Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

18 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

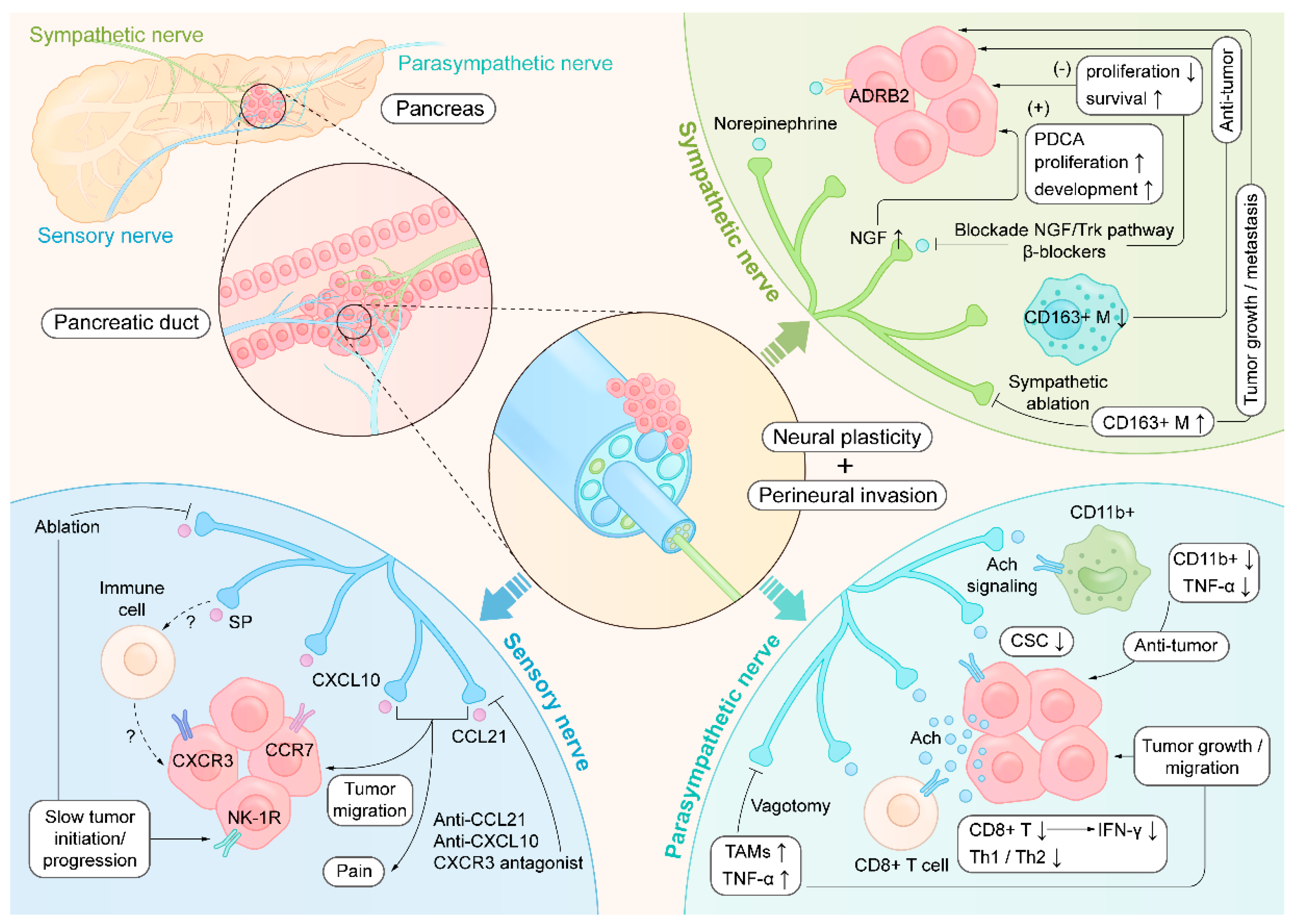

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a highly aggressive primary malignancy, and recent technological advances in surgery have opened up more possibilities for surgical treatment. Novel data show that diverse immune and neural components play essential roles in the aggressive behavior of PDAC. Recent studies have shown that neural invasion, neural plasticity, and altered innervation of autonomic nerve fibers are involved in pancreatic neuropathy in PDAC patients and have clarified the functional structure of the nerves innervating pancreatic draining lymph nodes. Notably, research on the pathogenesis and therapeutic options for treating PDAC from the viewpoint of interactions of the neuroimmune network is at the cutting edge. In this review, we present a special focus on neuroimmune interactions that highlight the current state of knowledge and future challenges concerning the reciprocal relationship between the immune system and nervous system in PDAC. Understanding the molecular events governing the pancreatic neuroimmune signaling axes will enhance our knowledge of physiology and may provide novel therapeutic targets for treating PDAC.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Neuroanatomy in the Pancreas and Draining Lymph Nodes

3. Neural Plasticity in PDAC

4. Neuroimmune Crosstalk in PDAC

4.1. Sympathetic Nerve

4.2. Parasympathetic Nerves

4.3. Sensory Nerves

5. Neuroimmune Regulation Intervention

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDAC | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| Ach | Acetylcholine |

| ADRB2 | Adrenoceptor beta 2 |

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-γ |

| SP | Substance P |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| NGF | Nerve growth factor |

| NK-1R | Neurokinin-1 receptor |

References

- Kamiya, A.; Hiyama, T.; Fujimura, A.; Yoshikawa, S. Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation in cancer: therapeutic implications. Clinical autonomic research : official journal of the Clinical Autonomic Research Society 2021, 31, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Hiraoka, N.; Ino, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Kishi, Y.; Nara, S.; Esaki, M.; Shimada, K.; Katai, H. Reduction of intrapancreatic neural density in cancer tissue predicts poorer outcome in pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Cancer science 2019, 110, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, K.; Ikeura, T.; Yanagawa, M.; Tomiyama, T.; Fukui, T.; Uchida, K.; Takaoka, M.; Nishio, A.; Uemura, Y.; Satoi, S.; et al. Morphological and immunohistochemical comparison of intrapancreatic nerves between chronic pancreatitis and type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP)... [et al.] 2017, 17, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundinger, T.O.; Mei, Q.; Foulis, A.K.; Fligner, C.L.; Hull, R.L.; Taborsky, G.J., Jr. Human Type 1 Diabetes Is Characterized by an Early, Marked, Sustained, and Islet-Selective Loss of Sympathetic Nerves. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2322–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.E.; Schorn, S.; Schremmer-Danninger, E.; Wang, K.; Kehl, T.; Giese, N.A.; Algül, H.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. Perineural mast cells are specifically enriched in pancreatic neuritis and neuropathic pain in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. PloS one 2013, 8, e60529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Fernandes, H.; Pachnis, V. Neuroimmune regulation during intestinal development and homeostasis. Nature immunology 2017, 18, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Tracey, K.J. Molecular and Functional Neuroscience in Immunity. Annual review of immunology 2018, 36, 783–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veiga-Fernandes, H.; Mucida, D. Neuro-Immune Interactions at Barrier Surfaces. Cell 2016, 165, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyot, M.; Simon, T.; Ceppo, F.; Panzolini, C.; Guyon, A.; Lavergne, J.; Murris, E.; Daoudlarian, D.; Brusini, R.; Zarif, H.; et al. Pancreatic nerve electrostimulation inhibits recent-onset autoimmune diabetes. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 1446–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, J.; Dominici, C.; Lucchesi, A.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Puget, A.; Hocine, M.; Rangel-Sosa, M.M.; Simic, M.; Nigri, J.; Guillaumond, F.; et al. Sympathetic axonal sprouting induces changes in macrophage populations and protects against pancreatic cancer. Nature communications 2022, 13, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.W.; Tao, L.Y.; Jiang, Y.S.; Yang, J.Y.; Huo, Y.M.; Liu, D.J.; Li, J.; Fu, X.L.; He, R.; Lin, C.; et al. Perineural Invasion Reprograms the Immune Microenvironment through Cholinergic Signaling in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renz, B.W.; Tanaka, T.; Sunagawa, M.; Takahashi, R.; Jiang, Z.; Macchini, M.; Dantes, Z.; Valenti, G.; White, R.A.; Middelhoff, M.A.; et al. Cholinergic Signaling via Muscarinic Receptors Directly and Indirectly Suppresses Pancreatic Tumorigenesis and Cancer Stemness. Cancer Discov 2018, 8, 1458–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, R.F.; Jimenez-Gonzalez, M.; Stanley, S.A. Unravelling innervation of pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, H.J.; Chiang, T.C.; Peng, S.J.; Chung, M.H.; Chou, Y.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Jeng, Y.M.; Tien, Y.W.; Tang, S.C. Human pancreatic afferent and efferent nerves: mapping and 3-D illustration of exocrine, endocrine, and adipose innervation. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 2019, 317, G694–g706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.C.; Baeyens, L.; Shen, C.N.; Peng, S.J.; Chien, H.J.; Scheel, D.W.; Chamberlain, C.E.; German, M.S. Human pancreatic neuro-insular network in health and fatty infiltration. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Diaz, R.; Abdulreda, M.H.; Formoso, A.L.; Gans, I.; Ricordi, C.; Berggren, P.O.; Caicedo, A. Innervation patterns of autonomic axons in the human endocrine pancreas. Cell metabolism 2011, 14, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Nicholls, P.K.; Claus, M.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Greene, W.K.; Ma, B. Immunofluorescence characterization of innervation and nerve-immune cell interactions in mouse lymph nodes. European journal of histochemistry : EJH 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Ziegler, C.G.K.; Austin, J.; Mannoun, N.; Vukovic, M.; Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Shalek, A.K.; von Andrian, U.H. Lymph nodes are innervated by a unique population of sensory neurons with immunomodulatory potential. Cell 2021, 184, 441–459e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felten, D.L.; Livnat, S.; Felten, S.Y.; Carlson, S.L.; Bellinger, D.L.; Yeh, P. Sympathetic innervation of lymph nodes in mice. Brain research bulletin 1984, 13, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleypool, C.G.J.; Mackaaij, C.; Lotgerink Bruinenberg, D.; Schurink, B.; Bleys, R. Sympathetic nerve distribution in human lymph nodes. Journal of anatomy 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bellinger, D.L.; Lorton, D. Autonomic regulation of cellular immune function. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical 2014, 182, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.E.; Friess, H.; Ceyhan, G.O. Neural plasticity in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015, 12, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyhan, G.O.; Demir, I.E.; Rauch, U.; Bergmann, F.; Müller, M.W.; Büchler, M.W.; Friess, H.; Schäfer, K.H. Pancreatic neuropathy results in “neural remodeling” and altered pancreatic innervation in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2009, 104, 2555–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyhan, G.O.; Bergmann, F.; Kadihasanoglu, M.; Altintas, B.; Demir, I.E.; Hinz, U.; Müller, M.W.; Giese, T.; Büchler, M.W.; Giese, N.A.; et al. Pancreatic neuropathy and neuropathic pain--a comprehensive pathomorphological study of 546 cases. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 177–186e171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stopczynski, R.E.; Normolle, D.P.; Hartman, D.J.; Ying, H.; DeBerry, J.J.; Bielefeldt, K.; Rhim, A.D.; DePinho, R.A.; Albers, K.M.; Davis, B.M. Neuroplastic changes occur early in the development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2014, 74, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho-Silva, C.; Cardoso, F.; Veiga-Fernandes, H. Neuro-Immune Cell Units: A New Paradigm in Physiology. Annual review of immunology 2019, 37, 19–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Rakoff-Nahoum, S.; Huang, S.; Riol-Blanco, L.; Barreiro, O.; von Andrian, U.H. The Regulation of Immunological Processes by Peripheral Neurons in Homeostasis and Disease. Trends in immunology 2015, 36, 578–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, D.P.; Jabangwe, C.; Lamghari, M.; Alves, C.J. The Neuroimmune Interplay in Joint Pain: The Role of Macrophages. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 812962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioussis, D.; Pachnis, V. Immune and nervous systems: more than just a superficial similarity? Immunity 2009, 31, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.; Pacheco, R.; Lluis, C.; Ahern, G.P.; O’Connell, P.J. The emergence of neurotransmitters as immune modulators. Trends in immunology 2007, 28, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stakenborg, N.; Labeeuw, E.; Gomez-Pinilla, P.J.; De Schepper, S.; Aerts, R.; Goverse, G.; Farro, G.; Appeltans, I.; Meroni, E.; Stakenborg, M.; et al. Preoperative administration of the 5-HT4 receptor agonist prucalopride reduces intestinal inflammation and shortens postoperative ileus via cholinergic enteric neurons. Gut 2019, 68, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrenis, K.; Gauthier, L.R.; Barroca, V.; Magnon, C. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor off-target effect on nerve outgrowth promotes prostate cancer development. International journal of cancer 2015, 136, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, P.A.; Koscsó, B.; Rajani, G.M.; Stevanovic, K.; Berres, M.L.; Hashimoto, D.; Mortha, A.; Leboeuf, M.; Li, X.M.; Mucida, D.; et al. Crosstalk between muscularis macrophages and enteric neurons regulates gastrointestinal motility. Cell 2014, 158, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, A.; Hayama, Y.; Kato, S.; Shimomura, A.; Shimomura, T.; Irie, K.; Kaneko, R.; Yanagawa, Y.; Kobayashi, K.; Ochiya, T. Genetic manipulation of autonomic nerve fiber innervation and activity and its effect on breast cancer progression. Nature neuroscience 2019, 22, 1289–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huan, H.B.; Wen, X.D.; Chen, X.J.; Wu, L.; Wu, L.L.; Zhang, L.; Yang, D.P.; Zhang, X.; Bie, P.; Qian, C.; et al. Sympathetic nervous system promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by modulating inflammation through activation of alpha1-adrenergic receptors of Kupffer cells. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2017, 59, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; Surana, R.; Valle, J.W.; Shroff, R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet (London, England) 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, Q.; Li, M.; Guo, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, F.; Tian, X.; Yang, Y. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic change in tumor microenvironment during pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma malignant progression. EBioMedicine 2021, 66, 103315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gola, M.; Sejda, A.; Godlewski, J.; Cieślak, M.; Starzyńska, A. Neural Component of the Tumor Microenvironment in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, H.M.; Saida, L.; de Koning, W.; Stubbs, A.P.; Li, Y.; Sideras, K.; Palacios, E.; Feliu, J.; Mendiola, M.; van Eijck, C.H.J.; et al. Spatial genomics reveals a high number and specific location of B cells in the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma microenvironment of long-term survivors. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 995715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosen, S.M.Z.; Uddin, M.N.; Xu, Z.; Buckley, B.J.; Perera, C.; Pang, T.C.Y.; Mekapogu, A.R.; Moni, M.A.; Notta, F.; Gallinger, S.; et al. Metastatic phenotype and immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Key role of the urokinase plasminogen activator (PLAU). Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 1060957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Du, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C. Tumor microenvironment and metabolic remodeling in gemcitabine-based chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer. Cancer letters 2021, 521, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, R.; Ijichi, H.; Fujishiro, M. The Role of Neural Signaling in the Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Sivakumar, S.; Bednarsch, J.; Wiltberger, G.; Kather, J.N.; Niehues, J.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; Valkenburg-van Iersel, L.; Kintsler, S.; Roeth, A.; et al. Nerve fibers in the tumor microenvironment in neurotropic cancer-pancreatic cancer and cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene 2021, 40, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloman, J.L.; Albers, K.M.; Li, D.; Hartman, D.J.; Crawford, H.C.; Muha, E.A.; Rhim, A.D.; Davis, B.M. Ablation of sensory neurons in a genetic model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma slows initiation and progression of cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 3078–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banh, R.S.; Biancur, D.E.; Yamamoto, K.; Sohn, A.S.W.; Walters, B.; Kuljanin, M.; Gikandi, A.; Wang, H.; Mancias, J.D.; Schneider, R.J.; et al. Neurons Release Serine to Support mRNA Translation in Pancreatic Cancer. Cell 2020, 183, 1202–1218e1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principe, D.R.; Korc, M.; Kamath, S.D.; Munshi, H.G.; Rana, A. Trials and tribulations of pancreatic cancer immunotherapy. Cancer letters 2021, 504, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, C.; Phillips, J.A.; Djamgoz, M.B.A. Nerve input to tumours: Pathophysiological consequences of a dynamic relationship. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Reviews on cancer 2020, 1874, 188411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renz, B.W.; Takahashi, R.; Tanaka, T.; Macchini, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Dantes, Z.; Maurer, H.C.; Chen, X.; Jiang, Z.; Westphalen, C.B.; et al. β2 Adrenergic-Neurotrophin Feedforward Loop Promotes Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 75–90e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucsek, M.J.; Qiao, G.; MacDonald, C.R.; Giridharan, T.; Evans, L.; Niedzwecki, B.; Liu, H.; Kokolus, K.M.; Eng, J.W.; Messmer, M.N.; et al. β-Adrenergic Signaling in Mice Housed at Standard Temperatures Suppresses an Effector Phenotype in CD8(+) T Cells and Undermines Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cancer research 2017, 77, 5639–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partecke, L.I.; Käding, A.; Trung, D.N.; Diedrich, S.; Sendler, M.; Weiss, F.; Kühn, J.P.; Mayerle, J.; Beyer, K.; von Bernstorff, W.; et al. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy promotes tumor growth and reduces survival via TNFα in a murine pancreatic cancer model. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 22501–22512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirth, M.; Gandla, J.; Höper, C.; Gaida, M.M.; Agarwal, N.; Simonetti, M.; Demir, A.; Xie, Y.; Weiss, C.; Michalski, C.W.; et al. CXCL10 and CCL21 Promote Migration of Pancreatic Cancer Cells Toward Sensory Neurons and Neural Remodeling in Tumors in Mice, Associated With Pain in Patients. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 665–681.e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.E.; Boldis, A.; Pfitzinger, P.L.; Teller, S.; Brunner, E.; Klose, N.; Kehl, T.; Maak, M.; Lesina, M.; Laschinger, M.; et al. Investigation of Schwann cells at neoplastic cell sites before the onset of cancer invasion. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2014, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborde, S.; Gusain, L.; Powers, A.; Marcadis, A.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Frants, A.; Kao, E.; Tang, L.H.; Vakiani, E.; et al. Reprogrammed Schwann cells organize into dynamic tracks that promote pancreatic cancer invasion. Cancer discovery 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Z.; Ou, G.; Su, M.; Li, R.; Pan, L.; Lin, X.; Zou, J.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; et al. TIMP1 derived from pancreatic cancer cells stimulates Schwann cells and promotes the occurrence of perineural invasion. Cancer letters 2022, 546, 215863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolato, B.; Hyphantis, T.N.; Valpione, S.; Perini, G.; Maes, M.; Morris, G.; Kubera, M.; Köhler, C.A.; Fernandes, B.S.; Stubbs, B.; et al. Depression in cancer: The many biobehavioral pathways driving tumor progression. Cancer treatment reviews 2017, 52, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, N.D.; Tarr, A.J.; Sheridan, J.F. Psychosocial stress and inflammation in cancer. Brain, behavior, and immunity 2013, 30 Suppl, S41-47. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B.L.; Thornton, L.M.; Shapiro, C.L.; Farrar, W.B.; Mundy, B.L.; Yang, H.C.; Carson, W.E., 3rd. Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2010, 16, 3270–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Hackert, T.; Strobel, O.; Büchler, M.W. Technical advances in surgery for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 2021, 108, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsey, J.; Ferson, P.F.; Keenan, R.J.; Julian, T.B.; Landreneau, R.J. Thoracoscopic pancreatic denervation for pain control in irresectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 1993, 80, 1051–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udumyan, R.; Montgomery, S.; Fang, F.; Almroth, H.; Valdimarsdottir, U.; Ekbom, A.; Smedby, K.E.; Fall, K. Beta-Blocker Drug Use and Survival among Patients with Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 3700–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, Z.; Ouyang, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Tumor microenvironment adrenergic nerves blockade liposomes for cancer therapy. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 2022, 351, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhmutova, M.; Caicedo, A. Optical Imaging of Pancreatic Innervation. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021, 12, 663022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, I.; Wang, H.P. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided celiac plexus block and neurolysis. Digestive endoscopy : official journal of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society 2017, 29, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, C.K.; Mathew-Steiner, S.S.; Das, A.; Sundaresan, V.B.; Roy, S. Electroceutical Management of Bacterial Biofilms and Surgical Infection. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2020, 33, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadi, K.B.; Srinivasan, S.S.; Traverso, G. Electroceuticals in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2020, 41, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, F.A.; Chavan, S.S.; Miljko, S.; Grazio, S.; Sokolovic, S.; Schuurman, P.R.; Mehta, A.D.; Levine, Y.A.; Faltys, M.; Zitnik, R.; et al. Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cytokine production and attenuates disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2016, 113, 8284–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmutova, M.; Rodriguez-Diaz, R.; Caicedo, A. A Nervous Breakdown that May Stop Autoimmune Diabetes. Cell metabolism 2020, 31, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.L.; Czepielewski, R.S.; Randolph, G.J. Sensory Nerves Regulate Transcriptional Dynamics of Lymph Node Cells. Trends in immunology 2021, 42, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).