1. Introduction

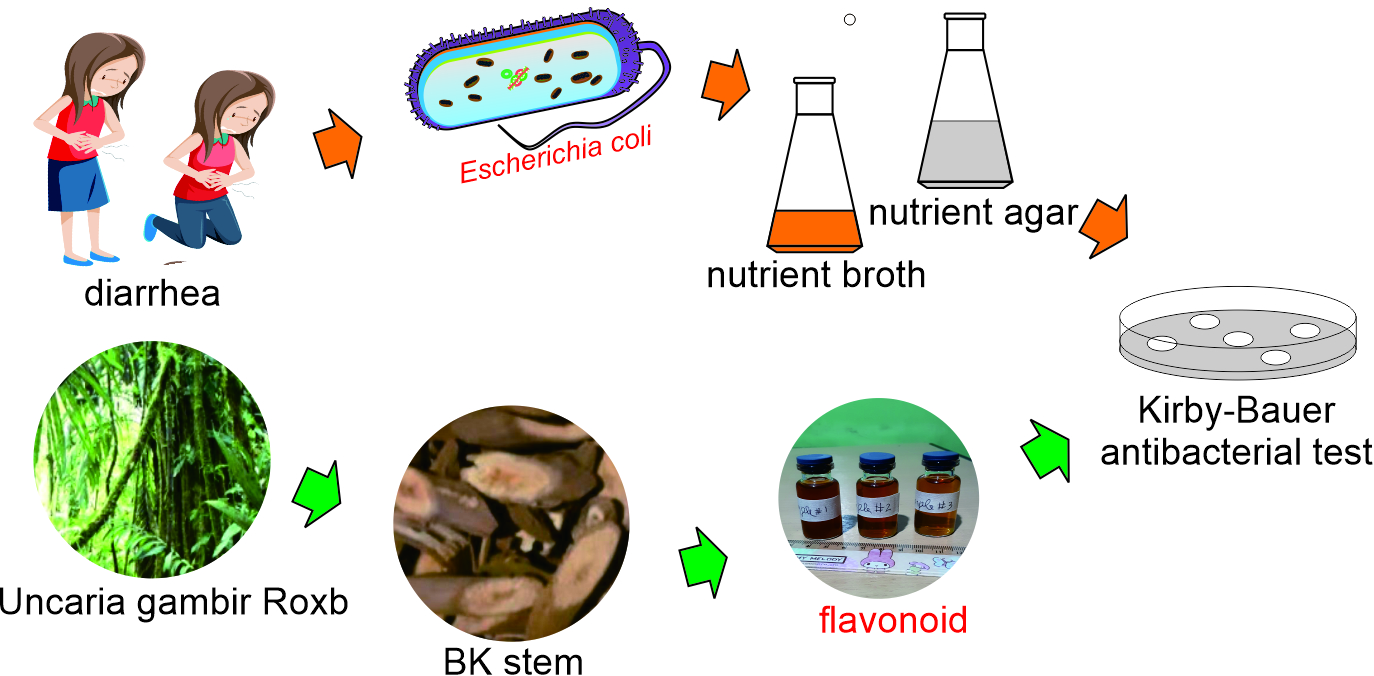

Among 40.000 known medicinal plants worldwide, 30.000 of them present in the tropical forest of Indonesia [

1]. However, only 200 of them have been exploited for medicine [

2]. One such species is

Bajakah Kalalawit, scientifically known as

Uncaria gambier Roxb. (UGR) which mostly found in tropical forest of Indonesian island of Borneo. Indigenous Dayak people have been utilizing this plant for centuries as traditional medicine to treat diarrhea, open wounds, and cancer. This drew our attention to scientifically investigate the content of UGR as raw material for modern medicine.

The number of children diarrhea cases reported in Indonesia reaches 1.7 billion per year and most of them caused by

Escherichia coli (

E. coli). The death rate reaches around 525,000 children under 2 years of age [

3]. Therefore, exploring UGR as a raw material for antibiotics will save many children's lives.

Bajakah Tampala has been researched to contain flavonoids which have been proven to have antibacterial property [

4]. We believe UGR also has a high flavonoid content so it is worthy of being explored as a raw material for antibacterial drugs. The abundance of UGR on the island of Borneo guarantees the sustainability of its supply.

Flavonoid compounds are found as secondary metabolites in various plants; however, their concentration varies from one plant to another and even from one part of the same plant to another [

5]. Indeed, the same species growing in different areas may exhibit different flavonoid concentrations. Numerous factors, including soil type, pH, nutrients (including fertilizer), water availability, climate, and sunlight exposure, contribute to plant growth and the production of flavonoids in each plant [

5,

6]. Therefore, plants growing in their original habitat in the rainforest, which is rich with nutrients, water, sunlight, and favorable climate conditions, are assumed to have higher flavonoid content. Flavonoid certainly has antibacterial properties [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Flavonoid as antibacterial agent has been widely studied therefore many proposed mechanisms of action of flavonoid inhibiting and killing bacteria available in many publications.

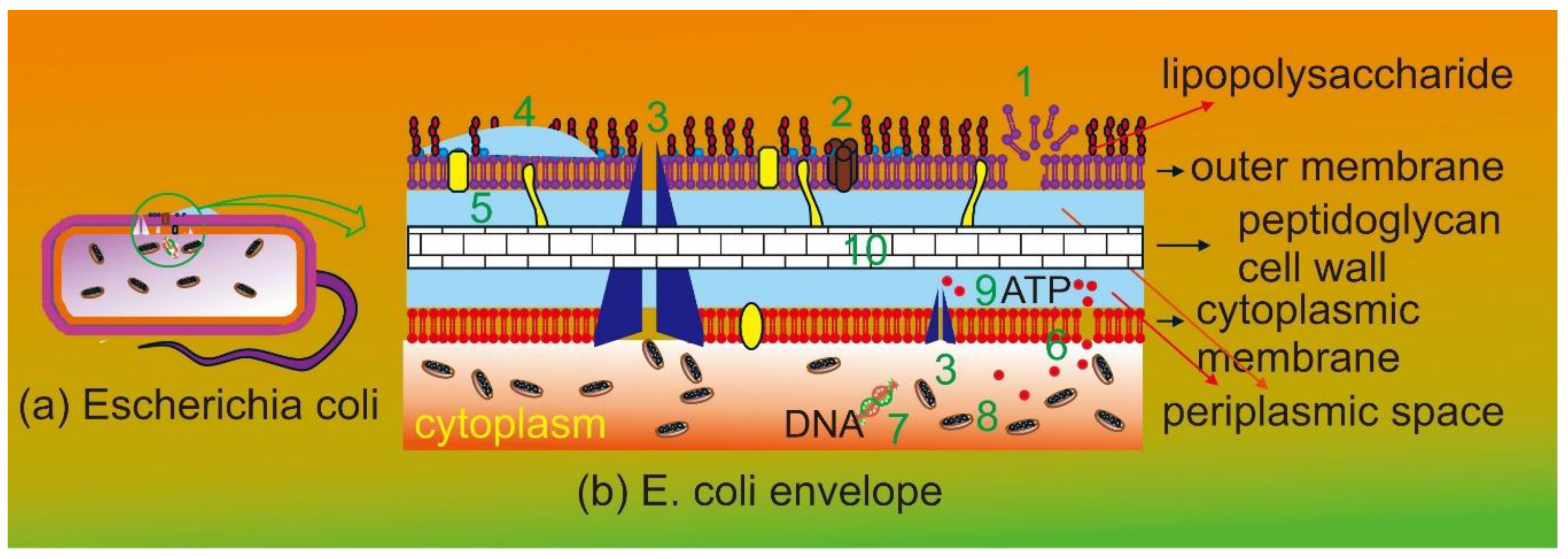

Figure 1(a) is pictorial representation of

E. coli showing two membranes and a cell wall in between.

Figure 1(b) is schematic representation of Gram-negative bacteria highlighting envelope consisting of cytoplasmic membrane, peptidoglycan cell wall, periplasmic space, and outer membrane and the summary ten mechanisms of action of flavonoid against bacteria. These include cytoplasmic membrane function disruption, porin, efflux pump, biofilm, peptidoglycan synthesis, and nucleic acid synthesis inhibition. Flavonoid can also disrupt energy metabolism in cytoplasm, electron transfer and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production in periplasmic space. Many mechanisms of action of flavonoid work simultaneously at different parts of bacteria making it a powerful antibacterial agent. This is the reason of choosing flavonoid for this research.

Escherichia coli ATCC 11229 (

E. coli) is a cylindrical-shaped bacterium commonly found in the human gastrointestinal tract. These bacteria have spread worldwide and have developed numerous strains. Some of these strains are pathogenic [

22,

23] and can cause serious illnesses such as hemorrhagic colitis which is severe watery diarrhea accompanied by sudden stomach cramps and possible vomiting.

E. coli forms biofilms to trap food, defend against immune cells, protect against antibacterial agents, and spread virulence [

24]. These Gram-negative bacteria are protected by double-layered membranes with a cell wall located between these membranes [

25]. Penetrating the double protection of

E. coli is extremely challenging. Many research groups reported that

E. coli developed resistance to many bacteria [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, there is a pressing need for more extensive research to develop stronger antibacterial agents to fight

E. coli [

30]. This is the reason why we chose

E. coli for this research, apart from the fact that it caused billions of infections and killed millions of children per year. One effective approach to combat multi-resistant bacteria is to explore antibacterial agents based on traditional medicine, which have shown efficacy over decades.

Another candidate as raw material of antibacterial drug is silver nanoparticles. Many research teams have demonstrated effectiveness as antibacterial agents in vitro [

31,

32]. The efficacy of silver nanoparticles is not only attributed to the novel metal properties of silver metal but also to their extremely small size. Nanoparticles possess a higher specific surface area [

33], so that they can interact with more bacteria, leading to increased bacterial death. We are reporting our efforts to produce flavonoid bio-nanoparticles as part of ongoing research aimed at creating a single product that combines chemical and physical antibacterial agents. We used dynamic light scattering to characterize these bio-nanoparticles [

34,

35]

In this paper, we present a comprehensive methodology for the extraction of flavonoids from UGR utilizing the decoction method. The total flavonoid content was determined through the aluminum chloride colorimetric assay [

36] using a visible spectrophotometer [

37]. We compare the concentration of total flavonoids extracted from UGR with several other medicinal plants from Indonesia [

38], India [

39], and China [

40]. Our study not only examines the efficacy of flavonoids as antibacterial agents against

E. coli using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method[

41] but also compares their effectiveness with Chloramphenicol.

E. coli developed strong resistance to Chloramphenicol starting at 39 h. In contrast,

E. coli did not show any resistance to flavonoid until the last observation at 75 h. All these findings promise valuable insights into the potential of flavonoids as natural antibacterial agents [

10].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

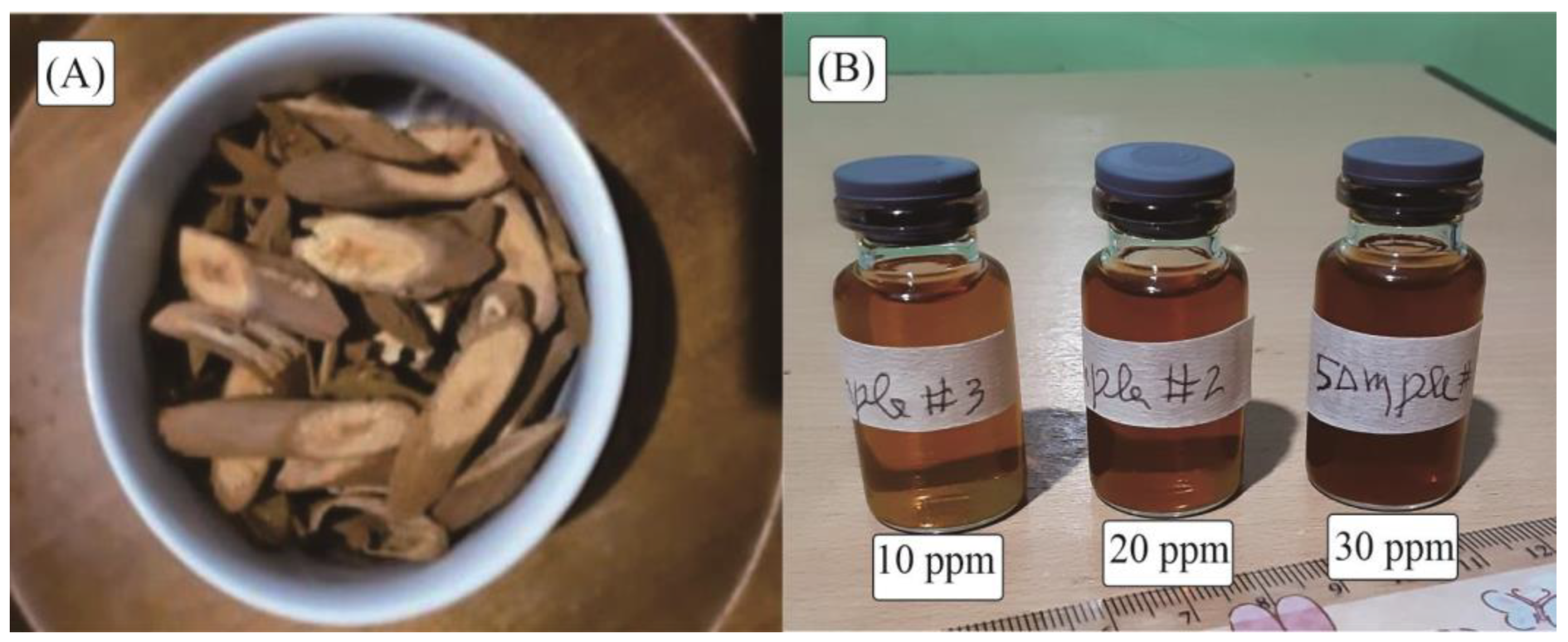

The main material UGR was purchased from Landak regency, West Kalimantan province in the Indonesian island of Borneo. The decoction process involves boiling of small pieces of UGR stem in water to release its secondary metabolites and suspending them in the water [

42]. This method was selected to reproduce the traditional medicine preparation of the Dayak tribes. To begin, 50 grams of UGR were combined with 500ml of water in a one-liter glass beaker and heated until boiling, reducing the water volume to 250ml—a process taking approximately 52 minutes to halve the initial volume. The larger pieces of UGR were then removed, and the remaining solution was filtered using a coffee filter, resulting in a brownish UGR extract.

Figure 2(A) shows small pieces of UGR which are ready for decoction and

Figure 2(B) shows extract UGR containing 10 ppm, 20 ppm, and 30 ppm flavonoid.

2.2. Flavonoid Concentration Determination

AlCl

3 colorimetric assay was used to determine the concentration of flavonoid [

43]. To prepare the sample, 0.5ml of UGR extract was diluted in 4.5 ml of ethanol (dilution factor D

F = 10). Quercetin powder from Sigma Aldrich was used to prepare 5 different concentrations of quercetin samples which were 6ppm, 8ppm, 10ppm, 12pp, and 14ppm. To determine the absorbances of the quercetin samples, 0.1mL of 10% aluminum chloride (AlCl

3), 0.1mL of 1 Molar potassium acetate (CH

3COOK), 1.5mL of ethanol, and 2.8ml of water were added to 0.5ml of each quercetin sample. The same amount of aluminum chloride assay was added to diluted flavonoid sample to determine the absorbance of diluted flavonoid sample. These 5 quercetin samples were incubated 30 minutes at 25

o C.[

44] The measurements of absorbances were done using visible spectrophotometer by scanning between (400-800) nm and found the absorption peak at 435nm. The results were used to draw a calibration curve and it was found the linier regression equation is Y= 0.0423X + 0.034 and R

2= 0.9974. This linier regression equation was then used to calculate the concentration of diluted flavonoid. The total flavonoid concentration of the UGR extract was calculated using Equation (1).

where C

T represents total flavonoid concentration, C denotes the concentration of the diluted flavonoid sample, V stands for volume, D

F is the dilution factor, and m is the mass.

2.3. Flavonoid Bio-Nanoparticle Preparation and Size Measurement

To prepare flavonoid bio-nanoparticles, the flavonoid extract underwent a filtration process using 0.22-micrometer Millipore filters on a syringe. Subsequently, the filtered extract was centrifuged at a speed of 4000rpm three times for 10 minutes each to separate large particles from the supernatant [

45]. The supernatant was then transferred from centrifuge tube to a cuvette using a pipet. It must be done gently since the sediment easy to break upon syringe sucking. Particle size determination was conducted using a laser amplified detection (LAD) method, the latest innovation of dynamic light scattering (DLS) technique [

34].

2.4. Antibacterial Observation

Prior to the experiment, nutrient broth (NB), a liquid medium which is nutrients rich, conducive to

E. coli growth and nutrient agar which is a solid medium used to test antibacterial agents, had to be prepared [

46]. The inhibition of flavonoids was observed in a petri dish, containing nutrient agar riches with

E. coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers ATCC 11229 strain AMC 198 where 5 impregnated disks containing flavonoid at concentration of 10ppm, 20ppm, and 30ppm labeled as A, B, and C, respectively. One disk impregnated with water as a negative control (D) and another disk containing chloramphenicol 5% (E) as a positive control. The clear zone diameter representing antibacterial agent efficacy around the disks was measured 3 times at different positions [

47] horizontally, vertically, and diagonally. Measurements were taken every 3 h over a period of 75 h.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The measurement of physical quantity was carried out three times each and the presented data were the average of these three measurements except DLS data which were averaged of five performed by the software. The clear zone diameter data of four groups of antibacterial agents were compared one to another by performing t-test analysis: two samples assuming unequal variances. The comparisons were done between 5% chloramphenicol and 30 ppm flavonoid, between 5% chloramphenicol and 20 ppm flavonoid, between 5% chloramphenicol and 10 ppm flavonoid, between 30 ppm flavonoid and 20 ppm flavonoid, between 30 ppm flavonoid and 10 ppm flavonoid, and between 20 ppm flavonoid and 10 ppm flavonoid. The null hypothesis of the comparison of 5% chloramphenicol and 30 ppm flavonoid, Ho: there is no significant difference in the clear zone diameter between 5% chloramphenicol qand 30 ppm flavonoid. The alternative hypothesis (Ha): there is a significant difference in the clear zone diameter between the two groups. Both hypotheses apply to all the above comparisons and all two-tailed p-values of t-test analysis are presented in

Table 2.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.1. The Result of Total Flavonoid Concentration Calculation

The absorbance measurements of the diluted flavonoid sample using visible spectrophotometer were conducted three times, and the results are presented in Column 2 of

Table 1. The calculations of the diluted flavonoid concentrations using the linier regression equation based on these absorbances, are presented in

Table 1, Column 3. These three calculated diluted flavonoid concentrations were then utilized to compute the total flavonoid content using Equation (1). The resulting total flavonoid contents are provided in Columns 7 of

Table 1. The average and standard deviation of these total flavonoid contents are presented in the last column of

Table 1. The total content of flavonoid of UGR extract was (31.55 ± 0.29) mg QE/g.

3.2. Flavonoid Bio-Nanoparticle Characteristics

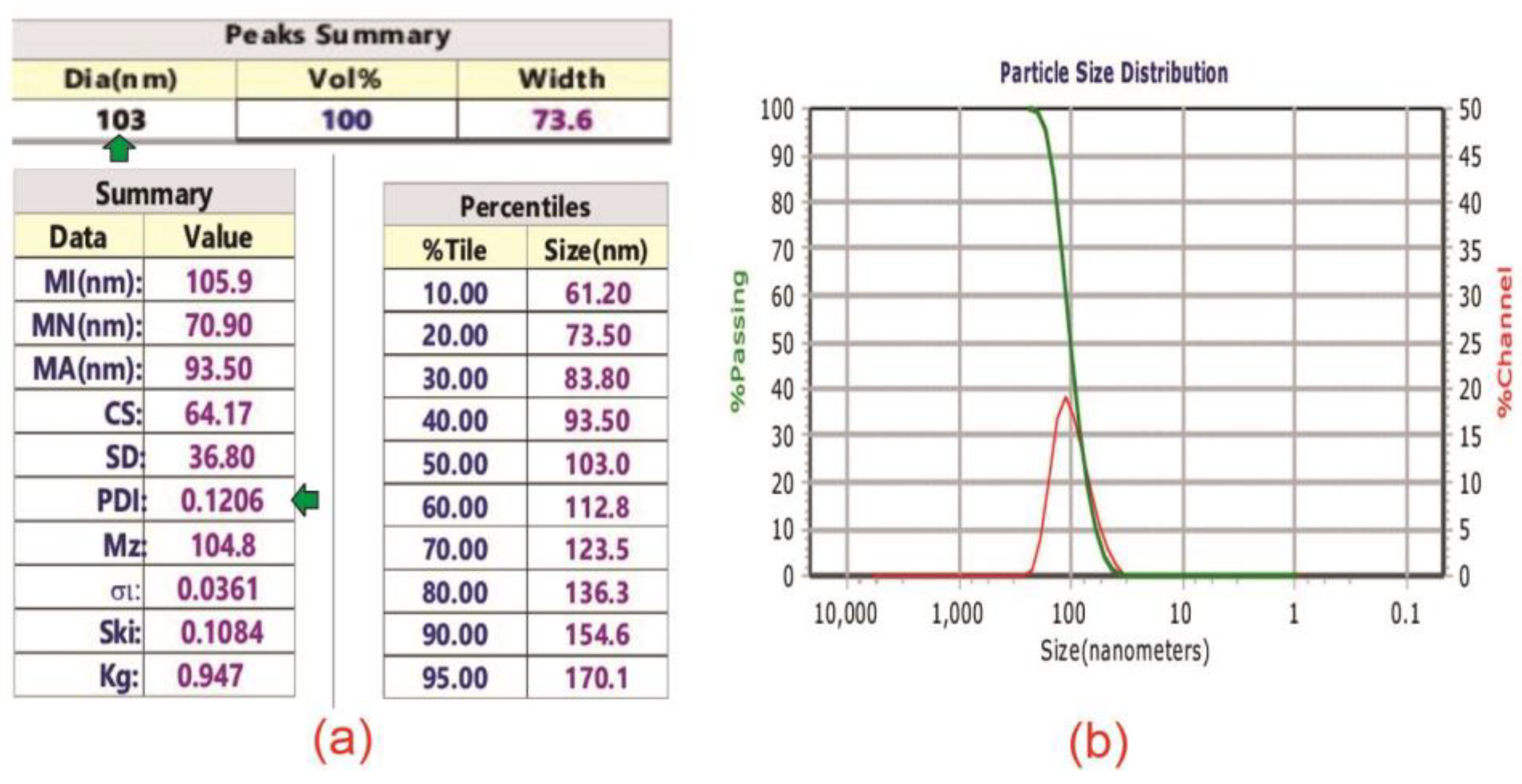

The results of flavonoid bio-nanoparticle size measurement are presented in

Figure 3.

Figure 3a on the left displays polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.1206 (horizontal green arrow) and average flavonoid bio-nanoparticle size of 103 nm (vertical green arrow).

Figure 3b shows particle size distribution (depicted by red curve) showing a normal Gaussian distribution graph.

3.3. Flavonoid Antibacterial Efficacy

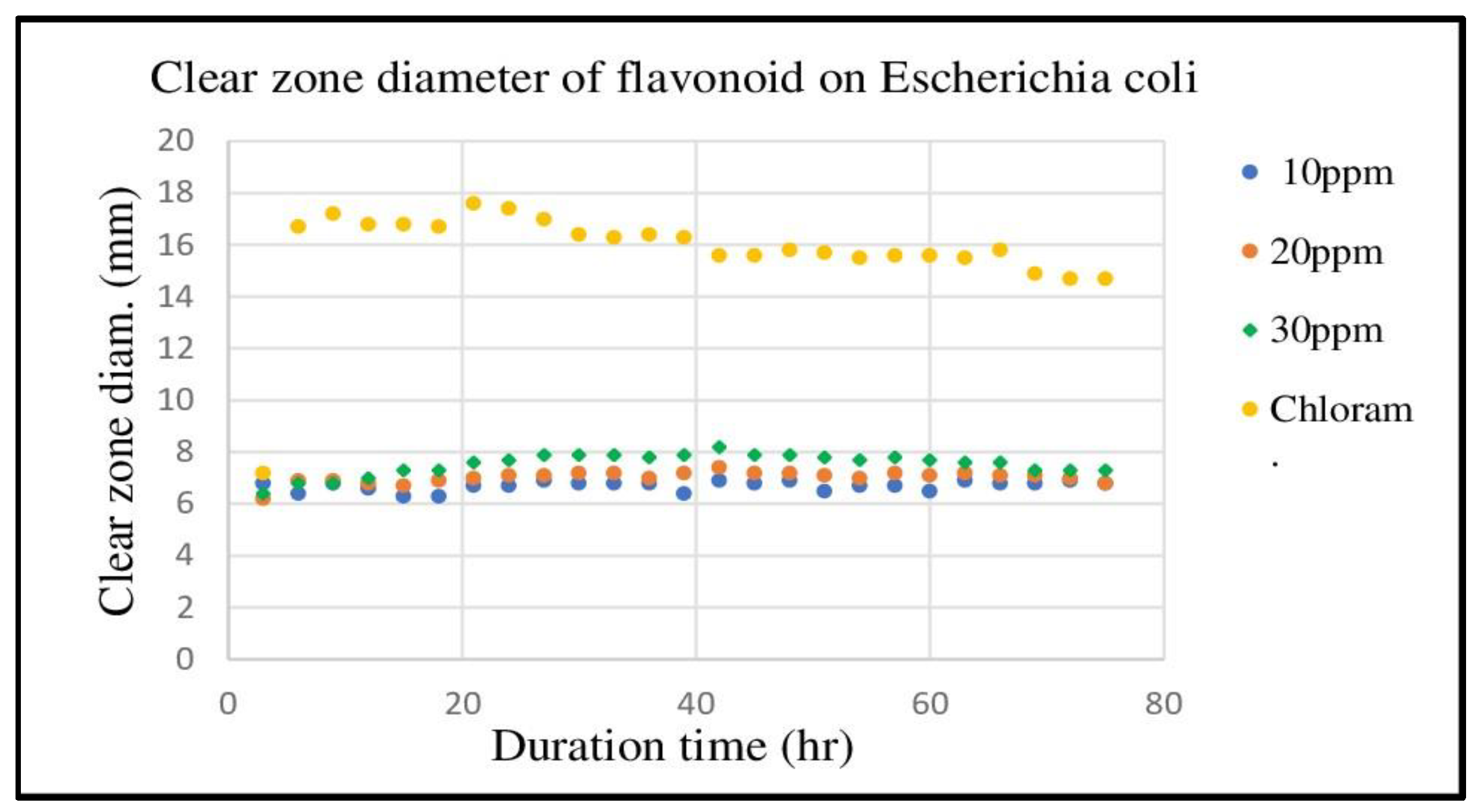

The results of clear one diameter measurements are presented in

Figure 4. This figure shows the clear zone diameter of three flavonoid samples (10 ppm, 20 ppm, and 30 ppm) and chloramphenicol 5%. The average clear zone diameters of flavonoids 10 ppm, 20 ppm, and 30 ppm were (6.69 ± 0.19) mm, (7.02 ± 0.23) mm, and (7.54 ± 0.42) mm, respectively. These results confirm that flavonoids extracted from UGR exhibit antibacterial activity. In contrast, disk D did not display a clear zone, indicating that water did not inhibit the growth of

E. coli [

48] On the other hand, disk E showed a relatively large clear zone diameter with the average of (15.79 ± 1.91) mm, indicating that chloramphenicol has a strong antibacterial efficacy against these bacteria.[

49] All p-values of statistical analysis are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2.

P two-tail values of comparison Chloramphenicol and Flavonoids.

Table 2.

P two-tail values of comparison Chloramphenicol and Flavonoids.

| Chloramphenicol |

Flavonoid |

P two-tail value |

| 5% |

- |

- |

30 ppm |

1.50 x 10-17

|

| 5% |

- |

20 ppm |

- |

5.77 x 10-18

|

| 5% |

10 ppm |

- |

- |

6.87 x 10-18

|

| - |

- |

20 ppm |

30 ppm |

7.45 x 10-6

|

| - |

10 ppm |

- |

30 ppm |

3.17 x 10-10

|

| - |

10 ppm |

20 ppm |

- |

2.75 x 10-6

|

3.4. Escherichia coli Resistance Development

The observation on E. coli resistance development is also presented in

Figure 4. This figure illustrates that after 39 h in contact with E. coli, the clear zone diameter of chloramphenicol consistently decreases until the last measurement at 75 h. In contrasts, E. coli did not show any resistance developments in all flavonoid concentrations up to the last measurement at 75 h.

4. Discussion

The total content of flavonoid extracted from UGR notably surpasses the flavonoid content of 30 other Indonesian medicinal plants. Among these 30 medicinal plants the highest flavonoid content was found in

Cosmos caudatus at (29.93 ± 0.01) mg QE/g.[

38] When compared to other regional medicinal plants from India and China, the flavonoid content in UGR remains notably superior. Sulaiman, C.T. and colleagues reported data on the flavonoid content of 21 Indian medicinal plants, revealing that all plants exhibited flavonoid content of less than 10mg QE/g, except for

Senna tora (L.) Roxb which displayed (21.58 ± NA) mg QE/g.[

39] Similarly, Li, M. and colleagues published data on 93 Chinese medicinal plants, where most plants exhibited flavonoid content of less than 10 mg QE/g, with only 12 plants surpassing this threshold.[

40] The highest flavonoid content of the Chinese medicinal plants was observed in

Linocera japonica Thunb at (13.85± 0.58) mg QE/g. These comparisons further underscore the superiority of UGR's flavonoid content, solidifying its status as a prominent source of flavonoids.

It was found that the average size of flavonoid bio-nanoparticle is 103nm, the PDI was 0.1206, and size distribution is a tight bell-like graph. This size is quite close to the upper limit of nanoparticles, namely 100nm [

50]

. The 3% difference is still within acceptable standard deviation. The PDI of 0.1206 indicates that the sample is in good quality since the relatively low value of PDI indicates relatively low heterogeneity of solution [

51]. This is supported by the tight bell-like graph of size distribution in

Figure 3 (B) showing that the solution is relatively homogeneous. The implication of the successful synthesis of bio-nanoparticles is that it opens opportunities to produce chemical and physical antibacterial agents in one product. The small size of particle enables it to diffuse into cytoplasm through porin in the outer membrane [

52,

53]. Such products are expected to increase efficacy in combating bacteria which is resistance to chemical antibacterial agents including

E. coli [26,54,55,56].

Statistical analysis was performed as part of comparative study between chloramphenicol and flavonoid (10 ppm, 20 ppm, 30 ppm). The results of the t-test analysis presented in

Table 2 show that the p-values of the three comparisons are smaller than 0.05 so that all null hypotheses are rejected. This rejection shows that the efficacy of 5% chloramphenicol is significantly higher than flavonoids at concentrations of 10 ppm, 20 ppm and 30 ppm. These results give an impression that flavonoid is inferior compared to chloramphenicol. More detailed analysis shows that the data were collected in different concentration units (flavonoid in ppm and chloramphenicol in %). Therefore, in depth analysis required for this comparative study.

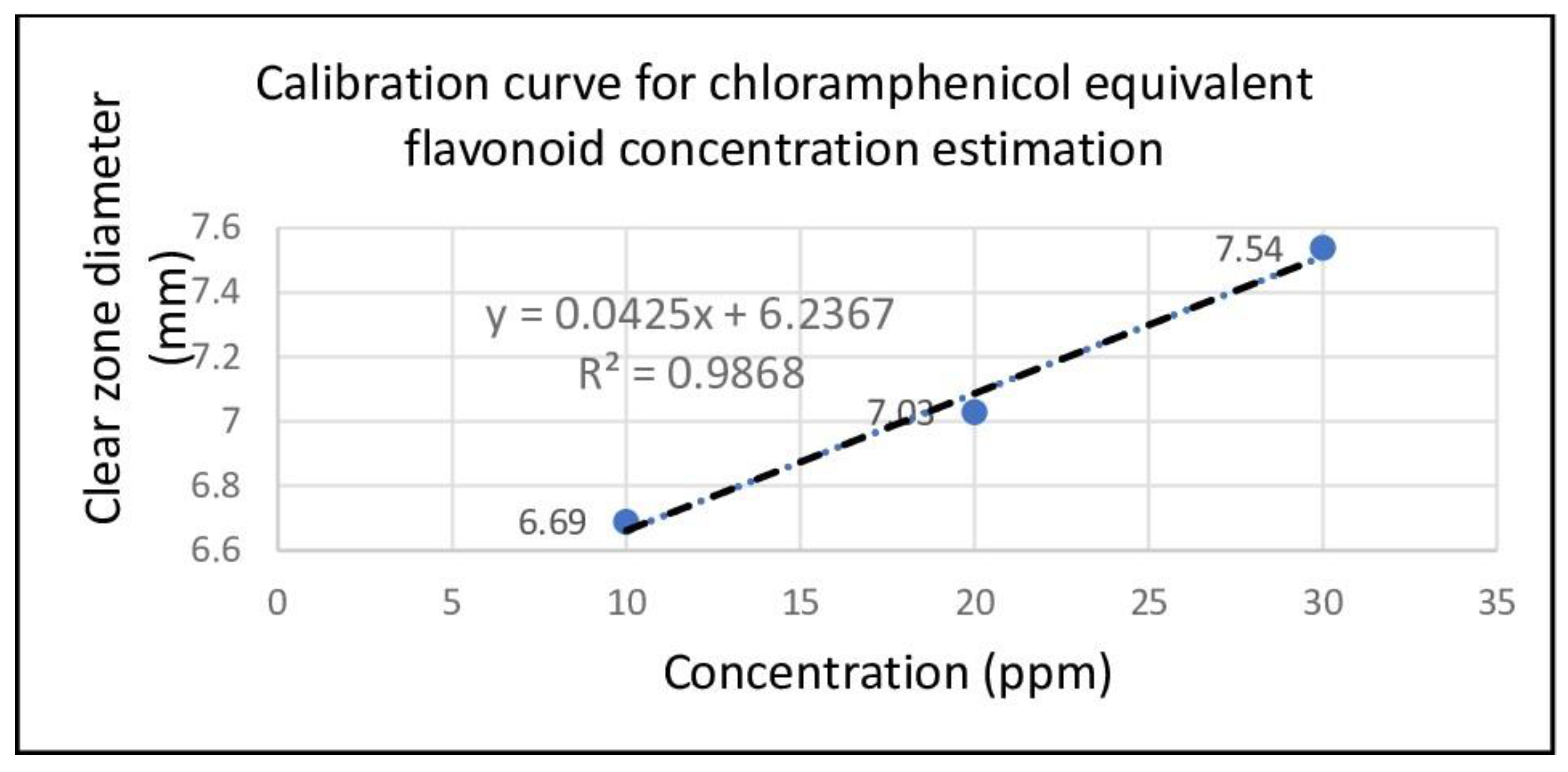

The p-values of t-test analysis comparing clear zone diameters of flavonoid between 30 ppm and 20 ppm, between 30 ppm and 10 ppm, and between 20 ppm and 10 pm are presented in

Table 2. The p-values of comparisons between 30 ppm and 20 ppm and between 30 ppm and 10 ppm are 7.45 x 10

-6 and 3.17 x 10

-10, respectively. Since p-values are less than 0.05 therefore Ho hypotheses of both comparisons are rejected so that 30 ppm produces significantly larger clear zone diameter than 20 ppm and 10 ppm. The same result goes to the comparison between 20 ppm and 10 ppm with p-value of 2.75 x 10

-6. This means that 20 ppm flavonoid produces significantly larger diameter than 10 ppm. This statistical analysis shows that clear zone diameter of flavonoid increases with the increase of concentration. The implication of this analysis is that a calibration curve (or more precisely a prediction curve) can be created to predict the diameter of the clear zone with greater concentrations. The linear regression equation for this prediction curve is Y=0.0425 + 6.2367 with R

2 = 0.9868 (see

Figure 5). Using this equation, 5% flavonoids (equivalent to 50,000 ppm) can produce a clear zone diameter of 2131.2 mm, equivalent to 134.9 times the clear zone diameter produced by 5% chloramphenicol, namely (15.79 ± 1.91) mmm. The high efficacy of flavonoid is understandable since it inhibits and disrupt multiple parts of

E. coli simultaneously as shown in

Figure 1(b). Whereas, chloramphenicol target is only ribosome [

57,

58]

. It inhibits ribosomal assembly [

59]

. Most antibiotics are designed to target certain site of bacteria. As an example, ciprofloxacin target on DNA topoisomerase dan gyrase to prevent DNA replication [

60]

. This finding demonstrates the superiority of flavonoids over the commercial antibiotic chloramphenicol.

Finally, E. coli showed relatively weak resistance to chloramphenicol starting at 39 hours and increasing slowly until the end of observation at 75 hours. Chloramphenicol-resistant E. coli was also discovered by other researchers [61]. In contrast, E. coli did not show the development of resistance at all flavonoid concentrations. This shows the power of flavonoids in preventing E. coli resistance and this is in line with the results of many other researchers [62–64]. The results showed that flavonoids produced very high efficacy and strong power in preventing the development of E. coli resistance and were much better than commercial antibiotics, chloramphenciol as a positive control. These findings highlight the interesting potential of flavonoids as antibacterial agents and will be the main choice as raw materials for future antibacterial drugs to fight multidrug-resistant bacteria. However, further research is needed to reveal which flavonoid subclasses work best on specific bacteria and which subclass combinations are best for infections of multiple types of bacteria simultaneously.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our study successfully validated the traditional decoction Dayak method for extracting flavonoids from UGR. The concentration of flavonoids was accurately determined using visible spectrophotometer and the AlCl3 colorimetry method, yielding a concentration of (31.55 ± 0.29) mg QE/g which was much higher compared to those of 30 Indonesian, 21 Indian, and 93 Chinese medicinal plants. Flavonoid bio-nanoparticles were successfully prepared by a filtration and centrifugation method, with dynamic light scattering revealing particle diameter of 103 nm and PDI of 0.1206 showing relatively low heterogeneity of particles in solution. More works need to be done to uncover different contents of UGR and to observe their antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and anticancer properties.

Antibacterial activity observation through Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method demonstrated that clear zone diameter increases with the increase of flavonoid concentrations. At initial look, flavonoid is inferior compared to chloramphenicol since the data were taken at different concentration units (ppm and %). However, by using a prediction curve 5% flavonoid (equals 50,000 ppm) can produce 2131.2 mm clear zone diameter, which is equivalent to 134.9 times that of produced by 5% chloramphenicol (15.79 mm). This comparison clearly shows the superiority of flavonoid over chloramphenicol making it a splendid candidate for future antibacterial agent. The high efficacy opens opportunity to apply it on many different bacteria to reveal antibacterial spectrum of flavonoid.

E. coli showed weak resistance to chloramphenicol starting at 39 h. In contrast, E. coli did not exhibit resistance to flavonoids up to the last measurement at 75 h. This means that flavonoid poses a strong power to combat bacterial resistance. The strong power to combat bacterial resistance opens opportunity to beat multi-drug resistance bacteria which has been a challenge for decades. All these findings promise a big hope to win the fight against strong and multi-resistant bacteria, making it a compelling candidate for future antibacterial agent.

Supplementary Materials

Merged supplementary data uploaded during manuscript submission.

Author Contributions

SS: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis; AA: methodology and formal analysis; HK: Project administrator and supervision; WSBD: methodology and resources; ESAL: data curation, investigation, validation; DG: data curation, validation, visualization

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data were submitted to MDPI and can be accessed through MDPI

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Agustarini, R.; Heryati, Y.; Adalina, Y. The effort to cultivate natural dyes (Indigofera Sp.) in Timor Region, NTT. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 819, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, T. Implementation of Research and Development Based on Patent Natural Ingredients and Potential Utilization of Tradition Medicine. The Asian Journal of Technology Management 2016, 9, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Santika N K A, Efendi F, Rachmawati P D, Has E M M ah, Kusnanto K and Astutik E. Determinants of diarrhea among children under two years old in Indonesia. Child Youth Serv Rev 2020, 111, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hafifah, D.K.; Suparno, S. Effect of Red Bajakah Tampala Flavonoid Concentration as Antibacterial on Bacillus subtilis. Jurnal Ilmiah Sains 2023, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górniak, I.; Bartoszewski, R.; Króliczewski, J. Comprehensive review of antimicrobial activities of plant flavonoids. Phytochemistry Reviews 2019, 18, 241–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putranta, H.; Permatasari, A.K.; Sukma, T.A.; Suparno Dwandaru WS, B. The effect of pH, electrical conductivity, and nitrogen (N) in the soil at Yogyakarta special region on tomato plant growth. TEM Journal 2019, 8, 860–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thebti, A.; Meddeb, A.; Ben Salem, I.; Bakary, C.; Ayari, S.; Rezgui, F.; Essafi-Benkhadir, K.; Boudabous, A.; Ouzari, H.I. Antimicrobial Activities and Mode of Flavonoid Actions. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsudin, N.F.; Ahmed, Q.U.; Mahmood, S.; Shah SA, A.; Khatib, A.; Mukhtar, S.; Alsharif, M.A.; Parveen, H.; Zakaria, Z.A. Antibacterial Effects of Flavonoids and Their Structure-Activity Relationship Study: A Comparative Interpretation. Molecules 2022, 27, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, F.; Khameneh, B.; Iranshahi, M.; Iranshahy, M. Antibacterial activity of flavonoids and their structure–activity relationship: An update review. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 33, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Deng, J.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, Z. The Antibacterial Activity of Natural-derived Flavonoids. Curr Top Med Chem 2022, 22, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, P.D.; Gama, G.S.; Megiati, H.M.; Madrid RR, M.; Garcia BB, M.; Han, S.W.; Itri, R.; Mertins, O. Flavonoid-Labeled Biopolymer in the Structure of Lipid Membranes to Improve the Applicability of Antioxidant Nanovesicles. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, W.; Tang, F.; Chen, X.; Ren, L. Antibacterial Activities of Flavonoids: Structure-Activity Relationship and Mechanism. Curr Med Chem 2014, 22, 132–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waditzer, M.; Bucar, F. Flavonoids as inhibitors of bacterial efflux pumps. Molecules 2021, 26, 6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Hou, T.; Xu, F.; Luo, F.; Zhou, H.; Liu, F.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Guo, Z.; Liang, X. Discovery of Flavonoids as Novel Inhibitors of ATP Citrate Lyase: Structure–Activity Relationship and Inhibition Profiles. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, L.; Bornstein, M.M.; Shyp, V. Inhibition of biofilm formation and virulence factors of cariogenic oral pathogen Streptococcus mutans by natural flavonoid phloretin. J Oral Microbiol 2023, 15, 2230711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of flavonoids from Chimonanthus salicifolius S. Y. Hu. and its transcriptome analysis against Staphylococcus aureus. Front Microbiol 2023, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagousop, C.N.; Tamokou JD, D.; Ekom, S.E.; Ngnokam, D.; Voutquenne-Nazabadioko, L. Antimicrobial activities of flavonoid glycosides from Graptophyllum grandulosum and their mechanism of antibacterial action. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018, 18, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Wu, Q.; Luan, S.; Yin, Z.; He, C.; Yin, L.; Zou, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Li, L.; Song, X.; He, M.; Lv, C.; Zhang, W. A comprehensive review of topoisomerase inhibitors as anticancer agents in the past decade. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 171, 129–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Tian, W.; Cui, X.; Tu, P.; Li, J.; Shi, S.; Liu, X. Biosynthesis Investigations of Terpenoid, Alkaloid, and Flavonoid Antimicrobial Agents Derived from Medicinal Plants. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravera, S.; Tancreda, G.; Vezzulli, L.; Schito, A.M.; Panfoli, I. Cirsiliol and Quercetin Inhibit ATP Synthesis and Decrease the Energy Balance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE) Strains Isolated from Patients. Molecules 2023, 28, 6183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.; Jha, P.; Chopra, M.; Chaudhry, U.; Saluja, D. Screening of natural compounds that targets glutamate racemase of Mycobacterium tuberculosis reveals the anti-tubercular potential of flavonoids. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed MY, I.; Habib, I. Pathogenic E. coli in the Food Chain across the Arab Countries: A Descriptive Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista, R.; Saraiva, M.; Lopes, T.; Silveira, L.; Coelho, A.; Furtado, R.; Castro, R.; Correia, C.B.; Rodrigues, D.; Henriques, P.; Lóio, S.; Soeiro, V.; da Costa, P.M.; Oleastro, M.; Pista, A. Genotypic and Phenotypic Characterization of Pathogenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Campylobacter spp., in Free-Living Birds in Mainland Portugal. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvishi, S.; Girault, H.H. Revealing the Effects of Three Different Antimicrobial Agents on E. coli Biofilms by Using Soft-Probe Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy. Applied Nano 2023, 4, 260–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.F.; Wang, J.X.; Le, Y. Double-layer hybrid nanofiber membranes by electrospinning with sustained antibacterial activity for wound healing. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2023, 127, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag MA, S.; Khan MS, R.; Sami MD, H.; Begum, F.; Islam, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Rahman, M.T.; Hassan, J. Virulence determinants and antimicrobial resistance of E. coli isolated from bovine clinical mastitis in some selected dairy farms of Bangladesh. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021, 28, 6317–6323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ding, Y.; Yao, K.; Gao, W.; Wang, Y. Antimicrobial Resistance Analysis of Clinical Escherichia coli Isolates in Neonatal Ward. Front Pediatr 2021, 9, 670470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadoon R J, Jalal-ud-din M and Khan S A. E. coli resistance to ciprofloxacin and common associated factors. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons Pakistan 2015, 25, 824–827. [Google Scholar]

- Elabbasy, M.T.; Hussein, M.A.; Algahtani, F.D.; Abd El-Rahman, G.I.; Morshdy, A.E.; Elkafrawy, I.A.; Adeboye AA MALDI-TOFMS based typing for rapid screening of multiple antibiotic resistance, E. Coli and virulent non-O157 shiga toxin-producing E. coli isolated from the slaughterhouse settings and beef carcasses. Foods 2021, 10, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.S.; Hassan, M.M.; Ahaduzzaman, M.; Nath, C.; Dutta, P.; Khanom, H.; Khan, S.A.; Pasha, M.R.; Islam, A.; Magalhaes, R.S.; Cobbold, R. Molecular Detection of Tetracycline-Resistant Genes in Multi-Drug-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Broiler Meat in Bangladesh. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozhin, A.; Batasheva, S.; Kruychkova, M.; Cherednichenko, Y.; Rozhina, E.; Fakhrullin, R. Biogenic silver nanoparticles: Synthesis and application as antibacterial and antifungal agents. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palupi SK, I.; Suparno, S. Ionic Silver Nanoparticles (Ag+) Sebagai Bahan Antibiotik Alternatif Untuk Salmonella Typhymurium. Indonesian Journal of Applied Physics 2020, 10, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, Z.; Aliannezhadi, M.; Ghominejad, M.; Tehrani, F.S. High specific surface area γ-Al2O3 nanoparticles synthesized by facile and low-cost co-precipitation method. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, L.; Yang, D.; Kanaev, A. Dynamic Light Scattering: A Powerful Tool for In Situ Nanoparticle Sizing. Colloids and Interfaces 2023, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suparno, S.; Ayu Lestari, E.S.; Grace, D. Antibacterial activity of Bajakah Kalalawit phenolic against Staphylococcus aureus and possible use of phenolic nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 19734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preethamol, S.N.; Thoppil, J.E. Phenolic content, flavonoid content and antioxidant potential of whole plant extract of ophiorrhiza pectinata arn. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020, 82, 712–718. [Google Scholar]

- Sapiun, Z.; Pangalo, P.; Imran, A.K.; Wicita, P.S.; Daud RP, A. Determination of total flavonoid levels of ethanol extract Sesewanua leaf (Clerodendrum fragrans Wild) with maceration method using UV-vis spectrofotometry. Pharmacognosy Journal 2020, 12, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, L.; Permana, B.D.; Kristiningrum, N. Determination of total flavonoid content in medicinal plant leaves powder using infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics. Indonesian Journal of Chemistry 2020, 20, 1044–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, C.T.; Balachandran, I. Total phenolics and total flavonoids in selected indian medicinal plants. Indian J Pharm Sci 2012, 74, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pare, P.W.; Zhang, J.; Kang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, K.; Xing, H. Antioxidant capacity connection with phenolic and flavonoid content in Chinese medicinal herbs. Records of Natural Products 2018, 12, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamadani, Y.; Oudah, A. Study of the Bacterial Sensitivity to different Antibiotics which are isolated from patients with UTI using Kirby-Bauer Method. Journal of Biomedicine and Biochemistry 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, N. The influence of decoction and infusion methods and times on antioxidant activity, caffeine content and phenolic compounds of coffee brews. European Food Research and Technology 2022, 248, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winda, F.R.; Suparno, S.; Prasetyo, Z.K. Antibacterial Activity of Cinnamomum burmannii Extract Against Escherichia coli. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 2023, 9, 9162–9170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabaidur, S.M.; Obbed, M.S.; Alothman, Z.A.; Alfaris, N.A.; Badjah-Hadj-ahmed, A.Y.; Siddiqui, M.R.; Altamimi, J.Z.; Aldayel, T.S. Total phenolic acids and flavonoid contents determination in yemeni honey of various floral sources: Folin-ciocalteu and spectrophotometric approach. Food Science and Technology (Brazil) 2020, 40, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kol, R.; Carrieri, E.; Gusev, S.; Verswyvel, M.; Niessner, N.; Lemonidou, A.; Achilias, D.S.; De Meester, S. Removal of undissolved substances in the dissolution-based recycling of polystyrene waste by applying filtration and centrifugation. Sep Purif Technol 2023, 325, 124682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingale, T.; Duse, P.; Ogale, S. Antibacterial and antifungal approaches of Ficus racemosa. Pharmacognosy Journal 2019, 11, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohmatin, I.A.; Suparno, S. Effect of Cocoa Bean Extract Concentration on the Diameter of the Clear Zone Preparing Streptococcus Mutans Bacteria. Jurnal Penelitian Pendidikan IPA 2023, 9, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barido, F.H.; Jang, A.; Pak, J.I.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.K. Combined effects of processing method and black garlic extract on quality characteristics, antioxidative, and fatty acid profile of chicken breast. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalder, R.H.; Knott, T.; Rushton, J.O.; Nikolic-Pollard, D. Changes in antimicrobial resistance patterns of ocular surface bacteria isolated from horses in the UK: An eight-year surveillance study (2012-2019). Vet Ophthalmol 2020, 23, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noga, M.; Milan, J.; Frydrych, A.; Jurowski, K. Toxicological Aspects, Safety Assessment, and Green Toxicology of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)—Critical Review: State of the Art. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoseini, B.; Jaafari, M.R.; Golabpour, A.; Momtazi-Borojeni, A.A.; Karimi, M.; Eslami, S. Application of ensemble machine learning approach to assess the factors affecting size and polydispersity index of liposomal nanoparticles. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 18012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, C.F.; Coimbra JT, S.; Richter, R.; Morais-Cabral, J.H.; Ramos, M.J.; Lehr, C.M.; Fernandes, P.A.; Gameiro, P. Exploring the permeation of fluoroquinolone metalloantibiotics across outer membrane porins by combining molecular dynamics simulations and a porin-mimetic in vitro model. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2022, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Peterson, J.H.; Bernstein, H.D. Reconstitution of bam complex-mediated assembly of a trimeric porin into proteoliposomes. mBio 2021, 12, e0169621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Nayeem MM, H.; Sobur, M.A.; Ievy, S.; Islam, M.A.; Rahman, S.; Kafi, M.A.; Ashour, H.M.; Rahman, M.T. Virulence determinants and multidrug resistance of escherichia coli isolated from migratory birds. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Brück, W.M.; Rossen JW, A. Virulence factors of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli: A review. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Wang, J.; Han, B.; Tao, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X. Bacterial resistance to antibacterial agents: Mechanisms, control strategies, and implications for global health. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 860, 160461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Barra, J.T.; Fung, D.K.; Wang, J.D. Bacillus subtilis produces (p)ppGpp in response to the bacteriostatic antibiotic chloramphenicol to prevent its potential bactericidal effect. mLife 2022, 1, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhill, A.E.; Brewer, M.T.; Carlson, S.A. Adverse effects of antimicrobials via predictable or idiosyncratic inhibition of host mitochondrial components. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012, 56, 4046–4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siibak, T.; Peil, L.; Xiong, L.; Mankin, A.; Remme, J.; Tenson, T. Erythromycin- and chloramphenicol-induced ribosomal assembly defects are secondary effects of protein synthesis inhibition. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009, 53, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olina, A.; Agapov, A.; Yudin, D.; Sutormin, D.; Galivondzhyan, A.; Kuzmenko, A.; Severinov, K.; Aravin, A.A.; Kulbachinskiy, A. Bacterial Argonaute Proteins Aid Cell Division in the Presence of Topoisomerase Inhibitors in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).