1. Introduction

The food and beverage processing industry (hereafter, the F&B industry) plays a vital role in addressing global challenges, including meeting the demands of a growing population, responding to shifting consumer preferences, and ensuring sustainability in food production. The industry faces mounting environmental criticism due to the substantial liquid and solid waste generated by food processing (Galanakis, 2021). Moreover, it is widely regarded as energy-intensive due to the significant energy demands of refrigeration and freezing for perishable goods, as well as the continuous reliance on processes such as baking, frying, and other thermal treatments. These challenges demand innovative solutions that enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and improve waste management (Acosta et al., 2011).

Eco-innovation (EI) has emerged as a key strategy for the industry, transcending compliance with environmental regulations to deliver economic and competitive benefits. EI enables firms to reduce energy and material costs, differentiate products, and enhance international competitiveness (Bossle et al., 2016; Galera-Quiles et al., 2021; Losada et al., 2019). However, EI presents unique challenges, such as higher costs for green products and consumer resistance to novelty (Arranz et al., 2019). The economic benefits of EI are not guaranteed, often requiring firms to invest heavily in R&D and marketing, particularly in this traditionally conservative industry (Cai & Li, 2018; Galizzi & Venturini, 1996). While EI consistently benefits the planet and human health, its economic implications are not always positive for the innovating firm (Cai & Li, 2018; Calle et al., 2022; Ghisetti, 2017) and may even be negative in the short term (Blind, 2012).

Although EI is increasingly studied, the literature remains focused on high-tech sectors, leaving resource-intensive industries like F&B underexplored (Ben Amara & Chen, 2022; Horbach, 2016). Additionally, most existing studies are cross-sectional, neglecting the dynamic nature of innovation over time. Scholars have called for long-term analyses to better understand the evolution of EI and its drivers (Bossle et al., 2016; Cai & Li, 2018; Díaz-García et al., 2015; Hojnik & Ruzzier, 2016; Park et al., 2017; Marzucchi & Montresor, 2017; Triguero et al., 2018). After reviewing the literature on EI, Follmann et al. (2024) recommend that scholars place greater emphasis on dynamic, crisis-related perspectives, particularly on how uncertainties arising from crises affect sustainability in agro-food firms. As Stoneman (1995, p. 6) noted, “clearly, the analysis of technological change must be dynamic and as such involve time.” Such analyses are essential for examining how eco-innovative firms adapt to changing economic conditions, including the impact of crises (Le Bas & Poussing, 2018; Suárez, 2014).

Spain, with its large and resource-intensive F&B sector, offers a compelling context for studying the dynamics of EI. The sector represents 24% of manufacturing turnover, with 97% of firms classified as SMEs

1. Spain is a competitive producer and exporter of olive oil, wines and other foodstuffs, with the sector showing Revealed Technological Advantages (RTA) as indicated by patent data (Molero & García, 2008; Torrecillas & Martínez, 2022). Other peripheral European countries and emerging economies may share a similar scenario. The 2008 financial crisis, which severely affected Spain through a credit crunch, job losses, and R&D funding cuts, provides a unique opportunity to analyse how economic downturns shape EI. Crises often lead to procyclical reductions in innovation investment (Antonioli & Montresor, 2021; Archibugi et al., 2013; Cincera et al., 2012; Geroski & Walters, 1995), but they may also create opportunities for firms to innovate in response to new challenges (Friz & Günther, 2021; Holl et al., 2024; Suárez, 2014). Furthermore, preparedness, shaped largely by strategic and cultural changes from previous crises, can help firms, industries, and countries mitigate the effects of new crises and be better equipped to design long-run innovative solutions (Holl & Rama, 2016; Klyver & Nielsen, 2024).

This article aims to fill gaps in the literature by analysing the persistence of EI behaviours and their role in fostering resilience during crises. Using panel data from Spanish F&B firms between 2004 and 2016, we adopt a longitudinal approach to study how long-term commitments to influence green technology adoption. In this analysis, we identify three distinct periods: 2004–2007 (boom), 2008–2013 (crisis), and 2014–2016 (recovery). We argue that persistent EI not only stabilizes innovation during economic uncertainty but may also enable eco-innovative firms to capitalize on new opportunities emerging in crises. We also ask whether regulation and other institutional intervention foster EI during harsh economic times.

Section 2 provides the definitions used in our research and outlines key stylized facts regarding innovative activities in this sector.

Section 3 reviews the relevant literature supporting our investigation and presents the hypotheses.

Section 4 offers a description of the contextual setting, while

Section 5 details the research methodology.

Section 6 presents descriptive statistics, followed by results and discussion in

Section 7. Finally,

Section 8 concludes.

2. Definitions and Key Stylized Facts

2.1. Definitions

In the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) of the European Union (EU), an innovation is defined as a new or significantly improved product (good or service) introduced to the market, or the implementation of a new or significantly improved process within an enterprise

2. This is a relevant consideration, as our study relies on data from a CIS-type survey. In academic literature, eco-innovation, specifically, is often referred to by different terms such as “ecological,” “green” or “sustainable” innovation (Galera-Quiles et al., 2021). In reviewing the literature, the aforementioned authors observe that most studies emphasize reducing negative environmental externalities and promoting the effective use of resources, such as energy. Similarly, this article emphasizes these EI. The Eco-Innovation Observatory

3 defines EI as the "introduction of any new or significantly improved product (good or service), process, organizational change, or marketing solution that reduces the use of natural resources (including energy, water, and land) and decreases the release of harmful substances across the whole life-cycle." For a compilation of the various definitions of EI found in the literature, see Díaz-García et al. (2015).

After examining the literature, Hojnik and Ruzzier (2016) characterize a driver of EI as a stimulus, which can function either as a motivation-based factor (such as regulatory pressure, anticipated benefits of adoption, competitive forces and customer demand) or as a facilitating factor (such as the firm’s financial resources and technological capabilities). This article follows this methodological approach.

2.2. Theoretical Background and Key Stylized Facts

A holistic understanding is crucial for studying green strategies in F&B companies. Our analysis is grounded in the evolutionary theory of technological change, which emphasizes the complex, dynamic, and often unpredictable nature of technological advancement, shaped by diverse economic, social, and institutional factors. In this approach, technological evolution is typically cumulative, building on past innovations, and often incremental, involving small, continuous improvements rather than radical shifts (Nelson & Winter, 1982). This theory focuses on path dependency and the role of routines in shaping technological progress. While it emphasizes cumulative and incremental innovation independent of macroeconomic fluctuations, our study extends this perspective by examining how different phases of the business cycle—boom, crisis, and recovery—shape firms' green strategies. Our analysis is grounded in the idea that the macroeconomic environment plays an active role in shaping the evolutionary processes driving the transition to green technology.

Evolutionary theory pays special attention to the specific characteristics of innovation in different sectors of the economy. Pavitt’s (1984) taxonomy categorises industries based on their sources of innovation and the nature of technological change within them. According to Pavit, the F&B industry falls under the category of "supplier-dominated" sectors. This classification highlights that technological innovation in the F&B industry is largely driven by external suppliers. These include manufacturers of processing machinery, packaging equipment, and other industrial technologies. In Pavitt’s view, F&B firms typically have lower research and development (R&D) expenditures compared to high-tech sectors. Much of their innovation comes from adopting and adapting technologies developed by suppliers. In this theoretical context, Malerba (2005) highlights the concept of sectoral innovation systems. Innovation characteristics, he argues, vary across sectors of an economy due to distinct sources of knowledge, varying levels of R&D investments, and different rates of technological advancement. Apparent inconsistencies in the economic literature on innovation frequently arise because the proposed theories aim to identify universal patterns. However, in practice, companies typically adhere to innovation patterns specific to their sectors (Avermaete et al, 2003, Oltra & Saint Jean, 2009). The discussion justifies the interest of sectoral analyses of EI.

Contrary to the common and long-held belief that the F&B industry is low-tech, Galizzi and Venturini (2008) argue that it is actually marked by significant and growing levels of product innovation. They attribute this characteristic to the fact that innovation in this industry is primarily incremental. In their view, using R&D intensity as a measure of innovative output is misleading and fails to accurately reflect the true importance of innovation in the F&B sector. In a previous study (Galizzi & Venturini, 1996), they argue that the F&B industry is one of the most Schumpeterian sectors, where large companies are more conducive to innovation. According to them, the reluctance of SMEs in this industry to engage in innovation is not due to insufficient R&D resources, as these firms do not need to spend large amounts on formal R&D. Instead, the challenge lies in the need for substantial investment in advertising and marketing to profit from innovation. These sunk costs discourage F&B SMEs from innovating, and a "minimum size" is required to successfully access these activities.

In this sector, regulation is a major constraint that must be considered by any company undertaking any type of innovation. As noted by Gonard et al. (1991) in their analysis of the sugar subsector, the regulatory environment is sometimes more influential than technological opportunities in determining technology adoption. However, innovation within the F&B sector has been shaped by an interplay of anticipatory influences from retailing and regulatory frameworks. Some authors note that retailers have encouraged the adoption of new practices even beyond normative requirements, especially regarding innovations that promote the production of safe and high-quality food (Pérez-Mesa & Galdeano-Gómez, 2010; Ménard & Valceschini, 2005). Although in certain developing countries, modern retailing may fail to operate as a source of innovation in F&B production (Nandonde, 2018), in most advanced countries and some emerging economies, modern retailers have had a noticeable impact on improving foodstuffs and enabling the digital traceability of products across the food chain (Belik & Rocha dos Santos, 2002; Ménard & Valceschini, 2005).

On the other hand, the link between food and non-food value chains plays a crucial role in influencing the food and drink SIS (Spendrup & Fernqvist, 2019). The F&B industry now relies on a broad range of sciences and techniques (Acosta et al., 2011; Alfranca et al, 2004). Innovation is increasingly driven not only by a company's internal efforts but also by its interactions within a wider SIS (Bayona-Sáez et al., 2017; Bigliardi & Galati, 2013; García Martínez, 2013; Garcia Sánchez et al, 2016). Rising R&D costs, reflecting trends seen across other sectors, have increasingly driven collaboration (García Martínez, 2013), including green initiatives (Arcese et al., 2015). However, despite open innovation being widespread in the F&B sector (Sarkar and Costa, 2008), some companies remain closed due to concerns about knowledge spillovers, as innovations are easily imitated (Manzini et al., 2017). At the same time, the in-house development of food-related technological fields, such as biotechnology, appears to be on the rise in both large and small F&B firms as a means of improving interactions with suppliers (Alfranca et al., 2004; Rama & von Tunzelmann, 2008).

Another key aspect is the role multinational enterprises (MNEs) play in driving innovation within the global F&B industry. In 2005, the world’s 100 largest F&B MNEs contributed to about a third of the global turnover in the processing industry and produced nearly half of the patented innovations, food-related technological fields included (Rastoin, 2008; Alfranca et al., 2002).

In conclusion, the literature on innovation in the F&B industry reveals a complex interplay between sector-specific characteristics, technological advancements, and external influences, such as regulation. This dynamic environment highlights the need for further research into the long-term interactions of these factors to gain a deeper understanding of the adoption of green innovation in the F&B sector.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Evolution of Environmental Innovation

Most studies on innovation trends align with the view that innovation follows the business cycle, with R&D-related investment decreasing during downturns and increasing during upturns (Antonioli & Montresor, 2021; Archibugi et al., 2013; Cincera et al., 2012; Geroski & Walters, 1995). However, firms are not uniform in this regard. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, high-tech sectors often pursued countercyclical innovation strategies, whereas low-tech industries, such as the F&B sector, displayed procyclical trends (Brzozowski & Cucculelli, 2016; Zouaghi et al., 2018).

Little is known about the evolution of specifically EI, especially at the national level across different phases of the business cycle. However, the effects of crises on the numbers of eco innovators have been explored. Certain studies show that their numbers generally declined after the 2008 financial crisis. Using CIS data, Ghisette (2017) found that, in most EU countries (Spain excluded), the proportion of manufacturing firms adopting EI decreased between 2008 and 2014. The analysis by Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2022), which examines panel data from 320 major global agro-industries between 2002–2017, reveals a 10% increase in the number of eco-innovators. Triguero et al. (2018) observed a decline in EI adoption among F&B firms during the financial crisis in Spain (2008-2013), though their engagement increased again by 2014 as economic recovery began. During crises, firms often face challenges such as credit constraints, reduced demand, and rising energy costs, which can shift their focus away from environmental goals. Furthermore, policies supporting EI may lose social backing during recessions, as public concern for environmental issues tends to wane during harsh economic times (Cicuéndez-Santamaria, 2024). Additionally, EI, particularly renewable energy technologies, often relies on strong political support, which is vulnerable during economic crises (Karakaya et al., 2014). For example, during the energy price surges caused by the war in Ukraine and EU embargoes, European food producers resisted green regulations that further increased costs

4. The discussion suggests that EI trends in the F&B sector, like broader innovation trends, may exhibit procyclical behaviour.

However, crises can also create opportunities for innovation. Suárez (2014), in a longitudinal study of Argentinean firms, observed that during periods of economic instability, firms adapted their innovation activities to changing circumstances. For instance, currency devaluation spurred export-oriented innovation, even among firms without prior experience in this area. The study suggests that the widely accepted idea of a "virtuous circle"—where past innovation drives current innovation—is disrupted in unstable environments. Instead, new opportunities may emerge, highlighting the need for adaptive strategies during crises.

The persistence of innovation is another crucial factor affecting the evolution of EI. Arenas et al. (2020), in their review of the literature, identify three key factors contributing to the persistence of innovative activities: the benefits of knowledge accumulation, the principle that “success breeds success,” and the sunk costs associated with initiatives such as establishing an R&D department. Adding a new perspective to the debate, Raymond et al. (2010) and Triguero et al. (2013) highlight that persistence in innovation varies across sectors, with companies in low-tech industries generally displaying less persistence than those in high-tech sectors. However, past innovation often serves as a driver for current innovation in the F&B sector, where large firms exhibit consistent patterns of technological accumulation. Alfranca et al. (2002) noted that the world’s largest F&B multinationals frequently sustain innovation through gradual capability building. It is the established innovators who drive significant changes in foodstuffs and introduce new packaging methods among these MNE. While the influence of past innovations -- they note -- tends to be lasting, other potential drivers of technological change may only have temporary effects on innovation. Triguero et al. (2013), in analysing Spanish F&B firms during 1990–2008, found that innovative activities, particularly process innovations, are persistent. However, persistence may also lock firms into pollution-intensive technologies, creating barriers to adopting cleaner alternatives. Cecere et al. (2014) argued that entrenched reliance on existing knowledge, infrastructure, and capital perpetuates pollution-intensive practices.

Sector-specific analyses reveal varying patterns of persistence in EI. Le Bas & Poussing (2018) found that while eco-innovators seeking to reduce negative environmental impacts often exhibit persistence, those focused on resource efficiency (e.g., energy and material savings) are less consistent. In the Spanish F&B sector, Triguero et al. (2018) similarly identified past EI as a key driver of current efforts during 2008–2014. The discussion suggests that past eco-innovation efforts could be a driver of current EI.

However, studies on the interaction between persistence and business cycles in EI remain limited, especially in the F&B sector. Most studies on persistence concentrate on periods of economic stability (pre-2008) or times of economic distress (such as the 2008 financial crisis). When studies span both favourable (pre-crisis) and challenging (crisis or post-crisis) economic periods, they often fail to distinguish between these business environments. An exception is Antonioli et al. (2013), who analyse the pre-crisis and the 2008 crisis period, examining the continuity of intense firm-level innovation activities from 2006 to 2009. Their study investigates how manufacturing firms in Emilia-Romagna (Italy) responded to the 2008 crisis in terms of innovation and concludes that ‘” innovation calls for innovation”; this phenomenon occurs even during a crisis. However, a later study found that the persistence of Italian firms that survived the 2008 crisis was only linked to process innovation and radical innovation (Antonioli & Montresor, 2021). García-Sánchez & Rama (2024) identify distinct phases of the business cycle (boom, crisis and recovery), observing that although the 2008 crisis initially discouraged cooperative innovation among Spanish firms, companies eventually compensated by gradually acquiring experience. These studies refer to standard innovation, not to EI. However, the interplay between a firm’s persistence and macroeconomic conditions suggests that firms with a strong history of EI may also be better equipped to withstand downturns, maintaining their efforts despite adverse conditions.

3.2. Other Key Determinants of Eco-Innovation

The literature also points to the following key drivers of EI:

Institutional intervention. Porter and van der Linde (1995) introduced the "win-win" proposition, suggesting that environmental regulations could drive innovation by encouraging industries to recognize and take advantage of opportunities they might otherwise overlook. They argued that this process would yield both environmental gains and a boost in competitiveness. This idea has prompted extensive research into how environmental regulation affects innovation; however, empirical findings have remained inconclusive. Bossle et al. (2016) and Hojnik & Ruzzier (2016) highlight regulation and cost savings as major EI drivers, with policy stringency being particularly influential. However, other scholars (e.g., Bernauer, 2007; Guo et al., 2017) report mixed results. Regulation’s effectiveness may depend on public R&D funding (Guo et al., 2018) or alignment with broader policy goals (Cecere et al., 2014). Regional differences also matter: for instance, regulation appears more effective in promoting EI in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe (Horbach, 2016).

In the F&B sector, previous studies suggest regulation and market-push factors are key to EI adoption. Avellaneda Rivera et al. (2018) and Triguero et al. (2018) show that stringent regulation, driven by health concerns, significantly influences EI in Spanish F&B firms. However, in the Spanish wine sector, Calle et al. (2022) find that EI is primarily driven by firm-level decisions rather than regulation. The analysis of the effects of regulation across the business cycle has been rarely addressed in the literature on EI, as is done in this article.

While subsidies are important, the literature shows mixed results regarding their effectiveness. In Eastern Europe and China, subsidies are crucial for EI (Cai & Li, 2018; Horbach, 2016), but Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) found little effect in Spain. In their analysis of 301 SMEs in the F&B industry of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Cuerva et al. (2014) found that subsidies enhance non-eco-innovations but not EI. These findings suggest that the impact of subsidies can vary significantly across regions, sectors, and types of innovation. Other types of institutional intervention, such as R&D contracts between the government and firms, are rarely addressed in the literature on EI, a gap we aim to tackle in this article. As noted in the Introduction, our primary focus is to understand the role of institutional intervention in influencing the likelihood of firms maintaining their EI activities during challenging economic periods.

Size. In their literature review, Honik and Ruzzier (2016) observe that larger companies are more likely to adopt and extensively implement EI. This trend arises from the inherent advantages of large firms in the realm of innovation, such as greater access to financial resources and structured R&D departments. Additionally, the size and prominence of these companies necessitate efforts to reduce their environmental footprint to meet the expectations of environmental groups and regulatory demands. In their review of the literature, Bossle et al. (2016) also note that larger companies are more likely to adopt and extensively implement EI. This trend is confirmed in Spanish manufacturing (Mazzuchelli & Montresor, 2017) and F&B sectors (Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2022; García-Granero et al., 2020; Triguero et al., 2018). However, some studies challenge the assumption that SMEs are less eco-innovative than large firms (Díaz-García et al., 2015).

Knowledge Base. Both Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) and Triguero et al. (2018) find that R&D intensity—measured as R&D expenditure per employee—promotes EI in Spanish firms. In contrast, Cuerva et al. (2014), in their analysis of F&B companies within a Spanish region, conclude that while R&D supports standard innovation, it does not necessarily drive EI. While R&D is often seen as a key driver of EI in developed countries (Cainelli et al., 2015), in developing countries like Chile, R&D may have little effect due to the firms’ difficulties in accessing new knowledge (Fernández et al., 2021). Additionally, firms with a strong knowledge base in polluting technologies may struggle to transition toward EI (Cecere et al., 2014). These findings highlight that the relationship between R&D and EI is context-dependent, influenced by factors such as industry and region.

Collaboration and External Sources of Information. Certain authors note that collaboration with external partners such as clients and suppliers, can be a powerful driver of EI, particularly in the complex and cost-intensive F&B sector (Bossle et al., 2016; Rabadán et al., 2019; Triguero et al., 2018). However, an over-reliance on external sources or excessive collaboration can hinder innovation, as seen in studies on Spanish firms (Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco, 2018). Balancing cooperation with various partners is essential to avoid dependency and maximize innovation outcomes (Avellaneda Rivera et al., 2018). Retailers also play a unique role in EI adoption (Triguero et al., 2018), probably by anticipating regulatory trends.

Ownership Structure. Certain authors suggest that ownership affects a firm's eco-innovation strategy. For instance, Aibar-Guzmán et al., (2022) find that, within the group of large global agri-food firms, multinational companies are more likely to engage in EI due to their greater access to funding and resources, while family-owned firms tend to be more conservative in adopting green technologies. Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) note that, within the Spanish manufacturing sector, being part of a business group does not guarantee a firm will be a green innovator.

Market-push Factors. Expanding market share is identified as a significant motivator for firms to invest in EI (Bossle et al., 2016). Triguero et al. (2018) found that both market demand and regulatory pressures positively influenced EI adoption in the Spanish F&B industry during 2008-2014. However, the literature shows inconsistent results regarding the influence of market-push factors on EI. For instance, Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) found that market forces did not serve as a primary driver for EI in Spanish manufacturing firms.

To summarize, authors do not agree about the influence of many of these drivers, indicating the need for further research to better understand these dynamics.

Based on the previous discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1:

The crisis opens new opportunities for food and beverage firms adopting eco innovation.

H2:

Past eco-innovation efforts positively influence the likelihood of future eco-innovation in the food and beverage industry, even in critical periods.

These hypotheses are tested for both efficiency and environmental EI.

4. Contextual Setting

According to European Innovation Scoreboard, Spain is categorized as a moderate innovator

5. It is also a medium adopter of environmental regulation, positioned behind Denmark but ahead of Italy (Park et al., 2017). Moreover, Spain produces a substantial volume of environmental regulations, surpassing France (Mora-Sanguinetti & Atienza-Maeso, 2024). As a member country of the EU, Spain is subject to stringent environmental regulations regarding specifically F&B and packaging. Leveraging its abundant natural resources in solar and wind energy, Spain has made significant strides in renewable energy development in the period following the one analysed in this article, notably during the current European energy crisis

6. Efforts have focused on expanding capacity, attracting investments, and establishing regulatory frameworks to ensure sustainable growth. Spain is actively working to position itself as a leading producer of green hydrogen in Europe. By 2024, approximately 52% of Spain's electricity production came from renewable sources, with ongoing projects targeting an increase to 81% by 2030. Unlike other European countries, Spain has not reverted to using coal during the current energy crisis

7. The perceptions of firms regarding the importance of EI and their views on green regulation, as analysed in this article, provide insights into their preparedness to confront future crises.

Austerity policies, high unemployment rates, precarious jobs, and a growing population affected by poverty all influenced food consumption patterns during the Spanish 2008 crisis (Díaz Méndez & García Espejo, 2023). Using data from the National Health Survey and the European Health Survey in Spain, the aforementioned authors found that the Mediterranean diet

8 remained largely unchanged during the 2008 crisis. The notable exceptions were a decrease in the consumption of fruit and fish, and an increase in the consumption of more affordable pulses. In their view, solid cultural traditions and cooking skills helped maintain dietary stability despite the harsh macroeconomic conditions. However, they also noted that the crisis led to a preference for cheaper brands, a reduction in household food waste, and a greater focus on cooking at home. During the 2008 global crisis, Eurobarometer data indicated a shift in environmental concern among both the Spanish population and the wider EU population. As noted by Cicuéndez-Santamaria (2024), this concern generally declined, likely because economic issues took precedence during that challenging period. Eurobarometer data shows that in 2007, just before the onset of the global crisis, 64% of Spaniards considered the environment very important. However, this percentage fell to 56% at the peak of the crisis in 2011 (Cicuéndez-Santamaria, 2024). By 2020, this figure had risen again to 63%, illustrating the impact of economic cycles on environmental perceptions. The discussion highlights the need to investigate the influence of market factors, particularly during critical periods, due to their potential impact on shaping EI.

The 2008 financial crisis also significantly impacted Spain in other ways, leading to a decline in innovation investment and reductions in public R&D spending (Cruz-Castro et al., 2018; Holl & Rama, 2016). Spanish annual green expenditures—including those by the state, firms, and households—dropped significantly following the onset of the 2008 crisis and only began to increase again with the economic recovery starting in 2014 (

Figure 1).

5. Methodology

5.1. Data

The PITEC database used in this study is collected annually by the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) and serves as Spain's contribution to the EU’s CIS

9. This database offers the benefit of providing panel data and is based on a mandatory survey. The panel employed in this study consists of data from F&B companies that remained continuously active throughout the 2004–2016 period for a total of 8,699 observations and 871 F&B firms. As noted, this timeframe is divided into three sub-periods reflecting the trajectory of Spanish GDP (García-Sánchez & Montes-Luna, 2022): 2004–2007 (boom), 2008–2013 (crisis), and 2014–2016 (recovery). In the PITEC database, the concept of innovation is broadly defined, encompassing both innovations that are new to the market and those that are merely new to the firm, even if they already exist in the market. While the latter might be more accurately classified as technology adoption, we will use the term 'innovation' to maintain consistency with our data source.

A limitation of the eco-innovator data provided by PITEC is the subjectivity inherent in firms' self-reported perceptions, a common issue in similar studies. These data reflect firms' stated considerations for green innovation, rather than the actual performance of their eco-innovations. For instance, we found that 40% of firms that reported saving materials and energy as a highly or moderately important goal had not innovated in the last two years

10. To address this and adopt a more objective approach, we limited our sample to firms that had demonstrably innovated. Therefore, our approach is conservative: we define eco-innovators as firms that have innovated within the last two years (whether eco-innovations or non-eco innovations) and additionally declare a high or moderate importance of green goals when innovating. Another difficulty, as highlighted by Horbach (2016), is that CIS surveys do not provide specific data on R&D for eco-innovation, forcing researchers to depend on general R&D and innovation data. This limitation similarly affects the PITEC data analysed in this study.

The correlation matrix indicates no significant multicollinearity problem (available upon request).

5.2. Model and Variables

Our research strategy involves an iterative estimation of ten logit models using panel data, with inferences derived from robust panel standard errors. The initial set of models jointly examines the effects of business cycle phases and EI persistence, while controlling for the influence of drivers and other relevant variables:

In models [

1] and [

3]

includes the full set of EI drivers and control variables listed in Annex 1 (

Table A1) and the categorical variable

crisis; the corresponding parameters are denoted by

. In models [

2] and [

4],

includes the variables identifying the persistence in both EI types in addition to

,

representing the corresponding parameters.

The second set aims to identify differences in the influence of drivers across various phases of the business cycle, while controlling for other variables. To achieve this, we segmented our sample into three periods: boom (2004–2007), crisis (2008–2013), and recovery (2014–2016). We then estimated six models ([

5] to [

10]), with three models dedicated to each EI type:

Our independent variable sets denoted as include the whole set of EI drivers, the control variables set, and the variables capturing persistence in both EI types. The business cycle phases are represented by , with the corresponding parameters denoted as .

5.3. Dependent Variables

The questionnaire measures the degree of importance a firm assign to saving materials and energy, as well as avoiding environmental harm during the innovation process, using a 4-point Likert scale. We classify as eco-innovators those firms that indicated green considerations were either very important or moderately important in their innovation processes (corresponding to responses 4 and 3 on the Likert scale).

EcoEffic_innov is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm’s innovation goal is primarily or moderately focused on saving materials or energy per unit of output in the two previous years.

EcoEnviron_innov is a dummy variable set to 1 if the firm's innovation goal is primarily or moderately focused on reducing environmental impact in the two previous years.

5.4. Independent Variables

Only the variables of primary interest are presented below. Table Annex 1 provides a description of the complete set of variables and their frequencies. Note that an 'i' preceding the variable name denotes intensity, indicating, for example, that the firm undertakes an R&D effort above the Spanish F&B industry average.

The variables of primary interest are those that delineate the effects of the 2008–2013 crisis and the firm's past eco-innovation on current eco-innovation.

Crisis: 2004-2007 is our base category; crisis 2008-2013; recovery 2014→

PersistEcoEffic: Dummy variable that equals 1 If the firm performed efficiency eco innovation in and .

PersistEcoEnvIron: Dummy variable that equals 1 If the firm performed environmental eco innovation in and .

Building on the methodology of Hojnik and Ruzzier (2016), we classify our set of EI drivers into motivation-based and facilitating factors. Motivation-based drivers of EI include regulation, which is also a variable of interest, competitive forces, the anticipation of innovation benefits, and market factors that either encourage or hinder innovation.

Regulation. The questionnaire asks firms whether they consider environmental, health, and safety regulations when innovating, with responses on a 4-point Likert scale (high, moderate, reduced, not relevant). The “reduced” response serves as the base category, as we expect a positive effect associated with a stronger perception, which turns negative when associated with “non-relevant”.

Facilitating factors include financial resources (such as private and public funds, contracts, and subsidies), technological capabilities (including innovative efforts, cooperative behaviour, and spillovers), and the innovation class (product innovator, process innovator, or both).

As control variables, size is controlled using a categorical variable. Instead of employing a VIF size index, we classify firms into size categories: micro-firms (<10 employees), medium firms (50–249 employees), medium-large firms (250–999 employees), and large firms (≥1000 employees), with small firms (11–49 employees) serving as the base category. This approach aims to address concerns of multicollinearity and aligns with the concept of a threshold for engaging in innovation in this industry (Galizzi & Venturini, 1996). The results remain congruent and robust across these classes. Ownership identifies domestic and foreign capital (multinational), and group-belonging is accounted for (independent). Industry-effects are controlled by using dummies variables to compare firm's data with the Spanish F&B industry average.

6. Descriptive Statistics

The following analysis presents descriptive statistics for the entire period from 2004 to 2016.

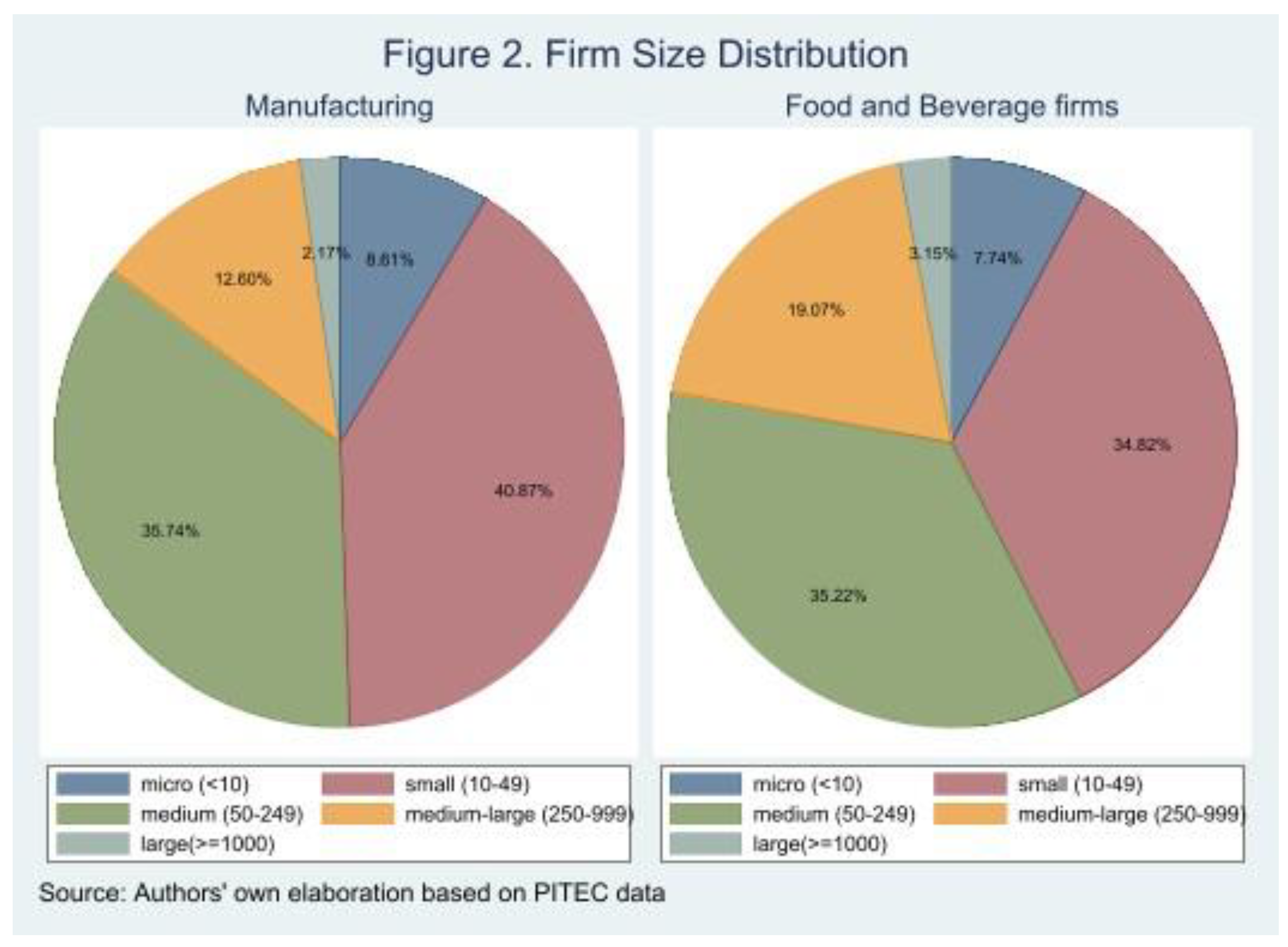

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of our sample by company size, highlighting the predominance of SMEs. This distribution aligns with the overall structure of the Spanish manufacturing sector.

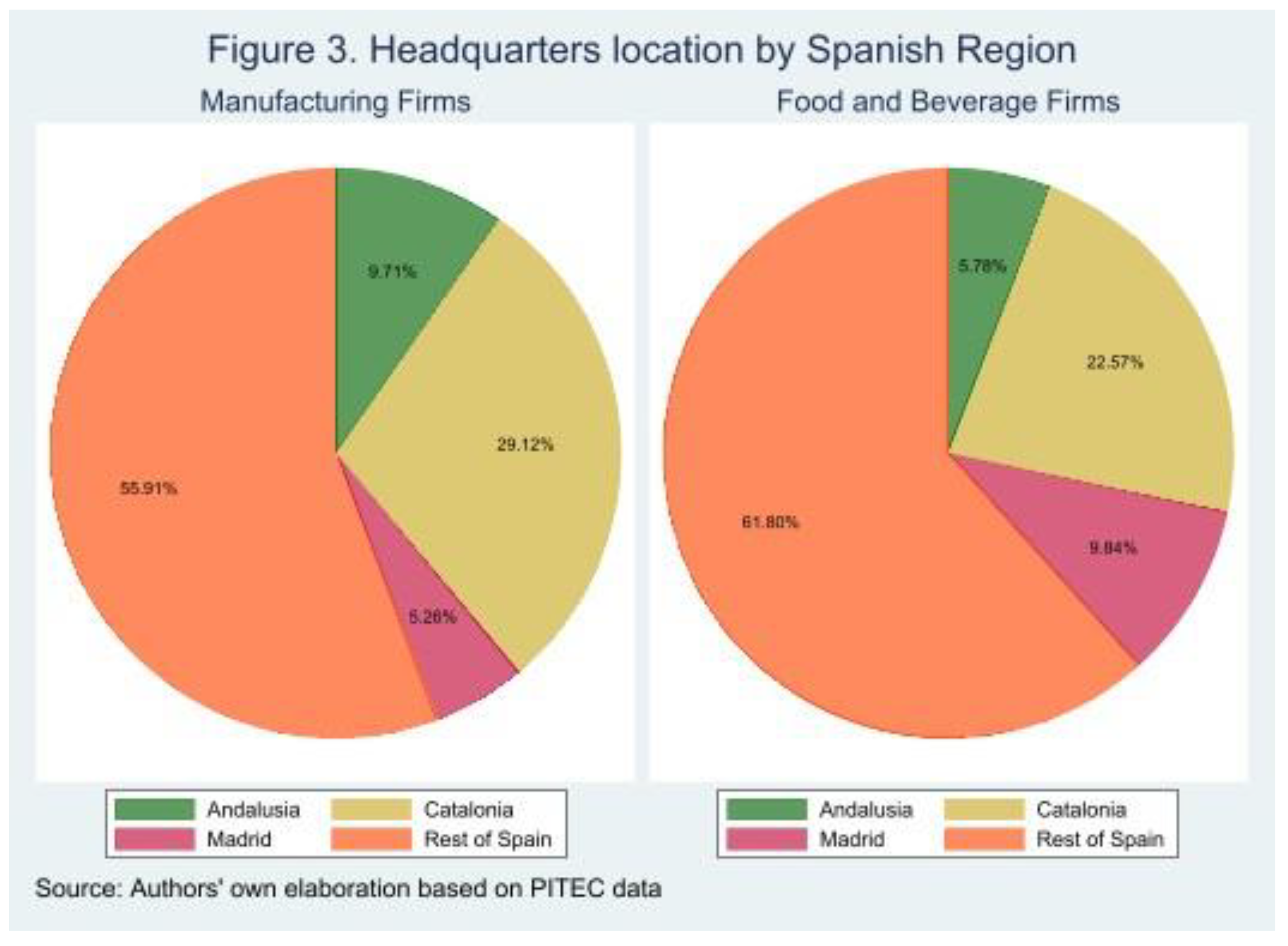

Figure 3 shows the geographic distribution of the sample based on the location of company headquarters. It reveals a more geographically dispersed presence of F&B companies compared to the broader manufacturing sector. However, note that Catalonia still concentrates a significant proportion of both F&B firms and manufacturing companies across all sectors.

In the sample, 51% of firms engaged in internal R&D over the past two years. However, the proportion of innovators is significantly higher at 89%, indicating that a substantial portion of innovative activities originates outside formal R&D laboratories.

When innovating, 54% of the sample assign high or medium importance to complying with environmental regulations. However, around 30% of firms report that they do not consider eco-regulations when engaging in innovation. There is a positive correlation between the importance a firm assign to this goal and its size (Chi 2=158.1058; Pr = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.0890).

Firms were also surveyed on the importance of eco-motives for innovation. Approximately 60% of the sampled firms consider reducing material and energy usage per unit of production to be highly or moderately important. At the opposite end, only 14% of F&B companies consider it unimportant. When examined by firm size, medium-large and large companies are most inclined to regard this objective as highly or moderately important in their innovation efforts -- 34% and 45%, respectively. A Pearson Chi2 test suggests a positive association between firm size and the perceived importance of saving energy and materials in innovative efforts (Pearson Chi2 = 247.9819; Pr = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.0973). However, firms of all sizes rate this objective as highly or moderately important, with 59% of micro firms notably sharing this view. This suggests that successfully engaging in these green activities does not require a specific minimum size. The database also contains information about the perceived importance of eco-motives in reducing environmental harm through innovation. Approximately 52% of the sampled firms consider this goal to be highly or moderately important. A positive association appears between firm size and the importance assigned to avoiding environmental harm in innovation practices. However, the Cramer’s V test only marginally supports this association (Pearson Chi2 =211.9720; Pr = 0.000; Cramer’s V = 0.1031).

The location of a firm and the scope of its market appear to influence its green priorities. Firms based in Andalucía, for instance, place particular emphasis on conserving materials and energy in their innovation efforts, with 46% considering this a highly important objective—significantly above the national average of 36%. However, regarding the goal of avoiding environmental harm, location in specific regions does not appear to lead to notable differences in firm perceptions; instead, the firm's market scope seems to play a more significant role. Firms primarily operating in local or regional markets are more likely than average to prioritize material and energy savings in their innovation strategies; 55% of these companies rate this goal as highly important, compared to 35% across all firms. Conversely, these local/regional firms are less likely than average to prioritize environmental protection in their innovations (17% vs. 24%) or to emphasize regulatory compliance (24% vs. 28%). This suggests that firms operating in restricted geographic markets, often constrained by limited resources and the need to carefully manage input costs, prioritize energy and material savings over other green considerations.

Data by phase of the business cycle show that the percentage of efficiency eco-innovators increased from 32% during the boom period (2004-2007) to 35% during the 2008 crisis, maintaining this level throughout the recovery. The two variables (percentage of efficiency eco-innovators and phase of the business cycle) are statistically associated (Pearson chi2(2) = 7.6135, Pr = 0.022, Cramér's V = 0.0296). Similarly, the percentage of environmental eco-innovators rose from 45% during the boom to 50% during the crisis and recovery. The variables are also associated in this case (Pearson χ²(2) = 14.5062, p = 0.001, Cramér's V = 0.0468). Our results do not align with those of Ghisetti (2017) for other countries and sectors. However, they are consistent with Jové-Llopis & Segarra Blasco (2018), who observed a similar upward trend in ecological concern among Spanish manufacturing firms between 2008 and 2014. In our sample, the percentages of both types of eco-innovators increased during the crisis and recovery periods, suggesting that firms adopted a countercyclical strategy. Furthermore, the sampled firms seem to leverage lessons learned during the crisis rather than simply returning to pre-crisis paths. This probably indicates a cultural shift towards sustainability in this industry.

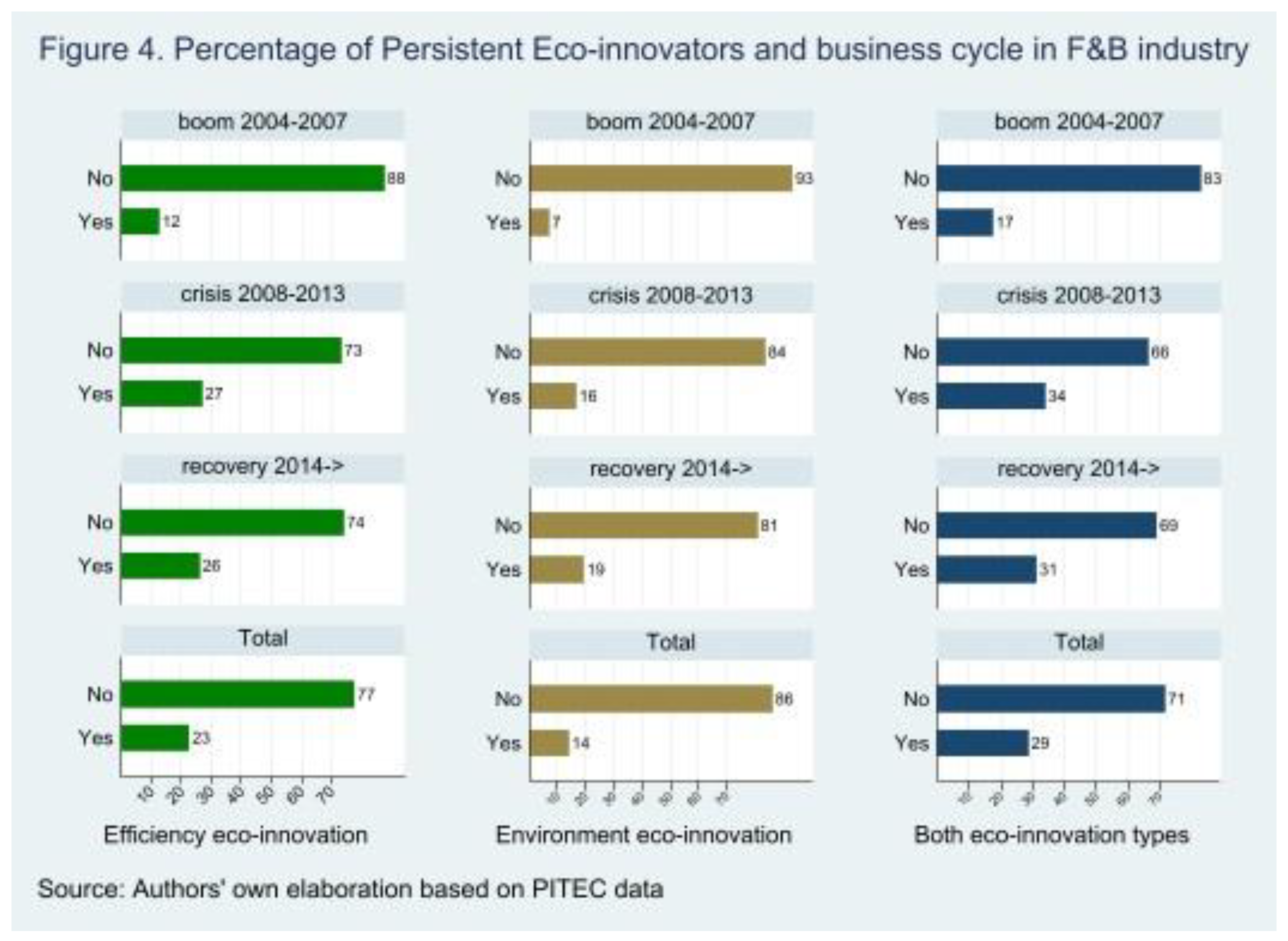

Persistent eco-innovators—those who engaged in eco-innovation continuously in both t-1 and t-2 —represented a smaller share compared to the overall eco-innovator group, which includes both sporadic and persistent eco-innovators. During the boom, persistent efficiency eco-innovators made up only 12% of the sample, while persistent environmental eco-innovators comprised just 7% (

Figure 4). While the overall percentage of eco-innovators increased slowly during the crisis and recovery, the percentage of persistent eco-innovators grew much more rapidly. Notably, the percentage of both persistent efficiency and persistent environmental eco-innovators more than doubled during these phases, suggesting a potential snowball effect. This was not the case for the Italian firms analysed by Antonioli and Montresor (2021) during the period 2005–2013, as the persistence of those that survived the 2008 crisis was limited. Another possible explanation for our findings is that our entire sample consists of surviving firms, as those that closed due to the crisis are not included—a limitation shared with previous studies (Antonioli & Montresor, 2021). Therefore, persistent eco-innovators may have been more likely to survive, which could explain the substantial increase in their percentages during the crisis. However, the data do not allow us to test this hypothesis.

7. Results and Discussion

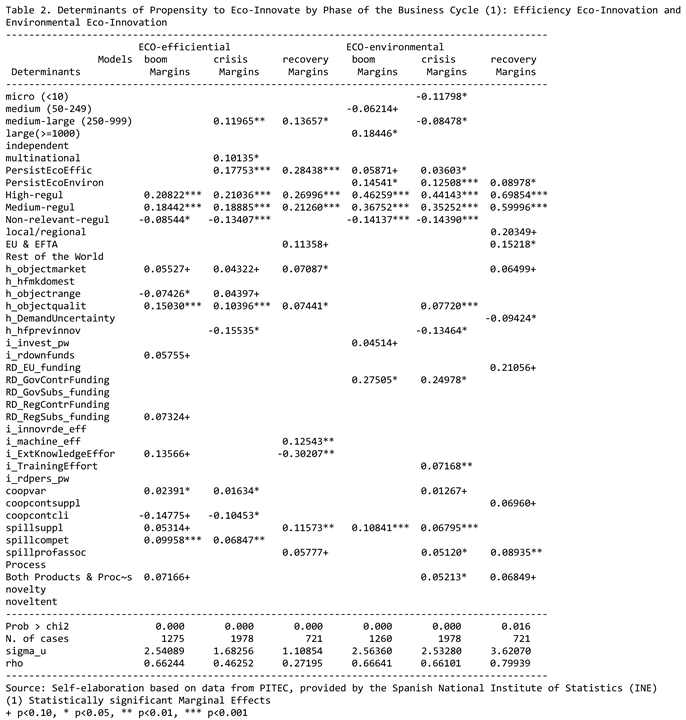

7.1. Persistence and Crisis

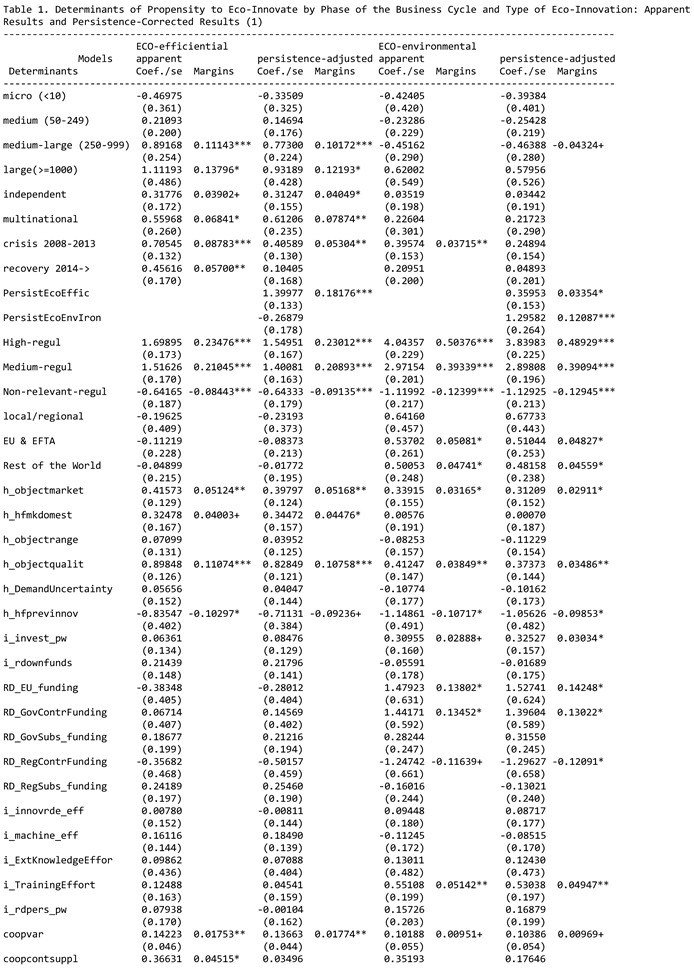

Table 1 presents the drivers of eco-innovation over the full 2004–2016 period, reporting only the marginal effects (dy/dx) of statistically significant variables. Models 1 and 3 exclude persistence variables and examine the probability that a firm engages in efficiency EI and environmental EI, respectively. Models 2 and 4 introduce persistence variables—

PersistEcoEffic and

PersistEcoEnvIron—to account for firms' historical innovation tendencies.

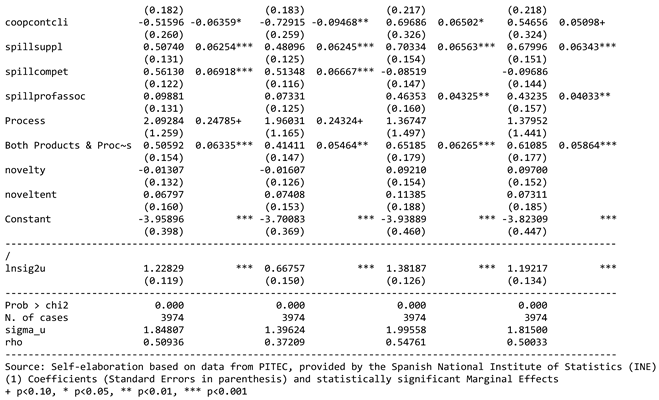

Table 2 breaks down the marginal effects of EI drivers across three distinct periods: 2004–2007 (boom), 2008–2013 (crisis), and 2014–2016 (recovery). Both tables distinguish between efficiency EI (reducing materials and energy use per unit produced) and environmental EI (avoiding harm to the environment).

In

Table 1, the variable

crisis 2008–2013 has a positive and statistically significant coefficient in Models 1 and 3. This suggests that the crisis period apparently increased the likelihood of firms engaging in both types of EI compared to the pre-crisis period. However, these results do not clarify whether firms adopted EI as a strategic response to economic hardship or whether other factors contributed to this increase. We explore this issue further below.

When the

PersistEcoEffic variable is included in Model 2 (

Table 1), the

crisis coefficient remains positive and significant, but its marginal effect decreases. This indicates that persistent efficiency EI partially accounts for the effect initially attributed to the crisis. Specifically, during the crisis, the likelihood of engaging in efficiency EI increases by 9% compared to the pre-crisis period in Model 1. With

PersistEcoEffic included, this likelihood rises by only 5%. This suggests that broader trends in persistent innovation, rather than crisis-specific strategies alone, influenced firms' efficiency EI during this period. Persistence thus moderates the impact of the crisis, reducing the emphasis on crisis-driven strategies. The situation differs for environmental EI. During the crisis, the likelihood of environmental EI apparently increased by 4% compared to the base period (Model 3). However, when the

PersistEcoEnvIron variable is included in Model 4, the coefficient for the 2008–2013 period becomes statistically insignificant. This indicates that persistence is a critical driver of firms' environmental innovation efforts, while the crisis itself is not-significant.

In summary, the crisis primarily stimulated the adoption of material- and energy-saving technologies, likely as cost-control measures during economic hardship. However, the crisis had a neutral effect on environmental innovations, which depend more on consumer demand than efficiency-focused EI. Notably, despite the economic downturn, firms maintained their commitment to environmental EI. This neutrality may reflect opposing consumer trends during the crisis, which effectively cancelled each other out. Official data show that food consumption in Spain decreased by 1.6% in volume and 2.8% in value in 2010 (Carbonell, 2012). Consistent with Díaz Méndez and García Espejo (2023), price sensitivity increased, with more consumers purchasing cheaper food items and brands. Between 2004 and 2010, the percentage of consumers citing price as a prime consideration rose from 40% to 58%, while those choosing the cheapest brands grew from 16% to 22%

11. These trends likely reduced demand for green products, which are often more expensive. Paradoxically, consumer focus on product quality increased during the same period, rising from 57% to 70%. Retailers described Spanish F&B consumers as both price-sensitive and highly informed, reflecting growing awareness of food quality despite economic hardship. Stable demand for green products in premium domestic markets or affluent international markets may also help explain this trend of environmental EI. We return to this question below.

Hypothesis 1, which posits that the crisis creates new opportunities for F&B firms to adopt EI, is only partially supported. While the crisis drove the adoption of material- and energy-saving technologies, it did not significantly encourage environmental EI. Our findings align with Suárez (2014), suggesting that crises can create new opportunities for eco-innovation. However, in this case, the effect is most pronounced for efficiency-focused EI.

How do persistent green innovators perform during a crisis?

Table 2 demonstrates that the positive effect of

PersistEcoEffic remains consistent during challenging periods -- crisis and recovery. As stated, the 2008 financial crisis in Spain posed significant challenges for firms, including reduced credit availability and heightened cost pressures. Despite these barriers, firms with a history of EI were 18% more likely to implement efficiency-driven innovations during the crisis and 28% more likely during the recovery —a period of significant difficulty in Spain — (

Table 2). Similarly,

PersistEcoEnviron, the variable indicating persistence in environmental EI, also has a consistent effect across the business cycle (

Table 2). Firms persistent in environmental EI are 9% to 13% more likely to engage in this type of innovation than non-persistent firms throughout the business cycle. In summary, firms in the Spanish F&B industry with a history of EI are more likely to maintain or increase their EI activities during economic downturns compared to firms without such a history. These results support Hypothesis 2 (

Past eco-innovation efforts positively influence the likelihood of future eco-innovation in the food and beverage industry, even in critical periods). This suggests that persistent eco-innovators were better positioned to adapt to and overcome economic turbulence, likely due to accumulated expertise and established EI practices. Our findings align with Alfranca et al. (2002) regarding patterns of technological change in the F&B industry, highlighting the enduring influence of past innovations compared to other drivers of innovation.

7.2. Motivation Based Drivers of Eco-Innovation

Let’s now begin analysing motivation-based drivers, following the methodology of Hojnik and Ruzzier (2016)

Regulation has the stronger effect. The coefficient of the

Non-relevant-regul category is consistently negative and statistically significant during the 2004-2016 period (

Table 1). Firms that consider regulation irrelevant to their innovation efforts are consistently less likely than their counterparts to engage in any form of EI. Conversely

, High-regul has a positive and statistically significant coefficient in models 2 and 4 (

Table 1). This indicates that, over the entire period, firms that reported placing high importance on regulation when engaging in innovation were more likely to perform EI. Specifically, firms that declared regulation as highly important were 23% and 49% more likely to engage in efficiency EI and environmental EI, respectively. A similar pattern is observed with the

Medium-regul variable, which represents firms attributing moderate importance to regulation in their innovation activities. These findings align with Ben Amara & Chen's (2022) analysis of Tunisian agro-food firms, as well as Bossle et al. (2016). Notably, they are consistent with Avellaneda Rivera et al. (2018) and Triguero et al. (2018), who emphasize the significant role of regulation in driving eco-innovation in Spanish F&B firms.

The comparison of coefficient sizes for the

High-regul and

Medium-regul variables suggests that the relationship between regulation and a firm's likelihood of pursuing EI is stronger for environmental EI than for efficiency-oriented EI (

Table 1, Models 2 and 4). Analysis by business cycle phase further supports this observation (

Table 2). Firms that highly consider regulation when innovating have a 21% to 27% higher likelihood of engaging in efficiency EI throughout the business cycle, while their probability of engaging in environmental EI is significantly higher-ranging from 44% to 70% compared to their counterparts. A similar trend is evident for firms that moderately value regulation. This disparity likely reflects firms' incentives to control costs by adopting technologies that save materials and energy across different business cycle phases, primarily driven by firm-level decisions, although also influenced by regulatory 'push. Our findings align with Caravella and Crespi (2020), who examined Italian manufacturing firms and found that cost-saving motivations are stronger drivers of EI than green state interventions. Notably, neither Spain nor Italy is self-sufficient in energy production.

In contrast, environmental EI appears to be more strongly driven by green regulation. This type of innovation is often riskier, making firms less likely to pursue it independently. However, green regulations may have encouraged firms to capitalize on opportunities they might otherwise overlook, such as exporting green products, as suggested by Porter and Linde (1995). Our findings support Bossle et al. (2016) and Karakaya et al. (2014) in observing that the current trend toward EI extends beyond mere compliance with green regulation. However, our results indicate that this observation is especially applicable to efficiency-oriented EI, particularly in energy-scarce countries like Spain.

The subjective importance firms assigned to regulation (both High-regul and Medium-regul) decreased slightly during the crisis but increased significantly during the recovery that followed. This pattern may be explained by a general decline in environmental concerns in Spain during the crisis, as more immediate issues took precedence, and a resurgence of these concerns during the recovery (Cicuéndez-Santamaría, 2024). Another explanation is that governments might implement less ambitious green policies during times of crisis, as suggested by the study of Mora-Sanguinetti & Atienza-Maeso (2024) for energy regulation in Spain. However, our data do not allow us to test this hypothesis directly, since, as stated, PITEC provides information based on the subjective perceptions of firms rather than objective data on regulation

Market-push factors are also considered motivation-based drivers, encompassing a firm's market orientation, including the market's scope, and the certainty or uncertainty of demand. In our sample, exporters (

EU & EFTA and

Rest of the World) are approximately 5% more likely than non-exporters to implement environmental EI, a strategy more closely aligned with market orientation than efficiency EI, which is primarily cost-focused (

Table 1). Exporters are often better positioned to adopt EI due to higher customer expectations, compliance with international standards and competitive differentiation. Our findings align with those of Arranz et al. (2019) for Spanish firms and with the literature review by Galera-Quiles et al. (2021). Moreover, Spanish F&B companies employed various strategies to navigate the crisis. One significant approach was increasing exports, which grew by 125% from 2009, at the onset of the crisis, to the recovery period before the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the competitiveness of these firms.

Table 2 shows that the greatest impact of market scope occurs among firms exporting to other European countries

12 during the recovery. These firms are 15% more likely to adopt environmental EI compared to their non-exporting counterparts. Regulatory requirements for food safety and environmental sustainability in many other countries may be less stringent compared to European markets. This could reduce the external push for exporters to adopt environmental EI when targeting these markets. Sample exporters responded at a time when European consumers were likely more receptive to green products, as many of these countries had recovered from the economic crisis earlier than Spain. Additionally, the increase in green innovation expenditures in Spain since 2014 may have also contributed to this trend (

Figure 1) by supporting greater investment in EI.

Expected Benefits. The following variables illustrate the market strategies firms aim to implement through innovation. The variable

h_objectrange, which reflects a firm’s goal of diversifying production, has no impact on EI (

Table 1). In contrast, the

h_objectmarket variable, which indicates that increasing market share is a highly important objective for the firm when innovating, shows a positive and statistically significant relationship with both efficiency EI and environmental EI. However, its marginal effects are weaker compared to those of aiming for improved quality (

h_objectqualit). These observations are confirmed by the data segmented by phase of the business cycle (

Table 2). As shown by the marginal effects, during the crisis, firms that prioritized substantial quality improvement when innovating were more likely to engage in efficiency and environmental EI compared to their counterparts.

Certain

market features can either encourage or discourage prospective innovators. In our sample, a market dominated by incumbents, which could hinder innovation in the focal firm (

h_hfmkdomest), has little to no impact on its EI performance (

Table 1). In contrast, above-average difficulties in innovation, due to existing innovations (

h_hfprevinnov) or uncertain demand (

h_DemandUncertainty), are likely to reduce the probability of a firm engaging in EI during periods of crisis and recovery, but not during economic booms (

Table 2). Our findings on the effects of uncertain demand during the crisis align with Arranz et al. (2019), who specifically examine this period. Uncertainty could hinder the sales of new products, such as green foodstuffs or items in recycled packaging, within this conservative industry —especially when consumers become more risk-averse during downturns. Our detailed analysis of market dynamics helps clarify why some studies identify a market influence on EI adoption (Bossle et al., 2016; Triguero et al., 2018), while others do not (Jové-Llopis & Segarra Blasco, 2018). Our findings indicate that specific aspects of firms’ market strategies—such as expansion, quality and geographic scope —stimulate EI adoption, whereas others, like diversification, do not

13. In summary, regulation emerges as the most significant motivation-based driver of EI.

Other forms of institutional intervention, such as subsidies, can be seen as both motivation-based factors—acting as accelerators or dampeners of EI during a crisis—and as facilitating factors from the perspective of the receiving company. Firms that received EU R&D funding (

RD_EU_funding) were no more likely than those without it to engage in efficiency-oriented EI. However, they were 14% more likely to adopt environmental EI over the full period, with this probability increasing to 21% during the recovery (

Table 1 and

Table 2). Once again, firms’ cost-reduction motivations, rather than institutional intervention, may be the driving factor behind efficiency EI. Subsidies from central (

RDGovSubs_funding) or regional governments (

RD_RegSubs_funding) had no significant effect on EI (

Table 1), which is consistent with the findings of Cuerva et al. (2014) and Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) for Spanish firms. R&D funding from contracts with regional governments (

RD_RegSubs_funding) had no effect on EI during 2004-2016. However, funding from central government contracts (

RD_GovContrFunding) increased the likelihood of firms performing EI by 13% during the full period (

Table 1) and by 25% specifically during the crisis (

Table 2). Contracts may be highly target-oriented, driving firms to perform and implement EI, while subsidies often support broader objectives at lower Technology Readiness Levels (TRL), aligning with firms' long-term innovation strategies. In our sample, contracts, which have been rarely investigated in previous studies, significantly impacts environmental EI, especially in times of crisis. However, they had no effect on efficiency-oriented EI. A possible reason is that these contracts likely pertain to F&B services for institutions such as schools, hospitals, and the military, ensuring the quality of the food and packaging themselves. In contrast, in Spain, the criterion for reducing energy usage in government F&B purchases appears to focus on the proximity between producers and end-users, such as schools, rather than on the technology employed in industrial plants (Ramos- Truchero, 2023). The marginal effects suggest that the interventions most likely to support firms' resilience from an EI perspective during the crisis and the recovery were, in order of effectiveness, R&D funding from government contracts and EU R&D funding (

Table 2). Other interventions showed no significant impact during these periods.

7.3. Facilitation-Based Drivers of Eco-Innovation

We now turn to the potential effects of

facilitating factors, such as financing for R&D and a firm's knowledge resources. Note that an 'i' preceding the variable name denotes intensity, indicating, for example, that the firm undertakes an R&D effort above the Spanish F&B industry average. The coefficient for

i_invest_pw, which measures whether a firm’s gross investment in tangible assets per 1,000 employees exceeds the industry average, is positive but only marginally significant at the 90% level. This variable has no impact on efficiency EI and only a weak effect on environmental EI, and only during the boom period (

Table 2). This is in line with Aibar-Guzmán et al (2022). Having a greater-than-average share of own funds allocated to R&D

(i_rdownfunds,

Table 1) does not ensure that a firm systematically engages in EI, though it exerts a weak influence on both types of EI during the boom (marginally significant at the 90% level,

Table 2). Firms with high R&D personnel intensity do not exhibit a clear tendency to adopt EI, consistent with the findings of Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2022), Cuerva et al. (2014) and Fernández et al. (2021). Our finding is supported by the results for

i_innovrdeff, which reflects above-average effort in both internal and external R&D. Firms that had previously engaged in both product and process innovation (

Product&Process) exhibited a 5% and 6% higher probability of adopting efficiency-related and environmental EI, respectively, over the full period (

Table 1), compared to those that had engaged in either product or process innovation alone. Innovative firms, even if not focused on ecological fields, are more likely to engage in EI. While prior research (Galizzi & Venturini, 1996) indicates that many innovations in this industry occur at the operational level of industrial plants, outside formal R&D departments, our findings suggest that this is particularly true for EI.

i_machine_efft, which reflects above-average effort in acquiring machinery, equipment and software, increased the likelihood of efficiency-oriented EI by 13% during the recovery (

Table 2). Spanish F&B companies responded to stagnant demand and heightened competition following the 2008 crisis by adopting new technologies and machinery that emphasized energy and material savings (Cruz, 2012). These included innovations like residue recycling and improved hygiene systems. During the recovery, firms likely increased their investment in machinery due to improved access to credit, enhanced green expenditures (

Figure 1), and a resurgence in consumer demand—particularly for quality products from other European countries—following the crisis. Similarly,

i_TrainingEffort contributed during the crisis by increasing the likelihood of environmental EI by 7%.

The ability of a firm to profit from externalities is also part of its knowledge resources. The coefficient for

i_ExtKnowledgeEffor during the crisis shows a statistically significant negative relationship with EI. This suggests that as firms adopt EI, they tend to rely less on external knowledge sources, such as patent acquisitions, during harsh economic times probably due to cost constraints, likely prioritizing internal resources instead (

Table 2). The variable

coopvar, which reflects the variety of a firm’s cooperation partners, shows a positive and statistically significant coefficient (

Table 1), consistent with findings by Avellaneda Rivera et al. (2018). However, as indicated by the marginal effects, its impact on EI is minimal. Continuous cooperation with clients or suppliers is not particularly conducive to environmental EI. At first glance, this result appears counterintuitive, as theoretical frameworks emphasize the importance of technology suppliers for this industry (Pavitt, 1984). One possible explanation is that F&B firms, including SMEs, are increasingly focused on keeping up with advancements in food-related technologies (Alfranca et al., 2004; Lavarello et al., 2011; Rama & von Tunzelmann, 2008). For instance, SMEs in Spain’s agri-food industry are advancing in digitalization (Calafat-Marzal et al., 2023), suggesting that the industry is not entirely reliant on external upstream technology suppliers. A study of European firms found a link between digitalization and involvement in eco-innovation (Montresor & Vezzani, 2023), underscoring the significance of auxiliary technological fields in adopting green technology. Biotechnology, in turn, can promote greener practices, such as waste reduction. We briefly explore now the relationship between in-house biotechnology practices and EI in our sample. We find no significant relationship between the goal of reducing material or energy usage and a firm’s direct engagement in biotechnology (Pearson chi²(3) = 1.8112, p = 0.612; Cramér's V = 0.0144). However, firms that prioritize reducing environmental harm are more likely to engage in biotechnology (34%) compared to those that do not (23%) (Pearson chi²(3) = 70.7662; p = 0.000; Cramér's V = 0.1031). This suggests that firms may utilize biotechnology science and techniques specifically to mitigate environmental damage, with at least some of these techniques being integrated within the operations of the F&B firm itself.

Our finding that the two forms of cooperation analysed do not significantly drive EI contrast with the results presented in the literature review on EI conducted by Bossle et al. (2016). This discrepancy may be due to the varying capacity of the F&B industries in different countries to develop in-house upstream technology, reducing the importance of cooperation. As noted in the Introduction, the Spanish F&B industry has a RTA, which may help explain this capacity. In contrast, our results align with those of Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) for the entire Spanish manufacturing sector. However, previous studies suggest that in the F&B industry, cooperation is particularly valuable for formal agreements fostering radical EI (Triguero et al., 2018) or for tackling specific challenges, such as implementing green packaging systems (García-Granero et al., 2020).

As shown in Annex

Table 1, 62% of the sampled firms report spillovers from suppliers as a source of knowledge for innovation. Employing these spillovers increases the probability of generating efficiency or environmental EI by 6% (

Table 1). These spillovers are particularly significant for efficiency EI during recovery periods, where the probability increases by 12% and aligns with the timing of equipment and software acquisition, suggesting a complementarity between the two (

Table 2). Spillovers from competitors increase the likelihood of efficiency EI by 7% but have no effect on environmental EI. Competitors may be more willing to share knowledge on saving energy or materials than on marketable products. Another possible interpretation is that F&B firms may have a stronger capacity to profit from spillovers through interactions with competitors in terms of efficiency, rather than product development, due to lower restrictions related to industrial property rights, industrial secrecy, etc. On the other hand, factors spillovers from professional associations positively influence the probability of producing environmental EI by 9%, proving particularly useful for eco-innovators during periods of crisis (

Table 2). As noted by the evolutionary theory, technological change is influenced by social factors. Qi et al. (2021) observe that firms tend to adopt green innovations through imitation when their peers do, especially during uncertain times. Thus, our results may be explained by firms identifying their peers within professional associations. Additionally, as is the case with other Spanish sectors (Álvaro-Moya et al., 2022), professional associations in the F&B sector may act as catalysts or knowledge hubs, identifying opportunities and disseminating inherent knowledge.

In summary, the sampled firms benefit from knowledge spillovers rather than direct cooperation. A possible explanation is that F&B firms increasingly develop food-related technologies in-house, or at least partially, reducing the need for direct collaboration with suppliers to produce or adapt these technologies for their industrial plants. In contrast, ideas and advice—constituting knowledge spillovers —remain valuable for F&B companies in fostering EI. Our results align with those of previous studies regarding the importance of the technological value-chain for this industry, as outlined in subsection 2.2. However, we also highlight certain nuances related to the relative significance of cooperation, spillovers and patent or licences acquisitions, as well as the impact of macroeconomic conditions.

7.4. Control Variables

Size. During prosperous times, micro-firms behave similarly to small firms, our base category. However, during crises, micro-firms are 12% less likely to engage in environmental EI, probably due to increased credit constraints (

Table 2). In contrast, their motivation to save materials and energy remains comparable to that of small firms, aligning with the descriptive statistics. Once again, the results underscore the importance of self-motivation in achieving material and energy savings, even among micro-firms.

Medium-sized firms generally exhibit eco-behaviour similar to small firms (

Table 1). However, a phase-by-phase analysis of the business cycle shows that medium-sized firms outperform small firms in saving materials and energy during crises and recoveries (

Table 2). Conversely, their environmental EI performance declines relative to small firms during crises. As firm size increases, the likelihood of EI also rises. Nevertheless, large firms, despite their significant resources, demonstrate superior environmental EI performance primarily during economic booms, while their performance falters during challenging economic periods. Our results align with those of Díaz-García et al. (2015), but only during periods of economic growth, highlighting how EI drivers shift throughout the business cycle. Actually, our results reveal nuanced patterns regarding size (see subsection 2.2.): across the entire panel, medium-large and large companies favour efficiency-oriented EI, with no notable differences in reducing environmental impact. However, when segmented by business cycle phases, medium-large companies maintain their focus on efficiency-oriented EI, while smaller companies exhibit a procyclical tendency toward reducing environmental impact, particularly during the crisis period.

Ownership. Over the full period, independent firms not affiliated with any business group — whether national or multinational — perform similarly to domestic business groups (DBG) (our base category) in terms of efficiency EI. They also exhibit similar performance in environmental EI. Our results are in line with those of Jové-Llopis & Segarra-Blasco (2018) and Marzucchi & Montresor (2017). Throughout the period, multinationals were 8% more likely than DGB to engage in efficiency-related EI but showed no significant difference in environmental EI (

Table 1). Phase-specific analysis of the business cycle suggests that this advantage was evident primarily during the crisis, when multinationals exhibited a countercyclical effect (

Table 2). This is likely due to their better access to international financing, while domestic firms were disproportionately affected by the Spanish credit crunch—rather than being driven by the intrinsic innovativeness of multinationals. One possible explanation for the discrepancy with the theoretical expectations regarding the innovativeness of F&B multinationals (subsection 2.2) is that these companies often introduce novelty to host countries in areas such as standard innovation, design, and packaging, but not necessarily in EI. A contributing factor may be that many multinationals operating in the Spanish F&B industry originate from energy-rich countries or nations with less stringent environmental regulations than those of the EU, such as Spain. As a result, they may lack a solid foundation in EI technology. Space constraints prevent us from exploring this interpretation further here.

7.5. Summary and Final Considerations

The analysis reveals that the drivers of environmental innovation (EI) shift throughout the business cycle. For example, firms' exporting activities become significant drivers of EI when rising demand in other European countries signals an early recovery. Similarly, spillovers from suppliers emerge as important drivers during the recovery phase, aligning with firms' investments in machinery and software likely aimed at saving materials and energy. This finding may help reconcile contradictory results in the literature, which are based on analyses conducted at different stages of the business cycle (see subsection 2.2.).

Moreover, the strategies employed by different types of eco-innovators during harsh economic times -- crisis and recovery -- vary significantly (

Table 2). Efficiency-focused eco-innovators often invest in new machinery and complement this by acquiring knowledge from suppliers, likely to adapt the new equipment to their specific needs. In contrast, environmentally focused eco-innovators tend to pursue a multifaceted strategy. This includes enhancing their capabilities by training their workforce and sourcing new knowledge from professional associations and suppliers. Their financial strategy involves securing EU R&D funding and obtaining government R&D contracts. Additionally, their market strategy focuses on expanding exports to European markets and emphasizing quality-based approaches.

Over the entire period, the key drivers encouraging EI in this industry were stringent regulations and the firm's sustained commitment to EI activities, followed by market-push factors and certain externalities.

8. Conclusions

This article explores the persistence of eco-innovative activities and their role in enhancing firms’ resilience during times of crisis. Using panel data from Spanish food and beverage companies from 2004 to 2016, we employ a longitudinal approach to examine how long-term commitments to eco-innovation influence green technology adoption. In this analysis, we identify three distinct periods: 2004–2007 (boom), 2008–2013 (crisis), and 2014–2016 (recovery). Additionally, we investigate the impact of regulation and other institutional interventions on promoting eco-innovation during harsh economic times—crisis and recovery. We differentiate two types of eco-innovators: efficiency-focused eco-innovators, who aim to reduce material and energy usage, and environmental eco-innovators, who seek to minimize direct harm to the environment.

Crises per se can create new opportunities for eco-innovation in this sector but in the case of Spain the effect is most pronounced for efficiency-focused eco-innovation, a pattern likely to extend to other energy –or raw material– scarce countries during economic recessions. Efficiency–focused eco–innovators are more likely to adopt countercyclical strategies, as a cost-saving response to economic hardship, compared to environmental eco-innovators.

Past eco-innovation efforts positively influence the likelihood of future eco-innovation, even during periods of economic adversity. In other words, persistence temperate the effects of crises. In the Spanish food and beverage sector, persistent eco-innovators demonstrated remarkable resilience during the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath. Firms with a consistent history of efficiency-related eco-innovation were significantly more likely to continue or expand their green activities. This highlights the strategic advantage gained from accumulated expertise and established eco innovation practices.

Our results suggest that governments and institutions may offer stimulus targeting green technologies, accelerating eco-innovation during crises (

Table 2). We found no evidence that providing subsidies to firms during difficult times promotes eco-innovation or enhances resilience. In contrast, other institutional interventions served as accelerators of green technology adoption. Regulation consistently had a positive effect throughout the business cycle. For environmental eco-innovation, government R&D contracts provided significant encouragement during the crisis and European Union R&D funding appeared to have a positive impact during the recovery period. However, these two types of interventions had limited impact on efficiency-related eco-innovation, which is typically driven by firm-level decisions. Firms, including small and regionally-focused ones, are naturally driven to conserve materials and energy.