proteins suggested stereostructure-related alterations in the mating functions of proteins and provided additional evidence supporting the self-sterility hypothesis under heterothallic and hybrid reproduction for O. sinensis, including H. sinensis, Genotype #1 of the 17 genome-independent O. sinensis genotypes. The heteromorphic stereostructures of the mutant MAT1-1-1 and MAT1-2-1 proteins discovered in wild-type C. sinensis isolates and natural C. sinensis insect-fungi complexes may suggest diverse sources of the mating proteins produced by two or more cooccurring heterospecific fungal species in natural C. sinensis that have been discovered in mycobiota, molecular, metagenomic, and metatranscriptomic studies, regardless of whether culture-dependent or culture-independent research strategies were used.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. Mu Zang, Prof. Ru-Qin Dai, Prof. Ping Zhu, Prof. Wei Liu, and Prof. Zong-Qi Liang for their consultation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, XZL, YLL, and JSZ; methodology, JSZ; formal analysis, JSZ; investigation, XZL and JSZ; data curation, XZL and JSZ; writing–original draft preparation, JSZ; writing—review and editing, XZL, YLL, and JSZ; project administration, YLL; funding acquisition, YLL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by (1) the Major Science and Technology Projects of Qinghai Province, China (#2021-SF-A4); (2) the Joint Science Project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qinghai Provincial Government, and Sanjiangyuan National Park (#LHZX-2022-01); (3) the grant “The protective harvesting and utilization project for Ophiocordyceps sinensis in Qinghai Province” (#QHCY-2023-057) awarded by Qinghai Province of China; and (4) Qinghai Province Science and Technology Commissioner Special Project (#2024-NK-P67).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable because this paper is an in silico reanalysis of public data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable because this paper is a public bioinformatic data reanalysis.

Data Availability Statement

All sequence and 3D structure data are available in the GenBank and AlphaFold databases, except for one set of metatranscriptome sequences from natural C. sinensis that was uploaded to the repository database

www.plantkingdomgdb.com/Ophiocordyceps_sinensis/data/cds/Ophiocordyceps_sinensis_CDS.fas by Xia et al. [2017], which is currently inaccessible, but a previously downloaded cDNA file (accessed on 18 January 2018) was used for the mating protein analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abramson J, Adler J, Dunger J, Evans R, Green T, Pritzel A, Ronneberger O, Willmore L, Ballard AJ, Bambrick J, Bodenstein SW, Evans DA, Hung CC, O'Neill M, Reiman D, Tunyasuvunakool K, Wu Z, Žemgulytė A, Arvaniti E, Beattie C, Bertolli O, Bridgland A, Cherepanov A, Congreve M, Cowen-Rivers AI, Cowie A, Figurnov M, Fuchs FB, Gladman H, Jain R, Khan YA, Low CMR, Perlin K, Potapenko A, Savy P, Singh S, Stecula A, Thillaisundaram A, Tong C, Yakneen S, Zhong ED, Zielinski M, Žídek A, Bapst V, Kohli P, Jaderberg M, Hassabis D, Jumper JM. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature. 2024; 630(8016): 493-500. [CrossRef]

- Barseghyan GS, Holliday JC, Price TC, Madison LM, Wasser SP. Growth and cultural-morphological characteristics of vegetative mycelia of medicinal caterpillar fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis G.H. Sung et al. (Ascomycetes) Isolates from Tibetan Plateau (P.R.China). Intl. J. Med. Mushrooms. 2011; 13(6): 565−581. [CrossRef]

- Bennett RJ, Johnson AD. Completion of a parasexual cycle in Candida albicans by induced chromosome loss in tetraploid strains. EMBO J. 2003; 22(10): 2505−2515. [CrossRef]

- Bushley KE, Li Y, Wang W-J, Wang X-L, Jiao L, Spatafora JW, Yao Y-J. Isolation of the MAT1-1 mating type idiomorph and evidence for selfing in the Chinese medicinal fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Fungal Biol. 2013; 117(9): 599−610. [CrossRef]

- Chen C-S, Hseu R-S, Huang C-T. Quality control of Cordyceps sinensis teleomorph, anamorph, and Its products. Chapter 12, in (Shoyama, Y., Ed.) Quality Control of Herbal Medicines and Related Areas. InTech, Rijeka, Croatia (2011). pp. 223–238. www.intechopen.com.

- Chen Y-Q, Hu B, Xu F, Zhang W, Zhou H, Qu L-H. Genetic variation of Cordyceps sinensis, a fruit-body-producing entomopathogenic species from different geographical regions in China. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004; 230: 153–158. [CrossRef]

- Dai R-Q, Lan J-L, Chen W-H, Li X-M, Chen Q-T, Shen C-Y. Discovery of a new fungus Paecilomyces hepiali Chen & Dai. Acta Agricult. Univ. Pekin. 1989; 15(2): 221−224.

- David A, Islam S, Tankhilevich E, Sternberg MJE. The AlphaFold Database of Protein Structures: A Biologist’s Guide. J Mol Biol. 2022; 434(2): 167336. [CrossRef]

- Debuchy R, Turgeo BG. Mating-Type Structure, Evolution, and Function in Euascomycetes. In (eds. Kües U. & Fischer, R.) Growth, Differentiation and Sexuality. Springer (2006). pp. 293–323.

- Deleage G, Roux B. An algorithm for protein secondary structure prediction based on class prediction. Protein Engineering, Design and Selection 1987; 1: 289–294. [CrossRef]

- Du X-H, Wu D-M, Kang H, Wang H-C, Xu N, Li T-T, Chen K-L. Heterothallism and potential hybridization events inferred for twenty-two yellow morel species. IMA Fungus. 2020; 11: 4. [CrossRef]

- scientific thesis, Department of Biology, University of Oslo, 1999.

- Gao L, Li X-H, Zhao J-Q, Lu J-H, Zhu J-S. Detection of multiple Ophiocordyceps sinensis mutants in premature stroma of Cordyceps sinensis by MassARRAY SNP MALDI-TOF mass spectrum genotyping. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2011; 43(2): 259–266.

- Gao L, Li X-H, Zhao J-Q, Lu J-H, Zhao J-G, Zhu J-S. Maturation of Cordyceps sinensis associates with alterations of fungal expressions of multiple Ophiocordyceps sinensis mutants with transition and transversion point mutations in stroma of Cordyceps sinensis. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao. 2012; 44(3): 454–463.

- Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, Bairoch A. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the Expasy Server. Chapter 52 (In) John M. Walker (ed): The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, Humana Press (2005). pp. 571–607.

- Guo M-Y, Liu Y, Gao Y-H, Jin T, Zhang H-B, Zhou X-W. Identification and bioactive potential of endogenetic fungi isolated from medicinal caterpillar fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis from Tibetan Plateau. Int J Agric Biol. 2017; 19: 307‒313. [CrossRef]

- Hawksworth DL, Crous PW, Redhead SA, Reynolds DR, Samson RA, Seifert KA, and 82 other authors. The Amsterdam declaration on fungal nomenclature. IMA Fungus. 2011; 2: 105−112. [CrossRef]

- Hėnault M, Marsit S, Charron G, Landry CR. The effect of hybridization on transposable element accumulation in an undomesticated fungal species. eLife. 2020; 9, e60474. [CrossRef]

- Holliday J, Cleaver M. Medicinal value of the caterpillar fungi species of the genus Cordyceps (Fr.) Link (Ascomycetes). A review. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms. 2008; 10: 219–234. [CrossRef]

- Hu X, Zhang Y-J, Xiao G-H, Zheng P, Xia Y-L, Zhang X-Y, St Leger RJ, Liu X-Z, Wang C-S. Genome survey uncovers the secrets of sex and lifestyle in caterpillar fungus. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2013; 58: 2846–2854. [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogeny. Bioinformat. 2001; 17: 754−755. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Yao Y-J. A review for the debating studies on the anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis. Mycosistema. 2003; 22(1): 161–176.

- Jin L-Q, Xu Z-W, Zhang B, Yi M, Weng C-Y, Lin S, Wu H, Qin X-T, Xu F, Teng Y, Yuan S-J, Liu Z-Q, Zheng Y-G. Genome sequencing and analysis of fungus Hirsutella sinensis isolated from Ophiocordyceps sinensis. AMB Expr. 2020; 10: 105. [CrossRef]

- Jones SK, Bennett RJ. Fungal mating pheromones: choreographing the dating game. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011; 48(7): 668–676. [CrossRef]

- Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021; 596; 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Kang Q, Zhang J, Chen F, Dong C, Qin Q, Li X, Wang H, Zhang H and Meng Q. Unveiling mycoviral diversity in Ophiocordyceps sinensis through transcriptome analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2024; 15: 1493365. [CrossRef]

- Kinjo N, Zang M. Morphological and phylogenetic studies on Cordyceps sinensis distributed in southwestern China. Mycoscience. 2001; 42: 567–574. [CrossRef]

- Kück U, Bennett RJ, Wang L and Dyer PS. Editorial: Sexual and Parasexual Reproduction of Human Fungal Pathogens. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022; 12:934267. [CrossRef]

- Leung P-H, Zhang Q-X, Wu J-Y. Mycelium cultivation, chemical composition and antitumour activity of a Tolypocladium sp. fungus isolated from wild Cordyceps sinensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006; 101: 275−283. [CrossRef]

- Li C-L. A study of Tolypocladium sinense C.L. Li. sp. nov. and cyclosporin production. Acta Mycol. Sinica. 1988; 7: 93−98.

- Li X, Wang F, Liu Q, Li Q-P, Qian Z-M, Zhang X-L, Li K, Li W-J, Dong C-H. Developmental transcriptomics of Chinese cordyceps reveals gene regulatory network and expression profiles of sexual development-related genes. BMC Genomics. 2019; 20: 337. [CrossRef]

- Li X-Z, Li Y-L, Yao Y-S, Xie W-D, Zhu J-S. Further discussion with Li et al. (2013, 2019) regarding the “ITS pseudogene hypothesis” for Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020; 146: 106728. [CrossRef]

- Li X-Z, Li Y-L, Zhu J-S. Differential transcription of mating-type genes during sexual reproduction of natural Cordyceps sinensis. Chin. J. Chin. Materia Medica. 2023a; 48(10): 2829–2840. [CrossRef]

- Li X-Z, Xiao M-J, Li Y-L, Gao L, Zhu J-S. Mutations and differential transcription of mating-type and pheromone receptor genes in Hirsutella sinensis and the natural Cordyceps sinensis insect‒fungi complex. Biol. (Basel) 2024; 13(8): 632. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Hsiang T, Yang R-H, Hu X-D, Wang K, Wang W-J, Wang X-L, Jiao L, Yao Y-J. Comparison of different sequencing and assembly strategies for a repeat-rich fungal genome, Ophiocordyceps sinensis. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2016a; 128: 1−6. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Jiao L, Yao Y-J. Non-concerted ITS evolution in fungi, as revealed from the important medicinal fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013; 68: 373−379. [CrossRef]

- Li Y-L, Gao L, Yao Y-S, Wu Z-M, Lou Z-Q, Xie W-D, Wu J-Y, Zhu J-S. Altered GC- and AT-biased genotypes of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in the stromal fertile portions and ascospores of natural Cordyceps sinensis. PLoS ONE. 2023b; 18(6): e0286865. [CrossRef]

- Li Y-L, Li X-Z, Yao Y-S, Wu Z-M, Gao L, Tan N-Z, Lou Z-Q, Xie W-D, Wu J-Y, Zhu J-S. Differential cooccurrence of multiple genotypes of Ophiocordyceps sinensis in the stromata, stromal fertile portion (ascocarps) and ascospores of natural Cordyceps sinensis. PLoS ONE. 2023c; 18(3): e0270776. [CrossRef]

- Li Y-L, Li X-Z, Yao Y-S, Xie W-D, Zhu J-S. Molecular identification of Ophiocordyceps sinensis genotypes and the indiscriminate use of the Latin name for the multiple genotypes and the natural insect-fungi complex. Am J BioMed Sci. 2022b; 14(3): 115–135. [CrossRef]

- Li Y-L, Yao Y-S, Zhang Z-H, Xu H-F, Liu X, Ma S-L, Wu Z-M, Zhu J-S. Synergy of fungal complexes isolated from the intestines of Hepialus lagii larvae in increasing infection potency. J. Fungal Res. 2016b; 14, 96−112.

- Liu J, Guo L-N, Li Z-W, Zhou Z, Li Z, Li Q, Bo X-C, Wang S-Q, Wang J-L, Ma S-C, Zheng J, Yang Y. Genomic analyses reveal evolutionary and geologic context for the plateau fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Clin. Med. 2020; 15: 107‒119. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z-Q, Lin S, Baker PJ, Wu L-F, Wang X-R, Wu H, Xu F, Wang H-Y, Brathwaite ME, Zheng Y-G. Transcriptome sequencing and analysis of the entomopathogenic fungus Hirsutella sinensis isolated from Ophiocordyceps sinensis. BMC Genomics. 2015; 16: 106‒123. [CrossRef]

- Lu H-L, St Leger RJ. Chapter Seven - Insect Immunity to Entomopathogenic Fungi, Editors: Lovett B, St. Leger RJ. Advanc Genet, Academic Press, 2016. Vol. 94; pp. 251-85.

- Mao X-M, Zhao S-M, Cao L, Yan X, Han R-C. The morphology observation of Ophiocordyceps sinensis from different origins. J. Environ. Entomol. 2013; 35(3): 343‒353.

- Meng Q, Yu H-Y, Zhang H, Zhu W, Wang M-L, Zhang J-H, Zhou G-L, Li X, Qin Q-L, Hu S-N, Zou Z. Transcriptomic insight into the immune defenses in the ghost moth, Hepialus xiaojinensis, during an Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungal infection. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015; 64: 1−15. [CrossRef]

- Mishra A, Forche A and Anderson MZ. Parasexuality of Candida Species. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021; 11:796929. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura N, Tanaka C, Takeuchi-Kaneko Y. Transmission of antibiotic-resistance markers by hyphal fusion suggests partial presence of parasexuality in the root endophytic fungus Glutinomyces brunneus. Mycol. Progress 2019; 18: 453–462. [CrossRef]

- Pfennig KS. Facultative Mate Choice Drives Adaptive Hybridization. Sci. 2007; 318: 965–967. [CrossRef]

- Peters C, Elofsson A. Why is the biological hydrophobicity scale more accurate than earlier experimental hydrophobicity scales? Proteins. 2014; 82(9): 2190-2198. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y, Wan D-G, Lu X-M, Guo J-L. The study of scientific name discussion for TCM Cordyceps. LisShenzhen Med. Material Medica Res. 2013; 24(9): 2211−2212.

- Samarasinghe H, You M, Jenkinson TS, Xu J-P, James TY. Hybridization Facilitates Adaptive Evolution in Two Major Fungal Pathogens. Genes. 2020; 11: 101. [CrossRef]

- Seervai RNH, Jones SK, Hirakawa MP, Porman AM, Bennett RJ. Parasexuality and ploidy change in Candida tropicalis. Eukaryotic Cell. 2013; 12(12): 1629–1640. [CrossRef]

- Sherwood RK, Bennett RJ. Fungal meiosis and parasexual reproduction--lessons from pathogenic yeast. Current Opinion Microbiol. 2009; 12(6): 599-607. [CrossRef]

- Shu R-H, Zhang J-H, Meng Q, Zhang H, Zhou G-L, Li M-M, Wu P-P, Zhao Y-N, Chen C, Qin Q-L. A new high-quality draft genome assembly of the Chinese cordyceps Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Genome Biol. Evol. 2020; 12(7): 1074−1079. [CrossRef]

- Simm S, Einloft J, Mirus O, Schleiff E. 50 years of amino acid hydrophobicity scales: revisiting the capacity for peptide classification. Biol. Res. 2016; 49(1): 31. [CrossRef]

- Steensels J, Gallone B, Verstrepen KJ. Interspecific hybridization as a driver of fungal evolution and Adaptation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021; 19: 485–500.

- Stensrud Ø, Hywel-Jones NL, Schumacher T. Towards a phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps: ITS nrDNA sequence data confirm divergent lineages and paraphyly. Mycol. Res. 2005; 109: 41−56. [CrossRef]

- Stensrud Ø, Schumacher T, Shalchian-Tabrizi K, Svegardenib IB, Kauserud H. Accelerated nrDNA evolution and profound AT bias in the medicinal fungus Cordyceps sinensis. Mycol. Res. 2007; 111: 409–415. DOI: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.01.015.

- Stone R. Improbable partners aim to bring biotechnology to a Himalayan kingdom. Sci. 2010; 327: 940–941. [CrossRef]

- Sung G-H, Hywel-Jones NL, Sung J-M, Luangsa-ard JJ, Shrestha B, Spatafora JW. Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2007; 57: 5−59. [CrossRef]

- Tunyasuvunakool, K., Adler, J., Wu, Z. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction for the human proteome. Nature 596, 590–596 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Turgeon BG, Yoder OC. Proposed nomenclature for mating type genes of filamentous ascomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000; 31: 1‒5. [CrossRef]

- Varadi M, Bertoni D, Magana P, Paramval U, Pidruchna I, Radhakrishnan M, Tsenkov M, Nair S, Mirdita M, Yeo J, Kovalevskiy O, Tunyasuvunakool K, Laydon A, Žídek A, Tomlinson H, Hariharan D, Abrahamson J, Green T, Jumper J, Birney E, Steinegger M, Hassabis D, Velankar S. AlphaFold Protein Structure Database in 2024: providing structure coverage for over 214 million protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024; 52(D1): D368-D375. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Stata M, Wang W, Stajich JE, White MM, Moncalvo JM. Comparative genomics reveals the core gene toolbox for the fungus-insect symbiosis. mBio. 2018; 9: e00636-18. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-B, Wang Y, Fan Q, Duan D-E, Zhang G-D,· Dai R-Q, Dai Y-D, Zeng W-B, Chen Z-H, Li D-D, Tang D-X, Xu Z-H, Sun T, Nguyen T-T, Tran N-L, Dao V-M, Zhang C-M, Huang L-D, Liu Y-J, Zhang X-M, Yang D-R, Sanjuan T, Liu X-Z, Yang Z-L, Yu H. Multigene phylogeny of the family Cordycipitaceae (Hypocreales): new taxa and the new systematic position of the Chinese cordycipitoid fungus Paecilomyces hepiali. Fungal Divers 2020; 103:1. [CrossRef]

- Wei J-C, Wei X-L, Zheng W-F, Guo W, Liu R-D. Species identification and component detection of Ophiocordyceps sinensis cultivated by modern industry. Mycosystema. 2016; 35(4): 404‒410.

- Wei X-L, Yin X-C, Guo Y-L, Shen N-Y, Wei, J.-C. Analyses of molecular systematics on Cordyceps sinensis and its related taxa. Mycosystema. 2006; 25(2): 192–202.

- Wilson AM, Wilken PM, van der Nest MA, Steenkamp ET, Wingfield MJ, Wingfield BD. Homothallism: an umbrella term for describing diverse sexual behaviours. IMA Fungus. 2015; 6(1): 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Xia E-H, Yang D-R, Jiang J-J, Zhang Q-J, Liu Y, Liu Y-L, Zhang Y, Zhang H-B, Shi C, Tong Y, Kim C-H, Chen H, Peng Y-Q, Yu Y, Zhang W, Eichler EE, Gao L-Z. The caterpillar fungus, Ophiocordyceps sinensis, genome provides insights into highland adaptation of fungal pathogenicity. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7: 1806. [CrossRef]

- Xia F, Liu Y, Shen G-L, Guo L-X, Zhou X-W. Investigation and analysis of microbiological communities in natural Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Can. J. Microbiol. 2015; 61: 104‒111. [CrossRef]

- Xiang L, Li Y, Zhu Y, Luo H, Li C, Xu X, Sun C, Song J-Y, Shi L-H, He L, Sun W, Chen S-L. Transcriptome analysis of the Ophiocordyceps sinensis fruiting body reveals putative genes involved in fruiting body development and cordycepin biosynthesis. Genomics. 2014; 103: 154−159. [CrossRef]

- Xiao W, Yang J-P, Zhu P, Cheng K-D, He H-X, Zhu H-X, Wang Q. Non-support of species complex hypothesis of Cordyceps sinensis by targeted rDNA-ITS sequence analysis. Mycosystema. 2009; 28(6): 724–730.

- Yang J-L, Xiao W, He H-X, Zhu H-X, Wang S-F, Cheng -KD, Zhu P. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Paecilomyces hepiali and Cordyceps sinensis. Acta Pharmaceut. Sinica 2008; 43(4): 421‒426.

- Yang J-Y, Tong X-X, He C-Y, Bai J, Wang F, Guo J-L. Comparison of endogenetic microbial community diversity between wild Cordyceps sinensis, artificial C. sinensis and habitat soil. Chin. J. Chin. Materia Medica. 2021; 46(12): 3106‒3115.

- Yao Y-S, Zhu J-S. Indiscriminate use of the Latin name for natural Cordyceps sinensis and Ophiocordyceps sinensis fungi. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med. 2016; 41(7): 1316–1366.

- Zhang S; Zhang Y-J. Molecular evolution of three protein-coding genes in the Chinese caterpillar fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Microbiol. China. 2015; 42(8): 1549−1560.

- Zhang S, Zhang Y-J, Liu X-Z, Wen H-A, Wang M, Liu D-S. Cloning and analysis of the MAT1-2-1 gene from the traditional Chinese medicinal fungus Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Fungal Biol. 2011; 115: 708−714.

- Zhang S, Zhang Y-J, Shrestha B, Xu J-P, Wang C-S, Liu X-Z. Ophiocordyceps sinensis and Cordyceps militaris: research advances, issues and perspectives. Mycosystema. 2013; 32: 577−597.

- Zhang S-W, Cen K, Liu Y, Zhou X-W, Wang C-S. Metatranscriptomics analysis of the fruiting caterpillar fungus collected from the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Sci. Sinica Vitae. 2018; 48(5): 562−570.

- Zhang Y-J, Li E-W, Wang C-S, Li Y-L, Liu X-Z. Ophiocordyceps sinensis, the flagship fungus of China: terminology, life strategy and ecology. Mycol. 2012; 3(1): 2–10. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21501203.2011.654354.

- Zhang Y-J, Sun B-D, Zhang S, Wàngmŭ, Liu X-Z, Gong W-F. Mycobiotal investigation of natural Ophiocordyceps sinensis based on culture-dependent investigation. Mycosistema. 2010; 29(4): 518–527.

- Zhang Y-J, Xu L-L, Zhang S, Liu X-Z, An Z-Q, Wàngmŭ, Guo Y-L. Genetic diversity of Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a medicinal fungus endemic to the Tibetan Plateau: implications for its evolution and conservation. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009; 9: 290. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y-J, Zhang S, Li Y-L, Ma S-L, Wang C-S, Xiang M-C, Liu X, An Z-Q, Xu J-P, Liu X-Z. Phylogeography and evolution of a fungal–insect association on the Tibetan Plateau. Mol. Ecol. 2014; 23: 5337−5355. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y-N, Zhang J-H, Meng Q, Zhang H, Zhou G-L, Li M-M, Wu P-P, Shu R-H, Gao X-X, Guo L, Tong Y, Cheng L-Q, Guo L, Chen C, Qin Q. Transcriptomic analysis of the orchestrated molecular mechanisms underlying fruiting body initiation in Chinese cordyceps. Gene. 2020; 763: 145061. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Wang, C.-S. Sexuality Control and Sex Evolution in Fungi. Sci. Sin. Vitae 2013, 43, 1090–1097.

- Zhong X, Gu L, Wang H-Z, Lian D-H, Zheng Y-M, Zhou S, Zhou W, Gu J, Zhang G, Liu X. Profile of Ophiocordyceps sinensis transcriptome and differentially expressed genes in three different mycelia, sclerotium and fruiting body developmental stages. Fungal Biol. 2018; 122: 943‒951. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-S, Gao L, Li X-H, Yao Y-S, Zhou Y-J, Zhao J-Q, Zhou Y-J. Maturational alterations of oppositely orientated rDNA and differential proliferations of CG:AT-biased genotypes of Cordyceps sinensis fungi and Paecilomyces hepiali in natural C. sinensis. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010; 2(3): 217–238. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-S, Guo Y-L, Yao Y-S, Zhou Y-J, Lu J-H, Qi Y, Chen W, Zheng T-Y, Zhang L, Wu Z-M, Zhang L-J, Liu X-J, Yin W-T. Maturation of Cordyceps sinensis associates with co-existence of Hirsutella sinensis and Paecilomyces hepiali DNA and dynamic changes in fungal competitive proliferation predominance and chemical profiles. J. Fungal Res. 2007; 5(4): 214–224.

- Zhu J-S, Gray GM. Renaturative catalytic blotting of enzyme proteins. Chapter 17. in Dunbar BS (ed.), Protein blotting: A practical approach (IRL series). Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994, pp. 221–238. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-S, Halpern GM, Jones K. The scientific rediscovery of a precious ancient Chinese herbal regimen: Cordyceps sinensis: Part I. J. Altern. Complem. Med. 1998a; 4(3): 289–303. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-S, Halpern GM, Jones K. The scientific rediscovery of an ancient Chinese herbal medicine: Cordyceps sinensis: Part II. J. Altern. Complem. Med. 1998b; 4(4): 429–457. [CrossRef]

- Zhu J-S, Li C-L, Tan N-Z, Berger JL, Prolla TA. Combined use of whole-gene expression profiling technology and mouse lifespan test in anti-aging herbal product study. Proc. 2011 New TCM Products Innovation and Industrial Development Summit, Hangzhou, China (Nov 27, 2011). pp. 443–448. https://xueshu.baidu.com/usercenter/paper/show?paperid=08341c17fa58c8f85584b92572b90f75&site=xueshu_se.

- Zhu J-S, Li Y-L. A Precious Transitional Chinese Medicine, Cordyceps sinensis: Multiple heterogeneous Ophiocordyceps sinensis in the insect-fungi complex. Lambert Academic Publishing, Saarbrüchen. Germany, 2017.

Figure 1.

The Bayesian majority rule consensus clustering tree was inferred via MrBayes v3.2.7 software for the 40 full-length and truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins of the H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The clusters and their branches (in blue) are shown alongside the tree. The AlphaFold UniProt codes for the 3D structures of the full-length proteins are shown in red alongside the tree for Branch 1 of the clusters, in pink for Branch 2, in purple for Branch 3, and in brown for Branch 4. The AlphaFold UniProt codes in green indicate the N-/C-terminally truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins.

Figure 1.

The Bayesian majority rule consensus clustering tree was inferred via MrBayes v3.2.7 software for the 40 full-length and truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins of the H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The clusters and their branches (in blue) are shown alongside the tree. The AlphaFold UniProt codes for the 3D structures of the full-length proteins are shown in red alongside the tree for Branch 1 of the clusters, in pink for Branch 2, in purple for Branch 3, and in brown for Branch 4. The AlphaFold UniProt codes in green indicate the N-/C-terminally truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins.

Figure 2.

The Bayesian majority rule consensus clustering tree was inferred via MrBayes v3.2.7 software for the 32 full-length and truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins of the H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The clusters and their branches (in blue) are shown alongside the tree. The AlphaFold UniProt codes for the 3D structures of the full-length proteins are shown in red alongside the tree for Branch 1 of the clusters and in pink for Branch 2 of the clusters. The AlphaFold UniProt codes in green indicate the C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins.

Figure 2.

The Bayesian majority rule consensus clustering tree was inferred via MrBayes v3.2.7 software for the 32 full-length and truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins of the H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The clusters and their branches (in blue) are shown alongside the tree. The AlphaFold UniProt codes for the 3D structures of the full-length proteins are shown in red alongside the tree for Branch 1 of the clusters and in pink for Branch 2 of the clusters. The AlphaFold UniProt codes in green indicate the C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins.

Figure 3.

Fifteen 3D structural morphs for the 118 full-length MAT1-1-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The UniProt codes in red are for Branch 1 of each cluster shown alongside the Bayesian tree in

Figure 1, those in pink are for Branch 2, those in purple are for Branch 3, and those in brown are for Branch 4. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 3.

Fifteen 3D structural morphs for the 118 full-length MAT1-1-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The UniProt codes in red are for Branch 1 of each cluster shown alongside the Bayesian tree in

Figure 1, those in pink are for Branch 2, those in purple are for Branch 3, and those in brown are for Branch 4. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 4.

The sequence distribution (Panel A) and the 9 diverse 3D structure morphs (Panels B−J) of the 20 N-/C-terminally truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 4.

The sequence distribution (Panel A) and the 9 diverse 3D structure morphs (Panels B−J) of the 20 N-/C-terminally truncated MAT1-1-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 5.

Seventeen 3D structural morphs for the full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The UniProt codes in red are for Branch 1 of each cluster shown in the Bayesian tree in

Figure 2, and those in pink are for Branch 2. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 5.

Seventeen 3D structural morphs for the full-length MAT1-2-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates. The UniProt codes in red are for Branch 1 of each cluster shown in the Bayesian tree in

Figure 2, and those in pink are for Branch 2. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 6.

The sequence distribution (Panel A) and 3D structures (Panels B−E) of 5 C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates belonging to 4 diverse 3D structural morphs. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 6.

The sequence distribution (Panel A) and 3D structures (Panels B−E) of 5 C-terminally truncated MAT1-2-1 proteins of H. sinensis strains and wild-type C. sinensis isolates belonging to 4 diverse 3D structural morphs. Model confidence:

very high (pLDDT > 90);

high (90 > pLDDT > 70);

low (70 > pLDDT > 50); very low (pLDDT < 50).

Figure 7.

Alignment of the full-length sequences of representative MAT1-1-1 proteins of 15 structural morphs and translated sequence segments of the corresponding genome and metatranscriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains and natural C. sinensis. The residues in green indicate conservative amino acid substitutions, and the residues in red indicate nonconservative amino acid substitutions. The hyphens indicate identical amino acid residues.

Figure 7.

Alignment of the full-length sequences of representative MAT1-1-1 proteins of 15 structural morphs and translated sequence segments of the corresponding genome and metatranscriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains and natural C. sinensis. The residues in green indicate conservative amino acid substitutions, and the residues in red indicate nonconservative amino acid substitutions. The hyphens indicate identical amino acid residues.

Figure 8.

Alignment of the full-length sequences of representative MAT1-2-1 proteins of 17 diverse 3D structural morphs and the translated segments of the corresponding genome, transcriptome and metatranscriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains and natural C. sinensis. The residues in green refer to conservative amino acid substitutions, and the residues in red indicate nonconservative amino acid substitutions. The hyphens indicate identical amino acid residues.

Figure 8.

Alignment of the full-length sequences of representative MAT1-2-1 proteins of 17 diverse 3D structural morphs and the translated segments of the corresponding genome, transcriptome and metatranscriptome assemblies of H. sinensis strains and natural C. sinensis. The residues in green refer to conservative amino acid substitutions, and the residues in red indicate nonconservative amino acid substitutions. The hyphens indicate identical amino acid residues.

Figure 9.

ExPASy ProtScale plots for the α-helices (Panel A), β-sheets (Panel B), β-turns (Panel C), and coils (Panel D) of the MAT1-1-1 proteins. Each panel contains 4 ProtScale plots for the 4 MAT1-1-1 proteins. The open boxes in blue in all ALH24945 plots indicate the N-terminal truncation region occurring in the MAT1-1-1 protein encoded by the metatranscriptome assembly GAGW01008880. The open boxes in red in all the ALH24945 plots indicate the C-terminal truncation region occurring in the genome assembly ANOV01017390. The open boxes in green in all the OSIN7648 plots, as well as in the corresponding region in all plots for the MAT1-1-1 protein ALH24945 for topology and waveform comparisons, indicate the midsequence truncation region occurring in the MAT1-1-1 protein encoded by the metatranscriptome assembly OSIN7648.

Figure 9.

ExPASy ProtScale plots for the α-helices (Panel A), β-sheets (Panel B), β-turns (Panel C), and coils (Panel D) of the MAT1-1-1 proteins. Each panel contains 4 ProtScale plots for the 4 MAT1-1-1 proteins. The open boxes in blue in all ALH24945 plots indicate the N-terminal truncation region occurring in the MAT1-1-1 protein encoded by the metatranscriptome assembly GAGW01008880. The open boxes in red in all the ALH24945 plots indicate the C-terminal truncation region occurring in the genome assembly ANOV01017390. The open boxes in green in all the OSIN7648 plots, as well as in the corresponding region in all plots for the MAT1-1-1 protein ALH24945 for topology and waveform comparisons, indicate the midsequence truncation region occurring in the MAT1-1-1 protein encoded by the metatranscriptome assembly OSIN7648.

Figure 10.

ExPASy ProtScale plots for the α-helices (Panel A), β-sheets (Panel B), β-turns (Panel C), and coils (Panel D) of the MAT1-2-1 proteins. Each panel contains 2 ProtScale plots. The open boxes in red in the ANOV01000063 plots in Panels A, C, and D for the α-helices, β-turns, and coils, as well as in the corresponding region in the AEH27625 plots for the authentic MAT1-2-1 protein for topology and waveform comparisons, indicate the variation region occurring in the genome assembly.

Figure 10.