1. Introduction

Road safety is a global issue that impacts public health, social interactions, economics, and transportation. Road traffic accidents have become a major public health problem worldwide. According to annual reports from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Transport Forum (ITF), around 1.35 million people are killed and up to 50 million are injured in traffic accidents each year, resulting in global costs exceeding USD 520 billion [1, 2]. This trend indicates that traffic-related fatalities far exceed the targets set by the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

3]. Road traffic accidents are now ranked among the top 10 leading causes of death globally, just after diabetes mellitus, with vulnerable road users accounting for 50% of the fatalities [

4]. The main factors contributing to road traffic accidents include drivers, vehicles, road conditions, the environment, and other unidentified causes [

5].

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is the largest country in the Arab world, covering approximately 2.1 million square kilometers and with a population of around 34 million. The country is divided into 13 administrative regions [

6]. Over the past four decades, rapid population growth and economic development, particularly after the discovery of oil, have led to higher travel demands, increased motorization, and a rise in traffic accidents [

7,

8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), KSA's road traffic fatality rate (deaths per 100,000 population) exceeds 25, which is significantly higher than that of many developing nations and neighboring Gulf countries. Traffic-related injuries account for more than 80% of hospital deaths and approximately 20% of hospital bed occupancy [

9]. Road traffic injuries are the third leading cause of death in KSA, responsible for 11% of total deaths in the country and costing around 4.3% of the national GDP [

10].

In 2009, Saudi Arabia introduced an automated system to manage and control traffic, utilizing digital cameras linked to electronic systems, known locally as SAHER. This system connects to the National Information Center at the Ministry of Interior [

11]. SAHER is an "Automated System" designed to manage traffic across major cities in Saudi Arabia using a network of digital cameras. These cameras monitor traffic violations, such as running red lights and speeding, capturing clear images of the license plates of offending vehicles. The photos are automatically sent to a traffic violation processing center, where, after retrieving the owner's information from the national database, a ticket is issued. The SAHER program is one of the recent enforcement initiatives aimed at improving traffic system efficiency and reducing road traffic accidents [

11].

Numerous studies have highlighted the effectiveness of both fixed and mobile speed cameras in reducing road traffic accidents [

12,

13,

14]. However, the impact of these cameras in enforcing speed limits is typically confined to the areas immediately surrounding the observation points [

15]. Additionally, variations in speed among vehicles, often caused by sudden braking in monitored zones, have been found to increase the likelihood of accidents [

16]. Another common criticism of red-light cameras at urban intersections is that while they may decrease right-angle collisions, they can lead to a higher frequency of rear-end accidents [

17,

18]. A study by Al Turki [

19] found that while the number of accidents and injuries decreased during the first decade of the SAHER system's operation, fatalities remained unchanged. The study also pointed out that SAHER primarily targets speeding and running red lights, which account for only 31% of traffic collisions. As a result, the system is not fully comprehensive, as it overlooks the remaining 69% of violations, such as lane changes and reckless driving, which also contribute to road accidents.

In recent years, Saudi Arabian authorities have launched several initiatives aimed at improving road safety, including the implementation of the SAHER traffic enforcement system. However, the overall effectiveness of these interventions in enhancing road safety remains inadequately documented and established. To address this gap, this study seeks to analyze traffic accident patterns in Saudi Arabia, with a particular focus on the Dammam Metropolitan Area (DMA), and to assess the safety impact of the SAHER system. The study employs a before-and-after evaluation approach to measure the effectiveness of SAHER, using an analytical descriptive method. The evaluation is based on the insights of 23 experts specializing in road safety, particularly those with expertise in the SAHER system, to provide a comprehensive understanding of its impact on traffic safety. The results of this study are anticipated to provide valuable insights for safety authorities to enhance road safety and monitor traffic conditions effectively. The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 outlines the materials and methods used in the study.

Section 3 presents the study's findings, along with a discussion of the key outcomes. Finally,

Section 4 offers the conclusions drawn from the study and suggests future recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

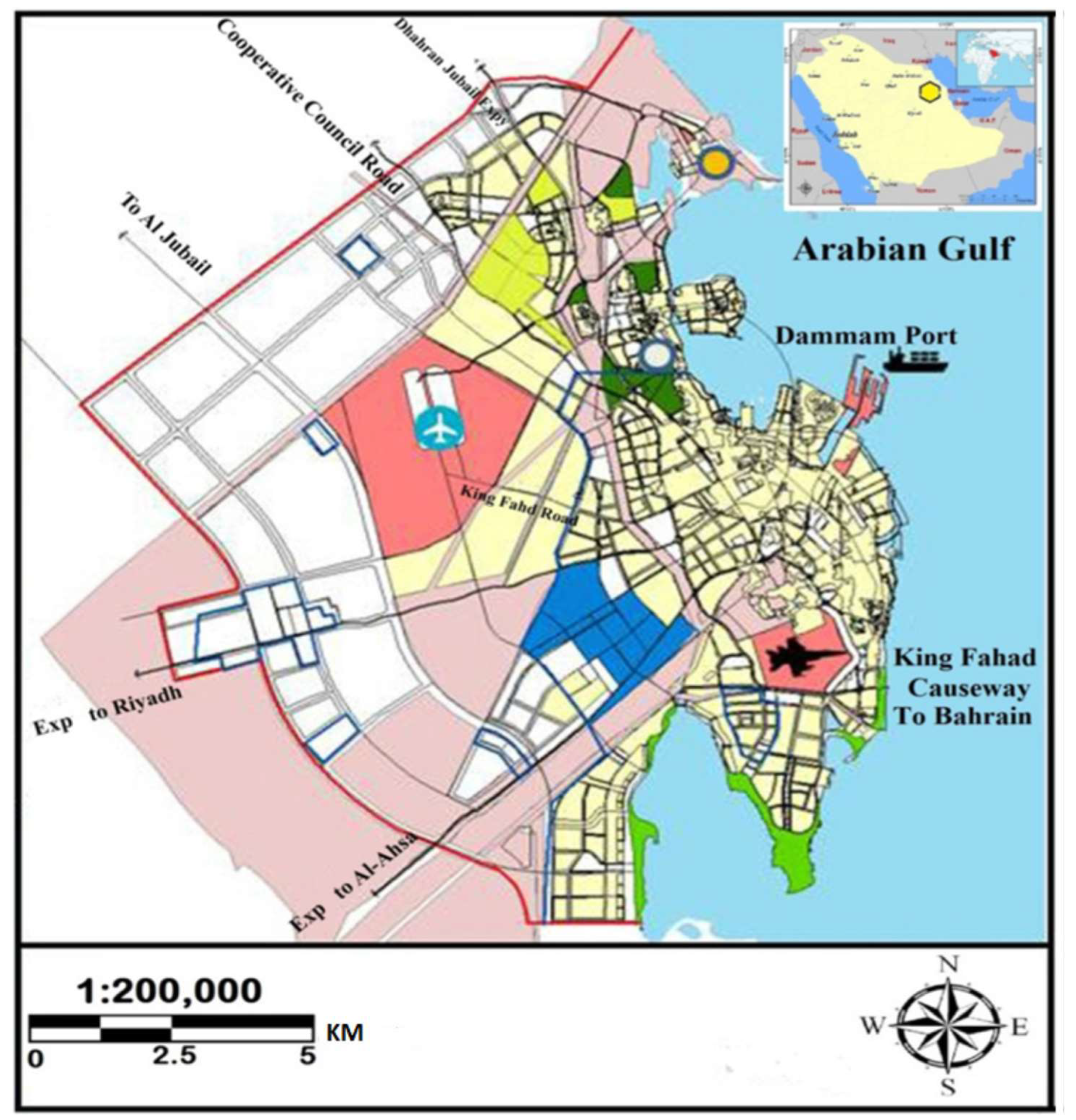

Dammam Metropolitan Area (DMA) has been chosen as the study area for this research. DMA is situated on the coast of the Arabian Gulf, approximately 400 km from Riyadh, the capital of Saudi Arabia. It is the third-largest metropolitan area in Saudi Arabia, following Riyadh and Jeddah, and one of the seven metropolises that that house half of the country’s 33 million residents [

20]. DMA consists of three major cities: Dammam, Khobar, and Dhahran (

Figure 1). Dammam, the capital of the Eastern Province, houses most of the regional administrative bodies; Khobar serves as the business hub of the Eastern Province; and Dhahran is recognized as a center for modern science and technology, particularly in the petroleum industry, hosting the headquarters of the Arab American Oil Company (ARAMCO) [

21]. In recent decades, DMA has undergone rapid population growth, with its population more than doubling. It has risen sharply from 365,000 people in 1974 to 1.75 million in 2004, and currently exceeds 1.8 million, living within an area of approximately 380,000 hectares [

22,

23].

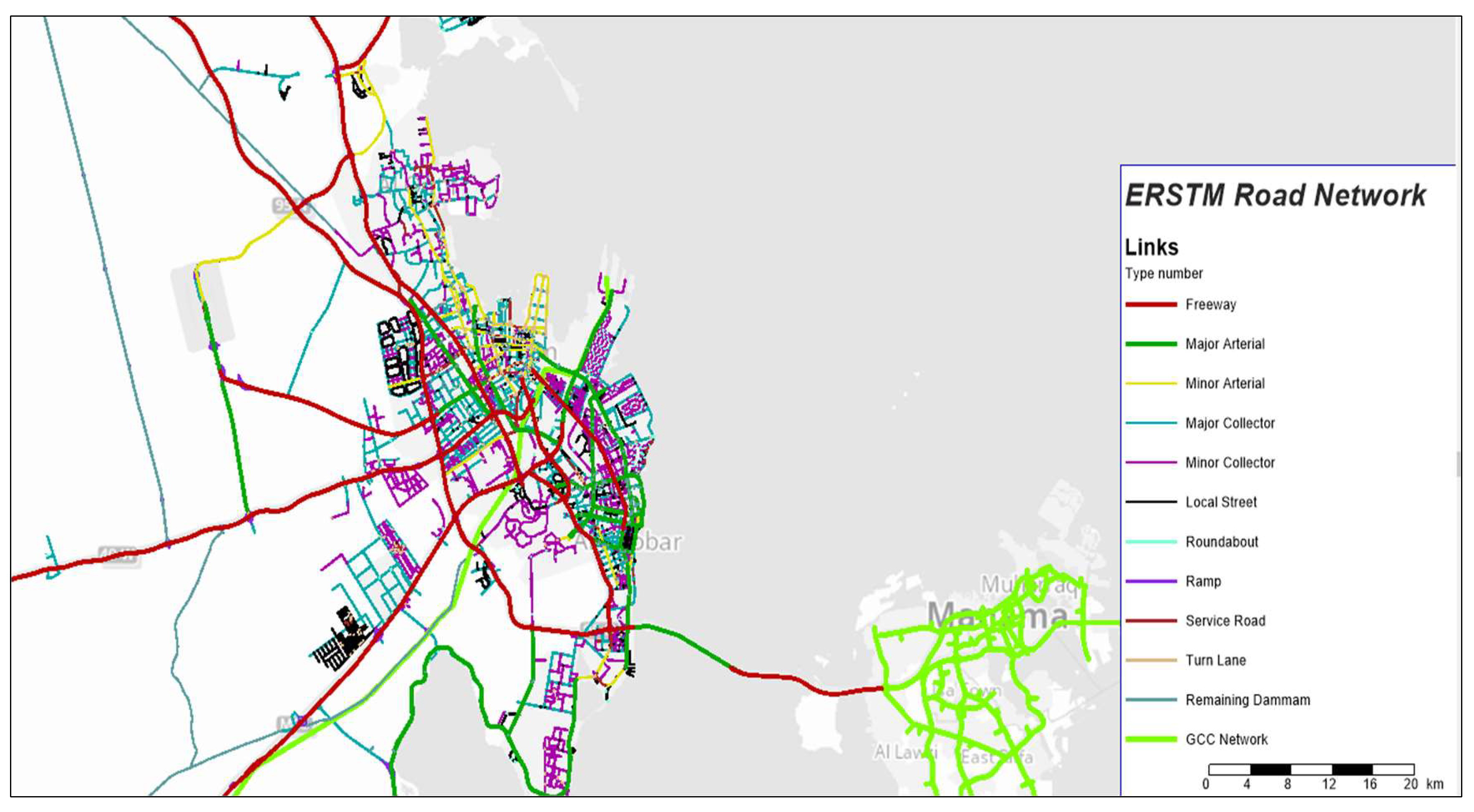

DMA sits at the intersection of roads that connect the Arabian Gulf States of Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman, with Saudi Arabia. There are many prominent landmarks in DMA, such as the Saudi ARAMCO headquarters, King Abdulaziz seaport, King Fahd Airport, and King Fahd Causeway, which connects Saudi Arabia with Bahrain. Due to the presence of seaport and connection to Bahrain and other Gulf States, the metropolis acts as vital communication hub for the rest of the country. There are several different types of roadways comprising well established road networks within DMA. The functional classification includes highways, major and minor arterials as well as collector roads. Some of the important major arterials may include King Saud Road, Prince Muhammad Bin Fahd Road, and King Abdullah Road. DMA predominantly depends upon roundabouts and signalized intersections to manage traffic flow within the metropolis. DMA is also emphasizing over the signal-free corridors by introducing U-turns at regular intervals by removing traffic signals. King Faisal Road is one of the examples of this strategy. The latest road network, along with their functional classifications, within DMA can be seen in

Figure 2 which is derived from the Eastern Region Strategic Demand Model (ERSDM) and compiled by Sharqia Development Authority (SDA).

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

A structured questionnaire was used in this study to achieve the main aim, which is to gather insights into the experts' views and experiences concerning road safety, SAHER, enforcement cameras, and the condition of road infrastructure in DMA. The questionnaire design was structured into six sections: (1) demographic details of the respondents; (2) expert views on the road safety situation in DMA; (3) experts' perspectives on the causes of car accidents in DMA; (4) experts' views on the current status of SAHER in DMA; (5) experts' insights on the role of SAHER in overall road safety; and (6) experts' recommendations for enhancing road safety and the SAHER system. The majority of the questions were close-ended, with responses based on a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. Other questions involved choosing from yes, no, or neutral options. To enhance its validity, the questionnaire was initially piloted with the researchers' colleagues to assess the accuracy of the questions.

After conducting the pilot questionnaire and necessary revision, the questionnaire was conducted online. An online questionnaire was developed using the Question Pro platform. Based on the responses, a selection of respondents was also interviewed for more detailed feedback. The data from this questionnaire and interviews was used for mostly quantitative but also some qualitative analyses. The purposive sampling technique was used for the experts' questionnaire [

25]. A list of experts directly or indirectly involved with road safety decisions, including those working in planning bodies (municipality, ministries etc.), engineering organizations (Saudi Aramco, engineering consultants etc.), public health, law enforcement etc. constituted the sampling frame for the questionnaire. The calculations were performed employing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and Microsoft Excel software. Descriptive and cross table analysis were performed among the variables in the questionnaire.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Details of the Respondents

Table 1 provides a summary of the main characteristics of the experts taking part in this study. Among the total respondents, 34.8% were aged between 41 and 50 years, 26.1% were between 30 and 40 years, 21.7% were between 51 and 60 years, and 17.4% were over 60 years old. The analysis of the respondents' characteristics reveals that all participants were male, with no female participants recorded. This lack of female participation highlights the lower representation of women in the transport industry, particularly in road safety. The majority of respondents were Saudi experts, making up 78%, while non-Saudis represented 22%. The experts taking part in the study were inquired about their education level, with the largest group 43.5% (10 in total) holding a PhD. Those with a bachelor’s or master’s degree had the second-highest response rate, each at 26.1%. The analysis indicates that the majority of experts come from the Government/Public sector (47.8%), followed by those from the private sector (26.1%), retired personnel (17.4%), and security forces (8.7%). In this study, the majority of respondents (43.5%) have more than 25 years of experience, suggesting that most participants possess sufficient expertise to offer a well-informed perspective on the road safety in DMA. The majority of experts have over 25 years of driving experience (60.9%). Additionally, the results reveal that most participants (78.3%) reside in DMA, while the remaining 21.7% live in various other regions.

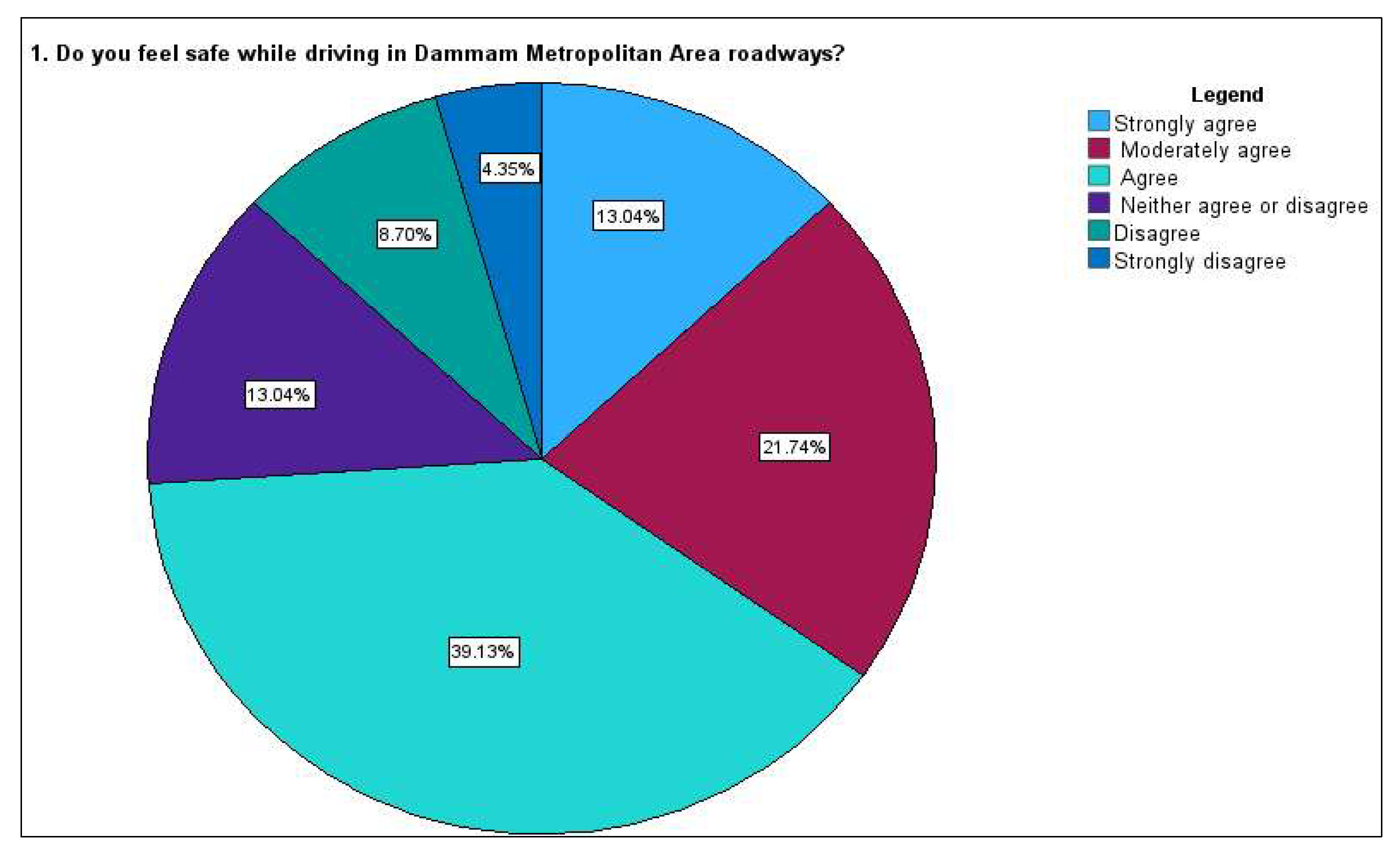

3.2. Expert Views on the Road Safety Situation in DMA

The study participants were asked to assess their sense of safety while driving in and around the DMA. Overall, nearly 74% of experts reported feeling safer, with varying degrees of agreement ranging from some agreeing to others moderately or strongly agreeing. The results are presented in

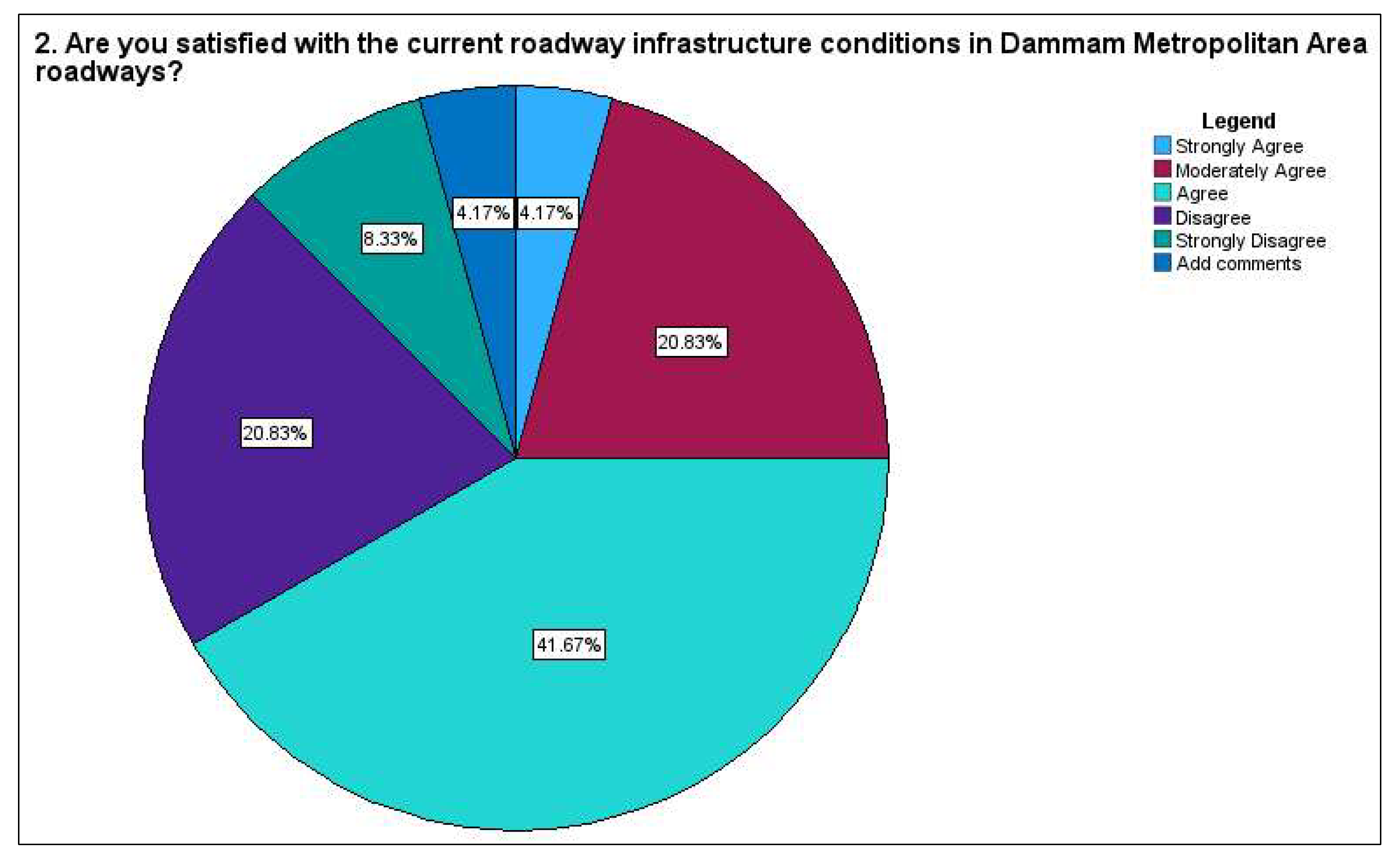

Figure 3. The participants were asked to assess the current road infrastructure in Dammam, providing insight into expert users' views on the available transportation infrastructure. The analysis of the results reveals that a significant proportion of participants are satisfied with the existing infrastructure, with nearly 66% expressing satisfaction, moderate satisfaction, or strong satisfaction. However, a considerable number of experts (34%) believe that the current road infrastructure is inadequate from a safety perspective. The breakdown of this analysis is shown in

Figure 4.

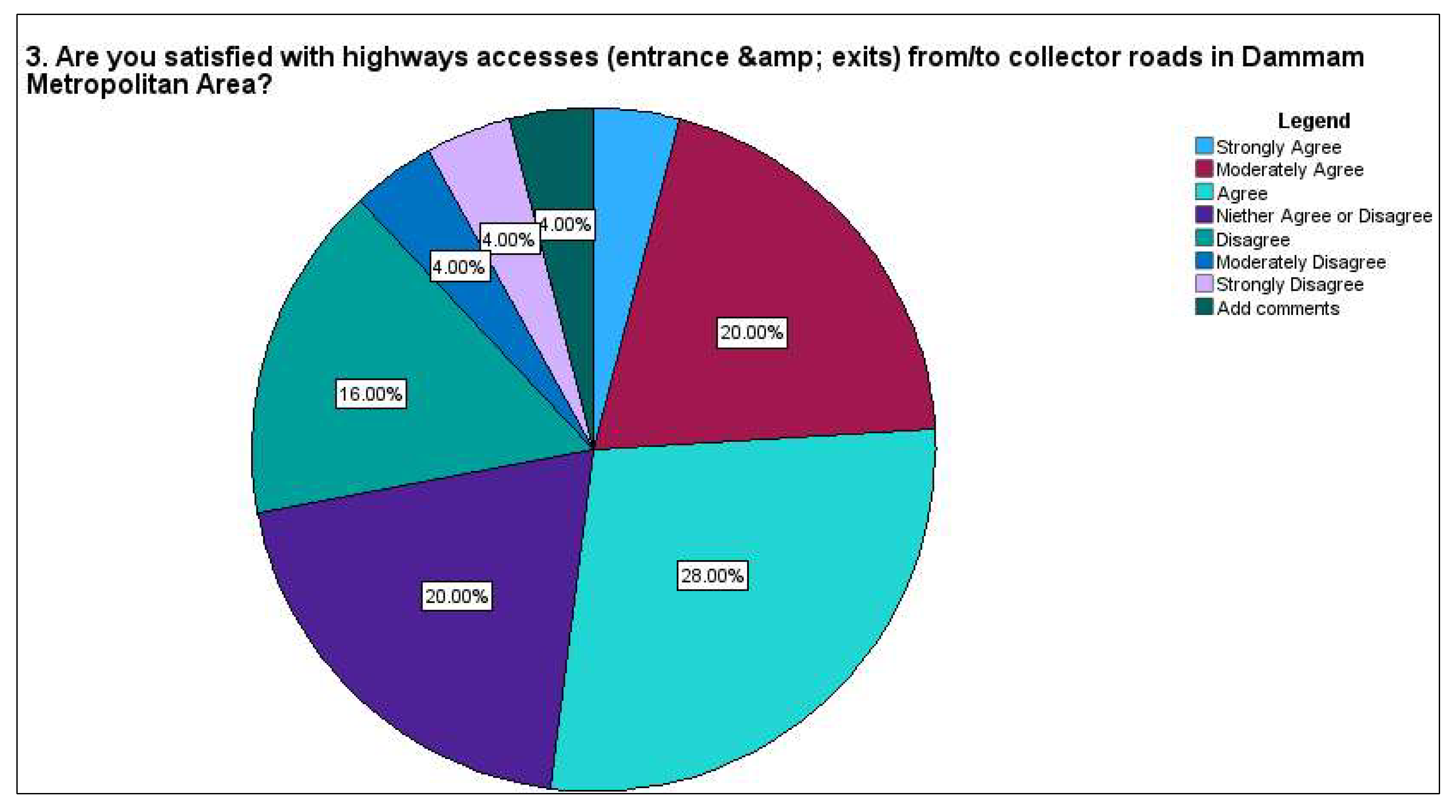

Highway accesses are crucial for safety, so experts were consulted to evaluate them. The analysis revealed that approximately 50% of the experts were satisfied with the accesses, while 24% rated the entrances and exits as poor quality. Meanwhile, 20% of the respondents neither expressed satisfaction nor dissatisfaction with the highway accesses. A detailed analysis of this question can be found in

Figure 5. Also, experts were asked to evaluate the traffic signs, lane markings, and traffic lights. The analysis of the results shows that a nearly equal percentage of experts are either satisfied (49%) or dissatisfied (47%) with the traffic signs and lane markings in DMA (

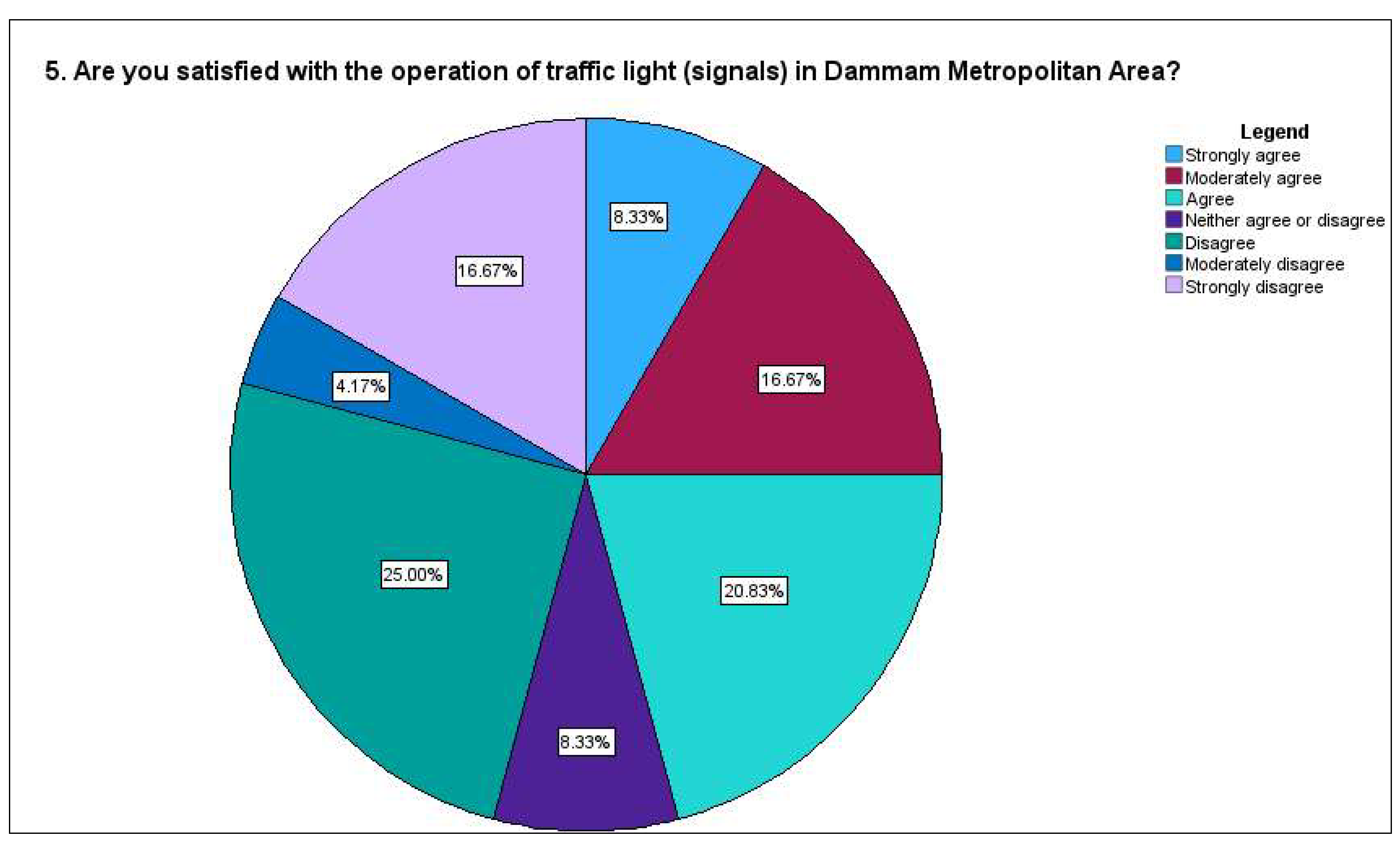

Figure 6). This indicates a clear need for improvement in this area. Additionally, most experts (48%) expressed dissatisfaction with the operation of traffic lights in DMA (

Figure 7). They believe that the fixed timing plans of the DMA signals need to be revised. This clearly highlights the need for improvements in traffic signal operations in the region.

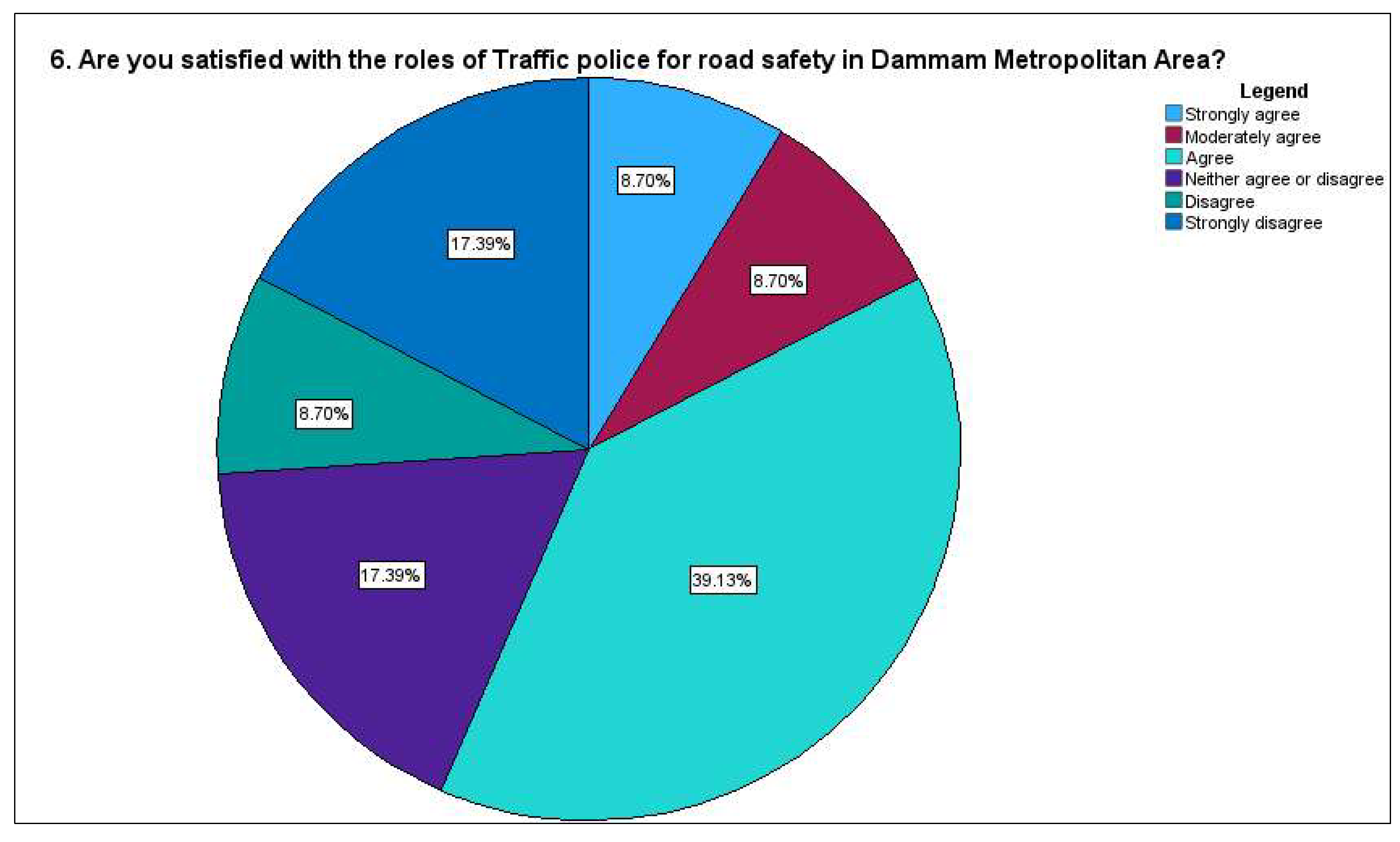

Building on the previous questions in this section, question six addressed the role of traffic police in ensuring road safety within DMA. This question was crucial for understanding experts’ perception of the traffic police's effectiveness in promoting road safety. The analysis revealed that most respondents were satisfied with the traffic police's role, while nearly 18% expressed strong dissatisfaction. Additionally, another 18% of participants indicated a neutral stance, showing neither satisfaction nor dissatisfaction with their experience as can be seen in

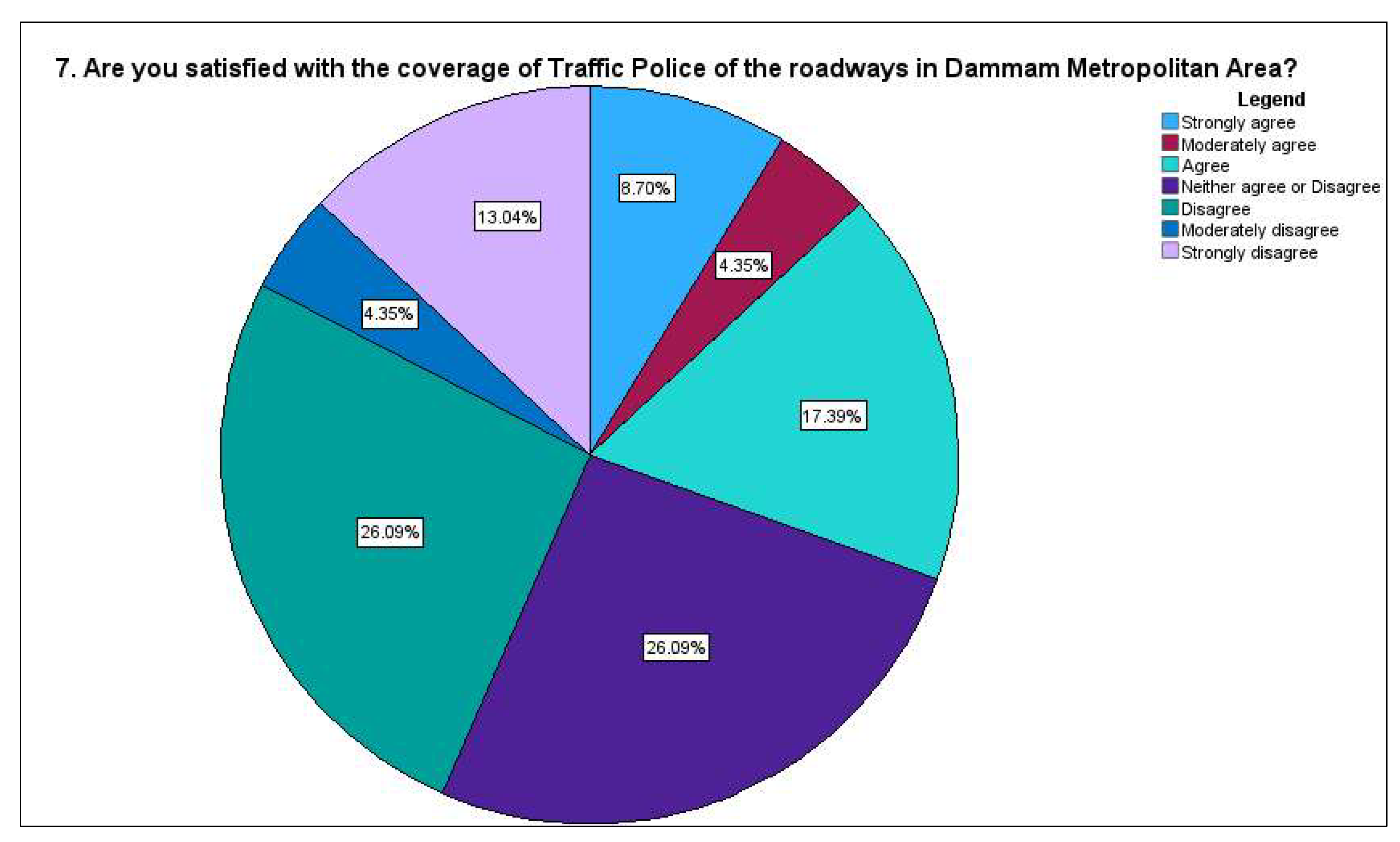

Figure 8. A related question to question six was posed to assess whether DMA is satisfied with the traffic police's presence. About 45% of experts feel that there should be greater coverage from the traffic police in enforcing road safety within DMA. Nearly 26% of experts had no opinion on the matter. Overall, the data indicates that experts believe more attention should be directed toward increasing the traffic police's presence for enforcement purposes. The analysis of this question is presented in

Figure 9.

3.3. Experts' Perspectives on the Causes of Car Accidents in DMA

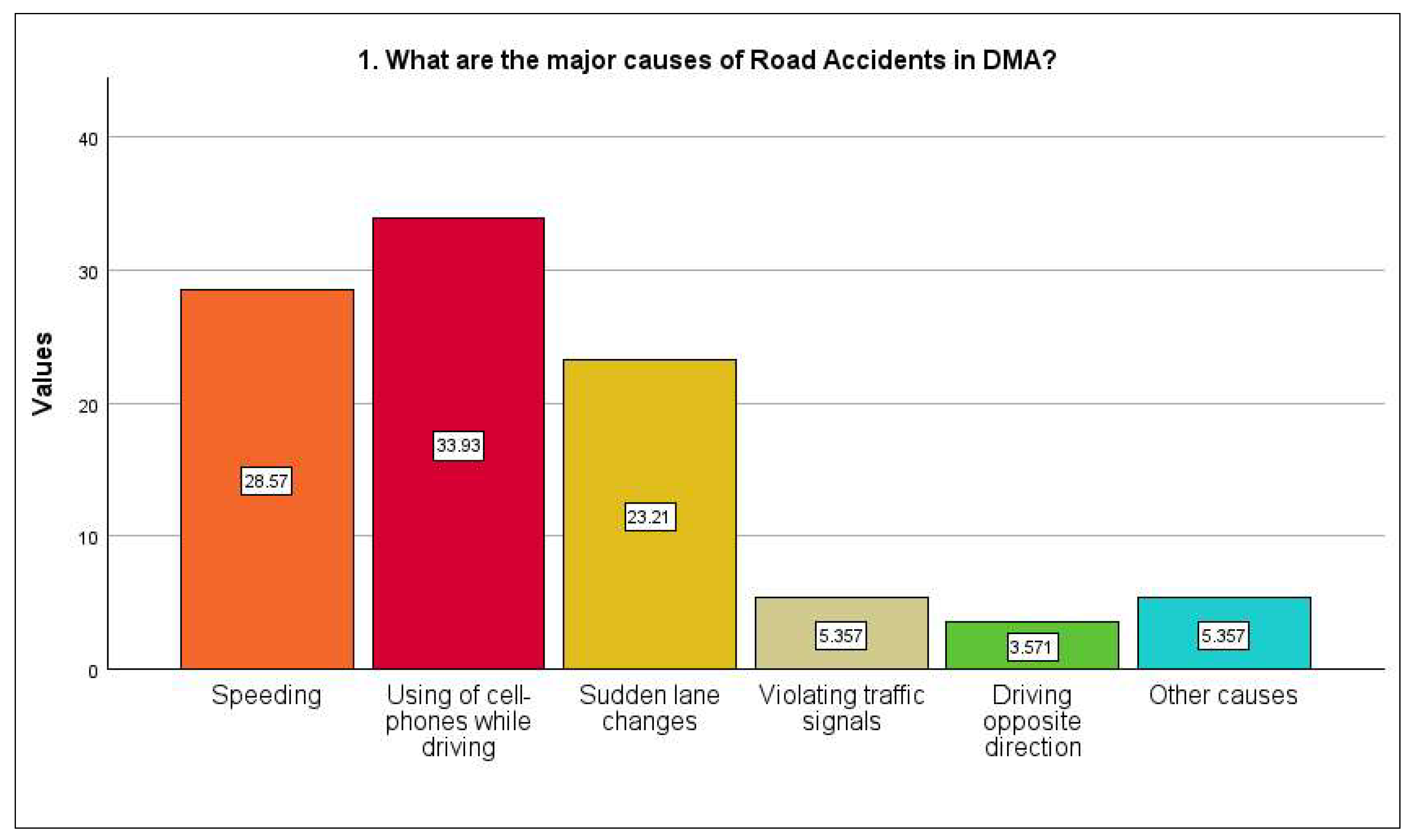

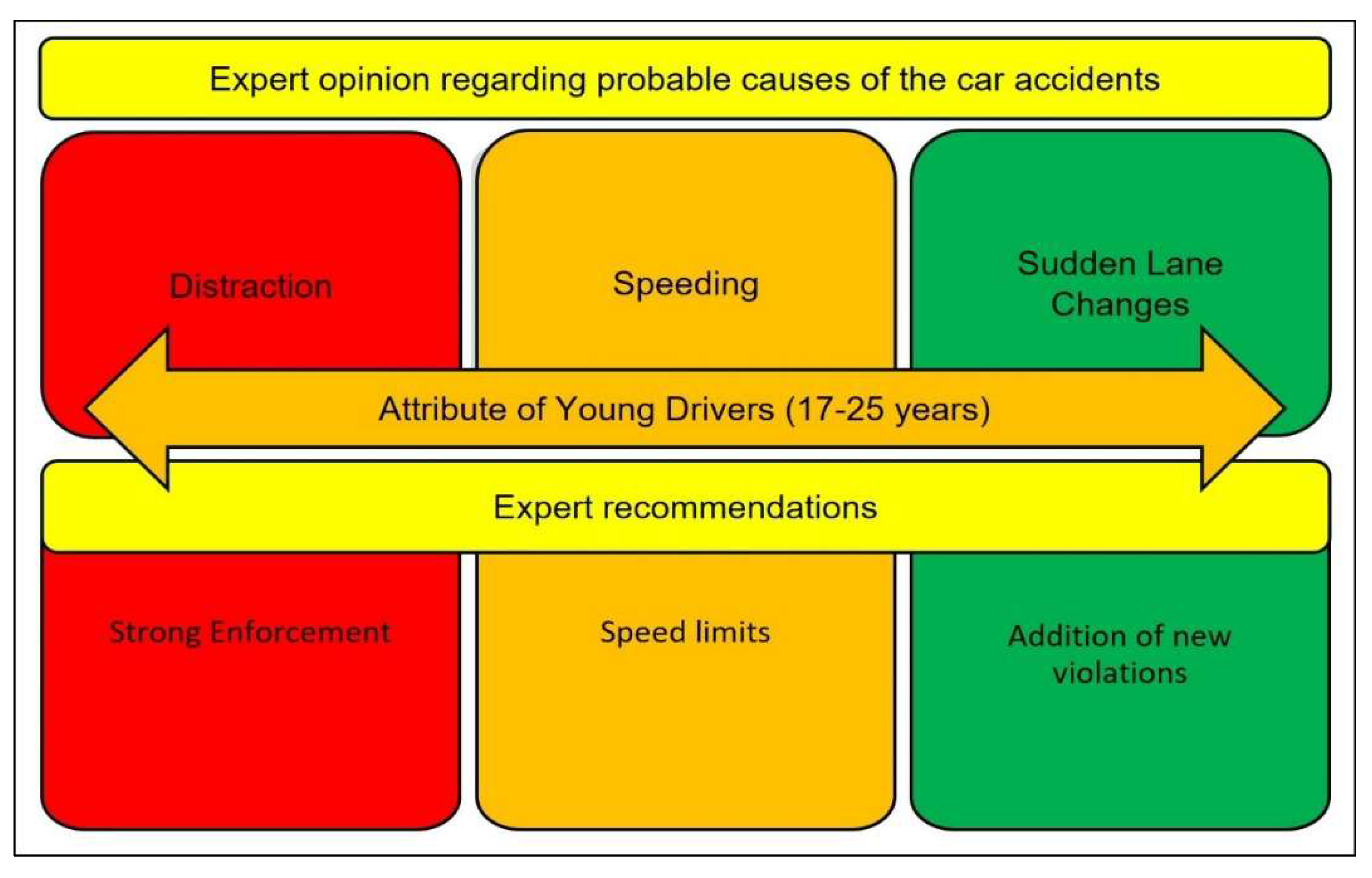

Following the second section of the questionnaire, three questions were posed to identify the potential causes of car accidents in DMA. The first question in this section aimed to gather opinions on the primary causes of accidents in the area. Expert respondents identified driver distractions (such as using cell phones, 33.9%), speeding (28.6%), and sudden lane changes (23.2%) as the leading causes. A detailed breakdown of the results can be found in

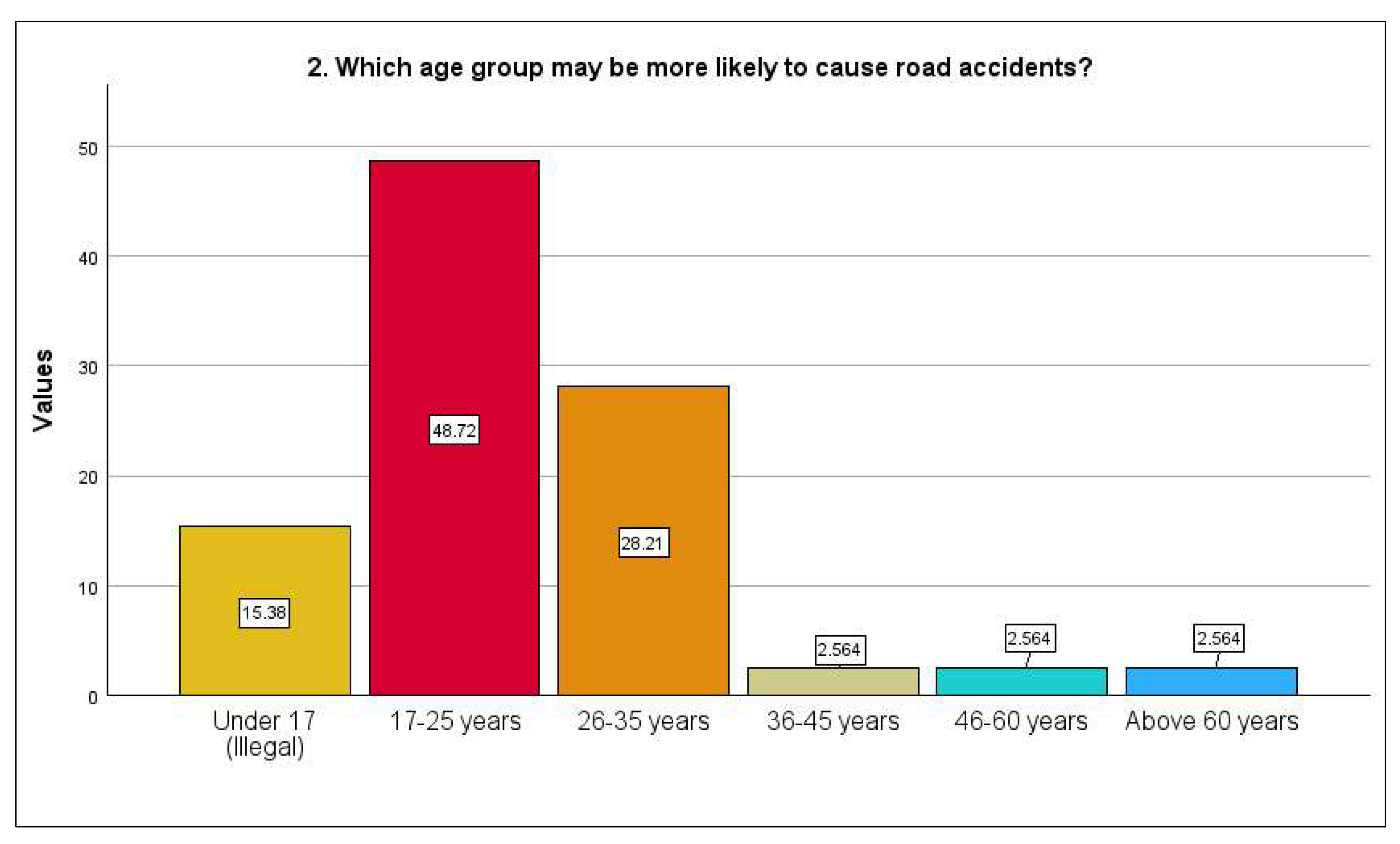

Figure 10. Experts believe that young individuals under the age of 25 are more likely to be involved in road incidents. Specifically, the age group of 17-25 years (48.7%) was identified as the most prone to road accidents by respondents. Additionally, drivers under the age of 17 were also seen as vulnerable to serious accidents, with 18% of experts highlighting this group (

Figure 11).

Additionally, a cross-table analysis of questions 1 and 2 in this section reveals a strong correlation between the 17-25 age group and both speeding and driver distractions while driving. The findings from this questionnaire align with the trends identified in the literature review regarding speeding and distractions among young drivers. The analysis of the cross-table is presented in

Table 2. The final question in this section addressed the existing safety policies and their potential weaknesses. Experts were asked if they believed the current traffic police road safety policies (including operations, regulations, etc.) had any shortcomings. The analysis of this question revealed that experts held mixed opinions, with some believing the policies are sufficient, while others suggested improvements were necessary, such as stronger enforcement, updating signal operations, and revising speed limits.

3.4. Experts' Views on the Current Status of SAHER in DMA

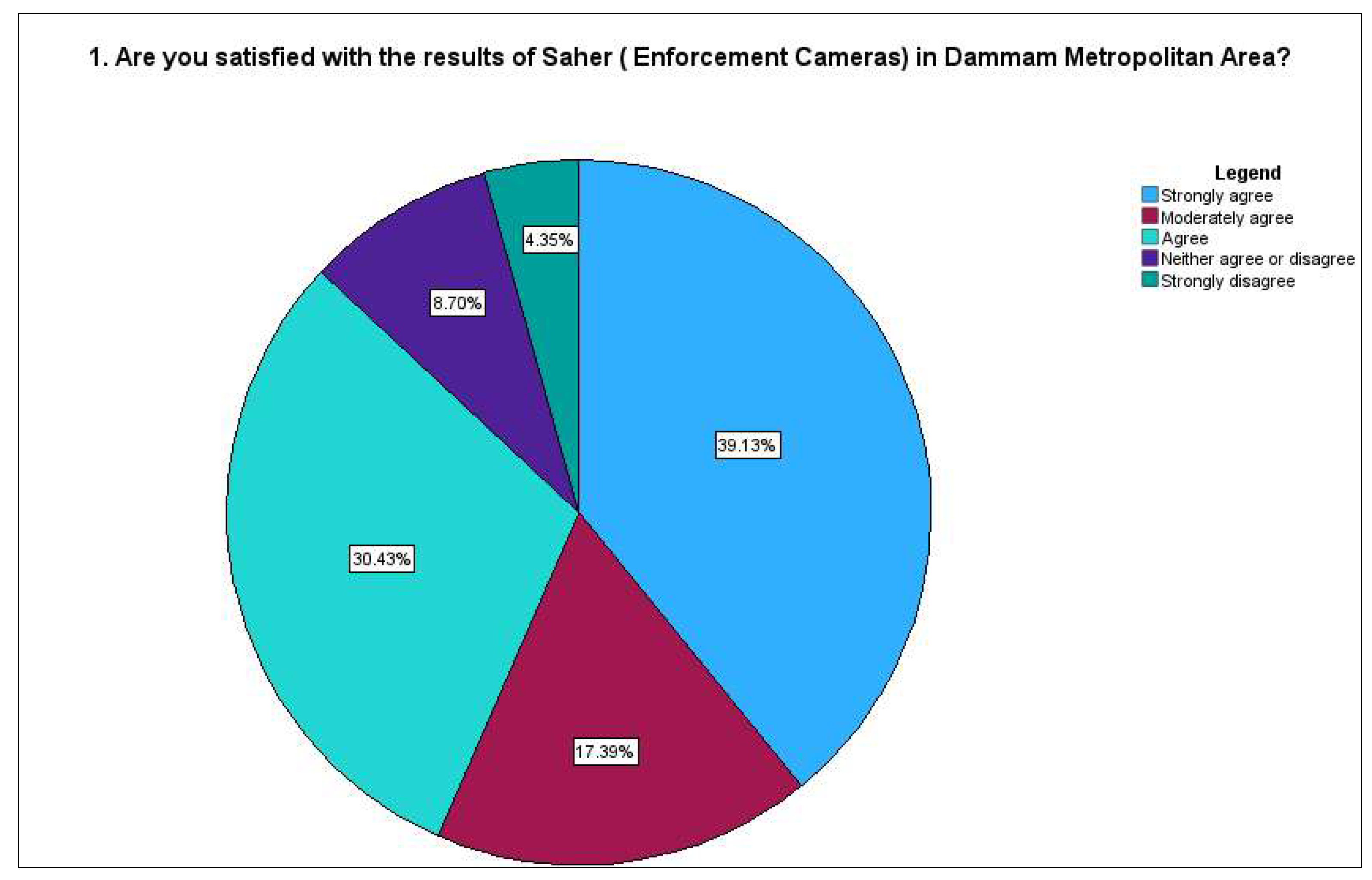

Section four of the questionnaire survey focused on participants' perceptions of the current status of SAHER in DMA. To gather insights, five questions were asked. The section began with a question about the impact of SAHER on road safety in DMA. The analysis revealed that 86% of participants expressed strong satisfaction with the results of the SAHER cameras. These findings indicate that, according to expert opinions, enforcement cameras play a crucial role in road safety. The results of the first question are shown in

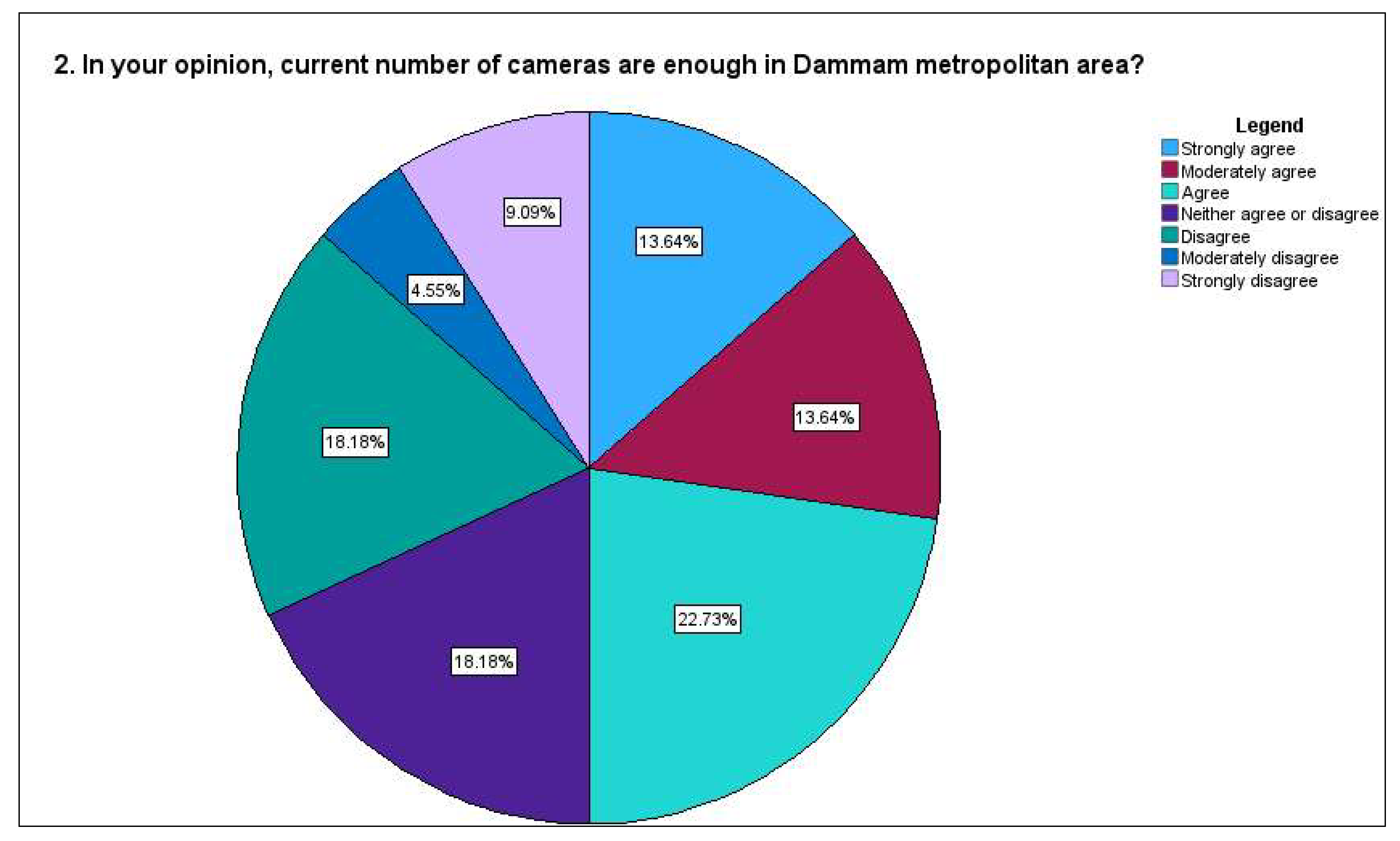

Figure 12. The second question asked experts about the number of cameras in DMA. The results showed that 50% of participants believed the current number of cameras is sufficient for addressing road safety, while 20% had no opinion. The remaining respondents felt that the number of cameras should be increased in DMA. The results are presented in

Figure 13.

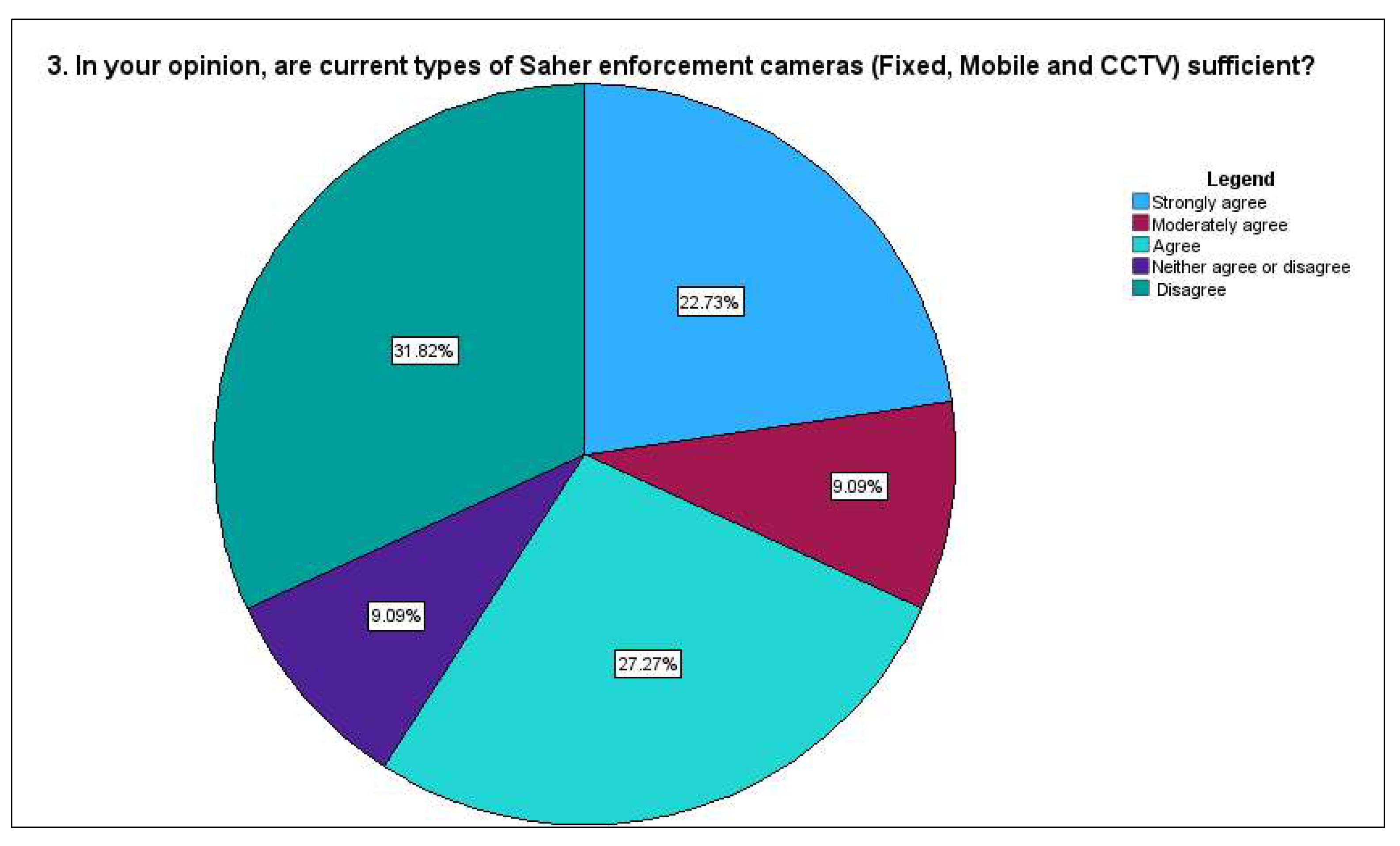

The third question in this section asked experts about the adequacy of the current types of SAHER enforcement cameras (Fixed, Mobile, and CCTV). The results indicated that 55% of respondents are confident in the existing types of SAHER cameras, while approximately 33% of respondents suggested the introduction of different types within the SAHER program.

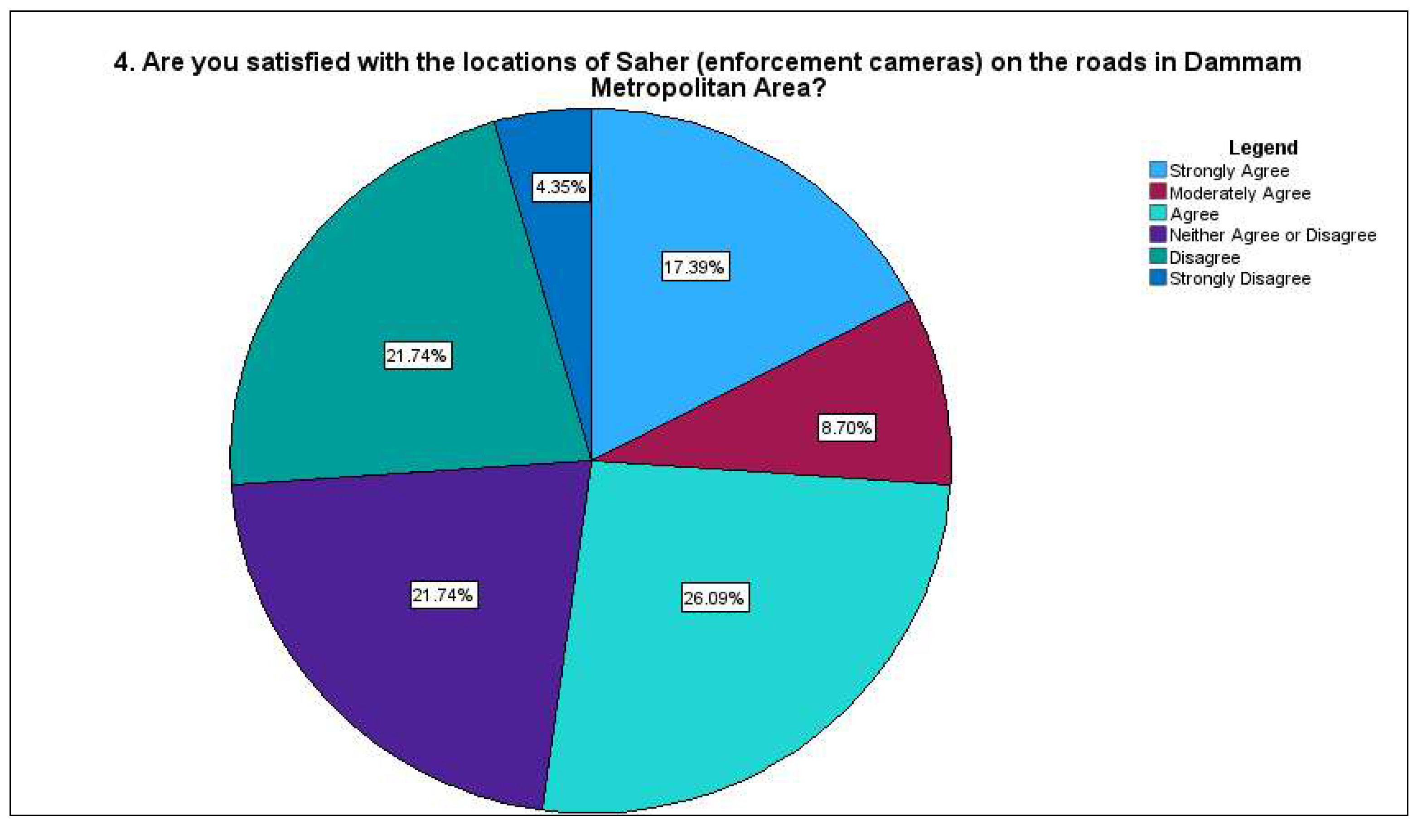

Figure 14 presents the results for this question. Question four addressed the placement of cameras in DMA. The analysis of the questionnaire revealed that approximately 52% of respondents believed the current camera locations on the roads are appropriate, while around 25% felt additional locations should be considered. About 21% of participants did not have an opinion on where the cameras should be placed. The complete results are shown in

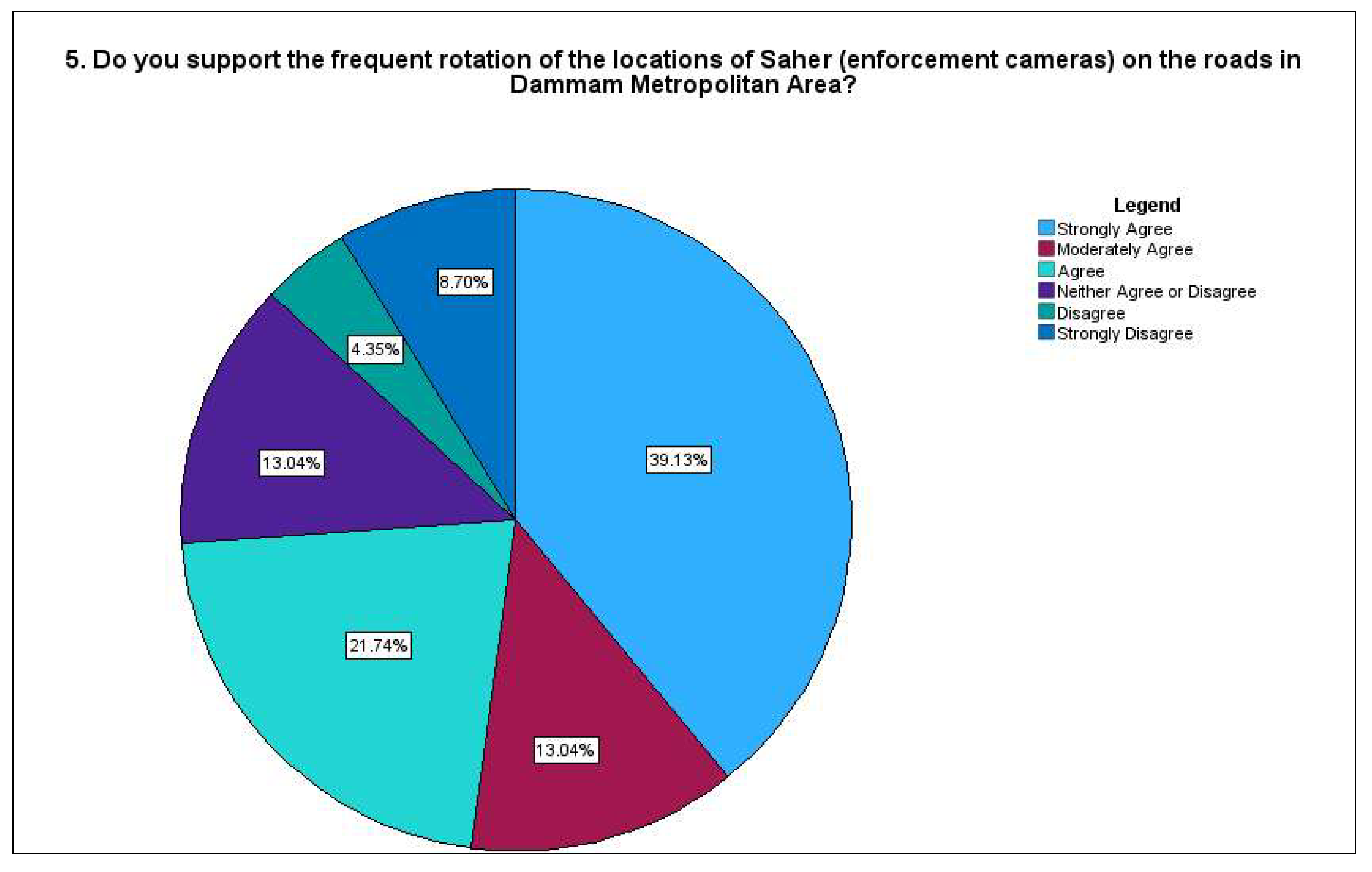

Figure 15. The fifth question, similar in nature to the previous one, inquired about the rotation of camera locations on the roads. While about 50% of experts were satisfied with the current camera placements, the results of this question revealed that 73% of participants believed it would be beneficial to frequently rotate the camera locations. A detailed breakdown of the results is shown in

Figure 16.

3.5. Experts' Insights on the Role of SAHER in Overall Road Safety

This section of the questionnaire consisted of seven questions exploring the connection between SAHER cameras and road safety. Experts were initially asked whether SAHER (enforcement) cameras contribute to improving road safety by reducing car accidents. Nearly all experts (95.65%) agreed that SAHER cameras positively impact road safety, while only one expert disagreed, responding with "No". The second question aimed to gather a deeper understanding of the impact of SAHER cameras on road safety, specifically regarding the potential for increased car accidents caused by sudden stops or braking near camera locations. The results revealed that the majority of experts (39%) were uncertain about the impact, while 34% believed that accidents are not caused by sudden stops or braking near SAHER cameras. However, nearly 26% of participants thought that an accident could occur due to sudden braking near camera sites. Question three inquired about the presence of SAHER cameras and their impact on feelings of safety on the roadways. As expected, most respondents (73.9%) reported feeling safer with cameras on the road, while a smaller portion (8.7%) indicated they do not feel safer, and 17.4% were unsure.

The fourth question aimed to gauge experts' opinions on integrating undercover police with the SAHER program to enhance road safety. A majority of experts (52.2%) believed it could be beneficial, while a smaller group (17.4%) thought it might not be effective. Meanwhile, 30.4% of the respondents were uncertain about their stance. The fifth question sought to emphasize the importance of enhancing road safety near schools and colleges, especially given the higher pedestrian traffic in these areas, which calls for additional SAHER enforcement cameras. As expected, most experts (82.6%) agreed, while a notable percentage (13%) were uncertain, and 4.4% believed it might not be effective. The sixth question focused on highlighting the need to improve road safety near malls, particularly due to the high pedestrian traffic in these areas, which necessitates the installation of additional SAHER enforcement cameras. The majority of respondents (65.2%) agreed that cameras should be placed near malls due to the high volume of pedestrians, while a smaller group (21.8%) disagreed, and 13% were unsure of their opinion. The final question in this section sought the experts' views on whether SAHER should be incorporated into the infrastructure for future master planning. The majority of participants (82.6%) agreed, while a smaller portion (8.7%) disagreed, and another (8.7%) were uncertain.

3.6. Experts' Recommendations for Enhancing Road Safety and the SAHER System

In the final section of the questionnaire, experts were asked to provide not only the available options but also their own recommendations to help achieve the questionnaire's objective, which is to gather insights into the experts' views and experiences concerning road safety, SAHER, enforcement cameras, and the condition of road infrastructure in DMA. In the first question, experts were asked to propose enhancements to the SAHER program. As shown in

Figure 17, experts suggested various improvements including wider coverage, advance warning system, public education and awareness, and undercover surveillance. The experts were also asked to provide their opinions on possible new violations to be incorporated into the existing SAHER program. They suggested several new violation ideas, as depicted in

Figure 18 including aggressive driving such as sudden lane changes, tailgating, and driving over hard shoulder.

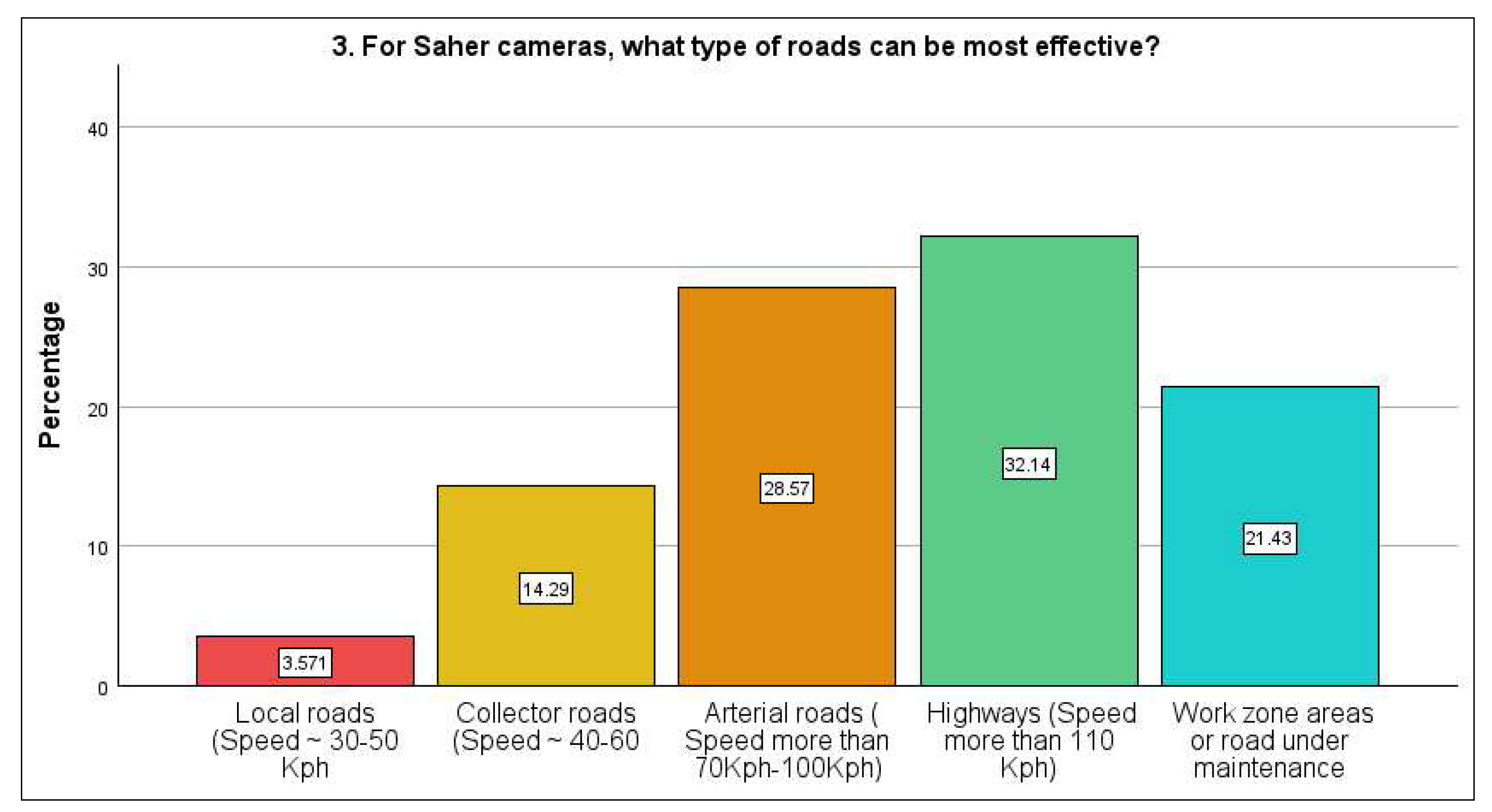

The third question of this section sought to gather expert opinions on camera placement across different types of urban roadways. The results could assist stakeholders in DMA with camera distribution. Experts believe cameras should be primarily installed on high-speed highways, with arterial roads and work zone areas also recommended for priority installations.

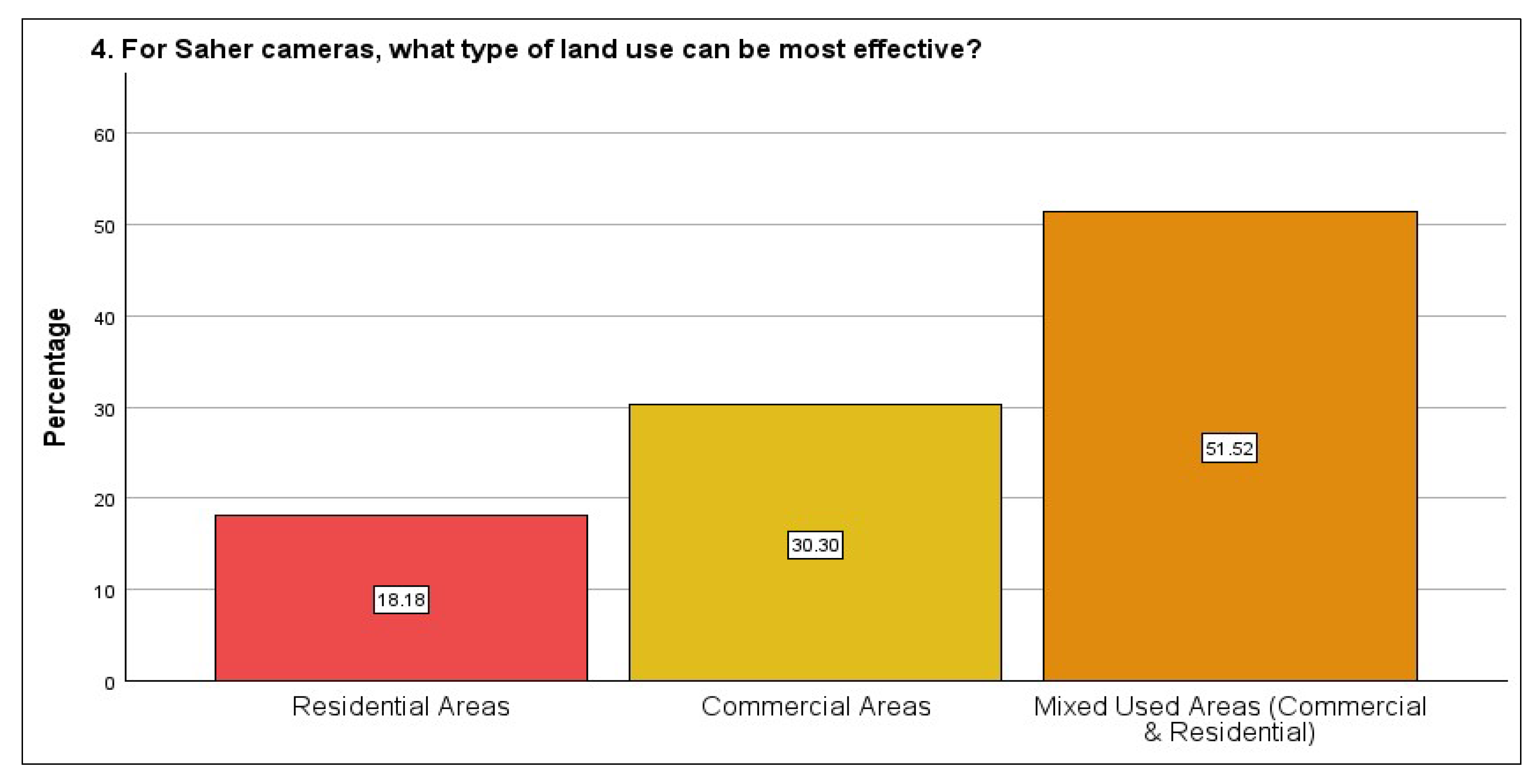

Figure 19 illustrates the suggested road types for priority SAHER camera placements. Experts were also asked to recommend the most suitable land use areas for installing SAHER cameras, as this is crucial for road safety. The results indicated that experts preferred targeting mixed land use areas (51%) rather than focusing solely on residential or commercial zones.

Figure 20 displays the results.

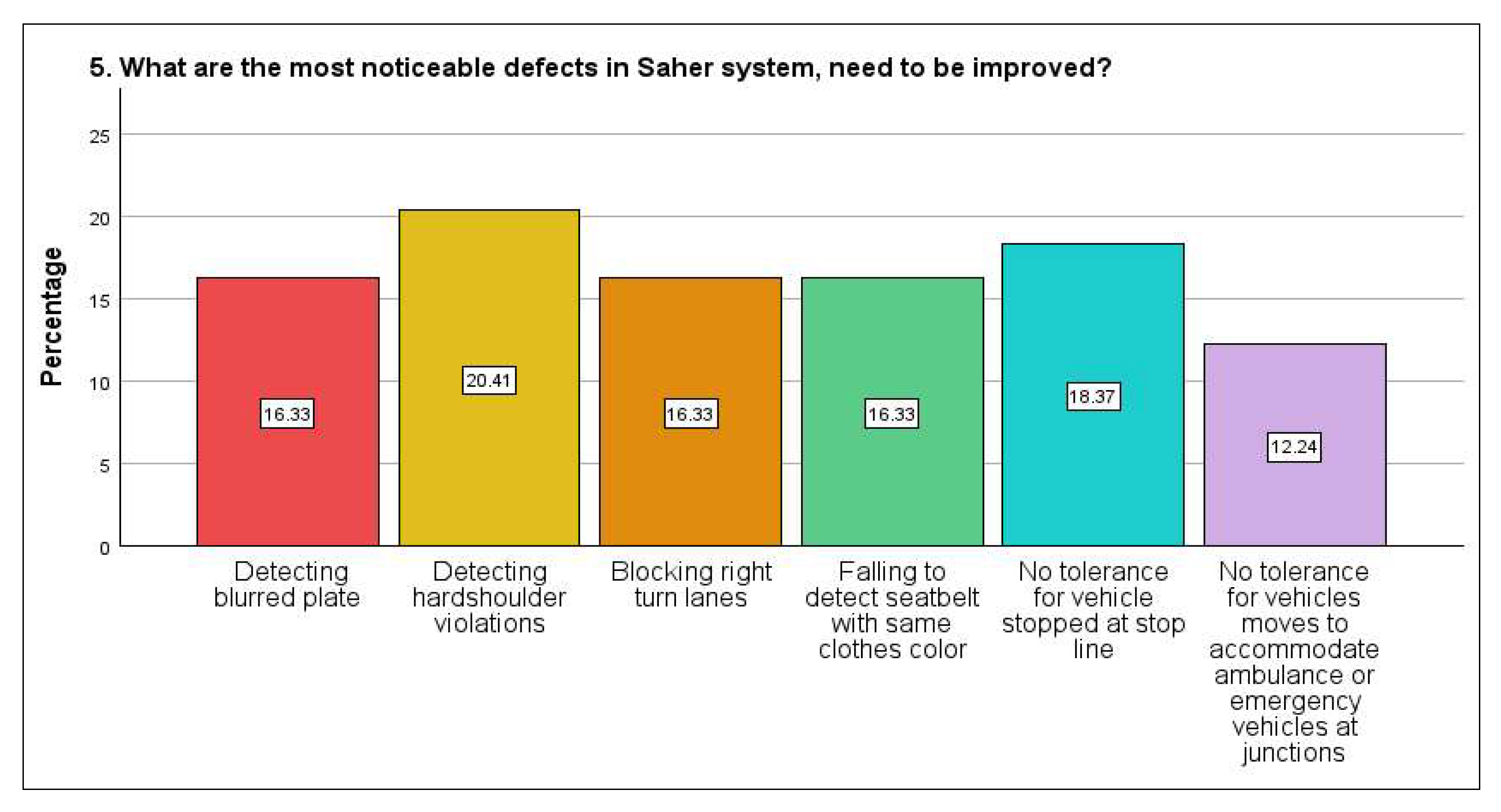

In the fifth question of this section, experts were asked to identify noticeable defects in the SAHER system that could be improved in the future. The results indicated that nearly all of the listed defects were considered highly important by the experts, resulting in similar percentages, as shown in

Figure 21. Lastly, the experts were asked to provide further recommendations that could contribute to the objectives of this study. The following is a summary of the suggestions provided by some of the experts:

The locations for installing SAHER cameras should be clearly identified for the drivers.

It is recommended to maintain a reasonable distance between different speed limits, such as transitioning from 90 to 80, and then to 70, as such changes can confuse drivers.

The presence of undercover police should be increased to address tailgating and aggressive driving.

Long-range radars should be installed on the major highways inside and outside cities.

Automated weigh in motion truck scales should be used on the highways instead of fixed scales.

3.7. Overview of the Analysis of the Collected Data

Based on the results from the experts' questionnaire, it is evident that DMA has sufficient capacity to provide safer roadways for traffic and primarily requires improvements in the operational and maintenance aspects of the existing roadway infrastructure.

Figure 22 shows a summary of the probable causes of road accidents and potential recommendations from experts. Distraction, speeding and sudden lane changes are the highest cause of accidents in the opinion of the experts, and it correlates with their opinion regarding young drivers who are more prone to these accidents. Typically, these causes are common traits of young and novice drivers and therefore experts gave their recommendations to cater for such violations and causes of accidents. Some of the popular recommendations include strong enforcement and additional violations to be considered within SAHER system.

When it comes to the SAHER system, majority of the expert showed their satisfaction towards the technology with only concern of number of existing cameras inside DMA. Another major takeaway from this section analysis was that as high as 75% experts recommended rotation of the camera positions to add more coverage under SAHER program. In terms of overall safety aspects of the SAHER program, experts showed complete faith in the system and think it can make roads safer in DMA. Importantly, experts were of the opinion to integrate undercover police operations with the SAHER program. Also, experts emphasize to put cameras near school and malls for aiding safer pedestrian crossings.

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study involved a comprehensive review of existing literature, followed by an analysis of feedback from 23 experts to examine the effects of the SAHER system on road safety in DMA, as well as the challenges faced by the system, including the state of the road infrastructure. The study seeks to offer a comprehensive evaluation and insights into the camera interventions currently deployed in DMA, focusing on road safety concerns. The results highlight the essential role of the SAHER system in improving urban road safety and emphasize the need to use SAHER for monitoring, analyzing, and enhancing urban traffic conditions. Policymakers and stakeholders in DMA will benefit from the guidelines and recommendations provided in this study, which include:

Development of SAHER coverage policies: Utilize accident and demographic data to minimize impact of unintended socioeconomic disparities on camera placement in DMA. Distribute cameras evenly within DMA, avoiding disproportionate distribution in certain neighborhoods or urban areas. Also, considering work zones, schools and other pedestrian friendly neighborhood under the coverage policy for SAHER program.

Addition of new violations under SAHER program: The SAHER system should add new violations such as hard shoulder driving, blocking right turns into their existing system. In this way, more variations of violations can be targeted.

Establish consistent Evaluation Metrics or KPIs: Defining clear success metrics, such as a reduction in collisions, injuries, and fatalities, and conducting cost-benefit analyses, will help determine long-term success.

Combine Behavioral Interventions: Pair camera enforcement with behavioral change campaigns, such as pedestrian safety initiatives or driver education programs, tailored to the urban context. Publicize the results of studies showing accident reductions to build community trust in camera enforcement systems. Launch education campaigns highlighting the safety benefits of cameras rather than emphasizing punitive measures.

Enhance Legal and Administrative Support: Update traffic laws to support camera-based enforcement, ensuring tickets or penalties issued are enforceable and transparent. Allocate funding for camera maintenance, upgrades, and expansion based on study findings.

Integrate Traffic Infrastructure Measures: Complement camera enforcement with other road infrastructure interventions, such as speed humps, road narrowing, or enhanced signage, in areas where cameras alone are less effective. Pavement marking and advanced warning signs can help improve the overall road safety in DMA as well.

In conclusion, the study discussed in this research article is fully expandable, with numerous possibilities for future research of a similar nature. During the results and analysis phase, it became evident that, despite a considerable number of experts being invited and submitting their responses, there is potential to involve more experts in future studies. Additionally, targeting a larger public sample could yield more reliable results, and future research could include analytical comparisons between the responses of experts and the public.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and A.M.A.; methodology, A.A. and K.M.M.; software, A.A.; validation, A.A., A.M.A. and K.M.M..; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, A.A.; resources, A.A.; data curation, K.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.M.A.; visualization, A.A.; supervision, A.M.A. and K.M.M.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the research are available with the corresponding author and can be furnished upon request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- T. Forum, ITF Research Reports Safer City Streets Global Benchmarking for Urban Road Safety: Global Benchmarking for Urban Road Safety. OECD Publishing, 2018.

- W. H. Organization, Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. World Health Organization, 2018.

- Al-Tit, I. Ben Dhaou, F. M. Albejaidi, and M. S. Alshitawi, “Traffic safety factors in the Qassim region of Saudi Arabia,” Sage Open, vol. 10, no. 2, p. 2158244020919500, 2020.

- W. H. Organization, Global status report on road safety 2018. World Health Organization, 2019.

- S. Singh, “Critical reasons for crashes investigated in the national motor vehicle crash causation survey,” 2015.

- Alqahtany and A. Bin Mohanna, “Housing challenges in Saudi Arabia: the shortage of suitable housing units for various socioeconomic segments of Saudi society,” Housing, Care and Support, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 162–178, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M. Tauhidur Rahman, H. M. Al-Ahmadi, I. Ullah, and M. Zahid, “Intelligent intersection control for delay optimization: Using meta-heuristic search algorithms,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1896, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Turki, A. Jamal, H. M. Al-Ahmadi, M. A. Al-Sughaiyer, and M. Zahid, “On the potential impacts of smart traffic control for delay, fuel energy consumption, and emissions: An NSGA-II-based optimization case study from Dhahran, Saudi Arabia,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 18, p. 7394, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Ansari, F. Akhdar, M. Mandoorah, and K. Moutaery, “Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia,” Public Health, vol. 114, no. 1, pp. 37–39, 2000. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Mohamed, “Estimation of socio-economic cost of road accidents in Saudi Arabia: Willingness-to-pay approach (WTP),” Advances in Management and Applied Economics, vol. 5, no. 3, p. 43, 2015.

- H. M. Al-Ahmadi, “Analysis of Traffic Accidents in Saudi Arabia: Safety Effectiveness Evaluation of SAHER Enforcement System,” Arab J Sci Eng, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 5493–5506, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Goldenbeld and I. van Schagen, “The effects of speed enforcement with mobile radar on speed and accidents: An evaluation study on rural roads in the Dutch province Friesland,” Accid Anal Prev, vol. 37, no. 6, pp. 1135–1144, 2005. [CrossRef]

- W. Soole, B. C. Watson, and J. J. Fleiter, “Effects of average speed enforcement on speed compliance and crashes: A review of the literature,” Accid Anal Prev, vol. 54, pp. 46–56, 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Mountain, W. M. Hirst, and M. J. Maher, “Are speed enforcement cameras more effective than other speed management measures?: The impact of speed management schemes on 30 mph roads,” Accid Anal Prev, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 742–754, 2005. [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, S. Daniels, T. Brijs, E. Hermans, and G. Wets, “Automated section speed control on motorways: An evaluation of the effect on driving speed,” Accid Anal Prev, vol. 73, pp. 313–322, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Lave, “Speeding, coordination, and the 55 mph limit,” Am Econ Rev, vol. 75, no. 5, pp. 1159–1164, 1985.

- Claros, C. Sun, and P. Edara, “Safety effectiveness and crash cost benefit of red light cameras in Missouri,” Traffic Inj Prev, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 70–76, 2017.

- M. Zahid, A. Jamal, Y. Chen, T. Ahmed, and M. Ijaz, “Predicting red light running violation using machine learning classifiers,” in Green Connected Automated Transportation and Safety: Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Green Intelligent Transportation Systems and Safety, Springer, 2022, pp. 137–148. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Al Turki, “How can Saudi Arabia use the Decade of Action for Road Safety to catalyse road traffic injury prevention policy and interventions?,” Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 397–402, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. AlQahtany and I. R. Abubakar, “Public perception and attitudes to disaster risks in a coastal metropolis of Saudi Arabia,” International journal of disaster risk reduction, vol. 44, p. 101422, 2020. [CrossRef]

- AlQahtany, “Evaluating the demographic scenario of gated communities in Dammam metropolitan area, kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” Housing, Care and Support, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 13–30, 2022.

- A. Aboukorin and F. S. Al-shihri, “Rapid Urbanization and Sustainability in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Dammam Metropolitan Area,” J Sustain Dev, vol. 8, no. 9, p. 52, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- U. Lawal Dano and A. Muflah Alqahtany, “ISSUES UNDERMINING PUBLIC TRANSPORT UTILIZATION IN DAMMAM CITY, SAUDI ARABIA: AN EXPERT-BASED ANALYSIS,” 2019.

- Sharqia Development Authority, “Sharqia Land of Prosperity,” 2024.

- B. Thomas, “The role of purposive sampling technique as a tool for informal choices in a social Sciences in research methods,” Just Agriculture, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 1–8, 2022.

Figure 1.

Map of DMA, Saudi Arabia [

23].

Figure 1.

Map of DMA, Saudi Arabia [

23].

Figure 2.

ERSDM 2024 Year Road Network [

24].

Figure 2.

ERSDM 2024 Year Road Network [

24].

Figure 3.

Feeling safer while driving in DMA.

Figure 3.

Feeling safer while driving in DMA.

Figure 4.

Opinion regarding roadway infrastructure in DMA.

Figure 4.

Opinion regarding roadway infrastructure in DMA.

Figure 5.

Opinion regarding highway accesses in DMA.

Figure 5.

Opinion regarding highway accesses in DMA.

Figure 6.

Opinion regarding traffic signs and lane markings in DMA.

Figure 6.

Opinion regarding traffic signs and lane markings in DMA.

Figure 7.

Opinion regarding traffic signal operations in DMA.

Figure 7.

Opinion regarding traffic signal operations in DMA.

Figure 8.

Opinion regarding role of traffic police in road safety.

Figure 8.

Opinion regarding role of traffic police in road safety.

Figure 9.

Opinion regarding coverage (presence) of traffic police in DMA.

Figure 9.

Opinion regarding coverage (presence) of traffic police in DMA.

Figure 10.

Major reasons for the Road accident in DMA.

Figure 10.

Major reasons for the Road accident in DMA.

Figure 11.

Age group likely to be involved in Road Accidents.

Figure 11.

Age group likely to be involved in Road Accidents.

Figure 12.

Opinion regarding results of SAHER in DMA.

Figure 12.

Opinion regarding results of SAHER in DMA.

Figure 13.

Opinion regarding number of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 13.

Opinion regarding number of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 14.

Opinion regarding types of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 14.

Opinion regarding types of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 15.

Opinion regarding locations of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 15.

Opinion regarding locations of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 16.

Opinion regarding frequently changing location of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 16.

Opinion regarding frequently changing location of SAHER cameras in DMA.

Figure 17.

Suggested improvements in SAHER program.

Figure 17.

Suggested improvements in SAHER program.

Figure 18.

Suggested new violations in SAHER program.

Figure 18.

Suggested new violations in SAHER program.

Figure 19.

Suggested roadways for installation of SAHER cameras.

Figure 19.

Suggested roadways for installation of SAHER cameras.

Figure 20.

Suggested land use for installation of SAHER cameras.

Figure 20.

Suggested land use for installation of SAHER cameras.

Figure 21.

Noticeable defects in SAHER system.

Figure 21.

Noticeable defects in SAHER system.

Figure 22.

Probable causes of accidents in DMA.

Figure 22.

Probable causes of accidents in DMA.

Table 1.

Demographic Details of the Respondents.

Table 1.

Demographic Details of the Respondents.

| Characteristics |

Categories |

Absolute values |

Percentages |

| Age (years) |

30–40 |

6 |

26.1% |

| |

41–50 |

8 |

34.8% |

| |

51–60 |

5 |

21.7% |

| |

Above 60 |

4 |

17.4% |

| Gender |

Male |

23 |

100% |

| |

Female |

0 |

0.0% |

| Nationality |

Saudi |

18 |

78.3% |

| |

Non-Saudi |

5 |

21.7% |

| Educational level |

Bachelor's |

6 |

26.1% |

| |

Master's |

6 |

26.1% |

| |

Doctorate |

10 |

43.5% |

| |

Other |

1 |

4.3% |

| Employment |

Private |

6 |

26.1% |

| |

Government/Public |

11 |

47.8% |

| |

Security Forces |

2 |

8.7% |

| |

Retired |

4 |

17.4% |

| Experience (years) |

10-15 years |

7 |

30.4% |

| |

16-20 years |

2 |

8.7% |

| |

21-25 years |

4 |

17.4% |

| |

More than 25 years |

10 |

43.5% |

| Driving experience (years) |

Less than 10 years |

2 |

8.7% |

| |

10-15 years |

3 |

13.0% |

| |

16-20 years |

2 |

8.7% |

| |

21-25 years |

2 |

8.7% |

| |

More than 25 years |

14 |

60.9% |

| Residence in DMA |

Yes |

18 |

78.3% |

| |

No |

5 |

21.7% |

Table 2.

Cross table analysis for age group and major causes of accidents.

Table 2.

Cross table analysis for age group and major causes of accidents.

| |

Q1. In your opinion, what are the major causes of Road Accidents in DMA? |

| Speeding |

Using of cellphones while driving |

Sudden lane changes |

Violating traffic signals |

Driving opposite direction |

Other causes |

| Q2. In your opinion, which age group may be more likely to cause road accidents? |

Under 17 (Illegal) |

5% |

6% |

3% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

| 17-25 years |

13% |

16% |

12% |

2% |

2% |

3% |

| 26-35 years |

9% |

9% |

5% |

1% |

1% |

3% |

| 36-45 years |

1% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

| 46-60 years |

0% |

0% |

1% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

| Above 60 years |

1% |

1% |

1% |

0% |

0% |

0% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).