Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Oral cancer, a subtype of head and neck cancer, poses significant global health challenges owing to its late diagnosis and high metastatic potential. The epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), a transmembrane glycoprotein, has emerged as a critical player in cancer biology, particularly in oral cancer stem cells (CSCs). This review highlights the multifaceted roles of EPCAM in regulating oral cancer metastasis, tumorigenicity, and resistance to therapy. EpCAM influences key pathways, including Wnt/β-catenin and EGFR, modulating CSC self-renewal, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and immune evasion. Moreover, EpCAM has been implicated in metabolic reprogramming, epigenetic regulation, and crosstalk with other signaling pathways. Advances in EpCAM-targeting strategies, such as monoclonal antibodies, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T/NK cell therapies, and aptamer-based systems hold promise for personalized cancer therapies. However, challenges remain in understanding the precise mechanism of EpCAM in CSC biology and its translation into clinical applications. This review highlights the need for further investigation into the role of EPCAM in oral CSCs and its potential as a therapeutic target to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

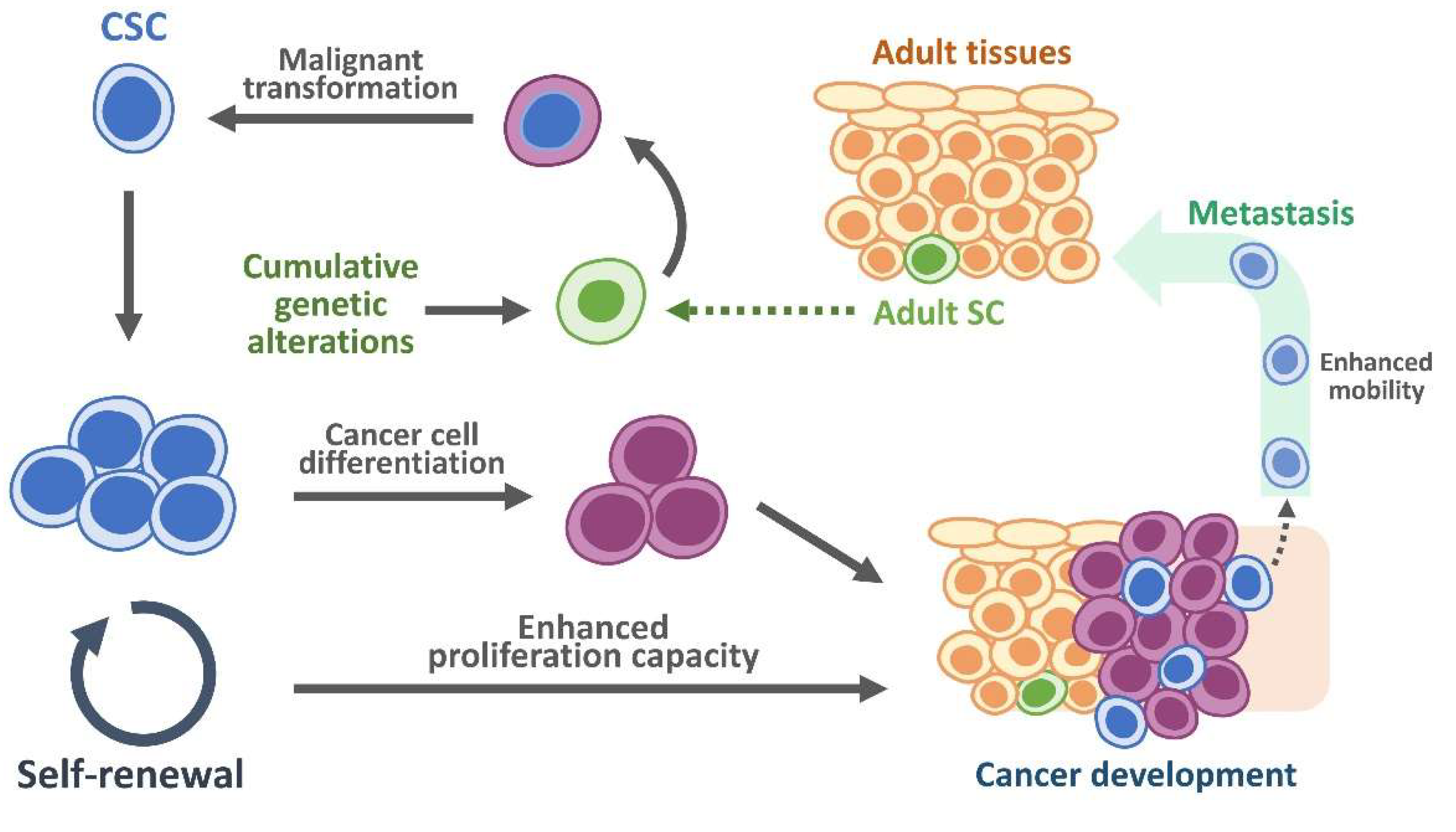

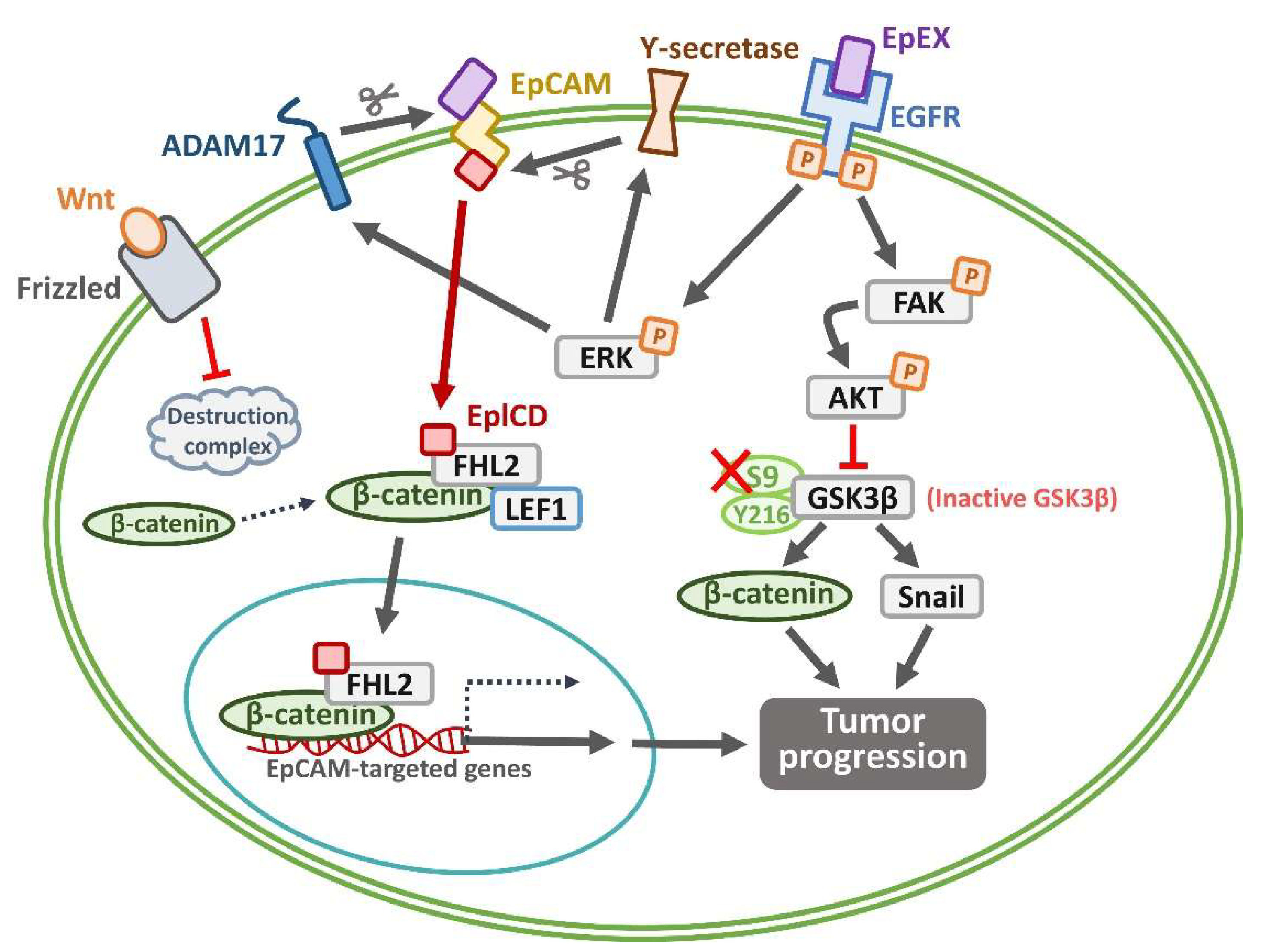

2. EpCAM as a CSC Marker: Signaling Pathways and Role in Oral CSCs

3. Crosstalk Between EpCAM and Other Signaling Pathways Regulating Oral CSC

4. Risks and Causes of Oral Cancer: Genetic Mutations, Epigenetic Changes, and Post-Translational Modifications of EpCAM

5. Role of CSCs and EpCAM Expression Within Tumor Microenvironment

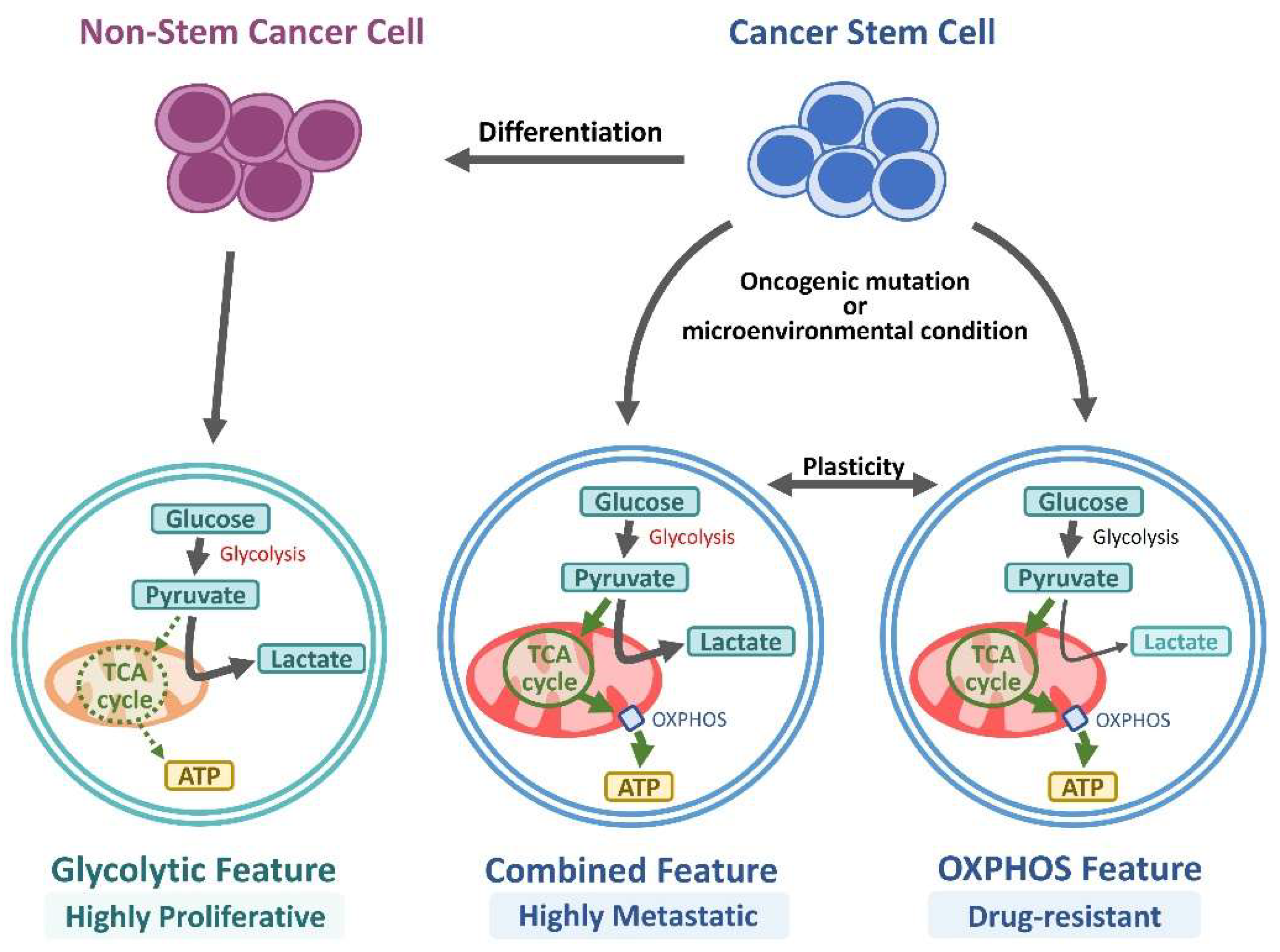

6. Role of EpCAM in CSC Metabolism

7. EpCAM as Biomarker for Oral Cancer Diagnosis and Targeting Therapy

8. EpCAM-Targeting Immunotherapies

9. Summary

10. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kamangar, F.; Dores, G.M.; Anderson, W.F. Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006, 24, 2137–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.J.; Lin, S.C.; Kao, T.; Chang, C.S.; Hong, P.S.; Shieh, T.M.; Chang, K.W. Genome-wide profiling of oral squamous cell carcinoma. The Journal of pathology 2004, 204, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, A.C.; Day, T.A.; Neville, B.W. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma--an update. CA Cancer J Clin 2015, 65, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, U.U.; Zarina, S.; Pennington, S.R. Oral squamous cell carcinoma: Key clinical questions, biomarker discovery, and the role of proteomics. Arch Oral Biol 2016, 63, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E. Oral cancer prevention and control--the approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol 2009, 45, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatahzadeh, M.; Schwartz, R.A. Oral Kaposi’s sarcoma: a review and update. Int J Dermatol 2013, 52, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kademani, D.; Bell, R.B.; Bagheri, S.; Holmgren, E.; Dierks, E.; Potter, B.; Homer, L. Prognostic factors in intraoral squamous cell carcinoma: the influence of histologic grade. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery: official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons 2005, 63, 1599–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Z.; Cheng, B.; Tao, X. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in oral squamous cell carcinoma: Challenges and opportunities. Int J Cancer 2021, 148, 1548–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clevers, H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nature medicine 2011, 17, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Filho, M.S.; Nör, J.E. The biology of head and neck cancer stem cells. Oral Oncol 2012, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorna, D.; Paluszczak, J. Targeting cancer stem cells as a strategy for reducing chemotherapy resistance in head and neck cancers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 13417–13435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oskarsson, T.; Batlle, E.; Massague, J. Metastatic stem cells: sources, niches, and vital pathways. Cell stem cell 2014, 14, 306–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinov, S.V.; Velders, M.P.; Bakker, H.A.; Fleuren, G.J.; Warnaar, S.O. Ep-CAM: a human epithelial antigen is a homophilic cell-cell adhesion molecule. The Journal of cell biology 1994, 125, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnell, U.; Cirulli, V.; Giepmans, B.N. EpCAM: structure and function in health and disease. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2013, 1828, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, C.; Macchi, R.M.; Marschner, A.K.; Mellstedt, H. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule expression (CD326) in cancer: a short review. Cancer treatment reviews 2012, 38, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Gun, B.T.; Melchers, L.J.; Ruiters, M.H.; de Leij, L.F.; McLaughlin, P.M.; Rots, M.G. EpCAM in carcinogenesis: the good, the bad or the ugly. Carcinogenesis 2010, 31, 1913–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheunemann, P.; Stoecklein, N.H.; Rehders, A.; Bidde, M.; Metz, S.; Peiper, M.; Eisenberger, C.F.; Schulte Am Esch, J.; Knoefel, W.T.; Hosch, S.B. Occult tumor cells in lymph nodes as a predictor for tumor relapse in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008, 393, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, D.; Steurer, M.; Obrist, P.; Barbieri, V.; Margreiter, R.; Amberger, A.; Laimer, K.; Gastl, G.; Tzankov, A.; Spizzo, G. Ep-CAM expression in pancreatic and ampullary carcinomas: frequency and prognostic relevance. J Clin Pathol 2008, 61, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Carnelio, S. Expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology 2016, 68, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A.K.; Clark, G.M.; Chamness, G.C.; McGuire, W.L. Association of the 323/A3 surface glycoprotein with tumor characteristics and behavior in human breast cancer. Cancer research 1990, 50, 3317–3321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gastl, G.; Spizzo, G.; Obrist, P.; Dunser, M.; Mikuz, G. Ep-CAM overexpression in breast cancer as a predictor of survival. Lancet 2000, 356, 1981–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Hasenclever, D.; Schaeffer, M.; Boehm, D.; Cotarelo, C.; Steiner, E.; Lebrecht, A.; Siggelkow, W.; Weikel, W.; Schiffer-Petry, I.; et al. Prognostic effect of epithelial cell adhesion molecule overexpression in untreated node-negative breast cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2008, 14, 5849–5855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spizzo, G.; Went, P.; Dirnhofer, S.; Obrist, P.; Simon, R.; Spichtin, H.; Maurer, R.; Metzger, U.; von Castelberg, B.; Bart, R.; et al. High Ep-CAM expression is associated with poor prognosis in node-positive breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2004, 86, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Petry, I.B.; Bohm, D.; Lebrecht, A.; von Torne, C.; Gebhard, S.; Gerhold-Ay, A.; Cotarelo, C.; Battista, M.; Schormann, W.; et al. Ep-CAM RNA expression predicts metastasis-free survival in three cohorts of untreated node-negative breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2011, 125, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeuerle, P.A.; Gires, O. EpCAM (CD326) finding its role in cancer. Br J Cancer 2007, 96, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hajj, M.; Wicha, M.S.; Benito-Hernandez, A.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003, 100, 3983–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herlyn, M.; Steplewski, Z.; Herlyn, D.; Koprowski, H. Colorectal carcinoma-specific antigen: detection by means of monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1979, 76, 1438–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmelkov, S.V.; Butler, J.M.; Hooper, A.T.; Hormigo, A.; Kushner, J.; Milde, T.; St Clair, R.; Baljevic, M.; White, I.; Jin, D.K.; et al. CD133 expression is not restricted to stem cells, and both CD133+ and CD133- metastatic colon cancer cells initiate tumors. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalerba, P.; Dylla, S.J.; Park, I.K.; Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Cho, R.W.; Hoey, T.; Gurney, A.; Huang, E.H.; Simeone, D.M.; et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 10158–10163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, L.; Yin, L.; Yao, Z.; Tong, R.; Xue, J.; Lu, Y. Lung Cancer Stem Cell Markers as Therapeutic Targets: An Update on Signaling Pathways and Therapies. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 873994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Heidt, D.G.; Dalerba, P.; Burant, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Adsay, V.; Wicha, M.; Clarke, M.F.; Simeone, D.M. Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamashita, T.; Ji, J.; Budhu, A.; Forgues, M.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.Y.; Jia, H.; Ye, Q.; Qin, L.X.; Wauthier, E.; et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1012–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, A.S.M.; Parag, R.R.; Rashid, M.I.; Islam, S.; Rahman, M.Z.; Chowdhury, A.A.; Sultana, A.; Jerin, C.; Siddiqua, A.; Rahman, L.; et al. Chemotherapeutic resistance of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is mediated by EpCAM induction driven by IL-6/p62 associated Nrf2-antioxidant pathway activation. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, A.; Gammon, L.; Liang, X.; Costea, D.E.; Mackenzie, I.C. Phenotypic Plasticity Determines Cancer Stem Cell Therapeutic Resistance in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. EBioMedicine 2016, 4, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Sun, R.; Zhou, X.M.; Zhang, M.Y.; Lu, J.B.; Yang, Y.; Zeng, L.S.; Yang, X.Z.; Shi, L.; Xiao, R.W.; et al. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule overexpression regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition, stemness and metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via the PTEN/AKT/mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.F.; Huang, Y.L.; Xie, Y.K.; Tan, Y.H.; Chen, B.C.; Zhou, M.T.; Shi, H.Q.; Yu, Z.P.; Song, Q.T.; Zhang, Q.Y. Angiogenesis and clinicopathologic characteristics in different hepatocellular carcinoma subtypes defined by EpCAM and α-fetoprotein expression status. Med Oncol 2011, 28, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Liu, T.; Yan, Q.; Yang, X. Hypoxia modulates stem cell properties and induces EMT through N-glycosylation of EpCAM in breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 2020, 235, 3626–3633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, D.; Liu, T.; Yan, Q.; Yang, X. Deglycosylation of epithelial cell adhesion molecule affects epithelial to mesenchymal transition in breast cancer cells. J Cell Physiol 2019, 234, 4504–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayama, S.; Motohara, T.; Narantuya, D.; Li, C.; Fujimoto, K.; Sakaguchi, I.; Tashiro, H.; Saya, H.; Nagano, O.; Katabuchi, H. The impact of EpCAM expression on response to chemotherapy and clinical outcomes in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 44312–44325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Cozzi, P.; Hao, J.; Beretov, J.; Chang, L.; Duan, W.; Shigdar, S.; Delprado, W.; Graham, P.; Bucci, J.; et al. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is associated with prostate cancer metastasis and chemo/radioresistance via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013, 45, 2736–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.N.; Liang, K.H.; Lai, J.K.; Lan, C.H.; Liao, M.Y.; Hung, S.H.; Chuang, Y.T.; Chen, K.C.; Tsuei, W.W.; Wu, H.C. EpCAM Signaling Promotes Tumor Progression and Protein Stability of PD-L1 through the EGFR Pathway. Cancer Res 2020, 80, 5035–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Fan, X.; Fu, B.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, A.; Zhong, K.; Yan, J.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H. EpCAM Inhibition Sensitizes Chemoresistant Leukemia to Immune Surveillance. Cancer Res 2017, 77, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maetzel, D.; Denzel, S.; Mack, B.; Canis, M.; Went, P.; Benk, M.; Kieu, C.; Papior, P.; Baeuerle, P.A.; Munz, M.; et al. Nuclear signalling by tumour-associated antigen EpCAM. Nature cell biology 2009, 11, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imrich, S.; Hachmeister, M.; Gires, O. EpCAM and its potential role in tumor-initiating cells. Cell adhesion & migration 2012, 6, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.W.; Liao, M.Y.; Lin, W.W.; Wang, Y.P.; Lu, T.Y.; Wu, H.C. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule regulates tumor initiation and tumorigenesis via activating reprogramming factors and epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene expression in colon cancer. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 39449–39459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, Z.; Xia, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, E.; Zheng, H.; Ai, W.; Dong, J. Lgr5+CD44+EpCAM+ Strictly Defines Cancer Stem Cells in Human Colorectal Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 46, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.Y.; Lu, R.M.; Liao, M.Y.; Yu, J.; Chung, C.H.; Kao, C.F.; Wu, H.C. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule regulation is associated with the maintenance of the undifferentiated phenotype of human embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 8719–8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, A.G.; Pitty, L.P.; Farah, C.S. Cancer stem cell markers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Stem Cells Int 2013, 2013, 319489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodda, D.J.; Chew, J.L.; Lim, L.H.; Loh, Y.H.; Wang, B.; Ng, H.H.; Robson, P. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem 2005, 280, 24731–24737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, G.; Red Brewer, M. EpCAM: another surface-to-nucleus missile. Cancer cell 2009, 15, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Dai, X.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Du, Y.; Xia, L. EGF signalling pathway regulates colon cancer stem cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cell Prolif 2012, 45, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umemori, K.; Ono, K.; Eguchi, T.; Kawai, H.; Nakamura, T.; Ogawa, T.; Yoshida, K.; Kanemoto, H.; Sato, K.; Obata, K.; et al. EpEX, the soluble extracellular domain of EpCAM, resists cetuximab treatment of EGFR-high head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2023, 142, 106433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.J.; Lai, G.M.; Yeh, C.T.; Lai, M.T.; Shih, P.H.; Chao, W.J.; Whang-Peng, J.; Chuang, S.E.; Lai, T.Y. Honokiol Eliminates Human Oral Cancer Stem-Like Cells Accompanied with Suppression of Wnt/ β -Catenin Signaling and Apoptosis Induction. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013, 2013, 146136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, A.; Liang, X.; Gammon, L.; Fazil, B.; Harper, L.J.; Emich, H.; Costea, D.E.; Mackenzie, I.C. Cancer stem cells in squamous cell carcinoma switch between two distinct phenotypes that are preferentially migratory or proliferative. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 5317–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Girotra, S.; Radhakrishnan, A.; Basu, S. Prevalence and determinants of tobacco consumption and oral cancer screening among men in India: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional Survey. Journal of Public Health 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chua, N.Q.E.; Dang, S.; Davis, A.; Chong, K.W.; Prime, S.S.; Cirillo, N. Molecular Mechanisms of Malignant Transformation of Oral Submucous Fibrosis by Different Betel Quid Constituents-Does Fibroblast Senescence Play a Role? Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjal, S.; Pateel, D.G.S.; Yang, Y.H.; Doss, J.G.; Bilal, S.; Maling, T.H.; Mehrotra, R.; Cheong, S.C.; Zain, R.B.M. An Overview on Betel Quid and Areca Nut Practice and Control in Selected Asian and South East Asian Countries. Subst Use Misuse 2020, 55, 1533–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, A.; Obi, K.O.; Rubenstein, J.H. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014, 109, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Molinero, J.; Migueláñez-Medrán, B.D.C.; Puente-Gutiérrez, C.; Delgado-Somolinos, E.; Martín Carreras-Presas, C.; Fernández-Farhall, J.; López-Sánchez, A.F. Association between Oral Cancer and Diet: An Update. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Lee, C.H.; Chen, M.J.; Lin, L.M.; Tsai, C.C. Betel quid chewing, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption related to oral cancer in Taiwan. J Oral Pathol Med 1995, 24, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, S. Oral Cancer: Recent Breakthroughs in Pathology and Therapeutic Approaches. Oral Oncology Reports 2024, 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodus, N.L.; Kerr, A.R.; Patel, K. Oral cancer: leukoplakia, premalignancy, and squamous cell carcinoma. Dent Clin North Am 2014, 58, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, P.C.; Jaglal, M.V.; Gopal, P.; Ghim, S.J.; Miller, D.M.; Farghaly, H.; Jenson, A.B. Human papillomavirus in metastatic squamous carcinoma from unknown primaries in the head and neck: a retrospective 7 year study. Exp Mol Pathol 2009, 87, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albers, A.E.; Chen, C.; Köberle, B.; Qian, X.; Klussmann, J.P.; Wollenberg, B.; Kaufmann, A.M. Stem cells in squamous head and neck cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012, 81, 224–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, I.; Badrzadeh, F.; Tsentalovich, Y.; Gaykalova, D.A. Connecting the dots: investigating the link between environmental, genetic, and epigenetic influences in metabolomic alterations in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2024, 43, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagnanam, M.; Mueller, J.L.; Lee, H.; Chen, Z.; Nelson, S.F.; Turner, D.; Zlotkin, S.H.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ngan, B.Y.; Libiger, O.; et al. Identification of EpCAM as the gene for congenital tufting enteropathy. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M.E.; Papp, J.; Szentirmay, Z.; Otto, S.; Olah, E. Deletions removing the last exon of TACSTD1 constitute a distinct class of mutations predisposing to Lynch syndrome. Hum Mutat 2009, 30, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligtenberg, M.J.; Kuiper, R.P.; Chan, T.L.; Goossens, M.; Hebeda, K.M.; Voorendt, M.; Lee, T.Y.; Bodmer, D.; Hoenselaar, E.; Hendriks-Cornelissen, S.J.; et al. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3′ exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet 2009, 41, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, A.; Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Pal, U.S. Molecular concept in human oral cancer. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 2015, 6, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenson, J.R.; Yang, J.; Mickel, R.A. Frequent amplification of the bcl-1 locus in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oncogene 1989, 4, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riviére, A.; Wilckens, C.; Löning, T. Expression of c-erbB2 and c-myc in squamous epithelia and squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck and the lower female genital tract. J Oral Pathol Med 1990, 19, 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somers, K.D.; Cartwright, S.L.; Schechter, G.L. Amplification of the int-2 gene in human head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Oncogene 1990, 5, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hochedlinger, K.; Yamada, Y.; Beard, C.; Jaenisch, R. Ectopic expression of Oct-4 blocks progenitor-cell differentiation and causes dysplasia in epithelial tissues. Cell 2005, 121, 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.; Zevnik, B.; Anastassiadis, K.; Niwa, H.; Klewe-Nebenius, D.; Chambers, I.; Scholer, H.; Smith, A. Formation of pluripotent stem cells in the mammalian embryo depends on the POU transcription factor Oct4. Cell 1998, 95, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, M.A.; Logullo, A.F.; Pasini, F.S.; Nonogaki, S.; Blumke, C.; Soares, F.A.; Brentani, M.M. Prognostic significance of CD24 and claudin-7 immunoexpression in ductal invasive breast cancer. Oncology reports 2012, 27, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.C.; Pan, S.H.; Yang, S.C.; Yu, S.L.; Che, T.F.; Lin, C.W.; Tsai, M.S.; Chang, G.C.; Wu, C.H.; Wu, Y.Y.; et al. Claudin-1 is a metastasis suppressor and correlates with clinical outcome in lung adenocarcinoma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 2009, 179, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeVita, V.T., Jr.; Young, R.C.; Canellos, G.P. Combination versus single agent chemotherapy: a review of the basis for selection of drug treatment of cancer. Cancer 1975, 35, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, J.; Shing, Y. Angiogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry 1992, 267, 10931–10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M.; Torisu, H.; Fukushi, J.; Nishie, A.; Kuwano, M. Biological implications of macrophage infiltration in human tumor angiogenesis. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 1999, 43 Suppl, S69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittekind, C.; Neid, M. Cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncology 2005, 69 Suppl 1, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Gu, L.; Lyu, M.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, T.; et al. Dynamic Expression of EpCAM in Primary and Metastatic Lung Cancer Is Controlled by Both Genetic and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tai, K.Y.; Shiah, S.G.; Shieh, Y.S.; Kao, Y.R.; Chi, C.Y.; Huang, E.; Lee, H.S.; Chang, L.C.; Yang, P.C.; Wu, C.W. DNA methylation and histone modification regulate silencing of epithelial cell adhesion molecule for tumor invasion and progression. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3989–3997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.T.; Gu, F.; Huang, Y.W.; Liu, J.; Ruan, J.; Huang, R.L.; Wang, C.M.; Chen, C.L.; Jadhav, R.R.; Lai, H.C.; et al. Promoter hypomethylation of EpCAM-regulated bone morphogenetic protein gene family in recurrent endometrial cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 6272–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spizzo, G.; Gastl, G.; Obrist, P.; Fong, D.; Haun, M.; Grünewald, K.; Parson, W.; Eichmann, C.; Millinger, S.; Fiegl, H.; et al. Methylation status of the Ep-CAM promoter region in human breast cancer cell lines and breast cancer tissue. Cancer Lett 2007, 246, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Gun, B.T.F.; Wasserkort, R.; Monami, A.; Jeltsch, A.; Raskó, T.; Ślaska-Kiss, K.; Cortese, R.; Rots, M.G.; de Leij, L.; Ruiters, M.H.J.; et al. Persistent downregulation of the pancarcinoma-associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule via active intranuclear methylation. Int J Cancer 2008, 123, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiah, S.G.; Chang, L.C.; Tai, K.Y.; Lee, G.H.; Wu, C.W.; Shieh, Y.S. The involvement of promoter methylation and DNA methyltransferase-1 in the regulation of EpCAM expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol 2009, 45, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, M.P.; Schön, M.; Mattes, M.J.; Stein, R.; Weber, L.; Alberti, S.; Klein, C.E. Biochemical and immunological characterization of the human carcinoma-associated antigen MH 99/KS 1/4. Int J Cancer 1993, 55, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, M.; Fellinger, K.; Hofmann, T.; Schmitt, B.; Gires, O. Glycosylation is crucial for stability of tumour and cancer stem cell antigen EpCAM. Front Biosci 2008, 13, 5195–5201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampoe, I.J.; Ng, J.S.; Lloyd, K.O. Biochemical analysis of a human epithelial surface antigen: differential cell expression and processing. Arch Biochem Biophys 1988, 267, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Yan, Q.; Yang, X. The role of epithelial cell adhesion molecule N-glycosylation on apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Tumour Biol 2017, 39, 1010428317695973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, D.; Liu, T.; Yan, Q.; Yang, X. Mutation of N-linked glycosylation in EpCAM affected cell adhesion in breast cancer cells. Biol Chem 2017, 398, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, C.; Münz, M.; Kieu, C.; Mack, B.; Breinl, P.; Wollenberg, B.; Lang, S.; Zeidler, R.; Gires, O. Tumor-specific glycosylation of the carcinoma-associated epithelial cell adhesion molecule EpCAM in head and neck carcinomas. Cancer Lett 2003, 193, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasetti, C.; Vogelstein, B. Cancer etiology. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science 2015, 347, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaks, V.; Kong, N.; Werb, Z. The cancer stem cell niche: how essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, J.; Steadman, R.; Mason, M.D.; Tabi, Z.; Clayton, A. Cancer exosomes trigger fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation. Cancer Res 2010, 70, 9621–9630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Qian, H.; Shen, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, W.; Huang, L.; Yan, Y.; Mao, F.; Zhao, C.; Shi, Y.; et al. Gastric cancer exosomes trigger differentiation of umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells to carcinoma-associated fibroblasts through TGF-β/Smad pathway. PLoS One 2012, 7, e52465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekström, E.J.; Bergenfelz, C.; von Bülow, V.; Serifler, F.; Carlemalm, E.; Jönsson, G.; Andersson, T.; Leandersson, K. WNT5A induces release of exosomes containing pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive factors from malignant melanoma cells. Mol Cancer 2014, 13, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraboletti, G.; D’Ascenzo, S.; Giusti, I.; Marchetti, D.; Borsotti, P.; Millimaggi, D.; Giavazzi, R.; Pavan, A.; Dolo, V. Bioavailability of VEGF in tumor-shed vesicles depends on vesicle burst induced by acidic pH. Neoplasia 2006, 8, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, 21, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Ye, S.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W. Oral Cancer Stem Cell-Derived Small Extracellular Vesicles Promote M2 Macrophage Polarization and Suppress CD4(+) T-Cell Activity by Transferring UCA1 and Targeting LAMC2. Stem Cells Int 2022, 2022, 5817684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.G.; Mohamadi, R.M.; Poudineh, M.; Kermanshah, L.; Ahmed, S.; Safaei, T.S.; Stojcic, J.; Nam, R.K.; Sargent, E.H.; Kelley, S.O. Interrogating Circulating Microsomes and Exosomes Using Metal Nanoparticles. Small 2016, 12, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zong, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Cui, Y. Profiling of Exosomal Biomarkers for Accurate Cancer Identification: Combining DNA-PAINT with Machine- Learning-Based Classification. Small 2019, 15, e1901014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploeg, E.M.; Ke, X.; Britsch, I.; Hendriks, M.; Van der Zant, F.A.; Kruijff, S.; Samplonius, D.F.; Zhang, H.; Helfrich, W. Bispecific antibody CD73xEpCAM selectively inhibits the adenosine-mediated immunosuppressive activity of carcinoma-derived extracellular vesicles. Cancer Lett 2021, 521, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, P.; Barneda, D.; Heeschen, C. Hallmarks of cancer stem cell metabolism. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.; Deshpande, K.; Arfuso, F.; Newsholme, P.; Dharmarajan, A. Cancer stem cell metabolism: a potential target for cancer therapy. Mol Cancer 2016, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.A.; Lin, C.H.; Chi, W.H.; Wang, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Wei, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Resveratrol Impedes the Stemness, Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition, and Metabolic Reprogramming of Cancer Stem Cells in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma through p53 Activation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013, 2013, 590393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.A.; Wang, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Chen, Y.J.; Wei, Y.H. Metabolic reprogramming orchestrates cancer stem cell properties in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cell Cycle 2015, 14, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Yuan, T.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fan, T.W.; Miriyala, S.; Lin, Y.; Yao, J.; Shi, J.; Kang, T.; et al. Loss of FBP1 by Snail-mediated repression provides metabolic advantages in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2013, 23, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.P.; Liao, J.; Tang, Z.J.; Wu, W.J.; Yang, J.; Zeng, Z.L.; Hu, Y.; Wang, P.; Ju, H.Q.; Xu, R.H.; et al. Metabolic regulation of cancer cell side population by glucose through activation of the Akt pathway. Cell Death Differ 2014, 21, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Wang, P.; Huang, J.; Qi, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, H.; Lyu, J.; Zhu, H. Metabolomics, Transcriptome and Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis of the Metabolic Heterogeneity between Oral Cancer Stem Cells and Differentiated Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahana, N.S.; Yadava, S.T.; Choudhary, B.; Ravindran, F.; Khatoon, H.; Kulkarni, M. Expression of circulating tumour cells in oral squamous cell carcinoma: An ex vivo pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2023, 27, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer metastasis reviews 1989, 8, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fidler, I.J.; Poste, G. The “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. The Lancet. Oncology 2008, 9, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidler, I.J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the ’seed and soil’ hypothesis revisited. Nature reviews. Cancer 2003, 3, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostert, B.; Sleijfer, S.; Foekens, J.A.; Gratama, J.W. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs): detection methods and their clinical relevance in breast cancer. Cancer treatment reviews 2009, 35, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grobe, A.; Blessmann, M.; Hanken, H.; Friedrich, R.E.; Schon, G.; Wikner, J.; Effenberger, K.E.; Kluwe, L.; Heiland, M.; Pantel, K.; et al. Prognostic relevance of circulating tumor cells in blood and disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2014, 20, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorges, T.M.; Tinhofer, I.; Drosch, M.; Röse, L.; Zollner, T.M.; Krahn, T.; von Ahsen, O. Circulating tumour cells escape from EpCAM-based detection due to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagrath, S.; Sequist, L.V.; Maheswaran, S.; Bell, D.W.; Irimia, D.; Ulkus, L.; Smith, M.R.; Kwak, E.L.; Digumarthy, S.; Muzikansky, A.; et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature 2007, 450, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankeny, J.S.; Court, C.M.; Hou, S.; Li, Q.; Song, M.; Wu, D.; Chen, J.F.; Lee, T.; Lin, M.; Sho, S.; et al. Circulating tumour cells as a biomarker for diagnosis and staging in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 2016, 114, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Marx, A.; Alexander, A.; Wiley, J.; Kai, M.; Valero, V.; Lim, B. A combination of circulating tumor cell (CTC) and cancer stem cell (CSC) markers to predict the prognosis of breast cancer. 2023.

- Wicha, M.S. Targeting self-renewal, an Achilles’ heel of cancer stem cells. Nat Med 2014, 20, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, B.B.; Zhang, H.; Damelin, M.; Geles, K.G.; Grindley, J.C.; Dirks, P.B. Tumour-initiating cells: challenges and opportunities for anticancer drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 806–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Ohishi, T.; Takei, J.; Sano, M.; Nakamura, T.; Hosono, H.; Yanaka, M.; Asano, T.; Sayama, Y.; Harada, H.; et al. Anti-EpCAM monoclonal antibody exerts antitumor activity against oral squamous cell carcinomas. Oncol Rep 2020, 44, 2517–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, M.; Dorado, J.; Baeuerle, P.A.; Heeschen, C. EpCAM/CD3-Bispecific T-cell engaging antibody MT110 eliminates primary human pancreatic cancer stem cells. Clin Cancer Res 2012, 18, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, F.; Bellone, S.; Black, J.; Schwab, C.L.; Lopez, S.; Cocco, E.; Bonazzoli, E.; Predolini, F.; Menderes, G.; Litkouhi, B.; et al. Solitomab, an EpCAM/CD3 bispecific antibody construct (BiTE®), is highly active against primary uterine and ovarian carcinosarcoma cell lines in vitro. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015, 34, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, W.M.; Wolf, M.; Kebenko, M.; Goebeler, M.-E.; Ritter, B.; Quaas, A.; Vieser, E.; Hijazi, Y.; Patzak, I.; Friedrich, M. A phase I study of EpCAM/CD3-bispecific antibody (MT110) in patients with advanced solid tumors. 2012.

- Carson, W.E.; Giri, J.G.; Lindemann, M.J.; Linett, M.L.; Ahdieh, M.; Paxton, R.; Anderson, D.; Eisenmann, J.; Grabstein, K.; Caligiuri, M.A. Interleukin (IL) 15 is a novel cytokine that activates human natural killer cells via components of the IL-2 receptor. J Exp Med 1994, 180, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahm, C.; Schönfeld, K.; Wels, W.S. Expression of IL-15 in NK cells results in rapid enrichment and selective cytotoxicity of gene-modified effectors that carry a tumor-specific antigen receptor. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2012, 61, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nian, Z.; Zheng, X.; Dou, Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, L.; Fu, B.; Sun, R.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H. Rapamycin Pretreatment Rescues the Bone Marrow AML Cell Elimination Capacity of CAR-T Cells. Clin Cancer Res 2021, 27, 6026–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; McCloskey, J.E.; Yang, H.; Puc, J.; Alcaina, Y.; Vedvyas, Y.; Gomez Gallegos, A.A.; Ortiz-Sánchez, E.; de Stanchina, E.; Min, I.M.; et al. Bispecific CAR T Cells against EpCAM and Inducible ICAM-1 Overcome Antigen Heterogeneity and Generate Superior Antitumor Responses. Cancer Immunol Res 2021, 9, 1158–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Tian, E.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, T.; Dou, W.; Meng, X.; Chen, M.; et al. Targeting Wnt Signaling in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment to Enhancing EpCAM CAR T-Cell therapy. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 724306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.Q. Adoptive T-cell therapy of prostate cancer targeting the cancer stem cell antigen EpCAM. BMC Immunol 2015, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, M.L.; Riviere, I.; Wang, X.; Bartido, S.; Park, J.; Curran, K.; Chung, S.S.; Stefanski, J.; Borquez-Ojeda, O.; Olszewska, M.; et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2014, 6, 224ra225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, B.G.; Jensen, M.C.; Wang, J.; Qian, X.; Gopal, A.K.; Maloney, D.G.; Lindgren, C.G.; Lin, Y.; Pagel, J.M.; Budde, L.E.; et al. CD20-specific adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma using a chimeric antigen receptor with both CD28 and 4-1BB domains: pilot clinical trial results. Blood 2012, 119, 3940–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wen, P.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X.A. Construction of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells targeting EpCAM and assessment of their anti-tumor effect on cancer cells. Mol Med Rep 2019, 20, 2355–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Guo, X.; Yang, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Y.; Liang, X.; Su, J.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.; et al. EpCAM-targeting CAR-T cell immunotherapy is safe and efficacious for epithelial tumors. Sci Adv 2023, 9, eadg9721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, S.J.; Park, Y.S.; Park, H.S.; Yang, K.M.; Heo, K. EpCAM peptide-primed dendritic cell vaccination confers significant anti-tumor immunity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0190638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Heidenreich, R.; Braumüller, H.; Wolburg, H.; Weidemann, S.; Mocikat, R.; Röcken, M. EpCAM, a human tumor-associated antigen promotes Th2 development and tumor immune evasion. Blood 2009, 113, 3494–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; Shigdar, S.; Bean, A.G.; Bruce, M.; Yang, W.; Mathesh, M.; Wang, T.; Yin, W.; Tran, P.H.; Al Shamaileh, H.; et al. Transforming doxorubicin into a cancer stem cell killer via EpCAM aptamer-mediated delivery. Theranostics 2017, 7, 4071–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, J.; Du, J. EpCAM-Antibody-Labeled Noncytotoxic Polymer Vesicles for Cancer Stem Cells-Targeted Delivery of Anticancer Drug and siRNA. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).