Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Multiple Sclerosis and Steroids

1.1.1. Cortisol

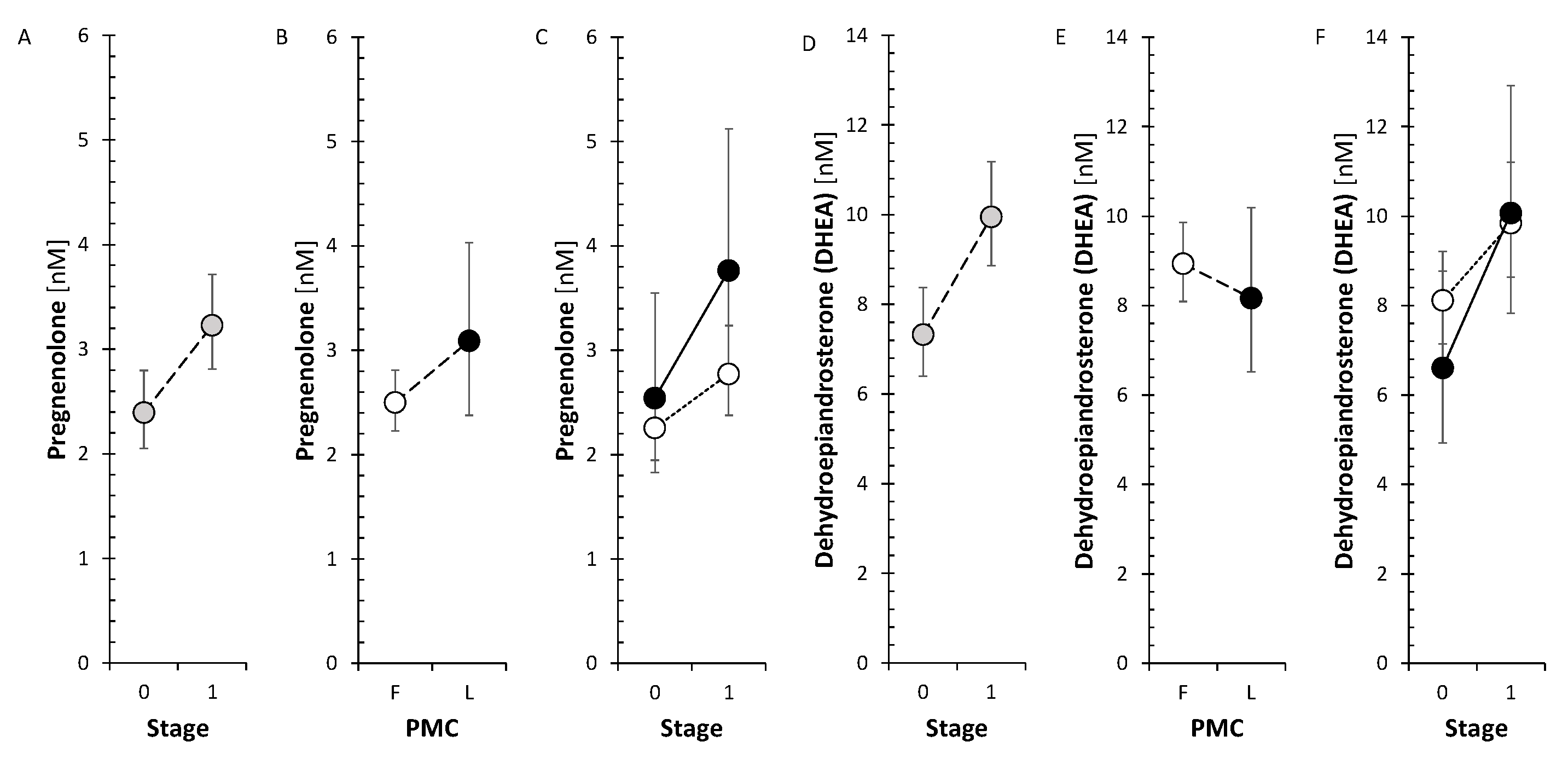

1.1.2. Δ5 Steroids

1.1.3. Active Androgens

1.1.4. Estrogens

1.1.5. Progesterone and Its Metabolites

1.2. Effect of Anti-MS Drugs on Circulating Steroids and Steroid Molar Ratios (SMRs)

1.2.1. Glatiramer Acetate (GA)

1.2.2. Interferons β1a (IFN-β1a)

1.2.3. Inhibitors of the Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor (S1PRI)

1.2.4. Ofatumumab (Kesimpta) and Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus)

2. Results

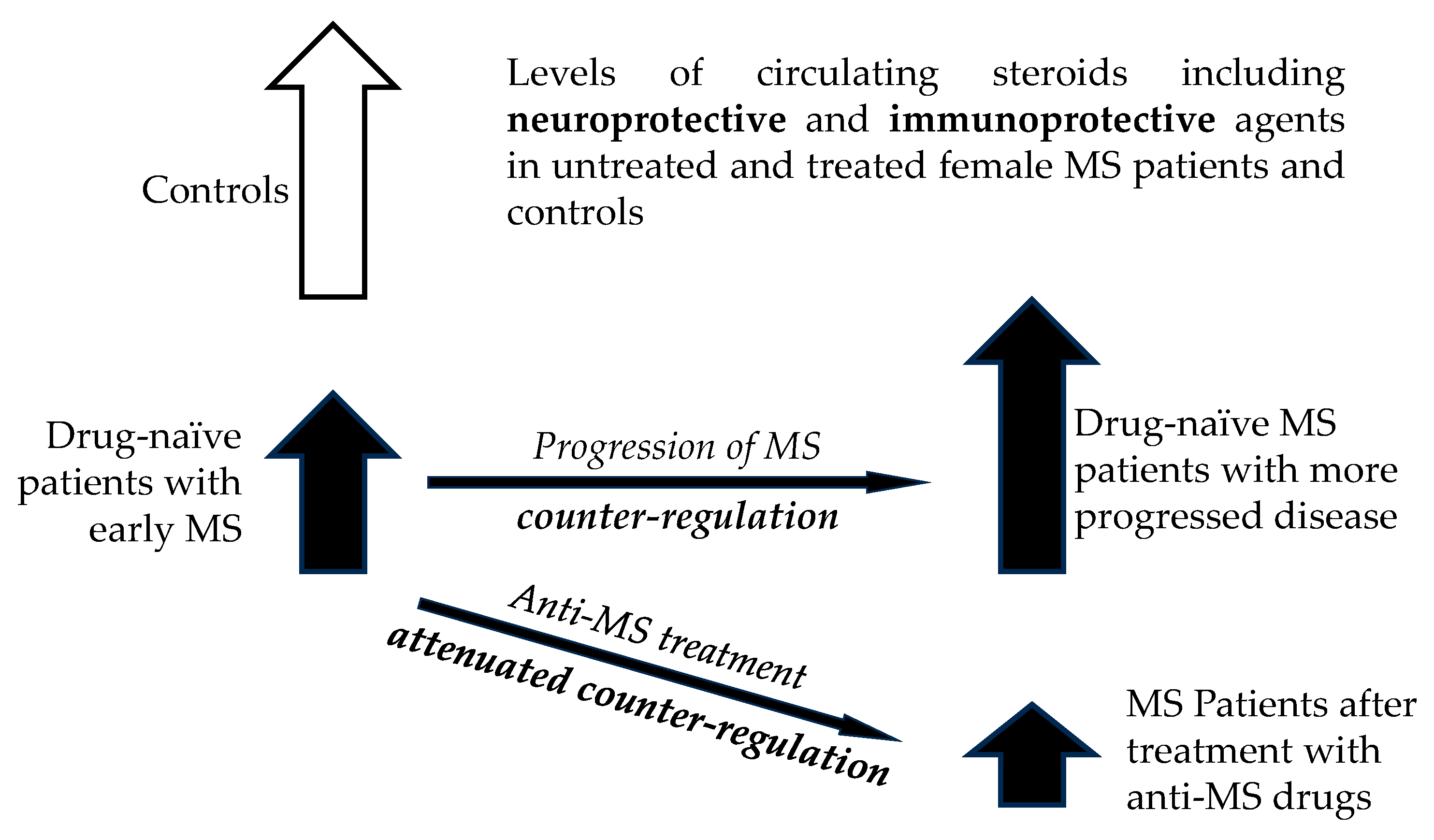

2.1. Pooled Trends of Changes in Circulating Steroid Levels and Steroid Molar Ratios (SMR) After Treatment with Anti-MS Drugs

2.1.1. Corticoids (C21 Δ4 Steroids) and 11β-Hydroxy-Androstanes (C19 Δ4 and 5α/β Steroids)

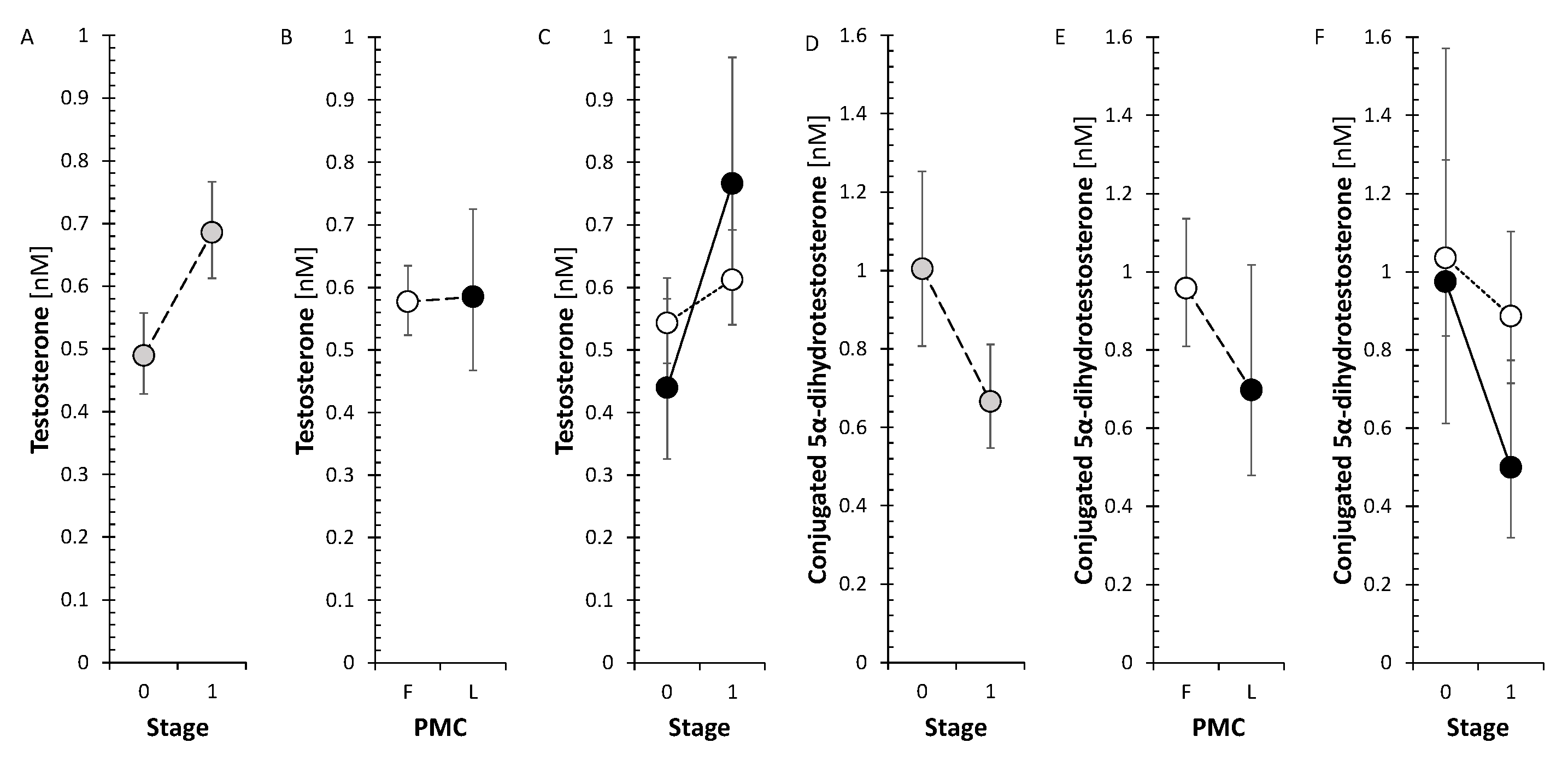

2.1.3. Active Androgens and Estrogens

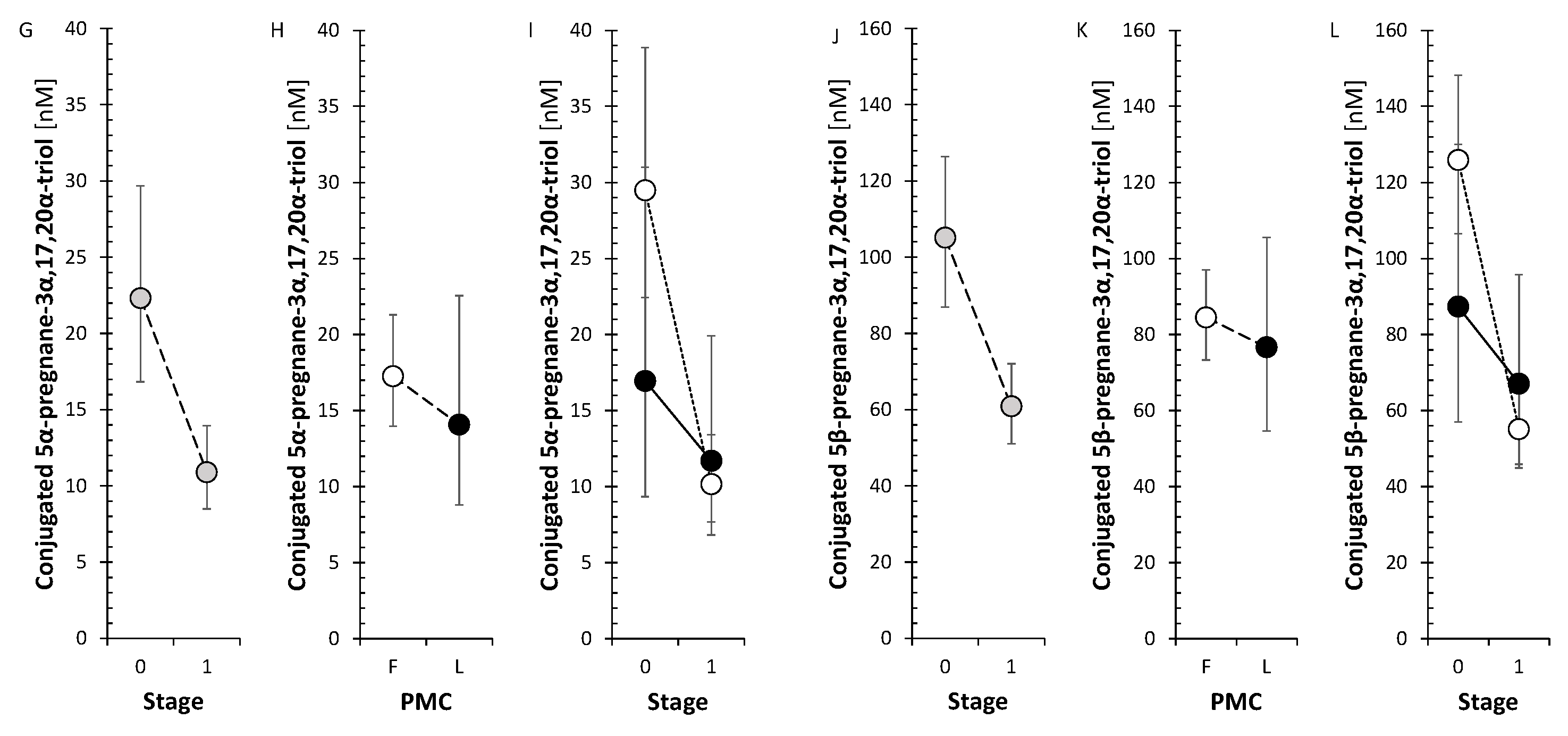

2.1.4. Progesterone and Its Metabolites

2.1.5. C17-Hydroxylase, C17-20-Lyase (CYP17A1) and 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases (HSD3Bs)

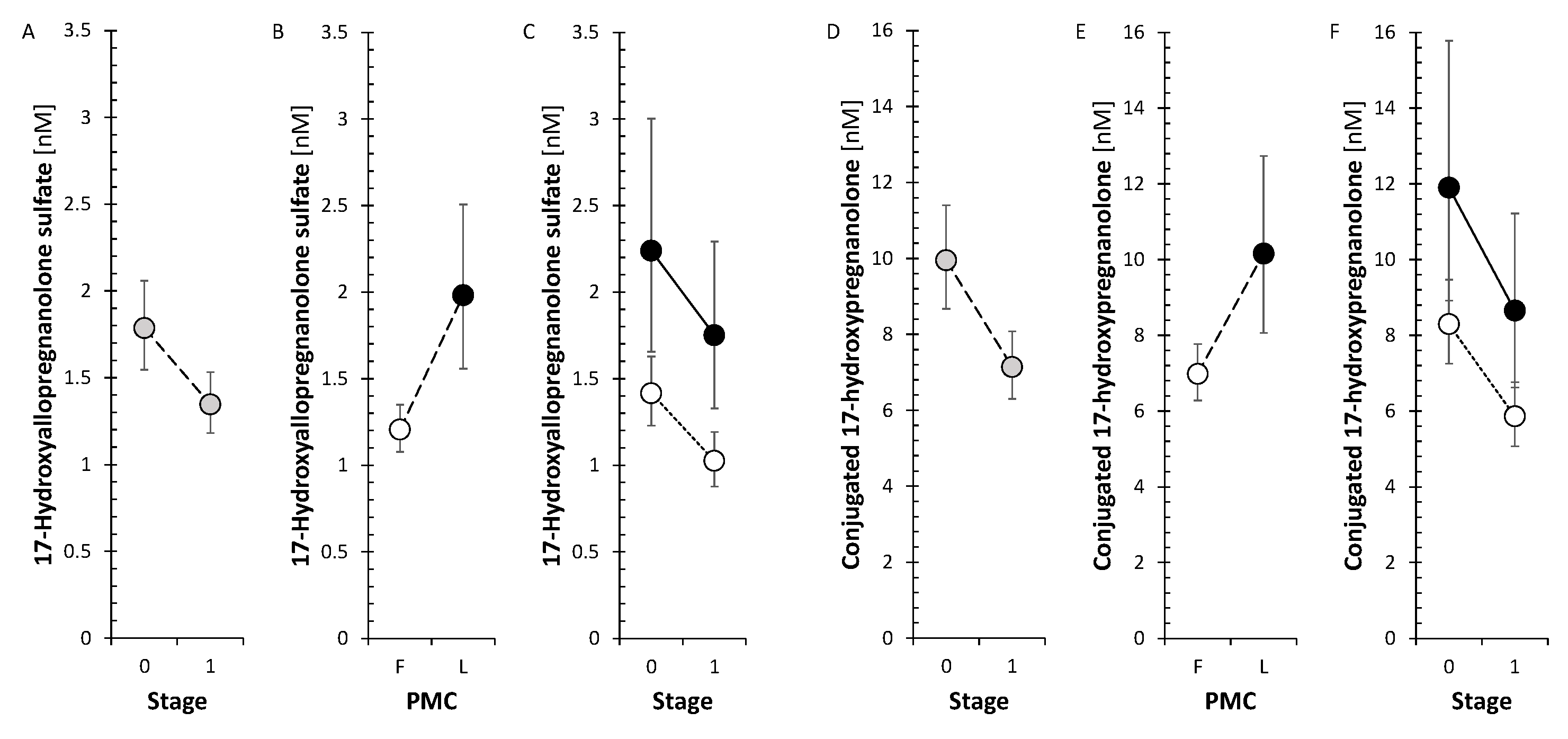

2.1.6. A Balance Between Steroid Sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) and Steroid Sulfatase (STS)

2.1.7. 11β-Hydroxylase (CYP11B1) and Type 1 11β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase (HSD11B1)

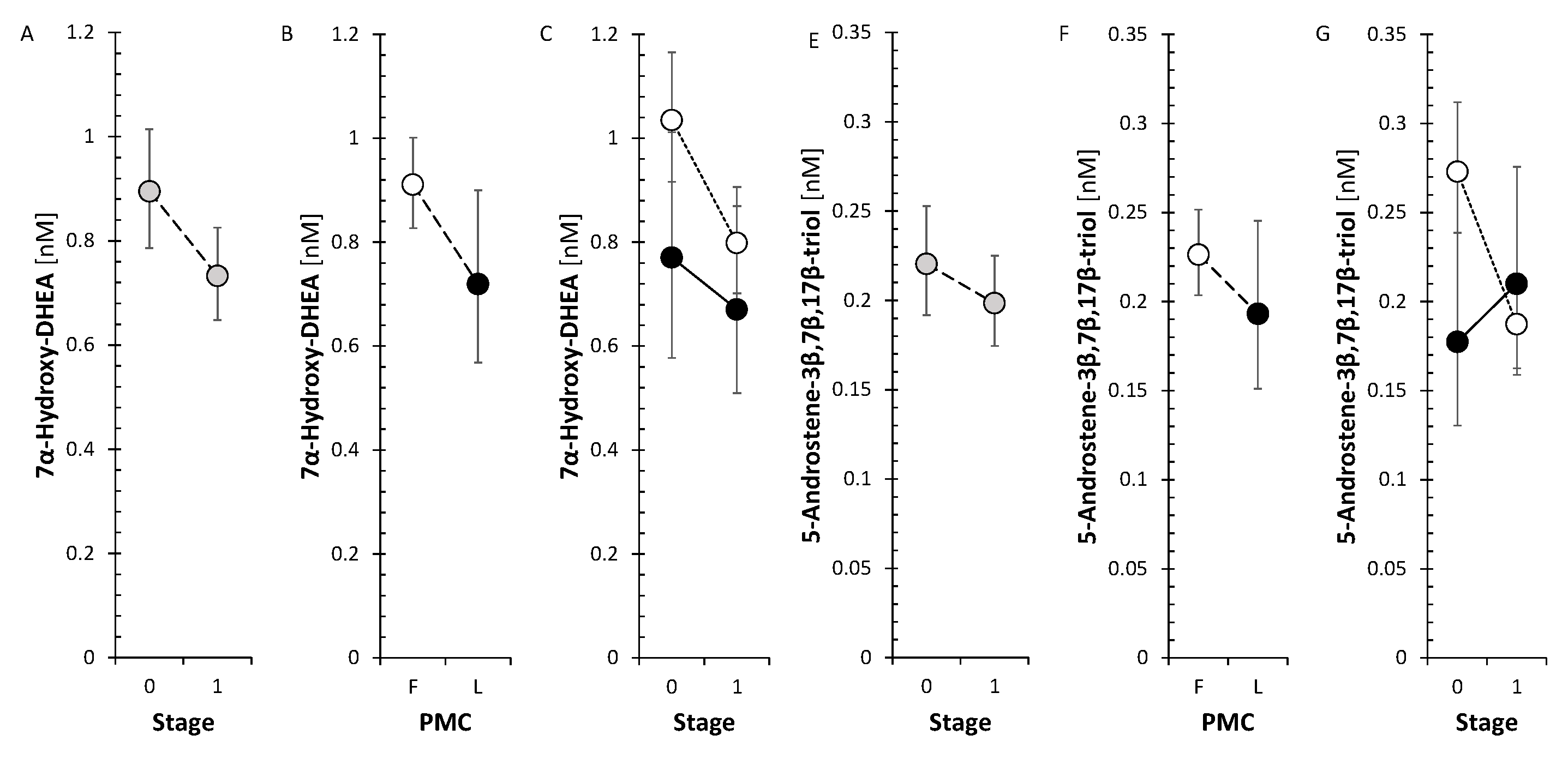

2.1.8. 7α-, 7β-, and 16α-Hydroxylating Enzymes (CYP7B1, CYP3A4, CYP3A7)

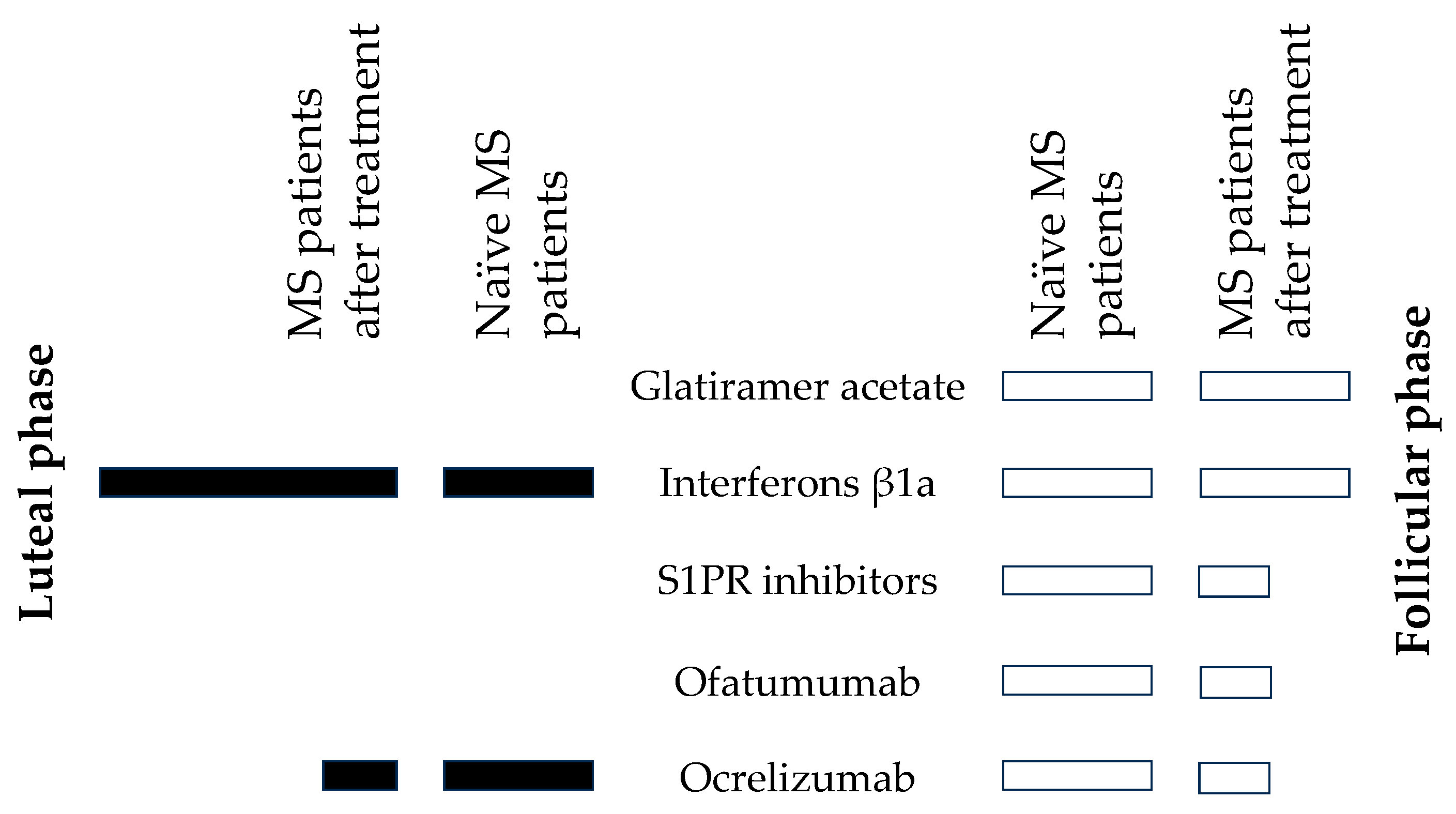

2.2. Effect of Anti-MS Drugs on Circulating Steroids and Steroid Molar Ratios (SMRs)

2.2.1. Glatiramer Acetate (GA) in the Follicular Menstrual Phase

2.2.2. Interferons β1a (IFN-β1a)

2.2.3. Inhibitors of the Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor (S1PRI) in the Follicular Menstrual Phase

2.2.4. Ofatumumab (Kesimpta) in the Follicular Menstrual Phase

2.2.5. Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus)

3. Discussion

3.1. Changes of Steroid Levels and Steroid Molar Ratios (SMRs) in MS Patients After Treatment with Anti-MS Drugs

3.1.1. Corticoids (C21 Δ4 Steroids) and 11β-Hydroxy-Androgens (C19 Δ4 and 5α/β Steroids), 11β-Hydroxylase (CYP11B1) and Type 1 11β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase (HSD11B1)

3.1.3. Active Androgens and Estrogens

3.1.4. Progesterone and Its 5αβ-Reduced Metabolites

3.1.5. C17-Hydroxylase, C17-20-Lyase (CYP17A1), Hydroxylase and 3β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenases (HSD3Bs)

3.1.6. A Balance Between Steroid Sulfotransferase (SULT2A1) and Steroid Sulfatase (STS)

4. Potential Clinical Implications of the Findings

5. Future Directions

6. Limitations of the Study

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Subjects

7.2. Steroid Analyses

7.3. Statistical Analyses

- Transformation of the original data to obtain the values with symmetric distribution and constant variance

- Checking the data homogeneity in predictors using Hotelling’s statistics and the eventual elimination of non-homogeneities

- Testing the relevance of predictors using variable importance statistics and the elimination of irrelevant predictors

- Calculating component loadings for individual variables to evaluate their correlations with the predictive component

- Calculating regression coefficients for the ordinary multiple regression model (OMR) to evaluate the mutual independence of predictors after comparison with the corresponding component loadings from the OPLS model

- Calculating predicted values of the logarithm of the ratio of the probability of pathology presence to the probability of pathology absence (LLR)

- Calculating the probability of the pathology presence for individual subjects

- Calculating the sensitivity and specificity of the prediction

8. Conclusions

- 1)

- A comprehensive steroidomic analysis of steroidomic changes after treatment with anti-MS drugs was performed. The study participants were MS newly diagnosed female patients who met the 2017 revised McDonald criteria and had not yet been treated.

- 2)

- Almost all steroids have been studied for the first time in terms of the effects of treatment with anti-MS drugs.

- 3)

- MS patients showed a general tendency towards a decrease in steroid levels in follicular menstrual phase due to treatment with anti-MS drugs but absence of this trend in luteal phase, which could be interpreted as a weakening of counterregulatory mechanisms associated with adrenal steroids, which may mitigate adverse effects of MS. Another explanation could be the anti-steroidogenic effect of key anti-MS drugs on adrenal steroidogenesis.

- 4)

- Decreased 17-hydroxy-pregnane levels after treatment with anti-MS drugs in FP indicate a decreasing trend of CYP17A1 activity, suggesting a weakening of one of the steps of the cortisol pathway and, together with the analysis for individual anti-MS drugs, a strengthening of the step towards immunomodulatory adrenal androgens. These results also suggest that among the anti-MS drugs, the monoclonal anti-CD20, S1PRI and IFNβ-1a antibodies may be responsible for the above findings. These findings could have implications for the synthesis and metabolism of bioactive steroids, whether they are cortisol, active androgens and estrogens, or neuroactive and neuroprotective substances acting through modulation of ionotropic receptors.

- 5)

-

A significant trend to decreased ratios of conjugated steroids to their unconjugated counterparts was observed indicating either suppression of SULT2A1 activity and/or stimulation of STS activity by anti-MS drugs, from which GA and ofatumumab in FP, and ocrelizumab in both menstrual phases contributed this pooled trend. Moreover, our current data show a significant trend towards a decrease in conjugated steroids level in FP after anti-MS drug therapy. The above data may be relevant to the regulation of neuronal excitability because:

- a. Unconjugated steroids act through binding to nuclear receptors while their sulfates are inactive.

- b. Sulfation of unconjugated neuroinhibitory GABAergic steroids leads to their inactivation or even to the formation of their antagonists.

- c. Some sulfated steroids can be positive or negative modulators of excitatory glutamate receptors, whereas all their unconjugated analogues are inactive in this context.

- d. Sulfated androgens may serve as a reservoir of substrates for the synthesis of bioactive androgens acting as sex hormones, neuroprotective and immunomodulatory agents

- 6)

- A borderline downward trend was observed in CYP11B1 after anti-MS therapy, which may downregulate cortisol synthesis in the last metabolic step.

- 1)

- GA treatment in FP also shifted the balance from reductive AKR1C1 to oxidative HSD17B2 which may contribute to the inflammatory milieu.

- 2)

-

In addition to affecting CYP17A1 activities, IFN-β1a also showed:

- a. A significant trend toward increased steroidogenesis in LP, which is predominantly controlled by ovarian activity but no effect in FP, which is predominantly controlled by adrenal activity.

- b. A significant trend toward increased steroid levels after IFN-β1a in LP included significant increases in some important bioactive steroids such as the neuroprotective pregnenolone and steroid hormones such as testosterone, 5α-DHT, and cortisol. These observations indicate a beneficial effect of IFN-β1a treatment in terms of MS severity.

- c. A significant trend to higher SMRs that may reflect AKR1D1 activity which could be of importance in terms of the synthesis of neuroinhibitory 5β-pregnanes.

- 3)

- S1PRI (in addition to affecting a general trend in steroid levels and SMRs that may reflect CYP17A1 activities) also showed a trend to lower SMRs that may reflect SRD5A activity.

- 4)

-

Anti-CD20 mAb (ofatumumab, ocrelizumab) treatment (in addition to affecting a general trend in steroid levels and SMRs that may reflect CYP17A1 activities and shift in the balance conjugated/unconjugated steroid) showed:

- a. A borderline trend to decrease for the SMRs that may reflect the activities of HSD3Bs (ofatumumab).

- b. A significant (ofatumumab) or borderline (ocrelizumab in LP) trend, or at least indication of the trend (ocrelizumab in LP) to lower values of SMRs that may reflect activities of CYP7B1, CYP3A4 and CYP3A7 enzymes catalyzing the synthesis of immunomodulatory 7α/β and 16α-hydroxy-androgens. Moreover, there was a pooled borderline downward trend in their levels after therapy with anti-MS drugs. These data are relevant concerning the immunomodulatory effect of these steroids as they affect Th1/Th2 balance and thus may influence the severity of MS.

- c. An indication of the trend to decrease in SMRs that may reflect the activity of reductive AKR1C3 (primarily converting 17-oxo androstanes and estrogens to their 17 β-hydroxy counterparts) to oxidative HSD17B2 activity acting in the opposite direction for ocrelizumab in the LP and even the significant trend for ofatumumab.

- d. A significant trend to lower values of the SMRs that may reflect the activity of AKR1D1 (ocrelizumab in the LP).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ysrraelit, M.C.; Correale, J. Impact of sex hormones on immune function and multiple sclerosis development. Immunology 2019, 156, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparaco, M.; Bonavita, S. The role of sex hormones in women with multiple sclerosis: From puberty to assisted reproductive techniques. Front Neuroendocrinol 2021, 60, 100889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Studd, J.W. A pilot study of the effect upon multiple sclerosis of the menopause, hormone replacement therapy and the menstrual cycle. J R Soc Med 1992, 85, 612–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Makris, N. Multiple sclerosis and reproductive risks in women. Reprod Sci 2008, 15, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, A.C.; Meroni, M.; Cutolo, M. Steroids and Autoimmunity. Front Horm Res 2017, 48, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kamin, H.S.; Kertes, D.A. Cortisol and DHEA in development and psychopathology. Horm Behav 2017, 89, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulska, J.; Juszczyk, G.; Gawronska-Grzywacz, M.; Herbet, M. HPA Axis in the Pathomechanism of Depression and Schizophrenia: New Therapeutic Strategies Based on Its Participation. Brain Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, K.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Keller, J. HPA axis in psychotic major depression and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Cortisol, clinical symptomatology, and cognition. Schizophr Res 2019, 213, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiak, B.; Piotrowski, P.; Chec, M.; Samochowiec, J. Cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders with respect to cognitive performance. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol 2021, 6, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritsner, M.; Maayan, R.; Gibel, A.; Strous, R.D.; Modai, I.; Weizman, A. Elevation of the cortisol/dehydroepiandrosterone ratio in schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2004, 14, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritsner, M.; Gibel, A.; Maayan, R.; Ratner, Y.; Ram, E.; Modai, I.; Weizman, A. State and trait related predictors of serum cortisol to DHEA(S) molar ratios and hormone concentrations in schizophrenia patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007, 17, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kancheva, R.; Hill, M.; Novak, Z.; Chrastina, J.; Kancheva, L.; Starka, L. Neuroactive steroids in periphery and cerebrospinal fluid. Neuroscience 2011, 191, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begemann, M.J.; Dekker, C.F.; van Lunenburg, M.; Sommer, I.E. Estrogen augmentation in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of current evidence. Schizophr Res 2012, 141, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaiser, M.Z.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Begley, D.J.; Abbott, N.J.; Cazacu-Davidescu, M.; Corol, D.I.; Fry, J.P. Uptake and metabolism of sulphated steroids by the blood-brain barrier in the adult male rat. J Neurochem 2017, 142, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, H.; Cao, T.; Zhou, X.; Yao, J.K. Neurosteroids in Schizophrenia: Pathogenic and Therapeutic Implications. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powrie, Y.S.L.; Smith, C. Central intracrine DHEA synthesis in ageing-related neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration: therapeutic potential? J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honcu, P.; Hill, M.; Bicikova, M.; Jandova, D.; Velikova, M.; Kajzar, J.; Kolatorova, L.; Bestak, J.; Macova, L.; Kancheva, R. , et al. Activation of Adrenal Steroidogenesis and an Improvement of Mood Balance in Postmenopausal Females after Spa Treatment Based on Physical Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, E.M.; Odontiadis, J.; Le Melledo, J.M.; Prior, T.I.; Baker, G.B. The relevance of neuroactive steroids in schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety disorders. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2007, 27, 541–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu-The, V. Assessment of steroidogenesis and steroidogenic enzyme functions. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2013, 137, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrie, F. All sex steroids are made intracellularly in peripheral tissues by the mechanisms of intracrinology after menopause. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2015, 145, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorbakhsh, F.; Ellestad, K.K.; Maingat, F.; Warren, K.G.; Han, M.H.; Steinman, L.; Baker, G.B.; Power, C. Impaired neurosteroid synthesis in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2011, 134, 2703–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorbakhsh, F.; Baker, G.B.; Power, C. Allopregnanolone and neuroinflammation: a focus on multiple sclerosis. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassini, V.; Pozzilli, C. Sex hormones, brain damage and clinical course of Multiple Sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2009, 286, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cil, A.P.; Leventoglu, A.; Sonmezer, M.; Soylukoc, R.; Oktay, K. Assessment of ovarian reserve and Doppler characteristics in patients with multiple sclerosis using immunomodulating drugs. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc 2009, 10, 213–219. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, W.J.; Wang, Y. Sterols, Oxysterols, and Accessible Cholesterol: Signalling for Homeostasis, in Immunity and During Development. Front Physiol 2021, 12, 723224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukocheva, O.; Wadham, C.; Gamble, J.; Xia, P. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 transmits estrogens' effects in endothelial cells. Steroids 2015, 104, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucki, N.C.; Li, D.; Sewer, M.B. Sphingosine-1-phosphate rapidly increases cortisol biosynthesis and the expression of genes involved in cholesterol uptake and transport in H295R adrenocortical cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2012, 348, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, A.; Rosales-Torres, A.M.; Medina-Moctezuma, Z.B.; Gonzalez-Aretia, D.; Hernandez-Coronado, C.G. Effects and action mechanism of gonadotropins on ovarian follicular cells: A novel role of Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P). A review. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2024, 357, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siavoshi, F.; Ladakis, D.C.; Muller, A.; Nourbakhsh, B.; Bhargava, P. Ocrelizumab alters the circulating metabolome in people with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2024, 11, 2485–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, K.; Ito, N.; Yadav, S.K.; Suresh, S.; Lin, Y.; Dhib-Jalbut, S. Effect of switching glatiramer acetate formulation from 20 mg daily to 40 mg three times weekly on immune function in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2021, 7, 20552173211032323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dargahi, N.; Katsara, M.; Tselios, T.; Androutsou, M.E.; de Courten, M.; Matsoukas, J.; Apostolopoulos, V. Multiple Sclerosis: Immunopathology and Treatment Update. Brain Sci 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murdoch, D.; Lyseng-Williamson, K.A. Spotlight on subcutaneous recombinant interferon-beta-1a (Rebif) in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. BioDrugs 2005, 19, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannoni, G.; Munschauer, F.E., 3rd; Deisenhammer, F. Neutralising antibodies to interferon beta during the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002, 73, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Bar-Or, A.; Wiendl, H.; Paling, D.; Williams, M.; Gold, R.; Chan, A.; Milo, R.; Das Gupta, A. , et al. The Development of Ofatumumab, a Fully Human Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody for Practical Use in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis Treatment. Neurol Ther 2023, 12, 1491–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinley, M.P.; Moss, B.P.; Cohen, J.A. Safety of monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2017, 16, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, Y.N. Ocrelizumab: A Review in Multiple Sclerosis. Drugs 2022, 82, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kancheva, R.; Hill, M.; Velikova, M.; Kancheva, L.; Vcelak, J.; Ampapa, R.; Zido, M.; Stetkarova, I.; Libertinova, J.; Vosatkova, M. , et al. Altered Steroidome in Women with Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, F.; Martel, C.; Belanger, A.; Pelletier, G. Androgens in women are essentially made from DHEA in each peripheral tissue according to intracrinology. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017, 168, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angeli, A.; Masera, R.G.; Sartori, M.L.; Fortunati, N.; Racca, S.; Dovio, A.; Staurenghi, A.; Frairia, R. Modulation by cytokines of glucocorticoid action. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999, 876, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Kloet, E.R.; Joels, M.; Holsboer, F. Stress and the brain: from adaptation to disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005, 6, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hildebrandt, H.; Stachowiak, R.; Heber, I.; Schlake, H.P.; Eling, P. Relation between cognitive fatigue and circadian or stress related cortisol levels in MS patients. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020, 45, 102440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slominski, R.M.; Tuckey, R.C.; Manna, P.R.; Jetten, A.M.; Postlethwaite, A.; Raman, C.; Slominski, A.T. Extra-adrenal glucocorticoid biosynthesis: implications for autoimmune and inflammatory disorders. Genes Immun 2020, 21, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucha, L.; Fuermaier, A.B.; Koerts, J.; Buggenthin, R.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Weisbrod, M.; Thome, J.; Lange, K.W.; Tucha, O. Sustained attention in adult ADHD: time-on-task effects of various measures of attention. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2017, 124, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedhara, K.; Hyde, J.; Gilchrist, I.D.; Tytherleigh, M.; Plummer, S. Acute stress, memory, attention and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2000, 25, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G.M.; Soares, N.M.; Souza, A.R.; Becker, J.; Finkelsztejn, A.; Almeida, R.M.M. Basal cortisol levels and the relationship with clinical symptoms in multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2018, 76, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidbrink, C.; Hausler, S.F.; Buttmann, M.; Ossadnik, M.; Strik, H.M.; Keller, A.; Buck, D.; Verbraak, E.; van Meurs, M.; Krockenberger, M. , et al. Reduced cortisol levels in cerebrospinal fluid and differential distribution of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases in multiple sclerosis: implications for lesion pathogenesis. Brain Behav Immun 2010, 24, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughipour, A.; Norbakhsh, V.; Najafabadi, S.H.; Meamar, R. Evaluating sex hormone levels in reproductive age women with multiple sclerosis and their relationship with disease severity. J Res Med Sci 2012, 17, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wei, T.; Lightman, S.L. The neuroendocrine axis in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain 1997, 120 ( Pt 6) Pt 6, 1067–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidovic, A.; Karapetyan, K.; Serdarevic, F.; Choi, S.H.; Eisenlohr-Moul, T.; Pinna, G. Higher Circulating Cortisol in the Follicular vs. Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle: A Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx, C.E.; Keefe, R.S.; Buchanan, R.W.; Hamer, R.M.; Kilts, J.D.; Bradford, D.W.; Strauss, J.L.; Naylor, J.C.; Payne, V.M.; Lieberman, J.A. , et al. Proof-of-concept trial with the neurosteroid pregnenolone targeting cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 34, 1885–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuszewska, A.; Kowalski, K.; Jawien, P.; Tomkalski, T.; Gawel-Dabrowska, D.; Merwid-Lad, A.; Szelag, E.; Blaszczak, K.; Wiatrak, B.; Danielewski, M. , et al. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis in Men with Schizophrenia. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R.; Jorgensen, T.N. Androgen-Induced Immunosuppression. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomassini, V.; Onesti, E.; Mainero, C.; Giugni, E.; Paolillo, A.; Salvetti, M.; Nicoletti, F.; Pozzilli, C. Sex hormones modulate brain damage in multiple sclerosis: MRI evidence. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005, 76, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Estrada, J.; Del Rio, J.A.; Luquin, S.; Soriano, E.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Gonadal hormones down-regulate reactive gliosis and astrocyte proliferation after a penetrating brain injury. Brain Res 1993, 628, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovolenta, P.; Wandosell, F.; Nieto-Sampedro, M. CNS glial scar tissue: a source of molecules which inhibit central neurite outgrowth. Prog Brain Res 1992, 94, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Burda, J.E.; Sofroniew, M.V. Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to CNS damage and disease. Neuron 2014, 81, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, M.; Kim, S.; Voskuhl, R.R. Testosterone therapy ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and induces a T helper 2 bias in the autoantigen-specific T lymphocyte response. J Immunol 1997, 159, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, A.; Di Giorgi Gerevini, V.; Castiglione, M.; Marinelli, F.; Tomassini, V.; Pozzilli, C.; Caricasole, A.; Bruno, V.; Caciagli, F.; Moretti, A. , et al. Testosterone amplifies excitotoxic damage of cultured oligodendrocytes. J Neurochem 2004, 88, 1179–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoumari, A.M.; Ibanez, C.; El-Etr, M.; Leclerc, P.; Eychenne, B.; O'Malley, B.W.; Baulieu, E.E.; Schumacher, M. Progesterone and its metabolites increase myelin basic protein expression in organotypic slice cultures of rat cerebellum. J Neurochem 2003, 86, 848–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodhankar, S.; Wang, C.; Vandenbark, A.A.; Offner, H. Estrogen-induced protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is abrogated in the absence of B cells. Eur J Immunol 2011, 41, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M. K.; Guryev, O. L.; Auchus, R. J. , 5alpha-reduced C21 steroids are substrates for human cytochrome P450c17. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003, 418, (2), 151–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, J.; Nakamura, Y.; Wang, T.; Merchen, T.D.; Sasano, H.; Rainey, W.E. Transcriptome profiling reveals differentially expressed transcripts between the human adrenal zona fasciculata and zona reticularis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, E518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park-Chung, M.; Wu, F.S.; Purdy, R.H.; Malayev, A.A.; Gibbs, T.T.; Farb, D.H. Distinct sites for inverse modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by sulfated steroids. Mol Pharmacol 1997, 52, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Chung, M.; Malayev, A.; Purdy, R.H.; Gibbs, T.T.; Farb, D.H. Sulfated and unsulfated steroids modulate gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor function through distinct sites. Brain Res 1999, 830, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smejkalova, T.; Korinek, M.; Krusek, J.; Hrcka Krausova, B.; Candelas Serra, M.; Hajdukovic, D.; Kudova, E.; Chodounska, H.; Vyklicky, L. Endogenous neurosteroids pregnanolone and pregnanolone sulfate potentiate presynaptic glutamate release through distinct mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 2021, 178, 3888–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrie, F. Adrenal androgens and intracrinology. Semin Reprod Med 2004, 22, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewska, M.D. Steroid regulation of the GABAA receptor: ligand binding, chloride transport and behaviour. Ciba Found Symp 1990, 153, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, M.; Sedlacek, M.; Horak, M.; Chodounska, H.; Vyklicky, L., Jr. 20-oxo-5beta-pregnan-3alpha-yl sulfate is a use-dependent NMDA receptor inhibitor. J Neurosci 2005, 25, 8439–8450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, T.; Le Greves, P. The effect of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and allopregnanolone sulfate on the binding of [(3)H]ifenprodil to the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in rat frontal cortex membrane. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2005, 94, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, L.; Gent, R.; van Rooyen, D.; Swart, A.C. Adrenal C11-oxy C(21) steroids contribute to the C11-oxy C(19) steroid pool via the backdoor pathway in the biosynthesis and metabolism of 21-deoxycortisol and 21-deoxycortisone. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017, 174, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, F.V.; Piccoli, V.; Beer, M.A.; von Frankenberg, A.D.; Crispim, D.; Gerchman, F. Association of HSD11B1 polymorphic variants and adipose tissue gene expression with metabolic syndrome, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2015, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottasso, O.; Bay, M.L.; Besedovsky, H.; del Rey, A. The immuno-endocrine component in the pathogenesis of tuberculosis. Scand J Immunol 2007, 66, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, C.; Khalil, M.W.; Sriram, S. Administration of dehydroepiandrosterone suppresses experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in SJL/J mice. J Immunol 2001, 167, 7094–7101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontzsch, A.; Thoss, K.; Petrow, P.K.; Henzgen, S.; Brauer, R. Amelioration of murine antigen-induced arthritis by dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). Inflamm Res 2004, 53, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.D.; Dou, Y.C.; Shi, C.W.; Duan, R.S.; Sun, R.P. Administration of dehydroepiandrosterone ameliorates experimental autoimmune neuritis in Lewis rats. J Neuroimmunol 2009, 207, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.S.; Cui, Y.; Koh, Y.A.; Lee, H.C.; Cho, Y.B.; Won, Y.H. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on Th2 cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from asthmatics. Korean J Intern Med 2008, 23, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudo, N.; Yu, X.N.; Kubo, C. Dehydroepiandrosterone attenuates the spontaneous elevation of serum IgE level in NC/Nga mice. Immunol Lett 2001, 79, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperska-Zajac, A.; Brzoza, Z.; Rogala, B. Dehydroepiandrosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate in atopic allergy and chronic urticaria. Inflammation 2008, 31, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romagnani, S.; Kapsenberg, M.; Radbruch, A.; Adorini, L. Th1 and Th2 cells. Res Immunol 1998, 149, 871–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratschke, S.; von Dossow-Hanfstingl, V.; Dietz, J.; Schneider, C.P.; Tufman, A.; Albertsmeier, M.; Winter, H.; Angele, M.K. Dehydroepiandrosterone modulates T-cell response after major abdominal surgery. J Surg Res 2014, 189, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterzl, I.; Hampl, R.; Sterzl, J.; Votruba, J.; Starka, L. 7Beta-OH-DHEA counteracts dexamethasone induced suppression of primary immune response in murine spleenocytes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1999, 71, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebert, O.; Chalbot, S.; Alran, S.; Morfin, R. Dehydroepiandrosterone 7alpha-hydroxylation in human tissues: possible interference with type 1 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-mediated processes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2007, 104, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Mee, S.; Hennebert, O.; Ferrec, C.; Wulfert, E.; Morfin, R. 7beta-Hydroxy-epiandrosterone-mediated regulation of the prostaglandin synthesis pathway in human peripheral blood monocytes. Steroids 2008, 73, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettersson, H.; Lundqvist, J.; Norlin, M. Effects of CYP7B1-mediated catalysis on estrogen receptor activation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010, 1801, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.; Eggertsen, G.; Chiang, J.Y.; Norlin, M. Estrogen-mediated regulation of CYP7B1: a possible role for controlling DHEA levels in human tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2006, 100, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlem, C.N.; Page, T.M.; Auci, D.L.; Kennedy, M.R.; Mangano, K.; Nicoletti, F.; Ge, Y.; Huang, Y.; White, S.K.; Villegas, S. , et al. Novel components of the human metabolome: the identification, characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of two 5-androstene tetrols. Steroids 2011, 76, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reading, C.L.; Frincke, J.M.; White, S.K. Molecular targets for 17alpha-ethynyl-5-androstene-3beta,7beta,17beta-triol, an anti-inflammatory agent derived from the human metabolome. PLoS One 2012, 7, e32147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.S. Neurosteroids: endogenous role in the human brain and therapeutic potentials. Prog Brain Res 2010, 186, 113–137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Balan, I.; Beattie, M.C.; O'Buckley, T.K.; Aurelian, L.; Morrow, A.L. Endogenous Neurosteroid (3alpha,5alpha)3-Hydroxypregnan-20-one Inhibits Toll-like-4 Receptor Activation and Pro-inflammatory Signaling in Macrophages and Brain. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapchak, P.A. The neuroactive steroid 3-alpha-ol-5-beta-pregnan-20-one hemisuccinate, a selective NMDA receptor antagonist improves behavioral performance following spinal cord ischemia. Brain Res 2004, 997, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudova, E.; Mares, P.; Hill, M.; Vondrakova, K.; Tsenov, G.; Chodounska, H.; Kubova, H.; Vales, K. The Neuroactive Steroid Pregnanolone Glutamate: Anticonvulsant Effect, Metabolites and Its Effect on Neurosteroid Levels in Developing Rat Brains. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, V.; Leal Alvarado, V.; Hill, M.; Smejkalova, T.; Maly, M.; Vales, K.; Dittert, I.; Bozikova, P.; Kysilov, B.; Hrcka Krausova, B. , et al. Effects of Pregnanolone Glutamate and Its Metabolites on GABA(A) and NMDA Receptors and Zebrafish Behavior. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar Cheema, M.; Macakova Kotrbova, Z.; Hrcka Krausova, B.; Adla, S.K.; Slavikova, B.; Chodounska, H.; Kratochvil, M.; Vondrasek, J.; Sedlak, D.; Balastik, M. , et al. 5beta-reduced neuroactive steroids as modulators of growth and viability of postnatal neurons and glia. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2024, 239, 106464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akwa, Y. Steroids and Alzheimer's Disease: Changes Associated with Pathology and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.; Parizek, A.; Simjak, P.; Koucky, M.; Anderlova, K.; Krejci, H.; Vejrazkova, D.; Ondrejikova, L.; Cerny, A.; Kancheva, R. Steroids, steroid associated substances and gestational diabetes mellitus. Physiol Res 2021, 70, S617–S634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burczynski, M.E.; Sridhar, G.R.; Palackal, N.T.; Penning, T.M. The reactive oxygen species--and Michael acceptor-inducible human aldo-keto reductase AKR1C1 reduces the alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehyde 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal to 1,4-dihydroxy-2-nonene. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 2890–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgia, F.; Giagnoni, F.; Lorefice, L.; Caria, P.; Dettori, T.; D'Alterio, M.N.; Angioni, S.; Hendren, A.J.; Caboni, P.; Pibiri, M. , et al. Sex Hormones as Key Modulators of the Immune Response in Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, W.; You, X.; Leimert, K.; Popowycz, K.; Fang, X.; Wood, S.L.; Slater, D.M.; Sun, Q.; Gu, H. , et al. PGF2alpha modulates the output of chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines in myometrial cells from term pregnant women through divergent signaling pathways. Mol Hum Reprod 2015, 21, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Fei, J.; Feng, C.M.; Xu, Z.; Fu, L.; Zhao, H. Serum 8-iso-PGF2alpha Predicts the Severity and Prognosis in Patients With Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 633442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, I.; Dhaliwal, L.K.; Saha, S.C.; Sangwan, S.; Dhawan, V. Role of 8-iso-prostaglandin F2alpha and 25-hydroxycholesterol in the pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2010, 94, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchernof, A.; Mansour, M.F.; Pelletier, M.; Boulet, M.M.; Nadeau, M.; Luu-The, V. Updated survey of the steroid-converting enzymes in human adipose tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2015, 147, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Hornsby, P.J.; Casson, P.; Morimoto, R.; Satoh, F.; Xing, Y.; Kennedy, M.R.; Sasano, H.; Rainey, W.E. Type 5 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3) contributes to testosterone production in the adrenal reticularis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, 2192–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostinelli, G.; Vijay, J.; Vohl, M.C.; Grundberg, E.; Tchernof, A. AKR1C2 and AKR1C3 expression in adipose tissue: Association with body fat distribution and regulatory variants. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2021, 527, 111220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizner, T.L.; Penning, T.M. Role of aldo-keto reductase family 1 (AKR1) enzymes in human steroid metabolism. Steroids 2014, 79, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.L.; Auchus, R.J. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev 2011, 32, 81–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S. , et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.; Hana jr., V.; Velikova, M.; Parizek, A.; Kolatorova, L.; Vitku, J.; Skodova, T.; Simkova, M.; Simjak, P.; Kancheva, R. , et al. A method for determination of one hundred endogenous steroids in human serum by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Physiol Res 2019, 68, 179–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | Follicular phase | Luteal phase | Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | Follicular phase | Luteal phase | Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | Follicular phase | Luteal phase | Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | Follicular phase | Luteal phase | |||

| Steroids | ↓ | 12 | 0 | 17-oxo- Androstanes/#break#estrogens | ↓ | 2 | 0 | CYP17A1,#break#hydroxylase | ↓ | 4 | 1 | AKR1D1 | ↓ | 1 | 0 | |||

| ~ | 66 | 78 | ~ | 19 | 21 | ~ | 8 | 12 | ~ | 10 | 13 | |||||||

| ↑ | 1 | 1 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 1 | 0 | ↑ | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| p | 0.002 | 0.323 | p | 0.168 | 1 | p | 0.193 | 0.356 | p | 0.176 | 1 | |||||||

| Unconjugated steroids | ↓ | 6 | 0 | 17β-hydroxy Androstanes + estrogens | ↓ | 1 | 0 | CYP17A1,#break#lyase | ↓ | 1 | 0 | AKR1C1 vs. HSD17B2 | ↓ | 5 | 0 | |||

| ~ | 38 | 44 | ~ | 14 | 14 | ~ | 7 | 13 | ~ | 9 | 16 | |||||||

| ↑ | 1 | 1 | ↑ | 0 | 1 | ↑ | 5 | 0 | ↑ | 3 | 1 | |||||||

| p | 0.06 | 0.328 | p | 0.351 | 0.351 | p | 0.111 | 1 | p | 0.496 | 0.347 | |||||||

| Conjugated steroids | ↓ | 6 | 0 | 20-oxo-Pregnanes | ↓ | 5 | 0 | HSD3B | ↓ | 1 | 0 | AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6 | ↓ | 2 | 2 | |||

| ~ | 28 | 34 | ~ | 17 | 23 | ~ | 10 | 11 | ~ | 18 | 18 | |||||||

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 1 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| p | 0.015 | 1 | p | 0.107 | 1 | p | 0.363 | 1 | p | 0.168 | 0.168 | |||||||

| C21 steroids (pregnanes) | ↓ | 9 | 0 | 20α-Hydroxy- pregnanes | ↓ | 4 | 0 | Conjugated/#break#unconjugated steroids | ↓ | 7 | 0 | AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6, 3α/β-hydroxy steroids | ↓ | 2 | 2 | |||

| ~ | 33 | 44 | ~ | 16 | 20 | ~ | 19 | 26 | ~ | 11 | 11 | |||||||

| ↑ | 1 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| p | 0.012 | 1 | p | 0.049 | 1 | p | 0.009 | 1 | p | 0.175 | 0.175 | |||||||

| C19 steroids (androstanes) | ↓ | 3 | 0 | 3α-Hydroxy-5α/β-pregnanes | ↓ | 4 | 0 | CYP11B1 | ↓ | 2 | 4 | AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6, 3α-hydroxy/3-oxo steroids | ↓ | 0 | 0 | |||

| ~ | 31 | 33 | ~ | 11 | 15 | ~ | 5 | 3 | ~ | 7 | 7 | |||||||

| ↑ | 0 | 1 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| p | 0.086 | 0.332 | p | 0.05 | 1 | p | 0.192 | 0.056 | p | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Corticoids and 11β-hydroxy-androstanes | ↓ | 4 | 0 | 3-oxo/3β-Hydroxy-5α/β-pregnanes | ↓ | 1 | 0 | CYP7B1, 3A4 | ↓ | 4 | 0 | AKR1C3 | ↓ | 2 | 0 | |||

| ~ | 7 | 11 | ~ | 12 | 14 | ~ | 4 | 8 | ~ | 8 | 12 | |||||||

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 1 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| p | 0.051 | 1 | p | 1 | 1 | p | 0.054 | 1 | p | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| 17-Hydroxy-pregnanes | ↓ | 6 | 0 | 7α/β- and 16α-Hydroxy-steroids | -1 | 2 | 0 | HSD11B1 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| ~ | 8 | 14 | 0 | 6 | 8 | ~ | 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ↑ | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| p | 0.016 | 1 | p | 0.187 | 1 | p | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 17-Deoxy-pregnanes | ↓ | 3 | 0 | CYP17A1,#break#hydroxylase + lyase | ↓ | 3 | 0 | SRD5A | ↓ | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| ~ | 25 | 29 | ~ | 18 | 23 | ~ | 9 | 13 | ||||||||||

| ↑ | 1 | 0 | ↑ | 2 | 0 | ↑ | 3 | 0 | ||||||||||

| p | 0.326 | 1 | p | 0.67 | 1 | p | 0.339 | 1 |

| Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | GA, follicular phase | IFNβ-1a, follicular phase | IFNβ-1a,#break#luteal phase | S1PR inhibitors,#break#follicular phase | Ofatumumab, follicular phase | Ocrelizumab, follicular phase | Ocrelizumab,#break#luteal phase |

| Steroids | ↓ | 0 | 6 | 0 | 11 | 17 | 16 | 20 |

| ~ | 79 | 71 | 58 | 67 | 62 | 62 | 56 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 2 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | |

| p | 1 | 0.159 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Corticoids and 11β-hydroxy-androgens | ↓ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| ~ | 11 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 6 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 0.363 | 0.029 | 0.178 | 0.363 | 0.363 | 0.029 | |

| Δ5 and Δ4 steroids | ↓ | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| ~ | 11 | 27 | 20 | 27 | 22 | 23 | 23 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| p | 1 | 0.087 | 0.002 | 0.087 | 0.005 | 0.061 | 0.061 | |

| Progesterone 5α/β-reduced metabolites | ↓ | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 5 |

| ~ | 26 | 23 | 20 | 18 | 20 | 19 | 19 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| p | 1 | 0.087 | 0.015 | 0.035 | 0.015 | 0.009 | 0.264 | |

| CYP17A1 | ↓ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| ~ | 23 | 18 | 23 | 16 | 23 | 23 | 15 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 0.187 | 1 | 0.061 | 1 | 1 | 0.005 | |

| CYP17A1, hydroxylase | ↓ | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| ~ | 13 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 7 | 6 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 0.092 | 1 | 0.092 | 0.273 | 0.016 | 0.009 | |

| CYP17A1, lyase | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ~ | 11 | 8 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 13 | |

| ↑ | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 0 | |

| p | 0.175 | 0.028 | 1 | 1 | 0.193 | 0.009 | 1 | |

| HSD3Bs | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| ~ | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 9 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.051 | 1 | 0.178 | |

| Conjugated/#break#unconjugated steroids | ↓ | 6 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 |

| ~ | 20 | 22 | 26 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 20 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 0.015 | 0.327 | 1 | 0.186 | 0.106 | 0.048 | 0.015 | |

| CYP11B1 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ~ | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| CYP7B1, CYP3A4, CYP3A7 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| ~ | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 4 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.621 | 0.031 | 0.099 | 0.054 | |

| HSD11B1 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| ~ | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | |

| Steroids and steroid molar ratios | Trend | GA, follicular phase | IFNβ-1a, follicular phase | IFNβ-1a,#break#luteal phase | S1PR inhibitors,#break#follicular phase | Ofatumumab, follicular phase | Ocrelizumab, follicular phase | Ocrelizumab,#break#luteal phase |

| SRD5As | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| ~ | 13 | 13 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 13 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.028 | 0.339 | 0.339 | 1 | |

| AKR1D1 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| ~ | 13 | 13 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 6 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 0.028 | 0.193 | 0.193 | 1 | 0.009 | |

| AKR1C1 vs. HSD17B2 | ↓ | 6 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| ~ | 11 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 15 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 0.015 | 0.676 | 0.676 | 0.268 | 0.333 | 1 | 0.17 | |

| AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6 | ↓ | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| ~ | 15 | 16 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 21 | |

| ↑ | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 0.672 | 0.33 | 0.266 | 1 | 0.427 | 1 | |

| AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6, 3α/β-hydroxy steroids | ↓ | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| ~ | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 14 | |

| ↑ | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| p | 0.682 | 0.337 | 0.091 | 1 | 0.337 | 0.682 | 1 | |

| AKR1C2 vs. HSD17B2 and HSD17B6, 3α-hydroxy/3-oxo ster | ↓ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ~ | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| ↑ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| p | 0.391 | 0.391 | 0.391 | 0.102 | 0.192 | 0.391 | 1 | |

| AKR1C3 vs. HSD17B2 | ↓ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| ~ | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 12 | 9 | |

| ↑ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| p | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.028 | 1 | 0.093 | |

| p = p-value, ↓ = trend to decrease, ~ = absent trend, ↑ = trend to increase, p < 0.05 (bold), p < 0.1 (normal), and p > 0.1 (italics) | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).