1. Introduction

The Portuguese Newborn Screening Program started in 1979 and currently includes 28 pathologies: congenital hypothyroidism, cystic fibrosis, 24 inborn errors of metabolism, sickle cell disease and spinal muscular atrophy (pilot study). It is a public health program, carried out voluntarily, and covering the whole country, with all samples analyzed in a single national laboratory.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common severe monogenic disorders worldwide. More than 300,000 babies are born with SCD per year, and this number could rise to 400,000 by 2050. The prevalence of the disease is high throughout large areas in sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, and India because of the remarkable level of protection that the sickle cell trait provides against severe malaria. SCD has become a public health problem in Europe due to the migratory flows coming from these regions [

1,

2,

3,

4].

SCD is an autosomal recessive inherited blood condition, presenting with multisystem involvement. The mutation responsible for sickle hemoglobin (S hemoglobin) is a single nucleotide substitution of valine for glutamic acid in the 6th codon of the β-globin chain. Common genotypes associated with SCD are homozygous SS disease (HbSS) and the compound heterozygous states HbSC, HbS/β0 and HbS/β+ thalassemia. Sickle hemoglobin is characterized by reduced solubility, resulting in the development of polymers that damage red blood cells, leading to a decrease in erythrocyte lifespan. Hemolytic and vaso-occlusive phenomena lead to severe clinical complications [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The quality and average life expectancy has shown significant improvements due to the prophylactic administration of oral penicillin, anti-pneumococcal vaccination, and parental education regarding the complications associated with the pathology [

2,

9,

10,

11]. Prevention of neurological symptoms and timely therapy with hydroxyurea (hydroxycarbamide) have also contributed to improving the prognosis associated with SCD [

2,

11], although morbidity and mortality are still very high in low incoming countries.

This work presents the results of a pilot study for SCD-NBS in 188,217 Portuguese newborns (NB).

2. Materials and Methods

This pilot study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Health from the National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge.

Before starting the pilot study for SCD-NBS, and with the support of the Portuguese Association of Parents and Patients with Hemoglobinopathies, an information leaflet was prepared to be provided to the parents at pregnancy surveillance appointments or at the hospital, when the baby is born. This leaflet includes information about SCD and the advantages of SCD-NBS, thus allowing an informed decision by the parents, who were informed that they could opt in or out, regarding this study, with no implications in the other disease NBS and with no need for an additional sample.

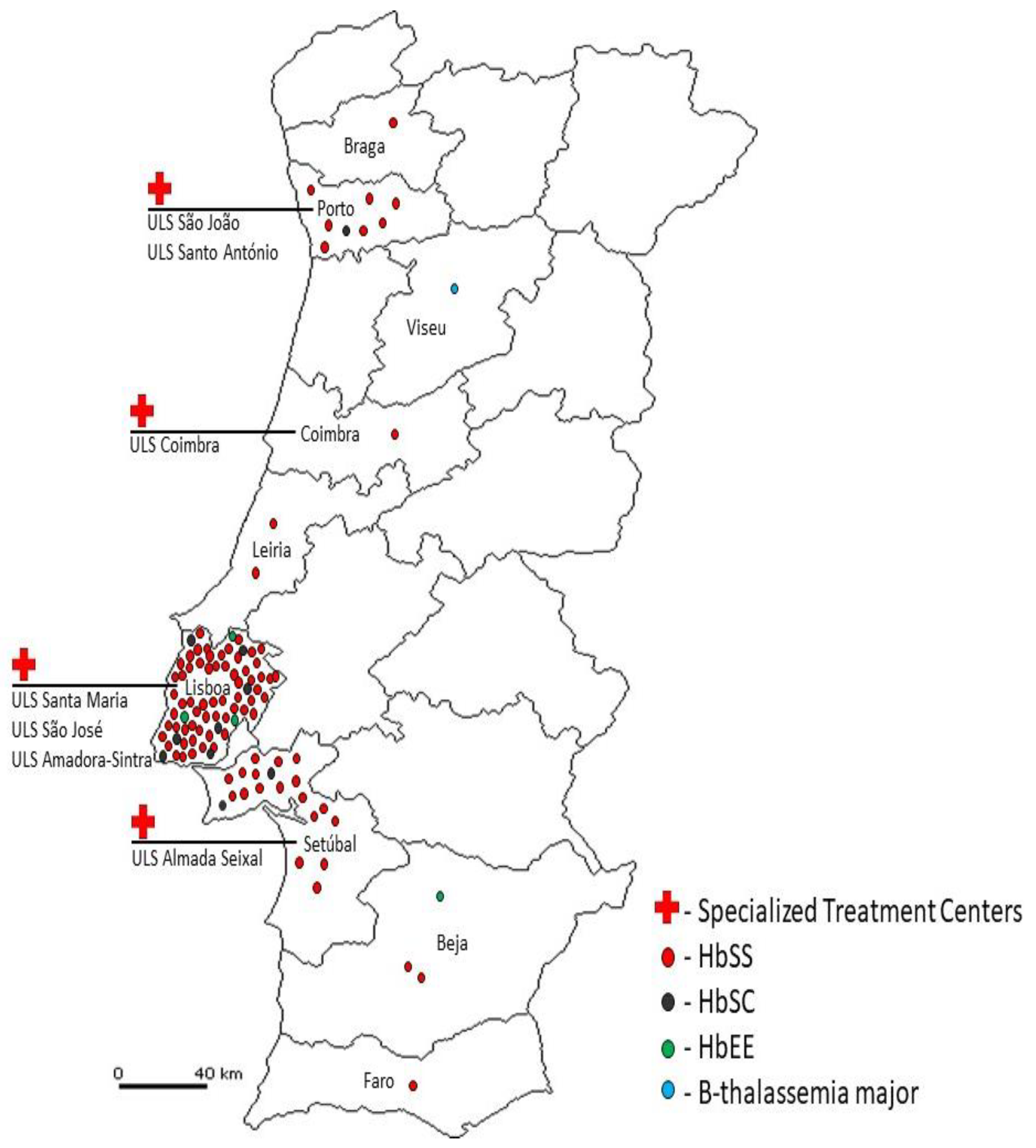

The definition of Specialized Treatment Centers for SCD, in the National Health Service, was another essential condition before starting this new screening. Seven centers having specialized pediatric hematology services, and covering all regions of Portugal, were selected for referral of positive cases identified through screening. The collaboration of these centers was requested, including contact and clinical evaluation of referred cases and all diligences to confirm the diagnosis, start adequate therapeutic measures, and follow-up all newborns.

Dried blood spot (DBS) samples, collected on Guthrie cards, between the 3rd and 6th days of life, were studied in two distinct temporal phases. In phase I, from May 2021 to January 2022, the pilot study for SCD-NBS was conducted at a regional level, in the Lisbon and Setubal districts, and 24,130 NB were screened. Phase II started in February 2022, with the expansion to a national level, and until December 2023, 164,087 additional NB were screened. It was also established, and transmitted to the sample collection centers, that for children submitted to erythrocyte transfusions before collecting the NBS sample, a second sample, collected four months after the last transfusion, was mandatory.

DBS samples were analyzed through capillary electrophoresis, using the Sebia Capillarys automated system. Capillarys 2 Neonat Fast system was used during phase I and Capillarys 3 DBS system was used during phase II.

DNA extraction and molecular characterization by Sanger sequencing or GAP-PCR was done in samples with rare hemoglobin variants.

3. Results

In phase I, 24,130 NB, from Lisbon and Setubal districts, were screened for SCD. Among these, 26 cases of SCD were identified and reported to specialized treatment centers located in this region: 24 HbSS cases and 2 HbSC cases (

Table 1).

In Phase II, 164,087 additional NB were screened. From this cohort, 67 cases for SCD were identified and referred to clinical centers: 59 HbSS cases and 8 HbSC cases (

Table 1). In

Table 1, we also present the birth prevalence of SCD in the Lisbon and Setubal districts (1:928 NB) and in the whole country (1:2,449 NB). During the pilot study for SCD-NBS, a total of 188,217 newborns were screened. Among these, 93 cases of SCD were diagnosed: 83 HbSS homozygous cases and 10 HbSC compound heterozygous cases.

Furthermore, 5 cases with other hemoglobin alterations were identified and referred for clinical evaluation, namely 4 HbEE cases and 1 β-thalassemia major case. This case was identified due to the total absence of HbA.

There were also detected 3,425 carriers of abnormal hemoglobins, of which: 626 in phase I and 2,799 in phase II. Heterozygotes for abnormal hemoglobin variants were not reported, but it’s worth highlighting that the prevalence at birth of sickle cell trait in the districts of Lisbon and Setubal (1:45 NB) is remarkably higher than the one found in the whole country (1:70 NB) (

Table 2).

The cases presenting HbA and an abnormal hemoglobin variant were considered normal carriers of an Hb variant, and a negative result for SCD screening was communicated to the parents. Nevertheless, when an abnormal hemoglobin variant, not identified by the Sebia software, was detected in a sample also presenting HbA, the sample was anonymized and further studied at the molecular level. The most frequent abnormal hemoglobin variant was Hb Bart’s, in samples with homozygous alpha 3.7 deletion. We found also carriers of variants in the alpha genes, namely Hb J-Paris I (HBA2:c.38C>A;p.Ala13Asp); Hb Oleander (HBA2:c.349G>C;p.Glu117Gln), Hb Chad (HBA1:c.70G>A;p.Glu24Lys) and Hb J-Singa (HBA2:c.235A>G; p.Asn79Asp).

4. Discussion

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations recently identified SCD as a global health burden, and it is largely accepted that optimal care for affected children begins with NBS. In 2016, it was recognized that, due to a large migrant flow from Middle East and Africa, SCD become present in all European countries with increasing prevalence [

12]. SCD has become a public health issue and a challenge for European healthcare systems. This fact prompted a pan-European consensus conference in 2017, resulting in the recommendation for universal SCD-NBS inclusion in all European NBS programs.

England was the first European country to introduce nationwide SCD-NBS (2006) [

13], and later, it was extended to the United Kingdom (2014). Netherlands (2007), Spain (2015) and Malta (2017) have also included SCD-NBS in their national newborn screening panel. In some other European countries, this screening was started at a regional level, depending on the particular characteristics of the populations: in Belgium, screening is carried out only in the regions of Brussels and Liège; in Germany, it is conducted in the regions of Berlin, Hamburg, and Southwest Germany. In Italy, universal SCD screening is performed in the Padova-Monza region, while in Novara, Ferrara and Modena SCD screening is targeted. This is also the case for Ireland and France [

3,

4].

In 1986, a National Program for Hemoglobinophaties Control was implemented in Portugal, in a collaboration with WHO, and with the coordination of the Portuguese National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (INSA), a lot of research work was performed in this field. SCD, β-thalassemia major and intermediate are the most common severe forms of hemoglobinophaties in Portugal, and they are more frequent in the Center and South of the country. SCD was found to be especially present among African-originating communities [

9,

14,

15,

16].

To fully understand the Portuguese situation, it is necessary to frame the impact of migratory flows that have historically occurred in Portugal. Throughout our history, several moments have been marked by the influx of immigrants from regions considered at risk for SCD. One example is the large influx of immigrants from Africa in the post-colonial period, who settled in Portugal, mainly in the Lisbon metropolitan area [

17,

18]. Another relevant moment was Portugal’s integration into the European Union, leading to the a new influx of immigrants from African countries, especially from Portuguese-Speaking African Countries, such as Cape Verde, Angola, and Guinea-Bissau, as well as from other regions of the globe, with a special emphasis on Brazil [

18]. More recently, it has been observed that immigrants from Brazil have become the most significant migratory group in the resident population of Portugal. Together with immigrants from Angola, Cape Verde, and Guinea-Bissau, they represent more than half of the resident population with foreign nationality and their presence is no longer restricted to the Lisbon metropolitan area, but they are distributed throughout all the national territory [

19]. In addition to immigrants from Africa and Latin America, Southwest Asia has also contributed to the growth of the immigrant population in Portugal, consequently leading to the spread of hemoglobinopathies, particularly SCD. The need to early identify these patients is even more pressing, knowing that most of them arise within immigrant communities with low socio-economic conditions.

For this reason, the study was started first in the districts of Lisbon and Setubal, where these communities are largely present, and later extended to a national level.

This pilot study led to the identification of 93 SCD patients (83 HbSS; 10 HbSC), 4 HbEE homozygous and 1 β–thalassemia major (

Figure 1), that are being properly followed by hematologists in Specialized Treatment Centers.

Additionally, it was possible to identify 3,425 carriers of abnormal hemoglobins: 2,884 HbAS, 251 HbAC, 168 HbAD and 122 HbAE.

The results obtained in phase I confirm a high birth prevalence of SCD (1:928 NB) in the Lisbon and Setubal districts, where 2.2% of the NB are carriers of hemoglobin S. The results obtained in phase II are more representative of the Portuguese situation, with a SCD—birth prevalence of 1:2,449 NB, and 1.4% of hemoglobin S carriers.

As suspected, the contribution of the two districts studied in phase I is significantly higher, confirming that it is the region of the country with the highest birth prevalence of SCD. This difference is easily justified by the high number of African-descendent immigrants found in these two districts since already many years, constituting large communities, among which intermarriage is very common, and thus contributing even more for the increase of SCD-positive cases. Even if in other regions of Portugal the incidence of SCD is much lower (1:7,783), the detection of 13 cases out of Lisbon and Setubal indicates that the disease is also present there and for the historical reasons already discussed it will probably soon became more significant, thus justifying that this screening will continue at a national level.

5. Conclusions

In May 2021, the pilot study for SCD-NBS was initiated in Portugal, in the districts of Lisbon and Setubal (Phase I), revealing a birth prevalence for SCD of 1:928 NB. Subsequently, in February 2022, this pilot study was expanded to include all newborns in Portugal (Phase II), revealing a birth prevalence of 1:2,449 NB until December 2023. With the results obtained during the phase II, we conclude that this condition is increasingly relevant in Portugal, following the European trend where SCD is already recognized as a public health problem. All of this supported the integration of SCD into the panel of the Portuguese Newborn Screening Program in January 2024.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: D.R., A.M. and L.V.; Data curation: D.R., A.M., A.V., T.F., A.F., C.G., P.K., A.C., S.F., M.A., T.M., J.G., A.L., I.G., F.F., F.T., C.B. and L.V.; NBS methodology, validation and formal analysis: D.R., A.M. and L.L.; investigation: D.R., A.M., L.L., L.V. and C.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R. and A.M.; writing—review and editing: D.R., A.M., L.V. and C.B.; supervision: L.V.; project administration: L.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for the pilot study was provided by NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HEALTH DOUTOR RICARDO JORGE, which supports the National Neonatal Screening Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board and Health Ethics Committee of National Institute of Health Doutor Ricardo Jorge (CES-12022019, approved on 14 May 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We thank all those that contributed and supported this work. This includes the Portuguese Association of Parents and Patients with Hemoglobinopathies (APPDH), Dr Cristina Trindade (Cascais Hospital, Lisboa), Dr Rui Pinto (ULS Gaia/Espinho, Gaia) and all clinicians envolved in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Piel, F.B.; Steinberg, M.H.; Rees, D.C. Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, D.C.; Williams, T.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet 2010, 376, 2018–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobitz, S.; Telfer, P.; Cela, E.; Allaf, B.; Angastiniotis, M.; Backman Johansson, C.; Badens, C.; Bento, C.; Bouva, M.J.; Canatan, D.; Charlton, M.; Coppinger, C.; Daniel, Y.; de Montalembert, M.; Ducoroy, P.; Dulin, E.; Fingerhut, R.; Frömmel, C.; García-Morin, M.; Gulbis, B.; Holtkamp, U.; Inusa, B.; James, J.; Kleanthous, M.; Klein, J.; Kunz, J.B.; Langabeer, L.; Lapouméroulie, C.; Marcao, A.; Marín Soria, J.L.; McMahon, C.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Périni, J.M.; Piel, F.B.; Russo, G.; Sainati, L.; Schmugge, M.; Streetly, A.; Tshilolo, L.; Turner, C.; Venturelli, D.; Vilarinho, L.; Yahyaoui, R.; Elion, J.; Colombatti, R. ; with the endorsement of EuroBloodNet, the European Reference Network in Rare Haematological Diseases. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in Europe: recommendations from a Pan-European Consensus Conference. Br. J. Haematol. 2018, 183(4), 648-660. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel, Y.; Elion, J.; Allaf, B.; Badens, C.; Bouva, M.J.; Brincat, I.; Cela, E.; Coppinger, C.; de Montalembert, M.; Gulbis, B.; Henthorn, J.; Ketelslegers, O.; McMahon, C.; Streetly, A.; Colombatti, R.; Lobitz, S. Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Europe. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019, 5(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Piel, F.B.; Patil, A.P.; Howes, R.E.; Nyangiri, O.A.; Gething, P.W.; Dewi, M.; Temperley, W.H.; Williams, T.N.; David J Weatherall, D.J.; Hay, S.I. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: a contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013, 381, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Piel, F.B.; Steinberg, M.H.; Rees, D.C. Sickle Cell Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serjeant, G.R.; Vichinsky, E. Variability of homozygous sickle cell disease: The role of alpha and beta globin chain variation and other factors. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2018, 70, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, R.E.; Montalembert, M.; Tshilolo, L.; Abboud, M.R. Sickle cell disease. Lancet 2017, 390, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.J.; Carreiro, M.H.; Machado, M.C.; Seixas, T.; Picanço, I.; Batalha, L.; Lavinha, J.; Martins, M.C. Rastreio neonatal de hemoglobinopatias numa população residente em Portugal. Acta Med. Port. 1996, 9, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Costa, S.N.; Madeira, S.; Sobral, M.A.; Delgadinho, G. Hemoglobinopatias em Portugal e a intervenção do medico de família. Rev. Port. Med. Geral Fam. 2016, 32, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco Sánchez, J. M.; Sánchez Magdaleno, M.; González Prieto, A.; Riesco Riesco, S.; Mendoza Sánchez, M. C.; Herraiz Cristóbal, R.; Portugal Rodríguez, R.; Moreno Vidán, J. M; Muñoz Moreno, A. C. Cribado neonatal de drepanocitosis en Castilla y León: Estudio descriptive. Bol. Pediatr. 2021, 61, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Inusa, B.P.D.; Colombatti, R. ; European migration crises: The role of national hemoglobinopathy registries in improving patient access to care. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2017, 64(7). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streetly, A.; Sisodia, R.; Dick, M.; Latinovic, R.; Hounsell, K.; Dormandy, E. Evaluation of newborn sickle cell screening programme in England: 2010–2016. Arch. Dis. Child 2017, 0, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Martins, M.C.; Olim, G.; Melo, J.; Magalhães, H.A.; Rodrigues, M.O. Hereditary anaemias in Portugal: epidemiology, public health significance, and control. J. Med. Genet. 1993, 30, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Monteiro, C.; Rueff, J.; Falcao, A.B.; Portugal, S.; Weatherall, D.J.; Kulozik, A.E. The frequency and origin of the sickle cell mutation in the district of Coruche/Portugal. Hum. Genet. 1989, 82, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.T.; Garcia, C.; Ferreira, T.; Dias, A.; Trindade, C.; Barroso, R. Neonatal Screening for Haemoglobinopathies: The Experience of a Level II Hospital in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area. Acta Pediatr. Port. 2018, 49, 228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Maurice, A.; Pires, R.P. Descolonização e migrações: Os imigrantes PALOP em Portugal. Rev. Int. Estud. Afr. 1989, 10, 203–226. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, J. Africanos e Afrodescendentes no Portugal Contemporâneo: Redefinindo práticas, projetos e identidades. Cad. Estud. Afr. 2012, 24, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Censos 2021. XVI Recenseamento Geral da População. VI Recenseamento Geral da Habitação: Resultados definitivos. Lisboa: INE; 2022. https://www.ine.pt/xurl/pub/65586079. ISSN 0872-6493. ISBN 978-989-25-0619-7.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).