Introduction

Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) is the principal method for determining the crystal structures. The high quality of the crystals allowed collection of single-crystal x-ray diffraction data of up to 0.83-angstrom resolution, leading to unambiguous solution and precise anisotropic refinement. Characteristics such as degree of interpenetration, arrangement of water guests, linker disorder, and uncommon topology were deciphered with atomic precision—aspects impossible to determine without single crystals. [

1] The first challenge for crystallographer in crystal structure determination is large cell dimension of reticular material, often, longer wavelengths or longer detector distances are required to clearly distinguish the diffraction peaks from compact reciprocal spaces and inhouse diffractometer cannot unveil structures that can only be measured at synchrotron. Void space in crystals is rarely observed before the discovery of reticular materials. The exponential growth of MOFs, ZIFs, and COFs in the past twenty years greatly promotes methods and instrumentations for observing framework-guest chemistry. MOFs development based on high crystallinity and the robustness get advantage by SXD for material characterization and regard applied material the well performing property verification. [

2,

3] The earliest attempt was based on glass capillaries to keep crystals in vacuum or specific gaseous environment. With this technique, the gas adsorption site in MOF-5 was first determined.[

4] Later, a liquid flow setup on crystal mounts was developed, which enabled the first direct observation of imine condensation reaction happening in the pore of a coordination polymer.[

5] Almost ten years ago, in situ gas crystallography was developed, which relies on a modified goniometer head (named “environmental gas cell”) with a glass cap over the crystal-mounting pin.[

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] Synchrotron radiation was initially attractive because of the high photon flux available; however, there are other useful characteristics. Most obvious among these is the ability to choose a wavelength from a wide spectrum. As shown above, increasing the experimental wavelength can improve a poorly diffracting crystal, but absorption also increases with wavelength, therefore access to a continuum X-ray source allows the experimenter to optimize their sample as well as their desired experiment. Crystals composed of low Z elements, such as organic compounds, will have negligible absorption and will diffract more strongly at longer wavelengths. Compounds containing high-Z elements will have appreciable absorption, and will benefit from the use of small crystals at shorter wavelengths.[

9]

Figure 1.

Possible mechanism of the crystal growth process for Cu-MOF-2 at crystal interface, involving the formation of Cu

2L

4 SBU and its fragmentation into CuL

2. Adapted from ref. [

11].

Figure 1.

Possible mechanism of the crystal growth process for Cu-MOF-2 at crystal interface, involving the formation of Cu

2L

4 SBU and its fragmentation into CuL

2. Adapted from ref. [

11].

Determine the impact of reaction conditions on the reticulation process and how to deconvolute each of these conditions help to understand their role in MOF crystal growth. Since the establishment of correlation between reaction rate and reactant concentration by Van’t Hoff, chemical kinetics studies played critical role in unraveling the mechanism of various chemical reactions. This classic tool is used in the study of MOF crystal growth as illustrated by Deng and co-workers in this issue of

Chem.[

12] A flow cell was designed to offer precise control of temperature and concentration of the reactants, providing solid basis for systematically examining the crystal formation kinetics. This allowed for the extraction of apparent reaction orders of metal ions and organic linkers separately. [

11]

The rational construction of highly heterogenous MOFs platforms, able to reach the complexity of biological systems from both a structural and functional viewpoint, is also achievable. [

3] Pore partition strategies have shown successful to obtain materials with enhanced functionalities respect the pristine MOFs [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Relevant to the topic, this approach has enabled to obtain different systems –constructed in one-pot reactions– with distinct organic and inorganic constituents [

17,

18,

19]. In this sense, Zhao et al. [

17] reported the construction of 23 multicomponent MOFs with a partitioned acs topology –pacs– [

20], where they use di- and trinuclear 1,2,4-triazolate (TRZ) based complexes as pore-partition agents [

17].

How Crystals Diffract

Braggs Law explain how the interaction between x ray and crystalline matter can take place. Using a wavelength comparable to reticules period and interatomic distance is possible obtain cell dimension and the structure of a measured material. nλ= 2d sinθ with n integer positive, λ x ray wavelength, d interplanar distance between crystallographic planes, θ the angle formed by a crystallographic plane and sample outgoing x ray radiation. On diffractogram spots are the sign of the electron density of atoms ordered and congruent with the geometric relation between radiation and matter. The position of diffraction peaks and on diffractogram provide information about the location of lattice planes in the crystal structure. Each peak measures a d-spacing that represents a family of lattice planes designed by the periodicity of atoms. Each peak also has an intensity which differs from other peaks in the pattern and reflects the relative strength of the diffraction proportional to the electrons of diffracting atoms. Scattering by an atom is essentially the scattering of the electron density displaced around the nucleus of the atom.

Structure Factor and densisty relation allows structure resolution by the electron density function defined at the point (x, y, z) in the unit cell.

With ρ(xyz) electron density, amplitudes, phases.

We can define

F(hkl) as the

structure factor for the (hkl) plane. In reciprocal space HKL are Miller Index that define where a crystallographic plane intersect crystallographic axes

a, b , c. Miller index are associated to each spot on diffractogram by indexing procedure in Rietveld refinement. A particular (hkl) plane is the result of reflections from a series of parallel atomic planes where

f1,

f2,

f3, etc. are the amplitudes of the respective atomic planes. The structure factor is the sum of the contribution of each ordered atom of the structure, developing the diffraction intensities from each of those elements and integrating the results into the total diffraction intensity from each designed plane in the structure, designed by interplanar distance dhkl. The

phase factors (

) are the repeat distances between the atomic planes measured from a common origin. [

21]

The data collection strategy should always match the crystal and the instrumentation. Physical analysis of the samples interprets the measured profile as the convolution of the sample dependent effects with the instrumentation contributions including the energy distribution of incident radiation and aberration due to geometry and optical components.

An excellent introduction to the topic is given by Dauter [

22]. In general, observed intensities are weaker at higher resolution and almost no crystal diffracts to the theoretical diffraction limit of d

max =λ/2. Some care must be taken in the determination of the effective maximum resolution of a dataset. There are at least five qualifiers describing the quality of a dataset: maximum resolution, completeness, multiplicity of observations (MoO, sometimes called redundancy), [

23] the average value of measured intensity divided by the estimated noise <I/σ> and a variety of merging residual values. The four latter qualifiers are usually given as a function of resolution, and most scientists give a pair of values for each qualifier: the average value for the complete dataset and the value for only the highest resolution shell. The value for I/σ should be as high as possible (at least 8–10 for the whole dataset), while the lower the merging R-factors are the better (most small molecule datasets should show Rint values of below 10% for the whole resolution range).[

24]

Reaction Monitoring at Synchrotron

Conventional diffractometer for single-crystal XRD experiments has been developed and optimized shortly after the first automated diffractometers became available in late 1960s. Crtystallographic publication started with

Arndt and Willis, 1966;

Busing and Levy, 1967.[

25] Since the very beginning of the automated diffractometry high-pressure crystallographers have strived to define optimal data collection and data reduction strategies geared towards retrieving highest-possible quality data from the SXD experiment. [

25]

Synchrotrons have made a remarkable contribution to many areas of science, most importantly, to life sciences, drug discovery, physics, chemistry, and material science. Synchrotron radiation is the electromagnetic radiation emitted when charged particles travel in curved paths. Because in most accelerators the particle trajectories are bent by magnetic fields, synchrotron radiation is also called Magneto-Bremsstrahlung. Due to multifaceted applications with evolving technologies and emerging new applications, it is safe to assume that we will soon have more fourth-generation synchrotronsthat will serve various areas of science for a long time.[

26] In Lund, Sweden, the first of a new generation of synchrotron LUCY [

27] radiation facilities based on the multibend achromat (MBA) was opened in 2016. This new innovation provides a way to control the trajectories of giga-electron-volt electrons to micrometre precision. The X-ray beam generated from such an improved `fourth generation' storage ring, measured at the experiment 50 m away, is largely spatially coherent because the angular width of the source, as seen from this distance, is exceedingly small – the same reason why starlight is spatially coherent. Basically, the difference between the distances of paths that rays take to reach the observer from one side of the source or the other is less than a wavelength, such that an optical instrument (including diffraction from the eponymous Young's double slit or its generalization to a macromolecular crystal) does not yield a result any different to that obtained with a single point emitter. Such can easily be the case when the Young's `slits' or scatterers are placed very close together. Indeed, the coherence of beams from a laboratory source was adequate for von Laue, Freidrich and Knipping to observe the first diffraction from zinc sulfide and for Rosalind Franklin to create Photograph 51 of the B-form of DNA. The new MBA sources fulfil this condition for scatterers placed at any spacing within the entire microradian extent of the beam (thereby dropping the need for periodicity in the sample). In some new source designs and for photon energies softer than about 10 keV, the entire beam is coherent – referred to as diffraction limited. This implies that the source itself is exceedingly bright. And it is brightness (or brilliance as some call it, the brightness of a source describes how much light it emits per second and unit area into each solid angle and over a particular bandwidth) that truly defines these sources and provides opportunities in all fields of research that synchrotrons cater to today. [

28]

The theoretical basis for synchrotron radiation traces back to the time of Thomson's discovery of the electron. In 1897, Larmor derived an expression from classical electrodynamics for the instantaneous total power radiated by an accelerated charged particle. The following year, Liénard extended this result to the case of a relativistic particle undergoing centripetal acceleration in a circular trajectory. Liénard's formula showed the radiated power to be proportional to (E/mc

2)

4/R

2, where E is particle energy, m is the rest mass, and R is the radius of the trajectory. A decade later in 1907, Schott reported his attempt to explain the discrete nature of atomic spectra by treating the motion of a relativistic electron in a homogeneous magnetic field. In so doing, he obtained expressions for the angular distribution of the radiation as a function of the harmonic of the orbital frequency.[

29]

brightness is seen to be proportional to the number of photons per second passing through a `coherence volume' of phase space (of position and momentum). One can strip away unwanted coherence modes by limiting the solid angle and area of the source that contributes to an experiment, such as by collimating the beam as Friedrich and Knipping first did, but it is a fundamental theorem of optics that one can never increase the number of rays per phase space volume. There are many ways to make things worse, but the source brightness dictates the upper limit on how quickly one can undertake a diffraction experiment, measure a spectrum, collect an image or tomogram, or expose a wafer. Brightness thus forms the basis of the comparison of sources, and the user meeting of every synchrotron radiation facility features one or more graphs of this quantity to boast the pre-eminence of their source or to justify the need for the next upgrade. What is astounding is the plot of the progression of the average brightness of sources since the discovery of X-rays by Röntgen in 1895. Not much happened until 1947 when synchrotron radiation was observed at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York [

30] . Since the late 1970s there has been a steady exponential growth that has brought 11 orders of magnitude increase in that time. This represents a doubling every 1.4 years, which can be compared with Moore's law of a doubling of the number of transistors on a chip about every 2 years. Sirius, at the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory, is currently under commissioning and the ESRF in France has completed its upgrade to its Extremely Brilliant Source (EBS), giving a 30 times increase in brightness [

31] . Other facilities such as the Advanced Photon Source and the Advanced Light Source in the USA, Spring8 in Japan, Diamond Light Source in the UK, and PETRA in Germany, are soon to follow, with even larger gains in brightness. [

28]

Diamond Light Source (DLS), the United Kingdom’s national synchrotron facility, is located on the campus of Rutherford Appleton Lab (RAL) in southern Oxfordshire. DLS is jointly funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC) within UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the Wellcome Trust. Designed as a successor to the ground-breaking Daresbury SRS, Diamond is a third-generation, 3 GeV light source. Construction began in 2003, with beamlines constructed in three phases: Phase I beamlines commenced user operation in 2007 [

32], [

https://cds.cern.ch/record/976575 ], with a further 15 Phase II beamlines completed in 2012. Phase III, completed in 2019, brought the total beamlines to 32. An additional thirty-third beamline, K11 DIAD, was scheduled at press time to start operating in 2020. Most synchrotrons worldwide are undergoing or exploring high-brightness, low-emittance upgrades. The fourth-generation, diffraction-limited storage ring plan for DLS is well underway. The Diamond-II Science Case and Conceptual Design Review proposed a machine lattice based on Double Triple Bend Achromats (DTBAs). This design yields an increase in brightness and coherence by a factor of up to 70 and provides mid-section straights so that existing bending magnet beamlines could use insertion devices. It is expected that there will be five extra straight sections available for new insertion device beamlines. The design increases the electron beam energy from 3.0 to 3.5 GeV, providing greatly increased photon flux at higher energies. The use of Cryogenic Permanent Magnet Undulator (CPMU) or Superconducting Undulator (SCU) insertion devices will give the potential for some instruments to operate at 40-45 keV. [

33]

Two different way of doing diffraction experiment can be conducted, in static measurements: where the variation of pressure or temperature variable is at equilibrium and the acquisition is faster then the variable changing; in dynamic measurements: for studying kinetics profile where the acquisition is slower than the variation of such parameters as temperature, pressure or insufflating of reagents.

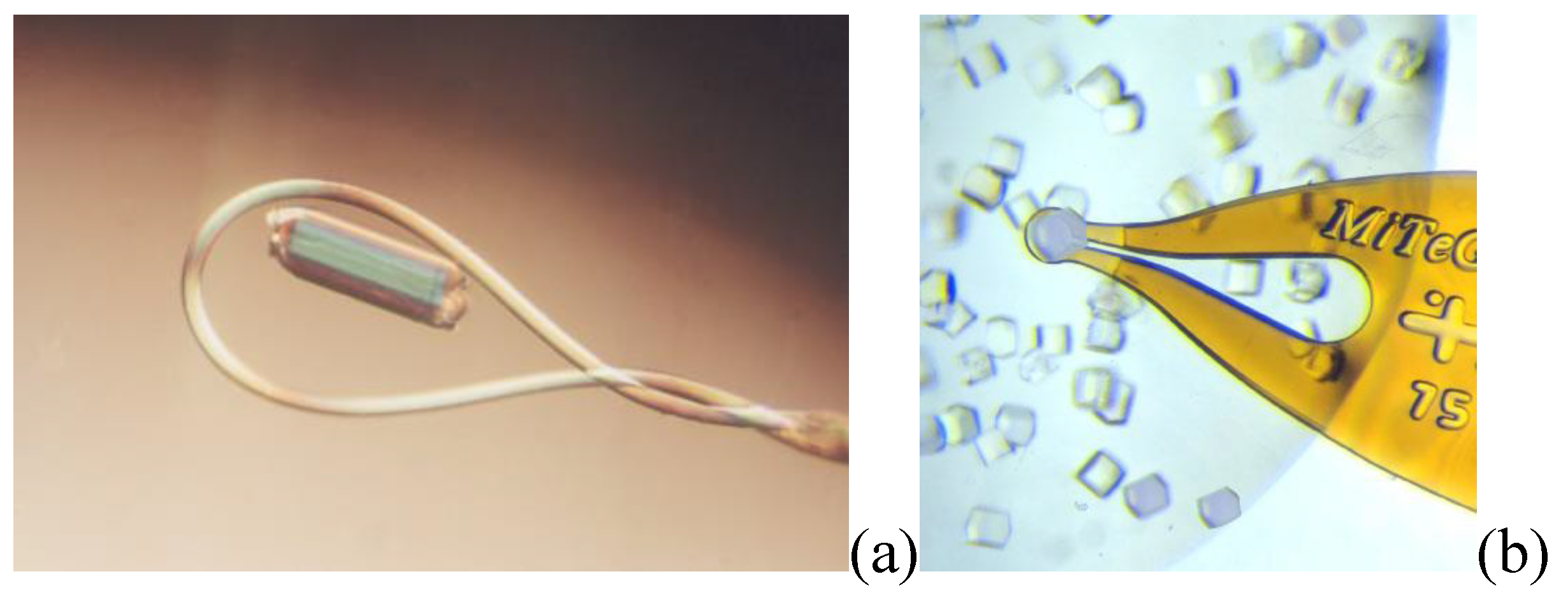

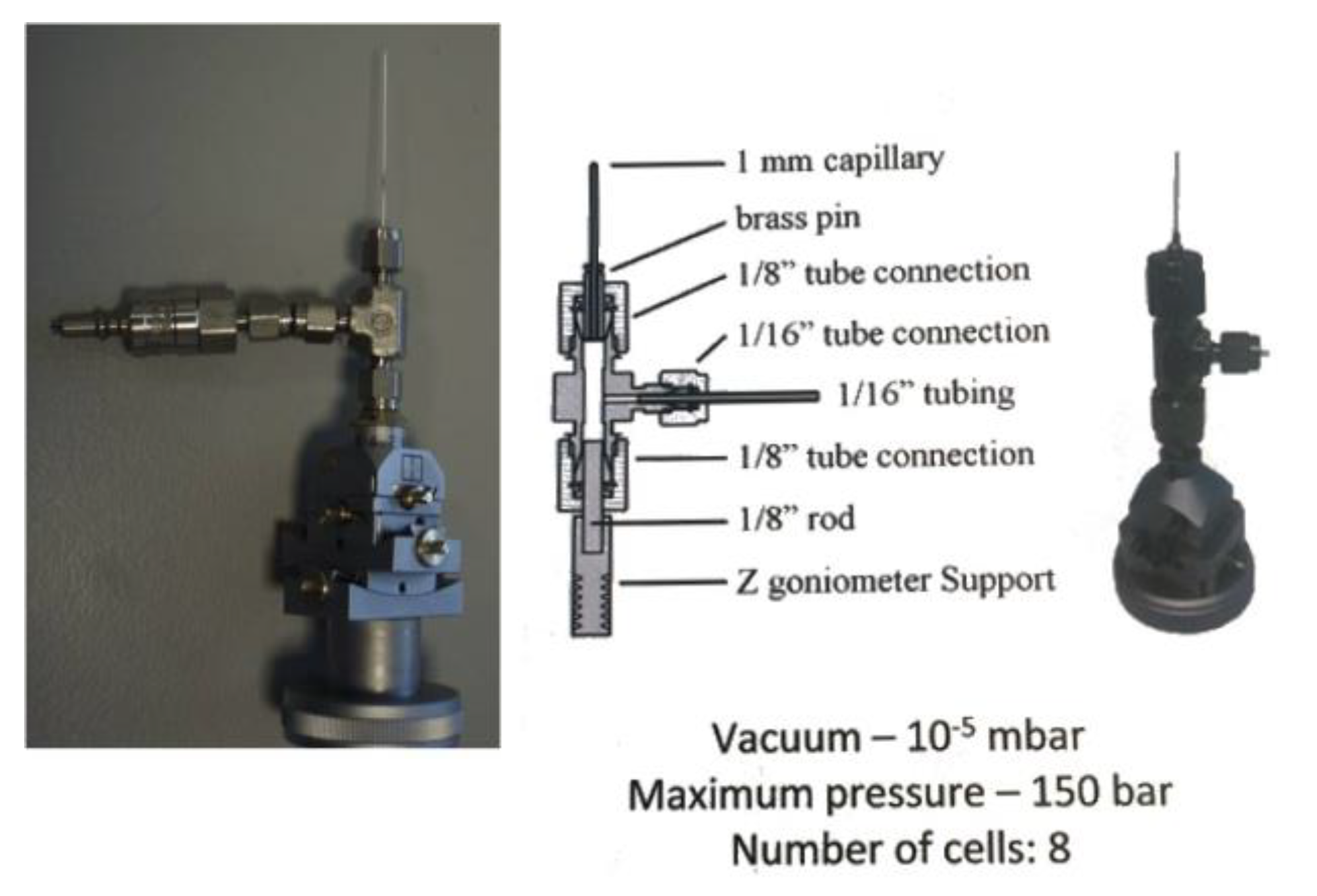

Holder for the reaction monitoring evolved in time to favours the contact between sample and reagents. From capillaries to gas flow cell the possibility to see how reaction take place allow the determining of intermediate states of reactions. Loop and MiTeGen holders are used for room temperature and nitrogen fluxed measurements. Flux gas cell, sample holder, is used at the beamline I19-EH2 that offers a variety of sample environment equipment allowing structural changes to be mapped under the influence of an external effect. The techniques include: variable temperature studies using open-flow and closed-cycle cryostats, and an open-flow furnace; variable pressure studies using diamond-anvil cells; gas exchange in porous materials; time-resolved studies of photo-excited states.

A very robust hemilabile histidine based MOF, measured thanks to the flux gas cell, allowed the adsorption and the snapshot capture of the diffraction image of the interactions between interacting gases as nitrogen carbon dioxide and propylene and as comparison the not interacting argon. X-ray analysis of a single crystal of the MOF under 7.5 bar of C

3H

6 at 290 K resulted in the {Cu

2[(S,S)-hismox]}·2 C

3H

6 crystal structure, a direct bond involving the unsaturated carbon−carbon bond of the C

3H

6 molecule and Cu(II) ions can be observed at 2.33 and 2.61 Å, for 7.5 bar/290 K and 1 bar/230 K, respectively. This is the shortest distance among these studied gases.[

34] During activation of the sample was observed the free of a coordinated water and a coordination environment rearrangement. Breathing phenomenon is observed heating the MOF by cell parameters variation, the singular flexible network, due to the presence of specific temperature- and adsorbate-responsive structural features, which can induce a reversible and continuous breathing of the MOF. Analysis of the structure at 110 K shows that the material crystallizes in the hexagonal space group P3

12

1 and has the unique

qtz-e-type topology. Noteworthy, the deformation of the framework during the breathing process is not accompanied by a crystalline phase transition. The dehydrated phases maintain symmetry and still exist in the P3

12

1 space group. The structural changes are most evident in the crystallographic

a and

c-axis directions showing strong contraction.

NO and CO, were introduced into activated Ni-CPO-27 and the related Co-4,6-dihydroxyisophthalate (Co-4,6-dhip). The Ni—C bond length is 2.16(3) Å, of the same order as that found for Co-CPO-27 at lower temperature [

8]. The unrestrained Co—N bond length was 1.972(10) Å. The NO binds in a bent geometry; again this was also seen with Ni-CPO-27 [

35,

36]

Transition-metal complexes exhibiting spin-crossover behaviour are another group of compounds that can produce a metastable ES species on photoactivation in the solid-state. Suitable d

4–d

7 coordination complexes display a thermal high-spin (HS)–low-spin (LS) transition on cooling below a critical temperature, Tc. Related to the LIESST studies (Light-Induced Excited Spin-State Trapping) are a series of photomagnetic studies performed on cyano-bridged heterobimetallic complexes using synchrotron X-ray single crystal and powder diffraction. In an initial study of [Nd(DMA)

4(H

2O)

4Fe(CN)

6]·3H

2O (DMA = dimethylacetamide) it was found that upon illumination of single crystals with UV light, at 15 K, an excited state was generated and significant structural changes were observed around the iron centres, with a general decrease in the Fe-ligand distances and an increase in some of the cyanide bond lengths [

37]. Subsequently, the series of heterobimetallic 4f/3d complexes [Ln(DMF)

4(H2O)

3(μ-CN)Fe(CN)

5]·H

2O (Ln = Y, Ce, Nd, Sm, Tb, Yb) and [Nd(DMF)

4(H2O)

3(μ-CN)Co(CN)

5]·H

2O were investigated using similar photocrystallographic techniques, also at 15 K [

38,

39]

The metastable or short-lived photoactivated states are described. The earliest photocrystallographic studies involving reversible molecular species used steady-state methods to show that photoactivation in transition-metal–nitrosyl complexes results in conversion to a new, metastable linkage isomer arrangement. From the subsequent single-crystal diffraction experiment it was apparent that a change in the nitrosyl coordination mode had been achieved, transforming from an (η

1-NO) GS arrangement to an isonitrosyl (η

1-ON) isomer with 47% photoconversion. This new linkage isomer was assigned as the MS1 state, in comparison with the previous spectroscopic results. The photoactivated crystal was then irradiated for a second time, now with 1064 nm laser light. Photoactivated linkage isomerism in the sulfur dioxide group was first reported by Johnson and Dew in 1979, from infra-red (IR) spectroscopic studies conducted on a solution sample of the complex [Ru(NH

3)

4Cl(SO

2)]Cl [

40]. reported the first photocrystallographic observation of an (η

1-OSO) isomer, induced in single-crystals of the complex [Ru(NH

3)

4(H

2O)(SO

2)][MeC

6H

4SO

3]

2.

Hatcher at all review the development of photocrystallography experiments against linkage isomer systems, from the early identification of metastable species under continuous illumination, through measuring kinetics at low temperature, to recent experiments studying species with sub-second lifetimes. Where Solid-state linkage isomers, where small-molecule ligands such as NO, NO

2−, N

2 and SO

2 show photo-induced changes in binding to a transition metal centre, have played a leading role in the development of dynamic SCXRD methodology, since the movement of whole atoms and the predictable temperature dependence of the excited-state lifetimes make them ideal test systems. [

42]

Reaction Monitoring by Conventional Diffractometer

Photo reduction of green brilliant is accomplished by Zn-based MOF, derived from the natural amino acid

L-serine, with formula {Zn

II2[(S,S)-serimox](H

2O)

2] · H

2O} (15) ((S,S)-serimox = [bis[(S)-serine]oxalyl diamide] . It crystallizes in the chiral P4

12

12 space group of the tetragonal system and consists of a chiral 3D pillared square grid where [Zn

II2(S,S)-serimox] moieties are located on the vertices of the edges. The robust uni-nodal three-connected srs nets are built up from trans oxamidato-bridged Zn(II) dimeric units, {Zn

II2[(S,S)-serimox]}, which are connected to each other through their carboxylate groups. In order to have a better characterization of 1, we performed UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, which revealed a strong adsorption band below 350 nm.The crystal structure of 15 was first determined at 100 K. The final material is capable of photodegrading brilliant green (BG) dye in only 120 min with an efficiency of 100% in the absence of any other oxidant or co-catalyst. In addition, the high robustness and crystallinity of 15 also allowed us to obtain the crystal structure of BG@15—with the help of SCXRD—after the photocatalytic process, which shows, unambiguously, the presence, within the channels, of CO

2 molecules resulting from the photodegradation of BG dyes. The photodegradation efficiency of 15 towards BG. Such efficiency was evaluated by measuring the decrease in the characteristic absorption bands of BG dye, which appear at 420 nm and 625 nm, respectively. Thus, under irradiation in the presence of 15, it a gradual decrease of both peaks with time can be observed, until the vanish completely after 120 min. [

43]

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are promising candidates for immobilization and stabilization of organic radicals because of the tunable spatial arrangement of organic linkers and metal nodes, which sequesters the reactive species. Herein, a flexible, redox-active tetracarboxylic acid linker bearing two imidazole units was chosen to construct a new Zr

6-MOF, NU-910, with

scu topology. Regulating the dynamics between a paramagnetic isolated radical species and a diamagnetic radical π-dimer species. This is accomplished by adjusting the distance between two adjacent linkers. From a characterization standpoint, the crystalline nature of MOFs enables direct observation of the structural changes in functional moieties by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis, which provides deeper insights into the structure–property relationship upon irradiation.[

44] To directly observe the modulation of an isolated radical and a π-dimer through structural tunability, we also inspected the structural changes of NU-910 after 20 min of irradiation with a 390 nm UV lamp. For the crystal from DEF solvent after irradiation, NU-910-DEF-i, a symmetry breaking is observed at 100 K . The space group changes from Cmmm to Pbam with very slight changes of the unit cell dimensions (a = 16.1453(14) Å, b = 25.6626(11), 24.5222(7) Å). The site symmetry of the BBI linker decreases from C

2h to Cs and is accompanied by a static disorder at two distinct positions. On the other hand, the site symmetry of the Zr6 cluster is reduced from D

2h to C

2h due to the loss of a mirror plane perpendicular to the

b-axis and breaks in the C-centered translation symmetry. NU-910 undergoes a structural contraction with the interlinker distance decreasing from 8.32 Å to 3.20 Å as the solvent changes from N,N-diethylformamide to acetone at 100 K. After irradiation, an increase of interlinker distance to 3.63 Å and a strong EPR signal from an isolated radical species are observed. As the temperature increases from 100 K to 225 K, the shorter interlinker distance of 3.19 Å in the closed pore form from acetone demonstrates a strong intermolecular interaction between adjacent radical linkers, while only a relatively weak signal from superoxide radical on the Zr6 node is detected in the EPR spectra. [

44]

Advertisement for Good Reporting Data

When a crystal structure is determined, the recorded intensities of each reflection is corrected for several factors to obtain the structure factor (Fobs) for each reflection. The crystal structure model is then refined against the experimentally obtained pattern by the method of least squares minimization between the observed and calculated structure factors (Fcalc). The relative error between them constitutes the crystallographic R-factor:

The optimal value must not be above 5% for a correct assignment of the electron density peaks.

Rint is a measure of the deviation of equivalent reflections in the chosen space group (e.g. the (200), (020), and (002) in a cubic structure): where Fobs2 (mean) is the average of the equivalent reflections in the assigned Laue class.§ Normally, the structure factors of all equivalent reflections should be identical. If the Rint value is high (e.g. 4 10%), this can be a sign of systematic error, often that the structure is assigned the wrong Laue class. This leads to reflections being erroneously classed as equivalent. As discussed later, twinning can often alter the reflections statistics, giving a different apparent Laue class. High Rint values are also often observed if the signal-to-noise level is low, due to a small and/or weakly diffracting crystal.

To report correct crystal structures, one needs to critically check the atomic displacement parameters (ADPs) and understand whether the structural information behind matches with the chemical information, which are important physical information in addition to chemical information such as bond length and bond angle. The reason is that although the idea of ADP started from thermal displacement of atoms, it is unable to distinguish disorders from thermal displacements. The recognised “rocking atom” in the crystallography textbooks is an example. As crystals are normally measured at 100 K, the vibrational and rotational states are frozen at the low temperature, resulting in Gaussian distributions of disordered positions and thus the electron density distribution. Common character is that the atomic ADP becomes larger as the atom gets further from the ligand metal coordination bond. In such cases, splitting the atoms into two positions is not a model representing its physical nature: it is suggested to leave the ADP as it is, and meanwhile, describing it in the refinement details embedded in CIF files. Correlated dynamic changes throughout the crystal mostly exist in compounds connected by strong bonds at least in one dimension. Molecular materials have weak interactions between the molecules inside crystals, which is not enough to drive correlated motions (the motion of one molecule propagates to the next one through strong interactions), or the formation of molecular crystals heavily relies on stacking that doesn’t contain enough space for motions.[

45] Reticular materials are formed by strong correlations (covalent/coordination bonds) that potentially allow such dynamics. Moreover, the void spaces leave freedom to the motions of structural units. As a result, many reticular materials can undergo large-scale motions while retaining order (i.e., crystallinity) throughout the structure. Proper handling of samples and data will reduce the need for using solvent masking software (

e.g. SQUEEZE) to obtain acceptable crystal structures subtracting disordered solvents molecules electron density in pores. [

46]

A twinned crystal is a sample which may appear to be a single crystal, but in reality, is an aggregate of two or more domains of identical crystalline phases in different orientations. It is a commonly encountered obstacle in the pursuit of correct structure determinations. The geometric relationship between the twin domains can be summarized by twin operations which transform the unit cell of the primary domain into those of the twin domains.

A crystal that is twinned by merohedry will produce a diffraction pattern with the symmetry of the combination of the space group and twin laws. The resulting pattern possess an apparently higher symmetry than the real crystal symmetry. Twinning can also arise from the flexible orientation of pseudosymmetric linkers. Illustrating examples are found among porous MOFs synthesized with planar, tetratopic linkers. Zr-based MOFs containing such linkers are abundant in the recent literature, and their diverse topologies are discussed in detail by Ma et al.[

47] Among these MOFs, the structure of NU-1100 (reported independently by two research groups) is an intriguing and complex case.[

48,

49] The MOF consists of 12-connected Zr-clusters and pyrene-based tetratopic linkers. Both reports discuss the structure in detail, and conclude that the linker can assume both orientations in the same crystal phase. The complexity of the structure determination of MOFs with rectangular planar linkers compared to those with square planar linkers is evident by comparing the R-factors of the closely related series of MOFs from NU-1101 to NU-1104. These structures are similar to that of NU-1100, but with more extended linkers. For highly porous MOFs,special attention should be paid to the following points:

(1) The value of |E2 - 1| deviates from its expected values.

(2) The apparent systematic absences are not consistent with any known space group.

(3) Although the data appear to be in order, the structure cannot be solved. In addition, twinning may in some cases be detected by visual inspection of the crystal morphology. If twinning is suspected, the most robust method for space group determination of the twinned structure is manual inspection using the tables supplied by Flack.[

50] When the correct space group is determined, the data can be treated accordingly using one of many available tools such as Platon/TwinRotMat46 (for the creation of sorted reflection files) or OLEX2[

51](for automatic derivation of twin laws). Twinning arising from pseudo-symmetry can be particularly difficult to describe. For a useful example described in detail, the reader is referred to the article by Guzei that illustrates to the practitioners of crystallography how to properly handle such cases and describes the logic and concrete steps necessary to account for the twinning, pseudo-symmetry and atomic positional disorder.[

52]