Introduction

Cotton is the choice natural fiber cultivated globally, especially in the tropical and subtropical world regions [

1]. It is a raw material for many industrial and domestic processes and employs nearly 400 million people across its global value chain, worth over

$40 billion [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Cotton competes with other natural (jute, flax, wool, hemp), semi-synthetic (rayon or viscose, lyocell, and cupro), and synthetic (polyester, nylon, acrylic, and spandex) fibers for market share, and thus, must maintain the highest quality possible to sustain its competitive edge [

3]. India, China, and the United States of America are the topmost cotton producers globally, and of these three, the US exports most of its produced cotton to foreign markets, where it gets converted into textiles, fabrics, and other products [

3,

5,

6].

Although every part of the cotton plant is valuable, including its stalk and waste products that have applications in synthetic wood and silver nanoparticle production, respectively, the lint—the fiber obtained from the bolls after extraction of seeds—is the most significant economic cotton product [

3,

7,

8]. Lint quality is determined by length and length uniformity index, micronaire, color, and extraneous matter contents, including plastic [

3,

9,

10]. For many years, US-produced cotton lint has been reputable as one of the cleanest globally, significantly in part because of the strict regulatory guidelines and awareness sensitization programs established to ensure that the US-produced cotton is of high quality [

3,

10,

11,

12]. The quality of cotton produced in the US intended for marketing internationally is statutorily closely monitored and graded by a dedicated USDA classing office [

10,

13].

For many years, US-produced cotton lint has been reputable as one of the cleanest globally, significantly in part because of the strict regulatory guidelines and awareness sensitization programs established to ensure that the US-produced cotton is of high quality [

3,

10,

11,

12]. The US exports two-thirds of its cotton growth, with China buying nearly half of the exported cotton [

14]. The quality of cotton produced in the US intended for marketing internationally is statutorily closely monitored and graded by a dedicated USDA classing office [

10,

13]. Other cotton-producing countries such as Australia, where every lint bale is classed individually by the International Cotton Advisory Committee CSITC Round Trials program, and China, where two agencies, the China Fiber Inspection Bureau (CFIB) and the China Inspection and Quarantine (CIQ) are responsible for domestic cotton grading and establishing stands and inspecting imported cotton, respectively, have adopted similar classing or grading practices [

14,

15,

16].

However, while the US has significantly automated cotton grading or classing using the High Volume Instrument (HVI), and each division of the USDA-Agricultural Marketing Services (AMS) responsible for performing cotton grading ensures a reliable and effective classification system and delivery services, gins still manually collect the grading samples sent to the USDA classing office [

10,

13,

17]. Manual sample collection is tedious for the gin worker(s) who must stand throughout ginning near the conveyor or other mechanisms transporting the baled lint at the gin, is not repeatable, and probably costs more than required when the sample collection process is automated. Thus, the rationale of this study is that automating the USDA lint classing sample collection at commercial cotton gins across the US cotton-producing region is an essential task that would bring convenience, bridge the labor gap, and provide potential significant cost-reduction benefits to the commercial gins that do.

Automation has proven to be amenable to simplifying tedious, repetitive tasks across industries [

18,

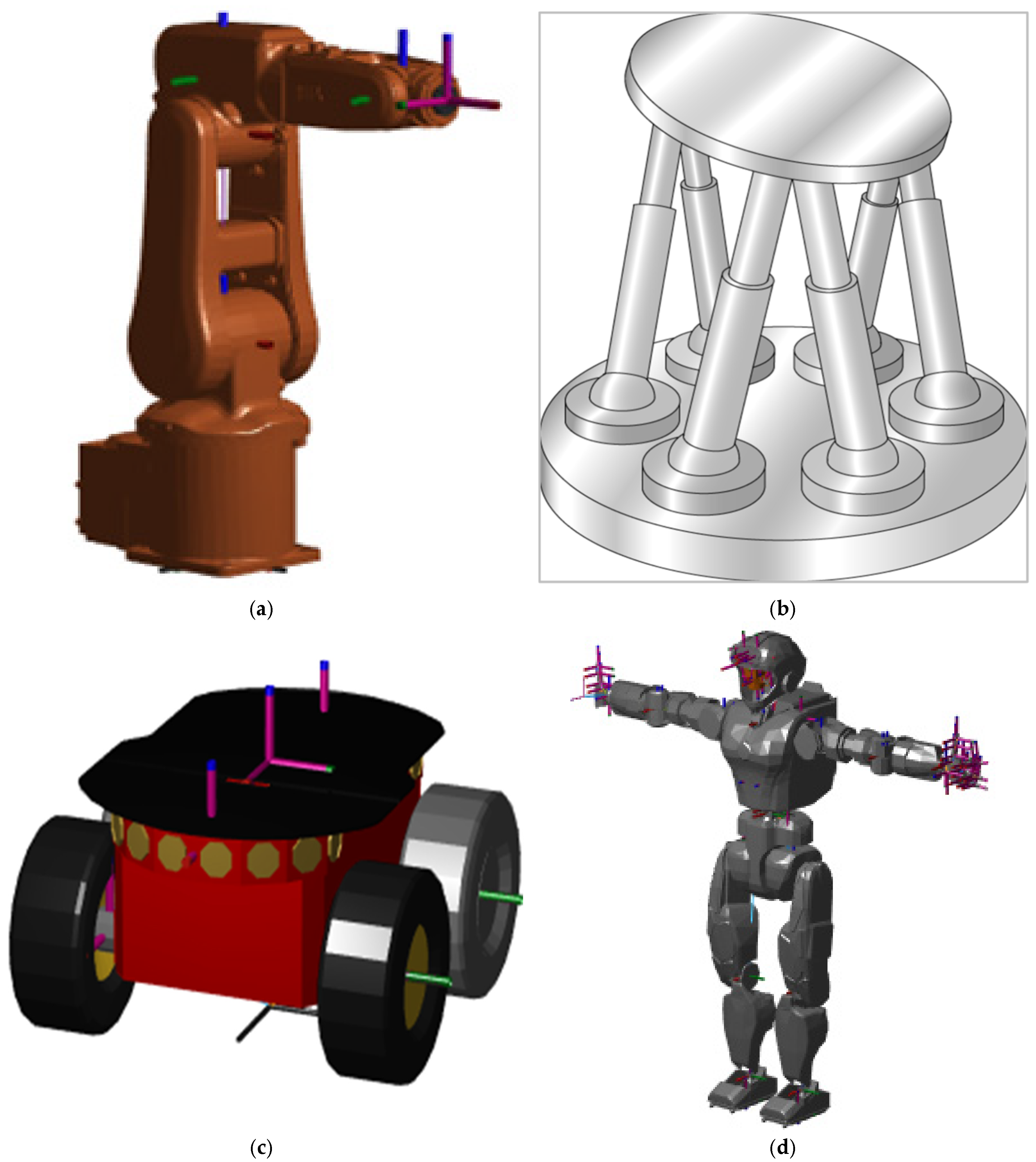

19]. Robots are automation agents of various types (Cartesian, cylindrical, SCARA, Delta, or humanoid) and functionalities (service, medical, pick-and-place, drones, mobile, industrial, and collaboratory robots—cobots) [

20,

21]. They come in different configurations, including serial, where links are concatenated sequentially from the base to the end-effector, or parallel, mainly delta and Stewart mechanism designs, form with multiple links connected at both ends, degrees of freedom (for flexibility and dexterity), and payload capacities, see

Figure 1 [

20,

22]. While the serial manipulators generally have large workspaces and significant versatility suitable for assembling, pick-and-place, and welding tasks, they typically have limited payload capacity and stiffness that results in low precision [

20,

23]. Parallel manipulators are highly rigid and precise, making them amenable to high-precision tasks like machining and part positioning operations. However, Parallel robots generally have smaller workspaces than similar serial manipulators [

20].

This work proposes an adoption framework for low-cost robotic manipulators for automated lint classing sample collection and performs its comprehensive cost-benefit analysis. Justification for the most suitable robot type and specifications are presented based on the known characteristics of commercially available robots, and then a comprehensive comparative cost-benefit analysis between the manual and the proposed automated lint grading sample collection is conducted based on the typical unit costs and known and expected benefits of the compared methods.

2. Robotic Manipulator Adoption for Automated Lint Sample Collection

2.1. Cotton Ginning Process Layout

Cotton ginning primarily entails separating seeds from the fiber of seed cotton harvested by one of two common machine types—the cotton picker and the stripper—or the manual method, which is still prevalent in most parts of the world, especially in developing economies like India, China, Pakistan, and Africa. Modern cotton gins have long evolved to encompass providing other ancillary functions such as cleaning and drying to maximize their efficiency and optimize the quality of lint they produce, thereby maximizing the profit of cotton primary producers. The processed seed cotton type determines the needed equipment sequence in a cotton gin layout. Specifically, the harvesting mode determines the seed cotton quality—while manually harvested seed cotton typically has low extraneous matter content, machine-harvested cotton often has higher extraneous matter, with the picker-harvested seed cotton having lower dirt content than the ones harvested by the non-discriminatory stripper harvester. Regardless of the harvesting method, Upland Cotton (

Gossypium hirsurtum L.) processing gins generally follow a similar equipment layout with only minor variations to accommodate the cleaning requirements of specific harvesting types. Gins press the cleaned, separated fiber into bales of approximately 218–227 kg (480–500 lb.) [

13].

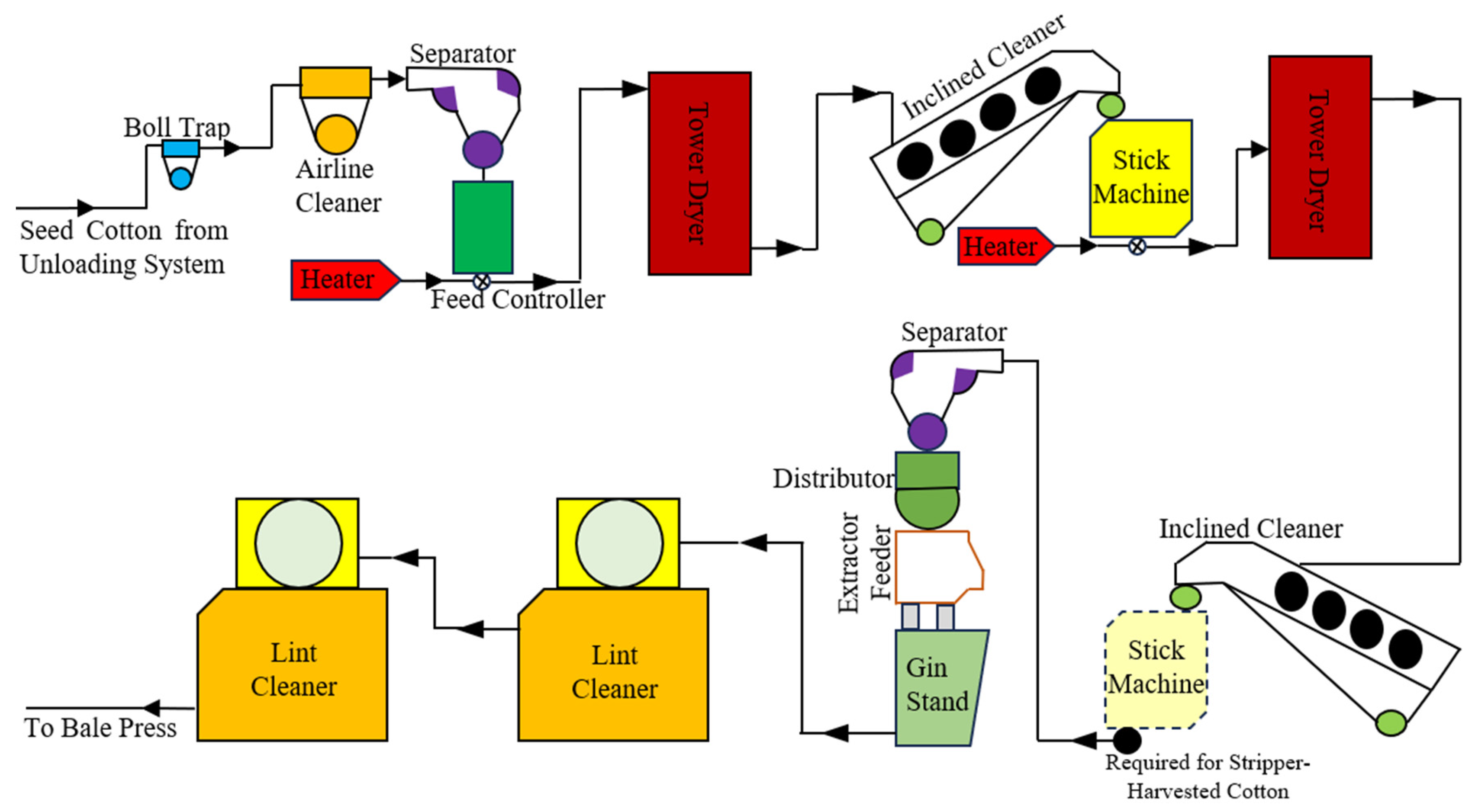

Figure 2 shows a general equipment layout for Upland Cotton processing, starting from the pneumatic- or conveyor belt-type material unloading/module feeder section at the entrance of the process and ending at the lint baling section [

24]. So that gins can maintain their optimal processing capacities, most modern commercial gins use a double-box type hydraulically operated bale press after a series of evolution spanning centuries, as detailed in [

24]. This method ensures a continuous flow of baled lint throughout the ginning process during peak ginning season, and dedicated workers must manually collect two industry regulator classing samples from the front and back sides of each produced bale on a rolling basis, making the sampling tedious and somewhat costly [

17].

Globally, the cotton ginning industry packages bales into four density categories—gin universal, flat bale, modified flat, and gin standard densities—according to the specifications of the bailing press used [

24,

25,

26]. Regardless of the packing density of the bales, which ranges from 0.37–0.45 g/cm

3 [23–28 lb./ft

3], the licensed gin workers require minimal pulling or cutting effort to draw about 115 g [0.25 lb.] of lint samples from either end of each finished bale, representing the first and last cotton exiting the bale press [

10,

17,

24].

2.2. Cotton Lint Classing Sample Collection at Gins

While the most common practice at most commercial gins is cutting lint classing samples with knives or by bare hands after baling the lint at the hydraulic press before bagging, a few gins collect their samples at locations anywhere between the gin stand and the lint battery condenser [

13,

17]. After cutting a total of about 230 g [0.5 lb.] samples from both faces of each produced lint bale and tagging it with a Permanent Bale Identification PBI, which is a 12-digit unique identifier consisting of a five-digit gin code and a seven-digit bale number, the licensed agent delivers the sample to the gin’s locality-serving USDA classing office through a pre-established channel [

10,

13,

17].

The USDA Cotton Program is solely responsible for licensing every participating gin in the lint bale classing program, and requirements for participating in the program include gins not being allowed to tamper with (by trimming or altering in any manner) the collected classification samples that must be prepared tightly rolled into a Cotton Program-supplied sack for immediate shipment after collection [

13,

17].

2.3. Labor Shortage and Costs

Depending on a gin’s size, one or more dedicated workers may be responsible for manually collecting the lint quality grading samples [

13,

17]. Because during the peak season, most gins operate round the clock, downtimes for maintenance calls are inevitable, and designated collectors of lint samples must still be paid during those times, the labor cost for the manual sample collection eats into gin bottom line [

27]. Moreover, apart from the dwindling agricultural production and processing labor supply in developed and developing economies alike that is driving up labor costs, the efficiency of the lint sample collectors is typically sub-optimal since gins must pay them at least a locality-dependent minimum wage even though they must collect lint samples for only a fraction of their working duration.

According to available data from the US Department of Labor (DOL), US gins pay an average of

$ 11.81–14.68 per manual lint sample collector or general gin maintenance worker, running into tens of thousands of dollars per worker per ginning season, and seasonal workers from overseas fill most of the open positions, which involve labor certification procedures and significant immigration costs [

28]. This consideration further justifies the automation needs for the lint sample collection process to minimize the demand for human labor and its associated encumbrances.

2.4. The Proposed Robot Choice for Automating Classing Sample Collection

Considering the above-described procedure, the sample collection task is repetitive and standardized and is thus amenable to automation, which does well in replacing humans in monotonous operations like this one. Because the lint sample size is generally small (less than 0.5 kg in each instance) and the specific sampling location on the faces of the bale is not as important—in fact, the collection of samples must be at random points from the two sides of the bale—the small payload of a typical commercial, low-cost, small-size serial robot, which can exceed 1 kg, is deemed sufficient for the task of lint grading sample collection at most commercial gins. The choice of a serial manipulator is further justified because the costs of alternative robot types, e.g., parallel or humanoid, would outweigh the economic benefits of adopting them for the use case under consideration, especially when the cotton ginning industry already runs on a narrow profit margin.

Serial robots are integratable with color cameras and other optical sensors to detect and localize cotton bales within their workspace and initiate speedy sample collection subsequently, taking advantage of their significant work envelope and reach, which parallel manipulators like delta robots may not conveniently and affordably provide.

2.5. Location of the Robot in the Gin

The multi-planar motion trajectory needed to collect the lint samples and the configuration of the serial robots make them the most suitable for retrofitting at a location just above or beside the gin conveyor belts that transport the freshly pressed lint bales to the final bagging stand. While the sampling robots may preferentially be housed in enclosures for collision avoidance, since there will always be human traffic around them when they are operational, they may be easily programmed for inherent collision avoidance using some external camera or LiDAR sensors mounted on them to monitor their environment and pause their operation whenever they detect an intruding object in their workspace. The collision avoidance technology is quite mature and readily programmable in robot operational algorithms, such as the ladder logic.

2.6. The Proposed Integration Framework for Robotic Lint Grading Sample Collection

Integrating a classing lint sample collection serial robot into the cotton processing process flow requires adequate consideration for space availability around the lint-bale conveyor belt after the bale press, naturally around the standing location of current human sample collectors. Depending on the conveyor configuration and type, the robot may be retrofitted on or beside it. For new gins adopting an automated sampling technology, the designers must suitably plan in the robotic sample collector’s best location to optimize space utilization and operational safety.

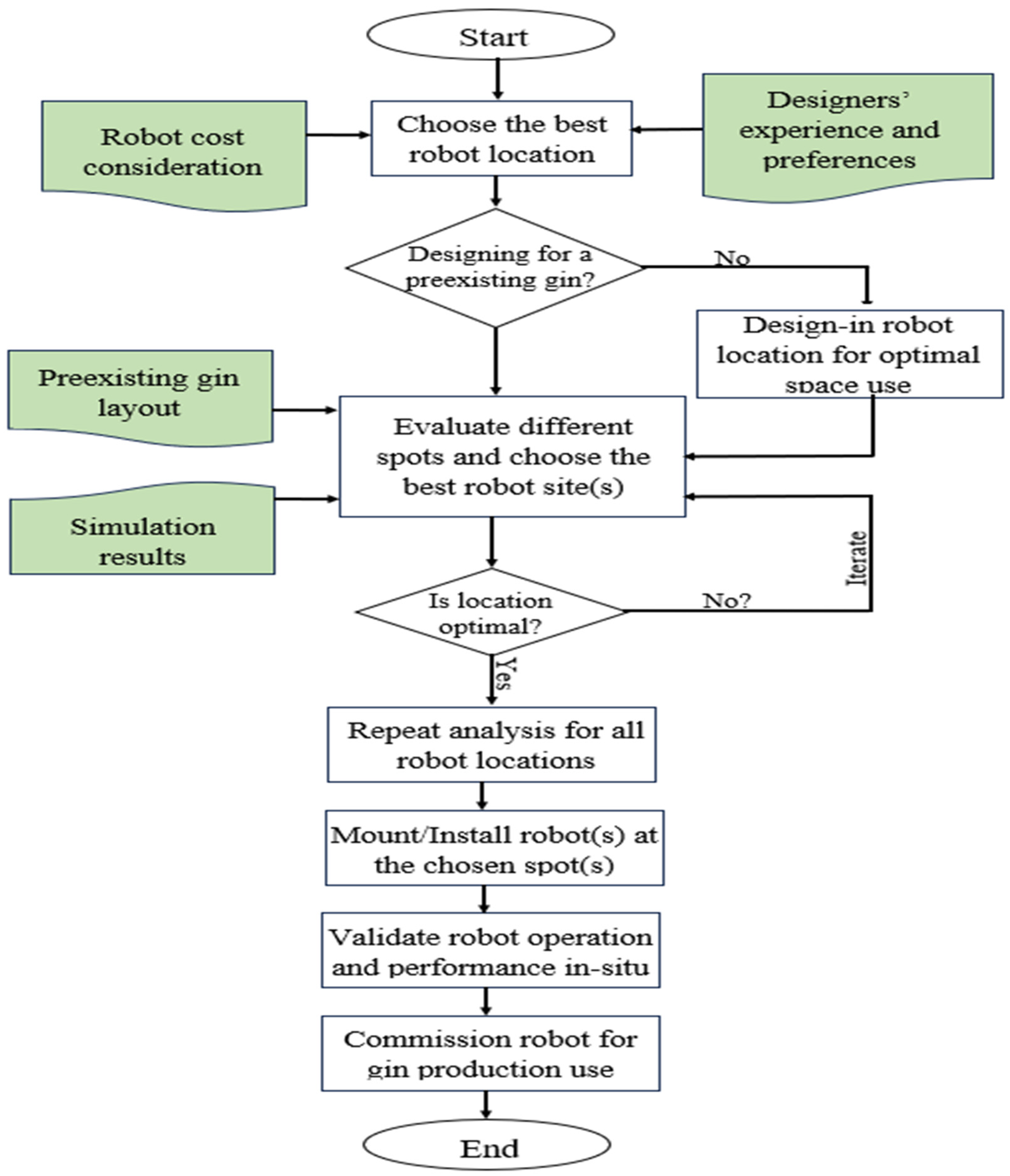

The proposed adoption framework flowchart is presented in

Figure 3. First, a suitable low-cost commercial robot is selected based on its charateristics, the designer’s experience and preference, and costs cosideration.Then the mounting location of the robot in the cotton gin is chosen for optimal space utilization and operational safety, an enclosure may be used for the robot if deemed necessary. Simulation studies may be performed to visualize the robot’s operation in the commercial gin in a virtual environment, ensuring the robot’s workspace does not envelope any physical obstacles. This design process is repeated for each of the bale press line to be automated, depending on gin’s size.

After the simulation studies are validated, the robot and other necessary identified installation hardware are purchased. The designed robots and possible enclosures are mounted at the chosen spots, according to the simulation studies. In-situ experimentation and validation of the robots’ motion trajectories are performed to ensure no collision issues. After satisfactory validation tests, the robots are commissioned for production use.

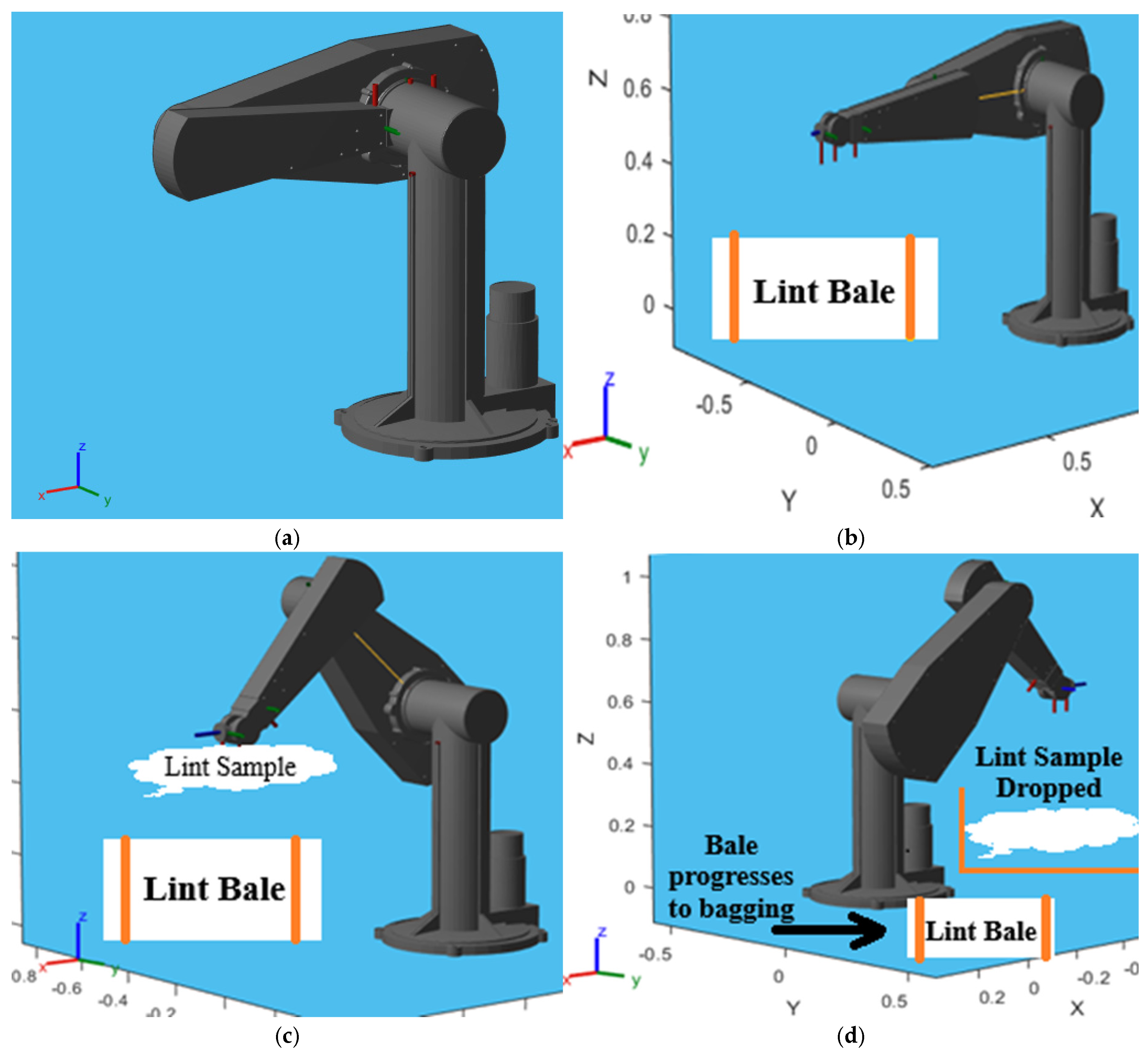

Figure 4 presents an example MATLAB/Simulink simulation study results for a six-DOF PUMA serial robot performing the lint sample collection. In

Figure 4a, the robot is shown in its home position, representing a scenario when no lint bale is in its workspace. After a lint bale comes within its workspace, as detected by a sensor-based machine learning algorithm, the robot outstretches its arm and picks up some lint samples, as depicted in

Figures 4b,c. Finally, the robot rotates according to its required

inverse kinematics to align with the sample collection container, which has the appropriate integral sample PBI labeling mechanism—

Figure 4d—and then returns to its home position to begin another sample collection cycle.

4. Summary and Recommendation

4.1. Summary

Although cotton gins operate on strict profit margins currently, which makes significant capital investments cost-prohibitive for most commercial gins, the increasing trend of manual labor shortages has highlighted the urgent need for alternative solutions to certain ginning processes. The reliance on seasonal workers, with associated costs such as retraining and immigration fees, has become increasingly unsustainable.

One crucial step still widely performed manually in all commercial gins is lint grading sample collection. In this process, trained workers collect samples for delivery to regulatory agencies for official grading. Automating this process is imperative to reduce labor dependence, enhance sustainability, and improve quality and profitability in cotton production and processing.

This work proposes a framework for adopting robotic agents as an alternative to human lint sample collectors. A six-degree-of-freedom serial robot is the optimal choice due to its affordability and versatility. The proposed method demonstrated through software simulations indicates that despite a significant initial capital requirement, the robotic solution offers a short payback period of one to two years. Comparative analysis reveals that robotic lint sample collection is cost-effective, repeatable, and accuracy-enhancing, ensuring compliance with regulatory standards.

Adopting robots for lint grading sample collection is expected to alleviate the challenges of scarce manual labor while delivering consistent and programmable results that align with modern industry needs

4.2. Recommendations

Based on this study, the author posits that for commercial cotton gins aiming to enhance automation, improve lint grading efficiency, and maintain compliance with USDA or other regulatory standards, adopting a low-cost serial robot is a sustainable and cost-effective solution in the long term. Despite the significant initial investment, the automation benefits—including increased speed, enhanced accuracy, and reduced labor costs—make it the superior choice for scaling operations.

Existing gins are encouraged to explore the framework proposed in this study to integrate automated lint sample collection into their processes, minimizing reliance on seasonal labor. Additionally, designers of new gins are strongly advised to incorporate robotic lint sample collection into their layouts to maximize operational efficiency and long-term profitability for ginners.