Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

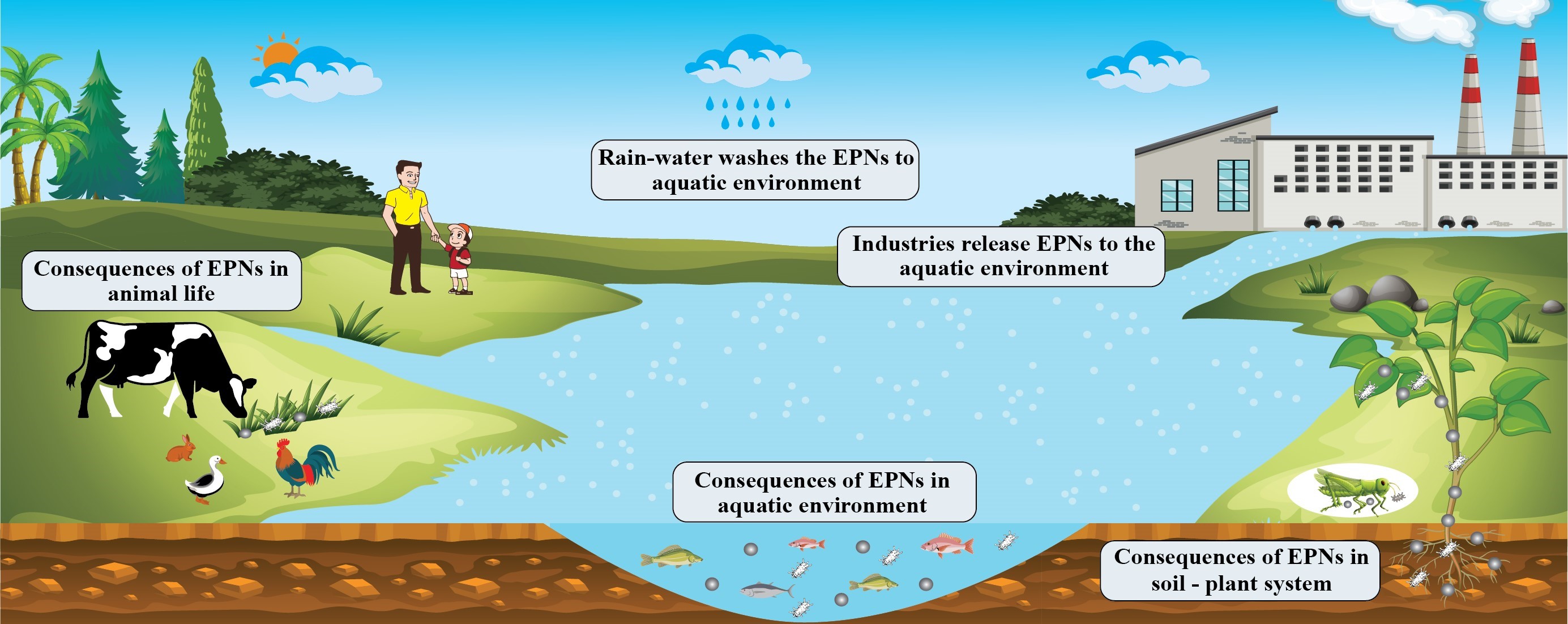

1. Introduction

2. ENPs in Aquatic Environment

2.1. ENP Interactions with Aquatic Organisms

2.2. Behavior and Fate of ENPs in the Aquatic Environment

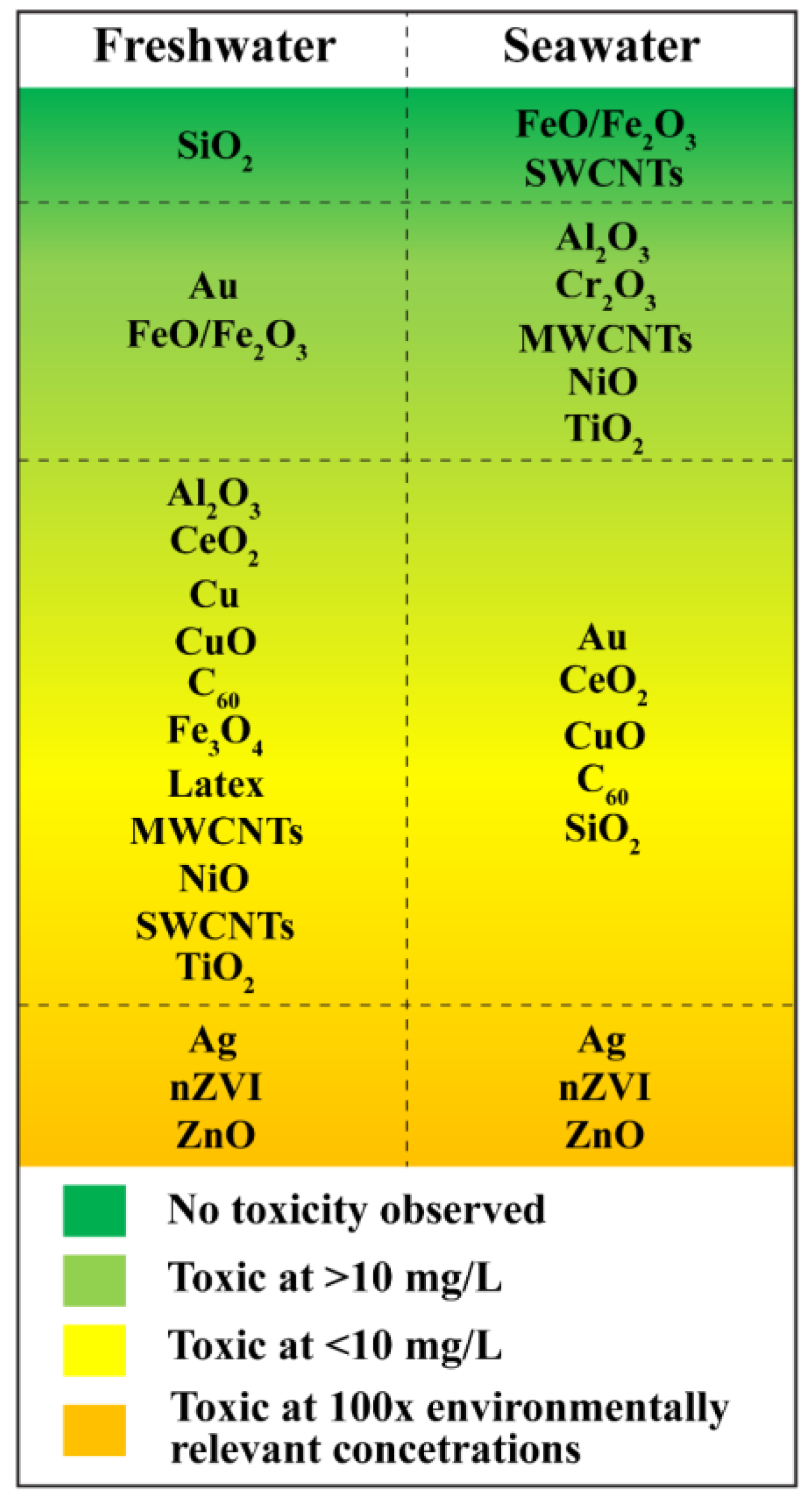

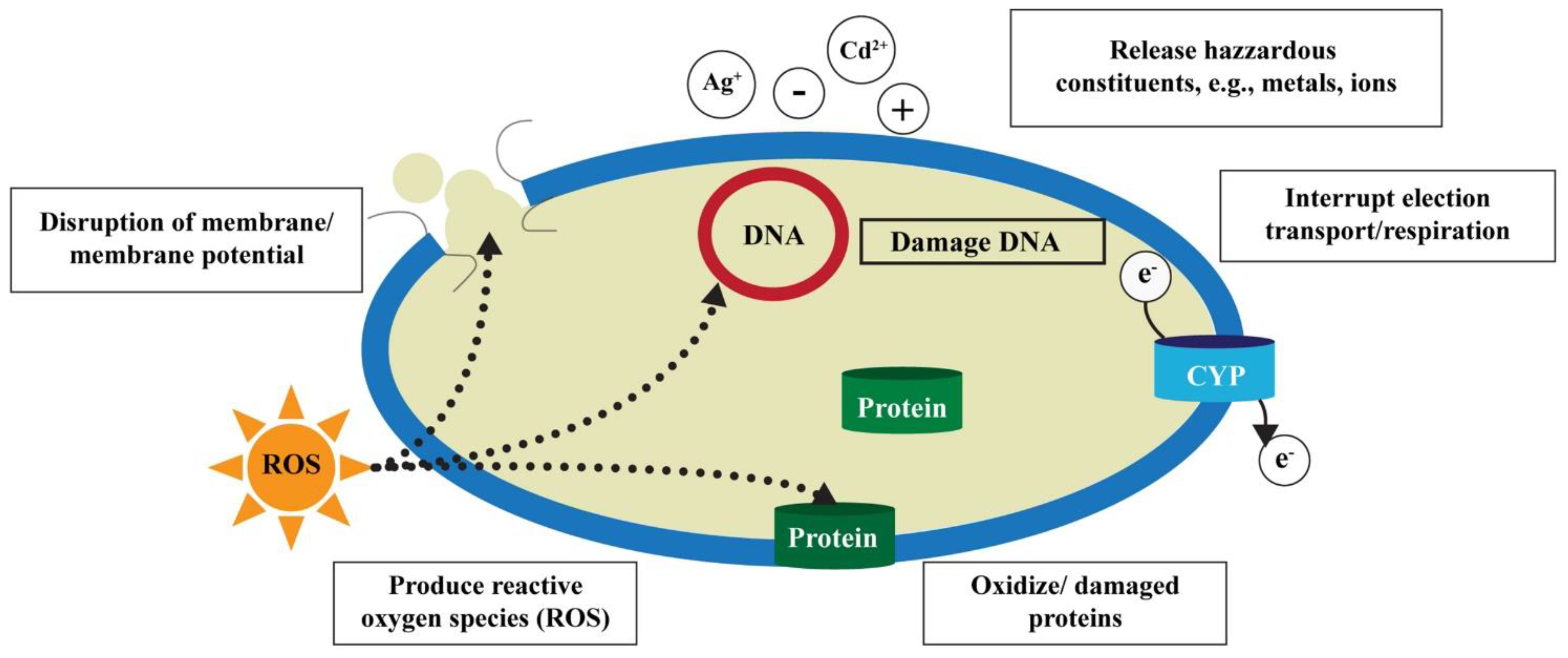

2.3. Toxicological Effects of ENPs in Aquatic Environment

2.3.1. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Microbes and Algae

2.3.2. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Aquatic Vertebrates

2.3.3. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Aquatic Invertebrates

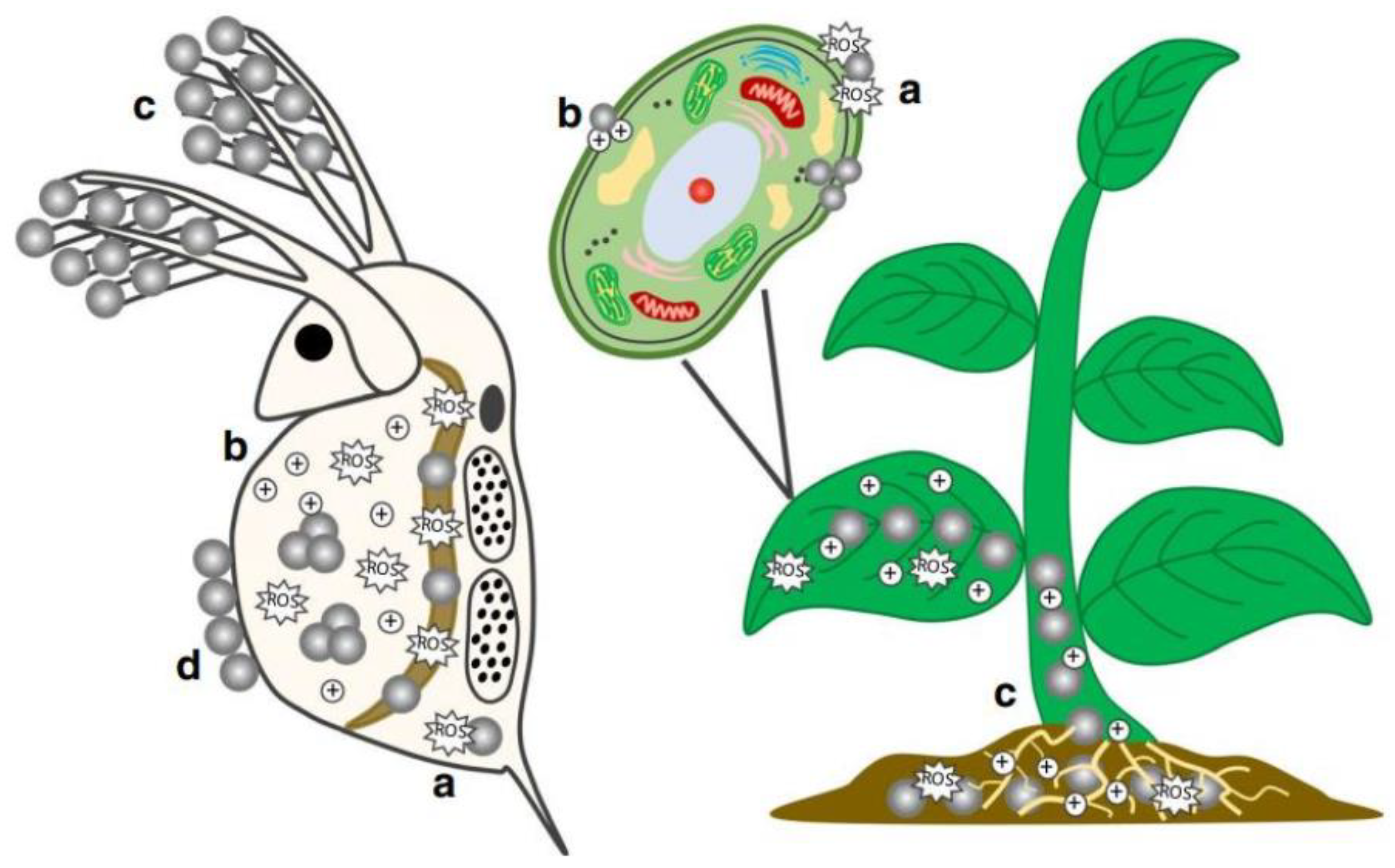

3. ENPs in Soil-Plant System

3.1. Interactions of ENPs with Soil-Plant Systems

3.2. Toxicological Effects of ENPs in Soil-Plant

3.3. Toxic Effects of ENPs on Plants Growth

4. Future Outlook to Address the Impacts of ENPs

- Reuse and recycle: Promoting the reuse and recycling of ENPs is vital for reducing resource wastage and environmental contamination. Unlike bulk materials, nano waste recycling is still a relatively new concept, with limited implementation in industrial and municipal waste management systems, where disposal often involves landfills or incineration. Developing efficient recovery techniques from industrial, agricultural, and wastewater sources, alongside designing ENPs for easier reuse, can advance sustainable practices. Establishing innovative recycling processes and integrating best practices into waste management systems can help recover ENPs for reuse in the same or diverse applications, promoting a circular and environmentally responsible approach to their management. Additionally, designing ENPs for easier recovery and reuse should be a priority for researchers and manufacturers. Several methods for reuse, recycling, and disposal have been described by Pandey et al. [86]. Those methods can be considered.

- Development of disposal management strategies: Effective waste management strategies for ENPs are essential to reduce their environmental and health impacts. Nano wastes, originating from industrial, residential, and medical sources, contribute to pollution and bioavailability concerns. Current waste management systems face challenges in addressing the rising volume of nano waste. Advanced filtration, adsorption, and containment technologies, along with specialized disposal methods, can prevent ENP leaching into aquatic environments, soil-plant systems, and water sources. Establishing dedicated facilities for ENP waste treatment while assessing the environmental implications of novel materials will further mitigate risks to ecosystems and human health.

- Implementation of regulatory policy: Globally harmonized regulatory policies are essential to ensure the responsible production, application, and disposal of ENPs. Such policies should enforce stricter disposal standards, encourage sustainable practices, and incentivize research into safer alternatives. Equally important are public awareness campaigns and transparent communication about the risks and benefits of ENPs to enable informed decision-making by industries, consumers, and policymakers. Collaborative efforts among governments, industries, researchers, and stakeholders can bridge gaps between policy and practice, while social awareness programs can highlight ENP impacts on ecosystems, fostering safer and more sustainable nanotechnology practices.

- Understanding toxicity and transmission by further research: A deeper understanding of the toxicity and environmental transmission of ENPs is essential to address their impact on aquatic environments and soil-plant systems. Although current studies rely heavily on modeling and concentration predictions, more comprehensive research is needed to evaluate the real-world effects of ENPs, particularly in relation to their transformation, aggregation, and degradation. Toxicity mechanisms, especially for nanoparticles like Ag-NPs, remain unclear, highlighting the need for thorough risk assessments before their widespread use. Developing high-precision analytical methods and real-time monitoring systems that integrate nanotechnology and digital tools is crucial to detect and quantify ENPs in environmental matrices. Future research should also prioritize the development of environmentally friendly, biodegradable ENPs through green synthesis methods, ensuring their reduced ecological impact and enhancing their sustainability from production to disposal.

- Risk assessment for ENP life cycle: As the deposition and accumulation of metal and metallic oxide ENPs in soils increase over time, their effects on soil properties, such as pH, electrical conductivity, and soil organic matter, become more significant. ENPs can compact soil particles, altering their rigidity and interacting with nutrients, potentially forming complexes that modify nutrient availability. While the benefits of ENPs in agricultural systems are being explored, research into their potential risks, especially their impact on soil health and microbial communities, is still in its early stages. Future studies should not only focus on the advantages of ENPs in agriculture but also evaluate their long-term effects on soil quality, plant growth, and microbial ecosystems. To better understand these impacts, developing robust risk assessment models that consider the life cycle, bioavailability, and cumulative effects of ENPs is essential. These frameworks should address ENPs’ unique properties, transformation behaviors, and their long-term risks to ecosystems.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Al2O3 | Aluminum oxide |

| ENP | Engineered nanoparticles |

| HA | Humic acids |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| TiO2 | Titanium oxide |

| ZnO | Zinc oxide |

References

- Suazo-Hernández, J.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Mlih, R.; Cáceres-Jensen, L.; Bolan, N.; Mora, M.D.L.L. Impact on some soil physical and chemical properties caused by metal and metallic oxide engineered nanoparticles: A review. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Li, K.; Chen, Y. Behavior and potential impacts of metal-based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic environments. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M.; Srivastav, A.; Gandhi, S.; Rao, S.; Roychoudhury, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.D. Monitoring of engineered nanoparticles in soil-plant system: A review. Environ. Nanotechnol. Monit. Manag. 2019, 11, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ullah, H.; Ali, M.U.; Ok, Y.S.; Rinklebe, J. Environmental transformation and nano-toxicity of engineered nano-particles (ENPs) in aquatic and terrestrial organisms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 3389, 2523–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastrana-Pastrana, Á.J.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Solanilla-Duque, J.F.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. . Plant proteins, insects, edible mushrooms and algae: more sustainable alternatives to conventional animal protein. J. of Future Foods 2025, 5, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomte, S.S.; Jadhav, P.V.; Prasath, V.R., N. J.; Agnihotri, T.G.; Jain, A. From lab to ecosystem: Understanding the ecological footprints of engineered nanoparticles. J. of Environ Sci. and Health, Part C 2023, 42, 33–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagariya, M.; Ghosh, A.; Pratihar, S. Life Cycle Risk Assessment and Fate of the Nanomaterials: An environmental safety perspective. In Occurrence, Distribution and Toxic Effects of Emerging Contaminants; Shanker, U., Rani, M., Eds.; CRC Press, 2024; pp. 201–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewicz, A.; Rasulev, B.; Dinadayalane, T.C.; Urbaszek, P.; Puzyn, T.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. Advancing risk assessment of engineered nanomaterials: application of computational approaches. Advanced Drug Delivery Rev. 2012, 64, 1663–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gautam, P.K.; Verma, A.; Singh, V.; Shivapriya, P.M.; Shivalkar, S.; et al. Green synthesis of metallic nanomaterials as effective alternatives to treat antibiotics resistant bacterial infections: A review. Biotechnol Rep. 2020, 25, e00427. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Yang, J.; Kwon, S.G.; Hyeon, T. Nonclassical nucleation and growth of inorganic nanomaterials. Nat. Rev. Materials 2016, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, F.; Lassen, C.; Kjoelholt, J.; Christensen, F.; Nowack, B. Modeling flows and concentrations of nine engineered nanomaterials in the Danish environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2015, 12, 5581–5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Desai, F.; Asmatulu, E. Engineered nanomaterials in the environment: bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and biotransformation. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amenta, V.; Aschberger, K.; Arena, M.; Bouwmeester, H.; Moniz, F.B.; Brandhoff, P.; et al. Regulatory aspects of nanotechnology in the agri/feed/food sector in EU and non-EU countries. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2015, 73, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, Q.; Liu, G.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Ullah, H.; Ahmed, R. Effects of biochar on uptake, acquisition and translocation of silver nanoparticles in rice (Oryza sativa L.) in relation to growth, photosynthetic traits and nutrients displacement. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, D.; Aziz, A.; AbdelRahman, M.A.E.; Mustafa, A.A.W.; Scopa, A.; Radice, R.P.; Drosos, M.; Moursy, A.R. Nanoecology: Exploring engineered nanoparticles’ impact on soil ecosystem health and biodiversity. Egyptian J. of Soil Sci. 2024, 64, 1637–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, S.; Sharma, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Zhou, P.; Mandal, J.; Srivastava, P.; et al. The distribution, fate, and environmental impacts of food additive nanomaterials in soil and aquatic ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 170013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwirn, K.; Voelker, D.; Galert, W.; Quik, J.; Tietjen, L. Environmental risk assessment of nanomaterials in the light of new obligations under the REACH regulation: which challenges remain and how to approach them? Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2020, 16, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Dubey, S.P.; Sillanpää, M.; Kwon, Y.N.; Lee, C.; Varma, R.S. Fate of engineered nanoparticles: Implications in the environment. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 287, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Report of the Committee on Proposal Evaluation for Allocation of Supercomputing Time for the Study of Molecular Dynamics: Third Round; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Akter, M.; Sikder, M.T.; Rahman, M.M.; Ullah, A.; Hossain, K.F.B.; Banik, S.; Hosokawa, T.; Saito, T.; Kurasaki, M. A systematic review on silver nanoparticles-induced cytotoxicity: Physicochemical properties and perspectives. J. Adv. Res. 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.C.; Xiao, B.D.; Fang, T. Chemical transformation of silver nanoparticles in aquatic environments: Mechanism, morphology, and toxicity. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joonas, E.; Aruoja, V.; Olli, K.; Kahru, A. Environmental safety data on CuO and TiO2 nanoparticles for multiple algal species in natural water: Filling the data gaps for risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 647, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead, J.R.; Batley, G.E.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Croteau, M.N.; Handy, R.D.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Judy, J.D.; Schirmer, K. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects – An updated review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2018, 37, 2029–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaveykova, V.I.; Li, M.; Worms, I.A.; Liu, W. When environmental chemistry meets ecotoxicology: Bioavailability of inorganic nanoparticles to phytoplankton. Chimia 2020, 74, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.A.; Lazareva, A. ; Predicted releases of engineered nanomaterials: from global to regional to local. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2013, 1, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuverza-Mena, N.; Martínez-Fernandez, D.; Du, W.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Bonilla-Bird, N. Lopez-Moreno, M.L.; Komarek, M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Exposure of engineered nanomaterials to plants: Insights into the physiological and biochemical responses: A review. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 236–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, G.V.; Gregory, K.B.; Apte, S.C.; Lead, J.R. Transformations of nanomaterials in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 6893–6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohlot, M.; Khurana, S.M.P.; Das, S.; Debnath, N. Fate of engineered nanomaterials in soil and aquatic systems. In Green Nanobiotechnology; Thakur, A., Thakur, P., Suhag, D., Khurana, S.M.P., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL 33431, USA, 2025; pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, K.; Herth, S. Plant nanotoxicology. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hund-Rinke, K.; Simon, M. Ecotoxic effect of photocatalytic active nanoparticles (TiO2) on algae and daphnids. Env. Sci. Poll. Res. Int. 2006, 13, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.N. Do nanoparticles present ecotoxicological risks for the health of the aquatic environment? Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delay, M.; Frimmel, F.H. Nanoparticles in aquatic systems. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012, 402, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B.; Ranville, J.F.; Diamond, S.; Gallego-Urrea, J.A.; Metcalfe, C.; Rose, J.; Horne, N.; Koelmans, A.A.; Klaine, S.J. Potential scenarios for nanomaterials release and subsequent alteration in the environment. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2012, 31, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thwala, M.; Klaine, S.J.; Musee, N. Interactions of metal-based engineered nanoparticles with aquatic higher plants: A review of the state of current knowledge. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2016. 35 2016, 35, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar]

- Stebounova, L.S.; Guio, E.; Grassian, V.H. Silver nanoparticles in simulated biological media: a study of aggregation, sedimentation, and dissolution. J. Nanopart Res. 2011, 13, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehah, M.O.; Aziz, H.A.; Stoll, S. Nanoparticle properties, behaviour, fate in aquatic systems and characterization methods. J. Coll. Sci. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.; Mudumkotuwa, I.A.; Rupasinghe, T.; Grassian, V.H. Aggregation and dissolution of 4nm ZnO nanoparticles in aqueous environments: influence of pH, ionic strength, size, and adsorption of humic acid. Langmuir 2011, 27, 6059–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tang, N.; Guo, J.; Lu, L.; Li, N.; Hu, T.; Liang, J. The aggregation of natural inorganic colloids in aqueous environment: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Williams, P.L.; Diamond, S.A. Ecotoxicity of manufactured ZnO nanoparticles: A review. Environ. Poll. 2013, 172, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M.; Baalousha, M.; Chen, J.; Chaudry, Q.; Kammer, F.; Kuhlbusch, T.A.J.; et al. A review of the properties and processes determining the fate of engineered nanomaterials in the aquatic environment. Critical Rev. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 2015, 45, 2084–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaye, N.; Thwala, M.; Cowan, D.; Musee, N. Genotoxicity of metal based engineered nanoparticles in aquatic organisms: A review. Mutation Res. Rev Mutation Res. 2017, 773, 134–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, N.B.; Erkan, H.S.; Engin, G.O.; Bilgili, M.S. Nanoparticles in the aquatic environment: usage, properties, transformation and toxicity-A review. Process Safety Environ. Protection 2019, 130, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuvaneshwari, M.; Bairoliya, S.; Parashar, A.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Differential toxicity of Al2O3 particles on Gram-positive and Gram-negative sediment bacterial isolates from freshwater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 12095–12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Tang, Y.; Yang, F.G.; Li, X.L.; Xu, S.; Fan, X.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Yang, Y.J. Cellular toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in anatase and rutile crystal phase. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2011, 141, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, S.; Lin, S.; Ji, Z.; Thomas, C.R.; Li, L.; Mecklenburg, M.; Meng, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, T. Surface defects on plate-shaped silver nanoparticles contribute to its hazard potential in a fish gill cell line and zebrafish embryos. ACS nano 2012, 6, 3745–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalman, J.; Paul, K.B.; Khan, F.R.; Stone, V.; Fernandes, T.F. Characterisation of bioaccumulation dynamics of three differently coated silver nanoparticles and aqueous silver in a simple freshwater food chain. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 662–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, J.; Bergum, S.; Nilsen, E.W.; Olsen, A.J.; Salaberria, I.; Ciesielski, T.M.; Bączek, T.; Konieczna, L.; Salvenmoser, W.; Jenssen, B.M. The impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on uptake and toxicity of benzo (a) pyrene in the blue mussel (Mytilus edulis). Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 511, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.; Alarifi, S.; Kumar, S.; Ahamed, M.; Siddiqui, M.A. Oxidative stress and genotoxic effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles in freshwater snail Lymnaea luteola L. Aquat. Toxicol. 2012, 124, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, W.; Slaveykova, V.I. Effects of mixtures of engineered nanoparticles and metallic pollutants on aquatic organisms. Environ. 2020, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E. , Piccapietra, F., Wagner, B., Marconi, F., Kaegi, R., Odzak, N., Sigg, L.; Behra, R. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8959–8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaine, S.J.; Alvarez, P.J.J.; Batley, G.E.; Fernandes, T.F.; Handy, R.D.; Lyon, D.Y.; Mahendra, S.; McLaughlin, M.J.; Lead, J.R. Nanomaterials in the environment: Behavior, fate, bioavailability, and effects. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2008, 27, 1825–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, L.C.; Ede, J.D.; Snell, D.A.; Oliveira, T.M.; Martinez-Rubi, Y.; Simard, B.; Luong, J.H.; Goss, G.G. Physicochemical properties of functionalized carbon-based nanomaterials and their toxicity to fishes. Carbon 2016, 104, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.P.; Baretta, J.F.; Santos, F.; Paino, I.M.M.; Zucolotto, V. Toxicological effects of graphene oxide on adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Aquatic Toxicol. 2017, 186, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo-Attwood, T.; Unrine, J.M.; Stone, J.W.; Murphy, C.J.; Ghoshroy, S.; Blom, D.; Bertsch, P.M.; Newman, L.A. Uptake, distribution and toxicity of gold nanoparticles in tobacco (Nicotiana xanthi) seedlings. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, C.M. , J.R., Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Chemistry, Biochemistry of nanoparticles, and their role in antioxidant defense system in plants. In Nanotechnology and Plant Sciences; Siddiqui, M.H., Al-Whaibi, M., Mohammad, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2015; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gardea-Torresdey, J.L.; Rico, C.M.; White, J.C. Trophic transfer, transformation, and impact of engineered nanomaterials in terrestrial environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, M.; Gowtham, H.G.; Singh, S.B.; Shilpa, N.; Aiyaz, M.; Alomary, M.N.; et al. Fate, bioaccumulation and toxicity of engineered nanomaterials in plants: Current challenges and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811, 152249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priester, J.H.; Ge, Y.; Mielke, R.E.; Horst, A.M.; Moritz, S.C.; Espinosa, K.; et al. Soybean susceptibility to manufactured nanomaterials with evidence for food quality and soil fertility interruption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, E2451–E2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Sun, Y.; Ji, R.; Zhu, J.; Wu, J.; Guo, H. TiO2 and ZnO nanoparticles negatively affect wheat growth and soil enzyme activities in agricultural soil. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phogat, N.; Khan, S.A.; Shankar, S.; Ansary, A.A.; Uddin, I. Fate of inorganic nanoparticles in agriculture. Adv. Mat. Lett. 2016, 7, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Metal based nanoparticles in agricultural system: behavior, transport, and interaction with plants. Chem. Speciat. Bioavailab. 2018, 30, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.; Minkina, T.; Sushkova, S.; Behal, A.; Maksimov, A.; Blicharska, E.; Ghazaryan, K.; Movsesyan, H.; Barsova, N. ZnO and CuO nanoparticles: a threat to soil organisms, plants, and human health. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2020, 42, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.A.; Adeleye, A.S.; Conway, J.R.; Garner, K.L.; Zhao, L.; Cherr, G.N.; et al. Comparative environmental fate and toxicity of copper nanomaterials. NanoImpact 2017, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, R.; Wilkinson, K.J.; Sauvé, S. Partitioning of silver and chemical speciation of free Ag in soils amended with nanoparticles. Chem. Cent. J. 2013, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Tong, H.; Shen, C.; Sun, L.; Yuan, P.; He, M.; Shi, J. Bioavailability and translocation of metal oxide nanoparticles in the soil-rice plant system. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Rizvi, A.; Ali, K.; Lee, J.; Zaidi, A.; Khan, M.S.; et al. Nanoparticles in the soil–plant system: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 1545–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.K.; Kumar, V.; Lee, S.; Raza, N.; Kim, K.; Ok, Y.S.; et al. Nanoparticle-plant interaction: implications in energy, environment, and agriculture. Environ. Int. 2018, 119, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauter, M.S.; Zucker, I.; Perreault, F.; Werber, J.R.; Kim, J.; Elimelech, M. The role of nanotechnology in tackling global water challenges. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.; Fedorenko, G.; Fedorenko, A.; Mandzhieva, S.; Sushkova, S.; Morin, T.; Yao, J. Anatomical and ultrastructural responses of Hordeum sativum to the soil spiked by copper. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2020, 42, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.; Minkina, T.; Fedorenko, A.; Sushkova, S.; Mandzhieva, S.; Lysenko, V.; Duplii, N.; Fedorenko, G.; Dvadnenko, K.; Ghazaryan, K. Toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles on spring barley (Hordeum sativum distichum). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.R.; Shaikh, S.S.; Sayyed, R.Z. Modified chrome azurol S method for detection and estimation of siderophores having affinity for metal ions other than iron. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 1, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Keller, A.A. Interactions, transformations, and bioavailability of nanocopper exposed to root exudates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 9774–9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, K.; Dong, S.; Sun, Y.; Gao, B.; Du, W.; Xu, H.; Wu, J. Graphene oxide-facilitated transport of levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin in saturated and unsaturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 348, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Yousaf, B.; Ali, M.U.; Munir, M.A.M.; El-Naggar, A.; Rinklebe, J.; Naushad, M. Transformation pathways and fate of engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) in distinct interactive environmental compartments: A review. Environ. Int. 2020, 138, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Avellan, A.; Laughton, S.; Vaidya, R.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Casman, E.A.; Lowry, G.V. CuO nanoparticle dissolution and toxicity to wheat (Triticum aestivum) in rhizosphere soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 2888–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strekalovskaya, E.I.; Perfileva, A.I.; Krutovsky, K.V. Zinc Oxide nanoparticles in the “Soil–Bacterial community–Plant” system: Impact on the stability of soil ecosystems. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittol, M.; Tomacheski, D.; Simões, D.N.; Ribeiro, V.F.; Santana, R.M.C. Macroscopic effects of silver nanoparticles and titanium dioxide on edible plant growth. Environ. Nanotechnol Monitor. Manag. 2017, 8, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, A.A.; Huang, Y.; Nelson, J. Detection of nanoparticles in edible plant tissues exposed to nano-copper using single-particle ICP-MS. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2018, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gómez, C.; Obrador, A.; González, D.; Babín, M.; Fernández, M.D. Comparative study of the phytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles and Zn accumulation in nine crops grown in a calcareous soil and an acidic soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.P.; King, G.; Plocher, M.M.; Storm, L.R.; Pokhrel, Johnson, M. G.; et al. Germination and early plant development of ten plant species exposed to titanium dioxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2016, 35, 2223–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanık, F.; Vardar, F. Oxidative stress response to aluminum oxide (Al2O3) nanoparticles in Triticum aestivum. Biology 2018, 73, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Arifa, K.; Asmatulu, E. Methodologies of e-waste recycling and its major impacts on human health and the environment. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2021, 27, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, P.S.; Uddin, M.N.; Wooley, P.; Asmatulu, R. Fabrication and biological analysis of highly porous PEEK bionanocomposites incorporated with carbon and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles for biological applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.N.; Desai, F.; Asmatulu, E. Review of bioaccumulation, biomagnification, and biotransformation of engineered nanomaterials, In Nanotoxicology and Nanoecotoxicology Vol 2. Environmental Chemistry for a Sustainable World 67; Kumar, V., Guleria, P., Ranjan, S., Dasgupta, N., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021; pp. 133–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyan, M.S.A.; Uddin, M.N.; Islam, M.M.; Bipasha, F.A.; Hossain, S.S. Synthesis of graphene. Int. Nano Letters, 2016, 6, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J.K.; Bobde, P.; Patel, R.K.; Manna, S. Disposal and Recycling Strategies for Nano-engineered Materials, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA 02139, United States, 2024; pp. 1–170. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Impacts of toxicity | Summary of the study | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of ENPs | The strength of toxicity is inversely related to ENPs’ size. | Al2O3 NP was found to show low toxicity to bacteria in contrast with the same Al2O3 NPs of a size of less than 50 nm. | [43] |

| Crystal structure | Cytotoxicity and genotoxicity are associated with the ENPs’ crystal structure. | The toxicity of Anatase nTiO2 due to oxidative stress was found greater than that of rutile nTiO2. | [44] |

| Surface charge | Surface charge controls the toxicity of NPs by affecting the agglomeration rate. | The silver NPs toxicity was discovered to be dependent on surface charge. | [42] |

| Morphology | Surface charge controls the toxicity of NPs by affecting the agglomeration rate. | Plate-shaped silver NPs have higher toxicity effects on fish gills and zebrafish embryos in contrast with spheres or wire-shaped NPs. | [45] |

| Surface coating | The ENP’s toxicity effects increase or decrease according to the chemistry of their coatings of ENPs. | PVP or citrate-coated silver NPs were more toxic than PEG-coated silver NPs. | [46] |

| Co-pollutant | Inadequate information is found regarding the interaction of nanoparticles with other pollutants in the aquatic media. | Exposure of the blue mussel to both TiO2 and benzo (a) pyrene resulted in greater chromosomal damage while inducing lower results in individual exposure. | [47] |

| Exposure duration and concentration | Both the exposure duration and concentration influence the toxicity of ENPs in the aquatic system. | It is found that the toxicity effects on Lymnaea luteola, an aquatic snail, of exposure to nZnO have a dependency on the exposure duration and concentration. | [48] |

| ENPs | Size and dose rate | Test Crop(s) | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | 10 nm and 0.001-10000 mg L-1 | Raphanus sativus, Allium cepa | The growth of plant roots was inhibited. | [77] |

| CuO | 20-100 nm and 34.4 g m2 | Brassica oleracea var. viridis, Brassica oleracea var. sabella & Lactuca sativa | Large amounts of CuO accumulated on the surface of lettuce leaves and subsequently kale and collard green. | [78] |

| ZnO | <100 nm and 20-900 mg kg-1 soil | Triticum aestivum, Pisum sativum, Zea mays, Lactuca sativa, Raphanus sativus, Beta vulgaris, Solanum lycopersicum, and Crocus sativus | Toxic effects of ZnO NPs depend on plant species; ZnO NPs reduced the availability of Zine while interacting with calcareous soil and as a result toxicity to accumulation of biomass by wheat, beet, and cucumber, whereas maize, pea, and wheat showed resistance in acidic type soil. | [79] |

| TiO2 | 25 nm and 250–1000 mg L-1 | Crocus sativus, Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Avena sativa | Growth of roots of edible crops such as corn, oat, cabbage, lettuce, etc. was inhibited and germination of cucumber and soybean was reduced. | [80] |

| Al2O3 | 13 nm and 50 mgm L-1 | Triticum aestivum | H2O2 content, lipid peroxidation, and superoxide dismutase activity were increased; the production of anthocyanin and photosynthetic pigment was reduced. | [81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).