Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

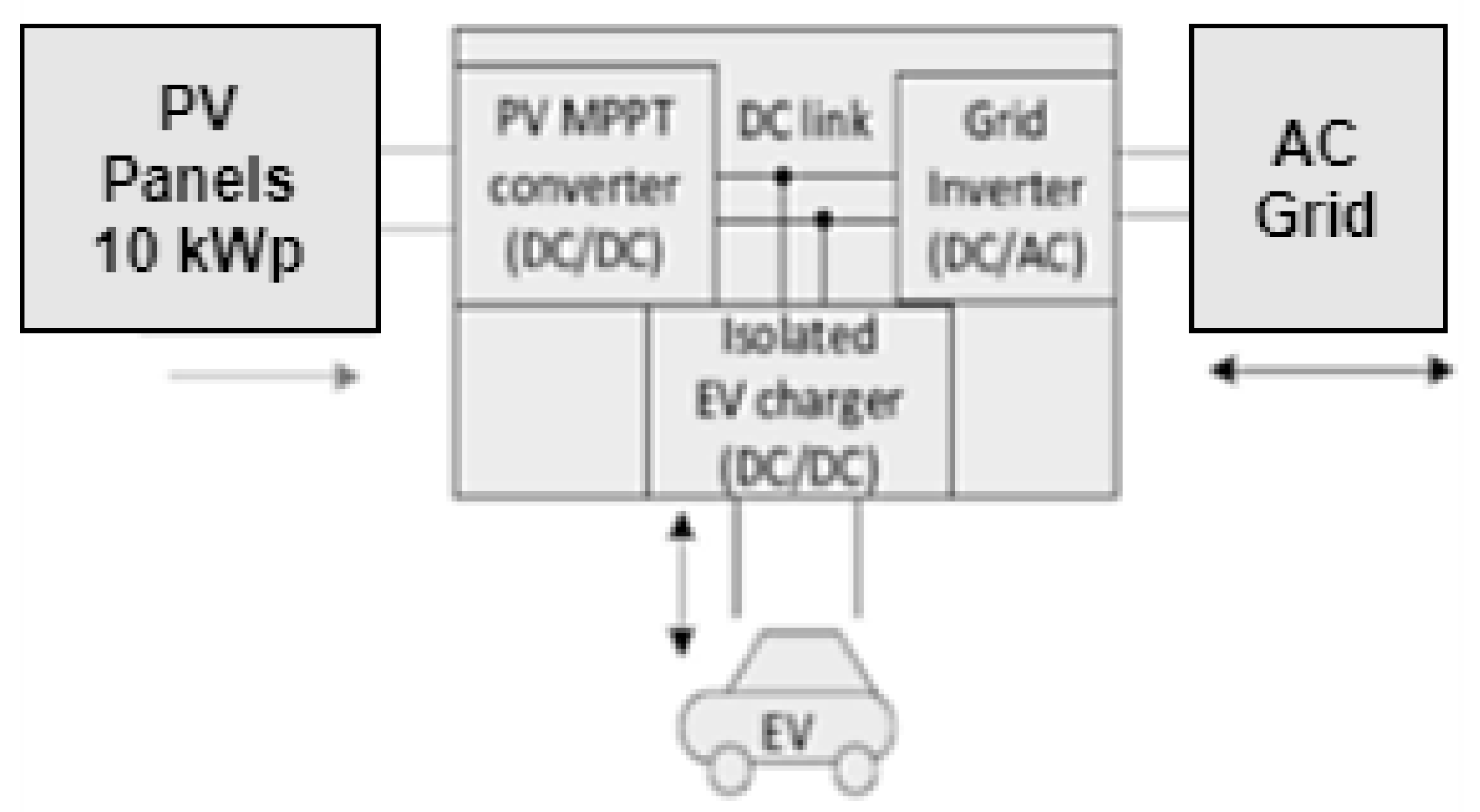

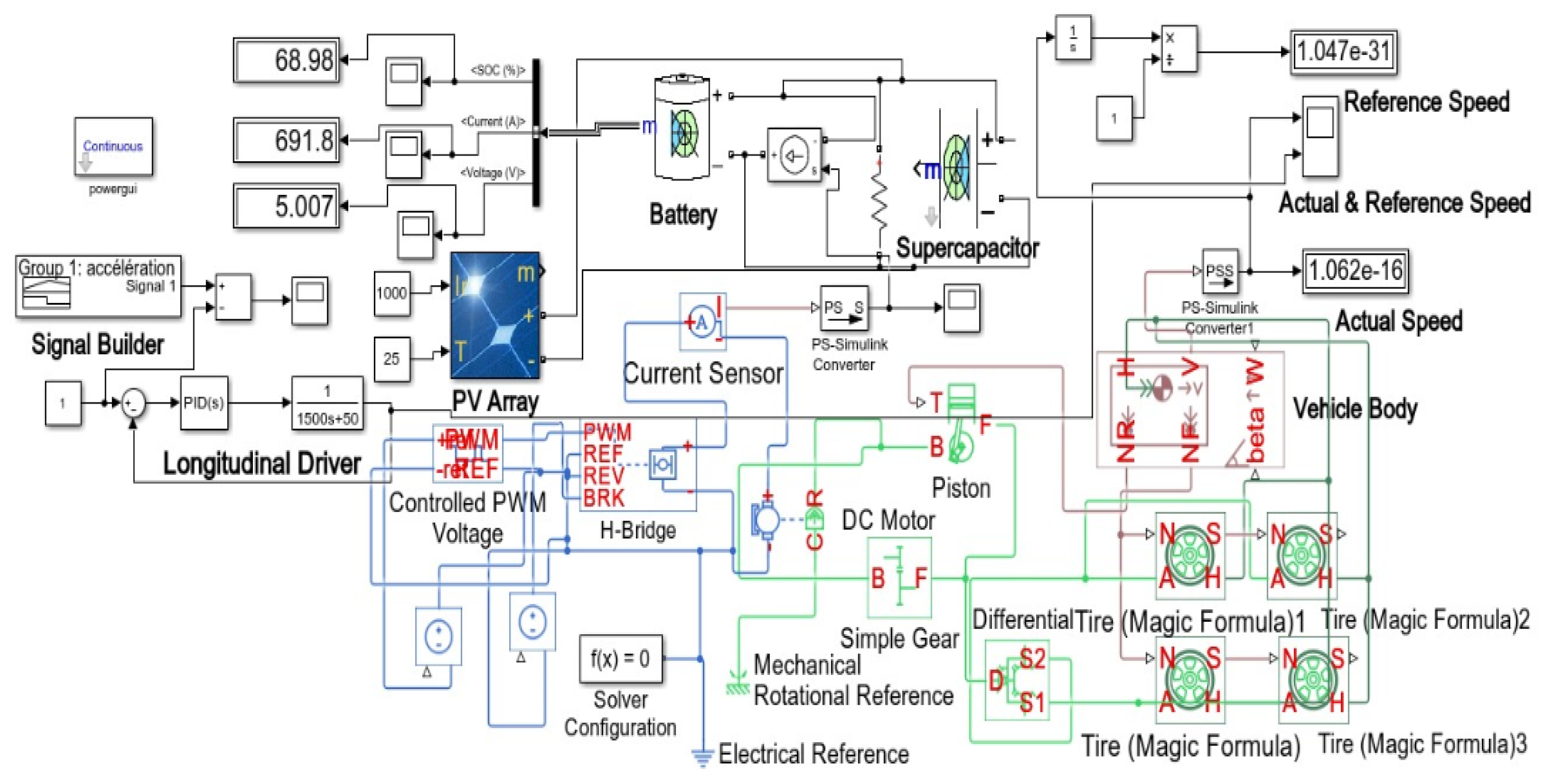

This paper explores an innovative approach to optimize the energy management of hybrid vehicles by integrating regenerative braking and solar panels. Regenerative braking recovers kinetic energy during braking, reducing the dependence on mechanical energy sources, while solar panels convert solar energy to power the electric propulsion system. The study uses computer models and simulations to look at an advanced hybrid system. It focuses on the hybrid inverter and optimization algorithms, like the maximum power tracking (MPPT) algorithm to get the most power from the sun and genetic algorithms to make the best use of energy. Controls like pulse width modulation (PWM) and proportional integral (PI) are used to improve system performance. The vehicle performance is evaluated under various driving conditions, considering variables such as speed, battery charge, current, voltage, acceleration, and flux. Results show that the integration of these technologies reduces fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to sustainable mobility. This work provides practical recommendations for the automotive industry to promote hybrid vehicles with advanced energy solutions.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Hybrid System Description

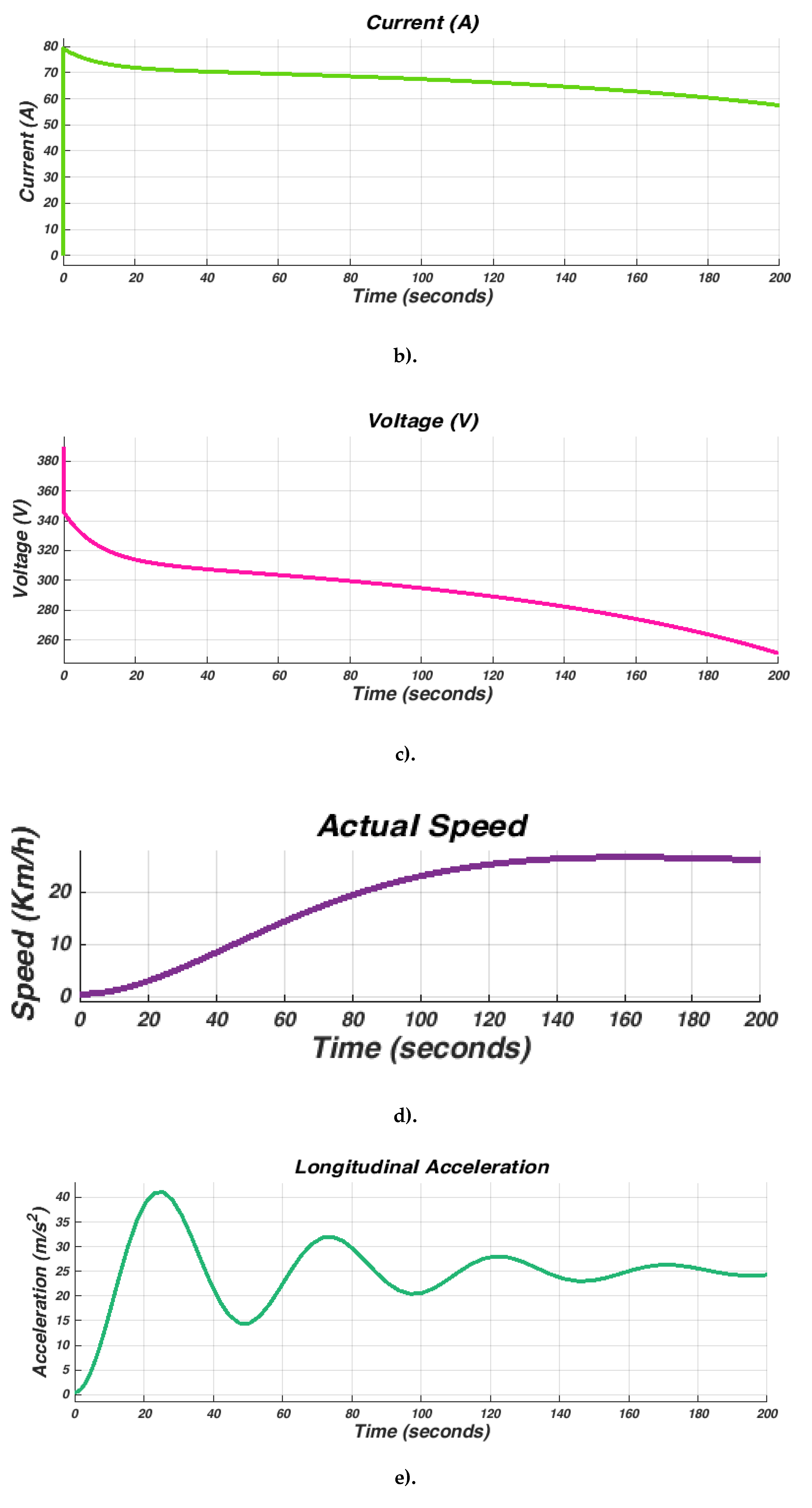

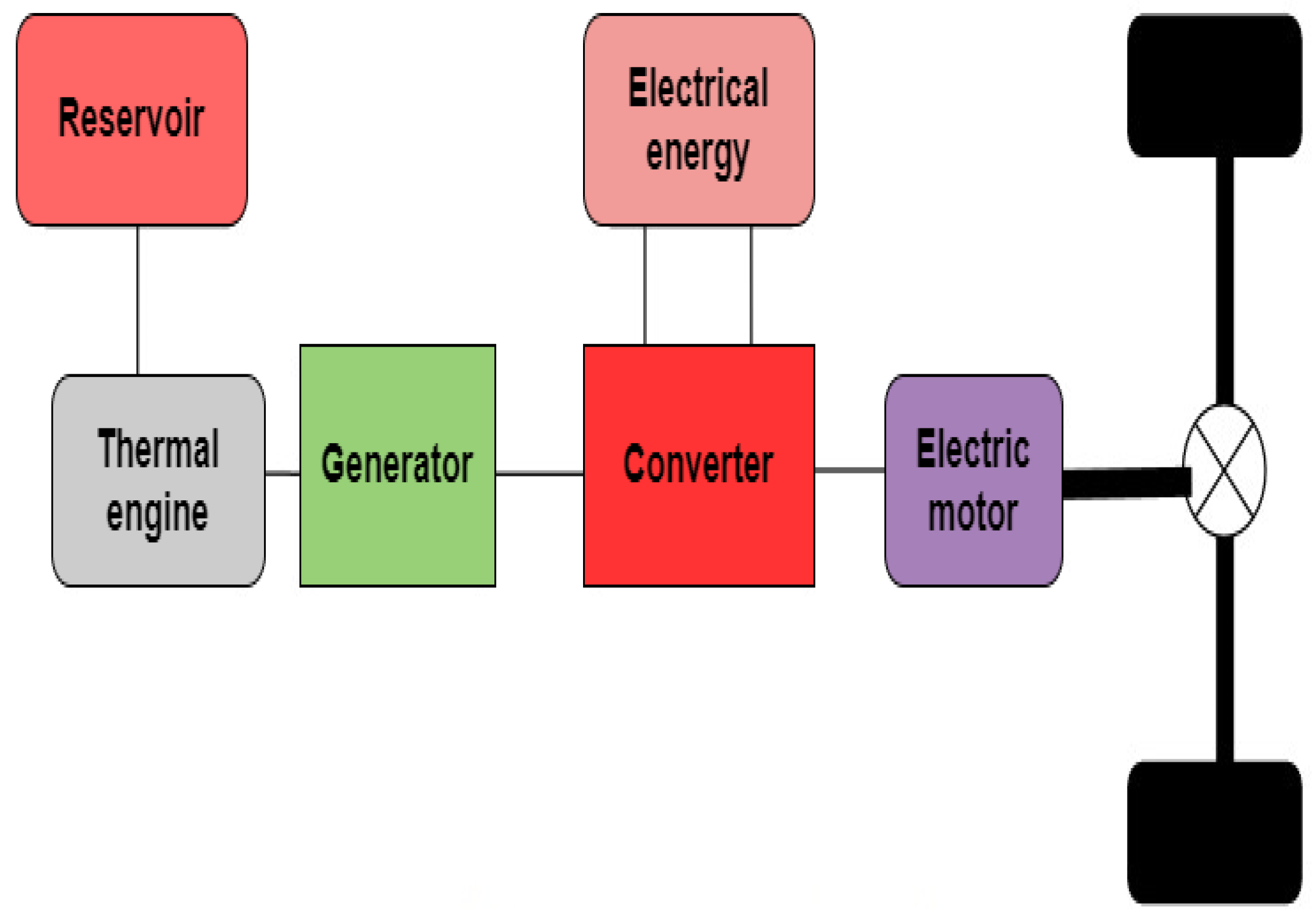

2.1.1. Block Diagram

2.2. Different Categories of Vehicle Hybridization

2.2.1. Electric Hybridization Range

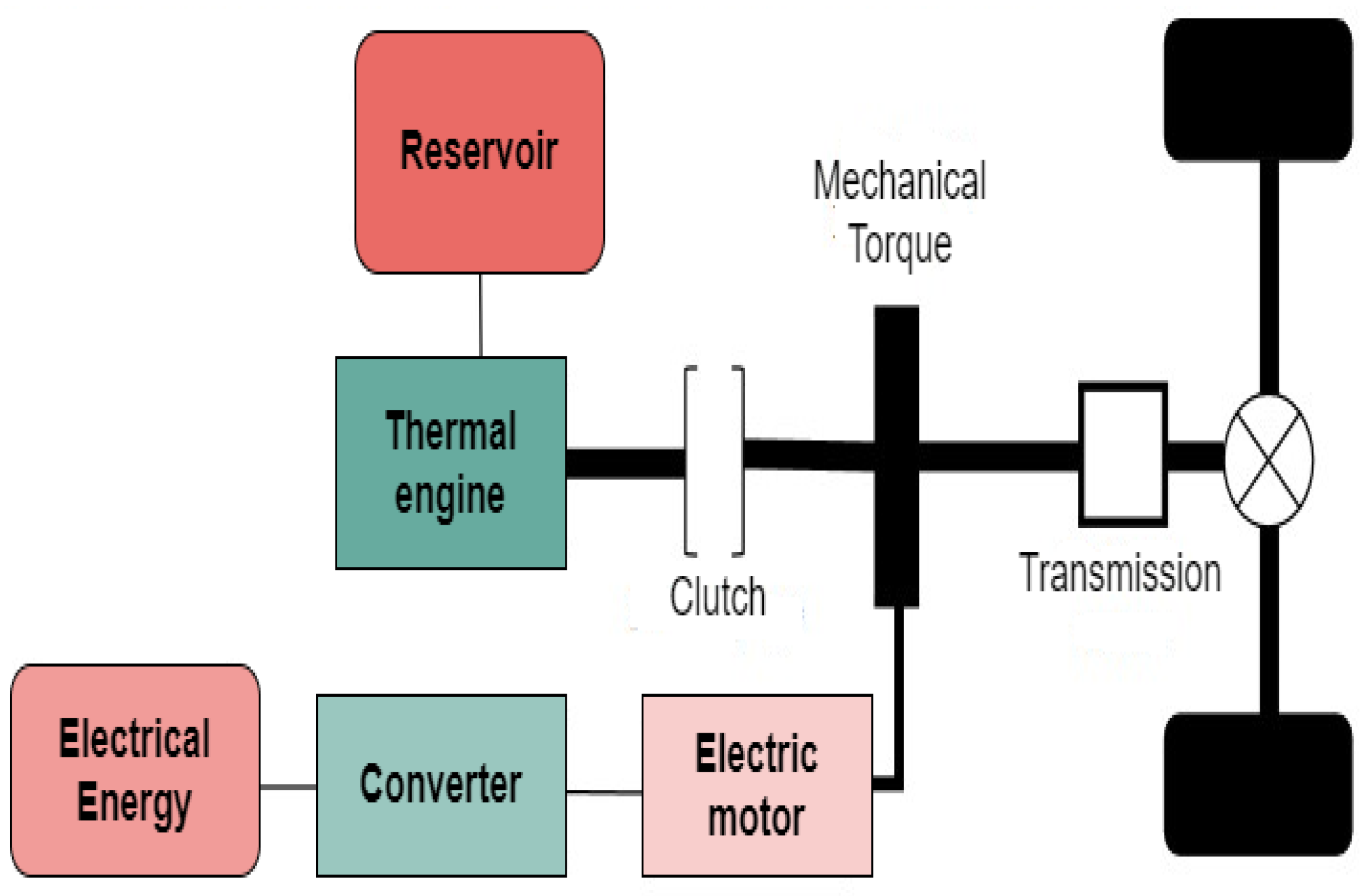

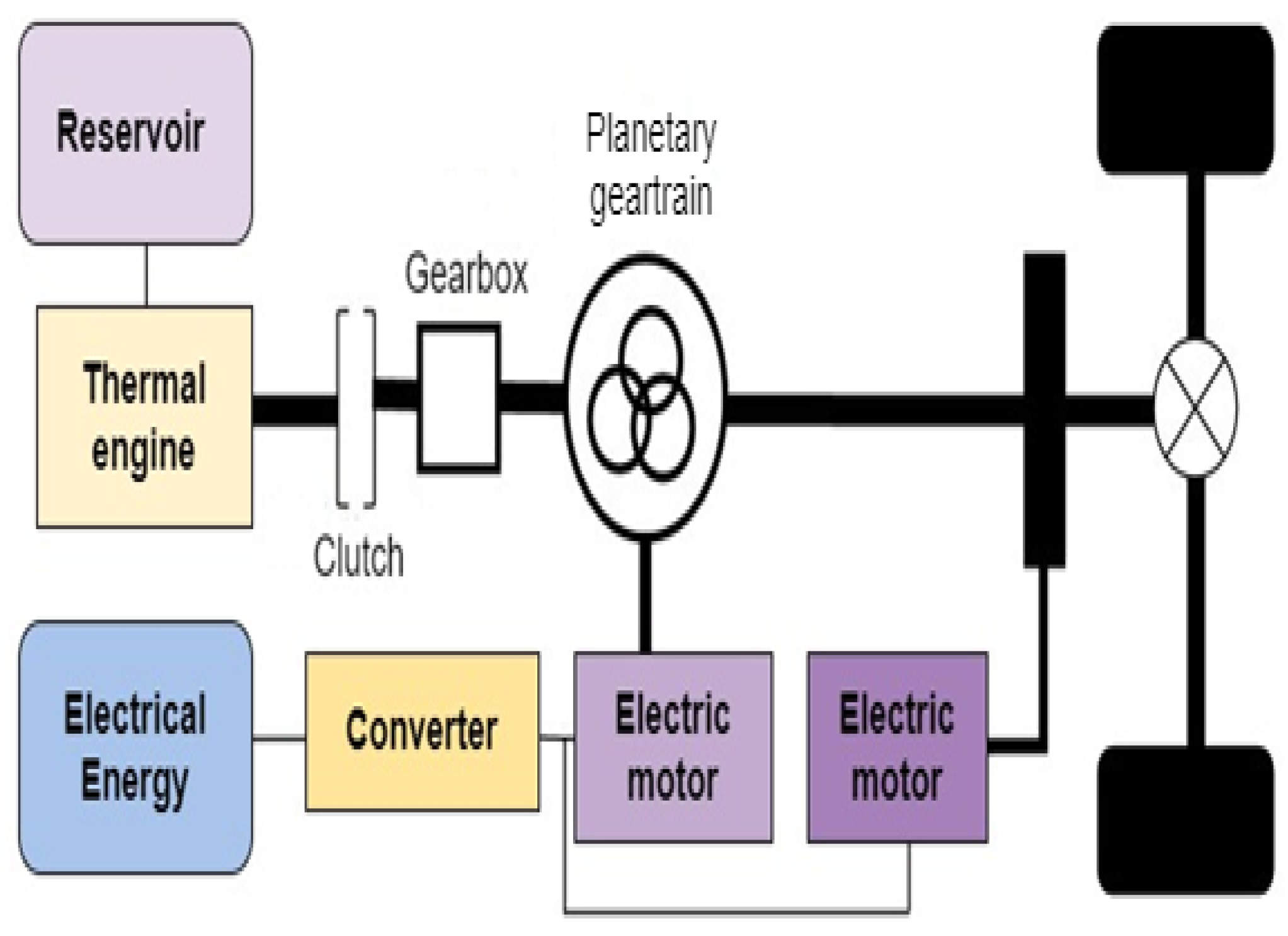

2.1.2. Hybrid Electric Architecture

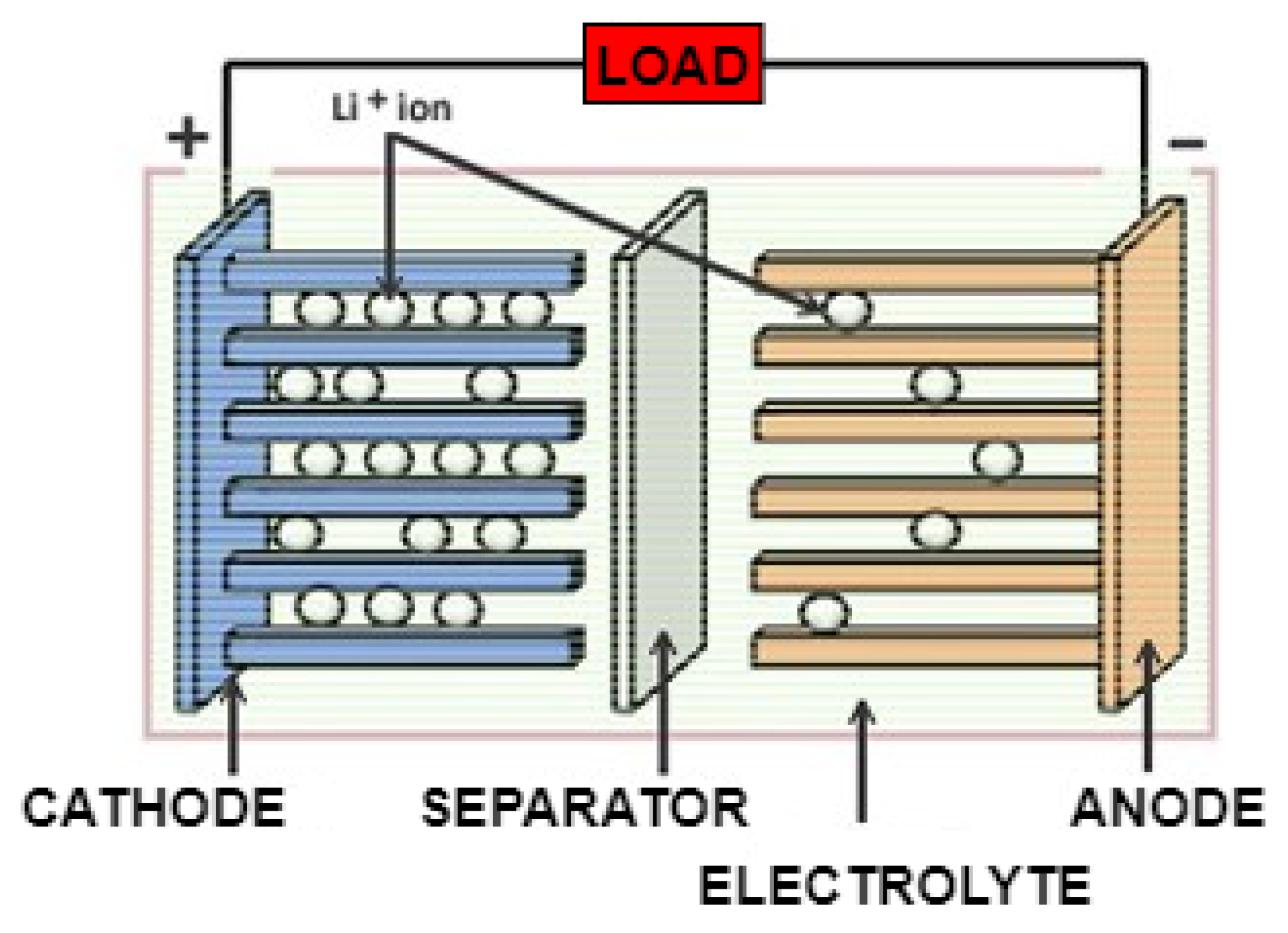

2.1.3. Components of Hybrid Vehicles

2.3. Integrated Energy Optimization Approach for Parallel Hybrid Vehicles

2.3.1. Proportional Integral (PI) Controller

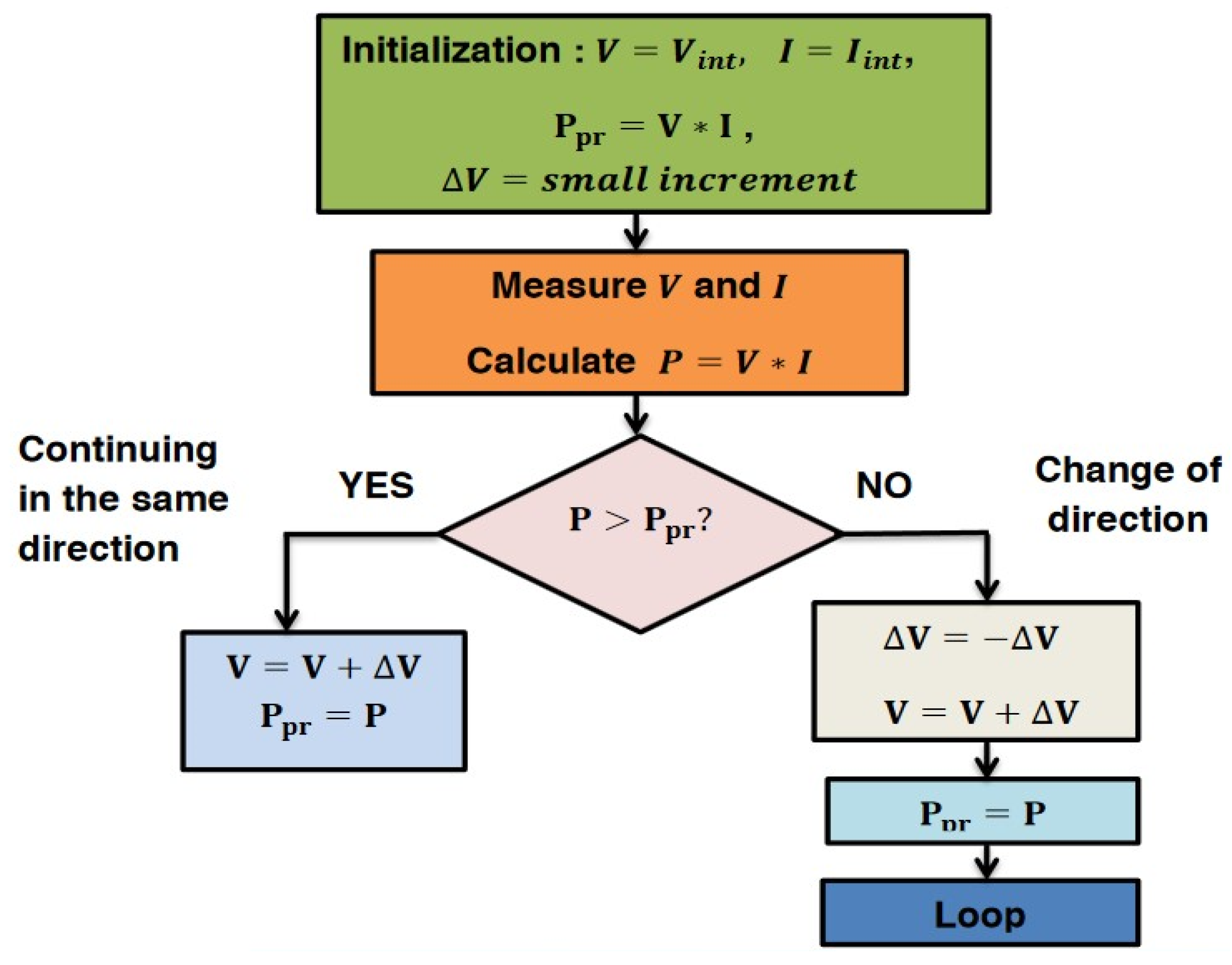

2.3.2. Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) Algorithm

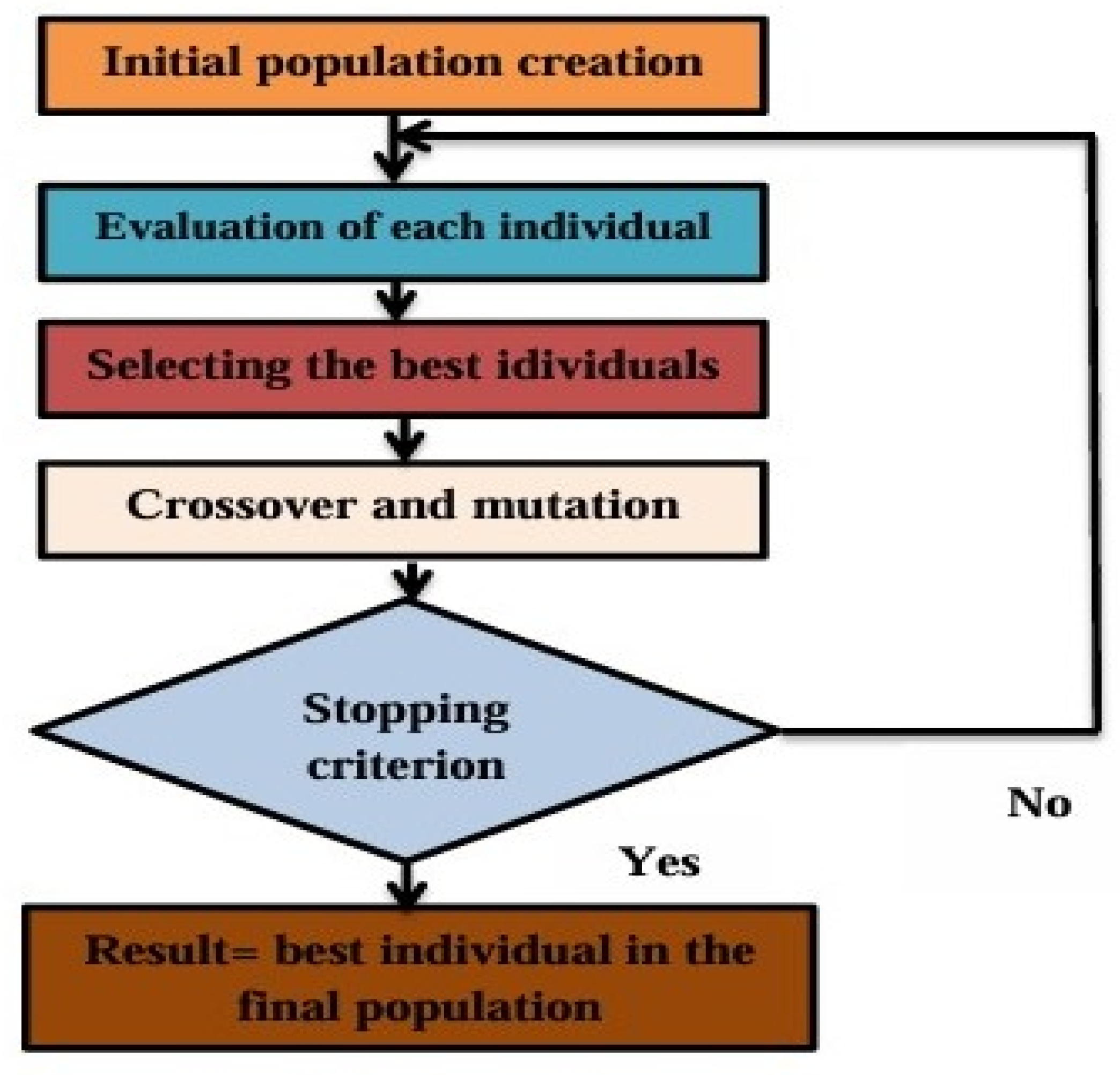

2.3.3. Genetic Algorithms (GA)

2.3.4. Pulse Width Modulation (PWM)

2.3.5. Integration Logic

3. Results

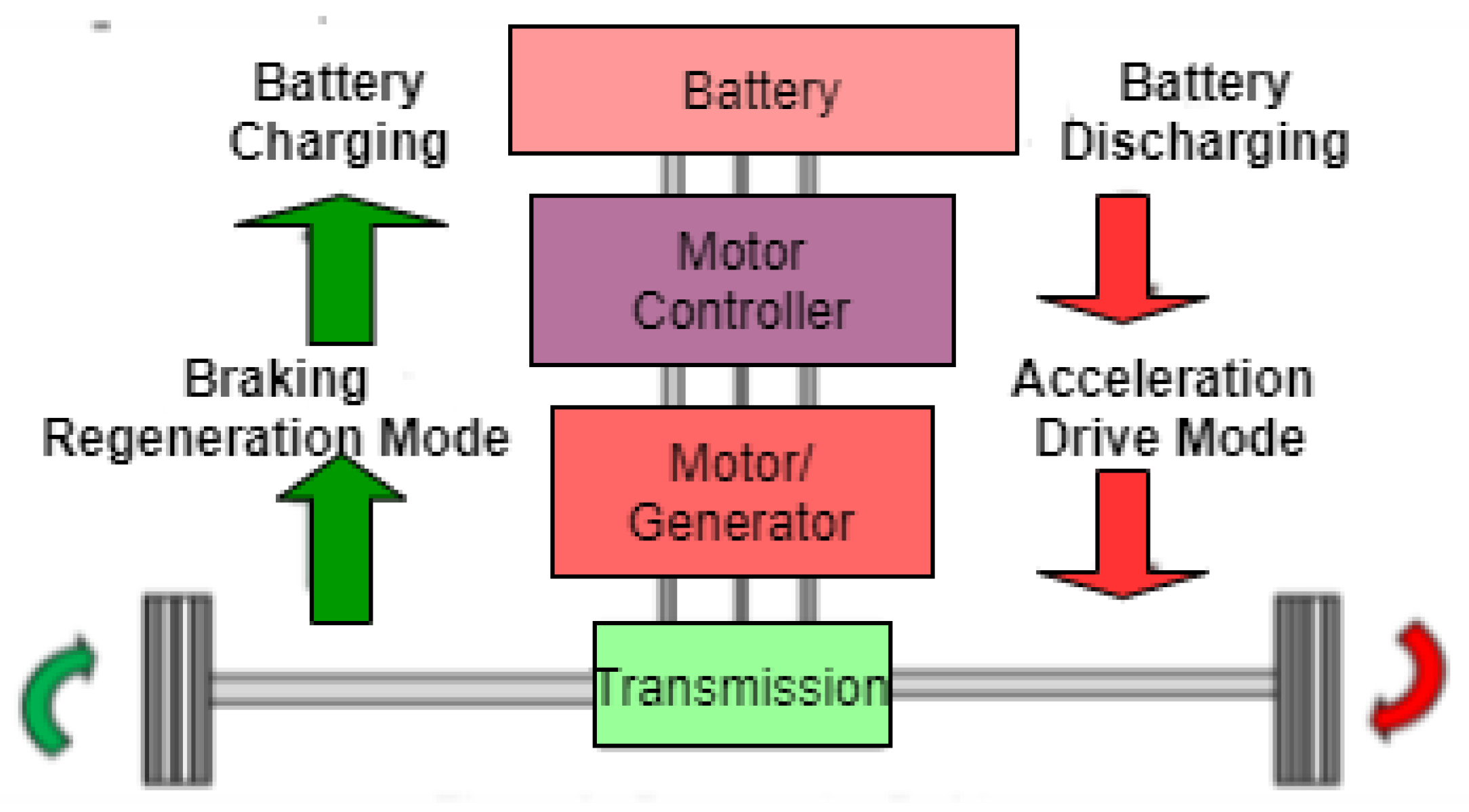

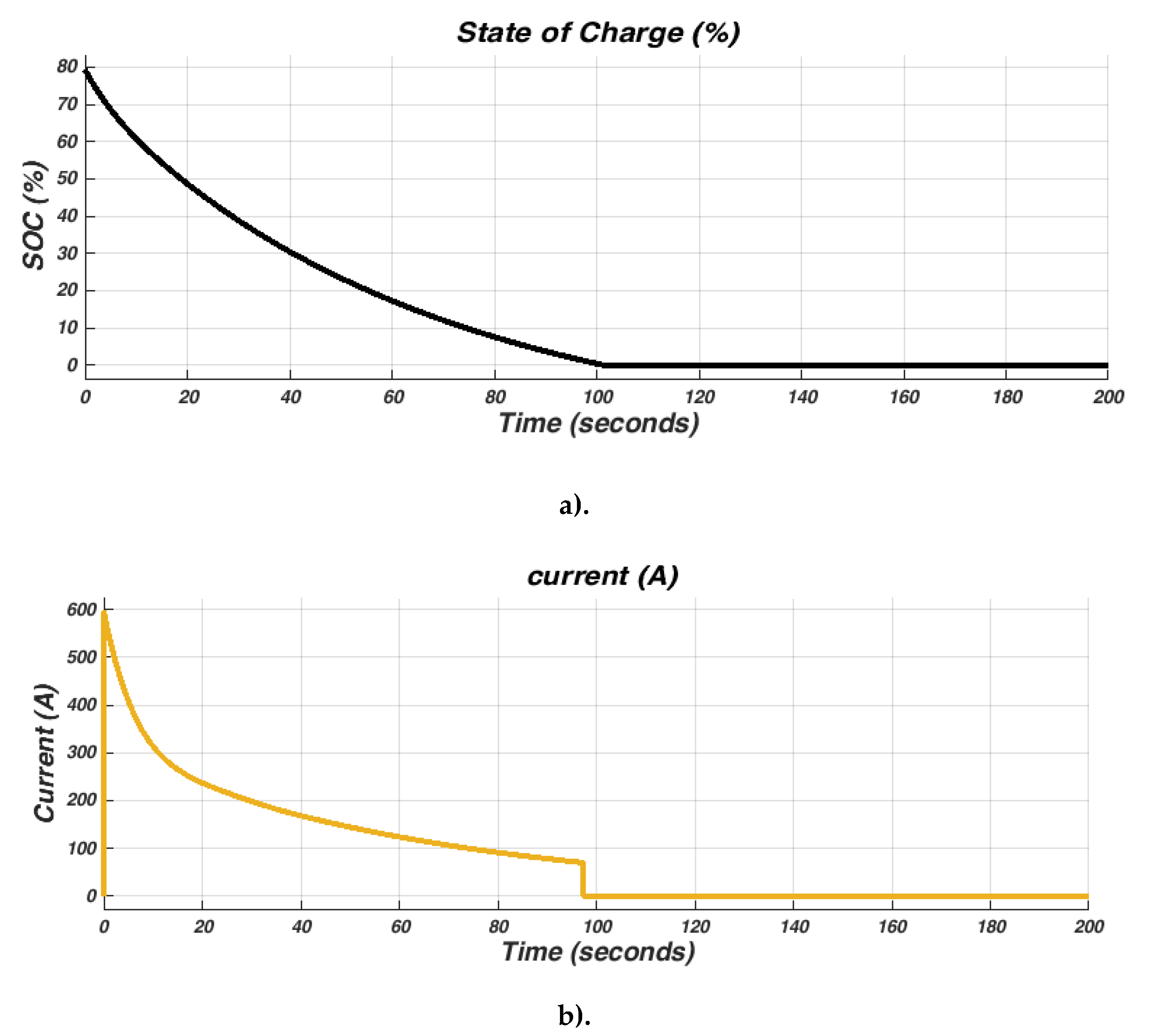

4.3. Regenerative Braking

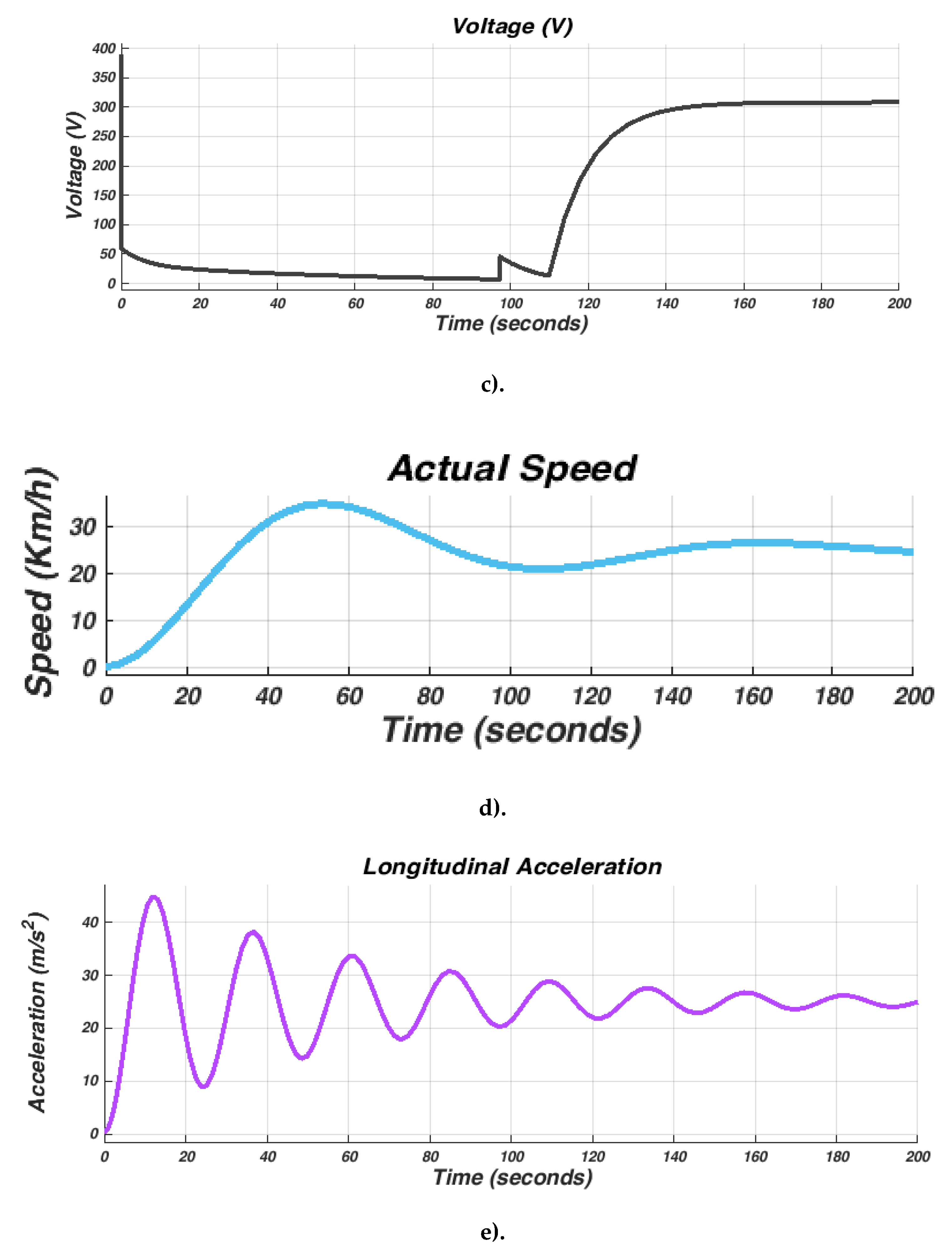

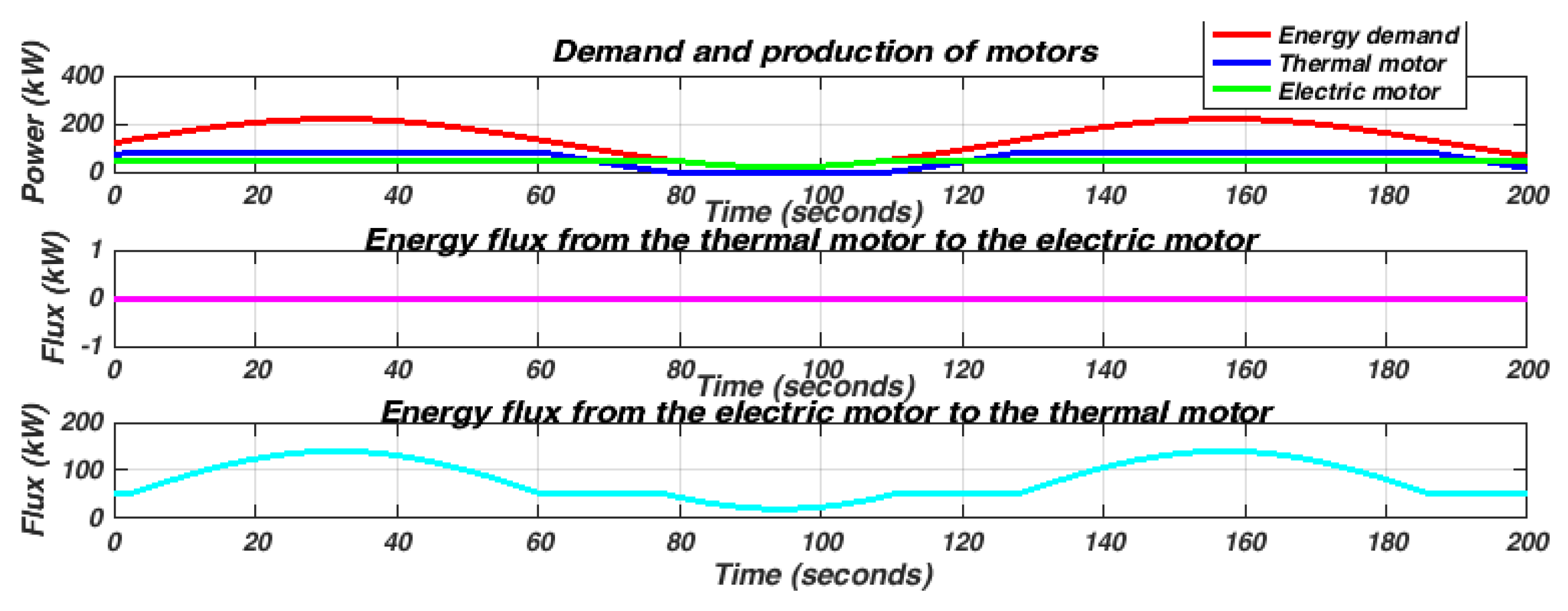

4.4. The Energy Flow Between the Different Motors

4. Discussion

| Controller Gains | Without GA | With GA |

|---|---|---|

| Kp | 2.48 | 3.612 |

| Ki | 22.433 | 0.936 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MPPT | Maximum Power Point Tracking |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| PI | Proportional Integral |

| PWM | Pulse Width Modulation |

References

- N. Moubayed et F. Chehadi, ENERGY MANAGEMENT IN A PARALLEL HYBRID VEHICLE, vol. IX, janv. 2013.

- Y. Arıkuşu, N. Bayhan, et H. Tiryaki, Investigation With Rule-Based Controller of Energy Consumption of Parallel Hybrid Vehicle Model in Different States of Charge, ELECTRICA, vol. 24, p. 183-192, janv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Delprat, J. Bernard, et T.-M. Guerra, Stratégie de commande pour véhicule hybride parallèle., janv. 2005.

- D. Cabezuelo, J. Andreu, I. Kortabarria, Í. Alegría, et E. Robles, Powertrain systems of electric, hybrid and fuel-cell vehicles: State of the technology, juin 2017, p. 1445-1450. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Cikanek et K. E. Bailey, Regenerative braking system for a Hybrid Electric Vehicle, présenté à Proceedings of the American Control Conference, févr. 2002, p. 3129-3134 vol.4. [CrossRef]

- S. Hosseini, M. Soleymani, S. Kelouwani, et A. Amamou, Energy Recovery and Energy Harvesting in Electric and Fuel Cell Vehicles, a Review of Recent Advances, IEEE Access, vol. PP, p. 1-1, janv. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Seok, B. Han, S.-H. Kim, J.-G. Lee, et M. Kim, Rippleless resonant boost converter for fuel-cell power conditioning systems, in 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), mars 2018, p. 653-658. [CrossRef]

- SA. Goel, V. Rajput, S. Bajaj, R. Mittal, A. Dube, et Ruchika, Solar hybrid electric vehicle — A green vehicle for future impulse, 2016 3rd Int. Conf. Comput. Sustain. Glob. Dev. INDIACom, mars 2016.

- J. Merin et al., Hybrid MPPT Solar-Wind Electric Vehicle With Automatic Battery Switching, nov. 2018, p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- B. Prasad, T. Devi, V. Nookaraju, D. Sai, et P. Kumar, Modelling and Simulation of Solar Powered Hybrid Electric Vehicle, avr. 2023, p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- G. Rizzo, I. Arsie, M. Sorrentino, G. Rizzo, I. Arsie, et M. Sorrentino, Hybrid Solar Vehicles, in Solar Collectors and Panels, Theory and Applications, IntechOpen, 2010. [CrossRef]

- K. Mohan, S. Sankaranarayanan, S. S. D. Prasad, V. Sivasubramaniam, et V. Sairam, Solar powered Hybrid vehicle, IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng., vol. 390, no 1, p. 012102, juill. 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Ning, J. Wang, Y. Yin, J. Shangguan, N. Bao, et N. Li, Regenerative Braking Algorithm for Parallel Hydraulic Hybrid Vehicles Based on Fuzzy Q-Learning, Energies, vol. 16, p. 1895, févr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Millet et J.-C. Heudin, Comparison between Three Heuristic Algorithms to Repair a Large-Scale MIMD Computer, in Evolvable Systems: From Biology to Hardware, J. Miller, A. Thompson, P. Thomson, et T. C. Fogarty, Éd., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2000, p. 145-154. [CrossRef]

- R. Gianfranco et al., A prototype car converted to solar hybrid: project advances and road tests, IFAC-Pap., vol. 55, no 24, p. 329-334, janv. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. C. P. Selvan, S. R. Madara, S. R. Pillai, et R. Vandanapu, Solar hybrid vehicles for environmental protection, in 2018 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), févr. 2018, p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Tiano, G. Rizzo, G. De Feo, et S. Landolfi, Converting a Conventional Car into a Hybrid Solar Vehicle: a LCA Approach, IFAC-Pap., vol. 51, no 31, p. 188-194, janv. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. B. Sankar et R. Seyezhai, Simulation and Implementation of Solar Powered Electric Vehicle, Circuits Syst., vol. 7, no 6, Art. no 6, mai 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. Desai et S. S. Williamson, Optimal design of a parallel Hybrid Electric Vehicle using multi-objective genetic algorithms, in 2009 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference, sept. 2009, p. 871-876. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, G. Xu, Z. Wang, et Y. Xu, A Hybrid Controller Design For Parallel Hybrid Electric Vehicle, in 2007 IEEE International Conference on Integration Technology, mars 2007, p. 450-454. [CrossRef]

- P. G. Anselma et al., Comparing Parallel Hybrid Electric Vehicle Powertrains for Real-world Driving, juill. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Pittet, Modélisation physique d’un transistor de puissance IGBT: traînée en tension à l’enclenchement, janv. 2005. [CrossRef]

- P. Ning, T. Yuan, Y. Kang, C. Han, et L. Li, Review of Si IGBT and SiC MOSFET based on hybrid switch, Chin. J. Electr. Eng., vol. 5, p. 20-29, sept. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Lanzarotto, M. Marchesoni, M. Passalacqua, A. P. Prato, et M. Repetto, Overview of different hybrid vehicle architectures, IFAC-Pap., vol. 51, no 9, p. 218-222, janv. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Jaguemont, L. Boulon, et Y. Dubé, A comprehensive review of lithium-ion batteries used in hybrid and electric vehicles at cold temperatures, Appl. Energy, vol. 164, p. 99-114, févr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- RC aircraft/drone/UAV battery | Products. Accessed: December 15, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://www.pdbattery.com/rc-aircraft-battery.html.

- S. Bolognani, M. Morandin, S. Calligaro, R. Petrella, et A. Pevere, « Bidirectional PMSM drive employing a three level ANPC inverter and a multi-phase interleaved DC/DC converter for hybrid electric vehicles, présenté à Conference Proceedings - IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition - APEC, mars 2014, p. 818-825. [CrossRef]

- F. Mocera, A Model-Based Design Approach for a Parallel Hybrid Electric Tractor Energy Management Strategy Using Hardware in the Loop Technique, Vehicles, vol. 3, p. 1-19, déc. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Morandin, S. Bolognani, et A. Faggion, Active Torque Damping for an ICE-based Domestic CHP System with an SPM Machine Drive, IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 51, p. 1-1, juill. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Welke, M. Ochs, et H.-J. Schmidt-Brücken, Single Shaft Parallel Hybrid Drive System, SAE International, Warrendale, PA, SAE Technical Paper 970286, févr. 1997. [CrossRef]

- Hybrid Solar Inverter SAJ FOR MOTOR VEHICLES. https://tienda-solar.es - Recherche Google. Accessed: July 15, 2024.

- Hybrid inverter | Solar-battery.com, Battery-Solar.Accessed: July 15, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://www.batterie-solaire.com/263-indicateur-hybride.

- N. R. Varma, K. C. Reddy, G. Dhasharatha, V. Manohar, K. K. Kumar, et V. P. Kumar, Hybrid Electrical Vehicle Design by Using Solar and Battery Sources, E3S Web Conf., vol. 472, p. 01006, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Waseem, A. Sherwani, et M. Suhaib, Integration of solar energy in electrical, hybrid, autonomous vehicles: a technological review, SN Appl. Sci., vol. 1, p. 1459, nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. R. Chandra Mouli, P. Bauer, et M. Zeman, System design for a solar powered electric vehicle charging station for workplaces, Appl. Energy, vol. 168, p. 434-443, avr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Rizzo, F. A. Tiano, V. Mariani, et M. Marino, Optimal Modulation of Regenerative Braking in Through-The-Road Hybridized Vehicles, Energies, vol. 14, no 20, Art. no 20, janv. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems, MIT Press. Accessed: July 15, 2024. [Online]. Available at: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262581110/adaptation-in-natural-and-artificial-systems/.

- D. B. Fogel, Artificial Intelligence through Simulated Evolution, IEEE, 2009. [CrossRef]

- H.-P. Schwefel, Numerical Optimization of Computer Models, vol. 33. 1981. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Rolling resistance coefficient | 0.01 |

| Air density (kg/) | 1.3 |

| Vehicle mass m (kg) | 1500 |

| Gravitational acceleration g (m/) | 9.8 |

| Frontal area | 2.8 |

| Aerodynamic friction coefficient | 0.35 |

| Auxiliary system (kW) | 0.5 |

| Vehicle inertia (Kg.m-2) | 2630 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).