1. Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) is a severe neurovascular condition resulting from the spontaneous rupture of an intracranial aneurysm, leading to subarachnoid blood accumulation and significant morbidity and mortality [

1,

2]. It affects 6 to 16 individuals per 100,000 annually, with notable regional disparities: higher incidence rates are reported in East Asia and parts of Europe [

1,

2]. At the same time, resource-limited settings face substantial diagnostic and therapeutic challenges [

1,

2]. Women are predominantly affected, with a peak incidence between 55 and 62 years of age [

3,

4,

5]. Despite advancements in microsurgical and endovascular interventions, global mortality rates and severe disability remain persistently high, affecting approximately 30% of cases [

4,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Complications such as cerebral vasospasm (CVS) and delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) further exacerbate outcomes, with DCI—a significant determinant of poor prognosis—occurring in 25–30% of patients [

4,

10,

11]. This condition emerges within a critical temporal window, providing preventive and therapeutic opportunities. Diagnostic approaches include computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging for detecting irreversible infarctions, alongside non-invasive methods like transcranial Doppler (TCD) and CT perfusion imaging to identify vasospasm’s impact on cerebral perfusion [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Nevertheless, effective treatment strategies remain limited and inconsistent across regions [

15,

16,

17].

This manuscript adopts a narrative review approach due to the nuanced and multifaceted nature of its topic. Unlike systematic reviews, which adhere to rigorous inclusion criteria and predefined search methodologies, narrative reviews prioritize the synthesis of diverse evidence to provide a comprehensive understanding of a specific subject [

18]. In this case, the therapeutic role of milrinone in cerebral vasospasm requires integrating mechanistic insights, clinical data, and expert interpretations. This format is particularly suitable given the complexity of the subject and the limited pool of high-quality studies directly addressing milrinone in this context. A narrative review also facilitates the exploration of clinical implications and the development of actionable treatment algorithms, which are central to the manuscript’s objectives [

19]. By allowing flexibility in study selection and evidence integration, this approach ensures a thorough and practical evaluation of the available data. However, we will transparently acknowledge the inherent limitations of this format, including potential selection bias, in the limitations section.

Historically, CVS management relied on nonspecific and often suboptimal strategies, such as triple-H therapy, which posed significant risks. While mechanical angioplasty was effective, it was restricted to specialized centers with inherent procedural challenges and risks. Pharmacological advances, notably nimodipine and milrinone, represent a paradigm shift, offering targeted therapies with enhanced safety profiles[

1,

2,

20,

21,

22].

Milrinone, in particular, has emerged as a pivotal agent in CVS management. Its dual mechanism of action—direct vasodilation via phosphodiesterase type 3 (PDE3) inhibition and inotropic support—addresses both vascular and perfusion deficits. By improving cerebrovascular autoregulation, reducing endothelial dysfunction, and mitigating neuroinflammation, milrinone offers comprehensive benefits in addressing the multifaceted pathophysiology of CVS [

1,

23,

24,

25,

26]. However, its clinical application necessitates vigilant monitoring due to potential side effects, including hypotension and electrolyte imbalances [

1,

20,

27].

This article evaluates the current evidence supporting milrinone’s role in CVS management. It proposes an evidence-based treatment algorithm that addresses existing gaps in neurocritical care.

2. Literature Review

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) is associated with multiple complications in both the acute and subacute phases, including CVS and DCI, which significantly contribute to morbidity and mortality. CVS, characterized by the narrowing of cerebral arteries, results from a complex interplay of endothelial dysfunction, neuroinflammation, and impaired autoregulatory mechanisms. These processes culminate in hypoperfusion and ischemic injury, often leading to long-term neurological deficits [

2]. Delayed cerebral ischemia, affecting 20–40% of aSAH cases, is the predominant cause of poor functional outcomes in these patients [

22,

23].

Vasospasm typically manifests between the 3rd and 14th day after the hemorrhagic event, peaking around the 7th day [

1,

20,

27,

28,

29]. Its diagnosis relies on cerebral angiography, considered the gold standard, and transcranial Doppler (TCD), which provides a noninvasive bedside assessment with approximately 90% sensitivity [

20]. Clinically, vasospasm is characterized by worsening pre-existing deficits or the emergence of new neurological symptoms, often correlating with ischemic changes on imaging. Although CVS and DCI frequently coexist, they may occur independently [

1,

20,

23].

Given the high prevalence and clinical impact of these complications, daily TCD monitoring is recommended, particularly in sedated patients with subtle clinical signs. Cerebral angiography serves as a diagnostic tool and a therapeutic platform, enabling interventions such as angioplasty [[

27,

30,

31,

32].

While nimodipine remains the only pharmacological agent with robust evidence for vasospasm prevention, its efficacy in treating established vasospasm is limited. Alternative approaches have shown promise, including intra-arterial nicardipine and nimodipine, as well as systemic vasodilators like milrinone. Comparative analyses reveal that milrinone’s dual action—vasodilation and inotropic support—provides distinct advantages in improving cerebrovascular hemodynamics [

27,

31]. For example, intra-arterial nimodipine effectively reverses vasospasm but requires specialized equipment and expertise, limiting its widespread use in resource-constrained settings. Conversely, milrinone’s systemic administration offers broader applicability with comparable clinical outcomes [

1,

20,

23,

27].

Despite these advancements, existing studies exhibit significant methodological limitations, including small sample sizes, protocol heterogeneity, and a lack of randomized controlled trials. Additionally, regional disparities in the availability and application of milrinone underscore the need for standardized guidelines to ensure equitable access and optimized care [

23,

27,

31].

The following table summarizes key studies exploring milrinone’s role in CVS management:

Table 1.

Literature summary—This table provides an overview of key studies examining the use of milrinone in the treatment of CVS. It highlights the study designs, sample sizes, primary findings, and associated limitations.

Table 1.

Literature summary—This table provides an overview of key studies examining the use of milrinone in the treatment of CVS. It highlights the study designs, sample sizes, primary findings, and associated limitations.

| Study |

Design |

Sample Size |

Key Findings |

Limitations |

| Montreal Protocol (2012) [23] |

Observational Cohort |

45 |

Angiographic improvement in 67% of patients; functional improvement in 30% |

Small sample size; observational design |

| MILRISPASM (2021) [26] |

Controlled Before-After |

120 |

Reduction in DCI; fewer mechanical interventions required |

No randomized control |

| Bernier et al. (2021) [24] |

Systematic Review |

500+ |

Demonstrated safety and moderate efficacy of milrinone across multiple studies |

Data heterogeneity |

| Comparative Study: Nimodipine [25] |

Retrospective Cohort |

80 |

Nimodipine superior for prevention; milrinone superior for treatment |

Limited comparative data |

3. Classification of Vasospasm

Vasospasm can be classified as mild (stenosis corresponding to <25%), moderate (25-50%) or severe (>50%). In the case of the anterior circulation, where we use the TCD, vasospasm is classified according to the mean blood flow velocities and the Lindegaard Index (LI—the ratio between the mean velocity in the intracranial artery and the corresponding mean velocity in the internal carotid artery that supplies it) [

23,

24,

28]. The classification criteria are summarized in

Table 2, which outlines the thresholds for mean flow velocities and Lindegaard Index values used to categorize vasospasm severity [

23,

24,

28]:

While the TCD is a valuable bedside tool, it has limitations. Its accuracy depends on the operator's expertise, and it may be less reliable in patients with poor acoustic windows or complex vascular anatomy. Additionally, TCD focuses on velocity changes, which do not always correlate with functional hemodynamic significance [

20,

29].

In posterior circulation, the index used is the Sviri Index, which is determined by the ratio between the mean flow velocities in the basilar/posterior cerebral arteries and the average velocity in both vertebral arteries [

33].

Table 3 presents the classification criteria for vasospasm in posterior circulation based on mean flow velocities and the Sviri Index, categorizing it as possible, moderate, or severe.

The Sviri Index provides a structured approach to classifying vasospasm. However, baseline anatomic variations and coexisting pathologies can influence it in cases where TCD findings are equivocal; further imaging with CT or MR angiography is often required [

33].

Cerebral angiography classifies CVS not based on circulation velocities but rather by identifying luminal filling defects and based on cerebral hemodynamics [

33]. Remains the gold standard for diagnosing vasospasm in both anterior and posterior circulations. Unlike TCD-based indices, angiography allows direct visualization of luminal narrowing and hemodynamic alterations [

34]. However, it is an invasive procedure with associated risks, including stroke and vessel injury. Despite these risks, angiography provides critical insights into the severity and distribution of vasospasm, informing therapeutic decisions such as chemical or mechanical angioplasty [

27,

35]:

Chemical Angioplasty involves the direct intra-arterial administration of vasoactive drugs to the cerebral circulation. This approach effectively targets localized vasospasm with fewer secondary systemic effects but requires specialized expertise [

35].

Mechanical Angioplasty: Utilizes inflatable balloons or stents to dilate affected arterial segments. It provides immediate relief but is associated with procedural risks and limited availability [

35].

Intravenous milrinone has emerged as a promising therapy for treating established vasospasm, effectively addressing vascular and perfusion deficits. Studies highlight its potential to reduce delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) and improve functional outcomes, although further research is needed to standardize its use [

27,

35].

4. Milrinone Pharmacodynamics

Milrinone, a selective PDE3 inhibitor, has established itself as a cornerstone in the management of cerebral vasospasm (CVS) associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH). It is a PDE3 inhibitor that has a positive inotropic effect on the myocyte and a vasodilatory impact on the smooth muscle of the vessels. It has a half-life of about 2.5 hours and a distribution volume of 0.38 l/kg. It is a highly eliminated drug that is 70% bound to plasma proteins [

1].

Its pharmacodynamic profile encompasses a multifaceted approach, including vascular smooth muscle relaxation, enhanced myocardial contractility, and anti-inflammatory effects, making it a versatile agent in neurocritical care [

1,

23]. By inhibiting PDE3, an enzyme responsible for the degradation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), milrinone increases intracellular cAMP levels in vascular smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes. This elevation in cAMP promotes relaxation of vascular smooth muscle by reducing intracellular calcium concentrations, effectively decreasing vascular tone and enhancing cerebral blood flow. This vasodilatory effect, mediated through elevated cAMP, is pivotal in counteracting pathological vasoconstriction, enabling cerebral vessels to dynamically adapt to systemic pressure changes and restore perfusion in ischemic territories [

1,

20,

23,

27].

In cardiac myocytes, increased cAMP enhances calcium influx during systole, thereby improving myocardial contractility and overall cardiac output. This dual mechanism ensures adequate systemic and cerebral perfusion, particularly in hemodynamically unstable patients at high risk of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI). Furthermore, milrinone’s vasodilatory action extends to the endothelium, enhancing nitric oxide bioavailability and reducing oxidative stress, mitigating endothelial dysfunction, a critical factor in the pathophysiology of CVS [

24,

25,

26,

29]. Emerging evidence also suggests that milrinone possesses significant anti-inflammatory properties, including modulation of inflammatory cytokines and reduction of leukocyte-endothelial interactions. These effects contribute to preserving cerebrovascular endothelial integrity and attenuate the neuroinflammatory cascade, which is essential for maintaining autoregulatory responses and preventing further ischemic damage [

24,

25,

26,

29].

The clinical implications of milrinone’s pharmacodynamics are profound. Studies have demonstrated significant improvements in cerebral blood flow following its administration, as evidenced by reductions in mean flow velocities measured via transcranial Doppler (TCD) [

2]. Additionally, its dual action on vascular tone and cardiac function addresses the vascular and perfusion deficits that are hallmarks of CVS. This comprehensive approach has been associated with improved functional outcomes, including reduced incidence of DCI and better modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at six months [

33,

34]. The Montreal Protocol, a widely referenced standard for milrinone administration, reported angiographic improvement in 67% of patients, with complete resolution of vasospasm in 30%. These findings underscore the potential of milrinone to enhance recovery and optimize long-term outcomes [

23,

36].

Milrinone’s pharmacodynamic effects are dose-dependent, allowing for tailored treatment strategies. Low to moderate doses (0.75–1.25 µg/kg/min) primarily achieve vasodilation with minimal systemic effects, making them suitable for patients with mild to moderate vasospasm. Higher doses (1.5–2.0 µg/kg/min) provide additional inotropic support, which is particularly beneficial for patients with concurrent cardiac dysfunction. The maximum recommended dose of 2.5 µg/kg/min is reserved for select cases under close hemodynamic monitoring to balance therapeutic benefits against the risk of adverse effects [

23,

25,

37].

While milrinone offers significant therapeutic advantages, its use is not without challenges. Excessive vasodilation can lead to systemic hypotension, compromising cerebral perfusion. This complication often necessitates volume resuscitation and the administration of vasopressors, such as norepinephrine, to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure [

23,

29]. Tachycardia, another potential side effect, may require dose adjustments, especially in patients with limited cardiac reserve [

26]. Moreover, alterations in cAMP levels can impact renal function and electrolyte balance, particularly potassium levels, necessitating proactive monitoring to prevent arrhythmias [

24]. Therefore, continuous monitoring of hemodynamic parameters and proactive correction of electrolyte imbalances are critical to minimizing these risks and ensuring safe and effective treatment.

Emerging research has begun to explore the impact of milrinone on specific inflammatory biomarkers, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), which are implicated in the pathogenesis of neuroinflammation in CVS. Preliminary findings suggest that milrinone may attenuate the release of these cytokines, further supporting its role in modulating the inflammatory response [

36,

38,

39,

40]. This aspect of its pharmacodynamics highlights its potential as part of a comprehensive therapeutic strategy that extends beyond vasodilation and inotropic support.

Milrinone’s versatility is particularly valuable when first-line therapies fail or are insufficient. However, its clinical application in resource-limited settings poses additional challenges. The need for advanced monitoring equipment and multidisciplinary expertise can limit its accessibility. Strategies to address these barriers include developing simplified protocols and training programs for healthcare providers to optimize its use in diverse clinical environments. Collaborative research efforts focusing on cost-effectiveness and integrating milrinone into existing treatment frameworks are crucial to expanding its applicability [

23,

28].

In conclusion, milrinone’s pharmacodynamic properties underscore its potential as a cornerstone therapy for managing CVS. By addressing both vascular spasms and perfusion deficits, it bridges critical gaps in the treatment of aSAH-associated complications. Ongoing research into its long-term effects, impact on inflammatory pathways, and integration with adjunctive therapies will further refine its role, paving the way for enhanced patient care and improved neurocritical outcomes [

26,

28,

37].

5. Treatment Orientations

Milrinone therapy is most beneficial in patients with moderate to severe CVS who have failed to respond to first-line treatments. Key criteria include [

1,

23,

26,

26,

29]:

- ○

Focal neurological deficits (e.g., hemiparesis, aphasia) [

1,

23].

- ○

Reduced level of consciousness sustained over 1 hour [

10,

22].

- 3.

Exclusion of alternative etiologies for neurological deterioration, such as hydrocephalus, metabolic imbalances, or seizures [

4,

35]

Contraindications

Absolute:

Hypersensitivity to milrinone [

23].

Severe aortic stenosis or obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [

24].

Refractory hypotension [

28].

Relative:

Cardiac dysfunction (elevated troponins, reduced ejection fraction) [

25].

Severe electrolyte disturbances (e.g., hypokalemia, hypermagnesemia) [

26].

Significant renal impairment (GFR <30 mL/min) [

31].

Based on existing literature and the review made, the following administration steps are resumed in an orientation board that can be used in a pocket guide or displayed for consultation:

Administration Protocol:

Initial Bolus: Administer 0.1 mg/kg over 10 minutes [

23].

Continuous Infusion: Start at 0.75 µg/kg/min and titrate in increments of 0.25 µg/kg/min every hour, guided by neurological improvement and hemodynamic stability [

20,

21,

27]:

- ○

Mild Vasospasm: 0.75-1.25 µg/kg/min [

21,

27].

- ○

Moderate Vasospasm: 1.0-1.5 µg/kg/min [

21,

23,

26].

- ○

Severe Vasospasm: 1.0-2.0 µg/kg/min [

21,

23,

26,

28].

- 3.

Maximum Dose: Typically, it is 2.0 µg/kg/min, with selective escalation to 2.5 µg/kg/min under multidisciplinary consensus [

21,

26].

- 4.

Reevaluation: Perform follow-up TCD or angiography within 24 hours. If there is no improvement, escalate to endovascular therapy [

20,

35].

Monitoring and Adaptations:

-

1.

Hemodynamic Monitoring:

- ○

Continuous invasive blood pressure monitoring [

20,

26].

- ○

Vasopressor support (e.g., norepinephrine) to maintain MAP ≥90 mmHg [

24,

28].

-

2.

Neurological Assessment:

- ○

Regular clinical evaluations for improvement in focal deficits [

10,

22].

- ○

Daily TCD for the first 14 days post-aSAH or until vasospasm resolution [

21,

27,

31].

-

3.

Resource-Limited Settings:

- ○

Simplify monitoring by prioritizing TCD and clinical signs over advanced imaging [

23,

28].

- ○

Adjust dosing to available resources and prioritize early identification of candidates for escalation [

24,

35].

This refined protocol integrates existing evidence while addressing practical challenges in diverse clinical environments, offering a streamlined approach to optimizing outcomes in CVS management.

6. Selection of Patients

Patients with excluded aneurysms who meet the following criteria are candidates for treatment:

Clinical signs with or without Vasospasm on TCD or moderate to severe vasospasm demonstrated on cerebral angiography [

23,

24,

28].

No clinical changes but moderate to severe vasospasm detected on TCD during daily monitoring and confirmed by cerebral angiography [

38,

41].

No clinical changes but vasospasm suggested by other monitoring methods (PtiO₂- Partial Pressure of Brain Tissue Oxygenation, NIRS - Near-Infrared Spectroscopy, EEG - Electroencephalography) after confirmed by cerebral angiography [

2,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Clinical alteration suggestive of DCI can be assumed when:

Sustained new focal neurological deficit for at least one hour not attributable to other clinical events identified by imaging or laboratory examination [

25,

36].

New Neurological Deficit/Symptom Criteria, defined as:

- I.

Altered level of consciousness and/or orientation in at least two serial evaluations [

23,

24,

28,

47].

- II.

Decline in the Full Outline of UnResponsiveness (FOUR) score by two or more points [

23,

24,

28,

47].

- III.

Cranial nerve paresis, speech/language alteration, apraxia, hemianopsia, neglect, and/or any new focal motor deficit [

23,

24,

28,

47].

- IV.

Rapid onset deficit (within a 4-hour window) [

23,

24,

28,

47].

- V.

Headache refractory to analgesic therapy [

23,

24,

28,

47].

Contraindications:

Absolute: Hypersensitivity to milrinone, aortic or pulmonary valve stenosis, obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, acute coronary syndrome, malignant arrhythmia, severe refractory hypotension, significant renal insufficiency (GFR <30), and/or dialysis dependency [

23,

24,

26,

28,

47].

Relative: Worsening cardiac output, elevated troponin, severe ionic alterations, and severe thrombocytopenia (<50,000) [

25,

36].

7. Initial Assessment

In the context of aSAH, the initial assessment aims to exclude other causes of neurological alteration and/or confirm the presence of CVS [

23,

24,

28].

Neurological Assessment:

Conduct a detailed neurological examination, including the FOUR Score [

41,

47].

Hemodynamic Monitoring:

Continuous invasive blood pressure monitoring, heart rate, and ECG tracing [

28,

36].

Transthoracic echocardiography should be used when justified, especially before and after therapy initiation [

28,

30,

36].

Consider advanced hemodynamic monitoring in suspected shock or high vasopressor doses [

28,

36,

41,

48]

Laboratory Tests:

- ●

Obtain baseline values and daily monitoring of the following:

- ○

Complete blood count [

28,

36,

41].

- ○

Electrolyte panel (Na⁺, K⁺, P⁺, Mg²⁺, Ca⁺) [

28,

36,

41,

49]

- ○

- ●

Request cardiac enzymes if myocardial injury is suspected [

49].

8. Initiation of Milrinone Infusion

After confirming the degree of vasospasm by TCD and cerebral angiography, initiate milrinone infusion according to the following protocol [

24,

28,

29]:

- 1.

Administer an initial bolus of 0.1 mg/kg over 10 minutes [

35].

- 2.

Start continuous infusion at 0.75 µg/kg/min [

24].

- 3.

Titrate the infusion hourly in increments of 0.25 µg/kg/min until neurological improvement is observed or the target dose for the vasospasm severity is reached:

- ●

Mild Vasospasm: 0.75–1.25 µg/kg/min [

28,

29].

- ●

Moderate Vasospasm: 1.0–1.5 µg/kg/min [

28,

29].

- ●

Severe Vasospasm: 1.0–2.0 µg/kg/min [

28,

29,

35].

- 4.

The maximum recommended dose is 2.0 µg/kg/min. Some studies support up to 2.5 µg/kg/min for select cases under multidisciplinary review [

24,

28,

51].

- 5.

Use isolated NA up to a maximum of 0.5 µg/kg/min. If the target MAP is not achieved, consider introducing vasopressin [

29,

48,

52,

53].

- 6.

Whenever the dose of milrinone exceeds 1.0 µg/kg/min and NA superior to 0.5µg/kg/min must be simultaneously administered, invasive hemodynamic monitoring through transpulmonary thermodilution is recommended [

29,

48,

52,

53].

- 7.

Use invasive hemodynamic monitoring via transpulmonary thermodilution for norepinephrine (NA) doses >1.0 µg/kg/min [

29,

48,

52,

53].

- 8.

If no improvement occurs or clinical worsening persists, repeat cerebral angiography and consider endovascular treatment [

35].

9. Monitoring of Milrinone Treatment

Monitoring during milrinone treatment is critical for ensuring efficacy and safety [

24,

26,

36].

Clinical Assessment:

Perform assessments every 30–60 minutes until symptoms improve or the maximum dose is reached, and after that, at least every 8 hours [

36].

Daily TCD Monitoring:

Continue until 14 days post-event and aneurysm exclusion [

28].

Extend until vasospasm resolution [

21,

51].

Sedated or altered consciousness patients:

Use a second monitoring method, preferably continuous (e.g., EEG with spectral analysis, PtiO₂ monitoring, microdialysis, or NIRS) [

2,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46].

Hemodynamic Management:

Address hypotension related to drug administration as follows:

Discontinue all hypotensive agents except nimodipine [

26,

37].

Initiate volume resuscitation with crystalloids to achieve euvolemia [

24,

26,

37].

Start vasopressor support with NA targeting MAP >90 mmHg or optimized CPP [

28].

Use transpulmonary thermodilution monitoring if NA >0.5 µg/kg/min is needed alongside milrinone >1.0 µg/kg/min [

36,

48,

52].

Reduce milrinone infusion by 0.25 µg/kg/min every 1–2 hours if hemodynamic instability persists [

26,

36].

Imaging: All patients should undergo a CT-CE study within the first 48 hours of treatment initiation [

21,

21,

24,

29,

34].

10. Other Care (for All Patients)

Administer nimodipine 60 mg every 4 hours for 21 days as standard treatment for aSAH [

23,

36].

Maintain euvolemia with balanced fluid monitoring and renal function assessment [

51].

Ensure normothermia and normoglycemia [

21,

51].

Favor a hyperosmolar environment (serum sodium >140 mEq/L) [

21,

51].

Correct ionic and acid-base imbalances [

21,

51].

Optimize hematology with transfusion support targeting hemoglobin >9.0 g/dL when necessary [

54,

55,

56].

11. Discontinuation

Milrinone therapy should continue until vasospasm resolution is confirmed by TCD or angiography [

23,

24,

26]:

Gradually taper the infusion by 0.25 µg/kg/min every 12–24 hours until reaching 0.75 µg/kg/min, then discontinue [

26].

In case of clinical or imaging deterioration during tapering, administer a new bolus (0.05 mg/kg) and increase the infusion rate to the effective dose [

24,

26].

If severe side effects occur or no clinical improvement is observed after 72 hours at the optimal dose, discontinue therapy [

18].

12. Documentation and Communication

We suggest documenting all clinical and imaging evaluations, dosage adjustments, and patient clinical responses in a standardized table (

Table 3).

Team communication: maintain regular communication with the multidisciplinary team, including Neurosurgery and Neuroradiology.

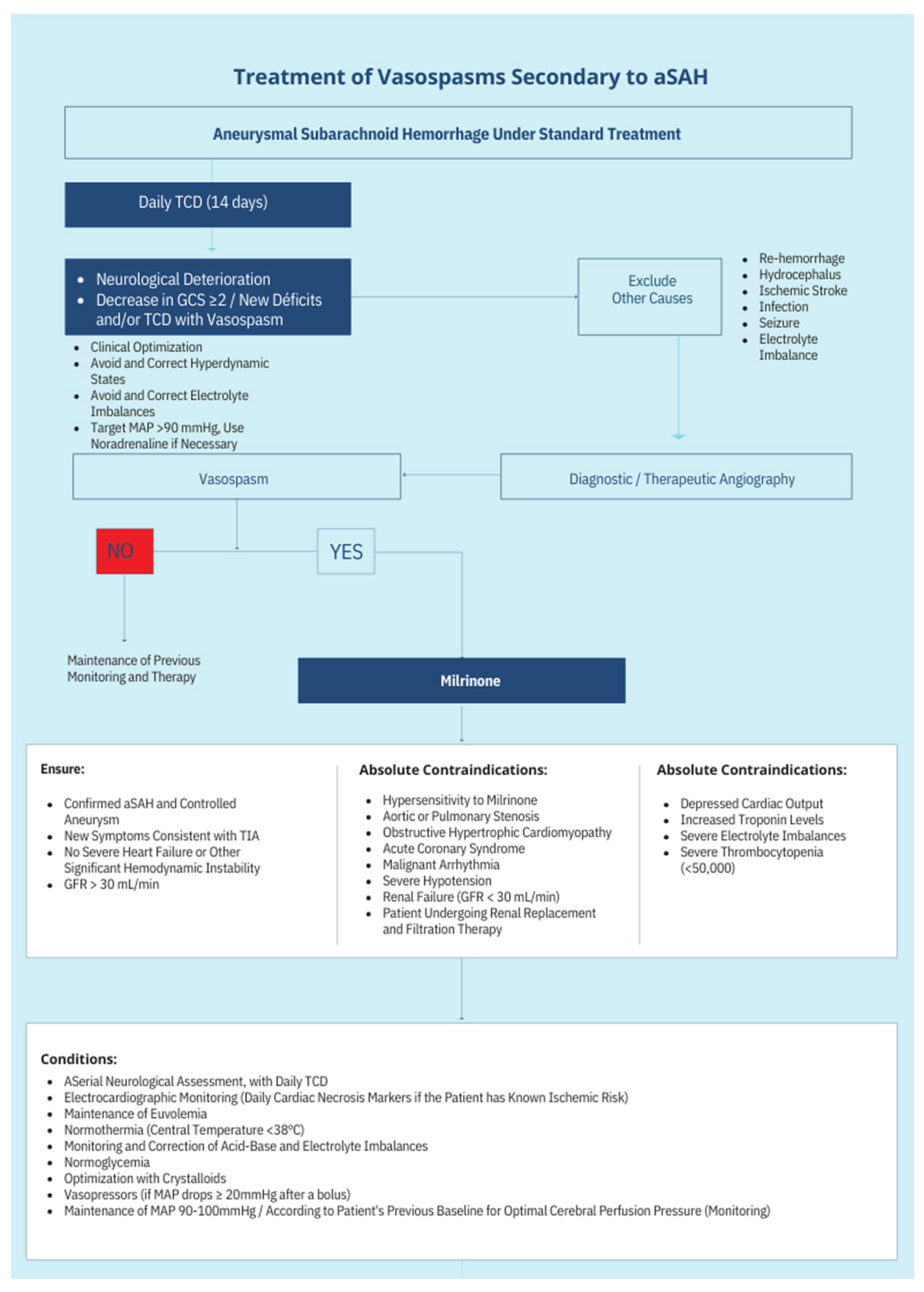

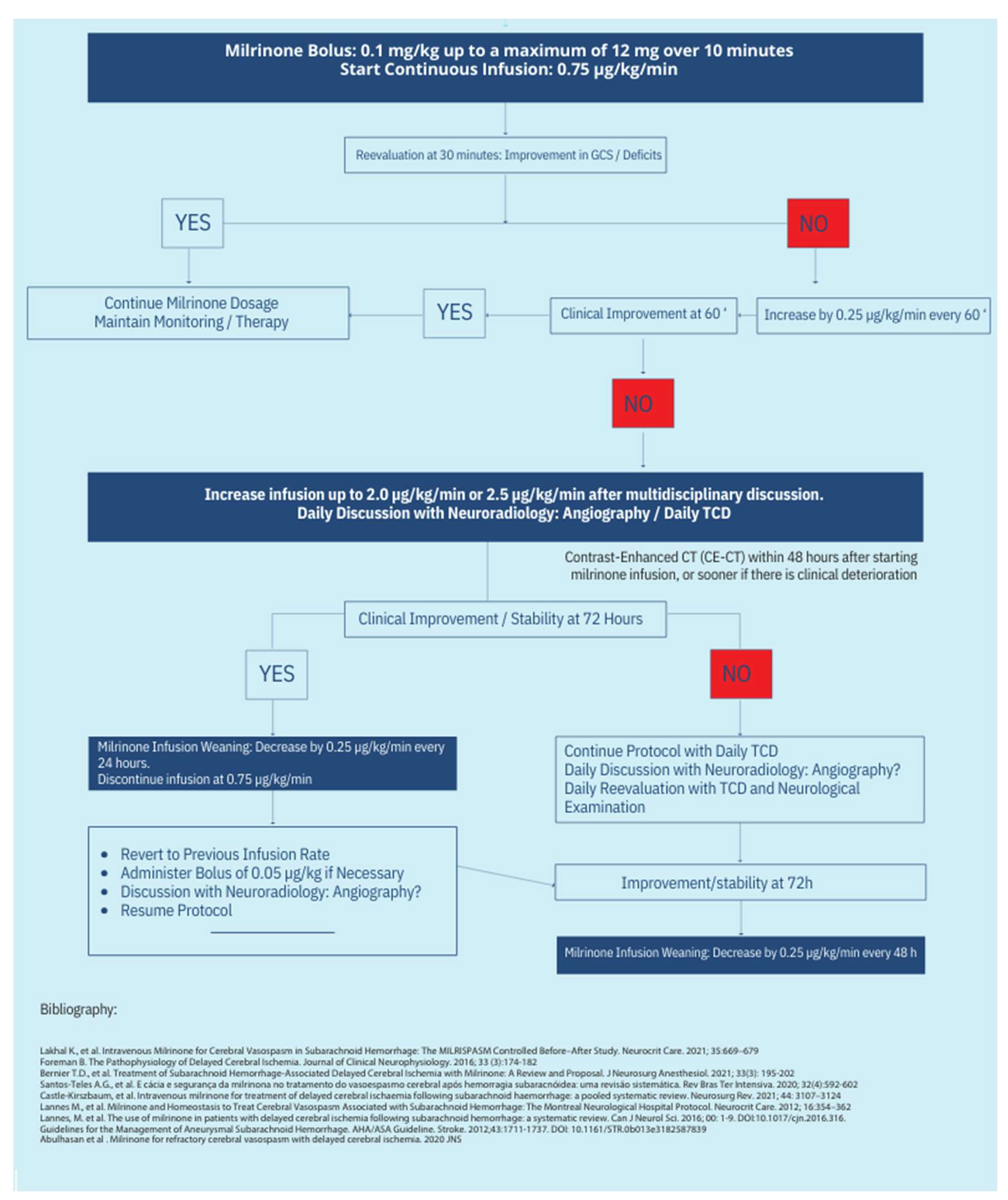

13. Protocol Schematics

The treatment protocol’s complete schematics can be seen in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

14. Discussion

The available evidence underscores the efficacy of milrinone as an adjunctive therapy for CVS management in aSAH patients. Milrinone’s integration into neurocritical care represents a paradigm shift in managing CVS and DCI, providing an alternative to conventional therapies with limitations. Nimodipine remains the gold standard for vasospasm prevention; however, its efficacy in treating established vasospasm is limited. Milrinone addresses this gap with its unique dual mechanism of vasodilation and inotropic support, which improves cerebrovascular perfusion and mitigates ischemic injury. Its dual vasodilatory and inotropic properties address vascular and perfusion deficits, which are critical in preventing DCI. Notably, the Montreal Protocol and MILRISPAN study have provided a standardized framework for its administration, enhancing reproducibility and outcomes [

24,

30].

Comparative studies reveal nuanced advantages and limitations across therapies. Intra-arterial nicardipine effectively reverses vasospasm but requires specialized infrastructure and expertise, making it less feasible in resource-constrained environments. Systemic milrinone offers a more accessible alternative with demonstrated angiographic and clinical efficacy [

26,

51]. Mechanical angioplasty, another established option, provides immediate relief but carries procedural risks and is limited to specific indications, such as refractory vasospasm [

20,

41].

Despite its promise, milrinone’s clinical application poses challenges. Continuous hemodynamic monitoring necessitates advanced critical care capabilities, which may not be universally available. Additionally, its side-effect profile, including hypotension and electrolyte imbalances, underscores the need for vigilant monitoring and multidisciplinary management [

26,

28]. These limitations highlight the importance of tailoring treatment protocols to individual patient needs and institutional resources.

Future research directions include large-scale RCTs to validate current findings and enhance the generalizability of evidence. Additionally, exploring biomarkers to predict treatment response and developing advanced monitoring technologies could further refine milrinone’s therapeutic role. Studies focusing on cost-effectiveness and resource allocation are also critical to optimizing its use in diverse healthcare settings.

Research, future directions:

Randomized Controlled Trials: we still need large multicenter trials to validate the efficacy and safety of milrinone compared to other therapies.

Biomarker Research: Investigating biomarkers predictive of treatment response could facilitate patient stratification and optimize outcomes.

Combination Therapies: Exploring the synergistic effects of milrinone with other pharmacologic agents or interventions may enhance therapeutic efficacy.

Technological Integration: Advanced imaging and monitoring technologies, such as automated TCD and perfusion MRI, could refine patient selection and treatment monitoring.

Milrinone has emerged as a viable therapeutic option for managing CVS associated with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. It provides a dual mechanism of action by improving vascular relaxation and enhancing cardiac output, addressing critical pathophysiological elements of CVS and DCI. Implementing standardized protocols, such as the Montreal Protocol, has demonstrated reproducible benefits, particularly in reducing the incidence of DCI and improving long-term neurological outcomes. However, hemodynamic instability and patient-specific variability highlight the need for meticulous monitoring and individualized treatment plans.

Our recommendations for Clinical Practice:

Protocol Adherence: Follow evidence-based protocols for milrinone administration, ensuring dose adjustments based on clinical response and side effect profiles.

Multidisciplinary Approach: Engage neurosurgery, neurocritical care, and interventional neuroradiology teams in patient management.

Patient Selection: Carefully assess eligibility criteria, prioritizing patients with moderate to severe vasospasm refractory to standard therapies.

Monitoring: Implement comprehensive hemodynamic and neurological monitoring throughout the treatment course to mitigate risks and optimize outcomes.

Future Research Participation: Encourage institutional participation in multicenter trials to further refine the evidence base for milrinone use.

This discussion underscores the evolving role of milrinone in CVS and DCI management, emphasizing its potential to improve patient outcomes while acknowledging the need for continued innovation and evidence generation.

An analysis of the funding sources and potential conflicts of interest among the included studies revealed no significant economic biases that could influence the findings. Furthermore, this review was conducted independently, without any financial support or sponsorship from the pharmaceutical or medical device industries. These factors ensure that the interpretations and conclusions presented are free from economic bias, reflecting an objective synthesis of the evidence.

But, we need to underscore that this review has several limitations. First, as a narrative review, it is inherently subject to selection bias, as studies were chosen based on their relevance and significance rather than systematic inclusion criteria. Second, the limited number of high-quality studies specifically addressing milrinone in cerebral vasospasm restricts the generalizability of conclusions. Finally, while clinical applicability was emphasized, direct translation of findings into practice remains challenging due to varying study designs and patient populations.

15. Conclusion

Although milrinone is primarily a drug used in Cardiology, significant reports of its use in preventing CVS and DCI in aSAH have been made in the past twenty years. In 2012, the Montreal administration protocol promoted the widespread adoption of this therapy, and in 2021, the MILRISPAM study confirmed its safety and efficacy.

Milrinone has emerged as a promising therapeutic option for managing CVS and DCI following aSAH. Its dual mechanisms of action—vasodilation through PDE3 inhibition and inotropic support—uniquely address both vascular and perfusion deficits, setting it apart from conventional treatments. These properties enable milrinone to play a pivotal role in improving cerebral hemodynamics and reducing ischemic injury.

Despite its potential, milrinone’s application is not without challenges. Careful patient selection and vigilant hemodynamic monitoring are essential to minimize risks associated with its use, such as hypotension and electrolyte imbalances. A multidisciplinary approach involving intensivists, neurologists, and interventional radiologists is critical for optimizing therapeutic outcomes. Additionally, limitations in the current body of evidence—including small sample sizes, methodological heterogeneity, and a lack of large-scale randomized trials—highlight the need for further research.

Future studies should validate existing findings through robust multicentric randomized trials and explore biomarkers that can predict treatment response. Cost-effectiveness analyses and the development of advanced monitoring technologies are equally crucial for optimizing the utility of milrinone, particularly in resource-limited settings where access to alternative therapies may be constrained. International collaboration in research and the implementation of standardized protocols can help bridge regional disparities and ensure the broader applicability of milrinone in neurocritical care.

In conclusion, milrinone represents a valuable addition to the therapeutic arsenal for CVS and DCI, addressing critical gaps in current management strategies. By continuing to advance research and foster collaboration, the neurocritical care community can fully realize its potential and improve outcomes for patients with aSAH.

References

- Castle-Kirszbaum M, Lai L, Maingard J, Asadi H, Danks RA, Goldschlager T, et al. Intravenous milrinone for treatment of delayed cerebral ischaemia following subarachnoid haemorrhage: a pooled systematic review. Neurosurg Rev 2021;44:3107–24. [CrossRef]

- Suarez JI, Tarr RW, Selman WR. Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. N Engl J Med 2006;354:387–96. [CrossRef]

- Neifert SN, Chapman EK, Martini ML, Shuman WH, Schupper AJ, Oermann EK, et al. Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: the Last Decade. Transl Stroke Res 2021;12:428–46. [CrossRef]

- Chalard K, Szabo V, Pavillard F, Djanikian F, Dargazanli C, Molinari N, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage requiring mechanical ventilation. PLOS ONE 2021;16:e0247942. [CrossRef]

- Hoh BL, Ko NU, Amin-Hanjani S, Chou SH-Y, Cruz-Flores S, Dangayach NS, et al. 2023 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2023;54:e314–70. [CrossRef]

- Mackey J, Khoury JC, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Kissela BM, Flaherty ML, et al. Stable incidence but declining case-fatality rates of subarachnoid hemorrhage in a population. Neurology 2016;87:2192–7. [CrossRef]

- Wahood W, Rizvi AA, Alexander AY, Yolcu YU, Lanzino G, Brinjikji W, et al. Trends in Admissions and Outcomes for Treatment of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in the United States. Neurocrit Care 2022;37:209–18. [CrossRef]

- Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Birks J, Ramzi N, Yarnold J, Sneade M, et al. Risk of recurrent subarachnoid haemorrhage, death, or dependence and standardised mortality ratios after clipping or coiling of an intracranial aneurysm in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT): long-term follow-up. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:427–33. [CrossRef]

- Cinotti R, Putegnat J-B, Lakhal K, Desal H, Chenet A, Buffenoir K, et al. Evolution of neurological recovery during the first year after subarachnoid haemorrhage in a French university centre. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2019;38:251–7. [CrossRef]

- Galea JP, Dulhanty L, Patel HC, UK and Ireland Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Database Collaborators. Predictors of Outcome in Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Patients: Observations From a Multicenter Data Set. Stroke 2017;48:2958–63. [CrossRef]

- Rowland MJ, Hadjipavlou G, Kelly M, Westbrook J, Pattinson KTS. Delayed cerebral ischaemia after subarachnoid haemorrhage: looking beyond vasospasm. Br J Anaesth 2012;109:315–29. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-C, Hung M-S, Liu C-Y, Hsiao C-T, Yang Y-H. The association of emergency department administration of sodium bicarbonate after out of hospital cardiac arrest with outcomes. Am J Emerg Med 2018;36:1998–2004. [CrossRef]

- Kumar G, Shahripour RB, Harrigan MR. Vasospasm on transcranial Doppler is predictive of delayed cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review and meta-analysis 2016. [CrossRef]

- Westermaier T, Pham M, Stetter C, Willner N, Solymosi L, Ernestus R-I, et al. Value of Transcranial Doppler, Perfusion-CT and Neurological Evaluation to Forecast Secondary Ischemia after Aneurysmal SAH. Neurocrit Care 2014;20:406–12. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Manoel AL, Goffi A, Marotta TR, Schweizer TA, Abrahamson S, Macdonald RL. The critical care management of poor-grade subarachnoid haemorrhage. Crit Care 2016;20:21. [CrossRef]

- Malinova V, Dolatowski K, Schramm P, Moerer O, Rohde V, Mielke D. Early whole-brain CT perfusion for detection of patients at risk for delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage 2016. [CrossRef]

- Francoeur CL, Mayer SA. Management of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care 2016;20:277. [CrossRef]

- Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J 2009;26:91–108. [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh T. How to Read a Paper n.d.

- Fraticelli AT, Cholley BP, Losser M-R, Saint Maurice J-P, Payen D. Milrinone for the treatment of cerebral vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 2008;39:893–8. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan C, Shukla RK, Kapoor I, Prabhakar H. Intravenous Milrinone for Cerebral Vasospasm in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2022;36:327–8. [CrossRef]

- Harrod CG, Bendok BR, Batjer HH. Prediction of Cerebral Vasospasm in Patients Presenting with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Review. Neurosurgery 2005;56:633. [CrossRef]

- Lannes M, Teitelbaum J, del Pilar Cortés M, Cardoso M, Angle M. Milrinone and homeostasis to treat cerebral vasospasm associated with subarachnoid hemorrhage: the Montreal Neurological Hospital protocol. Neurocrit Care 2012;16:354–62. [CrossRef]

- Bernier TD, Schontz MJ, Izzy S, Chung DY, Nelson SE, Leslie-Mazwi TM, et al. Treatment of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage-Associated Delayed Cerebral Ischemia with Milrinone: A Review and Proposal. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2021;33:195–202. [CrossRef]

- Rabinstein AA, Friedman JA, Nichols DA, Pichelmann MA, McClelland RL, Manno EM, et al. Predictors of Outcome after Endovascular Treatment of Cerebral Vasospasm. Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1778–82.

- Lakhal K, Hivert A, Alexandre P-L, Fresco M, Robert-Edan V, Rodie-Talbere P-A, et al. Intravenous Milrinone for Cerebral Vasospasm in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: The MILRISPASM Controlled Before–After Study. Neurocrit Care 2021;35:669–79. [CrossRef]

- Keyrouz SG, Diringer MN. Clinical review: Prevention and therapy of vasospasm in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care 2007;11:220. [CrossRef]

- Anetsberger A, Gempt J, Blobner M, Ringel F, Bogdanski R, Heim M, et al. Impact of Goal-Directed Therapy on Delayed Ischemia After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: Randomized Controlled Trial. Stroke 2020;51:2287–96. [CrossRef]

- Crespy T, Heintzelmann M, Chiron C, Vinclair M, Tahon F, Francony G, et al. Which Protocol for Milrinone to Treat Cerebral Vasospasm Associated With Subarachnoid Hemorrhage? J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2019;31:323. [CrossRef]

- Carr KR, Zuckerman SL, Mocco J. Inflammation, Cerebral Vasospasm, and Evolving Theories of Delayed Cerebral Ischemia. Neurol Res Int 2013;2013:506584. [CrossRef]

- Badjatia N, Topcuoglu MA, Pryor JC, Rabinov JD, Ogilvy CS, Carter BS, et al. Preliminary experience with intra-arterial nicardipine as a treatment for cerebral vasospasm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:819–26.

- Liu D, Kahn M. Measurement and relationship of subarachnoid pressure of the optic nerve to intracranial pressures in fresh cadavers. Am J Ophthalmol 1993;116:548–56. [CrossRef]

- Sviri GE, Ghodke B, Britz GW, Douville CM, Haynor DR, Mesiwala AH, et al. Transcranial Doppler grading criteria for basilar artery vasospasm. Neurosurgery 2006;59:360–6; discussion 360-366. [CrossRef]

- https://fyra.io. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Vasospasm, and Delayed Cerebral Ischemia. Pract Neurol n.d. https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2019-jan/subarachnoid-hemorrhage-vasospasm-and-delayed-cerebral-ischemia (accessed July 19, 2024).

- Liu Y, Qiu H-C, Su J, Jiang W-J. Drug treatment of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage following aneurysms. Chin Neurosurg J 2016;2:4. [CrossRef]

- Treggiari MM, Rabinstein AA, Busl KM, Caylor MM, Citerio G, Deem S, et al. Guidelines for the Neurocritical Care Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care 2023;39:1–28. [CrossRef]

- Robert-Edan V, Lakhal K. Treating Vasospasm with IV Milrinone: Relax (The Vessel) or Don’t Do It! Neurocrit Care 2023;39:547–8. [CrossRef]

- Sviri GE, Zaaroor M, Britz GW, Douville CM, Lam A, Newell DW. Basilar artery vasospasm: diagnosis and grading by transcranial Doppler. In: Kırış T, Zhang JH, editors. Cereb. Vasospasm, vol. 104, Vienna: Springer Vienna; 2008, p. 255–7. [CrossRef]

- Shao T, Zhang Y, Tang R, Zhang H, Wang Q, Yang Y, et al. Effects of milrinone on serum IL-6, TNF-α, Cys-C and cardiac functions of patients with chronic heart failure. Exp Ther Med 2018;16:4162–6. [CrossRef]

- Lanfear DE, Hasan R, Gupta RC, Williams C, Czerska B, Tita C, et al. Short term effects of milrinone on biomarkers of necrosis, apoptosis, and inflammation in patients with severe heart failure. J Transl Med 2009;7:67. [CrossRef]

- 2022 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association | Stroke n.d. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/STR.0000000000000407 (accessed June 15, 2024).

- Zhong W, Ji Z, Sun C. A Review of Monitoring Methods for Cerebral Blood Oxygen Saturation. Healthcare 2021;9:1104. [CrossRef]

- Scherschinski L, Catapano JS, Karahalios K, Koester SW, Benner D, Winkler EA, et al. Electroencephalography for detection of vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a retrospective analysis and systematic review. Neurosurg Focus 2022;52:E3. [CrossRef]

- Veldeman MM. Diagnosis and treatment of early and delayed cerebral injury after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. maastricht university, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kistka H, Dewan MC, Mocco J. Evidence-Based Cerebral Vasospasm Surveillance. Neurol Res Int 2013;2013:256713. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mufti F, Lander M, Smith B, Morris NA, Nuoman R, Gupta R, et al. Multimodality Monitoring in Neurocritical Care: Decision-Making Utilizing Direct And Indirect Surrogate Markers. J Intensive Care Med 2019;34:449–63. [CrossRef]

- Iyer VN, Mandrekar JN, Danielson RD, Zubkov AY, Elmer JL, Wijdicks EFM. Validity of the FOUR Score Coma Scale in the Medical Intensive Care Unit. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84:694–701.

- Ali A, Abdullah T, Orhan-Sungur M, Orhun G, Aygun E, Aygun E, et al. Transpulmonary thermodilution monitoring–guided hemodynamic management improves cognitive function in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a prospective cohort comparison. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019;161:1317–24. [CrossRef]

- Subba H, Riker RR, Dunn S, Gagnon DJ. Vasopressin-induced hyponatremia in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a case series and literature review. J Pharm Pract 2021:8971900211053497. [CrossRef]

- Wijdicks EFM, Bamlet WR, Maramattom BV, Manno EM, McClelland RL. Validation of a new coma scale: The FOUR score. Ann Neurol 2005;58:585–93. [CrossRef]

- Santos-Teles AG, Ramalho C, Ramos JGR, Passos R da H, Gobatto A, Farias S, et al. Efficacy and safety of milrinone in the treatment of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva 2020;32:592–602. [CrossRef]

- Salvagno M, Geraldini F, Coppalini G, Robba C, Gouvea Bogossian E, Annoni F, et al. The Impact of Inotropes and Vasopressors on Cerebral Oxygenation in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Narrative Review. Brain Sci 2024;14:117. [CrossRef]

- Monnet X, Teboul J-L. Transpulmonary thermodilution: advantages and limits. Crit Care 2017;21:147. [CrossRef]

- Taccone FS, Rynkowski Bittencourt C, Møller K, Lormans P, Quintana-Díaz M, Caricato A, et al. Restrictive vs Liberal Transfusion Strategy in Patients With Acute Brain Injury: The TRAIN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2024. [CrossRef]

- Turgeon AF, Lauzier F. Shifting Balance of the Risk-Benefit of Restrictive Transfusion Strategies in Neurocritically Ill Patients-Is Less Still More? JAMA 2024;332:1615–7. [CrossRef]

- Turgeon AF, Fergusson DA, Clayton L, Patton M-P, Neveu X, Walsh TS, et al. Liberal or Restrictive Transfusion Strategy in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. N Engl J Med 2024;391:722–35. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).