Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

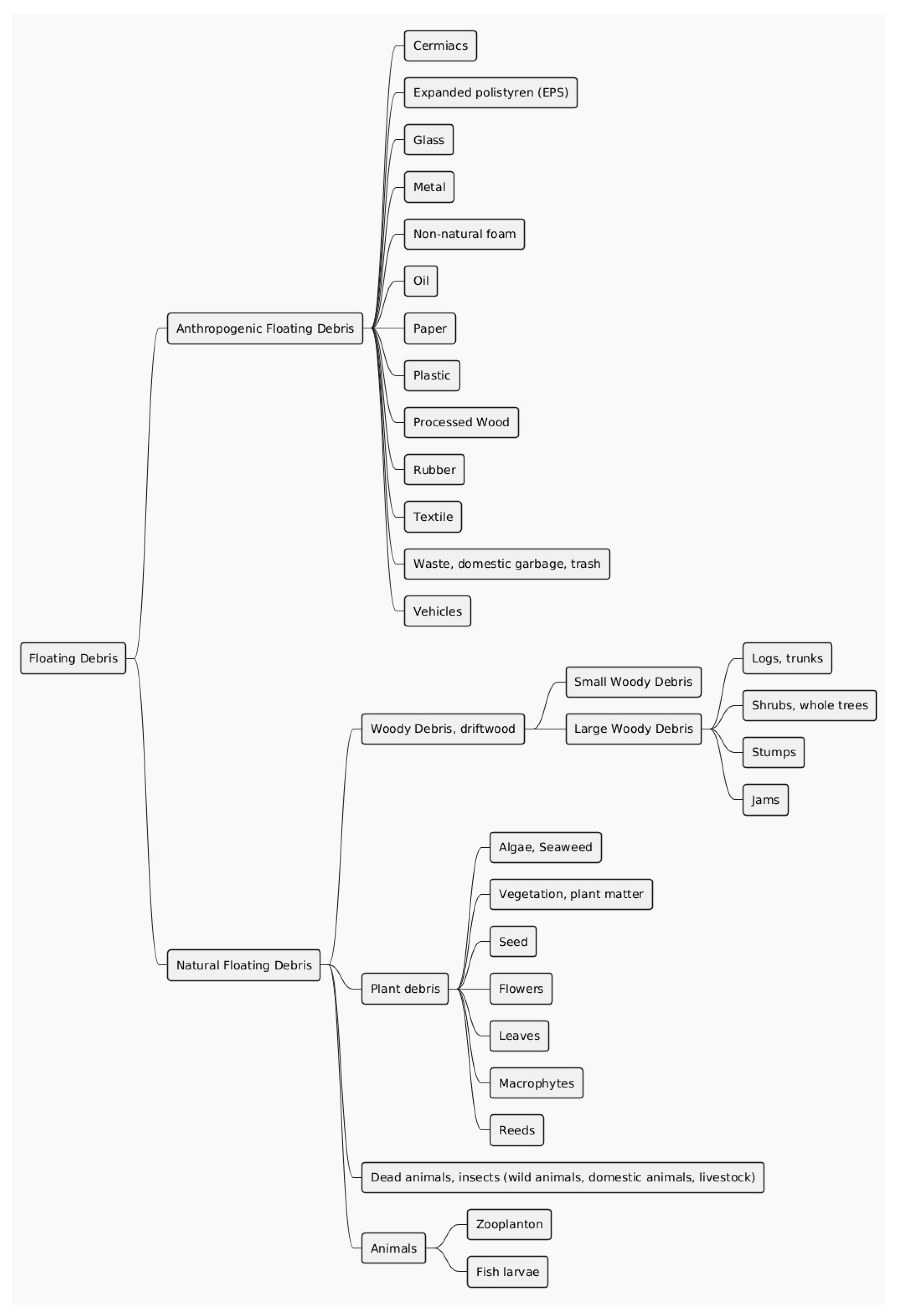

Floating debris (FD), encompassing both woody and anthropogenic materials, disrupts fishway hydraulics and ecological efficiency. Despite frequent usage in scientific literature, the term remains ambiguous. Motivated by the need to enhance fishway performance, this study examines the concept of FD. A substantial review of environmental, economic, and safety impacts was conducted, focusing on marine debris, microplastics, and woody debris. Additionally, a systematic analysis of 560 articles published from 2018 to 2023 assessed how FD is described across diverse contexts. Through an elimination process, 55 papers underwent detailed manual analysis. FD was categorized into natural floating debris (NFD) and anthropogenic floating debris (AFD), a distinction crucial for engineering and scientific applications. This classification supports fishway management by facilitating the identification and monitoring of debris accumulation, thus enabling strategies to mitigate hydraulic and ecological consequences. While FD poses risks such as habitat disruption and pollutant bioaccumulation, natural FD also provides potential ecological benefits, including habitat creation. To address these challenges, the study advocates innovative waste management strategies informed by concepts like the doughnut economy and ecological economics. These approaches aim to reconcile ecological sustainability with economic activities, reducing anthropogenic FD while leveraging the advantages of NFD.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Floating Debris

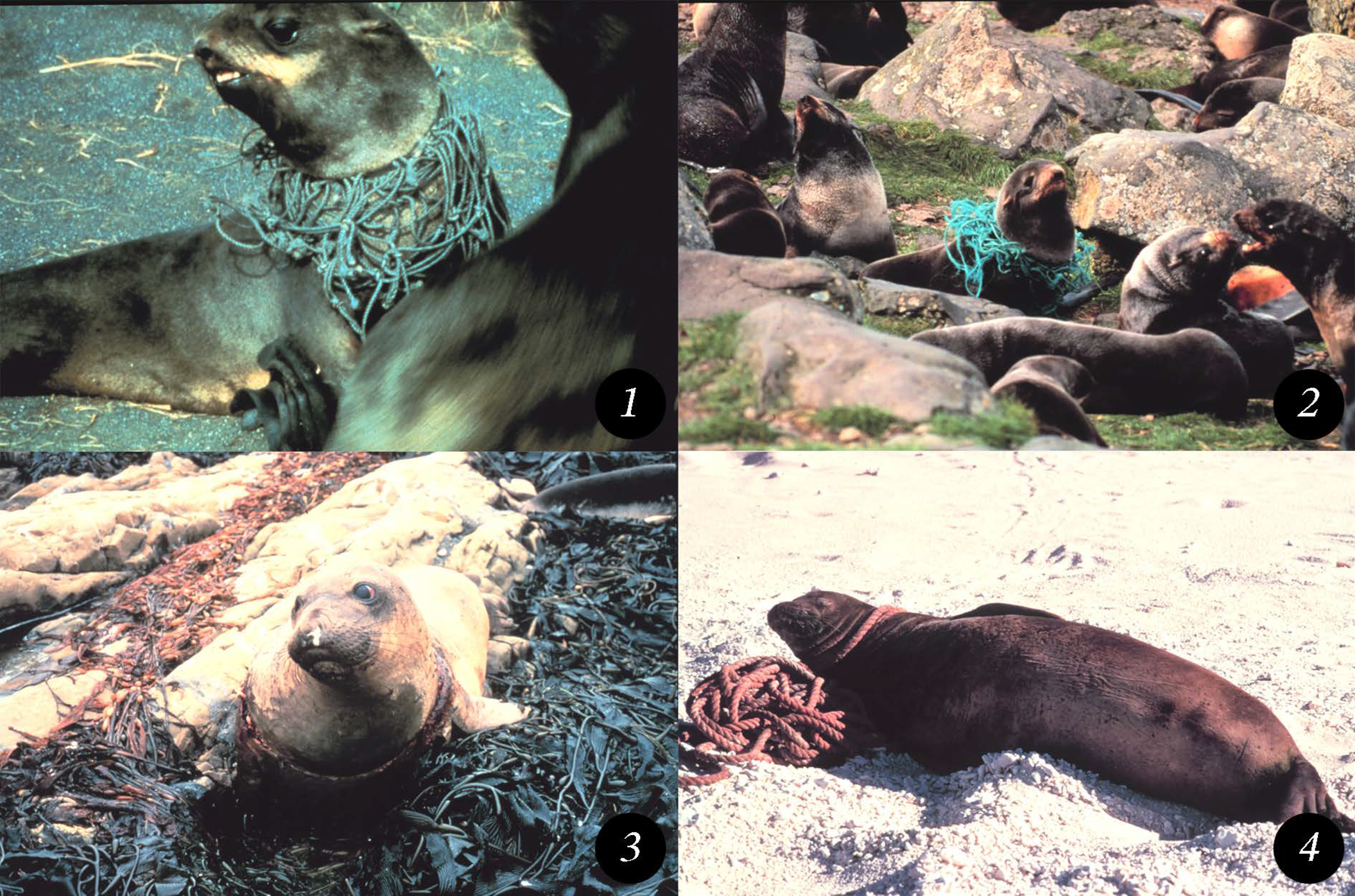

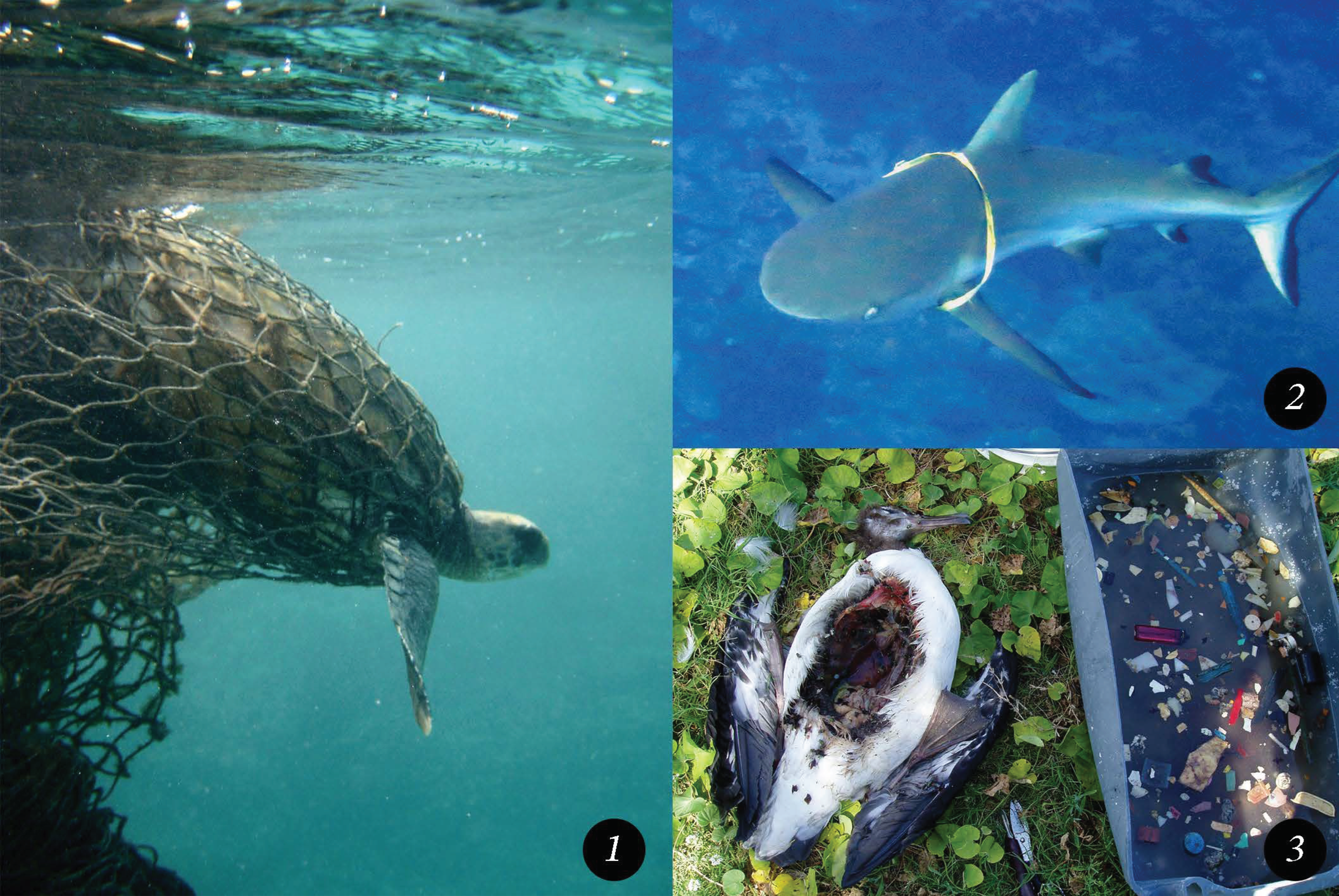

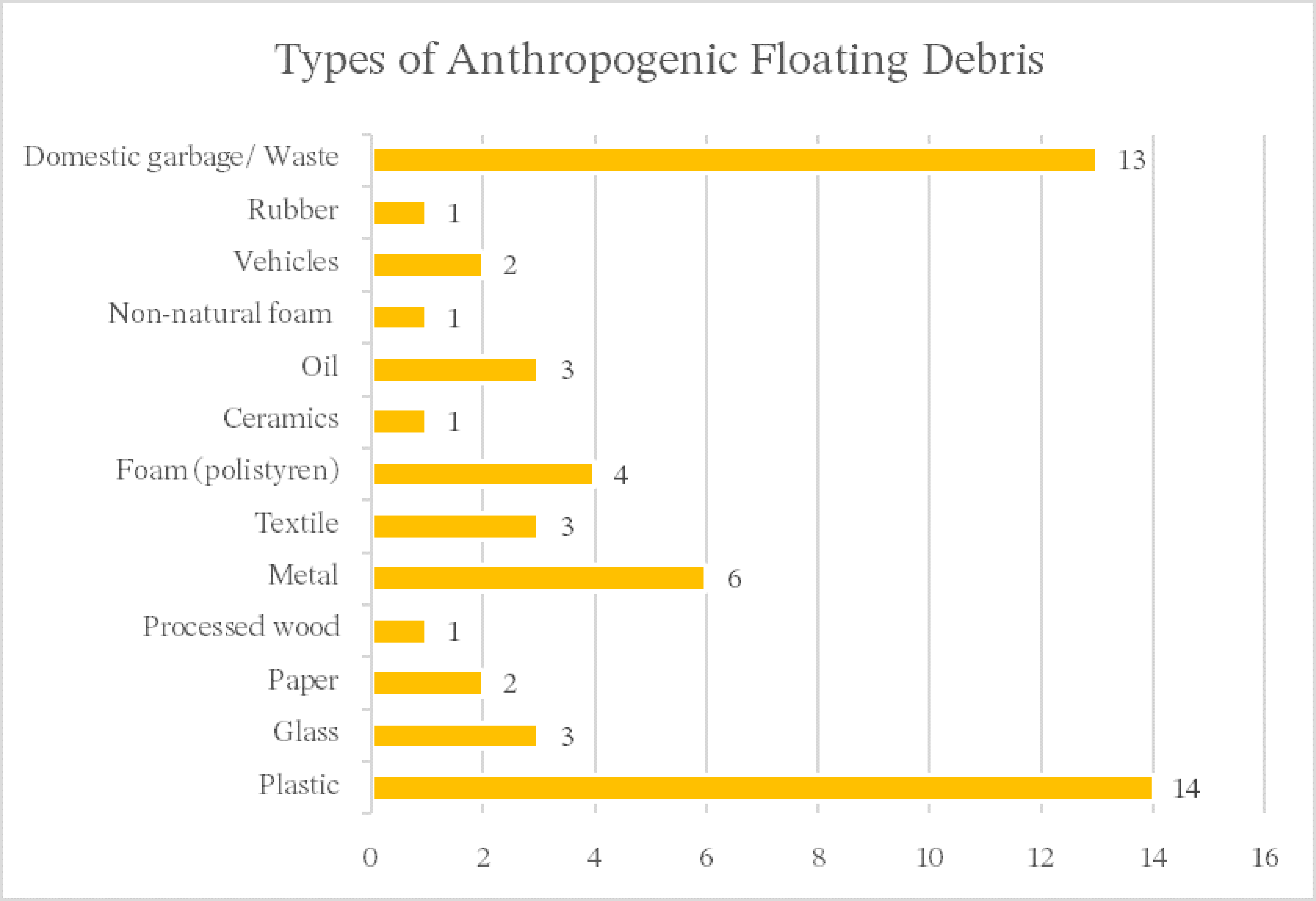

2.2. Anthropogenic Floating Debris

2.2.1. Plastic

2.2.1.1. Microplastic

- Criterion 1 – Chemical Composition: This is the most fundamental criterion for defining plastic waste and other polymers. To illustrate the definitional challenges, consider the ISO definition of plastic, which excludes certain elastomers (e.g., rubber) from this definition.

- Criterion 2 – Solid State: Polymers can exist in various consistencies, such as semi-solid, liquid, or waxy. According to the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS), a solid substance is one that does not meet the definition of a liquid or gas. Most polymers have low vapor pressure and a specific melting temperature, which qualifies them as solids.

- Criterion 3 – Solubility: Another important aspect is the solubility of the polymer. Most conventional polymers are poorly soluble in water, but some synthetic polymers dissolve easily (e.g., PVA or polyethylene glycol with low molecular weight). Researchers propose using the REACH guidelines developed by ECHA, according to which a substance with a solubility of less than 1 mg/L at 20°C is considered poorly soluble.

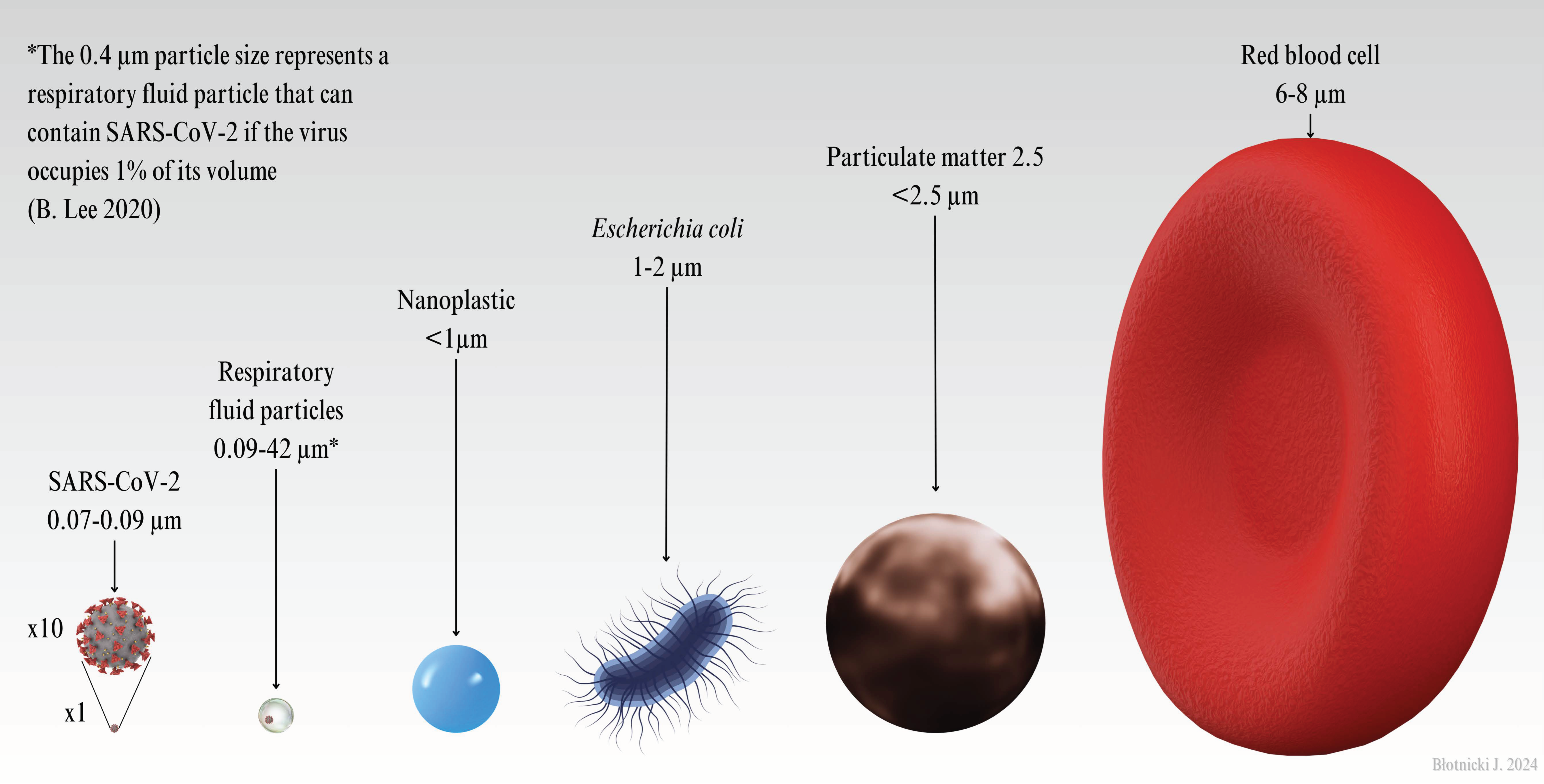

- Criterion 4 – Size: Size is the most commonly used criterion for categorizing plastic waste, with size classes typically corresponding to the nomenclature of nano-, micro-, meso-, and macroplastics. The size of a particle has ecological significance because it affects interactions with living organisms and its fate in the environment.

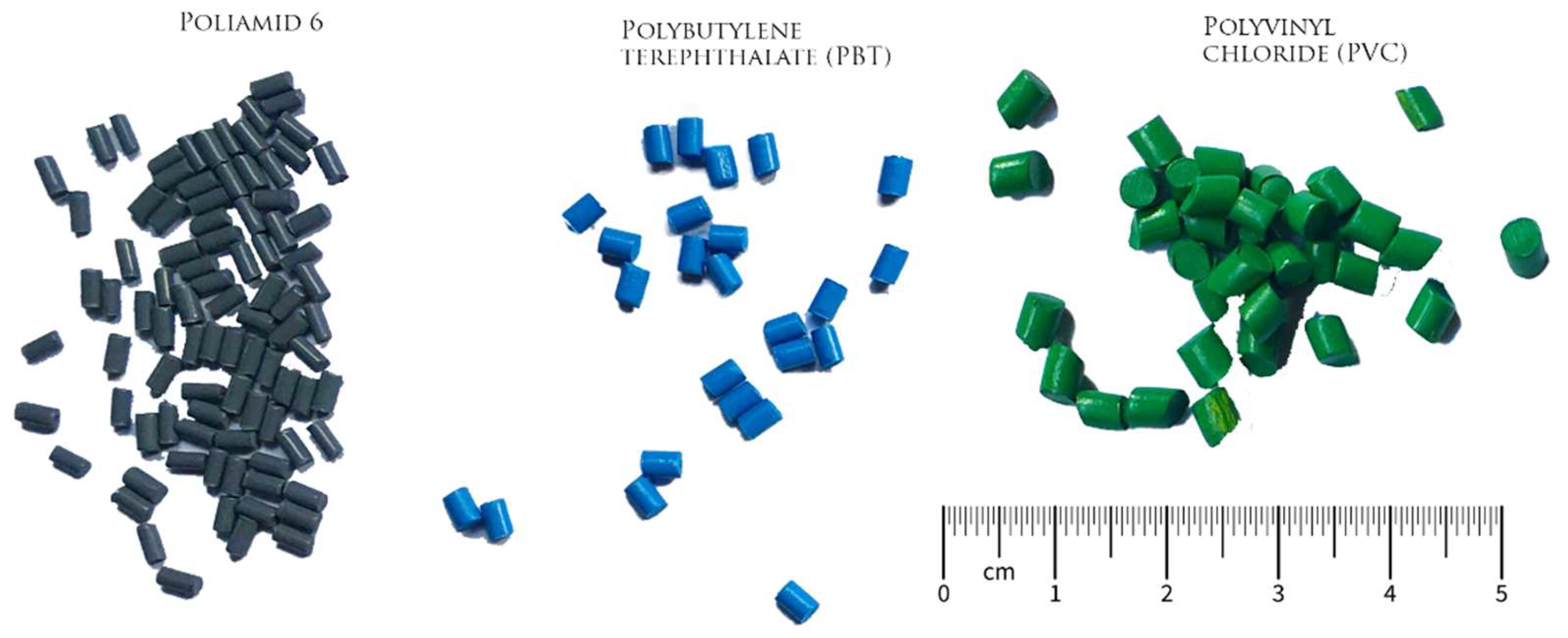

- Criterion 5 – Shape and Structure: In addition to size, plastic waste is often categorized based on shape, structure, and colour. Common shape descriptors include spheres, pellets, foams, fibres, fragments, films, and flakes. Depending on the location of the studies, different shapes are detected in varying proportions. For example, in studies conducted by Mangarengi et al. [115] the most common form of microplastic were fibres, likely sourced from the textile industry along the river.

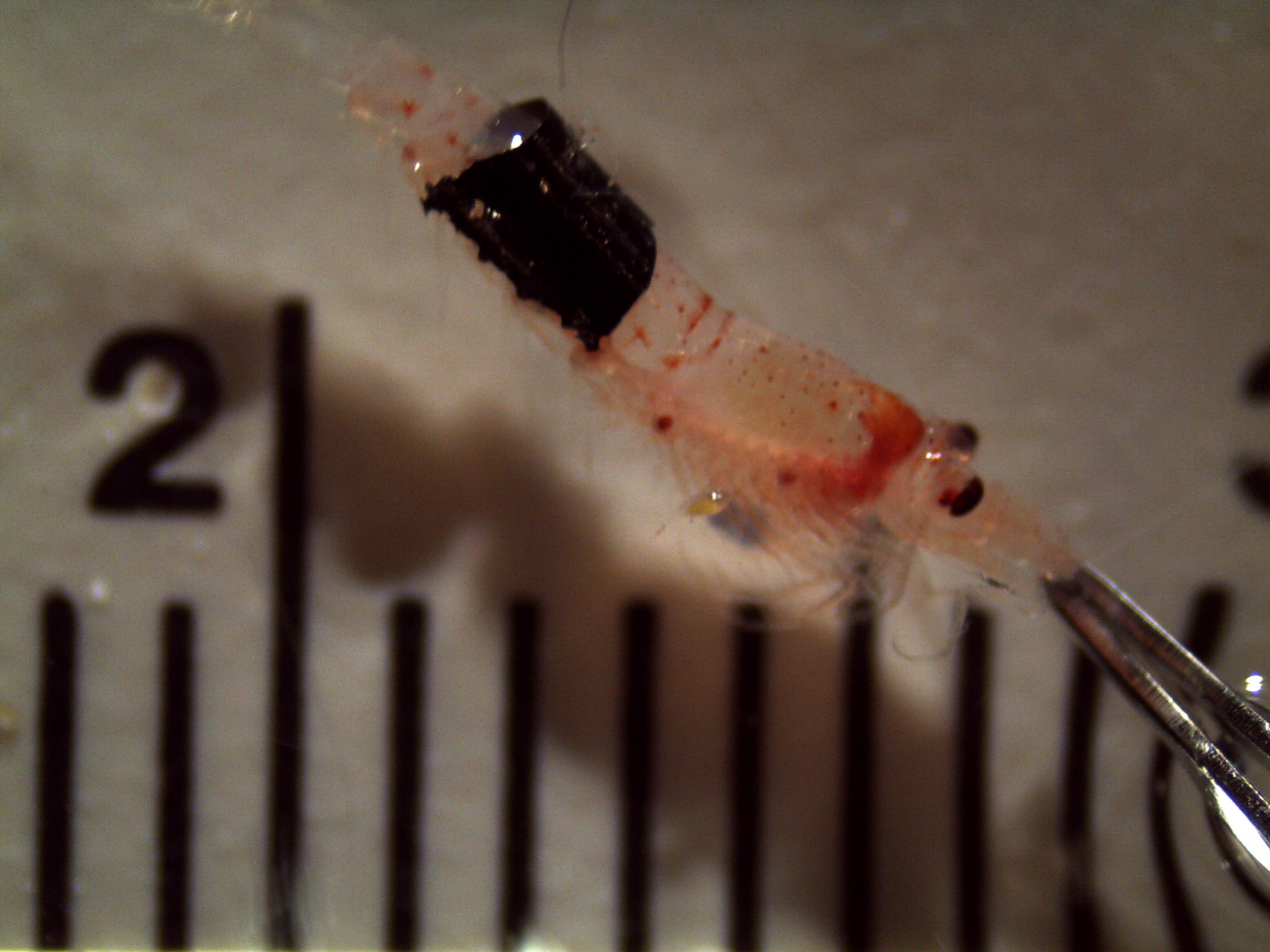

- Criterion 6 – Colour: Categorizing plastic waste by colour is useful for identifying potential sources and contaminants during sample preparation. The colour of an object does not always easily indicate its origin, but it can be helpful in a biological context, such as in the feeding preferences of organisms. Studies indicate that the most commonly encountered colours of plastics ingested by aquatic organisms are blue and black, followed by transparent and semi-transparent plastics [116].

- Criterion 7 – Origin: The origin of plastic waste is often used as a classifier, particularly for microplastics, which are categorized as “primary” and “secondary.” “Primary” microplastics are those intentionally produced at this size (see: Figure 6), while “secondary” microplastics result from fragmentation in the environment [117].

2.2.1.1. Nanoplastic

2.2.2. Marine Debris

2.2.3. Tsunami Floating Debris

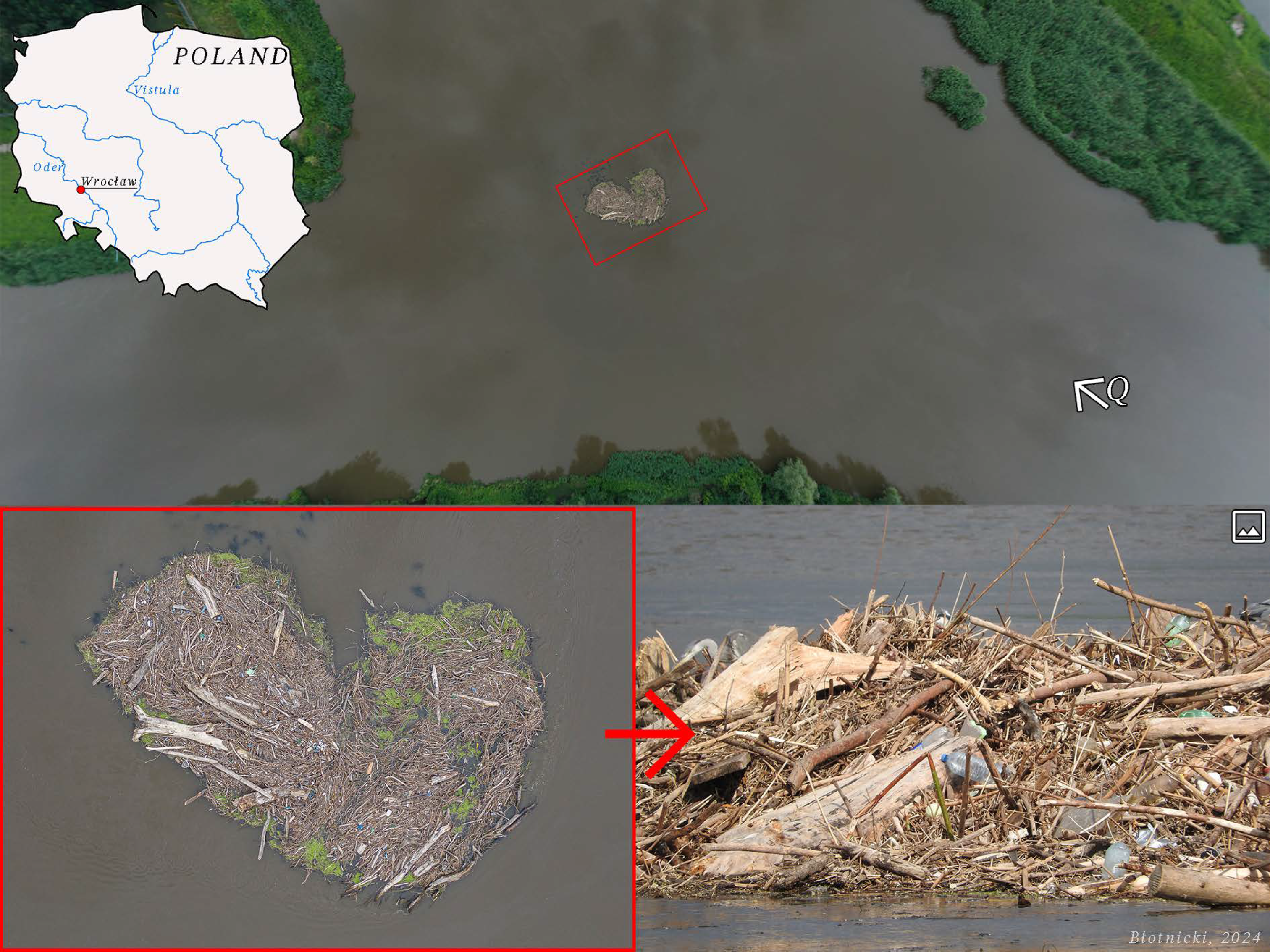

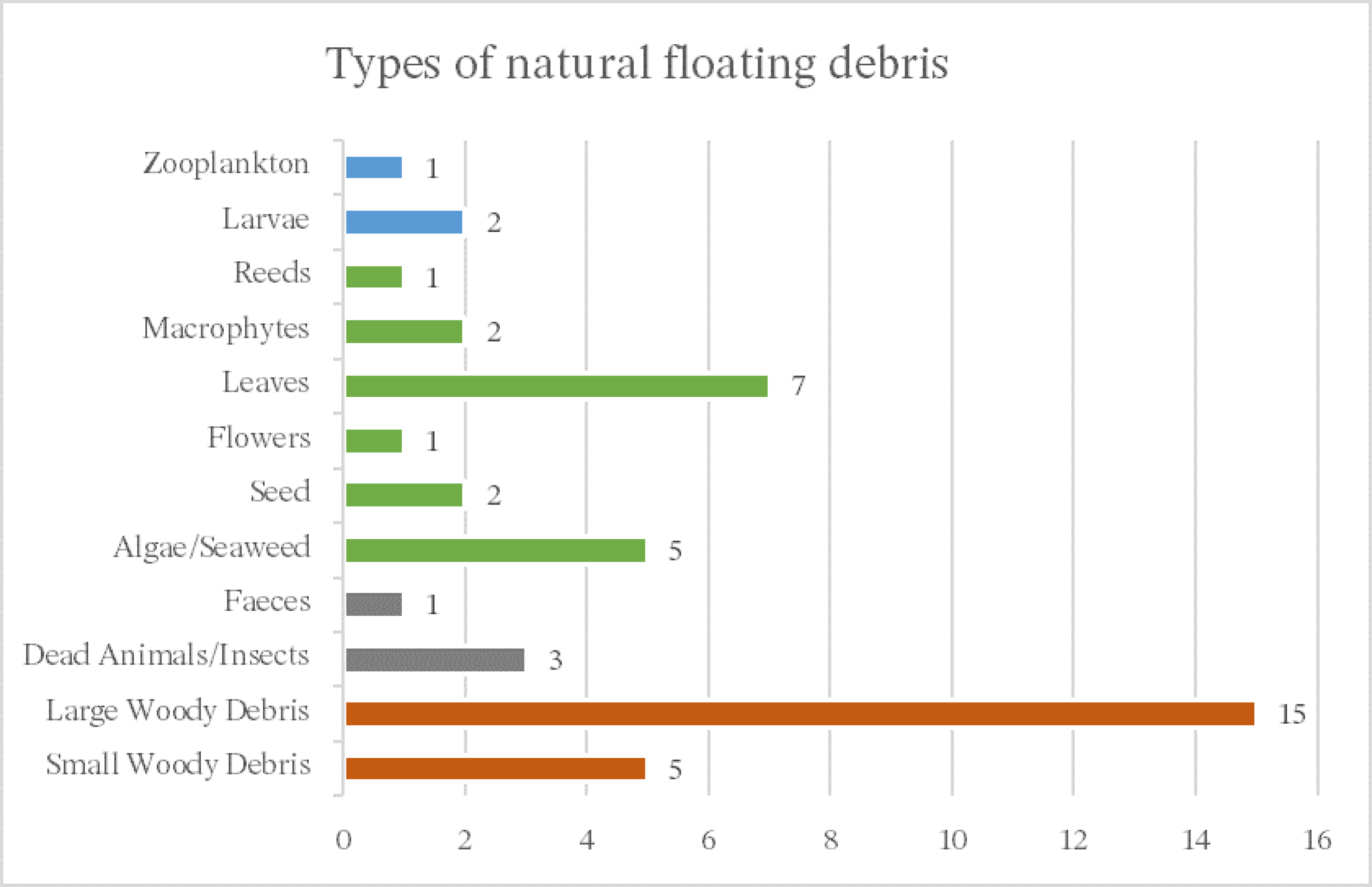

2.3. Natural Floating Debris

2.3.1. Woody Debris

2.4. Methods of Identifying Floating Debris

2.4. Methods of Identifying Floating Debris

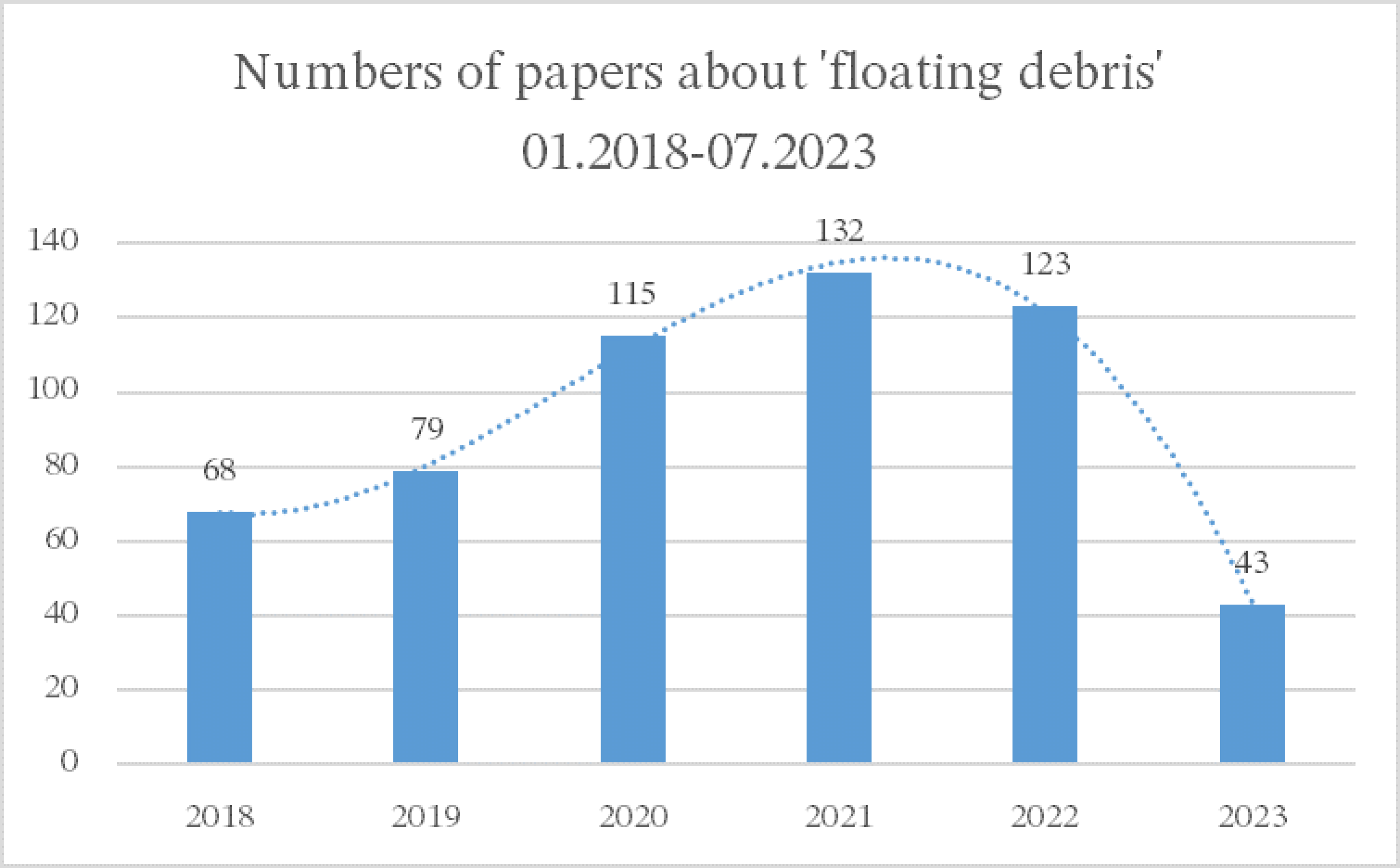

3. Methods

4. Results

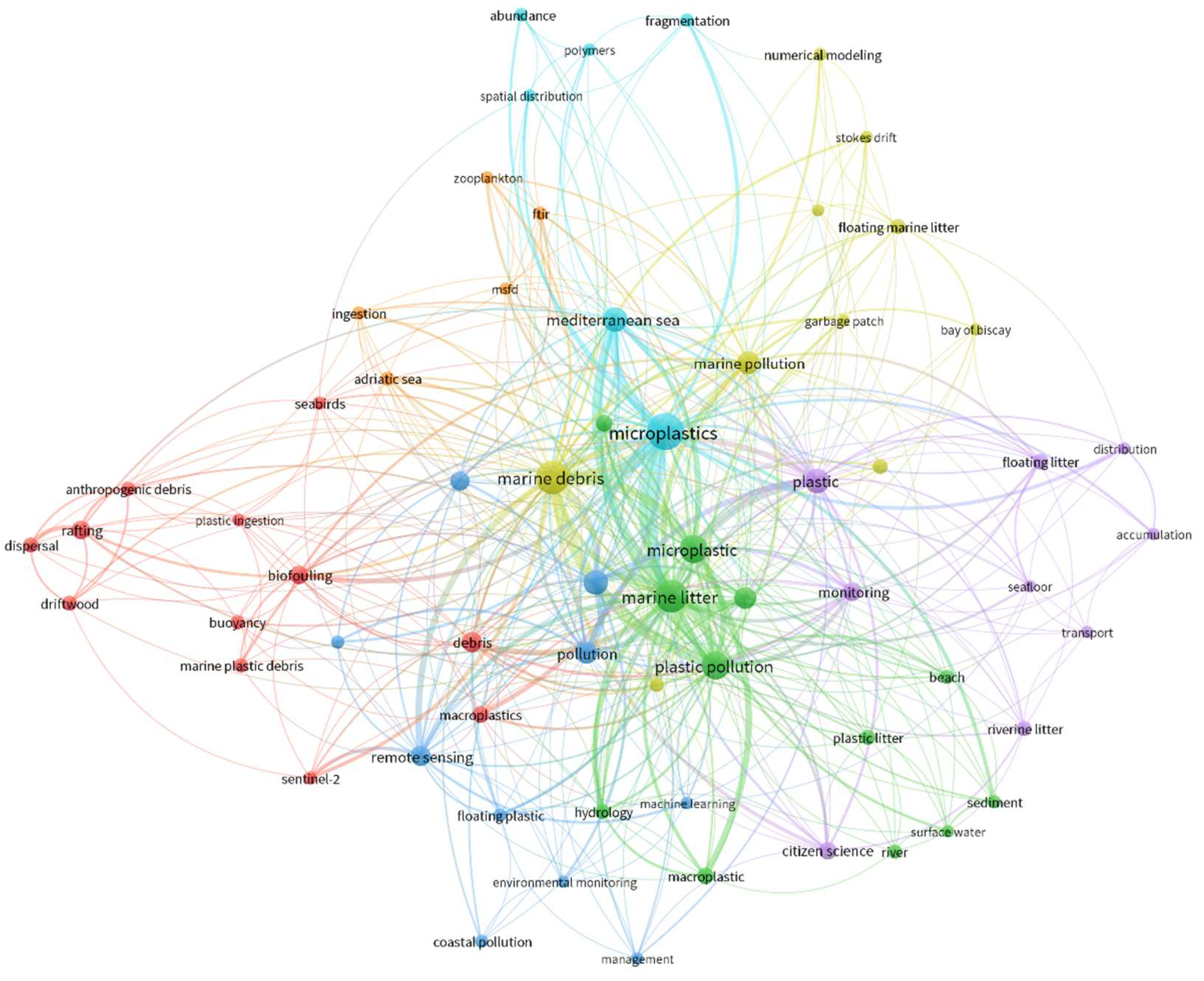

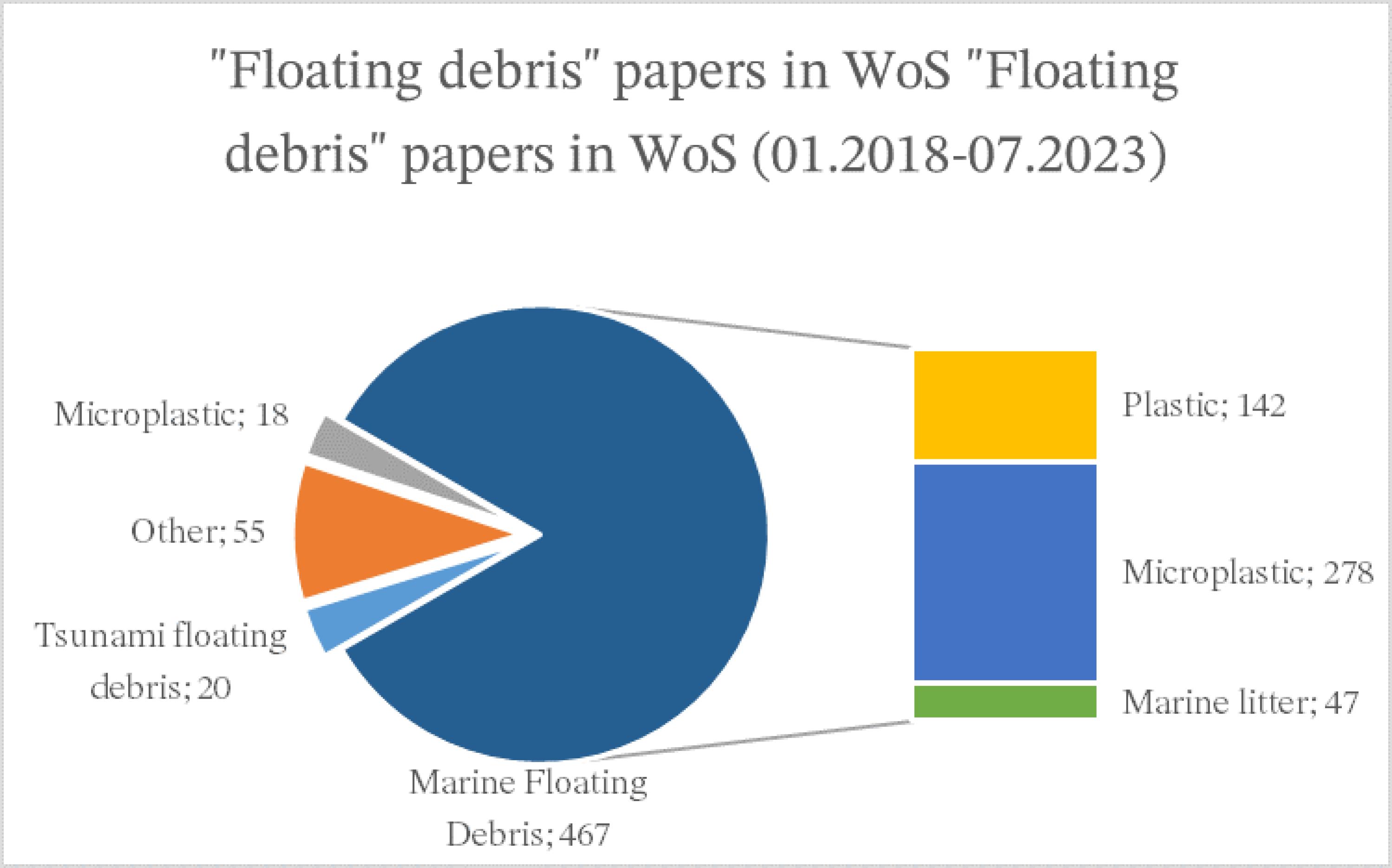

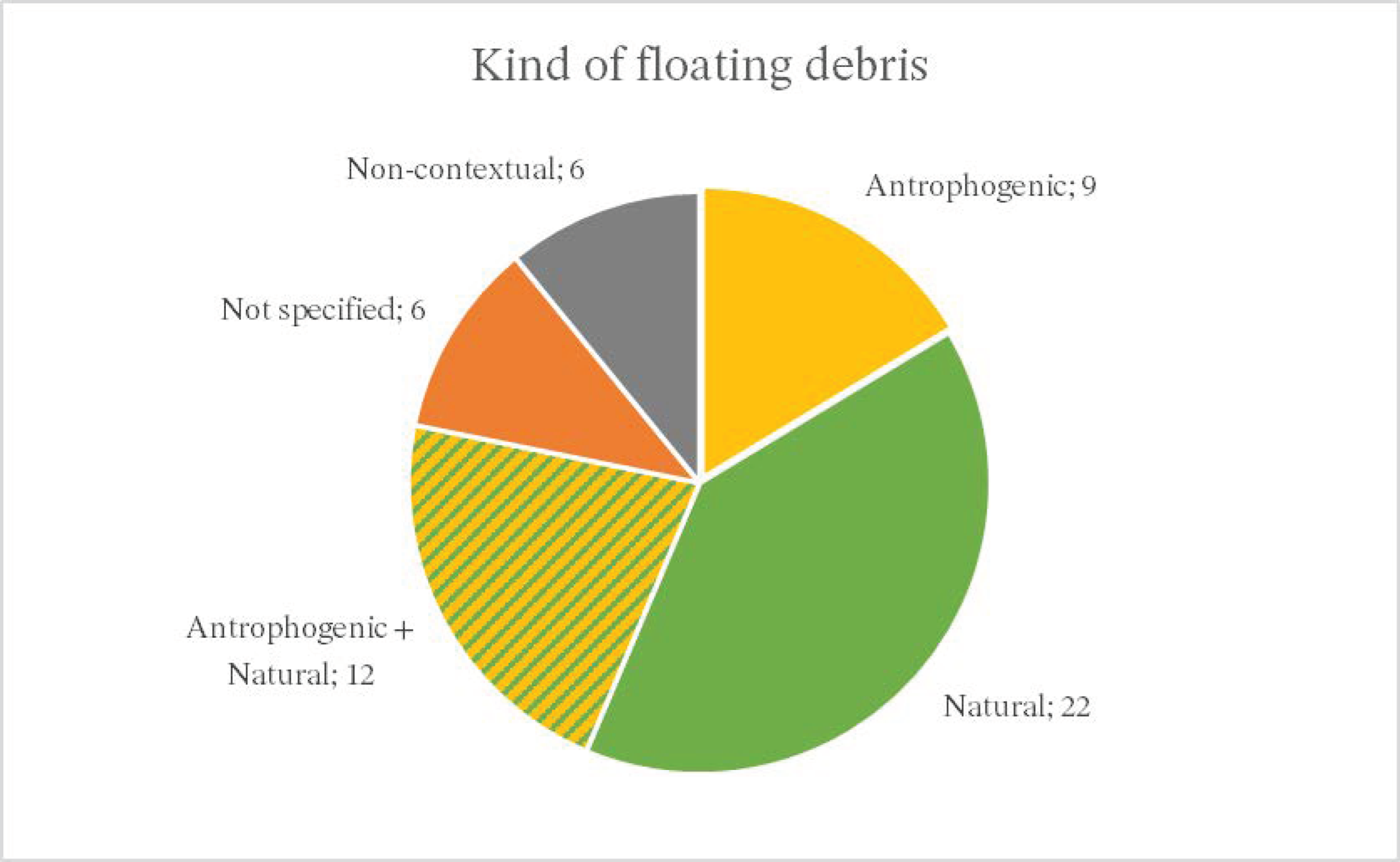

4.1. General Results

4.2. The “Other” Category

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFD | Anthropogenic Floating Debris |

| AMD | Anthropogenic Marine Debris |

| AOP | Adverse Outcome Pathway |

| EGM | Entropy Generation Minimization |

| FD | Floating Debris |

| FDI | Floating Debris Index |

| GC | Gas Chromatography |

| GC-MS | Combined With A Mass Detector |

| GPGP | Great Pacific Garbage Patch |

| GSSP | Global Boundary Stratotype Section And Point |

| HTL | Hydrothermal Liquefaction |

| LWD | Large Woody Debris |

| MARPOL | International Convention For The Prevention Of Pollution From Ships |

| MP | Microplastic |

| NFD | Natural Floating Debris |

| NMD | Natural Marine Debris |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| NP | Nanoplastic |

| TFD | Tsunami Floating Debris |

| UNEP | United Nations Environmental Program |

| YOLO | You Only Look Ones |

References

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C.N.; Ivar do Sul, J.A.; Corcoran, P.L.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cearreta, A.; Edgeworth, M.; Gałuszka, A.; Jeandel, C.; Leinfelder, R.; et al. The Geological Cycle of Plastics and Their Use as a Stratigraphic Indicator of the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 2016, 13, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P.J.; Stoermer, E.F. The “Anthropocene”, Glob. Chang. Newsl. 2000, 41, 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Crutzen, P.J. Geology of Mankind - Crutzen - Nature. Nature 2002, 415, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Waters, C.N.; Williams, M.; Barnosky, A.D.; Cearreta, A.; Crutzen, P.; Ellis, E.; Ellis, M.A.; Fairchild, I.J.; Grinevald, J.; et al. When Did the Anthropocene Begin? A Mid-Twentieth Century Boundary Level Is Stratigraphically Optimal. Quat. Int. 2015, 383, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalasiewicz, J.; Williams, M.; Smith, A.; Barry, T.L.; Coe, A.L.; Bown, P.R.; Brenchley, P.; Cantrill, D.; Gale, A.; Gibbard, P.; et al. Are We Now Living in the Anthropocene? GSA Today 2008, 18, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhacham, E.; Ben-Uri, L.; Grozovski, J.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Milo, R. Global Human-Made Mass Exceeds All Living Biomass. Nature 2020, 588, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, E. The Occurrence of Idotea Metallica Bosc in British Waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 1957, 36, 599–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G.; Aliani, S. Floating Debris in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 86, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira Dantas Filho, J.; Perez Pedroti, V.; Temponi Santos, B.L.; de Lima Pinheiro, M.M.; Bezerra de Mira, Á.; Carlos da Silva, F.; Soares e Silva, E.C.; Cavali, J.; Cecilia Guedes, E.A.; de Vargas Schons, S. First Evidence of Microplastics in Freshwater from Fish Farms in Rondônia State, Brazil. Heliyon 2023, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.; Węsławski, J.M. Typical and Anomalous Pathways of Surface-Floating Material in the Northern North Atlantic and Arctic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, D. Camera Sensor-Based Contamination Detection for Water Environment Monitoring. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 2722–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenal, M.; Patel, K.; Patil, A. Cleaning of Water Bodies Using Coastal Sea Bin (CSB). MethodsX 2021, 8, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryukhan, F.; Vinogradov, A. Estimate of Throughput of Bridge Transitions and Pipe Passages Built on Minor Rivers of Piedmont Areas of Krasnodar Territory-Russia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 162, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First Evidence of Microplastics in Human Placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piyawardhana, N.; Weerathunga, V.; Chen, H.S.; Guo, L.; Huang, P.J.; Ranatunga, R.R.M.K.P.; Hung, C.C. Occurrence of Microplastics in Commercial Marine Dried Fish in Asian Countries. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanhai, L.D.K.; Johansson, C.; Frias, J.P.G.L.; Gardfeldt, K.; Thompson, R.C.; O’Connor, I. Deep Sea Sediments of the Arctic Central Basin: A Potential Sink for Microplastics. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2019, 145, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węsławski, J.M.; Urbański, J.A. Forty Years of Warming: Environmental Change in Marine Coastal Habitats on Svalbard between 1981 and 2022. Polish Polar Res. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.; Mützel, S.; Primpke, S.; Tekman, M.B.; Trachsel, J.; Gerdts, G. White and Wonderful? Microplastics Prevail in Snow from the Alps to the Arctic. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacerda, A.L. d. F.; Rodrigues, L. dos S.; van Sebille, E.; Rodrigues, F.L.; Ribeiro, L.; Secchi, E.R.; Kessler, F.; Proietti, M.C. Plastics in Sea Surface Waters around the Antarctic Peninsula. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.G. A Brief History of Marine Litter Research. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-16509-7. [Google Scholar]

- Galgani, F.; Hanke, G.; Maes, T. Global Distribution, Composition and Abundance of Marine Litter. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; ISBN 9783319165103. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D.K.A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R.C.; Barlaz, M. Accumulation and Fragmentation of Plastic Debris in Global Environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1985–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardianti, A.; Mutsuda, H.; Kawawaki, K.; Doi, Y. Fluid Structure Interactions between Floating Debris and Tsunami Shelter with Elastic Mooring Caused by Run-up Tsunami. Coast. Eng. 2018, 137, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.; Santos, L.; Lu, Q.; Malla, R.; Ravishanker, N.; Zhang, W. Probabilistic Risk Assessment Framework for Predicting Large Woody Debris Accumulations and Scour near Bridges. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliara, S.; Carnacina, I. Influence of Large Woody Debris on Sediment Scour at Bridge Piers. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2011, 26, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, E.; Cunningham, L.S.; Rogers, B.D. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Floating Large Woody Debris Impact on a Masonry Arch Bridge. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, P.N.; Paris, E.; Solari, L.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V. Bridge Pier Shape Influence on Wood Accumulation: Outcomes from Flume Experiments and Numerical Modelling. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2020, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, T.H. Potential Drift Accumulation at Bridges. US Dep. Transp. Fed. Highw. Adm. Res. Dev. Turner-Fairbank Highw. Res. Cent. 1997, 1–45.

- De Cicco, P.N.; Paris, E.; Solari, L. Wood Accumulation at Bridges: Laboratory Experiments on the Effect of Pier Shape. River Flow - Proc. Int. Conf. Fluv. Hydraul. RIVER FLOW 2016 2016, 2341–2345. [CrossRef]

- Lagasse, P.F.; Clopper, P.E.; Zevenbergen, L.W.; Spitz, W.J.; Girard, L.G. Effects of Debris on Bridge Pier Scour; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-309-11834-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kubrak, J.; Nachlik, E. Hydrauliczne Podstawy Obliczania Przepustowości Koryt Rzecznych; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Bladé Castellet, E.; Díez-Herrero, A.; Bodoque, J.M.; Sánchez-Juny, M. Two-Dimensional Modelling of Large Wood Transport during Flash Floods. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2014, 39, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Wyżga, B.; Mikuś, P.; Hajdukiewicz, M.; Stoffel, M. Large Wood Clogging during Floods in a Gravel-Bed River: The Długopole Bridge in the Czarny Dunajec River, Poland. In Proceedings of the Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; John Wiley and Sons Ltd., March 15 2017; Vol. 42; pp. 516–530. [Google Scholar]

- Panici, D.; Kripakaran, P.; Djordjević, S.; Dentith, K. A Practical Method to Assess Risks from Large Wood Debris Accumulations at Bridge Piers. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, P.N.; Solari, L.; Paris, E. Bridge Clogging Caused by Woody Debris: Experimental Analysis on the Effect of Pier Shape. Third Int. Conf. Wood World Rivers 2015 2015, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pander, J.; Mueller, M.; Knott, J.; Geist, J. Catch-Related Fish Injury and Catch Efficiency of Stow-Net-Based Fish Recovery Installations for Fish-Monitoring at Hydropower Plants. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2018, 25, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, D.; DeConto, R.M.; Alley, R.B. A Continuum Model (PSUMEL1) of Ice Mélange and Its Role during Retreat of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. Geosci. Model Dev. 2018, 11, 5149–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M. Analogies between Mineral Sediment and Vegetative Particle Dynamics in Fluvial Systems. Geomorphology 2007, 89, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčí, L.; Máčka, Z. Anthropogenic Controls on Large Wood Input, Removal and Mobility: Examples from Rivers in the Czech Republic. Area 2012, 44, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooi, M.; Besseling, E.; Kroeze, C.; van Wezel, A.P.; Koelmans, A.A. Modeling the Fate and Transport of Plastic Debris in Freshwaters: Review and Guidance. In Freshwater microplastics. The handbook of environmental chemistry; Wagner, M., Lambert, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2018; pp. 125–152.

- Carpenter, E.J.; Smith, K.L. Plastics on the Sargasso Sea Surface. Science (80-. ). 1972, 175, 1240–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.J. Floating Plastic Debris in the Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1980, 11, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.B.; Richards, D.L.; Bahner, C.D. Debris Control Structures: Evaluation and Countermeasures. Report No. FHWA-IF-04-016, Hydraulic Engineering Circular; Washington, DC, 2005;

- Wyżga, B.; Kaczka, R.J.; Zawiejska, J. Gruby Rumosz Drzewny W Ciekach Górskich Formy Występowania, Warunki Depozycji i Znaczenie Środowiskowe. Folia Geogr. Ser. Geogr. 2003, 33–34, 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rocamora, C.; Puerto, H.; Abadía, R.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Cordero, J. Floating Debris in the Low Segura River Basin (Spain): Avoiding Litter through the Irrigation Network. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, S.; Chon, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.H.; Shin, J.K. Impacts of Heavy Rain and Floodwater on Floating Debris Entering an Artificial Lake (Daecheong Reservoir, Korea) during the Summer. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 219, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; Greer, S.D.; Borrero, J.C. Numerical Modelling of Floating Debris in the World’s Oceans. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrotti, M.L.; Lombard, F.; Baudena, A.; Galgani, F.; Elineau, A.; Petit, S.; Henry, M.; Troublé, R.; Reverdin, G.; Ser-Giacomi, E.; et al. An Integrative Assessment of the Plastic Debris Load in the Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereiro, D.; Souto, C.; Gago, J. Dynamics of Floating Marine Debris in the Northern Iberian Waters: A Model Approach. J. Sea Res. 2019, 144, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G.; Melinte-Dobrinescu, M.C.; Ion, G.; Aliani, S. First Observations on the Abundance and Composition of Floating Debris in the North-Western Black Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 2015, 107, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, P.; Huang, C.; Fang, H.; Cai, W.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Yu, H. The Abundance, Composition and Sources of Marine Debris in Coastal Seawaters or Beaches around the Northern South China Sea (China). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topouzelis, K.; Papageorgiou, D.; Suaria, G.; Aliani, S. Floating Marine Litter Detection Algorithms and Techniques Using Optical Remote Sensing Data: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 170, 112675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidu, S.A.; Mawii, L.; Ranga Rao, V.; Anitha, G.; Mishra, P.; Narayanaswamy, B.E.; Anil Kumar, V.; Ramana Murthy, M.V.; GVM, G. Characterization of Plastic Debris from Surface Waters of the Eastern Arabian Sea–Indian Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.-H. A Study on Transnational Regulatory Governance for Marine Plastic Debris: Trends, Challenges, and Prospect. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 103988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisnarti, E.A.; Ningsih, N.S.; Putri, M.R.; Hendiarti, N.; Mayer, B. Dispersion of Surface Floating Plastic Marine Debris from Indonesian Waters Using Hydrodynamic and Trajectory Models. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, E.R.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Life in the “Plastisphere”: Microbial Communities on Plastic Marine Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7137–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.-H.; Kwon, O.Y.; Lee, K.-W.; Song, Y.K.; Shim, W.J. Marine Neustonic Microplastics around the Southeastern Coast of Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 96, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, H.; Ma, W.; Karakuş, O. High-Precision Density Mapping of Marine Debris and Floating Plastics via Satellite Imagery. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frias, J.P.G.L.; Lyashevska, O.; Joyce, H.; Pagter, E.; Nash, R. Floating Microplastics in a Coastal Embayment: A Multifaceted Issue. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 158, 111361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syakti, A.D.; Bouhroum, R.; Hidayati, N.V.; Koenawan, C.J.; Boulkamh, A.; Sulistyo, I.; Lebarillier, S.; Akhlus, S.; Doumenq, P.; Wong-Wah-Chung, P. Beach Macro-Litter Monitoring and Floating Microplastic in a Coastal Area of Indonesia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 122, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnússon, R.Í.; Tietema, A.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Hefting, M.M.; Kalbitz, K. Tamm Review: Sequestration of Carbon from Coarse Woody Debris in Forest Soils. For. Ecol. Manage. 2016, 377, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, G.G.O.; Schaefer, D.; Zhang, J.-L.; Tao, J.-P.; Cao, K.-F.; Corlett, R.T.; Cunningham, A.B.; Xu, J.-C.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Harrison, R.D. The Cover Uncovered: Bark Control over Wood Decomposition. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 2147–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.C. Mobility of Large Woody Debris (LWD) Jams in a Low Gradient Channel. Geomorphology 2010, 116, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohl, E. A Legacy of Absence: Wood Removal in US Rivers. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2014, 38, 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Science and Technology Studies VOSviewer Version 1. 6.20 2023.

- Nihei, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kataoka, T.; Ogata, R. High-Resolution Mapping of Japanese Microplastic and Macroplastic Emissions from the Land into the Sea. Water 2020, 12, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winton, D.J.; Anderson, L.G.; Rocliffe, S.; Loiselle, S. Macroplastic Pollution in Freshwater Environments: Focusing Public and Policy Action. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.J.; Lattin, G.L.; Zellers, A.F. Quantity and Type of Plastic Debris Flowing from Two Urban Rivers to Coastal Waters and Beaches of Southern California. Rev. Gestão Costeira Integr. 2011, 11, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupanski, D.; Ristic, R. Floating Debris from the Drina River. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2012, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-C.; Chao, Y.-C.; Chan, H.-C. Typhoon-Dominated Influence on Wood Debris Distribution and Transportation in a High Gradient Headwater Catchment. J. Mt. Sci. 2013, 10, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Ashe, E.; O’Hara, P.D. Marine Mammals and Debris in Coastal Waters of British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1303–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shumilova, O.; Tockner, K.; Gurnell, A.M.; Langhans, S.D.; Righetti, M.; Lucía, A.; Zarfl, C. Floating Matter: A Neglected Component of the Ecological Integrity of Rivers. Aquat. Sci. 2019, 81, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in Freshwater and Terrestrial Environments: Evaluating the Current Understanding to Identify the Knowledge Gaps and Future Research Priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agamuthu, P.; Mehran, S.B.; Norkhairah, A.; Norkhairiyah, A. Marine Debris: A Review of Impacts and Global Initiatives. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.; Lebreton, L.C.M.; Carson, H.S.; Thiel, M.; Moore, C.J.; Borerro, J.C.; Galgani, F.; Ryan, P.G.; Reisser, J. Plastic Pollution in the World’s Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea. PLoS One 2014, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.M.; Ulla, M.A.; Rabuffetti, A.P.; Garello, N. Plastic Pollution in Freshwater Ecosystems: Macro-, Meso-, and Microplastic Debris in a Floodplain Lake. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Emmerik, T.; Schwarz, A. Plastic Debris in Rivers. WIREs Water 2020, 7, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebreton, L.C.M.; Slat, B.; Ferrari, F.; Sainte-Rose, B.; Aitken, J.; Marthouse, R.; Hajbane, S.; Cunsolo, S.; Schwarz, A.; Levivier, A.; et al. Evidence That the Great Pacific Garbage Patch Is Rapidly Accumulating Plastic. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cózar, A.; Echevarría, F.; González-Gordillo, J.I.; Irigoien, X.; Úbeda, B.; Hernández-León, S.; Palma, Á.T.; Navarro, S.; García-de-Lomas, J.; Ruiz, A.; et al. Plastic Debris in the Open Ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 10239–10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bak, S.; Jang, W.J.; Kim, H.-M.; Kim, T.-Y.; Ye, G.H. A Performance Comparison of Land-Based Floating Debris Detection Based on Deep Learning and Its Field Applications. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2023, 39, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poletti, S.A.; Landberg, T. Using Nature Preserve Creek Cleanups to Quantify Anthropogenic Litter Accumulation in an Urban Watershed. Freshw. Sci. 2021, 40, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Yang, M.; Wang, H. A Detection Approach for Floating Debris Using Ground Images Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmer, S.C.; Matos, L.; Jarvie, S. Assessment of the Degradation of Aesthetics Beneficial Use Impairment in the Toronto and Region Area of Concern. Aquat. Ecosyst. Heal. Manag. 2018, 21, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highways England CD 356 Design of Highway Structures for Hydraulic Action Revision 1. 2020, 22.

- Breviglieri, C.P.B.; Romero, G.Q. Prey Stimuli Trigger Trophic Interception across Ecosystems. Austral Ecol. 2019, 44, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolev, G.; Bathaie, S.N.T.; Rybin, V.; Kulagin, M.; Karimov, T. Design of Small Unmanned Surface Vehicle with Autonomous Navigation System. Inventions 2021, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Song, Y.; Xie, M.; Hou, Z.; Wang, H. Dynamic Responses of a Novel Floating Tapered Trash Blocking Net System Due to Wave-Current Combination. Ocean Eng. 2022, 266, 113141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Pagliara, S.; Palermo, M. Experimental Analysis of Structures for Trapping Sars-Cov-2-Related Floating Waste in Rivers. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, R.F.; Dallimore, S.R. Assessment of Storm Surge History as Recorded by Driftwood in the Mackenzie Delta and Tuktoyaktuk Coastlands, Arctic Canada. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbeckmann, S.; Kreikemeyer, B.; Labrenz, M. Environmental Factors Support the Formation of Specific Bacterial Assemblages on Microplastics. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connors, E.; Lebreton, L.; Bowman, J.S.; Royer, S. Changes in Microbial Community Structure of Bio-fouled Polyolefins over a Year-long Seawater Incubation in Hawai’i. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.S.; Bilby, R.E.; Bondar, C.A. ORGANIC MATTER DYNAMICS IN SMALL STREAMS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2005, 41, 921–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, R.; Datry, T. Invertebrates and Sestonic Matter in an Advancing Wetted Front Travelling down a Dry River Bed (Albarine, France). Freshw. Sci. 2012, 31, 1187–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosado, J.; Morais, M.; Tockner, K. Mass Dispersal of Terrestrial Organisms During First Flush Events in a Temporary Stream. River Res. Appl. 2015, 31, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, M.; Muñoz, I.; Menéndez, M. Heterogeneity in Leaf Litter Decomposition in a Temporary Mediterranean Stream during Flow Fragmentation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 553, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrady, A.L. Microplastics in the Marine Environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1596–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PlasticsEurope Plastics – the Facts 2022. 2022, 81.

- Solé Gómez, À.; Scandolo, L.; Eisemann, E. A Learning Approach for River Debris Detection. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2022, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawecki, D.; Wu, Q.; Gonçalves, J.S.V.; Nowack, B. Polymer-Specific Dynamic Probabilistic Material Flow Analysis of Seven Polymers in Europe from 1950 to 2016. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, N.B.; Hüffer, T.; Thompson, R.C.; Hassellöv, M.; Verschoor, A.; Daugaard, A.E.; Rist, S.; Karlsson, T.; Brennholt, N.; Cole, M.; et al. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Recommendations for a Definition and Categorization Framework for Plastic Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blettler, M.C.M.; Abrial, E.; Khan, F.R.; Sivri, N.; Espinola, L.A. Freshwater Plastic Pollution: Recognizing Research Biases and Identifying Knowledge Gaps. Water Res. 2018, 143, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Emmerik, T.; Schwarz, A. Riverine Macroplastics and How to Find Them. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2020; EGU2020-11840: online; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheavly, S.B.; Register, K.M. Marine Debris & Plastics: Environmental Concerns, Sources, Impacts and Solutions. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Krauth, T.; Wagner, S. Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12246–12253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widianarko, Y.B.; Hantoro, I. Mikroplastik Dalam Seafood Dari Pantai Utara Jawa; Penerbit Universitas Katolik Soegijapranata: Semarang, 2018; ISBN 978-602-6865-74-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hemdan, N.-A.T.; Abdallah, M.Y.; Mohamed, A.-A.G.; Abd-Elmaged, A.B.A.-E. Experimental Study on the Effect of Permeable Blockage At Front of One Pier on Scour Depth At Mult-Vents Bridge Supports. JES. J. Eng. Sci. 2016, 44, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Ma, Y.; Li, T.; Sun, M.; Sun, Z.; Duan, J. The Detrimental Effects of Micro-and Nano-Plastics on Digestive System: An Overview of Oxidative Stress-Related Adverse Outcome Pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 878, 163144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur, C.; Baker, J.; Bamford, H. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris. NOAA Tech. Memo. NOS-OR&R-30 2009, Sept 9-11, 49.

- Park, T.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Lee, M.-S.; Lee, J.-K.; Park, J.-H.; Zoh, K.-D. Distributions of Microplastics in Surface Water, Fish, and Sediment in the Vicinity of a Sewage Treatment Plant. Water 2020, 12, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Balasubramanian, R. Microplastics in Aquatic and Atmospheric Environments: Recent Advancements and Future Perspectives. In Emerging Aquatic Contaminants; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 49–84.

- Radford, F.; Horton, A.A.; Felgate, S.; Lichtschlag, A.; Hunt, J.; Andrade, V.; Sanders, R.; Evans, C. Factors Influencing Microplastic Abundances in the Sediments of a Seagrass-Dominated Tropical Atoll. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 357, 124483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.C.; Swan, S.H.; Moore, C.J.; vom Saal, F.S. Our Plastic Age. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1973–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welden, N.A.; Lusher, A. Microplastics: From Origin to Impacts. In Plastic Waste and Recycling; Elsevier Inc., 2020; Vol. 32, pp. 223–249 ISBN 9780128178805.

- Mangarengi, N.A.P.; Zakaria, R.; Zubair, A.; Langka, P.; Riswanto, N.A. Distribution of Microplastic Abundance and Composition in Surface Water around Anthropogenic Areas (Case Study: Jeneberang River, South Sulawesi, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conowall, P.; Schreiner, K.M.; Marchand, J.; Minor, E.C.; Schoenebeck, C.W.; Maurer-Jones, M.A.; Hrabik, T.R. Variability in the Drivers of Microplastic Consumption by Fish across Four Lake Ecosystems. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Hosny, M.; Eltaweil, A.S.; Omar, S.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Farghali, M.; Yap, P.-S.; Wu, Y.-S.; Nagandran, S.; Batumalaie, K.; et al. Microplastic Sources, Formation, Toxicity and Remediation: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2129–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszczyński, M.; Błotnicki, J. Badanie Ruchu Rumowiska Polifrakcyjnego w Szczelinowej Przepławce Dla Ryb. In Modelowanie procesów hydrologicznych Zagadnienia modelowania w sektorze gospodarki wodnej; Kałuża, T., Radecki-Pawlik, A., Wiatkowski, M., Hammerling, M., Eds.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, 2020; pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Cho, J.; Sohn, J.; Kim, C. Health Effects of Microplastic Exposures: Current Issues and Perspectives in South Korea. Yonsei Med. J. 2023, 64, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, M.; Pironti, C.; Motta, O.; Miele, Y.; Proto, A.; Montano, L. Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment: Occurrence, Persistence, Analysis, and Human Exposure. Water 2021, 13, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, S.-J.; Wolter, H.; Delorme, A.E.; Lebreton, L.; Poirion, O.B. Computer Vision Segmentation Model—Deep Learning for Categorizing Microplastic Debris. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebuhar, J.D.; Negrete, J.; Rodríguez Pirani, L.S.; Picone, A.L.; Proietti, M.; Romano, R.M.; Della Védova, C.O.; Casaux, R.; Secchi, E.R.; Botta, S. Anthropogenic Debris in Three Sympatric Seal Species of the Western Antarctic Peninsula. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 922, 171273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibes, P.M.; Gabel, F. Floating Microplastic Debris in a Rural River in Germany: Distribution, Types and Potential Sources and Sinks. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 816, 151641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperi, J.; Dris, R.; Bonin, T.; Rocher, V.; Tassin, B. Assessment of Floating Plastic Debris in Surface Water along the Seine River. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 195, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherian, A.G.; Liu, Z.; McKie, M.J.; Almuhtaram, H.; Andrews, R.C. Microplastic Removal from Drinking Water Using Point-of-Use Devices. Polymers (Basel). 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, A.; Jiang, J.; Liang, Y.; Cao, X.; He, D. Removal of Microplastics in Water: Technology Progress and Green Strategies. Green Anal. Chem. 2022, 3, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynek, R.; Tekman, M.B.; Rummel, C.; Bergmann, M.; Wagner, S.; Jahnke, A.; Reemtsma, T. Hotspots of Floating Plastic Particles across the North Pacific Ocean. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jebril, S.; Fredj, Z.; Saeed, A.A.; Gonçalves, A.M.; Kaur, M.; Kumar, A.; Singh, B. Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Chemo(Bio)Sensors for the Detection of Nanoplastic Residues: Trends and Future Prospects. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 832–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowicz, I.; Enebro, J.; Yarahmadi, N. Challenges in the Search for Nanoplastics in the Environment — A Critical Review from the Polymer Science Perspective. Polym. Test. 2021, 93, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaud, S.; Aynard, A.; Grassl, B.; Gigault, J. Nanoplastics: From Model Materials to Colloidal Fate. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 57, 101528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Kuramochi, H.; Osako, M.; Suzuki, G. Preparation of Nanoplastic Particles as Potential Standards for the Study of Nanoplastics. YAKUGAKU ZASSHI 2024, 144, 23–00152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.-W.; Choi, J.; Ryu, K.-Y. Recent Progress and Future Directions of the Research on Nanoplastic-Induced Neurotoxicity. Neural Regen. Res. 2024, 19, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, W.B.; Kwon, N.-J.; Choi, S.-J.; Kang, C.K.; Choe, P.G.; Kim, J.Y.; Yun, J.; Lee, G.-W.; Seong, M.-W.; Kim, N.J.; et al. Virus Isolation from the First Patient with SARS-CoV-2 in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-M.; Chung, Y.-S.; Jo, H.J.; Lee, N.-J.; Kim, M.S.; Woo, S.H.; Park, S.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, H.M.; Han, M.-G. Identification of Coronavirus Isolated from a Patient in Korea with COVID-19. Osong Public Heal. Res. Perspect. 2020, 11, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Minimum Sizes of Respiratory Particles Carrying SARS-CoV-2 and the Possibility of Aerosol Generation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, S.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, W.; Wanger, T.C. Size-Classifiable Quantification of Nanoplastic by Rate Zonal Centrifugation Coupled with Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1314, 342752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NRC. Size Limits of Very Small Microorganisms: Proceedings of a Workshop; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-309-06634-1. [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Silva, M.; Dao, M.; Han, J.; Lim, C.-T.; Suresh, S. Shape and Biomechanical Characteristics of Human Red Blood Cells in Health and Disease. MRS Bull. 2010, 35, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materić, D.; Peacock, M.; Dean, J.; Futter, M.; Maximov, T.; Moldan, F.; Röckmann, T.; Holzinger, R. Presence of Nanoplastics in Rural and Remote Surface Waters. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.F.; Ding, J.N.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, X.Z.; Zou, H. Exposure to Polystyrene Nanoplastic Leads to Inhibition of Anaerobic Digestion System. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, N.; Gao, X.; Lang, X.; Deng, H.; Bratu, T.M.; Chen, Q.; Stapleton, P.; Yan, B.; Min, W. Rapid Single-Particle Chemical Imaging of Nanoplastics by SRS Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNEP Marine Litter: A Global Challenge; UNEP: Nairobi, 2009; ISBN 9789280730296.

- Ogawa, M.; Mitani, Y. Distribution and Composition of Floating Marine Debris in Shiretoko Peninsula, Japan, Using Opportunistic Sighting Survey. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavan, S.; Jayakumar, N.; Santhoshkumar, S.; Subburaj, A.; Balasundari, S. Dynamics of Marine Debris in the Point Calimere Wildlife and Bird Sanctuary Wetland, Southeastern Coast of India. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 251, 107097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science (80-.). 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaruwan, R.D.C.; Bellanthudawa, B.K.A.; Perera, I.J.J.U.N.; Udayanga, K.A.S.; Jayapala, H.P.S. Index Based Approach for Assessment of Abundance of Marine Debris and Status of Marine Pollution in Kandakuliya, Kalpitiya, Sri Lanka. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 197, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayapala, H.P.S.; Jayasiri, H.B.; Ranatunga, R.R.M.K.; Perera, I.J.J.U.N.; Bellanthudawa, B.K.A. Ecological Ramifications of Marine Debris in Mangrove Ecosystems: Estimation of Substrate Coverage and Physical Effects of Marine Debris on Mangrove Ecosystem in Negombo Lagoon, Sri Lanka. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.L.; Cimino, M.A.; Dinniman, M.S.; Lynch, H.J. Quantifying Potential Marine Debris Sources and Potential Threats to Penguins on the West Antarctic Peninsula. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GESAMP. Sources, Fate and Effects of Microplastics in the Marine Environment: Part Two of a Global Assessment; Kershaw, P.J., Rochman, C.M., Eds.; (IMO/FAO/UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/ UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine En; 2016; Vol. 93.

- Browne, M.A.; Chapman, M.G.; Thompson, R.C.; Amaral Zettler, L.A.; Jambeck, J.; Mallos, N.J. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Stranded Intertidal Marine Debris: Is There a Picture of Global Change? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 7082–7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Samborska, V.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. Our World Data 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, R.; Shams, Z.I. Quantities and Composition of Shore Debris along Clifton Beach, Karachi, Pakistan. J. Coast. Conserv. 2015, 19, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derraik, J.G.B. The Pollution of the Marine Environment by Plastic Debris: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, E.; Antonelis, K.; Drinkwin, J.; Gorgin, S.; Suuronen, P.; Thomas, S.N.; Wilson, J. Introduction to the Marine Policy Special Issue on Abandoned, Lost and Discarded Fishing Gear: Causes, Magnitude, Impacts, Mitigation Methods and Priorities for Monitoring and Evidence-Informed Management. Mar. Policy 2023, 155, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbule, K.; Herrmann, B.; Grimaldo, E.; Brinkhof, J.; Sistiaga, M.; Larsen, R.B.; Bak-Jensen, Z. Ghost Fishing Efficiency by Lost, Abandoned or Discarded Pots in Snow Crab (Chionoecetes Opilio) Fishery. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 193, 115249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Herrmann, B.; Cerbule, K.; Liu, C.; Dou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Tang, Y. Ghost Fishing Efficiency in Swimming Crab (Portunus Trituberculatus) Pot Fishery. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuyler, Q.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C.; Townsend, K. Global Analysis of Anthropogenic Debris Ingestion by Sea Turtles. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauk, G.J.M.; Schrey, E. Litter Pollution from Ships in the German Bight. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1987, 18, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. Impact of Nondegradable Marine Debris on the Ecology and Survival Outlook of Sea Turtles. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 1987, 18, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattlin, R.H.; Cawthorn, M.W. Marine Debris - an International Problem. New Zeal. Environ. 1986, 51, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf, M. Plastic Reaps a Grim Harvest in the Oceans of the World (Plastic Trash Kills and Maims Marine Life). Smithsonian 1988, 18, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Iskandar, M.R.; Cordova, M.R.; Park, Y.-G. Pathways and Destinations of Floating Marine Plastic Debris from 10 Major Rivers in Java and Bali, Indonesia: A Lagrangian Particle Tracking Perspective. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 185, 114331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P.G.; Moore, C.J.; van Franeker, J.A.; Moloney, C.L. Monitoring the Abundance of Plastic Debris in the Marine Environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.J.; Hafner, J.; Lamson, M.R.; Maximenko, N.A.; Welti, C.W. Interannual Variability in Marine Debris Accumulation on Hawaiian Shores: The Role of North Pacific Ocean Basin-Scale Dynamics. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 203, 116484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Wan, R.; Ma, Y.; You, L. Distribution and Pollution Assessment of Marine Debris Off-Shore Shandong from 2014 to 2022. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 195, 115470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOAA, N.O. and A.A. Garbage Patches Available online: https://marinedebris.noaa.gov/info/patch.html.

- Calvert, R.; Peytavin, A.; Pham, Y.; Duhamel, A.; van der Zanden, J.; van Essen, S.M.; Sainte-Rose, B.; van den Bremer, T.S. A Laboratory Study of the Effects of Size, Density, and Shape on the Wave-Induced Transport of Floating Marine Litter. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2024, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, S.-J.; Corniuk, R.N.; McWhirter, A.; Lynch, H.W.; Pollock, K.; O’Brien, K.; Escalle, L.; Stevens, K.A.; Moreno, G.; Lynch, J.M. Large Floating Abandoned, Lost or Discarded Fishing Gear (ALDFG) Is Frequent Marine Pollution in the Hawaiian Islands and Palmyra Atoll. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 196, 115585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Marine Debris as a Potential Pathway for Invasive Species. Silver Spring 2017, 31.

- Egger, M.; van Vulpen, M.; Spanowicz, K.; Wada, K.; Pham, Y.; Wolter, H.; Fuhrimann, S.; Lebreton, L. Densities of Neuston Often Not Elevated within Plastic Hotspots Territory inside the North Pacific Garbage Patch. Environ. Res. Ecol. 2024, 3, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzin, A.E.; Trukhin, A.M. Entanglement of Steller Sea Lions (Eumetopias Jubatus) in Man-Made Marine Debris on Tyuleniy Island, Sea of Okhotsk. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 177, 113521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S.; Bravo Rebolledo, E.L.; van Franeker, J.A. Deleterious Effects of Litter on Marine Life. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 75–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, M.R. Environmental Implications of Plastic Debris in Marine Settings—Entanglement, Ingestion, Smothering, Hangers-on, Hitch-Hiking and Alien Invasions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2013–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Shim, W.J.; Cho, Y.; Han, G.M.; Ha, S.Y.; Hong, S.H. Hazardous Chemical Additives within Marine Plastic Debris and Fishing Gear: Occurrence and Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 442, 141115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, C.M.; Browne, M.A.; Underwood, A.J.; van Franeker, J.A.; Thompson, R.C.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. The Ecological Impacts of Marine Debris: Unraveling the Demonstrated Evidence from What Is Perceived. Ecology 2016, 97, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmour, F.; Samara, F.; Ghalayini, T.; Kanan, S.M.; Elsayed, Y.; Al Bousi, M.; Al Naqbi, H. Junk Food: Polymer Composition of Macroplastic Marine Debris Ingested by Green and Loggerhead Sea Turtles from the Gulf of Oman. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 828, 154373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, D.C.; de Moura, J.F.; Merico, A.; Siciliano, S. Incidence of Marine Debris in Seabirds Feeding at Different Water Depths. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 119, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergfreund, J.; Wobill, C.; Evers, F.M.; Hohermuth, B.; Bertsch, P.; Lebreton, L.; Windhab, E.J.; Fischer, P. Impact of Microplastic Pollution on Breaking Waves. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.; Watkins, E.; Farmer, A.; Brink, P.; Schweitzer, J.-P. The Economics of Marine Litter. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp. 367–394. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.C.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, M.J.; Shim, W.J. Estimation of Lost Tourism Revenue in Geoje Island from the 2011 Marine Debris Pollution Event in South Korea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 81, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krelling, P.A.; Williams, T.A.; Turra, A. Differences in Perception and Reaction of Tourist Groups to Beach Marine Debris That Can Influence a Loss of Tourism Revenue in Coastal Areas. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, B.C.; Sparks, E.L.; Cunningham, S.R.; Rodolfich, A.E.; Wessel, C.; Bradley, R. Economic Impacts of Marine Debris Encounters on Commercial Shrimping. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 200, 116038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, H.K.; Jones, T.T.; Lindsey, J.K.; Herring, C.E.; Lippiatt, S.M.; Parrish, J.K.; Uhrin, A.V. How We Count Counts: Examining Influences on Detection during Shoreline Surveys of Marine Debris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 198, 115905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribic, C.A.; Dixon, T.R.; Vining, I. Marine Debris Survey Manual, 1992.

- Paters, K. Marine Debris Survey Information Guide, 2020.

- Themistocleous, K.; Papoutsa, C.; Michaelides, S.; Hadjimitsis, D. Investigating Detection of Floating Plastic Litter from Space Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rußwurm, M.; Venkatesa, S.J.; Tuia, D. Large-Scale Detection of Marine Debris in Coastal Areas with Sentinel-2. iScience 2023, 26, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mifdal, J.; Longépé, N.; Rußwurm, M. Towards Detecting Floating Objects on a Global Scale with Learned Spatial Features Using Sentinel 2. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, V-3–2021, 285–293. [CrossRef]

- Barry, P.J.; Beraud, C.; Wood, L.E.; Tidbury, H.J. Modelling of Marine Debris Pathways into UK Waters: Example of Non-Native Crustaceans Transported across the Atlantic Ocean on Floating Marine Debris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 186, 114388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faizal, I.; Anna, Z.; Utami, S.T.; Mulyani, P.G.; Purba, N.P. Baseline Data of Marine Debris in the Indonesia Beaches. Data Br. 2022, 41, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gacutan, J.; Johnston, E.L.; Tait, H.; Smith, W.; Clark, G.F. Continental Patterns in Marine Debris Revealed by a Decade of Citizen Science. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 807, 150742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Râpă, M.; Cârstea, E.M.; Șăulean, A.A.; Popa, C.L.; Matei, E.; Predescu, A.M.; Predescu, C.; Donțu, S.I.; Dincă, A.G. An Overview of the Current Trends in Marine Plastic Litter Management for a Sustainable Development. Recycling 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.-G.; Nguyen, H.-L.; Nguyen, M.-K.; Lin, C.; Hung, N.T.Q.; Khedulkar, A.P.; Hue, N.K.; Trang, P.T.T.; Mungray, A.K.; Nguyen, D.D. Marine Macro-Litter Sources and Ecological Impact: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 1257–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN SDG Goal 14: Conserve and Sustainably Use the Oceans, Seas and Marine Resources; 2024.

- Nafea, T.H.; Chan, F.K.S.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Xiao, H.; He, J. Status of Management and Mitigation of Microplastic Pollution. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, K.; Neilson, B.; Chung, A.; Meadows, A.; Castrence, M.; Ambagis, S.; Davidson, K. Mapping Coastal Marine Debris Using Aerial Imagery and Spatial Analysis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 132, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, T.; Shibata, H.; Murakami, T. Effects of the 2011 Tohoku Earthquake and Tsunami on the Abundance and Composition of Anthropogenic Marine Debris on the Continental Slope off the Pacific Coast of Northeastern Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 164, 112039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Sweet, R. The Distribution of Large Woody Debris Accumulations and Pools in Relation to Woodland Stream Management in a Small, Low-Gradient Stream. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 1998, 23, 1101–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Gregory, K.J.; Petts, G.E. The Role of Coarse Woody Debris in Forest Aquatic Habitats: Implications for Management. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 1995, 5, 143–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R.; Collins, B.D.; Buffington, J.M.; Abbe, T.B. Geomorphic Effects of Wood in Rivers. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2003, 2003, 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Abbe, T.B.; Brooks, A.P.; Montgomery, D.R. Wood in River Rehabilitation and Management. Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błotnicki, J. Hydraulic Flow Parameters in a Fishway Contaminated with Remaining Wooden Debris. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference “Environmental Engineering and Design”; Kostecki, J., Jakubaszek, A., Eds.; University of Zielona Góra: Zielona Góra, 2020; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Rasche, D.; Reinhardt-Imjela, C.; Schulte, A.; Wenzel, R. Hydrodynamic Simulation of the Effects of Stable In-Channel Large Wood on the Flood Hydrographs of a Low Mountain Range Creek, Ore Mountains, Germany. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2019, 23, 4349–4365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocchiola, D.; Rulli, M.C.; Rosso, R. Flume Experiments on Wood Entrainment in Rivers. Adv. Water Resour. 2006, 29, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R.; Abbe, T.B. Large Woody Debris Jams, Channel Hydraulics and Habitat Formation in Large Rivers. Regul. Rivers, Res. Mgmt 1996, 12, 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Gamberini, C.; Bladé, E.; Stoffel, M.; Bertoldi, W. Numerical Modeling of Instream Wood Transport, Deposition, and Accumulation in Braided Morphologies Under Unsteady Conditions: Sensitivity and High-Resolution Quantitative Model Validation. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Wyżga, B.; Hajdukiewicz, H.; Stoffel, M. Exploring Large Wood Retention and Deposition in Contrasting River Morphologies Linking Numerical Modelling and Field Observations. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2016, 41, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, R.; Reinhardt-Imjela, C.; Schulte, A.; Bölscher, J. The Potential of In-Channel Large Woody Debris in Transforming Discharge Hydrographs in Headwater Areas (Ore Mountains, Southeastern Germany). Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, G.G. Coarse Woody Debris in Lakes and Streams. Encycl. Inl. Waters 2009, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, A.; Elosegi, A.; García-Arberas, L.; Díez, J.; Rallo, A. Restoration of Dead Wood in Basque Stream Channels: Effects on Brown Trout Population. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2011, 20, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucała, A.; Budek, A. Zmiany Morfologii Koryt Wskutek Opadów Ulewnych Na Przykładzie Potoku Suszanka, Beskid Średni. Czas. Geogr. 2010, 82, 321–332. [Google Scholar]

- Schmocker, L.; Hager, W.H. Probability of Drift Blockage at Bridge Decks. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2011, 137, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricar, M.F.; Maricar, F.; Lopa, R.T.; Hashimoto, H. Flume Experiments on Log Accumulation at the Bridge with Pier and without Pier. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 419, 012124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricar, M.F.; Maricar, F. Flume Experiments on Woody Debris Accumulation at the Bridge Pier during Flood. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 575, 012188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, M.E.; Franklin, J.F.; Swanson, F.J.; Lattin, J.D.; Cline, S.P.; Harmon, M.E.; Franklin, J.F.; Swanson, F.J. Ecology of Coarse Woody Debris in Temperate Ecosystems Ecology of Coarse Woody Debris in Temperate Ecosystems; 1986; Vol. 15;

- Butler, D.R.; Malanson, G.P. Sedimentation Rates and Patterns in Beaver Ponds in a Mountain Environment. Geomorphology 1995, 13, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, A.P.; Gaywood, M.J. The Impacts of Beavers Castor Spp. on Biodiversity and the Ecological Basis for Their Reintroduction to Scotland, UK. Mamm. Rev. 2016, 46, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, A. Bóbr - Budowniczy i Inżynier; Fundacja Wspierania Inicjatyw Ekologicznych: Kraków, 2010; ISBN 978-83-62598-04-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselquist, E.M.; Polvi, L.E.; Kahlert, M.; Nilsson, C.; Sandberg, L.; McKie, B.G. Contrasting Responses among Aquatic Organism Groups to Changes in Geomorphic Complexity along a Gradient of Stream Habitat Restoration: Implications for Restoration Planning and Assessment. Water (Switzerland) 2018, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, F.; Swanson, F.J.; Wondzell, S.M. Disturbance Regimes of Stream and Riparian Systems - A Disturbance-Casade Perspective. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 2849–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.M.; Azevedo, L. Automatic Detection and Identification of Floating Marine Debris Using Multispectral Satellite Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Hou, T.; Jin, Q.; You, A. Improved Yolo Based Detection Algorithm for Floating Debris in Waterway. Entropy 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, J.; Shao, Y.; Miura, N. Underwater and Airborne Monitoring of Marine Ecosystems and Debris. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2019, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, S.A.; Khairuddin, U.; Khairuddin, A.S.M. Development of Machine Vision System for Riverine Debris Counting. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th IEEE International Conference on Recent Advances and Innovations in Engineering (ICRAIE); IEEE, December 1 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Liu, S.; Cai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Tu, G. TC-YOLOv5: Rapid Detection of Floating Debris on Raspberry Pi 4B. J. Real-Time Image Process. 2023, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Jin, G.; Yu, G.; Zhang, X.; Qin, Z. YOLOv5n++: An Edge-Based Improved YOLOv5n Model to Detect River Floating Debris. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 46, 2507–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, L.; Clewley, D.; Martinez-Vicente, V.; Topouzelis, K. Finding Plastic Patches in Coastal Waters Using Optical Satellite Data. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cózar, A.; Arias, M.; Suaria, G.; Viejo, J.; Aliani, S.; Koutroulis, A.; Delaney, J.; Bonnery, G.; Macías, D.; de Vries, R.; et al. Proof of Concept for a New Sensor to Monitor Marine Litter from Space. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, D.E.; Collins, A.L.; Stroud, R.W. Tracing Suspended Sediment and Particulate Phosphorus Sources in Catchments. J. Hydrol. 2008, 350, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covino, T. Hydrologic Connectivity as a Framework for Understanding Biogeochemical Flux through Watersheds and along Fluvial Networks. Geomorphology 2017, 277, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercruysse, K.; Grabowski, R.C.; Rickson, R.J. Suspended Sediment Transport Dynamics in Rivers: Multi-Scale Drivers of Temporal Variation. Earth-Science Rev. 2017, 166, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokwa, M. Sterowanie Procesami Fluwialnymi w Korytach Rzek Przekształconych Antropogenicznie; Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Rolniczej we Wrocławiu Nr 439; Wydawnictwo Akademii Rolniczej: Wrocław, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C.T.; Tockner, K.; Ward, J.V. The Fauna of Dynamic Riverine Landscapes. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunte, K.; Swingle, K.W.; Turowski, J.M.; Abt, S.R.; Cenderelli, D.A. Measurements of Coarse Particulate Organic Matter Transport in Steep Mountain Streams and Estimates of Decadal CPOM Exports. J. Hydrol. 2016, 539, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, N.; Wohl, E. Rules of the Road: A Qualitative and Quantitative Synthesis of Large Wood Transport through Drainage Networks. Geomorphology 2017, 279, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchardt, L.; Marshall, H.G. Algal Composition and Abundance in the Neuston Surface Micro Layer from a Lake and Pond in Virginia (U.S.A.). J. Limnol. 2003, 62, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azza, N.; Denny, P.; Van de Koppel, J.; Kansiime, F. Floating Mats: Their Occurrence and Influence on Shoreline Distribution of Emergent Vegetation. Freshw. Biol. 2006, 51, 1286–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, D.L.; Findlay, S.E.G. Ecology of Freshwater Shore Zones. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 72, 127–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.; Strayer, D.L.; Findlay, S. The Ecology of Freshwater Wrack along Natural and Engineered Hudson River Shorelines. Hydrobiologia 2014, 722, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Vecchio, S.; Jucker, T.; Carboni, M.; Acosta, A.T.R. Linking Plant Communities on Land and at Sea: The Effects of Posidonia Oceanica Wrack on the Structure of Dune Vegetation. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 184, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngari, A.N.; Kinyamario, J.I.; Ntiba, M.J.; Mavuti, K.M. Factors Affecting Abundance and Distribution of Submerged and Floating Macrophytes in Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Afr. J. Ecol. 2009, 47, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarneel, J.M.; Soons, M.B.; Geurts, J.J.M.; Beltman, B.; Verhoeven, J.T.A. Multiple Effects of Land-Use Changes Impede the Colonization of Open Water in Fen Ponds. J. Veg. Sci. 2011, 22, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahlik, A.M.; Mitsch, W.J. Tropical Treatment Wetlands Dominated by Free-Floating Macrophytes for Water Quality Improvement in Costa Rica. Ecol. Eng. 2006, 28, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhote, S.; Dixit, S. Water Quality Improvement through Macrophytes—a Review. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 152, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, H.G.; Burchardt, L. Neuston: Its Definition with a Historical Review Regarding Its Concept and Community Structure. Arch. für Hydrobiol. 2005, 164, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.; Tockner, K.; Edwards, P.; Petts, G. Effects of Deposited Wood on Biocomplexity of River Corridors. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhans, S.D.; Richard, U.; Rueegg, J.; Uehlinger, U.; Edwards, P.; Doering, M.; Tockner, K. Environmental Heterogeneity Affects Input, Storage, and Transformation of Coarse Particulate Organic Matter in a Floodplain Mosaic. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 75, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turowski, J.M.; Badoux, A.; Bunte, K.; Rickli, C.; Federspiel, N.; Jochner, M. The Mass Distribution of Coarse Particulate Organic Matter Exported from an Alpine Headwater Stream. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2013, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, D.M.; Wohl, E.E. Plant Dispersal along Rivers Fragmented by Dams. River Res. Appl. 2006, 22, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Brown, R.L.; Jansson, R.; Merritt, D.M. The Role of Hydrochory in Structuring Riparian and Wetland Vegetation. Biol. Rev. 2010, 85, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Wyżga, B.; Zawiejska, J.; Hajdukiewicz, M.; Stoffel, M. Factors Controlling Large-Wood Transport in a Mountain River. Geomorphology 2016, 272, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurnell, A.M.; Piégay, H.; Swanson, F.J.; Gregory, S. V Large Wood and Fluvial Processes. Freshw. Biol. 2002, 47, 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Piégay, H.; Gurnell, A.A.; Marston, R.A.; Stoffel, M. Recent Advances Quantifying the Large Wood Dynamics in River Basins: New Methods and Remaining Challenges. Rev. Geophys. 2016, 54, 611–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Lay, Y.F.; Piégay, H.; Moulin, B. Wood Entrance, Deposition, Transfer and Effects on Fluvial Forms and Processes: Problem Statements and Challenging Issues. In Treatise on Geomorphology; Elsevier Inc., 2013; Vol. 12, pp. 20–36 ISBN 9780080885223.

- Gurnell, A.M. 9.11 Wood in Fluvial Systems. In Treatise on Geomorphology; Elsevier, 2013; pp. 163–188.

- Gurnell, A.M.; Bertoldi, W. Wood in Fluvial Systems. In Treatise on Geomorphology; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 320–352.

- Braudrick, C.A.; Grant, G.E. Transport and Deposition of Large Woody Debris in Streams: A Flume Experiment. Geomorphology 2001, 41, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Nilsson, C. Dynamics of Leaf Litter Accumulation and Its Effects on Riparian Vegetation: A Review. Bot. Rev. 1997, 63, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottmann, N. Schwemgut-Ausbreitungsmedium Terrestrischer Invertebraten in Gewässerkorridoren. [Diplomarbeit. ETH Zürich/EAWAG], 2004.

- Tenzer, C. Ausbreitung Terrestrischer Wirbelloser Durch Fliessgewässer. [Dissertation. Philipps-Universität Marburg], 2003.

- Comiti, F.; Andreoli, A.; Mao, L.; Lenzi, M.A. Wood Storage in Three Mountain Streams of the Southern Andes and Its Hydro-morphological Effects. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2008, 33, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, M.; Fiebig, D.; Brettar, I.; Eisenmann, H.; Ellis, B.K.; Kaplan, L.A.; Lock, M.A.; Naegeli, M.W.; Traunspurger, W. The Role of Micro-organisms in the Ecological Connectivity of Running Waters. Freshw. Biol. 1998, 40, 453–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdogan, Z.; Guven, B. Microplastics in the Environment: A Critical Review of Current Understanding and Identification of Future Research Needs. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 113011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havens, K.J.; Bilkovic, D.M.; Stanhope, D.; Angstadt, K.; Hershner, C. The Effects of Derelict Blue Crab Traps on Marine Organisms in the Lower York River, Virginia. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2008, 28, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlgorm, A.; Campbell, H.F.; Rule, M.J. The Economic Cost and Control of Marine Debris Damage in the Asia-Pacific Region. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidifar, H.; Shahabi-Haghighi, S.M.B.; Chiew, Y.M. Collar Performance in Bridge Pier Scour with Debris Accumulation. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2022, 37, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, W. Dynamic Amplification Responses of Short Span Bridges Considering Scour and Debris Impacts. Eng. Struct. 2022, 252, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, E.; Cunningham, L.S.; Rogers, B.D. Flood-Induced Hydrodynamic and Debris Impact Forces on Single-Span Masonry Arch Bridge. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Sebille, E.; Aliani, S.; Law, K.L.; Maximenko, N.; Alsina, J.M.; Bagaev, A.; Bergmann, M.; Chapron, B.; Chubarenko, I.; Cózar, A.; et al. The Physical Oceanography of the Transport of Floating Marine Debris. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 23003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, L.; You, S.N.; He, H.; Bao, L.J.; Liu, L.Y.; Zeng, E.Y. Riverine Microplastic Pollution in the Pearl River Delta, China: Are Modeled Estimates Accurate? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 11810–11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahens, L.; Strady, E.; Kieu-Le, T.C.; Dris, R.; Boukerma, K.; Rinnert, E.; Gasperi, J.; Tassin, B. Macroplastic and Microplastic Contamination Assessment of a Tropical River (Saigon River, Vietnam) Transversed by a Developing Megacity. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 236, 661–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.D.; Tang, Y.; He, Y.; Li, Y.J.; You, J.A.; Breider, F.; Tao, S.; Liu, W.X. Effects of Anthropogenic Discharge and Hydraulic Deposition on the Distribution and Accumulation of Microplastics in Surface Sediments of a Typical Seagoing River: The Haihe River. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeynayaka, A.; Kojima, F.; Miwa, Y.; Ito, N.; Nihei, Y.; Fukunaga, Y.; Yashima, Y.; Itsubo, N. Rapid Sampling of Suspended and Floating Microplastics in Challenging Riverine and Coastal Water Environments in Japan. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankoda, K.; Yamada, Y. Occurrence, Distribution, and Possible Sources of Microplastics in the Surface River Water in the Arakawa River Watershed. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 27474–27480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghinassi, M.; Michielotto, A.; Uguagliati, F.; Zattin, M. Mechanisms of Microplastics Trapping in River Sediments: Insights from the Arno River (Tuscany, Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.-G.; Kwak, M.-J.; Kim, Y. Polystyrene Microplastics Biodegradation by Gut Bacterial Enterobacter Hormaechei from Mealworms under Anaerobic Conditions: Anaerobic Oxidation and Depolymerization. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 459, 132045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.-F.; Li, J.-X.; Sun, C.-J.; He, C.-F.; Jiang, F.-H.; Gao, F.-L.; Zheng, L. Separation and Identification of Microplastics in Digestive System of Bivalves. Chinese J. Anal. Chem. 2018, 46, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Li, Q.; Lai, Y.; Yang, S.; Yu, S.; Liu, R.; Jiang, G.; Liu, J. Direct Entry of Micro(Nano)Plastics into Human Blood Circulatory System by Intravenous Infusion. iScience 2023, 26, 108454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, M.A.; Dissanayake, A.; Galloway, T.S.; Lowe, D.M.; Thompson, R.C. Ingested Microscopic Plastic Translocates to the Circulatory System of the Mussel, Mytilus Edulis (L.). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5026–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bearzi, G.; Bonizzoni, S.; Fanesi, F.; Tenan, S.; Battisti, C. Seabirds Pecking Polystyrene Items in Offshore Adriatic Sea Waters. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 8338–8346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.A.; Tally, T. Effects of Large Organic Debris on Channel Form and Fluvial Processes in the Coastal Redwood Environment. Eur. Sp. Agency, (Special Publ. ESA SP 1979, of, 169–197.

- Swanson, F.J.; Gregory, S.V.; Iroumé, A.; Ruiz-Villanueva, V.; Wohl, E. Reflections on the History of Research on Large Wood in Rivers. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms 2020, 66, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flotemersch, J.; Aho, K. Factors Influencing Perceptions of Aquatic Ecosystems. Ambio 2021, 50, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiman, R.J.; Bilby, R.E. River Ecology and Management: Lessons from the Pacific Coastal Ecoregion; Springer, 1998; ISBN 9780387983233.

- Narayanan, M. Origination, Fate, Accumulation, and Impact, of Microplastics in a Marine Ecosystem and Bio/Technological Approach for Remediation: A Review. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 177, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, M.; Zielonka, A.; Mikuś, P. First Attempt to Measure Macroplastic Fragmentation in Rivers. Environ. Int. 2024, 191, 108935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, M.; Zielonka, A.; Hajdukiewicz, H.; Mikuś, P.; Haska, W.; Kieniewicz, M.; Gorczyca, E.; Krzemień, K. Litter Selfie: A Citizen Science Guide for Photorecording Macroplastic Deposition along Mountain Rivers Using a Smartphone. Water 2023, 15, 3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liro, M.; Mikuś, P.; Wyżga, B. First Insight into the Macroplastic Storage in a Mountain River: The Role of in-River Vegetation Cover, Wood Jams and Channel Morphology. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derraik, J.G. . The Pollution of the Marine Environment by Plastic Debris: A Review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2002, 44, 842–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, C.; Lindeque, P.K.; Thompson, R.; Tolhurst, T.; Cole, M. Microplastics and Seafood: Lower Trophic Organisms at Highest Risk of Contamination. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, N.; Khan, M.H.; Ali, M.; Sidra; Ahmad, S. ; Khan, A.; Nabi, G.; Ali, F.; Bououdina, M.; Kyzas, G.Z. Insight into Microplastics in the Aquatic Ecosystem: Properties, Sources, Threats and Mitigation Strategies. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boever, S.; Devisscher, L.; Vinken, M. Unraveling the Micro- and Nanoplastic Predicament: A Human-Centric Insight. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 916, 170262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seewoo, B.J.; Goodes, L.M.; Mofflin, L.; Mulders, Y.R.; Wong, E.V.; Toshniwal, P.; Brunner, M.; Alex, J.; Johnston, B.; Elagali, A.; et al. The Plastic Health Map: A Systematic Evidence Map of Human Health Studies on Plastic-Associated Chemicals. Environ. Int. 2023, 181, 108225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijagic, A.; Suljević, D.; Fočak, M.; Sulejmanović, J.; Šehović, E.; Särndahl, E.; Engwall, M. The Triple Exposure Nexus of Microplastic Particles, Plastic-Associated Chemicals, and Environmental Pollutants from a Human Health Perspective. Environ. Int. 2024, 188, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health. Curr. Environ. Heal. Reports 2018, 5, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Zhang, S.; Razanajatovo, R.M.; Zou, H.; Zhu, W. Accumulation, Tissue Distribution, and Biochemical Effects of Polystyrene Microplastics in the Freshwater Fish Red Tilapia (Oreochromis Niloticus). Environ. Pollut. 2018, 238, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, J.; Fuchs, H.; Beck, C.; Albayrak, I.; Boes, R.M. Head Losses of Horizontal Bar Racks as Fish Guidance Structures. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattel, J.; Eriksson, M. Bridge Scour Evaluation: Screening, Analysis, and Countermeasures. Pub. Rep. No. 9877 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Błotnicki, J.; Gruszczyński, M.; Głowski, R.; Mokwa, M. Enhancing Migratory Potential in Fish Passes: The Role of Pier Shape in Minimizing Debris Accumulation. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 359, 121053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond-Léonard, L.J.; Bouchard, M.; Handa, I.T. Dead Wood Provides Habitat for Springtails across a Latitudinal Gradient of Forests in Quebec, Canada. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 472, 118237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, N.A.; Harvey, G.L.; Gurnell, A.M. The Early Impact of Large Wood Introduction on the Morphology and Sediment Characteristics of a Lowland River. Limnologica 2015, 54, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.J.; Hoy, M.S.; Chase, D.M.; Pess, G.R.; Brenkman, S.J.; McHenry, M.M.; Ostberg, C.O. Environmental DNA Is an Effective Tool to Track Recolonizing Migratory Fish Following Large-scale Dam Removal. Environ. DNA 2021, 3, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia de Leaniz, C.; O’Hanley, J.R. Operational Methods for Prioritizing the Removal of River Barriers: Synthesis and Guidance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 848, 157471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, P.S.; Schultz, N.; Butterworth, N.J.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Mateo-Tomás, P.; Newsome, T.M. Disentangling Ecosystem Necromass Dynamics for Biodiversity Conservation. Ecosystems 2024, 27, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbow, M.E.; Barton, P.S.; Ulyshen, M.D.; Beasley, J.C.; DeVault, T.L.; Strickland, M.S.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Jordan, H.R.; Pechal, J.L. Necrobiome Framework for Bridging Decomposition Ecology of Autotrophically and Heterotrophically Derived Organic Matter. Ecol. Monogr. 2019, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Turner, J.; Lewis, T.; McCaw, L.; Cook, G.; Adams, M.A. Dynamics of Necromass in Woody Australian Ecosystems. Ecosphere 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbow, M.E.; Pechal, J.L.; Ward, A.K. Heterotrophic Bacteria Production and Microbial Community Assessment. In Methods in Stream Ecology, Volume 1; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 161–176.

- Gulis, V.; Bärlocher, F. Fungi: Biomass, Production, and Community Structure.; 2017.

- Hübl, T.; Shridhare, L. ‘Tender Narrator’ Who Sees Beyond Time: J. Awareness-Based Syst. Chang. 2022, 2, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarczuk, O. Nobel Lecture Available online:. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2018/tokarczuk/lecture/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Gregory, S.V.; Boyer, K.L.; Gurnell, A.M. Wood Storage and Mobility. In The ecology and management of wood in world rivers 2003; Gregory, S.V., Boyer, K.L., Gurnell, A.M., Eds.; AMERICAN FISHERIES SOCIETY SYMPOSIUM SERIES; American Fisheries Society, 2003; pp. 75–91 ISBN 1-888569-56-5.

- Lebreton, L.; Egger, M.; Slat, B. A Global Mass Budget for Positively Buoyant Macroplastic Debris in the Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st Century Economist; White River Junction, Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leach, M.; Raworth, K.; Rockström, J. Between Social and Planetary Boundaries: Navigating Pathways in the Safe and Just Space for Humanity. In World Social Science Report 2013; OECD, 2013; pp. 84–89.

- dos Passos, J.S.; Lorentz, C.; Laurenti, D.; Royer, S.-J.; Chontzoglou, I.; Biller, P. Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Plastic Marine Debris from the North Pacific Garbage Patch. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 209, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A. Entropy Generation Minimization: The New Thermodynamics of Finite-Size Devices and Finite-Time Processes. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 1191–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, B. Energy, Economics; Daly, H.E. (Eds.) ; Routledge: 2019; ISBN 9780429048968.

- Morseletto, P. Targets for a Circular Economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potting, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Worrell, E.; Hanemaaijer, A.; others. Circular Economy: Measuring Innovation in the Product Chain. Planbur. voor Leefomgeving 2017.

- Desing, H.; Widmer, R.; Beloin-Saint-Pierre, D.; Hischier, R.; Wäger, P. Powering a Sustainable and Circular Economy—An Engineering Approach to Estimating Renewable Energy Potentials within Earth System Boundaries. Energies 2019, 12, 4723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Fang, C. Circular Economy Development in China-Current Situation, Evaluation and Policy Implications. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 84, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Particles | Size (microns,μm) | Source |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 0.07-0.09 | [133,134] |

| Respiratory fluid particles | 0.09-42 | [135] |

| Nanoplastic | <1 | [136] |

| Escherichia coli | 1-2 | [137] |

| Red blood cell | 6-8 | [138] |

| Fine sand | 63-200 | ISO 14688-1;2002(E) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).